|

Morristown National Historical Park New Jersey |

|

NPS photo | |

Morristown is the story of an army struggling to survive. For two critical winters the town sheltered the main encampment of the Continental Army. In 1777 George Washington overcame desertion and disease to rebuild an army capable of taking on William Howe's veteran Redcoats.

In 1779-80, the hardest winter in anyone's memory, the military struggle was almost lost amid starvation, nakedness, and mutiny. Never was Washington's leadership more evident. He held together, at a desperate time, the small, ragged army that represented the country's main hope for independence.

1777: Rebuilding an Army

Weary but elated by its brilliant victories at Trenton and Princeton, the Continental Army trudged into winter quarters at Morristown in early January 1777. The 5,000 soldiers who came to Morristown sought shelter from the blasts of winter in public buildings, private homes, even stables, barns, sheds, and tents.

At this time, Morristown consisted of a few buildings clustered around the town green a large open field often used for grazing sheep, cattle, and horses. The Presbyterian and Baptist churches dominated the scene, while the courthouse and jail served the legal needs of the town and surrounding farm communities. Much of the town's social, political, and business life was conducted at Arnold's tavern.

In the surrounding countryside prosperous farmers raised wheat, corn, rye, oats, barley, vegetables, apples, peaches, and other fruits. Much of the land was heavily forested. In the hills north of Morristown, mines and furnaces yielded iron, which was made into tools, farm implements, and cannonballs at the forges of Hibernia and Mt. Hope. At a secluded spot along the Whippany River, a small mill made gunpowder from saltpeter, sulfur, and charcoal.

George Washington could hardly have picked a more defensible place in which to rebuild his army, which had almost melted away during the Jersey campaign. The Watchung Mountains east of town protected him from Howe's army in New York City, 30 miles away. Its passes could be easily defended, and lookouts posted on ridge tops could spot any British move toward Morristown or the patriot capital of Philadelphia. Seeing that his adversary could not assail him, Washington used the winter lull to fill his ranks and forge them into an effective fighting machine.

Maintaining the size and efficiency of the army was a continuing problem. The force so recently victorious at Trenton and Princeton began to dwindle as enlistments expired and many of the men deserted. Their replacements were local militia and raw recruits, resistant to military discipline.

Disease added yet another burden. Smallpox, "the greatest of all calamities," struck the small army, and Washington had to resort to desperate measures to avert disaster. At a time when the procedure was feared and almost as dangerous as the disease itself, he ordered both soldiers and civilians to be inoculated. Before the outbreak was stilled, the town's two churches became hospitals filled with the sick and dying.

Despite these difficulties, and the ever-present shortages of food and clothing, the army not only survived, but in the spring it was greatly reinforced. As winter passed into summer, bringing dry roads and grass for the horses, the opposing armies began to move. When the British reinforced their outpost in New Brunswick, N.J., Washington ordered his army to Middlebrook, where it could oppose an enemy attack. Refusing battle, the British returned to New York, boarded troop ships, and sailed south. Leaving behind an active military hospital, small units to guard the supply depot, and a small fortification on a hill overlooking the village, the main body of the American army left Morristown in May 1777 and did not return for over two years.

Great events filled the interval. A British army surrendered at Saratoga. Philadelphia was captured, then abandoned by the enemy. The American army endured a difficult winter at Valley Forge. In June 1778, Monmouth, N.J., was the site of the last major battle in the northern states. In the South a joint Franco-American siege of Savannah ended in failure in October 1779.

"On the 14th [of December we] reached this wilderness, about three miles from Morristown, where we are to build log huts for winter quarters. Our baggage is left in the rear for want of wagons to transport it. The snow on the ground is about two feet deep, and the weather extremely cold."

—Dr James Thacher, Continental Army Surgeon, 1779

1779-1780: A Starving Time

As 1779 drew to a close, Washington turned his attention to the coming winter encampment of the Continental Army. The large British force in New York City had to be watched from a place where the American army could be preserved through the always difficult winter months. Morristown's strategic location once again satisfied these requirements.

At the end of November, Washington's army marched south from West Point to join troops from the middle and southern colonies already gathering at the encampment. The troops enroute to Morristown were veterans of the 1775 invasion of Canada and of the battles of Long Island, White Plains, Trenton, Princeton, Brandywine, and Monmouth. They were led by experienced officers like John Stark whose militia forces defeated the German troops at Bennington; Anthony Wayne, who led the assault upon the fortifications at Stony Point; and William Maxwell, a New Jerseyite, who distinguished himself while commanding Washington's light troops during the 1777 Philadelphia campaign and the Battle of Monmouth.

George Washington arrived in Morristown amidst a severe hail and snow storm on December 1, 1779, and made his headquarters at the home of Jacob Ford Jr.'s widow. Other senior officers found quarters in private homes in and around Morristown. Junior officers lived with their men in Jockey Hollow, a few miles south of Morristown. As each brigade arrived, it was assigned a campsite. The men lived in tents as work began on the log cabins that would serve as their barracks.

December introduced the worst winter of the century to Morristown. Over 20 snowstorms blasted the hills and slopes with unremitting violence, blocking vital supply roads with six-foot snowdrifts. Bread and beef, the staples of a soldier's diet, were generally adequate, but weather sometimes caused long delays in reprovisioning. As food supplies dwindled, "Nothing to eat from morning to night again," was a common entry in soldiers' diaries.

To add to the suffering, the quartermaster could not clothe the army. An officer wrote to his brother of "men naked as Lazarus, begging for clothing." Another reported only 50 men of his regiment fit for duty, many covered by only a blanket. The huts offered only the barest protection against the wind, which penetrated to the bone and froze hands and feet.

While the struggle for survival in the camps and outposts exhausted both soldier and officer, at headquarters the commander in chief faced perplexing and crucial problems. The Continental Congress could not provide for the army, and the ruinous inflation made the purchase of badly needed food and clothing almost impossible. In desperation, Washington turned to the governors of the neighboring states and the magistrates of the New Jersey counties, pleading for supplies to keep the army alive. The response from New Jersey was immediate and generous; it "saved the army from dissolution, or starving," said Washington.

Many visitors came to Washington's headquarters on business. Representatives of the Continental Congress met with him to discuss the state of the army and the prospects for victory. The French Minister Luzerne and the Spanish representative Mirallés came to review the small army. In May 1780 the young Marquis de Lafayette arrived in Morristown with news that French warships and soldiers were at last bound for America to assist Washington.

Spring brought both this welcome news and some relief to the suffering soldiers, even though shortages of food and clothing continued to be a fact of life. But the hard winter had almost destroyed the morale of both officers and enlisted men, leading to the brief mutiny in May 1780 of two regiments of the 1st Connecticut Brigade, veterans of Germantown, Monmouth, and the Valley Forge encampment. The quick response of their officers, supported by the troops of the Pennsylvania Line, forestalled a major rebellion. To prevent further mutinies, Washington continued to plead with Congress for desperately needed food, supplies, and money. A second mutiny occurred at Morristown in January 1781 when Pennsylvania troops marched toward Philadelphia to demand supplies and back pay.

More bad news reached Washington in the late spring of 1780. British and German troops had left Staten Island and were advancing into New Jersey. Having already sent three brigades to protect other areas, he ordered his last six brigades toward Springfield where, in a battle fought on June 23, they forced the enemy to turn back. Within days all troops had departed Morristown, ending the 1779-1780 encampment and Morristown's major role in the Revolution.

The encampment at Morristown in 1779-80 was one of the Continental Army's severest trials. Held together by Washington's leadership and ability, the army survived a time of discouragement and despair. A soldier named Stanton perhaps summed up the significance of Morristown. On February 10, 1780, he wrote a friend: "I am in hopes the army will be kept together till we have gained the point we have so long been contending for. . . . I could wish I had two lives to lose in defense of so glorious a cause."

Exploring the Park

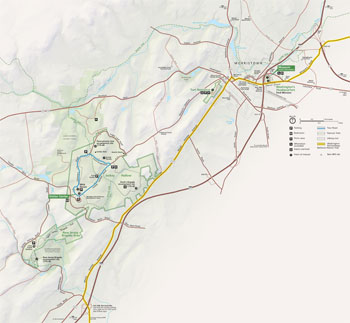

(click for larger map) |

Washington's Headquarters, 1779-80 In early December 1779 Morristown's finest house became a center of the American Revolution. Mrs. Jacob Ford Jr., a widow with four young children, offered the hospitality of her home to General and Mrs. Washington. With the commander in chief came servants, slaves, guards, and aides who assisted in the operation of headquarters. Here General Washington attempted to solve the many problems facing the army. The assistance and support of both the Continental Congress and state governments was needed to clothe and feed the army. Military strategy in the northern and southern theaters had to be worked out with the French. The Ford family, crowded into two rooms of their home, was witness to these activities.

Fort Nonsense In May 1777 this hill swarmed with soldiers digging trenches and raising embankments. Washington ordered the crest fortified because it strategically overlooked the town. The earthworks became known as "Fort Nonsense" because of a later legend that it had been built only to keep the troops occupied.

Jockey Hollow Encampment Area, 1779-80 The Continental Army was a cross-section of America: farmers, laborers, landowners, skilled craftsmen, village tradesmen, and frontier hunters. Almost every occupation and social class were represented. Home for the 10,000 soldiers might be New York, Connecticut, Maryland, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, or even Canada. But their suffering gave them a common bond.

Activity in the encampment began early each day, and often continued until late at night. Inspections, drills, training, work details, and guard duty filled each day. Dogged by hunger and biting cold, the soldiers spent most of their free time huddled around the fireplace. Twelve men often shared one of over 1,000 simple huts built in Jockey Hollow to house the army.

Wick House: St. Clair's Headquarters, 1779-80 The Wick family was prosperous. While many of their neighbors lived in smaller homes, the Wicks lived in a comfortable house whose construction and style reflect New England origins. The surrounding farm included 1,400 acres of timber land and open field. Like all farmers, Henry Wick, his wife, and children worked their land to meet their daily needs. Perhaps more than most small farmers of his day, Henry Wick knew a measure of security and comfort. But war came to this family as it did to many Americans. In 1779-80 Gen. Arthur St. Clair used the Wick house for his headquarters.

Pennsylvania Line Encampment Site, 1779-80 Sugar Loaf Hill housed 2,000 men during the 1779-80 encampment. Around the face of this hillside, lines of crude huts stood in military array. Little in this bleak scene suggested this was the heart of Washington's army. Many of the men encamped here had participated in the 1775 invasion of Canada, contested the 1777 British crossing of Brandywine Creek, and marched into a storm of enemy fire at Germantown.

Grand Parade Military ceremony, training, and discipline were as important to 18th-century army life as they are today. Guard details were assembled and inspected daily on the Grand Parade. A log hut here, known as the Orderly Office, served as the administrative center of the camp. The General Orders were distributed daily from the Orderly Office and all reports were collected there. Visiting dignitaries witnessed ceremonies involving the entire army from the Grand Parade. Training meant marching, drill, inspection, and obedience to orders. The things learned here might mean survival and victory on some distant field of battle.

New Jersey Brigade Encampment Site, 1779-80 About 900 soldiers of the New Jersey Brigade encamped on a steep plot of land two miles southwest of Jockey Hollow. The four regiments comprising the brigade were the last of the army to arrive that winter. They set about building their huts on December 17 and moved into them on Christmas Day. Note: This is a walk-in site only.

For Your Safety Do not allow your visit to be spoiled by an accident. While every effort has been made to provide for your safety, there are still hazards that require visitor alertness. Watch for uneven walking surfaces when in and around historic buildings or on the trails. Avoid poison ivy and protect yourself against ticks and other insects. Keep your pets leashed at all times. Do not feed the animals.

About Your Visit Service animals are welcome in all park areas. Washington's Headquarters at Ford Mansion and the adjacent Museum are open daily. Ford Mansion tours are offered. The Jockey Hollow visitor center and nearby Wick House are open daily, depending upon staff availability. Weather permitting, park roads are open 8 am to sunset. All hours are subject to change. Please contact the park before your visit to learn park hours and Ford Mansion tour times. A fee is charged. The park is closed on Thanksgiving Day, December 25, and January 1.

Preserve Your Park The park's historic and archeological sites are fragile resources. Please treat them with respect. The collecting of objects is prohibited. The use of metal detectors and digging for relics are also prohibited.

For firearms laws and policies, see the park website.

Source: NPS Brochure (2013)

|

Establishment

Morristown National Historical Park — July 4, 1933 (established) |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

1779-80 Encampment: A Study of Medical Services (Ricardo Torres-Reyes, April 1971)

Alternative Transportation Study, Morristown National Historical Park (Jonah Chiarenza, Ben Bressette and Rachel Chiquoine, April 9, 2020)

An Inventory of Terrestrial Mammals at National Parks in the Northeast Temperate Network and Sagamore Hill National Historic Site U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2007-5245 (Andrew T. Gilbert, Allan F. O'Connell, Jr., Elizabeth M. Annand, Neil W. Talancy, John R. Sauer and James D. Nichols, 2008)

Archeological Collections Management at Morristown National Historical Park, New Jersey Archeological Collections Management Project Series No. 2 (Alan T. Synenki and Sheila Charles, 1983)

Assessment of Vegetation in Six Long-Term Deer Exclosure Investigations at Morristown National Historical Park: Data Synthesis & Management Recommendations NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/MORR/NRR-2020/2176 (Jean N. Epiphan and Steven N. Handel, October 2020)

Booklet: Morristown National Historical Park (1946)

Camp Buildings in Jockey Hollow, 1780 (S. Sydney Bradford, 1961)

Census of Markers of Historic Sites, Morristown, New Jersey and Vicinity (V.G. Setser, 1935)

Changes in the Forests of the Jockey Hollow Unit of Morristown National Historical Park Over the Last 5-15 Years NPS Technical Report NPS/BSO-RNR/NRTR/2002-9 (Emily W.B. (Russell) Southgate)

Cultural Landscape Report for Washington's Headquarters, Morristown National Historic Park: Introduction, Site History, Existing Conditions, Landscape Analysis (Christopher M. Stevens, 2005)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory, Cross Estate, Morristown National Historical Park (1998)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory, Fort Nonsense, Morristown National Historical Park (1998)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory, Jockey Hollow, Morristown National Historical Park (1999)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory, Washington's Headquarters, Morristown National Historical Park (1995)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory, Wick Farm, Morristown National Historical Park (2009)

Development Concept: Washington's Headquarters Unit, Morristown National Historical Park, New Jersey (1973)

Draft Master Plan, Morristown National Historical Park, New Jersey (May 1974)

Final Construction Report: Restoration of Tempe Wick House and Outbuildings, Jockey Hollow, Morristown National Historical Park, New Jersey (Daniel C. Jensen, August 1935)

Foundation Document, Morristown National Historical Park, New Jersey (June 2018)

Foundation Document Overview, Morristown National Historical Park, New Jersey (June 2018)

Furnishing Plan for the Ford Mansion (Sherman W. Perry and Ted C. Sowers, 1964)

Furnishing Plan for The Ford Mansion (1779-80), Morristown National Historical Park (Vera B. Craig and Ralph H. Lewis, 1976)

Furnishing Plan for the Wick House, Morristown National Historical Park (1962)

Furnishings Plan for the Wick House (June 1974)

General Management Plan and Environmental Impact Statement, Morristown National Historical Park (2003)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Morristown National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2014/841 (T.L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, August 2014)

Historic Buildings Survey Report: Wick House, Morristown National Historical Park (Part I) (Walter E. Hugins, September 20, 1958)

Historic Furnishings Assessment, Morristown National Historical Park, Morristown, New Jersey (December 2003)

Historic Structures Report/Administrative Data: Ford Mansion, Morristown National Historical Park (Part I) (September 1963)

Historic Structures Report/Architectural Data Section: Preliminary to the Rehabilitation of the Wick House, Morristown National Historical Park, Jockey Hollow, Morristown, N.J. (Part II) (Thomas Wistar, Jr., June 1959)

Historic Structures Report: Ford Mansion, Morristown National Historical Park (Part III) (Sherman W. Perry, 1965)

Historic Structure Report: Museum Building, Morristown National Historic Site, Volume I (Maureen K. Phillips, August 2007)

Historic Structure Report: Museum Building, Morristown National Historic Site, Volume II (Maureen K. Phillips, 2007)

Historic Structures Report: Wick House, Morristown National Historical Park (Part I) (Bruce W. Stewart, August 15, 1962)

Historic Structures Report: Wick House — Termite & Powder Post Beetle Treatment, Morristown National Historical Park (Part I) (Sherman W. Perry, November 1964)

Historic Structures Report: Wick House — Termite & Powder Post Beetle Treatment, Morristown National Historical Park (Part III) (Sherman W. Perry, 1965)

Historical Data Investigation: The Jacob Ford, Jr. Mansion, Washington's Headquarters (Robert P. Guter, July 1983)

Historical Grounds Survey of Washington's Headquarters, The Ford Mansion, Morristown, New Jersey (William U. Massey, May 20, 1975)

Inventory of Structures: Morristown National Historical Park Cultural Resources Management Study No. 14 (David Arbogast, 1985)

Junior Ranger Booklet, Morristown National Historical Park (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Morristown National Historical Park (January 2007)

Medicine and Surgery during the American Revolution (Morristown Memorial Hospital, 1982)

Morristown National Historical Park, New Jersey: A Military Capital of the American Revolution: Historic Handbook No. 7 (Melvin J. Weig and Vera B. Craig, 1950 reprint 1961)

Morristown Winter Encampment 1777 (Lenard E. Brown, June 30, 1967)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Morristown National Historical Park (Ricardo Torres-Reyes, October 5, 1978)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Morristown National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NERO/NRR-2014/869 (Rebecca Wagner, Charles Andrew Cole, Larry Gorenflo, Brian Orland, Ken Tamminga, Margaret C. Brittingham, C. Paola Ferreri and Margot Kaye, October 2014)

New Jersey Brigade Encampment Site: A Special Study (John F. Luzader, November 6, 1968)

Newsletter (Morristown Muster) (Fall 2012)

Quartering, Disciplining, and Supplying the Army at Morristown, 1779-1780 (George J. Svejda, February 23, 1970)

Recovery of Native Plant Species After Initial Management of Non-Native Plant Invaders: Vegetation Monitoring in an Exclosure in Morristown National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/MORR/NRR-2020/2168 (Joan G. Ehrenfeld, Kristen A. Ross, Manisha Pagtel, Jean N. Epiphan and Steven N. Handel, August 2020)

Report on Design of Flag Flown at Washington's Headquarters, Morristown, New Jersey, During the Winter of 1779-80 (Alfred F. Hopkins, September 1940)

Report on Fort Nonsense, Morristown National Historical Park (V.G. Setser, August 24, 1933)

Report on Historical Data on the Wick Homestead Collected to April 1, 1934 (Clifford R. Stearns, 1934)

Report on the Furnishing of the Wick House (Historical Files) (Vernon G. Setser and Lloyd W. Beibigheiser, 1935)

Report on the Location and Size of the Revolutionary Cemetery (Clifford R. Stearns, July 7, 1934)

Report on the Restoration of the Wick House, Morristown, N.J. (Thomas T. Waterman, 1940)

The Building of Fort Nonsense (Wesley R. Savadge, March 1940)

Trajectory of Forest Vegetation Under Contrasting Stressors Over a 26-Year Period, at Morristown National Historical Park: Focused Condition Assessment Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/MORR/NRR-2023/2500 (Jean N. Epiphan and Steven N. Handel, March 2023)

Vegetation of the Morristown National Historical Park: Ecological Analysis and Management Implications Final Report (Joan G. Ehrenfeld, December 1977)

Washington's Headquarters: Its History and Restoration (Melvin J. Weig, September 1939)

Water Resources Scoping Report: Morristown National Historical Park NPS Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-93/17 (October 1993)

White-tailed Deer Management Study, Morristown National Historical Park (Roderick G. Christie and Mark W. Sayre, March 1989)

Wick House Furnishing Study, Morristown National Historical Park (Ricardo Torres-Reyes, April 1971)

Wild Land Fire Management Plan, Morristown National Historical Park (Deb Nordeen, 2005)

Morristown, New Jersey - Jockey Hollow - Morristown National Historical Park (in HD, 2012)

morr/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025