|

Navajo

A Place and Its People An Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER II:

FOUNDING NAVAJO NATIONAL MONUMENT

The establishment of Navajo National Monument was a direct result of the professionalization of science in the U.S. and the move by Anglo-Americans in the late nineteenth century to settle the Southwest. As more and more people came to the region, the subsurface and above ground ruins of prehistoric cultures fell prey to callous and avaricious hands. Prehistoric pots were smashed for sport and the walls and building stones of ruins were dismantled for use in newer structures. In the era of the end of American perception of a westward frontier, it seemed to many that the remnants of an important cultural heritage were being wantonly destroyed.

Nowhere was this feeling stronger than among the denizens of the subfields of anthropology and archeology. Beginning with the founding of the Bureau of Ethnology in 1879, interest in American prehistory grew in influential circles. By the 1890s, with the end of the frontier accepted as dogma, concern for the preservation of the past gained momentum. For aspiring professionals in the twin fields of anthropology and archeology, the preservation of antiquities offered a crucible in which to prove the value of their work to the scientific community and the public at large. [1]

The study of prehistoric and American Indian people had great value to Americans at the end of the nineteenth century. Since the end of the Civil War, American society had been transformed by industrialization, seemingly overrun with immigrants, and appeared to have lost much of the democratic virtue the founding fathers envisioned. The last decade of the century embodied a search for order that became the Progressive movement. Using the theories of Lewis Henry Morgan, the founder of modern anthropology in the U.S., anthropologists and archeologists could present the scholarly study of Indians and their prehistoric antecedents as affirmation that the world had not gone haywire. In the long view, they asserted, this evolutionary stage, however dislocating and uncomfortable, provided evidence of the superiority of the American achievement. [2]

Simultaneously, a rush to conserve the natural resources of the American West began. The general acceptance of the end of the frontier meant that the idea of scarcity entered the American lexicon. A nation with no more room to expand had to more wisely use the resources available to it. The "wear-out-the-farm-and-move-on" ideal of the nineteenth century ceased to be acceptable as legislators and officials in government agencies began to pay closer attention to the management of resources. Legislation such as Amendment 24 of the General Revision Act of 1891, which allowed the president to establish forest reserves (national forests) from the public domain with the stroke of a pen, was one kind of result. Stepped-up efforts by the General Land Office of the Department of the Interior to survey and assess the resources of federal lands in the Southwest and West was another.

This move resulted in greater awareness of the vast quantity of prehistoric remains in the Southwest at the very moment federal officials began to implement systematic programs to manage and administer western resources. Conservation, the idea of wise use, gained a strong following in the federal bureaucracy long before it emerged as a priority of Theodore Roosevelt's administration. Under this loose rubric, there was also room for the preservation of prehistory. Beginning in the 1890s, there were piecemeal efforts to preserve individual ruins. One such measure authorized the Casa Grande Ruin Reservation in 1889. With the influence of prominent easterners and the power of John Wesley Powell, head of the Bureau of American Ethnology, an entity established to promote understanding of native cultures, the move to preserve prehistory gathered momentum. Anthropologists and archeologists hurried to the Southwest to experiment with their waiting crucible.

Ironically, at the beginning of an era stressing the management of natural resources by trained experts, there were no laws that protected other kinds of treasure in the West. Experts similar to those who clamored for regulations in forestry and hydrology competed vigorously for access to prehistoric artifacts and structures to enhance the position of their institution among its peers. Blind to conflict of interest and resulting depredation, federal and private excavators hurried to enhance their personal reputations. While natural resources required scientific management to insure fair distribution and continued availability, non-renewable cultural resources were pillaged wholesale. Issues of public good had not yet emerged from the chaos of the transition to an industrial society.

Many people dug in ruins in search of profit, but one man came to epitomize the exploitation of American prehistory. Richard Wetherill, a rancher from Mancos, Colorado, discovered Cliff Palace Ruin while in search of a stray calf in the Mesa Verde region of southwestern Colorado in December 1888. His appetite whetted, Wetherill found many more such places in the weeks and months that followed. He lived a hardscrabble existence prior to his discovery, eking out a living for his extended family with the less-than-profitable family enterprise, the Alamo Ranch. By all accounts an intelligent if stubborn and iconoclastic person, Wetherill became obsessed with the lost civilization he found. He excavated first for his own edification, later for commercial ends. In 1892, he and Gustav Nordenskiold of Sweden made a collection of artifacts that returned to Europe with Nordenskiold. Jingoistic Americans pointed to this as purposeless despoliation of the American past for the gratification of European sensibilities, and Wetherill became the focus of the anger of different groups. Unconcerned with the clamor of easterners and unaffected by derogatory remarks, he ignored their complaints and continued to dig.

A complicated web soon encompassed Wetherill. Because he was a westerner and was familiar with the desert Southwest, he had much to offer anyone interested in making collections from ruins. Wetherill's services were for sale, and among those who hired him were Talbot and Frederic Hyde, the heirs to a soap fortune who donated what they found to the American Museum of Natural History in New York. In the eyes of many in the scientific community, this relationship gave the museum an unfair advantage in the race to assemble museum collections. Institutions and individuals allied with Wetherill had better access, and those who did not assailed them for that advantage.

As anthropologists and archaeologists developed scientific standing, Wetherill became a threat to their future. To proto-professionals with something to prove, Wetherill became anathema. He had both the knowledge and the desire to thwart them. Wetherill knew the location of more southwestern ruins than any living Anglo, and he neither hesitated to dig nor deferred to the scientists of his time. With motives inspired in part by fear and jealousy, anthropologists and archaeologists were outraged by Wetherill's actions. To protect its growing interests, the scientific community galvanized against him. Scientists redefined their terminology to create a category for Wetherill. After Wetherill excavated Chaco Canyon, another extraordinary prehistoric area, the derogatory label of "pot-hunter" was attached to his name.

The specter of Richard Wetherill haunted American archeology. As a result of his widespread digging and the cottage industry that developed around it, the scientific community pressed for legislation to protect American antiquities. After a six-year battle, "An Act for the Preservation of American Antiquities," more commonly known as the Antiquities Act, became law in 1906. This allowed the president to create from public land a new category of reserved areas, the national monuments. Like the provisions to reserve forest land, the Antiquities Act gave the chief executive unchecked power over the federal domain.

Despite its amorphous nature, the Antiquities Act proved a useful tool for the preservation of lands in the West. Although also used to reserve great natural areas such as the Grand Canyon and the Olympic Mountains, it was well-suited for archeological preservation. Between its passage in 1906 and the end of 1908, it became the authorizing legislation for eight national monuments, three of which were archeological in character. One of these, Chaco Canyon National Monument, was established at least in part to thwart Richard Wetherill's homestead claim at Pueblo Bonito, the largest of the ruins. [3]

Wetherill and his family also had a history on the Tsegi Plateau. The Wetherills first visited the region early in 1893. Although the clan traveled through Marsh Pass, they did not stop. Two years later in December 1894 and January 1895, another Wetherill family group came to the western reservation. The group of eight men and twenty animals split into three. One team, comprising Richard Wetherill, his brother Al, and brother-in-law Charlie Mason, came south from Utah through Monument Valley to Marsh Pass. From Marsh Pass, they followed Laguna Creek up Tsegi Canyon, excavating the small mounds they found along the way. When the three reached the finger-like canyons of the Tsegi, Richard Wetherill chose one of the central branches, unaware that it led toward a spectacular prehistoric ruin.

The choice seemed at first a mistake. As the party followed the streambed as it gradually rose through the canyon, they saw no sign of human habitation. A chain of lagoons and waterfalls spread out over a few miles offered essentials for life, and wild ducks among the reeds and grasses meant an opportunity to hunt. But in search of prehistoric sites, the party appeared to have little luck.

Richard Wetherill's lead mule, Neephi, was responsible for a change in their fortunes. One night, the mule broke his hobbles and wandered off. In the morning, Wetherill followed. In a serendipitous repeat of his good fortune half a decade before at Mesa Verde, he rounded a turn in the canyon and suddenly in front of him appeared a large eye-shaped cave with a large cliff dwelling stretching from side to side. The cave was enormous, the structures within every bit as impressive. Again Wetherill had stumbled on one of the prizes hidden in the wilds of the Southwest.

With this previously unexcavated gem at their disposal, the party decided to stay. They spent four or five days at the ruin, later called Keet Seel, "broken pottery" in the Navajo language, performing a preliminary survey of the rooms and noting a number of features. Yet in keeping both with his personal interest and the dominant mode of thought concerning ruins at the time, Wetherill perceived an extraordinary opportunity to make a collection of artifacts. When the party returned, he contacted his benefactors, the Hyde brothers, and made plans for an expedition. But the expedition never materialized, as Talbot Hyde's interest in Chaco Canyon superseded Richard Wetherill's desire to work in the Tsegi. [4]

The commercial dimension of his work in archeology was important to Wetherill, but he also fell in the tradition of talented amateurs that has characterized the archeological profession. Like Heinrich Schliemann, the discoverer of Troy, Wetherill had no training but great interest. Unlike Schliemann, he lacked a personal fortune. Avid in his interest, he also needed to make a living from his work. [5]

As a result, Richard Wetherill had to depend on his backers. He was not wealthy and could not afford either an unsuccessful or an unsupported expedition. Despite his desire to excavate and understand the prehistoric Southwest, he was an economic being. He worked on the projects the people who supported his work chose. With a wide range of backers and explorers who sought to make collections, Wetherill dug many other archeological sites. He could afford to wait to return to Keet Seel. Of all the potential excavators roaming the Southwest, he was the only one who knew where it--and hundreds of other places like it--were.

In 1897, as part of an expedition with both intellectual and commercial objectives, Richard Wetherill brought another party to Keet Seel. Rumors that the Field Columbian Museum planned a winter exhibition into the Grand Gulch area in southern Utah prompted Wetherill to try to organize his own. Again he contacted the Hyde brothers; again their interest in Tsegi Canyon did not match his own. But George Bowles, the scion of a wealthy eastern family, and his tutor, C. E. "Teddy" Whitmore, arrived in Mancos with the desire to have an adventure. Richard Wetherill was only too pleased to direct their interest toward Grand Gulch, Utah, and Keet Seel.

The expedition began its work in search of basketmaker relics in Grand Gulch. Wetherill's prior discovery of these pre-pueblo people whetted his desire to document their existence. After fulfilling this intellectual pursuit, Wetherill divided his party and headed toward Marsh Pass. He sought to return to Keet Seel, where he promised his sponsors they would find more pottery than their animals could carry out. They dug throughout the ruin, making a large collection.

At the end of their stay, Bowles and Whitmore were kidnapped and held for ransom by a nearby band of Paiute or possibly Navajo Indians. Wetherill had to send to Bluff City, Utah, for silver to buy back the prisoners. The exchange was made, and within a few hours, the two haggard young men returned to the camp after nearly four days in captivity, their appetite for adventure satiated. [6]

Despite the activities of Richard Wetherill and other explorers, the four corners area remained remote. The Navajo reservation dominated the region, and even as railroads were constructed and places such as the Grand Canyon began to attract the attention of American travelers, the amenities that brought American visitors skirted the boundaries of the reservation. The northeastern corner of the Arizona Territory remained out of the mainstream. Archeological work continued, but it remained one of the few places in the continental U.S. that had not been surveyed. Well into the first decade of the new century, few people had any idea what was out there among the sandstone mesas.

But commercial culture began to make inroads into even the most remote areas of the Navajo reservation. In the years following 1880, trading posts started to emerge on the reservation, offering Navajos a new way to survive. After the return from Bosque Redondo in 1868, the Navajo subsistence economy narrowed. Raiding other tribes and the New Mexico Territory were forbidden, and the American military stood by to enforce its edict. Soon after, another Navajo subsistence method, hunting wild game, ceased to be effective. Tremendous growth in the number of livestock eliminated much wild range, and without it, Navajos needed another source of sustenance to protect against crop failure. Traders who paid for Navajo rugs and blankets provided a final measure of protection against failure of other methods of survival. [7]

Among the traders who engaged in this commerce with the Navajo were Richard Wetherill's brother John, his wife Louisa Wade Wetherill, and their partner, Clyde Colville. In March 1906, they established a trading post near Oljato, Utah, after a feast John Wetherill prepared to assuage the fears of Old Hoskininni and his son Hoskininni-Begay, the acknowledged leaders of the Navajo people in the immediate area east of Navajo Mountain. From the door of their "jacal" home of posts and mud and adjacent one-room trading post, it was more than 150 roadless miles to the nearest railway stop in Gallup, New Mexico, and nearly as far to Flagstaff, Arizona. [8] This enterprise was an outpost, far from any ties to industrial society.

Nor was the experience new to John and Louisa Wade Wetherill or Clyde Colville. The Wetherills had opened their own trading post a few years before at Ojo Alamo, a few miles north of Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon. There Louisa Wade Wetherill began to befriend the Navajo people and learn their language. Clyde Colville arrived from the East, broke, in search of adventure, and crowned with a derby hat. The tall, thin, and quiet man worked as a clerk at Ojo Alamo, and he and the Wetherills became partners for life. [9]

Because of the distance between Oljato and the nearest trading posts, all more than sixty miles away, the trading post allowed the Wetherills time to pursue their interests. Like the rest of the Wetherill clan, John Wetherill was consumed with prehistory. The Anasazi and their abandoned communities continued to be uppermost in his mind. The people around them, the Navajo, remained the fascination of Louisa Wade Wetherill, who by 1906 spoke their language fluently. They each had their area of expertise, and neither would cross the other. Even their children knew to respect the staked-out claim of their mother. [10]

As the area attracted the attention of explorers and government representatives, the trading post at Oljato became a center for Anglo travelers to the region. John Wetherill had a store of knowledge about prehistoric sites nearly equal to that of his brother Richard and was available as a guide or outfitter for expeditions. Among them were two figures critical in the establishment of Navajo National Monument, Byron L. Cummings, then of the University of Utah, and William B. Douglass, Examiner of Surveys for the General Land Office of the Department of the Interior.

The diminutive and round-faced Byron L. Cummings was one of the most distinguished and revered figures in the first generation of American archaeology. He grew up in New York and New Jersey, coming to the University of Utah in 1893 to accept a position as Professor of Classics. By 1905, he had become dean of the faculty, and began to pursue his interest in archeology. In 1906, he initiated his first excavation. [11] Like another prominent western archeologist of his time, Edgar L. Hewett, Cummings was self-trained. Only his university affiliation protected him from the charges of pot-hunting leveled at Richard Wetherill.

William B. Douglass represented the Progressive ideology that had swept the country since Theodore Roosevelt became president in 1901. This movement, with its twin goals of equity and efficiency, sought to restore a measure of order to a society that had rapidly changed since the onset of industrialization. Douglass was a field employee of the General Land Office, the branch of the federal government responsible for the management of public lands and which had started to take an interest in the cultural and natural features of the western landscape, and he embodied the growing trend towards regulation evident in American society. He perceived unprotected ruins and resources to be at risk from the uncaring and malicious actions of those who placed their own welfare ahead of that of the American people. Like many progressives, Douglass believed that he and his professional peers were entitled to make rules, but the very regulations they made applied only to other people.

This self-serving perspective characterized government officials for many who lived in the West. Despite a number of prominent western leaders such as U.S. senator Francis Newlands of Nevada, most westerners regarded federal efforts to regulate the use of western resources as intrusive. They lived in an open land, many thought, and any restriction impeded their ability to earn a living.

Within a year of each other, Cummings and Douglass began to explore the western Navajo reservation. In 1907, Cummings and his party prepared a topographic map of White Canyon, the area that included three natural bridges that became Natural Bridges National Monument in the spring of 1908. Shortly afterward, the GLO sent William B. Douglass back to resurvey the area in an effort to more precisely define its boundaries. He spent most of the summer and fall at that task. Two men with different objectives were in each other's proximity.

In the summer of 1908, Byron L. Cummings continued his archeological work in the southeastern Utah-northeastern Arizona region. Upper Montezuma Canyon was the focus of the expedition, and a small excavation at Alkali Ridge introduced Alfred V. Kidder, who became a leader in the field, to archeology. After the field work ended, Cummings and John Wetherill planned to explore the ruins of northeastern Arizona. Wetherill could not come along because of a dispute between Navajos from Oljato and the U.S. Cavalry. Cummings and two students, one of whom was his nephew Neil Judd, later an important archeologist in his own right, headed for Tsegi Canyon. Although the party never reached the area, it visited numerous ruins on the way. But the Tsegi area intrigued Cummings and he planned to return the next year. [12]

The peripatetic Edgar L. Hewett also visited the region in the summer of 1908. As the head of the School of American Archeology in Santa Fe, the only southwestern arm of the Archaeological Institute of America, and the author of the Antiquities Act, Hewett wielded tremendous power in the Southwest. He regularly applied for excavation permits for a dozen or more sites in the region, visiting most of them only once a season. Among his travels in 1908, he joined up with the Cummings expedition at Alkali Ridge and a few days after a group of miners visited Keet Seel, went there with John Wetherill. [13]

A growing gulf between Hewett and Cummings on one side and Douglass on the other was beginning to emerge. It stemmed from questions about access to ruins. Hewett and Cummings were westerners who understood the ways of the twentieth century. They recognized that they would have to cooperate with the institutions of American society if they were to excavate. The furor over the activities of Richard Wetherill, in which Hewett played a prominent role, certainly showed that there was no future in challenging the system. After successfully labeling Wetherill a pot-hunter, Hewett sought to consolidate his position in the archeological world. Offering expeditions, training students, and making collections for museums was the best way to achieve this goal.

In the view of people like Douglass, this went against the best interests of science. Collections were being taken from government land by anyone who happened along, and despite the cessation of Richard Wetherill's activities, Douglass could see no reason that Hewett, Cummings, or anyone else should continue the same practice. He lamented the number of collections made on federal land, arguing that if ruins were to be reserved, it ought to occur before the subsurface treasures were taken and parceled out to the highest bidder. In his view, there was little difference between the results of one of Wetherill's forays and Hewett's expeditions.

Douglass envisioned a system that offered accredited government scientists the first opportunity to explore and catalog ruins. This perspective reflected the values of the federal resource bureaucracy during the Progressive era. Rather than let the greedy appropriate artifacts for their own edification, such places should be preserved for the benefit of all Americans. From Douglass' perspective, this was a much better solution than simply allowing anyone with university affiliation to take what they wanted from the public domain.

After Douglass finished in White Canyon in October 1908, he continued to search out important features for preservation. From his base in Bluff, Douglass headed for Oljato in early December. He hoped to find John Wetherill and hire him as a guide. Wetherill could not leave the trading post, for the weather was bad and supplies there were low. Douglass engaged Sam Chief, a Navajo medicine man reputed to speak two languages. Later Douglass discovered "to [his] sorrow they were both Navajo." [14]

The two men became enmeshed in a serious communications problem. Douglass wanted to see specific ruins, but Sam Chief thought any ruin would suffice. When Douglass was able to make his objective clear, Sam Chief told him that because of the heavy snow, they would have to wait. When other Navajos they met corroborated Sam Chief's contentions, Douglass decided to try to wait it out. Clyde Colville persuaded him that the snow would remain until spring. Douglass gave up and returned to Bluff to wait for the end of winter.

But Douglass did acquire a wealth of information about natural bridges and ruins on this abbreviated trip. Mike's Boy, a Paiute Indian known as a guide, told him of a bridge near Navajo Mountain and of a number of ruins in the Tsegi Canyon area. Douglass had Mike's Boy show him the approximate location of the ruins and the bridge on a map, which he then sent to Washington, D.C.

This map became the basis for the original boundaries of Navajo National Monument. Aware of the ease with which national monuments could be established, Douglass set out to reserve the important ruins of the western reservation. In an exchange of telegraph and letters, he persuaded the Commissioner of the General Land Office to request the proclamation of a new reserved area--sight unseen. [15]

Douglass had not yet been to the ruins of the Tsegi. He had only the description of location and appearance given him by Mike's Boy and corroborated by John Wetherill. Yet in Douglass' view, the threat of depredation was sufficiently great to demand such a proclamation. Seemingly unaware of Richard Wetherill's prior visits, Douglass saw the ruins of Tsegi Canyon as one of the last archeological areas that had not yet been looted. To assure that it stayed that way, he advocated referring the request of anyone who wanted to excavate or visit to the Smithsonian Institution before allowing them to proceed. The specter of Richard Wetherill still loomed large over American archeology and the federal land management bureaucracy.

Douglass also made rudimentary arrangements for protection of the new monument. There were only two ways to get to the ruins. Travelers could come down through John Wetherill's trading post at Oljato and follow the roughly forty miles of trail or they could follow a wagon road from Gallup, New Mexico. John Wetherill's trading post was the only stopping place for miles in any direction; he had selected its location for precisely that reason. Douglass could not see how anyone could expect to find the ruins without Wetherill's help. He enlisted Wetherill as a volunteer custodian, a so-called "dollar-a-year-man," who in reality received one dollar each month. [16]

On March 20, 1909, President William Howard Taft signed into law proclamation 873, creating Navajo National Monument, the twentieth national monument created since the passage of the Antiquities Act less than three years before. The 160-square-mile unsurveyed monument was not unusual during this time period. There were a number of precedents for such a seemingly arbitrary use of presidential authority. Since the executive power to create national forests was abrogated in 1907, the Antiquities Act had become a more widely used tool. Only weeks before, in his last hours in office, Theodore Roosevelt tweaked Congress's nose by establishing nearly 700,000 acres of the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State as Mount Olympus National Monument. In comparison to such actions, the reservation of an area outside the path of commercial development, as yet mostly unsurveyed, and containing important archeological ruins, did not seem excessive. [17]

But other than Wetherill's part-time post, there were no other provisions for care of Navajo or any of the other national monuments. As a typical piece of Progressive era legislation, the Antiquities Act embodied the preconceptions of its time. The framers of the act thought that passage of law would assure compliance on the part of citizens. They failed to include measures to fund protection. Consequently, care was uneven.

Douglass had a number of reasons for insisting on immediate proclamation of the monument. He feared the arrival of Cummings' expedition, which he termed a "pseudo-scientific party with strong political backing" in the coming months. Douglass was certain they planned to make a large collection from the ruins, using untried and poorly trained students. He expected the ruins of Tsegi Canyon to be among the last undisturbed ruins discovered, and in his view, their value to archeological science was too great to leave them to a group interested mainly in collecting artifacts.

As a result, he arbitrarily requested the reservation of an area even he recognized was far larger than necessary to protect the ruins. Douglass knew that the government had no real way to protect remote places without formal reservation. The large quantity of land was necessary because he had not yet been to the Tsegi Canyon area. But he could not afford to wait, for the party of excavators was on the way. [18]

The result was a monument far too large for permanence that excluded the then undiscovered ruin of Inscription House. Douglass followed the descriptions of locations he had as of early March 1909. The general reservation would suffice as a protective measure until he could visit the area and determine what ought to be in the monument and what could be released to the public domain.

Although he was more than forty miles away, John Wetherill made an effective custodian. Like his older brother, he knew the trails better than any other Anglos around, and he remained the main outfitter and guide for anyone who sought to find ruins or even needed supplies. The trading post at Oljato was a meeting place for travelers, explorers, the military, and area Navajos. If anyone visited the monument from the north, they would have to pass through Oljato.

Wetherill was also closely tied into the Navajo grapevine. Both he and Louisa Wade Wetherill were almost honorary members of the tribe; in 1906, Hoskininni had claimed Louisa Wade Wetherill as his granddaughter because of her fluency in the Navajo language and upon his death, he willed her his thirty-two slaves. American law abolishing slavery had little impact on the actions of Navajos who barely acknowledged of the existence of Anglo-Americans. Even if someone left Gallup for the ruins without coming in contact with one of Wetherill's friends or business contacts, by the time they reached Marsh Pass, the Wetherills or Clyde Colville would know of their arrival.

John Wetherill took his responsibilities as custodian seriously. When he accepted the job, he requested permission to compel unauthorized excavators to cease or be arrested. The ruins were important to him, and perhaps influenced by the cessation order handed his brother at Chaco Canyon, John Wetherill worked with the burgeoning federal bureaucracy. [19]

The summer of 1909 was busier than he expected. Thwarted by circumstances the previous year, Cummings and his crew returned to northern Arizona for a third summer. They headed for Tsegi Canyon. John Wetherill served as their guide. He did not object because the expedition held a permit issued to the School of American Archeology, Edgar L. Hewett's branch of the Archaeological Institute of America. Hewett visited in the course of the summer, something of a surprise considering the number of permits he held as well as the field schools he ran at Frijoles Canyon and Puye near the Rio Grande in north central New Mexico. [20]

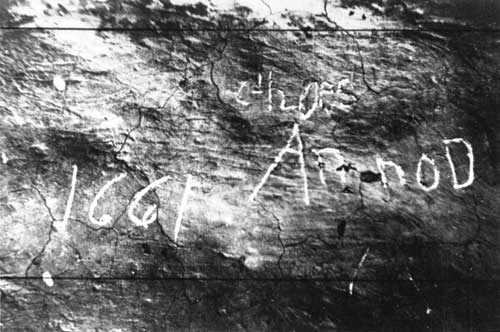

That summer, the Cummings party set up at the site they knew best: Keet Seel, the place of the broken pottery. After working there until July, John and Louisa Wade Wetherill took Cummings, his eleven-year-old son Malcolm, their children Ben and Ida Wetherill, and a student photographer from the University of Utah named Stuart Young forty miles to the west, toward Nitsin Canyon. There Pinieten, a Navajo who regarded the area as his own, offered the party hospitality. Following Wetherill's guidance, they found another set of ruins. Curious about the ruins, the three children did some exploring of their own. Scratching away debris from the walls of one of structures, they discovered an inscription that appeared to read: Anno Domini 1661. Excited at the thought that the Spanish might have preceded them in Nitsin Canyon, they named the place "Inscription House." [21]

|

| The controversial inscription at Inscription House ruin, circa 1915. |

After a stop at Keet Seel, the group planned to return to Oljato. They passed by the hogan of Nedi Cloey at the fork of the canyon, and his wife hailed Louisa Wade Wetherill. When she found that they sought Anasazi ruins, she told them of a large ruin up the canyon that her children came across while herding sheep. Only two miles from the ruin, the party wanted to visit it, but their horses were too tired and weak. John Wetherill hired Clatsozen Benully, Nedi Cloey's son-in-law, to take a group of six to the ruin on August 9, 1909. It was a short trip, about thirty minutes, to find the ruin. They named it "Betat' akin," Hillside House, lingered an hour, and then went on to Oljato to fulfill their other objectives. [22]

|

| This photo from 1909 shows how Betatakin appeared to the first parties that arrived in the canyon. |

One of Cummings' principal goals for the summer of 1909 was an attempt to reach Rainbow Bridge, near the Utah-Arizona border. The bridge had been reported by Mike's Boy, the Paiute guide, and others, and with the three natural bridges in the vicinity established as Natural Bridges National Monument in the summer of 1908, considerable prestige could be the reward of the discoverer of another one. Cummings was less concerned with prestige than with scientific knowledge, but nonetheless the prospect of adding to his knowledge of the region was enticing.

But William B. Douglass reappeared in northeastern Arizona, altering Cummings' plans. John Wetherill left Tsegi Canyon for Bluff before the trip to Betatakin. There he met Douglass, who planned to survey the national monument proclaimed earlier in the year. Douglass also planned to check on the Cummings' party. Because their permit had been issued to Hewett, who was only present intermittently, the group was technically in violation of the Antiquities Act. Douglass planned to confiscate their artifacts and force them to cease any archeological activity in which they were engaged. He had already been in contact with the Smithsonian Institution, which had issued the permit. Wetherill tried to talk Douglass out of this notion, but failed. He returned to Tsegi Canyon to give Cummings the bad news. [23]

The brewing conflict had finally come to a head. Cummings represented the first generation of archeologists, those who had cut their professional teeth in the pot-hunting disputes with Richard Wetherill. In their view, Cummings, Hewett, and their peers were clearly different from the cowboy from Mancos. The collections they made were for the sake of knowledge, not to be sold to anyone who wanted them. They were professionals, advancing their field and not incidentally their individual careers.

Douglass took a different view. While he understood the difference in intent, he saw the effect of one of Richard Wetherill's excavations and one of Cummings' as the same. In both cases, prehistoric structures were less important than subsurface artifacts; nor was documentation available to the interested public. Excavators made little effort to preserve the sites they dug. From Douglass' perspective, these kinds of excavations of federal property amounted to vandalism, no matter who was behind them. In effect, Douglass applied the "pot-hunter" label to the very people who coined the phrase. With both he and Cummings in the area, trouble was certain to ensue.

John Wetherill cast himself as the peacemaker. He knew better than anyone that there were enough prizes to go around as well as the consequences of fighting the growing power of federal officials interested in western land and resources. He reasoned that the two men could resolve their differences if they met face to face. Aware of the trip to Rainbow Bridge, Douglass asked to join the group. Although he arrived at Oljato after the group left for the bridge, Cummings returned for Douglass, and representatives of two distinctly different perspectives on the disposition of American prehistory traveled together to find yet another unique feature of the southwestern landscape.

It must have been a tense trip, for Wetherill was never successful in his attempt to orchestrate an accord between Douglass and Cummings. The group pushed forward under the guidance of Nashja-begay, a Paiute guide in Cummings' employ, seeing the bridge in the distance on August 14, 1909. Douglass sought to be the first white underneath the bridge, an honor that Neil Judd, another of the members of the party, felt should go to Cummings. John Wetherill made the issue a moot point when he spurred his horse ahead of Douglass and the others and passed under the arch first. [24]

The trip to Rainbow Bridge has become more myth than history, but much of the story is not in dispute. Clearly Wetherill and Cummings resented the appearance of Douglass, whose ability to force the expedition to cease their work was of utmost concern. Douglass behaved in a heavy-handed, self-important manner. Judd, Cummings, and Louisa Wade Wetherill all portray Douglass as an interloper who sought to supersede other, more knowledgeable explorers more worthy of credit. Cummings' account, published long after Douglass' death, openly disparaged Douglass. Cummings asserted that Douglass not only attempted to usurp credit for discoveries, he patronized the members of the expedition after imposing on their hospitality. "Of what thin material some men are made," Cummings wrote the Wetherills in reference to Douglass after hearing of the latter's claim that he discovered Rainbow Bridge. Only Judd grudgingly allowed Douglass respect for his desire to protect the ruins from depredation. The rest perceive him as self-serving bureaucrat, and in the lore of the early days of American archeology, William B. Douglass became the villain. [25]

Yet a more balanced look at the evidence suggests that the territoriality that characterized American archeology was a major contributing factor to the disdain showered on William B. Douglass. Despite the evident hospitality shown him by Cummings and Wetherill, Douglass believed his duty compelled him to stop the expedition. He clearly advocated preservation of ruins and natural features for the benefit of the public and exploration by accredited scientists. What made him wary was the emphasis on collecting that pervaded any expedition with which Edgar L. Hewett was connected. He recognized that Hewett, to whom the permit for excavating the new national monument had been issued, had already manipulated the system for his personal benefit. Douglass had serious and legitimate concerns about the intentions of the Cummings party. He had the power to make the expedition change its practices and the inclination to use it. [26]

In perspective, the rivalry between Cummings and Douglass was more a clash of cultural perspectives than a nasty government man taking credit from archeologists and local people. Douglass was a forerunner of the ordered, regulated society that would become codified in the founding of the National Park Service seven years later. He sought strictures on individual activity, no matter who performed archeological work or how respected their credentials. Ironically, like Hewett, Douglass was incapable of following the very rules to which he held others. His later excavations on Chacoma Peak and at Ojo Caliente revealed the same kind of collecting for which he chastised Hewett and Cummings in 1909. [27]

Nor could Douglass legitimately censure Cummings for collecting artifacts. Archeological science was in its infancy, and describing ruins, collecting artifacts for museums, and making wild generalizations about prehistoric life was standard practice. What worried Douglass was the disposition of the artifacts and the condition of the sites after a foray. He recognized that the government needed to protect the structures from which the artifacts came as well the pottery and the baskets of prehistory.

From Rainbow Bridge, the explorers went in different directions. Neil Judd took William B. Douglass and his surveyors to Betatakin and Keet Seel, where they began to map the newly established national monument, while Cummings and John Wetherill explored the canyons south of Navajo Mountain with Dogeye-begay, another guide. Judd left Douglass at Keet Seel with a map of Betatakin and the Bubbling Spring ruins and returned to Oljato to meet up with Cummings.

Douglass' efforts to halt the excavation began to pay off. Waiting for John Wetherill at Oljato was a letter from S. V. Proudfit, the Acting Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Proudfit inquired about unauthorized excavations within the boundaries of the national monument. "There is no one excavating on the Navajo National Monument except Prof. Cummings and party," Wetherill immediately replied, "and they are doing so under the permit issued to Edgar L. Hewett." [28]

For Wetherill, this was an enlightening moment. He was well aware of his brother's problems with the Department of the Interior and he depended on his income as a guide. He was also an enthusiastic explorer, a trait he shared with the rest of his family. When he accepted appointment as the custodian of the monument, he cast his lot with Douglass and the Department of the Interior. No matter how fondly he felt toward Cummings, he knew well the price of thwarting the Department of the Interior. By 1909, his iconoclastic brother had paid it in full.

The scientific establishment in Washington, D. C., also lined up with Douglass. Since the passage of the Antiquities Act in 1906, the federal bureaucracy had jealousy guarded its power to permit excavation. Scientists affiliated with the Smithsonian Institution and the Bureau of American Ethnology saw themselves as the best professionals to initiate surveys of protected ruins. Part of important federal bureaus, they did not need to make collections to assure future support of their work. Douglass' reports spurred the interest of Dr. J. Walter Fewkes and Dr. Walter Hough, two eminent Americanists, and by the end of the summer of 1909, plans had begun for a preliminary expedition the following year. William Henry Holmes, who succeeded Powell as the head of BAE, supported Douglass as the surveyor tried to compel excavatory work to cease. [29] A power struggle had begun.

Cummings was on sabbatical from the University of Utah, and his permit was still valid. In the fall and winter of 1909, he continued to work in the region, returning to Tsegi Canyon and excavating Betatakin. Arriving in a snowstorm, the party looked through the talus material below the ruin for burials and found none, but were more successful in the ruin itself. They found four four-stop reed flutes and a number of turquoise ear pendants set in wood. The party left in haste when Nedi Cloey arrived with horses to take them out before a serious snowstorm, and they left their discoveries stored in one of the rooms of the ruin. The relics were never seen again. [30]

Cummings' foray signaled the end of undocumented excavation in the monument. The following year, the BAE sent Fewkes to make a written record of the treasures of the new monument. Cummings stayed away. Like Hewett, Cummings lacked formal training in archeology. He too recognized that either federal affiliation or further training would be essential to preserve his position in the changing world of science. Between 1905 and 1908, Hewett acquired a Ph.D. from the University of Geneva. After he left Tsegi Canyon, Cummings went to Berlin to study archeology. Only in 1912 did Cummings return to Betatakin. [31] Fewkes replaced him as the primary excavator of Navajo National Monument. Federally sanctioned science had triumphed over its university-based equivalent.

In this respect, an effort to control who had access to federally reserved ruins succeeded. Douglass, Holmes, and Fewkes paved the way for "responsible" rather than individualistic science--people and activities sanctioned by the Smithsonian and the Bureau of American Ethnology that had more than collecting artifacts as their objective. Combined with the revolutionary application of stratigraphy by Nels V. Nelson in the Galisteo Basin later in the decade, archeology began to move away from the romantic approach of Hewett and Cummings toward a more empirical style. Alfred V. Kidder carried the new mode even further in his excavations at Pecos. The field was changing, and the new way of doing archeology limited the significance of the work of people such as Hewett and Cummings. As a result, the struggle over access at Navajo National Monument and many similar instances in the Southwest degenerated into power struggles between people in the region in proximity to the ruins and representatives of federal agencies with the ability to sanction but not to enforce.

Sanctioned scientists became the beneficiaries of the monument proclamation. A structure for the process of excavating federal ruins had been established. After the confused situation at Navajo National Monument, federal officials watched more carefully the permits they issued as BAE scientists sought to make at least preliminary explorations before those interested in making collections got their chance.

The first of two Fewkes expeditions arrived in September 1909. Fewkes had spent the summer at Mesa Verde working at Cliff Palace, but as the tension increased in northeastern Arizona, Holmes needed a first-hand account from a dependable professional. Despite his experience in land matters, Douglass did not have the credibility of someone familiar with archeological excavation. Fewkes was close at hand, and received orders to inspect the monument that had become the source of all the trouble.

It was a brief visit that Fewkes made, although he and his party visited most of the ruins in the area. They traveled to Betatakin and Keet Seel, visited numerous smaller ruins, and made the forty-mile trek to Nitsin Canyon and Inscription House. Yet this was clearly a preliminary trip, for little or no excavation was accomplished and Fewkes spent only a short time in each place.

The following spring, Fewkes returned to the area for further work, permit in hand, made out in his name. After the second visit, Fewkes made comprehensive descriptions of each of the ruins, his view of their place in American prehistory, as well as the approaches to this remote part of northeastern Arizona. These were included in Preliminary Report on a Visit to the Navaho National Monument, Fewkes' account of the trip that was published as Bureau of American Ethnology report #50 in 1911.

Fewkes' report was precisely the kind of document that William B. Douglass thought was essential for the protection of prehistoric ruins in the Southwest. Officials at the Smithsonian Institution and the BAE concurred. Here was a document that chronicled the condition of the site and its attributes, written before wholesale excavation took place. Despite its overly descriptive nature, it was a practice federal officials sought to encourage. [32]

At the close of his report, Fewkes proposed a plan for the monument. He suggested the excavation, restoration, and preservation of either Keet Seel or Betatakin as a "type ruin," presumably for visitors and scientists. The selection seemed ideal. Both Keet Seel and Betatakin were spectacular places with much appeal to anyone who saw them. They inspired a romantic vision of prehistory that meshed with the dominant tone of the time period.

The boundaries of the monument also needed adjustment, for in his haste to prevent unauthorized excavation, Douglass had actually facilitated the establishment of a 160-square-mile monument. Fewkes recommended the addition of Inscription House to the monument. It had been left out of the original proclamation, for whites did not find it until after the monument was established. By coincidence, Betatakin, also not yet discovered, had been included in the original proclamation.

Fewkes' trip and subsequent report brought many more visitors to the region, most of whom hired John Wetherill as a guide. In the fall of 1909, the Wetherills and Clyde Colville moved their trading post south to Kayenta, Arizona, much closer to the ruins of the Tsegi area. Dr. T. Mitchell Prudden, a physician with an intense interest in archeology and an important list of publications in the field, visited the monument with Wetherill in 1910. Herbert E. Gregory of Yale University, a geologist who assisted the U.S. Geological Survey during the summers and was reputed to be able to outwalk a horse in desert sand, attempted to map the region in 1910. Gregory reported that besides the ruins of the Tsegi, there were additional ruins of interest in the vicinity of Navajo Mountain. But Department of the Interior officials decided that the existing monument was sufficient. [33]

The increase in activity in the area contributed to the adjustment of the boundaries of the monument. With the surveying of the 160 square miles, even the most ardent advocates of preservation recognized that too much land had been reserved if the purpose of the monument was to protect archeological areas. William B. Douglass was the first to recognize this reality, and the work of Herbert Gregory confirmed Douglass' observations.

Other pressures came to bear on the Department of the Interior and the General Land Office. Although the land in the region was marginal at best, livestock interests in Arizona sought to lease portions of the monument for grazing and prospecting. One particularly persistent attorney, Clarence H. Jordan of Holbrook, Arizona, made the case for his client, Kenneth M. Jackson. Jordan and Jackson were aware that the monument existed to preserve prehistory, for they promised that the cattle enterprise would not damage the ruins. They also suggested that livestock grazing and preservation were compatible. But after an exchange between Secretary of the Interior Walter L. Fisher and his subordinates, Jordan's proposal was turned back. [34]

The pressure for the grazing permit was an issue that the Department of the Interior wanted to avoid. National monuments were new, and federal officials did not want animosity towards the idea. They were also aware Navajo National Monument was far too large. With some inside maneuvering, General Land Office officials put together a measure for the President's signature that added Inscription House to the monument, but reduced the total area of the monument to two 160-acre sections surrounding Betatakin and Keet Seel and a 40-acre tract around Inscription House. On March 14, 1912, President William H. Taft signed the document. The reduced size of the monument eliminated grazing, the Jordan-Jackson proposals, and most of the potential for antagonizing local constituencies. [35]

The Navajo National Monument that resulted was as much a product of the times in which it was established as of a desire for preservation. Fear of depredation inspired the original proclamation, but no one from the government had yet seen the ruins. Competition between different groups within the scientific community played a significant role in shaping the original boundaries. Establishment of the monument ostensibly eliminated the threat of untrained, unaffiliated "pot-hunters." A rivalry among scientists representing different kinds of archeology ensued.

When it was finally pared down to a more reasonable size for its purpose, the monument was awkward and gerrymandered. Visitation had no place in the thinking of the people who redrew the boundaries of the monument. They sought to preserve ruins, apparently assuming that the remote nature of the monument would protect it forever. As a result, three non-contiguous areas did not seem unwieldy. But the 1912 revision attempted to fuse three discrete and unconnected entities with forty miles between them and histories and patterns of their own into one unit. Subsequent management would always be difficult.

Navajo was the classic remote monument. There was no easy way to get there, nor did it fit in any of the schemes for tourism that appeared during the first two decades of the twentieth century. As a remote place, it could not command the resources of federal administrators. No visitors accidentally discovered it and returned with their friends. It had no advocates or constituents save archeologists, no one who could argue that it merited the attention of the federal bureaucracy. As a result, it remained outside of the mainstream of General Land Office and later National Park Service policy and direction. A pattern of exclusion that haunted the monument until the 1960s existed at its founding.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

nava/adhi/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006