|

New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park Massachusetts |

|

NPS photo | |

"The town itself is perhaps the dearest place to live in, in all New England. All these brave houses and flowery gardens came from the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans. One and all, they were harpooned and dragged up hither from the bottom of the sea."

—Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

Whaling Capital of the World

In January 1841, a 21-year-old seaman named Herman Melville set sail aboard a whaling ship on one of the most important sea voyages in American literature, the book inspired by that voyage was the world-famous Moby-Dick, and the place Melville sailed from on that cold winter day was New Bedford, Massachusetts.

It is not surprising that Melville chose to embark from New Bedford—it was the whaling capital of the world. Its waterfront teemed with sailors and tradespeople drawn from all over the globe by the whaling industry's promise of prosperity, and its wide residential streets sparkled with the mansions of the wealthy whaling families.

The whaling industry that flourished in Melville's New Bedford had been born many years before and continued growing for another decade and a half. In the 1850s more whaling voyages sailed from New Bedford than from all of the world's ports combined.

Today, New Bedford is a city of nearly 100,000, but its historic districts still retain embellishments that Herman Melville admired. Walk its cobblestone-lined streets by stately buildings, banks, and storehouses from the days when New Bedford was the whaling capital of the world. Tour historic structures, gardens, and museums and visit the working waterfront, homeport to one of America's leading fishing and scalloping fleets. The streets, buildings, and harbor preserve the stories of early settlers, whaling merchants, maritime workers, and the many people for whom New Bedford was both port of entry and of opportunity.

Preserving the city's legacy did not come easily. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, when buildings were being torn down to make way for urban renewal projects, determined citizens worked together to save the city's history and neighborhoods. Innovative preservation efforts focused on the waterfront, the city's heart and soul.

Park Partners

The National Park Service joined this partnership in 1996 when Congress created New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park to help preserve and interpret America's whaling and maritime history. The park consists of the 13-block Waterfront Historic District but is unlike most national parks in that individuals and groups continue to own and operate their properties. The role of the National Park Service is to work collaboratively with a wide range of local partners, including the City of New Bedford, New Bedford Whaling Museum, schooner Ernestina, Rotch-Jones-Duff House and Garden Museum, New Bedford Port Society, New Bedford Historical Society, and Waterfront Historic Area League (WHALE). The National Park Service also works in partnership with the Iñupiat Heritage Center in Barrow, Alaska, to help recognize the contributions of Alaska Natives to the history of whaling in the United States. From the South Seas to the Arctic, from South America to Hudson's Bay, the story of New Bedford whaling is a blend of many cultural influences.

Cultural Effects

Scrimshaw

On voyages that might last as long as four years, whalemen spent their leisure

hours carving and scratching decorations on sperm whale teeth, whalebone, and

baleen. This folk art, known as scrimshaw, often depicted whaling adventures or

scenes of home. The whalemen also made eating utensils, mortars and pestles,

salt and pepper shakers, pie crimpers, and other objects out of ivory and

baleen. Commercially, baleen was used in making corset stays, skirt hoops, and

buggy whips.

Pursuing Whales Worldwide

Beginning in the 18th century the whaling industry used small sailing ships to

chase whales along the eastern coastline. Then, as the number of Atlantic whales

dwindled and competition for whale oil increased, square riggers traveled for

years at a time world-wide, wherever whales gathered. Americans had plied every

ocean from the South Seas to the Western Arctic by the 1850s and found most of

the grounds of sperm, right, bowhead, humpback, and California gray whales. Both

finback and blue whales were too much for the 30-foot whaleboats and hand-held

harpoons of the time.

Port of Entry

The whaling industry employed large numbers of African-Americans, Azoreans, and

Cape Verdeans, whose communities still flourish in New Bedford today. New

Bedford's role in 19th-century American history was not limited to whaling,

however. It was also a major station on the Underground Railroad moving slaves

from the South up North and to Canada. Among these fugitives was Frederick

Douglass, who lived and worked in the city for three years and was to become a

leading anti-slavery orator and author.

Lighting the World

Starting in the Colonial era, Americans pursued whales primarily for blubber to fuel lamps. Whale blubber was rendered into oil at high temperatures aboard ship—a process whalemen called "trying out." Sperm whales were prized for their higher-grade spermaceti oil, used to make the finest smokeless, odorless candles. Whale-oil was also processed into fine industrial lubricating oils. Whale-oil from New Bedford ships lit much of the world from the 1830s until petroleum alternatives like kerosene and gas replaced it in the 1860s.

Visiting the Park

One of the pleasures of visiting New Bedford is to walk its streets and look at its buildings. Most sites described here are within the national historical park. Some are open to the public year-round; others are open seasonally. Most are managed by nonprofit organizations that charge an admission fee. Stop first at the park visitor center to get oriented.

Park Guide

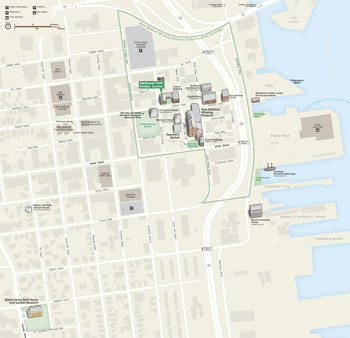

(click for larger map) |

Park Visitor Center, at 33 William Street, offers information about sites, facilities, and community activities. This Greek Revival structure built in 1853 served as a bank, courthouse, auto parts store, antique mart, and a bank again before it became the national historical park visitor center. Park rangers and volunteers are on hand to answer your questions.

Seamen's Bethel, across from the Whaling Museum, has served mariners since 1832 as a house of worship. Before he shipped out on the whaler Acushnet in 1841, Herman Melville attended services there. Ten years later, in Moby-Dick, he wrote about the chapel's marble memorials to seamen lost at sea. A pulpit in the shape of a ship's bow based on Melville's imaginary description was installed in 1959.

The oldest continuously operating U.S. Custom House still stands at the corner of William and North Second streets. Here seafarers from around the world register their papers, captains pay duties and tariffs, and other transactions take place. This 1836 building features a granite façade and four Doric columns. It was designed by Robert Mills, architect of the Washington Monument.

Bricks from a demolished textile mill were used to build the Wharfinger Building as a Works Progress Administration project in 1934. For many years scallop and fish auctions were held here each morning. Now the building serves as the city's waterfront visitor center and houses an exhibit on the working waterfront.

Clocks and chronometers were made in the Sundial Building, but this 1820 brick-and-stone structure is named for the vertical sundial on its Union Street exterior. Seamen were known to set their instruments by the dial's time, known as "New Bedford time." Check its accuracy. The building was restored after a devastating gas explosion and fire in 1977. Now owned by the New Bedford Whaling Museum, the building houses its administrative offices.

New Bedford Whaling Museum, 18 Johnny Cake Hill, holds the world's largest and most outstanding American whaling and maritime history collections. Highlights include the Lagoda, an 89-foot, half-scale replica of a square-rigged whaling bark, and rare whale skeletons. The museum has extensive collections of whaling implements, scrimshaw, photographs, logbooks, and paintings of the region and whaling industry by major American artists like Albert Bierstadt and William Bradford. Also on display are decorative art objects and art glass made in New Bedford. Fee.

Rotch-Jones-Duff House and Garden Museum, a Greek Revival mansion at 396 County Street, was built in 1834 for whaling merchant William Rotch, Jr. Furnished period rooms and collections chronicle the city's history through the three families who lived here over a span of 150 years. Set on a city block of urban gardens, the property includes a historic wooden pergola, formal boxwood rose parterre garden, and wildflower walk. Fee.

Mariners' Home, 15 Johnny Cake Hill, was built in 1787 as the mansion of William Rotch, Jr. It has offered lodging to visiting mariners for more than 100 years. It was donated to the New Bedford Port Society in 1851. Not open to the public.

Rodman Candleworks, Water Street, produced some of the first spermaceti candles, known for being dripless, smokeless, and long-lasting. The structure was built in 1810 of granite rubble covered with stucco and then scored to look like blocks of granite. The candleworks closed in 1890. The building was used for various purposes before being rehabilitated. Commercial establishment.

As its name implies, the Double Bank Building once housed two banks on Water Street, the "Wall Street of New Bedford."

From the Bourne Counting House, Jonathan Bourne, Jr. could look out at his whaleships in the harbor and keep records of his outfitting costs, the number of whale-oil barrels the ships brought back, wages paid, and other transactions. This building later housed the Durant Sail Loft, which made its last set of sails for New Bedford whaler Charles W. Morgan, now docked at Mystic Seaport Museum. Commercial establishment.

The schooner Ernestina has had a multifaceted career since it was launched as the Effie Morrissey in Essex, Mass., in 1894. Originally a Grand Banks fishing vessel, it has served as an Arctic explorer, World War II supply ship, and trans-Atlantic packet carrying Cape Verdean immigrants to the United States. Now it sails with an educational mission. The schooner was given to the people of the United States by the people of the Republic of Cape Verde in 1982. When in port this national historic landmark and official vessel of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts can be viewed from Coast Guard Park, just south of State Pier.

Source: NPS Brochure (2005)

|

Establishment New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park — November 12, 1996 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

"A Compact With the Whales": New Bedford, the American Civil War, and a Changing Industry (Mark Ryan Mello, Master's Thesis Providence College, Spring 2020)

A Generous Sea: Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and the Jewish Community in New Bedford Whaling & Whaling Heritage Special Ethnographic Report (Marla R. Miller and Laura A. Miller, 2016)

Behind the Mansions: The Political, Economic, and Social Life of a New Bedford Neighborhood (Kathryn Grover, May 2006)

Coastal Hazards & Sea-Level Rise Asset Vulnerability Assessment for New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park and Roger Williams National Memorial NPS 962/154049 (B. Tormey, K. Peek, H. Thompson, R. Young, S. Norton, J. McNamee and R. Scavo, April 2019)

Cultural Landscape Report and Geophysical Survey: Rotch-Jones-Duff House & Garden Museum, New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park, New Bedford, Massachusetts (DHM Design, Pressley Associates, Hager GeoScience and Bryant Associates, September 2010)

Cultural Landscape Report for The Rotch-Jones-Duff House & Garden Museum: Volume II: Treatment, New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park (Christopher M. Beagan and H. Eliot Foulds, 2012)

Foundation Document, New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park, Massachusetts (June 2018)

Foundation Document Overview, New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park, Massachusetts (June 2018)

Fugitive Slave Traffic and the Maritime World of New Bedford (Kathryn Gover, January 24, 1967 and January 30, 1975)

Hetty Green "the Witch of Wall Street" (undated)

Historic Strutures Report: Rodman Candleworks, Double Bank Building, United States Custom House, New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park, New Bedford, Massachusetts (Lauren H. Laham, 2009, published 2011)

Imprint of the Past: Ecological History of New Bedford Harbor (Carol E. Pesch, Richard A. Voyer, James S. Latimer, Jane Copeland, George Morrison and Douglas McGovern, February 2011)

Junior Ranger Activity Booklet, New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park (2008; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Activity Booklet, New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Ernestina (James P. Delgado, April 18, 1990)

New Bedford Historic District (S.S. Bradford and Polly M. Rettig, January 8, 1988)

Newsletter: Winter 2003 • Spring 2008 • Summer 2008 • Spring 2009

Park Programs and Events: 2007 • 2008 • 2009 • 2011

Productivity in American Whaling: The New Bedford Fleet in the Nineteenth Century National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 2477 (December 1987)

Safely Moored At Last: Cultural Landscape Report For New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park — Volume I: History, Existing Conditions, Analysis, Preliminary Preservation Issues Cultural Landscape Publication 16 (Christine A. Arato and Patrick L. Eleey, 1998)

Special Resource Study for New Bedford, Massachusetts (undated)

The First Decade: A Retrospective 1996-2006 (c2007)

nebe/index.htm

Last Updated: 09-Apr-2025