|

NEZ PERCE

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER THREE:

LAND ACQUISITION AND PROTECTION

Introduction

The conceptual plan for Nez Perce National Historical Park called for the protection of a number of scattered sites, a so-called "string of pearls," most of which would not require National Park Service ownership. The original planning group for the park recommended that the NPS acquire fee title for just three key sites at Spalding, East Kamiah, and White Bird Battlefield. [146] (Canoe Camp, a fourth NPS-owned area, was donated to the NPS by the State of Idaho in July 1966.) To ensure that the Park Service would abide by this plan (and to satisfy Idahoans who might otherwise oppose the creation of the park) Public Law 89-19 limited the purchase of land in fee to 1,500 acres and the purchase of scenic easements for an additional 1,500 acres. The total cost for these lands could not exceed $1,337,000 under the law. Other federal agencies could transfer ownership to the Park Service of another 1,500 acres. Whatever lands the Nez Perce Tribe donated to the park would not count against any of these limitations. Land acquisition would be funded by the newly created Land and Water Conservation Fund. [147]

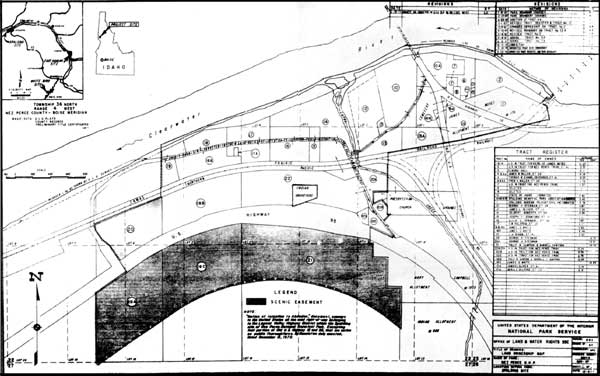

Most of the park's original land base (that is, excluding the park additions authorized in 1994) was acquired between 1966 and 1969 ( Figure 2). This chapter first summarizes the land acquisition program for the Spalding, East Kamiah, and White Bird Battlefield units. It then considers land protection issues associated with the cooperative sites. Finally, it traces the park's involvement with two national historic trails. Discussion of the park additions after 1994 is reserved for Chapter 8.

Land Acquisition for the Spalding Site

Land acquisition officially began with the transfer of Spalding State Park to the Park Service in a public ceremony on July 24, 1966. This area, with its shady arboretum and picnic grounds, its memorial to Henry and Eliza Spalding, and its pleasant stretch of riverfront, formed the nucleus of the Spalding site. It adjoins a cemetery and church used by Nez Perce tribal members.

After acquiring Spalding State Park, the Park Service still had an inadequate land base for protection of historic resources at Spalding. If the long-range goal was to restore the scene to its historical character, several dwellings of twentieth-century origin would have to be removed. Indeed more than a dozen houses and outbuildings extending along the county road from the Spalding post office west as far as the present-day maintenance building would have to be acquired and torn down. Thus, the most complicated, costly, and politically sensitive element of the whole land acquisition program involved the remaining lands that were to constitute the Spalding site.

Interior Department officials actually became involved in land acquisition at Spalding more than two years earlier, indeed before Congress enacted P.L. 89-19, by giving encouragement to a tribal proposal to acquire property in Spalding for later sale to the Park Service. The purpose of this informal arrangement was to prevent certain land owners from raising the price for their land once the park was authorized. In 1964, the tribe negotiated three land purchases in Spalding of the Watson, Evans, and Sampson brothers properties for a total investment of $53,299. In 1967, the Park Service agreed to purchase these tracts from the tribe for $66,000, allowing for seven percent per annum interest on the tribe's investment plus ten percent overhead and administrative costs. [148]

At the same time that the Park Service negotiated a land sale with the tribe, it made preliminary inquiries among local residents. While the Park Service was able to find a handful of willing sellers, other residents protested vehemently to Senator Frank Church. The senator, always wary of backlash from his constituents for his stances on environmental issues, suggested to NPS Director George Hartzog, Jr., that the Park Service might be trying to include more land in the Spalding site than Congress had intended. [149] Church recommended that the negotiations between the Park Service and land owners should be handled locally by the superintendent. This prompted a visit to Spalding by Hartzog in May 1967. After Hartzog's visit, Burns discussed the problem directly with Church and reported to the director, "I came away with the distinct feeling that the Senator will be satisfied with anything we do there — even though he did not come out and say it." [150]

|

| Figure 2. Land Ownership at Nez Perce National Historical Park (NPS map.) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The Park Service determined to negotiate an acquisition package for the remaining landowners rather than purchase the tracts individually. Superintendent Burns, accompanying Inspector Clifford J. Harriman of the Park Service's central office in Washington, negotiated purchasing options with nine property owners as follows:

| Tract No. | Owner | Appraisal | Purchase Price# |

|---|---|---|---|

| #Purchase price includes sellers' moving and relocation expenses. Since 1983, the NPS has not had authority to pay more than the appraised value for real property. | |||

| 4 & 4A | James Miller | $8,500 | $14,950 |

| 6 & 6A | Fred Miller | 9,000 | 13,000 |

| 13 | James Oliver | 9,500 | 11,750 |

| 13A | Oliver Albright | 20,000 | 34,500 |

| 15 | Joe Crawford | 6,500 | 7,500 |

| 16 | Alvin Sprague | 9,600 | 11,200 |

| 17 | Chub Ralstin | 19,000 | 27,550 |

| 18A, B, & C | Jim White | 38,000 | 42,900 |

| 12-20 & 20A | George Stedman | 24,223 | 30,000 |

| TOTALS | 144,323 | $193,350 | |

There were four other landowners who had already settled with the Park Service:

| Tract No. | Owner | Appraisal | Purchase Price# |

|---|---|---|---|

| # Purchase price includes sellers' moving and relocation expenses. Since 1983, the NPS has not had authority to pay more than the appraised value for real property. | |||

| 3 | Elnora Hall | $4,000 | $5,000 |

| 17A | Gerald Wilfong | 8,750 | 9,900 |

| 21 | Tully Sampson | 20,280 | 22,500 |

| 2,22,22A, B, C | Nez Perce Tribe | 42,750 | 66,000 |

| TOTALS | 75,780 | 103,400 | |

and three landowners who had made offers:

| Tract No. | Owner | Appraisal | Purchase Price# |

|---|---|---|---|

| # Purchase price includes sellers' moving and relocation expenses. Since 1983, the NPS has not had authority to pay more than the appraised value for real property. | |||

| 5 | Thomas Evans | 3,000 | 6,000 |

| 14, 14A, 14B | Del Roberts | 24,000 | 30,000 |

| 19 | J.H. Dixon | 11,500 | 15,000 |

| TOTALS | 38,500 | 51,000 | |

In addition, the NPS prepared to bring condemnation proceedings against two other land owners for Tracts 1, 1A, and 22D unless they joined in the overall settlement. This brought the total cost of land acquisition for the Spalding unit to $358,750. The total was higher than anticipated, but Harrison recommended that the Park Service accept the package because many of the property owners were elderly and were experiencing difficulty relocating and had already inspired local sympathy. The negotiations, Harrison further explained, had been long and difficult and the alternative of bringing condemnation proceedings would be costly. Assistant Director Ed Hummel authorized the chief of the Office of Land and Water Rights, Thomas Kornelis, to accept the options on all tracts in the Spalding area. [151]

By December 1968, the land acquisition program for the Spalding site was nearly complete. Three significant land issues remained which would present some difficulties for years to come. These were the Camas Prairie Railroad right-of-way, the Lapwai Mission Cemetery, and the Spalding viaduct. The Camas Prairie Railroad went right through the Spalding site, with the former state park being situated on one side and the old Presbyterian church on the other. Freight trains ran fairly regularly along this railroad; today they run daily, mostly carrying logs. The trains posed a safety hazard as well as a problem of aesthetics. A Lewiston-based group now and then raised the possibility of operating steam-powered excursion trains between Lewiston and the historical park, a prospect that the Park Service viewed with disfavor. Instead, the Park Service planned to seek a scenic easement over this railroad right-of-way to prevent commercial development. The plan, however, was never carried out. [152]

The Lapwai Mission Cemetery had historic value. It contained the grave stones of Henry and Eliza Spalding and many mission Nez Perce parishioners. It abutted the arboretum in the former Spalding State Park. The Nez Perce Tribe owned the cemetery and still used it, while the Board of Trustees of the Spalding Presbyterian Church managed it. Prior to 1966, the state of Idaho had a verbal agreement with the Board of Trustees to maintain the cemetery along with the state park. After the transfer of the state park to the Park Service, Superintendent Burns provided for the cost of maintenance (mainly mowing and watering) from the park's budget. In 1971, Superintendent Williams formalized this arrangement in a memorandum of agreement between the NPS and the tribe. Thus, all land protection issues involving the cemetery — gating the road at night, discouraging inappropriate recreational use of the cemetery grounds, improving the sprinkler system — required cooperation between the park administration and the Board of Trustees of the Spalding Presbyterian Church. [153]

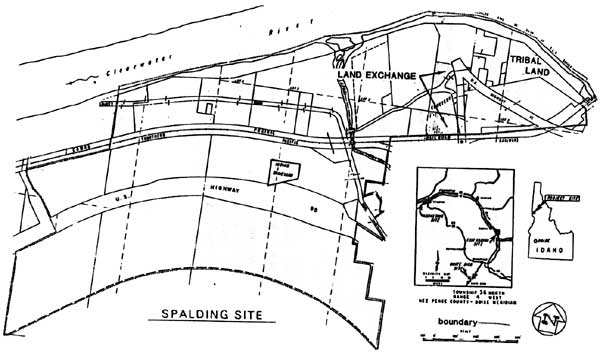

In 1979, Superintendent Morris proposed a land exchange with the tribe that would allow for expansion of the cemetery to the south and consolidate the park's holdings north of it ( Figure 3). At that time the former Blue Lantern Motel, which extended onto the Park Service's 1.27-acre parcel, was still in use as park administrative headquarters. Under Superintendent Morris' proposal the former Blue Lantern would be vacated and the building razed prior to the land exchange. NPTEC approved the plan but the church's Board of Trustees claimed that the tribal land involved in the exchange actually belonged to the Spalding Presbyterian Church. This delayed the land exchange for several years until the tribe was able to obtain clear title to that tract. The transfer was finally accomplished in 1991. [154]

|

| Figure 3. Historical Map of Land Exchange, Spalding, 1991. (National Park Service map, no date.) |

The third unresolved land issue in Spalding involved the Spalding viaduct, or more broadly, the evolving commercial highway pattern in the area. As proponents of Nez Perce National Historical Park had emphasized all along, two interstate highways converged at Spalding, making that place a natural "gateway" for orienting tourists to Nez Perce country. Yet the highway junction also threatened to overwhelm Spalding's historical character.

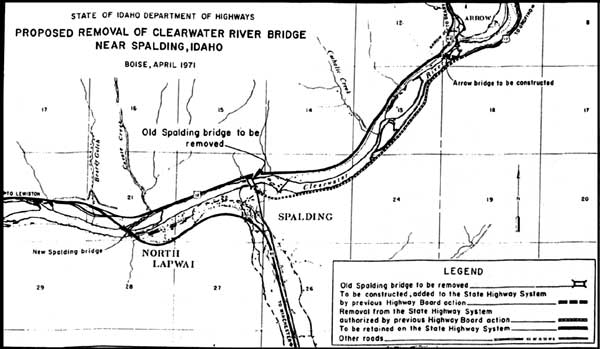

The highway traffic pattern around Spalding went through three major changes, each involving the construction or abandonment of a different bridge (Figure 4). When the park was first proposed, all traffic through the area used the Old Spalding Bridge across the Clearwater River. Dating from the 1920s, this highway bridge joined the south bank of the river less than one hundred yards from the historic mission site. The first change in this highway traffic pattern occurred with the completion of the New Spalding Bridge one and a half miles west of Spalding. Traffic between U.S. 95 and Lewiston now bypassed Spalding, whisking past the village on a broad 55 m.p.h. curve that rounded the hillside between Lapwai Creek and the Clearwater River. The new bridge opened shortly before Nez Perce National Historical Park was authorized.

|

| Figure 4. Historical Map of Highway System at Spalding, 1971. (State of Idaho Department of Highways Map.) |

The second change came in the 1970s with the completion of the Arrow Bridge, a little more than two miles east of Spalding, and the removal of the Old Spalding Bridge. Now all traffic on U.S. 12 bypassed Spalding on the opposite side of the Clearwater River. Even if traffic now moved past the site at greater speeds, these changes were probably good from the standpoint of protecting the historic resources and improving the park setting. But some traffic between U.S. 95 and points east still went through the site, because savvy motorists knew that they could shave about three miles off their trip by taking the old U.S. 12 from Spalding along the south side of the Clearwater River to Arrow Junction.

The third change in the highway traffic pattern came with the closure of the Spalding viaduct in 1986 when the state highway department declared it unsafe. The closure deflected all traffic that was using old U.S. 12 onto the short section of road past the picnic area. Superintendent Weaver was faced with the unacceptable situation of having semi-trucks and numerous other vehicles driving directly through the Spalding unit. Not only did it harm the park's ambiance, but the road itself was crumbling under this unprecedented usage. After considerable local public debate on the situation, Weaver decided to close the park road to through traffic in 1988. Signs were posted at Arrow Junction to warn motorists that old U.S. 12 now ended at the Spalding viaduct. Frustrated motorists who missed the signs kept breaking down the Park Service's barrier when they got to Spalding. Finally Weaver put up a heavy pipe gate. Frustration with the road closure gradually abated, leaving the highway traffic pattern around Spalding more favorable than it had been in seventy years from the standpoint of the historic resources and providing a parklike ambiance. The old, abandoned viaduct still stands, and continues to be a major visual intrusion on the historic scene. [155]

Land Acquisition for the East Kamiah Site

Original plans for Nez Perce National Historical Park contemplated that three historic themes would be represented near the town of Kamiah: Nez Perce culture, the Lewis and Clark story, and the missionary story. An important element of Nez Perce culture, the tribal legend of how the people came to inhabit the Nez Perce country, would be presented at the site of a geologic formation known to the Nez Perce as the Heart of the Monster. A piece of the Lewis and Clark story would be told nearby with a roadside sign. This was the area of the "Long Camp," where the Lewis and Clark expedition waited for snow in the Bitterroot Mountains to melt before returning eastward over the range. The actual site of the Long Camp was now occupied by an operating sawmill so there would be no land acquisition involved in this site. Finally, the missionary story here would feature the First Presbyterian Church, built in 1874, and the McBeth house nearby, where the missionaries Susan and Kate McBeth resided. The McBeth sisters are buried in a cemetery behind the church. [156]

By 1970 the Park Service had tailored this interpretive scheme to fit the realities of the park's land base in East Kamiah; it was decided to drop the missionary story in East Kamiah after the First Presbyterian Church refused to sell its land to the Park Service. Significantly, this change of plan preceded the decision to scale back the basic development plan for the park. According to the new development plan, the Park Service would forgo the development of three "entrances" into Nez Perce country at Spalding, East Kamiah, and White Bird in favor of a main hub at Spalding.

Various explanations were given for the First Presbyterian Church's refusal to sell. Burns thought the Presbyterian Nez Perces of Kamiah were acting out of spite toward the Nez Perces of Lapwai. [157] In the 1960s these devoutly Christian Nez Perces still looked askance at the way the Nez Perces in Lapwai were bringing back the root feast, holding pow-wows, and reviving other tribal customs that the church had discouraged earlier in the century. [158] Conversely, the Reverend Henry L. Sugden suggested that the church membership became intransigent on the sale of the church property (which included a number of rental homes) only after a Park Service appraiser rudely appeared unannounced and "thoroughly examined and measured all homes inside and out." [159] In the course of Burns' subsequent talks with the church congregation, some Nez Perces raised a significant point, as Burns reported:

One item they mentioned, which I think we should give careful consideration to, is the fact that for the past 100 years or so it has been the tradition of this Church that individual Indians were allowed to build close around them. I feel that this tradition should be maintained, since we are not trying to present the picture that close back into the old culture or the days of Lewis and Clark. Their point is well taken. They feel we should not buy their lands and then ignore their tradition in order to tailor the story to our ideas. [160]

At Superintendent Burns' suggestion, the Park Service retreated from its original plan to acquire this site. Later, Superintendent Williams proposed an alternative in which the Park Service would buy the McBeth house and move it to the East Kamiah site. This plan never materialized. [161]

The Park Service acquired some privately-owned lands around the Heart of the Monster site. Once the lands were in Park Service ownership, the park administration removed a sawmill and junkyard to clean up the area. In addition, the Park Service dissuaded NPTEC from undertaking a variety of proposed developments on tribal lands nearby that would have adversely affected the site. Examples included a tribal housing project and a rodeo grounds. [162] The NPS tried to acquire a parcel on the opposite side of the highway from the Heart of the Monster but was unsuccessful. This land was subsequently developed into a commercial campground for recreational vehicles. [163]

Land Acquisition for the White Bird Battlefield

The site of the Battle of White Bird Hill contrasted with the Spalding and East Kamiah sites. The area had no habitations or other roadside development, but local ranchers grazed livestock. As the park's master plan indicated, "The site itself is attractive and its restoration to its historical condition would be a relatively minor undertaking." The authors recommended that the Park Service acquire about 1,250 acres in fee and an additional 725 acres in scenic easement. [164] In October 1969 the NPS acquired fee title to 1111.6 acres and an easement over 285 acres. The NPS purchased the land and easement from Harry M. Hagen of White Bird for $71,000. The NPS purchased a scenic easement over an additional 100 acres belonging to local rancher Charles Bentz. These lands formed the core of the White Bird unit. [165]

Within the White Bird Battlefield three tracts owned by the state of Idaho remained. These public school land tracts totaled 261.7 acres. As noted earlier, the law would not allow the NPS to purchase this type of land with Land and Water Conservation Funds. The NPS explored various alternatives for protecting these parcels. NPS officials asked the state of Idaho to donate a scenic easement on the three tracts, but state officials responded that the state was legally prohibited from donating fee title or any interest attached to public school lands. NPS officials then considered a proposal to have a local rancher purchase the state-owned tracts and then sell a scenic easement on the lands to the Park Service. The third and preferred alternative was to get the National Park Foundation to purchase the lands and donate a scenic easement to the park. It should be remembered that in no circumstances could the Park Service purchase the lands because the acquisition would cause the park to exceed its maximum allotment of 1,500 acres in fee. [166] To date, the lands remain under state ownership.

NPS management tried to discover what kind of legal force was contained in a scenic easement. In November 1971, Superintendent Williams requested a solicitor's opinion on this issue. Specifically, he wanted to know if hunting was allowed on scenic easements or inholdings within the park boundaries, whether overgrazing was permissible on the state-owned inholdings at White Bird, and whether it was the stockowner's or the landowner's responsibility to prevent grazing trespass on scenic easements. Williams made repeated inquiries over the next two years but did not get a reply to these questions. [167]

The superintendent had to make practical decisions as issues arose. In June 1971, Superintendent Williams authorized the rancher, Harry M. Hagen, to harvest the native grass hay from a 20-acre area inside the park boundary. The cutting of the hay that year, Williams was careful to explain, constituted the removal of a potential fire hazard. [168] On another occasion in 1974, Williams instructed Hagen to remove 100 head of sheep and three horses from NPS lands. [169] (Later, grazing would become the most controversial issue at White Bird, and is discussed in Chapter 7.) Years later, in 1991, Superintendent Walker sought restitution from White Bird resident Andrew Dahlquist for cutting trees on a portion of his property on which the federal government had purchased a scenic easement. Dahlquist's action was in clear violation of the easement, although he professed that he was not aware of the restriction against cutting trees. [170] This incident highlighted another problem with scenic easements: even when the easement was clear on its face, the precise terms of the easement could be forgotten over the course of time. Scenic easements required constant vigilance by the Park Service.

Land Protection and the Cooperative Sites

The park's cooperative sites are those that are managed under cooperative agreement between the Park Service and a landowner. When Secretary of the Interior Walter Hickel formally designated Nez Perce National Historical Park in 1970, he recognized 19 cooperative sites in addition to the Spalding, East Kamiah, White Bird, and Canoe Camp sites. Two more, the Lenore and Pierce Courthouse sites, were included in 1977. With the park additions in 1992, more than a dozen other cooperative sites were authorized. Each individual cooperative site received relatively little attention from the park administration, but collectively the cooperative sites are what make Nez Perce National Historical Park such an unusual unit of the national park system. Arguably, it is the cooperative sites that have shaped the park's management tone. As Superintendent Walker observed in 1991,

This park is based on its ability to get along well with a wide variety of communities, individual landowners, state and other federal agencies. If we are to survive, we must get along fairly well, but if we are to flourish, we must become good neighbors and friends and become involved in community activities and earn the respect and trust of those neighbors and friends. [171]

Management of the cooperative sites began with the task of identifying the landowners and establishing relations with them. The next step was to develop cooperative agreements with the landowners aimed at protecting the resources and providing for public access. The ultimate goal was to develop interpretive exhibits at each site that would make the park a unified whole. All of this had to be achieved in the absence of defined site boundaries.

The initial process of identifying land owners contained at least one surprise: Superintendent Burns learned in 1967 that the Clearwater National Forest did not own the Musselshell Meadows, but had been trying to acquire it through a land exchange with the Diamond National Match Company for the past four years. Forest Service officials agreed with Burns that the site had significance as a major camas digging area, perhaps the last of its kind. [172] The Forest Service acquired the site in 1972 and retained ownership of it. [173]

Other landowners included the Idaho Department of Highways for a large number of sites mostly consisting of roadside interpretive signs, the Keuterville Highway District of Idaho County for the Weis Rockshelter, the Lapwai School District for the Northern Idaho Agency and Fort Lapwai sites, the Forest Service for the Lolo Pass and Lolo Trail sites, Mr. and Mrs. John M. Pfeifer of Culdesac, Idaho, for the St. Joseph's Mission Church, Mr. and Mrs. Leonard Cardiff of Pierce, Idaho for the Pierce Courthouse, and the First Presbyterian Church of Kamiah for both the historic church and the nearby McBeth house. [174]

Private landowners represented the most challenging situations for cooperative management. As noted above, Superintendents Burns and Williams recommended that the First Presbyterian Church and McBeth house be dropped from consideration after they sensed that the park administration would not be able to obtain landowner cooperation. In July 1968, Burns suggested that the St. Joseph's Mission Church be dropped as a site for the same reason. Perhaps NPS officials would have followed his advice if it had not been for the fact that the park brochure had already been published and listed the Pfeifers' church building as part of the St. Joseph's Mission site. The Pfeifers claimed that the brochure had led to an increase in visitation. The Pfeifers demanded some kind of cooperative agreement with the Park Service. [175]

The Pfeifers wanted financial assistance for the maintenance of the building and some modest compensation for their time in guiding visitors through the church. During the winter of 1968-69, Superintendent Williams negotiated a cooperative agreement with the Pfeifers covering these points. In addition, Williams notified the Pfeifers that the NPS would be affixing 18,000 stickers to the 18,000 park brochures it had printed explaining that the church was private property. [176] The final agreement, concluded on June 29, 1970, involved the Park Service and the newly formed St. Joseph's Mission Historical Society, of which the Pfeifers were controlling members. [177]

The Pierce Courthouse presented another problem. The owners wanted to donate the property to the Park Service. Superintendent Williams discussed this possibility with regional officials, who rejected the idea on the grounds that the Park Service should not acquire more historic buildings in the park than it could maintain. The feasibility study of 1963 recommended that the state of Idaho acquire and administer this site; however, state officials proposed to move the building to the capitol lawn in Boise, an idea which the owners and other local citizens adamantly opposed. In 1969, Superintendent Williams proposed that the owner donate the property to the Clearwater Historical Society of Orofino, Idaho, as an "interim measure and until such time as the National Park Service might possibly become involved." Apparently Williams formed the impression that the owner, Leonard Cardiff, had agreed to this arrangement and that the building had changed hands, but two years later he learned that local citizens had dissuaded Cardiff. [178] Finally, the Idaho State Historical Society accepted the offer of donation from Cardiff, and the Park Service entered a cooperative agreement with the Idaho State Historical Society in 1979. In that agreement the NPS agreed to provide guidance on how to preserve and interpret the structure. The NPS would provide actual maintenance assistance as funds allowed. In 1987, Superintendent Weaver initiated meetings with the Idaho State Historical Society on what should be done to stabilize the structure and make it available to the public. [179] The Pierce Courthouse was opened to the public for the first time in the summer of 1990. [180]

One persistent management concern was how to keep the cooperative sites tidy. Many of these sites were quite remote from the park headquarters and could only be visited by park staff intermittently. Litter accumulated around the wayside signs. Vandalism was not uncommon, especially at secluded sites such as the Weis Rockshelter. As a matter of fiscal necessity, the NPS has tried to enlist the park's partners in controlling the litter problem, but the park administration has not always received the support it desires. For example, during the 1980s many cooperative sites with the Idaho Department of Highways sometimes became unacceptably trashy by national park standards. State highway department officials, however, did not want to give the problem high priority. In recent years, the Park Service has earmarked funds for litter control at many of these sites. [181] Maintenance or interpretive personnel patrol the sites on a bi-weekly basis.

Another management concern has been the need to delineate boundaries for the protection of cooperative sites. In 1982, the Nez Perce Tribe proposed a housing project on the grounds of old Fort Lapwai. The project threatened to intrude on the historic scene. As the Park Service, the BIA, the State Historic Preservation Office, and the tribe all got involved in the issue, it became clear that the parties to the cooperative agreement covering the Fort Lapwai site had not agreed to any boundary definitions. Many cultural resources were lost during the initial phase of housing development. The site still lacks boundaries. Indeed, several other sites still lack boundaries, including Ant and Yellow Jacket, Coyote's Fishnet, Weis Rockshelter, Craig Donation Claim, Clearwater Battlefield, and the first Lapwai Mission. [182]

National Historic Trails

Nez Perce National Historical Park has been associated with the development of two national historical trails: the Lewis and Clark Trail and the Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail. Both trails intersect a number of sites within Nez Perce National Historical Park.

Efforts to establish a trail of commemorative markers along the route of the Lewis and Clark expedition began as early as the 1930s. A private organization called the Lewis-Clark Trail Commission led this effort, which focused initially on marking and developing sites along the expedition route between St. Louis and the mouth of the Columbia River. In 1948, the NPS recommended that a "Lewis and Clark Tourway" be established along the Missouri River from St. Louis to Three Forks, Montana. In the 1950s, conservationist J.N. "Ding" Darling led an effort to develop the historic route into a recreational trail. In 1962, Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall directed the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation (BOR) to analyze the proposal and formulate a development plan. The BOR completed its report in 1965, and included its concept for a Lewis and Clark national scenic trail in its 1966 report to Congress, "Trails for America: Report on Nationwide Trails Study." [183]

President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the National Trails System Act (P.L. 90-543) on October 2, 1968. The act listed the route of the Lewis and Clark expedition for study and possible designation as a National Scenic Trail. The BOR identified a 3,700-mile route and recommended that it be designated under a new category to be called National Historic Trails. The National Parks and Recreation Act of 1978 (P.L. 65-625) amended the National Trails Act to include this designation, and named the Lewis and Clark Trail as one of four National Historic Trails. [184]

Local efforts to commemorate the expedition route through northern Idaho received a large boost from the construction of U.S. Highway 12 over Lolo Pass and its designation as the "Lewis and Clark Scenic Highway" in the early 1960s. In 1966, Idaho citizens formed the Idaho Lewis-Clark Trail Committee and elected the retired forest supervisor of the Clearwater National Forest, Ralph Space, as its chairman. Like the Lewis and Clark Trail Commission which Congress had established two years earlier, the local organization assumed the role of stimulating government agencies to identify, mark, and preserve the trail. Governor Robert E. Smylie advised the committee that it must coordinate planning with the NPS since the commission's decisions might have an impact on the Nez Perce National Historical Park. [185]

The National Trails System Act assigned administrative responsibility of the trail to the Secretary of the Interior, and delegated responsibility for long-term administration and preparation of a comprehensive management plan to the Midwest Regional Office of the National Park Service. The act required the Secretary to submit the plan to Congress by September 30, 1981. The Midwest Regional Office sought input on the plan from Nez Perce National Historical Park in 1980. Specifically, the project team sought advice from park officials in identifying and evaluating historic and recreational resources where the Lewis and Clark Trail passed through Nez Perce country. [186]

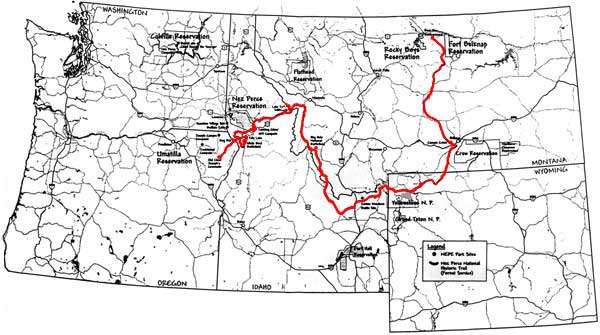

By that time, discussion was well underway for designation of a Nez Perce or Nee-Me-Poo National Historic Trail ( Figure 5). The first milestone in this effort was reached in 1965 with the inclusion of the Lolo Trail as a site in Nez Perce National Historical Park, and its designation as a National Historic Landmark. The feasibility studies for the park recognized the historical significance of the Nez Perce Tribe's traditional trail across the Bitterroot Range which Lewis and Clark followed in 1805 and 1806. Like other sites in the park, the Lolo Trail site was not designated by boundaries; indeed, portions of it remained obscure. Park officials worked with U.S. Forest Service officials from the Clearwater National Forest to locate precisely where the trail existed. In any event, the Lolo Trail designation served to highlight the connection between the route followed by Lewis and Clark and the trail which the Nez Perce people had used historically. [187]

|

| Figure 5. Nez Perce National Historic Trail. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

As the centennial year of the Nez Perce War of 1877 approached, various entities expressed interest in having portions of the 1,200-mile route taken by the Nez Perce (including that portion which followed the Lolo Trail) designated as a Nez Perce National Historic Trail. The Appaloosa Horse Club, Inc., which organized a commemorative trail ride over a section of this route each summer, inquired about the project in 1975. Superintendent Jack Williams outlined for the club the criteria which were normally applied in evaluating a trail's suitability for designation as a national historic trail. Williams explained to the members that for a study to be initiated, "a request to the Secretary of the Interior by your Congressman recommending various outstanding segments of the Nez Perce War Trail is needed." [188] In 1976, Congress amended the National Trails System Act to authorize a study of the Nez Perce or Nee-Me-Poo Trail. The act called for a joint study by the Park Service and the Forest Service. The agencies submitted the joint report to the public review process after 1982, and Congress designated the Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail in 1986 (P.L. 99-445). To the surprise of many in the Park Service, the law placed the trail under the administration of the Forest Service. It remains one of the few units in the National Trails System administered by that agency. [189]

The Forest Service's first coordinator for the Nez Perce Trail, Jim Dolan of the Northern Regional Office in Missoula, Montana, asked Superintendent Roy Weaver to help him establish an advisory council for the trail. Weaver arranged for a representative of NPTEC as well as a representative of the Nez Perce at the Colville Indian Reservation to be on the council. The organizational meeting was held at the park on February 11, 1987. [190] Following formal designation of the trail on July 19, 1991, the Nez Perce National Historic Trail Foundation was created. Most of the foundation's members were formerly on the advisory council. [191]

Owing to the distance between the Nez Perce groups in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho and the Forest Service trail coordinator in Missoula, Montana, the park was often asked to assist with administrative details. NPS and Forest Service officials found that they had to work together to avoid duplication of effort. Some members of the Park Service wondered whether the administration of the trail would someday pass to their agency. Such a change would lessen confusion in the public's mind between the trail and the park, and would simplify management of overlapping sections of the Nez Perce and Lewis and Clark trails as the latter approached its bicentennial celebration. [192]

Although the Park Service had not been designated the lead agency for the Nez Perce Trail, the establishment and administration of this new entity under the aegis of the U.S. Forest Service anticipated two major trends in the development of Nez Perce National Historical Park in the 1990s. First, the trail focused attention on the Nez Perce War of 1877. In this sense, the designation of the trail anticipated later park additions legislation which was to expand the number of park sites relating directly to the war. Together with the park additions, the Nez Perce Trail altered the interpretive thrust of the park story, increased the amount of emphasis on the conflict between Nez Perce and white and the story of the war itself. Second, the trail spanned four states (Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming), greatly expanding the number of congressional members and constituencies with whom the park administration needed to involve itself. Specifically, it underlined the fact that the Nez Perce are a divided people, with separate bands located in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Canada as a legacy of the War of 1877. Henceforth, the park administration would need to consult not only with NPTEC, but with representatives of Nez Perce groups in Washington and Oregon as well.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jun-2000