|

NEZ PERCE

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER EIGHT:

NEW ADDITIONS

Introduction

In 1992, fourteen sites in Oregon, Washington, Montana, and Idaho were added to Nez Perce National Historical Park, making it the most geographically diffuse unit in the national park system. The additions were consistent with the original conception of the park as a series of sites, or "string of pearls," whose significance derived from their historical association with Nez Perce country. Nevertheless, with so many sites spread across such a wide area, it remained to be seen whether the park additions would ultimately strengthen this imaginative park idea or stretch it to the breaking point.

It seems probable that the Nez Perce National Historical Park Additions Act of 1991, signed into law in October 1992, constitutes a watershed in the park's history. While the administrative adjustments to the park additions are only now unfolding, the campaign for the additions, the NPS feasibility studies on the proposed additions, and the legislative history of the 1992 act are now a closed chapter in the administrative history of Nez Perce National Historical Park.

The proposal to amend the original park act by adding sites outside of Idaho first surfaced in the 1960s, practically went dormant during the 1970s, and reawakened in the mid-1980s. It culminated with a legislative campaign during 1990-1992. The first section of this chapter traces the early development of this proposal through 1972. The next section examines what was virtually a second round of local initiatives and NPS studies in the 1980s. The third section summarizes the legislative history of the Nez Perce National Historical Park Additions Act of 1991. The fourth section considers some of the administrative dilemmas that this uniquely expansive park posed, with particular reference to the pre-existing NPS site of Big Hole National Battlefield, now embraced within the park. The last section of the chapter notes some recent administrative initiatives that have stemmed directly from the park additions. These seem to indicate dramatic new directions for the park's future.

The 1969 Park Additions Study

Conceptually, Nez Perce National Historical Park embraced a distinct region of the West that the park's creators defined as "Nez Perce country." Statutorily, the park was confined to the "Nez Perce country of Idaho." Apparently Assistant Secretary of the Interior John Carver, a Boise native, favored this limitation as a practical matter, assuming that a national historical park which crossed state lines would be harder to sell in Congress. But the act's inconsistency in this respect was evident because the aboriginal homeland of the Nez Perce people obviously predated state lines and extended into what is now northeastern Oregon and southeastern Washington. Moreover, the War of 1877 had taken the non-treaty portion of the tribe on a 1,300-mile journey into western Montana, Yellowstone National Park, and finally north central Montana. Survivors of the war eventually became scattered between Canada, the Umatilla Indian Reservation in Oregon, the Colville Indian Reservation in Washington, and the Nez Perce Indian Reservation in Idaho. The Nez Perce Trail, battlefield sites in Montana, and sites reflecting the Joseph band's exile on the Colville Indian Reservation all comprised important parts of the Nez Perce story and actually lay beyond the bounds of the aboriginal Nez Perce homeland. The main concept of the park additions was to correct the inconsistency between the park idea and its authorizing legislation and allow the Nez Perce story to unfold over a broader canvas.

The impetus for park additions originally came from citizens of the Wallowa country of northeastern Oregon. In the fall of 1967, Dean B. Erwin of Enterprise, Oregon, and Harold H. Haller of LaGrande, Oregon, wrote their congressional representatives and state governor protesting that the Nez Perce National Historical Park should not have been limited to Idaho. In December 1967, Northeast Oregon Vacationland, Inc., of which Haller was president, passed a resolution requesting that certain sites in Wallowa County be considered for inclusion in the park. Oregon Senators Mark O. Hatfield and Wayne L. Morse and Representative Al Ullman sent three separate inquiries to the Interior Department based on these requests. [332]

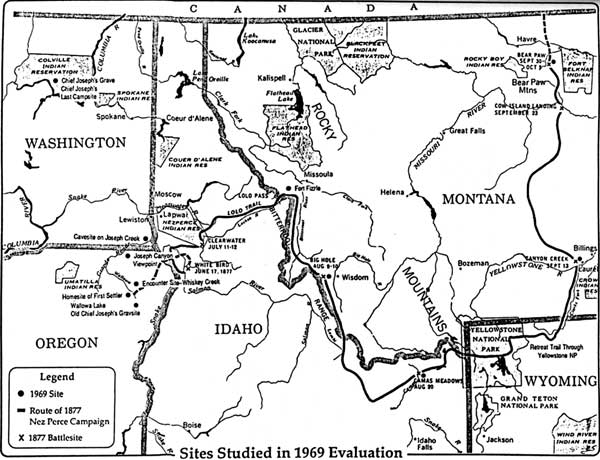

The Park Service responded to the congressional inquiries by fielding a study team in the fall of 1968. The team inspected seven sites in Oregon and Washington: the gravesite of Chief Joseph the Older near the town of Joseph, Oregon, on the shore of Wallowa Lake; the site of Chief Joseph the Younger's first encounter with settlers; the homesite of the first American settler in the Wallowa Valley; Joseph Canyon viewpoint on Oregon State Highway 3, a cave site on Joseph Creek, Asotin County, Washington, that was reputedly the birthplace of Chief Joseph the Younger; the last campsite of Chief Joseph the Younger; and the gravesite of Chief Joseph the Younger. The study team also gave consideration to sites along the route taken by non-treaty Nez Perce in the War of 1877 although it did not visit them in the field. These included Camas Meadows, Idaho; Fort Fizzle, Montana; Big Hole National Battlefield, Montana; Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming; and Bear Paw Battlefield, Montana (Figure 6). [333]

The team concluded that two of the Oregon sites — the gravesite of Chief Joseph the Older and the Joseph Canyon viewpoint — were significant and suitable additions to the park, while the other two Oregon sites together with the cave site in Asotin County, Washington, did not have national significance. The last campsite and gravesite of Chief Joseph the Younger, both situated on the Colville Indian Reservation, deserved recognition but were not suitable additions because they were too far from the rest of the park. The sites in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming associated with the war were more or less significant but also seemed too distant to be added to the park. [334] In effect, the team was suggesting that the park could cross state lines but it should still stay within the area of the Nez Perce homeland; "Nez Perce country" should not be redefined to include the trail of the Nez Perce in 1877 nor the scenes of the non-treaty Nez Perces' exile following their defeat.

The team closed its 37-page report by proposing two alternatives for bringing the two significant Oregon sites into the park. One alternative would involve government purchase of 5.1 acres of fee land and 100 acres of scenic easement surrounding the elder Chief Joseph gravesite at Wallowa Lake. The other alternative would accept this site under current ownership and the Park Service would administer it through a cooperative agreement. In other words, the question of federal acquisition of this small parcel of land was critical. Regardless of whether the federal government acquired the site or not, the addition of the two Oregon sites would require Congress to amend the original park act by removing the stipulation that the park would be confined to Idaho. [335]

|

| Figure 6. Sites Studied in 1969 Evaluation (NPS map.) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Congressman Ullman introduced H.R. 1189, a bill to amend the Nez Perce National Historical Park Act, on January 22, 1971. The House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs requested more information from the Park Service in support of Ullman's bill. Specifically the committee needed data on the current land status of the two sites, the kind of resources the sites contained, and the Park Service's land requirements in order to protect them adequately, and details on how the Park Service would develop the two sites as well as cost estimates for each. The Park Service did not commit the necessary staff time to compile this information, and so the bill languished in committee. A frustrated Alvin Josephy complained that "something seems to have gone awry in the Washington office." [336] But Superintendent Jack Williams attributed the Park Service's neglect of the House committee's request to lower echelons in the agency. [337]

The newly operational Pacific Northwest Regional Office produced an environmental impact statement on the proposed Oregon park additions in the fall of 1972, and the Washington office completed a legislative support package in December 1972, but the Ullman bill was never reintroduced. [338]

Despite the disappointing outcome, this early effort to make the park more nearly encompass all of "Nez Perce country" had lasting repercussions. The most important result was to spur Nez Perce tribal interest in the Oregon, Washington, and Montana sites. As early as November 1967, Superintendent Burns and NPTEC Chairman Richard Halfmoon travelled to the gravesite of Chief Joseph the Younger near Nespelem, Washington, with the idea that the park might some day encompass this site. In 1969, the additions study team made initial contact with Joe Redthunder of Nespelem, the oldest living descendent of Chief Joseph. [339] With the creation of Nez Perce National Historical Park, Nez Perces began to take an interest in the battlefield sites in Montana as well. Josiah Red Wolf, the last Nez Perce survivor of the War of 1877, had lost his mother and sister in the Battle of the Big Hole when he was five years old. Now in his nineties, he went to Big Hole National Battlefield and broke ground for the new visitor center, marking the first time he had been back to this tragic scene of his youth. [340] In the centennial year of the war, several hundred Nez Perces traveled to the Bear Paw Battlefield to take part in ceremonies. There they found the state's historical markers inaccurately placed and in some cases defaced. That fall, NPTEC passed a resolution urging that the state of Montana transfer this state park to the federal government for inclusion in the Nez Perce National Historical Park. The NPS responded that the War of 1877 was already adequately represented in the national park system by Big Hole National Battlefield and the White Bird Battlefield. [341]

A second important result of the early effort to expand Nez Perce National Historical Park was the attention it brought to the Old Chief Joseph gravesite. Not only did local citizens of Wallowa County become interested in better preserving the site, but Nez Perces of the Umatilla Indian Reservation in Oregon and the Nez Perce Indian Reservation in Idaho also became better apprised of the situation. In 1972, NPS officials negotiated with the owner of the surrounding land, the Associated Ditch Company. The Associated Ditch Company expressed strong opposition to the initial proposal of a 100-acre scenic easement. Following those negotiations, the NPS revised its proposal to involve acquisition of the existing 5.1-acre parcel (owned by the Bureau of Indian Affairs) plus acquisition of a maximum of 8 acres in fee. [342] This proposal formed the basis for renewed discussion in the 1980s.

The Park Additions Study Redux

A proposed condominium development near the site of the Old Chief Joseph grave reignited the park additions proposal in the mid-1980s. In August 1985, NPTEC passed a resolution affirming the significance of the Old Chief Joseph gravesite in Wallowa County, Oregon, and expressing opposition to any commercial or residential development of the surrounding land. [343] In December 1986, Stanlynn Daugherty, chairperson of the Historical Park Committee of Enterprise, Oregon, wrote to Oregon Senator Bob Packwood requesting that the NPS conduct a feasibility study and support a legislative amendment of the park's enabling act. [344] Senator Mark Hatfield and Representative Robert F. Smith received other inquiries by constituents who supported acquisition of the site. This correspondence, coupled with a public meeting in Enterprise on November 7, 1986, attended by park officials, representatives from the Nez Perce and Umatilla Tribes, local state park officials, and area citizens, led to an initiative by the NPS's Pacific Northwest Regional Office in 1987. Acting without any official request from Congress for a feasibility-suitability study, the regional office formed a task force with the object of reviewing and updating the 1969 additions study. Specifically, NPS officials perceived an opportunity to reopen the issue of a multi-state park, and to lift the ceilings on land acquisition, easements, and development. [345]

Regional Historian Stephanie Toothman, serving as team leader, obtained a minimal $5,000 for the project from the regional director, the most that could be afforded without a congressional request. The team adopted a two-pronged strategy for determining the suitability and feasibility of park additions: NPS Chief Historian Ed Bearss and former Idaho State Historic Preservation Officer Merle Wells would develop National Landmark recommendations for key sites, buttressing the case for the suitability of park additions; Toothman, the superintendent, and other team members, meanwhile, would reopen the question of enlarging the park beyond the state of Idaho, focusing on the feasibility of park additions. The team re-established contact with Joe Redthunder and other members of the Joseph Band of Nez Perce as well as tribal representatives of the Umatilla and Nez Perce Tribes, and made a whirlwind tour of proposed sites in Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. As project funding was exhausted after this tour, Toothman was left to write the report primarily on her own, with some help from Superintendent Weaver. [346]

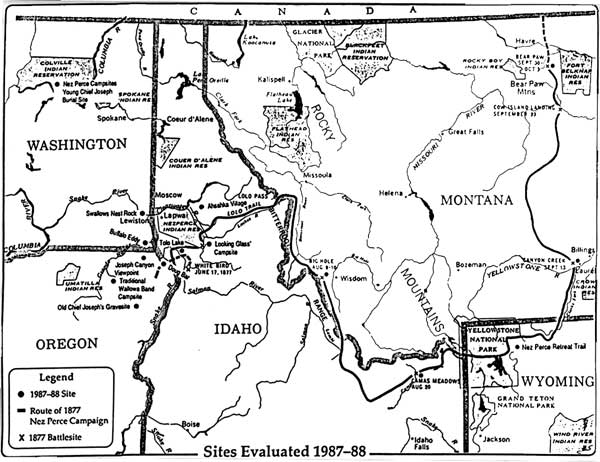

The report exceeded the parameters of the 1969 study and evaluated the Montana and Wyoming sites on the same basis with the Washington, Oregon, and Idaho sites. The study team considered a number of new sites and accepted the idea of expanding the park into a five-state area. Altogether, seventeen sites were evaluated and fourteen were determined to be suitable and feasible for addition to the park. The fourteen sites considered suitable and feasible for addition were Tolo Lake, Looking Glass's 1877 Campsite, and Camas Meadows Battle Sites in Idaho; Buffalo Eddy and Dug Bar on the Idaho-Washington boundary; Joseph Canyon Viewpoint, Old Chief Joseph's Gravesite and Cemetery, and Traditional Campsite at the Fork of the Lostine and Wallowa rivers in Oregon; Hasotino Village, Burial Site of Chief Joseph the Younger, and Nez Perce Campsites in Washington; and Big Hole National Battlefield, Bear Paw Battlefield, and Canyon Creek in Montana. The three sites that the team rejected were Ahsahka Village Archeological Site on the Clearwater River, Swallows Nest Rock, and Fort Fizzle (Figure 7). [347]

One of the keystones of the additions proposal was Old Chief Joseph's Gravesite and Cemetery. Superintendent Weaver contended that the site offered a vital opportunity to interpret the story of the non-treaty Nez Perces who had lived in the Wallowa Valley and had constituted about one third of the tribe in the 1870s. Their story was not well-interpreted elsewhere. The beautiful setting of the Wallowa Valley would help provide an understanding of the "sorrow and difficulty which plagued those Nez Perces who were forced out of their homeland," Weaver argued. Moreover, the site would provide a suitable west entrance to the park. He added candidly, "this is an unusual Park and it is almost impossible to properly orient visitors to the Park before they have passed through much of it." [348]

|

| Figure 7. Sites Evaluated in 1987-1988 (NPS map.) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Since the report had not been requested by Congress and was not an officially funded suitability-feasibility study, NPS planners and the legislative liaison staff in the Washington office did not know what to do with it. [349] Various sections containing support data on funding, staffing, and socio-economic conditions were alternately included and deleted. In May 1990, Regional Director Charles H. Odegaard finally forwarded the report to Director James M. Ridenour, noting that it lacked "the full array of legislative support data." The report did not contain estimates for land acquisition costs, nor a detailed development schedule, nor data sheets to indicate estimated increased operational costs. Perhaps most importantly, the report did not propose site boundaries nor detail land ownership status of the sites. These shortcomings, stemming from the report's unusual genesis, tended to disguise problems that would trouble both the legislative effort and management. The report projected a need for some modest visitor contact facilities, landscaping and site stabilization, signing, fencing, and parking development, for a total cost of approximately $175,000. Odegaard stated that the additions had the support of Oregon's Senators Packwood and Hatfield, and Montana's Governor Stan Stephens and Senator Max Baucus. [350] With the circulation of the additions study, the stage was set for the campaign to have the Nez Perce National Historical Park Act amended.

The Nez Perce National Historical Park Act of 1991

The legislative campaign for additions to the Nez Perce National Historical Park demanded an unprecedented level of cooperation between the different groups of Nez Perces on the Umatilla, Colville, and Nez Perce Indian Reservations. Leaders of the separate Nez Perce bands had to overcome their historical mistrust and animosity toward one another dating back to the missionary period, the Treaty of 1863, and the War of 1877. The situation was complicated by the fact that the Nez Perce groups in Washington and Oregon belonged to "confederated tribes," and NPTEC did not want to involve these other tribes in the park. Fortunately, the Nez Perce people had already made a start toward improved relations in discussions pertaining to the designation of Nez Perce National Historic Trail in the mid-1980s.

Representatives of the Nez Perce band on the Umatilla Indian Reservation worked closely with NPTEC representatives concerning the proposed sites in Wallowa County in 1986-1988. Contacts between NPTEC and members of the Joseph band of Nez Perces who lived on the Colville Indian Reservation were more sensitive. The mostly Christian Nez Perces of the Nez Perce Indian Reservation, many of whose ancestors had refused to aid Chief Joseph and his followers in the War of 1877, now wanted to embrace that historical figure as part of a shared past. NPTEC Chairman Charles Hayes explained in a press release in June 1990, "Our people want to heal the wounds of the past and share our history. The rich culture and history of the Nez Perce can teach us lessons today. Chief Joseph was a statesman and a true American hero." [351] The Nez Perces of the Colville Indian Reservation, however, were inclined to guard their traditional ways and history jealously. Nez Perces of the Colville Indian Reservation insisted that they were the only "true descendants of Chief Joseph," and should therefore have greater influence than NPTEC on all sites relating to the War of 1877. [352] NPTEC found this claim to be politically unacceptable and historically unfounded. [353] Many Nez Perce combatants in the War of 1877 belonged to other bands. There were descendants of Ollokot, for example, at Lapwai, Idaho and Pendleton, Oregon. [354] To complicate matters further, some Nez Perces on the Colville Indian Reservation objected to Joe Redthunder discussing the additions with NPS officials as if he represented the band. [355] Official representation of the Chief Joseph Band would remain a problem until the final hours of the legislative campaign.

These problems notwithstanding, the Nez Perce Tribe asked the congressional delegations of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Montana to consider sponsoring a bill as soon as the NPS released the 1989 draft report on park additions. [356] Senator James A. McClure and Representative Larry Craig of Idaho took the lead and introduced companion bills in the Senate and House on June 28, 1990. Senators Max Baucus and Conrad Burns of Montana, Brock Adams of Washington, and Steve Symms of Idaho cosponsored the Senate bill 2804, and Representatives Jim McDermott of Washington and John Rhodes of Arizona cosponsored the House version. This was a strong showing of regional, bipartisan support. The Senate Subcommittee on Energy and Natural Resources held a hearing on S.2804 on July 27, 1990, and reported favorably on the bill, with amendments, on September 19. [357] The Senate passed S.2804 on October 18, but the House failed to vote on the measure before Congress adjourned.

In the long run this appears to have been fortunate, for S.2804 as amended had some peculiar provisions that were subsequently deleted in the Nez Perce National Historical Park Additions Act of 1991. First, it amended the Act of May 15, 1965 to include potential sites in Oregon, Washington, Montana, Wyoming, and Oklahoma. Although the Park Service's additions study did not consider any sites in Oklahoma, the Senate bill included this state in the event that the Secretary of the Interior would later identify sites associated with the exile of Nez Perce tribal members to Oklahoma Territory for addition to the park. Second, the Senate bill went beyond the Park Service additions study with respect to sites in Montana. "Additional sites to be designated," the bill stated, "shall include but not be limited to Virginia City, Montana; Lolo Pass, Montana; St. Mary's Mission, Montana, Bannack State Park, Montana; and Pompeys Pillar, Montana." [358] Most of these sites do not relate to Nez Perce country, and their inclusion in the park would have created formidable problems for interpretation. Third, for reasons that remain unclear the Senate subcommittee found it advisable to amend the bill by stipulating that the individual components of the park would be administered by the respective regional division of the National Park Service in which the component was located. This would have made it even more difficult for the park to function as a single administrative unit of the national park system.

The Pacific Northwest Regional Office completed a final draft of the additions study and formally transmitted it through NPS Director James Ridenour to Congress in 1990. Senator Larry Craig, formerly a member of the House, introduced new legislation, Senate Bill 550, in the 102nd Congress. Representative Pat Williams of Montana introduced a similar measure, House Resolution 2032, in the House. Again, members of the Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Montana delegations cosponsored both bills. Absent from these bills were the awkward provisions contained in the previous Senate version. The Senate passed S.550 with amendments in August 1991, and the House passed HR.2032 with amendments two months later. The Senate then added several amendments to the House bill and passed it on November 27, 1991.

It now remained for the House to repass the bill as amended by the Senate. The chief difference between the House and Senate versions of the bill concerned limits on the power of the federal government to acquire land from private property owners, and it was on this point that congressional debate focused in the following year. [359]

The Old Chief Joseph Gravesite in Wallowa Country, Oregon, the site that had initially stirred interest in the park additions, now became the most controversial issue. Congress had already appropriated $300,000 for the acquisition of eight acres around this site. The funds had been allocated to the U.S. Forest Service for F.Y. 1991 on the assumption that the government was negotiating with a willing seller. Subsequently, the landowner had become interested in subdividing the land for residential development and no longer wanted to sell. This raised the controversial issue of whether any land involved in the bill could be taken by condemnation. The House amendments passed in 1991 significantly scaled back the power of eminent domain authorized by the bill by allowing it at only four specific sites. But this did not go far enough for the Senate, which eliminated the power of eminent domain altogether and left the Park Service with no ability to acquire and protect these sites. [360]

On June 29, 1992, Representative Bruce Vento of Minnesota introduced House Resolution 504 to dispose of the Senate's amendments to House Resolution 2032. Essentially this resolution called for an amendment of the Senate amendments that would allow condemnation authority under carefully prescribed circumstances. The Secretary of the Interior would not be able to acquire land for the park without the consent of the owner except within the four parcels previously designated by the House bill, including the eight-acre parcel around the Old Chief Joseph Gravesite. Moreover, the Secretary would have to find that the nature of the land use had changed or was about to change significantly, and that the acquisition of the land was essential for the purposes of the park. In short, Representative Vento maintained, condemnation authority was a necessary management tool but also a tool of last resort. [361]

Intense negotiations followed. Superintendent Walker met with the mayor of Joseph, the landowner, local citizens, tribal representatives, and Forest Service officials. The meeting resulted in an agreement whereby the Forest Service would transfer the $300,000 appropriation for land acquisition to the Park Service. Meanwhile, NPTEC Vice Chairman Charles Hayes and Joe Redthunder went to Washington to lobby Oregon's Senator Mark Hatfield, who now opposed the bill. Their pleas, together with the House resolution's stipulation that no more than eight acres could be acquired at the Old Chief Joseph Gravesite without the willing consent of the landowner, persuaded Hatfield to drop his opposition to the bill. [362]

There remained one final point of controversy which nearly doomed the bill. On October 5-6, the Chief Joseph Band met to discuss the legislation and then voted to oppose it. They contended that they had not been consulted and that they did not want the Younger Chief Joseph's gravesite developed, publicized, and subjected to vandalism. [363] The attorney for the Confederated Colville Tribes notified Washington's Senator Slade Gorton, who promised to stop the bill. A mere two days remained before the bill was scheduled for a vote. Superintendent Walker and Allen Slickpoo initiated a meeting with the Colville Nez Perce at Nespelem and drove through the night to get there by 8:00 a.m. They assured the Chief Joseph Band that the Colville Confederated Tribes would retain ownership of the sites on the Colville Indian Reservation and that the sites would only be activated and developed at the tribe's initiative. At 10:30 a.m. the band voted 32 to 8 in favor of the bill; the tribal attorney faxed the news to Senator Gorton's office, and the Senator lifted his stop on the bill. [364]

Prior to the Senate's vote, Gorton asked for clarification of the Chief Joseph Band's prerogatives in the development and interpretation of the park additions. The following letter from NPTEC Chairman Sam Penney to Colville Confederated Tribes Chairman Eddie Palmanteer, Jr., was inserted in the Congressional Record:

Dear Chairman Palmeteer (sic): I am very concerned about the Nez Perce Park Additions Bill and its chances of passing this 102d Congress. The bill would authorize the National Park Service to designate specific sites significant to the history and culture of the Nez Perce people. The hold placed on the bill by Senator Gorton threatens to kill this bill. If this bill dies, it is highly unlikely we will be able to stop condominium development from encroaching upon the Old Joseph Monument site near Wallowa Lake. This has been our primary driving force in pushing this additions bill. I want to provide the following assurances to the Chief Joseph Band of Nez Perce and to the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation:

1. Categorically and without exception, the Chief Joseph Band of Nez Perce will have complete and total purview over any sites designated under the Nez Perce National Historical Park within the boundary of the Colville Reservation. If the Chief Joseph Band of Nez Perce on the Colville Reservation chooses not to establish any recognition of the sites, then the sites would remain inactive.

2. The Chief Joseph Band of Nez Perce on the Colville Reservation will be consulted and participate in the interpretation of all other sites of the park system, with the exception of those located within the boundary of the Nez Perce Reservation.

3. If the Chief Joseph Band of Nez Perce requests, the Nez Perce Tribe will support an amendment to the Nez Perce National Historical Park in the 103d Congress to remove the Washington State sites from the park system.

I hope this letter addresses your concerns.

Sincerely,

Sam Penney,

Chairman, Nez Perce Tribal Executive Committee [365]

After this significant maneuver by Gorton on behalf of the Colville Confederated Tribes, the Senate passed the bill with unanimous consent.

Big Hole National Battlefield and the Unit System

Big Hole National Battlefield had a long association with Nez Perce National Historical Park that predated the Nez Perce National Historical Park Additions Act of 1991. In fact, the national battlefield predated the national historical park by many decades. The 1877 battlefield site was set aside as a military reserve in 1883 and designated a national monument in 1910. It was transferred from the War Department to the National Park Service in 1933 and placed under the administration of the Yellowstone National Park superintendent. Expanded from 5 acres to 195 acres by executive order in 1939, Big Hole Battlefield remained virtually undeveloped until Mission 66. The Mission 66 program for Big Hole Battlefield provided for the construction of a visitor center and administration building, development of trails, landscaping, and interpretive signs, and marking of the monument boundary. [366] Beginning in 1957, Yellowstone ranger Robert Burns was assigned to the area from June through September as the first on-site administrator of the unit.

Burns, who later served as first superintendent of Nez Perce National Historical Park from 1965 to 1968, thought that Mission 66 planning for Big Hole Battlefield was an important antecedent in the creation of the Idaho park because it awakened interest in the Nez Perce story. [367] He and Idaho historian Samuel M. Beal were instrumental in getting the Mission 66 program approved by a skeptical regional director. Burns also relayed to his superiors his strong impression that a large percentage of visitors to the Big Hole Battlefield were sympathetic to the Nez Perce cause, and this too seemed to consolidate NPS support for the unit as well as the Nez Perce National Historical Park idea. A visitor center was built at the battlefield in 1968. [368]

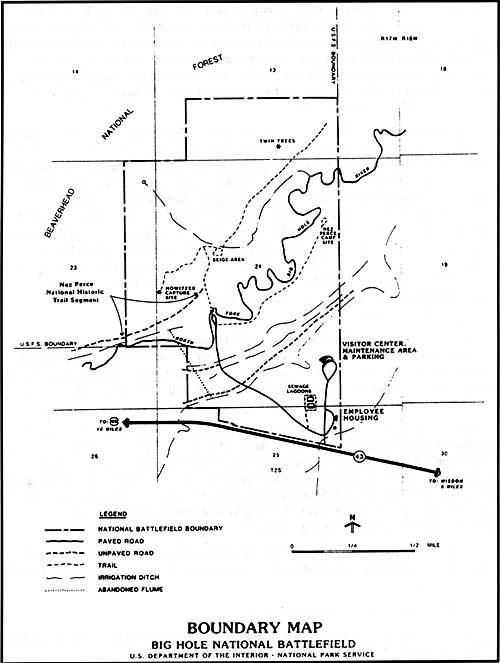

Big Hole Battlefield National Monument was redesignated Big Hole National Battlefield by an act of Congress on May 17, 1963. As amended in 1972, this act appropriated $42,500 for acquisition of approximately 466 acres of additional land (Figure 8). In 1987, certain administrative functions of Big Hole National Battlefield were transferred to Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site. [369] The Nez Perce National Historical Park Additions Act of 1991 included Big Hole National Battlefield within the park additions.

The act placed Big Hole National Battlefield in a somewhat anomalous position within Nez Perce National Historical Park. For example, Section 2 of the act expressly added Big Hole National Battlefield to the park, but it did not change the national battlefield designation nor annul this unit's own authorizing legislation. Indeed, the act directly acknowledged the site's dual status in its provision that "Lands added to the Big Hole National Battlefield, Montana, pursuant to paragraph (10) shall become part of and be placed under the administrative jurisdiction of, the Big Hole National Battlefield, but may be interpreted in accordance with the purposes of this Act." Moreover, the site retained its own base funding as a distinct unit within the national park system. The Big Hole National Battlefield superintendent and staff remained in place at the visitor center and administration building. [370]

|

| Figure 8. Map of Big Hole National Battlefield. (NPS map.) |

It appears that Congress's intent was to allow the Park Service some latitude in formulating how this unit and the other Montana units would be administered. Indeed, NPS officials at the field level began conceptualizing how the expanded park could most effectively be administered several months before Congress finally enacted the legislation. Nez Perce National Historical Park Superintendent Frank Walker, Big Hole National Battlefield Superintendent Jock Whitworth, and Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historical Site Superintendent Eddie Lopez had been working together on the legislation since 1990. Walker believed that the most effective way to manage the Montana sites would be from Big Hole National Battlefield and the Rocky Mountain Regional Office. To avoid duplication of efforts between the Pacific Northwest and Rocky Mountain regions of the National Park Service, certain parkwide administrative matters such as general management planning, interpretive planning, and relations with the Nez Perce Tribe could be handled out of one region.

Pacific Northwest Regional Director Charles H. Odegaard supported this concept and broached the prospect of a cooperative agreement with the Rocky Mountain Region on October 19, 1992, three weeks after the Senate passed the bill. Odegaard suggested that the two regional directors decide between them which region would take the lead. The first task of the lead office would be to prepare a memorandum for activation of the new additions. [371]

Even this arrangement proved to be unwieldy, however. In May 1993, Rocky Mountain Regional Director Bob Baker was helping conduct a Purpose and Significance Workshop for Big Hole National Battlefield when he realized that it was difficult to interpret Big Hole separately from the other sites in Nez Perce National Historical Park. In March 1994, Baker and Odegaard agreed to an exchange: the three Montana battle sites for the Oregon National Historic Trail. The exchange took place on June 10, 1994. Thus, the Montana sites were brought under the administration of the superintendent at Spalding. [372]

While Big Hole Battlefield and the farflung Montana sites posed the most immediate challenge to park administration, the sheer number of new sites in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington created more complexity too. Given the myriad number of land owners of the park's 38 sites, the NPS would need cooperative agreements with various state, local, and other federal agencies, four tribal governments, and several private organizations. For example, several sites were part of the Nez Perce National Historic Trail and would involve cooperative management with the Forest Service. It was approximately a five-hour drive from Spalding to Nespelem, Washington, and twice that from Spalding to the Bear Paw Battlefield in Montana. Such a complicated park could not be administered out of one or even two administrative locations. [373]

On January 13-14, 1994, the superintendents of Nez Perce National Historical Park, Big Hole National Battlefield, and Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site convened with staff from the Personnel Division of the Pacific Northwest Regional Office to revamp the park's organizational structure. In essence, the plan replaced traditional functional divisions with five management units based on logical clusters of sites. Each of these units would handle daily operations, cultivate local community support, and develop working relations with the park's partners in that area. Technical activities, planning, and overall coordination would be consolidated in a park-wide support unit based at Spalding. [374]

Superintendent Walker put this staff reorganization into effect in stages. The Oregon/Washington Unit was activated even before the unit organization concept was formally developed. Paul Henderson began work in August 1993 at Joseph, Oregon, as the park's first unit manager. [375] The following year Curator Sue Buchel accepted reappointment as unit manager of the Montana Unit. In addition to managing a permanent staff of five at Big Hole National Battlefield, Buchel had line authority to the park ranger at Bear Paw Battlefield. Park Ranger Otis Halfmoon established an NPS presence at Chinook, Montana and at the site. Meanwhile, Walker established the remaining management units at Spalding and Grangeville. Art Hathaway served as the manager of the Spalding unit, with primary responsibility for the visitor center operation, while Mark O'Neill became the manager of the White Bird and Upper Clearwater Units, with offices and staff in Grangeville. [376]

The unit management concept more or less reflected the contemporary regional reorganization of the national park system in microcosm. It was hoped that each management unit would function as a small park, enjoying a reasonable amount of autonomy for carrying out daily operations while benefiting from centralized administrative support services at Spalding. Superintendent Walker decentralized the administrative organization of Nez Perce National Historical Park at the same time that Director Roger G. Kennedy decentralized the administrative organization of the National Park Service regions. Both efforts were aimed at empowering employees, putting employees closer to the resources and the Park Service's constituents, and ultimately reducing administrative costs. Both plans drew inspiration from the objectives outlined in the report of Vice President Al Gore's National Performance Review, From Red Tape to Results - Creating a Government that Works Better and Costs Less.

The plan held both opportunities and risks. In order for the plan to work, the superintendent or park manager would have to supervise the unit managers lightly or else the employees in the field would only feel the weight of still another layer of bureaucracy overseeing their decisions. Unit managers, meanwhile, would have to demonstrate abilities to manage staff and develop professional relationships with a multitude of park partners, or, in other words, mirror the skills and responsibilities of the superintendent at a local level. The success of the plan would rest to a large extent on finding and retaining the right people for the unit manager jobs.

Yet with so many communities bordering on or surrounding the 38 sites that composed Nez Perce National Historical Park, decentralization of the park administration seemed to be an imperative. The benefits of having park staff on the ground from Joseph, Oregon, to Chinook, Montana, became apparent as the NPS began seeking public input in its scoping meetings for the park's new General Management Plan in the spring of 1995. Park staff looked to a future in which local communities would be more closely involved, and partnerships between the Park Service and non-government entities would be increasingly emphasized. [377]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap8.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jun-2000