|

Ninety Six National Historic Site South Carolina |

|

NPS photo | |

The Star Fort was the heart of British defenses at Ninety Six and the stone upon which Gen. Nathanael Green's well-planned siege stumbled. Although Greene and his patriot army were unsuccessful, the victorious loyalists soon abandoned the post and moved their garrison toward the coast.

The Siege of Ninety Six, 1781

The siege of this frontier post grew out of one of the great dramas of the American Revolution—the second British attempt to conquer the South. Their first campaign in 1775-76 failed. This second campaign began in late 1778 with an assault on Savannah, Georgia. On May 12, 1780, loyalists—Americans loyal to British interests—captured Charleston, South Carolina, America's fourth largest city and commercial capital of the South. By September 1780 loyalists held Georgia and most of South Carolina. A powerful army under Gen. Lord Cornwallis was poised to carry the war northward. British forces seemed unstoppable.

Surprises for the Loyalists In the fall of 1780 American patriots—those seeking independence from British rule—turned the war against Cornwallis. On October 7 he lost his entire left offensive arm and its commander Maj. Patrick Ferguson at Kings Mountain, South Carolina. On January 17, 1781, he-lost his right striking force under the command of Col. Banastre Tarleton at Cowpens. By early 1781 Cornwallis faced a resurgent Continental Army under the command of Gen. Nathanael Greene. Cornwallis drove Greene and the patriots from the field at Guilford Courthouse, North Carolina, in mid-March, but at such a cost that he and his loyalist army had to retreat to the coast. Greene did not pursue Cornwallis but set out to reduce the chain of backcountry posts held by the British.

Critical Crossroads The hamlet named Ninety Six, a political and economic center in the South Carolina backcountry, was garrisoned by 550 American loyalists led by Lt. Col. John Cruger. When Cruger took command in 1780, he used loyalist soldiers and slaves from nearby farms to reinforce the walls of the town's stockade and build the Star Fort.

Greene and his patriot army of 1,000 regulars and a few militia arrived at Ninety Six on May 21, 1781. One look at the formidable defenses, along with Greene's lack of heavy artillery, ruled out a quick, direct assault. Only a siege could bring down Ninety Six.

Greene focused on the Star Fort. Col. Thaddeus Kosciuszko, a military engineer and aide to Greene, directed the siege operations. Sappers (trench diggers) began digging a system of parallels and approach trenches through the hard clay—an exhausting labor made worse by intense heat, mosquitoes, and cannon fire from the fort. They completed the first parallel on June 1, the second on June 3, and the third on June 10. Now they were within musket range of the loyalists.

During the night of June 13 Greene's men built a 30-foot log tower close to the fort, hoping to suppress loyalist cannon and musket fire from its top. Then, Greene learned that a relief column of 2,000 British troops was marching to Cruger's aid. He resolved to storm the post before he was trapped between the two forces.

June 18—The Attack at Noon The onslaught began at noon. Col. Henry "Light-horse Harry" Lee's legion captured the Stockade Fort west of the village. Greene launched his attack on the Star Fort from the third parallel. Troops in trenches moved forward, inching four 6-pounder cannon toward the fort. But the cannon fire was not powerful enough to breach the 10- to 12-foot-thick earthen wall. Greene ordered 50 soldiers forward to prepare the way for the main army. Men with axes cut through the sharpened stakes that extended from the fort's walls, and those with hooks tried to pull down sandbags. Cruger ordered troops into the ditch surrounding the fort. Fighting hand-to-hand, loyalists drove off the patriots with both sides taking great losses.

This repulse decided the contest. The rescue column was too near for Greene to organize a general attack. Greene and his army slipped away before dawn on June 20, moving north up the Island Ford Road and across the Saluda River. Although Greene lost the siege, his offensive weakened Cruger's stronghold in the backcountry. By July the loyalists abandoned Ninety Six and moved to a post nearer the coast.

Understanding the Earthworks

The loyalists' Star Fort survived as you see it today. In 1973 and 1974 archeologists found evidence of the patriots' siege trenches and restored the old outlines, including the original contours. There are few better examples of 1700s siegecraft or of the close personal nature of battle in that day.

The Siege Trenches

Col. Thaddeus Kosciuszko, a Polish native trained in the classical methods of European warfare, knew siegecraft—if a fort could not be taken by surprise, an attacking army had to take it by force. A siege, the process of surrounding an enemy's strong point and slowly cutting off contact with the outside world, was the patriots' only hope for victory at Ninety Six.

Starting about 200 yards from the fort, sappers—trench diggers that included patriots and slaves—dug a four-foot-wide, three-foot-deep trench parallel to the fort, so that patriots could move in troops and supplies. They dug zigzag approach trenches toward the fort, mounding up the earth for protection. The zigzag pattern made it more difficult for loyalists to fire on men in the trenches. At about 70 yards, sappers dug the second parallel.

They worked their way toward the fort adding more zigzag approach trenches, gun batteries, and a third parallel at about 40 yards from the fort. From here the patriots fired at a single point, hoping to breach the wall and take the fort.

Victory by attackers or defenders always hung in the balance. Skill and luck were important factors. Conducting a textbook siege did not guarantee success either, for the loyalists were busy too—firing at the sappers and sending out nighttime raiding parties.

The Village Then and Now

Life in the Frontier Village

No one knows how Ninety Six got its name. One explanation is that Charleston traders thought this intersection of trails was 96 miles south of the Cherokee town of Keowee, near today's Clemson, South Carolina. Traders packed firearms, blankets, beads, and wares along an Indian trail called the Cherokee Path, swapping them for furs. By 1700 this trail was a major commercial artery, flowing with goods essential to a prospering colony.

A Rising Town The Cherokee Path intersected other trails here, and Ninety Six became a stopover for traders. In 1751 Robert Gouedy opened a trading post at Ninety Six, establishing it as a hub of the backcountry Indian trade. A veteran of Cherokee trade, he parlayed that enterprise into a business that rivaled some of Charleston's merchants. He grew grain and tobacco, raised cattle, served as a banker, and sold cloth, shoes, beads, gunpowder, tools, and rum. He amassed over 1,500 acres, and, at his death in 1775, some 500 people were in his debt.

In the 1750s friction grew between Indians and the settlers pushing into Ninety Six and the area. Settlers, militia, and enslaved people built a stockade around Gouedy's barn for protection, which became Fort Ninety Six. It served them well in 1760 when the Cherokee attacked twice but failed to capture the fort. After years of fighting, the Cherokee signed a treaty in 1761 that curtailed their travels beyond Keowee. Peace followed, along with a rebound in land development. The British enticed settlers to the frontier by promising protection, financial aid, free tools, and free land. Settlers flooded into the country beyond the Saluda River. Ninety Six lay in the middle of this land boom.

Who Wants Independence? On the eve of the American Revolution, Ninety Six was a prosperous community with homes, a courthouse, and a brick jail. At least 100 people lived in the area. Sentiment about independence was more divided here than along the coast. For many settlers, incentives and protection from the Cherokee created strong loyalties toward Great Britain. Others thought that the crown shirked on its promises to backcountry settlers, and they wanted independence. On November 19, 1775, in the American Revolution's first major land battle in the South, 1,900 loyalists attacked about 600 patriots gathered at Ninety Six under Maj. Andrew Williamson. After days of fighting, the two sides agreed to a truce, but patriot spirit was running high. Patriot leaders mounted an expedition to sweep away loyalist supporters. But subduing the king's friends did not bring peace. A savage war of factions broke out that lasted until 1781. In June 1781 Gen. Nathanael Greene failed to take the fort by siege. In July loyalists left the village a smoking ruin; they set fire to the buildings, filled in the siegeworks, and tried to destroy the Star Fort.

Starting Anew Within a few years a new town rose near the site of the old one. In 1787 villagers aspiring to make the town a center of learning named it Cambridge after the English university. Cambridge flourished for a while as the county seat and home of an academy. In the early 1800s the town began to decline. In 1815 a u epidemic swept the area, and Cambridge became little more than a crossroads. By the mid-1800s, both old Ninety Six and newer Cambridge were little more than memories.

Planning Your Visit

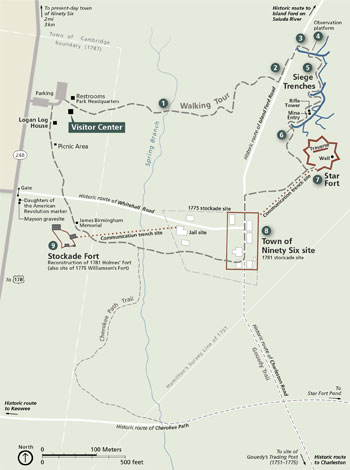

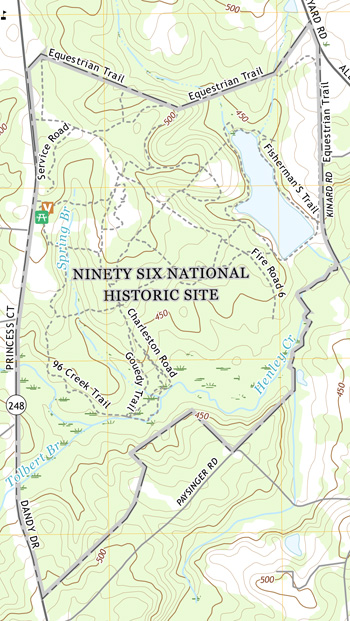

(click for larger maps) |

Visitor Center Start at the visitor center for information, maps, a museum, bookstore, and a short video. The visitor center is open daily from 9 am to 5 pm; closed Thanksgiving Day, December 25, and January 1. The park is open dawn to dusk year-round.

Activities The park offers a variety of trails, the 27-acre Star Fort Pond, and wildlife viewing. Don't miss the one-mile walking tour of the park. See the earthworks, historic roads, reconstructed stockade, sites of the 1781 siege and battle, and site of the Ninety Six village. The 1.5-mile Gouedy Trail passes the grave of Gouedy's son. The park has living history events April through November. Ask at the visitor center about special activities or visit www.nps.gov/nisi.

Accessibility We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. For information go to the visitor center, ask a ranger, call, or check our website.

Safety First The Star Fort, parallels, and other features along the siege trenches are fragile—please do not climb or walk on these fragile earthworks. • Stay on walks and trails to help prevent erosion. On the Gouedy Trail watch for uneven footing and exposed tree roots. • Beware of fire ants, poison ivy, ticks, and snakes. Watch where you put your hands and feet. • Metal detecting and digging for artifacts are prohibited. Do not collect, damage, or remove any plants, wildlife, rocks, or artifacts; all are protected by federal law. Report suspicious activity to a ranger. For firearms regulations check the park website. Emergencies: call 911.

Walking Tour of the Park

The one-mile roundtrip trail begins at the visitor center.

Spring Branch This stream, free-flowing in 1781, was the loyalists' source of water during the siege.

Island Ford Road You are parallel to a colonial road. Decades of travel cut the road to today's depth. The road crossed Saluda River at Island Ford, seven miles north.

Patriot Forces Arrive General Greene's Continental Army came along Island Ford Road on May 21, 1781.

Loyalist Fortifications Colonel Cruger bolstered Ninety Six by adding stockades, digging ditches around buildings, and building the Star Fort. Slaves did much of the work.

Siege Trenches Colonel Kosciuszko conducted siege operations by the manual: zigzag approach trenches (saps) connected three parallels. From the third parallel sappers dug a six-foot, vertical mine shaft. From its bottom they tunneled toward the Star Fort, planning to blast open the wall so troops could charge inside. The siege ended before the mine was finished. This was the only use of a mine in the American Revolution. Patriots built a 30-foot log rifle tower about 30 yards from the fort, so they could fire down on the loyalists. This 10-foot tower is a reconstruction.

The Attack Patriots began firing at noon on June 18. Opening the way, 50 patriots rushed into the fort's ditch. Loyalists killed 30. Greene halted the final attack.

Star Fort These earthen mounds are the remains of the Star Fort. During the siege, the walls rose 14 feet above the ditch. Loyalists added the protective traverse and dug a 25-foot well. They found no water, and enslaved workers brought water at night through the communication trench (covered way), four-to five-foot deep ditches that connected the Star Fort, village, and Stockade Fort.

Town of Ninety Six Three roads intersected here. Loyalist troops maintained British links with the Cherokee, trying to suppress the patriots. A two-story brick jail, built here in 1772, housed the jailer on the first floor, prisoners on the second. Another communication trench led to the Stockade Fort.

Stockade Fort Loyalists built a stockade around James Holmes' home to guard the town's water supply. On June 18 Colonel Lee captured the fort but held it only until Greene ended the attack.

Source: NPS Brochure (2013)

|

Establishment Ninety Six National Historic Site — August 19, 1976 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Bats of Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site, Cowpens National Battlefield, Guilford Courthouse National Military Park, Kings Mountain National Military Park, Ninety Six National Historic Site Final Report (Susan Loeb, July 2007)

Cumberland Piedmont Network Ozone and Foliar Injury Report — Kings Mountain NMP, Mammoth Cave NP and Ninety Six NHS: Annual Report 2013 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/CUPN/NRR—2015/1044 (Johnathan Jernigan, Bobby C. Carson and Teresa Leibfreid, October 2015)

Foundation Document, Ninety Six National Historic Site, South Carolina (October 2014)

Foundation Document Overview, Ninety Six National Historic Site, South Carolina (October 2014)

Junior Ranger Activity Booklet, Ninety Six National Historic Site (2013; for reference purposes only)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Old Ninety Six and Star Fort (Jason L. Cox and James W. Fant, undated)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment for Ninety Six National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NISI/NRR-2012/523 (Luke Worsham, Gary Sundin, Nathan P. Nibbelink, Michael T. Mengak and Gary Grossman, May 2012)

Ninety Six: A Historical Narrative, Historic Resource Study and Historic Structure Report (Jerome A. Greene, 1979, 1998 Reprint)

Research List, Ninety Six National Historic Site (Date Unknown)

Terrestrial and Airborne LiDAR Digital Documentation of Kosciuszko Mine, Ninety Six National Historic Site Digital Heritage and Humanities Collections Faculty and Staff Publications 10 (Lori Collins, Travis Doering and Jorge Gonzalez, 2015)

The Administrative History of Ninety Six National Historic Site (Karen G. Rehm, March 5, 1988)

Victory in the South: An Appraisal of General Greene's Strategy in the Carolinas (George W. Kyte, extract from The North Carolina Historical Review, Vol. XXXVII No. 3, July 1960)

nisi/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025