|

North Cascades

Ethnography of The North Cascades |

|

CHELAN

| DATA BASE |

Consistent with the procedure adopted in the preceding chapters, the summary of the traditional life patterns of the Chelan presented in the following pages represents a merging of the available ethnographic and ethnohistorical data. Unfortunately both sets are singularly meager, requiring a special fall-back and not very satisfactory descriptive procedure that must be explained.

The ethnographic information for the Chelan is essentially limited to casual remarks in ethnographic studies of nearby tribes. Fortunately, however, they were one tribe in a small cluster of regional groups that possessed quite similar life patterns: the Chelan, the Methow of the Methow Valley immediately upstream, and the Entiat and Wenatchi in their own valley systems below on the Columbia (Figure 4-1). Accordingly, in theory it should be possible with caution to extrapolate from the traditional life habits of the last three groups to those of the Chelan. As a practical matter, however, this is possible to only a limited degree, for the Methow and Entiat are ethnographically as poorly described as the Chelan. The Wenatchi, in contrast, are measurely better known, thanks largely to the single study by Ray (1942). The best that can be done is to make maximum use of what little Chelan information is available, extending it by reference to relevant Wenatchi data. Because the Chelan data are so scanty and that for the Wenatchi so much fuller, the pages that follow often have the appearance of a Wenatchi study with occasional references to the Chelan, expanding upon, confirming, or altering the Wenatchi ethnographic facts to the explicit Chelan situation.

Figure 4-1. Approximate traditional territorial boundaries of Chelan, Methow,

Entiat, Wenatchi, and Columbia. The Sinkaietk are the Southern Okanagan.

(After Spier 1936:42-43, modified by addition of Entiat, elimination of

Sinkaqai'ius as a tribal entity, and redesignation of Middle Columbia as

Columbia.)

This "altering" aspect calls for further comment. While the Chelan and Wenatchi evidently shared many basic cultural traits (Ray 1939:145-149; Teit 1928), they are either known or can be reasonably presumed to have differed in at least some segments of their lifeways. In the first place, no two tribal groups in the Plateau, however close geographically, followed precisely the same constellations of cultural patterns, just as every group had its own speech peculiarities. These differences in cultural behavior were fostered by a mixture of circumstances of varying importance: the influence of different sets of past leaders and community pattern-setters, contacts with a somewhat different groups of tribes, and other differences in their histories. But a factor of generally greater importance was the special features of the ecological niches to which the culture of the group was adapted. In the case of the Chelan and Wenatchi the two tribes occupied rather difference bioenvironments. That of the Chelan was a unique riverine-lacustrine and intensely mountainous one: while occupying a short stretch of the Columbia Valley, they were essentially a lake people, maintaining most of their camps and winter villages on the shores of Lake Chelan and exploiting in particular the small streams and timbered mountain slopes draining into the lake (Smith 1983). The effective bioenvironment of the Wenatchi, in contrast, was largely a riverine one, their mountains playing a lesser role in their life: the tribe lived on the banks of the Columbia and even more importantly along the Wenatchee River and its major tributaries and made great use of these stream resources, including hordes of salmon in season. To the extent possible, this study makes a particular point of identifying the cultural consequences of these environmental differences.

The Columbia "tribe" (the "Moses Columbia" of the latter part of the nineteenth century) on the eastern side of the Columbia River are sometimes linked, as noted below, with the Chelan, Methow, Entiat, and Wenatchi into a "Middle Columbia (Salish) group." After the Wenatchi, the Columbia are ethnographically the best known of this larger cluster. Yet in this present report, these Columbia data are not widely referred to, since, in spite of a deeply rooted life-mode similarity, their culture rested on a third ecological base, one including a Columbia Valley segment and a major part of the dry Columbia Basin with its steppe and shrub-steppe vegetation (Franklin and Dyrness 1973:6, 45). Further, their lifeways in posthorse times tilted toward those of the bison-hunting Sahaptian neighbors to the south. The Columbia cultural data are, therefore, only marginally useful in the Chelan context.

In the interests of clarity, an effort is made to assign data explicitly to the Chelan or Wenatchi (or occasionally to some other group). Where not so identified to avoid tiresome repetition, the information is to be understood as Wenatchi-specific.

The greater part of the limited ethnographic data for the Wenatchi is to be found in Ray's (1942) culture element survey. This provides detailed information concerning many segments of traditional Wenatchi lifeways, though this is less rich than for other groups investigated at later times in his field research period. There is, however, a problem in the use of these data in terms of this present study; because they are recorded in an individual item-list fashion, the functional relationships between items and especially between item clusters are neither invariably apparent nor always reconstructable with assurance. Thus weir and fish trap elements are cataloged separately, rendering it difficult to sense how the weirs and traps were combined in organic complexes. Specific instances of this kind are noted in the ethnographic summary that follows.

A second difficulty lies in the interpretation of Ray's (1942:104) symbol "( )," which he explains as indicating that "informant qualified answer by terms such as 'sometimes' or 'a few.'" But in his tables he uses both (+) and (-) without defining the difference between the two. Perhaps (-) signifies "sometimes absent," implying that the trait was generally present, and the opposite for (+). This interpretation seems improbable to me, but I really do not know. Accordingly, I have opted for translating the two identically to indicate 'sometimes,' 'occasionally,' or 'a few.' Thus: "Traps: withes of fir (+)" (Ray 1942:107) might be reported in this study as "traps were sometimes made of fir withes" or "a few traps were fashioned of fir withes." And Ray's (1942:111) "eel hook (-) might here appear as "the Wenatchi had a few eel hooks" or "they occasionally used hooks for eels."

A third point in regard to my free use of Ray's survey data: in most instances I pass over his negative data entries. Plateau informants even in the 1930s were unaware of the full richness of their traditional culture. This was especially true, of course, of those cultural traits that disappeared soon after first White contact. But their native lifeways were, in general, characterized by alternative ways of achieving the same objective. Surely this was partly a response to a typically broad range of bioenvironments within the country of a single tribe. But it appears also to have been partly related to their basically loosely structured society in which individual choice and experimentation were not only permitted but fostered. As a consequence, no informant, however knowledgeable, could be expected to be well acquainted with the variant behavior patterns followed by only a few tribal members or that had been practiced under peculiar, infrequent conditions or in atypical geographic sectors of the group's territory. Negative evidence is, in short, somewhat tainted by these circumstances.

Fourth, the Wenatchi were the first group surveyed by Ray, using a list of traits that was very incomplete in comparison with the expanded element roster that guided his later inquiries among other tribes. Accordingly, the failure of a cultural trait to be mentioned in the following survey as an aspect of Wenatchi culture cannot be interpreted as necessarily indicating its absence among the group.

Finally, Ray's Wenatchi data have been subjected to a careful cross-checking process. This is necessary since traits are sometimes mentioned in one context but not elsewhere where they might be expected to appear. One illustration: bark baskets are noted as Wenatchi water carriers in the "Utensils and Dishes" section, but the entire "bark basket" section is left blank for the Wenatchi, evidently indicating only that no data were gathered as an inquiry unit concerning bark containers (Ray 1942:140, 160-161). Still, I have doubtless overlooked some dispersed data of this kind.

Not included in this Chelan section are data reported by Teit (1928) for his Middle Columbia Salish cluster except where the Chelan are mentioned specifically or inferentially. It is often impossible to determine -- at least as presented under Boas' editorship -- whether tribally unassigned data apply to all the Middle Columbia peoples -- Chelan, Methow, Entiat, Wenatchi, and Columbia -- or to some limited segment of this large cluster. When "Wenatchi" are identified specifically with data, it is uncertain whether this information describes the situation for the Wenatchi tribe alone or for the entire "Wenatchi" group -- the Chelan, Methow, Entiat, and Wenatchi proper. Incidentally, in gathering these Middle Columbia ethnographic facts, Teit (1928:89) apparently relied on Columbia and Wenatchi informants, having had none from the Chelan and Methow. Evidently Ray's "Wenatchi" data, on the other hand, relate only to the Wenatchi people and so possess in this present context the particular merit of tribal specificity.

Early historical documents relating specifically to the Chelan area are likewise not numerous. To this point, no more than 19 dating to the 1811-1850 period have been identified as concerned with the Columbia Valley segment of the aboriginal territory of the Chelan; only one is known for the Lake Chelan area.

The Columbia River data may be considered first. It may seem surprising that there are so few accounts of travels through the area in this initial 40 year period, particularly in view of the very considerable annual movement of Euroamerican traders up and down this major river highway and, later in the period, the journeys of missionaries and casual travelers. Unfortunately, however, most of these travelers kept no record of their goings and comings: many were men who were bold adventurers and fine canoemen but who possessed little education. Others apparently chronicled their adventures only to have them lost or still curated as archives. Of those riverfarers whose accounts have made their way into print, some report on only one or two of their several journeys, or reduce their daily travels to only the barest essentials, or recount their journeys in narrative form too deficient in specifics to be helpful. And virtually all slight the Chelan and middle Columbia segment of their river travel. How can this patent disinterest in this particular region be explained?

To understand this circumstance, it is necessary first to review briefly those segments of these published, pre-1850 travel accounts that concern the Columbia Valley in Chelan territory. Whatever ethnographic data are provided are not included here but are integrated into the culture-descriptive sections to which attention is soon turned.

- In early July, 1811, David Thompson (1914:52, 1962:344-345; Smith 1983:25-35), descending the Columbia from Kettle Falls, evidently saw no Indians in Chelan country. As the first White man to traverse the river from Kettle Falls to the Snake River confluence, he had "as usual" put ashore when he had observed villages of the Sanpoil, Nespelem, and Methow and as he later did at the Columbia village at Rock Island. Both as a matter of trading strategy and to insure his safety when he expected later to ascend the river slowly against its strong current, placing him at a disadvantage in case of native hostilities, he stopped wherever he found an Indian camp to explain the purpose of his journey of exploration and to smoke with its occupants (Glover 1962:344). While he is entirely silent on Indians in this Chelan sector, the fact that he passes the area without pause seems proof enough, in light of his expressed and observed policy, that he noticed no native camps in this distance. These data are of special interest not only because they report the initial Euroamerican journey through the Chelan sector of the Columbia, but also because they have implications for an understanding of salmon fishing among the Chelan, a matter discussed below in the fishing context.

- In late August, 1811, Alexander Ross (1966:103, 139-142, 289-290; Smith 1983:43-51) canoed up the Columbia from Astoria on his first upriver journey. Passing through Chelan territory, he observed "a small but rapid stream, called by the natives Tsill-ane, which descended over the rocks in white broken sheets." Indeed, he was even informed by the Indians that "it took its rise in a lake not far distant," the first reference to Chelan River and Lake in the historical literature. A short distance farther up the Columbia he met "some Indians," put ashore, and encamped for the remainder of the day and following night. Precisely where this encounter took place is uncertain. For several reasons, however, the location seems to have been about 6.5 miles upstream from the Chelan confluence (Smith 1983:49-51) and at any rate within Chelan territory. Ross' few observations concerning these "very friendly, communicative, and intelligent" people -- surely Chelan and the first Chelan seen by Whites in their own country -- are noted in the following culture-descriptive sections.

- In April, 1814, Alexander Ross (1956:21-31; Smith 1983:51-59) again ascended the Columbia River, on this occasion with a flotilla of watercraft. In his travel record no mention is made of the Chelan or their country as he moved up the river. Nor is attention directed to either when, a few days later, he left the area of the Okanogan confluence and rode horseback down the Columbia through the Chelan sector to the Kittitas Valley in search of horses and then, with purchased animals, returned along the river trail to the Okanogan Valley.

- Gabriel Franchere (1854:276-280; Smith 1983:59-63), a member of Alexander Ross' large boat brigade of April, 1814, makes no mention of seeing Indians along the riverside between Priest Rapids and Kettle Falls.

- By his own account, Ross Cox (1957:5, 218-227, 256; Smith 1983:63-66 made several journeys up and down the Columbia River between the mouth of the Snake and the confluence of the Okanogan. For most of these watercraft passages, we are favored with no information. In November of 1815, he relates however, the frail bark canoes and cedar-plank boats of his party were halted by river ice, as they moved up the Columbia. This point of blockage was certainly below the Chelan region, at Rock Island I believe on the fragmentary evidence provided. In mid-February, 1816, after a hard winter's encampment and following the breakup of the river ice, Cox and most of his group continued their water journey upstream to the Okanogan, mentioning no Indian sightings en route.

- In April, 1817, Ross Cox (1957:268, 271-272; Smith 1983:66-71) undertook his final journey up the Columbia from Fort George, on this occasion in a party traveling in two barges and nine canoes. Again, unfortunately, he mentions no Indians as he traversed the distance from Priest Rapids to "Fort Oakinagan."

- In late June and early July, 1817, Alexander Ross (1956:94-95;

Smith 1983:71-73), traveling in a boat of the North West Company

brigade, made his way through Chelan country. While he mentions no

Indians specifically for this section of the Columbia, he writes on

leaving Priest Rapids:

Though some slight room exists for interpreting these comments regarding band numbers as applying only to the troublesome groups downriver from Priest Rapids, it seems, coming at the close of his brief journey account as it does, to apply to his entire canoe experience from Fort George to the Okanogan. This would include the segment of the Columbia River from Priest Rapids to the Okanogan confluence and so pre sumably to the Chelan territory. Yet whether any of these "bands" were in fact at the riverside within Chelan boundaries remains problematical. In any event, these statements are of considerable general importance in revealing, through the eyes of a competent and experienced observer, the extent to which Indians varied greatly in their numbers along the river from year to year and season to season, but more significantly at the same season from year to year. And, furthermore, that this variation occurred during the first decade of Euroamerican contact.Henceforth we travelled among those more friendly [Indians] as we advanced towards the north. The innumerable bands of Indians assembled along the communication this year rendered an uncommon degree of watchfulness necessary, and more particularly as our sole dependence lay on them for our daily subsistence. I have passed and repassed many times but never saw so many Indians in one season along the communication; . . .

On arriving at Oakinacken . . . I set out immediately for my winter quarters at the Shewhaps [Shuswap], . . .

- Early in November, 1824, George Simpson (1931:36-53) descended the Columbia from the Boat Encampment at the foot of the Rockies. Below the Okanogan he notes passing "a small River." That this can only have been the Chelan River I have elsewhere demonstrated (Smith 1983:73-75). Importantly, he states explicitly that he "Saw no Indians on the communication to Day," i.e., during the day when he passed through the Chelan territory. Were the three and perhaps as many as five Chelan winter villages reported ethnographically to have been located on the west bank of the Columbia not occupied that winter for some reason, for surely they should have been in their cold season settlements by November? Or were the dwellings, on the river terraces, subterranean pit structures with earth-covered roofings raised so little above the land surface as to be invisible from canoe level? If the latter were the case, why were there no ancillary, specialized structures to be seen -- e.g., platform caches and even summer salmon and plant food drying racks, for, according to Ray (see later section), three and possibly five Chelan sites on the Columbia supported warm season camps? Interesting and, it would appear, unanswerable questions.

- On April 3,1825, Simpson (1931:130-131; Smith 1983:74-75), returning up the Columbia from Fort George in a flotilla of four boats, moved through the Chelan area without comment of any sort.

- In 1826 David Douglas (1972:71, 75, 85, 122-124; Smith 1983:75-77) journeyed through the Chelan area on no less than three occasions: the first heading up the Columbia in late March and early April; the second moving downstream in June; and the third again descending the river in August. In all of these water passages he mentions only once seeing Indians, or evidences of them, between the Okanogan mouth and Priest Rapids: on his August trip at Rock Island well below the Chelan country. This appears odd and must, it would seem, reflect nothing more than Douglas' disinterest in the native peoples, save where he needed their services. Because the salmon were still running -- he observed in August an old man spearing these fish opposite Fort Okanagan -- he had excellent opportunities to view activities at various river fisheries and summer camp sites. This would have been especially the case at the Methow Rapids where he was compelled to take to his feet down the riverside while his Indian companions ran his canoe down the fast water, and again at the Wenatchee River confluence where he encamped over night; both of these localities are reported ethnographically to have been the site of summer camps. The point, to repeat, is that no mention by early river travelers of Indian villages or camps or of Indians laying in their store of salmon cannot be safely interpreted, failing some evidence to the contrary, as signifying the absence of native communities and activities in or along the river.

- On April 4 and 5, 1827, Edward Ermatinger (1912:70-78; Smith 1983:77-83), in the York Factory express boat, followed the Columbia through the Chelan homeland. On the evening of the 4th, after having traveled the distance from his night camp of the 3rd, pitched "5 miles above the Piscouhoose [Wenatchee] River," he made camp "a league above the Clear water Creek," i.e., Chelan River. The "league" of the fur personnel at the time seems to have been about seven miles, as Simpson's (1931:52; Smith 1983:73) journal of 1824 demonstrates. This suggests that Ermatinger and his party encamped at or very near where, on independent evidence, I suggest that Alexander Ross pitched his camp on July 27,1811 (see above). Alternatively, if the dictionary definition of the league "of English-speaking countries" as about three miles is assumed to have been that of Ermatinger, then his night's stopping locality would have been approximately where his traveling party paused to sleep on April 3,1828 (see 1828 item below). On April 5,1827, he arrived at Fort Okanagan. In his journal entries of neither the 4th nor the 5th is any mention made of sighting Indians.

- In October of 1827, Ermatinger (1912:110-112; Smith 1983:83-88) and his Hudson's Bay Company party coursed down the Columbia from the Boat Encampment to Fort Vancouver. Unfortunately, Ermatinger makes no reference to any Indians between the Okanogan and the White Bluffs area below Priest Rapids.

- On April 3, 1828, as a member of the Hudson's Bay Company express of two boats bound from Fort Vancouver to the Boat Encampment, Ermatinger (1912:112-118; Smith 1983:88-89) again passed through Chelan territory. The night of that day found the party camping "2 or 3 miles above Clear Water Creek [Chelan River]." The site of this encampment, if his mileage estimate is essentially accurate, would have been very near the town of Beebe, or perhaps slightly farther upriver. Once again there is no reference in Ermatinger's account to any sighting or encountering of Indians in the Chelan region during either this day or the 4th, when, after breaking camp, the travelers negotiated the northeastern corner of the Chelan country and moved on into the homeland of the Methow.

- In late May and early June, 1828, John Work (Lewis and Meyers 1920:106-107; Smith 1983:90), with a large brigade, journeyed by boat from Fort Colvile to Fort Vancouver. On May 28, the party, aided by a strong current and by being propelled with oars rather than with paddles, traveled the entire distance from the Okanogan confluence to just upstream from Priest Rapids. While Indians are mentioned at Priest Rapids, no sightings of natives between Okanogan and these rapids are recorded. As in the case of so many of these early accounts, Work's report of this journey is one of great terseness, with no room for what he would reasonably consider commonplace and irrelevant.

- On August 8,1828, John Work (Lewis and Meyers 1920:112-113; Smith 1983:92), as a member of a brigade with nine heavily laden boats, moved up the Columbia through the lower part of Chelan country, to camp that night "a little above Clear Water [Chelan] River." Here the flotilla was met by a man with horses from Okanagan. On the 9th, Work and a companion left the watercraft and rode through the northeastern sector of the Chelan area and on to the fort. Work, whose narrative of each day's events hardly exceeds a half-dozen lines, provides no information concerning the Indians of the Chelan and Methow regions, though he reports on August 6, when the party passed Rock Island, that there were "Very few Indians in the River, and Salmon very scarce" and that in the Wenatchee sector his group "Traded some Salmon from the Indians." His informative salmon and salmon fishing remarks, coupled with the Chelan focus on the Lake Chelan subsistence area (discussed below), suggest that the few Chelan, in fact, may have been on the Columbia when Work passed, but this is, of course, in a measure conjecture.

- On June 2,1836, Samuel Parker (1842:300-307; Smith 1983:92-93) left Fort Okanagan in a bateau with two Indians and two French voyageurs. Guided by his companions and driven by the river "in full freshet," he put behind him on this first day the entire distance to a point a few miles above Priest Rapids. He fails to mention Indians in his account of this day when he rushed through the Chelan country. However, he observes on June 3, during which he traveled through Priest Rapids and all the way to Walla Walla, that salmon were "ascending the river in great numbers, and groups of Indians are scattered along pursuing the employment of catching them." And later, writing retrospectively, he contrasts the life style of the Middle Columbia Salish -- Chelan, Methow, Entiat, Wenatchi, and Columbia -- with that of the Sahaptian peoples farther down the Columbia River, the gist of which is remarked upon in a later section of this present report.

- On August 20,1841, George Simpson (1847 1:141,153-162; Smith 1983:93-94) embarked from Kettle Falls in a flat-bottomed bateau, propelled by six oars, high water, and a strong current. Driving very hard as was his headlong style, he passed through the Chelan area on his second day of travel, making no reference to Indians until he reached his evening camp at Rock Island.

So much for the early historical documents pertaining to the Chelan segment of the Columbia River. Plainly they furnish precious little information regarding the Chelan and their homeland in the 1811-1850 period. Two of these early travelers (David Thompson in July, 1811, and George Simpson in November, 1824) either explicitly report no Indian sightings along this Chelan River stretch or present data making this a safe deduction. Only one traveler (Alexander Ross in August, 1811) mentions observing and camping with Indians on the riverside in Chelan country. On three other occasions parties journeying on the river (those of Edward Ermatinger in April of 1827 and of 1828, and John Work in August, 1828) encamped for the night on the river bank in Chelan territory yet fail to note Indian sightings within Chelan borders. In the remainder of the water passings identified above -- 13 out of the total of 19 -- the travelers moved through the Chelan homeland without pitching camp within the Chelan boundaries and without so much as a word concerning Indians. These last 16 river boatmen whose travels have been brought to print may have observed no signs of residential units or of Indians themselves, or, seeing them, may have simply neglected to mention the fact. This question deserves some attention for what it reveals concerning both these early Euroamerican river users and the Chelan and their traditional life style.

Why might it be expected that these travelers along the water highway would have seen Chelan or at least their cultural marks in passing through their country? For several reasons, among which the following appear the most persuasive:

- The river journeys summarized above were distributed through nine months of the year: only September and, not surprisingly considering the cold season conditions of the river and the severe winter traveling problems in general, December and January saw none.

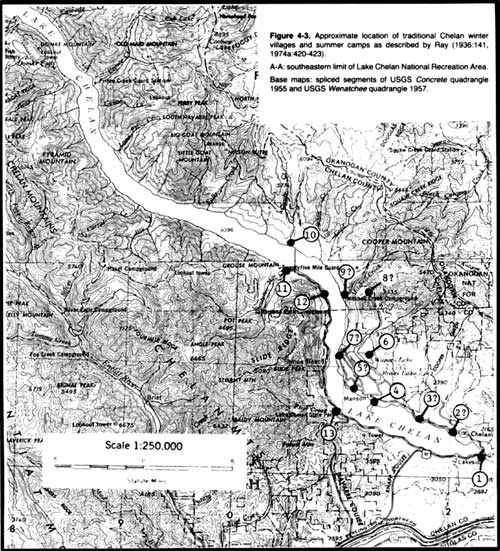

- According to the ethnographic evidence (Ray 1936:141; 1974a:419, 423), the Chelan maintained both winter villages and warmer month camps along the Columbia riverside. Four of the documented 19 early travels were made in the period from late October through March. During this season all Chelan villages on the river might reasonably be expected to have been occupied. Warmer weather river journeys were more frequent, 15 from April through September: specifically April (5), May (2), June (2), July (2), and August (4). During at least some of this open time-span, residents should have been in or near their "summer" camps (Ray 1936:141; 1974a:419-423) along the riverbanks. At least one of these summer settlements was a fishing -- presumably salmon -- camp (Ray 1974a:423). In the midst of the salmon time, some fishermen from this camp and other river bank camps should have been observed at the tribal fisheries, perhaps at the two rapids below the Chelan confluence termed by Symons (1882:maps 14,15) Downing's Rapids and Bar Rapids and even at his three "ripples." Surely, especially in view of the important Chelan summer food resource region around Lake Chelan, open season camps would not have been maintained on the Columbia River unless salmon fishing and probably plant collecting afforded serious subsistence opportunities. Further, the people of these Columbia River winter and summer communities must have engaged year-round in other subsistence tasks and technological pursuits along the river terraces and facing hillsides: e.g., hunting and plant gathering in season, food drying and storage, mat and basket making, hide tanning.

- As reported above, one trader (Ross in August, 1814) rode on horseback round trip along the river trail through the entire Chelan territory, and one (Work in May, 1828) negotiated the northern end of the river path out of Chelan country aboard a horse. While stream voyagers might have been fully occupied in forcing as much water behind their craft as possible -- as was certainly sometimes the case -- or in otherwise managing their canoe or boat, thus missing Indians on the river and Indian encampments on the stream bank, these two land travelers must have had an unparalleled opportunity for seeing Chelan at or in the vicinity of their summer river camps. Yet neither so much as mentions catching sight of an Indian or any Indian sign while within Chelan borders.

On closer examination, however, the infrequency of historical references to Indians in the Chelan River sector becomes rather more comprehensible.

- With few exceptions, travelers were intent on making as expeditious a traverse as possible through the Chelan homeland and, in fact, through the entire Columbia Basin river reach. The nearest trading posts were at the Okanogan River mouth above and the Walla Walla confluence below, the two posts between which the watercraft were generally moving. The Chelan region offered nothing of commanding interest in terms either of native groups or of commerce: the Chelan were simply too culturally unspectacular and too poor in traders' terms to warrant breaking a journey.

- The Chelan were wholly inoffensive. Between the Okanogan and Priest Rapids only a single falls, that at Rock Island well downstream from the Chelan southern boundary, generally required landing and portaging, though under certain water conditions a few rapids caused small problems, including a bit of fast water just below the Chelan River confluence. When navigational difficulties occurred and moving impedimenta for a short distance along the river bank became a necessity, the Chelan, like their immediate neighbors, exhibited none of the annoying and often dangerous aggressive tendencies common among the native groups of the lower Columbia. There was no cause for a traveler in Chelan country to note Indian presence on such occasions.

- Relatively few Chelan maintained their residence either in winter or in summer along the Columbia. On ethnographic evidence (Ray 1936:141; 1974a:419, 423), only six residential sites were located on the riverside. For two of these the season of occupancy is undescribed; of the remaining four, one appears to have been used only in winter, one in summer, and the other two in both seasons. This compares with eight winter villages around Lake Chelan and 11 summer month camps (Smith 1983:264). Clearly the Chelan population was concentrated in the lake section (see demography unit below).

- Even the April clustering of journeys may help to explain the infrequent references to Indians on the river. Too early to begin activities at the Columbia River fisheries, the people were almost certainly scattered out on the early spring collecting and hunting grounds, following the seasonal activity pattern of the Sanpoil (Ray 1932:27) and Southern Okanagan (Spier 1938:11).

- The Chelan area attracted no early missionary interest of significance. Perhaps the tribe was first exposed to formal Christianity in 1838 when the Catholic priests Blanchet and Demers journeyed down the Columbia River and therefore necessarily passed through Chelan territory. From time to time while en route they stopped, as they did also in later years, to instruct briefly and baptize native groups residing on the river banks (Byrd in Durham 1972:11 fn. 20). Whether the Chelan received these ministries I do not know. At any rate, nothing like the early, extensive, and informative records of De Smet, Spalding, the Walkers, and others for the eastern Plateau exist for the Chelan -- not even for the other Middle Columbia Salishan groups. Perhaps as early as 1858, however, Catholic services were held at Wapato Point, a bit of land extending out into Lake Chelan near Manson (Byrd in Durham 1972:9 fn. 19, 11 fn. 20), but information concerning these religious contacts seems also to be wanting.

In sum, it may be concluded from these data, supported by additional information presented later, that:

(a) Early travelers on the Columbia in the Chelan homeland normally had no incentive or occasion to come ashore except to serve their own immediate purposes, as to take meals and encamp for the night;

(b) White boatmen traveling the river should have observed from their passing craft, even though they were moving in haste, some Indian villages and camps on the stream terraces and some Indians at their tasks;

(c) Travelers who kept journals evidently considered their sightings of Indians within the Chelan borders too trivial to record;

(d) Sightings were probably fewer than might be supposed because the Chelan population along the Columbia was not large, the tribal center being rather in the Lake Chelan region; and

(e) Sightings were less frequent than might be expected because salmon fishing was for the Chelan a less important Columbia River activity than it was for other nearby river tribes and because, as Teit (1928:114) observes for the Chelan and the Middle Columbia Salishan groups in general: "Much of the summer and fall season was spent on the higher grounds, hunting, root-digging, and berrying."

It is unclear, in short, how best to balance out haste and disinterest on the part of the early passersby on the one hand and, on the other, the relevant aspects of Chelan population distribution, seasonal movements, and other cultural factors as contributors to the general failure of the river travelers to note Chelan presence along the Columbia in the 1811-1850 time span.

To place these Chelan data in perspective it is instructive to view them within a slightly broader geographical context. In the records of only two of the 19 river journeys precised above -- those of Thompson and Ross, both in 1811 -- are the Methow, above the Chelan, mentioned and in not one is the existence of Indians in the Entiat country, immediately downriver from the Chelan, attested to. Obviously, the Chelan were no more slighted by these early stream travelers than were their adjacent Salishan neighbors. Evidently the same complex of circumstances that was responsible for the 1811-1850 inattention to the Chelan operated in the case of all three of these neighboring, culturally resemblant tribelets.

For the Lake Chelan and Stehekin segment of Chelan traditional territory, I have uncovered only a single traveler's account for the entire 1800-1850 time span.

- In late July and August, 1814, Alexander Ross (1956:36-42)

attempted to cross the Cascades to the coast, traveling on foot

with an Indian guide and two other Indian companions and following an

old Indian traders' trail but by his time very obscure. He went down the

Columbia to the Methow mouth and then ascended the Methow Valley. After a

short distance, however, he was compelled to leave the river. From this

point on, his route is difficult to follow, though he provides

compass readings and mileage estimates. While not all who have attempted

to define his route agree on its precise plotting, most bring him

through Twisp Pass into the Upper Stehekin drainage well above Lake Chelan,

to which he makes no reference though he learned of this body of water

in 1811 from Indian informants (see above). From this northwestern

corner of Chelan country, within the Park borders, most then take him

over Cascade Pass and down the North Fork of the Cascade River in

Skagit Indian territory to a point identified by Spaulding (in Ross 1956:41

fn. 25) as "just below the forks of the Cascade River" before abandoning

his attempt and returning to his Okanogan post. But if he, in fact,

crossed the Methow Mountains by way of Twisp Pass, he may well not have

gone on to Cascade Pass but, reaching Bridge Creek, may have ascended

that stream to Rainy Pass and proceeded down the west side of the divide

to the headwaters of Granite Creek. Beckey (1981:280 fn. 24),

whose firsthand knowledge of the North Cascades in general seems

unparalleled, favors this Rainy Pass trail or, if Ross moved up the Early

Winters Valley from the Methow River rather than the lower-down Twisp

Valley, then a mountain saddle farther north than Rainy, which I take to

mean Methow Pass as a possibility.

Evidently during his entire journey, both out and back, Ross encountered no Indians. If his turn-about point was on the Cascade River as noted above, only a few more miles would have brought him to Skagit summer settlements.

So far as known, this was the earliest Euroamerican penetration into the Stehekin and upper Cascades River regions, assuming that his path was in fact via this route.

In the years that followed, a few early fur trappers and voyageurs may have traveled into the Lake Chelan area and trapped around it. Remains of old cabins -- described by early settlers as Hudson's Bay Company trapping shelters -- existed near the mouth of Flat Creek, about 13 miles up the Stehekin Valley, and at Twentyfive Mile Creek, on the southwest side of the lake, approximately 17.5 canoe miles uplake from its southern end (see Byrd in Durham 1972:17 fn. 31). But for these early lakeside activities, I have as yet seen no solid documentation.

Although in the early 1850s George McClellan of the Stevens survey expedition investigated -- and recommended against -- the Methow Valley as a possible cross-Cascades railroad route, it appears that no field examination was made of the Lake Chelan and Stehekin Valley area to measure its potential. It was discovered that the short stretch up the Chelan River to the lake was too rugged, crooked, and canyon-like and the lake side was "shut in by high mountains, which ... [left] no passage along its margin" (McClellan in Stevens 1855:196; Duncan in Stevens 1855:213). This was more than sufficient to demonstrate the impracticality of this route.

A few years later, however, "a large group of prospectors ... [traveled the lake] as a short-cut from the Snake River to the Fraser River gold rush in 1857-1858" (Byrd in Durham 1972:17 fn. 31). This appears to be the first unquestioned use of the lake by Whites, though only as travelers en route over the Cascades.

The first historically documented exploration of the lake area -- as opposed to casual travel across its waters -- appears to have been that of D. C. Linsley and John A. Tennant in mid-July, 1870: they went the length of the lake and undertook railroad surveys in the river system at its head (Beckey 1981:215). Unfortunately, no record of this reconnaissance is in my hands.

In 1879-1880 Col. Merriam and Thomas Symons visited the lake in their search for a suitable site for a military post and, while there, investigated the lower 24 miles of the lake in a dugout canoe with two Chelan Indians from their village on the Columbia about one mile above the Chelan River mouth. Within a year or so Merriam canoed to the upper end of the lake. As a result of these Merriam-Symons surveys, Camp Chelan was established in 1880 at the southern tip of the lake, where, however, it remained for only a few months (Symons 1882:39-40, 123; Byrd in Durham 1972:12 fn. 22, 17 fn. 32). To my knowledge there is no published record of these explorations save for the few lines in Symons' account. In it, however, there is nothing to suggest a contemporary Chelan presence in the lake area, and it seems probable, because of Symons' obviously warm relationship with the Columbia River Chelan, that he would have reported Indians on or around the lake had he observed them.

Other early but post-1876 documents relating to the history and natural history of the lake and Stehekin sectors may be found reproduced in Stone's (1983) compilation, from which, unfortunately, I have not had time to extract data relevant to this report.

| INTRODUCTION |

Ethnonymy

The Chelan as a group have been treated in the historical and ethnographic literature in three ways:

(a) They have been regarded as a distinct tribe with their own designation, reflecting the view of the Chelan themselves. Thus:

- Writing of the Chelan River and the Indians whom he encountered on August 27, 1811, just up the Columbia from the mouth of the Chelan, Alexander Ross (1966:139-140, 290), the first White known to have seen these people, called both the Indians and their river the "Tsill-ane."

- In his journal of his voyage down the Columbia River in 1824 and return upstream in 1825, George Simpson (1931:168) lists the "Tsillani" among "the different Tribes inhabiting the Banks of the Columbia from the Cascades Portage to the Rocky Mountains," a roster obviously secured from local Hudson's Bay Company records.

- In recent years the ethnographers Ray (1936:103, 119, 122, 141-142, 1974a:419-423) and Spier (1936:15, 42-43) have regarded them as a separate tribe under the name "Chelan".

This view of the Chelan mirrors their sense of themselves, as a distinct people whom they term the tcitla'n (Ray 1936:122). Obviously derived from this term are the designations in the preceding roster. The separateness of the Chelan as a cultural and population entity was recognized by other nearby groups. The Klikitat, for example, called them the tcEla'lpam (Teit 1928:91), -pam being one of the Sahaptin suffixes denoting "people of" (Jacobs 1931:220).

(b) They have been considered a band or very small tribe distinct in a sense but properly comprising with other nearby groups on the west side of the Columbia a single large tribal unit. Thus:

- Ross' (1966:289-290) separation of the Chelan into a distinct tribe has already been noted under (a) above. It should be observed, however, that he considers the Chelan but one "tribe" of a dozen that comprised the Oakinacken "nation," three of these others being the Piss-cows (Wenatchi), Inti-etook (Entiat), and Battle-le-mule-emauch or Meat-who (Methow).

- Whether based on his own field research or on that of his assistant W. E. Myers in 1907-1909 is uncertain, but Curtis (1911 7:xii, 65, 69) speaks of the "Sfsilamuh, at the mouth of the Tsilan, or Lake Chelan, as one of the small groups of tribes or bands that are sometimes lumped with the Methow as "Methow" and more often included with the Entiat and Wenatchi as "Wenatchee."

- Teit (1928:89, 90, 91, 93, 95) views the Chelan (Tsele'n, .stcele'nex) as a band or tribelet -- like the Methow -- of the large Wenatchi tribe, though differing slightly in dialect from the Methow and Wenatchi proper.

(c) They have been described as a small component of a single large tribe that aboriginally occupied territory between the middle Columbia River and the Cascades. The Chelan -- like other member groups -- are not said to have possessed separate linguistic, cultural, or political identities at even the band level. In light of the conviction of the Chelan themselves that they comprised a distinct cultural unit ([a] above), this treatment is surely only the consequence of seeing the tribal units of the area in terms of supratribal cultural and linguistic entities and makes no pretense of concerning itself with population groupings at a more local level and according to the Indians' own view of functional social groupings.

- Gibbs (1855a:412) includes within his "Pisquouse" tribe the Indians of the Chelan area as well as those of the Methow, Entiat, and Wenatchee drainages.

- Winans (1871:487, 489) writes only of the "Mithouies," into which he collapses, without naming them, the Methow, Chelan, and Entiat.

- Presumably following Winans, Mooney (1896:734, 736, plate 88) recognizes only a "Mitaui" tribe, which includes, as is evident from the territory it is said to have controlled, the Chelan as well as the Methow and Entiat.

- Hodge (1912:850), perhaps taking his lead from Winans and Mooney, places the Chelan -- without naming them -- within the Methow, whom he defines as "as Salishan tribe ... formerly living about the Methow r. and Chelan lake."

- Evidently using Teit's field data though not in a very perceptive manner, Boas (1927:tribal distribution map) merges the Chelan with the Entiat and Wenatchi -- and perhaps with the Methow also -- as a single grouping under a "Wenatchi" designation.

A more extented discussion of the above data has been developed by Smith (1983:153-161).

It is of some historical interest that both the earliest references to the Chelan and the most recent ethnographic considerations of them have generally recognized the Chelan and their neighbors as local -- especially river basin -- population entities as did the Indians themselves. In contrast, the references of the second half of the nineteenth century and early 1900s tend to merge the Chelan with other nearby Salishan speakers, seeing cultural and linguistic similarities among them and extending the term for one large component of the cluster to designate the entire group.

This inclination to collapse the Chelan (as also the Entiat) within the Methow above them on the Columbia River or with the Wenatchi downriver reflects the erroneous notion that the Chelan were in traditional times a small and insignificant people, as were the Entiat between them and the Wenatchi certainly were. This concept of the Chelan may have been partly a consequence of the fact already commented upon that the tribe was primarily a Lake Chelan group with, according to Ray (1936:141-142; 1974a:419-423), a few summer camps and winter villages, all normally small, on the Columbia River (Smith 1983:278-281). As a result, most of the Chelan population could not have been seen by the early river travelers, and those who were observed on the riverside were doubtless engaged in pursuits very like those of their neighbors below and above them on the Columbia, in a sense atypical for the Chelan tribe as a whole.

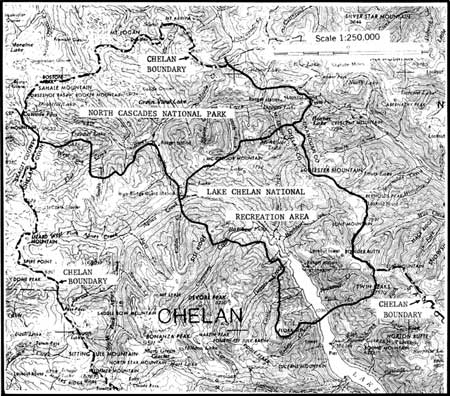

Figure 4-2. Limits of traditional Chelan territory in relation to boundaries

of Lake Chelan National Recreation Area and southeast corner of North Cascades

National Park. The lower part of the lake and the short Columbia River sector

within Chelan country lie beyond the borders of the Park Complex and are not

included in this map. USGS Concrete quadrangle 1955.

Tribal Territory

The traditional territory of the Chelan included a short stretch of the Columbia River on both sides of the mouth of Chelan River, Lake Chelan, and, it must be presumed, the total watershed of the lake. The aboriginal village locational data of Ray (1936:141-142; 1974a:420-423) for the Chelan and for their Methow neighbors on the north and the Entiat on the south define with some precision the extent of the Columbia west bank held by the Chelan. Specifically, their territory extended from the mouth of Antoine Creek, or slightly up the Columbia from that point, downstream past the entrance of Chelan River and as far south as just below the mouth of Navarre Coulee (Smith 1983:166-168). The extent to which the tribe made use of the east side of the Columbia River is much less clear. Still, it is reported (Ray 1974a:423) that they collected roots in the Badger Mountain region, so it is safe to assume that to some degree they exploited the subsistence resources of the east side of the Columbia opposite their west bank country.

The limits of traditional Chelan country west of the Columbia plainly included the entire Lake Chelan area. Consistent with the general tribal land utilization pattern in this section of the Plateau, it may be reasonably concluded that the Chelan claimed as their own all streams -- none, however, of any magnitude -- that drained into Lake Chelan from the Sawtooth Ridge watershed on the northeast and the peaks of the Chelan Mountains on the southwest. On the northwest in aboriginal and early contact times their tribal lands embraced the entire Stehekin River drainage up to the crest of the Cascade Mountains. In terms of the special interests of this present report, these data mean that the entire Lake Chelan National Recreation Area and all of the adjacent southeast corner of the North Cascades National Park fall within the country claimed in traditional times by the Chelan (Figure 4-2).

Cultural Affiliation

As two views of the Chelan in ethnic identify terms ([b] and [c] in above) suggest, the group has been considered by some ethnographers as comprising, in various combinations, a single cultural entity with the Methow upstream and the Entiat and Wenatchi downriver. Thus Teit (1928:89:93) regards these four groups as comprising a single "tribe" essentially uniform in life style, to which he applies, by extension, the term "Wenatchi." He further links this enlarged "Wenatchi tribe" culturally with the Columbia of the western Columbia Basin and adjacent Columbia River Valley, designating this larger, two-component entity the "Middle Columbia Salish."

Even those like Ray (1936:103, 108; 1939:149; 1974a:419-435) who regard the Chelan as a distinct tribal group ([a] above), reflecting the perspective of the Chelan themselves, assume a basic conformity in the traditional lifeways of the Chelan and Wenatchi as well as of the Methow and Entiat. Thus all four groups, though the Entiat are unnamed, make up Ray's "Central Interior Salish" cluster in his 1936 village study. Similarly, all four -- again the Entiat remain unspecified -- are coalesced for descriptive purposes in his 1939 general analysis of cultural relations among the native societies of the Plateau; here, as with Teit, he extends, for the sake of convenience, the more specific term "Wenatchi" to this larger, multi-unit entity. In his 1974 more extended native village catalog of this section of the Columbia Valley, Ray at last distinguishes the Entiat from the Chelan, Methow, Wenatchi proper, and Columbia as a separate "tribal" population. Nevertheless, he continues to recognize a fundamental similarity in the life modes of the first four of these groups, the Columbia being placed in a different cluster with the Southern Okanagan, Sanpoil, and other tribes to the north.

Of these four tribes, ethnographic information is available in some detail only for the Wenatchi.

It is of interest that observers as early as Parker (1842:313) sensed differences in cultural and tribal ethos between the Middle Columbia Salishans on the one hand and both the upriver Salish-speaking groups and the downstream Sahaptians on the other. He writes:

Between Okanagan and the Long Rapids [Priest Rapids] are detachments of Indians, who appear poor, and wanting in that manly and active spirit, which characterizes the tribes . . . [like the Okanagan and Colville upstream]. South of the Long Rapids, to the confluence of Lewis' [Snake] river with the Columbia, are the Yookoomans [Yakima], a more active people.

Evidently the Chelan were included by Parker in this "poor" group cluster. At any rate, his characterization of these Middle Columbia tribes is basically perceptive. Their peaceable and unspectacular life mode stood in contrast to the life ways of the Okanagan, Spokan, and Colville in Parker's day. The Okanagan had had a trading post in their country for 25 years; the Spokan had had one for some 15 years before it was relocated to Colville; and the Colville had had a post for the previous 10 years, to say nothing of possessing their great intertribal salmon fishery at Kettle Falls. And the Middle Columbia life patterns contrasted likewise with the ways of the horse-rich, buffalo-hunting Sahaptians with their post at the mouth of the Walla Walla, their great intertribal rendezvous, their fiercely hostile relations with the Shoshoneans to their south, and their vigorous, exciting life style in general.

Linguistic Affiliation

The Chelan were evidently not only very similar to the Wenatchi culturally, but the two spoke the same Interior Salishan language, though they differed slightly at the dialect level (Teit 1928:93). Together with the Entiat and the Columbia, they comprised the language unit now commonly termed "Columbian" by Plateau linguists (Thompson 1979:693-694). The speech affiliation of the Methow is somewhat less evident. Teit (1928:93), on the basis of his field research among the Columbia in 1908, and later Ray (1932:10), relying on Sanpoil information, place the Methow with the Columbian language tribes, though Teit recognizes some leanings toward the Okanagan language to the north and east. More recently, Kinkade (1967) and Thompson (1979:683-694) regard Methow as an out-and-out Okanagan dialect. Kinkade observes, however, that there is some evidence that Methow at an earlier date was part of the Columbian continuum but for some reason has shifted during fairly recent times toward Okanagan until it became wholly a dialect of the Okanagan language.

The relevance of these data to an attempt to describe -- largely, unfortunately, to reconstruct -- traditional Chelan culture is commented upon below.

Demography

No even roughly reliable head count of the 1811-1850 period exists for the Chelan. This is partly because their population center lay on Lake Chelan, well back from the Columbia River highway, the people of these lake winter villages and summer camps not being really seen until the 1850s. Partly because, as already noted, the Chelan were so frequently lumped with other groups in various ways and combinations; in these cases it is impossible to segregate the Chelan from the whole. Partly because of the inherent problems in making head tallies owing to the high mobility of the population and to variations in village and camp sizes by season and from year to year. And partly because of the effects of new waves of epidemics that passed through the middle Columbia region in the first half of the nineteenth century. For a more detailed discussion of these difficulties see Teit (1928:97-99), Ray (1932:21-22), and Smith (1983:137-138).

How unsatisfactory the earlier data are may be illustrated by the following estimates. According to Gibbs (1855a:417-418), Wilkes in 1841 approximates the "Okinakane" population at 300. If the Chelan -- and the Methow, Entiat, Wenatchi, and perhaps the Columbia also -- are included in his roster, they are presumably buried in this very small 300 estimate: Wilkes may be following Alexander Ross (1966:289-290) who, early in the 1800s, included the Chelan and the other native groups down the Columbia below the Okanogan Valley as far as Priest Rapids with the Okanagan as "tribes" of a single "nation," his "Oakinackens." Warre and Vavasour give a figure of 300 for the "Okanakane, several tribes" in 1849. Again the Chelan and their neighbors as noted above may be incorporated in this population approximation. Dart's data of 1851 give 300 to the Rock Island people (Columbia) and 320 to the "Okinakane" and in 1853 this same field investigator assigns 550 to the "Pisquouse [Wenatchi] and Okinakane" together. The difficulties inherent in sorting out these data in terms of the Chelan and the other tribal units of the Middle Columbia, if they are numbered in any of these figures, are more than obvious.

Similarly, Mooney's (1928:16) data of the early 1900s on this segment of the Columbia River are too confused to be helpful. No mention is made of the Chelan. Presumably they are included with the Methow, who, whatever the case for the Chelan (and Entiat), are explicitly entered in his list with the "Isle de Pierre [Rock Island] (Columbias, Moses' band)." This composite Methow-Columbia unit is estimated to have had a 1780 population of 800 and to have numbered 324 in 1907. Mooney also lists the "Piskwau, etc.," a group embracing not only the "Wenatchi" but also several Sahaptian tribes to their south. It is conceivable, though unlikely, that the Chelan are buried in this Piskwau cluster of linguistically dimorphous tribes, to which he attaches a 1780 figure of 1,400 persons. No separate 1907 census count is given even for this cluster: it is merged with still other tribal groupings before population estimates are presented.

According to Teit's (1928:97-99) Columbia and Wenatchi informants, the Middle Columbia groups were very numerous peoples in precontact times. By the mid-1800s, however, through disease and wars they had become mere remnants of their former size. While there may be some overstatement in these remembrances of former strengths, at least the effects of waves of pestilence, which Teit reports in some detail on informant recollection scourged them four times or more in the first half of the nineteenth century, were without doubt devastating. He concludes that "it may be safe to conjecture that the total population of the [Middle] Columbia group [the Chelan, Columbia, Wenatchi, Entiat, and Methow] at one time was at least about ten thousand." Surely the head-count figures of the preceding paragraph grossly underestimate the demographic strength of the Middle Columbia peoples in aboriginal days and even in the middle 1800s.

In this context it is instructive to note that the population of one Columbia village, that at Rock Island, was estimated by David Thompson (1914:53; Glover 1962:345-346) on July 7,1811, at about 800. This figure was arrived at by pacing off the length and width of the two very long, tule dwellings of the camp, approximating the number of families at about 120 by using these dwelling measurements, and then multiplying this family number by an estimated average family size. In spite of the documented epidemics of the early 1800s, these data for this single 1811 community suggest that Wilkes' 1841 300-person estimate for the "Okinakane" tribe as a whole (if this was Wilkes' intention) was probably too low -- perhaps substantially low -- even for 1841.

For the Chelan proper the only genuinely informative demographic data known to me are the Chelan winter village and summer camp estimates of Ray (1936:141-142; 1974a:419-423) together with the somewhat arbitrary figures that I have assigned to those Chelan population aggregates of Ray for which he provides no head count approximations but only descriptive guides of the "very large," "large," and "small" variety. The premises assumed and methods followed in translating Ray's adjectival estimates into numbers have been described elsewhere (Smith 1983:276-277). Ray's approximations, based on informant inquiry, are for the mid-1800s. It may be taken as a certainty that the Chelan population was somewhat greater in earlier times.

As I compute Ray's demographic data, I arrive at a winter Chelan person count of about 225 in the Columbia Valley villages and 1,185 in those villages occupied around Lake Chelan. The corresponding summer estimates are 230 persons for the river-side camps and 990 for those in the lake area (Smith 1983:278, 280, 318-320). Plainly these numbers, even if for some reason slightly skewed, underscore the lake population focus -- and therefore subsistence resource area emphasis -- of the Chelan.

| SUBSISTENCE |

The subsistence resources of the Chelan included fish, game, and plant foods, apparently in a relatively balanced supply. It is a shame that so little is known about this so basic a segment of Chelan culture and the details of the group's adaptation to its particular bioenvironment.

Fishing

Fish must have provided an important component to the food resources of the Chelan, though certainly a somewhat smaller share than among the Wenatchi. At least in protohistoric and postcontact times, salmon were unable to reach Lake Chelan and its feeders, the tumbling waters of Chelan River -- -"a roaring little stream" Symons (1882:42) calls it -- between the lake and the Columbia being too difficult for them to ascend (Ray 1936:141; 1974a:420). Even on the Columbia the tribe appears to have maintained established villages and camps at only six sites, if the memory of Ray's (1936:141-142; 1974a:419-423) informants can be relied upon. Of this half-dozen, only three are stated to have been occupied in summer. And only one -- that one mile north of Navarre Coulee -- is specifically mentioned as a locality from which fishing was carried out in the Columbia and even this camp had no more than from three to 30 dwellings (Ray 1974a:423).

From these ethnographic data, fragmentary though they are, it is difficult not to conclude that Chelan territory was poor in suitable salmon fishing localities. This conclusion is to some degree supported by the historical records of David Thompson, Alexander Ross, and much later Thomas Symons. When descending the Columbia in early July, 1811, when the water was very high, to explore the river for the North West Company, Thompson (1914:52) mentions only a single rough stretch of fast water in the river course that I define as lying within traditional Chelan boundaries, that about 2 miles, by his estimate, below the mouth of Chelan River. Here on July 6, 1811, he encountered a strong rapid and islands, which, however, caused his canoe no difficulty. Earlier, on July 3 and 4, Thompson (1914:44, 47, 49, 50, 52, 54; Glover 1962 :340-346) had received presents of "2 half dried salmon" and five poor salmon from the Sanpoil, who were taking them at a small weir; on the 5th, gifts of "5 good roasted salmon" and "a good salmon" from the Nespelem; and at an earlier hour on the 6th, when he had observed as he passed and briefly visited a Methow village at the Methow River confluence, a present of "3 roasted salmon." Later, from the Rock Island Columbia, the next people he came upon below the Chelan country, he obtained two salmon. Nevertheless, he makes no mention of seeing a single Indian at the swift water, noted above, in what we know to have been Chelan territory, nor, in fact, in the entire Chelan length of the Columbia.

Why were there on Thompson's passing no Chelan taking salmon and apparently no river camps such as reported as summer settlements ethnographically? Perhaps the water was still running too deep over their main river fishing rapids, for Thompson (1914:48), as already noted, reports that the river was very high. Possibly because the other groups were fishing at the time not in the Columbia itself but on lateral streams (as the Sanpoil certainly were), salmon streams that appear to have been lacking in the Chelan homeland. Whatever the reason, these Thompson data convincingly demonstrate that the Chelan were not at their river fisheries when his small party traveled by and so indirectly argue for the special importance of the Lake Chelan region as a major subsistence resource area for the tribe.

On July 26, 1811, Alexander Ross (1966:139-140) of the Pacific Fur Company, by dint of "a good deal of pulling and hauling," ascended a rapid which he terms "Whitehill rapid." Here he found the river making "several quick bends" and "almost barred across by a ledge of low flat rocks." This difficult stretch was either that which Thompson had passed and reported upon when heading downstream 20 days earlier, or, more probably, that about five miles farther downstream later described by Symons as a boulder and bar rapids. The precise location of Ross' barrier is, in any event, unimportant in this present context, for both possible rapids were within Chelan borders. Ross encamped for the night at the head of this swift water without seeing there a single Indian. The following day, after an early start, he passed about 10 a.m.:

a small but rapid stream, called by the natives Tsill-ane [Chelan], which descended over the rocks in white broken sheets. The Indians told us it took its rise in a lake not far distant.

Not far upriver he met some Indians (presumably Chelan), put ashore, and spent the night. From these friendly natives he secured "some salmon, roots, and berries." On the following day but one, he reached the Methow River, which he calls the "Salmon-fall River," where the Indians presented him with an "abundance of salmon."

As in the Thompson instance, to summarize, no natives were to be seen at the fast water below the Chelan River mouth, but those met above that mouth had some salmon, although, unless we squeeze too much from Ross' brief account, not nearly the rich supply possessed by the Methow.

Seventy years later Symons (1882:39, 42, Figures 13-15), passing down the Columbia in a bateau in early October, 1881, to assess the navigational possibilities of the river, notes nothing but an occasional "little ripple and sand-bar island" between the entrance of the Methow and the confluence of the Chelan River. Below the Chelan River, he passed "an occasional ripple . . . and came soon to some quite strong rapids." These, which he named "Downing's Rapids," are without any doubt those mentioned by Thompson and possibly also by Ross. About seven miles downstream from the mouth of the Chelan, he came upon "a rapid, where the water flows over a bowlder and gravelly bar, on which there was a depth of from seven to eight feet." This location (Symons 1882:map 15) is just downriver from the point, precisely 7 miles below the Chelan River just as Symons estimates, where the Columbia bends sharply to the northwest for about 2 miles (USGS Wenatchee quadrangle 1957). Though not the rapid noted by Thompson on July 6,1811, it may quite possibly be Ross' Whitehill Rapid. Symons evidently observed no Indian settlement at either his Downing's Rapids or this boulder-and-bar rapid and found no Indians fishing at either, although he had camped with the Chelan at their "principal village" 1 mile up the Columbia from the Chelan River entrance and later found several Indians spearing salmon from canoes at the Entiat River mouth slightly farther downstream.

These historical notes suggest, like the ethnographic data, that the Columbia River rapids in Chelan territory did not lend themselves to salmon fishing for some reason, either in the high water of July or in the lower water of early October. And further that there were in Chelan country no tributary streams that offered acceptable salmon fishing possibilities like the Methow and Entiat Rivers. These conclusions are supported by Ray's (1936:141; 1974a:419, 423) informant-derived data that in traditional times the Chelan gathered for salmon at the Entiat fishery, actually a relatively unproductive location, at the entrance of the Entiat River into the Columbia, and at least the people of the large Chelan winter village at the lower end of Lake Chelan journeyed to the Wenatchee River for salmon fishing. Further, after about 1870, members of the tribe were accustomed to fish for salmon at the important Methow fishing location at the Methow River mouth.

To focus these data on the special interests of this study, it appears that an important fraction of the fish in the Chelan diet must have been nonanadromous varieties, fish that were available in the small streams that fed Lake Chelan. Ray (1974a:420-423) lists 13 Chelan habitation sites around the edge of the lake. Of these, 11 were occupied in the summer season. Two of this number are said to have been at the mouth of creeks emptying into the lake, but Ray's data fail to mention fishing as a subsistence activity of these communities. On the other hand, some fish are reported to have been taken by people living at the large village at the lake outlet. These data surely understate the importance of nonanadromous fish taken around the lake shores.

In contrast to the salmon situation among the Chelan, the salmon resources of the Wenatchi were very substantial: in normal years fish were secured in great quantities at localities along the Columbia and even more importantly at sites on the Wenatchee River and certain of its laterals (Ray 1936:142-143; 1974a:424-426; Smith 1983). Indeed, the salmon yield where Icicle Creek flowed into the Wenatchee River was so renowned that the locality became during the season an intertribal fishery (Ray 1974a:425). It is obvious, in short, that salmon must have been of lesser significance to the traditional Chelan than among the Wenatchi, and that nonanadromous fish must have contributed more to the Chelan food supply.

In leaving this salmon issue, a bit of sheer speculation may not be wholly inappropriate. The Chelan area appears to lie in a geologically instable region. The early historical documents report that mild and strong earthquakes were not uncommon. According to Byrd (in Durham 1972:11 fn. 20, 12 fn. 23, 20 fn. 43, 24 fn. 52), Ribbon Bluff (or Cliff) -- along the western side of the Columbia River just downstream from the Chelan River mouth (see Symons 1882:42, map 15) -- was thrown into the river by a quake in December, 1872. This same disturbance produced a huge geyser at Chelan Falls, which, after continuing for "a long time," gradually subsided. Throughout most of 1873 "the whole mountain range between Lake Wenatchee and Lake Chelan was shaken" by almost daily tremors. In 1887 a very early White settler at Entiat recorded "three days of severe earthquake" shocks. In September, 1899, a very large underwater land shift, possibly a large rockfall, produced huge waves on Lake Chelan.

Further, Lake Chelan was subject not only to a normal spring high water owing to the usual seasonal runoff but occasionally to true flooding when precipitation and temperature conditions were right. Thus in 1894 the lake area experienced a huge flood that inter alia

raised the lake level 11 feet over the 1892 low water mark, washing out all the old Stehekin River logjams, . . . changed the course of Fish Creek . . . , washed out and caved in the Chelan River banks below [Chelan] town until it sounded like thunder and felt like earthquakes, [and] rechanneled a fourth of a mile of the mouth of the Chelan River; . . . (Byrd in Durham 1972:2 fn. 6; see also 1 fn. 2 and pp. 7, 8).

It seems theoretically possible that in prehistoric times either major, though local, earthquake activity or massive lake flooding with consequential outlet erosion could have significantly changed the drainage pattern of Lake Chelan. That the lake surface was higher even in late prehistoric days is suggested by the well-known pictographs on the sheer rock wall at the upper end of Lake Chelan, observed by Merriam about 1880 (Symons 1882:40). The highest of these are reported to have been at least 35 feet above the lake level in predam times and to have been reachable only from watercraft when the level was, say, 30 feet higher than in the early historic period (Cain 1950:15; Symons 1882:40; Byrd in Durham 1972:24 fn. 52). If these data are basically accurate, some quite recent -- even in the historical time scale -- shift in the outlet arrangement of the lake must have occurred to lower its southern rim. Earth movements or perhaps even massive flood action (or both) might have produced the barriers in Chelan River that in ethnographic times prevented salmonid ascent to the lake or possibly removed such barriers, allowing anadromous fish navigation to the lake, and later created them again. Or altered the outlet from some other course to today's tortuous, rocky Chelan River canyon. Two possible early outlets would appear to have been Knapp and Navarre Coulees, the first about five miles long and the latter approximately eight miles in length, as compared with Chelan River which today falls the about 375 feet from the lake surface to the Columbia River in only about three miles (Byrd in Durham 1972:7). In this connection it is of interest that in 1892 the sternwheeler Stehekin, cut in two, was hauled by wagon up Navarre Coulee from the Columbia to the lake: obviously this "road" is nothing like the twisting Chelan River canyon with its boulders and falls. And as already noted, the modern highway runs up Knapp Coulee from the Columbia to Lake Chelan. Either of these drainage streams, if such there was, might have been manageable to anadromous fish. A careful examination of the topographic and geological evidence would doubtless test these highly speculative hypotheses, but its seems conceivable that salmonids were able to ascend to Lake Chelan and the Stehekin drainage during some periods in the prehistoric past.

In the absence of specific ethnographic information for the Chelan in regard to fish varieties and fishing techniques, save as noted below, the Wenatchi data are summarized here in keeping with the procedural scheme already explained.

Among the Wenatchi, anadromous fish, especially salmon, of which the Chinook variety was most important, and steelhead trout, comprised staple foods. As already noted, migratory fish were certainly much less important among the Chelan, but of these fish that were taken by this group, either in their own section of the Columbia or at fisheries in the country of neighboring tribes, these two varieties were presumably the most significant. Eels were also taken by the Wenatchi as a food, but whether this was likewise true of the Chelan is not entirely certain. They are said to have been considered inedible among the Flathead, Kutenai, Kalispel, Carrier, Chilcotin, Shuswap, Lillooet, and Klikitat (Ray 1942:104). On the other hand, they were eaten among the Coeur d'Alene, Sanpoil-Nespelem, Southern Okanagan, Thompson, Kittitas, Tenino, Umatilla, and Nez Perce as well as among the Wenatchi (Spinden 1908:206; Post in Spier 1938:18; Ray 1942:104). Inasmuch as these fish were widely eaten in the central and western Plateau, whatever may have been the situation elsewhere in the area, it may be presumed that they were also considered an appropriate food resource among the Chelan, but evidence on the point is lacking.

A catalog of nonanadromous fish caught by the Chelan for food is not available, nor for that matter by the Wenatchi. But, according to Post (in Spier 1938:11-18), the Southern Okanagan, a short distance up the Columbia from the Chelan, supplemented their salmon and steelhead, taken from June until October, with suckers, trout, whitefish, squawfish, lamprey eels, and ling. All of these fish were native to the Columbia Basin region (see Wydoski and Whitney 1979) and so presumably all or most were available to the Chelan in their lake area.

Several different fish are noted in the early historical records as occurring specifically in Lake Chelan and its feeders, including the Stehekin system. These include several varieties of trout: bull trout (Dolly Varden), rainbow trout, and cutthroat trout (Durham 1972:15; Byrd in Durham 1972:12 fn. 25, 15 fn. 26). This list could certainly be extended or at least further documented by a fuller search in the early local records.

Save for Ray's report, mentioned above, that fish were caught by Chelan living in the village at the southern end of the lake, we know nothing ethnographically about fishing localities in the lake sector. Historical accounts of the late nineteenth century, when White settlers were first moving into the region (Byrd in Durham 1972), provide some useful general and specific information.

- Large numbers of rainbow and brook trout were found in numerous streams putting into the lake, Fish Creek being especially notable for its brook type (Durham [1972:15] writing in 1891). (The true brook trout [Salvelinus fontinalis] is an introduced species in Washington [Wydoski and Whitney 1979:47].)

- The best fishing in the lake "at proper stages of the water," according to early White anglers, was where "a rill, a brook or a foaming torrent comes leaping over the cliffs, and is disolved in a mass of spray and foam before it strikes the blue-black waters of the lake" (Durham 1972:12). While these non-native fishermen were using pole, line, and hook -- a technique not particularly favored by Plateau tribes -- these date suggest the possibility of traditional tribal weirs, other types of traps, spear fishing, or still different fishing methods at at least certain of these locations.

- Around the mouths of the creeks where they enter the lake are the feeding grounds for the large lake trout that attain lengths of 2 to 2.5 feet (Lyman [1899:198] writing ca. 1898).

- Large trout were caught in considerable numbers at the very head of the lake where the swift current of Stehekin River flows into the lake (Durham 1972:23).

Mountain streams likewise had their fish. When in 1886, Wm. Sanders and Henry Domke made their difficult way over Sawtooth Ridge from the Methow country to the upper segment of Lake Chelan, they lived much of the time on fish taken in the small streams they encountered, Canoe and Prince among them (Durham 1972:19-20).

Evidently Lake Chelan was natively very rich in fish. In the early 1890s, the hotel at Lakeside on the south shore of the lake near its outlet is reported to have had a standing order for 100 lbs. of fresh fish weekly (Byrd in Durham 1972:15 fn. 27). Moreover, commercial fishermen, quite active on the lake at this time, supplied the Waterville and Coulee City markets with fish (Durham 1972:15).