|

North Cascades

Ethnography of The North Cascades |

|

LOWER THOMPSON

| DATA BASE |

The Thompson tribe was composed of two "divisions," of a Lower group and an Upper cluster of bands. In general, the Lower Thompson, as described below, were the people of the Fraser Canyon and of the forested hills and mountains that lay on either side of this awesome chasm and reached southward into the upper Skagit country within the boundaries of the North Cascades National Park. The Upper Thompson, in contrast, had their homeland in the open forest, sagebrush, hill, and mountain country of the Fraser and Thompson Rivers east of the Cascades.

Because of the particular concerns of this study, the locus of this chapter is on the Lower Thompson. Two bodies of data dealing with this group, the ethnographic and ethnohistorical, are merged in the following pages. Nevertheless, the information is not extensive. To fill important subject lacunae and add meaningful cultural details, this relatively meager data base is extended by the incorporation of a substantial corpus of ethnographic material relating to the Thompson tribe as a whole and to the Upper Division more particularly. The fundamental life modes of the two groups were certainly much the same. Still, there were some notable and surely many subtle differences, in part the consequence of the different ecological settings of the central home areas of the two divisions and in part owing to the greater exposure of the canyon people to coastal and lower Fraser influences and of the upper people to Plateau contacts. At least to the extent that both divisions made substantial use of the higher sections of their country in hunting, gathering, and even fishing, their cultural behavior must have been fundamentally identical. Fortunately, this is the segment of tribal life of special interest to this present study. To keep the data properly sorted out, however, the specific population entity described is identified where these facts are provided in the source. When no such data appear in the following pages, the information is to be understood as presumably generic Thompson in its relevance.

The ethnographic material on the Lower Thompson is drawn in part from James Teit's (1900) extended, first-hand report on the Thompson Indians. While bearing largely on the Upper Division, it presents some data, either expressly stated or implied, that pertain to both groups and other information described as relating exclusively to the Lower people. Teit, who was married to a Thompson woman and spoke the language fluently as well as neighboring related languages, was discovered by Franz Boas in 1894 and was given a certain amount of basic ethnographic training. With Boas' support he recorded in depth the traditional life of the Thompson Indians as he saw it, then in its final stages, and supplemented these observations by informant inquiry. His Upper Thompson manuscript was prepared in 1895; that on the Lower Thompson, in 1897. The two were merged by Franz Boas in Teit's 1900 publication. The data are especially rich in the material culture sections, though quite respectable in many other cultural domains. They show, of course, the subject gaps common in ethnographic studies of his time. They also possess less obvious flaws -- and doubtless strengths -- as a consequence of Boas' editorial attention: in some subject areas -- e.g., art and mythology -- it is not invariably easy to ascertain which of the two is speaking (see Maud 1982:63-77). Nevertheless, Teit's Thompson report ranks high among Plateau ethnographies. Additional ethnographic details are extracted from a number of Teit's (1898, 1928, 1930a, 1930b, 1930c) other studies and incorporated into the cultural account that follows. Owing to time pressures, the scraps of folkway data imbedded in his extensive mythic collections have not been extracted and introduced into this report.

To Teit's data for the Thompson as a whole, for the upriver bands in particular, and for the Lower Thompson where specifically indicated is added the ethnographic information secured by Verne Ray (1942) in the 1930s from a Lower Thompson informant then in his 60s. These data are unique in describing in their entirety the traditional culture of the Lower group, revealing, when compared with Teit's material, their lifeway differences from the cultural patterns of the Upper people (Ray 1942:103). As noted in more extended form in the following Chelan chapter, Ray's data were collected through a culture-element check-list in which traits were succinctly defined and then coded simply as present, absent, sometimes occurring, practiced by women only, etc. They are grouped into functional complexes -- e.g., into a trait cluster dealing with deer hunting methods. Nevertheless, individual elements are not infrequently difficult to assemble into satisfying clear and coherent wholes, and relationships between complexes are obscure. Further, the data were gathered from a single informant and some 40 years after Teit's material and so doubtless with some unknown amount of tribal culture-memory loss: accordingly, some of the apparent differences between Lower and Upper cultural practices are surely an artifact of imperfect and incomplete data. Finally, Ray's contact with the Lower Thompson was brief and therefore in a sense casual rather than personal and intensive over years as in Teit's case. On the other hand, Ray's information has all the marks of a first-rate professional ethnographer with a wide and detailed knowledge of Plateau cultures and was secured using careful, systematic field techniques. It represents, in fact, the only intensive ethnographic fieldwork to my understanding on the traditional culture of the Lower Thompson, the division that utilized the Park country, and is, therefore, especially valuable in the context of this present study.

In the 1890s Charles Hill-Tout undertook a field study of the Upper Thompson. Published in 1900, his report consists primarily of an ethnographic section, a few remarks on the archaeology of the Thompson homeland and on the physical characteristics and language of the tribe, and a comparatively long myth collection. Relevant incidental data in this report that concern the Lower Thompson are meshed into this present chapter, as is occasional Upper Thompson information of special interest, as where it fleshes out an otherwise inadequate Lower Division account. English-trained as a clergyman, Hill-Tout is at many points naive in his description and theoretical underpinning, as well as curiously wandering and irrelevant. Approaching the Thompson with a coastal Indian, British pastor, and firm Anglo-European mind-set, he speaks, for example, of a Thompson chief as the "lord paramount," of a Thompson nobility where, in fact, no inherited class distinctions existed, of the Thompson as having "many singular and superstitious customs and practices," and, on the other hand, of the group as a "finer... race than their congeners on the coast" (Hill-Tout 1900:501, 506, 513, 517). He alludes to, but happily does not discuss here, his uninformed theory of a South Pacific origin for the entire Salishan group (Hill-Tout 1900:517). Yet he had the good fortune of working with Chief Mischelle, a highly intelligent Upper Thompson Indian and evidently a fine informant. In recording his field data, Hill-Tout took minimal notes, later expanded them from memory, and still later checked his enlarged draft with his informant. In this process, he freely introduces an unmistakable Hill-Tout element, especially in his mythic sections where descriptive color is added to heighten the impact of the narrative and suggest the emotional content of the teller's performance. So far as these myths are concerned, though straying from the narrator's often greatly compressed version since the tale ../background was well understood by his listeners, this technique produces a richer and in a special, broad sense, a rather more faithful rendition of the myth in its native cultural context. Hill-Tout's information cannot compare with Teit's intimate, detailed, and well informed data of the same time period (cf. Maud 1982:29-38).

A few further notes on Thompson ethnography have been drawn from two narrowly focused studies by Teit (1930c) on Thompson tattooing and body painting, have been borrowed from a compendium of Plateau food plant data by Turner (1978), and have been culled from several other sources of lesser importance.

Because of time pressures, the ethnohistorical sources have not been properly surveyed for early data that would expand meaningfully the ethnographic picture of traditional Lower Thompson lifeways. So far as this Division is concerned, however, the most important historical archive has been thoroughly examined and its significant ethnographic remarks placed in their proper context in this present study. This document is the record of Simon Fraser, made when he and his party, exploring, descended and then returned up the Fraser River in the summer of 1808.

Some few fragments of additional ethnohistorical material have also found their way into the following account. These include in particular the observations of Sir George Simpson who passed down the Fraser Canyon by watercraft in 1828 and those of R. C. Mayne, a member of the British Boundary Commission, who ascended the Fraser gorge in 1858. Fraser's report of the terrifying hazards of the Fraser Canyon, confirmed 20 years later by the disbelieving Simpson, led the traders to seek and find alternative routes over the Cascades in this region. One such path proceeded up the Coquihalla and then overland either up to the Kamloops area on the Thompson River or over to the Tulameen and Similkameen and down to the Okanagan country. Another ran up Harrison Lake to Anderson and Seton Lakes and on to the Kamloops sector of the Fraser. Both by-passed the supremely dangerous canyon sector of the Fraser, the core portion of the Lower Thompson territory. It is not surprising, given the hostile environmental accounts of Fraser and later Simpson, that early visitors to the Lower Thompson canyon villages were few and that ethnohistorical documents for the pre-1850 period are largely lacking.

As noted by Mayne (1862:305ff), no Protestant missionary entered the upper Fraser and Thompson River country before 1857. The extent to which the Catholic priests administered to the Thompson in earlier years I do not know, but Mayne, quoting Hudson's Bay Company sources, reports for even the lower Fraser Valley that their efforts were ineffective in changing the Indian life in any material way. These remarks are confirmed by Teit (1930c:403) who notes that the White influence on the Thompson first became strong about 1858. It was, in fact, only the discovery of gold in the 1850s on the "bars" of the Fraser from Hope on upstream by Yale and through the canyon reach to the Lytton district that brought Whites in numbers into the deep gorge country and the home area of the Lower Thompson. At any rate, I know of no published missionary records or Hudson's Bay reports that provide ethnohistorical data of significance relating to the Lower Division and its homeland during the first half of the 1800s.

| INTRODUCTION |

In this section are summarized (a) the various terms used for the Thompson tribe by other groups and for its Lower and Upper Divisions, (b) the traditional boundaries of the Lower Thompson, (c) the cultural and linguistic affiliations of the tribe, (d) the population data available for the early postcontact years, and (e) the physical characteristics of the tribal members.

Ethnonymy

The Thompson are referred to in the literature under several alternative names. Among these are the following, some of which occur in orthographic variants:

Couteau or Knife Indians: used by early Hudson's Bay Company personnel (Teit 1900:167).

Cê'qtamux: occasional Lillooet term (Teit 1900:167).

Lükatimü'x: occasional Okanagan term (Teit 1900:167). Variant in Columbia Salish (Teit 1928:92).

Nko'atamux: Shuswap term (Teit 1900:167). Variants in Southern Okanagan (Walters in Spier 1938:78), Sanpoil-Nespelem (Ray 1932:11), Columbia Salish (Teit 1928:92), Okanagan Sanpoil-Lakes (Teit 1930b:202).

Nicouta-much or Nicouta-meens: recorded by Mayne (1862:296) for the Thompson as a single group, whose territory extended from Spuzzum northward to that of the "At-naks or Shuswap-much" [Shuswap]. A variant -- possibly only an orthographic variant -- of the preceding term, but spelled so differently that it deserves mention.

NLak·a'pamux: derived from the Thompson name for themselves (Teit 1900:167).

SEm

'mila: used by neighboring Indians of Fraser delta (Teit 1900:167).

Sa'lic: occasional Okanagan term (Teit 1900:167).

Numerous additional variants of some of the above, with citations to the generally old and obscure publications in which they appear, are listed by Hodge (1910:89). Swanton (1952:588-589) obviously merely reproduces Teit's data. The terms in the above inventory are spelled as they appear in one or more of the references cited; no attempt has been made to reduce the disparate phonetic systems to a common base.

As noted below, the Thompson had names designating their two divisions -- the Upper and Lower groups -- and among the Upper Thompson that distinguished their four major bands -- the Lytton, Upper Fraser, Spences Bridge, and Nicola units to employ Teit's terms. The Lower Thompson, a comparatively small, compact, and culturally and linguistically essentially homogeneous group, had no band units paralleling those of the upper people. They had, however, names for each of their 19 villages as itemized by Teit, their residents commonly being referred to as "the people of X village." (Boas 1895:524; Teit 1900:169-171)

Tribal Territory

The Thompson were separated in their own view into two somewhat distinct population clusters, marked by significant cultural and minor dialectic differences: into Upper and Lower Divisions to use Teit's (1900:166, 168, 171) designations.

The Upper group -- the Nku'kümamux, "people above [Lytton]" -- -occupied a section of the Fraser River, the lower reaches of the Thompson River which flows into the Fraser, and the lower Nicola River, a small tributary of the Thompson (Figure 3-1). To some extent even in early traditional times they hunted for elk and deer and fished all over the middle Nicola drainage as well, making it their home for parts of the year, some wintering there, even though this was strictly country belonging to the Athapascan-speaking Nicola tribe. This Upper Thompson region east of the Cascades was rugged and hilly, but the mountain contours were rounded and their slopes gentle. The surface was intersected by many deep and narrow valleys. Somewhat farther east rolling hills or plateaus prevailed. Lower elevations were covered with sagebrush, greasewood, and other dry climate vegetation; the higher altitudes and mountain tops supported grass and scattered timber, principally pine. Summers were hot; winters were generally short and only moderately cold with light snowfall. (Teit 1900:168, 175, 178, 1930b:213-214; cf. Mayne 1862:383)

The Lower Thompson -- the Ut 'mqtamux. "people

below [Lytton]" -- claimed the deep canyon and rushing river segment of

the Fraser Valley where it sliced through the Coast Range south of the

country of the Upper group, whence the designation "Canyon Indians"

sometimes given them. In addition to the very important Fraser River

itself, they used as their principal subsistence grounds the rugged

country, with its towering mountains, narrow valleys, deep gorges, and

thick timber, on both sides of the Fraser. To the southeast and south

they also exploited the food and other resources of the regions of the

Coquihalla River and the Upper Skagit. According to Teit's Thompson

informants, they likewise hunted in and claimed the Chilliwack Lake and

upper Chilliwack River area (Figure 3-1). This Lower Division also

considered as theirs and ranged over in their hunting activities an area

south of the international border, specifically the northern section of

the North Cascades Park Complex and the high country on both sides of

the present Ross Lake. (Concerning conflicting aboriginal claims to and

subsistence use of these Chilliwack and Upper Skagit areas, see comments

below.)

'mqtamux. "people

below [Lytton]" -- claimed the deep canyon and rushing river segment of

the Fraser Valley where it sliced through the Coast Range south of the

country of the Upper group, whence the designation "Canyon Indians"

sometimes given them. In addition to the very important Fraser River

itself, they used as their principal subsistence grounds the rugged

country, with its towering mountains, narrow valleys, deep gorges, and

thick timber, on both sides of the Fraser. To the southeast and south

they also exploited the food and other resources of the regions of the

Coquihalla River and the Upper Skagit. According to Teit's Thompson

informants, they likewise hunted in and claimed the Chilliwack Lake and

upper Chilliwack River area (Figure 3-1). This Lower Division also

considered as theirs and ranged over in their hunting activities an area

south of the international border, specifically the northern section of

the North Cascades Park Complex and the high country on both sides of

the present Ross Lake. (Concerning conflicting aboriginal claims to and

subsistence use of these Chilliwack and Upper Skagit areas, see comments

below.)

In physical and biological terms, the country of the Lower Thompson was very complex. It extended from the bottom of the Fraser Canyon, with an elevation of only a few hundred feet, upward to rugged mountain peaks with areas of permanent snow and an arctic-alpine environment well above tree-line. East and west it reached from some distance west of the Cascades crest up over the watershed and down their east-facing slopes to just within the comparatively low and dry ponderosa pine country of the upper Similkameen. In fact, six distinct biogeoclimatic zones (including the Ponderosa Pine-Bunchgrass Zone in the east) are found within its borders (see later section discussing the Lower Thompson utilization of their high country), with their widely varying altitudes, precipitation levels, seasonal patterns, native animal and plant assemblages, and other natural resources so essential to a hunting, fishing, gathering way of life. Fraser Canyon, the site of the tribe's splendid salmon fisheries and all winter villages, was a region of abundant rainfall, especially in the south western quarter, and of heavy timber, primarily fir and cedar. Game was rather scarce; the taking of salmon was all important. Winters were short and the snowfall was occasionally heavy. (Teit 1900:166,168,169)

As the Nicola tribe vanished as a distinct ethnic entity during the early and middle 1800s, the Upper Thompson took over the middle Nicola Valley sector, while the Lower Thompson reached eastward into the middle Tulameen River country (Figure 3-1). Gradually they extended their territory down the Similkameen Valley to a point between Hedley and Keremeos, where they met the Okanagan expanding westward up the Similkameen. At first they hunted over this eastern country -- elk were especially abundant there -- and then began to maintain winter villages in the area. (Teit 1900:166, 168, 169, 1930b:204, 213, 214, 218, 257; see also Swanton 1952:430)

Figure 3-1. Territorial limits of the Lower Thompson (Utamqt) Division as

defined by Teit (1900:166). Letters (a)-(j) identify a number of additional

geographic features.

The Lower Thompson boundary is emphasized by a heavy dot-dash line. The

approximate territorial limits of the Athapascan Nicola, which disappeared

as an ethnic entity in early historic times, is strengthened by a heavy

dash line.

Arrows have been added at the international border to mark the approximate

eastern (E) and western (W) limits of the North Cascades National Park

Complex.

Teit's "Klickitat" term for the group adjacent to the Thompson on the

south was an early vernacular designation for some or all of the peoples

on the eastern face of the Cascades from the Thompson south to the

Dalles-Vancouver region. On this map it refers to the Upper Skagit.

Since the concern of this report is with the groups that made use of the Park region, close attention is given in the following paragraphs only to the traditional territorial boundaries of the Lower Thompson.

The boundaries of the aboriginal territory of the Thompson are not well described by Teit in his text. This is particularly true for the Lower Thompson and especially so for the small segment of their homeland that stretched into the mountainous terrain south of the Canadian line. We are told only that the hunting grounds of the Lower Thompson extended "southward to the head waters of Nooksack and Skagit Rivers" (Teit 1900:168). On the other hand Teit's (1900:166) tribal location map marks off the southern territorial limits of the Lower group with sufficient precision to allow them to be followed on contemporary maps.

According to this map (Figure 3-1), based it must be assumed on informant data but surely somewhat generalized, the home country of the Lower Division followed the Cascades crest from the present international line, describing an arc to the southwest around the headwaters of Lightning Creek. It crossed the upper Skagit River -- today's Ross Lake -- just above the mouth of Big Beaver Creek and headed westward over the mountains to the uppermost reaches of Baker River and Mount Shuksan. Thence it curved to the northwest to the Mount Baker region, crossed the North Fork of the Nooksack River in the Glacier area, and finally bent northeastward to arrive at the Canadian boundary southeast of Sumas Lake, now drained.

Evidently this region within the present State of Washington was regarded by the Lower Thompson as aboriginally theirs, for Teit (1900:175, see also 178) writes:

So far as current tradition tells, the tribal boundaries have always been the same as they are at the present day ... [i.e., in the 1890s, except for the Nicola and Similkameen River sectors taken over in the 1800s from the Nicola tribe].

Reference to the preceding Skagit and Chilliwack chapters will demonstrate that in the upper Skagit and upper Chilliwack country within the Park region, the ethnographic literature records conflicting territorial claims. The upper Skagit tribe considered theirs, according to Collins, the Skagit River to near its sources, though her informants conceded that the Thompson used the northern portion of this area in their food quest. Specifically, Collins (1974a:5) writes: "[On the north the Upper Skagit tribal country reached] the territory of the Thompson Indians who hunted along the Skagit headwaters in Canada. One northern headwater of the Skagit River comes near their territories."

The Chilliwack tribe, for its part, certainly had solid claim to Chilliwack Lake and to the Chilliwack River both feeding and emptying the lake. It may be seriously questioned whether in traditional times the Lower Thompson often -- perhaps ever -- ventured down into these lower elevations as Teit indicates.

One concludes that the Skagit region from some, presumably rather short, distance above the present international boundary downstream to the southern end of today's Ross Lake was a contested region, at least in the late protohistoric and traditional postcontact period. It was ranged over by Lower Thompson, Upper Skagit, and to some degree Chilliwack hunting and gathering parties. The northern valley and adjacent mountains were visited more by the Upper Thompson; the western mountains lying between the Skagit and Chilliwack Rivers and particularly their western flanks, primarily by the Chilliwack; and the more southern sector of this region in the lower Ross Lake area, mainly by the Upper Skagit.

Cultural and Linguistic Affiliation

It has been noted that according to Ray (1936:108:1939:147) the Thompson were culturally northward and eastward looking, most resembling the Lillooet, Shuswap, and Northern Okanagan and thus being perceptibly different in their lifeways from the nearby Southern Okanagan and other groups south of the international boundary. Teit (1900:167) made essentially this same point much earlier in an even more refined but more impressionistic manner in observing that the Thompson were culturally most akin to the Shuswap to their northeast. Both, however, were speaking most particularly of the Upper Thompson. The Lower Division, in contrast, was in many respects culturally oriented toward the lower Fraser and nearby coastal tribes, a leaning attested to by much of the data in the ethnographic section that follows.

The speech of the Thompson comprised a distinct language, most closely related but still unintelligible to that of the Shuswap to the north and to that of the Lillooet to the west (Figure 3-1). These three languages of interior British Columbia made up the Northern Group within the Interior Salishan Division; the Southern Group included the four Salishan languages -- Columbian, Okanagan, Kalispel, and Coeur d'Alene -- east of the Cascades and south of the Canadian border. Thompson speech was substantially more distantly akin to the Salishan languages of the British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon coast. (Thompson 1979:692-695)

The speech of the Upper and Lower Thompson differed only at the dialect level: i.e., the two divisions were able to understand one another (Boas 1895:524; Teit 1900:171).

Demography

No serious approximations of the size of the aboriginal population of the Lower Thompson appear, so far as I am aware, in the ethnographic literature. An attempt in this direction for the Thompson tribe as a whole and a few general comments concerning postcontact population reductions are, however, worth introducing into the record.

About 1835 Hudson's Bay personnel undertook a census of various Indian groups of British Columbia. These published counts, as Duff (1964:38) observes, are in general "obviously and grossly inaccurate," and so fail to provide an acceptable starting point toward late protohistoric and early postcontact demographic approximations. Duff's own attempt to begin with the first accurate censuses of the 1880s and work backward, taking into consideration epidemics, wars, and so on, yields some figures, but he collapses all these for the Interior Salishan peoples into one group from which it is impossible to extract the Thompson as a specific component of the total. (Duff 1964:39)

Sometime around 1850 I gather, A. C. Anderson, a chief factor in the Hudson's Bay Company who had "travelled a great deal in ... [the interior, Plateau] country," estimated the Thompson and Shuswap tribes together, groups "mustering annually on the Fraser," at 6,000 or 8,000 persons (Mayne 1862:43, 297). There is no way to divide this demographic lump figure between the two tribes, much less between the Upper and Lower Divisions of the Thompson. This may be one of the Company census figures to which Duff alludes, but, if so, whether it is one of the better or one of the more imperfect "counts" in Duff's judgment is uncertain. In any event it, like other similar lumping demographic estimates of the mid-i 800s, furnishes no useful information regarding the Lower Thompson population size.

The only early population estimate for the Lower Thompson provided in the historical accounts of which I am aware is the rough approximation of Simpson (1947:34-38). In his brief account of his two-day water journey down the Fraser Canyon in mid-October of 1828, he writes that "the Natives ... were exceedingly numerous" and that "the whole of this [canyon] population ... [numbered] several thousand souls." Impressionistic though this figure is, it is still not without meaning, for Simpson had just come down the upper Fraser River to Alexandria, gone by horse from there across to Kamloops, and then descended the lower Thompson River through the Upper Thompson country. In the lower Thompson River area he had observed that the population "is numerous, forming themselves into Camps of 10 to 12 Families at the different [salmon] Rapids" and that "the Natives ... become more numerous as we descend" the Thompson to its mouth. His Lower Thompson demographic note, as reported above, was written against this ../background.

On the subject of population reduction among the Thompson in the 1800s through diseases of epidemic proportions a few fragments of ethnographic and ethnohistorical information have been uncovered.

In his 1908-1909 manuscript, Mooney (1928:2, 27) gives some attention to the population reductions among the native groups of interior British Columbia, but his data seem confusing. On the one hand, he reports that the inland tribes of the province suffered much less from the early epidemics than the coastal groups. On the other hand, he observes that the great 1781-1782 smallpox epidemic was very destructive throughout British Columbia and that the tribes of the region were "greatly reduced by repeated visitations of smallpox and other epidemics, of which the most destructive was the smallpox epidemic which swept the Fraser River country and northward along the coast in 1802" (Mooney 1928:27). He does not state that this 1802 scourge moved up the Fraser River as far as the Thompson, but he appears to imply as much. If this is his meaning, the interior Fraser groups must have been hit badly by these pestilences, though still conceivably not as severely as the coastal peoples. And further, if this is his meaning, then Teit's data holding that the real depopulation began in the 1850s (see later paragraph) requires modification. In any event, Mooney's (1928:29) estimate for the Thompson population (Upper and Lower Divisions together) in 1780 is 5,000 persons.

In light of Mooney's largely reconstructive data, a journal entry by Fraser (1960:94) is of more than casual interest. On the evening of June 24, 1808, he encamped in a Lower Thompson village within Fraser Canyon and observed that smallpox "was in the [Indian] camp, and several of the Natives were marked with it." This seems to clinch the proposition that smallpox climbed the Fraser River at least as far as the Lower Thompson by the early 1800s, for it is improbable that all of these "several" Indians would have been visitors from downriver, where the testimony is conclusive as to the earlier arrival of the disease. Negative evidence is always suspect but it is of moderate interest that Fraser makes no mention of the ailment in his contacts with Indian groups farther up the Fraser either when descending or later when ascending the river.

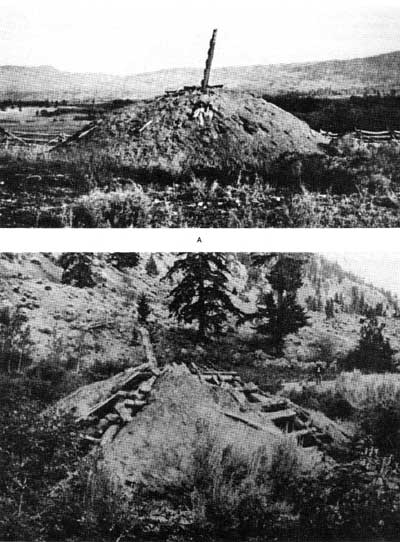

Teit's (1900:175) ethnographic information is in agreement concerning the frightful effects of disease on the Thompson people in the 1800s, but indicates that the initial appearance of epidemics differed notably between the Lower and Upper Divisions. Specifically, he writes that his native Thompson informants and Whites already long residents in the area in the 1890s both affirmed that the Thompson in the late 1800s were "greatly reduced in numbers." The existence in the 1890s of numerous ruins of underground dwellings is not in themselves acceptable evidence for depopulation: single families often constructed several such houses and, after the first smallpox epidemic, many survivors moved from small villages to larger communities and constricted new dwellings there. Nevertheless:

The old people say [for the Upper Thompson] that forty or fifty years ago [i.e., 1850s], when travelling along Thompson River, the smoke of Indian camp-fires was always in view. This will be better understood when it is noted that the course of Thompson River is very tortuous, and that in many places one can see but a very short distance up or down the river. The old Indians compare the number of people formerly living in the vicinity of Lytton to "ants about an ant-hill." Although they cannot state the number of inhabitants forty years ago, there are still old men living who can give approximately the number of summer lodges or winter houses along Thompson River at that time, showing clearly the great decrease which has taken place. (Teit 1900:175)

With reference to the Lower Thompson specifically:

In 1858 when white miners first arrived in the country, the Indian population between Spuzzum and Lytton was estimated at not less than two thousand, while at present it is probably not over seven hundred. If that be correct, and assuming that the number in the upper part of the tribe was in about the same proportion to those in the lower as now [c. 1897], the population of the entire tribe would have numbered [in the 1850s] at least five thousand. (Teit 1900:175)

This estimate should be seen in the context of the fact that, according to Teit (1900:175), about 1856 the tribe had been depopulated by a devastating famine that struck nearly the entire interior of British Columbia. Still, in Teit's judgment, the significant decrease in the Upper Thompson population occurred only after 1858 or 1859 when the Whites first arrived in numbers. Or, as Teit (1930b:212-213) explains the situation more precisely in a later publication: "It appears that the ... Thompson escaped all the epidemics until 1857 and 1862."

The situation, again from Teit's evidence, was apparently rather different among the Lower Thompson. While smallpox was said by his informants to have struck the Upper Thompson only once in their memory, it reached the Lower Thompson three or four times, first near the beginning of the 1800s. This disease was the most important cause of their depopulation during the nineteenth century. The 1863 epidemic, for example, must have carried off between one-third and one-fourth of the population, Teit's Lower Division informants asserted. Many people fled to the mountains for safety and dropped dead on the trail; others attempted to survive by retiring to their sweathouses, only to die within their walls. (Teit 1900:176) These data regarding the appearance of smallpox among the Lower Thompson very early in the nineteenth century, before it reached the Upper bands, is reassuringly consistent with Fraser's comments and the implications of his narrative for more upriver areas as noted above.

On its face, the extraordinary difference in the epidemic history of the Upper and Lower Thompson as reported by Teit seems improbable. White trade goods were observed by Fraser in 1808 among both the Upper and the Lower groups. Items of trade of coastal origin reached both Divisions through intermediary tribes. And the Upper and Lower villages were in constant contact, although the relationship was not as close as between many friendly neighboring tribes elsewhere owing to the difficulties of moving about within the Fraser Canyon. If the Lower Division smallpox situation is properly described -- at least Fraser's data seem straightforward enough -- it would be remarkable if the Upper people escaped the disease until the 1850s.

Physical Characteristics

In the early and middle 1890s Boas (1895:524-551) collected a series of anthropometric data among the Indian groups of the northern Pacific coastal area and the adjacent interior, including measurements on members of the two Thompson Divisions who appeared to have minimal White admixture. In his analysis of these Thompson data, the figures for the Lower Thompson were kept separate from those of the Upper bands. Averages were computed for the various physical features measured, sensibly regarded by Boas not as defining a "typical" person but merely as approximations useful in intergroup comparisons. As he observes, they turned out to be surprising for their geographical regularity: e.g., from the exceedingly short Harrison Lake people the stature increased tribe by tribe in all directions, irrespective of subsistence base and substantial variations in cultural configuration, suggesting a very stable population over a large region.

A detailed comparison of the Lower Thompson data with the comparable figures for other groups would be out of place in this report. But the measurements for this Division and their relationship with those for the Upper Thompson may be summarized. The average stature of the Lower males of Spuzzum village was 160.5 cm (63.2 in) and of those of the villages farther upstream was 161.0 cm (63.4 in). The stature figure for the Upper Thompson band on the Fraser and lower Thompson River in the Lytton region was 162.7 cm (64.1 in) and for the band still farther up the Thompson was 165.7 cm (65.2 in). The comparable stature averages for females in these four groups was somewhat lower in each instance as would be anticipated. (Boas 1895:524, 530, 531)

Similar average figures are recorded by Boas (1895:533-538) for both men and women for head length and breadth, facial height and breadth, and nasal height and breadth. "Indexes" are computed for head, face, and nose, revealing the proportion of the smaller measurement in each pair to the larger measurement. These are technical details which can be best summarized descriptively.

The Thompson -- Lower and Upper Divisions together -- proved to be generally intermediate in these measurements and indices between an Interior Salish -- and Sahaptian -- type (represented by the Flathead, Okanagan, and Shuswap over the interior of northwestern Montana, northern Idaho, interior Washington, and southern interior British Columbia) and the Harrison Lake type (to the west). From this fact, Boas (1895:544) saw the Thompson as essentially a mixture of these two types, the conventional way of interpreting anthropometric distributional data of this sort in Boas' time.

More descriptively, the Thompson were considerably darker in skin color than the Indians of the neighboring coast, their heads were narrower (though still broad), their faces were lower and narrower than among their neighbors, and their noses were broader. The most interesting point, however, to emerge from their field data is that the Upper and Lower Thompson were physically notably different from one another in spite of the similarity of much of their fundamental culture, their essential linguistic unity, and the view of the two divisions themselves that they comprised a single tribal entity. The Lower people resembled more the Harrison Lake type; the Upper folk looked more like the Shuswap and Okanagan. But even more intriguing from Boas anthropomorphic records is the fact that the Upper Thompson band of the lower Thompson Valley presented peculiarities of their own, which may represent a retention of their archaic physical traits or "may be due to admixture of Tinneh blood" (Boas 1895:549). These "Tinneh" were the Athapascan groups, presumably in this instance the Nicola of the Nicola and Similkameen Valleys and perhaps to some extent the Chilcotin and Carrier to the north of the Lillooet and Shuswap.

While obviously not biological characteristics in the above sense, it is of some interest to note Teit's (1900:180-181) assessment of the "mental traits," as he terms them, of the Lower Thompson. In brief, at least in the 1890s the members of this group were "quieter and steadier than the people of the upper division, but at the same time they seem[ed] to be slower and less energetic. They . . . [were] better fishermen and more expert in handling canoes, while the Upper Thompson . . . [were] better horsemen."

The behavioral differences noted by Teit appear consistent with the different cultural bases of the two divisions -- largely fishing in the first instance, and hunting and more roving in the second -- and with the kinds of personality emphasis that might be logically encouraged by these different lifeways.

| SUBSISTENCE |

The staples of the Lower Thompson were salmon -- the principal food -- with deer, roots, and berries as important but supplementary foods (cf. Simpson 1947:33, 38). According to Teit (1900:230), undoubtedly speaking primarily of the Upper Thompson, many people lived in the mountains much of the year, moving about seasonally from one deer-feeding, root, or berry ground to another. The men trapped and hunted while the women gathered and prepared the plant foods. Only when cold weather arrived did they return to their winter dwellings. This, however, was obviously not the pattern for many -- possibly most -- Lower Thompson families with their fine salmon fisheries in the Fraser canyon. Nevertheless, it would be most surprising if some of these families, either by preference or because they had no ready access to salmon sites, failed to follow this seasonal routine. And still others, though fishing during the principal runs, must have gone to the hills outside the canyon for game and vegetable foods at other times, as the lists of foods obtained by the group compiled in the paragraphs that follow demonstrate. It must have been just such parties of Lower Thompson that sought elk and deer in the Tulameen region and food resources down in the Skagit River country of the North Cascades Park.

In his journal of June, 1808, Simon Fraser makes a point of considerable comparative interest. As soon as he, on his voyage of exploration down the Fraser River, entered the country of the Lower Thompson (his "Nailgemugh") he observed that this group was "better supplied with the necessaries of life than any of those we have hitherto seen" (Fraser 1960:94), comparing them with the Lillooet and Upper Thompson people farther upstream. These "necessaries" surely including food, it is worth noting that at various villages within the canyon he and his party received edibles, generally "in abundance," to satisfy their subsistence needs. Mentioned specifically on one or more occasions are fresh salmon (boiled or roasted), dried fish, green and dried berries, wild onions, hazel nuts and other nuts of excellent quality (Fraser 1960:94, 97,116,117,118).

Fishing

Salmon of five varieties were the principal food secured by the Lower Thompson. Trout and "fish of many [other] kinds" were taken especially in spring and autumn. Owing, however, to the special physical conditions of their canyon stretch of the Fraser, the Lower Thompson caught plenty of salmon even in years when the fish were comparatively scarce. Consequently, they cured only the finest fish: the chinook, from which much oil was obtained, was considered the best. (Teit 1900:230-231, 251)

Agreeing with Teit on the primary importance of chinook salmon and the lesser importance of trout among the Lower Thompson, Ray (1942:104) provides further data on the other varieties of fish to which Teit alludes. In addition to trout, of some significance in the diet were salmon trout, sturgeon, suckers, and eels. On the other hand, steelhead trout, though available, were unimportant, and dog salmon and whitefish were unknown in Lower Division country -- at least within the canyon.

Women participated in all fishing activities, except the actual spearing process (Teit 1900:115).

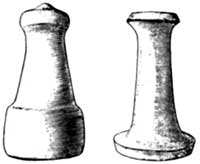

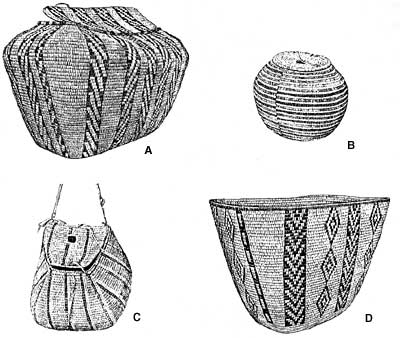

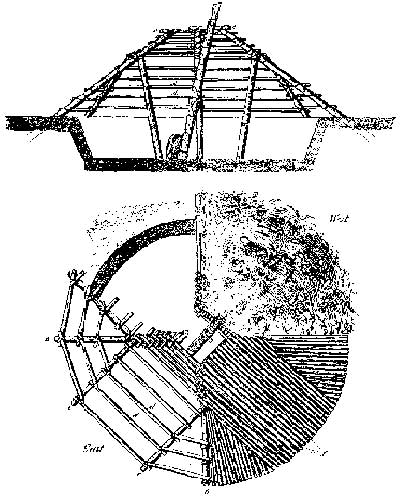

Figure 3-2. Thompson bag-net (Teit 1900:250 Figure 230).

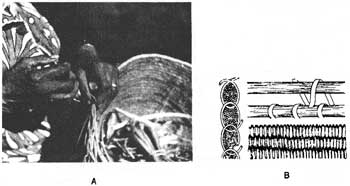

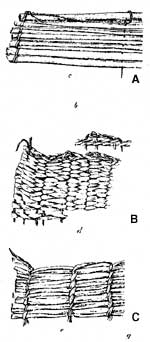

Salmon and other large fish were taken with bag-nets (Figure 3-2). The Indian-hemp net was attached to small horn rings that slid along a fir or cedar hoop. This hoop was fixed to a long wooden handle. A string ran from the net to the fisherman's hand. When a fish entered the net, the man released the string and the weight of the fish closed the mouth of the net by sliding it along the wooden hoop. The fish, clubbed or with its neck broken, was placed in a pit previously made nearby by cleaning away the boulders to leave a sandy or gravel surface encircled by the stones. (Ray 1942:109; Teit 1900:249-250)

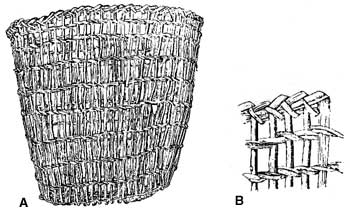

Long drag nets, with wooden floats and stone sinkers, were set in lakes and river pools overnight and hauled into canoes in the morning (Teit 1900:250). Presumably it is to these nets that Ray (1942:108-109) refers in reporting that Lower Thompson seines were netted of Indian hemp cordage to a length of as much as 60 feet. These were attached to end sticks, and were, as Teit states, sometimes provided with wooden floats and bottom weights and were emptied into canoes.

Salmon were caught in dip nets from platforms built out over the river where the fish, attempting to ascend the fast water, came close to the bank. Stakes were driven into the stream about 3 yards upstream from the platform, if the water was clear, to make it rough and foamy and so to conceal the net. The net was drawn downstream at intervals. This fishing method was especially suited to the Lower Thompson territory in the Fraser canyon, where the very rapid water compelled the fish to hug the banks, the water was typically muddy, many low rocks projected into the river making natural fine dip-net sites, and the fish, only recently from the sea, were superior. Because of the many rocks in their canyon from which to fish, the Lower Thompson fashioned these platforms less frequently than did the Upper Thompson. On the other hand, their bag-nets often had to have very long handles. (Hill-Tout 1900:509-510; Teit 1900:250-251)

The dip nets of the above scoop type, Ray (1942:109-110) explains, were suspended from a circular hoop attached to an A-frame, single-pole handle. The nets themselves were united to the hoop with horn or occasionally maple slip-rings, thus constructed like the bag nets described by Teit in an earlier paragraph. They were used from platforms both for salmon and for smaller fish.

On June 25,1808, Simon Fraser (1960:95), descending the Fraser River on his journey of exploration, saw a Lower Thompson man "on the opposite side [of the river] fishing Salmon with a dipping net." Details concerning its construction and use are not furnished.

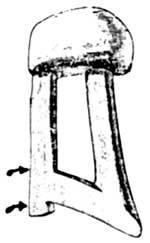

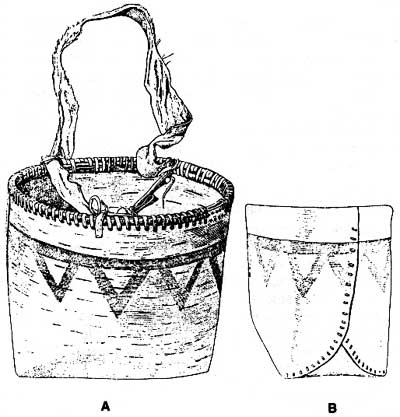

Fish, when running, were also taken by the Thompson from the bank with a spear made with a two-pronged point, each bearing a detachable tip with a barb directed inward (Figure 3-3). Each tip was attached to the handle by a line so it could come loose from the handle when the fish was struck. A spear with a single barbed point, sometimes detachable, was also used particularly for large trout from rocks on the river bank or from canoes at night with the aid of torchlight. These canoes were operated by a four-man team, each man wearing eyeshades: one in the stern to keep the craft drifting broadside down the stream; one in the center holding the torch; and one on each side of the torch-man to attend to the spearing. This method was seldom used by the Lower Thompson because of the muddy condition of the river in their country. (Hill-Tout 1900:510; Ray 1942:112-113; Teit 1900:251-252)

Figure 3-3. Thompson fish spear with detachable points

(Teit 1900:251 Figure 231).

A three-pronged spear, with two nondetachable wooden side points each armed with inside mountain-goat horn barbs, was also a Lower Thompson fishing device though it was not of great importance (Figure 3-4). It was used both for salmon and for smaller fish, largely in night torch fishing from river banks, from canoes, and in winter out on the ice. (Ray 1942:113)

Figure 3-4. Thompson three-pronged fish spear (Teit

1900:252 Figure 232).

Fish were speared or taken with hook and line through holes in the ice, though not often by the Lower Thompson (Ray 1942:110; Teit 1900:252-253). Hook and line angling was also practiced to some extent in warmer seasons.

Small sturgeon were taken by the Lower Thompson in the Fraser River with hook and line, both from the banks and from canoes. The hook of bone, large and heavy, was attached to a wooden shank and it, in turn, to a heavy bark line as much as 100 yards long. A stone sinker was fastened to the line about five feet above the hook. Salmon tail was the usual bait. (Teit 1900:253)

Among the Lower Thompson, hook and line fishing was practiced by boys for trout in a few creeks and by men for trout in mountain lakes when camped nearby hunting and digging roots. Salmon trout were taken with stout hooks, also baited with salmon tails, and Indian hemp lines with a stone sinker tied a few feet above the hook. The line was coiled and thrown out into the stream as far as possible and then hauled in to attract the fish. (Teit 1900:253-254)

Ray (1942:110-112) also reports the Lower Thompson use of small hooks, fashioned of two pieces of bone with a wooden shank and a sinker, for small fish and eels. Double-pointed, bone gorgets were likewise used for these minor fish. Worms, ant larvae, grasshoppers, fish eggs, and even squirrel meat served as bait.

Weirs of stakes lashed together were built by the Thompson in shallow streams to catch salmon. These stopped the fish in large numbers, allowing them to be speared. Traps were fashioned like a stick box or were a woven willow basket in cylindrical shape. The Lower Thompson, Teit (1900:254) remarks, rarely made use of either weirs or traps; Ray (1942:104-108) goes further: according to his data this downstream group made no use whatever of weirs, traps, or fish dams of any kind. The slight difference in these two statements is suggestive. It is conceivable that Teit was aware of the occasional employment of these devices by subsistence task parties in the higher elevations out of the canyon, concerning which Ray's informant appears to have been largely silent. Through the 1800s the Lower Thompson became increasingly more sedentary, a life pattern shift substantially less true of the Upper Thompson (Teit 1930b:216). Inasmuch as Teit secured his ethnographic data in the 1890s while Ray gathered his in the 1930s, it is reasonable to assume that the latter's informant was less likely to remember those activities of his Division that occurred outside the Fraser Canyon boundary when the group as a whole were following a freer and more mobile life style.

Salmon, among the Thompson, were slit along the belly with a knife with a curved stone blade and short handle, and the entrails and blood were removed. The backbone was separated but left attached to the flesh. When the flesh had been deeply scored, the fish was stretched and kept open with thin cross-sticks. It was then hung over a long pole to dry, backbone on one side and flesh on the other. About a hundred fish could be suspended from a single pole. (Teit 1900:234)

The Lower Thompson salmon preparation technique was slightly different as described by Ray and Hill-Tout -- or perhaps these differences were not group pattern distinctions but nothing more than variations at the level of individual women or villages, or in ways of handling fish at different seasons or under different weather conditions or according to the food to be prepared from the fish, or some other similar variable. At any rate, Ray (1942:135) reports that the Lower Thompson split the fish dorsally. Hill-Tout (1900:510) states that the women stood by to receive freshly taken salmon and at once killed them with a blow to the head, cut them open along the belly (as Teit reported above) with a knife of meat-chopper shape, wrenched off the head, removed the backbone (as Teit states was not the case), spread the two halves, and hung the fish to dry in an open, pole shed nearby on the river bank.

Once dry and hard, the salmon were removed from the drying pole, piled in heaps, and carried by the Lower Thompson for storage to the elevated wooden caches where they remained all winter. In the spring they were removed and placed in pit caches. The following spring they were taken out and aired, only perhaps to be returned to the caches for another year. In this way a reserve supply of salmon was kept for two or three years by most families for emergencies. Salmon heads were also dried and stored. Wrapped in dry grass or bark, salmon roe was buried until nearly rotten; roasted or boiled when later removed, the roe tasted rather like cheese. Salmon eggs were also dried by the Lower Thompson and buried in bark-lined pits. Salmon and large trout tails were roasted before a fire until crisp. (Ray 1942:135; Teit 1900:234-235, 236)

To make salmon oil, a number of fat salmon were placed in a pit, about 3 or 4 feet square and 2 feet deep, lined with stone slabs with cracks plastered with mud. Water was added and heated stones thrown in. Later the boiling mass was broken up and stirred with a stick. It was kept simmering until all the oil had been extracted. As the mixture cooled, the oil floated to the surface and was skimmed off and put in dried salmon-skin bags tied at each end. The boiled salmon flesh that remained was removed, squeezed, and put in baskets to be eaten at once or dried into cakes for later use. (Teit 1900:235)

The process of oil extraction is also described by Hill-Tout (1900:510-511), obviously from having witnessed the process. Although very similar in essentials to Teit's account, it differs in certain details and adds enough new information to warrant summary. Forty or fifty fish, he writes, were placed in a large trough hollowed out from a tree trunk with fire and adz. When rotten, the mass was covered with water; heated stones were put in; and the mixture was stirred to a hot pulp. The stones were removed and a small amount of cold water was added to cause the reddish oil to rise to the surface. This oil was skimmed off into birch-bark vessels with a spoon of wood or bighorn sheep horn. After standing overnight, the oil was reboiled and skimmed until quite clear. It was stored in bags made by peeling the skin from a whole salmon "as one draws off a tight-fitting glove," cleaning it with dry punk-wood, and rubbing it with deer or bighorn sheep suet. Turned right-side out again, the bags were filled with the oil and their mouths were fastened.

The salmon flesh remaining in the trough, to continue Hill-Tout's description, was kneeded into balls and sun-dried. Later it was squeezed, washed, rekneeded, and again dried. When quite dry and odorless, it was broken up and rubbed fine between the hands until like flour. Some of this flour was placed in the bottom of a birch-bark basket and on it was laid the skin sacks of oil. When the basket was filled with these bags, more salmon flour was spread over the top and down the sides, burying the bags. This food was stored for winter eating. (Hill-Tout 1900:511)

A kind of "butter" was also made as a great delicacy by boiling salmon oil with deer or, better, bighorn sheep kidney suet, thoroughly mixing the substance, and allowing it to cool, when it assumed the consistency of butter. This "butter" was eaten with compressed cakes of serviceberries or other berries. (Hill-Tout 1900:511)

The Lower Thompson celebrated the appearance of the first few chinook salmon with a special ritual. It was led by the village chief; the ceremonial position of "salmon chief" so important in other tribes did not exist among these Fraser Canyon people. The fish were prepared by the women and were eaten by men, women, and children, which was generally not the case elsewhere. It was considered important for the future salmon run for all of the fish and fish soup to be consumed on this occasion. (Ray 1942:115-116)

A rather more extended description of the first salmon ceremony of the Upper Thompson is given by Hill-Tout (1900:504), though not without, it appears, some considerable overformalization of the social and political structure, at least as it existed in traditional and early postcontact times. To summarize his account: When the salmon began to run, the "divisional chiefs" were informed. Messengers were sent to neighboring villages, calling on all people to attend the first salmon rite on an appointed day. When the day arrived and the people had assembled, the "head chief," attended by "lesser ones and the elders," initiated the ceremony with a long prayer. On its conclusion, everyone in attendance was given a bit of salmon specially cooked for this rite. When these pieces had been eaten ceremonially, all were permitted to eat as much as they wished. Singing and dancing in a circle followed, with hands held extended palms upward as in supplication. This same dance was performed again at noon and at sunset. This account tells us a bit about the ceremony, but more importantly it illustrates the cautions to be exercised in the use of much of Hill-Tout's data relating to the less material aspects of traditional Thompson culture.

Shellfish were considerable inedible: they were in fact abhorred (Teit 1900:348).

There is considerable ethnographic interest at present in the extent to which native hunting-gathering groups took positive action to maintain and even increase the food and other essential resources of their natural environment. In this context it is notable that the Thompson in traditional days followed the practice of taking live trout from lakes and streams and transplanting them into lakes where there were none. Sometimes these fish propagated and became plentiful. (Teit 1900:348)

Hunting

The ethnographic data on hunting are rich and can only be summarized in this section.

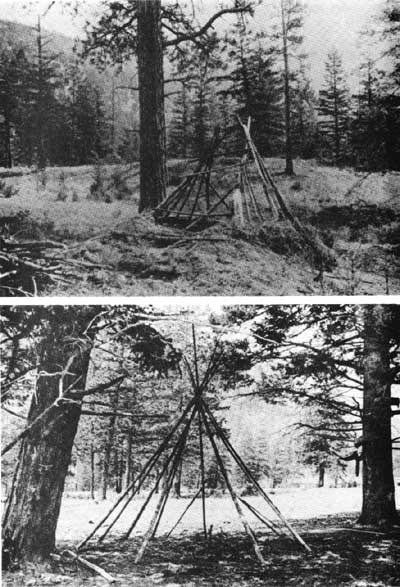

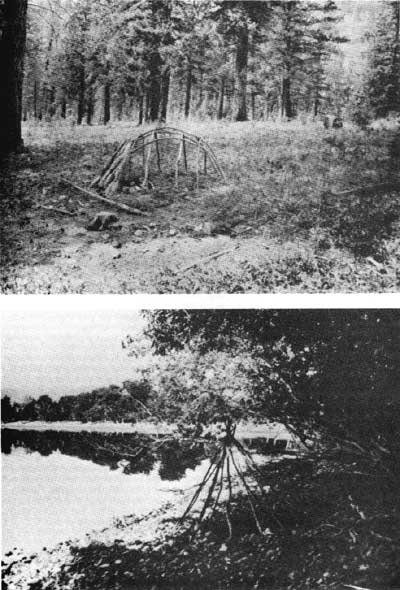

Although the Lower Thompson had an abundance of fish, they "spent much time in hunting," considerably less, however, than the Upper Thompson. "They even hunted," Teit (1900:239) writes of high relevance to this present study, "on the mountains on the western slope of the Coast Range. Hunting-parties who visited the most southern part of their hunting-grounds were sometimes absent for seven months, returning only when the snow began to melt in the mountains." Apparently these southernmost grounds were those in the Skagit country north of the Canadian line and even south in the Ross Lake region, though Teit fails to locate them with this precision. They must, however, have fallen within the Lower Thompson tribal boundaries as these are demarcated on his territorial map (Figure 3-1). This is nicely confirmed by Teit's (1930b:257) subsequent data that the Lower Thompson hunted in the Cascades back of Hope and Chilliwack (i.e., in the Skagit country north of the Canadian border) where they met friendly Nicola hunting groups. And that they hunted and raided even "a long way [farther] south along the Cascades" (i.e., south of the international boundary in the Ross Lake Skagit region).

Skilled hunters among the Lower Thompson (no less than in the Upper Thompson bands) were esteemed. In fact, there were even men who specialized in hunting in spite of the great importance of salmon fishing to the group. (Ray 1942:123)

Before going out in search of game, a Lower Thompson hunter was expected to remain continent for a time. Sometimes he sweated in his sweat house, though this was not regarded as very important. Before actually leaving the village or camp, however, he customarily bathed in a somewhat ritual fashion. Apparently his wife was under no ritual behavioral restrictions. Nor were there prescriptions on how a deer was to be butchered, handled, cooked, eaten, and the bones disposed of, as was the case among many not distant tribes. In a group hunt, the meat was divided equally among the hunters. (Ray 1942:123,127-129)

Deer, elk, bighorn sheep, beaver, porcupine, hare (rabbit), and squirrels were secured in abundance by the Thompson, according to Teit (1900:230), and to a lesser degree lynx and coyote. The principal game of the Lower Thompson was mountain goat, black bear, and marmot. This Lower group also ate rock-rabbit, which the Upper people did not regard as proper food. Ray's (1942:46) roster differs in several details. Deer, he writes, were the most important game of the downstream division; black and grizzly bear and mountain goat were also hunted; bighorn sheep were occasionally secured; elk were of minimal significance. The points of noncorrespondence between the Teit and Ray lists are of particular interest in terms of this present study. Teit's catalog appears to indicate a widespread and significant use of the mountain hunting grounds away from the Fraser Canyon fishing and winter villages. On the other hand, Ray's listing, except for the mountain goat, suggests a primary focus upon hunting in the Fraser Valley and immediately adjacent higher areas. One might sensibly conclude that in the period between Teit's research and the field efforts of Ray, memory of hunting in the tall mountains, including especially those in the upper Skagit sector, had evidently faded significantly.

A number of animals mentioned elsewhere in this study as having been taken by the Thompson generally for various secondary purposes -- like clothing or ornamentation -- are missing from the above two lists. Among these are the cougar, fox, wolf, wolverine, and ermine. Presumably these essentially unimportant animals were also secured at times by Lower Thompson hunters. At any rate, they were not truly "game" or subsistence animals, those with which the above catalogs are basically concerned.

Birds -- particularly geese, ducks, and swans but also some land birds like grouse -- were hunted for their flesh. Others were sought for their feathers. The tail feathers of the golden eagle were highly valued, used for decorating headgear, hair, and weapons; those of the chicken-hawk were considered second best as adornment materials. (Ray 1942:117, 120; Teit 1900:367)

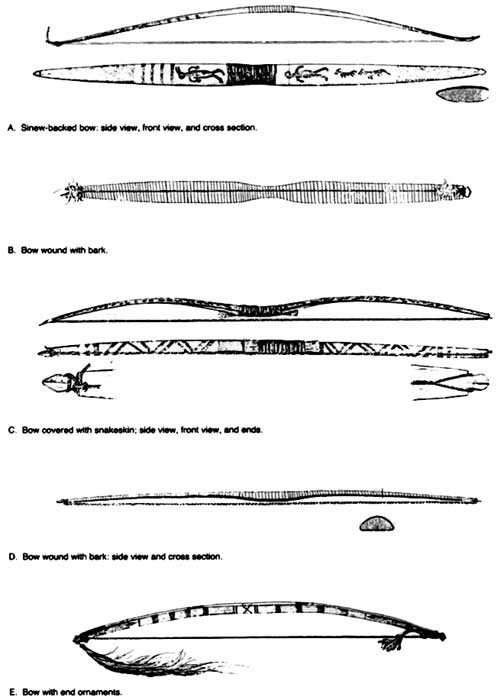

Bows and arrows were the principal hunting weapons (Figure 3-5). Among the Lower Thompson bows, narrow and 3 feet or somewhat more in length, were fashioned of hemlock, yew, syringa, serviceberry, or dogwood. In cross-section they were flat on the inside and rounded on the face away from the hunter. Better ones had glued to the face a layer of deer sinew to strengthen and increase the resiliency of the weapon, the glue of salmon skin. The center hand-grip was narrowed and wrapped with bird-cherry bark. The ends were recurved, notched, and sinew-wrapped. The string was of deer back-sinew, sometimes placed along the center line of the bow and sometimes to one side, or, when sinew was unavailable, was of Indian hemp. The entire bow was at times covered with snakeskin. Some bows were not given the sinew backing: e.g., those used in light shooting of birds and small game. The inner face of bows was often incised with designs filled with red paint, or adorned with dyed porcupine quill work, or fitted with red-headed woodpecker scalps at their tips. (Ray 1942:148-149; Teit 1900:239-241)

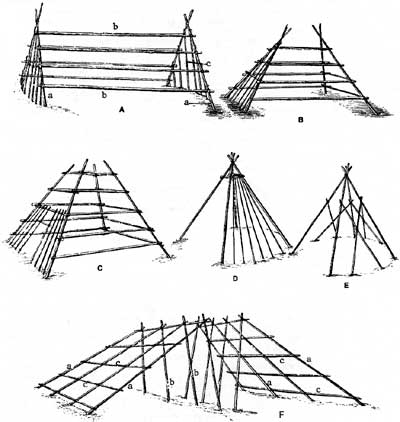

Figure 3-5. Five Thompson bow varieties (Teit 1900:240 Figures 216-220).

Arrows, of serviceberry or hawthorn wood or rosewood, were soaked in warm water, straightened with the teeth or over the knee, and polished with scouring rush or a sandstone shaft smoother. They were fitted with hawk, grouse, and sometimes eagle feathers: two or three split feathers attached spirally with deer sinew and pitch or with two whole feathers laid on flat. The Lower Thompson found stone for their arrow points near the headwaters of the Skagit River. Many points in traditional times were reflaked from the large points of earlier and unknown origin which the Lower Thompson found "in great numbers in the valleys." Hunting arrow points, of stone, were leaf-shaped and were fitted to the shaft at right angles to the nock. For small game the end of the arrow shaft was simply sharpened, and sometimes cut into barbs; some had detachable heads tied to the shaft with string. Bird arrows were blunt-headed. Arrows were often ornamented with simple painted patterns or branded with animal figures. War arrows bore barbed bone points that were detachable and "poisoned" with vegetable material or with rattlesnake venom. (Ray 1942:149-151; Teit 1900:241-243)

Quivers were of tanned deer skin, fringed and painted, or of "uncut hides" of coyote or wolverine, arranged so the tail hung down, or they were woven of sagebrush fibers. Some were fitted with small pouches to hold the fire drill and tinder. (Ray 1942:151-152; Teit 1900: 243-244)

Bows were ordinarily held horizontally in the shooting (Ray 1942:149; Teit 1900:241)

Every Thompson man had the right to hunt wherever he chose within the traditional tribal limits. There was no ownership of particular hunting grounds by band, villages, or families. As a practical matter, each band usually took its game in areas nearest its respective home villages, yet men frequently hunted, without being considered intruders, in sectors that were technically under the control of other villages or bands. (Teit 1900:293)

Most of our hunting information describes methods used in taking deer, the most important game among the Upper Division. Among the techniques employed were the following.

Deer were generally hunted with the bow and arrow, with dogs providing valuable assistance. When dogs were to be used, they were tied up for several days before the hunt, fed sparingly on good food, and sometimes even purged with medicines and sweat bathed. In one of the simplest procedures in which these animals were employed, the hunter left before daybreak -- perhaps carrying a few serviceberries to eat if he later felt exhausted -- with his dogs on halters. On seeing the tracks of some large buck, he freed his dogs to run the animals down and followed them as rapidly as possible. The dogs generally drove the deer to a stream, where, particularly in autumn, men in canoes were waiting to pursue the animal in the water and, with a stick with an end crook, to catch the antlers and force the head under the surface. When drowned, the deer was pulled ashore, skinned, and butchered. Often the dogs brought the deer to bay at a creek until the hunter arrived to dispatch it. (Hill-Tout 1900:508; Teit 1900:244-245)

During the rutting season and in winter after the deer had come down from the hills, the Upper Thompson -- and one may suppose the Lower Thompson also -- lay in wait for the animals at night at their regular swimming places. In summer both Upper and Lower Thompson hunters shot them by moonlight at their salt licks or drinking sites, the men having concealed themselves in shallow pits screened with bushes. (Ray 1942:117; Teit 1900:245)

To some degree -- though to a lesser extent than among the Upper Thompson -- the Lower Division took deer with a rough deer fence. At one time these fences were very numerous, even up in the mountains. Some were for summer use, but most were for taking the animals in the fall and early winter in little valleys or defiles between the mountains and where the deer gathered when descending the mountains to their winter grounds. These fences, seldom over 4 or 4.5 feet high, were constructed of poles, tree limbs, and the like placed close enough together to impede the animal's progress. They were sometimes more than a mile long. Every 100 yards or so, an obvious opening was left. In this was dug a shallow pit, over which sticks were placed to support a bark-string snare attached to a strong spring pole. On the ground nearby a log was laid so as to force the animals, in stepping over it, to place its foot in the noose. With its leg caught, the animal was jerked off the ground. This was a very successful hunting method, but curiously not much used by the Lower Thompson. (Hill-Tout 1900:508; Ray 1942:44; Teit 1900:246-247)

The Lower Thompson also set nooses on deer trails to catch the animal's head or antlers (Teit 1900:247).

Drives for deer were carried out by two or three men or even a much larger group. Walking a hundred or more yards from each other, they forced the animals ahead where they could be shot by concealed hunters. This method was especially successful in winter in gulches where the animals tended to yard. If the number of men was large, the hunt was directed by an especially experienced man who knew the ground well. If men were scarce, women and boys assisted in the drive task. Sometimes a large number of deer were killed. Generally the oldest hunter divided the game, each deer being cut into nine pieces. In a fat buck, the best part of the animal was considered to be "the fleshy and fatty part of the body between the skin and the bones." (Teit 1900:247-248) As Teit intimates, Ray (1942:117) reports that group drives were also organized to some degree in warm weather. These were under the direction of any good hunter (confirming Teit's statement), who assigned individual areas to the several men. The game was driven into water.

Deer were also caught in large mesh, Indian hemp nets, about 7 feet high and up to 200 yards long. These were set in the evening between clumps of bushes to form a corral open at one side on a deer trail. Generally some deer were found in the corral in the morning, unable to find their way out. (Teit 1900:248)

To be successful in taking deer as a lone Thompson hunter required close knowledge of the animals' habits and of the places frequented by them according to the season, and an ability to take advantage of cover, to track, and to shoot well. Sometimes single hunters in the mountains experienced much hardship and exposure.

Some of them would start out with cold weather in the winter-time, taking with them neither food nor other clothing than that which they wore. They lived entirely on what they shot, and used the raw deerskins for blankets. They made rough kettles of spruce-bark or deer's paunches. A hole was dug in the soft ground near the fire, into which the kettle was placed, with brush underneath. The open end was made small and stiff by means of a stick threaded through it around the edge; and the sides of the open end were sometimes fastened with bark to one or two cross-sticks which lay on the ground across the opening. Hot stones were put in to boil the food. These paunches were also sometimes used as water-pails. (Teit 1900:246)

In deep snow in the mountains deer and elk were run down by Thompson hunters on snowshoes and were shot or clubbed to death. They were also run down by dogs when the snow lay deeply on the ground and the crust was thick. Elk were driven over cliffs by large groups of men. Black bear were generally killed with the bow and arrow, sometimes with the aid of dogs, but they were also taken in deadfall traps. Male black bears could be hunted over a longer season than the females: the latter denned up when the leaves began to fall in autumn, while the males entered their winter quarters much later. Grizzlies were hunted by many younger men because of the great prestige afforded one who had killed such an animal single-handed. According to the Thompson, they were much less fierce in some parts of the country than in others. Tradition tells of a particularly courageous hunter of the mid-i 800s who is said to have hunted them by thrusting a double-pointed bone vertically in the animal's open mouth when it charged and then killing it with a stone club while it was desperately attempting to dislodge the bone upon which it had shut its jaws. Mountain goats and bighorn sheep were killed with bow and arrows. Beaver were sometimes taken with the aid of dogs and dispatched with a bone-tipped spear. Coyotes and foxes were dug or smoked out of their dens. Hares, squirrels, and grouse were shot with the bow and arrow or were caught in spring-pole snares of Indian hemp, set over their runs. (Teit 1900:248-249, 373)

With some explicit exceptions, the data of the preceding paragraphs describe hunting practices of the Thompson as a tribe and those of the Upper bands in particular. The extent to which they also apply to the Lower Division is not reported by Teit, though it may be assumed that most of these techniques, if not all, were likewise those of this downstream division on occasion. While the Upper people were plainly more generally hunting-oriented, Lower Thompson parties spent months pursuing game in the higher sectors of their territory and, as already observed, specialist hunters even existed within the division. Fortunately Ray (1942:116-124) provides hunting information for these downstream people specifically. I see no simple way of combining most of these data with those of Teit above without thoroughly muddying the description. The following summarizes this Ray residue material.

For the Lower Thompson Ray (1942:117-123,140) confirms the running down of animals on snow by men wearing snowshoes, the stalking of them with bow and arrows and occasionally with clubs, the taking of grizzlies by daringly placing a sharpened bone in their mouth, and the use of trained dogs in hunting deer and bear. He also reports certain fresh data. Deer and elk were called with whistles of elderberry wood and cottonwood wood and by blowing upon a leaf placed in the mouth. Hunters are reported to have crawled into a hibernating bear's hole, tied a rope around its neck, and dragged it out. Hibernating ground hogs and perhaps bears likewise were occasionally smoked out of their dens. Beaver were ritually spoken to and called out of their houses. If this strategem failed, their dams were destroyed and the animals were clubbed in their effort to escape, or the hunter crawled into the house to capture the animals. Their musk was taken for perfume and their kidney for medicine. Deer, mountain goats, and birds were all caught in spring-pole snares. For deer the nooses were suspended from tree limbs on trails and were also set at openings in fences. For grouse the Indian hemp snares were placed on their trails, at their "dancing" grounds, on logs, on top of knolls, and in openings in stone or brush fences. Baited deadfalls were constructed for large and small game. Eagles were attracted to a brush hut by fish bait and were taken by hand by the hunter concealed within the hut. Young eagles were also captured in their nest. Birds' eggs were collected by the Lower Thompson and were boiled for food.

Among the Lower Thompson, the hunting leader divided the fat, meat, and skins almost equally among the entire party, only the best hunters being given a little more fat and an extra skin or two. A single hunter who chanced to have especially good fortune returned to his village and invited his friends to help him carry his kill home and share in the meat and hides. Skins and meat of trapped animals belonged exclusively to the trapper. (Teit 1900:264-265)

How meat was prepared for immediate eating is not well described in the ethnographic accounts. Roasting before an open fire and stone-boiling were, however, common methods.

For later consumption the flesh, with fat removed, was cut into thin slices, pierced with holes or slits, and dried by sun and wind on a pole framework, often over a fire. Sometimes it was dried and smoked over the lodge fire or hung up near the roof to receive this treatment. Chunks of fat cut from deer, elk, or bear meat were run through with thin sticks, the ends of which were supported by forked sticks thrust into the ground, and a hot fire was kindled close-by. The drippings were caught in troughs of bark, wood, or stone. This melted fat was stored in a deer paunch. Larger bones were broken up and the marrow was melted and stored in deer or elk bladders. (Teit 1900:234)

The killing of a black or grizzly bear required a certain amount of special ceremonial attention on the part of the Lower Thompson hunter. He sang or talked to his kill, sometimes marched around the animal ceremonially, and wept for it. Certain parts of the body had to be removed at the kill site. The head was eaten with the rest of the meat and the skull was "set up," although how and where are not revealed by Ray's (1942:129) record.

There were among the Lower Thompson a number of meat tabus that applied to all or to special subsets within the social group. For example, no one could eat deer and salmon together. Nor could anyone eat coyotes, wolves, mink, crows, eagles, meadowlarks, reptiles, caterpillars, slugs, grasshoppers, yellowjacket larvae, frogs, and unlaid eggs of the magpie, crow, and certain other birds. Children were forbidden to eat the land otter. Female children were not permitted to eat blood, even if cooked, and the head of deer and mountain goats. Women were not allowed to eat the heart and kidneys of the game. (Ray 1942:130-131)

Plant Collecting

Roots, berries, seeds, shoots, stalks, and other vegetable foods were important in the diet of the Lower Thompson. The data assembled below are drawn primarily from Teit (1900) and Ray (1942) and are cultural in their focus. Additional Thompson food-use information together with a partly now outmoded botanical identification of the taxa in question can be found in Teit's (1930b:237-239) ethnographic study of the Okanagan group. A far more extended and botanically refined inventory of Thompson subsistence taxa and their edible components is assembled in the final section of this present chapter, that considering specifically the Lower Thompson utilization of the mountainous segment of their tribal territory, including the upper Skagit portion of the Park.

Roots

Roots comprised a significant part of the Thompson food supply. They were gathered in early summer and in fall, some in the dry valleys but most only in the high mountains. According to Teit, the principal roots obtained were "Indian potatoes" (spring beauty corms), tiger lily bulbs, wild onions, and the roots of the yellow avalanche lily, chocolate lily, wild sunflower, and cattail. Gathered also were a number of other local roots that are not identified in Teit's monograph of 1900 either by common English terms or taxonomically but only by their native Thompson names. According to Ray, the main food roots of the Lower Thompson were camas and bracken roots. The lack of correspondence between these two short lists of Teit and Ray may result from the fact that the former is speaking of the Thompson as a whole -- or probably more especially of the Upper Division -- and the latter of only the downriver segment of the tribe. More than 30 additional Thompson food roots are listed by Turner (1978; see below), but none appear to have been individually of great importance. Bitterroot were secured by the Lower people in their barter with the Upper Thompson. (Ray 1942:131; Teit 1900:231-232, 236)

Roots were uncovered by women with a digger consisting of a curving hardwood stick, sometimes charred at the point, fitted with a perforated cross handle of wood or deer antler. As they were loosened from the soil, they were tossed into a small back-basket, which, when full, was emptied into a large basket close-by. Nests of squirrels and mice were also robbed of their roots and seeds. (Ray 1942:145; Teit 1900:231)

The occasional fish stocking of the Thompson has already been commented upon. In a second way in old traditional times the tribe undertook to increase its native food resources: sometimes they set fire to the hillside woods to obtain a greater abundance of roots (Teit 1900:230).