|

North Cascades

Ethnography of The North Cascades |

|

CHILLIWACK

| DATA BASE |

The ethnographic and ethnohistorical data relating specifically to the Chilliwack are very limited. Accordingly the data compiled in this chapter are of two kinds. They include such ethnographic and ethnohistorical materials on the Chilliwack as are available and, to supplement these, data on the linguistically and culturally related tribes of the Upper Stalo cluster (see Figure 2-1).

The ethnographic information relating to the Chilliwack is drawn principally from Wilson Duff (1952) who in 1949 and 1950 gathered a small amount of traditional life-pattern data from Chilliwack informants. Some additional Chilliwack information comes from Franz Boas (1894) who carried out a brief period of field research among the neighboring Chehalis in 1890, from Charles Hill-Tout (1903, 1978a) who worked with Upper Stalo groups, including the Chilliwack, in the 1890s and early 1900s; and from Marian Smith (1941, 1946, 1947, 1950a, 1950b, 1952, 1955, 1956) who in the 1930s and 1940s studied the Chilliwack and nearby Upper Stalo tribes. Nevertheless, our knowledge of the aboriginal and early postcontact life style of the Chilliwack is singularly meager.

Because the Upper Stalo tribal cluster as a whole is considered by Duff to have possessed a fundamentally similar life mode, whatever the variations in detail, it appears legitimate to generalize with caution to the Chilliwack, where information concerning this group is lacking or seemingly faulty, from other Upper Stalo groups. Here of particular value are Duff's (1952) much more comprehensive and detailed field-derived materials on the native lifeways of the Tail in particular, the uprivermost of the Upper Stalo tribes. Limited information to check and complement Duff's data are provided by Boas' (1894) Chehalis study.

The ethnohistorical data are taken primarily from Charles Wilson (1866, 1970) who, as a member of the British Boundary Commission, lived for some months in 1859 in the Chilliwack country and nearby. Specific data on the Chilliwack and on the natural history of their area -- including their river, Chilliwack Lake, and Cultus Lake -- are included in Wilson's field records. These data represent, so far as I am aware, the earliest documentation relating to the tribe. Information relating to several Upper Stalo villages -- but to none of the Chilliwack -- is reported in the journal of Simon Fraser (1889, 1960), who with his exploring party paddled down the Fraser River and then back up in the summer of 1808. Additional bits of Upper Stalo cultural data are also drawn from several minor sources as indicated in the pages that follow.

As revealed at various points in this chapter, this procedure of placing the Chilliwack data, however limited, in the larger Upper Stalo cultural context yields one special reward: it provides strong, though palpably incomplete, evidence that the Chilliwack were in some ways an atypical Upper Stalo people. In part, these divergent lifeways were plainly the consequence of the group's unique, pre- and early postcontact, side-valley geographical location. In part, they may have been a residue of a pre-White history that differed importantly from that of their Upper Stalo neighbors.

| INTRODUCTION |

In this section are briefly discussed the early postcontact history of the Chilliwack, the terms used in the past to designate the tribe, the territory it claimed and over which its members roamed in the pursuit of their life plan, its linguistic and cultural affiliations, the meager demographic data available for the group, and the physical characteristics of the people as these are known.

Early Chilliwack History

The Fraser Valley in the neighborhood of the Chilliwack homeland was first explored by Simon Fraser's party in late May and early June, 1808. It is reasonable to assume that early White and métis fur trappers and traders followed Fraser in the main valley and probably moved up the Chilliwack River in their search for pelts.

Data to support this assumption, however, have yet to be located. In 1827 Fort Langley was established by the Hudson's Bay Company on the south bank of the Fraser about halfway between the Chilliwack River and the mouth of the Fraser to serve as the trading center for the area. In 1828 George Simpson of the Company ran the Fraser River from the Thompson River mouth to the sea, only to discover that this was too dangerous a route for the fur trade. Regrettably his detailed account of this journey remains unpublished. December of this same year found a party from the fort ascending the Fraser and entering "the Chul-Whoo-Yook [Chilliwack]," but, after about 10 miles on the stream, having to turn back because of the strong current. It reported seeing cached canoes but no natives. (Duff 1952:44, 1964:54, 56; Fraser 1889, 1960; Phillips 1961 2:441; Rich 1967:275; Wilson 1970:36 fn. 18)

Although at least the more downriver Upper Stalo already "knew the sign of the cross and a few simple hymns," the first organized missionary activity in the region was undertaken in the early 1840s by Roman Catholic priests using Fort Langley as their base (Duff 1964:89-90; Lempfrit 1985:35). The extent to which members of the Chilliwack tribe were contacted is uncertain. In May, 1846, a Fort Langley group went up the Fraser to the Chilliwack to establish a salmon fishery on its banks, a fact that argues for the importance of the Chilliwack as a salmon stream. (Nelson 1927:17; Duff 1964:89-90; Lempfrit 1985:35)

Fort Yale was established in 1848 by the Hudson's Bay Company and a few months later Fort Hope. Their presence in Upper Stalo country initiated extensive contact between the native groups of this area and Whites, a contact in which the Chilliwack must have participated to some degree. (Smith 1955:104)

The summer of 1858 saw a rush of gold prospectors and miners ascending the Fraser to the newly discovered fields on the riverbanks and bars between Forts Hope and Yale and even into the region above the canyon. Attracted by the lure of gold, many Indians turned to hunting the metal and, neglecting to store fish and roots, starved during the following winter. By mid-winter the gold fever had largely subsided owing to the intense cold and the lack of supplies. While the Chilliwack and their territory were evidently not directly involved in these activities, they could hardly have wholly escaped their effects. (Mayne 1862:50, 55-56, 66; Smith 1955:104)

In 1858-1859 the British Boundary Commission surveyed the international border in the Chilliwack territory and its vicinity. Its various supply and surveying parties that camped through the period in the Chilliwack region and constantly criss-crossed it during these years employed local Indians in various humble capacities, surely Chilliwack among them. (Wilson 1866, 1970) These very close contacts must have influenced the native life style, in some cases on a permanent basis, but the records are silent on these points.

Owing to time constraints, no effort has been made to review historical material after 1860 for whatever ethnographic scraps it may contain bearing on traditional Chilliwack life patterns.

Ethnonymy

To the degree that the Chilliwack have been distinguished in the ethnographic and historic literature from the other Halkomelem (Cowichan) tribes, they have, with one single exception so far as I am aware, been referred to as the Chilliwack or some obvious variant thereof. The only alternative designation is that recorded by Wilson in his phrase "the 'Chilukweyuk,' or 'Squahalitch' . . ., on the Chilukweyuk River." (Boas 1894:460; Hill-Tout 1903:355; Hodge 1912 1:268; Mayne 1862:295; Smith 1950a:340; Wilson 1866:278)

Tribal Territory

To understand the Chilliwack data as well as references to Sumas Lake, Chilliwack River, and Vedder River in the material that follows, a few geographic facts, drawn from Duff (1952) and other sources, must be comprehended.

(a) In late precontact and perhaps very early historic times, the Chilliwack River, exiting from its canyon, flowed westward into Sumas Lake and thence northward to the Fraser River. A low bog lay between the Chilliwack and the Fraser, though it gradually grew firmer as time passed. (Duff 1952:43; Fraser 1960:101-103)

(b) Sometime before 1830, the Chilliwack altered its lower course and, having emerged from the canyon mouth near Vedder Crossing, turned sharply to the north. Meandering across the low plain, it reached the Fraser just west of the present city of Chilliwack. The water from Sumas Lake found its way to the Fraser by its own small stream. (Duff 1952:14, 44)

(c) In the late 1880s a downriver log jam caused the Chilliwack River to flow westward again from the Chilliwack canyon mouth, breaking through to Vedder Creek. Now called Vedder River from this point, it ran to Sumas Lake and once more north to the Fraser. (Duff 1952:44; DEMR Hope quadrangle 1970)

(d) In the 1920s Sumas Lake was intentionally drained. The lower Chilliwack, still termed Vedder River, was directed through the new Vedder Canal to the lower Sumas River and the Fraser. (Duff 1952:44)

These data reveal how essential it is to note the time period in question when the ethnographic and especially historical data refer to the lower Chilliwack River and to the people and villages along it.

The borders of the traditional Chilliwack home country were defined in the Indians' mind with considerable precision, reflecting a relatively highly developed concept of territorial ownership not present among all Upper Stalo tribes. According to Duff (1952:21):

The [Chilliwack] tribe held a small stretch of the south side of the Fraser between the mouth of the Chilliwack River and l

x

we, a village half-way between Chilliwack and Sumas Mountains. From here the boundary ran due south, skirting the east side of Sumas Lake, to Maple Falls on the Nooksack, thence east along the north fork of the Nooksack and across the mountains to Chilliwack Lake. From the lake it ran west again to encompass the valley of the Chilliwack and that part of the Fraser Valley south of a line joining Elk Creek falls with the mouth of the Chilliwack River. (Figure 2-1).

Figure 2-1. Traditional territory of Chilliwack and neighboring groups

as defined by Duff (1952: map 1, modified). Chilliwack River course is

shown approximately as in pre-1830 and late 1800 periods. I differentiate

between the Stalo group and nearby non-Stalo tribes; also between Upper

and Lower Stalo as somewhat fuzzily distinguished by Duff. I label Chilliwack

and Cultus Lakes, locate Maple Falls, identify area east of Chilliwack Lake as

traditional (Lower) Thompson country, and designate approximate western limit

of North Cascades National Park to indicate extent of Chilliwack occupation.

These boundaries are, in most respects, as close to the facts as we are likely to get. When they are drawn slightly differently by other ethnographers, this is largely because, without special interest in them, they plot them more loosely. Still Duff's data call for several comments.

- The westward course of the Chilliwack River from the mouth of the Sweltzer River, which drains Cultus Lake, to Sumas Lake and then northward plots the late precontact and perhaps early historic situation. But the western Chilliwack boundary along the east side of Sumas Lake can only be that of the 1830s or later. Only then, after the bog filled in and Fort Langley provided protection from downriver raiders, did the Chilliwack leave their old homeland in the canyon above Vedder Crossing and settle out on the Fraser plain and make important subsistence use of its resources. Only then did they extend their border to Sumas Lake. (Boas 1894:455-456; Duff 1952:43)

- In precontact and possibly early historic times Cultus Lake, its source streams, and its outlet river were the territory of the Cultus Lake people, not the Chilliwack. (Duff 1952:38; Hill-Tout 1903:267-268; Smith 1950a:340-341)

- Duff's plotting of the southwestern Chilliwack border fails to carry the line "due south" from Sumas Lake to Maple Falls as the description above defines that boundary.

Most important for the present study is the fact that Duff's southeastern tribal line places the northwesternmost corner of the North Cascades Park squarely within old Chilliwack territory.

Linguistic and Cultural Affiliation

To comprehend their cultural position in relation to their tribal neighbors and the ways in which they were similar to and different from them in their life patterns, the Chilliwack must be viewed in the context of the larger lower Fraser region. In this segment of the Pacific Northwest linguistic and cultural relationships were intimately intertwined. It is convenient, therefore, to discuss the two together.

Careful linguistic reconstruction indicates that some time in the distant past the language family now known as Salishan developed in a riverine, forested valley environment west of the Cascades, perhaps even in the lower Fraser country itself or not far away. About 3,000 years ago it spread up the Fraser Valley and over the Cascades into the Plateau. This movement, in time, split the family into its two major units, a Coastal and an Interior division. The Coastal group (and, of course, Interior likewise) carried forward the normal process of language change through time when speakers are isolated to some extent by distance or other contact barriers. It continued to divide, ultimately to produce in the Strait of Georgia area of southeastern Vancouver Island, the nearby Fraser Valley, and the islands in-between, the language now customarily termed Halkomelem, though Cowichan, Nanaimo-group, and still other designations have been used for this unit.

As time passed, Halkomelem spread up the Fraser River to the mouth of Fraser Canyon, gradually separating into a number of mutually intelligible dialects that in the late prehistoric and postcontact period clustered into three dialect groups: Nanaimo and Cowichan, both on the southeastern corner of Vancouver Island, and Stalo in the lower Fraser Valley from Yale downstream to the river delta and a small area about the Fraser mouth (Figure 2-2). Chilliwack is one of the several Stalo tribes, all possessing a common language and cultural base but not a political unity. (Boas 1894:454; Duff 1952:11-12; Dyen 1962:156; Elmendorf and Suttles 1960:1; Fraser 1960:99; Hill-Tout 1903:355, 369; Mayne 1862:242, 295, 296; Smith 1950a:332-335, 338, 339; Suttles 1957:168; Suttles and Elmendorf 1963:48-49; Swadesh 1950:163, 164, 166-167, 1952:247; Teit 1900:168; Thompson 1979:693)

Figure 2-2. Principal mainland Halkomelem dialect communities and

neighboring non-Halkomelem Salishan languages (Elmendorf and Suttles

1960:2, slightly modified). Shown are Halkomelem boundaries with

Skagit and (Lower) Thompson, tribes also considered in this report.

Boundaries are approximate. Chilliwack Lake, the British Columbia-Washington

boundary, and northwestern border of North Cascades National Park have

been added.

These Fraser River tribes -- the Stalo -- formed a single dialect chain, each population entity differing somewhat in speech -- apparently also to some degree in culture -- from its neighbors above and below in the river valley, with those at the upstream and downriver ends of the chain being notably different. In spite of this linguistic and cultural chain structure, one sharper than normal break occurred in this Stalo sequence. This break was across the Fraser Valley either just below the Chilliwack and Sumas or possibly a bit farther downriver. The six small tribes above this line are termed by Duff the "Upper Stalo" -- as opposed to the "Lower Stalo" below -- a useful designation that will be followed in this present study. (Duff 1952:11-12,19-23; Elmendorf and Suttles 1960:1-3, 17)

Among the various Coastal Salishan languages known at the time of first White contact, which were most closely related to Halkomelem? Although there have been slightly differing formulations by linguists in the past, the kinship seems to be particularly close with Squamish, Nooksack, and Straits Salish (Lkungen, Lkungeneng), this last group including Lummi, Songish, Samish, KIallam, and other coastal and island dialects south of the Fraser delta and on the southeastern point of Vancouver Island. (Dyen 1962:159, 160; Elmendorf and Suttles 1960:3; Swadesh 1950:163,1952:232)

In linguistic terms, the Chilliwack are especially intriguing as a Stalo tribe. There is some evidence that as recently as the late 1700s the group (and perhaps also the Cultus Lake people) may have spoken a different dialect, even a different language than that of more recent years. Perhaps it was most akin to Nooksack of the upper Nooksack Valley, though here the evidence is not fully convincing. Such a kinship, however, would not be out of the question since the Nooksack territory was contiguous to that of the Chilliwack on the southwest (Figures 2-1, 2-2), the groups evidently saw a good deal of each other, and both were upriver peoples sharing rather similar wooded valley econiches. It has already been noted that, although unintelligible to Stalo, Nooksack was among those Coastal Salishan languages most closely related to Halkomelem. (Boas 1894:455; Duff 1952:11, 12, 39, 43; Hill-Tout 1903:355, 357, 1978b:135; Smith 1950a:334-335, 341; Suttles 1957:167; Swadesh 1950:159, 160, 1952:233 fn. 3)

Demography

The size of the Chilliwack population in late protohistoric times is unknown, although, as Hill-Tout (1903:355) remarks, they appear never to have been "a populous tribe."

In 1839, in a Stalo-wide census by Hudson's Bay traders at Fort Langley, the "Chilsonook" were counted at 151 persons. About 1860 the Chilliwack population was estimated by Wilson (1866:278) at 200. While characterizing the 1839 Fort Langley head-count for the various Fraser River tribelets as in general "quite remarkable in its accuracy and detail," Duff (1952:28) believes its Chilliwack figure to be too low, "especially since the 1879 census sets the Chilliwack population at 296." Duff may here be correct, for, because of the early steady depopulation, the 1839 census should have shown a larger person count than the 200 figure of about 1860. On the other hand, as Duff (1952:28,129-130) likewise remarks, probably some of the apparent increase reported in 1879 is the consequence of "the inclusion of some Pilalt," the tribelet immediately upriver from the Chilliwack.

Before the 1830s and especially prior to 1780, the Chilliwack numbers must have been appreciably greater, for a terrible smallpox scourge ravaged the region about 1800, killing, according to Jenness (n.d., MS), "about three-quarters of the Indians." Still other epidemics surely also reached the Chilliwack, and Fraser River Indians more generally, prior to the 1839 headcount, including the 1782 smallpox epidemic and the "fever" epidemic of 1830. (Duff 1952:28, 41)

One of the old Chilliwack villages carried in its native designation a reference to the severity of an epidemic that devastated it: it was translated by Hill-Tout's (1903:356) informant as "melting away" and by Duff's (1952:38) as "to dissolve." Contagious illnesses were, however, not the sole cause of major population reductions: another village was known as "wiped out by a slide" (Duff 1952:39).

Inasmuch as this chapter is concerned with the Chilliwack and their lifeways only in the protohistoric and early historic periods, the details of the continued decrease in the tribal population from 1839 to about 1915 and then the rapid increase in their numbers and the causes thereof fall outside its interest focus.

Physical Attributes

The earliest descriptions of the physical characteristics of the Upper Stalo are those of Simon Fraser (1960:100, 101), who included them in his journal of his travels down the Fraser in late June, 1808. He encountered his first Indians with a coastal cultural orientation -- several settlements of Tait -- in the Yale sector of the river. "Both sexes," he notes, "are stoutly made, and some of the men are handsome," although he could not "say so much for the women." On reaching the Tait village near Hope, he adds further details: 'The Indians in this quarter are fairer than those in the interior. Their heads and faces are extremely flat; their skin and hair of a reddish cast -- but this cast, I suppose, is owing to the ingredients with which they besmear their bodies."

A half-century later Charles Wilson, a member of the British Boundary Commission survey group, provides additional details. According to Wilson, who was in close field contact with the Halkomelem for many months in the 1858-1859 period, these tribes resembled "each other greatly in appearance and habits, such differences as exist[ed] being principally due to locality and the means by which they obtain their living,..." The Chilliwack, however, were a "noticeable" exception because they hunted "a great deal on foot, and, from constant exercise,... [were] much more robust in appearance, and more manly and open-hearted in manner, than their brethren of Vancouver Island." Inasmuch as specific Chilliwack data are lacking and their basic physical traits are unlikely to have varied much from those of their Fraser River neighbors and since careful descriptive information of this kind for this early time level is uncommon, the following general Halkomelem data are worthy of notice.

The stature of the Cowitchans [Halkomelem] is diminutive, ranging from 5 ft. to 5 ft. 6 in., and occasionally to 5 ft. 7 in., or 5 ft. 8 in. amongst the more inland tribes; the women are from 5 in. to 6 in. shorter. The hair is either black or very dark brown, coarse, straight, and allowed to grow to its full length, either falling in one large mass over the neck and shoulders, or plaited and done up in tresses round the head. The faces of both sexes are generally broad, the forehead low, the eyes black, bright, and piercing, though generally small, and set in the head obliquely like the Tartar or Chinese, the nose broad and thick with large nostrils, the cheek bones high and prominent, the mouth large and wide, with thick lips, especially the under one, and the teeth large and of a pearly white when young, but soon discolored and worn down by the hard service they have to go through, masticating the tough dry salmon, which constitutes their principal food; ... most of the old women met with had their teeth worn down to a level with the gum. (Wilson 1866:278-279)

Unlike the canoe people of Vancouver Island with their broad shoulders and good chests but small, crooked, weak legs, the consequence of spending the greater part of their lives squatting in a canoe, the Chilliwack had "straight well formed legs, the result of their more active life, and excursions into the mountains in search of bear and mountain goat." Usually all facial and body hair is removed by both sexes, though men occasionally encourage a small chin tuft. The skin color is dark olive, deepened to dark brown on the face through exposure. People age very rapidly, especially women. As they grow older, they are "much troubled with rheumatism and pulmonary complaints." In 1862 smallpox began its ravages and venereal disease had recently "increased to a fearful extent." (Wilson 1866:279)

Intentional flattening of the forehead extended up the Fraser only as far as Fort Langley in Wilson's day. Indeed, he saw no evidence of the practice even among the older people above the fort area. (Wilson 1966:278)

So much for the unusually rich and detailed ethnohistorical data, presenting, of course, primarily nontechnical observational information. What have anthropologists to say about the physical characteristics of the Middle Fraser people?

Near the close of the last century Boas (1892, 1895) recognized and documented a unique physical type in the Harrison Lake area on the basis of 15 measurements supplemented by a number of phenotypic observations. The type was characterized by a very short stature, a very round head, a flat nose with a low bridge, and a face that was very short vertically and in relation to its height very wide, all in comparison with other Indian types in the Northwest and even in North America in general.

Also recognized by Boas was a lower Fraser River type distinct from but closely related to the Harrison Lake type. This was slightly taller and rather less extreme in those other measurements involved in the several Harrison Lake biotraits mentioned above. Inasmuch as these middle Fraser data demonstrated a gradual change in type along the river, Boas (1895:549) concluded that these tribes "must have occupied these regions for very long times, and that the population has been very stable." (Codere 1949:176-181)

| SUBSISTENCE |

The Upper Stalo surely exploited fully their fish, game, and edible plant resources. Beyond the fact that fish -- notably anadromous types -- were exceedingly important, little is to be found in the ethnographic literature, however, to suggest the relative importance of these three principal food sources and how these proportions differed among the various tribal groups. As noted below, people who had no or few fishing locations within their own territory along the Fraser were accustomed to join relatives in other groups at their more favorable fishing sites.

From a few scattered notes it is clear that the old Chilliwack, in their aboriginal canyon and mountain country back from the Fraser Valley, had access to salmonids, perhaps in considerable numbers, in the Chilliwack River. We are not informed as to the degree to which they joined other Upper Stalo peoples farther upriver at their extremely rich salmon fisheries on the main Fraser. One surmises, however, that there could not have been much of this, for the tribe seems to have been a surprisingly isolated group in their back country. Consequently, it appears safe to conclude that the Chilliwack depended somewhat less on fish -- at least anadromous types -- and rather more on game than did other Upper Stalo groups.

The use of plant foods -- especially roots and berries -- is hardly mentioned in the published Upper Stalo ethnographic studies. Probably in comparison with nearby non-Halkomelem groups with limited salmonid supplies, their exploitation of these vegetable products was more restricted, if for no other reason than because the seasonal occurrence of salmonids and of roots and berries in large part coincided, and principal attention was paid to fishing rather than to plant collecting.

Though no dietary data exist, to my knowledge, concerning the variety, amounts, and nutritional characteristics of the typical Chilliwack food intake, Rivera (1949:19-36) provides generalized information for the Northwest Coast peoples. In considerable measure this must likewise apply to the traditional Chilliwack, with sea products largely deleted and the inclusion of more game and inland vegetable foods. Chilliwack mainstays were certainly fish (probably especially salmon even for this lateral-stream group), meat, root crops, bulbs, tubers, and berries, all eaten both seasonally and prepared for storage. By preference, both dried and fresh foods and both flesh and plant foods were eaten year-round.

Under normal conditions, Rivera reports for the entire coastal area but surely no less for the Chilliwack specifically, proteins were abundant in the foods consumed. The situation in regard to fats is less clear, but the availability of both fish (particularly salmon) and game fat presumably furnished dietarily adequate amounts: at least on the coast fat fish were preferred for roasting and the drippings were saved for consumption. Since among the Chilliwack salmon were not far from the sea, they doubtless arrived in good condition, not fatless and beaten as at the headwaters of very long salmon rivers like the Columbia (Smith 1984:136-140). As an upriver tribe in their back valley with its river prairies and nearby hillsides, wild roots, bulbs, and tubers were clearly available to the Chilliwack to add the essential carbohydrate component to their diet. Sugar was largely provided by fresh and dried berries and other fruits.

In the domain of vitamins far less was known to Rivera. Further the situation is complicated by the critical importance of understanding not only their availability in traditional Chilliwack fresh-eaten foods but, far more importantly, their availability in foods that were processed in various ways before being eaten. Vitamin C, however, is known to have been secured in fresh fruit and vegetables (especially green sprouts) and in the blood of freshly killed fish and animals, many of even these plant foods obtainable throughout much of the year. Salmon was a good source of both vitamin A and vitamin D.

Even less was known in her day, Rivera observes, about dietary minerals. Those that are soluble were, of course, ordinarily leached out of boiled foods with the containing water, yet they were not lost as food, for the coastal groups -- again plainly including the Chilliwack -- customarily used this liquid in stews and soups. Dried serviceberries, which seem to have been available to the Chilliwack to some degree though they grew more prolifically in the interior of the Province (Turner 1978:180-182), contained unusually high amounts of iron and copper and were likewise high in manganese, all necessary for human health.

In short, to the degree that the native Chilliwack diet is understood, it appears to have been more than adequate in its quantities and its nutritional properties.

Fishing

Concerning fishing and its importance Duff's summary paragraph cannot be improved upon:

To the Stalo, with their great wealth of fish resources, fishing was the most important economic activity. In the main [Fraser] river or its tributaries they caught the five species of salmon, as well as sturgeon, eulachons, trout, and other river-fish. They used many methods and devices -- dip-nets, bag-nets, harpoons, weirs, traps, hooks. Although fresh fish was procurable the year around, they dried or smoked large amounts during late summer for winter use. (Duff 1952:62)

All Upper Stalo men were fishermen. The more proficient became in a sense specialists. (Duff 1952:72)

Salmon

The five salmon species of the Upper Stalo country were:

- Oncorhynchus tshawytscha: chinook, king, or spring salmon.

- O. nerka: sockeye salmon, silver trout, silvers.

- O. gorbuscha: pink or humpback salmon.

- O. keta: chum or dog salmon.

- O. kisutch: coho (cohoe) salmon. (Duff 1952:62; Wydoski and Whitney 1979:54-64)

Not surprisingly, all five were recognized by the Chilliwack as different fish and were referred to by different terms, as distinct, too, from steelhead and trout (Hill-Tout 1903:389). Unfortunately, I know of no ethnographic data or recent natural history information reporting how many of these five salmon species ascended the Chilliwack River and, it they entered the stream, how far upriver they swam. That some salmon, at least of the chinook variety, entered and made their way up the Chilliwack, however, is indicated by several fragments of evidence.

- A Pilalt myth, recorded by Hill-Tout (1903:402), that purports to explain how salmon were first brought to the Fraser River tribelets (see later mythology section), concludes with this relevant statement: "From this time onwards the salmon have visited annually the streams mentioned; ... [In some streams, however, they are not good fish; in others, they die in great numbers.] In the Chilliwack, on the contrary, they are good and fine, and are easily dried and cured."

- As noted below, the only salmon run specifically mentioned ethnographically for the Chilliwack River in a non-mythic context is a chinook run of mid-summer (Duff 1952:62). Hill-Tout (1903:390), however, states that "autumn ... was marked among the Tcil'Qe 'uk [Chilliwack] by the departure of the salmon." It seems probable that Hill-Tout speaks here of salmon in the Chilliwack and not the Fraser, on which the Chilliwack maintained no salmon fishing camps in pre-White days. If so, the salmon remained in the stream for a longer period than Duff's data imply.

- In late 1846, a salmon fishery was established on the banks of the Chilliwack River by a party from Fort Langley, sent upriver specifically for this purpose (Nelson 1927:17). Unhappily we do not know the location of this site nor the success of the venture, but presumably the traders must have seen good evidence in the stream of salmon in numbers.

- In Charles Wilson's journal of 1859 occur three entries that

attest to salmon of some variety or varieties in the Chilliwack at least

up as far as Chilliwack Lake. On June 16 of that year, when encamped at

"Chilukweyuk Prairie" close to the Chilliwack River a short distance

below the Chilliwack Canyon, he reports being told by Indians of salmon

abounding in Chilliwack Lake. In the same sentence he adds that "a

reconnoitring party sent forward give glowing accounts of the fishing"

in the lake, salmon being presumably alluded to. (Wilson 1970:49)

On July 27, 1859, traveling along the Chilliwack River trom his Fraser prairie headquarters to Chilliwack Lake, he camped that night close to an Indian group (surely Chilliwack), just upstream from the Chilliwack Canyon mouth. These people, who were fishing nearby, gave him "a splendid salmon" after he had talked and smoked with them for a time. (Wilson 1970:63)

Finally, Wilson (1970:73) appears to be commenting on the Chilliwack River and its side streams -- note that he uses the phrase "the river" in the singular -- when he composed his diary entry on October 9, 1859: "One curious thing at this season of the year is the quantity of dead salmon on the banks of the river; in some of the smaller streams the quantities are so numerous that it produces a most intolerable smell & renders the water anything but pleasant for drinking purposes." When he wrote this note, he had been encamped on the lower Chilliwack River, below the canyon, for almost a full month, ample time for him to observe the phenomenon.

From the above data it must be concluded that salmon occurred at least as far up the Chilliwack Valley as the head of Chilliwack Lake. If they managed to make their way to this point, they may well have climbed the upper Chilliwack River into the North Cascades Park complex, the northern boundary of which is no more than a mile or two above the lake. But for this I have as yet no proof.

In Upper Stalo territory generally, salmon were easily taken in prodigious numbers at favorable locations along the Fraser and its tributaries and were easily dried for later provisions. These fish and the landform and climatic conditions of the country, working hand in hand, provided the people with "a storehouse of food unexcelled by that of any other Indian tribe." (Duff 1952:62)

Our earliest historical records -- the 1808 journal of Simon Fraser -- confirm Duff's assessment of the importance of salmon to the Upper Stalo. At least in late June ot that year, the salmon tisheries in their territory were evidently more productive than those farther down the Fraser. Fraser's party of exploration received salmon -- generally "in plenty"- -- from them, beginning with the first Upper Stalo people encountered. (Fraser 1960:98-101)

Of the five species, the chinook and sockeye were economically by far the most important to the Upper Stalo. To aid in comprehending what these enormous salmon resources meant to these tribes, a few details concerning the five types seem worthwhile:

- The chinook variety was the finest of the five species to

the Tait tribe and the variety for which the first salmon ceremony was

celebrated. According to Duff (1952:62) and his informants, soon after

the ice broke in the Fraser, small, fat chinook began to ascend the

river. In July a small run, too fat to keep well, passed up the

Chilliwack River. The main runs in the Fraser appeared after mid-July,

when the high water had subsided. During August and early September they

passed upriver in large quantities; these were large chinook, lean and

easy to dry. By the middle of September the Fraser run declined,

although even larger fish then commenced to run up some of the

tributaries.

In terms of the special interests of this study, the Chilliwack statement is particularly noteworthy. Whether the mentioned July run was the sole one up the Chilliwack during the salmon season is not made clear. - Sockeye salmon began their upriver run in mid-June, reached their peak in August, and fell off by the close of September. Very fat early in the season, they became leaner until late August, when they were in perfect condition for drying. Less favored as food than chinooks, most were used for oil. (Duff 1952:62)

- Pink salmon appeared in late August and spawned for about a month. Large runs occurred only every second year. (Duff 1952:62)

- Chum arrived in mid-September and remained into December. (Duff 1952:52)

- Coho salmon "spawned in the small streams during late fall and winter." (Duff 1952:62)

Salmon were taken by the Upper Stalo with dip, gill, and bag nets, were harpooned, and were caught in weirs. How many of these techniques were in use among the Chilliwack we are not told.

Chinook and sockeye were dip-netted by thousands of Upper Stalo Indians from family-owned rocky banks or platforms over the water. The device consisted of an Indian hemp net attached to a vine maple hoop with a long cedar or fir handle. It was either moved slowly back and forth in an eddy or moved up and down in the water. Gill nets with wooden floats and stone bottom-weights were used from canoes. Bag nets were stretched between two poles held vertically from canoes. (Duff 1952:62-63, 69; Fraser 1960:101, 114)

Upper Stalo harpoons, of medium dimensions, were made with a fir or cedar shaft, a serviceberry or spiraea foreshaft, and a one- or three-piece toggle-type head. The head was of bone, charred wood, flat slate ground into shape, or elk antler hardened by heating and oiling. The retrieving line was of Indian hemp. Fraser seems to refer to just such a device when in a Tait village in 1808. Chinook were harpooned in early spring in the Fraser; cohos in the tributaries. In winter bottom-lying salmon were taken with these devices from canoes by firelight. (Duff 1952:60-61, 67; Fraser 1960:101)

Weirs, some with traps and some without, were widely used by the Upper Stalo in taking salmon. The fisherman speared the fish by thrusting straight downward with a three-pronged leister or by slipping over their head a noose hanging from a pole. The Chilliwack caught most of their salmon with brush weirs, supported by a row ot pole tripods set across their stream: according to an old myth, the method of construction and use of this device was taught the tribal ancestors by Wren. After the 1830s and the movement of the Chilliwack from their traditional canyon home out onto the Fraser plain, salmon weirs were placed in the various meandering mouths of the Chilliwack River. (Duff 1952:37, 38, 67; Hill-Tout 1903:367)

Salmon intended for storage were cut up for drying by Upper Stalo women, using in the old days a ground-slate knife. The head was removed and the fish allowed to bleed thoroughly. Then the fish was cut down each side of the backbone to the interior cavity, leaving the flanks and belly in one piece and the backbone and other bones attached to the tail. After being scored, the two sections were hung over a pole to dry. The summer weather in Upper Stalo country provided ideal conditions for drying fish: it was warm and dry and the breeze blew upriver constantly. The large chinooks caught late in the season when the drying weather was less dependable were cut thinner to promote proper preservation. (Duff 1952:62, 63, 64 Plate II, 66-67)

Among the Upper Stalo not all salmon were dried. From mid-July to mid-August when three kinds of egg-laying flies plagued the area, it was best to smoke fish. In the fall many fish were smoked by preference. The process was carried out over alderwood fires in the smoke house. Among the Chilliwack fish were sometimes cured by being smoked at intervals instead of continuously. This imparted to them a peculiar salty taste. (Duff 1952:66-67; Hill-Tout 1903:396)

Salmon heads were split, cleaned, and dried on a rack for later use in soups. Chinook roe was hung in similar fashion to dry, later to be soaked or boiled for eating. Or it was placed over the winter "in a deep hole about 4 feet in diameter lined with several inches of maple-leaves," perforated to allow the oil to drain through. Then the roe was covered with more maple leaves and finally with earth. Cheese-like in its consistency when removed, it was eaten raw, boiled into soup, or applied to sores as a poultice. (Duff 1952:66)

Once dried, the fish were placed in an elevated storehouse where they could be protected from moisture and rodents for winter consumption. If completely dry, they were stored in boxes; otherwise they were hung up to dry further. (Duff 1952:67)

Chinooks were the only salmon that were dried. Sockeyes were caught for their oil, used "for everything, like we use lard." To extract the oil the entire fish was placed in a wooden trough or stone bowl in the sun and the oil was separated out as it seeped to the bottom as the fish decomposed. Clear, light red, and viscous even in cold weather, the oil was stored in bladders(?) of deer, bear, or mountain goats. Twice on their 1808 downriver journey of exploration of the Fraser River, Fraser and his party were served oil in "plenty" as a part of meals received at Upper Stalo settlements. (Duff 1952:66; Fraser 1960:101)

Sturgeon

White sturgeon, said to have weighed up to 1,800 pounds, were caught by the Upper Stalo year-round in the Fraser and its larger sloughs and tributaries. In winter they were harpooned in the deepest part of the river.

In mid-summer, when spawning in shallower water, they were taken with bag nets, harpooned, and caught with hook and line. In the outlet of Sumas Lake they were even taken in a very large weir. Fraser's exploring party was welcomed in late June, 1808, with a sturgeon meal in a village near Hope. (Duff 1952:67-68; Fraser 1960:101)

When conducting field research among the Chehalis (Figure 2-1) in the 1890s, Boas (1894:460) was informed that the Chilliwack caught no sturgeon. Other data gathered for this present study clearly contradict this statement: e.g., the Chilliwack were said to have eaten a particular moth during the sturgeon season to bring them good fishing fortune (Wilson 1866:285).

The large sturgeon harpoon was a complicated device. It consisted of two long, symmetrical foreshafts, their points about one foot apart and their other ends brought together in socket form to receive the end of the shaft, sometimes as much as 60 feet long. Each foreshaft was armed with a three-piece point, a central ground-slate blade flanked with two barbed side pieces of antler or mountain goat horn. Each was tied to its foreshaft with a cord, and the foreshafts, in turn, to the handle. The device was thrust into the bottom-swimming fish by a man in the stern of a canoe, as the craft drifted with the current. Struck, the sturgeon was played with a long line, tied to the harpoon handle and kept coiled in the canoe. (Duff 1952:60, 67, 68; Wilson 1866:284-285)

In shallow water sturgeon were captured in bag nets dragged behind two canoes. The net was either attached to two poles or, fitted with cedar floats and stone weights, was pulled with two main ropes, one attached to each upper net corner. Fraser, in July of 1808, observed just such a net in use when passing through Tait country. Bag nets of some variety were employed by the Chilliwack in sturgeon fishing. (Duff 1952:68-69, 115)

To a lesser extent sturgeon were also taken by the Upper Stalo with hook and line. Fishing in this manner was carried out throughout the summer, most successfully at night, when the line was tied to a long pole buoy anchored to a heavy rock. In a Chilliwack historical narrative, angling for this fish is mentioned as a central element in the story. (Duff 1952:69,115; Wilson 1866:284)

The sturgeon weir erected by the Sumas people at the outlet of Sumas Lake appears to have been an unusual, if not unique, fishing contrivance among the Upper Stalo. A 200-foot fence of some sort was held in place against a series of two-pole supports pushed into the shallow clay stream-bottom. Horizontal poles ran across the stream, resting on the apexes of these crossed pole pairs. When a fish was observed in the clear water resting against the weir, it was noosed and harpooned from these horizontal, connecting poles. (Duff 1952:68, 69, 70)

Sturgeon flesh was usually cut into slabs and, held open with sticks, smoked in a smokehouse. The head and tail were cooked and eaten fresh. From along the backbone valuable glue was obtained. (Duff 1952:70)

Trout

Trout -- -steelhead, char, cutthroat, and smaller trout -- were taken by the Upper Stalo by the same methods as used for larger fish. They were caught at night by torchlight with salmon harpoons or in Fraser tributaries -- including the Chilliwack -- -with smaller harpoons, single or triple pronged. Fine-meshed bag nets, attached to two poles, were often employed from drifting canoes, a method known to have been used by the Chilliwack Weirs with a variety of trap designs were constructed along small streams. The Chilliwack are reported to have had one with two long conical traps, one facing upstream and the other down. Trout were also taken with small hooks fashioned of thorns or of bone and wood. (Duff 1952:69-70)

Trout were usually eaten fresh. An Upper Stalo fisherman with a good catch kept "only what he needed and gave the rest away." (Duff 1952:70)

Other Fish

In May the eulachon ascended the Fraser as far as the Chilliwack River to spawn. They were scooped in huge numbers into canoes with dip nets. The Chilliwack, as well as upriver people who thronged down to meet these fish, participated in this simple and highly productive fishing. These fish, strung on sticks, were hung from racks under a bough roof to smoke over an alder fire. Eulachon oil was not extracted by the Upper Stalo as it was on the coast. (Duff 1952:70-71)

Suckers, graylings, and other fresh-water fish were caught by the same techniques as served to take larger fish. Fresh-water mussels from lakes in Upper Stalo country were eaten to some degree. (Duff 1952:70, 71)

Hunting

Very little information concerning Upper Stalo hunting is provided by Duff and virtually none, more's the pity, specific to the Chilliwack. This is particularly a shame, for Duff (1952:71) reports: "The fauna of the Stalo area was abundant and varied, and though not as important as fishing, hunting was a well-developed and important economic activity." It might be suspected that this was especially the case for the Chilliwack while they resided along the Chilliwack River above Vedder Crossing with no claim to a Fraser bank sector.

Used for food were the following mammals and birds, according to one of Duff's Tait informants: black bear, the favorite meat; mountain goat, rated second as meat; deer, much used but considered a dry meat; elk and grizzly bear, used less because difficult to secure; groundhog and beaver, popular meats; raccoon, wildcat, squirrel, and marten, sometimes eaten; ducks, geese, grouse, and eagles, much sought after; fish cranes, robins, bluejays, and crows, sometimes eaten. (Duff 1952:71)

Not regarded as proper food were dogs, wolves, coyotes, cougars, seals, weasels, mink, rats, and mice; likewise loons, owls, and woodpeckers. (Duff 1952:71)

As noted above, very little information on animals utilized as food by the Chilliwack is available, but such a list could hardly differ much, if at all, from the preceding Upper Stalo catalog, which is itself obviously incomplete. For what it may be worth, the animals casually mentioned in 1859 by Wilson, of the British Boundary Commission, as having been seen in the Chilliwack country include black bear (numerous and widely occurring), beaver, deer (numerous on the Chilliwack Prairie), marmot (numerous in Chilliwack Lake and Cultus Lake areas), marten (abound in Chilliwack Lake country), and rabbits (many in Cultus Lake sector). A flat stretch beside the Chilliwack River between Sleese and Tamihi Creeks, formerly the river bed, was termed "Grizzly Flat" by Wilson and his Commission parties. Cougar tracks were seen by Wilson in the December snow in the mountains, but whether these animals were avoided as food -- as, it is said, among the Upper Stalo in general -- is not known. (Wilson 1970:49, 50, 60, 65, 66, 67, 68-69, 79)

All Upper Stalo men were expected to become capable hunters. Some, however, became specialists, spending a good part of their time in pursuing game and leading "the fall expeditions to the mountains after goats." Typically they received their "greater knowledge of animal habits and hunting methods" from their fathers and were likely to transmit this information to their sons. A successful hunter might possess guardian spirits for hunting, but this was not essential for hunting prowess. (Duff 1952:72)

Because, as the following facts demonstrate, the Chilliwack and their mountain territory were clearly deeply involved in hunting pursuits, Duff's all too brief summary of Upper Stalo hunting patterns deserves quotation rather than the usual reworking and compression.

Most of the hunting was done in the fall, when the animals were fat. During the summer months, little hunting was done. The fact that the animals were thin, the abundance of fish, and . . . [perhaps] a restriction on hunting animals which were bearing their young, kept hunting to a minimum. After salmon-drying season was over, the hunters led expeditions into the mountains to hunt mountain-goats. There were apparently no sharply delinated hunting territories, but the hunters knew of mountains where there were many animals, some as far away as Chilliwack Lake or beyond. If they met hunting-parties of other tribes, there was no conflict (though. . . [one Tait informant] thought the Thompsons and Skagits fought when they met). These expeditions sometimes lasted several weeks. The party would set up hunting camps, and the hunters would operate out of these. Other men, women, and older children stayed in camp to cut up and dry the meat, gather firewood, etc. The meat was cut into slabs about an inch thick and smoked on a rack 4 or 5 feet high. The dry meat was quite light; one man could pack the meat of two or three goats. When enough had been obtained, the party started for home. The meat was tied up in packs, which were large envelopes of deer-hide carried by means of tump-lines over the forehead. (Duff 1952:72-73)

The Upper Stalo killed game "with bows and arrows, thrusting-spears and clubs, and caught them in pitfalls, deadfalls, snares, and nets," and used trained dogs in their hunts (Duff 1952:71).

Traps of four different types, each with its distinctive native name, are listed by Hill-Tout (1903:399) as Chilliwack devices for taking animals: (a) "fall" traps, which I take to mean deadfalls; (b) pit traps, always constructed with a V-shaped bottom to pin the legs of the animal together and prevent it from leaping out; (c) "noose" traps, which I gather were stationary set snares; and (d) spring traps "made by bending a sapling."

Deer were taken in numbers by the Upper Stalo. In the valleys they were chased by dogs into the river where hunters awaited them in canoes. In the mountains they were pursued by dogs, while the men attempted to get close enough for a bow and arrow shot. Deer were caught in pitfalls in game trails. A hole five feet deep was dug and fitted with two crutched sticks or several sharpened stakes, each long enough to hold the trapped animal off the ground. The hole was covered with cross-sticks, cedar-bark, and earth, which gave way under the animal's weight. (Duff 1952:71)

According to Simon Fraser (1960:98), the Tait captured deer and other large animals in nets. One net of this tribe that he examined in June, 1808, was "made of thread of the size of cod lines, the meshes were 16 inches wide, and the net 8 fathoms long." Presumably other Upper Stalo tribelets, including the Chilliwack, took game with the same or similar nets, but the evidence for this is lacking.

Black bears were driven by dogs until they tired and either turned to fight or climbed trees. They were then killed with bows and arrows or with spears. Bears were likewise taken in pitfalls of the type described for deer, and in deadfalls. Hibernating bears, too sleepy in their dens to be dangerous, were speared. (Duff 1952:71)

The Chilliwack River and Lake country was evidently excellent black bear country. During June and August of 1859 when camping in the area, Wilson (1970:50, 66, 67, 68-69) reports several bear sightings. On August 26 he notes: "bears are thick around us one or two have been killed by the men whilst on their way from one place to the other & the bear's meat... is not at all bad." Pitfalls were sometimes used by the Chilliwack to take these animals (Wilson 1866:282).

Grizzly bears, against which dogs possessed little merit, were taken by hunters. How this was normally accomplished is not described by Duff. But he reports as an Upper Stalo practice the very special, daring bone-in-mouth method recorded from informants in neighboring Plateau groups. A bone, about 1.5 inches in diameter and 8 to 10 inches long, was sharpened at one end, fashioned with a fork at the other, and provided with a leather band around the middle as a grip. When the bear, approached by the hunter, reared to fight with his paws and claws, the hunter, staying just out of reach, danced from side to side until the frustrated and angered bear advanced to attack with his mouth open. Then the hunter thrust the bone, point up, into the animal's mouth. Closing strongly on the bone, the bear drove the point through the roof of his mouth and the two prongs into the soft under surface of his jaw. As the animal fought the painful bone, the hunter speared it in the neck. (Duff 1952:72)

Mountain goats, hunted without the aid of dogs, were stalked with bow and arrow. In another method two hunters approached a group of goats from opposite sides. While one waited, pressing himself against the steep mountain side, along the animals' trail, the other alarmed the goats. When they retreated past the first man, he pushed them over the side with a stick. (Duff 1952:71-72)

That the Chilliwack were among the Upper Stalo tribes which hunted wild goats in postcontact days is indicated by a historical note from Duff's (1952:115) Chilliwack informant. He knew an old man who "had a hunter's magical formula written down in a memorandum book. One day the old man was hunting mountain-oats without success. He took out the book, read the . . . [incantation] and found six goats around the next rock." Doubtless the only post-White element in this simple narrative is the use of the written spell instead of one carried in the hunter's memory -- and presumably the use of firearms.

Small fur-bearing animals were caught in deadfalls by the Upper Stalo (Duff 1952:71). On one occasion in the Cultus Lake country of the Chilliwack, an Indian -- not necessarily a Chilliwack, however -- accompanying a British Boundary Commission field party killed a rabbit with a stone (Wilson 1970:60).

Ducks and geese, when migrating south in November, were netted by the Upper Stalo from canoes at night. The net was stretched flat on a square frame of four poles. One man was in the canoe bow; the other in the stern. Between the two a pitch fire was kindled on boards across the gunwales. While the canoes drifted downriver, one man held the net, threw it over the birds that were attracted by the light, pulled them in, and wrung their necks. Low-flying ducks were also brought down by loud shouts, a contention also made by several Gulf of Georgia tribes. (Duff 1952:67, 72)

Birds were also shot with arrows, blunt-headed ones for small birds. Hummingbirds, used in ornamenting hats and other articles, "were caught alive with special arrows, the ends of which were shredded so that they brushed out in flight." Birds were also snared. (Duff 1952:72)

The preparation, by the Upper Stalo, of meat for immediate consumption and for storage is not described in the ethnographic sources. However, we have two information fragments applying explicitly to the Chilliwack:

- Marrow was extracted from animal bones and eaten. When the Chilliwack saw their first Western candles, they mistook them for sticks of marrow and attempted to eat them. (Hill-Tout 1903:391)

- When birds were roasted by the Chilliwack immediately after being killed, they were considered to have had a salty flavor (Hill-Tout 1903:396).

Plant Collecting

Information regarding the plant foods collected and eaten by the Upper Stalo is fragmentary and none of what little exists is related specifically to the Chilliwack.

Roots

The following root plants are reported to have been used as food.

- Bracken fern. The most important local root. The long rhizomes were dug by women with hardwood digging sticks, cooked, and stored. (Duff 1952:73)

- "Wild potato." Found locally in patches on low foothills and mountain slopes. A composite bulb like onion or garlic with a 2 foot stalk and a blue flower "something like a tiger lily." (Duff 1952:73)

- "Wild potato." Not found in Upper Stalo territory; imported from the Lower Stalo. Boiled or roasted in hot ashes before eating. Duff (1952:73) believes this to be the true camas.

- "Wild onion." A bulb that grew close to the river; eaten raw. (Duff 1952:73)

Three dried roots, surely used for food but not remarked upon by Duff's informants, were collected in 1913 in Tait country: Lilium columbianum, Balsamorhiza sp., and Lomatium sp. (Duff 1952:73)

Omitted in Duff's brief root roster is the common arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia = Chinook jargon wapato [Suttles 1951:277]). The Fort Langley Journal of October 5, 1828, observes that this root was then being collected by many Indians in Lower Stalo country, and that, dug under water in pools and marshes, these roots were held "in great estimation as an article of food" (Duff 1952:73). It is not clear whether they were also available in the upriver country of the Upper Stalo.

One very early historical reference to undoubted Upper Stalo use of roots is worth noting. When, in late June of 1808, Simon Fraser and his party traveled down the Fraser River, they were provided meals which included roots of some variety at two Tait villages (Fraser 1960:101). In the first case the meal consisted of salmon, oil, raspberries, and roots; in the second, of sturgeon, oil, and roots.

Women and their children, at least sometimes without men, went in

groups to the root grounds to collect these foods. On occasion, they

remained overnight. One of Duff's (1952:119) aged Tait informants

recalled one time long ago when six women and their offspring left their

village at the present site of Agassiz, camped at the foot of a mountain

to dig roots, and were visited just at dark by a s sxa

sxa (sasquatch) which

came into the firelight of their camp and attacked them.

(sasquatch) which

came into the firelight of their camp and attacked them.

Southern Vancouver Island and Puget Sound tribes and groups immediately inland from the Sound tended certain native roots to some degree and even replanted them: e.g., camas seeds, Indian or wild carrots, and tiger lily stems (Collins 1974a:55; Smith 1950a:336-337; Stern 1934:42-43; Suttles 1951:282, 1957:163-164, 164 fn. 23). Suttles believes that this primitive method of encouraging wild root growth was widespread in the area. But I have seen nothing to suggest that the practice extended north into the Fraser drainage. If it had, one might suppose that the Chilliwack, with their unusual back-country subsistence focus for a Fraser River people, would surely have been one of the groups most likely to have followed the pattern. In any event, it is in my mind an open question as to whether wild root tending was an aboriginal practice or a very early post-White borrowing, transferred quickly to local roots.

Berries and Other Fruit

Most berries preserved for winter consumption were gathered in late summer by parties of women and a few men who went into the mountains for a few days. The most important mountain berries to the Upper Stalo were four huckleberry (Vaccinium sp.) varieties: sweet blue huckleberries, found only at higher elevations; gray huckleberries, that grew on low bushes at higher elevations; blue huckleberries, similar to the sweet blue kind but less sweet and found on lower slopes; and red huckleberries, which grew on lower slopes. Generally dried immediately after being picked, they were piled an inch or two thick on a cedar-bark mat spread on a wooden rack about 4 feet above the ground. They dried in two or three days. Sometimes berry patches "were burned to improve their future yield." (Duff 1952:73)

A red, bitter berry that "looks like wild-rose-hips" and grows only at the upper elevations was mixed half and half with sweet blue huckleberries and the two mashed together. (Duff 1952:73)

The following berries were collected during the summer and either eaten fresh or dried for winter eating:

- Salmonberries. Eaten fresh.

- Thimbleberries. Eaten fresh.

- Wild trailing blackberries. Dried by being spread on mats in the sun.

- Blackcaps. Dried like the blackberries.

- Salal berries. Dried like the blackberries.

- June berries. Placed in a backet or small woden bowl and crushed with a small stone hammer. Spread to dry on maple leaves in the sun or covered with more leaves and hot ashes. Stored in the form of flat cakes.

- Elderberries. Crushed, dried, and stored as June berries were treated.

- Oregon grape berries. Eaten fresh, "either right off the bush or smashed to a pulp and mixed with water."

- Wild crab apples were common and were gathered and eaten fresh when ripe in late fall (Duff 1952:73-74).

I have uncovered only a single reference to Upper Stalo use of berries as food in the very early historical records. On his early summer journey of exploration of the Fraser River in 1808, Fraser (1960:101) and his party received raspberries from the people of a village near Hope, in Tait tribal territory, as a part of the meal served them.

For the Chilliwack specifically we have little berry information. But Charles Wilson of the British Boundary Commission mentions incidentally several berries which grew abundantly in some localities within the boundaries of traditional Chilliwack territory where he spent several summer and fall months in 1859. These, which were greatly to his taste, included:

- Black currants. When ascending the Chilliwack River on July 29, Wilson (1970:64) was shown by his Chilliwack guide "a first rate fruit garden"- -- wild, of course -- in the open valley upstream from Sleese Creek. Here were black currants "in profusion." On August 28 in a protected basin close by several glaciers in the high mountains along Sleese Creek near the international boundary, Wilson (1970:70) found these same black currants "in great profusion."

- Raspberries. Raspberries in abundance grew with the black currants in the berry patch visited by Wilson on July 29 (see above); indeed, "one species of raspberry, a large yellow one, was unequalled in flavour even by the best in the garden at home." Likewise near the Upper Sleese glaciers Wilson discovered raspberries in great numbers on August 28 (see above).

- Strawberries. On June 16 the prairie below the Chilliwack Canyon was "covered with ... strawberries," providing Wilson on the 19th with "a feast" as he walked over the area. High up the Sleese, strawberries were growing "in great profusion" on August 28 (see "black currants" above). (Wilson 1970:49, 51, 70)

- A "beautiful red berry which grew abundantly on a shrub" was also enjoyed by Wilson (1970:64), who found them in the "berry patch" beside the Chilliwack River on July 29 (see "black currants" above).

It cannot be doubted that all of these fruit were eaten by the Chilliwack.

A number of berries scarce or unknown in Upper Stalo territory were secured through trade. The following belong in this category:

- Serviceberries (Saskatoon berries). Scarce in Upper Stalo country. Obtained dried from the Thompson Indians. In general used as a sweetener and as such added to soups. (Duff 1952:74)

- Soopolallie berries (buffalo berries, foamberries). Obtained from the Thompson tribe. Beaten up to a foam for eating, with serviceberries added to sweeten the product. (Duff 1952:74; Clark 1976:324; Turner 1978:138)

- Cranberries. Grew near the Fraser River mouth. Obtained in late fall on visits or by trade. (Duff 1952:74, 76)

Minor Plant Foods

Green shoots were collected by the Upper Stalo and eaten raw in the spring. Among these foods were the shoots of salmonberries and of thimbleberries and round cow-parsnip stalks. (Duff 1952:74)

Of nuts, only hazelnuts were gathered. They were obtained in mid-September, put away to ripen, and later eaten uncooked (Duff 1952:74).

"Beard moss" (i.e., black tree lichen, Alectoria fremontii, I am sure) was secured "hanging from certain trees high up in the mountains." It was "boiled black" and dried as cakes, the so-called "moss bread." (Duff 1952:74; Turner 1978:35)

Meal Patterns and Preparation

Certain details of the preparation of fish and meat have already been presented. The following data are supplementary to those facts.

The Upper Stalo prepared food for consumption in three ways: by stone-boiling, roasting, and steam-roasting in earth ovens. Boiling was done in a basket or wooden trough. Roasting involved pinching the meat or fish in the split end of a fir stick and thrusting the pointed end into the ground near an open fire. The flesh was held open with twigs. Birds were kept turning to roast evenly all around. Details of the earth oven and of what foods were prepared in it are not reported. (Duff 1952:74)

Soups, made of fish, meat, roots, and berries, were a common Upper Stalo food. Certain conventions regarding the preparation and consumption of soups were observed: e.g., meat and fish were never mixed; the young were not allowed soup, because too much fluid made them become heavy. (Duff 1952:74)

The Chilliwack obtained a brownish salt from Cheam Peak and used it sparingly (Duff 1952:74). This peak is on the western end of Cheam Ridge, east and north of the mouth of Sleese Creek, and was just outside the Chilliwack boundary as plotted by Duff (Figure 2-1).

We have no information concerning the foods served in the typical Upper Stalo (much less Chilliwack) meal by time of day, season, condition of the food supply, and social status. This is, however, a matter of considerable importance, for this information represents part of the data base necessary for assessing the nutritional intake of the group under traditional subsistence conditions and the degree to which the minimum daily dietary requirements in proteins, fats, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals were met in the normal meal pattern.

Such data as are available for the Upper Stalo in general and the Chilliwack in particular on their methods of preparing foods for storage and subsequent consumption are discussed above. Here we are concerned with the preparation of foods for immediate eating and the serving of these as meals. Unfortunately, there are very few data.

Among the Upper Stalo food was ordinarily cooked, when boiled, in box-like baskets or wooden troughs, these latter sometimes more than 4 feet long and 10 inches deep. The water was heated with hot stones carried with "two pieces of wood with flattened, shovel-shaped ends." While salmon, at any rate those to be eaten in the annual first salmon ceremony, were sometimes boiled in a basket, they were on occasion boiled in a large stone bowl or a hole in a rock, the water heated as usual by hot stones, or they were roasted over an open fire. (Duff 1952:58,120)

Partially confirmatory evidence for the cooking of salmon comes from the early historical records. When exploring the lower Fraser River in late June, 1808, Simon Fraser and his party were served fresh salmon on several occasions as they passed through Upper Stalo country. The fish were either roasted or boiled with heated stones in wooden vessels (Fraser 1960:98, 99,115; see also 101,114). It is frequently reported that fish were cooked surprisingly quickly by this stone boiling method. Fraser (1960:115), however, makes a point that must be taken into consideration in estimating total meal preparation time. When, on his return journey upstream, he stopped at a Tait village in the Yale area, the villagers "spread mats for us, and put stones in the fire to heat in order to prepare us a meal. But this operation required more time than our situation would permit us to spare, and we took our leave."

No data are known to me describing Upper Stalo -- or, more specifically, Chilliwack -- methods by which game, roots, and berries were prepared for immediate eating, except as seemingly implied by Duff's very general boiling statement above.

Upper Stalo dishes were dugout vessels smaller than the boiling troughs and were made in various shapes. The Simon Fraser data agree at the general level: when, on June 28, 1808, he and his party reached the uppermost Upper Stalo village, they received from the villagers "plenty of Salmon served in wooden dishes." Upper Stalo spoons, with as much as a ten-inch bowl, were generally fashioned of a curved vine maple branch; their handles were sometimes carved by way of ornamentation. Mountain goat horn spoons were not in use. (Duff 1952:58, 59; Fraser 1960:98)

While apparently the same or essentially identical in material and form to those of the other Upper Stalo tribelets, some Chilliwack utensils were uniquely large examples of their types. According to Hill-Tout (1903:360-361, 394, 397), all persons of a single community ate their meals together. Consequently, the food for all villagers and for all meals was prepared and served together. The cooking and eating objects specifically mentioned for the Chilliwack are as follows: enormous "cedar troughs, 10 or more feet long and 2 or 3 feet wide"; wooden and basketry "kettles"; wooden bowls; big (i.e., ordinary) and small wooden platters; large maple dishes; wooden dippers or spoons; and horn ladles or spoons, known by a different native term from the preceding.

Food Ceremonalism

Although the data are scanty and to some degree contradictory, the result, in part, of the early adoption of certain Christian beliefs and practices, it appears that among the Upper Stalo the "first fruits" rituals were practiced for the first berries of the season, the first roots gathered, and the first salmon caught. (Duff 1952:98, 119, 120-121; Hill-Tout 1903:358)

The first fish, in some groups chinook and in others (including the Chilliwack) the sockeye, was harpooned by a single fisherman, wrapped in brush, taken to the big house where all persons had assembled, and boiled in a basket, boiled in a large stone bowl or hole in a rock, or roasted over an open fire according to the tribal custom. The fish -- in recent decades the deity or maker of the world -- was thanked by the chief, the fisherman who had taken the first fish, or the oldest man. The cooked salmon was divided among all present, each receiving a very small piece. Depending on the group, the bones were either returned to the water immediately or, wrapped in cedar bark, hidden for several years in the dwelling. The Chilliwack roasted their first sockeye over an open fire, as did the Lower Stalo. (Duff 1952:102, 119,120)

| TECHNOLOGY |

In this rather general section are collected data relating to objects and processes that either fail to fit naturally into other sections, as fishing implements do, or importantly involve two or more cultural complexes, as do the bow and arrow that were employed both in hunting and in warfare. The data are obviously far from comprehensive: many items of material culture and their attendant fabricating techniques and uses are not described or even marginally alluded to in the published literature.

Fire was kindled with a drill of vine maple or crabapple and a hearth of dry cottonwood root. The sparks were caught in dry moss. To start a fire quickly, glowing coals were transported in large clam shells. Torches were commonly made of fir pitch; sometimes sockeye heads were burned for this purpose. (Duff 1952:61)

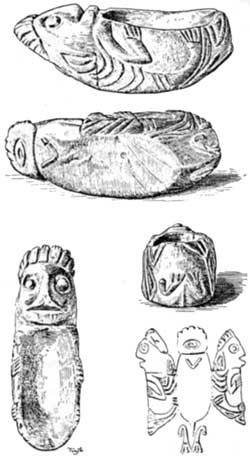

Artifacts of Fibers, Hide, Wood, Stone, and Anter/Horn

The basketry of the Upper Stalo and their neighbors was highly distinctive for its water-tight coiled variety and for its imbricated designs that sometimes covered and strengthened the entire basket. Coiling is a basketry construction technique in which a long element is coiled spirally from bottom to rim to build up the basket wall, being constantly sewed as the coiling proceeds to that part of the element that lies immediately below. Imbrication is a method by which an ornamenting element is applied horizontally to the exterior surface of the basket as the coil is carried around and is doubled over and pinched in place by the coil sewing element (see Figure 2-3). (Smith in Smith and Leadbeater 1949:112,125)

Figure 2-3. Techinque of ornamenting the coiled basket by imbrication.

A. Method, showing warp (a), sewing element (b), and imbricating element

(c). B. Appearance of completed basket. Design pattern is visible only

on exterior surface. (After Underhill 1945:104)

Upper Stalo baskets were woven by this process, the circling elements being either round coils of cedar-root splints or flat coils of cedar slats. Water-tight baskets were invariably made with the round coils; those for which this property was not essential were often woven of the flat elements. Chilliwack baskets were in all cases manufactured of split roots of young cedar trees. (Duff 1952:57-58; Hill-Tout 1903:360; Smith and Leadbeater 1949:124)

Owing to the structural requirements of the weaving process, the ornamentation of the entire basket through design and color repetition had to be visualized and planned by the weaver before beginning the basket construction. Traditional design elements among the Upper Stalo were generally geometric, nonrepresenta tional, and non-symbolic. By imbrication, white, red, and black patterns were produced. A marked preference was shown for a continuous design structure: the figures on all basket surfaces were skillfully related by their arrangement and/or color properties whether the basket was round or cornered like a tour-sided box. Individual designs were named, but were not owned as elsewhere in the coastal area. (Duff 1952:57; Smith 1949:115, 116; Smith and Leadbeater 1949:121-122, 124,131,132)

"Baskets among the Upper Stalo were of many types and had many uses." Large storage containers, usually of the round coil variety, held clothes and other valuables. Burden baskets, all water-tight, were made in many sizes. Round-mouth baskets served as work containers for weavers and others. (Duff 1952:57)

Woven mats, doubtless of different plant materials and fashioned by different weaving techniques, were used by the Upper Stalo in various ways, but the ethnographic data are very scanty. It is of interest that Fraser (1960:98, 115), when exploring the lower Fraser River in late June and early July of 1808, found mats being spread for his party on the floor -- presumably to sit upon -- when being given meals at Upper Stalo villages. The Chilliwack are specifically reported to have used mats for beds and for floor and seat coverings, the two forms being designated by different terms (Hill-Tout 1903:395).

Yarn was made by the Chilliwack from mountain goat wool and was woven into blankets (Hill-Tout 1903:400).

Nets of many types were used by the Upper Stalo -- dip and bag affairs in fishing, others in entangling ducks and snaring deer, and many other varieties (Duff 1952:58). Specific data for the Chilliwack are lacking, but there is no obvious reason for assuming that nets were of significantly lesser importance to them than to other Upper Stalo tribelets. Nor is there any evidence for believing that any of the net varieties mentioned above were not Chilliwack artifacts, though whether the dip and bag fishing nets were as important to them in early years, when they were back in their canyon, as among the Fraser River groups may be questioned.

Most nets were woven of Indian hemp fiber, generally secured in trade from the Thompson either coiled in its raw state or as finished twine, since little hemp was to be found in Stalo territory. The inner bark was twisted between hand and thigh into strands which, generally in pairs, were then twisted together to create a twine varying in thickness from thread to pencil-diameter. Netting shuttles, usually of maple and about 1 inch wide and 8 inches long, and rectangular maple mesh-measures with a center hole for the hand were used in the netting process. (Duff 1952:58)

"Rope was used to tie up drying-racks, tie on house planks, as anchor-lines, and for other uses." The best was fabricated of Indian hemp. However, long, green hazel sprouts and cedar withes were likewise fashioned into rope. In this process the bark was removed; the sprouts or withes were twisted and worked until soft and pliable; then three of these elements were laid side by side, the ends tied, and the three strands twisted together into a rope. (Duff 1952:58)