|

National Park Service

National Park Service Uniforms In Search of an Identity, 1872-1920 |

|

IN SEARCH OF AN IDENTITY

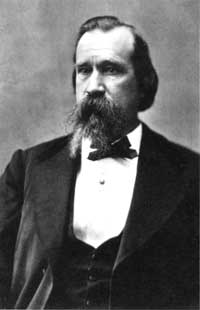

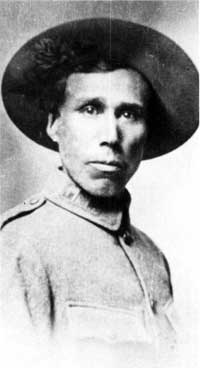

Harry S. Yount, c. 1873. Here is another photograph of Yount, probably taken around the same time as the previous Holmes image since he is wearing the same clothing. Yount is shown wearing skin clothing, but rangers more than likely wore a combination of regular military and civilian attire. Although traditionally thought of as the first park ranger, others were employed prior to him to assist the superintendent. NPSHPC - HFC/91-0023 |

Until the establishment of Yellowstone National Park in 1872 and even afterward, local inhabitants and visitors to the area treated the land as their own. Game was hunted, timber was cut, and nodules that had taken thousands of years to form were chipped from the geysers for souvenirs. It did not take long for Yellowstone's superintendents to realize that if they were to accomplish their assigned goal of protecting and preserving the park's natural features for posterity, they would need more help.

In 1880 Superintendent Philetus W. Norris hired Harry S. Yount as a year-round "game keeper." [1] Although Yount has traditionally been considered the first park ranger, others had previously been hired to assist the superintendent. He was paid the munificent sum of $1,000 a year, not bad considering that the total budget for the park was only $15,000. Even so, Yount worked for only one year, complaining that the park was too large for one man to patrol.

Yount was typical of many of the men roaming the West during this period. After Civil War service in the Union Army he went out to the Wyoming Territory, working as a bullwhacker, hunter, trapper, and for seven summers as a guide for the Hayden Geological Survey. [2] A photographic portrait taken in 1873 by William H. Holmes shows him in a regulation 1858 U.S. Army mounted overcoat, a skin (probably buckskin) jacket with a fur collar, a civilian shirt, and a wide-brimmed hat with the front pinned back in a rakish manner. There are three other images of Yount in the National Park Service photo collection. Unfortunately, none of them were taken around the time of his association with the park. One shows him standing, leaning on a Sharps buffalo rifle, wearing the same clothes sans overcoat. He has hide trousers and knee boots. This was probably also taken by Holmes. In another image taken by William Henry Jackson during the 1874 Hayden Expedition, he is shown at Berthoud Pass, Colorado. In the third image he does not have a beard and appears to be somewhat heavier. He is also wearing what appears to be buckskin clothing with fringes, along with the usual panoply of weapons. This photograph is harder to date but was probably not taken while Yount was employed by the park, being titled "Harry Yount, Hunter."

It is not known whether Yount was issued a badge for his Yellowstone service or if he displayed any other symbol of authority. More than likely he just adhered to the old western adage of "might makes right."

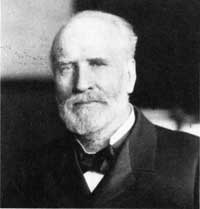

Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar, Secretary of Interior, 1885-1888. Secretary Lamar invoked the Congressional Act that brought the military into Yellowstone National Park on 18 August, 1886. LC - BH826-28955 |

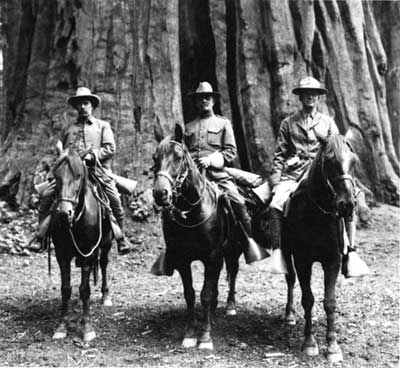

Uniforms first made their regular appearance in the national parks on August 18, 1886, when Troop M of the 1st U.S. Cavalry trotted into Yellowstone. The presence of the troops resulted from an act of Congress approved March 3, 1883, which stated, "The Secretary of War, upon the request of the Secretary of the Interior, is hereby authorized and directed, to make the necessary details of troops to prevent trespassers or intruders from entering the park for the purpose of destroying the game or objects of curiosity therein, or for any other purpose prohibited by law, and to remove such persons from the park if found therein." On August 6, 1886, Secretary of the Interior Lucius Q. C. Lamar, deeming that Yellowstone could not be adequately protected by the civilian administration, requested troops from the War Department. The request was approved on August 10 and troops from Fort C.F. Smith were ordered to Yellowstone. [3] Other cavalry units were detailed to Sequoia, General Grant, and Yosemite in California after those national parks were established in 1890.

Initially the cavalry units patrolled Yellowstone and the California parks only during the summer months, but later their presence was extended. Soldiers in campaign hats, boots, and olive drab uniforms were a familiar sight to park visitors until 1919, three years after the act creating the National Park Service.

Yellowstone Park Scout Badge, c. 1894-1906. Issued to civilian scouts hired by the military to help protect Yellowstone National Park. Scouts were issued nickel-silver, while those of the chief scouts were sterling silver. NPSHC |

After the Lacey Act of 1894 prohibited hunting in Yellowstone,

civilian police, called scouts, were employed for wildlife protection.

This term was no doubt used because the Army had hired civilian scouts

for other purposes. Scouts were also required to stop the grazing of

livestock, mainly sheep, by local ranchers on park grounds. Since these

scouts, or rangers, were more or less dependent on the Army

quartermasters for their supplies, their dress was a combination of

military and civilian clothing. They were also issued a badge of

authority. For Yellowstone National Park, this consisted of a two-inch

circle with "YELLOWSTONE PARK SCOUT" stamped in it. The middle of the

circle was cut out to form a star with the badge number in the center.

The badge was similar to many of those issued to lawmen of the

period.

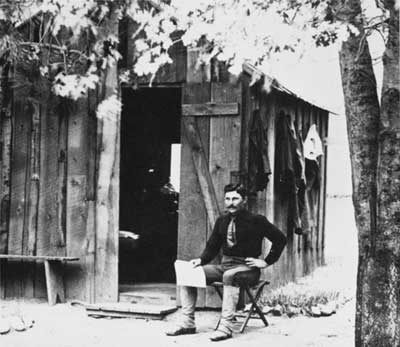

Most patrol duties still fell to the troopers in Yellowstone and the California parks. Sometimes they rode in mounted patrols and other times they might be at some lonely strategic spot with a shack and the animals for company. The National Park Service has a photograph depicting Gabriel Souvelewski at just such a place in 1896. As a member of Troop K, 4th U.S. Cavalry, he patrolled Yosemite National Park between 1895 and 1897. During the Spanish-American War his troop was sent to the Philippines. Apparently he was discharged either before the troop shipped out or shortly after its return, for in 1899 he was a civilian packer and guide with the Army at Yosemite. In 1906 Souvelewski was hired as supervisor for Yosemite, beginning his distinguished thirty-year career in the park's civilian ranger service. [4]

Gabriel Souvelewski on patrol in Yosemite National Park, c. 1896. He was a sergeant in Troop K, 4th US Cavalry. In 1906, Gabe became civilian supervisor at Yosemite, beginning thirty years of distinguished service. NPSHPC - YOSE/RL-2751 |

Guard duty at Teddy Roosevelt's camp at Yellowstone National Park, 1903. NPSHC - YELL/65,305 |

Souvelewski's picture shows him in the standard Army undress uniform worn in the parks: dark blue wool shirt, sky-blue trousers, canvas leggings, and shoes. Because he is an NCO his trousers have a dark blue stripe down the side. Although the soldiers in the 1888 photograph of the Soldier Station at Yellowstone are dressed more informally, they were probably pulling fatigue duty. Trooper Souvelewski typifies the dress of the soldier on patrol. In the spring of 1898 the military units designated for the parks were sent to Secretary of State John Hay's "splendid little war" in Cuba and the Philippines. During their absence, their place was taken by civilians, hired on a temporary basis and designated as forest rangers. Some of these rangers remained on duty even after the return of the cavalry late that summer.

Army in the Parks

2nd Lt. Johnathan M. Wainwright (of WW II Bataan fame), Officer of the Day, 1st US Cavalry, #7 Guard Mount at Fort Yellowstone, Yellowstone National Park, early 1900's. NPSHPC - YELL/65,342 |

Soldiers performed all kinds of duties in the parks, like fighting the fire at Cottage Hotel in Yellowstone National Park, 1910. NPSHPC - YELL/65,385 |

This is the first detachment of soldiers to be stationed in Yellowstone National Park. They are from Troop K, 1st U.S. Cavalry, even though the long rifles would make them appear to be infantry. They became the first regular uniformed presence in a national park when they rode into Yellowstone on August 18, 1886. NPSHPC - F.J. Haynes Photo - YELL/65,358 |

|

|

|

Left: Soldiers passing through Wawona tree, Mariposa Big Tree

Grove, Yosemite National Park. UPR/10199 Top right: Last "sun-down" gun fired by military in Yellowstone National Park, July 31, 1916. NPSHPC - YELL/65,325 Bottom right: Mounted infantry patrol, 24th "Black" Infantry, Yosemite National Park, c. 1899. NPSHPC - YOSE/WASO 82-39 | |

Forest Reserve Ranger Badge, 1898-1906. This badge was probably issued to forest and park rangers since both were called FOREST RANGERS. Private Collection |

The first permanent appointment of rangers in a national park occurred on September 23, 1898, when Charles A. Leidig and Archie O. Leonard became forest rangers at Yosemite. The authorization letter stated that they were to be compensated at the rate of $50 per month and that "Each Ranger is required to provide himself with a saddle horse and equipments at his own expense, for use in the discharge of his duties." [5] Dress was apparently optional, but the rangers were issued badges to show their authority. It is not known for certain what these badges looked like, but there is a badge in a private collection that was issued by the Department of the Interior to the rangers in its forest reserves. It is the same size as the "Yellowstone Park Scout" badge (two inches in diameter) and made of German silver. In the center there is a "US" in one-inch letters with "Department of the Interior" superimposed. Around the outside it reads "FOREST RESERVE RANGER." All of the rangers were called "forest rangers' whether they worked in the parks or the forest reserves. Because all were employed by the Interior Department and did more or less the same job, they more than likely were all issued this same badge.

| |

|

Left: James Wilson, Secretary of

Agriculture, 1897-1913. Secretary Wilson acceded to Secretary

Hitchcock's request to have the Forest Service pay the four rangers that

remained with the Park Service at the 1905 separation until the Bureau

obtained it's own funding. LC / USZ6-1817 Right: Ethan Allen Hitchcock, Secretary of the Interior, 1899-1907. LC / USZ62-66577 | |

William Watts Hooper, c. 1900. Hooper was appointed forester in the Kenosha Range country sometime after 1887 and remained with the Forest Service in the 1905 separation. He is shown wearing the 1898 Forest Reserve badge. Forest Service / 477445 |

On February 1, 1905, an act of Congress transferred the forest reserves from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture. Along with this went the money to pay the rangers in the parks, thus, in effect, making them among the first employees of the new Forest Service. Secretary of the Interior Ethan Allen Hitchcock, in an exchange of letters with Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson, outlined the history of the rangers in the parks and asked to maintain some of them in their present status until July 1, when Interior would again have funds for them. Wilson agreed and asked which rangers wished to remain with the parks. Four of them expressed their desire to remain: Archie Leonard and Charles Leidig in Yosemite and Lew Davis and Charlie Blossom in Sequoia. [6]

Earnest Britten, c. 1900. Britten was ranger-in-charge at Sequoia National Park from 1900 until 1905 when he elected to go with the Forest Service, at which time Walter Fry was appointed to his position. NPSHPC - HFC/91-25 |

The year 1905 also saw the appearance of Walter Fry, one of the first new rangers after the separation and an early advocate of uniforming the ranger force. Fry transferred from Sequoia's construction department to the rangers. A few months later, because of his higher schooling, he was promoted to replace Ernest Britten, who had elected to go with the new Forest Service. This promotion made him ranger-in-charge during the summer and acting superintendent during the winter months when the Army was absent. [7]

Even after the departmental separation of the parks and the forest reserves, rangers in the parks still considered themselves forest rangers. Acting Secretary of the Interior Thomas Ryan sought to overcome this habit in an October 2, 1905, letter to Fry: "It is observed that in your official communications to the Department you designate yourself as a Forest Ranger. Such designation is erroneous, your official title being Park Ranger, and official papers should be signed that way." [8] Even so, the park rangers still thought of themselves as forest rangers for some time thereafter.

Forest Service rangers, 1907. These Forest Service rangers are demonstrating their new uniforms. These were the first uniformed civilian personnel in and around National Parks. NPSHPC - HFC/92-28-47 |

The first regulation civilian uniform to make an appearance in and around the parks was worn by the Forest Service, not the Park Service. As chief of the Bureau of Forestry, Gifford Pinchot had been thinking of uniforming the rangers since 1903, when he was impressed by the efforts of the U.S. Geological Survey to have field men wear standardized clothing. When he became head of the new Forest Service in 1905, one of his first projects was to appoint a committee to select a uniform for the rangers. The Forest Service began soliciting bids in September 1905 and had selected a design and supplier by the fall of 1906. The new uniforms were delivered in 1907. [9]

According to Forest Service historian Frank Harmon:

The first uniform jacket was a compromise between the current Army officer's service coat and the business sack coat. It was brown with a green cast, and the material was wool worsted. It had a low turn-down collar, no lapels, four outside pockets with cover flaps, and five bronze buttons to close. Each pocket also had a small button. The buttons were convex with "FOREST SERVICE" and a pine tree in a raised design. The coat collar could be left open, or closed tightly with a clasp, military style. Worn with the uniform, from the very beginning, was a large bronze badge. The first hat was the same as the Army campaign hat—light colored felt with a wide, flat, stiff brim, but usually worn with a high "Montana peak" instead of the Army's single crease. There was a choice of trousers or riding breeches, both of wool worsted. The shirt was gray flannel like the Army's pullover olive drab. [10]

Although the Forest Service rangers were beginning to be uniformed at this time, the park rangers were still wearing civilian clothing, with only their badges to show that they were park officials. Platt National Park was an exception. The rangers there began wearing olive drab uniforms, similar to those worn by the military, soon after the separation. These were furnished by the M.D. Lilly Company of Columbus, Ohio. [11]

Rangers of Sequoia National Park near old Britten store, c. 1902. This photograph shows the typical pre-uniform dress of rangers in the national parks. The one unusual thing about their attire is the two badges. It is not known if other parks utilized this system since the only extant images are from Sequoia. Left to Right: Lew Davis 1901-1909; 1924-1929; Ernest Britten 1900-1905; transferred to Forest Service; Charles W. Blossom 1901-1916; Harry Britten 1902-1903; 1906-1915 NPSHPC - SEQU/8886 |

The National Park Service photo collection contains two photographs of four rangers in Sequoia probably taken in the summer of 1902. The images show Ernest Britten, Lewis Davis, Charlie Blossom, and Harry Britten, Ernest's nephew, holding their horses. Harry Britten was hired as a ranger in 1902. While on patrol in March 1903 he accidentally discharged his pistol into his right thigh, requiring the amputation of his leg above the knee. A year and $1,000 worth of medical expenses later Harry was fitted with an artificial leg; upon learning to walk with it, he was hired in a clerical capacity in the Sequoia Forest Reserve. Capt. Kirby Walker, acting superintendent of Sequoia National Park, thought that because Harry had been on duty when the accident occurred and had not received any compensation from the government for his expenses, it was only fair that he should be rehired to fill a new slot in the park's ranger force. The secretary of the interior concurred and in July 1906, Harry was back on the Sequoia ranger force, artificial leg and all. (His uncle had elected to go with the Forest Service in the 1905 split.) [12]

In the photograph, the rangers are wearing two badges, a round one above one shaped like a shield. The round badge is almost certainly the Department of the Interior forest reserve ranger badge because it conforms to the size and shape of the badge worn by forest reserve rangers in other photographs. The lower one appears to be some sort of patrol badge. It is not known if other parks were utilizing the same combination of badges because the only available photographs of rangers during this period were taken at Sequoia.

Walter Fry, 1920, Sequoia National Park. Taken while Fry was guiding House Appropriations Committee during visits to national parks in 1920. He is wearing the 1920 uniform with Army wrap-leggings. NPSHPC - J.W. Good Album - HFC/92-40-1 |

The fall of 1907 also saw the first documented request for a "park service" uniform. Walter Fry, now ranger-in-charge at Sequoia and General Grant national parks, asked the secretary of the interior to authorize a ranger uniform on the pattern of the Forest Service, but made out of cadet gray wool with bronze eagle buttons. He enclosed material samples of cadet gray wool from the Charlottesville Woolen Mills in Virginia. He felt that the uniform "would add much to the comfort and appearance of the Ranger." [13]

In response to Ranger Fry's request, Acting Secretary Thomas Ryan stated that he had made inquiries and found that the Forest Service rangers purchased their own uniforms. He asked whether the rangers at Sequoia and General Grant would be willing to do the same. Fry said they would provided that "Cadet Gray cloth is adapted." [14]

The following February Assistant Secretary Frank Pierce sent letters to other parks relating Fry's request and informing them that the department was considering "the advisability of extending to the rangers in other parks, if desirable, the same privilege." He wanted to know whether rangers would pay for a uniform if one were authorized. Based on the cost of the Forest Service uniform, he estimated that for coat, trousers, overcoat, and "Stetson hat" the cost would be $38. [15]

Col. Albert R. Green, superintendent, Platt National Park, 1907-1909. NPSHPC - CHIC/2412  Maj. Harry Coupland Benson, assistant superintendent, Yosemite National Park, 1905-1908. Photograph was taken in 1910 after his promotion to Colonel. NPSHPC - YOSE/RL-2477 |

The answers to the inquiry were as varied as they were interesting. With but one exception, the superintendents agreed that the uniforming of the park rangers was a good idea. One who favored uniforms thought they should be voluntary, and another thought that superintendents should be exempted. Superintendent Albert R. Greene of Platt replied that the rangers there had been wearing a uniform of sorts for several years. It consisted of blue denim or olive drab wool shirts and khaki canvas breeches and leggings, at a cost of $8.80, for summer and olive drab wool coat and breeches and leather puttees, at a cost of $27.85, for winter. The latter was "made to measure" and furnished by the M.C. Lilley Company of Columbus, Ohio. [16] The lone dissenter was Maj. Harry Coupland Benson at Yosemite National Park. "I do not beieve [sic] it a good plan for the Rangers to appear in uniform for, from the nature of their duties, they should be as inconspicuous as possible," he stated. "They have badges under their coats which they can show in case they need to make arrests, seize guns, etc., and they would be much more apt to get information of wrong doing by appearing as an ordinary mountaineer than by appearing in a light uniform, visible from a great distance." He also considered cadet gray "a bad color to show dirt." [17]

Even though the rangers in all of the parks queried had expressed willingness to purchase uniforms at their own expense, Assistant Secretary Pierce replied to the superintendents on March 17, 1908, that "the Department, after due consideration of the matter, does not deem it advisable at this time to adopt any uniform for employs in the several National Parks." [18] He told Superintendent Greene that the department had no objection to the clothing adopted at Platt.

A year later Acting Superintendent George Allen of Mount Rainier National Park started a long correspondence with the secretary's office concerning uniforms in the park. Allen thought it "desirable that the Rangers at Longmire Springs should be provided with a suitable uniform." If there was not an authorized uniform, could the rangers purchase their own? He figured that because the rangers in the adjacent Rainier National Forest were not uniformed, there would not be any confusion if they purchased Forest Service uniforms and simply changed the buttons, although "an entirely different design would be preferable." [19]

Assistant Secretary Jesse E. Wilson replied that "upon investigation of the matter in the spring of 1908, the weight of opinion of superintendents or employees as to the advisability of prescribing a uniform for general use was found to be against such a course." He said that forcing rangers to purchase uniforms would work an unnecessary hardship on them when the "National Park Service" badge was sufficient identification for "National Park Service employees" and that "no adoption of a uniform for the National Park employees is contemplated at this time." [20] (Wilson's interpretation of field opinion on the subject was clearly questionable.)

It is interesting to note that around this time, as evidenced by Wilson's letter, "national park service" was being used in reference to Interior employees working in the parks even though there was no such official organization.

Forest Service button, 1907. This is the type button worn on uniforms purchased by Sequoia rangers prior to the Department authorizing an official uniform in 1911. Private Collection |

Walter Fry was not deterred by the lack of departmental support. Beginning with the 1909 season, the rangers at Sequoia and General Grant began purchasing and wearing "ready-made suits" of "Forestry worsted wool cloth, military cut; also olive drab wool shirts and regulation Stetson hats" from the Fechheimer Brothers Company, and Regal Shoe Company pigskin leggings for patrol duty plus "denim garments" for fatigue. [21] A portrait taken around 1910 of Karl Keller, one of the rangers at Sequoia, shows him wearing a uniform coat with what was termed the English convertible collar, complete with Forest Service buttons and a sprig of sequoia on his sleeve. The only insignia shown is an Army-style U.S. on the left lapel running parallel with the collar. At first it was thought that this was possibly an example of the more casual style (versus the military) of the 1909 Forest Service coat, especially because it was of "forestry" green wool, had Forest Service buttons, and was purchased from the company that furnished Forest Service uniforms. But upon comparison with the order forms from the Fechheimer Brothers Company, the supplier of Forest Service uniforms, it was found not to conform to their drawings. (It had upper pockets and different pocket flaps, among other variances in details.) It probably was a standard design of some kind, but because the picture shows only from the top of the upper pockets, it is impossible to determine what the rest of the coat looked like or its origin. There is always the possibility that it was an original design, but that is doubtful.

Karl Keller, 1910. Ranger in Sequoia NP, 1908-1917?. Keller is wearing one of the uniforms purchased by the rangers in Sequoia prior to one being authorized by the Interior Secretary. Note U.S. on collar, Forest Service buttons and sprig of Sequoia on sleeve. Photograph given to Lawrence F. Cook by Keller's daughter, Erma Tobin. NPSHPC - Hammond photo - HFC/WASO-D-726A |

Edward S. Hall, superintendent 1910-1913 (left) & Ethan Allen, superintendent, 1913-1914, Mount Rainier National Park. NPSHPC - Brockman photo - MORA/MR:E-T33.1 |

The beginning of each new season seemed to bring out more than the spring flowers. On April 23, 1910, Superintendent Edward S. Hall of Mount Rainier picked up the baton from George Allen and made another run at the department for uniforms. He recommended that park rangers be required to wear distinctive uniforms while on duty in the park. He considered this very important for those rangers that came in contact with the public, "especially those that are stationed on the government road and have charge of the automobile and other traffic." During the previous season there had been instances where rangers had "endeavored to stop automobiles on the road and no attention was paid to their signals." Hall reasoned that this was a result of "the rangers appearing in the dress of a laboror [sic] or at any rate not wearing anything asside [sic] from a Park badge to distinguish them from any other man who might happen to be on the road." He said that conditions along the government road in his park were "somewhat different from those in other National Parks and may require different treatment." He had secured samples and prices from the firm that furnished uniforms to the Forest Service. A suitable uniform could be purchased for $15, which he did not consider a hardship for rangers. [22]

Acting Secretary Frank Pierce replied that "in view of the situation in the Mt. Rainier National Park, especially on the government road, it would seem desirable to have the rangers on duty at the entrance of the park uniformed." Before making a decision in the matter, he wanted to know how many rangers would be uniformed and he wanted a material sample. [23]

Richard Achilles Ballinger, Secretary of Interior, 1909-1911. LC/USZ62-97993 |

Hall thought it would be advisable to have the rangers stationed at the entrance and Longmire Springs and the one that had charge of timber sales be uniformed. He enclosed a material sample, stating that he believed that "either this or khaki" would be suitable because the uniform would only be worn during the summer. "A coat made with military colar [sic] out of this material costs $7.55 and trousers $4.45," he wrote. "Regulation U.S. Army buttons to be used on coat." [24] This was probably based on the Model 1910 Army uniform, with the standing-fall collar.

In its answer, the department did an about-face. Secretary Richard A. Ballinger now thought "the question of adopting a uniform had best be deferred until the Department is able to determine the exact number of permanent rangers that can be provided for patrol duty in the park." He added that because of the rangers' low pay, "it is not believed that they should be required, at their own expense, to provide uniforms." [25]

The 1911 season opened with the annual missive from Mount Rainier, by now sort of a tradition, to the department concerning uniforms. This time Hall requested that the department provide $30 from the park's revenues for uniforms for two temporary rangers and require the ranger at Longmire Springs to furnish his own. [26]

Maj. William Logan, superintendent, Glacier National Park, 1910-1912. Logan, apparently tiring of Departmental waffling, arranged for Parker, Bridget & Company in Washington, DC, to furnish uniforms for Glacier's rangers, thus more or less forcing the Department to present this option to the other parks. NPSHPC - GLAC/HPF# 9623 |

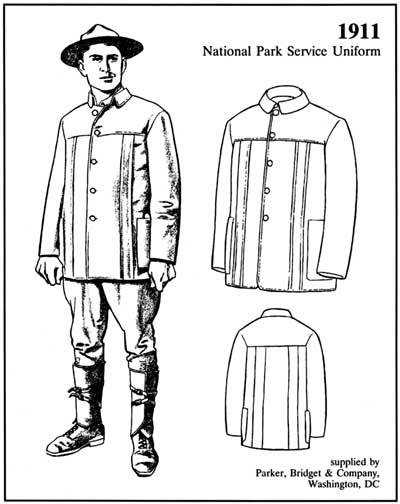

This year was to be different. Maj. William R. Logan, superintendent at Glacier National Park, had arranged for Parker, Bridget & Company of Washington, D.C., to supply uniforms for his rangers. The uniform consisted of "one Norfolk jacket, one wool shirt, one pair riding trousers, one pair leggings, and one felt camping hat after the Stetson style," all for $15. [27] Bowing at last to the constant requests for some type of uniformity within the various parks, the department decided after examining the material and information submitted by Major Logan to sanction, but not require, this uniform to be used throughout the parks. Letters stating this were sent to all parks, along with measurement blanks. Rangers would be required to purchase their own uniforms, but all transactions were to be handled through the secretary's office. [28] Logan promptly forwarded orders to the secretary's office for seven uniforms, and two more six days later. [29] In all, fifteen rangers from Glacier were uniformed in 1911.

U.S. Army button, c. 1910. Private Collection |

Material samples attached to a letter from Parker, Bridget, & Company to W. Bertrand Acker, an Interior Department attorney, show that the uniforms were of a dark olive green wool. They were "equipped with United States Army buttons." The matter of special park service buttons was raised but dropped pending the determination of the future of the "national park service." [30]

In response to the department's letter authorizing the Glacier uniform, Walter Fry wrote that the rangers at Sequoia and General Grant had been wearing uniforms of "Forestry worsted wool cloth" since the 1909 season, but that "last season word was received from Fechheimer Bros., that the Forestry worsted cloth could be furnished us no longer, as some of the Forest officers objected to our using it, since which time no more of the suits have been purchased." Fry asked the department to "grant them the privilege of purchasing, at their own expense, uniform suits manufactured from either the Forestry worsted olive green wool goods, or Cadet gray wool cloth, fashioned after pattern now worn." He went on to explain that his rangers carried fatigue clothing in their saddlebags when on patrol, putting it on whenever necessary. Afterward they could bathe, change back into their uniforms, and continue their usual routine in a "comfortable and respectable manner." He reported that since the rangers had been uniformed, they commanded more respect from the tourists and general public than when they had worn mixed clothing. [31]

In response to Fry's letter, Chief Clerk Clement Ucker asked Bertrand Acker to consider whether the department should compel all the national parks to adopt one style of uniform. If he opted for the one-style approach, the superintendent at Sequoia should be informed as such; otherwise he should be advised that strict compliance was not required. [32]

Maj. James B. Hughes, 1st U.S. Cavalry, superintendent, Sequoia National Park 1911-1912. NPSHPC - SEQU/02881 |

Assistant Secretary Carmi A. Thompson subsequently wrote Maj. James Bryan Hughes, Sequoia's acting superintendent, outlining the uniform being furnished by Parker, Bridget & Company. He identified the "wool shirt" as the regulation Army shirt, which means that it was olive drab with a plaquet front. The uniform was for summer wear only. He enclosed material samples and order blanks in case the rangers desired to order suits for themselves. "If they are not satisfactory, and it is so stated, the Department will then authorize the rangers to provide, at their own expense, suitable uniforms of Forestry worsted olive green wool goods, or Cadet gray wool cloth," Thompson wrote. [33]

Possibly because they had been wearing the forestry green wool for the past two seasons, the rangers did not jump at the authorization of the cadet gray they had been so adamant about before. Or it could have been that they were just satisfied to have an authorized uniform in the parks. At any rate, Fry immediately ordered one of the uniforms for himself. [34]

The first truly authorized park ranger uniform finally arrived at a national park in late June 1911. Of the 15 coats that the Glacier rangers received, six had Forest Service buttons, which were subsequently changed. [35] There is a photograph in an album assembled in 1915 by a Mr. Anderson showing two men at Glacier with one of them wearing this uniform, but it was probably taken in the summer of 1911 when the new uniforms arrived. The coat is of the Norfolk style, sans belt, which is not very flattering to the wearer. The rest of the uniform—breeches, hat, puttees, etc.—is standard fare for the period. The other man is wearing a 1910 Army uniform, although he was probably not a soldier because his coat lacks ornamentation. Possibly he was included in the photograph to show that the new park ranger uniform did not conflict with the military.

First authorized National Park Service uniform, Glacier National Park, c.1911. Man on right is wearing the new uniform authorized by the Department for rangers in the national parks. Glacier received 15 sets in June, 1911. Man on left is wearing a Model 1910 US Army uniform, minus military insignia. NPSHPC - 1915 Anderson photo album - GLAC/HPF# 9638 |

Apparently the rangers at Glacier were still using a separate fatigue uniform, for in October 1911 Parker, Bridget & Company thanked Chief Clerk Ucker for a check from Major Logan for "two blue shirts." [36]

As the 1911 season came to a close, the rangers at Sequoia realized that their new uniforms were not going to be warm enough for the winter months. Fry requested authorization from the department to purchase heavier uniforms, with "bronze Army buttons, bearing design of eagle, same as our badges now worn." If the forestry worsted olive green could not be worn, he wanted cadet gray. Parker, Bridget & Company was contacted and a price of $25 per suit and $30 for an overcoat, either military or Chesterfield, was received, along with uniform and overcoat material samples of dark olive green wool. The uniforms were to be the same pattern as the ones furnished in the summer. [37]

|

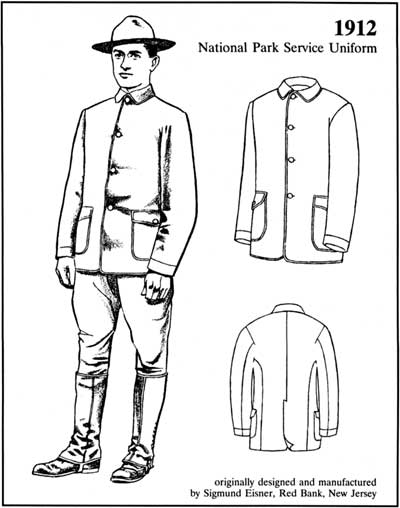

The department considered these prices excessive. Consequently inquires were sent, along with material samples, to C. Kenyon & Company of Brooklyn, New York, and Sigmund Eisner of Red Bank, New Jersey, both manufacturers of uniforms for the U.S. Army. (No material samples remain with the correspondence, but it is supposed from the response of Sigmund Eisner that they were pieces of the sample wool originally sent by Parker, Bridget & Company to the department.) C. Kenyon & Company declined to bid, but Sigmund Eisner did respond requesting the design of the uniform desired. They included samples of their "U.S. Forrestry [sic] Standard" cloth and stated that they could provide bronze Army buttons for the uniforms or could have buttons made of any design wanted and would stock them, subject to orders of the department. [38]

Subsequently, in a meeting with Chief Clerk Ucker at the Interior Department, the subject of olive drab Army wool for the uniforms instead of forestry green was broached. Afterward Eisner sent samples of olive drab cloth and prices of $15 for the overcoat and $16.50 for coat, vest, and breeches. The total came to $31.50, versus $55 from Parker, Bridget & Company. "I think the color of the 16 oz. Kersey is really more practical than the dark green and has extra wearing qualities," Eisner wrote. [39]

The department finally made up its mind concerning what color, if not design, the uniforms the rangers in the parks would wear. After one season of forestry green, it would now be olive drab. One must wonder what the rangers who bought uniforms the year before thought about this. They probably appreciated the style change, though. The Norfolk look certainly did nothing for their image.

1912 National Park Service button. Designed by Sigmund Eisner using 1905 National Park Service badge as a model. NPSHC - HFC |

In January 1912 Assistant Secretary Thompson wrote Sigmund Eisner requesting prices for summer uniforms made from the 13-ounce olive drab cloth sample they had submitted. He also requested sketches of both summer and winter uniforms, plus over coat, "together with advice as to whether bronze buttons bearing the eagle design surrounded by the words 'National Park Service, Department of the Interior,' as used upon the park ranger service badge shown you, will be procured and placed upon the uniforms." [40] The "National Park Service" buttons thus preceded the bureau by four years. The inscription on the badge is further evidence of the even earlier currency of the term "National Park Service."

1905 National Park Service ranger badge. Came into use by park rangers after separation of Services in 1905. HPSHC - HFC |

The badge was stamped and either tin or nickel-plated. It was two inches in diameter with a rope edge. The words NATIONAL PARK SERVICE * DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR surrounded an eagle similar to the one used on the Interior seal at this time. It is not known exactly when this badge came into use, but it was probably soon after the forest reserves left Interior for Agriculture. Because Gifford Pinchot had a new badge made for the Forest Service rangers, it is reasonable to assume that the Interior Department did likewise for the rangers in the parks. There is no doubt about its being used by 1911 when Eisner met with Chief Clerk Ucker.

Eisner agreed to the terms, and the sketches were drawn up and forwarded, along with the prices for the summer uniform, to the department shortly thereafter.

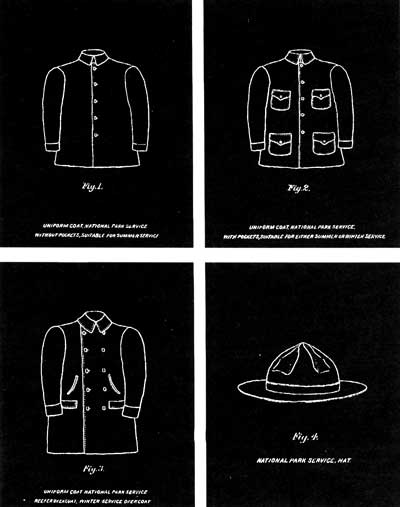

Drawings of 1912 National Park Service uniform furnished by Sigmund Eisner, Red Bank, New Jersey. NPS Archives - YELL |

The summer uniform, consisting of coat, pants, and vest, cost $14.25, with the winter uniform being fifty cents more. The difference stemmed from pockets and a heavier lining on the winter version. Winter service leggings were an additional $3.50. The sketches show uniform #1 (summer) to be a five-button coat with out pockets, with narrow cuffs on the sleeves. Uniform #2 (winter) is the same except for four pockets, two upper and two lower. The double-breasted reefer (overcoat) has two slash pockets and two bottom pockets with plaquets. Buttons were to be made up in different sizes for the coats, cuffs, and pockets. [41]

Two items of the uniform had been overlooked in the prices submitted by Eisner: summer leggings and hats. Ucker requested prices for the leggings and for "hats (Alpine or other style—Alpine preferred) for use with both summer and winter service uniforms."

He also requested a sketch of the Alpine hat. Eisner forwarded the requested sketch along with a price of $1.00 per pair for summer leggings. "Hats (of which I enclose sketch) made of grey felt, and similar to those worn by the U.S. Army would cost $1.50 each," he wrote. "You will note this hat is Alpine shape and same as used by the United States Geological Survey." Before any of the "Alpine" hats were purchased, the department asked that they be of a better grade and "a color conforming more nearly to that of the cloth (olive drab)." The upgrade resulted in a price of $2.50 for the hat. [42]

Twenty copies of the Eisner drawings were made at the department and forwarded to the various parks. Yellowstone still has a copy of these drawings in its archives. They confirm that the summer coat was intended to have no outside pockets, while the winter version was originally intended to have four. From the sketch of the hat, "Alpine" evidently meant a hat similar to the Stetson, only with a stiff brim and what is known as a Montana peak in which the crown is indented in four places, similar to the modern hat only much more severely, to bring it to a point.

|

The uniform resembled the one worn by the U.S. Army enough to cause concern at the department. Assistant Secretary Thompson wrote the secretary of war asking if there was too close a resemblance. The War Department had no objection. Even though the material was the same as that of the Army uniform, "the difference in cut and absence of insignia, etc.," would prevent any confusion with the military. [43]

On February 19, 1912, letters were sent out to all parks outlining the new olive drab uniforms being considered by the department for the rangers. They were described as follows:

Winter service: 16 oz. olive drab cloth, coat, as per sketch #2, vest, pants or breeches, leather puttees, and hat, Alpine style per sketch #4. Cost: $22.50

Overcoat, double breasted, knee length, 22 oz. olive drab cloth, with either quilted or lasting lining, per sketch #3, $15.00

Cost of uniform with overcoat: $37.50

Summer service: 13 oz. olive drab cloth, coat, sketch #1, with two inside pockets, but no outside pockets, pant or breeches, vest, hat, Alpine style, sketch #4, and leggings. Cost: $18.00

Coat, sketch #2, four outside pockets. Cost: $7.50

Extra pockets, $.50 each.

The uniforms were to have "National Park Service" buttons. No shoes or boots were mentioned. It was further thought that to differentiate the ranger uniforms from the military, either the two upper or the two lower pockets of the coat should be eliminated from sketch #2. The various parks were invited to express their opinions in this matter. [44]

The consensus of park opinion was that if pockets had to be eliminated, they should be the two upper ones, but that there should be one or two inside pockets. None of the rangers wanted vests, but there was some interest in shirts. Ranger Fry at Sequoia included an order for five of the new uniforms with his reply. [45]

When the order for the uniforms for Sequoia was sent to Sigmund Eisner, a uniform for Laurence F. Schmeckebier of the secretary's office was also requested, as was a price for shirts. The price returned was $2.75 each for shirts made from "U.S. Army standard cloth," an olive drab flannel. "These shirts are made with turn down collar and two outside pockets same as U.S. Army regulation shirt," Eisner said. He also agreed to install two inside pockets in the coats, instead of the outside top pockets, for the same price. [46]

The rangers, or scouts, as Lt. Col. Lloyd Milton Brett termed them, at Yellowstone declined using the uniforms, since their duties were "more in the line of protection of game from poachers, and other detective work where plain clothes are not only preferable but sometimes absolutely necessary to efficient work, as a uniform could be too easily recognized at distance by offenders." The other parks seemed not to have the same problem, for uniform orders started rolling in. Most were for the #2 (winter) style with the two outside bottom pockets. Rangers Earl Clifford and Phillip E. Barrett at Mount Rainier ordered the #1 (summer) style coat (no outside pockets), only to be informed that because all the other coats ordered had the two bottom pockets, theirs would be ordered the same way. They were asked to forward the extra $.50. [47]

Lt. Col. Lloyd Milton Brett, acting superintendent, Yellowstone National Park, 1910-1916. Col. Brett collaborated with Mark Daniels when he designed his new uniform in 1915. NPSHPC - YELL/65,352 |

Charles W. Blossom, Sequoia National Park, 1901-1916. Charlie is wearing the 1912 National Park Service uniform coat. (no top pockets) He was killed in an automobile accident on April 22, 1916. NPSHPC - SEQU/08838 |

There are two photographs of rangers in this uniform. The first one is of Charlie Blossom, a ranger at Sequoia. This is a portrait, but it can be seen that there are no top pockets on the coat. It has the rise-and-fall military collar of the type used on the 1910 U.S. Army uniform coat. It also has the same U.S. military insignia on the collar as that worn by Karl Keller in his 1910 photograph. It appears to be of a winter weight, but we cannot tell if it has bottom pockets.

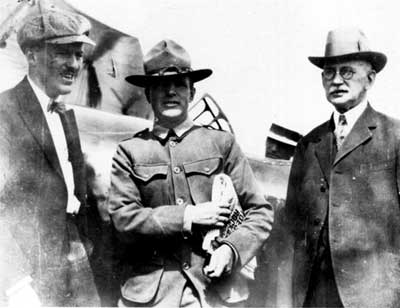

The second image is of a cavalry captain between two rangers, reputed to have been taken in Sequoia in 1911. The ranger on the left is wearing what appears to be one of these coats. The other ranger has on a Norfolk jacket. He may be a temporary employee, since the jacket appears to be of lightweight fabric rather than the wool used by Parker, Bridget & Company.

U.S. Cavalry captain between two park rangers, Grant Grove, Sequoia National Park, c. 1912. Ranger on left is wearing the 1912 "Eisner" coat, while the one on the right has on a civilian style Norfolk jacket. NPSHPC - HFC/73-672 |

Everything was not uniform. There were many small variations, such as breeches with and without belt loops, side versus back buckles, and experimental breeches made from 22-ounce overcoat material and waterproofed for winter wear at Glacier. Then there was the coat for Ranger Cyrus C. Bellah at Glacier. He ordered and received a coat with three outside pockets, the usual two bottom ones and one on the top left. [48]

The first major complaint that appears in the records, other than about size or minor design corrections, was about a pair of trousers ordered by Chief Ranger Haney E. Vaught at Glacier on April 12, 1913. The material seemed to "collect in small round balls or knots and these wear off leaving the cloth very thin." Eisner replied that this was the first complaint he had received about the uniforms and noted that the material was the same as that used in the U.S. Army uniforms. He suggested that a better material be used because the ranger uniforms were worn "more in the woods and for regular wear." [49] One has to wonder what the Army used their uniforms for!

In response to numerous requests for the uniform regulations and material samples from other contractors, the department's standard reply was, "This Department has no specifications or samples of the cloth for distribution." Petitioners were advised to contact Sigmund Eisner. [50]

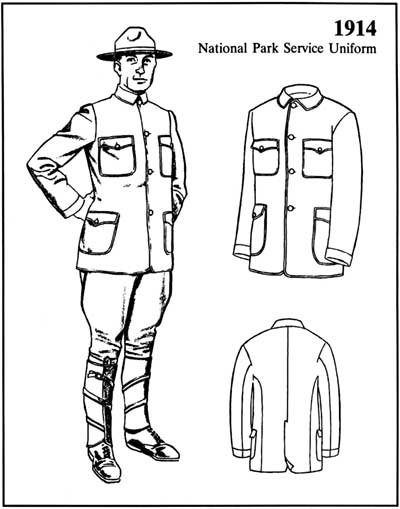

On March 17, 1914, Superintendent James L. Galen of Glacier ordered a uniform for Chief Ranger Haney Vaught having a coat with four outside pockets (two top and two bottom) and a military collar. They requested "the letters G.N.P. about 1/2" high sewed on all uniform coat collars, using jet black felt" and "one single braid, of material similar to the uniform, sewed around the cuff of the coat sleeve on all uniforms." Eisner replied that this was practical, "excepting that the U.S. Army uses O.D. Braid on the sleeves of their coats for the officers, and black braid for officers of the general staff and we do not know whether it would be an infringement on the Army style or not." The department denied Glacier the G.N.P. on the collars, although the four outside pockets were agreed to and ordered.

Joe Cosley, c. 1911. Cosley was a ranger at Glacier National Park, 1910-1914, and was one of the first recipients of the new 1911 uniforms. Photograph was taken prior to the arrival of the uniform. He is wearing 1910 US Army coat. Note GNP on collar and flower (his trademark) painted under brim of hat. NPSHPC - GLAC/HPF#1987 |

Glacier also wanted shirts made out of a material the department termed white duck instead of the olive drab flannel, but Adolph C. Miller, Stephen T. Mather's predecessor as assistant to the secretary, deemed this too drastic a change from the color and material then in use. "The Department desires that the olive drab material originally selected by it be used in the uniforms of employees in the national parks, and will not approve of any departure in the use of other material," he wrote Galen. [51]

The request for collar ornamentation is illustrated by an earlier portrait of Joseph Cosley, a ranger at Glacier, showing him in what appears to be the regulation Model 1910 U.S. Army issue coat. Stitched on the collar is a patch with the letters GNP applied to it. The letters appear to be about one inch high and of a darker shade than the coat, but not black. The coat has shoulder tabs and top outside pockets. Cosley also has on a hat with a stiff brim and a rose painted on the under side. There is another photograph of Cosley sitting in a chair wearing this same uniform. In this image he has a mustache. Both photographs were probably taken before June 1911 be cause he was one of the original recipients of the new uniform.

Cosley worked as a ranger at Glacier National Park from 1910 to 1914. He probably got to know the park and ranger routine rather well, so well, in fact, that he returned fifteen years later and set up his own fur business. On May 4, 1929, Ranger Joe Heimes while on patrol one day discovered Joe's illegal camp and staked it out. Ten hours later, as it was getting dark, Cosley returned and settled in among his furs and traps. As he started to build a fire Heimes moved in. Heimes said later that when he approached the camp, "this poacher looked a lot like Joe Cosley." After a sleepless night and several scuffles, Heimes "managed to bump Cosley's head against a tree and sort of knocked him coo-coo." Cosley finally gave up when two more rangers showed up. [52]

William Gladstone Steel, 1915, superintendent Crater Lake National Park, 1913-1916. Sunday Oregonian Newspaper, 18 Dec., 1915 |

Superintendent Galen started investigating complaints by the rangers at Glacier about the quality of the clothes they were getting from Sigmund Eisner. He found such things as shirts shrinking. One example was a shirt that required a two-inch string to connect the collar; the tail had shrunk to about half its original length. On another shirt, the collar opened very noticeably to one side because of a cutting error. Apparently Eisner had also sent out two different material samples with the same number. While they were of the same shade, one was of a much inferior grade. Galen had priced the better goods and found that they would cost almost twice as much, $22.00 versus $13.00. Even so, he said, the "rangers do not object to paying a larger price provided they can get a durable uniform." [53]

Assistant Secretary Lewis C. Laylin wrote Eisner expressing Galen's views and including the order for Chief Ranger Vaught's uniform, but with only the two bottom outside pockets. This may have been an oversight, because that same day he ordered a uniform for Ranger Thomas E. O'Farrell of Mount Rainier with a coat with four outside pockets. [54] In fact, most of the coats subsequently ordered under the old #2 sketch had four outside pockets.

There always seems to be someone who does not get the word. Although he had been receiving the current uniform information, Superintendent William R. Arant of Crater Lake may not have passed it along to his successor, William Gladstone Steel. In September 1914 Steel wrote the secretary asking whether there was "such a thing as an approved uniform for the Park Rangers?" If so, he wanted to have all of the employees in uniform for the 1915 season. [55]

Mark Roy Daniels, 1915, general superintendent of parks, 1914-1915. Daniels designed a new uniform in 1915 that was used concurrently with the 1912 "Eisner" uniform. Portland Journal, 15 April, 1915 |

In 1914 Mark Roy Daniels, general superintendent of national parks from 1913 to 1915 (a position roughly equivalent to the later director), in collaboration with Colonel Brett at Yellowstone, designed and had made up a proposed new uniform. Photographs were taken of him wearing the uniform and forwarded to the secretary for approval. The secretary approved the new uniform and an inquiry was sent to Eisner, enclosing the photographs and material sample, requesting prices. The new material was a blend of thirty percent cotton and seventy percent wool, then under consideration by the War Department for Army uniforms. [56]

These photographs have not been found. There is no way of telling what this uniform looked like, but apparently it was close enough to the one being used for the department to authorize its use concurrently with the existing one from Eisner. It probably had four pockets on the coat, since that was the norm.

Unidentified ranger at Yellowstone National Park, c. 1916, wearing what may be the uniform designed by Mark Daniels in 1914. NPSHPC - YELL/13 |

There is an unidentified photograph in the Yellowstone collection that may possibly be of this uniform. It shows a man wearing a uniform similar to the 1917 style, but without pleats on the top pocket or N.P.S. stitched on the collar. Since these are prominent features of all coats made between that date and 1920, it is reasonable to assume it to be earlier. It is also not one of the late "Eisner's". Of course the man could be a temporary and wearing something that he had made up. But it's doubtful that he would have gone to that expense and not have a regulation uniform made.

While the new uniform was being considered, the department issued a regulation on January 9, 1915, entitling employees to wear a service stripe on their sleeve for each five years of service. [57] Although there were a number of rangers that would have qualified, there are no known photographs of anyone from this period wearing these stripes.

Uniforms of the old style were still being purchased for the upcoming season. With but few exceptions, all of these new orders had top outside pockets, further complicating their identification. [58]

On April 21, 1915, Eisner replied that it was not practical to secure the thirty percent cotton olive drab cloth that had been proposed for the new uniforms. Instead he suggested and enclosed a sample of another material. Using this material, a coat and breeches or trousers would cost $24.00, in either the current or new style. Also, "in case buckskin reinforcements in uniform photographs" were ordered, there would be an extra charge of $2.00.

|

Cover from a booklet of drawings illustrating the "Daniels" uniform. These drawings were provided by Sigmund Eisner in 1916 at the request of the Director's office. National Archives/RG 79 |

A complete new uniform of coat, breeches or trousers, hat (probably Alpine style), shirt, and leather puttees would now cost $33.75. Eisner further stated that "sketches and booklets" were being made and twelve copies would be sent to the department when completed. There is no documentation as to when these sketches were sent, but a letter from Eisner on February 8, 1916, complaining about the lack of uniform orders "as per the enclosed circular, which we got out for you" is accompanied by what appears to be the label from a booklet. [59] It is 3" by 6-1/2" and printed on a medium blue paper. A note accompanies it stating: "Mr. Albright took booklet with picture of uniforms. When returned it should be posted here." No copy of this booklet has been found.

In the meantime, probably wearying of the long delay in settling the manufacture of the new uniform, Daniels contacted a supplier (probably the B. Pasquale Company) in the San Francisco area, since he was stationed there, to make them for the rangers. He requested buttons for six uniforms, two dozen each of large and small. In May 1915 Daniels proposed that the buttons be changed from the "dark" button, then used, to one of a bright finish. He enclosed a button with the finish he had in mind. It is unknown whether this "bright metal" button was plated or just polished brass. This posed a problem for the manufacturer, also, since he had to request that a sample button be sent. [60] There is no hard evidence that these buttons were ever adopted, although there is a polished brass button, of unknown provenance, in the National Park Service collection.

The Daniels uniform (for want of a better term), while authorized, was not adopted as the "official" park ranger uniform. It would seem that it was being manufactured on the West coast and the Eisner uniform was still being made in the East, with the rangers having the option to purchase either one. An interesting note on this is a letter of November 17, 1915, from Richard R. Young, assistant to Daniels, requesting buttons be sent to him to be "utilized in the making of uniforms for the Park Rangers in Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks." Four months later Supervisor Fry at Sequoia was requesting uniforms from Eisner. [61] The "1912" style, originally designed by Eisner, was ordered up until at least the summer of 1917, with pocket variations. All the orders to Eisner refer to coats, "as per sketch #2," with or without top pockets. This was the designation used for the "1912" Eisner coat. (This could have applied to a sketch in the Daniels uniform booklet, but nothing in the correspondence suggests this.)

Stephen Tyng Mather, c. 1915. First director of the National Park Service, 1916-1929 NPSHPC - William E. Dassonville photo - HFC/92-36 |

On August 25, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed legislation creating the National Park Service as an Interior Department bureau. Stephen T. Mather became its director upon its organization the following year.

Until this time the superintendents of the various parks, with a few exceptions, had been allowed to set their own ranger uniform standards. Normally, as long as they followed a vague set of guidelines, rangers were allowed to wear whatever uniform they wished. Most seemed to be wearing either the Daniels or the Eisner coats. But in Yellowstone, for instance, rangers did not wear uniforms. [62] They more than likely wore a combination of civilian and military clothing.

Yosemite rangers had been wearing military clothing, but on July 1, 1916, under Section 125 of the National Defense Act, it became illegal for anyone other than military personnel to wear the uniform of the U.S. Army. This required them to order their uniforms through the normal departmental channels. That October Supervisor Washington B. "Dusty" Lewis wrote, "Practically nothing in the way of Army uniform clothing has been purchased recently by the ranger force of this park, a uniform of a color similar to that of the forestry green having been adopted." [63] Because of the proximity of the park to San Francisco, one would think that they were using the Daniels uniform and that it would have been olive drab. It is not known whether the rangers had begun purchasing their uniforms from the Hastings Clothing Company at this time, but more than likely the new forest green clothing came from that establishment. As with so many of the uniforms being used by the parks, nothing is known as to style.

Washington B. "Dusty" Lewis, 1921. Superintendent, Yosemite National Park, 1917-1928, with wife Bernice and son Carl. Lewis was one of the people instrumental in standardizing the uniform of the National Park Service. NPSHPC - HFC/92-21 |

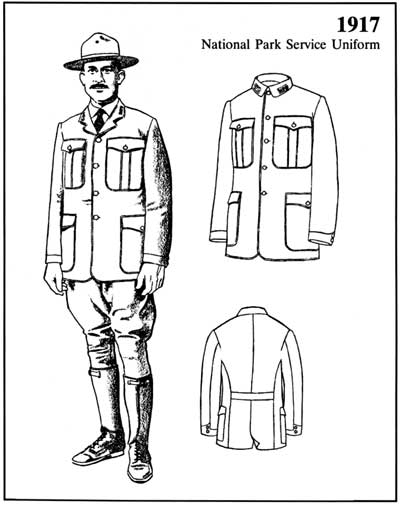

The supervisors and rangers from the various parks were becoming eager for a regulation uniform to be adopted. While in Washington at a national parks conference in early 1917, they made sketches for a proposed new regulation uniform for the Service. Supervisors Lewis (Yosemite) and Dewitt L. Raeburn (Mount Rainier) then held an informal discussion with the quartermaster general's office concerning the possibility of having the Army make up uniforms for the National Park Service. There seemed to be no problem with this, provided the transactions were handled officially between the departments. Lewis later forwarded material samples and sketches of a coat design that "conflicts in no way with army uniforms," requesting the Service to make the necessary arrangements. He figured the rangers could save "50% or more" on the cost of their uniforms. [64]

Acting Superintendent of Parks Joseph J. Cotter pursued the matter with the quartermaster general. He stated that the Service's needs would be small: "we will not have over seventy-five employees in the field at anytime in the near future." But the quartermaster general declined to become involved, noting that "under present conditions this Department is taxed to its utmost capacity in meeting the requirements of the Army." He did furnish the names of the uniform companies supplying the Army. [65]

L. Claude Way, Stanley Field, Rocky Mountain National Park, 1916. Way was superintendent at park, 1917-1921. He is wearing a U.S. Army uniform with civilian buttons. Left to Right: Alfred Dearborn; Way; acting superintendent Charles R. Trowbridge. NPSHPC - ROMO/1610 |

With the Army declining to assist in uniform procurement, the National Park Service fell back on the old method of supply, with the parks purchasing uniforms from Sigmund Eisner through the department or on their own from local suppliers. In a May letter to Chief Ranger L. Claude Way, Rocky Mountain National Park, Acting Director Horace M. Albright reviewed the department's uniform purchasing history and stated: "Blue print No. 2 shows the style of coat which the contractor has been furnishing, except that no top outside pockets are included. The other drawing is one that was gotten up by several of the supervisors when in Washington." The former drawing is the one made by Eisner in 1912. The latter was located in correspondence relating to the changing the uniform design in 1928. [66] This copy of the 1917 uniform drawing was altered probably in 1920 when the N.P.S. was eliminated from the collar.

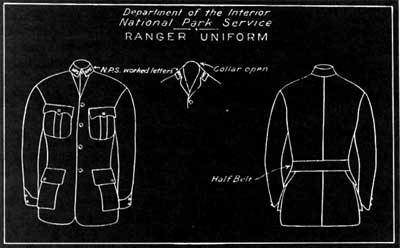

Drawing of 1917 National Park Service uniform illustrating worked N.P.S. on collar. NA/RG 79 |

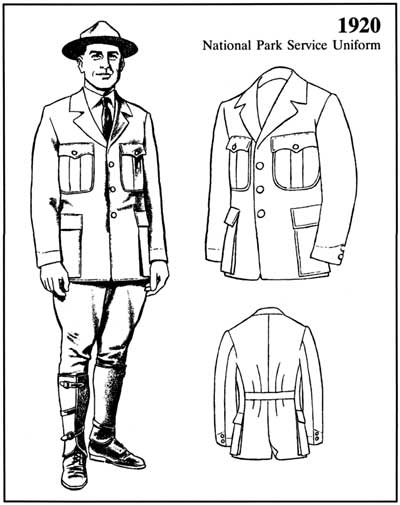

In a letter to Eisner dated May 7, 1917, Albright wrote: "You have heretofore furnished uniforms to rangers in the National Park Service [and] with the exception of minor pocket modifications, modeled the coats in conformity with a drawing submitted at one time, designated 'Fig. 2.' The enclosed drawing represents a style of coat which is considered more distinctive and better adapted to the needs of the National Park Service than the one now being used." This "new design" coat had a convertible collar, four outside patch pockets with the top pockets having pleats, and a half belt in back. This style of coat was adopted by the 1920 regulations. The existing blueprint shows that the department simply crossed out the stitched N.P.S. requirement on the print before sending it out to the suppliers. The material was still to be olive drab wool. [67]

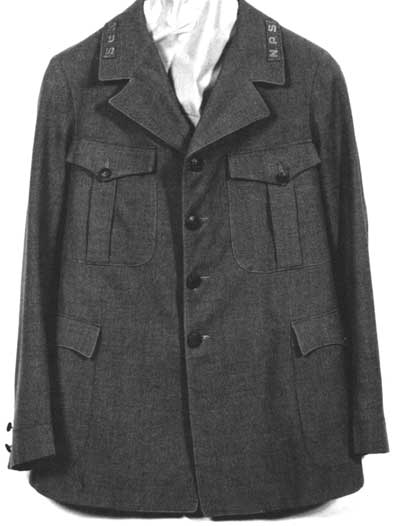

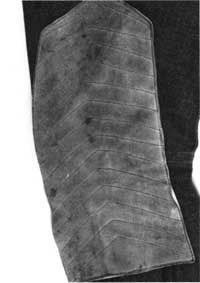

There are a coat and breeches in the Yellowstone collection that match the above description, except that they are forestry green wool. These were almost certainly made in 1919, because that was the only year that the official ranger uniform was forest green with N.P.S. stitched on the collar.

|

Eisner priced this new uniform, consisting of coat, breeches, shirt, leather puttees, and "alpine" hat, at $28.75. There were options, such as trousers instead of breeches, buttons on the breeches instead of laces, etc., that would raise or lower the basic cost somewhat. [68]

At this same time parks were apparently ordering uniforms from other suppliers, because requests were coming in for more NPS buttons than would have been lost through attrition. [69] These buttons were being furnished by Eisner but manufactured by the Waterbury Button Company in Waterbury, Connecticut, with Eisner's back stamp.

Alex Sparrow, superintendent at Crater Lake National Park, 1917-1923. Photograph was taken prior to receiving his new uniform in 1918. Courtesy of Oregon Historical Society #87191 |

In January 1918 Superintendent Alex Sparrow of Crater Lake ordered a new uniform through the director's office. "Please remind them that the Coat is to be the New and improved style adopted by the Park Service," he wrote. This was apparently the design developed during the national park conference in Washington a year earlier. An item not included on previous uniforms was the addition of N.P.S. in half-inch letters "worked on the collar with thread the same color as the buttons." [70] This was worked on the convertible collar so that it showed when the collar was worn in either mode. This is evidenced by the blueprint, photographs, and the existing 1919 coat in the Yellowstone collection. The letters were on the collar near and parallel to the outside edge.

The Bancroft Library photograph collection contains two photographs showing rangers at Yosemite wearing coats of this period. One of the photographs, undated but probably taken in 1917 or 1918, shows nine rangers wearing an assortment of coats portraying the latitude accorded the rangers at the time. The ranger on the left has a coat with pockets like the 1907 Forest Service pattern. Ranger Gaylar in the center has his collar buttoned up, military fashion, with what must be the letters N.P.S. stitched on the collar, as described above, or possibly a set of the N.P.S. insignia purchased by Supervisor Lewis in 1916. The remaining rangers all appear to be wearing the same style coat, although there are variations in the cut. This is odd because it is supposed that during this time all of Yosemite's ranger uniforms were being made by the same company. [71] It is possible, of course, that the differences represent options. They all have the pleated top pockets, but there are differences in the cut of the coat skirts, pockets, etc.

Another interesting feature is the badge worn by all but one. It is a very small badge, about the size of that later worn by park superintendents, while that on the third ranger from the left appears to be a large two-inch badge like those previously worn. It is not known at this time what the small badge looked like. The rangers in Yellowstone and Yosemite were issued this badge, but it is not known if any of the other parks received it.

Nine rangers, Yosemite National Park, c. 1917. This image shows the variety of cuts to uniform coats within the park even though all of the uniforms were supposed to be coming from the same manufacturer. Left to Right: (?); Forrest Townsley, chief ranger; (?); Billy Nelson; A. Jack Gaylar; Ansel Hall, chief naturalist; (?); Charles Adair; (?) Courtesy of the Bancroft Library/University of California |

It is difficult to tell from the photograph, but there appears to be something on the collars of the rangers, probably the above-mentioned stitched N.P.S.

While all the rangers are wearing basically the same hat, each has his own blocking method. The hatbands appear to be of a lighter shade. Probably the grosgrain ribbon that came with the hat.

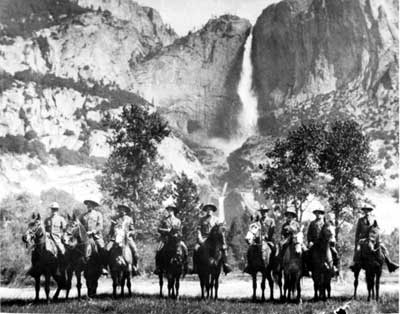

Another photograph from Yosemite shows Superintendent Lewis with eight of his rangers mounted on horses in 1918. Lewis is wearing a military cut coat, again with something applied to his collar. In this case, though, it is almost certainly a set of his N.P.S. insignia. Ranger Gaylar, third from left, has his collar open on his coat. This would probably date the previous photograph as being later, but not necessarily. The only badge in evidence is the one worn by Chief Ranger Forest Townsley, second from left.

Nine mounted rangers at Yosemite National Park, c. 1918. Claire Hodges (3rd from right) is the first woman to be hired to work as a ranger in a national park. Left to Right: Washington B. Lewis, superintendent; Forrest Townsley, chief ranger; Jack Gaylar; Lloyd; (?); Charlie Adair; Claire Marie Hodges, temporary ranger; Skelton; McNabb. NPSHPC - HFC/92-6 |

What really makes this image interesting is the appearance of Temporary Ranger Claire Marie Hodges, third from right. She was the first woman ranger and one of two women who filled ranger positions left vacant in 1918 by men going into the Army. Helene Wilson at Mount Rainier National Park was the other. While Miss Wilson basically worked at the main gate checking in traffic, Miss Hodges did actual ranger patrol. [72] Most early women in the parks were either guides or ranger-naturalists. From the photographs and lack of data to the contrary, it would appear that there were no uniform guidelines for female employees of the Service.

Horace Marden Albright, superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, 1919-1929. For all his passion for Servicewide uniformity, Albright is shown wearing an A-typical uniform coat in this 1919 image. All four pockets are pleated and the coat utilizes plain civilian buttons. Courtesy of Montana Historical Society - J.E. Haynes Photo - H19006 |

Up to this time the only deviation officially allowed the rangers was to have the coat cut either military or standard, although trousers instead of breeches were permitted in some cases. When Superintendent Walter W. Payne of Glacier requested "ordinary sack coat and trousers" in April 1918, Assistant Director Albright replied, "clothing worn by rangers while on patrol duty, or where they will come in contact with tourists, [should] be the same in all parks and to that end a uniform of distinctive type has been designed (blueprint of which is herewith enclosed) for use by all rangers." When ordering new clothing, Albright wrote, rangers should be required "to have the coat made of the approved design with the ordinary long trousers or riding breeches." Although there was no objection to them using a more expensive material, he feared that "should they be called upon in an emergency to fight fire or do other work they will be reluctant to use their best efforts, where if they wore a durable cloth which cost less money their minds would be on their work and better results would be obtained." [73]

As many photographs from the parks testify, rangers were required to wear the uniform only when they would come in contact with the public. Apparently to save wear and tear on the expensive uniform, at other times they wore only their badges to denote who they were.

The military cut was not shown as an alternative on the uniform blueprint Albright sent Glacier in April 1918. The clerk in charge at Glacier wrote the director that "Rangers Beebe, Cooper and Thiri have already received clothes, the suits being of a military cut coat and riding breeches." He asked if it was "compulsory for them to order another uniform of the National Park design at this time." Director Mather replied that as long as the military cut did not overly resemble the Army uniform, it could be worn. If it did, alterations would have to be made. [74]

There were complaints during this period regarding the tardiness of uniform deliveries from Sigmund Eisner, which was one of the prime contractors for U.S. Army uniforms. "Undoubtedly you understand that we are pressed continually by Government demands, and our shops and facilities are crowded to the limit because of present War conditions," Eisner responded to an inquiry. [75] This no doubt resulted in many ranger uniforms being ordered from other suppliers, but no record of these purchases can be found in the official files because only the Eisner orders were placed through the director's office.

Word must have gotten out concerning the problem of delivery, because 1918 brought inquiries from numerous companies requesting "National Park Service specifications" and "fashion plates." Schoenbrun & Company stated that it had received orders from the rangers at the "National Glazier [sic] Park." Mather's reply included a blueprint of the authorized uniform. He stated that it was to be "made of the olive drab material similar to that used for the Army" and that the "letters N.P.S. are to be worked on the collar with thread the same color as the buttons (bronze)." He further stated that if the company cared to submit cloth samples and prices, it would be given "careful consideration" in the event of future orders from other parks. [76]

In February 1919 an interesting correspondence began concerning some surplus uniforms from the United States Shipping Board, Emergency Fleet Corporation. Two weeks before the armistice Maj. Norman MacLeod, head of the plant protection section, had received 1,134 uniforms for guards at shipbuilding plants. Now that they were no longer needed, they were offered to the National Park Service at $12. (They had originally cost $16.) MacLeod forwarded a sample uniform. Mather thought it might be good enough for temporary rangers, but Assistant Director Albright and Superintendent Lewis of Yosemite thought that the cut and color were wrong. It was decided to forego the offer, and the sample uniform was returned. [77]

In April 1919 Washington decided to change the color of the Park Service uniforms from olive drab to forest green with the trousers or breeches a shade lighter than the coat. [78] The procedure of obtaining material samples and prices was begun at once. It was during this period that the coat in the Yellowstone collection was made. Since the only change noted in the correspondence is the color, this is almost certainly the pattern of coat referred to in Albright's letter to Superintendent Payne at Glacier a year earlier. Also, the "shade lighter" provision for trousers and breeches must have been dropped since the Yellowstone coat and breeches are the same color and there is no evidence that it was ever adopted.

Chester A. Lindsley, acting superintendent, Yellowstone National Park, 1916-1919. Although Horace M. Albright was superintendent, his duties as "field assistant" to Mather required much of his time, thus day to day running of the park fell to Lindsley. NPSHPC - HFC/92-3 |

One problem that had plagued the Service from the beginning was that of uniforming the temporary seasonal employees. Because of their low pay and short service, most parks made uniforms optional for these people, although uniforms were encouraged. In May 1919 Superintendent Lewis, who seemed to be the guiding light with respect to uniforming the rangers, had a sample suit made up from a "moleskin" material by the Hasting Clothing Company. This firm had been making Yosemite's uniforms for the past three years. It was an inexpensive alternative to the regular uniform, costing $20 ($17.50 in quantity) versus $50. He forwarded it to the director for his opinion. The suit was then passed around the parks for comment, all of which was favorable. Acting Superintendent Chester A. Lindsley of Yellowstone did question why the N.P.S. was not sewn on the collar and asked if this could be waived. Albright replied that it could "be procured for very small extra charge. Cannot be waived." [79]

On September 5, 1919, Lewis sent the director a sample N.P.S. collar insignia. It was one of a number he had made at the Meyers Military Shop in Washington, D.C., three years before. He offered it for consideration in replacing the stitched-in N.P.S. The insignia consisted of a bar with the letters N.P.S. so it could be attached as a unit. It is not clear whether the letters were applied to the bar or whether the whole was a single piece of metal. Acting Director Arno B. Cammerer responded critically. "There are a number of serious defects in the design, which is a stock-cut proposition put out in the cheapest possible way for the largest gain," he wrote Lewis. He noted that the War Department had some of the best artists working on new lettered insignia for the military and thought that some of these designs had distinct possibilities for the Service. He figured that once a standard insignia design had been arrived at and a master die cut, "we can have as many specimens cut as we want in the future." [80]

At the annual superintendents' conference on November 18, 1919, at Denver, Colorado, proposed regulations were submitted for uniforming the National Park Service. A committee meeting was held at which the proposed regulations were gone over and reported on. These proposals were the basis for the official regulations promulgated in 1920. At the end of the conference, there were still some details to be cleared up concerning the uniforms. Lewis and Charles P. Punchard, Park Service landscape engineer, with apparently Assistant Director Cammerer advising, were as signed this task.

The original specification submitted at the conference called for "a five button sack coat." Punchard called Cammerer's attention to the fact that this should read "a four button sack coat inasmuch as the collar was voted upon to be non-convertible." [81]

1919 National Park Service ranger uniform. Forest green with N.P.S. on collar. NPSHC - YELL/Cat#1648 |

Half-belt in back. |

Cuff applied to sleeve. |

Pleated pocket (with scalloped flaps). |

Plain pocket (with scalloped flaps). |

Breeches contain two rear pockets, two side (front) pockets and a watch pocket in waistband. Waistand equipped for either belt or braces (suspenders). NPSCH - YELL/Cat#1649 |

Legs contain buckskin reinforcement on inside. This was an option. Otherwise, reinforcement was of same material as breeches. |

Rangers had the option of having either buttons or lacing at bottom of legs. |

Coat button. NPSHPC - HFC/92-5 |

N.P.S. on convertible collar, worked in bronze thread. |

Yellowstone Park Scout Badge, c. 1894-1906. Issued to civilian scouts hired by the military to help protect Yellowstone National Park. Scouts were issued nickel-silver, while those of the chief scouts were sterling silver. NPSHC |

Chauncey E. "Chance" Beebe, ranger at Glacier National Park, 1920. Chance is wearing one of the first uniforms of the new 1920 Model. The new insignia and badges had not been issued at the time of the photograph. NPSHPC - GLAC/HPF#2681 |

By February 1920 the regulations were ready for submission to the secretary for his approval. On March 20 Director Mather signed the first "official" regulations covering the rangers employed in the national parks servicewide. The park personnel covered by these regulations had to uniform themselves no later than July 1. Although not spelled out in the regulations, ranger badges of a new and approved design were being manufactured and the old badges were to be replaced sometime in May. [82]

The guardians of our national parks had at last come of age. No longer would they be just a collection of men in search of an identity, not knowing from year to year what their next uniform would look like, or even what color it would be. This must have been very gratifying to men like Walter Fry, Washington Lewis, and the others who had struggled through the early years to raise the Service to the level of the sacrifices being made by the men in it.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

nps-uniforms/2/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 01-Apr-2016