|

National Park Service

National Park Service Uniforms Ironing Out the Wrinkles, 1920-1932 |

|

IRONING OUT THE WRINKLES

With the creation of the National Park Service in August 1916 and the subsequent appointment of Stephen T. Mather as director, the desire of park rangers for a national identity mounted. Mather, aided by men like Horace Marden Albright and Washington Bartlett "Dusty" Lewis, set about making the Service a cohesive organization with regulations applicable to all the parks. Standard uniform regulations were a logical ingredient.

The 1920 National Park Service Uniform Regulations stipulated what the personnel of the Service were to wear, as well as what it was to be made of. An officer and ranger mentality pervaded the Service, no doubt a carry-over from the Army days in the parks, and this was carried through in the uniform regulations. Although all personnel were required to wear the same uniform, the officers' material was of a finer quality (12-14 oz forestry serge, versus 16-18 oz forestry cloth) than that provided for the rangers. This forestry green became the standard color for National Park Service uniforms and, except for minor color variations, remains so today.

Up until this time, only the hat, coat, shirt, breeches, and occasionally, the overcoat were stipulated. But with the new regulations all articles of the uniform, from hat to shoes, were covered.

Instead of "alpine", hats now were classified as "Stetson, either stiff or cardboard brim, "belly" color." This was a shortening of "Belgian Belly", named after the beautiful pastel reddish buff color of the underfur of the Belgian Hare from which many fine hats were made. [1]

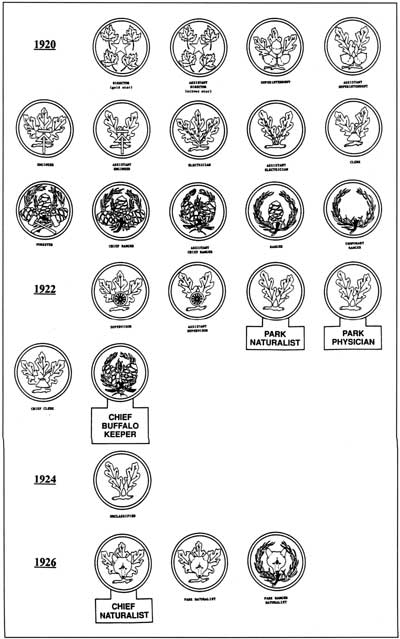

Collar ornament, 1920. This ornament, introduced in the 1920 Uniform Regulations, was made in three different metals. Gold (officers), silver (rangers), and bronze (temporary rangers). NPSHPC - HFC |

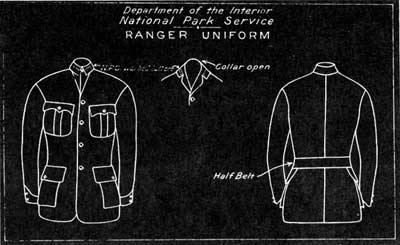

Although it had been decided at the meeting that the coat have an open collar, with four buttons, when the regulations were published they still contained the original wording "or English convertible collar" which required five buttons. This was not corrected in supplementary regulation changes until 1928, even though all coats were made with four buttons and an open collar. The embroidered N.P.S. on the collar was eliminated and replaced by a detachable pin insignia. This new insignia consisted of 1/4" letters with US centered over the top of NPS. The buttons remained the NPS style initiated in 1912 and still used today.

After much discussion, it was concluded that a medium grey shirt would be preferable to the olive-drab previously worn. And since the coat would now be worn open, a tie would be needed. Black and dark green were debated with the consensus of opinion being that a dark green four-in-hand tie would be the most appropriate for the forest green uniform.

Footwear had been left to the discretion of the individual ranger, who had worn boots, or shoes with either canvas or leather leggings or puttees (a form of legging, but firmer, similar to the top of a boot). Colors had ranged from the tan canvas leggings to black shoes and all shades of brown in-between. Now tan or cordovan (preferred) colored riding boots or leather puttees, with matching shoes, were to be worn, with leather puttees and shoes prescribed for dress occasions.

Officers and rangers were further differentiated by their overcoats, with the former having a five-button ulster type and the latter a four-button mackinaw.

In addition, there were a number of other rank and service designations included. The regulations also specified that rangers wear their uniform whenever they would be in contact with the public while on duty and were also encouraged to wear it under the same circumstances while off duty.

The new uniform regulations and sketches were distributed on April 1, 1920, with a request for the parks to forward their badge and insignia requirements to the director's office. The quantity required was needed before July in order to secure bids as soon as the 1921 funding became available. Responses were not slow in coming and included inquiries about the price and availability of the new uniforms. The regulations were not to take effect until June 1, but Service personnel were anxious to begin suiting up for the season. Superintendent Washington B. Lewis of Yosemite National Park immediately set about having "a complete set of official sleeve insignia made up in San Francisco," which he received in mid-May. [2]

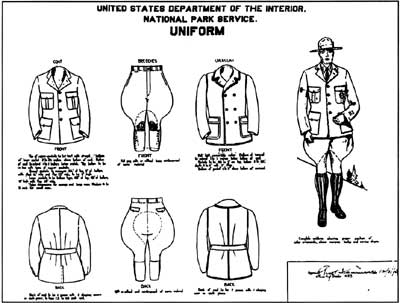

Uniform drawing, 1920. The drawing that was sent to the uniform manufacturers was actually the 1917 pattern drawing, altered to conform to the new Regulations. The only change was to draw a line through the embroidered N.P.S. on the collar. This created problems later for some of the manufacturers since the regulations specified a "pinch-back" coat and the drawing did not illustrate this feature. National Archives RG 79-208.30 |

On April 20, Assistant Director Arno Bertholt Cammerer asked suppliers about their ability to provide uniforms and accessories and requested prices and material samples. The Smith-Gray Corporation of New York City, which supplied the Forest Service with uniforms, returned a price of $62.75 for coat, breeches, and leather puttees. Sigmund Eisner of Red Bank, New Jersey, who had been furnishing some of the park rangers with uniforms, gave a price of $44.50 for the same items. The two companies priced the buckskin reinforcements for the breeches' legs an additional $8 and $5 respectively. Eisner commented that there was "very little variation from the present regulation pattern." [3] The new regulations specified a "convertible collar" and the other coat details present on the previous blueprint, codifying the uniform the rangers had recently been purchasing. In fact, the same blueprints used for the existing coats were sent out to the suppliers with a line drawn through the details denoting the stitched-in N.P.S. on the collars.

The collar devices were apparently put out for bids at the same time, for on April 27 Cammerer received a telegram from the R. F. Bartle Company of New York quoting $450 for "gold plate german silver bronze in four hundred lots sixteen gauge." The Army Supply Company of Washington D.C., won the order with a bid of $105 for four hundred pieces. [4]

William Harrison Peters, c. 1920. Peters was acting superintendent at Grand Canyon, 1919-1922. He had worked four years on road construction prior to moving to Grand Canyon. National Archives RG 79-SM-46 |

The regulations left some matters in doubt. Before coming to Grand Canyon National Park, Acting Superintendent William H. Peters had worked four years on road construction at Crater Lake National Park. Did this authorize him to wear the four field service stripes? It did. Civil Engineer George E. Goodwin argued that if he always wore his uniform on official duty, as the regulations appeared to require, it would "be ruined in a day." Director Mather was sympathetic:

"It can hardly be expected that the engineer wear the uniform when on road and trail reconnaissance because of the rough character of the country to be traversed and the fact that such work will not bring them into official contact with the public. . . . Whatever clothes may be considered suitable may be worn by the engineers, but I do believe the sleeve insignia and service hat should be used for identification purposes. In all other instances while in the parks the uniform must be worn." [5]

Superintendent William P. Parks thought that Hot Springs Reservation should be excluded from the regulations. He felt that the metropolitan police uniform already adopted for its police force and train inspectors was "much better suited for the purpose and more effective in appearance." He was going to require all the attendants in the free bathhouse to wear white duck suits while on duty. Acting Director F.W. Griffith replied that for the present, Hot Springs Reservation was exempted from the regulations.

While the director's office was attempting to locate uniform suppliers in the East, Goodwin and Lewis were pursuing the same goal in the West. The Hastings Clothing Company, the establishment currently making uniforms for Yosemite, was the only firm Lewis could find in the San Francisco area interested in bidding on the outfits. Its price was $60. Yosemite's rangers were willing to pay the higher price because they felt that the Hastings uniforms were far superior in quality to those from Sigmund Eisner. The rangers at Yellowstone may have felt the same way because they purchased their uniforms from the same company.

Nine mounted rangers in Yosemite Valley, 1920. Yosemite National Park. Left to right: Forrest S. Townsley, Ansel F. Hall, William H. "Billy" Nelson, Henry A. Skelton, Andrew J. "Jack" Gaylar, John H. Wegner, Charles E. Adair, Charles B. Rich, James V. Lloyd John W. Henneberger Collection (HFC/92-0006) |

Goodwin located two companies in the Denver area willing to supply the uniforms. The Railway Uniform Manufacturing Company bid $53.30 and the May Company $37.50. Collating all the bids, Goodwin found that the lowest, $27.40, was from the Utica Uniform Company of Utica, New York. This was for a limited time based on a special option on available material. Because the Service did not respond for twenty days and then asked for a ten-day extension, Utica canceled its bid and stated that it would have to go back to the market for new material prices before requoting. This left the Service with five uniform suppliers whose prices ranged from $37.50 (May Company) to $62.75 (Smith-Gray Corporation). The rangers were free to purchase from any of them. [6]

Group of temporary rangers, c. 1920, Yellowstone National Park. Group includes Horace M. Albright (center, in A-typical coat), Jim McBride on his right, with Roy Frazier behind them. The two motorcycle riders are Emmitt and Hollis Matthew. John W. Henneberger Collection (HFC/93-363) |

A lack of funds in the 1920 budget forced Lewis to wait until the 1921 appropriation became available before he could order the new brassards (sleeve patches). He solicited prices from a number of companies but found that the only one willing to bid was the B. Pasqual Company of San Francisco, which had made the original samples. Its price was $616 for the required 477 assorted patches. Acting Director Cammerer instructed Lewis to accept the bid. [7]

On a related subject, Lewis thought that chief and assistant electricians should be classed as officers. When this was brought to the director's attention, paragraph 2 of the 1920 regulations was amended to include them on July 1, 1920.

E. Burket, temporary ranger, Yellowstone National Park, c. 1922. Rangers dressed like Burket were not permitted in Yellowstone after the middle of 1922. That year, Albright made owning a uniform a "condition of employment". NPSHPC - YELL/130,011 |

Although not specifically covered in the 1920 regulations, badges were nevertheless an integral part of them. Their exclusion was probably an oversight, because drawings had been made and a contract let to have them made. The badges, along with the new collar ornaments, were received in early June and distribution commenced immediately. The badge consisted of a 1-1/4" coined medallion bearing an eagle and the words NATIONAL PARK SERVICE/DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR around the outside, applied to a shield with U.S. PARK RANGER on top. The whole was nickel-plated. The parks were informed that the new badges were to be carried on their property lists and that the old badges were to be returned.

Because of the limited supply of the new badges, some parks were instructed to retain some of the old badges for their temporary rangers. A 1922 photograph in the Yellowstone collection shows Temporary Ranger E. Burket wearing what appears to be a surplus Army uniform and one of Yellowstone's old badges, in this case one of the small unidentified styles that came into being around 1917. Until this time temporary (seasonal) rangers were not required to wear the official uniform because of their low pay and frequently short service.

1920 Pattern National Park Service ranger badge NPS Archives RG Y55-HFC/94-1 |

During this period Lewis, Goodwin, and Superintendent Horace M. Albright of Yellowstone apparently became an ad hoc uniform committee, with Lewis as head. All questions concerning matters of the uniform were referred to him. While acting superintendent at Glacier in the summer of 1920, Goodwin requested a clarification of the regulations in regard to clerks and rangers wearing trousers instead of the stipulated breeches. Acting Director Cammerer forwarded the inquiry to Lewis with the note: "It may be considered desirable after this first season to permit clerks in the offices to wear long trousers instead of riding breeches." A week later Cammerer wrote Goodwin: "These regulations do not permit the use of long trousers as a part of the uniform, but prescribe riding breeches instead." Anyone having long trousers could wear them out, he added, but no new ones were to be ordered. In January 1921 the uniform committee suggested that the regulations be changed to allow all but rangers to wear trousers, if desired. The trousers were not to have cuffs. [8]

Sleeve identification brassards (patches) used by National Park Service personnel. |

By November 1920 Lewis had received the sleeve brassards and length-of-service insignia ordered from the B. Pasqual Company and had dispensed them to the parks according to their requests. Employees were responsible for applying them to their coats. [9]

On January 7, 1921, Superintendent Parks of Hot Springs Reservation wrote Mather that in view of pending legislation to designate his area a national park (enacted March 4), he wanted its policemen uniformed like the rest of the Service. Parks had already contacted the Railway Uniform Manufacturing Company about having new uniforms made up for the coming season and asked the director's office to send the necessary buttons, badges, and collar insignia. The requested items were forwarded.

John Emmert, Chief Electrician, Yosemite National Park, 1922. Emmert's Chief Electrician brassard can be seen on his sleeve, although the lightning flashes are hard to detect. NPSHPC - Jimmy Lloyd photo - HFC/87-35 |

The uniform committee felt that the new badges reading "Park Ranger" were not appropriate for the officers and recommended that the old-style badge (1906) should be retained for their use. The committee also recommended that the badges of chief and assistant chief rangers should be gold-plated to differentiate between them and other rangers. On January 26, 1921, the uniform regulations were revised effective March 1. A new section 6 was inserted designating the badges to be worn by Service personnel. Instead of a single nickel-plated badge for all, it stipulated a round gold-plated badge for the director and assistant director, a round nickel-plated badge for all other officers, a shield-shaped gold-plated badge for chief and assistant chief rangers, and a shield-shaped nickel-plated badge for other park rangers.

In a March 4 telegram Acting Director Cammerer took exception to having all the field officers wear the same badge: "I think this serious mistake and that regulations should be revised to clear matter. Superintendents badge is emblem of authority and neither clerks, engineers or others should be found in any park with similar badge." While these discussions were going on, a request came into the office for badges "to be worn by the clerks and other subordinates on the force, based on our uniform regulations issued January 26, 1921." On April 13 Director Mather informed Lewis that badges for officers would be limited to superintendents, acting superintendents, and custodians (those in charge of national monuments). [10]

1921 Pattern National Park Service officer's badge. NPS Archives RG Y55 |

Hot Springs National Park seemed destined to remain in the forefront of the uniform controversy. On July 19 Senator Thaddeus H. Caraway of Arkansas wrote Director Mather:

"I am in receipt of a letter from a citizen of Hot Springs, Arkansas, protesting against the heavy winter uniform the park police are required to wear. My correspondent is in no way connected with the service, but writes me in the interest of "suffering humanity." Will you please see if something cannot be done to relieve these conditions?"

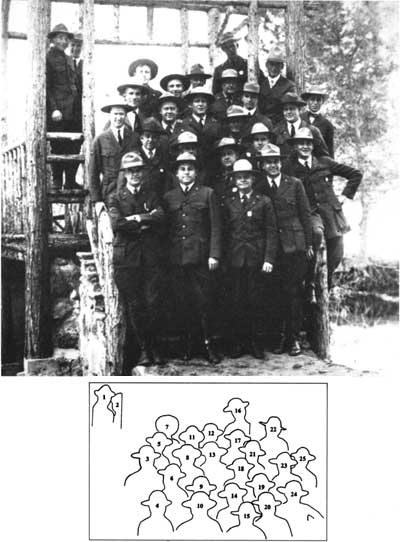

1992 Superintendent's Conference, Yosemite National Park. NPSHPC - Jimmy Lloyd photo - HFC/87-37 | |

|

1. Gabriel Sovulewski, Supr. YOSE 2. John W. Emmert, Ch Electrician YOSE 3. Horace M. Albright, Supt. YELL 4. Washington B. Lewis, Supt. YOSE 5. Jesse Nusbaum, Supt. MEVE 6. Tom Boles, Supt. HAVO 7. ? 8. Forest Townsley, Ch Rgr, YOSE 9. ? 10. Daniel R. Hull, Ch Architect, NPS 11. ? 12. ? 13. ? |

14. ? 15. William "Billy" Nelson, YOSE 16. ? 17. ? 18. Charlie Adair 19. ? 20. Ansel Hall, Ch Naturalist, NPS 21. ? 22. Frank "Boss" Pinkley, Cust, CAGR 23. Roger W. Toll, Supt. ROMO 24. John White, Supt. SEQU 25. Milo S. Decker, YOSE |

|

| |

Uniforms ordered in February were of the regulation heavy forestry cloth used for winter uniforms in other parks and had been worn at Hot Springs since April 1. The policemen had wanted summer-weight uniforms but had been informed that the lighter-weight cloth was for officers only. Superintendent Parks requested authorization to "allow the men to purchase shirts of the same color as the uniforms, and wear them, with the green ties, without coats." Acting Director Cammerer replied with his opinion that "the uniform to be worn at Hot Springs National Park will have to be reconsidered in order to adopt a material which will be suitable for that climate." He asked Parks to give this matter his attention and make recommendations accordingly. Meanwhile the policemen were to purchase forestry green shirts, as Parks had suggested.

Ranger personnel at Canyon, 1922, Canyon Ranger Station, Yellowstone National Park. Three of the rangers are wearing the white dress shirt, while the other two have on the gray. NPSHPC - YELL/130,000 |

Ranger Roy Frazier, c. 1920's, Frazier, a ranger at Yellowstone National Park is showing off his "biled" white shirt. NPSHPC - YELL/130,077 |

Parks forwarded his recommendations on January 31, 1922. He had delayed responding because the men had spent a considerable amount of money for their uniforms, which worked well for the winter. He was now "convinced that the regulation city police uniform, of blue serge with the coat-of-arms buttons, is best suited to this park, it being located in the heart of a city." Since the men had worn the present uniforms they had "constantly been confused with soldiers from the Army and Navy General Hospital, and in some instances persons have refused to permit our officers to render them assistance, thinking they were soldiers." Parks enclosed a booklet showing the regulation double breasted police coat with blue serge pants that he was suggesting.

Director Mather was not receptive to Parks' recommendation. He believed that all Park Service personnel should be uniformed in the same color. The forestry serge as worn by officers could be obtained in lighter weights for warm-weather wear, and trousers in place of breeches and puttees would also afford the policemen greater comfort. He further stated that "simple white shirts and collars can be worn, as provided in the general regulations, and, in fact, I think the general regulations can well stand with these modifications." [11]

On March 2 the new superintendent at Hot Springs, Dr. Clarence H. Waring, formulated Mather's suggestions into a recommendation for uniforming the policemen at the park. In addition, he requested authority for the use of gray wool shirts, without blouse, during the hot summer months. The shirt would be worn with the green tie and appropriate "insignia, grade marks, etc." on its collar and sleeves. (There are no known photographs showing a ranger wearing a shirt with a patch on the sleeve.) That summer another warm-weather area, Hawaii National Park, received authorization from Washington to use dark green gabardine instead of forestry green wool in its uniforms. [12]

Ranger (Emmit) Matthew on motorcycle near tower, 1923. Motorcycles had come into use in Yellowstone National Park in the late teens. Due to the nature of the work, motorcycle riders did not use the standard uniform in the performance of their duties, and with specialized clothing a thing of the future, any warm civilian coat was utilized, especially since they would not be in contact with the public. NPSHPC - YELL/130,387 |

Despite all their efforts to uniform the service, the uniforming of temporary park rangers continued to be a thorn in the side of superintendents. Horace Albright wrote Lewis in February 1922 suggesting a possible solution. He had located a Mr. Spiro who would furnish trousers, 2 gray flannel shirts, a stiff broad-brimmed cowboy hat, best-grade cordovan-colored puttees, and a green neck tie for $24.50. Albright's letter reveals his sentiment regarding the uniforming of the Service:

Director Mather riding in side car, Yellowstone National Park, (1923). Motorcycles had been used by rangers in patrolling parks, especially Yellowstone, since the late teens. Even Director Mather wasn't adverse to trying out this mode of transportation. NPSHPC - YELL/130,803

"This outfit will be just as pretty as the permanent rangers outfit. With a little encouragement we can get Mr. Spiro to make coats for our men at reasonable prices. Personally, I am going to make every one of my forty temporary rangers buy one of these outfits from trousers to neck tie. I am making the purchase of this outfit a condition of employment.

I presume you saw in the paper a short time ago that the United States Forest Service has decided to make every one of its employees wear uniforms of forest green. You know with what thoroughness the Forest Service carried out its organization plans. I feel that we in the Park Service cannot well afford to let the Forest Service do anything more in the way of uniforming its people than we do, especially in view of the fact that we started to uniform our employees some years ago. Up to the present, in my opinion, we have not been successful. You have most of your permanent men uniformed, but I think you told me that you are dissatisfied with the temporary employees' uniforms. If your temporary men are not satisfactorily uniformed, in my opinion, the indication of organization is very incomplete regardless of how well the permanent men look. Personally, I have been very unhappy about the looks of my temporary rangers, and I have made up my mind that if I cannot satisfactorily uniform the temporary men, then I am not going to pay much more attention to the permanent men.

I think the time has come when the Park Service must be consistent in the matter of uniforms. This means, in my opinion, that we have got to force our temporary employees to buy satisfactory uniforms whether they like it or not." [13]

In anticipation of ordering more badges and collar and sleeve insignia, the director's office requested the original drawings and specifications from Yosemite. These were forwarded, along with Landscape Engineer Daniel R. Hull's entire file on uniforms, and retained at headquarters. The original drawings were not found among the official correspondence, but copies were found enclosed with 1922 and 1924 contracts between the Park Service and E.J. Heiberger & Son, Inc., of Washington, D.C., the successful bidder for furnishing the new order of badges and sleeve and collar insignia.

Superintendent Albright and baby elk. This baby elk was raised by rangers at Mammoth Hot Springs and kept there to be seen by visitors, 1923. Albright was superintendent at Yellowstone National Park, 1919-1929. NPSHPC - Frantz photo - YELL/F-992 |

The April 5, 1922, contract added a sleeve patch for chief clerks; it was like that for clerks but with three oak leaves instead of two. It provided for "Game Warden" to be added in white beneath the circle on any insignia. Because the nickel plating on the original order of new-style badges had tarnished, it also specified that badges would be made of German silver. In a follow-up letter, Chief Clerk B.L. Vipond amended the contract to include eight "Park Physician" and eight "Park Naturalist" sleeve insignia. These were to be the same as the assistant electrician insignia without the lightning bolts and with the respective designation under the circle. Also, four of the assistant chief ranger insignia were to have "Chief Buffalo Keeper" embroidered under the circle. [14]

Supervisors and assistant supervisors, while considered officers, had been omitted from the 1920 uniform regulations and were not included in the first order of sleeve brassards. This was corrected in 1921 and their patches were included in this contract. They had the usual three and two oak leafs with a wheel as an identifier in the center.

Rangers at Mammoth, 1922. These rangers have their pack animals all loaded and are starting out on patrol at Yellowstone National Park. NPSHPC - YELL/130,006 |

On June 13, 1922, the January 26, 1921, regulations were amended to specify that "Each officer and ranger upon entrance on duty will be furnished, free of charge, two complete sets of collar ornaments, sleeve insignia, and service stripes." At the same time the Service badge, previously issued without charge, would now require a $5.00 deposit. Only the actual cost of $.80 had been levied in the past to replace a lost badge. "Without questioning the honesty of any individual or group of employees we have best reasons to believe that a number of the badges are kept or given to friends by employees for souvenirs after paying the small amount to cover cost," Acting Director Cammerer wrote. "These badges are issued to indicate Federal authority and every precaution must be taken to prevent them from falling into the hands of unauthorized persons." The Service did not wish "to impose a hardship on any employee who actually loses a badge through no negligence on his part," and it was left to the discretion of the superintendent as to whether forfeiture of the deposit was required. [15]

|

|

|

Fountain Station YNP 1923. Left: John Delmar,

Right: John W. Delmar. Here is an example of the numerous two

generation families of rangers in national parks. The Delmars served at

Yellowstone. NPSHPC - YELL/1 and NPSHPC - YELL/2 | |

Frank Pinkley, c. 1925. National Archives RG 79-G-40P-1 |

Horace Albright and Washington Lewis were appointed a committee to work up recommendations for revising the Service's uniform regulations in 1923. They began by sending out a questionnaire to all the park superintendents. A summary of the answers can be found in Appendix B. Most of those who commented liked the present uniform, except for the pinch-back of the coat, but felt that it could be made of a lighter and better material. There was much comment about the collar insignia with suggestions and some sketches of possible changes. While a few thought that there should be more differentiation between the officers and the rangers, most agreed with Frank M. "Boss" Pinkley, custodian at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument:

"It seems to me that our organization is so small, and will always remain small, there is no reason for a lot of distinctive grades. The visitor in the Park only knows of three general grades: the Superintendent, the Ranger, and all others connected with the Service. Give the Superintendent shoulder straps and a round badge; the Ranger his shield badge, and all others plain uniforms. Twenty-four hours after your visitor lands in your park he knows how to pick out a Ranger if he wants one, or the Superintendent if he wants to lodge a complaint. If the exception arises and he needs to meet some other department head, let him ask the first person in uniform and he will get detailed directions. This is from the visitor's standpoint. From the Service standpoint too much distinction is not wanted. We are all engaged in serving the people who come to us. The ranger who is filling his job up to the brim is entitled to just as much respect as the Superintendent who is doing the same. If you say the Superintendent is carrying the greater responsibility, my reply is that he is getting paid more money for doing it and that settles that. The Officer might need a better grade of cloth when at work in his office than the Ranger will need when at work in the field, but I see no reason for not allowing the other members of the force to wear as good cloth as they care to buy when it comes to public functions."

North entrance checking station, 1923, Yellowstone National Park. This is the way the park kept track of who and how many tourists visited the park. NPSHPC - YELL/1743 |

Pinkley also thought, along with others, that the collar and sleeve insignia were not necessary. Of the latter he wrote:

"The force in a Park is so small that each employee knows the status of all others. The visitor doesn't care whether the Chief Ranger wears a pair of crossed cactuses with a shovel rampant, while the Ranger wears only one cactus and two shovels and the temporary ranger wears a pick couchant; what the visitor wants is a ranger, and he promptly picks him out by his shield-shaped badge and goes and pours his woes in his ears. The fact that it is the third assistant ranger he is talking to means nothing in his young life.

Washington Bartlett "Dusty" Lewis, 1926, superintendent, Yosemite National Park. Lewis was one of the prime movers in uniforming the National Park Service rangers. NPSHPC - YOSE/#RL-9429 |

One item Pinkley brought up that had not been touched on by others was the matter of uniforms for the women in the Service:

"I have never heard anything about uniforms for the women of the National Park Service. I meant to interject this into the discussion at Yosemite, but just at that moment someone waved a gray shirt in front of Col. White [John R. White, superintendent of Sequoia National Park], and when he stopped for breath twenty minutes later the Chairman changed the subject. Let me ask here why the women are not entitled to distinctive uniforms, and service stripes and so on."

After reviewing the responses to the questionnaires, Lewis and Albright checked on the availability of lighter materials for uniforms. Gabardine was inspected but discarded in favor of whipcord. The Sigmund Eisner Company was contacted and a deal was arranged to supply the Service with 125 to 150 uniforms.

Lewis submitted new regulations to Director Mather on February 9, 1923. They contained several changes from the 1921 regulations. All field personnel were now required to purchase and wear regulation National Park Service uniforms. Forestry green whipcord was now optional for officer and ranger uniforms. Superintendents and custodians were the only officers other than the director and assistant director authorized to wear badges (as Mather had previously decreed); theirs were to be of the round form, nickel plated. Coats of all uniformed personnel were to always be fully buttoned. The $5.00 badge deposit was incorporated in the regulations, which admonished employees: "Badges are not to be sold or otherwise disposed of. They are issued to show authority and should not be allowed to fall into the hands of unauthorized persons." The new regulations were approved and distributed to all superintendents and custodians.

There was some discontent among the superintendents about the lack of uniformity in the gray color of the shirt, as indicated by Pinkley's remark about Superintendent White. Some thought that the Service should arrange for a sole-source supplier to ensure color uniformity. When White inquired about this, he was informed that the Service could not contract for anything that it would not be paying for but that the employees might be able to make such an arrangement themselves. [16]

The contract of April 5,1922, with F. J. Heiberger to furnish badges and collar and sleeve insignia had not been filled a year later with respect to the sleeve insignia, creating a shortage of these items within the park system. Difficulties with a subcontractor delayed completion of the order until November 1923, when Heiberger sent the sleeve insignia for the director and assistant director.

Ranger Patrol along Riley Creek, 1924, Mount McKinley National Park. As this image indicates, rangers used many different methods to patrol the nations parks. NPSHPC - DENA/29-1 |

Ten Mounted Rangers in Yosemite National Park, About 1924. Left to Right: William Henry "Billy" Nelson; Herbert R. Sault; Walter R. Silva; John W. Bingaman; Charles B. Rich; Charles F. "Charlie" Adair; John H. Wegner; Henry A. Skelton; Clyde Boothe, Forest S. Townsley, Chief Ranger NPSHPC - HFC-YOSE/909 |

Assistant Director Cammerer in Mesa Verde, 1925. NPSHPC - YOSE/RL-7429 |

The uniform regulations required all officers to wear breeches with their uniform, but when Acting Director Cammerer ordered a forestry green whipcord uniform from Sigmund Eisner in September 1923 he specified long trousers. A privilege of rank, no doubt.

When Cammerer received the $38.25 bill for his uniform he thanked Eisner for the "special discount," even though Eisner's price list carried the same uniform for $37.00. He may have ordered a shirt, hat, or something else but it is not recorded. [17]

In early 1924, bid requests for more badges and insignia were sent to Henry V. Allen of New York and Heiberger. Heiberger alone responded and was awarded the contract despite having taken 19 months to fill the 1922 order. The instructional sheets of the contract contain full-size drawings of the sleeve insignia, including a new "unclas-sified" insignia consisting of two oak leaves on a branch within the circle. The insignia for the "Park Physician" and "Park Naturalist" with their awkward lettering beneath the circle had been so unpopular that employees in those positions elected to wear the unclassified insignia. Consequently these insignia were not included in the new contract. The unclassified sleeve insignia was to be worn by any uniformed employee not otherwise covered in the regulations. The new sleeve insignia were received by the Park Service at the end of June. [18]

In the summer of 1924, it was noticed that temporary employees were retaining and wearing their USNPS collar insignia after terminating their service. This came to the attention of Acting Director Cammerer when Jack Weightman, though no longer an employee, had "been coming into the office off and on always wearing the National Park ranger suit, which gives the impression that he is still a National Park man." Cammerer issued a memorandum stressing that departing employees had to return all insignia. [19]

Ansel F. Hall, 1920's. Hall was chief naturalist of the National Park Service, 1923-1930. Courtesy of Virginia Best Adams (Mrs. Ansel Adams) |

In March 1925 Ansel F. Hall, chief naturalist of the National Park Service, requested "a distinctive insignia for the Park Naturalists and other men engaged in educational work." He forwarded a "water color sketch" of a design and suggested that "this insignia be adopted as the emblem of the Educational Branch of the Service." This sketch was not among the correspondence, but from Cammerer's reply it would appear to have included an eagle. Hall's design may have been too complicated to be embroidered, for in September Cammerer sent him two samples of proposed Park Naturalist insignia for his consideration. One contained a bear's head and the other a bird, each superimposed over the three oak leaves used for the chief positions. After considerable correspondence, it was decided that the bear's head was the most attractive design but that it did not look well with only two oak leaves for subordinate naturalists. It was decided that both chiefs and subordinates would have three oak leaves with the bear's head superimposed; chiefs would have a light green (same as circle) 2" bar beneath the circle with "Chief Naturalist" on it. Temporary ranger-naturalists would have the bear's head surrounded by sequoia foliage like the rest of the rangers. [20]

In June 1925 Acting Director Cammerer recommended to the secretary of the interior that section 17 of the uniform regulations be amended. "As the regulation now stands, additional uniform equipment is furnished at cost prices," he wrote. "This equipment makes very good souvenirs and it has been found that certain employees, particularly temporary rangers, are willing to pay the cost price for them." He considered the metal USNPS collar ornaments government property that should be used for official business only and should be issued with a deposit like the badge. Assistant Secretary John H. Edwards approved the amendment: "Any additional collar ornaments will be furnished for official use upon the deposit with the superintendent or custodian of the cost price, the amount to be refunded upon the return of the additional collar ornaments. Badges and collar ornaments are to remain the property of the Government."

These are the two sample brassards sent to Ansel Hall. Hall selected the bears head. Attached to the bird patch is Halls' correction to the shape of the bear's head. |

Rangers A.R. Edwin & R.I. Davis at Headquarters, 1925, Yellowstone National Park. Edwins "clerk" brassard shows very clearly in this photograph. NPSHPC - YELL/130,033 |

Until now the director's and uniform committee's attempt at ironing out the wrinkles in the uniform regulations were more like bandaids than a cure. The regulations were not rewritten until the existing supply of old ones were used up. At that time any amendments that had been made since the last issue were incorporated into the new regulations. The year 1926 started with the usual routine of trying to update the current regulations with three more positions added to an already cumbersome sleeve insignia list, plus the standard change of a word or two. Two of these positions, park and assistant park naturalist, would fall into the officer category, while the ranger-naturalist, a temporary position, would reside with the rangers. To compound the problem, the chief park rangers at their conference in January at Sequoia passed a resolution "requesting that they be designated as officers of the Service." The old adage about too many chiefs and not enough Indians was becoming a reality.

When Superintendent Lewis said that he had no objections to the changes and suggested adding park naturalists and assistant supervisors to the officer list, Cammerer began to rethink the whole regulation situation. He had drawn up a list of amendments to the current regulations for the secretary's signature but decided to wait until after the superintendents' conference in November. "I think the list of officers should comprise Superintendents, assistant superintendents, chief clerks, full time custodians, engineers, chief rangers, and assistant chief rangers," he wrote in August. "I think all the others should come within the scope of the term 'employees.' " [21]

Lew Davis, c. 1925, chief ranger, Sequoia National Park. The brassard was prescribed to be worn on the right sleeve, (service insignia on the left) but Davis wore one on each sleeve. He is almost always shown wearing non-regulation boots. NPSHPC - HFC/93-327 |

Cammerer followed by appointing a committee chaired by Superintendent Owen A. Tomlinson of Mount Rainier and including Superintendent J. Ross Eakin of Grand Canyon and Superintendent Roger W. Toll of Rocky Mountain to review the new regulations with him at the superintendents' conference. In doing so he expressed his opposition to the " 'officer and men' idea of the present regulations." He noted that "no such distinction is made in the Forest Service regulations and all employees in the national forests from the Forest Supervisor down to the temporary ranger, wear the same badge and insignia." If the distinction were to be maintained, he felt that only those employees in commanding positions should be designated officers. [22]

Sketch of new collar ornament proposed by Thomas Vint in 1927. It was returned with the suggestion that the US be made smaller. It was but one of many designs submitted but not approved. National Archives RG 79 208.30 |

At the conference the superintendents voted to replace the USNPS collar insignia with a round device with DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR / NATIONAL PARK SERVICE around the perimeter and US in the center. This chore was delegated to Daniel R. Hull, chief of the Landscape Engineering Division. Invitations were also sent out to the entire Park Service to submit their ideas as to what design should be used. In January 1927 Associate Landscape Engineer Thomas C. Vint forwarded to the director a blueprint of the proposed design. (A copy of the blueprint was not found among the correspondence, although there is what appears to be a working sketch.) Cammerer returned the blueprint with the request that the design be reduced to actual size and the suggestion that it be redrawn with the US "not quite filling the entire center space."

While the engineers were working on the collar insignia, the uniform committee was wrestling with the thorny problem of the uniform regulations. The pressure was on to have them written, approved, and published for the upcoming 1927 season. The committee assembled all the suggestions into a readable format, and Chairman Tomlinson forwarded the recommendations to the director. Probably the most important of them was that all Park Service employees would wear the same uniform without sleeve insignia distinctions except among the rangers.

There were several other proposals. Trousers would be authorized for all but rangers. A cap of forestry whipcord for motorcycle rangers and all other appointees when not on patrol would be added, with an ornament. New buttons of a type and design approved by the director were recommended, as was the new collar ornament. Only rangers would wear badges—gold for chief rangers, chiefs of police, and their assistants, nickel-plated for others.

Women could wear uniforms at the discretion of the director or superintendents; those not required to wear uniforms would have to wear a collar ornament "conspicuously on the front of the waist of the dress."

These men were appointed as a committee to review the new uniform regulations at the 9th Superintendent's Conference, 1926, in Washington, D.C. Left: John Ross Eakin, superintendent, Glacier National Park Center: Roger Wolcott Toll, superintendent, Rocky Mountain National Park Right: Owen A. Tomlinson, superintendent, Mount Rainier National Park NPSHPC - Schutz Photo - HFC/WASO 3553 |

|

|

|

Left: Daniel Ray Hull, chief Landscape Engineering

Division, National Park Service. Image shows Hull in later

years. National Archives / 79-SM-47 Right: Thomas Chalmers Vint, Associate Landscape Engineer, National Park Service, 1923-1933. Vint was assigned the task of designing a new collar ornament in 1926, as well as a new badge in 1929, but was unable to come up with a satisfactory design for either. He did, however, develop a satisfactory design for the new embossed hatband. NPSHPC - HFC/RMR-253 | |

Tomlinson's letter of 2 January 29, 1927, transmitting the committee's recommendations to the director also raised the possibilities of a fatigue uniform and gilt buttons: "It has been suggested by some that the Service should prescribe a 'field or patrol uniform' for rough usage, and that we change from the bronze to gilt buttons. The uniform prescribed for station, or 'dress wear,' is too expensive for field work, and, as it is believed that our National Park Service appointees should be readily distinguishable by the public, there should be a field uniform prescribed." Tomlinson felt that the gilt button was more conspicuous and gave the uniform a "snappier" appearance.

T.C. "Tex" Worley, c. 1930 ranger, Yellowstone National Park. Worley is wearing the new uniform clothing adopted in 1928 for motorcycle rangers. Note, also, Tex is wearing his badge on his cap. As far as can be determined, he is the only one to adapt this method of displaying his badge. NPSHPC - HFC/93-364 |

When Horace Albright, in his role as assistant director (field) reviewed the proposals in March, he took exception to several sections. He did not like the cap being worn by "any officer" when not on duty, the gilt buttons, and the removal of all distinctions between the rangers and officers. Albright thought the proposals should be referred to the superintendents "for consideration at their leisure" and recommended that the 1923 regulations be kept in force until the next superintendents' conference. [23] Concurring, Acting Director Cammerer forwarded to all superintendents, copies of the existing regulations and the uniform committee proposals for them to peruse and comment on at the next conference.

Public relation photograph for announcement of new jobs for, Scoyen, Tillotson and Eakin, 1927. Photograph taken in front of Grand Canyon National Park Office (now (1973) residence of superintendent). As can be seen from this image, even superintendents weren't immune to deviations in uniforms. Scoyen's bottom pockets are rounded, while his top pockets are square with pointed flaps. Tillotson's bottom pockets are only slightly rounded. Eakin's coat has square bottom pockets, and round top pockets with scalloped flaps. Above left to right: Eivind T. Scoyen, supt., Zion National Park; Miner R. Tillotson, supt., Grand Canyon National Park; Honorable John E. Edwards, Secretary of the Interior; J. Ross Eakin, supt., Glacier National Park; Horace M. Albright, supt., Yellowstone National Park and Asst. Director (Field) NPSHPC-HFC/GRCA 89-2 |

Ranger force at Sequoia National Park, c. 1926. These two images show the variations in cut and appointments that were beginning to creep into ranger coats at Sequoia, c. 1925-26, and as can be seen by Chief Ranger Milo S. Decker, kneeling in the front of the bottom image (left end, with the service stripes on his right sleeve), Lew Davis wasn't the only one that marched to his own drummer at that park. Top photo: NPSHPC - HFC/93-338; Bottom photo: NPSHPC - HFC/93-339 |

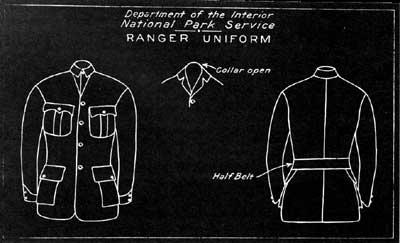

Although the Park Service had been using the same uniform drawing since 1917, the suppliers had been taking liberties with the design. All uniforms made since then, especially after the 1920 regulations came into effect, should have looked alike. But all one has to do is look at the photographs from this period to notice the many discrepancies. The regulations specified that the coat was to have a "pinch back" and that the bottom pockets were to be of the "bellows" style. The drawings submitted to the suppliers did not illustrate the "pinch back" detail, however, and not all the coats had this feature. Even though the "bellows" bottom pockets were illustrated in the drawings, many coats were made with simple patch pockets. Most did have the pleated top pockets specified.

Copy of the 1917 drawing of the NPS uniform, without N.P.S. on collar, 1926. This drawing was utilized in discussions which ended with the formalization of the uniform standard in 1928. National Archives / RG 79 |

Preliminary drawing of the 1928 pattern National Park Service uniform. This drawing was probably executed in 1927. NPSHC-HFC/RG Y55 |

Washington B. "Dusty" Lewis, c. 1925, superintendent, Yosemite National Park. Lewis was a great believer in uniforming the rangers and images always show him immaculately dressed, even in the field. NPSHPC - YOSE/RL 9429 |

Superintendent Lewis noticed the discrepancies among suppliers. In a June 1927 letter to the director he complained that "almost no two make the pockets the same, and none are stitching the cuffs as shown in the original design." He enclosed copies of the original uniform blueprint, with the N.P.S. scratched out with pencil, and a sample copy of a new blueprint, basically the same drawing with the N.P.S. eliminated from the collar. "It would be well to furnish each of the various concerns who advertise and make National Park Service uniforms, a copy of the design, with instructions that in making uniforms, this design should be strictly adhered to," he wrote. "I have accordingly had a new tracing made from which blue print No. 2 was made, which shows the uniform as was originally designed, and should be made." [24]

Acting Director Cammerer replied that the question of the back of the coat had been raised recently by one of the uniform dealers. "The uniform regulations prescribe that the coat shall have 'pinch back and half belt in back' while the blue print shows a plain back with half belt," he wrote. "This is a matter that should be corrected and I presume will be discussed at the next Superintendents' conference by the committee on uniforms." This discrepancy was corrected when the new uniform blueprints were drawn up and approved on February 12, 1928, by Cammerer. It is interesting to note that even though a new collar ornament had not been approved yet, the drawings included shield-shaped collar insignia, probably the version that Tomlinson favored.

The next superintendents' conference was held the following week at the Hotel Stewart in San Francisco. With some alterations to satisfy most objections, the uniform committee's recommended regulations were approved by the conference. Not everything had been decided; according to the minutes, "It was also recommended that the question of the adoption of a new device for collar ornament and national park emblem, leather hat band and a proper service star indicating ten or twenty years completed service be left with the permanent uniform committee for study during the next year." The proposed regulations were approved by Assistant Secretary Edwards on May 16 with minor changes, one being that the $5.00 badge deposit was made applicable to rangers only. (In 1930 the deposit was required only from temporary rangers because they were the ones most prone to "losing" their badges.)

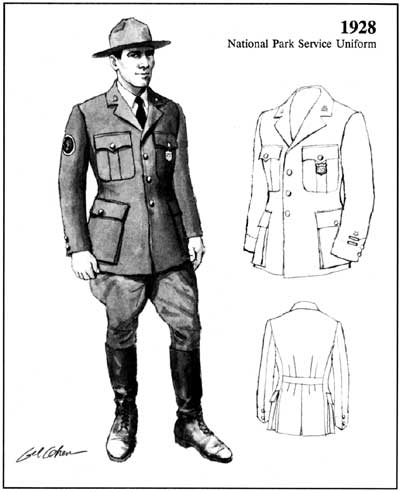

First official rendering of the 1928 pattern National Park Service uniform. This drawing was made during the controversy concerning the changing of the collar ornaments. At that time, the shield shaped ornament had the inside track, or at least the draftsman apparently thought so, since he incorporated that style into the drawing. NPSHC-HFC/RG Y55 |

Official drawing of the National Park Service Uniform, 1928. This drawing was approved by Acting Director Arno B. Cammerer on December 31, 1928. NPSHC - HFC/RG Y55 |

Minor Raymond Tillotson, superintendent, Grand Canyon National Park 1927-1939. Tillotson also served as Director of the Southwest Region 1940-1955. He served on a number of Uniform Committees. National Archives / 79-SM-48 |

The 1928 regulations were considerably different from those of 1923. Not only was there only one uniform for the Service, the only people authorized to wear badges were the superintendents, custodians, and rangers. With motorcycles coming into use in the parks, special clothing was designated for the use of those rangers. Perhaps the biggest change, other than the officer system, was the elimination of the sleeve insignia for all but the rangers. Since the matter of the collar ornament was still up in the air, the regulations specified only that this insignia be the "standard Park Service device."

The question was broached again as to what kinds of service counted for the length-of-service stripes. Superintendent Minor R. Tillotson of Grand Canyon felt that any service within the parks, no matter in what capacity, should count. Cammerer's reply laid this to rest: "I am sure the only tenable ground is to allow stripes for service in the National Park service only, as a member of such Service. To do otherwise would be confusing, and not fair to those who have actually spent the greatest number of years in the Service. It could not be argued that if one of us were to go into the army we would have service stripes for 25 or 30 years Government service outside of the army recognized. The same should hold in our organization." [25]

In December 1928 Tomlinson forwarded to the director's office for approval a revised copy of the uniform drawing. Copies were made and distributed to the field offices and the various uniform manufacturers. Along with the information pertaining to the uniform was a rendering of the ensemble.

|

In 1929 it was decided to have a new badge made for the Service. One of the current ranger badges was forwarded to Chief Landscape Architect Vint for use in preparing the new design. The new badge was designed and a drawing (not found) was forwarded to the director through Tomlinson. Tomlinson's transmittal letter indicates that there were numbers on the face: "The number as seen on the drawing is not very clear on account of the stripes of the shield behind it. It is not believed that the same effect would be found when the design is worked upon metal as the stripes are of a different level than are the numerals and would be less conspicuous than they can be shown in a drawing." Cammerer's transmittal memorandum to Director Albright provides further details: "The design for the badge does not solve the problem. The arrangement provided for the service and department names under the eagle is decidedly amateurish, and has got to be rectified. Of course the desirability of the number accounts for such revision but Vint can do better than the part-circle arrangement. It could be better to have the carrying panels for these names go straight or obliquely across."

Three naturalists at First Chief Naturalist Conference, 1929. This image illustrates the 1928 pattern coat nicely. At this time, there wasn't a regulation covering the hatband. Hall is wearing the hatband, grosgrain, that probably came with the hat. Yeager's hatband appears to be made of fabric, while Harwell is sporting a tooled leather one, similar in configuration to that later adopted by the Service. Left to right: Ansel F. Hall; Dorr G. Yeager; C.A. "Bert" Harwell NPSHPC - CPR #B-126 |

Cammerer returned the design to Vint with the request that he make up a "half dozen" alternate designs and resubmit them to Tomlinson for his review. Cammerer also relayed Albright's suggestion that perhaps the buffalo from the new Interior Department seal could be used in place of the eagle. "I realize there is something emblematic of Federal authority in the use of the eagle, and the Director has not decided yet that the eagle should not be used," he wrote. "He would merely like you to study the possibility of using the buffalo."

When Tomlinson submitted the badge design to the director, he also included a sample leather hat band prepared by Vint from a design recommended by the uniform committee at the 1929 superintendents' conference at Yellowstone. This consisted of sequoia cones and foliage tooled onto a leather band secured at the left side by ring fasteners. The front had a blank space where the name of the park could be impressed if desired. The uniform committee recommended that "U.S.N.P.S." be used instead. Silver acorns were used as ring ornaments on the sample, but it was thought that sequoia cones would be more appropriate. [26]

Approved 1930 pattern National Park Service Hatband NPS Archives RG Y55 |

The hatband was approved by the director on January 16, 1930, and estimates were obtained from a manufacturer in San Francisco. The hatband with silver sequoia cone ornaments would cost about $2.00 when purchased in lots of 150 or more. It was decided that it would be most economical for the Service to purchase the die and loan it to the manufacturer when it was desired to have more hatbands made, as was done with the collar ornaments. Because hatbands would be paid for by the employees, they could retain them upon leaving the Service.

Arthur E. Demaray, 1933. Demaray was associate director for many years, finally becoming Director the last 8 months of 1951. NPSHPC - Grant photo - HFC/WASO #273 |

Because the Landscape Division was having trouble coming up with a satisfactory design for a new badge, Tomlinson, in response to an inquiry from Albright, suggested in March 1930 that the Service try to come up with enough old badges that could be repaired for the coming season. Not enough serviceable badges could be found to cover the parks, so the Service ordered 100 of the present style in June. These differed from the badges in service by being stamped in one piece rather than assembled from two pieces. This economy measure may have resulted from the daily expectation of a new design coming off the drawing board. [27]

A letter from Acting Director Arthur E. Demaray to Tomlinson indicates that ranger badges were then being issued to fire fighters:

Superintendent Eakin at Glacier has just sent in a request for thirty badges for use of the fire protection force during this season. We have only 24 of these badges on hand, of which we are sending him ten. This leaves us with only 14 of the nickel-plated badges on hand, although we have a few of the gold badges of the same design, the latter, however, being for use of the Chief Rangers.

We do not wish to re-order the old style unless absolutely necessary, but we may have to do this should the other parks desire to furnish them to their fire-fighting forces. [28]

Thomas J. Allen, superintendent, Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, 1928-1931. Image appears to have been taken when he was either chief ranger or assistant superintendent at Rocky Mountain National Park. NPSHPC - Thomas J. Allen Collection - ROMO/911 |

In November 1930 Superintendent Thomas Allen of Hawaii National Park suggested that the Service authorize bow ties to be worn with the uniform. He thought that they were "more practical and present a neater and more consistent appearance with park uniforms." He stated that it was hard to find green ties and unless everyone bought from the same store and batch, each one was a different shade. "Here in Hawaii men discard their coats a great deal and it is the custom of a great proportion of them to wear bow ties," he continued. "I find the reasons for this to be that ready tied bows are always neat, there are no ends to flap in a breeze, and they are cheaper than four-in-hands. My impression now is that a standard ready tied green bow would be an improvement in the appearance of park uniforms."

Allen's bow tie suggestion was apparently not pursued, but others shared his concern about the lack of uniformity in ties. "We have green ties prescribed, but I have been in parks where a Superintendent, upon meeting me, wore a red tie with his uniform, making an utterly ridiculous appearance," Cammerer wrote Tomlinson in 1928. A later photograph shows a ranger wearing a tie with small white polka dots on it.

As 1931 began, the push was on to finalize the designs for the new collar ornaments and badges so that they could be issued for the upcoming season. Tomlinson had submitted four designs for the new ranger badge and four designs for a new employee identification badge with a letter of December 6, 1930, to the director's office. Design number 4, favored by the uniform committee, would have a serial number and the name of the park. The numbering of the badges would make them cost more and take longer to produce. The badge was slightly smaller than the current one, and Cammerer thought it should be larger. He wished to have two or three alternate sizes prepared to facilitate the decision, including samples with the buffalo rather than the eagle.

These questions caused Director Albright to decide that the present badge would be continued for the coming season. The existing collar ornaments were also kept in the absence of "inspiration" leading to "something really appropriate." The employee identification badges were held in abeyance for reasons of cost.

Three naturalists at First Chief Naturalist Conference, 1929. This image illustrates the 1928 pattern coat nicely. At this time, there wasn't a regulation covering the hatband. Hall is wearing the hatband, grosgrain, that probably came with the hat. Yeager's hatband appears to be made of fabric, while Harwell is sporting a tooled leather one, similar in configuration to that later adopted by the Service. Left to right: Ansel F. Hall; Dorr G. Yeager; C.A. "Bert" Harwell NPSHPC - CPR #B-126 |

More parks were being created in the East where the weather was hot and humid during the summer season. The regulation wool uniform with breeches and puttees was totally unsuited for this climate. The 1931 season brought with it a considerable correspondence requesting relief for the rangers assigned to these areas. The breeches and puttees seemed the most objectionable. Most agreed that long trousers, cotton shirts, and some sort of lightweight headgear would be the most appropriate. Materials such as gabardine, white linen, and a khaki-type cotton dyed forest green were suggested. That July, Acting Associate Director Demaray asked the uniform committee to "consider some modification of the uniform regulations that will permit the use of a uniform that would be reasonable for the hot midsummer climate of the East."

Asst. Park Naturalist Yeager, 1931. Yellowstone National Park. Apparently, only rangers were required to wear the full uniform when coming in contact with the public. NPSHPC - YELL/130,185 |

Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming - Ranger Wayne Replogle, Tower Junction, 1932. Replogle is shown displaying a set of elk horns on his motorcycle at Tower Junction. He is also wearing the motorcycle cap authorized in the 1928 Uniform Regulations. NPSHPC - YELL |

The committee offered two solutions to this dilemma: "First, a uniform coat and trousers made of cotton material similar to the khaki used for army and marine corp [sic] uniforms; and second, a coat and trousers made of very light weight forestry serge." For a hat it suggested a lighter weight version of the present hat or "a cap similar in style to the English army officers' cap made of the same material as the summer uniform." Tomlinson went on to say that "in case a summer uniform is adopted for those parks where climatic conditions make it desirable, . . . all members of the organization should be required to wear the same type uniform and . . . no park or monument [should] be permitted to wear anything but the present prescribed uniform except on specific approval of the Director. [29]

Asst. Chief Ranger LaNouse and Ranger Phillip Martindale, 1932, Yellowstone National Park. Martindale is wearing the double-breasted "mackinaw type" overcoat authorized in the 1928 Uniform Regulations. NPSHPC - YELL/130,149 |

Acting Director Cammerer asked the committee to prepare a drawing and specifications for the proposed summer uniform with "a cotton material similar to khaki" in mind. The committee was to include the "English Army officer's" cap on the drawing. When "something concrete" was arrived at, the superintendents were to be polled in anticipation of there being a conference in the fall. If there was a conference, the uniform could be judged on the basis of the poll. Meanwhile the committee was to try to locate suitable materials. Because the summer was nearly over, Cammerer did not think that the Service should approve any revisions of the regulations until they were "carefully studied, recommended and approved in regular routine." [30]

Horace M. Albright, his wife Grace and Superintendent William M. Robinson, Colonial National Monument, May 14, 1933. Robinson thought that khaki uniforms looked too much like the military and thought white would be more appropriate, leastwise for Colonial. NPSHPC - HMA Collection |

In January 1932 the uniform committee sent its formal recommendation for a summer uniform to the director. The committee thought that the existing style of uniform could be made out of khaki, with trousers in place of breeches. Included with the letter were two samples of the khaki material used by the Marine Corps for its uniforms and shirts. The Marine Corps quartermaster in Philadelphia had been contacted and was agreeable to making the uniforms needed by the Service, providing the problem of reimbursement could be worked out. The depot quartermaster stated that this would require legislation but thought it would be approved.

When the parks were informed, all but Superintendent William M. Robinson of Colonial National Monument agreed with the uniform committee. Robinson insisted that khaki uniforms looked too much like the military and thought that white uniforms were more appropriate. He felt that Colonial National Monument should have a distinctive uniform for its rangers in any event. Tomlinson wrote him in response:

"It is the Uniform Committee's understanding that it is the desire of the Director and of practically all of the field officers and park superintendents to keep the uniform standard throughout the entire National Park and National Monument Systems, rather than to authorize different uniforms for the various units. It is my opinion that the greatest value of the National Park Service Uniform is the fact that it is the same in Alaska, Hawaii, the Southwestern Monuments, Maine and all other national parks. The public is fast learning to recognize our uniform and we should I believe, encourage uniformity in every possible way." [31]

Director Horace Marden Albright and his Washington staff, 1932. Albright was director of the National Park Service 1929-1933. Left to right: Conrad L. Wirth, asst. dir., Arno B. Cammerer, asst. dir., Ronald M. Holmes, chief clerk, Albright, Harold C. Bryant, asst. dir., Arthur E. Demaray, asst. dir. (operations), George A. Moskey, asst. dir., Isabelle Florence Story, editor NPSHPC - George A. Grant photo - HFC/WASO #17B |

Director Albright decided the matter on February 15, 1932, by approving Supplement No. 1 to Office Order No. 204. The new summer uniform was to consist of:

(a) Trousers, rather than breeches, of the style and cut now authorized for the standard uniform, of khaki material.

(b) Khaki blouse, of exactly the same style as the present woolen blouse.

(c) Shirt, gray flannel of light or medium weight with collar attached; or gray cotton with collar attached.

(d) Cap, of the same material as the uniform, to be of the English army officer type.

The summer uniform was to be worn complete, with no mixing of items with the other uniform. [32]

Pete Bilkert, infamous highwayman in Jackson Hole, his hide-out. Picture made possible only by a chance meeting with photographer while outlaw was in a good humor. Samuel Tilden Woodring, superintendent, Grand Teton National Park, 1929-1934, and Peter E. Bilkert, Chief of the Statistical Division, NPS. Note the NPS on the horse and saddle blanket. NPSHPC - George A. Grant photo - GRTE/#140A |

In March 1932 the Service proposed to have the San Francisco office enter into a contract with a single supplier so that employees could secure uniforms of a standard color and quality at the lowest cost. Uniform orders would be placed by the parks, the Service would pay the supplier, and the costs would be deducted from the employees' pay. A deposit of at least 25% would be required from prospective employees. To facilitate getting the best possible price, all the parks were asked to send in their requirements for the upcoming season. The replies came in with all manner of remarks and uniform requests, one of which called for a "Ladies coat & skirt."

Roger W. Toll with tame bobcat. Toll was superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, 1929-1936. During this period, it wasn't unusual for parks to keep tamed "wild" animals of the area to show tourists. NPSHPC - CACA / WASO - H-165/297 |

Four rangers at Two Medicine Camp Ground. Arnold, etc. Glacier National Park, 1932. NPSHPC - George A. Grant photo - GLAC/#73A |

The annual superintendents' conference was held in April at Hot Springs. Several new uniform items came out of the conference. A raincoat was authorized for the first time. It was to be of a "durable, lightweight waterproof material, doublebreasted, full belted model, with set-in sleeves; color, deep sea green." All ranger badges were to have identification numbers, and new bronze metal badges, serially numbered, were to be issued to fire guards. The length-of-service insignia was altered by adding a gold star for ten years to the existing 1/8" x 2" black braid for one year and silver star for five years. This was necessary because some of the old timers' sleeves were starting to look like constellations.

Meanwhile Chief Landscape Architect Vint was tackling the problem of the new badge. In January 1932 he sent four more designs to Tomlinson. Tomlinson wrote Ross Eakin: "I do not care particularly for any of them. 'B', showing a shield type badge with the bear is, in my opinion, the best of the four designs. However, I like our present badge as it is better than any of these proposed designs . . . . personally I am not in favor of a bear on the ranger badge."

The problem with the badge design seems to have been in its requirements. It had to tell who its wearer was (U.S. Park Ranger); have a number, like police badges; have "National Park Service, Department of the Interior" in legible letters; and have a symbol of some type (eagle, buffalo, etc.). All this had to be in a fairly small, attractive package, with the shield being the favored style. Vint was kept drawing up designs, which were then turned down without anyone offering any real suggestions, except for Albright's request to "consider the buffalo."' (None of these drawings have been found.)

Uniform regulation compliance in some parks had become very lax over the years. Employees were smoking when talking to tourists, walking around with their blouses unbuttoned, and wearing nonregulation clothing. Photographs show Lew Davis in Sequoia wearing the sleeve insignia on both sleeves and another Sequoia ranger with service stripes and sleeve insignia on his right sleeve. These peccadillos came to the attention of Director Albright, who sent a memorandum to the park superintendents on June 9, 1932:

"The summer tourist season in the National Parks and National Monuments is about to open. In some parks the summer season is well advanced. I want to take occasion to emphasize again my great interest in having all of our personnel who come in contact with the public dressed in neat, well-fitting uniforms. There is nothing more important in the operations of the National Park Service than to have our contact officers in uniform. Except when heat makes impossible the wearing of the uniform jacket, the complete uniform should be worn. It is desired also that the new tropical worsted cloth, nine ounce weight, be used in making uniforms to be worn in the Southwest as well as in the East.

In view of the many letters and memoranda that have been written throughout the past few years emphasizing our interest in the full enforcement of our uniform regulations, Superintendents and Custodians must not feel disappointed if officers of the Washington staff traveling on inspection are disposed to judge a park or monument and its organization to a certain extent by the uniforms which the employees are wearing and the condition in which they are kept." [33]

Mount Rainier National Park Rangers, early 1930's. Left to Right: (back row) Oscar Sedergren, ?, Preston P. Macy, Frank Greer, Davis (front row) Carl Tice, Charles Brown, Harold Hall, Herm Bamett The appearance of these rangers is what all of the parks were striving for, even though Brown has on non-regulation boots. Their ranger brassards show very clearly. NPSHPC - HFC/91-12 |

Albright followed this the next month with another memorandum to the superintendents. He had heard that there was a tendency for the men to get out of their uniforms in the evenings, especially around the hotels, lodges, and camps. "There is only one person whom we are willing to allow out of uniform when associating with the public, and that is the Superintendent himself," he wrote. He felt that this gave the superintendent a respite from the public and better enabled him to observe the service being given the public by his organization. He again mentioned the problem of rangers contacting the public with their shirts open, without ties or hats, and smoking while directing traffic and meeting visitors. He thought it "a pity that the Director and his field offices have to keep bringing to the attention of Superintendents the importance of enforcing our vital regulations" and hoped he did not have to send another memo to the superintendents about these matters. All the superintendents responding professed to be following the regulations to the letter but said they would pass on Albright's thoughts.

In 1932 Congress passed an act to prohibit the unauthorized use of official federal insignia. Samples of all the badges and insignia worn by employees of the National Park Service were forwarded to the Department of Justice for its records at the end of July. [34]

Now all the Service needed to do was to finalize the new badge and collar insignia.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

nps-uniforms/3/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 01-Apr-2016