Naturalists, Rangers, & Historians

Senior Administration Officers

|

Organizational Structure of the

National Park Service - 1917 to 1985 - Administrative History |

|

Introduction

Horace Albright, Conrad Wirth, and George Hartzog at the Grand Canyon in the 1960's discussing improvement through training at the dedication of the Horace M. Albright Training Center. |

There have been many books, pamphlets, and articles written about the National Park Service over the years. All of them have dealt with the policies, practices, philosophies, and to some extent, the people as individuals who have influenced the Service and the National Park System. There has, however, not been anything that depicts the organizational structure, its growth, and/or the influence that people within the organization have had on the organization. What began as an agreement to update a listing of Washington Office key officials has expanded in an effort to put on paper the graphic organization over the years that will add to the continuing administrative history of the organization.

The Service has been called a "family organization." John Carver, a former Assistant Secretary, condemned the "mystique" of the Service. Both are evident when the organizational structural history is looked at from its beginning to the present. When reviewed along with literature such as The National Park Service by William C. Everhart, Parks, Politics and the People by Conrad L. Wirth, Family Tree of The National Park System by Ronald F. Lee, The National Parks: Shaping the System by Barry Mackintosh, Administrative History: Expansion of the National Park Service in the 1930's by Unrau & Williss, and America's National Parks and Their Keepers, by Ronald A. Foresta, it becomes very apparent that the organization and the people within it have had a profound influence on each other over the years. The sense of family and the mystique can be visually related to what has gone on over the past 68 years. Individuals who were in the organization in the early years continued through the 1940's, 1950's and 1960's. R. M. Holmes, who was the Chief Clerk in 1925, was still the Assistant Personnel Officer in 1938; Frank Kittredge, who was Chief Engineer in 1928, was the first Regional Director of Region IV (Western), was Superintendent of Yosemite in 1942 and again Chief Engineer through 1952; Harold Bryant, who was Assistant Director, Research & Education in 1928, was Superintendent of Grand Canyon in the 1940's; Preston Patraw, an early Superintendent at Bryce and Zion, was Finance Officer in the 1940's; Howard Baker, a landscape architect in the early 1930's, Chief of Planning and Design in Omaha, and Regional Director in Omaha in the 1950's, retired as Associate Director in the late 1960's; Eivind Scoyen, Superintendent at several areas from the 1920's, retired as Associate Director in the mid-1960's, to mention a few. These people and many others molded and shaped those that followed. Fathers begat sons and daughters who have continued the "mystique" and furthered the family image. As examples, Benjamin Hadley, Superintendent, son Lawrence, Superintendent and Assistant Director; Daniel J. Tobin, Superintendent and Regional Director, sons, one at Yellowstone and Daniel Jr. (Jim), Superintendent, Deputy Regional Director, Associate Director and Regional Director; John Cook, Master Mechanic, son John Cook, Superintendent, grandson John Cook, Superintendent, Associate Director, and Regional Director; Gabriel Sovulewski, Park Supervisor, Yosemite, son-in-law Frank Ewing, Trail Foreman, and grandson Herbert Ewing, District Ranger; Fred Binnewies, Ranger, Superintendent, sons Robert and William, Superintendents. Many of the individuals prominent in the early organization are still alive and continue to have influence on the Service as it exists today. That factor was emphasized to Director George B. Hartzog in the late 1960's by former Director Horace Albright after one of his yearly inspection trips to Yellowstone. Albright, and indeed all retired employees, believe they retain the inalienable right to suggest ways of improving the operations of the National Park Service.

Although August 25, 1916, is recognized as the establishment date of the National Park Service, it was not until May 16, 1917, with the appointment of Stephen T. Mather as Director, that a formal structure was established. From a simple beginning the Service has evolved into what is now a highly complex organizational structure. Stephen Mather's "family" organization has grown to an organization of interdependent groups having differing ways of accomplishing work, yet they are still interrelated subsystems of the whole. There is, however, a decided difference in the "family" of yesterday versus the "family" of today. The evolution of National Park Service organizational structure has been the result of both internal and external forces acting on the organization and the people within the organization. Organizational change occurs in all organizations (work, home, church, etc.). What one must consider is that specific actions to initiate organizational change are taken by people, and complex organizations being what they are, those at the head are the primary change agents.

Basically, there are two kinds of organization, formal and informal. The term formal, as it relates to organizational structure, refers only to the fact that those responsible for maintaining the existence of the organization can describe its form in language and symbols such as charts and manuals. An informal organization is that which is not documented or made a part of some sort of continuing record. Such organizational structure definition is not to be confused with how an organization accomplishes its work. The National Park Service has a long history of organizations that work through people moving up, down, or laterally, where "titles" and "report to's" mean little as long as the mission of the Service is or was accomplished.

What is interesting when one looks at the National Park Service organization charts over the years is:

- With the exception of new program thrusts, program additions or deletions, the organization has functioned with substantially the same supervisory structure.

- The formal structure, while exhibiting growth has basically remained the same.

- The organization was and is a social structure, although in the past several years the social aspects of the structure are far more apparent in the field and through the Employees and Alumni Association, the 1916 Society, and the National Park Service Wives Association.

- There is a line of continuity that stretches back to 1917. People remained a part of the organization for long periods of time.

- Organizations were developed around people.

- On the average, there has been some sort of organizational change every 22 months.

Since 1917, there have been periods of time where no formal documentation exists. There are, for example, no official, formally approved organization charts for 1917, 1918, 1920 through 1924, the mid-1940's, 1964, 1967, mid-1970, 1971, and 1982. A reason for this may be that prior to 1955, organizational approval was vested in the Director of the National Park Service. After 1954, organizational approval was held at the agency (Department of the Interior) level with the establishment of a Departmental Manual (the National Park Service portion of the Departmental Manual is Part 145). However, for the period 1916 to 1985 we were able to locate more than 55 examples of formal and informal descriptions of organizations from which it was possible to develop 38 organizational depictions. These sources ranged from National Archives documents to telephone directories.

As one looks at the organizational structure there have probably been no more than eight major changes in how the Service was organized to accomplish its mission. As examples, the following might be considered as major:

- First organization in 1917 (for obvious reasons).

- Establishment of program Assistant Directors in the 1920's.

- Effect of Executive Order 61661 and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) program in the 1930's.

- The establishment of Regional Offices in the late 1930's.

- The establishment of centralized design and construction offices in the 1950's.

- The establishment of the Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation in the 1960's.

- The establishment of the Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service in the 1970's.

- The abolishment of the Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service in the 1980's.

Expressed as an opinion not substantiated by known fact, the remainder of the changes were more process changes or changes in flow as to who accomplished the business of the Service. In assessing and describing the organization, an hypothesis was drawn that an organization takes on the flavor of those individuals at the head of the organization. For example, Mather's interests revolved around the management of the parks, which was one of the reasons that Franklin Lane appointed him. His organizations were small central offices designed to meet necessary park needs. As there was a recognition of increased need, his apparent thrusts were to put the needs close to the parks.

In its beginnings (1917 through 1918), the Headquarters appears to have been a small policy and oversight office for the national parks and monuments, as well as a housekeeping function vested in a Chief Clerk who was responsible for routine bureau activities (personnel, mail and files, small purchases, and accounts). In 1919, Engineering and Landscape Engineering appeared as identifiable functions and were located in a series of offices on the West Coast (see chart #2). Location of offices in the west (in Los Angeles, California, in Portland, Oregon, in the Underwood Building in San Francisco, California, and on the Berkeley campus of the University of California) made sense, as prior to 1933 the majority of the national parks and monuments were west of the Mississippi River. If one traced the Design, Planning, and Construction functions they would date from this period. Although not showing up on an organizational chart until he replaced Daniel Hull, Thomas C. Vint was on board in the early 1920's. His influence on planning and design was to continue through the early 1960's and still continues today. Individuals who worked for Vint branched out over the years to become regional directors and park superintendents and to occupy other high level positions.

1 Executive Order 6166 transferred 2 National Parks, 11 Military Parks, 10 Battlefield sites, 10 National Monuments, 3 miscellaneous memorials, and 11 National Cemeteries from the War Department to the Office of National Parks, Buildings and Reservations of the Department of the Interior.

Arthur E. Demaray in the 1930's. From a historical viewpoint one of the most influential, tireless, behind-the-scenes National Park Service employees. |

As the Service grew, by 1925 the importance of public relations and administration as we think of them in 1985, was reflected in the establishment of a function of Operations and Public Relations (as one reflects, Mather was considered by many to be a great salesman and many of his actions reflected this skill) headed by an Assistant in Operations and Public Relations (see chart #3). One should note that Administration, as it is known today, was titled Operations and it was not until 1951 that it was to become specifically titled an administrative function. Arthur E. Demaray, after starting as a draftsman in 1917, was to become an Assistant Director, Associate Director, and Director in the course of a 34-year career with the National Park Service. What began as an investigative unit in 1925 and subsequently became Auditors of Park Operators (concessions) Accounts was what appears to be the genesis of the current Concessions Division. The early functional statement read: "Examine and audit the books of the public utilities which operate in the National Parks and Monuments under franchises; obtain by independent investigation full details concerning operations and financial consideration of public operators; recommend changes in rates or services." Comparing this to this current functional statement there is little change except in language usage.

George A. Moskey, the first National Park Service lawyer, 1927 to 1944. |

C. L. Gable was in effect "Mr. Concessions" from 1925 to 1946. An education (natural history) unit or the beginnings of the Service interpretive program was also established in a California office on the University of California's Berkeley campus. By 1927 the Service had established its own legal function (see chart #5) that was to continue until the mid-1950's when all legal functions were consolidated in the Department of the Interior's Office of the Solicitor. In this 28-year period the Service was to have only two legal officers, George A. Moskey for 17 years and Jackson E. Price for 11 years. An interesting point is that for many years, well into the 1950's, the lawyers actually did all contractual work for the Service. Today, procurement is an accepted part of the Administrative function.

Jackson Price went on to become an Assistant Director and a Regional Director before retiring in the late 1960's. This can be construed as family if one is so disposed, as functions moved out of the Service or were dropped anyone who wanted to stay with the Service did so. In 1928 the title of the Director's alter-ego position was changed from Assistant Director to Associate Director; the title did not change again until 1967 when it became Deputy Director. Arno B. Cammerer held this position from 1919 until he became Director in 1933. He then went on in 1940 to become Regional Director, Region I, Richmond, Virginia (now Southeast Region, Atlanta, Georgia). In 1928, there was organizational recognition that forestry was important when Education and Forestry became a combined organizational entity. When Education and Forestry were combined the functional statement read: "Supervises museum construction and installation of exhibits; forestry projects and fire prevention; carries on survey of wildlife." This unit, if tracked through the organization, (see chart #39) was the beginning of the resource management, museum and exhibit productions, and ranger activities functions as they exist today in the Division of Visitor Services, Harpers Ferry Center, the Division of Biological Resources and the National Park Service portion of the Boise Interagency Fire Center.

Jackson E. Price, the second and last lawyer on the Headquarters staff, was also an Assistant Director and Regional Director before he retired. |

By 1930 (see chart #7), the Headquarters office had five well defined functional activities, four of which were then or would come under Assistant Directors: Operations (administrative functions), Legal, Research and Education, and Land Planning. A Chief Clerk handled the "housekeeping" function until 1931 when it was placed under Operations. A history function (see chart #8) appears for the first time under the Branch of Research and Education. By 1931 the administration of Southwestern National Monuments was a firmly entrenched management function. This may well have been the recognition, as the Service grew, that Washington could not directly administer every National Park Service area (see chart #8).

Mather and Albright, although differing personalities, were of like mind when it came to the national parks and the National Park Service. Both were expansionists and believed in use of the parks by people, which can be read into the organizational structure--everything for the parks and a small Headquarters office. Road building, museum construction, and interpretive exhibits for the visitor show up functionally. Cammerer, a career employee, was also expansionist, but was also a product of his times. He benefited from the Roosevelt Administration's decision to use the parks in the execution of its social and economic programs. His organizations reflect this growth and his long association with the bureaucracy. Functions were structured, management was orderly, and growth came to the Headquarters office; decentralization occurred throughout Cammerer's directorship.

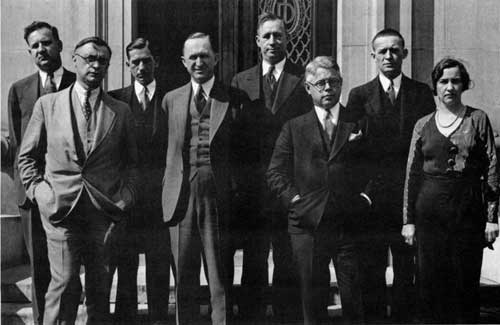

Director Albright's staff in the early 1930's. Front row L to R:

Arno B. Cammerer, Associate Director; Director Albright; Arthur E.

Demaray, Assistant Director, Operations; Isabelle Story, Editor;

Back Row L to R: Conrad L. Wirth, Assistant Director, Lands; R. M.

Holmes, Chief. Clerk; Harold C. Bryant, Assistant Director, Research &

Education; George A. Moskey, Assistant Director, Use, Law &

Regulation.

Verne E. Chatelain, First National Park Service Historian and Assistant Director, Historic Sites & Buildings. |

As one looks at charts for 1933 and 1934 (see charts #10 & #11) it is apparent that functionally the Service was becoming more specialized. The CCC functions, although not specifically mentioned, were in a Recreational Land Planning unit under Conrad L. Wirth who was subsequently to become Associate Director and Director. Although not appearing on any formal chart, the decentralization of the CCC program and the decentralization of the Planning and Design functions into Eastern and Western Divisions with district offices (see chart #11) may well have been the genesis of the thinking to establish Regional Offices. The late 1934 organization (see chart #11) clearly reflects Executive Order 6166 and the needs of the organization to accommodate its increased functions or responsibilities. History achieved Branch status in 1935 with a supervising Assistant Director (see chart #12).

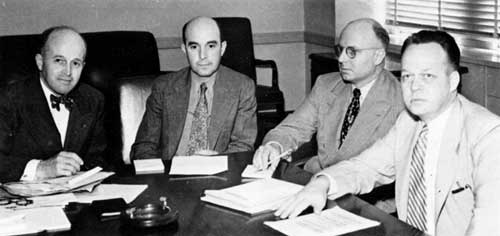

The first Regional Directors from L to

R: Frank Kittredge, Region IV, San Francisco, California; Thomas Allen,

Region II, Omaha, Nebraska; Herbert Maier, Region III, Santa Fe, New

Mexico; Carl Russell, Region I, Richmond, Virginia.

The organization formally approved in October 1938 [1] (see chart #15) did two things. It established a new way of of managing by creating Regional Offices. Additionally, for whatever reason -- internal politics or external politics or perhaps even a power struggle or, as suggested by George Palmer, a major funding problem -- all Assistant Director positions were abolished. The Conrad Wirths, Hillory Tolsons, Ronald Lees, etc, all became Supervisors of functions. It was not until July of 1943 (see chart #17) that Hillory Tolson would again become an Assistant Director in the Chicago office where the Service Headquarters was moved to during World War II, and it was not until 1949 (see chart #20) that an additional Assistant Director position for Conrad Wirth was again created. Newton Drury, although of the same era and same school system (University of California, Berkeley) as Horace Albright and Lawrence Merriam (Regional Director, Omaha, Nebraska, and San Francisco, California), was restrained by his stringent sense of bureaucratic propriety. Characterized as a "died in the wool purist," he espoused a caretaker role for the National Park Service as well as minimal development. He did not like the rough and tumble politics of Washington, which did not do either him or the Service any good. His preservation philosophy during the war years did serve the Service well as he was able to keep the Army and Navy from running away with the parks. Several historians view that even though Mr. Drury was constrained by the war years his administration was a clear shift of emphasis from that of Mather, Albright and Cammerer. It perhaps initiated a reversal from which the Service has never totally recovered as its functions became more diverse. His handling of the Echo Park Dam controversy in Dinosaur National Monument was divisive to the organization's external support.

Newton B. Drury, the fourth National

Park Service Director, being sworn in August 20, 1940. L to R: Under

Secretary Wirtz; Floyd Dotson, Chief Clerk, Department of the Interior;

Director Drury; Secretary Harold Ickes.

An interesting organization was that in the Chicago office during the World War II years (see chart #17). Arthur Demaray as Associate Director remained in Washington while Director Drury and Assistant Director Tolson relocated to Chicago with the Headquarters office. Mr. Demaray remained in Washington because he was apparently the only experienced Congressional liaison person who could defend the Service's funding requests. It would appear that Mr. Tolson ran the day-to-day operations of the Service during this period. Organizationally, Branches were still the major entity with Divisions as a sub-unit, yet three Divisions and the Chief Clerk (appearing again after a 5-year lapse) reported to the Director's office. One would have to make the assumption that Finance, Personnel, Safety, and the Chief Clerk reported directly to Mr. Tolson who, by this time, had complete control of the administrative process of the organization while, at the same time, having direct influence over every other aspect of the Service's mission.

Thomas Vint in the Planning and Design Office. |

An interesting sidelight: Regional Directors were moving between Regions and Washington Branches. A cadre of long-term Regional Directors was becoming apparent with Thomas Allen, Lawrence Merriam, and Minor Tillotson. By 1946, Mr. Vint had become "Mr. D&C" with the combination of his Branch with the Branch of Engineering into a new Branch of Development (see chart #18). Concessions as a Division had emerged -- looking at the timeframes this may well have been the organizational response to visitors again coming to the parks after the wartime hiatus. From a functional standpoint there were units for Planning & Design (Development), Lands, Concessions, Natural History, and Forestry which would eventually become Ranger Services.

Hillory A. Tolson. |

It became clear in the 1948 organization that this structure clearly delineated who did what at the Directorate level. The Director (Mr. Drury) held to himself the Legal and Public Relations functions; at the time these were the areas that were important to Mr. Drury. The Associate Director was responsible for Lands & Recreation Planning, Development (Design and Construction), and Public Services. Assistant Director Tolson was responsible for administration, and some of the functions that would eventually become a part of today's operational directorate functions. When Newton Drury left as Director, Arthur Demaray was appointed Director; however, he had already informed the Secretary of his intentions to retire by year's end and the supposition can be made that the Directorship was a reward for long and faithful service to the organization. Mr. Demaray was an extremely popular Assistant and Associate Director, had an exceptional memory, was practical, and was apparently outstanding in his appearances at legislative and budget hearings. Ben Thompson, in a National Park Service Courier article, extolled Arthur Demaray's role in the develop ment of the Service and the National Park System. His knowledge of the budget was such that he would testify before the appropriations committee from memory with his budget book unopened on the table in front of him. It was quite clear that with the appointment of Conrad Wirth as Associate Director he was the heir apparent. The Demaray organization of May 1951 (see chart #21) bears this out. It was in reality the first Wirth organization. There was again a clear division of duties. Hillory Tolson had all the administrative functions and forestry, the Associate (Mr. Wirth) had Design and Construction, Lands, and Concessions, his personal interests, and Ronald Lee had the remainder. Many of Mr. Wirth's key advisors were in positions of influence. If you were to look closely at the 1933-34 CCC organization you would note that Mr. Wirth's "cabinet" consisted of largely the same people who were with him there. When Mr. Wirth became Director in December of 1951 the Directorate was organized with the Director and three Assistant Directors (see chart #22). Again, if one relates the personality of a Director to the organization, Mr. Wirth's organizations reflected his background as a landscape architect and a planner. Philosophically, Wirth was more akin to the earlier Directors. He was a use-oriented Director. Mission 66, promoting park improvement, access, and use, clearly bears this out. It has been said that Mission 66 was in part the completion of Mr. Wirth's CCC program for the Service that was interrupted by World War II. One hundred and fourteen visitor centers were built, the in-Service training centers (Mather and Albright) were built, and reservoir-based recreation was developed. Where Drury had good relationships with the conservation groups, Wirth had poor relationships and, unlike Mather and Albright, as a career civil servant, he did not have the business type associations for support of the Service as they did. His advisors had similar backgrounds or were former CCC staff from that period in his career for which he was recognized as a capable administrator. As an aside, a certain amount of influence was also exerted by Mr. Wirth's carpool of the late 1950's and early 1960's, which consisted of Raymond Freeman (who would be a Deputy Director under Hartzog), William Bahlman (who was Mr. Wirth's organizational advisor), Edwin Kenner (who was Chief of Maintenance), and Sidney Kennedy (who was a planner). Each of these individuals had positions of influence in the organization. The Design & Construction function reported directly to the Director -- a clear indication of the relationship between Vint and Wirth.

The Stephen T. Mather Training Center,

Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, and the Horace M. Albright Training

Center, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona, both Mission 66

projects.

1 In actuality the Regional Offices were set up in late 1937 but not formally charted until 1938. S. Herbert Evison vividly recalls that on June 1, 1936, an office was established in Richmond, Virginia, that was the "pattern office" for other Regional Offices established in 1937.

Lemuel A. (Lon) Garrison, Chief, Branch of Conservation & Protection, the field rangers' Washington Office representative. |

With the September 1954 organization (see chart #23), Administration was to become a cohesive unit and Operations as a functional entity formally began (the Branch of Conservation and Protection under Lemuel Garrison was the field rangers' Washington Office representative). This organization also consolidated Mr. Vint's influence over Design & Construction with the establishment of Field Design offices and the removal of the planning, design, and construction activities from the Regional Offices.

By 1956 and with the establishment of the Mission 66 program of park renewal (a particular interest of the Director), Mr. Wirth apparently felt he needed assistance in running the organization and re-established the Associate Director's position (see chart #24). He filled it with an experienced park superintendent, Eivind T. Scoyen, who, although not appearing on previous organization charts, had been a superintendent with increasing responsibilities in park management since the 1920's. Perhaps this was the beginning of a recognition that there was a Washington Office bureaucracy and a field bureaucracy that needed to be melded together. This dichotomy exists today and each succeeding Director has struggled with an appropriate balance. In this same organization a new regional office in Philadelphia was established.

A typical Mission 66 project in the Pacific Northwest.

Ronald F. Lee & John Doerr, two long term Washington Office employees. |

Although people moved in and out of Washington, there was a hard-core of continuity of Branch/Division chiefs with long term varied Headquarters experience (Thomas Vint, Design & Construction; S. Herbert Evison, Information & State Cooperation; Charles Richey, Lands; Donald Lee, Lands & Concessions; Ronald Lee, History & Operations; Herbert Kahler, History; Hillory Tolson, Administration & Operations; Frank Ahern, Safety; John Doerr, Natural History & Interpretation; and Lawrence Cook, Forestry & Ranger Activities).

The organizations of the late 1950's and early 1960's were not particularly distinctive (see charts #23 & #24). Maintenance appeared as an organizational entity as did formal recognition of the ranger role with the establishment of a Division of Ranger Activities reporting directly to the Director. The 1957 organization (see chart #25) reflects the push and pull between Washington and the Field as well as any organizational structure up to this point Administration was Administration, Design and Construction influence over the physical and projected appearance of the parks was never stronger. The Mission 66 staff through William Carnes had strong ties to earlier Design and Construction relationships, his personal relationship with Thomas Vint going back to the early 1930's. Interpretation under Ronald Lee (a historian) and Daniel Beard (an interpreter of natural history, and first superintendent of Everglades National Park) had a strong influence over the historical and eastern parks. Recreation Resources Planning, or the "planners of the future," were former staff in the CCC program under Mr. Wirth. Apparently, the creation of the Ranger Activities Division (see chart #25) reporting to the Director was clear recognition that "the uniformed ranger was entitled to a Washington Office voice." Lawrence Cook, as Division Chief, sat on the Superintendent Selection Committee of the period.

In the late 1950's the Service made an attempt to create a sixth Regional Office in St. Louis, Missouri, even to the extent of appointing a Regional Director, John S. McLaughlin. The Department, however, would not formally approve and in the words of Howard Baker, "the idea died before it was born."

The "six" Regional Directors, L to R:

Howard Baker, Region II, Omaha, Nebraska; Elbert Cox, Region I,

Richmond, Virginia; Lawrence Merriam, Region IV, San Francisco,

California; Minor Tillotson, Region III, Santa Fe, New Mexico; John

McLaughlin; Daniel J. Tobin, Region V, Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania.

The December 1961 organization restructured to five Assistant Directors: Administration; Conservation, Interpretation and Use (Operations); Public Affairs; Resource Planning; and Design & Construction (see chart #26). One might note that for all the years that Thomas Vint was a major force within the Service it was not until one month before he retired in 1961 that Design & Construction was upgraded to an Assistant Directorship and was then subsequently filled by A. Clark Stratton, a manager, not a Design and Planning professional.

There were personal relationship problems with this organization; the Lands Division moved back under Operations rather than Administration and Safety moved back under Administration rather than Operations -- both for conflict reasons. Additionally, the Assistant Director, Public Affairs, was not particularly pleased with what he supervised based on his perception of his skills and talents. Resolution of this quasi-problem did not occur for four years and the subsequent reorganization.

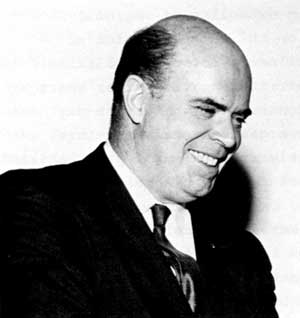

Johannes E. N. Jensen. |

1964 saw the beginning of the Hartzog Directorate, organizationally and Systematically a period of change and expansion (see charts #27, #28, #29, #30, & #31). In his nine years as Director there were seven changes to the organization -- the Associate Directors' title changed to Deputy Director, there were Associate Directors and Assistant Directors, there was a period of two Deputy Directors and at one point in time there were three Deputy Directors and everyone's title was "Director of." The external history program was established. National Capital Parks, headed by Russell Dickenson as General Superintendent, reported to an Office of National Capital and Urban Affairs headed by Theodor Swem in the Washington Office for a short period of time. Personnel and Programming & Budget reported directly to the Director. It was not until Mr. Hartzog was replaced in December of 1972 that the organization returned to a more staid traditional structure.

It would be wrong to say that the organizations under Director Hartzog did not work -- they did. However, they were a good reflection of his management style and his use of people. As one reviews the charts and tracks the people, it is evident that the organizations were oriented around people who could keep pace with the Director's mind and stamina. Mr. Hartzog's organizations are a good example of titles that meant nothing to the people. Take, for example, Johannes Jensen who came into the Service (recruited by Hartzog) as Chief of the Construction Division, then Assistant Director Design and Construction, then Associate Director, Planning and Development, then Associate Director, Professional Services, and finally, as Assistant Director, Service Center Operations (Denver); yet through most of the Hartzog years was a key advisor to the Director. Harthon "Spud" Bill was a sole Deputy Director, shared responsibility with one other Deputy Director, and before he retired shared responsibility with two other Deputy Directors; yet during the entire period he occupied the "traditional" number two's office with direct access to the Director. Administration fluctuated between an Office and an Associate Directorship and, rather interestingly, at any given point in time there were no more than two career National Park Service employees in positions of responsibility within the administrative organization. Hartzog went outside the organization for his administrative types. The external historic preservation programs and the scientific programs took on a "life" of their own. Law enforce ment became a visible entity (see chart #31) headed by professional U.S. Park Police officers, some of whom would subsequently go on to become Chiefs of the Park Police, all this in response to several riot or near riot incidents in the early 1970's.

With the appointment of Ronald Walker, a non-park professional, via the external political process as Director, the Service returned to a well structured more formal organization (see chart #33). There was an expansion of Regional Offices from seven to nine based on the administration's (President Richard M. Nixon's) philosophy of decentralizing decision making to regional cities. During the Walker years the Deputy Director (Russell Dickenson) ran the day-to-day operations of the Service and the organizational structure tended to be a combination of highly structured "republicanized" thinking coupled with National Park Service pragmatism.

Gary Everhardt's organization of May 1976 once again moved the budget process from administration to reporting directly to the Director; Training became a separate division; the Advisory Council for Historic Preservation became an independent agency; and there was a clear distinction between in-house history and archeology and the external historical and archeological programs (see chart #34). The emphasis or prominence of Alaska became apparent with the establishment of an Assistant to the Director, Alaska. The use of "Assistants to" over the years emphasized a program s importance for a period of time; i.e., Arthur Demaray as an "Assistant to" which then became a functional area, William Briggle as an "Assistant to" for the Centennial Celebration which then disappeared, and also an "Assistant to" for Alaska which would in December of 1980 become a Regional Director. Both Everhardt's and Whalen's organizations could be characterized by large numbers of Offices reporting to the Director.

The major organizational change under Whalen was created by the establishment of a separate Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service which combined the National Park Service's s external Historic Preservation programs with Interior's Bureau of Outdoor Recreation. The Bureau of Outdoor Recreation (BOR) in its establishment in the early 1960's had also been an off-shoot of the Service. The new bureau was to be short-lived, however, and all of its functions were returned to the Service and are reflected in the organization of June 1981.

Of all the Directors, Everhardt and Whalen could probably be best described as becoming more technology-oriented. Where Everhardt came from a strong engineering and maintenance background Whalen came from an educational counseling background (his first National Park Service job was as a guidance counselor in the Job Corps program). He (Whalen) was a use-oriented Director with an emphasis on urban-type social programs. Both were young men without a well established external or internal political base from which to draw upon, both tinkered little with the organization, and both dealt with selected individuals of like mind for advice (Everhardt had William Briggle; Whalen had Richard Curry). Walker, Everhardt, and Whalen were Directors of short term compared to their predecessors. There were many single interest external influences on the rise; thus, the politics of being Director left little time for developing organizations that "set a course" or that expressed to a large degree the individuality or personality of a Director.

When Mr. Dickenson became Director it was his prediliction to stabilize the Service. As a former Deputy Director, Regional Director, and Washington Office employee he was interested in conciliation and compromise with a strong emphasis on decentralized management and operations. His organizations were based on a single Deputy Director, then two Deputy Directors (one a non-park professional and also a political appointee) and finally a single Deputy (the non-park professional). His organization was strongly influenced by economics and saw consolidation of like functions under fewer management levels (see charts #37 & #38).

In May 1985, William Penn Mott became the twelfth Director of the National Park Service. Although a professional park manager Mr. Mott's career was not with the Service. Although it is too soon to make judgments or predictions, there is some indication there will be a blurring of the classifications preservation or use-oriented. There is some indication that he will be use-oriented in the urban or population density areas and preservation oriented as it relates to the traditional or one-of-a-kind ecosystem parks.

It is somewhat apparent that Director Mott will take a high profile approach to the Directorship. The energy and enthusiasm shown to date might well be construed as a kinship with Mather, Albright, and Hartzog. The press appears to feel that he (Mr. Mott) may be willing to confront hatever problems the system might have and be willing to make unpopular decisions. His imprint on the organization is, however, yet to be seen.

The process of developing an organizational structure has become over the last 15 years a cumbersome process. A formal organizational change takes a minimum of three months, some have taken a year or more and some are never formally approved. Several organizations that actually functioned fall into this category (charts #30 & #31).

Organizations are not necessarily developed solely for program needs. One should realize that many times organizations are developed around personalities and personal relationships. For example, where the establishment of the Associate Director position in the October 1956 organization can be viewed as an organizational need related to Director Wirth's implementation of Mission 66, the creation of an organization with three Deputy Directors in 1971 does not have a programmatic basis. The differences between the two organizations are clear examples of organizational/personal need as perceived by the Director of the moment. Due to style and background one appears as an organizational need, the other a personality based need. This is not to say that one or the other organization is not good, but rather to point out that those at the head are the change agents and that organizations are developed around program needs and/or personalities, that organizations do reflect the background, personality, and style of the Director and that Directors establish organizations which in their minds are the best ways to accomplish the business of the Service.

The final two charts (#39 & #40) trace the organizational development of the administrative function from its Chief Clerk roots in 1919, and the Ranger, Naturalist, and Historian park related functions from their 1925 base in the Education (Natural History) Branch under Ansel Hall. Perhaps these two depictions show more about the growth of the Service from a simple organization to a complex organization of interdependent, interrelated subsystems of the whole than any of the organizational charts.

The final two charts (#39 & #40) trace the organizational development of the administrative function from its Chief Clerk roots in 1919, and the Ranger, Naturalist, and Historian park related functions from their 1925 base in the Education (Natural History) Branch under Ansel Hall. Perhaps these two depictions show more about the growth of the Service from a simple organization to a complex organization of interdependent, interrelated subsystems of the whole than any of the organizational charts.

These charts attempt to follow two segments of the organization from their inception during the early years. Administration which dates back to the first Chief Clerk and Resource Management & Interpretation which dates to the Education Branch established in 1925. If one actually follows the "time line" one can see more about what has philosophically happened within the organization. Such a review may lend credence to the statement "every thing changes, yet nothing is changed." If one follows from 1925 it is possible to watch the ebb and flow of the organization as forestry (ranger activities) and history spin off, go their own way for a period of time, history and natural history combine for another period of time, and see in 1985 that ranger activi ties and interpretation are combined in Visitor Services, and history and museums are separate under their own Associate Director. The Administrative chart shows total organizational growth in terms of support services needed--from a Chief Clerk who did everything to today's organization where the major functions have become highly technical specialities from budget formulation to budget execution, procurement to property manage ment to personnel management, et. al.

Last Updated: 13-Dec-1999

olsen/adhi-b.htm