|

OLYMPIC

The Evolution and Diversification of Native Land Use Systems on the Olympic Peninsula A Research Design |

|

Chapter 6

LATE PLEISTOCENE, EARLY AND MID-HOLOCENE LAND USE SYSTEMS

by Randall Schalk

Introduction

The archaeology of western Washington prior to 3,000 is an enigma. Most of the archaeological literature pertaining to this interval presents a characterization that is largely negative—a list of what is typically not found. There are, in fact, few correspondences between the archaeology of these earlier periods and that of the late prehistory (3000 B.P.-200 B.P.). The tendency has been to attribute much of this lack of correspondence to differential preservation of the archaeological record. Differential preservation is always a relevant consideration when comparing portions of the archaeological record that are widely separated in time. Nonetheless, this factor probably has been greatly overemphasized relative to a number of other factors that appear to contribute to the vague character of knowledge about the early time ranges of this area. Some of the factors that are noteworthy include:

1) There has been a lack of standardized terminology for referring to the archaeological remains assumed to be late Pleistocene and early Holocene in age. Terms that have been applied to archaeological manifestations that predate 3,000 B.P. include "Early Hunters" (Bryan 1957), "Lithic" (Osborne 1956; Tuohy and Bryan 1959:46), "Early Period" (Cressman et al. 1960; Kidd 1964), "Old Cordilleran" (Butler 1960), "Early Lithic" (Mitchell 1971; Fladmark 1982), "Archaic" (Carlson 1954; Bryan 1955), "Trans-Cascadian" (Bryan 1957; Tuohy and Bryan 1959), and "Paleo-Indian" (D. Rice 1987). A term that has gained most widespread (if informal) usage in recent years, however, has been "Olcott" or "Olcott Phase". [1] The archaeological phenomena referred to by all of these terms are also vaguely defined.

2) Much of the literature pertaining to this time period dwells mainly on projectile points and pays little attention to assemblage content, assemblage variability, or site structure. This approach can obscure important variability because it assumes that temporal patterns of morphological variability in one or a few "diagnostic" artifacts is a reliable way of measuring culture change. This, of course, is consistent with the cultural historian's view of culture as a cluster of traits.

3) There have been few concerted efforts to systematically investigate sites of this age. Most of the archaeological manifestations assignable to this time period have either been casually investigated (e.g. the Olcott Site; Kidd 1964) or were encountered incidentally in the context of excavating other sorts of deposits (e.g. Cattle Point, Marymoor, Manis sites etc.; King 1950; Greengo and Huston 1970; Gustafson et al. 1979). A large proportion of these sites occur as surface remains or shallow, unstratified deposits and archaeologists have traditionally not viewed these as valuable sources of archaeological information. Consequently, archaeologists have not developed analytical strategies for dealing with a record that does not present itself as nicely stratified deposits or middens.

4) Temporal control over assemblages believed to be older than 3,000 B.P. is exceptionally poor. Few opportunities for either absolute or relative dating have availed themselves and, in this instance, differential preservation of the record appears to have some relevance. Organic material suitable for radiocarbon dating is typically lacking and in the exceptional cases where datable organic remains are present, archaeologists have either questioned the reliability of the dates obtained (e.g. Greengo and Houston 1970) or have not submitted samples for assay due to doubts about their purity (e.g. Stilson and Chatters 1981). Bioturbation is typically cited as the basis for questioning the association of organic material with the archaeological assemblages. Other dating techniques, such as the use of volcanic tephras for relative age estimates, have been largely limited to the interior Northwest (but see Gustafson 1980:29; Bergland 1984a:45).

5) Faunal data are virtually nonexistent for archaeological sites older than 3,000 years old in western Washington. Acidic soils that are not conducive to bone preservation characterize this area. Although the non-acidic sediments in archaeological shellmiddens tend to be excellent for bone preservation, the oldest dated shellmidden deposit in western Washington is less than 3,000 years old. There are large areas of the region where faunal remains are rarely a component of the archaeological record regardless of age. The Manis Mastodon site near Sequim, Washington stands out as exceptional for its unusual preservation of fauna, a fact attributable to water-saturation around a spring.

6) In the absence of adequate chronological control over archaeological patterning, there has been a tendency to accomodate the archaeological record to the traditional Holocene paleoenvironmental sequence. In particular, it has been assumed that there is a correspondence between undated lithic assemblages and the "Hypsithermal" or "Altithermal" and, in so doing, to assign these remains to an age range of ca 8,000 to 4,000 B.P. There are accumulating paleoenvironmental data indicating that the traditional model of Holocene environments that has been widely applied across the Northwest must be revised for northwestern Washington (see Chapter 5). The accomodation of archaeological manifestations to an inaccurate paleoenvironmental model is, therefore, another potential source of confusion in interpreting the archaeological record.

7) Another and by no means unimportant factor contributing to the scarcity of archaeological information about the earlier time levels of western Washington is that the scale of archaeological activity has not been great. In the absence of numerous, extensive and intensive cultural resource management studies as have occurred in the Columbia Basin, the quality and quantity of archaeological data is relatively poor. For instance, there have been no large scale surveys or data recovery projects in western Washington in which representative archaeological samples from sites of widely varied function and ages have been recovered. Most of the existing information comes from a handful of single site investigations, often of very limited scope.

8) Still another but far from insignificant characteristic of archaeological knowledge for western Washington is that archaeological visibility conditions are so difficult due to density of vegetation. Cultural resource surveys of rather large land areas have with surprising frequency failed to locate even a single prehistoric cultural resource. The forests of the Olympic Peninsula are notoriously dense (Wesson 1984) and archaeological survey procedures here have produced minimal new information about the regional archaeological record.

In the face of these deficiencies in knowledge, it is apparent why the regional archaeological record and particularly its earlier range is so difficult to characterize. It is also evident why the most definitive archaeological statements were written in the early 1960s (Butler 1961; Kidd 1964). The fact that so little new light has been shed on this whole time period over the intervening years suggests one of two possibilities. The first was mentioned at the beginning of this chapter which is that the earlier periods are lost in the fog of distant time due to the inherently poor quality of the archaeological record. Advocates of this view maintain that we just have to do more of the same—diligently seek to improve the "culture history", and wait for the discovery of well-preserved, stratified sites. The premise of the second viewpoint is that lack of progress in understanding the earlier time ranges of the Northwest archaeological record can be attributed to the absence of explicit land use models. This perspective maintains that "behavior is adapted with regard not to the site but rather to the region" (Gamble 1986:62). The approach advocated here involves the treatment of the region as the unit of analysis and it focuses on comparisons between regions in terms of the spatio-temporal structure of energy resources they contain. In later sections of this chapter, theoretical models of regional land use systems in the early and mid-Holocene are developed. Before proceeding, however, a brief outline of the chronological framework used is necessary.

A Chronological Framework

The approach taken in the pages to follow and in the later chapters will be to discuss this long interval in terms of two general stages:

Paleo-Indian (> 10,000 yr B.P.)BR> Old Cordilleran (10,000-3,000 yr B.P.),

Early Cordilleran (10,000-6,000 yr B.P.)

Late Cordilleran (6,000-3,000 yr B.P.)

This division is partially based upon the limited archaeological evidence available from the Olympic Peninsula and western Washington. More basic considerations, however, are the environmental changes that are postulated to have major effects on the nature of animal food resources. The estimated closure of the forests around 6,000 B.P. in northwestern Washington offers a reasonable temporal division for splitting the Old Cordilleran into Early and Late substages. The termination of the Late Cordilleran is not as easily linked to major environmental changes and the rationale for its temporal placement is the existence of some archaeological evidence suggesting increased usage of marine resources and a new settlement pattern at about this time.

Usage of the term "Old Cordilleran Culture" is avoided to eliminate those anthropological connotations of the word "culture" that are not easily justified (Carlson 1962; Daugherty 1962; Gruhn 1962; Osborne 1963). For similar reasons, the "phase concept" is avoided as well. The term Old Cordilleran is retained, however, because it was one of the earliest terms specifically applied to the manifestations of interest here and because it will later be argued that mountains played a pivotal role in the early Holocene land use strategies. As used here, the term Old Cordilleran refers to a general kind of land use system that is postulated to have existed over broad areas of the Northwest during the early Holocene. It is further proposed that, depending upon the region, this system persisted up to between 5,000 and 3,000 yr B.P. at which time it was replaced by a rather different land use system type. This later form of land use system was basically similar to that practiced by the native cultures of the Northwest in the historic period.

Lacking much basic information, the Paleo-Indian stage and the two stages of the Cordilleran and their associated age ranges are by necessity entirely provisional. They will simply provide a framework for describing what is known about assemblage variability, age, settlement and subsistence for these earlier portions of the archaeological record. These discussions then provide the background for the presentation of a model of Old Cordilleran land use strategies.

Archaeology of the Late Pleistocene

Probably the best candidates for the earliest evidence of human occupation in the Northwest are the isolated finds of classic Paleo-Indian projectile point types. The occasional finding of Clovis fluted points as well as Plainview and Scottsbluff points in the Northwest was first reported by Osborne (1956). As of 1956, individual Clovis points had been found in the Black Hills area west of Olympia, the Chehalis River Valley also west of Olympia, and near Dallesport, Washington (Osborne 1956). Since 1956, finds of Clovis fluted points have been reported for Ebey's Prairie on Whidbey Island, Beverly, Washington, and near Maple Valley, Washington. The latter location, about 25 mi southeast of Seattle, is the most recent fluted point find-spot and is interesting because it is the second such artifact that has been uncovered during peat mining operations at the Maple Valley bog. Although no bones have been unearthed in the bog, it is perhaps noteworthy that Clovis points have been found in locations that are so often associated with elephants. Even though there is no well documented association of Clovis points and elephant remains in the Northwest, this association is recurrent in broad areas of North America. Of the numerous Clovis sites dated elsewhere in North America, all tend to cluster tightly between 11,000-12,000 B.P. (West 1983).

There is not as yet a single well documented archaeological site in the Northwest that has been securely dated to be older than 11,000. In each of the sites for which there are radiocarbon dates in excess of 11,000, there are substantial problems with the purported association of the dated materials with cultural remains. The lower strata at Wilson Butte Cave in southern Idaho, for example, were dated at 14,500 ± 500 and 15,000 ± 800 yr B.P. but these dates were on bone; more importantly they were on rodent bone (Haynes 1974:379). In addition, the dated materials were a composite of bones collected over a broad horizontal area and the quantity of cultural material enclosed in the dated sediments was so low that it is entirely possible that some mixing process (e.g. bioturbation) was responsible for bringing these materials down from superimposed deposits (Haynes 1974).

In the case of Fort Rock Cave, located in south-central Oregon, a date of 13,200 ± 750 yr B.P. is questionable because there are mixed associations in the lowest stratum (West 1983). At Wildcat Canyon on the Columbia River east of The Dalles, Oregon a date of 10,600 ± 200 B.P. now appears to have been associated with natural strata and not with cultural features (Dumond and Minor 1983:128) as was originally suggested (Cole 1967:22).

The Manis mastodon site near Sequim, Washington has been described as the "first direct evidence for association of early man with mastodons anywhere north of Mexico and the earliest evidence of man in Washington (Gustafson et al. 1979:157)." Two radiocarbon dates associated with the deposits containing the elephant provide an age estimate of ca. 12,000 yr B.P. (12,000 ± 310 B.P. and 11,850 ± 60; Gustafson et al. 1979). Given the widespread occurrence of Clovis sites in this relatively narrow time frame, the dates associated with this site are most intriguing. If the Manis elephant was killed or butchered by humans, there is good reason to believe that those humans should have been carrying a Clovis toolkit. However, there is no evidence from this site to substantiate this expectation and, on the contrary, the only purported tools associated with the elephant are a "bone projectile point" embedded in a rib and a flaked cobble spall (Gustafson et al. 1979). The question of whether there is a definite human association with the Manis elephant hinges largely upon these objects but some archaeologists are inclined to interpret the pointed bone as the result of a natural injury rather than deliberate human manufacture (c.f. Fladmark 1982:106). Healing had taken place around the "bone projectile point" for three or four months (Gustafson et al. 1979:158), suggesting that the animal's death was due to unrelated causes—probably old age. Although the cobble spall is not the sort of tool one would expect to have been "curated" by humans but rather is of a form that typically would be expediently manufactured from materials immediately at hand and then discarded on-site, no evidence of core or associated debitage is reported. [2]

The investigators argue for a human association on the grounds that the rotated and heavily crushed skull can not be explained by any known natural cause (Gustafson et al. 1979:161). [3] While there are cultural materials of undoubted cultural derivation in more recent "Olcott" deposits at this site, the association between elephant and man is more controversial. If the Manis mastodon was in fact butchered by humans, the liklihood that the animal died of causes other than wounds inflicted by humans raises interesting questions about the possible role of scavenging in late Pleistocene subsistence systems. Is it possible that winter season scavenging of carcasses of winter-killed ungulates might have been a component of late Pleistocene and early Holocene adaptations in the Northwest? Some interesting questions are raised by the Manis finds and these may be resolved when more detailed descriptions of the archaeological remains, purported artifacts, and analytical results are available.

To summarize what is known about Paleo-Indian occupation of the Northwest, it was suggested that all purported associations of cultural material with radiocarbon dates that are older than 11,000 B.P. are problematic. Another salient point is that no actual concentrations of archaeological material—i.e. "sites"—have been identified to date that can be assigned to this interval. With the possible exception of Maple Valley Peat Bog where at least two Clovis projectile points were found in different areas of the same bog, all of the Clovis point finds have been isolated finds. Most of these points were probably lost by hunters and as yet there are no known habitation sites. Importantly, the stratigraphic context of the isolated specimens has not been well documented in a single instance although the Maple Valley bog points appear to have derived from below a layer of Mazama ash. Of possible significance too is the fact that fluted points are not found beneath archaeological strata of early Holocene age—a fact which tends to support the view that Paleo-Indian land use systems had little in common with those of the early Holocene.

The climate was considerably cooler and drier than today (see Chapter 4) and there was a Rancholabrean fauna present in this region during this period that included mastodon, bison, and caribou (Gustafson et al. 1979). Based upon the total absence of evidence of either extinct fauna or classic Paleo-Indian fluted point types from the Northwest Coast north of the Gulf of Georgia (Fladmark 1983:106), however, it would appear that northwest Washington may have been on the northern margin of those adaptations that were oriented towards the hunting of large game species that went extinct at the close of the Pleistocene.

Another candidate for being a late Pleistocene archaeological manifestation is the so-called "Pasika Complex" or pebble-tool industries (Borden 1968; Grabert 1979). These materials, comprised largely of unifacially flaked cobbles or cores, have been reported from high river terraces on the Fraser Canyon and in the Bellingham area of Washington. Except for one 5240 ± 100 yr B.P. radiocarbon date rejected by Borden, these finds are undated and the age estimates in excess of 9-10,000 yr B.P. rest largely on geological interpretations. At present the significance of this archaeological complex is unclear. The nature of use-wear on the "pebble-tools" has not been discussed and this is critical to distinguishing whether they are in fact tools or instead simply cobble cores as have been found in early Holocene and mid-Holocene assemblages from western Washington (e.g. Taylor and Schalk 1988).

Rectangular stemmed projectile points also have been reported throughout the Northwest from what appear to be either terminal Pleistocene or initial Holocene contexts. Osborne (1956:43), for example, noted

chipped, large, lanceolate and leaf-shaped points with square-cut base are not uncommon in Puget Sound and northwestern Washington generally. They are usually from the older horizons and usually of basalt.

On the Lower Snake River of eastern Washington, assemblages containing large stemmed points estimated to be between 8,000 and 10-11,000 years old have been assigned to the "Lind Coulee Phase" (Nelson 1969:22; Browman and Munsell 1969) and the "Windust phase" (Leonhardy and Rice 1970; Rice 1972). While only a few assemblages containing these points have been radiocarbon dated, age estimates range from the 8,000 B.P. dates at Lind Coulee (Daugherty 1956) to 10,600 B.P. dates at Hatwai near Lewiston, Idaho (Ames and Marshall 1981).

Although the tendency has been to assume that the stemmed forms are older than the unstemmed leaf-shaped points in eastern Washington, the latter are found in low frequencies with the former (Bryan 1980:103). Stemmed points of comparable form are periodically found west of the Cascades too (e.g. Dancy 1968:Figure 9-1; Minor 1984). Both the stemmed and unstemmed lanceolate point forms have been recovered in the Cascade foothills from the surface of a site on Cedar Lake that has yielded a date of 8,500 yr B.P. from a buried feature (Taylor and Schalk 1988). The rectangular stemmed and "Windust" point forms, unlike the fluted forms, seem to occur in some of the same places on the landscape as the assemblages containing leaf-shaped points. There may well be significant differences in the ages of these two lanceolate forms but in the absence of any other known differences in their associated artifact assemblages, subsistence, or settlement, both are considered technological components in the Old Cordilleran land use system in this study.

The Early Holocene and the Old Cordilleran

One of the patterns that began to emerge in Northwest archaeology by the late 1950's was that there were distinctive types of stone tools that were consistently found in stratigraphically early Holocene contexts. In particular, leaf-shaped or lanceolate-shaped projectile points were found in a number of clearly older sites in the Northwest (e.g. Fort Rock Cave, Cougar Mountain Cave, Five-Mile Rapids, Hat Creek, Indian Well). In a study that focused on the distribution of these projectile points, Butler (1961) first made the case that there was a pattern of region-wide significance. Butler (1961) coined the term "Old Cordilleran Culture" to distinguish "an unspecialized hunting and gathering culture" that once existed throughout the Northwest. Old Cordilleran was derived from MacNeish's "Cordilleran tradition" (Butler 1961:67)—a term for early Holocene industries that had been identified along the western mountain systems of North and South America.

In describing the same materials which he referred to as the "Early Period", Kidd (1964) expanded the discussion to include a set of criteria including variables of site location, artifact presence and absence. He described early period sites as being located ...

"some distance from the present shore of the Sound or Straits, and from major river valleys, generally on terraces cut by secondary streams, often 100 feet or more above present sea level, and generally on or near soils of the Everett or Lynden series (Kidd 1964:26)."

Kidd also characterized the assemblages from these sites in western Washington as lacking organic artifacts or debris (e.g. shell, bone, antler, charcoal), features such as hearths or house remains, and ground stone artifacts. On the positive side, the assemblages included large choppers, scrapers, thick leaf-shaped bifaces, and a predominance of coarse, non-cryptocrystalline lithic materials, especially basalt and argillite, that often have a thick weathering rind (Kidd 1964:26). [4]

In the following sections, lithic assemblages, faunal assemblages, site structure, settlement patterns, age, and subsistence orientation are discussed and these are then followed by a model of Old Cordilleran settlement and subsistence.

Lithic Assemblages

Even the most casual reading of literature pertaining to Old Cordilleran leads to two primary impressions: 1) intersite assemblage variability is very limited, and 2) there is little temporally distributed variability in them. The questions that naturally arise out of such impressions are obvious: Were Old Cordilleran toolkits monotonously uniform and simple regardless of season and at all locations on the landscape? Does the Old Cordilleran represent a 4-7000 year interval of cultural stasis? These are important questions that, while they seem obvious in many ways, have not been directly addressed in regional research. The discussion of assemblage variability here, while it may provide no answers to these questions, attempts to bring them into focus.

In his study of the distribution of bi-pointed or leaf-shaped projectile points throughout the Northwest, Butler (1961) argued that these points occurred in a number of early Holocene deposits. He further argued that these points, which he named "Cascade points", were produced by an "unspecialized hunting-gathering culture" that was the "basal culture in the area" (1961:63) throughout the Northwest Butler summarizes the artifact assemblages of this early period as follows:

Other than the highly diagnostic Cascade points (which were apparently made on prismatic blades struck from a large, conical core) the Old Cordilleran Culture is generally represented in the archaeological record by a relatively simple, basic assemblage of chopping, cutting, and scraping implements of chipped stone (Butler 1961:64).

As noted earlier, projectile points have been the focus of nearly all discussions of Old Cordilleran assemblages. Projectile points are apparently the most abundant formal tool type occurring in these assemblages. Despite the overwhelming attention to this one tool form, projectile points not been the subject of systematic studies of morphological variability. There is definitely substantial variability under the broad rubric of leaf-shaped points. Although the majority of specimens are stemless "bipoints" or willow-leafs, some exhibit hafting elements in the form of sloping shoulders.

Among the willow-leaf forms, there is a wide range of variation in overall size, cross-section, length-to-width ratios, and the presence or absence of serration. The "Cascade point" is the only form that is named and it is characterized as being slender (high length-to-width ratio), having cross sections that are lenticular to diamond-shaped, and in many instances being serrated (Butler 1961:28). Nelson (1969:18-23) provides a detailed definition of the Cascade point type and argues that they appear between 7500 and 8000 B.P. Columbia Plateau—2-3,000 after leaf-shaped projectile points were present. A general tendency for overall reduction in point size through time has been suggested (Butler 1961:54). The fact that individual assemblages often seem to exhibit a degree of uniformity in terms of size, cross-section, and presence or absence of serration seems to imply functional variability or temporal changes in form.

Other lithics characteristic of Old Cordilleran assemblages of western Washington include flaked cobbles identified either as choppers or as cores, large scrapers (which may also be cores), side scrapers crescentic in outline, end scrapers, scraper planes, ovate bifaces (Kidd 1964). When it is recognized that several of these "tools" are potentially either cores or roughouts in a manufacturing trajectory, it is readily evident that the lithic assemblage diversity is rather low. [5] Beyond these observations, there has been minimal attention to intersite assemblage variability within the Old Cordilleran. Subjective impressions suggest that some significant differences of this nature will be identified when such comparative studies are done. For example, edge-ground cobbles are a common artifact form in early Holocene lithic assemblages but these seem to be abundant in some assemblages (e.g. the Quilcene site; Munsell 1971) but rare in others (e.g. Cedar Lake; Taylor and Schalk 1988).

Lithic raw materials in Old Cordilleran assemblages from western Washington are dominated by basalt although a variety of cherts occur in the Columbia Plateau and obsidian in southeastern Oregon. According to Butler (1961), the basalts in Puget Sound Old Cordilleran assemblages are from intrusive dikes in the granitic bedrock in Puget Lowland. This material weathers with a silver or grey patina and some specimens are so heavily weathered that flake scars become obscured.

Aside from the variations in projectile point forms, Old Cordilleran lithic assemblages have generally been considered to be highly homogeneous over broad areas but this is based mostly upon impressions rather than systematic comparisons of Old Cordilleran collections from sites of different ages or environmental setting.

In general, discussions of Old Cordilleran lithic technology have not gone beyond chipped stone. A greatly neglected domain of lithic studies concerns the use of stone in cooking and heating activities. There may be, for example, important differences in the technology of cooking and food processing between the early and late Holocene (Schalk and Meatte 1988). The fracture patterns of thermally-altered rocks in early Holocene archaeological deposits seem quite different from those commonly occurring in late prehistoric contexts. One important factor in this distinction seems to be the greater importance of stone-boiling in many late prehistoric archaeological contexts. Unfortunately, few archaeologists have recognized the importance of treating cooking stones analytically and affording these remains even a fraction of the attention that is given to the chipped stone component of a lithic assemblage.

Subsistence Systems

There are no reported faunal assemblages in western Washington that are clearly associated with an Old Cordilleran artifact assemblage and, lacking botanical remains as well, there is virtually no direct evidence for subsistence. A possible exception comes from the Cattle Point Site on southern San Juan Island where faunal materials were found associated with a chipped stone tool assemblage containing leaf-shaped projectile points (King 1950). Interpretations of Old Cordilleran subsistence systems are diametrically different some archaeologists imagine economies with full-blown dependence upon riverine and marine resources at even this early time level (Fladmark 1975; 1979; Carlson 1960, 1979; Dancy 1968). A somewhat earlier view, however, has been that Old Cordilleran subsistence systems were oriented towards the exploitation of terrestrial resources (Bryan 1957:7; Tuohy and Bryan 1959; Butler 1961; Kidd 1964;). This interpretation arises to a large extent from artifact assemblages that appear to contain mainly hunting-related tools. Marine and riverine resources are not considered to have been of great importance:

The basic economy appears to have been relatively flexible but was essentially oriented toward the hunting of land mammals, particularly deer. Certain riverine resources, such as fish and mussels, were exploited to a small degree....Extensive use of fish does not appear to have become a universal phenomenon in the culture; indeed, depending upon the nature of the local ecology, the economy of the Old Cordilleran Culture remained essentially land-oriented for a considerable length of time (Butler 1961:66).

It has also been suggested that a progression towards more littoral orientation through time may be indicated (Butler 1961).

In summary, the earliest occupation of the Puget Lowland, which may have taken place as early as 11,000 to 12,000 years ago, was probably somewhat inland from the Puget Littoral. Progressive encroachment of heavy forest growth on the upland area may have gradually led to the settlement of the Puget littoral, including the offshore islands, around 7,000 to 8,000 years ago. Presumably some adaptation to the ecology of the littoral region was made, but the basic orientation of unspecialized hunting-gathering remained for a considerable period of time afterward (Butler 1961:59).

Admitting the apparent importance of salmon at Five-Mile Rapids at The Dalles on the Columbia river, Butler (1961:58) argues that no such importance was attached to salmon in Puget Sound in these early periods. A small number of salmon bones along with remains of deer, elk, seal, sturgeon, eulachon, and shellfish have also been found in deposits at the Glenrose Cannery site in the Fraser River delta region that are dated to be at least 5,700 years old (Matson 1976). In general, however, neither the artifact assemblages nor the scanty faunal record from other regions can counter the general interpretation that use of fish or marine resources was of limited importance compared to terrestrial resource dependence.

Settlement Patterns

There have been no attempts to characterize the Old Cordilleran settlement systems and there have been no large scale archaeological surveys in western Washington that have generated sizable bodies of settlement data relevant to this time period. Given the unobtrusive character of these sites and the typical density of vegetation, one would suspect that many of these sites have been overlooked during routine cultural resource surveys. There are, however, some empirical generalizations that have been offered regarding site locational patterning that are worthy of mention.

Kidd (1964:26) summarized Olcott (Old Cordilleran) site locational patterns as being...

...some distance from the present shore of the Sound or Straits, and from major river valleys, generally on terraces cut by secondary streams, often 100 feet or more above present sea level, and generally on or near soils of the Everett or Lyndon series.

There are at least two explanations for the occurrence of Old Cordilleran sites on higher terraces. The most common one is at least implicit in Kidd's (1964) discussion of these sites and that is that they were simply occupied when the rivers were flowing at higher levels. A second explanation for this pattern is that the river cobbles occurring on these terraces were sources of raw material for stone tools and that these sites are lithic "workshops" (Dancy 1968:65). Another explanation will be presented in the Old Cordilleran land use model presented below.

The suggestion that Old Cordilleran sites are located at some distance from saltwater and on secondary tributaries has been challenged on the grounds that there are exceptions (e.g. Dancy 1968:64). Without arguing that these sites are exclusively located off of saltwater and major rivers, it does seem clear they are commonly found in places where later sites do not occur. Instead of the generalization that Old Cordilleran sites are located on old river terraces, it may be more accurate to suggest that they do not occur on landforms that are demonstrably less than 3000 years old. This negative evidence may be the strongest available at present for arguing the age of these sites.

A final observation regarding Old Cordilleran settlement patterning is that intermittently there have been suggestions that the initially occupied areas were along the flanks of the Cascade Range and that there was a spreading westward and eastward from this center. Butler (1961:63), for example, states that

"The earliest manifestations of the Old Cordilleran Culture are apparently to be found along the Cascade Range, from the Puget Lowland to the northern Great Basin, an area where it also appears to have persisted for the longest time (Butler 1961:63)."

A similar pattern was suggested by Swanson (1962) for the east side of the Cascade Range and others (e.g. M. Smith 1956; Burley 1979) have made similar arguments. The empirical basis for these historical interpretations is not clear, especially in the absence of well dated assemblages. In some cases, a cultural historical model is the basis for these suggestions. However, the same pattern is consistent with ecological models that postulate a trajectory of increasing dependence upon anadromous fish and marine resources.

Age of the Cordilleran

In Butler's original formulation of the "Old Cordilleran Culture", he suggested that it was "contemporaneous with such Early Lithic traditions as Clovis, Folsom, Scottsbluff, etc..." (Butler 1961:70) and began as early as 12,000 B.P. in other areas of the Northwest. According to Butler (1961:634), this "culture" subsequently spread into the Puget Lowland at about 7-8,000 B.P. (Butler 1061:634). He did not provide estimates for the duration of the Old Cordilleran Culture in the Puget Lowlands.

There has been a general tendency to equate the beginning of the Old Cordilleran with the Hypsithermal (e.g. Nelson 1969:21). Heusser's (1960) early pollen studies placed the Hypsithermal between ca. 8,500 and 3,000 B.P. There are several sites in the Puget Sound region that have yielded "Olcott-like" artifact forms but with associations suggestive of late Holocene age. These sites include Cattle Point on southern San Juan Island (King 1950), Marymoor on the Sammamish River (Greengo and Houston 1970), Old Man House and the Manette site on the Kitsap Peninsula (Smith 1950) [6], Cornet Bay and Rosario Beach on Whidbey Island (Bryan 1957). All of these sites have produced assemblages containing leaf-shaped projectile points but in association with materials that are generally not found in other Old Cordilleran assemblages. These assemblages are interesting in that all are overlain by deposits (late prehistoric) that are less than 3,000 years old. The only radiocarbon date from these "Olcott-like" assemblages comes from the Marymoor site where a date of 2500 ± 150 B.P. was obtained (Greengo and Houston 1971). This date is generally considered invalid due to an inversion of the two dates available from the site. In any case, it seems clear that an estimate of ca 3,000 B.P. for the termination of the Old Cordilleran land use system is not contradicted by any existing information but admittedly is made without the benefit of absolute dating.

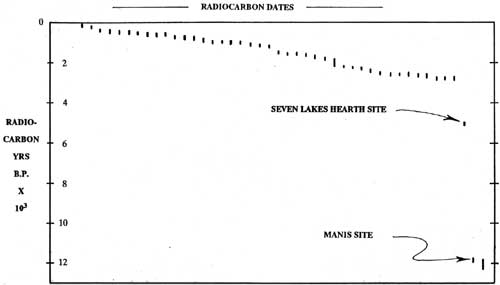

Radiocarbon dates available for Olympic Peninsula archaeological sites are illustrated in Figure 6.1. Except for two dates at ca. 12,000 B.P. which have a controversial association with cultural remains, there is only one radiocarbon date that falls within the entire archaeological sequence prior to 3,000 B.P. After 2,700, dates (nearly all from shellmidden deposits) are rather continuously distributed. A single radiocarbon date from the Seven Lakes Hearth site in the upper Soleduck Basin was obtained from a hearth associated with basalt debitage and a bone fragment (Bergland 1984a:45). There are several other late Pleistocene and early Holocene radiocarbon dates from the Manis Site (Petersen et al 1983) but their relationship to cultural stratigraphy has not been reported to date.

|

| Figure 6.1 Temporal Distribution of Radiocarbon Dates from Olympic Peninsula Sites. |

The pattern indicated in Figure 6.1 largely duplicates the radiocarbon age estimate distribution for the Gulf of Georgia (c.f. Mitchell 1971:Figure 17). If all radiocarbon dates for western Washington were assembled and portrayed in this way, the same basic result would undoubtedly be shown. These points dramatically demonstrate the potential value of advancements in chronological control especially for the earlier portions of the regional archaeological record.

Discussion

Throughout the preceding sections, a number of characteristics of the Old Cordilleran have been identified. One of the more vexing qualities about the archaeological record of this interval is that it is sufficiently different from the late prehistoric record that traditional data collection procedures are not very effective. The prospect that remedies for this problem can be obtained through just "doing more archaeology" are not promising. There has often been a tendency to complain about the incompleteness of the Old Cordilleran data base, but a more important weakness has been the failure to develop testable models of these systems that can guide data collection. There have been no explicit models of Old Cordilleran settlement or subsistence systems and regional archaeologists have been overly reluctant to develop any. To deal with this theoretical vaccuum, a model of Old Cordilleran land use is proposed below.

Old Cordilleran Settlement Systems: Foraging vs.

Collecting

Probably the most fundamental question that can be asked about Old Cordilleran land use strategies is "Were they foragers or collectors?" Admitting considerable diversity within the general system type, a collector system was universal to the aboriginal people of the region's ethnographic record. But was this basic type of system present from the beginning or did it evolve over the millenia? If it evolved, why, how and when did this take place? These are the kinds of questions that the present modeling effort attempts to address.

Binford's (1980) forager-collector model, which has been applied in numerous recent archaeological studies (e.g. Thomas 1983), maintains that there are global patterns in resource structuring such that foraging systems are generally limited to low latitude settings. Using a very large sample of ethnographically documented hunter-gatherers from around the world, Binford (1980) argues that the highest degrees of mobility occur in tropical environments and that most of the sedentary and semisedentary societies are located in the temperate and boreal zones. He relates these patterns to resource structural properties—especially spatial and temporal incongruity. As spatial incongruity of critical resources increases, a logistic mode of procurement is favored. As temporal incongruity in critical resources increases, food storage is favored (Binford 1980:15). In general, Binford (1980:15) maintains that there will be "a reduction in residential mobility and an increase in storage dependence as the length of the growing season decreases."

Relying on the arguments summarized above, Aikens, Ames, and Sanger (1986) have recently suggested that the collector strategy is characteristic of temperate and higher latitude hunter-gatherers. In their view a collector strategy is obligatory in environmental settings with marked seasonality such as the Northwest Coast of North America:

We suggest that the socioeconomic similarities between the widely separated cultures ...[of the temperate zone] ...arise firstly and fundamentally from the need for hunter-gatherers in all of these regions to depend on storage to some degree. This need is enforced simply by the natural seasonality in biotic productivity that dominates middle and higher latitudes. The natural rhythm requires that at least some resources must be intensively exploited in order to produce stores, and it controls not only the timing of group activity, but also the stability of social aggregations. Groups operating in these regions must be "collectors" sensu Binford (1980) (Emphasis added).

Contrary to the position taken by Aikens et al., the model presented here argues that the collector system is not obligatory to the Northwest Coast environment, it was not characteristic of much of the regional archaeological record, and did not appear until relatively late in the prehistoric sequence.

A major problem with the assertion that a collector system was always present is that organisms can exploit the same environment with different strategies. The distributional structure of food resources in an ecosystem is not entirely predictable from gross global patterns in seasonality and climate because there is not a single set of resources. What a cultural system recognizes as "resources" is at least partially determined by demographic variables (and perhaps other factors) and is by no means inherent to an environmental setting. At different population densities, there are different demands placed on the potential resources in an ecosystem.

The annual season(s) of low productivity are of particular importance in modeling hunter-gatherer subsistence systems. It is during seasons of low production that natural selection may be expected to exert its strongest influence on an adaptation. This is the season when food shortages can result in hunger, reduced fecundity due to nutritional stress, and outright death by starvation. In environments that have marked seasons of low production such as the northern temperate, subartic, and arctic zones, there are two basic subsistence strategies available for surviving the lean season. Hunter-gatherers can subsist by exploiting those resources that are available during the winter for immediate consumption. In the temperate zone, these resources tend to be mainly terrestrial game resources, especially large ungulates. Hunting of these large herbivores can provide sustenance through the winter and early spring seasons when edible plant foods and anadromous fish resources are not available for immediate consumption.

The second strategy for survival is one in which resources procured in abundance during the seasons of high production are stored for delayed consumption during the yearly productive lows. Food storage provides a cultural mechanism for gaining a degree of independence from natural production cycles and is the principal distinguishing feature between foragers and collectors. Adoption of a systematic storage strategy represents a major evolutionary threshold in terms of hunter-gatherer subsistence systems (Schalk 1977:231). Given the presence of temporally and spatially aggregated food resources, delayed consumption of food resources offers a means of significantly raising the carrying capacity for humans in the ecosystem. With food storage, carrying capacity is established not by the abundance of the those resources available during the season of low productivity but instead by the supply of resources that can be preserved for delayed consumption.

In other words, foraging and collecting can be alternative options in an environment characterized by marked seasonal fluctuations in food abundance: It is important to recognize, however, that a collector system is not a viable alternative in those ecosystems that lack one or more seasonally available resources that are highly localized and sufficiently abundant to be suitable as a storage resource no matter how much climatic seasonality may exist. The most dramatic examples of this point come from those regions of the Boreal Forest of North America which lacked salmon resources. Even though climatic seasonality in these settings is extreme, groups such as the Cree and Algonquin were basicly foragers that practiced highly mobile hunting strategies without food storage (e.g. Rogers 1969). These ethnographic examples demonstrate that forager systems based upon winter hunting and lacking food storage can and did exist in highly seasonal environments.

It is postulated that Old Cordilleran land use strategies were basically of the forager type. They did not involve significant dependence upon food storage and mobility was largely residential rather than logistic. The hunting of large mammals, especially deer and elk, was important throughout the year but the dominant strategy during the winter. Hunting was greatly emphasized compared to the more recent cultures of this region for two important reasons:

1) the carrying capacity for large ungulates was considerably higher due to open forest and milder winter climates prior to 6,000 B.P.;

2) human population density was substantially lower. At low density, hunting of game as an overwintering strategy is not only a viable but actually a preferable option to food storage. This point will be expanded upon below.

During the spring, summer, and fall months a wide variety of resources would have been exploited in a generalized way. Subsistence is expected to include a much broader range of resources and a general dispersion over a broad area. Use of anadromous fish and marine resources was at most only for immediate consumption, and therefore, required no mass harvest technology. Warmer and drier climate than today's combined with open forest conditions in the early Holocene would mean that edible plant foods would have been relatively abundant In addition, in-season consumption of salmon and at least limited use of certain marine resources are likely to have occurred during these warmer seasons. Hunting of large ungulates, though much reduced from winter levels, would still provide a portion of the spring-through-fall diet. Hunting of large game in the summer season would include use of subalpine meadows and perhaps lowland areas as well. [7] Lessened dependence upon game during the warmer months would potentially reduce the demands for cooperative labor in hunting and in turn reduce the optimal group size. Bands may have broken into small groups of one or a few families that exploited different areas during these seasons.

At least implicitly, many Northwest archaeologists are unwilling to believe that hunter gatherers would practice anything but a collector strategy unless the major storage resources of the ethnographic record had somehow not achieved full productivity. It is assumed that the opportunity to adopt a winter sedentary lifestyle based on the storage of large quantities of salmon would have been seized at the first opportunity. This is exactly opposite to the viewpoint argued here which is that a high degree of mobility in the context of a foraging strategy was the "normal" condition for most temperate zone hunter-gatherers. A collector strategy is not inherently superior to a foraging strategy but rather solves different adaptive problems. Food storage in combination with mass harvest/processing technology is essential to the collector type system. A collector strategy based upon food storage, much like agriculture, can be both costly and risky.

The costs of food storage in this environment are quite high and have been described in some detail elsewhere (Schalk 1977:231-237). Due to the high precipitation and humidity as well as the mild winter season temperatures, effective storage of fish through dessication or through freezing is impractical. Saturation of fish flesh and oils with the phenols in wood smoke (Schalk 1984) was essential to effective storage of oily fish like salmon. To effectively store salmon in this environment for winter consumption requires technology for mass harvest, appropriate structures for smoking the fish, containers and sheltered space for storing it, and large inputs of human labor spanning the entire interval from the time the fish are caught until eaten months later.

There are also risks involved in dependence upon stored foods to survive productive lows. Poor runs or even run failures occur naturally and, even if very infrequent, would have necessitated fall-back strategies. Perhaps a greater risk though is the potential that fish successfully stored may not be successfully consumed. Spoilage, loss to predators and scavengers and even loss to other human groups are some of the more obvious sources for this kind of risk.

Many other factors relating to cost could be identified although these are difficult to quantify in an archaeological context. General evolutionary theory would lead to the expectation that more complex systems are in some sense more "expensive" to maintain and, in the case of complex agricultural systems, require significantly greater inputs of human labor (Athens 1977). As suggested in Chapter 2, food storage implies increased complexity of an economic system relative to those systems that lack storage. On a more practical level, low residential mobility usually implies sanitation problems and vermin that plague more sedentary people. Since dead-and-down firewood is the least-cost source of fuel for cooking and heating, low residential mobility can bring with it the necessity of going ever greater distances from a residential base or even the felling of living trees. Still other advantages to mobility could be listed but these examples should be sufficient to make the case that presumptions about the superiority of sedentary land use systems may be unnecessarily ethnocentric. The appropriate question is not so much what environmental changes allowed regional populations to become heavily dependent upon marine resources and food storage, but what pushed them to it.

Rest-Rotation Foraging: The Advantages of High

Mobility

The benefits to a high degree of mobility for hunter-gatherers are counterintuitive. There are nonetheless some sound ecological principles that offer insights into why semi-sedentary and sedentary collector systems were not always present on the Northwest Coast.

One of the strongest arguments supporting a view of the Old Cordilleran as foraging systems comes from Optimal Foraging Theory. According to the "marginal value theorem", daily subsistence activity progressively depletes the resources in a given area so that there is a decline in the "net return rate" of energy (Charnov 1973; Smith 1983; Winterhalder 1977). Depletion of resources results in higher search costs because prey become more difficult to locate. At some point, the rising costs of obtaining prey in the surrounding area of declining resources outweigh the travel costs to a new foraging area with higher resource densities. At this point the "optimal forager" is expected to move to the new area.

Translated into terminology relevant to the Olympic Peninsula, Old Cordilleran local groups are expected to make residential moves when resource yields in an area are low compared to other areas. As long as the resources in those other areas were not already being exploited by another band, there would be greater efficiency in moving than in continuing to reduce resources in one area. Since deer and elk are likely to have been the critical winter resources, residential movements are expected to have occurred whenever hunting returns dropped to a point where the costs of making a residential move to another valley or a different area within the same valley would be less than continuing to hunt for fewer animals in the area of the occupied residential camp.

In a lightly populated region, as the Olympic Peninsula is assumed to have been during the early Holocene, the marginal value theorem predicts that hunter-gatherer bands would range over broad areas—probably many times greater than the home ranges of the ethnographic tribes of the Peninsula. Depending upon how successfully animals were taken in a given valley, a band might not return to the same area for a number of years, allowing the depleted herds to build back up to maximum numbers.

A different way of looking at the same strategy, is referred to as "rest rotation grazing" in the field of range management (Hormay and Talbot 1961) and the same principles have been applied in wildlife management (DeByle 1979). The basic concept of rest-rotation grazing is that there is an equilibrium between an ungulate population and the plants it consumes.

The system is interactive: rate of increase of herbivores is influenced by the density of edible vegetation, and rate of increase of those plants is determined largely by the density of animals eating them (Caughley 1979:4).

There are actually two different equilibria that can be identified (ibid:5). "Ecological carrying capacity" is defined as the the equilibria which the plants and animals reach without any harvest (or other interference) by humans. "Economic carrying capacity" is the equilibria achieved when maximum sustained yield is practiced. The former equilibria implies a larger standing crop of animals, but since plant resources are suppressed, the rate of increase in the herbivores is less than under the second type of equilibria.

Translating again into terms relevant to the subject of interest, we can consider the most effective strategy for harvesting deer and elk by foragers operating in a lightly populated region like the Olympic Peninsula. Achieving maximum sustained yield and economic carrying capacity would not be relevant to hunters that could continually move to new areas where there were large herds at ecological carrying capacity. Hunting of herds followed by several years of no harvest would allow the vegetation to recover and herds to rebuild back to ecological carrying capacity. Again the advantages to high mobility are that relatively continuous residential movements provide access to prey resources at maximum density.

The regular rotation of hunting territories for the Old Cordilleran would require high degrees of residential mobility, limited use of logistic mobility, and all of the other characteristics associated with the forager system type. The distribution of residential camps should be closely linked to ungulate ranges during winter season occupations. In other words, winter ranges of deer and elk should be areas of concentration for Old Cordilleran sites. In Chapter 3 (Figure 33), modern winter ranges of elk on the Olympic Peninsula are illustrated. Areas of particular game concentration are those portions of the river valleys immediately below the winter snowline. These areas are those used by migratory animals that exploit the mountains and the high meadows during the summer season. The concentration of animals in this "foothill" zone on the flanks of the mountains would be relatively high in winter compared to the lowland areas that are exploited year around by resident game (Schalk and Mierendorf 1984:24-34). In addition, the natural physiographic features in the foothills would tend to concentrate animals in their foraging and movements thereby increasing the effectiveness of hunting them. These are the areas through which animals move between their summer and winter ranges and where humans can intercept biomass that is produced over a much broader area. [8] By virtue of migration between summer and winter ranges, these animals are unearned from the viewpoint of predation that is focused on the winter ranges.

There is a second sense in which exploitation of migratory ungulates on their winter ranges might be considered an unearned resource. Ungulate mortalities due to various natural causes can be quite high during the winter season. A scavenging component to a human subsistence strategy could greatly enhance the security of hunter gatherer subsistence during the difficult winter season (c.f. Gamble 1987).

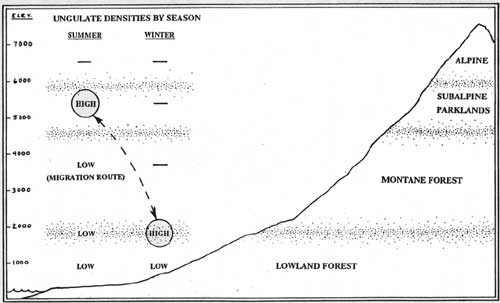

Figure 6.2 shows schematically the relative density of ungulates by season along an elevational gradient of the Olympic Peninsula. To the extent that ungulate density was a primary consideration in Old Cordilleran hunting strategies, the focus of procurement would have been on winter ranges and summer ranges. However, the temporal coincidence of winter season production lows in virtually all other food resources with the winter yarding of migratory ungulates would have made this season of critical importance.

|

| Figure 6.2 Relative ungulate densities by season along an elevational gradient of the Olympic Peninsula. (click on image for a PDF version) |

If Old Cordilleran land use systems were as dependent upon the winter hunting of ungulates as postulated in the preceding arguments, there is a nutritional problem that arises. Speth and Spielmann (1983) have identified the nature of this nutritional problem and its consequences for hunter gatherers. For people whose winter subsistence involved a primary dependence upon the hunting of ungulates, late winter and early spring are particularly stressful seasons (Speth and Spielmann 1983). This is the season when food of any kind can be scarce but also when ungulates tend to be in poor condition and fat-depleted. There are nutritional inadequacies associated with a diet consisting largely of lean meat—the condition known as "rabbit starvation" (Stefansson 1944). A high protein diet results in a substantial elevation of the metabolic rate at the season of the year when food is scarcest. Lacking the energy present in carbohydrates and fats, the body must use protein as an energy source and it does this inefficiently. Besides the very large daily food requirement on a totally lean meat diet, the use of amino acids in protein to satisfy energy needs prevents the replacement of the proteins in the body. Fatty acid deficiency can also result under these circumstances. When fat and carbohydrate in the diet are increased, they serve to reduce the loss of body proteins—what is referred to as "protein-sparing" (Speth and Spielmann 1983).

Based upon these dietary considerations, Speth and Spielmann (1983:18) suggest that hunter gatherers faced with seasonal dependence upon lean meat "will concentrate on subsistence strategies that increase the availability of carbohydrate and/or fat at the critical time of the year." They predict preferential use of animals that have high fat content and/or storage of foods that are rich in carbohydrates or fat.

Although the precise mechanisms may not have been fully understood, the general importance of fats and carbohydrates in the diets of Northwest Indians has been recognized for several decades (see Rivera 1949). Historically, there were significant differences in the relative importance of carbohydrates and fats from one region of the Northwest Coast to another. Carbohydrate-rich root resources were of greatest importance in areas with extensive prairies (e.g. southern Puget Sound) while fats were more important in the wet coastal areas (northern coast of British Columbia). A degree of variation in the relative importance of roots versus animal fats also clearly existed between the Indian tribes of the Olympic Peninsula during the 19th century. If forests were more open during the early Holocene, root resources may have been more abundant than after forest closure beginning around 6,000 yrs B.P. This would imply a trend of greater dependence upon animal fats to solve the protein dynamics problem after about 6,000 yrs B.P. Following this line of reasoning, those marine resources rich in fat and available during the critical late winter/early spring months should have been the first marine resources exploited by humans. These might include herring, certain sea mammals, smelt, and waterfowl that were available during the interval of about January through April.

Culture Change and the Old Cordilleran

Major environmental changes occurred during the roughly 7,000 year interval that has been included within the Old Cordilleran here. The most profound change in terms of its probable impact upon regional hunter-gatherers was the closing of the forest that began around 6,000 B.P. This change would have greatly reduced the carrying capacity for large ungulates in the region and also would have suppressed the availability of edible plant resources. An overall reduction in the productivity of terrestrial ecosystems would have necessitated increasing reliance upon anadromous fish and certain marine resources.

This environmental change would have the same effect as increased population without environmental change—the ratio of population to resources would be increased in both cases. The possibility that human population was growing must be considered as well. Given a diet in which meat was very important and also a high degree of residential mobility, a rather slow rate of population increase would be most likely. Whatever the relative contribution of ecosystem changes and human population growth, it is clear that the closure of the forest after 6,000 B.P. would have substantially reduced ungulate populations. Any imbalance in the population/ungulate resource ratio is likely to have been catalytic in shifting Old Cordilleran land use systems in the direction of greater reliance upon fish and marine resources.

Since the winter season productive lows would still constitute the major "bottlenecks" for survival, any activity that would increase the number of animals available during the winter months would be strongly beneficial. Reduced use of ungulates during the spring through fall months would conserve animals for harvest during the critical winter months. Due to what were probably dramatic reductions in game abundance due to forest closure, winter season mobility may have greatly increased. Coverage of significantly larger areas may have been necessitated and the frequency of residential moves would have increased due to the smaller ungulate herds on the winter ranges. Still another change anticipated in the Late Cordilleran would be the initiation of controlled use of fire to maintain seral vegetation or prairies. This cultural practice would have the effect of counteracting the climatically induced vegetational changes on a limited scale. It is postulated here that deliberate burning and the origin of "prairies" on the Olympic Peninsula and in western Washington probably originated at the time that closure of the forest began around 6,000 B.P. These prairies would amount to "patches" of productivity in an increasingly food scarce forest the likely result of patchier resource distributions would be a tendency toward greater dependence upon logistic patterns of resource exploitation.

In sum, it is postulated that the basic forager system persisted after forest closure and perhaps as late as 3,000 B.P. but with certain changes. The main changes postulated include increased use of fish and littoral resources in the spring-summer-fall months for immediate consumption, increased residential mobility especially during the winter, and the initiation of controlled burning to promote early vegetation stages. Expanded use of oil-rich resources in the late winter and early spring is also predicted and these might include herring, sea mammals, waterfowl, and smelt. A similar expansion in the use of any available carbohydrate-rich root resources is also expectable.

Summary

There is virtually nothing that has been written about the interval before 3,000 that has not been disputed by Northwest archaeologists. This condition is symptomatic of the theoretical vaccuum that has been endemic to so much of the archaeology of western Washington. In this chapter, a model of Old Cordilleran land use systems has been proposed. It is argued that these systems were basicly of the forager type; they were characterized by high residential mobility, minimal dependence on food storage, and limited use of logistic procurement strategies. Winter season subsistence centered upon the hunting of large game, probably deer and elk mainly. The winter ranges of those ungulates that migrated to higher elevations in the summer time would have been of particular importance for winter season hunting due to the high densities of game at these locations. These areas are distributed around the flanks or foothills of the Olympic Mountains in the river valleys immediately below the winter snowline at about the 2500 ft elevation. The term Old Cordilleran seems particularly appropriate because it emphasizes the importance of mountains in the foraging strategy as it is hypothesized here. Use of the term Old Cordilleran is premised on the association of these important hunting areas with mountain flanks.

Subsistence during the summer season is clearly more conjectural than it is for winter season. Food quest activities during this season would probably have been focused upon terrestrial plant and animal resources. Those ungulate populations that migrated into the subalpine meadows would have offered attractive, high-return resources because they are not only available at this season in high relative abundance but they occur in a setting in which animal movement has a high degree of predictability. Rugged terrain and limited water sources would make hunting in the subalpine zone rather efficient relative to other settings. In view of the protein metabolism problem for humans eating a meat-rich diet, it is likely that carbohydrate-yielding plant resources would have figured in the diet of those who subsisted in the mountains in the summer.

Based upon the paleoenvironmental model discussed in Chapter 5, early (10,000-6,000 B.P.) and late stages (6,000-3,000 B.P.) of the Old Cordilleran are proposed. It is argued that forest closure around 6,000 B.P. would have reduced the carrying capacity for both game and the hunter-gatherers who depended upon them. If the reduction in resource productivity of the terrestrial environment after 6,000 B.P. did not result in temporary abandonment of the Olympic Peninsula or a reduction in human populations occupying the area, it would have necessitated adaptive responses such as increased use of fish and marine resources during the summer and controlled burning of forests to maintain areas of seral vegetation. These changes amounted to variations within a foraging type of land use system. The emergence of collector systems facilitated by the initiation of systematic food storage is proposed to have occurred as much as 3,000 years after forest closure. The transition from foraging to collecting land use systems is discussed in the next chapter.

ENDNOTES

1The Olcott site (455N14) was a key site in Butler's scheme and, for many archaeologists, has informally achieved "type site" status in referencing lithic assemblages containing leaf-shaped projectile points.

2Aikens (1983:134) makes a point about other purportedly early archaeological sites in North America that may have relevance to this stone specimen at the Manis site:

Specimens from other sites, such as Calico Hills and Texas Street, again in southern California, are demonstrably of Pleistocene age but do not exhibit the patterns of consistent form and flaking technique that have been characteristic of human artifacts since earliest times in the Old World. Moreover, in each case it is clear that a small number of specimens fortuitously resembling artifacts were carefully selected from deposits containing hundreds or thousands of pieces of bone or bone broken or abraded by geological forces....

3This would qualify as an "argument from want of evident alternatives" (Binford 1981:83-8). It is a form of argument that has been much abused by archaeological faunal analysts, especially in the context of arguing for a human agency in deposits of unusual age and questionable derivation (see Binford 1981:84).

4In a study of nine Olcott sites in the Mossyrock Reservoir of southwestern Washington, Dancy (1968) disagreed with most of Kidd's criteria for distinguishing the Early Period. A major contention of Dancy's is that the Olcott site and the other early sites from Snohomish County were not habitation sites but "workshops". Dancy maintains that projectile points are the only finished tools found on these sites and that the other items Kidd identifies as tools are actually byproducts of the projectile point manufacturing process.

Dancy interprets the absence of bone, shell, or organic debris to be a result of the poor preservation associated with sediments characteristic of the river terraces—well-drained, sandy silt. The absence of evidence for houses or hearths Dancy dismisses on the grounds that there had been no extensive excavations of such sites as of 1968. In short, it is Dancy's conclusion that Kidd's criteria are only relevant to Early Period "workshops" and that actual "definition of an 'Early Period' for western Washington would seem premature (1969:67)."

5Butler notes that the Olcott site has quarry-like appearance but due to the absence of a raw material in the vicinity of the site, concludes that "roughed-out cores, nodules, and blanks may have been brought to the site (1961:48)."

6A portion of the Manette site, located near Bremerton, Washington, was excavated in conjunction with condominium developments in 1982 (Jermann 1983). A second area of this site was subsequently excavated for which no written report was completed. This second area yielded abundant basalt lithic remains including large lanceolate bifaces and other specimens that are considered characteristic of early Holocene assemblages. The Manette site collection is now curated at the Suquamish Tribal Museum.

7Hunting of ungulates in lowland areas, especially by small groups of hunters using encounter hunting techniques presents special challenges. In particular, overall animal densities in these settings tend to be seasonally constant and relatively low due to their usage by non-migratory herds. Added to this is the fact that low relief areas offer a much lower degree of predictability in day to day animal movements. There is one circumstance under which this problem of predictability would be greatly diminished—during cold intervals in the winter when lowland areas were snow-covered. At such times, it would be relatively easy to track ungulates and if the snow were deep enough, exceptionally easy to kill them once encountered. Of course, during climatic conditions similar to or warmer than those of today, such opportunities would be infrequent. Snow accumulation at low elevations in this region is unusual and does not occur at all during most winters.

8Mellars (1986:279-280) postulates a very similar settlement strategy for the European Upper Paleolithic:

"The major concentrations of Upper Paleolithic sites lie within the lower foothill zones, immediately adjacent to major mountain massifs that rise in each case to elevations of over 1800 m. Potentially the most significant feature of these locations lies in the patterns of animal migration.... If we assume that the main routes of animal migration in these areas would have been along an essentially upland-lowland gradient between summer and winter territories, then the sites must be seen as lying at some point astride these major migration routes and apparently closer to the winter ends of the respective seasonal ranges. One obvious advantage of these locations is that the major river valleys extending between the uplands and lowlands must have provided the principal migration paths for the animals during the major seasonal migrations, and in this respect would have channeled the movements of herds into more restricted, and to this extent, more predictable, locations. Equally if not more significant, however, is the fact that by intercepting the animals at one major point within a much more extensive pattern of seasonal movements, the human groups were in effect able to harvest the combined animal resources from the whole range of the summer and winter territories from a single settlement location (Mellars 1985:279-280).

The degree of importance that is attached by Mellars to the interception of animals along a migration route between summer and winter ranges differs from my own argument in that I see the winter ranges themselves as being of primary importance for hunting activities in the early and mid-Holocene. However, the last sentence in the above passage by Mellars draws attention to the locally unearned character of the resources and this observation is equally relevant in both cases.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

schalk/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 16-Nov-2009