|

OLYMPIC

The Evolution and Diversification of Native Land Use Systems on the Olympic Peninsula A Research Design |

|

Chapter 8

MANAGEMENT ZONES AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPECTATIONS

by Randall Schalk

Definition of Management Zones

The purpose of this chapter is twofold: to divide the region into management/research zones and present archaeological predictions for these zones. The first step will be to list the proposed zones accompanied by their major distinguishing features. In dividing up the Peninsula, it is necessary to make certain assumptions about the relative importance of various environmental features to hunter-gatherers in the past. Both paleoenvironments and human adaptations have changed in substantial ways since the time of initial human occupation of the region. These points suggest that the environmental features which we use in dividing the Peninsula into management zones should be ones that are likely to be of sufficient importance and stability to have been of significance throughout most if not all of the prehistory of this region.

Major physiographic features are strongly correlated with variations in the major classes of fish and marine food resources. These features figure importantly in segmenting the coastline of the Peninsula into useful management zones. Resource classes considered in relationship to physiographic features included salmon, sea mammals, shellfish, and sea birds. Moving inland to the lower river valleys and lowlands of the Peninsula, differences in salmon resources were also a major factor in partitioning of the river valleys. This reflects the importance that has been attached to the distribution of this resource class in determining the presence or absence of a riverine-based settlement strategy. Moving still further inland and up slope, the distribution of terrestrial resources, especially deer and elk, was emphasized in the demarcation of zonal boundaries in the Peninsula's interior. In general, then, the zonal divisions reflect the geography of human land use as this has been depicted in preceding chapters of this report.

It must also be emphasized that these zones should be considered provisional in the light of current information. They will serve no useful purpose if they are considered immutable; as new information becomes available such change might involve further subdivision of the zones presented here to accomodate different or additional environmental variables or it might require actual relocation of zonal boundaries. Such changes may be necessitated by new knowledge about the region's archaeological record or about its past environments or both. During the course of the present study, the zones were redefined more than once; the present set of zones represents a more fine-grained form of an earlier version (see Schalk 1985c).

Although the research design developed in this study is regional in scale and could be used to generate expectations about the character of archaeological variability throughout the Olympic. Peninsula, predictions are focused upon those zones that are included within the Park. A comprehensive development of predictions for the other zones of the Peninsula is beyond the scope of the present effort but may be accomplished in the future in conjunction with other studies.

The Park is divided into four major management zones with subdivisions in two of the four major zones. These zones are as follows:

I. Coastal Margina. Southern Outer Coast

b. Central Outer Coast

c. Northern Outer Coast

d. Outer Strait

e. Inner Strait

f. Hood Canal

II. River Valleys and Lowlands

a. West Slope

b. Northwestern Peninsula

c. North Slope

d. Hood Canal

e. Skokomish Valley

III. Montane

IV. Subalpine and Arctic

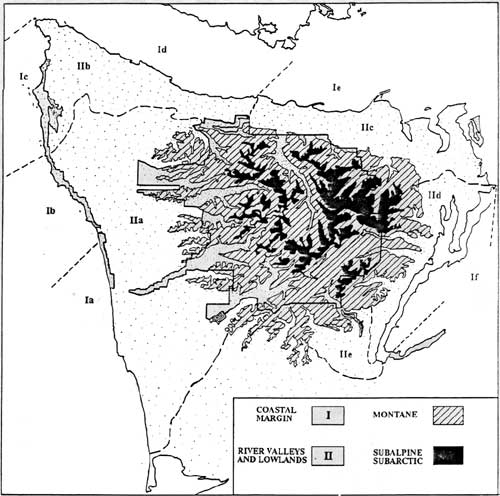

These zones are illustrated in Figure 8.1 (a large-scale version of this map is available at the Pacific Northwest Region, NPS). In the discussion below, the zonal boundaries are defined and the rationale for their placement is explained. Against this background, attention is also directed to brief summaries of currently available archaeological information for each zone encompassed within the Park. The final section under the discussion of each zone addresses the issue of future directions for archaeological research within that zone. Included here are predictions for the character of the archaeological record represented in each zone, important research domains and their associated data requirements. As in Chapter 2 and the remainder of this chapter as well, the terms residential base, location, field camp, and station follow Binford (1980:10).

|

| Figure 8.1 Proposed Archaeological Management Zones for the Olympic Peninsula Region. (click on image for a PDF version) |

I. The Coastal Margin

The coastal margin is operationally defined as 5 km wide band of land paralleling the shoreline around the Peninsula. The definition of the landward margin of this zone seems to be somewhat more arbitrary in an environmental sense than the placement of boundaries on the other zones. The use of 5 km as the inland boundary to this zone amounts to a compromise to at least two considerations. Firstly, in the densely forested landscape characteristic of much of this region, a distance of 5 km probably encompasses most of the places that would be visited on foot and returned from in a single day. Secondly, acknowledging that the sea/land interface has changed throughout the Holocene to varying degrees around the Peninsula (see Chapter 5), a distance of 5 km encompasses most areas of land in the region that are below an elevation of 30 m. Sea levels were apparently not more than 30 m above the modern sea level since the late Pleistocene. The strip of land included between high tides and 5 km inland, therefore, includes most areas that were situated directly on or adjacent to saltwater since the Late Pleistocene. Besides the narrow strip of land along the shoreline of the Peninsula, this zone also includes offshore islets and rocks. The Coastal Margin so defined includes the entire coastal strip of Olympic National Park.

The coastline of the Olympic Peninsula has about as much variability as can be encountered in a single region and this is reflected in the marked variations in the kinds of marine resources that occur in different areas of the Peninsula. The major subdivisions of the Coastal Zone were identified to accomodate this variability and these subdivisions are explained in the discussions below.

The coastal strip of Olympic National Park is by far the best known zone within the Park from an archaeological perspective. Archaeological surveys were carried out here in the 1950s (Stallard and Denman 1955) as were minor excavations at Toleak Point (Newman 1959) and White Rock Village (Guinn 1963). A more recent survey examined the coastal strip of the historic territory of the Makah as well as the river banks of the included streams (E. Friedman 1974; 1976). Relative to much of the Olympic Peninsula's interior, the obstrusiveness of typical sites along the coastal zone (especially shellmiddens), and the geologically dynamic character of this zone, facilitate site discovery.

The most numerically dominant sites recorded in the Coastal Margin zone are those referred to as "shellmiddens". Despite the obtrusiveness of shellfish remains, exploitation of these resources probably represented a relatively minor subsistence activity for the occupants of most shellmiddens. Existing historical and archaeological data make clear that sites as functionally distinct as spring fishing and/or sea mammal hunting camps, permanent winter village settlements, and bluff-top redoubts are lumped together under the generalized term "shellmidden". In fact, petroglyphs represent the only other class of aboriginal sites recorded within this zone and the only site class that typically lacks shellfish. Aside from preliminary site distributional information, most of the substantive knowledge about this zone comes from one large scale excavation project—the Ozette Project. This project is discussed further below under the discussion of Zone Ic.

Zone Ia: Grays Harbor to Cedar Creek

This zone extends from the northern end of Grays Harbor to Cedar Creek, about 5 km south of the Hoh River mouth. The distinguishing features of this zone include productive salmon rivers, a relatively straight coastline with few headlands and rocky islets, rather extensive areas of low gradient sandy beaches south of Point Grenville, and a wide continental shelf (35-50 km). In terms of food resources, this area includes 1) the mouths of two of the Peninsulas most productive salmon streams: the Quinault and the Queets; 2) sandy substrate clams in greater abundance than other outer coastal zones {especially razor clams from Point Grenville south}; 3) a scarcity of sea mammal haul outs and sea-bird rookeries; and 4) poor access to halibut banks and sea mammal migration routes along the continental shelf.

Archaeological Expectations

Only about a 17 km long strip of Olympic National Park falls within this zone. Expectations for this zone would include:

1) Sea level changes in this zone have been of low amplitude during the last 9,000 years with the lowest relative sea levels only 1-2 m below modern levels (ca. 9,250 BP) and highest levels (ca. 4500 BP) less than 10 meters above present levels (see Chapter 5). It follows that the Holocene archaeological record of this zone (and other outer coastal zones—IB and IC) should be exceptionally well preserved compared to other areas of the Northwest. If, as some have argued (Fladmark 1975; 1979), early Holocene adaptations were already heavily oriented toward marine resources, then sites containing evidence of maritime orientation should be found within this zone. On the other hand, it has been argued in this study that systematic use of marine resources in this region developed in the late Holocene. According to this model, most archaeological sites in this zone will be related to procurement of marine resources but they are expected to be less than about 3,000 years old. This model maintains that this zone is not expected to have been important in early and mid-Holocene land use systems. Contrasts between these models and their implications for the Coastal Zone of the Park were developed during the early stages of the present project (see Schalk 1985c). Distinguishing between these models rests heavily on the geological question of whether or not the known archaeological resources of the Coastal Zone are a highly biased sample of those that previously existed there.

2) Sites that are less than 3000 years old in this zone are expected to be associated with a riverine collector land use system. Since the types of systems were present historically in this area, this would imply that there have been no major (systemic) cultural changes during an interval of about three millenia. Intensification of resource exploitation may, however, be reflected in evidence for shorter resting periods between harvests (e.g. younger age structure in shellfish) or addition of previously unexploited low-return resources.

3) In view of the limited marine resources of this zone and the large rivers that empty into the ocean within it, it is expected that there would have been a riverine distribution of winter villages. Sites located on saltwater within this zone, except at large river mouths would have been used seasonally (particularly in spring-summer) by logistical task groups seeking marine resources. This would mean that archaeological sites along the coastal margin of this zone are likely to be either field camps or locations. Both of these site types are expected to lack evidence for permanent housing. Faunal assemblages should be dominated by marine resources, especially shellfish and nearshore marine fish. Artifact assemblages should be dominated by implements used in the harvest and processing of these same resources. The overall character of the faunal and lithic assemblages relative to winter village sites should be one of low diversity. Many of the faunal resources and artifact types found in residential bases should be lacking, reflecting the specialized nature of site occupation.

4) Any winter villages situated in this zone should be located at or very near the mouths of rivers, especially the larger rivers. This reflects the view that fully maritime adaptations were not present in this region of the Olympic Peninsula in prehistoric times and that riverine collectors positioned their permanent winter residences near the places where salmon were obtained in bulk for storage.

5) Site locational patterning should be strongly correlated with the distributional structure of marine resources being taken. The "location" types of sites should have a greater tendency to have faunal remains of resources that occurred in the immediate vicinity of the site. Field camps, on the other hand, are expected to contain resources from a wider range of habitat types. This would imply higher resource species diversity in discrete occupational events. Because village sites are not expected on saltwater within this zone (except at river mouths), most sites less than about 3,000 years old should be either "locations" or "field camps".

6) Reoccupation of the same locations on a cyclical basis should lead to the vertical accretion of both locations and field camps. This is the result of the stability and spatial predictability that is characteristic of many marine resources. In those cases where shellfish were being exploited, these deposits should contain well preserved vertebrate faunal remains if such resources were also being exploited. This expectation is based upon the acid neutralizing nature of mollusc shells. To the extent that most intertidal hardshell clams occur in protected coastal waters, the molluscan resources of this zone are likely to be dominated by the razor clam.

The dominance of this particular species may have interesting implications for both the locational stability of shellmidden deposits and the extent to which vertebrate faunal remains are preserved in shellmiddens. The habitat of the razor clam is best developed along straight stretches of low-relief coastline that lack inlets or embayments. These are high energy beaches and not suitable habitat for hardshell clams. Another characteristic of the razor clam is that it is unusual for the thinness of its shell and, therefore, preservation of its valves is likely to be rather poor compared to most other clams.

There are two points to be made from these observations. The shoreline distribution of these clams tends to be linear rather than patchy like that of the hardshell clam species. These different resource distributional structures imply different patterns of site formation (see Thomas 1983:69-71). The linear nature of razor clam beds along this zone is, therefore, expected to reduce the potential for vertical accretion of midden deposits at discrete locations. Instead, a more linear and horizontally diffuse process of archaeological site formation is expected. Given this process and the perishable quality of razor clam shells, archaeological deposits should be harder to detect and, when detected, are likely to have relatively poor preservation of vertebrate fauna relative to shellmiddens with high proportions of hardshell clam species.

Zone Ib: Cedar Creek to Cape Johnson

Distinguishing features of this zone also include the mouths of two productive salmon rivers, but in contrast to Zone Ia, a complex coastline with numerous headlands and rocky islets and a narrower continental shelf. The southern boundary of this zone was drawn to include Destruction Island. This particular island is unusual for its size, distance offshore, elevation, and archaeological potential. The width of the continental shelf ranges from about 20 km at the southern end of this zone to about 10 km at the northern end. This stretch of coastline has considerably higher potential than Zone Ia for hardshell clams, marine mammals, birds and offshore fishing.

Archaeological Expectations

The archaeology of this zone is expected to share many characteristics with that of Zone Ia. Greater marine resource diversity of marine resources, however, makes it somewhat transitional in character to Zones Ia and Ic.

1) This zone should have intact sites containing evidence for systematic marine resource use spanning most of the Holocene if Fladmark's "early maritime hypothesis" is correct. Another expectation associated with this hypothesis is that sea mammals will be greatly emphasized prior to 5,000 B.P. but that after this time salmon will be of considerable importance. This reflects a postulated surge in salmon production after stabilization of sea levels and stream gradients after about 5,000 B.P. According to the early maritime hypothesis, intensive shellfish use is expected to develop in conjunction with the more sedentary adaptations afforded by salmon exploitation at around 5,000 yrs B.P.

2) According to the arguments developed in Chapter 6, however, usage of this zone prior to 3,000 B.P. is expected to involve no more than casual exploitation of marine resources throughout most of the year. The coastal strip is not a location where people practicing a foraging type land use strategy based upon the hunting of ungulates are expected to be during most of the winter. Hunting efficiency during winter for the Old Cordilleran systems would favor locations where ungulates were more concentrated or where the residential bases were centered within foraging zones that had land on all sides. (Coastal settlement implies a reduction in hunting efficiency for terrestrial resources due to the reduced land area within the foraging radius of a settlement situated "with its back to the water"). This would mean that archaeological remains associated with this zone should be more recent than the estimated emergence of riverine collector systems at around 3,000 yrs B.P. The important exception to these arguments, however, has to do with the protein dynamics problem discussed in Chapter 6. The exploitation of marine resources that are oil-rich or which contain carbohydrates during seasons of low terrestrial productivity and especially late winter/early spring is likely to be the earliest form of marine resource exploitation. This means that archaeological evidence for use of marine resources before 3,000 yrs B.P. should be limited to that season of the year when fats and carbohydrates are in particularly short supply (i.e. late winter/early spring).

3) According to the models set forth in this study, archaeological sites in this zone should be dominated largely by field camps and locations that are less than 3,000 years old; due to the greater abundance of marine resources, however, there is also some potential for coastal residential bases after about 1,000 yrs B.P. The latter will be located in protected settings with good canoe launches and freshwater sources. Remains of permanent houses, winter seasonality indicators (e.g. fur seal bones), and high diversity faunal and artifact assemblages are the expected archaeological signatures of such sites. Sites located at the mouths of the major rivers entering the ocean in this zone are likely to have the longest records of winter residential use.

4) One feature that is quite distinctive about this zone relative to Zone Ia is the presence of numerous rocky islets and headlands. These are important sea mammal and marine bird rookeries. Taken together with the narrowing of the continental shelf in this zone, late prehistoric sites should contain higher frequencies of sea mammal bones, bird bones, egg shells, and offshore fish. These should occur in sites occupied mainly during the spring and summer seasons. Offshore islands with sufficiently level ground for site formation should contain faunal and artifact assemblages characteristic of field camps or location site types. For fully maritime collector systems, the usage of certain islands such as Destruction Island as stations for monitoring sea mammals over a broad area can also be expected.

Some of these same landforms, especially those capable of being easily defended, have potential for the presence of remains of fortresses or redoubts. The age of such remains is not expected to be great and this suggestion is based upon the belief that warfare on the Northwest Coast developed after the emergence of collector land use systems, especially maritime collector systems.

5) The locations for exploiting many of the marine resources available within this zone are extremely stable in their spatial distributions through long periods of time. Also, different marine resources may be available in the same location at different seasons. In addition, areas of level ground that are habitable and suitable for archaeological site formation are somewhat limited. The combined effect of these factors over long time periods will be usage of the same places as locations and field camps in the procurement of a number of different resources. An offshore island with bird rookeries, for example, might be used occasionally as a location during spring forays for birds and bird eggs, as a location (butchering site) by whale hunting parties in the early summer, as a station for monitoring sea mammal movements, as a field camp in late summer for offshore halibut fishing activities, and even as a defensive retreat during intervals of intergroup conflict. Occupations of these different types accumulating in the same place imply complex deposits. Assemblages deriving from such deposits will occur as blends that are less diverse than assemblages from winter residential sites but more diverse than a single function, special purpose field camp or location. Consequently, these deposits and their assemblages may be quite difficult to place into simple site types.

6) The intertidal zone of this management unit has potential for archaeological features such as fish traps and canoe ramps. Both of these types of features are likely to be manifested as alignments of rocks.

7) There is some potential in this zone for the occurrence of bird-netting locations. The netting of birds and waterfowl typically required a natural feature that funneled the flight patterns through defiles where a net could be strung. The most obvious examples of such features would be isthmus settings in which waterfowl fly low to the ground between two bodies of water or embayments.

8) Inland use within this zone is likely to be very thinly represented. Cultural modified cedar trees may occur where canoe-making, plank-splitting, and bark-peeling occurred. But these are likely to be the most obtrusive remains here. The perishability of much of the technology involved, curation of important non-perishable tools (e.g. adzes or axes), and the lack of repetitive use of the same locations are all factors that should contribute to an archaeological record with few material traces. When the very poor conditions for detecting archaeological remains in densely forested settings are also considered, it becomes apparent that archaeological remains situated away from present or former shorelines will be extremely rare.

Zone Ic: Cape Johnson to Cape Flattery

This zone is most salient for the unusual productivity of marine resources and its small, unproductive salmon streams. The continental shelf is quite narrow here (less than 5 km off of Cape Flattery) and this means that sea mammals that follow the shelf in their north-south migrations come much closer to the coastline than they do anywhere else on the Peninsula. Also, halibut can be taken in abundance here for similar reasons. Sea mammal haul outs occur at a number of locations within this zone. This zone is characterized by a high energy shoreline with limited potential for hardshell clam production. On the other hand, shellfish species that are adapted to high-energy, rocky beaches are relatively abundant in this zone. Streams which enter the ocean within this zone are all quite small with limited diversity and productivity of salmon runs. The Ozette River constitutes a somewhat more productive stream than others in the northwestern Peninsula due to its lacustrian rearing habitat for sockeye salmon, but relative to the Peninsula's larger rivers is still a minor salmon-producing stream.

Current Archaeological Information on the Coastal Margin Zone Ic.

Beyond the archaeological survey data mentioned above, current knowledge about the archaeology of this zone comes mainly from the intensive investigations at the Ozette site carried out by Washington State University between 1966 and 1982 (Croes 1977, 1980; E. Friedman 1974, 1976a, 1976b, 1980; J. Friedman 1975; Gleeson 1973a, 1973b, 1973c, 1974a, 1974b, 1980a, 1980b, 1982; Gleeson et al. 1976; Gleeson and Fisken 1977; Gustafson 1968; Huelsbeck 1981a, 1981b, 1983a, 1983b; Kirk and Daugherty 1978; Mauger 1975, 1978, 1980a, 1980b; Wessen 1982; and others). These investigations involved large scale block excavations of water-saturated deposits that span from the late prehistoric period through the early 20th century. The focus of research was in one area of the site (Area B) and especially on deposits estimated to have accumulated during the past four centuries. Minimal information is available on the excavations of earlier deposits at the site but it has been reported that a well developed maritime adaptation has been in existence for 2,000 years B.P. (Gleeson 1980:8; Gustafson 1968; McKenzie 1974 cited in Gleeson 1980:8) and that whales probably have been hunted for at least the past 2,000 years (Kirk and Daugherty 1978:92). A few other sites in Makah traditional territory such as Cannon Ball Island, Warmhouse (45CA204), Tatoosh Island (45CA207), and Sooes (45CA25), were tested in conjunction with the investigations at the Ozette site (E. Friedman 1974).

A collection of approximately 50,000 artifacts as well as more than a million faunal remains was recovered from Ozette (Gleeson 1980b:15; Huelsbeck 1983a:71). The scale of this project has never been equalled in western Washington and the degree of preservation of wood and fiber is quite remarkable. Because the Ozette Project is the centerpiece of all archaeological studies done to date in the Coastal Margin zone, I will attempt to identity some of the more significant contributions of the project as well as the questions for future research that it raises.

Nearly 80% of the artifacts recovered are of materials that are perishable under typical conditions in most archaeological deposits (Gleeson et al. 1976:25). This unusual circumstance was the basis for an equally unusual approach to the investigation in which "...the focus has been on studies that are ethnographic in nature although based upon archaeological materials" (Mauger 1980a:2; Gleeson 1980:1). The Ozette material is characterized (Mauger 1980:2) as "...an essentially ethnographic collection recovered from an archaeological context."

Ethnographic studies are generally synchronic and, with only minor qualifications, the Ozette archaeological investigations are synchronic in nature as well. Accordingly, the study sought to confirm observations made in ethnographic sources (Drucker 1951) and ethnohistoric accounts (Swan 1869). In some areas, such as the question of how social rank might be expressed in the spatial distribution of artifacts and debris on house floors, support was found for the ethnographic sources. For example, higher densities of wood chips (Gleeson 190b:178), fish bones (Huelsbeck 1980:55), rare shellfish (Wessen 1982:177), and ornamented artifacts. (Gleeson 1980b:177, 179) were interpreted as confirmation that the highest ranking individual in House 1 occupied the northeastern corner of the house. In regard to subsistence, minor discrepancies with ethnographic statements about relative importance of fish species were suggested from the analyses of Ozette fish faunal remains. Perhaps the most dramatic lack of correspondence between ethnographic expectations and archaeological observation at Ozette was that fur seal bones were very abundant (Huelsbeck 1981b:24). Ethnographic accounts for the Nootka represent fur seal hunting as an activity that only developed in the late 19th century as a response to the fur trade (Drucker 1951:46). Ethnohistoric accounts of the Makah apparently do not mention fur seal hunting (Huelsbeck 1981b:24).

At least eight houses were identified and three of these were excavated in their entirety (Gleeson 1980b:15). In western Washington and especially for coastal sites, the opportunity for the exposure of entire houses is relatively unique and a number of interesting patterns were identified. It was found that densities of artifacts and debris were highest in exterior midden areas between houses and lowest in central house floors. On the basis of fish species represented in the Ozette fauna (Huelsbeck 1981b:46, 60) and analyses of shellfish growth rings (Wessen 1982:142), it is suggested that some people occupied the Ozette site throughout the year. According to ethnohistoric sources (e.g. Swan 1869), Ozette (Hosett) was one of five Makah winter villages occupied during the late 19th century (Swan 1869) and the occupants of these villages shifted summer residence to two summer fishing camps.

The preservation of house structural elements made it possible to document details about house architecture (Mauger 1978). Information recovered included numerous details about technical solutions to the maintenance of houses, provision of adequate drainage in a setting with heavy precipitation, patterns of refuse disposal, and spatial distribution of materials across the floors of houses.

Potentials for Future Research Raised by the Ozette Investigations

The investigations at Ozette have raised a number of questions likely to be of relevance in future research. Certain questions must be answered before the full potentials of the Ozette data base can be realized. Some of the questions that emerge from a reading of reports and theses available at this time on the Ozette site investigations include:

1. What is the age of the Unit IV and V deposits that were the focus of the excavations at Ozette?

There is uncertainty about the age of the deposits that were the focus of the investigations (Gleeson 1980b:39). Only one radiocarbon date is available, a date of 440 ± 90 yrs BP (WSU-1778), from the Units IV and V deposits. Dendrochronological age estimates (Gleeson 1980a:81-84, 1980b:39), additional radiocarbon dates, and any other means for gaining finer temporal control are critical to placing the site assemblages into a chronological context. As Gleeson (1980b:185) points out, the Ozette data base has great potential for yielding valuable information on the nature of culture change in response to European contact. This potential can not be realized as long as assemblages that straddle the interval before and after European contact are treated as a composite assemblage. More rigorous chronological control would permit diachronic comparisons between the Ozette assemblages or between Ozette assemblages and those from other sites.

2. How does the Ozette data base fit into a regional system of settlement and land use?

This question is similar to the preceding one in that it identifies the desirability of providing better contextual perspective—in this case a spatial context in a settlement geography. To be able to make generalizations about subsistence, faunal frequencies, or artifact assemblage frequencies it is necessary to have an explicit understanding of the role this site played within an annual cycle of seasonal movements. It is, in other words, necessary to identify how this part relates to a larger whole. In efforts to characterize the overall dependence upon certain subsistence resources, there has been a tendency to assume that the patterns revealed at a single site can be extrapolated to the whole cultural system (E. Friedman 1974; Huelsbeck 1983a, Wessen 1982). For example, there is a suggestion of inconsistencies between the ethnohistoric record for the Makah and the archaeological record at Ozette in regard to relative importance of fish species exploited (Huelsbeck 1980a:52). There may be an incongruity between ethnographic observations of a system at multiple points on the landscape throughout a yearly cycle and the archaeologist's view of a system from a single place on the landscape that was probably only occupied for a part of the year. To relate and compare these two rather different kinds of observations in a reliable way will require more systematic attention to models of settlement geography and seasonal round.

Ethnohistoric accounts describe Ozette as a winter village location but there are some faunal indications of year round occupations at this site (Huelsbeck 1981b:60; Wessen 1982). For meaningful comparisons or contrasts to be made between the archaeological and ethnohistoric/ethnographic records, however, further consideration should be given to the complexity of native settlement strategies. For example, Northwest ethnographers frequently describe seasonal rounds with the qualification that certain individuals, especially the elderly and the infirm, might not follow the general pattern of the local group. If similar patterns are considered for the Ozette site, it becomes clear that the archaeological record there may be more complex than has been fully appreciated. Following the implications of this example one step further, can it be assumed that the spatial patterning of artifacts and debris on a house floor accurately reflects the social organization or subsistence pattern of all occupants through a yearly cycle or merely the individuals that happened to be using the structure immediately prior to abandonment? If, for example, the elderly individuals left behind by younger co-residents during the summer disproportionately consumed certain resources (e.g. shellfish), the residues occurring on a house floor in late summer might not be in any sense representative of consumption patterns for the entire household group. Similarly, a house abandoned (or covered by mud) in late winter is likely to have rather different food residues and spatial patterning of those residues on its floor than the same house would have if abandoned in late summer. In other words, archaeological inferences about normative subsistence activities and social class must control for season of site abandonment, age-dependent differences in seasonal subsistence, and site formation processes before patterning at one site can be related to a whole cultural system.

There is an obvious need for better information from sites representative of all components of the seasonal settlement/subsistence cycle. For the northern outer coast of the Olympic Peninsula, information from one of the sites recorded historically as a spring/summer fishing and sea mammal hunting camp would yield invaluable comparative information on functional/seasonal differences in artifact and faunal assemblages. Such data would enhance the capacity for placing the Ozette site data base into a context of regional land use systems. Preliminary efforts along these lines have been undertaken (E. Friedman 1976) but the scale of such efforts has been far too small to produce samples necessary to document frequency differences in faunal assemblages or artifact forms in a representative way.

3. What kinds of archaeological data likely to be present at Ozette should be sought if this site is reopened in the future?

Given the synchronic/ethnographic quality of the work done to date at Ozette, there has been no significant attention to deposits predating the past four centuries although deposits are present which are at least 2,000 years old (Gleeson et al. 1976:1). Despite the large scale of excavations at Ozette, it is interesting to keep in perspective the small fraction of the entire site that has been excavated. The site is described as being almost a kilometer long (Huelsbeck 1983a:1). Considering the complex occupational history that may have extended over several centuries, it is appropriate to ask how the use of one locality might relate to the much larger site. The frequency of massive mudslides at this particular portion of the site raises the possibility that this location was not the best along this stretch of shoreline for house building. What implications might this have for the representativeness of excavations at this locality?

Some of the Ozette project research objectives can only be realized when diachronic data are available. The antiquity of whale hunting, for example, was one of the research topics of the project (Gleeson 1980a:1) but to address this topic will require recovery of information from deposits earlier than those that have been reported from Ozette. The development of fur seal hunting as a component of subsistence is a subject for which similar data are required. According to Philip Drucker (1951:46), the hunting of fur seals by the Nootka was an activity that developed in response to the fur trade. The Makahs also hunted fur seal during the late 1800s (Swan 1869) but the archaeological faunal record from Ozette suggests this activity occurred in precontact times as well (Huelsbeck 1981b:24; Gustafson 1968). When this activity began and the nature of its development are questions that relate directly to the larger issue of how maritime adaptations evolved in this region. Well controlled artifact assemblages minimally spanning the past 2-3,000 years will probably be necessary to address these sorts of diachronic questions effectively.

4. What are the sources for the precontact metal artifacts at Ozette?

The occurrence of iron artifacts (blades and chisel bits) hafted in wooden handles associated with deposits estimated to be about 400 years old (Gleeson 1973a:11-12, 1974c:10, 1980b:11, 50, 52; Mauger 1974:12) is interpreted as "incontrovertible evidence" of the use of iron prior to European contact. Similarly, copper sheet metal was found in the same deposits. Japan has been identified as the most plausible source for the iron and the agent of transport the Japanese Current (Gleeson 1980b:52). Possible sources for the copper include trade from northern Northwest Coast (if native copper) or Japan via the Japanese Current (Gleeson 1982:41).

Obviously, the uncertainties surrounding the age of these deposits are an obstacle to determining the significance of these items. If these metal artifacts eventually prove to date from the late 18th century, the significance that has been attributed to them might be cast in a rather different light. In view of the apparent lack of reported evidence for a precontact iron working industry or reported occurrences of iron in other precontact sites elsewhere in the Northwest, a precontact occurrence of these tools warrants closer scrutiny. This is especially the case inasmuch as the Makah were an important node in native trade networks (Singh 1956; Gleeson and Fisken 1977:36; Croes 1977, 1980) and they apparently had substantial numbers of the metal tools (Gleeson and Fisken 1977:21, 23). Could it be that archaeologists have simply overlooked these items elsewhere? Compositional analysis of the metal artifacts in conjunction with more rigorous chronological control would seem essential to a resolution of this puzzle.

There has been no systematic study and reporting of the historic artifacts from this site. This is essential to accomplishing one of the research objectives identified during the project—the consideration of culture change from the protohistoric into the historic period (Gleeson et al. 1976:24; Gleeson 1980; Mauger 1975:21-22).

5. Social Organization and Intrasite Spatial Analysis

In view of the great anthropological interest there is in when, how, and why socially stratified cultural systems evolved on the Northwest Coast, any means for measuring social rank are of considerable importance. A central theme in the spatial analyses at the Ozette Site and especially House 1 was that social rank was expressed in the spatial distribution of artifacts and debris on the house floor. The various spatial analyses of the floor of House 1 are based upon a model of the living floor preserved in situ by a mudslide:

It is a look at the past never before possible, for no archaeological opportunity anywhere quite matches this one. The mudflow in effect stopped the clock at Ozette, leaving virtually everything preserved in place, somewhat as volcanic ash has preserved a record of everyday life in ancient Pompeii (Kirk and Daugherty 1978:94; emphasis added).

Following upon this view of the Ozette as being a Pompeii-like deposit, the distribution of artifacts and debris were envisioned as being "frozen in time" on a living floor just as they had been moments before the catastrophy occurred. Taking this model of post-depositional events one step further, the spatial analyses of artifacts and debris across the floor of House 1 were viewed as frozen manifestations of intrahouse social organization. Based upon the occurrence of high densities of certain kinds of debris across the north end of House 1, it was argued that the highest ranking individual in the house lived in this corner (e.g. Gleeson 1980a:73; Huelsbeck 1980a:55, 1981b:89-97) as is suggested in Nootkan ethnography (Drucker 1951). This area of House 1 at Ozette was characterized by high frequencies of wood chips, fish bones, and rare species of shellfish. In effect, the argument for the locus of high rank within this house is that it is the messiest area of the house with the greatest quantities of the same kinds of debris that occur in exterior midden deposits.

A particularly problematic aspect of the spatial analyses that were conducted is that they assume but do not demonstrate that the archaeological patterning they identify is the result of socially regulated human activities. Before this approach can be generalized and applied to other sites, there is an alternative model that deserves serious consideration. I am suggesting that the "Pompeii model" may not be an appropriate one for the spatial distribution of debris in portions of the Ozette deposits. The "Pompeii model" is problematic because much of the cultural debris distributed across the areas within the outline of House 1 was quite clearly deposited there by the mudslide itself. The architectural data from the Ozette site (Mauger 1978) support this interpretation and are inconsistent with the assumption of in situ preservation beneath the mudslide. These data may be summarized briefly.

Houses 1, 2, 3, and 4 were in the path of a massive mudslide which both structural and stratigraphic evidence indicate was "rapid and catastrophic" (Mauger 1978:3, 47). The slide moved downhill not merely gently covering everything in its place but instead it smashed into the houses with considerable violence. Portions of houses located uphill may have been distributed downslope where other houses stood (Mauger 1978:161). Walls were collapsed and apparently the roof of House 1 was carried onto the beach beyond the archaeological deposits (Mauger 1978:50, 144). Wooden wall support posts of House 1 were sheared off at the ground along the east wall (Mauger 1978:50, 147, 197). Some midden was "plucked up or ploughed by the slide" (Mauger 1978:47). The exterior midden deposits that had accumulated to a depth of as much as two meters or more against the house walls (Mauger 1978:74) would have been smeared across the floor of House 1. There is a high density of artifacts and debris in exterior midden relative to interior midden (Gleeson and Fisken 1977:12, 39; Wessen 1982:158; see also Mauger 1978:174, 175, 186). It may be no coincidence that the northern portion of House 1 where the effects of plowing were most pronounced is also the part of this structure which proved to have the highest densities of the debris classes that were interpreted as indicators of high rank. Where the effects of the slide were least pronounced in House 1 and where exterior midden deposits were not smeared across the house floor (Mauger 1978: 153), the densities of debris were markedly lower.

While there is no reason to suggest that all spatial patterning on the floors of the Ozette houses was produced by the mudslide itself, there can be little doubt that the "Pompeii model" ignores important evidence for significant spatial displacement of artifacts and debris during the event that produced the excellent organic preservation at Ozette. Numerous figures representing the floor of House 1 show a high density "smear" of materials that extends from east to west across the northern portion of the house floor (e.g. Gleeson 1980:Figure 18; Huelsbeck 1981b:Figures 20, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30; Mauger 1978:Figures 35, 41, 47; Wesson 1983:Figures 21, 22, 23). Before social inferences can be reliably drawn from the Ozette data—the artifact, faunal and debris distribution patterns on the house floors—it is essential that the effects of mudslide displacement be systematically examined and adequately controlled for in any spatial analyses. An explicit discussion of site formation processes would provide the foundation upon which most other analyses and interpretations could be built.

Archaeological Expectations

This zone has little to offer to people who were not fully maritime but, on the other hand, once maritime adaptations developed, the marine resource potentials of this zone were unsurpassed elsewhere in the region. The contrast between marine versus terrestrial and riverine food resource productivity is exceptionally sharp in this zone. For this reason, this zone presents an unequalled opportunity to test models for the emergence of fully maritime systems of land use. Geological conditions for site preservation throughout the Holocene should be as good here as anywhere on the Olympic Peninsula if not the entire Northwest Coast. If the paleoenvironmental data suggesting that the outer coast of the Peninsula has been rising are accurate (see Chapter 5), the absence of archaeological remains associated with early maritime land use systems can not be explained away as a preservation problem. If clear evidence for early and mid-Holocene maritime adaptations can not be found here, it will be difficult to fall back on the sea level change argument.

Some of the many expectations for this zone that flow out of discussions and models presented in previous chapters are as follows:

1) This zone is ideal for testing the "early maritime hypothesis" because, if it is valid there should be a rather well preserved record here of human use spanning much of the Holocene. If marine resources played a major role in early and mid-Holocene subsistence, then the archaeological record of this area should be rich in archaeological remains associated with these time periods. In contrast, the models developed in this study lead to the expectation that this zone will have minimal archaeological evidence predating the development of riverine collector type land use systems on the Peninsula. In fact, much of the prehistoric archaeological record here may postdate the emergence of maritime collector land use systems. Dating of the earliest remains of winter village sites in this zone should be highly informative regarding the question of how long fully maritime adaptations were present on the Olympic Peninsula.

2) This zone will be important for investigating the evolutionary relationship between the riverine and maritime collector land use strategies (see Chapter 7). If the maritime collecting system of land use developed subsequent to the riverine collector systems in this region of the Northwest Coast, there are implications for the archaeological record of this zone. It was postulated that winter-sedentary land use systems were already established along the Peninsula's larger rivers as much as 1,500-2,000 yrs before the appearance of maritime collector systems. This would imply that usage of this section of the coastal zone would have been based out of winter residential sites located outside of this zone (especially in Zone II). Site types expected to occur in this zone might include field camps and locations but not winter residential bases. In other words, there should be an absence of permanent village sites during this interval (ca. 3,000-1,500 B.P).

To the extent that late winter/early spring were always stressful periods for aboriginal subsistence systems of this region, sites associated with this season should be particularly well represented. Such sites are expected to be strongly associated with the exploitation for immediate consumption of marine resources that contain significant amounts of fat or carbohydrate. The importance of protein-sparing foods was discussed in Chapter 6 and there are a location number of marine resources that could fulfill this requirement (e.g. sea mammals, waterfowl, herring eggs, and shellfish).

3) Also assuming that the first collector systems on the Olympic Peninsula would have been centered in villages on the larger rivers in other areas of the Peninsula, there may be some archaeological evidence of usage of this zone by logistic task groups from such villages that visited this area during the summer months for specific resources. Summer season field camps are, therefore, expected to be an important archaeological site type present after the emergence of riverine collector systems in this region (estimated at around 3,000 B.P.). These sites should lack evidence for permanent houses and should be dominated by non winter season seasonality indicators.

4) After the postulated emergence of maritime collector systems in the region around 1,000 yrs B.P., winter villages should appear within this zone. These will contain remains of permanent houses, numerous winter seasonality indicators, and high diversity artifact and faunal assemblages. Evidence of heavy wood-working should be well represented reflecting the importance of house construction as well as the manufacture of large canoes for the increased logistic requirements of the fully maritime land use system.

5) Since the staple storage resources in this region were necessarily non-salmonid fishes (especially halibut), the location of winter village sites should be correlated with environmental factors other than the distribution of salmon. Protection from the weather, access to various marine resources, sources of freshwater and potential for canoe launching should be among the primary variables determining residential site locations.

6) The maritime collector system is a more complex economic system than the riverine collector system for reasons discussed in Chapter 7. This implies larger villages, larger cooperative labor groups, and more complex division of labor with more specialists of various sorts. One of the archaeological correlates to these points is that intrasite variability and intra-household variability in artifact assemblages should be greater than for riverine collectors.

7) The maritime collector system is likely to involve a greater degree of social ranking than the riverine collector system. Despite the great interest that the evolution of ranking has in Northwest Coast anthropology, the archaeological measurement of social rank presents a significant challenge. Mortuary data have most commonly served as the basis for making social inferences in other regions, but can not be expected to do so here. Investigations at the Ozette site have identified archaeological patterns suggestive of differential economic status and access to wealth objects or scarce resources. This is promising but, in general, it seems likely that until a number of more basic questions about prehistoric subsistence and land use are better understood, it will be difficult to address problems related to social organization. Also, it seems likely that questions of social organization will require far more intensive and extensive excavations than have been accomplished to date in the Northwest. Large scale efforts that encompass multiple houses and intrahouse areas may be necessary and, if diachronic or inter-regional comparisons are to be made, such excavations would have to be carried out at multiple sites as well.

8) After the appearance of maritime collector systems in the region, relatively few field camp sites will be produced. This expectation reflects the high degree of logistic mobility characteristic of these systems and the large size of their foraging zones (see Chapter 7).

9) The high degree of logistic mobility associated with the coastal collector system postulated after 1,000 yrs B.P. for this area should manifest itself in residential site faunal assemblages that include marine species from a wide variety of different habitat types that extend well beyond the immediate vicinity of the site itself. In contrast, faunal assemblages from resource procurement sites in this zone that are associated with the earlier riverine collector systems should reflect a much more spatially restricted suite of species and especially those obtained in the immediate vicinity of individual sites.

10) Although the coastline through this zone has been covered in previous archaeological surveys, these investigations have apparently not specifically attempted to identify cultural resources in the intertidal zone (Wessen 1985:30). There is reason to believe from paleoenvironmental evidence (see Chapter 5) that this particular coastline has less potential for submerged archaeological deposits than some others because it is emergent. This is, however, a model the validity of which has yet to be demonstrated. Whether or not there are remains of prehistoric occupations in the intertidal or even subtidal portions of this zone, late prehistoric rock features (e.g. fish traps, canoe ramps) are known to occur and may be found in places where attention in previous surveys has been focused only above the high tide line.

11) Expectations 4 through 8 that were presented under Zone Ib are also relevant to Coastal Zone Ic.

Zone Id: Cape Flattery to Crescent Bay

The distinctive features of this zone are that it has good access to sea mammals and offshore fisheries, a moderate energy shoreline with slightly better shellfish potential than Zone Ic. It is strategically located relative to deep water and especially the highly productive halibut banks to the northwest of Tatoosh Island. Like Zone Ic, this zone is characterized by salmon streams that are small and relatively unproductive. Large scale archaeological excavations have been undertaken over a period of several years at a complex of sites on the Hoko River (Croes and Blinman 1980; Miller 1984; Croes and Hackenberger 1988). Still in progress, this investigation, the Ozette Project, and the Manis Mastodon site represent the only intensive, multi-year site investigations that have occurred on the Olympic Peninsula. No portion of this zone is encompassed within the boundaries of Olympic National Park. Expectations for archaeological patterning in this zone, however, would be rather similar to those for Zone Ic.

Zone Ie: Crescent Bay to Mouth of Hood Canal

This is a lower energy zone with more sandy beaches and spits than Zone Id and its hardshell clam resources are, therefore, relatively productive. Rivers with good (the Elwha) to moderate (e.g. Dungeness) salmon productivity enter the Strait of Juan de Fuca within this zone. Sea-mammals, except for harbor seal, are less abundant than in Zone Id. The diversity of sea bird species is lower than in the Outer Strait and the Outer Coast zones. This zone, along with the river valley and lowlands that lie inland from it (Zone IIc), are exceptional within the Peninsula region for having low precipitation. Within the region, this area was characterized by relatively high productivity of terrestrial plant and animal resources. No portion of this zone is encompassed within Olympic National Park.

Zone If: Hood Canal

The waters of this fiord are the most protected (low energy) of any in the region and this accounts for this area's high shellfish productivity—especially of hard shell clams. In terms of sea mammals, this zone is a cul de sac with both low diversity and abundance. With one important exception (i.e. the Skokomish River), the streams of this zone have limited salmon production and small stretches of spawning habitat in their lower reaches. The archaeological record of this zone is very poorly known. Due to only very restricted areas of low relief along this side of the Peninsula, there has been very substantial historic impact on the archaeological record of this zone (e.g. highway and residential development). No portion of this zone is encompassed within Olympic National Park.

Zone II: River Valleys and Lowlands

This zone includes all areas of the Peninsula that occur between the inland boundary of the Coastal Margin (Zone I; 5 km from the mean high tide line) and the lower elevational boundary of Zone III (the 2000 ft contour interval). This zone is relatively wide along the western and northern Peninsula but quite narrow along the Hood Canal side of the Peninsula. This was an extensive and densely forested zone broken only by a limited number of small prairies and areas where disturbances such as fire temporarily created early seral stages. The entire zone is occupied year round by resident elk and deer populations and, during the winter, by migratory herds of these same animals.

There are basicly three subareas within this broad zone that are expected to be of particular importance to hunter-gatherers: the river terraces, prairies, and the areas between 1,500 and 2,000 ft elevations where winter ranges of migratory game occur. Each of these subareas warrant further comment and may eventually deserve designations as separate zones.

Most of the rivers of the Peninsula have only short reaches of low gradient in their lower portions. Even where the coastal lowlands reach their greatest width on the western Peninsula such as along the Lower Quinault, major portions of these rivers are characterized by braided channels. These channels have changed dynamically even in the past century (Wessen 1978a:13) and, therefore, are not conducive to the preservation of sediments of substantial age. Stream flows are quite variable with order-of-magnitude differences between summer and winter a typical situation. Positioning of winter villages sites, therefore, is not expected to have been within the active flood plain or where flooding was a frequent occurrence.

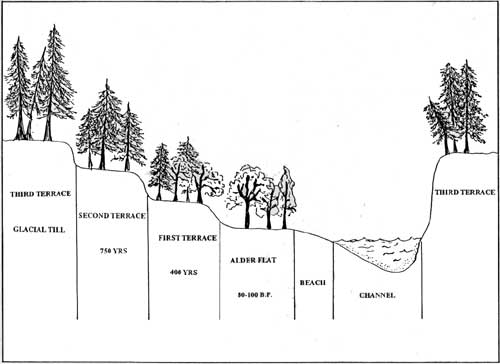

As was discussed in Chapter 5, the rivers of the Peninsula are characterized by a four terrace sequence. These terraces were formed by climatic events and consequently are of similar ages in different river valleys. In Figure 8.2 a generalized model of the terrace sequence, vegetation types, and ages is illustrated. This geological pattern in terrace formation apparently applies throughout the Peninsula and has profound importance for how archaeological survey is done as well as how the results of survey are interpreted. The river terraces are likely to be major areas in which prehistoric sites of all ages and a wide variety of types occur throughout the Peninsula. In certain zones, they are likely to be the kinds of landforms upon which residential sites will be found (especially Zone IIa, Zone IIc, and Zone IIe). An awareness of the approximate ages of these terraces is invaluable to anticipating the archaeology of this zone because the first two terraces above the modern floodplain are surprisingly recent. In fact, only the third terrace above the alder flats is old enough to have in-place archaeological remains that are greater than 750 years of age.

|

| Figure 8.2 River Terrace Ages (yrs B.P.) and Forest Succession (modified from Wessen 1978a; data from Fonda 1974). (click on image for a PDF version) |

Most of the known prairies occur within this zone and the few exceptions occur in the Coastal Zone. Although a few of the prairies are larger (e.g. Quillayute, Forks, and Sequim) most of the recorded prairies are quite small—generally less than 100 acres in extent. Most of the prairies for which detailed locational information was found occur in the western Peninsula, but there are ethnographic and historical accounts of prairies in the northeastern Peninsula as well (see Chapter 4; Gunther 1927; Onat and Larson 1984:43; L. Smith 1951).

A general expectation that applies to all of Zone II is that prairies will generally occur within the foraging radius of winter villages. Where there was a riverine collector land use strategy with villages distributed at some distance upriver as in Zones IIa and IIe, prairies are expected to broadly parallel the river valley distribution of villages. In those areas characterized exclusively by coastal villages (e.g. Zone IIb), it is expected that the distribution of prairies will not parallel river valleys but rather will be situated within about a 10 km radius of saltwater. Examination of the distributions of prairies in Figure 3.3 in this light is intriguing. The general distribution of prairies on the western Peninsula is consistent with this explanation. If the locations of other prairies can be identified, it will be interesting to see if the same relationship is maintained.

It is important to note that many prairies may have been encroached upon by forest vegetation prior to being documented by Euroamericans. This process has been documented for southern Puget Sound and the dramatic differences between prairie and forest soils may disappear quickly as the forest reclaims an area of prairie (Bryan in Tuohy and Bryan 1958:45). On the other hand, at one locality in Clallam County old growth spruce and hemlock were reported growing on what seemed to be prairie soil (Smith 1951:53). Identification of former prairie areas then constitutes an important research challenge for which there are not obvious methodological solutions presently. This is a subject of much needed research on the Olympic Peninsula and western Washington generally.

The areas between roughly 1,500 and 2,000 ft elevation comprise a third kind of setting within Zone II that is of considerable archaeological importance. These areas occur as fingers of land that extend up the river valleys well into the central portion of the Park. The concentrations of animals that occur here in winter are hypothesized to have been the mainstay of winter season subsistence for Old Cordilleran subsistence systems (see Chapter 6). The third terraces above the floodplain and other benches in these "foothill" settings are expected to be areas of high potential for early and mid-Holocene archaeological sites. Locations of particular importance will be those settings with southerly solar exposure. [1] These are settings where winter snow accumulations are reduced and, as a result, where forage availability is maintained for large herbivores. The terraces and benches along the valley walls offer two additional locational advantages for hunters—these places would tend to have commanding views of the surrounding landscape at times in the past when the forest was more open and they tend to be warm places in the winter due to cold air drainage.

At least two archaeological sites that fit this general profile have been identified in the recent past. One of these sites was found along the Elwha River during the archaeological reconnaissance associated with the present study (see Appendix A) and another is known from just outside the Park's southeastern boundary (Schalk 1985b).

Zone IIa: West Slope Rivers and Lowlands

The width of the lowland zone reaches its maximum for the Peninsula in this zone. The rivers here are relatively large and productive and supported riverine settlement patterns during the early 19th century. There are numerous prairies in this zone which were present at the time of initial Euroamerican settlement. Rainforests occur in the river valleys. It is estimated that 85% of the total elk on the Olympic Peninsula occurred in the west slope river valleys in historic times and this zone coincides with the mapped distributions of migratory elk winter ranges (Schwartz and Mitchell 1945:305).

Current Information on the Archaeology of the West Slope Rivers and Lowlands

Archaeological investigations in this zone include the exploratory efforts of Albert Reagan (1917). He provides the first descriptions of archaeological sites at inland locations. One of these sites was located on the Hoh River and was described as follows:

An ancient midden heap is also to be found on the Hoh River some 16 miles inland at a place called the "bench", on a benched area where the Olympic glacier made a stand on its retreat up the mountains from the coast (Reagan 1917:16).

Reagan also mentions a number of other archaeological sites at inland locations—"at Beaver Prairie, Forks Prairie, Quillayute Prairie, and at various camping places along the Quillayute River and its tributaries (Reagan 1917:9)."

Reagan's observations about the kinds of materials recovered from midden sites are not clearly linked to specific places or sites but apparently the "oven-mounds" he described (Reagan 1917:11) were observed on these prairie sites. [2] The study of such sites would obviously offer the rare opportunity to learn something about the prehistoric uses of vegetal food resources in this region.

In 1977, Wessen (1978a) carried out an archaeological reconnaissance of a series of localities along the valleys of the Quinault, Queets, Hoh, and Quillayute rivers. Using the "direct historic approach", this reconnaissance focused on the inspection of places that were reported in ethnographic sources (e.g. Olson 1936; Singh 1956, and others) and by local informants (apparently non-native) as the former locations of "settlements". There are 45 localities listed as places that were surveyed including 25 along the Quinault River, 5 on the Queets, 7 on the Hoh, and 8 on the Quillayute. [3] In an attempt to cope with the problem of site discoverability, soil auguring was emphasized although some other techniques were used in an effort to identify sites (e.g. soil pH and phosphate tests, and vegetation pattern analysis). Although Fonda's (1974) vegetation succession model for river terraces was used in the identification of landforms, it is unclear how the survey was conducted relative to these landforms.

The cultural resources identified were described as mostly "fire hearth areas, old cedar stumps, and historic homesteads (Wessen 1978a:58)". Charcoal-rich stratigraphic units (considered non-cultural) and individual fire-cracked rocks were observed widely throughout the areas examined (Wessen 1978a:60, 65). A variety of lithic artifacts (including a projectile point, "pile driver", cortex spall tools, grooved net weights) was found but "none could be demonstrably associated with any specific site (Wessen 1978a:60)". In general though, it was concluded from the survey that

Either the survey emphasis and procedures were, in fact, inappropriate to the specific requirements of this region, or, the survey work accurately reflects the extremely limited nature of preserved archaeological features. It is the writer's impression that the survey fairly accurately reflects the archaeological potential of these river valleys (Wessen 1978a:69).

Poor site preservation rather than problems of site discovery was considered the primary factor influencing the results of this survey (Wessen 1978a:71). Even though few cultural resources were recognized, it was concluded that the site discovery techniques (mainly soil auguring) "should remain, a mainstay of survey examination."

Despite the explicit intent of this survey to focus upon the locations of relatively recent, ethnographically reported sites, the results of this survey were nonetheless generalized:

While the archaeological potential of the Western Olympic Peninsula can, in no sense, be regarded as great, the possibility of significant fortuitous discovery, particularly with respect to "wet sites," is considered to be real and should not be overlooked (Wessen 1978a:74; emphasis added).

Very large areas of land have been surveyed during numerous surveys on public lands within the River Valleys and Lowlands Zone of the Olympic Peninsula. Virtually without exception, these surveys have failed to identify aboriginal archaeological sites (e.g. Wessen 1977a, 1977b, 1978a, 1978b, WAPORA 1980; Dalan et al. 1981, Dalan et al. 1981).

Before the archaeology of the Western Olympic Peninsula is relegated to waiting for fortuitous discoveries of new "wet sites", there are many questions that will need to be addressed. Some of these questions warrant mention.

What are the material correlates one would expect to find with the various ethnographically recorded "settlements"? Of the 45 localities examined during Wessen's (1978a) survey, only 16 (36%) are described as villages or places where houses were located. All of the other localities are identified as places of fish weirs, fishtraps, or simply named places. Assuming that all of these localities were perfectly preserved as they once existed in the 19th century, which of these sites would be expected to have actual midden deposits associated with them? Here it would be worth noting that many of the coastal midden sites represent accumulations that required a millenium or more to develop. Is is likely that deposits of similar character will occur on a landform that was available for prehistoric occupation for only 200 years? In alluvial settings, how were survey efforts focused relative to the terrace model proposed by Fonda (1974)? The lower terraces are quite young in an archaeological sense. If, for example, the search for archaeological remains was focused on the first terrace which is only 400 years old, what kind of midden development is likely to have occurred in the relatively short period of time such a landform could have been used?

Relative to issues of site discoverability and the use of augurs for site survey, what are the implications of the absence or scarcity of shellfish as a major faunal resource at riverine sites? How effective is a soil probe or augur for identifying subsurface features? What kind of features can archaeologists hope to identify with an augur and how can these be identified? Given the potentially great range of physical evidence that might be encountered at such diverse locations, is it likely that the use of a soil augur can reliably determine the presence of such diverse archaeological resources?

Considering the crude maps provided in most ethnographic sources and the lack of precise locational information for most named places, how much confidence should be placed in these maps as the basis for archaeological survey?

Lastly, is it defensible to extrapolate the results of survey conducted with the "direct historical approach" to the entire archaeological record of the Western Olympic Peninsula? It would seem that the results of these surveys may be more informative about the nature of ethnographic information and the utility of the "direct historical approach" than they are about the archaeological record of the river valleys of the Olympic Peninsula.

In sum, archaeological survey in this zone and in the entire region has been conducted as if the ethnographically described cultural systems were the only ones that have ever existed in this region. While the difficulty of site detection can not be underestimated, it is also clear that the survey methods that have been employed are ones which are appropriate to the detection of large midden deposits. Wide survey transects (up to 100 m or more), auguring, soil tests for pH and phosphate, and vegetation studies are all search techniques that assume that significant archaeological resources will manifest themselves like coastal middens. If this assumption is unfounded, then it might be argued that the survey methods that have been used in the forests of the Olympic Peninsula are for the most part inappropriate to the task. It will suffice to say that accumulating archaeological evidence from the Olympic Peninsula and throughout the Northwest supports the view that archaeological remains do exist in this zone and that the failure to identify archaeological resources in these settings is at least partially a failure of methods. This subject is considered further in Chapter 9.

Archaeological Expectations

1) Old Cordilleran residential sites and locations should occur on upper river terraces, prairies, and in the foothills where the winter ranges of migratory game are located. Assuming that the forest was reasonably open between 10,000 and 6,000 B.P., there should be a widespread but low density distribution of residential sites and locations (especially hunting and butchering sites) throughout much of this zone. These remains are likely to be represented mainly by concentrations of lithics in relatively low density reflecting high mobility. Midden deposits are not expected and preservation of organic material of any kind will generally require unusual conditions (e.g. water saturation). Site features will generally be limited to small hearths composed of rocks but only infrequently containing charcoal.

2) Most Old Cordilleran sites below about 1,000 ft elevation in this zone should be related to spring through fall season occupations. This is postulated to be a season of high mobility and small group size. The determinants of spring through fall season site locations before 3,000 B. P. are not expected to be rigid with the consequence that there is little tendency for reoccupation of the same places or vertical accretion of archaeological debris. This should contribute to the archaeological formation of relatively small, low density lithic scatters. Interception of ungulate resources in low relief areas during this portion of the year would probably require the positioning of hunters near places where encounters have the highest probability of occurring. Water sources such as lakes, springs and streams are likely to be among the most predictable locations for encountering animals in this portion of the regional landscape.

3) Due to the warmer and dryer climate before 6,000 B.P., the ratio of deer to elk is expected to have been higher in the early Holocene than in late Holocene or recent times. In those unusual circumstances in which there is preservation of faunal remains in archaeological deposits that are older than about 6,000 yrs. B.P., the ratio of deer to elk remains should be relatively high.

4) Locations where there are bedrock controlled channels, falls and rapids may be particularly important for their potential to have preserved sediments and archaeological remains that are older than those present on the first two terraces. These sorts of locations are interesting not only for their potential for older sediments but because they would be natural fishing sites for people using devices for taking salmon in a non-intensive way (e.g. dip-nets, leisters, and harpoons). As long as immediate consumption prevailed, there would be no need for mass harvest technology (i.e. seines, weirs, gill nets, traps). Similarly, even after the emergence of collector systems, spring and summer salmon fishing is expected to be mostly for immediate consumption and this would also tend to focus on these same places along the river channels. Because of salmon spawning requirements, the distribution of such sites will have as an upriver limit that zone of the streamway where gravels and cobbles are replaced by boulders due to increasing stream gradient.

5) It is postulated that burning of prairies began after 6,000 B.P. in response to the closure of forests occurring at that time. These prairies should show evidence of continuous usage after 6,000 B.P. Although ungulate resources would almost certainly have been exploited on prairies, carbohydrate-rich root resources are likely to have been of particular importance in the use of these areas. The most obtrusive kinds of archaeological remains in prairie settings are likely to be earth oven features used for processing roots. Such features have been described by Reagan (1917) as being mounds rather than pits. The use of such mounded oven features for root processing may be related to the wet sediments so commonly encountered in a region with such large amounts of rainfall (Alston Thoms, pers. comm. 1988).

6) Winter villages (and the collector land use system) should appear relatively early along the rivers of this zone and prior to the appearance of winter villages on the coast. This is especially the case for the Quinault and Queets rivers which have lengthy periods of annual salmon availability and high productivity. Virtually all types of sites associated with a collector system should occur in this zone once the riverine collector system came into existence after ca. 3,000 yrs B.P. In addition to the remains of winter villages and fishing locations, cultural resources that can be expected to occur along the river channels include cultural modified trees, especially cedars. The extraction of cedar for house planks and canoes as well as the removal of cedar bark for fiber clothing can be expected to have resulted in tangible remains in places along the drainages in this zone. Because of their perishable nature, such remains will necessarily be of late prehistoric age.

7) There should be a general congruence between prairies and the distribution of winter village sites along the rivers. Identification of the latter sites may be more difficult than is the case along saltwater due to an expected scarcity or absence of shellfish remains (except in the lower reaches of rivers) as well as the usual biotic factors that obscure archaeological remains in such settings.

8) Wessen (1978:53) noted two patterns associated with the native "settlements" historically recorded:

Settlements tend to be clustered toward the lower portions of rivers, and they tend to be located near stream confluences and near falls, rapids, or other relatively permanent channel obstructions (Wessen 1978a:53).

For the collector systems of land use that arose in the late Holocene, this pattern can be expected for both winter residential sites and fishing sites because of spawning requirements of salmon. Salmon require sediments in the gravel-to-cobble size range and would not find suitable spawning habitat at points upstream from the distribution of such sediments in the streamway (see Wessen 1978a:10-13; Bauer 1971 cited in Wessen 1978a:10).

Zone IIb: Northwestern Peninsula Rivers and Lowlands