|

National Park Service

A Study of the Park and Recreation Problem of the United States |

|

Chapter II:

Aspects of Recreational Planning

|

|

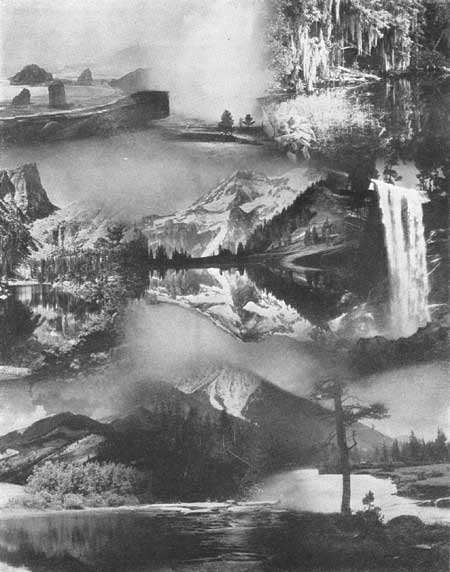

RUGGED MOUNTAINS—CALM, CLEAR WATER Mount Rainier National Park |

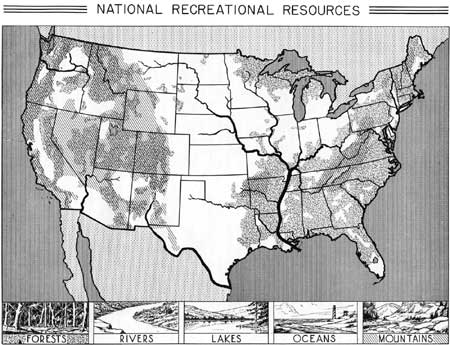

POPULATION AND THE RAW MATERIALS OF RECREATION

Population and Its Distribution. The 1940 population of the United States is estimated at 132,000,000 persons. Students of population have estimated that if trends in birth rates, restrictions on immigration, and other factors influencing population increases continue, it will result in a fairly stable maximum population of approximately 158,000,000, and that this maximum will probably be reached in about the year 1980.

Of our present population, slightly more than 50 percent is crowded upon less than 1 percent of our land surface—our cities and towns—and it appears probable that the percentage of urban population will continue to increase, barring some as yet unforeseen factor which would revise the trend.

Land and Water Areas, and their Relation to Population and Economic Requirements. The total area of the 48 States and the District of Columbia is 1,903,000,000 acres, of which 33,920,000 acres are covered with water. Studies have indicated that, from about 55 percent of the land, the needs of the prospective population of the United States for food, wearing apparel, shelter, and commodities for export (except forest products) can be met for an indefinite period.1 The United States Forest Service classifies 615,000,000 acres, or about 34 percent of the total area, as forest land and estimates that 509,000,000 acres, or about 25 percent of the total area should be used for the commercial production of timber.2 With only about 6/10 of 1 percent of the total area now occupied by urban populations, it is unlikely that more than 1 percent—including the playgrounds, playfields, parks and parkways within urban limits will ever be required for our cities. Thus we have available, over and above those special allocations cited above, approximately 361,000,000 acres, or 19 percent of our area, which may be set aside economically for special uses not directly related to the provision of food, clothing and shelter for recreation, watershed protection, wildlife conservation, or a combination of these uses. Nor does this acreage have to bear the full load of providing recreation. In addition to the tremendously important recreational service provided by urban areas set aside for that purpose, probably the most vital of all recreational services,?? recreation is an important by-product of much of that 509,000,000 acres of forest and wood lot and even, though in much smaller degree, of the lands devoted to agriculture.

1 U. S. Dept. of Agr., National Land use Planning Committee, First Annual Publication No. V, Washington, D. C. 1933, PP. 12-13.

2 Forest Land Resources, Requirements, Problems, and Policy, Part VIII of supplementary report of Land Planning Committee to National Resources Committee, 1935.

On the other hand, the potential contribution of much of that 361,000,000 acres available for recreational uses and not directly required for the provision of food, clothing, and shelter, is very low. It includes perhaps 67,000,000 acres of desert or bare, rocky lands which, while by no means lacking in recreational importance, can be utilized scarcely at all for mass recreation. Most of it, by its very nature, is located at a distance from heavy populations; virtually all of it lies west of the eastern boundary of Colorado, and in states of comparatively sparse population.

Natural Factors Affecting Recreation. These are commonplaces of park selection: that parks should possess topographic interest; that water, whether as stream, or lake, or ocean, contributes to attractiveness or beauty of appearance, and possesses permanent value for active recreation, in the forms of bathing, swimming, boating, fishing; that varied and attractive vegetation comes near to being essential; that temperatures, rainfall, winds, and humidity—the basic elements of climate all have an effect on the recreational usefulness of any area; that abundance and variety of wildlife lend important interest. However, be topography interesting or monotonous, water abundant or scarce, vegetation abundant or sparse, or climate salubrious or enervating, day-by-day recreational requirements are going to have to be met with the best that can be obtained near at hand. For a large proportion of the population, the charms of New England or California or Florida or any other summer or winter vacation meccas possess little significance. The influence of the factors named above is of major significance to that part of the population which has the means and the leisure for at least occasional travel some distance from their homes. In the United States this group probably comprises a greater percentage of the whole population than in any other country in the world. It is because of the mobility of so large a percentage of our population that we are fully justified in the establishment of parks and other recreational areas and facilities at a distance from concentrations of population, confident that if their natural characteristics possess high quality and their development is satisfactory, they will be patronized. Not only do such outlying areas render a direct service to those who use them, but also, by their "pull" upon those who can afford to seek recreation at some distance from home, they lighten the pressure on facilities nearer at hand at times—on week-ends, on holidays, and during vacation periods when that pressure is heaviest.

Figure 17. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Human Influences. In addition to those natural factors which affect the recreational "drawing power" of places and regions, a multitude of other factors, the result of man's own acts, have similar effects; and, like the natural factors, some of these are favorable, some unfavorable. They are normally the result of efforts undertaken for economic advantage—either the making of a livelihood, as in the case of the Tennessee farmer on his precipitous hillside corn patch, or a profit, as in the case of the coal operator or the paper maker whose wastes pollute the streams. By no means all of them have had socially undesirable results. Millions of acres of land once forested are undoubtedly more valuable, from every standpoint, as productive farm land. And, equally certainly, objection cannot be raised either to the mining of coal or the making of paper as such, but rather to any needless abuse or destruction of natural resources that accompanies them.

In this section it is not possible, of course, to paint a picture of all the changes man has produced in his natural environment and to evaluate their effects, favorable or unfavorable, on the recreational productiveness of that environment. We can only suggest some of the major factors, those of special and far-reaching significance in either expanding or limiting the usefulness of areas, large or small, for recreation.

(a) Pollution. Foremost in this group, it would seem, is pollution of the waters of streams, lakes, even of the ocean. A recent special report to the National Resources Committee says:

Half of the municipal sewage of the country is discharged untreated into water bodies . . . 2,300 tons of sulphuric acid are discharged into streams annually from abandoned and active coal mines. . . . Large quantities of culm from anthracite mines and huge quantities of brine from the older oil fields are deposited in streams. A large variety and a great volume of wastes are discharged from industrial plants.

Water pollution is a problem of national concern. It is especially serious in the relatively populous and highly industrialized northeastern sections of the country.

Recreational values which have depreciated or failed to materialize as a result of water pollution are even more elusive to measurement. They are affected by bacterial pollution which renders water unfit for bathing and by solid or dissolved substances which cause obnoxious odors, tastes, and color, and produce unsightly conditions that make the water unattractive to the angler, swimmer, or summer cottager. Pollution has caused the decline of recreational use of some water and land areas, particularly in metropolitan districts. It has been more influential in limiting recreational development in such districts and in forcing public and private agencies to seek more distant locations for park and resort facilities. A clear stream has aesthetic value which is real but intangible and its restoration or preservation may yield real community benefits.

The committee wishes to emphasize the importance and the intangible character of the wildlife and recreational effects of water pollution in comparison with its other effects. As the public health hazards are eliminated or minimized and as that abatement which patently is feasible from the standpoint of reducing water treatment and corrosion costs is accomplished, the justification for a greater degree of abatement will rest in considerable measure upon the values assigned to wildlife, recreation, and the aesthetics of clean streams. Public health always will be the basic consideration in pollution abatement, but the relative importance of wildlife, recreational, and general aesthetic considerations seems likely to increase.3

3 Water Pollution in the U. S., Third Report of the Special Advisory Committee, water Pollution N. R. C. 1939.

During the past decade rapid strides have been made, particularly through Federal cooperation, in the construction of municipal sewerage systems, and it appears that remedial measures will continue. The polluted condition of many of our smaller streams and most of the larger rivers is nevertheless still a serious problem. For example, much of the sewage of the Nation's Capital is still being discharged untreated into the Potomac River within the District of Columbia limits and through and alongside its parks and recreational areas. Waste from industrial plants continues to be a major problem which demands legislative action and perhaps subsidization. The industries which provide much of our employment in this country also provide the bulk of industrial pollution, hence correction is a matter of public concern not only from the social basis but also the economic concern for the continuance of the industry. It is unfortunate that the greatest stream pollution so frequently exists at the very places where the waters, if unpolluted, could render the greatest recreational return.

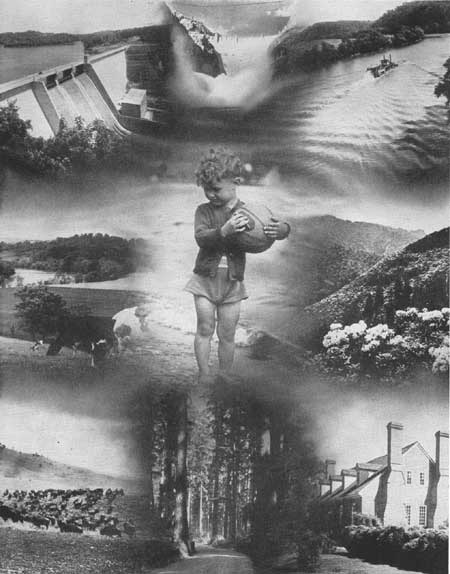

Figure 18.—More water recreational areas should be in public ownership.

(b) Drainage. The drainage of swamps and marshes has been one of the major causes of a seriously diminished supply of wild waterfowl. Those acres of marshlands, containing small lakes that supplied food, cover, and resting grounds for great flocks of ducks and geese, have been drained so that the land might be devoted to agricultural uses, often with disappointing results. In many cases the economic value of marshlands, as such, has proven to be greater than that of the land converted to agricultural uses. During the past few years considerable effort has been expended by the Federal and State governments in restoring swamps and marshes and in the creating of new water areas. The construction of reservoirs for power, irrigation, and navigation has sometimes made possible incidental but important recreational use of the impounded waters, though this is frequently offset by fluctuating water levels and low water during the season of highest recreational use, resulting in exposure of an unsightly belt of land at the water's edge, bare or strewn with unsightly masses of decaying vegetation.

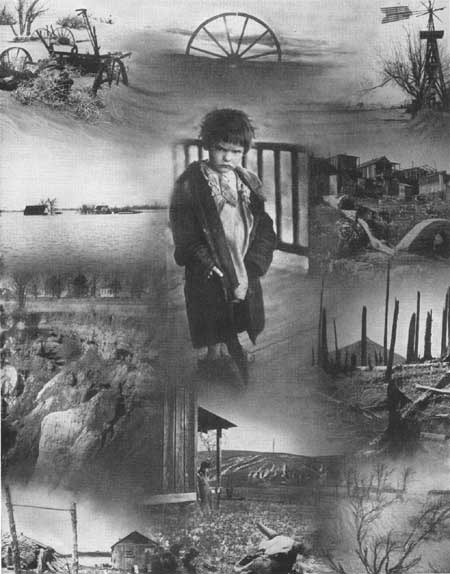

Figure 19.—We cannot afford to neglect our resources.

(C) Overgrazing, Fires and Other Misuses of Land. Overgrazing has prohibited reproduction of plant life and allowed erosion to set in on some lands formerly valuable for recreational use. The clearing, for agricultural use, of lands better suited to timber production, the harvesting of timber crops without regard to reproduction, have left lands in many cases worthless for agriculture or industry and for a long time spoiled for recreation. Broadcast burning, such as is still practiced on millions of acres of grasslands and woodlands, is a prize example of destructive land practice. Many of these are tax delinquent lands and will again come into public ownership. Lumbering is a justifiable economic use of land, and, when properly done, yields gratifying returns on many millions of acres. Also, when properly managed, forest lands have in many cases real recreational values.

Most cities have developed without advance planning, and as a result, natural features which should have been preserved for their recreational values were neglected and destroyed. Streams which might have been a major recreational feature in the front yards of cities have frequently become the refuse dumps in the back yard.

Figure 20.—They must be preserved.

(d) Monopoly of Facilities. As indicated at several points, the normal and proper functioning of society places heavy legitimate demands on our natural resources. We cannot expect, nor is it socially or economically desirable, to set aside every area that possesses recreational possibilities for recreational use alone, nor even always to encourage its use for that purpose in conjunction with other uses. There is, however, a very widespread employment of lands and waters in ways not of themselves improper or socially undesirable, but which prevents or limits recreational use of greater social value. Thus, the urge for private possession of frontage on ocean or Great Lakes waters, and on the waters of hundreds of lakes and rivers, and the frequently costly private developments which have been placed on them, have not only limited their usefulness in providing recreation but have made it extremely costly to recapture such properties in many situations where they would render a tremendous recreational service if publicly owned and developed for that purpose. As is natural, the most accessible recreational assets have been monopolized by a part of the people, to the exclusion of the remainder.

(e) Roadside Slums. Closely related to this situation is one which results in a definite and serious lessening of the public's enjoyment of automobile travel—the lack of public control of developments adjacent to highways. Though outdoor advertising is prohibited within the right-of-way in most States, its placement within sight from the road has made the approaches to most cities a nightmare, and the billboard companies seem almost invariably to place their posters in the most attractive locations possible out in the open country. A close second in undesirability are the shoddy structures which for the most part house those roadside business enterprises that cater to the travelers' needs or desires.

Regional Influences of Natural and Human Factors. Without attempting to cover the United States in detail, let us examine briefly the connection between these factors the natural ones and those that are the result of human activity in some of the major regions of the United States.

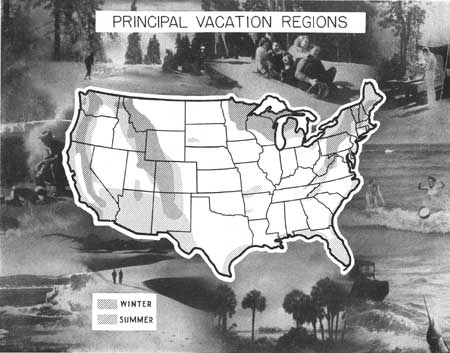

The Northeast, including New York and Pennsylvania; the upper portions of the Lake States; the Appalachians; the Pacific Northwest; the Rocky Mountain area extending from the Canadian border down into New Mexico; the Black Hills; even the southern coastal section of California, exert a strong summer "pull" on those who are able to seek recreation at a considerable distance. The factors are much the same topography that ranges all the way from the merely interesting to the most spectacular in America; abundance of forest and of plant life in general, except in southern California; varied water resources of streams, lakes, and oceans; temperatures which seldom reach extremes; lack of excessive humidity; in fact, most of the factors favorable to enjoyment of the out-of-doors in summer are found to exist in these regions. The black flies of northern New England, northern New York, and the upper Lake States are adverse factors during otherwise wholly pleasant early summer weeks.

Again the Great Lakes States, New York, New England and part of Pennsylvania, the Cascades, the Sierras, and the Rockies, with their cold winters and usual ample snowfall, invite distant travel for winter sports. The dry, clear air, the fascinating topography, the interesting desert vegetation, and the sunshiny days make the desert country of southern Arizona and New Mexico attractive during the winter months to thousands who have the means to travel in winter, even though water features and the vegetation that normally goes with moderate or abundant rainfall are largely lacking. Human migrants are drawn in numbers to the South Atlantic Coast, the Southern Piedmont, southern Florida and the whole Gulf coast and to southern California, during the winter, because of mild temperature, sunshine, and the many opportunities offered for outdoor activity on land and water.

Looking briefly at the reverse side of the picture, we may readily discern definite and extensive regions, which at one time or another during the year are avoided by most people who are seeking recreation and who can travel some distance to find it. During summer and winter alike, much of the Great Plains and prairie country belongs in this category, since in general this large region lacks outstanding topographic interest and recreationally useful waters, summers are hot, and winters are cold, with bitter winds. "Tourist income," in most of this section, is largely income from tourists on their way to some other place.

So, too, the Atlantic and Gulf coastal plain in summer is so hot and the air so humid that vacation seekers generally avoid it, the pleasanter narrow coast fringe serving largely to provide relief spots for the coastal plain and Piedmont hinterland. The occasional incidence of malaria in this extensive expanse of land is a further deterrent to tourist travel in this direction. And even though winter temperatures are relatively mild, the scarcity of sunny days, the long continued rains, and the moist atmosphere discourage winter travel into the Pacific Northwest, except for those who seek the excellent winter sports opportunities offered in the mountains.

With some exceptions, human influences, where they have been sufficient to affect recreational values at all, have affected them adversely. Thus, destructive methods of farming on the Piedmont and the mountain slopes above it and over parts of the Plains States, and overgrazing in much of the West, not only have resulted in the heavy economic loss of soils, but also have caused the silting up of streams with consequent damage to appearance, to enjoyment of bathing and other activities dependent on water, and to fish life. Cities, large and small, all over the country, are dumping untreated sewage into streams, there to mingle with industrial wastes, to offend the nose and the eye, to repel or kill aquatic life, and to render recreational uses unpleasant and dangerous. The ghastly appearance of mountain slopes after certain types of logging operation, particularly in the Pacific Northwest, certainly lessens the pleasure of touring, as does the smoke of the burning-over to which logged-over areas are subjected there, and of the set fires which are allowed to run each year over millions of acres of southeastern and southern forest.

Notable exceptions to the adverse effects of human activities are found in those places—located largely in the East and South—where history has been made and considerable effort has been expended to display and interpret its physical remains.

Relation to Planning. The foregoing discussion of population, and of the natural and human factors which contribute, favorably and unfavorably, to the recreational appeal of a place or of a region, suggests elements that demand their due consideration in the formulation of plans for selection of areas for outdoor recreation and for their development for such use. In this country we are subject to none of the artificial barriers and hindrances to free movement which handicap or prevent it in many parts of the world. Movement for recreation or any other purpose is conditioned almost wholly on available leisure and economic status. Probably nowhere else in the world are so many people and so large a percentage of the population in a position to avail themselves of opportunities to seek distant playgrounds. The ability to enjoy them at moderate cost, whether through availability of publicly provided facilities such as those of national and state parks and forests, or through those provided by private enterprise, tends to lengthen travel range for those of more limited means. This fact possesses great weight with respect to the necessity of providing areas, well distributed throughout regions of greatest outdoor-recreational appeal, in public ownership, and of placing on them facilities for vacation enjoyment that will involve the minimum drain on limited vacation funds. That is a responsibility properly to be expected of public agencies the group of agencies with whose fields of activity this report is primarily, though not wholly, concerned.

RECREATION AS AN ELEMENT OF LAND PLANNING

Planning for recreation is an integral and coordinate element of sound land planning for a city, a county, a state, a region, or for the whole Nation. Such planning will recognize that for certain lands recreation is the best economic and social use to which they can be put, regardless of other economic or social values that they may possess.

Fortunately, often—but by no means always—lands of low value for other purposes possess high value for recreation. Rough hills, rocky gorges, mountain tops, sand dunes, even deserts, are frequently susceptible of great recreational service. Even poor farm lands given proper care may, if properly located, be capable of providing much needed recreation, as abundantly proved by the recreational demonstration areas acquired and developed by the National Park Service. In many such cases recreation is the obvious best use; in others, decision involves a careful balancing of the potential recreational values against the other economic and social values which the area can supply. Recognition of recreational values as superior even to very great commercial values is attested in the case of scores of municipal and metropolitan parks and in those state and national parks which contain stands of merchantable timber, available power sites, lake, river, and ocean frontage which would be readily marketable for summer home sites, and a variety of other economic resources.

In some cases intrinsic values such as outstanding scenic features—indicate recreational use as obviously the highest and best use for certain areas. They possess qualities manifestly too rare and precious to be lost to the public. In a great many other cases, however, decision must rest upon such factors as need, location, accessibility, and capacity of any specific area to provide for the volume and kind of use required.

Planning by Regions. Recreational activities are, as a rule, not affected by political boundaries with in the Nation unless those happen also to be natural boundaries such as a large body of water or a high mountain range. It makes no difference to the Philadelphian whether he seeks his recreation in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, or Maryland—all within easy reach by automobile. More residents of Illinois than of Indiana use Indiana Dunes State Park. Choice of a recreational objective rests rather on such factors as amount of available leisure time and funds, means and ease of travel, and available facilities.

It is on such factors as these that the concept of recreational planning by regions is based. Regional boundaries may coincide to some extent with political boundaries, but in a country in which, generally speaking, State and county lines have been arbitrarily established, they do not normally do so. Recreational planning, like much other land planning, concerns itself ordinarily with two major types of regions. Of these one is the natural geographic region, such as New England, the Pacific Northwest, the Inland Empire, the Southern Appalachians each possessing a certain degree of cultural and industrial homogeneity, and each in at least some degree isolated from other regions which border it. The second is the metropolitan region, including one central metropolis, or even two or three, its or their satellite communities and such surrounding territory as is importantly affected by this major massing of population. While satisfactory planning is often dependent on acceptance of the region as a planning unit, accomplishment of the results of such planning still is dependent on the political action of those political subdivisions wholly or partly included in it.

Whether such regions possess recreational resources of sufficient interest to attract an appreciable volume of outside use or not, it may be said of each kind that the great bulk of the recreational requirements of its inhabitants, including all strictly day-use recreation, must be met within it, in spite of improved means of transportation and increased leisure time.

There have been a number of noteworthy regional plans formulated, chiefly for metropolitan regions, and the past few years have produced a good deal of planning for the geographic type of region. Success in such planning is dependent upon the fullest integration of city, county, State, and national programs; and success in accomplishment is equally dependent upon, first, a clear understanding of the part each political unit is to play, and second, adoption of such measures, concurrently on the part of each agency concerned, as are required for fulfillment.

An excellent example of such integrated planning is furnished by the Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Metropolitan Region. The close relationship of urban and suburban recreation and recreation facilities has been recognized, following a long period of close cooperation between Milwaukee and Milwaukee County, by uniting park administration in the county park agency. Recently also, the State Planning Board, in cooperation with the Milwaukee County Planning Department, has made a special study of the recreational and conservation problems of southeastern Wisconsin, into which the Milwaukee County plans have been articulated. The findings and recommendations of this study have in turn been integrated with the State plan. The part each agency is rightly expected to play is clearly defined; the obligations of each have been carefully calculated so that each will bear its fair share of the cost and the responsibility for administration.

The Tennessee Valley Authority, charged with planning for a region which includes part of seven States, from the beginning recognized the necessity of including provision for recreation as one of the social necessities and, though not set up to develop and administer parks, it has done just that at several locations in order to provide demonstrations and examples, for the Tennessee Valley as a whole, of this one of several special and necessary uses of land.

Multiple Use. How many parks can we afford? How many acres will be required for recreation?

The answer to these questions is expected to be given in quantitative terms. But recreation cannot be measured quantitatively, because it is a quality of living. Who can say when our living is good enough? Yet, there are published statements that the present acreage of parks is all that the country will ever need. The only honest answer to these questions is, we believe, that the struggle to improve our living is a never ending one, and that so long as any cultural and recreative factor in our historical and natural resources is being needlessly destroyed it is a challenge to Federal, State and local governments to take appropriate steps for its preservation. Park status in such cases may be a more useful and productive status than any other, and present indications are that we can afford to live more generously than we have realized.

G. A. Pearson, in the March 1940 issue of the Journal of Forestry, says:

Foresters no longer believe that every acre of land that can be made to grow timber must be used for that purpose. One hundred million acres of productive and well-located timber lands could be made to produce annual yields far exceeding present consumption in this country. Additional areas to the extent of perhaps 300 million acres might well be kept in some sort of forest in the interest of recreation and watershed protection, and to provide a reserve acreage for timber production.

William B. Greely, in the November 1939 issue of American Forests, says:

The threat of a timber famine in the United States is passing. The public and industrial efforts in fire prevention and other essentials to forestry are bringing about a growth of timber more than adequate to supply all present requirements of consumption. The economic problem of forestry in the United States hereafter will not be how to supply enough timber for our requirements—but how to find sufficient markets for the timber crops that these great areas of land will increasingly produce. The forest problem, like the wheat problem or the cotton problem, is fundamentally one of markets.

If lands are no longer required for one use, it seems only common sense that we put them to another use. If lands are no longer needed for growing timber, for instance, or for some other industrial purpose, and they are of outstanding scenic and recreational character, would it not be simple wisdom to reserve them for recreational use? The answer would more often be in the affirmative, except that the multiple use theory obscures the facts by promising more than the lands can produce.

Under multiple use it is said that the commercial resources of a proposed park are so intertwined and are of such great importance that the only way the area can be profitably managed is to exploit all of the resources equally and simultaneously, and, that if this is done, the recreational resource will receive full consideration along with the rest.

It is a Utopian theory. In the first place, it does not recognize the nature of the recreational resource which consists of the other resources in combination. As much as you take from each of the component resources, by so much do you take from the combination. As numerous writers have pointed out, this system of management, failing to recognize the dominant resource of a given area, detracts from its value by giving equal opportunity for the exploitation of subordinate resources. This is apt to be little more than multiple abuse or a jumble of inconsistent uses.

There is no virtue in advocating multiple use of a watershed that is worth a thousand dollars an acre for water catchment purposes. By the same token, there is no virtue in advocating multiple use of an irreplaceable scenic resource that is of public inspirational value. To do so is to try to be all things to all people. This, the absence of planning, has been so widely accepted as a method of planning that it has become one of the greatest obstacles to sound land classification.

Multiple use is a common, and very often a good phase of land management. Actually, the term is not definitive. As it is commonly accepted, however, it means the specific brand of land management that sets multiplicity as its objective and permits an equal rating of resources.

G. A. Pearson says:

The land management plan envisioned in this article conveys two conceptions of multiple use. In one, management is by units in each of which one use is dominant though not exclusive; in the other, all uses are accorded equal rank on the same area. . . . The second plan is applicable, theoretically where all factors are under complete control; but, because this situation can rarely be attained, the plan is adapted mainly to lands on which all uses are so low that priorities have no practical significance. Forest lands, both public and private, are now being handled, with minor exceptions, according to the second plan. In order to realize the highest values the trend must be more and more toward the first. . . .

Von Ciriacy-Wantrup, in the July 1938 issue of the Journal of Forestry, said:

Under the concept of optimum use there may be several uses. The idea, however, is not to have several uses always but to permit them if they are socially desirable. In many cases the optimum use will be a single use rather than some combination of several uses. In other cases it will be one dominant use and as many subordinate uses as do not interfere with the dominant use. In a few cases there may be two or more co-dominant uses of nearly equal importance.

Nobody could have any quarrel with multiple use as a descriptive term, provided it is only an incidental aspect of optimum use. A national park, for instance, which the multiple use exponents usually refer to as a single use form of land management, actually may provide several uses. It may provide vital watershed protection; serve as a wildlife sanctuary, as a natural and historic museum and place of public education; it may serve as a source of employment for local labor and a market for local products; increase the value of adjacent and tributary property and, at the same time, serve as a stimulus to national and international travel, which in turn stimulates a host of other industries. All these uses are incidental to the dominant use of the land for recreation. In such case the optimum use of the land includes several uses, but multiplicity is not the objective: it is an incidental, and even an accidental, phase.

It is believed that the exponents of multiple use really have optimum use in mind, for obviously multiplicity as such cannot be considered as an objective. It is almost certain that they have no thought but that the natural resources should be appraised with intelligent selectivity. If that is the case, then they should by all means recognize it and admit that they do not hold multiple use either as a formula for land management or as an objective. Such action would revolutionize public land management. It would lead to the classification of lands according to their best uses. It would mean, for example, as Pearson says, that "Livestock production like timber production would profit immensely, if instead of trying to utilize all land regardless of quality, the range industry were concentrated on lands really suited to it by climate, soil, and water facilities." It would mean that a national conservation program, insofar as the public lands are concerned, would be rational and flexible and that recreational lands would be classified as recreational lands rather than as forest or range or some other category for which they are largely useless. Such areas would be more apt to retain their distinguishing characteristics, and to render their maximum usefulness, if they were so recognized.

RECREATIONAL AREA SYSTEM PLANNING

Preparation of a sound recreational system plan must be based upon determination of the following major factors as exactly as possible:

1. The recreational requirements of the population to be served, by kind and quantity.

2. The kind and quantity of land needed to meet those requirements.

3. The lands available and suitable for the kinds of recreation to be supplied and not more valuable for uses other than recreation.

The planning of recreational systems and areas is not an exact science. Study, research, and the pooling of experience gained over periods of varying length and under a great variety of conditions, however, have provided some bases for guidance in determining area and facility requirements.

There is no standard pattern for such planning. Since there are infinite variations in population distribution, economic status, transportation, climate, character of lands available, and other pertinent factors, no county or State or regional plan can be superimposed upon any other area; each must be formulated upon the conditions found in the area to be served. There are, however, principles of planning, increasingly clearly understood, acceptance of which is in the interest of economy and efficiency.

In the process of site selection, these principles are based upon common sense considerations of economy and effectiveness:

1. In choice between sites of comparable character capable of serving approximately the same populations, that one should be chosen which can supply its intended uses at the least cost for acquisition, development, and operation. This statement may appear to be so obvious as not to be worth mentioning; the history of park acquisition, however, is full of instances of the ultimate costliness of cheap land, or land acquired by gift.

2. A single site which will serve a variety of recreational uses is preferable acquisition costs being approximately equal to several sites which, taken as a group, may appear capable of providing for those uses. In general, the development cost of the group of separate sites will exceed that for the single site; so will the day-by-day cost of administration; and these differences in cost can and should be calculated fairly closely before a choice is made.

Since costs of development, administration and maintenance are factors in sound land selection, and these can be determined only on the basis of competent development planning, it follows that such development plans and calculations of the cost thereof need to be undertaken in advance of final decision on site selection.

3. Though acreage figures may be of some use for rule-of-thumb calculation of total recreational land needs—such as the acreage standards rather widely accepted for municipal park requirements—they can be seriously misleading. Because of the fact that terrain of certain types, especially broken or rugged, does not lend itself to intensive uses, it is conceivable that one area of a hundred acres would supply a total of recreational use that another of 500 acres would be incapable of supplying except at prohibitive cost. The only measure of sufficiency of acreage is its adequacy to supply the quantity and kind of recreational use for which provision is desired, and it is better to err definitely in the direction of too much than too little.

4. "When you are in a park, all that you see is in the park."4 For the visitor to Shenandoah, the ranges of the Alleghenies to the west are as much a part of the park, as far as eye enjoyment is concerned, as if the national park boundaries had been extended to include them. The adjacent slums, the shoddy roadside stand, the billboard or the ramshackle, advertisement-covered barn, if visible to the park visitor, in the sense that they directly affect his enjoyment of it, are a part of the park. This fact points to the necessity of selecting sites, wherever possible at reasonable cost, sufficiently roomy to permit intended intensive use at such distance from its boundaries that intrusions of the sort enumerated are not a part of the park picture or that there is at least adequate opportunity to plant them out of the picture. Selection on such basis has the added advantage of discouraging establishment of those parasite enterprises which inevitably attempt to obtain profits from park use which properly should go to the public.

4 George Parker, Hartford, Conn.

In the creation of what are generically designated as "park systems" a variety of special designations are employed, which vary as to actual meanings in various states and communities. The name "park," without other qualification as to character, is applied in one place or another to virtually every type of area found in park systems, from an Indian mound, an acre in extent, to the more than 2,000,000-acre Yellowstone National Park. As used in this report, the several special designations are presumed to have the following meanings:

The word Park is a generic term, used to designate all types of areas established and maintained wholly or dominantly for recreation, whether the recreative process be physical, intellectual, or spiritual, or a combination of two or all three.

A Monument is a park area set aside primarily because of its possession of scenic, or historic, or prehistoric, or scientific qualities, or any combination of these, and is characterized by the maximum degree of preservation and protection of those qualities.

A Parkway is an elongated park of which a principal feature is a pleasure vehicle road throughout its entire length. Abutting property, as in the case of any park, has no right of light, air, or access.

A Wayside is a park, usually of limited extent, established as an adjunct of a highway, and providing the highway traveler with a location, in public ownership, where he may stop for rest, for picnicking, or to enjoy an attractive view.

A Trailway is an extended and continuous strip of land under public control, through ownership or easement, established independently of other routes of travel and dedicated to recreational travel by foot, bicycle, or horse.

The following types of areas set aside under public control for purposes other than recreation many times can and do offer recreational opportunity in addition to their primary function:

A Forest is an area set aside primarily for timber production or watershed protection.

Wildlife Reservations may be grouped under the following three classifications:

A Wildlife Sanctuary is an area set aside and maintained for the inviolate protection of all of its biota.

A Refuge is an area wherein protection is accorded to selected species of fauna.

A Preserve is an area set aside and maintained for the production of all, or certain designated species of, wildlife on a sustained-yield basis.

RECREATIONAL AREA PLANNING

Any area devoted to recreational use of any type may be said to have been wisely selected for its purpose when selection has been determined by the logical relating of needs, on the one hand, to the capacity of the area to supply them at reasonable cost, on the other. Admittedly, in the case of an area selected because of its possession of exceptional inspirational qualities, "need" is the great imponderable, and a decision as to selection may often have to be based on some such determination as this:

Here is an area possessing qualities so inspiring, so satisfying to the human spirit, that we are justified in acquiring it and protecting its inherent values, even though it may not be visited by the thousands—perhaps could not be without destroying the very qualities that make it worth public possession. We shall do this in the profound belief that the return to the individual visitor, and to society as a whole, provided by such an area as this, will be sufficient to justify our acquiring it for the benefit of those sensitive and appreciative persons who will seek it out.

It is apparent that selection, on the bases indicated above, cannot be satisfactorily consummated without at least a careful advance reconnaissance, for the purpose of appraising existing values and possibilities for development inherent in the area, visualizing the principal elements of the ultimate development and formulating estimates of the cost, both of installing and maintaining them. It is depressing to reflect upon the great sums of money that have been required to supply necessary facilities in certain areas, and the other considerable sums which will, henceforth, be required to operate and maintain them, because of failure to give them proper study in advance of acquisition.

Abundant and safe water, and adequate sewage disposal facilities of course, essentials in any park—are basically so necessary that it is doubtful if any other development should be initiated until there is absolute assurance of them. Frequently costs on these two items are many times the expected amount, and the fact is discovered only after lands have been acquired and a program of development undertaken. Geological examination and a study of well drilling records in the vicinity will almost invariably indicate the probable depth at which water may be obtained. Similar examination of soils will also indicate the nature of the problem of sewage disposal and its approximate cost.

As any park planner knows, road construction is a heavy item of cost in almost all parks of any extent. Certainly, before an area is acquired and a general development program is undertaken, the approximate cost of required road construction should be ascertained. Yet, to do this, the essential features of the development, the items to comprise the development program, and the approximate location of the principal facilities must be determined with a reasonable degree of certainty, since the location and extent and character of the road system is largely based upon these.

In connection with any program of development, advance planning of an area, if it is to be adequate, must look beyond the development stage to the time when operations must be carried on. A gift of land is no gift at all, and low-cost land no bargain, if development or operation and maintenance entail unduly high costs. Operation and maintenance costs are of particular importance since they constitute a burden that must be borne "from now on."

Perhaps an example will help to indicate what is meant and how important fairly detailed advance study is.

Let us assume that one of the main factors in a preliminary decision to acquire an area is the presence of a good stream, of which a part of the course is through a basin where an artificial lake or pond is expected to become one of the principal features of the prospective development. Superficial examination indicates that the site is good. Yet before it is possible to be sure the site is actually a feasible one or that a lake can be created without inordinate expense, or that, if created, it will adequately serve the purpose or purposes of its construction, a good deal of study is necessary. Since creation of an artificial body of water, even under favorable conditions, is frequently a major item of expense in a general park development program, that study is also, in the long run, an important economy.

There are three main factors which will largely determine the cost of the dam itself. The first of these is the subsurface condition at the prospective dam site, to be determined by the digging of test pits on the site or the boring of cores, to determine the depth to bedrock, and the character of both the material above bedrock and the bedrock itself. Often the depth is such as to require a much greater amount of excavation than was anticipated. Occasionally the bedrock will be found to be of porous nature or so badly disturbed or broken, or to contain downward tilted, pervious bedding planes which either make the site unsuitable or require expensive grouting.

Again, in several instances encountered in Civilian Conservation Corps construction, for example, a nose of rock at the dam site appeared to be ideal for excavation of the spillway, though later borings showed that the character of the rock was such as to require a concrete lining.

The second factor is the occurrence and availability of construction materials. If these are near at hand, easy to excavate and transport, the situation in this respect is fortunate. If these favorable conditions do not exist, the cost of placing the material at the site or in the dam may be multiplied many times by a long haul, difficulties of excavation, road construction to the point of excavation, the necessity of screening the material, et cetera.

Figure 22. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

The third factor is the volume of maximum flow in the stream to be impounded. In some cases this may be determined from stream gauging records, but on many streams such records do not exist. In such cases, the maximum flow is determinable only by ascertaining the extent, topography, and cover of the watershed and a study of rainfall records for the vicinity. In its connection with prospective costs of construction, this item is important, since it determines the size and character of the spillway which, in cases where flood volume is large, is a costly element in the construction task.

Assuming, however, that the construction of the proposed dam involves no great difficulties and no unreasonably high costs for materials, only one part of the study has been made. What remains to be done is fully as important. In addition:

1. It should certainly be determined, on the basis of accurate flow records if possible, that the supply of water will be ample not only to fill the lake, but to keep it filled.

2. It should be determined that periods of high water, when the crest nears the top of the spillway, will not result in overflow on and damage to private property, or to proposed developments along its shores within the park.

3. If the lake is to be used for bathing, it is vitally important that sanitary conditions on the watershed which might affect its present or future use be carefully ascertained.

4. Since erosion upstream, within or without the park, will directly affect both the ultimate character of the lake basin and its usability at some or all periods, it is necessary that erosion factors be studied, and the means and cost of control determined in cases where these are of significance.

5. If the lake is to be used for bathing, it is important to determine both the availability of beach site and the approximate cost of providing it.

6. If the lake is to be used for fishing, it is important to ascertain in advance how good a fishing lake it will be and at what level it can be expected to be most productive.

7. It is important to determine all the uses to which the lake is to be put; how, and at what cost they can be provided; and how the lake, once it is filled, may affect other proposed or desired developments.

Let us acknowledge at the outset that every park constitutes an individual problem in planning, and that no plans for one park may be superimposed on another. Granting this, however, certain facilities are required in every park, others are common to many, and there are some general principles which must apply to virtually every park plan if the result is to be efficient and economical.

As already indicated, every park requires a sufficiency of safe water and adequate and safe sewage-disposal facilities. Every one is certain also to require a certain amount of road. Every one of any size must have also the facilities for maintenance truck and equipment sheds, repair shop, storehouse, etc., and should have a residence at least for the custodian. Beyond these essential facilities there are, of course, a great number of others that will be determined by public demand or need and by the capability of the area to provide them at reasonable cost.

There appears to be almost universal agreement among thoughtful planners that wherever possible there should be a single vehicle entrance. Such entrances should be kept to a minimum, if for no other reason than that a multiplicity of entrances means also a multiplicity of road mileage to build and maintain. Limiting the number of entrances to one or two undoubtedly is an important aid to control of use.

Whether Indiana originated the idea or not, it seems to have pioneered in formulating and utilizing the principle of what they have long called the Service Area, a term used to describe the grouping, in fairly close but not crowded proximity, of all those facilities which are provided for intensive use, such as hotel, cottages, restaurants or lunch rooms, the park store, picnicking, camping, and bathing. Purely from an administrative stand point such an arrangement is desirable, in that distances traveled for patrol or maintenance purposes are cut down, with a reduction in time and travel cost, and mileage of service roads to build and keep in repair is kept low. Likewise, the original cost and cost of maintenance of utilities—water, sewage disposal, electric lines—is lower than if facilities are unnecessarily scattered and separated. In addition, "the defined service area, serving as it does a place of congregation and redistribution, handles large numbers with comparative ease. From it radiate trails through woods and by shores. It serves, so to speak, as a filter. But above all, it saves the landscape from ruin."5

5 Ninth Annual Report, Indiana Department of Conservation, 1927.

Such an arrangement of facilities excludes no one from enjoyment of solitude or of any of the natural loveliness that a park may possess. Those who wish these things may find them—usually at a mighty short distance from the "service area," since man is a gregarious animal and only a few of him are inclined to stray from others of his kind.

Selection of a "service area" site involves a number of factors. Preferably it should be definitely removed from the entrance. By this means its surroundings may be completely controlled and establishment of parasite enterprises on adjacent private property at least discouraged, if not prevented. Since its development and use necessitate a considerable modification of the landscape, it should be placed, if possible, where the landscape values to be disturbed are low, and the site should be sufficiently spacious so that if expansion proves necessary it can be provided without having to go to an entirely new site.

In determining a location for the utility area, the same consideration for landscape values should govern. And since, at best, such a group of structures and their appurtenances such as piles of building material, for example offer no particular attraction to the eye, it is desirable to conceal the whole thing as much as possible. It should be definitely separated from but reasonably convenient to the service area, or to one of them, if more than one has to be provided.

Selection of a location for the custodian's residence has been a fruitful source of discussion and argument. One person will advocate a site close to the park entrance; another would put it adjoining a service area; another would integrate it with the utility area; another would isolate it completely from all other development. Decision must, in the last analysis, depend largely upon the conditions of any particular park. It is desirable, however, so to locate it that the family of the custodian may have some degree of privacy, of separation from crowds; and to assure that, the park office should be located elsewhere than in the residence.

The following miscellaneous conclusions or admonitions with regard to planning are based upon observation of a very large number of park plans and developed parks, in which, at one place or another, every conceivable planning error has been made.

In the lay-out of both picnicking and camping facilities, endeavor to supply a fairly well-defined area for each picnic group or camping party, but seek the golden mean between crowding and complete isolation. Too crowded a condition tends only to duplicate city conditions from which presumably the park visitor wishes to escape. Too scattered an arrangement imposes wear, and consequent modification, on a needlessly large amount of landscape; it likewise entails additional installation and maintenance costs for water lines and either additional sanitary facilities or unsatisfactory sanitation. The same considerations should govern the lay-out of cabin groups. Many of these have been constructed with a liberality of spacing that apparently contemplates occupancy by habitually noisy persons an assumption not warranted by actual experience in any well-operated park.

It is not necessary to construct a road to every beauty spot in a park. The American motorist can hardly be said to lack opportunity to view natural loveliness; some of the best of it should be left for enjoyment in quiet and even in solitude. Where it is desired to bring a road close to a charming waterfall or a pond or some other attractive and unspoiled feature, it surely should be kept out of the picture as much as possible.

Provision in parks for the man or woman on foot should recognize both the hiker, who counts his coverage of ground in miles, and the stroller, who is either physically incapable of covering long distances on foot or simply not inclined to undertake such activity. This dual type of pedestrian activity indicates carefully graded paths, preferably providing short circle trips of half a mile to a mile or more, in the vicinity of concentration points, and actual trails which by leading to worth-while objectives, offer something more than the means of walking for its own sake.

If the area is characterized by genuine natural charm and beauty, every development, whatever its character or purpose, should be subordinated to preservation of those qualities.

If parents who come with their children are to find some relief from their daily cares, every recreation area, whatever its character, should contain a play place for the children where they can find their own amusements enjoyably and safely, even though it means provision of playground apparatus.

What kind of activities shall be provided in any park? How far shall we go in providing tennis courts, playfields, baseball diamonds, golf courses, etc.? How warm have been the arguments, at meetings and conferences, over these questions! And, usually, how inconclusive.

The answer here given is believed to be a reasonable one. Let us base it on any area that possesses real grandeur and beauty, that contains natural features that should be kept unspoiled, unmodified, in all their natural charm. Let us assume that it is big enough amply to justify the visitor in staying in it a week, or two weeks, or a month, and finding in it a constant succession of thrills and surprises.

We all agree that man does not live by bread alone. Neither does he, except in the rarest instances, live long on bread and scenery alone. Even though the individual knows and loves the out-of-doors and possesses a deep understanding of nature and her processes, he is a rare individual who does not wish, over a period of a week or more, mostly spent in direct enjoyment of the natural out-of-doors, to engage in other activities. There appears to be nothing wrong in principle to providing the means therefor a fairly diverse choice of other means of passing the time enjoyably, and the wisdom of this appears to be widely recognized. Assuming that prospective use will justify the cost, then it would appear that installation of such facilities should be governed by these considerations:

1. That it does not involve destruction or serious modification of or close encroachment upon significant or rare scenic, historic, or scientific features—those things which constitute the park's raison d'être.

2. That such development shall supplement, and be subordinate to the primary purpose or purposes of the area.

3. That it can be adequately maintained.

If the first of these three points is accepted, there seems to be no reason to suppose that the wisdom of the second and third will be seriously questioned. As a matter of fact, Point No. 1 is a sharply restrictive one which, if applied universally, would possibly result in elimination of many such recreational facilities now established or would have excluded them from establishment originally. In application, sharp differences of opinion might well arise as to how serious any prospective modification might be or how close an artificial development of any kind should be permitted to come to an area or feature of exceptional or distinctive quality. That is a matter for individual solution in which it can only be urged that every effect of modification or encroachment, as concerns both sight and sound, be determined and evaluated as carefully as possible in advance.

Taking the whole field of park development, there is probably considerable overemphasis on substantiality, permanence of park structures. Though many potential mistakes of location and of individual design may be obviated by care in planning, even the most conscientious planning will not wholly eliminate them, especially in development of new areas. In many instances, it would be decidedly wise to provide structures of limited life. Thus if their design proves inadequate or their location not the best, mistakes of design and location may be corrected within a reasonable time without requiring the razing of structures built for very long life, as many structures have been built in the past, to the subsequent regret of those who have had to maintain and operate the areas in which they are located.

In its essence, adequate park planning involves these basic requirements:

1. Reconnaissance in advance of acquisition.

2. Determination of the logical and economical relationship among the several items of development which appear to be required or desirable.

3. Modification of natural environment only when it is certain that values resulting will fully balance the losses.

The Master Plan. In competent master planning lies the first key to ultimate success in operation and utilization of any area, small or great. It simply represents an attempt to determine how prospective use of an area shall be provided for most effectively, at the same time safeguarding natural or historic features and making possible operation, maintenance and protection at the minimum of year-after-year cost. Like any plan based upon predictions which cannot possibly be exact, it must be flexible, subject to modification as experience or considered afterthought or changed conditions indicate change to be desirable and wise. As a guide to orderly development, its value and importance are inestimable. It seems worth while to stress again the vital necessity of relating this plan, and the layout plans which ultimately become a part of it, and which indicate in more detail the location of individual developmental features, to practical considerations of operation and maintenance. How is it going to work? What is it going to cost to make it work? These are the pointed questions which must be wisely answered if it is to be anything more than a pretty picture on paper and an endless and unnecessary drain on public funds, with which neither the user nor the administrator will be satisfied.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

park-recreation-problem/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 18-May-2016