|

National Park Service

A Study of the Park and Recreation Problem of the United States |

|

Chapter I:

Recreational Habits and Needs

|

|

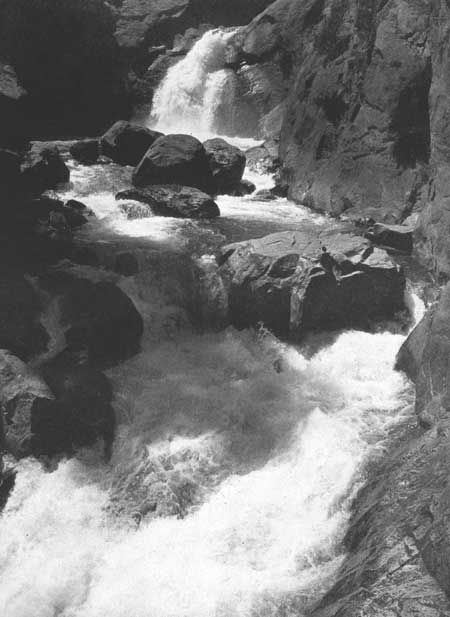

ROARING RIVER FALLS—THE SPARKLE OF

WATER IN RESTLESS MOOD Kings Canyon National Park, California |

RECREATION is the pleasurable and constructive use of leisure time. It is a physical and mental need, a necessary relaxation and release from strain. Recreation may be physical, intellectual, emotional, or esthetic; it may be active or passive; it may be engaged in virtually anywhere and at any time; it is individual, personal, spontaneous, and involves freedom of choice. It comprises all the endeavors in which man participates solely for the enjoyment they afford him. This enjoyment may be transitory or it may be a thrilling experience, the memory of which colors a lifetime. Since that which benefits the individual benefits society, recreation becomes a concern of society.

In formulating a recreational plan it becomes necessary to find out what activities people desire and need to afford them maximum satisfaction. This cannot be determined altogether by observing the forms of recreation that are the most popular at a given time in a given population group, since individuals generally want to do those things they know from experience will afford them satisfaction; and their experience, in turn, is limited by their social and physical environment. In order accurately to appraise man's recreational wants, consideration must also be given to those characteristics which distinguish him as a being. Probably the most significant of these characteristics is his desire for new and more satisfying ways of life. His first concern has always been to provide food, clothes and shelter. When these become easy to obtain, he sets about improving their quality. This urge for improvement, for new and better ways of living, has been responsible for his progress. It has fathered new social, political, and economic systems, new discoveries in the field of science, new inventions; it has spurred him to explore the earth in search of those resources which contribute to his well-being, to build railroads, concrete highways, and towering cities.

Observing the purposefulness and the bent of his endeavor when not under the compulsion of feeding, clothing, and sheltering himself, scientists have concluded that he is driven by a need for self-expression; that this need is as fundamental as his need for food, clothes, and shelter, and that, in fact, in many individuals it appears to be even greater, since there have been countless thousands who sacrificed life itself for such goals as political and religious liberty, which have little or no relationship to standard necessities.1

1 The Theory of Play by Elmer D. Mitchell and Bernard S. Mason.

His ways of satisfying this need take the form of an adjustment of his native characteristics to his physical and social environment. According to scientists there is no difference, physically, between modern man and the first of his kind to emerge from obscurity. He is, generally, of the same size and build, he has the same mental capacity, and the same fundamental emotional responses. His habits of conduct are organized around the same instincts and drives, the same impulses as motivated the conduct of primitive peoples. Thus, his activities, while strongly colored by his environment, are similar in many fundamental respects to those in which his early ancestors engaged.

Physically, he is a running, jumping, climbing, fighting individual. As a primitive, he employed these aptitudes in eluding his enemies and in procuring the necessities of life; today he exercises them through such sports as football, track and field events, boxing, wrestling, swimming, hiking, and mountain climbing.

His innate love of companionship has been important in shaping his way of life. As a primitive, it was a factor in causing him to band with others of his kind for work and play and for protection against common enemies. Today, his social habits and interests are vital elements in the highly socialized economy he has created, and constitute important motives in shaping his recreational desires.

The earliest records of man reveal evidences of a feeling for harmony and beauty which he expressed through his arts and crafts, his music and dance, through his use of words in story-telling and oratory. This same love of harmony and beauty today causes him to write poetry, compose music, paint pictures, sing, play musical instruments, listen to concerts, travel hundreds of miles to view a beautiful area of natural scenery, and spend hours molding a piece of clay.

He is endowed with a lively curiosity, an urge to handle, uncover, take things apart, explore. This endowment led his early ancestors to pry into the secrets of their environment, to seek the answer to the daily riddles that confronted them, to reason things out; it enabled them to rise above their environment as a start on the road to civilization. This same curiosity and the ability to think creatively causes modern man to engage in activities which have as their objective the acquiring of knowledge for the pleasure it affords, for the thrill that comes from new discoveries concerning himself and the world in which he lives; to become a philosopher and scientist.

Above all, man's ancestors were children of nature a part of the natural scheme of things—attuned to its delicate balance, fearful of its tantrums and its dark secrets, at the same time worshipping it as the source of life. In conformity with these emotional experiences of the past is modern man's need to participate in those activities which take him back to the haunts of his forefathers, that enable him to renew old and thrilling associations, to camp, hike wilderness trails, and experience the thrill of tracking wildlife in its native haunts, either for the kill or to take a picture of it.2

2 The Theory of Play by Mitchell and Mason; An Introduction to Social Anthropology by Clark Wissler.

There are many other examples of similarities between modern man's activities and those of his early ancestors, but those cited above illustrate the importance of native characteristics in shaping his habits of conduct. When considered in the light of the changes he has brought about in his social and physical environment, they provide a reliable index of those needs which he seeks to gratify through work and play.

The changes he has wrought in his environment have come about through the age-long process of one generation handing on to the next its habits, attitudes and ways of life, which, in turn, have been modified by the new generation's efforts to improve conditions as it found them, to discover new and more satisfying mediums of self-expression. A few of the more important of these changes will illustrate this process.

Once man was a hunter, a herdsman, a farmer, depending directly on nature for his necessities; today he is a specialist who works in a highly complicated industrial civilization for a livelihood. Once, too, he was a craftsman whose work enabled him to find those satisfactions derived from creating useful and beautiful things with his hands; today he earns his living by devoting all his working hours to screwing nuts on bolts, to shoveling coal into a fire box, to practicing corporation law, or to selling life insurance. This same trend is also applicable to the farmer who now depends almost entirely upon the industrial system to furnish him with his clothes and many of his foods and with the tools of his trade, and who, to an increasing degree, relies upon urban amusements for his recreation. The scope, then, of the individual's occupational endeavors has been drastically curtailed, forcing him either to deny his desire and need for a wide range of self-expressive activities, or to find these satisfactions outside his work.

As compensation for this specialization, he has, through his technical inventions, made it possible for one man to do the work it once required several to do. Thus, instead of having to toil long and exhausting hours, he now works seven or eight hours a day, five and a half days a week and, as a result, has a growing abundance of leisure which he may, if the opportunity is afforded him, devote to those satisfying activities which once constituted a part of his occupation, or to others which provide him with enjoyable mediums of self-expression.

Not only have his technical inventions shortened his work day, but they have, by improving his means of travel, increased the space in which he may both work and play. Once he was limited in all his activities to the distance he could cover on foot; today he speeds across the face of the earth in trains, power driven boats, automobiles and airplanes. As far as time and effort are concerned, he can travel a hundred miles today as quickly and easily as he once traveled five miles.

Finally—and this is probably the most important change he has wrought in his way of life—he has substituted an environment largely of his own making for that in which he spent the first several thousand years of his existence as a species. He has built great cities and literally imprisoned millions of his kind in them.

That he desires a chance to escape occasionally from his urban environment is evidenced by the way those who can afford to rush from the city to the open country on holidays and vacation periods. A study of what he does on those occasions reveals the strength of his urban-bred recreational habits and interests. Instead of seeking the dispersive type of activity which brings him into an intimate contact with nature, he tends to congregate at beaches, on picnic areas, at lookout points and other such gathering places, and to participate in those forms of recreation which are familiar to his everyday experience.

From evidence as sketched above, students have concluded that man's loss of intimate contact with nature has had a debilitating effect on him as a being which can be alleviated only by making it possible for him to escape at frequent intervals from his urban habitat to the open country, and that, furthermore, in order for him to obtain the maximum satisfaction out of his renewed association with nature, he must again learn how to enjoy himself in the out-of-doors by reacquiring the environmental knowledge and skills he has lost during his exile from his natural environment. This applies even to those who live in towns, villages, and rural surroundings since they have largely adopted the habits and interests of the urban civilization with which they are so closely associated.

While the introduction of an industrial economy has brought about many other changes in man's environment and living habits, the foregoing illustrations include those which appear to have had the greatest effect on him. They have in no way lessened his urge for self-expression, but have modified to a drastic extent the ways through which he has sought to gratify that urge, and they have largely forced him to seek recreation by vicarious means, as exemplified by attendance at motion-picture shows, football games, etc., rather than by means through which he is an active participant. When analyzed in the light of those characteristics which have come down to him from his early ancestors, these changes reveal many inadequacies in his present ways of life which may be partially or wholly offset through adequate provision for compensating forms of recreation.

POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS

In the above discussion an effort has been made to analyze some of the more important factors which influence individual needs for recreation. Since mass needs are an aggregate of individual needs, the next consideration logically involves an appraisal of the country's population as a whole, its origin, growth, composition, predominant characteristics, and economic and social conditions.

The number of people to be served, where they live, the leisure time they have available, their mobility and income, are factors which determine the amount and location of recreational opportunities utilized today, and give some indication of future requirements.

In 400 years a vast wilderness has become a great Nation of farms, dotted here and there by smoky cities, by remnants of the great forests, prairies, and plains of early days. Four hundred years ago the Indians saw the first immigrants, conquistadors from Spain; today we see the latest arrivals from all the continents of the globe. Four hundred years ago the Spanish explored the southwest, bringing with them Catholic padres and missions to convert the Indians. In 1607 the first Englishmen settled at Jamestown. In 1620 the ancestors of all those whose forebears "came over on the Mayflower" disembarked at Plymouth Rock.

From a handfull of white people in 1620, the population had increased to 3,500,000 at the time of the Declaration of Independence. Beginning with a narrow fringe of populated land along the Atlantic coast in 1776, containing no more people than inhabit the State of Missouri today, the young Nation pushed ever westward, until by 1853 it included the Pacific coast and the continental United States we know now. Its population had increased to about 123,000,000 by 1930. In 1940 it was estimated at 132,000,000.

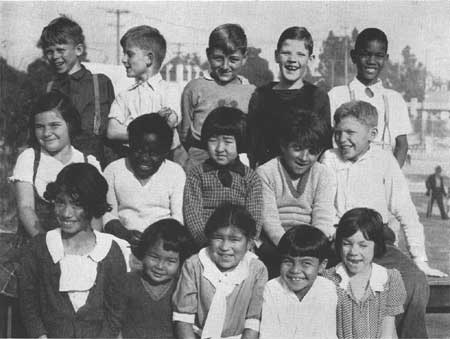

Figure 1.—The human wealth of the United States is composed of many

racial backgrounds.

This spectacular rate of growth is now decreasing. Although the greatest numerical increase occurred in the decade 1920-30, the rate of growth has been declining since 1860. This decline is due to drastic reduction in immigration in recent years, and a lowering of the birth rate which has been in evidence for nearly a century. The decline in the birth rate is noticeable principally among urban populations where higher economic requirements result in later marriages, where more women are working in commercial fields, where influences of urban living act as biological deterrents, where knowledge of birth control is increasing and where the child, instead of being as in the past a financial asset, is now an economic burden. It is estimated that if present trends continue, the population of he United States will reach a peak of approximately 158,000,000 about 1980.3 A plan of outdoor recreation must consider this coming population.

3 National Resources Committee, Population Problems, July 1938. Web Edition Note: Actually population figure for 1980 (U.S. Census Bureau) was 226,545,805; population growth has not peaked.

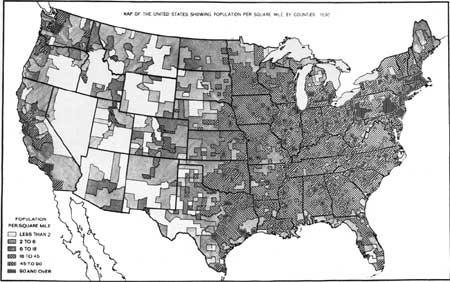

Past trends in population changes and studies of present economic conditions indicate that the principal population increases will center in the industrial sections of the East and the Lake States, the West and South Central sections of the country, and the Pacific coast. The South-Atlantic and the South, with their present populations are finding difficulty in maintaining a suitable economic level.4 Similar difficulties are being encountered in the Great Plains and the cut-over regions of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota.4 The provision for recreation should reflect these trends.

4 National Resources Committee, Problems of a Changing Population, 1938.

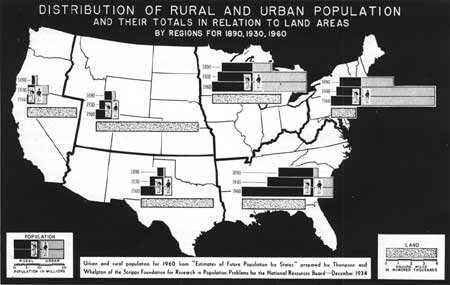

We began as an agricultural nation. The advent of the machine, however, rapidly changed our occupations and our habitat. As recently as 1890, 64.4 percent of the population was rural, but in 1930 this figure had dropped to 43.8 percent. In 1930, 90 percent of the crops were raised by 50 percent of the farmers, and it has been stated that it is quite possible this 50 percent will ultimately be able to supply foodstuffs for the entire Nation.5 The changes in occupation and habitat following the introduction of the machine have resulted in millions of people being brought into cities from the countryside, where they had formerly lived and worked under conditions of natural environment more or less in harmony with human biological requirements. In 1930, 47,000,000 Americans lived on two-tenths of 1 percent of our land, and an additional 37,000,000 lived in smaller urban communities. All these people need recreation in a natural environment as a balance to their daily lives in urban surroundings. The growth of our cities, large and small, has been accompanied by a failure to reserve sufficient open spaces within and adjoining them; and their environs have often been despoiled of their recreational value. This growth has frequently resulted in the destruction of notable historic sites. On the other hand, the development of suburbs, of satellite cities, of garden cities, is somewhat modifying the ill effects of too intensive urban development; and metropolitan, county, and State parks are beginning to complement the usefulness of city parks and playgrounds in supplying recreational opportunities.

5 Roy Helton, in a speech before the National Recreation Congress, 1938.

At the other end of the scale of population density is the solitary farmstead surrounded by hundreds, perhaps thousands of acres of wooded Ozark hills or Montana plains. If the urban dweller has too many neighbors, the rural person requires the boon of more frequent fellowship.

Figure 2. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Largely as the result of labor-saving devices, new techniques, and improved seed and stock, the output of the average farm worker has increased two and one-half times during the past 60 years. However, farm tenancy is still prevalent in many of the rural sections, and with the relative decrease in the movement of population from farm to urban centers during recent years, it is noticeable that the increase in the rural population has been more pronounced in the poorer than in the more prosperous rural sections. In general, and particularly in such sections, it is now considered very important that more attention be given to public provision of opportunities for higher standards of education, health, and recreation than has been recognized in the past.

Figure 3. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Most rural communities and small towns are not now being effectively served by agencies which provide areas, facilities, and leadership for the recreational and cultural life of the people. The leaders in the park and recreation movement, working in close cooperation with other agencies concerned with the provision of recreational services, should concern themselves with a solution of this particular rural problem. Parks under qualified leadership, and carefully located and planned with respect to the needs of rural sections, are natural centers for a great variety of recreational and cultural activities in which rural people could participate either as individuals or as groups. Particular attention should be given to the provision of wholesome recreational programs for rural youth to counteract the glamour of the city or the nearby roadhouse.

It is not possible to describe in detail here the content of the program which might be initiated on parks, but in a series of program demonstrations during the summer of 1939, 74 different activities were conducted. Music, dramatics, social games, nature and travel talks made up a varied program. Rural people love to gather in the open during the evening and the enjoyment of any presentation is enhanced by the outdoor setting. Day and overnight camping do have a strong appeal, and there is always an enthusiastic response to campfire programs. The popularity of activities naturally will be varied. In some parks, swimming, boating, and other aquatic sports will be in the ascendency, while in others picnicking, hiking and the arts and crafts will have their ardent devotees. Physical activities which have a strong appeal for the youth and young adults in the rural districts include softball, quoits, croquet, volleyball, and tournaments connected with such activities. Community days in parks, which emphasize programs suited to the whole family, are very desirable. In the long run, the adequacy of the facilities provided and the interest and ability of the leadership in a park has a great influence in determining the attitude of the people toward the park and the activities in which they will participate.

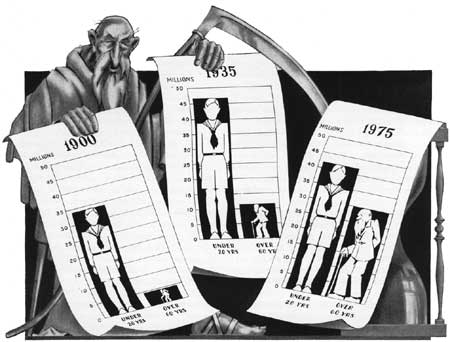

Figure 4.

The average age of our population is becoming older due to a decreasing death and birth rate. "In 1900 there were 90 persons under 20 years of age for each 100 persons aged 20 to 60 years, whereas the corresponding ratio in 1935 was only 68, and by 1975 will be about 48. Conversely, where there were 13 persons over 60 years of age per 100 persons aged 20 to 60 years in 1900, the corresponding ratio in 1935 was 17, and in 1975 will be about 34."6 These predictions are, of course, contingent upon the continuation of present trends.

6 National Resources Committee, Problems of a Changing Population, 1938.

It is not to be supposed, however, that we are "rapidly becoming a nation in wheel chairs, dependent for support on a vanishing company of productive workers. In fact, the proportion of the total population in the productive age classes, 20-64 years, will apparently be greater throughout the twentieth century than during the nineteenth. The striking changes are occurring in the two age extremes—the young and the very old—rather than in the intervening age groups."7 We must continue to plan adequately for millions of people between the ages of 20 and 64 a wide range which touches both youth and age.

7 National Resources Committee, Population Changes, 1938.

The profound changes in the age composition of the population, if they occur as present trends appear to indicate, will probably cause a shift in the recreational viewpoint. More older and fewer young people will mean a national trend toward the less active forms of recreation. Youth is inclined toward the more vigorous types of sports, is more plastic and venturesome, and consequently its range of interests is wide and varied, whereas advancing age tends to lessen people's desire for highly organized and strenuous sports, as well as their capacity for safe indulgence in them. We must, therefore, in providing for recreational opportunities today, plan so that areas and services may be modified to suit changing future conditions.

An increasing number of older people will probably mean a more widespread desire for warm weather recreation in the winter and for cool weather activities in the summer. Provided leisure time and available income permit, there may well be a gradually increasing use of the South, Southwest and Pacific coast during the winter, and a greater summer exodus from cities to the coolness of the mountains, the Atlantic and Pacific seashores, and the woods and lakes of Northern States. At the same time it is possible that more people will prefer the more leisurely pursuit of recreation through sightseeing, educational and cultural activities, and scenic appreciation. The type of pleasure for which National and some State parks stand will probably be in greater demand. At the same time, the keener appreciation of less spectacular things and the less urgent desire to explore actively which accompany the advance in years may receive greater recognition.

As a result of the severe reduction in immigration since the World War, our population is gradually amalgamating by intermarriage of races and nationalities, a process which may nevertheless require several generations for completion. The fusion will probably be less rapid in areas such as certain rural sections and certain dense urban concentrations where one nationality has congregated. The trend of Negro population is important; its rate of increase is less than the national average according to 1930 census figures.

As consolidation of races and nationalities progresses, the people of this country will become more and more homogeneous; and as the years pass, variations or dissimilarities in outdoor recreational desires due to racial or national characteristics and traditions will tend to diminish and the good qualities of each will become the general possession of all. To conserve the background of national traditions will enrich our general heritage. For this reason, notable landmarks and historic sites of the various nativities composing the American population should be preserved.

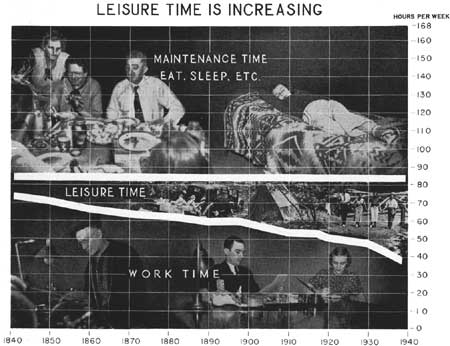

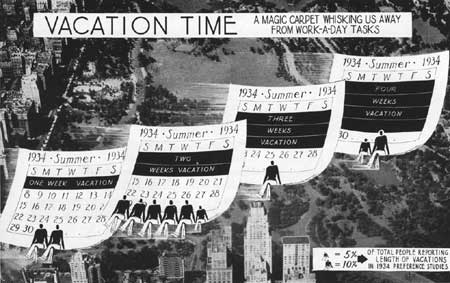

LIMITING FACTORS

The most significant trend of the past hundred years relating to recreation is the increased opportunity offered by the decrease in working hours. At the time of the Civil War, the average workweek was 68 hours, which, together with time necessary for sleeping, eating and personal care, left 16 hours of leisure per week. In 1930. the workweek was 47 hours, and leisure time had jumped from 16 hours to 37.8 Since 1930 there has been further decrease in work hours. It appears inevitable that if present trends in increased efficiency of production continue, there will be either shorter hours of work or a large percentage of the population not gainfully employed. From the view point of outdoor recreation, the 5-day week and the annual vacation with pay, both of which seem destined to become more common, are of great significance, particularly in making possible more long distance travel. Instead of taking one's vacation in the summer, there is an increasing tendency toward taking shorter and more vacations at different periods of the year. This practice allows more frequent relaxation from strain which is not only more beneficial to the individual but is also likely to result in the improvement of his work efficiency. With child labor laws, shorter workdays, longer weekends, and vacations, there will be increasing opportunities for urban people to get out into the country for recreation and for rural people to find recreation beyond the confines of their own neighborhoods.

8 From a chart by William Green in the New York Times, August 9, 1931.

The mobility of the population in the pursuit of recreation is dependent upon the following two main factors:

1. Leisure time.

2. Income available for recreation.

The distances people actually travel for outdoor recreation vary in accordance with the following factors:

1. Availability of recreational areas.

2. Availability and cost of transportation facilities:

(a) Private—automobile or group truck or bus.

(b) Public—railroads, airlines, buses, trucks, streetcars.

3. Traffic and road routes (trailways, parkways, freeways).

4. Attractiveness of route.

5. Types of recreational activities offered.

6. Costs involved in participation in activities as offered.

7. Quality of recreational facilities provided.

8. Intensity of use.

9. Publicity given the area.

10. Availability and cost of overnight accommodations on or near the area.

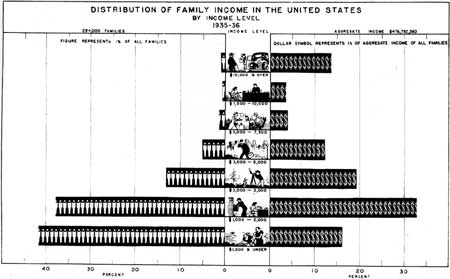

The low-income group, comprising approximately 42 percent of the total population, can spend little, if anything, for recreation travel. For this reason, their outings must largely be restricted to their own neighborhoods for all leisure periods, unless arrangements are made for low-cost transportation. This means that the use of outlying areas is confined almost entirely to those from the moderate and ample income groups. The upper income group, which constitutes less than 10 percent of the population, on the other hand, generally have longer vacations and can afford to travel extensively.

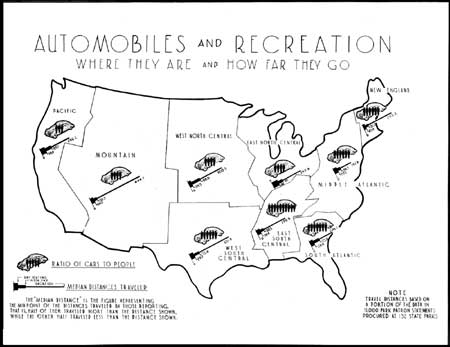

Figure 5.

As a general rule, the more thickly settled a section of the country is, the more restricted will be the range of travel for weekday and holiday outings. Here the factor of traffic conditions becomes dominant. Roads in the industrial East, for example, are congested with traffic during late afternoons and on holidays, which slows travel to such an extent that it becomes impossible to go very far for an outing and have any time left in which to enjoy it. In the thinly settled open spaces of the South, Southwest, and West, on the other hand, a man can range from 25 to 50 miles from his home on weekdays and can easily extend this to a hundred miles on a holiday. The construction of parkways, freeways, and multiple-lane highways should loosen up traffic conditions in the congested population sections, thereby increasing the radius of urban travel for these shorter leisure periods.

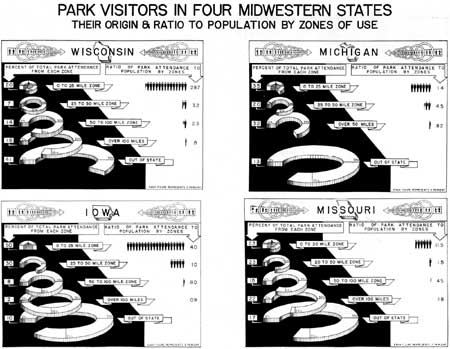

Figure 6. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

OUTDOOR RECREATIONAL TRENDS

A brief appraisal of popular forms of outdoor recreation along with an examination of newer trends in this general field, should provide additional knowledge on the recreational wants of people. A study of the policies of agencies engaged in providing this type of recreation should also be of assistance in projecting future programs, since in most instances they have been established after a thorough consideration of needs and objectives. Generally they have had a twofold purpose in mind. They have sought to preserve exceptionally fine scenic resources for future generations, and to make these resources available for the enjoyment of the present generation.

This policy, as it affects the use of national parks, is summarized in the Administrative Chapter. Briefly, it states that, considering recreation in its broadest sense, the field of national parks is limited. The parks cannot attempt to provide recreational facilities of every type. Justifiable forms are those to which the aesthetic values of nature contribute an essential or vital part of the enjoyment. State park policies, also discussed under administration, vary as between States, but in general subscribe to preservation as a wise principle while acknowledging the need to serve a wider range of interests than is practicable in national parks. Local park systems of necessity have had to give first attention to handling the mass requirements of their people, but most of them have also recognized the equally important need of preserving the resources of their areas and particularly of preserving or creating beauty in the out-of-doors.

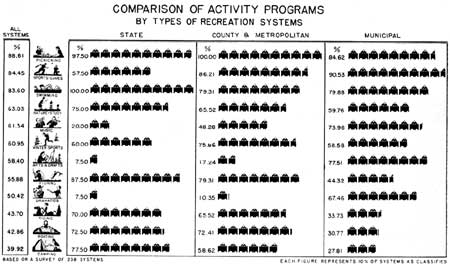

Figure 6. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

The opportunities offered by the open country for recreation are, for all practicable purposes, unlimited. Almost anything a person does anywhere for recreation, he can, if he chooses, do in the out-of-doors. There are, however, certain activities which gain in enjoyment when offered in a natural setting; others require such a setting. Probably the best way of gauging the importance of various outdoor recreational pursuits is to review the programs of recreational agencies in this field. Studies made during the past few years by the National Park Service, in cooperation with administering agencies, on attendance and use at State and local parks, reports on the uses being made of national parks and national forests, augmented by a survey of recreational preferences of park visitors, offer excellent sources of information on this subject.9

9 A list of reports consulted includes: Park Use Studies and Demonstrations, 1938, National Park Service; Activities in National Parks, reports compiled in 1936 by national park superintendents (not printed); Fees and Charges for Public Recreation—A Study of Policies and Practices, National Park Service; and Activities of Users of National Forests, a Report by the United States Forest Service, 1937.

Figure 8.

All of these studies reveal a surprising national uniformity in the range of outdoor interests and in the popularity of the various forms of outdoor recreation. In practically every report the same group of activities appears. Touring or sightseeing, fishing, picnicking, and swimming generally head the list of favorities, with camping, hiking, boating, nature study, sports and games, and horseback riding following somewhat in that order in respect to popularity. Hunting, though seldom permitted in parks, is a favorite in all interest studies and enjoys a wide participation in most sections of the country. Mountaineering, music, drama, pageantry, arts and crafts, photography, the study of astronomy, sketching and painting—these and many other activities are also included among those offered in some form or other in out-of-door settings.

Activities included in the following discussion are those in which the public have indicated a definite interest and which have been offered successfully in systems at two or more levels of government.

Figure 9. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Touring and Sightseeing. If records of expressed interest and of participation are an indication of popularity, touring and sightseeing may well be termed America's favorite forms of recreation. The desire to see things sends millions out on the highways each year. Many of this number spend their weekends and vacations traveling, stopping at one place for a few hours or a few days, then pressing on to other points. The allure of far horizons keeps them moving. They swarm to the mountains, seashores, lakes, National Parks and National Forests, to historic sites and State parks. In the winter they go south, giving Florida, the Gulf Coast and California a tourist business that has been estimated in the billions. In the summer they tend to reverse the direction, heading into New England, the Great Lakes region, the Pacific Northwest and mountain sections of the country to spend another billion or so dollars. While many purposes motivate such travel, a study of the records indicates that a large part of it is based on a desire to see the country and its natural beauties and wonders.

Figure 10. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Picnicking. Next to sightseeing, picnicking attracts the widest participation among outdoor activities. The picnicker comes to the parks (several million strong each year) with his family or with a group of families, or he joins with members of his lodge, his Sunday school class or some other organization in staging a barbecue, a fish fry, wiener roast, or a big group dinner. While he is on a picnic, he may do anything from playing catch to climbing a mountain, but to him that is all a part of the picnic. He often wants to play games, particularly if he is with a group, and therefore likes some open space near at hand. He is also fond of swimming, and for this reason likes to spread his lunch as close to the beach as possible.

The popularity of picnicking is attested by the fact that 48 percent of the preference questionnaire replies listed it as a favorite and that there were almost twice as many State park visitors picnicking, taking the country as a whole, as there were engaging in any other activity. The average for southern parks, and for local parks in all sections of the country, was smaller, but in these instances it ranked close to swimming in the number of participants. Significant too is the fact that 211 of the 238 State and local systems reporting in the Fees and Charges Study offer picnicking. It is also provided widely in national forests and in some of the national parks.

Water Sports. Among the more important activities included under water sports may be listed swimming, diving, water games of all sorts, carnivals and swimming meets, canoeing, rowing, sailing, motor boating, and regattas. The fact that more than half the visitors to recreational areas participate in one or more of these various forms of recreation is only one of the many evidences of the importance of this natural resource to people's enjoyment of the out-of-doors, both as a means of active recreation and as a component of attractive landscape. Water sports are features of most resort programs and are offered at thousands of privately operated facilities. Among park agencies reporting in the Fees and Charges Study, 219 offered swimming, 102 rowing, 75 canoeing, 52 motor boating, and 35 sailing. In the preference survey, swimming was voted the most popular of all outdoor sports, while boating was eighth.

Though not depending directly on water, beach activities may well be considered a part of any good water sports program. As a matter of fact, many who are counted as bathers seldom if ever go in the water, while actual statistics reveal that at no time does the average number of swimmers, paddlers, and waders exceed 50 percent of those in bathing suits. More than half the average swimmer's time is spent on the beach, in sun-bathing and in playing volleyball, badminton, shuffleboard, horseshoes, paddle tennis, and informal games. For this reason, beaches and adjacent playfields are seldom large enough to accommodate the demand or open space.

Hunting and Fishing. The values derived by the American public from hunting and fishing are numerous and far reaching. They have fostered a wider interest in and appreciation of conservation. The money spent for transportation, guides, and equipment has been estimated at from 1 to 2 billion dollars annually. The fact that 6,900,000 angler licenses and 6,806,291 hunting licenses were issued in 1936-1937, indicates the popularity of these sports. In addition, many States do not require a person to have a license to hunt or fish on his own property, and in some States various exceptions are made, i. e., for women, children up to a certain age, and persons over 65, for small game and predators. Exceptions are also made within certain counties.

Figure 11. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

While hunting is prohibited almost universally in parks, because of the dangers involved and conflict with other uses, fishing is recognized as an excellent park activity. The Fees and Charges Study shows that 133 State and local systems out of the 238 agencies included offer fishing. It is one of the favorite sports of visitors to national parks and national forests.

Hiking, Climbing, Packing, and Horseback Riding. These activities have been grouped together since they have certain fundamental characteristics in common. They involve the use of trails as a primary facility, take people away from crowds, and bring them into an intimate contact with nature. To many, these are the most satisfying of all types of activities carried on in the open. They particularly appeal to those of a vigorous, adventurous nature and to those who love solitude or the companionship inspired by quiet woods, towering mountains, fast-moving streams and expansive deserts.

The popularity of these sports may be judged by the fact that 150 groups with over 50,000 members now promote such activities, that 364 cities report hiking as an important feature of their programs, that attendance and use studies on national, State, and local parks list them among the popular forms of recreation offered, and that over 30 percent of those filling out preference questionnaires include one or more of these activities as a favorite. They constitute important features of camp programs and are engaged in widely by vacationists at resort areas.

Winter Sports. Among the activities included under winter sports are skating and ice games, ski running and jumping, snowshoeing, sleighing, tobogganing, and ice boating. Since they are dependent upon suitable conditions of snow and ice, the possibilities for enjoyment of these activities are limited to the northern and mountainous sections covering roughly two-thirds of the country, where precipitation and temperature are propitious.

A review of statistics reveals the growing interest in these cold weather sports. It has become so great in recent years that millions of dollars of private capital have been poured into the manufacturing of equipment, provision of facilities, and lodging for the crowds of people who flock to snow areas on weekends. Snow trains now run on regular schedules out of the larger urban centers throughout the northern section of the country. Public recreational agencies have had to give increasing attention to their winter sports activities. The Fees and Charges Study revealed that most systems in the colder regions of the country provide ice skating, skiing, tobogganing, and snowshoeing. Almost a million visitors to national forests during 1937 went for winter sports, and national park superintendents report a growing interest in these activities.

Nature Studies. While not yet a widely popular activity from the standpoint of participation, the study of natural sciences as a form of recreation is becoming increasingly important. It has long been a feature of the National Park Service program and is now offered at most of the national park and monument areas. Through this program the Service feels that a contribution is being made to the enrichment of the lives of park visitors because opportunities are provided whereby the visitor may learn about his natural environment and the laws of life. It is a program that helps to make education a continuous process, that emphasizes avocational pursuits, that stimulates the proper use of leisure time.

The Indiana State Park System now employs naturalists at six of its areas, while Iowa and Missouri have recently initiated interpretative programs on selected parks. Palisades Interstate Park in New York and New Jersey and the American Museum of Natural History have been jointly conducting an extensive museum and nature trail program for a number of years which now handles over half a million participants. The Cleveland (Ohio) Metropolitan Park System, Oglebay Park at Wheeling, West Virginia, and the National Capital Parks show examples of excellent local programs. The Fees and Charges Study revealed that 150 State and local agencies now offer nature education as a recreational activity. It is an important feature of programs being conducted by schools, colleges, recreational agencies and interest groups, garden clubs, and numerous other public and quasi-public groups. Most camping programs emphasize nature study along with pioneering and woodcraft and other activities which exploit the educational features of the natural environment. The success of this activity, so peculiarly suitable to the naturalistic area, is dependent largely on the quality of leadership and on wise planning and organization.

Music and Drama. Of all the arts, music and drama are probably the most universal in their appeal. That they lend themselves to outdoor participation and enjoyment has long been recognized, but only in recent years have park agencies realized the possibilities of these forms of recreation in developing programs of use. They are particularly important as activities on areas located within a few miles of the using public or which accommodate a large number of vacationists. Music is the lifeblood of many camp programs; it arouses drooping spirits on a hike and enlivens informal gatherings in the lodge of an evening. A campfire program is largely music. Music is also an important feature of such occasions as the Laurel Festival at Pine Mountain State Park, Kentucky, the Easter Services in Zion National Park, Indian rituals in the Grand Canyon and on reservations and, coupled with drama, it constitutes an indispensable element of historical pageants which are being staged by the score in park and forest areas.

Most music and much of our drama can be produced as well in a natural setting as inside a building and often with more satisfaction. Beethoven's Sixth Symphony the Pastoral—was inspired entirely by nature's notes, colors, and harmonies. Played in the out-of-doors, the environment should contribute to its meaning and the enjoyment derived. The Passion play is enacted in as natural a setting as is feasible with the mechanics of the play. The rural setting and the "drive through the country" in approaching Oberammergau prepares one for the fullest enjoyment of the play itself. The property man in Midsummer Night's Dream has few worries when he goes beyond the restricting influence of the "four walls."

Arts and Crafts. While arts and crafts are not as yet generally provided in outlying parks, there are examples of their popularity when so offered. Pokagon State Park in Indiana established a craft shop as a "happy solution to the problem of what to do after hiking, riding, fishing, or just loafing." It had an immediate appeal to many who here found an opportunity to ply their hobbies during their vacation. Arts and crafts are important parts of most camping programs and are offered in many local parks. The Fees and Charges Study, as an example of this, showed that they were offered by 131 municipal, 5 metropolitan and county, and 3 State park systems.

The value of these activities to a park visitor can be visualized when it is considered that any natural area offers the artisan an unlimited range of suggestions for the creation of new designs. Patterns of leaves, ferns, snowflakes, ripples on the sand and water are infinite. Shells, beetles, insects of all descriptions display excellent examples of line, symmetry, color, form, and rhythm. The hills, trees, clouds, sunsets, and large water surfaces have inspired many of our art treasures. The park then, offers a source of inspiration to the artisan. He may translate this inspiration into design either in his own or the neighborhood craftshop. The sketching and painting of birds, plants, and landscapes, and the photographing of these same objects are examples of arts which draw inspiration from the out-of-doors.

History and Archeology. Interest in these subjects as they are represented by historic and archeologic sites has grown so amazingly in recent years that certain States have become tourist centers largely because they contain within their boundaries the scenes of important American events. The task of those concerned with this phase of the recreational program has become one of protection, restoration, and interpretation. Interpretation is being carried out through museums, markers, literature, and, at important sites, an alert guide service. With the creation of the Branch of Historic Sites in the National Park Service, the preservation of American sites and artifacts and their interpretation became an important feature of the national park program. Many States have included a like responsibility in establishing conservation or park departments.

But interest in history is being extended beyond the strictly historic site and its interpretation. Pageants relating the history of a community, a State or even a region, are becoming popular features of the outdoor recreational program. Monte Sano State Park in Alabama, for example, recently staged such an historical pageant which was attended by more than 10,000 people. When it is known that this area is located in a relatively thinly settled section, and that its average daily attendance amounts to only a few hundred, such a crowd becomes additionally important as a gauge of interest in such events.

Camping. Camping is one of the most popular forms of park recreation, because it offers opportunities for vacations in the open at low cost, and the opportunity to participate in many other forms of outdoor recreation. For those interested in young people, organized camping offers a controlled situation with unlimited possibilities for education and the development of physical health. These factors are chiefly accountable for the fact that facilities for individual and organized camping are provided in many National, State, county, and metropolitan parks and forests.

Individual family camping is practiced extensively in national parks and forests and in some State, county, and metropolitan parks. Permits are issued to a family to pitch a tent or park a trailer at a designated site and to live there for a specified time. The tent sites are generally provided with a table and fireplace. Sanitary facilities, safe water supply and sometimes bathing facilities are provided by the area administrative agency. Scattered individual campsites, of necessity, have been replaced largely by campgrounds, ranging in extent from half a dozen to several hundred individual campsites.

Campgrounds have been provided extensively in the West, particularly in the public parks and forests. Their present number in the East is comparatively limited, but steadily increasing, and in the Northeast vacation camping is attaining very large volume. The few that are provided near large centers of population are heavily used, and such data as are at present available indicate that many more should be provided for vacation use.

Campgrounds are also used for informal group camping by church societies, farm women's clubs, family reunion associations, and other groups that desire to have their members camp together in a place where they may be afforded a limited amount of privacy. Their activities and leadership are entirely informal, as is their program. In these and other ways, camps of this type differ from the organized camp.

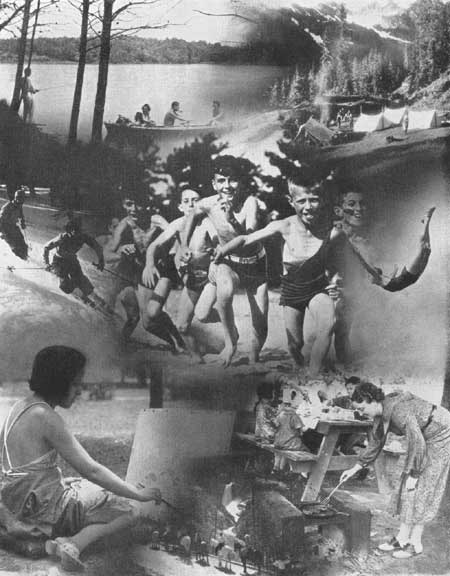

Organized camps, which were first established as private enterprises during the latter part of the nineteenth century, now are conducted in all parts of the country by a great variety of public, semi-public and private agencies which serve all classes of the population. Organized camping, which was first designed to give city children a taste of life in the woods or a fresh air outing, has now become a definite educational movement.

Facilities for organized camping are provided in many State, county and metropolitan parks. These camps meet the needs of nonprofit agencies which are normally able to provide funds for leadership and operation but who need assistance in obtaining camp sites and structures. Camp facilities on public areas make it possible for these agencies to give many children and adults the educational and recreational advantages inherent in a modern camp program. Many camps of this type have been provided during the past few years.

During that time the organized camping movement has gone forward with a strength and vigor greater than at any time in its history. New interest and activity in this field are evident in all parts of the country, and with these has come a better understanding of the opportunities camping offers for recreation, education and the conservation of human resources. We find schools, churches, stores, industries, labor unions, cooperatives, and public and private agencies representative of every phase of our national life, sponsoring new camping enterprises.

The varying objectives of this variety of camping agencies make necessary the provision of facilities of different types. However, as it is not practical to provide for all the special needs of individual agencies, it has been found that camps of three types will meet the basic needs of most camping organizations.

For the average large city organizations operating a camp from year to year for the full summer season, camps with a capacity of approximately 100 are the ideal size. This camp should have a full complement of structures with cabins arranged in small and well separated groups for housing the campers. Some of these buildings should be designed for year-round use. For agencies conducting camps for smaller groups and shorter periods, camps with a capacity of approximately 50 campers and with only the most essential structures, such as the dining hall, bathhouse, infirmary, and campers' cabins, are satisfactory. For those agencies desiring to carry out a program of primitive camping, camp sites designed for groups of approximately 25 campers should be provided. These groups will provide tents for housing the campers so that in most cases only water supply and sanitary facilities will be required. Where a number of groups of this type camp together under central leadership, such as Boy Scout troop camps under local council direction, certain minimum central facilities, such as cooking and dining shelter and storehouse, hot shower house, and infirmary, are desirable.

Primitive camp facilities, although the easiest and least expensive to provide, do not meet the needs of all camping agencies. While this type of camp provides a valuable experience for the campers and comes closest to being what is generally known as "real camping," the trained leadership necessary to carry it out on a wide scale is not at present available. In addition, many parents have not been educated to the point where they are willing to permit their children an experience of this kind. Nonetheless, there is a definite trend toward camping of this type, and most camping agencies are making it a part of their programs. Some primitive camping is considered necessary for satisfactory conduct of all organized camps.

One of the newer types of organized camping is the travel camp. Sponsored by schools, Scouts, and private agencies, young people are starting out in increasing numbers to learn at first hand about their country, its people, and their problems. These travel camps vary from an overnight automobile trip to a nearby historical area, to transcontinental tours of two months' duration. The emphasis on travel adventure and primitive camping as a major activity for senior members of scouting organizations has also played a part in increasing the number of traveling groups of young people who visit the national parks and historic sites. Private summer camps have likewise turned to recreational educational travel as an activity for older campers. These long-established agencies interested in making inexpensive travel possible for young people have recently been joined by another, the American Youth Hostels, Inc., which is endeavoring to provide hostels and promote bicycle and foot trails for youth groups.

Traveling youth groups of necessity need to make their trips at little expense, and so are unable to use the overnight accommodations so far provided in the parks. Those that are able to purchase and carry with them the necessary camping equipment make use of the free public camp grounds, but many are unable to do this.

For youth and adults who travel the parks afoot, simple, inexpensive overnight accommodations are needed which might be known as trail lodges. Facilities of this type located on public areas should be kept open to use by all groups on an equal basis and without regard to affiliation with any one organization. Radiating from these lodges, trail systems of varying length and difficulty should be provided, along which shelters and cabins would be spaced an easy day's hike apart. These would enable foot travelers to see the more extensive scenic areas at minimum expense.

Experience and existing data point to the need for more camping facilities of all kinds on public areas. Reasonable developments for individual camps, informal group camps, short-term and seasonal organized camps and for travel camping may be provided in most of our forests and parks with assurance that they will serve and be appreciated by an ever increasing number of the American People.

RECREATIONAL REQUIREMENTS

Man's needs for recreation evolve from facts heretofore presented. The 132,000,000 inhabitants of the United States have behind them a heredity of perhaps a hundred thousand years in natural surroundings modified by a present environment much changed a specialized occupation, and for most, a crowded city home surrounded by the good and bad results of a machine age. Leisure time is known; 50,000,000 can scarcely afford the price of trolley fare; some can girdle the globe. Accurate figures on limited studies of recreational habits have been presented.

There is sufficient information on what man enjoys in the out of doors. There is some reliable information on what he needs. The kind of areas and their desirable location are determinable. Any standard yardstick on the acreage and number of areas necessary is impossible.

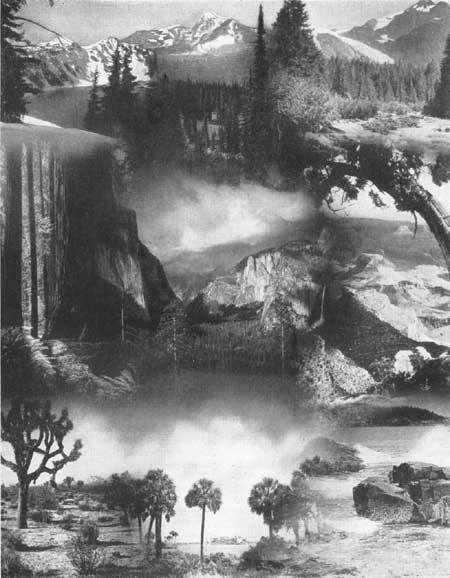

Tastes in natural scenery have infinite variety. To some, the word "scenery" brings to mind towering mountains, deep gorges, and precipitous canyons. To others it conjures up mental pictures of the slumbering tangled jungles of a delta swamp. To still others it means peaceful hills where woodland and stream adjoin agricultural land. Death Valley, below sea level, and the high altitude of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, ocean-beach expanses and tiny rivulets, dense forests and vast reaches of the great plains, the far-away wildernesses, and the nearby pastoral landscape—all these and more are types of settings necessary to gratify the desires and needs of all of our population for outdoor recreation.

Appreciation of scenery is not governed by extent of leisure or limitation of pocketbook. To gratify the desires of all the people would require the combination of mountain, seashore, forest, and plain available within reach of all. Fortunately, actual needs as known today may be more easily met.

The following are representative of the items which should be given consideration in the selection of recreational land.

LAND FORMS—Mountains, hills, gorges, cliffs, mesas, buttes, bluffs, dunes, moraines, craters, lava beds, caves, plains, etc.

VEGETATION—Forest, prairie, savanna, meadow, swamp, marsh, bog, desert, alpine, subalpine, subtropical.

WATER—Oceans, lakes, streams, waterfalls, springs, geysers, and beaches.

HISTORY—Areas containing sites, relics, and other evidences of ancient peoples. Area, structures, and routes of travel directly associated with early Spanish, French, British, colonial, and Indian history of this country, and with the history and traditions of the United States as a Nation.

PALEONTOLOGY—Areas containing material evidences of the life of past geological periods as shown by fossil or other remains of animals and plants.

WILDLIFE—Areas consisting of various combinations of the above, as habitats for native wildlife.

The closer these advantages are to people, the greater will be their use; hence, larger investments are logical close to population concentrations. Sorely needed are miles of wooded stream banks enclosing unpolluted, unsilted waters, alike valuable to the automobile sightseer, fisherman, bather, boatsman, hiker, and picnicker. The green valley and the wooded hill, the tiny creek, and the wild flower all should be common heritage. Open highways, unfolding peaceful countryside unadorned by shoddy hot-dog stands and blatant signboards constitute a valuable asset.

And this country can afford to preserve its irreplaceable objects of outstanding worth—the giant redwoods, Independence Hall, the trackless wilderness of the Olympic peninsula, and the wonders of the Yellowstone. Objects of historic and archeologic note are inspirations of irreplaceable value; great expanses of resort country in the mountains, by the sea, around the Great Lakes, have economic worth in addition to their great potentiality for physical benefit and their capacity for giving lasting pleasure.

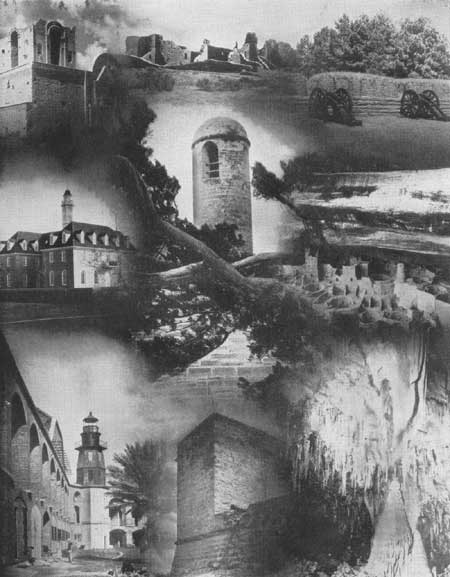

Figure 12.—The United States is rich in recreational resources of the land.

The urban population needs raw materials, food supplies, and space to live, work, and play. The living and play space has been generally neglected. The great need is for public open space in and near the urban centers. These open spaces should bring the country into and through the urban area, in the form of wide parkways tying together a system of large open areas.

For the 42 percent of our population who can travel no appreciable distance from their homes, needs must be met close by. Too, the weekday recreational facilities for all our people must be within a few miles. This means that such recreation for the city must be within municipal environs. For rural and sparsely settled sections, this provision of close-by recreation necessitates its combination with other uses. For close-by recreation, location rather than scenic excellence is the first consideration—the best land which is properly located should be chosen. Topographic suitability for playfield, picnicking, natural or artificial bathing facilities is very important. Here a great part of our public recreational provision should take place. Land costs, inevitably high, coupled with need for proximity to use, will dictate selection of a larger number of smaller areas.

On weekends and holidays, over half the people can travel appreciable distances beyond their neighborhood for recreation. While location as convenient as possible to the population to be served is important in area selection, scenic qualifications and recreational potentialities should be great. Larger areas are needed in which a concentrated use area with such facilities as a picnic area, camp ground, eating place, swimming place, or playfield may be located adjacent to an expanse of natural land. Here, distinction of area is of primary importance, a wider distance latitude being allowable. To put such areas even within 50 miles of most of our population will require expansion of existing recreational systems. In sections of dense population the number of areas will need to be increased. This will mean utilizing existing public lands to greater advantage and the acquisition of additional areas.

Vacation lands need to be the best lands available within the wider range of location requirements. A relatively small percentage of our people take extended vacations away from home. Some of these can afford more luxurious private areas, and some do not seek the out-of-doors during vacation periods. The quality of an area is the principal consideration in selection. Here people may reach ocean beaches, mountain heights, the cool of the northland in summer, the quiet of a wilderness area, the inspiration of an historic location.

We must have unspoiled scenic areas, retain irreplaceable natural scenes, preserve the character of the superlative. Vast vacation lands, public and private, are among our most important assets. Parks, forests, wildlife areas, large resort sections. all have cultural, social, and financial values to this generation, and are a heritage we can and should pass on to future generations. Needed are both the area for constant day-by-day use and the spot to be visited once in a lifetime.

In addition to the physical requirements of the people, enumerated above, we must concern ourselves with the provision of opportunities for participation by the entire population in wholesome recreation through cooperative, intelligent planning. Such planning must endeavor to effect a larger measure of coordination between the private and public agencies concerned and more fully enlist the voluntary effort of the individual.

Cognizance must be taken of the vast increase in and growing importance of commercial recreation. Education can play an important role in promoting intelligent choice and appreciation of the various forms of recreation.

Figure 13.—History and archeology are important aspects of a recreational program.

Figure 14.—Wildlife—An invaluable recreational resource.

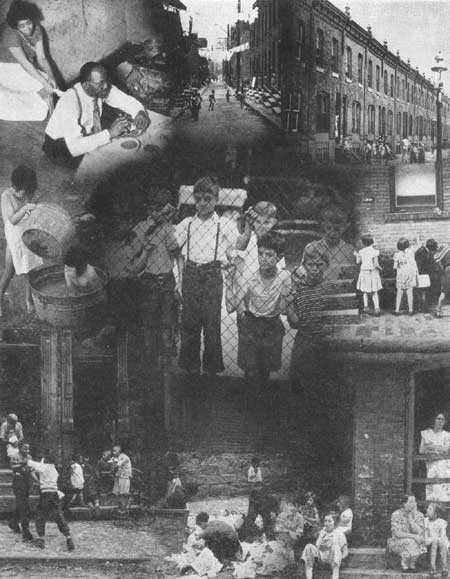

Figure 15.—The human wealth should not be forgotten....

Figure 16.—Opportunities for healthful recreation conserve the human wealth.

The following recommendations, selected from the general recommendations of the White House Conference on Children in a Democracy and dealing with the recreational needs of children, also reflect the needs of adults:

1. The development of recreation and the constructive use of leisure time should be recognized as a public responsibility on a par with responsibility for education and health. Local communities, States, and the Federal Government should assume responsibility for providing public recreational facilities and services as well as for providing other services essential to the well-being of children. Private agencies should continue to contribute facilities, experimentation, and channels for participation by volunteers.

2. Steps should be taken in each community by public and private agencies to appraise local recreational facilities and services and to plan systematically to meet inadequacies. This involves utilization of parks, schools, museums, libraries, and camp sites; it calls for coordination of public and private activities and for the further development of private organizations in providing varied opportunities for children with different resources and interests. Special attention should be directed toward the maximum utilization of school facilities for recreation in both rural and urban areas.

3. Emphasis should be given to equalizing the opportunities available to certain neglected groups of children, including:

Children living in rural or sparsely settled areas.

Children in families of low income.

Negro children and children of other minority groups.

Children in congested city neighborhoods.

4. Public and private organizations carrying responsibility for leisure-time services should assist and cooperate in developing public recognition of the fact that recreation for young and old requires leadership, equipment, and trained personnel.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

park-recreation-problem/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 18-May-2016