|

National Park Service

A Study of the Park and Recreation Problem of the United States |

|

Chapter IV:

Administration

|

|

SHORES LIKE THIS DESERVE PRESERVATION Point Lobos State Park, California |

PARK AND RECREATION ADMINISTRATION is construed to include all those means and methods by which park and recreation policies are established and properties are selected, planned, developed, operated, and maintained. The essential elements of it are as follows:

1. Organization.

2. Planning and development.

3. Operation and maintenance.

4. Organization and encouragement of use.

5. Personnel.

6. The budget.

7. Public relations.

8. Interagency coordination and cooperation.

ORGANIZATION

The basic features of any public administrative organization are normally prescribed by legislative enactment or charter. It is perhaps needless to say that for all the wide variations to be found in National, State, and local park administrative organizations, the principal objective is to provide instrumentalities through which the whole administrative task may be performed efficiently and economically and which will be reasonably responsive to the desires of the public. Our examination of the organization phase of the subject of administration proposes to proceed from an analysis of the machinery and the manner of its functioning, of what is probably the most elaborate and diversified park administrative organization in America—the National Park Service—and to ascertain, as impartially as possible, to what extent its machinery and methods are adaptable to the requirements of State and local park administration, and to what extent the different nature of their problems requires variation from its pattern.

The National Park Service. Of all the many agencies, National, State, and local, which administer lands used for recreation, the National Park Service administers a greater extent of lands set aside purely for that purpose than any other. Its administrative problems embrace all, or virtually all, of those found by other recreational agencies. Without having to be partisan about it, or to assert that its administrative machinery represents near perfection for its purpose, it is reasonable here to examine that machinery and the reasons for the existence of its various parts, and to determine to what degree its organization and procedure meet the requirements of its responsibilities and to what extent it may be adaptable to the requirements of other agencies whose chief concern is likewise the management acquisition, development, and operation of recreational areas, whatever their special character may be.

The National Park Service is a bureau of a Department which, while known as the Interior Department, is increasingly becoming, in fact if not in name, the Conservation Department of the Federal Government. Associated with the Service in the Interior Department are such other bureaus as the Fish and Wildlife Service, Grazing Service, Mines, Reclamation, and Geological Survey, each of which is importantly concerned with conservation in one phase or another. Thus there is in the Federal Government a relationship, within a single Department, with a group which, though lacking forestry, is in most respects analogous to that found in the conservation department or department of natural resources type of administration now established in many States.

Although new activities in connection with the CCC, ERA, and PWA have brought into the Service organization during the past seven years many employees without civil-service status, all persons employed by the Service with funds appropriated directly to it, from the Director down, are under civil service. Employees paid out of CCC funds are scheduled to be placed in Civil Service status under legislation passed by Congress late in 1940.

Under the Director and his Associate Director the Service organization is divided into branches which in effect constitute three major groups. One group comprising the Branches of Plans and Design (Architecture and Landscape Architecture), Engineering, and Recreation, Land Planning and State Cooperation—is chiefly concerned with the planning side of the Service's job. Another group of three branches constitutes the protection, interpretation, and research staff. These are the Branch of Research and Information, which includes the Naturalist and Museum Divisions, as well as wildlife technicians; the Branch of Historic Sites, concerned actually with both historic and prehistoric research and interpretation, and with phases of protection and development that involve historic areas; and the Branch of Forestry, concerned primarily with protection of the forest resources of the national parks, monuments, and other areas under Service administration. The third group is concerned with acquisition of lands, the various legal phases of the Service's activities, and field and office operations. The Office of Chief Counsel handles the first two activities, the Branch of Operations the last. The scope of the Branch of Operations is indicated by its several divisions—personnel, audit, operators (concessionaires).

Each of these groups and branches is, of course, subordinate to the Director; they are his advisers; they relieve him of the great mass of detail required to be handled in the course of developing and administering a far-flung, many-unit system; but ultimate responsibility for the functioning of the whole group rests upon him.

Like most governmental agencies, the National Park Service has evolved its administrative organization to meet changing and increasing responsibilities. When it was established in 1916, it administered 16 national parks and 21 national monuments, almost all situated in the Far West. At a time when the Branches of Engineering and Plans and Design were called upon to prepare the detailed planning of roads, buildings, etc. for these areas, both branches were located in San Francisco. So were most of the rest of its technical personnel.

During the past decade the number and kind of areas under administration by the Service have increased tremendously. With the transfer of a number of historic sites from the War Department and of National Monuments from the Forest Service, and establishment of a number of new scenic and historic parks and monuments east of the Mississippi, it has direct administrative responsibilities in nearly every State. These circumstances have forced the Service to follow the example of many other Federal agencies by regionalizing its work, and by passing out to its regional organizations a great part of the duties and responsibilities formerly handled by its Washington office.

Each of its regions very largely reflects the Service's Washington office in its organization and its functions, so far as those functions have been made subject to regional authority. Detailed planning is now performed almost wholly in the regional offices and on the several types of administrative areas, with only major plans and master plans now subject to the Director's approval. To a much greater extent the task of the technical branches in Washington has become that of assisting the Director in the formulation and enforcement of Service policies.

Individual areas under the regional offices, depending on their extent, importance, and amount and variety of use, tend again, in greater or less degree, to reflect the regional and Washington office in type of organization and in the varieties of technical service engineering, landscape architecture, forestry, wildlife, etc. available in meeting the special problems of the areas to which they are assigned. Wide administrative latitude, within the framework of regulations, rests with the superintendents of the national parks and the custodians of the national monuments.

Technical and administrative groups or divisions in each regional office bear the same relationship to the regional director as do the branches in the Washington office to the Director; the same is true of the relationship of park and monument staffs to those in charge of the areas.

It will be noted that, in its problems of selection, development and administration, the National Park Service leans heavily on technically trained employees in a large variety of fields. A breakdown which will indicate the diversity of specialization employed will perhaps be illuminating.

In the Branch of Engineering are specialists in civil, hydraulic, electrical, sanitary and highway engineering. Because of the Service's large concern with historical structures, and specifically with their repair and restoration, one regional staff includes an architect who is a specialist on period architecture and construction methods. In the wildlife field, it utilizes the services of Fish and Wildlife Service employees assigned to it, who are specialists in the fields of botany, ichthyology, zoology, ecology, and wildlife management. The Branch of Historic Sites, concerned likewise with prehistoric sites, includes archaeologists as well as historians on its staff. The Branch of Research and Interpretation employs geologists, whose services are also important in connection with at least two types of developmental work investigation of dam sites and sources of potable water supplies and specialists in modern museum technique and in nature education.

During the present administration a number of special tasks have been laid upon the Service, which are germane to its primary purposes, and for which, in consequence, one branch or another, at least in some degree, was specially equipped. Thus the Historic American Buildings Survey, a P. W. A. project, was naturally allocated to the Branch of Plans and Design. The Historic Sites Survey, authorized by Congress in 1935, was as naturally assigned to the Branch of Historic Sites. The Park, Parkway and Recreational-Area Study, authorized by Congress in 1936, was assigned to the Branch of Recreation, Land Planning and State Cooperation, which has also had immediate direction of the CCC program assigned to the Service. The latter is preponderantly a matter of cooperation with the States and their subdivisions in the development of parks and other recreational areas. The same branch supervises the Service's emergency relief projects.

Although the Service finds it necessary to employ sanitary engineers for preparation and review of designs for sanitary facilities, it has had a long-standing inter-bureau arrangement whereby the Public Health Service provides final technical review of all such projects. And since 1925, all major park and parkway road construction has been handled by the Bureau of Public Roads, in the Department of Agriculture and its successor, the Public Roads Administration in the Federal Works Agency. Reciprocal arrangements with the United States Forest Service in connection with forest-fire detection, prevention, and control have been in effect almost from the beginning. Frequent and repeated use has been made over the years of the special services and scientific knowledge and counsel obtainable from other Government agencies regardless of the department in which they have been located. As a matter of fact, it has been the fixed policy of the Service to avoid extension of its own organization in any field in which satisfactory service was available from already existing agencies of government.

The functions of administration, in the case of a park and recreation agency, have been briefly summarized. Let us briefly indicate the way or the means, by which the organization described actually performs those functions.

The first on our list, it will be remembered, are planning and development. The planning function, of course, is "double-barreled," involving selection as a phase of land planning, and area planning for protection and use.

The first, involving careful examination, and appraisal of areas proposed for some national status, is one of the numerous responsibilities of the Branch of Recreation, Land Planning and State Cooperation, which, however, calls upon the landscape architect, the forester, the naturalist, the historian, and the archaeologist for assistance in uncovering and evaluating the qualifications upon which final decision as to status must be based. For many years, the process of growth in the Federal park system was one of approval of or resistance to advocacy of individual areas, with examination of them largely the part-time task of one man. Congressional legislation establishing the Southern Appalachian Park Commission, which undertook to discover an eastern area deserving of national park status, and which recommended three, marked the first major step toward a different approach. With its standards of selection well established, and with the disposition of Congress ordinarily to protect those standards—or of successive Presidents in those rare cases in which Congress has yielded—the Service has adopted the more sensible method of seeking out and endeavoring to add to the system areas that meet its exacting standards.

While the process of selection now as always rests primarily on Service appraisal and recommendation, actual establishment of national parks, whether of the scenic or the historic type, continues to rest with Congress, and of national monuments with the President.

While general policies as to operation and maintenance are of course established by the Service, responsibility for establishment and enforcement and interpretation of those policies in the light of the special requirements of any individual area rests on the man in charge of it. His is the task of seeing that the public is handled satisfactorily, and that Service regulations are met by the public, the park employees and those who operate the hotels, restaurants, transportation and other "utilities" which must be supplied in order that the public may derive the fullest enjoyment and benefit from their use of the area. Periodic audits of his books, perusal of the reports he is required to submit, and fairly frequent visits by administrative representatives of the Washington or regional office provide the checks found necessary in any such far flung organization, on which judgment as to the competence of his performance is based. As previously indicated, responsibility, under the Director, for conduct of the normal tasks of field administration rests with the Branch of Operations.

The meager appropriations to the National Park Service during the early years of its existence, and the absolute necessity of providing better accommodations to park visitors than had been available previous to the establishment of the Service, resulted in adoption of a policy under which private capital was permitted and urged to construct and operate hotels, lodges, restaurant facilities, transportation, etc., under long-term contracts.

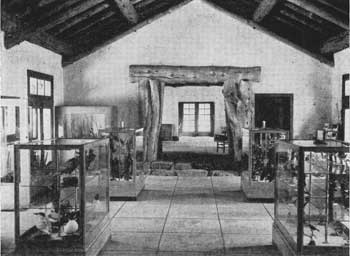

While the uses to which national parks and monuments might properly be put have been limited by the character and purposes of the areas themselves, interpretation and use within those limits has been a steadily growing concern of the Service much enlarged by its expansion into the field of history and prehistory. The great objective of the Service has been that people may not only see but may better understand what they see, whether it be a glacier-carved valley, a giant forest, the site of a crucial battle, or the council chamber of a tribe long since returned to the dust. Thus, it has established a museum program with well defined policies which are directed toward making the program effective and toward preventing museums from becoming repositories of unrelated or insignificant exhibit materials; and through constant study and research it has developed techniques which are constantly gaining in effectiveness.

Research on matters of wildlife protection and management, on methods of nature education in the out-of-doors and of relating museums to such educational activities, on development of effective signs and markers in preservation and display of historic and prehistoric structures, on the philosophy and methods of imposing fees and charges—these suggest the varied fields in which the Service carries forward the work of research on which its policies and practices must be based.

As in the case of any public or private agency, the public-relations program of the Service is a joint responsibility shared by every employee who has occasion to come in contact with the public, by whatever means, from the Director in Washington to the ranger in the park or monument. Understanding of the Service's work, its purposes, and its policies is promoted by all the means available to it—public addresses, illustrated talks, motion pictures, exhibits, the supplying of news and articles to newspapers and other publications, etc. within the limits imposed by available personnel and funds.

Even if it were not sound administrative practice, the Service would be compelled, as most publicly supported agencies are compelled, to prepare each year a detailed budget setting forth its needs of funds for the next fiscal year. Cleared through the Department and the Bureau of the Budget for consideration by Congress, it is then, of course, subject to congressional action and congressional modification. While Federal appropriations to a bureau are made in such a way as to allow some latitude with respect to changes in individual items of the detailed budget, and even for transfers of funds from one area to another, each park's detailed budget guides its expenditures, subject to change only with the Director's approval. Such a system necessitates the most careful advance planning and anticipation of future needs, and adherence to it both compels an orderly spending procedure and tends to prevent neglect of the vital needs of one area for the benefit of another.

State Administrative Organization. Although in the Federal Government coordination of conservation and recreational activities, particularly in the provision of recreational facilities, is far from adequate, the bad features of this situation are widely recognized. The necessity for close association of conservation and land holding agencies for effective coordination of their activities is indicated both by the results, in duplication of organization and effort, wherever, at any level of government, such an arrangement is not provided; and, on the contrary, by increased effectiveness in most cases where it is.

The possible scope of such an association of agencies in this field is indicated by the following fields of activity which are allocated to departments of conservation in one or another of the States: parks and recreation, forestry, wildlife, inland fisheries, salt-water fisheries, geology, soils, type mapping, reclamation, entomology, engineering. Taking simply the field of parks and recreation, it may be seen at a glance that a division concerned primarily with this field may, and probably will have occasion, from time to time, to call for special services on almost any other in the group. So, in fact, would forestry and wildlife, and in lesser degree, others in the list. The virtues of such close association in a single department, manned by competent and conscientious personnel, are such that it is earnestly recommended to every State.

Though State departments of conservation are subject to a number of individual variations in set up, and to varying degrees of inclusiveness, they fall into two general classes which may be referred to as the commission type and the executive type. The former is characterized by having a commission, usually gubernatorial appointees; a director, at least nominally chosen by the commission; and three or more divisions or branches, each headed by a division chief. The executive type, exemplified by New York, Tennessee, California, Alabama, and others, differs only in that the commission is either lacking or, as in Tennessee, is an advisory group, and the executive in charge of the department is appointed by the governor. In either case the burden of the whole undertaking rests primarily upon this executive. For that reason it seems advisable to consider briefly the qualifications most desirable in a person selected for such a position, which has become one of the most important in State government.

Genuine administrative ability may be taken for granted as a sine qua non for any director of conservation if his work is to be successful. In addition, he should certainly possess profound convictions as to the need and value of a broad, well-balanced policy of conservation of natural and human resources; a good, general understanding of the scope and purposes of each of the important conservation fields, and a genius for impartiality toward them; an appreciation of the contribution to be expected of and sought from the specialists in each of these fields; and the ability, particularly in connection with land-use planning, to weigh conflicting claims for use, and decide them on the basis of the greatest long-term public benefit.

It is believed to be unnecessary that a person in such a position be an expert or specialist in any phase of conservation. In fact, that might be definitely undesirable, since it is difficult—though of course not impossible—for a person so qualified to maintain that balance of impartiality so desirable in any person so placed.

In addition to what has already been said, the wholly successful director of conservation must be something of a crusader. His is a task, the performance of which is bound to affect profoundly the well-being and happiness of the citizens of his State and other States, both in the present and in the future. His great problem is that of combating the lethargy of the indifferent and the desire for immediate advantage of the selfish exploiter. Thus his convictions, instead of being academic, have to be backed by courage, initiative, energy—they must have backbone.

Granting the desirability of a truly inclusive conservation or natural resources department as one of the major branches of a State government, the question then may be asked: What are the advantages or disadvantages of the commission type as opposed to the executive type?

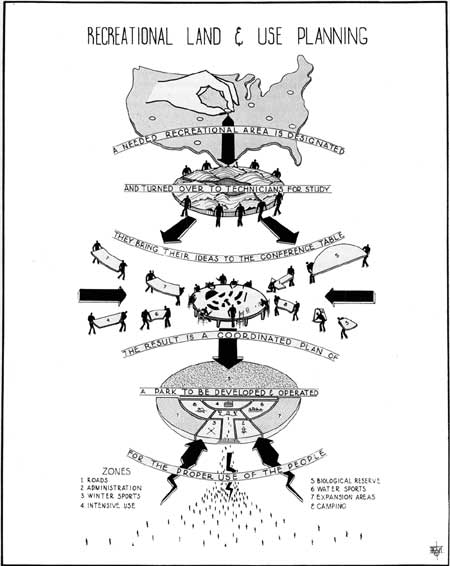

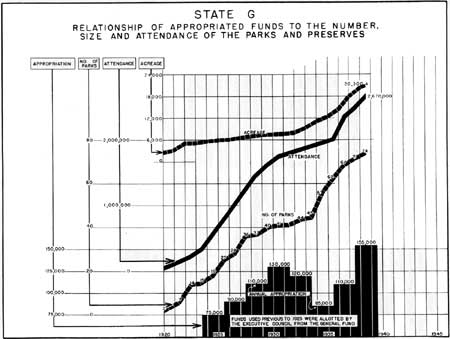

Figure 23. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Let us examine a few examples of these two types. The State of New York has long been active in the field of conservation and has spent immensely greater funds in support of it than any other State. Its organization is of the executive type—a commissioner, appointed by the Governor and confirmed by the Senate, has general direction of park, forestry, water-power, and fish and game activities. His are both the major administrative decisions as well as the major decisions on policy. Either may be made quickly, without having to await consideration by any other policy-making group. That it works and works well in New York is due principally to two factors. The first is that over a long period the governors of New York have appointed exceptionally able men to the office of conservation commissioner. The second is that the staff of the department is permanent and competent, employed under civil service and consequently not subject to removal for political reasons.

In addition, the long and efficient record of the Department has been such as to give major policy a degree of stabilization not found in States still new to the business of conservation. Thus, were a conservation commissioner inclined to make a major change of policy, long informed public opinion would tend at least to require sound justification for it.

Unfortunately, only a few States have succeeded in establishing civil-service employment. Largely because of that fact, the conservation commission form of organization has many ardent advocates. Though such commissions are appointed by governors, such appointments are usually for definite and fairly long terms and are staggered in such a way that normally not more than one member's term expires in any one year. Length of service gives an opportunity to acquire mature judgment through acquaintance with existing policies and practices; and men who might be inclined to "upset the apple cart" are usually in the minority, restrained by other and more experienced heads. Such a set-up is, of course, not actually wholly free from political influences of undesirable kinds, but practice has shown that it is likewise a stable type of set-up and that it provides a pretty fair degree of continued employment for proved and competent personnel.

In any conservation department organization it is important that park and recreation activities be established as coordinate with forestry, fish and game, and other divisions normally found in such departments, rather than subordinate to any one of them.

Because parks and recreation in many States gained recognition as a legitimate feature of a conservation program considerably later than fish and game or forestry, it has often been established as part of one or the other of these functions. That has been particularly true in the South—Florida, Mississippi, South Carolina, North Carolina, and others, where it has been placed under the forestry authorities. New Hampshire, Vermont, Wisconsin, and Montana are examples in other parts of the country. Frequently the attitude of the State foresters toward this new activity has been excellent, as has that of fish and game authorities in other States who have assumed responsibility for parks. Increasingly, however, as new conservation departments are established, it is given a coordinate place in the group of functions assigned to the departments, because it is a distinctive and specialized field, yearly growing in importance.

In most States the same relationship between central office and area administration exists as was the case in the National Park Service until 1937. In a few, however, extent of territory and number of areas has compelled or resulted in an arrangement more or less analogous to the regionalization then put into effect by the Service. New York, nearly a decade and a half ago, established a group of park regions, which now total eleven, of which ten have commissions of three to ten members, each headed by an executive officer, and each possessing a large degree of autonomy. These are united in the State Council of Parks which, subject to control by the Commissioner of Conservation, decides those limited major policies and administrative questions not delegated to the regional commission. Successor to a considerable number of local and independent and, as far as appropriations were concerned, competitive commissions, the Council now coordinates the budgets often of the regions and presents a single unified budget for the entire group, thus halting competitive pressure for funds before submission to the Commissioner, the budget officers, the Governor and the Legislature.

Michigan has established nine park districts, and California four, each containing groups of several parks, and each exercising powers of varying extent delegated to the executive officers who head them.

It was noted in the discussion of National Park Service organization that extent of territory, number and variety of areas, and the variety of problems encountered, compelled organization of the Washington office and the regional offices into a number of branches and divisions respectively. While most States face some or nearly all the problems in connection with administration selection, development, operation, maintenance and use—it is manifestly impossible, even if it were desirable, for most States even approximately to duplicate that organization. Yet, it is equally apparent that any State administering a reasonably extensive and adequate system can perform its task satisfactorily only if it is in a position to avail itself of such specialized services as are supplied by those branches.

Selection of areas requires the services of those who can acceptably appraise scenic, scientific, historic, prehistoric, and active recreational values and who can envision the extent and kind of development and protection an area will require. For any area, planning that is genuinely skilled and expert, both of individual structures and of their relationship to each other and to the roads, trails, and utilities that are required, is essential and can be supplied only by those who have been trained by education and experience for the task. Those services which are supplied in the National Park Service by the Branches of Recreation, Land Planning and State Cooperation, Plans and Design, and Engineering, are equally essential in the State park administrative organization, and for most of them on a full-time basis. The need for architectural, landscape architectural and engineering staffs appears now to be generally recognized and admitted. So, of course, is the need of properly equipped operating and maintenance personnel, although the necessity of bringing this group of men—the men who have to make the thing work—into consultation in connection with all phases of planning is still given too little recognition, to the ultimate greater cost to the State.

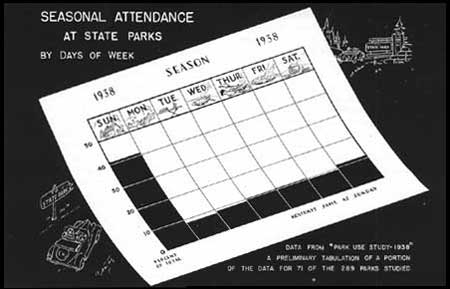

Somewhat less recognized is the need of the services of such persons as the historian, the archaeologist, the forester, the wildlife technician, the geologist, the ichthyologist, the botanist, and others, whose knowledge is valuable and necessary at every phase of the park task, from selection to ultimate use. In New York State, for example, the State Council of Parks some 10 years ago recommended transfer of its numerous historical areas to the Department of Education, and in default of such action largely continues to look upon these areas as a collection of fifth wheels in the State park system, but not belonging to it. Yet, New York has, and has thus far missed an opportunity for, an outstanding historical program, one which would add distinction to its work in the State park field if properly organized and directed. The Empire State could establish the equivalent of the Branch of Historic Sites in its park and monument set-up to its own profit and the profit and inspiration of its own people. Equally, in many States, the urge to provide more and more facilities for the picnickers, the campers, the swimmers, the golfers, has kept administrative eyes on these things to the greater or less exclusion of other recreationally valuable features; such as the geology, the botany, the wildlife and other assets of their properties. In one leading park State one may go into a State park and paddle or swim in a lovely lake without ever seeing or hearing anything to indicate that a glacier formed it; in another enter a museum in which those exhibits that help to interpret its natural and human history are obscured by a miscellaneous potpourri of unrelated material. It is thus a failure either as a park museum or any other kind. And in virtually every State it is possible to enter almost any park on a week day, even in summer, and find it almost deserted and its expensive plant idle because there has been little or no attempt to organize and lead use during those periods when use is most pleasant because freed of the pressure of great crowds. In a few alert and energetic States it has been amply proved that where such planning and organization and leadership are provided through competent and trained personnel, the usefulness of park facilities can be gratifyingly increased, and far greater interest aroused in those natural or historical features which characterize every wisely selected State park. And it can be done without application or even suspicion of either regimentation or compulsion.

All this may be interpreted to indicate that almost any State would benefit by careful exploration of the possibilities of expanded usefulness for its park and related properties, and by employment of personnel qualified to develop or promote those possibilities. Those States which lack funds with which to provide full-time employment for qualified personnel not available from some closely associated agency—such as another division in a department of conservation can often employ it on a part-time basis or can obtain it at little or no cost from a State university or even one privately endowed. By whatever means it may be obtained, and whether on full-time employment, part-time employment, or any other basis, every State needs to do its utmost to assure the most expert handling of its problems that the means at its disposal will permit.

The county, the metropolitan district, and the city, with some exceptions, come into the conservation-recreation field, only through possession of parks and playgrounds. Their administrative organizations logically reflect this situation in the park boards, park commissions, and park commissioners, variously appointed or elected, which have been created to handle their park and recreational problems. Their main functions—selection, planning, development, operation, public relations, research, preparation of budget, etc. are essentially the same as those of State or Federal Governments, and require as expert handling.

Major Functions of Administrative Organizations. In view of the emphasis given to proper selection and proper planning of park and recreation areas, to businesslike and efficient operation, and to proper budgetary procedure, it is becoming difficult to remember that only a few years ago many agencies, particularly those of the States, operated largely on the assumption that a State park needed no planning; that it was just there and folks could come in and use it; that administration of a State park system required no particular special qualifications; and that the expert in natural history, or history, or landscape architecture was unnecessary.

Improved as the situation is today, many advances toward accomplishment of the park and recreation administration job remain to be accomplished. The following discussions of the major functions of park administration are offered in the belief that they will help to broaden the concept of that job and its requirements.

SELECTION, PLANNING, AND DEVELOPMENT

Selection, planning, and development, whether of single areas or systems, must be based on some sort of policy, expressed or understood, if it is to be anything but a haphazard and disordered process. Comparatively few States, unfortunately, have attempted to formulate in specific terms those principles and policies which are to govern the whole process of planning and development, including the first step, that of selection. Unfortunately, also, areas selected and the quality of development given them in many instances all too well illustrate the consequences of lack of policy.

Because they indicate, in varying degrees, the scope of such statements of policy, there are reproduced here those formulated for the States of New York and South Carolina.

That for the State of New York was formulated in 1929 and 1930 by the State Council of Parks, and is probably as comprehensive as any that has been issued by a State. Headed Principles Governing the New York State Park and Parkway System and Rules for the Extension of the System, it reads as follows:

PRINCIPLES GOVERNING PARKS. The State is committed to the development of a unified park system developed on a regional basis. There are ten park regions including the forest preserve region. These park specifications apply to all regions except the forest preserve, the development of which is governed by totally different considerations. The State program for each region is based primarily upon scenic attraction and recreational needs. An even geographical distribution of "a park every 50 miles" or "a park for every county" is manifestly impossible on account of scenic, recreational and other requirements, and because it is fundamentally unscientific.

A park site should possess both conspicuous scenic and recreational value, or at least some scenic value and very unusual recreational possibilities.

By conspicuous scenic value is meant rare natural scenery which is unlikely to be preserved for enjoyment by the public of this and future generations if the property remains in private hands, and which is sufficiently distinctive to attract and interest people from distant parts of the State as well as local people.

By conspicuous recreational value is meant topography, trees, vegetation, streams, lakes, or ocean shore, which will attract and interest people of a wide surrounding area and which would not be available to the public if the property remained in private hands.

In the absence of striking scenic value, this may be compensated for by very unusual recreational value such as is represented by a very fine bathing beach or by an exceptional location with respect to population centers and main arteries of travel.

The State parks should be sufficient in number to meet the prospective demands of the people of each region over and above facilities which are or should be provided by local, city, county, town and village parks, and without requiring a State park budget which is unreasonable or excessive in the light of other financial demands. * * *

RULES GOVERNING THE ESTABLISHMENT OF ADDITIONAL STATE PARKS AND EXTENSIONS OF EXISTING PARKS

1. Minimum Area—Except in extraordinary cases the site should include not less than 400 acres of land well adapted for park use and development. Existing parks of smaller area should be extended to at least this minimum acreage.

2. Group of Smaller Units—In certain special cases, a group of smaller units may be desirable when the several sites are close enough together for a central management and it is not practical to acquire the land between units. This situation is illustrated by the several sites comprising the Niagara Reservation. Even here the ultimate objective should contemplate the connection of these units by a parkway or wide boulevard under park management. Small units along a State parkway for parking or picnicking are always desirable.

3.

4. The Large Park Compared to Smaller Parks—It is better to concentrate on one large fine park than to scatter efforts over a number of smaller parks in the same neighborhood.

5. Requirements for New Parks To Be Increasingly Strict—The establishment of new parks must not be carried to an extent which will interfere with the proper development of existing parks. For this reason the requirements for new park sites must become increasingly strict. A State park should be developed in a dignified and substantial manner and park funds should not be scattered over so many sites as to result in partial or improper development.

6. Historic and Scientific Features—The value of a State park site is enhanced if it contains historical and scientific features which are interesting and educational, but such factors are incidental and not controlling like scenic and recreational requirements.

Sites which are primarily historical and scientific should not be administered by the park authorities which lack the interest and knowledge to care for them. No new sites of this kind should be acquired, and those now in existence should be transferred to the education department as soon as the legislature can make provision for a Bureau of Historic and Scientific Places in that department.

7. Type of Land To Be Taken—In general, the policy is not to take unattractive, open farm lands for park purposes, but to utilize property which cannot be farmed economically. However, this should not be construed to prevent taking necessary open land to provide entrances, parking areas, recreational fields. etc., as adjuncts to the main park area.

8. Woods and Water—A site possessing a fair percentage of wooded area is to be preferred. A stream, lake, or ocean shore with water of sufficient purity for bathing is practically indispensable. Parks without bathing facilities or the possibility of such facilities, or without water views are not desirable.

9. Cost of Land—The cost of land should be relatively low considering the section of the State in which the park site is located. Other things being equal, a site involving a small number of present owners is to be preferred.

10. Cost of Development—The park site must eventually have entrance and other roads, drinking water, sanitary facilities, central building, clearing of grounds, etc. A site which necessitates unusually large expenditures to provide for basic developments should be avoided.

Figure 24. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window)RULES GOVERNING THE ESTABLISHMENT, EXTENSION, AND DEVELOPMENT OF PARKWAYS

Definition—A parkway is a narrow landscaped park with a pavement for motor vehicles running through it. Crossings at grade are eliminated and access is afforded only at fixed and specified entrances which are spaced a considerable distance apart and are not opposite each other.

1. Location—The State should establish parkways as distinguished from wide boulevards only through attractive country.

2. Width—In future the minimum width of a parkway right-of-way should be 300 feet. The average and maximum width should, of course, depend upon topography, cost, and other factors.

3. Crossings—No crossings at grade should be permitted, excepting over little-traveled roads, and even in the case of such roads, sufficient land should be acquired in the beginning for ultimate elimination. The question of whether a parkway should be elevated over a local or cross road, or whether the local or cross road should be elevated over the parkway should depend upon topography and cost. In flat country and especially in suburban centers every effort should be made to keep the parkway down. Other conditions being equal, the cost of elevating the parkway will be greater than the cost of elevating a narrower cross road, but the damage to adjacent property may be greater in the latter case. Sufficient land should be obtained at crossings so that no private property will be damaged by the elevation and to afford adequate space for planting and landscaping and for entrances.

4. Entrances—Public entrances should normally be constructed in connection with the elimination of crossings. There should never be less than two entrances in connection with a crossing, and these should be diagonally opposite each other. Entrance roads should approach the parkway pavement as nearly as possible at right angles, and of course, at grade. Private entrances should be granted only where substantial dedications of rights-of-way are made by private owners, or where land is sold by such owners to the State at considerably below market price, or where the absence of such private entrances affecting a considerable acreage of land would work a real hardship on the owner.

5. Pavements—The parkway should be paved with concrete or other hard-surface pavement. In order to avoid the glare and the whitish coloring of concrete, a surface treatment with a dark emulsion may be used, or a coating of bituminous macadam or some other similar material may be added.

6. Bridges—Bridges should be designed not only for strength but for appearance. Architects and landscape architects are fully as important in the design of parkway bridges as structural engineers.

7. Planting—Planting and landscaping of parkways is fully as important as pavement and bridges. No State parkway should be constructed without assurance of adequate funds for planting and landscaping as well as for maintenance after the initial planting is done.

8. Lighting—The lighting system on a parkway should be designed on the theory of silhouette illumination. The poles and fixtures should be appropriate and should blend with and fit into the landscaping and other parkway structures. The feed for the lighting system should be underground and no overhead wires of any description should be permitted.

9. Structures—There should be no structures along a State parkway excepting those purely incidental to its normal use as a driveway. If any filling stations are authorized they should be attractive in appearance and constructed from appropriate designs.

10. Zoning and Restrictions—The area adjacent to State parkways should be zoned wherever possible for the best type of private residence. This can be accomplished through cooperation with local governmental bodies. A State park commission entrusted with the care of parkways should follow every change in zoning ordinances affecting adjacent territory and all actions by the local board of appeals. Normally the State should attempt to have zoning restrictions established governing an area within at least 300 feet of the parkway. In some cases it may be found possible for the State to restrict adjacent private property by agreement with the owners, such restrictions to run with the land. This is a most desirable procedure where the owners will agree.

11. Other Restrictions—Normally all State parkways should be restricted to passenger cars other than busses. Only in the most exceptional cases should any other vehicles be permitted on the parkways.

12. Curves, Grades, Walks, Bridle Paths, Etc.—Normally there should be no curve on a parkway with a radius of less than 1,500 feet through flat topography; there should be no grade of more than 4 percent through flat topography or of more than 6 percent in rolling country. Wherever the right-of-way is sufficiently wide bridle paths and walks should be considered.

Adopted April 22, 1930, State Council of Parks.ROBERT MOSES, Chairman,

HENRY F. LUTZ, Secretary.Approved, May 1,1930,

ALEXANDER MACDONALD, Conservation Commissioner.

South Carolina, one of the States newly in the park field, frankly recognizes the problem imposed by the race segregation it is required to practice and by the vital necessity of providing proper recreational facilities for the Negroes who comprise more than 45 percent of the State's population. The Palmetto State has declared, through its State Commission of Forestry:

(1) That a State park must be an area of outstanding regional, scenic, historical, scientific, educational, or recreational value.

(2) That a park shall be located within 50 miles travel of every man, woman, and child in the State.

(3) That the area must be of sufficient size to meet the requirements of the activities which find their best expression in primitive settings. For development purposes topography, cover, water areas, and other natural resources have a definite bearing on this size but, in general, one thousand acres is minimum.

(4) That, because of the State's racial composition, two recreational area systems are necessary: one for white people and one for Negroes.

(5) That in the planning and development of the areas and facilities priority shall be given to those which serve mass needs. Therefore, the State shall first seek to meet the need for swimming, picnicking, and socialized mass activities.

Such statements of policy, which, for both these States, concern themselves with the principles of selection and, in very small degree, with the principles of development, could very well be supplemented, in every State, and by all park agencies, with similar enunciations of policy as to development and operation.

An official statement which appeared in the ninth annual report of the Department of Conservation of Indiana, illustrates the kind of statement of policy as to development and operation which, however much the policies themselves may vary among the several States, every State needs to formulate for itself, recognizing also that such statements should not be inflexible, but subject to change only when the conviction has been reached that changes are necessary and wise.

Says the Indiana statement:

. . . It seems that, within any given State, all park properties should be under the control of one governing body. Problems differ in many of the units, but their solution is made easier by the collected experience of a central office, and their policies more adequately carried on as a State Park policy. . . .

Into these parks crowd the vast masses of our industrial cities—a few aristocrats on foot, the remainder in cars. The first problem of administration is to answer their impulsive questions, Where do we go? What is there to see? What is there to do? These are important queries—the ones that brought them here. Some park authorities seem to think that the people will just naturally fall to, that they will find a proper camping-place, build a safe and sane fire, eat, be merry, clean up, and go home, and do all these most improbable things without ultimately ruining the very place they adore and immediately rendering it unsanitary and unsightly. A city is a livable place because sanitary precautions have been taken to keep the people from poisoning one another. What about the waters and the woods? The hot and stuffy city is a safer place, hygienically speaking, than the average run of summer resorts; and a State park will be no better unless all necessary safeguards are provided.

In our experience we have found that the comfort and well being of vast crowds can be best administered to by the use of one or more service areas. Within the main area are grouped the hotels, restaurants, lunch stands, shelter houses, cottages, garages, auto parking space, wash and toilet rooms, servant quarters, laundries, power and pump houses, garbage incinerators, septic tanks, etc.

Hotels and other food-vending places are under the supervision of the State. Our Indiana system of leasing the so-called "concessions" to carefully chosen managers is superior to letting them to the highest bidder or to the politically potent. We admittedly, however, are not automatically keeping up high standards—constant vigilance and admonition on the part of the State authorities are required. Let it be remembered that under our concession system all buildings and equipment belong to the State, with the exception of kitchen, pantry, and bedroom equipment which are furnished by the concessionaire. He also is responsible for all machinery in use.

Within the second area are provisions mainly for campers and picnickers, such as a safe supply of drinking-water, camp cooking places, sanitary toilets, etc. Safe bathing places along river banks and lake shores are indicated.

Altogether, the defined service area, serving as it does as a place of congregation and redistribtuion, handles large numbers with comparative ease. To it leads an unavoidable automobile parkway. From it radiate trails through woods and by shores. It serves, so to speak, as a filter. But, above all, it saves the landscape from ruin. It leaves this protected for the nature lover, student, artist, dreamer, and other impractical but socially highly important people. . . .

To a State developing a new State park system, I would submit the following list of "Do's" and "Dont's." It is a brief but safe program for administration:

1. Provide a well-planned service area.

2. Provide a safe and ample water supply.

3. Check its quality regularly in season by analysis.

4. Provide for sanitary sewage and garbage disposal.

5. Regulate quality and cost of food-stuffs and lodging.

6. Furnish fireplaces and free firewood to campers.

7. Stop the vandalism of picking or digging flowers and ferns, etc. (Best accomplished by appeals to the public.)

8. Keep a close watch for fires.

9. Avoid all artificial "improvements" in park proper.

10. Limit automobile drives to barest needs.

11. Construct easy and pleasant paths through woods and by waters.

12. Maintain service of nature-study guides.

13. Make small charge for parking and camping to assure proper maintenance.

14. Collect a small admission charge to park.

At the end of this list is a demand for a small admission charge. State parks ought to be made as nearly self-supporting as possible, or else the cost will have to be frankly put on the tax duplicate. In the first case, those who enjoy the park will contribute a small amount toward its maintenance; in the second, the taxpayer in the distant parts of the State who likely will never see the place, will be compelled, nevertheless, to contribute toward its purchase and maintenance.

So much for the administrative end of State parks. Its philosophy should be a minimization of useless effort on the part of the visitor and an enhancement of his appreciation of the natural charms and beauties of the place.

National Park Service Policy in Selection and Development. The policy of the National Park Service with respect to selection of areas for the status of national parks or monuments is now rather generally understood. The basic consideration is that any such area shall possess genuine national significance, even though it may in some cases involve a certain degree of duplication or repetition. Thus, Mount Rainier National Park contains as its central feature the highest of the western glacier-bearing volcanic peaks. However, its inclusion in the system is not considered to be a bar to ultimate inclusion of one or several others in the Northwest which contain such peaks, since they are likewise spectacular scenic features of national significance and possess striking individual characteristics. The new accepted classification—that of national seashore, not yet fully represented in the Federal system—involves no departure from this basic policy, since it is justified by the profound conviction that our remaining unmodified areas of seacoast are also fraught with true national significance.

Service policy has expanded during the present decade to the extent of recognizing that the recreational requirements of the country as a whole cannot be adequately met by the individual States when supplemented by a Federal system whose total content is limited to areas of national significance. It contends that there are areas of such extent and importance that they can and should render their service to a large region, embracing part or all of several States, but beyond the capacity of any single State either to acquire or administer. A complete and definite policy as to selection and development of such regional recreational areas, as parts of a Federal system is taking shape, but has not yet been finally formulated.

Developmental policies for national parks and monuments, whether primarily scenic, scientific, historic, or prehistoric in character, are reasonably well defined. Essential features of this policy are that:

1. No developments will be permitted in them which materially impair those features or qualities, the preservation and protection of which were the reason for their establishment in park or monument status.

2. Activities, recreational or otherwise, for which provision is made, shall be only those dictated by the character of the area itself, and desirable in order that the public may obtain the fullest possible enjoyment of those features or qualities on which its national status is based.

3. As large a part as possible of each national area shall be left completely unmodified, with access provided only by trail.

4. In every area the Service will endeavor to assist the public in understanding natural, historic, or prehistoric features, by such means as museums, trailside and roadside exhibits, guide service, publications, etc.

5. Suitable accommodations for housing and feeding visitors will be provided wherever possible, either by the National Park Service or by private operators. Commercial activities shall be limited to those essential to the care and comfort of park visitors.

6. Since all areas under National Park Service administration are established for the benefit of the whole public, no part of them shall be leased for the exclusive use of any person or group of persons.

OPERATION AND MAINTENANCE

Park visitors expect and deserve a pleasant, orderly environment. At first glance, it would seem to be a waste of words and time to say that the visitor has a right to receive courteous treatment at the hands of park employees; to find roads and trails decently maintained, camp and picnic grounds clean and neat, and buildings kept in repair. Yet, persons familiar with parks know that sloppy, inattentive, and discourteous employees are by no means uncommon, and that roads and trails, camp and picnic grounds, and structures of every kind, in various stages of neglect and disrepair, can be found in a number of parks and park systems.

No park or playground is established or can be justified as a public responsibility for its own sake, but only for the use that is to be made of it, now or in the future. Successful accomplishment of that purpose—use—is dependent on many things—proper selection in the first place, intelligent planning, and sound principles of operation, but most of all on competence of operation and maintenance. The results of poor administration at the top and even of improper selection and unintelligent planning can be largely overcome if the right kind of staff, with fairly adequate equipment for its task, is on duty on the area itself, while no amount of intelligence in selection and planning can compensate for inefficiency or incompetence in operating and maintaining it.

Effectiveness in accomplishment of the operation and maintenance task for any area and the facilities it contains is conditioned on factors, aside from personal qualities of employees, which are largely imposed by the central administration and which comprise its management policy. These factors, as they affect personnel, include such matters as wearing of uniforms, exercise of police power, as well as the basis on which the selection of personnel rests. As they affect the area, they include such matters as leases, method of operation of facilities (public or concession), regulation or limitation of use of certain types of facilities such as cabins, pavilions, picnic and campgrounds, playfields, etc., entrance and other fees and charges, control of prices, etc.

Supervision of Operation and Maintenance. Supervision of maintenance and operation is rapidly becoming a recognized special field in which the superintendent or custodian is really an administrator responsible for an area, and possessing wide latitude for independent action, subject to such policies as have been imposed on an area or a system by the administrative authorities. His domain is for public use and enjoyment, and there is no point of contact between governmental administration and the public where the principles of democratic government and management of public facilities are more personally and intimately encountered. The superintendent represents the public interest as defined by law and policy and defends and protects it against individual selfishness and special privilege. He and his staff interpret the area and its resources to the public and cooperate with organizations, recreational interest groups, and individuals in arranging for the use of the area's facilities.

Successful operation of most systems of parks requires a general superintendent whose responsibility it is to plan, initiate and supervise all operations and maintenance, and to indicate, on the basis of on-the-ground experience and observation, what further public requirements need to be met. To him falls the task of seeing that policies and regulations are observed, that areas and facilities are satisfactorily operated and maintained, and that proper equipment is available and kept in good condition. In smaller systems he frequently combines the functions of assistant director and superintendent of construction as well as manager of operations.

Relationship to Planning and Development. The importance of the relationship of planning and development to operation and maintenance has already been stressed. The superintendents, custodians, and various park assistants are in the best position to observe use of an area and its facilities, and to determine the degree of effectiveness of the service rendered and where the shortcomings lie. If plans do not work out as intended or conditions change or facilities fail in any way to fulfill their functions, these men know it first and must often contrive some way to correct the shortcoming. They are sharp critics of designers, usually quick to recognize good and bad planning from a practical point of view. They should be encouraged or even required to make their knowledge available and assist in the avoidance of errors that result from ignorance of the problems of operation or from failure to take them properly into account.

Such cooperation should be welcomed by every planning department and should extend beyond the mere correction of past errors. The competent and experienced park superintendent is one of the many specialists whose practical experience is needed as a guide in functional planning.

Park Manuals. Park manuals covering the many fields included in recreational administration are used by some park agencies to insure uniform methods of operation. Such manuals include rules, regulations, approved practices and other similar types of information. To be wholly effective, they must be kept up to date. While the subject matter dealt with varies, one of the newest and most complete, recently published for use in the Illinois State parks indicates the scope of such handbooks. It treats the following general subjects:

1. Brief description of State park properties.

2. Statement of State park legislation and policies.

3. Statement of duties and responsibilities of park superintendents. Emphasis on courtesy, discipline, esprit de corps, leadership, and uniform regulations.

4. Budget procedure, including use of forms for requisition of material, labor, and supplies.

5. Departmental organization chart and explanation of responsibilities.

6. Administrative operation and procedure, annual, monthly, and weekly activities, accident, fire, leave, and other reports.

7. Rules and regulations governing State parks and methods of enforcement.

8. Operation of equipment.

9. Operation of facilities, etc., campgrounds, picnic grounds, comfort stations, wood cutting, playgrounds, parking area.

10. Concessions, including responsibilities of the State and the concessionaires.

11. State park signs, use and purpose.

12. Wildlife, protection and care.

13. First-aid and lost-and-found procedure.

14. Fire control; prevention, detection, and suppression instructions.

15. Public relations and publicity.

16. Park planning, including use and purpose of surveys, master plans, working plans, and maps.

17. Maintenance of roads, buildings, equipment, water supply, and fixtures.

18. Maintenance and operation of sanitary facilities, including toilets and comfort stations, trash and garbage disposal, sewer lines, septic and Imhoff tanks, grease traps, sewage treatment plants.

19. Landscape work in parks, including complete outline of planting methods to remove construction scars, planting around buildings, erosion planting, plant selection, planting practice, care of planted material, tree surgery, and lists of plant material.

Although other subjects may be included, this general outline of the contents of a typical good park manual gives an idea of the possibilities. It also illustrates the diversity of operations that require qualified supervision and capable personnel, and indicates that, in most parks, the superintendent or custodian is compelled to function in many capacities.

Control. In order that all visitors may have an equal opportunity to enjoy themselves and that the resources of a park may be protected, regulation of conduct is required. Mere numbers of people alone make this necessary. Any large crowd, no matter how well behaved or considerate, is to some extent destructive of natural values. When even a small minority are vandals, while others are unfamiliar with conservation ethics, careless or selfish, the destruction multiplies.

There are four general approaches to the problem of control, namely: (1) planning, (2) regulations, (3) education, and (4) a well conceived and executed program of use. Each has its possibilities and limitations. All four approaches have been used with varying success.

A well laid out system of roads and parking areas may be taken as an example of the relationship between planning and control. A single entrance where practicable, the fewest possible intersections, all well marked, roads adequate in width to handle the traffic load, a generous use of effective barriers to discourage the inconsiderate driver from destructive practices, and parking areas so designed that the man of average intelligence. will know where and how to park, are some of the features of a circulation system which facilitates control. A simplification of trail lay-outs and a proper grouping and design of facilities are other important aids to efficient management. If, wherever possible, the proper thing to do is also the simplest and easiest, the necessity for application of other means of control is largely eliminated.

While some regulations are necessary no matter how successful other aids to control may be, they should be applied so that the public is guided rather than driven. Too much regulation, particularly if it is petty and nagging, tends to provoke rather than deter misconduct. An educational approach when a receptive attitude is shown by offenders is far more conducive to results than recourse to authority. To be really effective, however, education should be a continuous process, applied rather to guide than to correct, and positive, rather than negative. The English language contains few words more irritating than "Don't."

By wise counsel and stimulating guidance in natural science, history, woodcraft, and the arts education instills understanding, and a greater appreciation in the public mind. Through printed material, the lecture, the radio, photography, and by personal instruction, a great amount of effective work is accomplished. Many States and other agencies are using this educational approach more effectively every year.

The trite adage about idle hands and minds being the devil's instruments has a particular significance to the problem of effectively handling park visitors. Give people interesting things to do, if they wish to do anything but loaf, and they will be less likely to become obstreperous and destructive in their habits. A well-balanced program directed toward utilizing the resources of a park, if intelligently handled, will do much to eliminate the need for coercion in regulating the conduct of visitors.

Exclusive Privileges and Services. Practically unanimous agreement in principle exists among informed administrators on the undesirability of providing exclusive services for or permitting exclusive privileges to individuals on public park and recreational lands. Examples of exclusive privileges are the individual lease, occupancy, or privileged use for any extended period of time of land, buildings or facilities that belong to the public recreational area where such lease or occupancy deprives some other person of an equal opportunity. Failure to observe this as one of the first principles of democratic management opens the door to serious misuse of public property and to just accusations of unfair discrimination.

Probably the most flagrant violation of this principle occurs when an individual is granted a lease hold or rental on public land for private residential use or for some other private activity that largely restricts the use of the area occupied to one individual, family, or group. This practice has become very unpopular among the administrators of park lands because of the difficult situations that invariably develop when private and public interest conflict. Since such leases normally involve some investment of private funds in buildings and facilities, the lessee is quick to assume—usually effectively—that he possesses a vested right which is not to be disturbed.

A problem similar to the exclusive privilege may also arise from many other situations. These include the private rental or exclusive occupancy, by individuals or groups, of cabins or other buildings, campgrounds, picnic facilities or other accommodations provided at public expense. With respect to use of such facilities, most park authorities have adopted a "first come, first served" policy and this seems to be the fairest system. There are, however, times and places where this policy must be modified to escape confusion and conflict during "peak-load" periods. At such times it may be necessary to make reservations of buildings, camp and picnic grounds, playfields, and others for which the demand far exceeds the supply. It is possible, even under such conditions, to insist on fair play and guard against the abuse of privileges granted. In the case of cabins, campgrounds or heavily used picnic areas and playfields, time of occupancy must sometimes be limited in order to provide for the use of facilities by the greatest number of individuals. Long-period occupancy of such facilities as cabins, particularly if the demand exceeds the supply, appears to be definitely classifiable as special privilege, undemocratic and undesirable.

Operation of Facilities. Park folk have found in the provision and operation of facilities a most fertile field for controversy. There are sharp differences of opinion as to the range of facilities to be offered, equally sharp differences as to whether the private operator or concessionaire should have any hand in their operation and if so, which ones should be let out as concessions and which retained for direct operation. In addition there is the important difference in method of letting concessions, between competitive bidding, and the definite-return arrangement under which selection is based, presumably, on ability to operate to the satisfaction of the public and the park authority. There are likewise differences of opinion as to the basis of rate making for services or commodities. All these are, of course, matters of administrative determination which are nevertheless phases of the operation problem, since they largely determine the character of the problem.

Comparatively few State park agencies operate dining facilities or park hotels. More of them handle directly the rental of cabin facilities, since provision of meals is not normally a part of such an operation. Campgrounds and picnic grounds, even when their operation involves collection of a fee, are normally handled directly by the park staff. Beach and bathhouse operation, though occasionally placed with a concessionaire, is also usually handled directly. With the possible exception of catering and hotel operation, it is believed to be the best policy, from the public standpoint, for all other facilities to be the direct responsibility of the park staff, since it is believed that, under such an arrangement, the public interest, rather than the urge for profit, is more likely to dominate.

Figure 25.—Shelter and concession building, French Creek Recreational Demonstration Area, Pennsylvania. |

It must be admitted that concession operation of hotels and restaurants has been highly satisfactory in many cases. Since the personality of the operator, his ability, and his attitude toward his responsibilities and the public are such vital factors in the success—from the public standpoint—of such undertakings, the procedure of letting such concessions simply to the person or corporation that is willing to pay the most for the privilege appears to have almost nothing to recommend it. Unfortunately, some legislative bodies prescribe it. On the other hand, an arrangement whereby a definite fair return from an operation is determined, the conditions for its conduct prescribed, and a choice of operator is made on the basis of character and experience, from among those willing to undertake the task, appears to be the best solution that has yet been formulated. It is highly important, however, that the fixed facilities—buildings, and their permanent contents, water supply and sewage disposal systems, etc.—be publicly owned rather than owned by the operator. Operator ownership can not help involving additional difficulties in any case in which a change of management proves desirable.

Since service to the public is the sole purpose for which facilities are provided and operated, it is the responsibility of the person in charge of any park to see that satisfactory and courteous service is given, that requirements as to maximum prices, if established, are met, that facilities are maintained in neat and sanitary condition, and that park regulations are being fully observed.

Price policies are, of course, matters of general park administrative policy, not the responsibility of the individual superintendent. In general, it appears to be wise policy to keep them at a level no higher than that which might reasonably be charged for similar services, accommodations or commodities by private enterprisers elsewhere. The policy of attempting to make them definitely lower is a dubious one. When practiced in the case of vacation cabins, for example, for the purpose of making them available to persons of small means, there is no assurance that they will not be utilized by those amply able to pay fair commercial prices. Provision of accommodations at less than such prices gives the transaction a tinge of charity. The answer to the problem of low rental vacation accommodations appears to lie only in provision of simple and inexpensive facilities and in encouragement of tent camping—a type of vacation facility which many park authorities have been inclined to overlook, though it is within the means of and enjoyed by millions of persons, but can be provided cheaply and yet is also a good source of income.

Figure 26.—Contact station, Turkey Run State Park, Indiana. |

Health and Safety. The problem of protecting the health and safety of park visitors is one of the most important and difficult tasks faced by an administration. One serious accident, even though an administration is entirely innocent of blame, can do more to destroy public confidence than a number of blunders in other phases of operation. It may also result in an expensive law suit. A rumor that conditions in a park are not healthful discourages attendance. The adage about cleanliness being next to godliness might well have been coined by a good park operator.

Good planning and development of roads, trails, beaches, structures, and other facilities can do much to eliminate or mitigate hazards and unsanitary conditions, but in the final analysis the responsibility for protecting visitors rests with the operation and maintenance staff. Policies governing use play an important part. Typical of the points that need to be dealt with under such policies are those that have to do with the use of boats, the conduct of swimmers and the latitude permitted in allowing hazardous activities such as mountain climbing, canoeing in rapid, rocky streams, and swimming beyond the marked and guarded area. Frequent examinations of water used for drinking and swimming is another important protective measure.

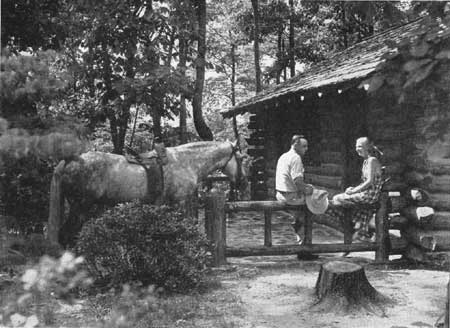

Figure 27.—One of the 10 cabins overlooking the Potomac River in

Westmoreland State Park, Va.

A competent, well-trained water-front staff, operating under a definite water-front plan, is an indispensable requirement wherever swimming is permitted. Protective regulations, posted where they will be seen and read by visitors, and strict enforcement of these regulations constitute a well-known practice which is too often either ignored or poorly observed.

The above points are only a few of the many that should be considered in preparing a plan of operation and maintenance. They have been included to indicate the importance and scope of the problem. Good park manuals, literature from the American Red Cross, regulations issued by the National Committee of Sanitary Engineers and other similar sources of information should be consulted in working out a health and safety system, but must be supplemented by constant watchfulness to discover hazards and by constant effort to eliminate or reduce them.

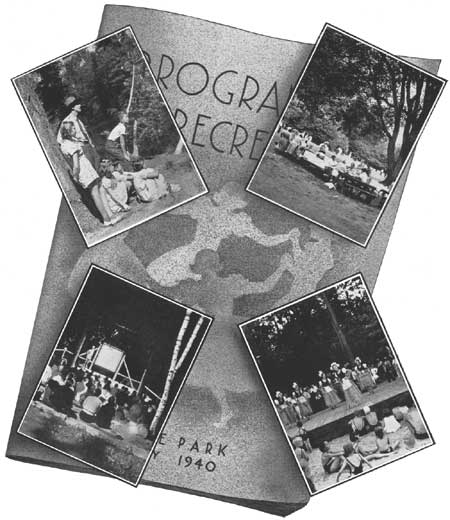

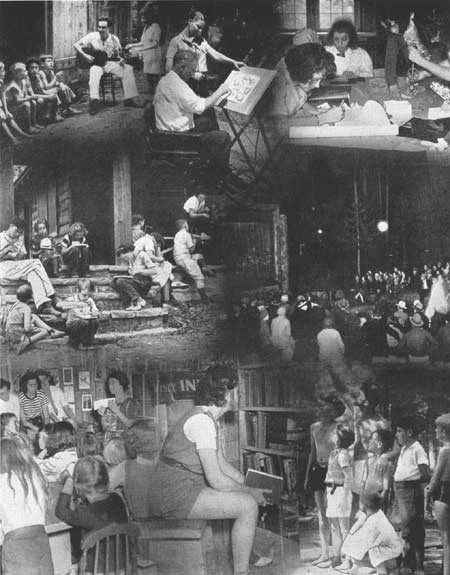

Figure 28.—Competent leadership is essential to a well-rounded

recreational program.

ORGANIZATION AND ENCOURAGEMENT OF USE

This section has been written with the realization that there are many enthusiastic park supporters who react with varying degrees of alarm when the words "organization" and "leadership" are mentioned. To many these words conjure up visions of regimentation. They fear that the ideas represented will seriously interfere with the fine informal types of recreation that natural parks have been established to furnish. Such is not the intent. The difficulty arises from the different connotations these words have for different people. That some organization and leadership exists in all forms of outdoor recreation is a fact which cannot be overlooked in any discussion which deals broadly with the subject of recreational planning. For this reason, a careful effort has been made to define and explain what is meant when these words are used.

Types of Participation. Participation in recreation may be individual and spontaneous or it may involve planning and group cooperation. Many activities such as swimming, picnicking, hiking, and boating lend themselves to both types of participation; while others such as baseball, tennis, polo, bridge, and chess are limited to groups of two or more playing together under established rules and regulations. Park activities generally fall within the first classification, and participation is very likely to be spontaneous in origin. It should be noted, however, that even where participation arises spontaneously, some organized and directed effort is generally necessary in order to provide the opportunity. This involves the elements of organization and leadership.

"Organization is the form of every human association for the attainment of a common purpose!" In the field of recreation, organization constitutes the method through which people work together, (1) in advancing recreation as a social responsibility, (2) in providing recreational opportunities, and (3) in participating in activities. Park associations, wildlife councils, hunting and fishing associations, and citizens' recreation committees typify the kinds of organizations which perform the first of these functions. Park departments, recreation commissions, and Boy Scout councils have the responsibility of providing recreational opportunities. Hiking, nature study and athletic clubs, baseball teams, little theatre groups, and chorus clubs are representative of participatory organizations.