|

National Park Service

A Study of the Park and Recreation Problem of the United States |

|

Chapter V:

Financing

|

|

VERNAL FALLS—A SILVERY VEIL OVER SHADOWED CLIFFS Yosemite National Park, California |

HISTORY OF FINANCING RECREATION

|

Local Governments. In 1565, when the city of St. Augustine in Florida was laid out, provision was made for open spaces for the enjoyment of the public. In 1573, shortly before the town was moved to its present location, the King of Spain set forth certain regulations for the laying out of towns in foreign colonies, containing the following provisions which applied to St. Augustine: |

|

The (main) plaza shall be of oblong form inasmuch as this is best for fiestas in which horses are used and for any other fiestas that shall be held. . . . A commons shall be assigned to the town of such size that although the town continues to grow, there may always be sufficient space for the people to go for recreation. . . .

As the country grew, various cities continued this policy of providing open spaces within their corporate limits. As the years went by the wisdom of this early provision became more evident, and with the demand of the public for a more diversified use of such spaces our municipal park and playground systems have developed and increased appropriations for such purposes have been made. In 1930 municipalities and counties provided approximately $140,000,000 for their park and recreation systems. In common with expenditures for other services of local governments this figure was substantially decreased during the recent economic emergency until in 1935 it represented about half that amount. Since 1935, however, expenditure for this purpose has been steadily increasing.

State Governments. When the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1641 decreed by ordinance that great ponds—bodies of water over 10 acres in extent—be forever open to the public for fishing and fowling, recognition was given to the fact that provision for recreation beyond the corporate limits of cities should be made by the larger units of government. Further attention to such provision was given by the State of California in 1865 and by New York, Minnesota, and Connecticut in the 1880's and at that time these States began providing funds for State park purposes.

Previous to 1934 only nine States had provided annual appropriations in any considerable amount for State park and related work. These included Connecticut, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and Rhode Island (Table A). South Dakota had provided adequately for Custer State Park but had not developed a State-wide system. Since 1933 California, Massachusetts, Washington, Missouri, New Hampshire, Minnesota, Louisiana, Kentucky, Oregon, Tennessee, and New Jersey have improved their financing to the extent that they may be listed as fairly well financed systems.

TABLE A. Expenditures for State parks, fiscal year, 1933—34

| State | Agency1 | 1933-34 |

| Alabama | (2) | |

| Arizona | (2) | |

| Arkansas | (2) | |

| California | Division of Parks, Department of Natural Resources | $l50,000.00 |

| Colorado | (2) | |

| Connecticut | Division of Parks, State Park and Forest Commission | 269,017.00 |

| Delaware | (2) | |

| Florida | Board of Forestry | 12,500.00 |

| Georgia | (2) | |

| Idaho | Department of Public Works | 3 2,293.32 |

| Illinois | Division of Parks and Memorials, Department of Public Works and Buildings | 291,466.00 |

| Indiana | Division of Lands and Waters, Department of Conservation | 67,800.00 |

| Iowa | Division of Lands and Waters, Department of Conservation | 110,000.00 |

| Kansas | Forestry, Fish, and Game Commission | 44,767.92 |

| Kentucky | Division of Parks, Department of Conservation | 22,500.00 |

| Louisiana | (2) | |

| Maine | (2) | |

| Maryland | (2) | |

| Massachusetts | Division of Parks and Recreation, Department of Conservation | 40,068.78 |

| Michigan | State Parks Division, Conservation Commission | 84,124.28 |

| Minnesota | Division of State Parks, Department of Conservation | 40,600.00 |

| Mississippi | (2) | |

| Missouri | State Game and Fish Department | 4 85,236.07 |

| Montana | (2) | |

| Nebraska | State Game, Forestation, and Parks Commission | 18,425.00 |

| Nevada | (2) | |

| New Hampshire | Forestry and Recreation Commission | 10,884.52 |

| New Jersey | Department of Conservation and Development | (5) |

| New Mexico | (2) | |

| New York | Division of Parks, Conservation Department | 4,197,529.23 |

| North Carolina | (2) | |

| North Dakota | State Historical Society | 300.00 |

| Ohio | Division of Conservation, Department of Agriculture | 72,851.89 |

| Oklahoma | (2) | |

| Oregon | State Highway Department, Champoeg Memorial Park | 25,000.00 |

| Pennsylvania | Bureau of Parks, Department of Forests and Waters | 114,750.00 |

| Rhode Island | Division of Forests, Parks and Parkways, Department of Agriculture and Conservation | 117,093.19 |

| South Carolina | (2) | |

| South Dakota | (2) | |

| Tennessee | (2) | |

| Texas | (2) | |

| Utah | State Board of Park Commissioners | 500.00 |

| Vermont | Department of Conservation and Development | 2,000.00 |

| Virginia | Division of State Parks, Conservation Commission | 6 50,000.00 |

| Washington | State Parks Committee | 15,000,00 |

| West Virginia | Department of Conservation | 70,000.00 |

| Wisconsin | State Conservation Commission | 25,752.09 |

| Wyoming | State Board of Charities and Reform | 7 8,780.00 |

2 No State park system.

3 Heyburn State park only.

4 Reported as State park expenditures but used mostly for fish and game program.

5 Not reported.

6 Special for land acquisition.

7 Hot springs and Saratoga Hot Springs State parks only.

Twenty-one States have made their first specific appropriations to State park agencies responsible for the development of State-wide systems, since 1932. Of these Georgia, Louisiana, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia have made beginnings which augur well for the future.

A great impetus to the expansion of State park work came with the establishment of the Civilian Conservation Corps by Executive Order in April 1933. Through this agency nearly $300,000,000 has been expended on work performed under the technical supervision of the National Park Service on State, county, and metropolitan parks, which has caused the States to establish various types of administrative organizations, acquire new areas, assist in development and provide budgets for the operation and use of the parks.

Federal Government.1 The Federal Government recognized the preservation of scenery and its use for recreation of one kind or another when it turned the Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove over to California to be a State park. It recognized these objectives again in 1872 when it created Yellowstone National Park; subsequently when it created additional national parks; and again in 1916 when Congress authorized the creation of the National Park Service. Financial support of the Service's activities has steadily increased; in 1929 it amounted to $4,524,647, while in 1938 it was $14,395,930.

1 Figures quoted in this section, unless otherwise indicated, refer to the period from 1933 through the fiscal year 1938.

The United States Forest Service has been evincing an increasing interest in recreation in connection with the national forests as evidenced by the growth in expenditures for the administration of recreation from $65,028 in 1929 to $588,892 in 1938, the most rapid increase occurring in the past four years.

The Tennessee Valley Authority, in carrying out its major functions of improving navigation and providing for flood control and the generation of electric power, has created valuable recreational resources in the form of extensive lakes and, in addition, has developed parks and freeways. Through 1938 the Authority expended $184,490 on development of these areas (in addition to Civilian Conservation Corps expenditures) and $98,610 on maintenance and operation.

Likewise, in the work of the Bureau of Reclamation of the Department of the Interior, construction projects such as Boulder Dam have created important recreational resources the cost of which is allocated to other purposes. The recreational features in connection with the Boulder Dam area are now under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service. Similarly, the War Department, through its navigation and flood control projects, has added materially to the recreational resources of the country.

The Work Projects Administration has expended large sums for the development of recreational facilities as well as for the organization and conduct of recreational programs. To January 1, 1939, $681,319,000 was spent by this agency on parks and other recreational facilities (exclusive of buildings) and on recreational activities. The Federal Emergency Relief Administration spent $124,763,840 for recreational facilities and approximately $8,894,000 on recreational leadership. Comparable classifications of project expenditures under the Civil Works Program are not available. The largest proportion of WPA, CWA, and FERA funds was expended on local areas and a similar proportion of CCC funds was spent on State areas.

The Public Works Administration expended $2,668,166 on Federal recreational projects, loaned $7,997,700 to States and local communities, and made grants of $7,302,799 to such government units for recreational development.

PRESENT SITUATION

Thus, well over a billion dollars has been spent through the emergency agencies of the Federal Government during the past few years, most of which has been used for development of areas and construction of facilities. The expenditure of such a vast sum for facility development has undoubtedly accelerated the provision of physical features for the recreational program by at least 25 years, and in all probability more. The allocation of such a percentage of public works and work relief funds for this purpose undoubtedly reflects a demand on the part of local communities, since the great preponderance of projects originated with local and State governments. It also reflects the recognition of the Federal Government that such developments could be of immense public benefit, since it has been consistently required that work relief projects should be "socially useful."

The possession of such physical facilities, however, entails public responsibility for their proper maintenance and operation and social responsibility and opportunity to make them render the greatest possible service. The States and local communities were expected to assure such financial support when the projects were approved or Civilian Conservation Corps camps assigned. Through long experience in many fields, public agencies are aware of the necessity for trained technical and professional personnel in enterprises involving construction, but in a great many instances they are not conscious of the necessity for and the qualifications of professional personnel in the field of operation and use of recreational facilities. Only by the employment of such personnel can satisfactory results be obtained and widespread human benefits be realized. If such benefits are not realized it will become increasingly difficult to justify and to obtain adequate public funds for the recreational program.

BASIC SUPPORT—TAX FUNDS

Undoubtedly there are many supplemental sources which will contribute toward the financing of a public recreational program. But in order that the agency may have a dependable, adequate budget with the probability for increment as the responsibilities and needs of the agency increase, governing authorities must face the situation squarely and make adequate provision out of regular tax revenues for at least the primary needs of properly qualified personnel, equipment, materials, transportation, office supplies and other essential items. There are never-ending opportunities to use additional funds to advantage, and no opportunity should be overlooked to take full advantage of any additional sources of revenue provided they do not restrict the service of the agency or negate its social purposes.

FINANCING STATE PARK SYSTEMS

The following discussion will apply particularly to the problem of financing State park systems. All that has been said in the previous discussion will apply in this connection.

Table B shows the amount of funds available to State park agencies in 43 States for the past few years and the proportion derived from various sources. New York State has not reported this information. Its expenditures for parks and park ways during the past few years have amounted to from about $5,000,000 to $7,000,000 annually, a sum greater than the annual combined expenditures of all other States. It will be noted that funds available from regular and special appropriations (the latter included in the column headed "Other") constitute 72.7 percent of the total, from bonds 3.8 percent, from concessions 3 percent, from direct operation of facilities 6.9 percent, and from other sources as indicated by the table, 13.6 percent.

TABLE B.—Sources of funds for State park agencies, fiscal years 1935-36, 1936-37, 1938-39

| STATES AND AGENCIES1 | Grand total | TOTAL AVAILABLE FUNDS | APPROPRIATIONS | BONDS | CONCESSIONS | INCOME FROM OPERATIONS | OTHER | ||||||||||||

| 1935-36 | 1936-37 | 1938-39 | 1935-36 | 1936-37 | 1938-39 | 1935-36 | 1936-37 | 1938-39 | 1935-36 | 1936-37 | 1938-39 | 1935-36 | 1936-37 | 1938-39 | 1935-36 | 1936-37 | 1938-39 | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| Total | $11,701,242.05 | $3,391,673.16 | $3,878,218.79 | $4,431,350.10 | $2,005,810.67 | $2,203,329.54 | $2,925,208.83 | $173,522.51 | $237,653.26 | $30,609.63 | $124,618.45 | $150,289.43 | $74,185.66 | $186,254.16 | $201,524.34 | $424,618.93 | $901,467.37 | $1,085,422.22 | $976,727.05 |

| ALABAMA:3 Department of Conservation, Division of State Park, Historical Sites and Monuments Museum of Natural History (Mound Park) |

80,881.48 12,821.00 | 17,166.55 6,280.00 |

26,623.16 6,561.00 | 36,891.77 (3) |

9,630.66 5,680.00 | 19,792.50 5,925.00 |

36,891.77 | 949.54 580.00 | 1,705.81 636.00 |

6,586.97 | 5,124.85 | ||||||||

| ARIZONA: No State park system |

|||||||||||||||||||

| ARKANSAS: State Park Commission |

29,036.03 | 7,970.04 | 5,065.99 | 16,000.00 | 2,938.65 | 3,400.00 | 11,000.00 | 1,592,74 | 1,665,99 | 5,000.00 | 43,438.65 | ||||||||

| CALIFORNIA: Department of Natural Resources, Division of Parks |

1,133,320.80 | 289,103.20 | 306,686.40 | 537,531.20 | 179,127.30 | 179,127.50 | 364,585.00 | 50,959.92 | 36,458.00 | 30,609.63 | 24,145.84 | 24,145.84 | 26,203.06 | 26,203.06 | 8,667.08 | 40,662.00 | 5142,336.57 | ||

| COLORADO: State Park Board 6 |

|||||||||||||||||||

| CONNECTICUT:3 State Park and Forest Commission, Division of State Parks |

816,349.47 | 290,109.36 | 526,240.11 | (3) | 155,109.36 | 176,240.11 | 7135,000.00 | 7350,000.00 | |||||||||||

| DELAWARE: State Park Commission 6 |

|||||||||||||||||||

| FLORIDA: Board of Forestry, Forest and Park Service |

114,091.84 | 34,428.00 | 35,025.00 | 4,638.84 | 30,500.00 | 29,825.00 | 36,448.13 | 1,198.00 | 2,710.00 | 5,425.69 | 2,730.00 | 2,490.00 | 82,795.02 | ||||||

| GEORGIA: Department of Natural Resources, Division of State Parks, Historical Sites, and Monuments |

102,402.44 | 5,274.15 | 35,355.44 | 61,772.85 | 4,875.00 | 31,950.40 | 47,099.99 | 399.15 | 3,375.74 | 11,601.42 | 29.30 | 93,071.44 | |||||||

| IDAHO:3 Department of Public Works |

19,683.58 | 7,624.29 | 7,624.29 | 4,435.00 | 3,575.00 | 3,575.00 | 4,435.00 | 2,867.44 | 2,867.44 | 1,181.85 | 1,181.85 | ||||||||

| ILLINOIS: Department of Public Works and Buildings, Division of Parks and Memorials |

819,021.00 | 176,033.00 | 176,033.00 | 466,955.00 | 176,033.00 | 176,033.00 | 466,955.00 | ||||||||||||

| INDIANA: Department of Conservation, Division of Lands and Waters |

1,287,047.20 | 328,318.34 | 291,598.34 | 667,130.52 | 57,450.00 | 57,450.00 | 55,230.00 | 44,765.85 | 46,971,99 | 46,857.84 | 108,523.89 | 127,076.62 | 155,299.71 | 117,578.60 | 117,578.60 | 10409,742.97 | |||

| IOWA: State Conservation Commission, Division of Lands and Waters |

935,015.11 | 373,724.16 | 370,675.91 | 190,615.04 | 110,000.00 | 110,000.00 | 170,987.00 | 612.40 | 1,542.93 | 4,276.55 | 15,351.49 | 11263,111.76 | 11263,111.76 | ||||||

| KANSAS: Forestry, Fish and Game Commission |

141,565.40 | 58,395.04 | 40,500.00 | 42,670.36 | 600.00 | 700.00 | 1257,795.04 | 1257,795.04 | 1242,670.36 | ||||||||||

| KENTUCKY: Department of Conservation, Division of Parks |

177,178.76 | 37,014.32 | 42,790.16 | 97,374.28 | 22,500.00 | 22,000.00 | 34,264.43 | 2,742.10 | 5,577.33 | 2,577.84 | 11,772.22 | 15,012.83 | 52,574.59 | 7,957.42 | |||||

| LOUISIANA: State Parks Commission |

187,810.49 | (3) | 83,528.00 | 102,282.49 | 85,528.00 | 101,500,00 | 679.24 | 103.25 | |||||||||||

| MAINE: State Parks Commission |

9,500.00 | 1,000.00 | 1,000.00 | 7,500.00 | 1,000.00 | 1,000.00 | 7,500.00 | ||||||||||||

| MARYLAND: Department of Forestry, Division of State Parks |

96,875.45 | 29,079.91 | 54,668.28 | 13,127.26 | 12,811.00 | 11,628.00 | 12,320.15 | 189.40 | 617.71 | 16,268.92 | 43,040.28 | ||||||||

| MASSACHUSETTS:3 Department of Conservation, Division of Parks and Recreation |

572,357.43 | 301,015.50 | 129,916.93 | 141,425.00 | 301,015.50 | 129,916.93 | 141,425.00 | ||||||||||||

| MICHIGAN: Department of Conservation, Division of State Parks |

502,771.77 | 142,390.04 | 156,730.98 | 203,650.75 | 127,352.03 | 119,500.00 | 203,650.75 | 15,038.01 | 37,230.98 | ||||||||||

| MINNESOTA: Department of Conservation, Division of State Parks |

554,549.90 | 217,370.15 | 119,581.01 | 217,598.74 | 69,420.56 | 67,372.72 | 50,624.85 | 12,403.63 | 15,276.63 | 8,055.25 | 19,387.69 | 13135,545.96 | 1336,931.46 | 13139,530.95 | |||||

| MISSISSIPPI: State Board of Park Supervisors |

28,316.33 | 1,123.94 | 2,595.39 | 24,597.00 | 18,000.00 | 4,018.00 | 1,123.94 | 2,595.39 | 2,579.00 | ||||||||||

| MISSOURI:2 State Park Board |

267,364.78 | 55,702.78 | 80,275.00 | 131,387.00 | 80,275.00 | 131,387,00 | 9,838.06 | 1245,864.72 | |||||||||||

| MONTANA: State Park Commission 6 |

|||||||||||||||||||

| NEBRASKA: State Game, Forestation and Parks Commission |

32,500.00 | 15,800.00 | 16,700.00 | (3) | 15,800.00 | 16,700.00 | |||||||||||||

| NEVADA: State Park Commission |

6,000.00 | 500.00 | 500.00 | 5,000.00 | 250.00 | 250.00 | 5,000.00 | 250.00 | 250.00 | ||||||||||

| NEW HAMPSHIRE: State Forestry and Recreation Commission |

181,134.08 | 40,503.86 | 140,630.22 | (3) | 17,192.50 | 17,192.50 | 10,273.31 | 111,376.12 | 5,265.69 | 5,945.77 | 1,129.52 | 1,381.77 | 6,642.84 | 4,734.06 | |||||

| NEW JERSEY: Department of Conservation and Development, Division of Forests and Parks High Point Commission |

178,922.53 98,762.06 | 38,803.11 (3) |

52,615.42 (3) | 87,504.00 98,762.06 |

38,803.11 | 52,615.42 |

87,504.00 72,350.00 | 298.0 | 26,114.06 | ||||||||||

| NEW MEXICO: State Park Board |

12,835.35 | 5,210.10 | 7,625.25 | (3) | 5,000.00 | 7,200.00 | 210.10 | 425.25 | |||||||||||

| NEW YORK: Conservation Department 3 |

|||||||||||||||||||

| NORTH CAROLINA: Division of Forestry, Department of Conservation and Development |

30,004.75 | 5,567.89 | 6,528.86 | 17,908.00 | 5,300.46 | 5,444.88 | 9,166.63 | 267.43 | 1,083.98 | 2,122.37 | 6,619.00 | ||||||||

| NORTH DAKOTA: State Parks Committee of State Historical Society |

24,870.49 | 12,446.31 | 12,424.18 | (3) | 12,446.31 | 12,424.18 | |||||||||||||

| OHIO: Department of Agriculture, Division of Conservation and Natural Resources Archaeological and Historic Society |

242,223.46 213,192.03 | 135,625.96 62,435.00 |

106,597.50 67,635.00 | (3) 83,122.03 |

130,270,00 54,572.11 | 106,597.50 54,635.00 |

80,440.00 | 3,300.00 | 5,500.00 | 2,682.08 | 5,355.96 4,562.89 | 7,500.00 | |||||||

| OKLAHOMA: State Planning and Resources Board, Division of State Parks |

80,000.00 | 12,500.00 | 12,500.00 | 55,000.00 | 12,500.00 | 12,500.00 | 45,000.00 | 10,000.00 | |||||||||||

| OREGON: State Highway Commission Champoeg Memorial Park |

258,870.25 6,336.50 | 36,974.19 4,425.00 |

91,132.44 1,911.50 | 130,763.62 (3) |

4,425.00 | 1,911.50 | 1436,974.19 | 1491,132.44 | 14130,763.62 | ||||||||||

| PENNSYLVANIA: Department of Forests and Waters, Bureau of Parks |

498,125.96 | 90,280.46 | 161,933.88 | 245,911.62 | 90,280.46 | 161,195.38 | 204,422.00 | 41,489.62 | 738.50 | ||||||||||

| RHODE ISLAND: Department of Agriculture and Conservation, Division of Forests, Parks, and Parkways |

605,405.53 | 218,797.35 | 255,694.14 | 130,914.04 | 160,508.07 | 115,965.00 | 109,414.13 | 112,289.28 | 89,729.14 | 4,699.70 | 16,800.21 | 1550,000.00 | |||||||

| SOUTH CAROLINA: State Forestry Commission |

67,418.08 | 5,014.76 | 21,705.48 | 40,697.84 | 5,014.76 | 20,359.67 | 22,500.00 | 1,345.81 | 18,140.39 | 57.45 | |||||||||

| SOUTH DAKOTA: State Park Board |

203,409.59 | 122,313.65 | 114,095.94 | (3) | 105,300.00 | 127,800.00 | 6,725.50 | 7,543.50 | 10,288.15 | 8,752.44 | |||||||||

| TENNESSEE: Department of Conservation, Division of Parks |

85,816.00 | (3) | (3) | 85,816.00 | 27,495.00 | 13,821.00 | 44,500.00 | ||||||||||||

| TEXAS: State Parks Board Board of Control |

141,087.47 19,498.00 | 36,872.52 10,014.00 |

48,986,48 9,454.00 | 57,228.47 |

30,590.00 10,014.00 | 36,090.00 9,484.00 |

39,250.00 | 6,282.52 | 10,986.48 | 7,179.22 | 10,799.05 | ||||||||

| UTAH: State Board of Park Commissioners |

2,250.00 | 500.00 | 500.00 | 1,250.00 | 500.00 | 500.00 | 1,250.00 | ||||||||||||

| VERMONT: Department of Conservation and Development |

25,250.90 | (3) | (3) | 25,250.03 | 25,250.00 | ||||||||||||||

| VIRGINIA: Conservation Commission, Division of Parks |

110,750.00 | (3) | 46,190.00 | 64,560.00 | 46,190 00 | 64,560.00 | |||||||||||||

| WASHINGTON: State Parks Committee |

186,118.00 | 57,950.00 | 57,950.00 | 68,218.00 | 20,200.00 | 20,200.00 | 68,218.00 | 37,750.00 | 37,750.00 | ||||||||||

| WEST VIRGINIA: Department of Conservation, Division of Parks |

200,953.55 | 19,855.77 | 48,351.46 | 132,746.32 | 19,855.77 | 48,351.46 | 120,000.00 | 51.86 | 12,694.46 | ||||||||||

| WISCONSIN: State Conservation Commission, Division of Forests and Parks |

211,567.75 | 68,254.35 | 50,198.40 | 93,115.00 | 55,844.57 | 25,000.00 | 49,115.00 | 260.00 | 15,200.00 | 9,809.78 | 9,998.40 | 1644,000.00 | |||||||

| WYOMING: State Board of Charities and Reform (Thermopolis and Saratoga) |

29,180.36 | 11,926.11 | 17,254.25 | (3) | 11,926.11 | 10,883.89 | 6,370.36 | ||||||||||||

2 Fiscal year coincides with calendar year.

3 Complete information not reported. For 1938-39, $3,924,868.75 available to Division of Parks only.

4 $600 gift, remainder sand and gravel tax.

5 Donations and contingent fund.

6 No funds available.

7 Special appropriations for acquisition and development, Sherwood Island State Park.

8 Highland Hammock trust fund.

9 Donations $2,940.19, other $131.25.

10 Balance in rotary fund $339,454.08, sand and gravel royalty $70,388.89.

11 Special appropriation for C. C. C. participation.

12 Income from fish and game license fees.

13 Special allocation for land acquisition and development.

14 State highway funds from gas and auto license tax.

15 Special appropriation for bathhouse.

16 State highway receipts. Spent on Stats park roads.

Legislative Appropriations. General appropriations are the customary source of funds for recognized public services. This method of obtaining funds for recreation is almost universally accepted at all levels of government. Of all methods it is the most sensitive to public opinion and control.

Fish and Game Fees. In a few of the States where State parks are under the jurisdiction of an agency which also has responsibility for fish and game, a certain proportion of fish and game fees has been allocated for State parks. Until recently the total budget for State parks in Nebraska and Missouri came from this source, and at present this is the only source of State park funds in Kansas. This arrangement has resulted in opposition from the sportsmen and in inadequate financial provision for the park program. Missouri in 1937 and Nebraska in 1938 made specific appropriations for State parks and these States will no longer be dependent on fish and game license receipts. Since the State park program does contribute to the interests of hunters and fishermen through its game protection policy, in stocking and improving streams and by opening these Streams to fishing, it is reasonable that a certain portion of fish and game fees should be allocated to State park work, but the amount should be in approximate relation to the service rendered this interest.

Gasoline Tax, Automobile License Fees, Fines, Etc. In Oregon, where the State Highway Department administers the parks, they are financed from State highway funds which are built up from gasoline taxes and automobile license fees. A State law provides that all parks and recreational grounds must be so situated as to be accessible to and conveniently reached by and from State highways. There must be a relationship between roads and parks, but whether roads should determine the location of parks or parks determine to some extent the location of roads is a pertinent point in State planning.

In Washington, State parks have been supported by 75 percent of the fines and forfeitures collected outside incorporated cities and towns for violations of the motor-vehicle act. A law was passed in the 1939 session of the legislature allocating to the State park funds, in addition to previous allotments, 20 cents from each automobile driver's license fee. This agency also receives income from a shore protection fund.

As in the case of fish and game fees, the State park agency is entitled to a portion of automobile taxes of various kinds since a large proportion of travel is for recreation and State parks are the destination of a considerable number of automobiles. Furthermore, since the roads in a State park are public roads, there is no reason why highway departments should not take responsibility for their construction and upkeep. This arrangement has been made in a number of States and has recently been authorized in relation to Custer State Park, South Dakota. The planning of such roads, however, should and usually does remain the prerogative of the State park authority.

Figure 38.—Rocks and surf, Harris Beach State Park, Oregon.

Bonds. Bonds have been issued by some States for the acquisition and development of parks. California, for instance, issued bonds in the extent of $6,000,000 in 1928, which sum was matched dollar for dollar by gifts from other sources for the acquisition of park lands. Other States have provided for permanent improvement in this manner as is indicated by table B. This has long been an accepted method of financing capital expenditures for various public services by all levels of government.

Special Tax Levy. The special tax levy, in which a definite millage is assessed against property for park and recreational purposes, is a means which has been used for stabilizing the financing of such service in a number of cities. In 1863 the Minnesota Legislature authorized the Board of Park Commissioners of Minneapolis to levy a 1-mill tax for their purposes in the original park act. Other levies have been added from time to time and this millage has been increased until today the following millage taxes are in effect:

| Fund | Rate | Amount of Levy |

| General park fund | 1.5 | $448,354.47 |

| Playground fund | .5 | 117,092.84 |

| Street forestry fund | .05 | 14,363.04 |

| Municipal airport fund | .05 | 27,885.99 |

Jacksonville, Fla., in 1926 obtained authorization for a tax levy of 1 mill for recreation purposes which was increased to 1-1/2 mills in 1937. Los Angeles in 1926 secured a tax levy of .4 mills for the Playground and Recreation Department, which was increased to .6 mills in 1936. In 1926 a tax of .7 mills was provided for the Park Department which is still in effect. In San Francisco, the Recreation Department is supported by a .7-mill tax with provision that the City Council can increase it to 1 mill, and the Park Department receives the proceeds of a 1-mill tax. Other cities have used this method of financing.

The Cook County Forest Preserve District, Illinois, finances its operations to a large extent from a mill tax levy of 9/40, established in 1915.

No State park authority has as yet secured such a mill tax as a means of financing the regular expenditures of its park system, but Indiana in 1923 secured authorization for such a tax for the "acquisition, operation, development, improvement and beautification" of Dunes Park in northwestern Indiana. This tax was in effect for seven consecutive years and provided for a levy of 2 mills on all taxable property in the State. Similar provision was made for the acquisition of Wolf Lake State Park in 1937.

This method of financing, in which a definite millage tax is assessed against property for park and recreational purposes, is important as a means of establishing revenue. Usually the rate of the levy, a maximum return, or both, are established by law. It is a common instrument with cities, counties, and metropolitan districts. Even though subject to fluctuation—dependent on relative completeness of tax collection and on relative stability of valuations—the certainty of returns year after year made possible by this method has great and distinct advantages. It makes possible long-term and orderly planning and programming of acquisition and development, and is an important factor in assuring stability of employment and establishing a planning and administrative organization of high caliber. Legislators at times look askance at special levies, claiming that they tend to make the allocation of available funds less flexible. Despite these objections, a mill tax, where it may be established, appears to be a desirable form of park financing.

Severance Tax. An appropriate special tax for the support of parks and recreation is a tax upon the removal and use or sale of certain natural resources of the country. Taxes on the sale of timber and other forest products is one application of this principle. Indiana uses the entire income received from sales of sand, gravel, coal or minerals from the bed of navigable waters within the boundaries of the State for this purpose. Receipts from this source for the year ending June 30, 1937, amounted to $66,639.32 and in 1936 amounted to $117,578.60. The receipts from this source are deposited in the rotary fund of the State park authority and may be used for any purpose deemed necessary by it. California has provided that 30 percent of the net receipts from the royalty on oil taken from State lands and the ocean shall accrue to a special State park fund. It is anticipated that in the near future the State park division of the Department of Natural Resources will receive the revenue from this source, which it is estimated will amount to $1,250,000. Since there is a growing conviction that natural resources are the gifts of the Creator to all the people, it is fitting that all the people should receive direct benefits from their removal and sale. Recreation, because of its primary importance in contributing physical, mental and spiritual benefits to the people, should be given large consideration in the allotment of revenue from this source.

Sale of Products. State parks under the jurisdiction of forestry agencies usually share in the income from the sale of forestry products, privilege taxes, and fines and forfeitures in connection with the forestry laws. This applies to North Carolina, Maryland, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Florida, and New Hampshire. Ten other States not under forestry departments have authority to sell products as a means of financing. However, since one of the objects in establishing parks is to preserve the natural character of the landscape, commercial exploitation of the natural resources on the area is recognized as contrary to good park policy and thus little can be realized from this source.

Operating Income. Another source of income is that which results from the operation of certain facilities and accommodations to the public on recreational areas. There is rather general acceptance of the policy that only those enterprises will be established in an area which contribute to the enjoyment of the area and which are in keeping with the public interest. It is well to recognize that no park system has ever been made self-supporting through a system of fees and charges and a determined effort in this direction inevitably will restrict the service of the park agency and diminish the public benefits which accrue from it.

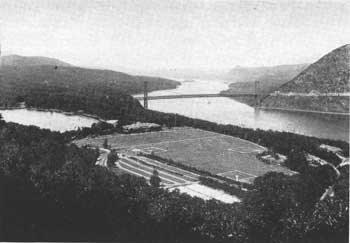

Figure 39.—Aerial view, Jones Beach State

Park, Long Island, New York, showing west bathhouse and swimming pool in foreground.

Commercial enterprises are projected on the profit basis. Governments engage in certain proprietary activities such as the operation of water supply systems and power plants in which it is expected at least that expenses will be met. In the essential functions of Government, however, the primary consideration is public service; and financial returns must be considered subordinate to the purposes for which any particular agency is established. Since provision of opportunity for recreation is an essential function of Government, policies and practices should be determined accordingly. Certain services provided in parks, however, can be considered proprietary. These include the operation of refectories, hotels, restaurants and similar public accommodations as desirable adjuncts to the recreational program. Such services are expected to be self-supporting and may reasonably be expected to show a profit but subject to such public controls as will prevent undesirable advantage being taken of the exclusive opportunity for profit usually enjoyed by the park concessionnaire.

Certain other accommodations may likewise be supplied in connection with the recreational program. In this category are the provision for the checking of clothes and valuables for swimmers, the supplying of cut wood for picnickers, the rental of boats, horses, bicycles, etc. In other words, for services involving the protection of personal property, the consumption of material goods, or the exclusive use of expensive equipment, it is the accepted general practice to make a charge.

From this point on there is the widest possible divergence in the policies and practices of various public recreational agencies. Most agencies strive to render the utmost public service and to keep at a minimum both the number and amount of charges. Some agencies make it practically impossible for the public to enjoy any of the facilities without immediate payment, charging for all parking, the use of picnic tables, and the use of all sports areas and equipment. A few State park agencies charge for admission to the area itself. In a number of parks in one State, a parking fee is charged for every car which remains within the area for more than half an hour. This is tantamount to an entrance fee, since no one can give more than cursory inspection to the area in that time.

Such policies not only seriously limit the service rendered to the public and especially to those most in need of the service, but they are contrary to the purpose for which these agencies were established and, therefore, endanger future public financing. The impression is thereby created among legislators and the public that the agency is not performing an essential public service, but one which is proprietary in character and, therefore, is entitled to less and less support from public taxation.2

2 A full discussion of the policies and practices regarding fees and charges is available in Fees and Charges for Public Recreation, National Park Service, 1939, available from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C., price 40 cents.

In a study of fees and charges for public recreation made by the National Park Service, 158 agencies reported for 1937 a total income of $6,370,625 from fees and charges, which was equivalent to 15.8 percent of their operating expenditures. The 23 State agencies included reported $1,500,697 from this source, which was equivalent to 38.2 percent of their operating expenditures. This source of income represented a figure equivalent to 24.7 percent of the operating expenditures of the county and metropolitan agencies, and 11.1 percent in the case of municipal agencies. The funds available from all sources to the 211 agencies reporting averaged $303,276 for municipal agencies; $416,405 for county or metropolitan agencies; and $102,604 for State agencies. The agencies selected for this study were chosen because they represented well-organized systems.

COOPERATIVE FINANCING

Between States. Because of the fact that population concentration occurs independent of State lines and recreational resources, it will frequently be true that pressing recreational needs of the people of one State can be met best within the borders of another. This would point to the desirability of cooperative financing between States. New York and New Jersey have worked out such an interstate arrangement in connection with the Palisades Interstate Park which straddles the border of the two States, but this idea might be extended to include parks wholly outside a State. Dunes Park in Indiana, for instance, draws 60 percent patronage from Chicago, Ill. It is probable that in a great many instances more adequate recreational opportunity would be provided if cooperative arrangements were made by adjoining States for the acquisition, development, administration, and financing of recreational areas.

Between States and Their Civil Divisions. No State has as yet organized a State-wide service in recreation in cooperation with its civil divisions with a view to bringing a well-rounded recreational program to every citizen in the State. Massachusetts, in 1870, enacted a law which provided for the assessment of cities and towns for the financing of parks serving them, on the basis of population and assessed valuation. A few States have provided service in the technical fields of planning to local units of government. Extension departments of State universities in some instances have provided recreational personnel in particular localities and have furnished information and advice on recreation in connection with rural programs. There is great need, however, for more definite and comprehensive services on the part of State governments in meeting the recreational needs of the people of the State.

Between Governmental Units and Quasi-Public Agencies. In a few instances, State-supported historical societies which coordinate their work with State parks and museums of natural history such as the Bear Mountain Museum render invaluable service in expanding the park program in that field. Specialized services of a quasi-public nature are often available to park authorities. The International Peace Park is being developed by the National Park Service, the State of North Dakota, and International Peace Garden, Inc. The last named is a privately supported group which will have some responsibility for maintenance. Opera associations in St. Louis and Chicago have furnished outdoor opera in public parks, and other privately supported musical associations have furnished varied programs of outstanding quality at Robinhood Dell in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, and at the Watergate and other locations in Washington, D. C. Many State parks are so located that similar arrangements could be made with local civic groups.

GIFTS AND DONATIONS

It is inconceivable that any park programs could ever reach full fruition with out the active support, financial and otherwise, of individuals and groups on a voluntary basis. Once individuals have become cognizant of the worth-whileness of public provision for recreation, generous donations of land and gifts for development and program will augment public funds for these purposes. Noteworthy examples of past philanthropies will illustrate the importance of this source of support. For example, private funds and donations of land contributed a large part of the acreage now available for park and recreational purposes. More than $2,000,000 in cash has been privately contributed to the National Park Service for development purposes. While most of the land under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service has been transferred from the public domain, of the land acquired from private ownership more than one-third (about 300,000 acres, much of it very valuable) has been privately donated or purchased with privately donated funds.

Figure 40.—Palisades Interstate Park, New York and New Jersey. |

A study of donated park and recreational areas conducted by the National Recreation Association several years ago indicated that approximately one-third of the total municipal park acreage had been acquired through gifts. Gifts of land exceed in value all other forms of gifts. One hundred and eight cities reported land donated for parks during the period of 1931-35 with an estimated value of $9,500,000. Sixteen counties reported gifts of land totaling in value $668,350. Gifts other than land to municipal and county park systems totaled $2,677,321 during the five year period 1931-35 inclusive. Information is not available for all state park systems, but in general a great proportion of state park land has been donated. In 28 States which have reported the means of acquisition of State park land, 254,855 acres were acquired by donation as against 229,380 by purchase.

In expending the $6,000,000 realized from the State park bond issue, the State of California required that each dollar be matched, in money or land value, by some other agency or by a citizen or group of citizens. Private donations, particularly for the purchase of redwood areas, provided a large part of the matching funds.

Figure 41.—On the bridle trail, Cook County Forest Preserve District, Illinois. |

Endowments and Trust Funds. Endowments and trust funds have frequently been set up to provide for maintenance and operation in municipal, county and metropolitan parks and in certain instances in the State park field. Dr. Edmund A. Babler State Park in Missouri and Virginia Kendall State Park in Ohio might well serve as a stimulus to this kind of public benefaction. In addition to donation of the land for the Babler Park, a perpetual endowment trust fund of nearly $2,000,000 was set up, the income and revenue from which "shall be used in defraying the expenses of management, maintenance, beautification, further development, and possible enlargement" of the park. Virginia Kendall State Park was bequeathed to the State and a maintenance fund which produces about $40,000 annually has recently become available to the park.

Oglebay Park, eight miles from the city of Wheeling and under the Wheeling Park Commission, serves all the purposes of a State park for an area extending for miles along the Ohio River Valley. It is financed by appropriations from the city of Wheeling, the Sarita Oglebay Russell Endowment, State and Federal funds received through the Agricultural Extension Division of West Virginia University and by Oglebay Institute. The last named organization conducts a varied program on the park and is supported by various types of membership in the institute and by receipts from various activities. In 1938 this organization contributed $40,000 toward the conduct of the park's program.

NON-PROFIT CORPORATIONS

The Mammoth Cave Corporation is a nonprofit organization which operates the hotels and numerous other services and facilities in Mammoth Cave National Park under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service. Receipts over and above expenses are used to purchase land to extend the boundaries of the park. In 1938 nearly $85,000 was available for this purpose.

IMPORTANT CONSIDERATIONS

No recreational program can be successful from any service or financial point of view if it represents the accomplishments only of the paid personnel of an agency. The program must take root in the lives of the people; it must become, in a very real way, their program. When this is true the people themselves will rally to its support if it is endangered. Furthermore, they will elicit the interests of others in the program from day to day and will be a dynamic force in extending its influence and service.

It is well to remember that the maintenance of financial support, whether from tax funds or otherwise, is a day-by-day job. The agency which settles back after the current budget has been passed and gives no thought to the matter until the urgency of the next budget session is upon it, is likely to have a rude awakening at some time or other. There must be constant interpretation of purposes and objectives and the plans and accomplishments of the agency must be kept constantly before the public as well as before those officials and individuals who have primary responsibility for the allocation of funds.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

park-recreation-problem/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 18-May-2016