|

National Park Service

A Study of the Park and Recreation Problem of the United States |

|

Chapter VI:

Legislation

|

BACKGROUND According to the Totalitarian theory of government, people are created for the service of the State. The theory of Democracy is that Government is created for the service of the people. Our Government was founded upon the ideology expressed in the Declaration of Independence as follows: |

|

. . . all men are created equal . . . are endowed by their Creator with certain Inalienable Rights . . . among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness . . . to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men. . . .

This concept of Government was affirmed in the Preamble of the Constitution:

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

In Article I, Section 8, Congress was empowered to finance efforts in the interests of general welfare as follows:

The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general welfare of the United States (Italics supplied.)

James Madison said:

Good government implies two things: first, fidelity to the object of government, which is the happiness of the people, secondly, knowledge of the means by which that object can be attained. Some governments are deficient in both these qualities; most governments are deficient in the first. I scruple to assert, that in American governments too little attention has been paid to the last.

It was more than 100 years after Madison made that statement that American governments seriously addressed themselves to the problem of ascertaining the means by which the happiness of the people might be attained. Social legislation in the main was not given serious and consecutive attention until after 1900. From that date until 1917 advances were made in many public welfare fields. The World War interrupted this trend and only slight gains were made until 1932, when the rending of our economic fabric disclosed the terrific gap between preachment and practice and gave point again to James Madison's words. At that time of uncertainty the appalling awareness of our extreme interdependence upon one another, the feeling of our helplessness as individuals led to a great resurgence of social consciousness and an insistent urge that government muster the resources of the Nation for the happiness and security of the people. This led to a great expansion in the responsibilities and activities of government and a rather frantic seeking of means by which human happiness could be attained. Among other phases of human welfare, public recreation was recognized as one of the effective means.

For the first time the Federal Government entered into a working partnership with the States in a Nation-wide program in this field. This has resulted in an extension of the Federal system of recreational areas to serve a greater number of the citizens of the country, and the authorization of large sums of Federal emergency funds for recreational development and the conduct of recreational programs in all parts of the country. These funds are being spent not only on Federally administered areas but also upon areas under the jurisdiction of State and county, metropolitan and municipal governments.

The State governments, in framing their fundamental laws, likewise placed stress upon their responsibility to provide for a happy day-by-day life for their citizens; in fact the purposes of the pronouncements setting forth the raison d'etre of these governments are identical in meaning and closely follow the phraseology of the Federal Constitution. For instance, the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Virginia states:

That government is, or ought to be, instituted for the common benefit, protection and security of the people, nation or community; of all the various modes and forms of government, that is best which is capable of producing the greatest degree of happiness and safety and is most effective against the danger of maladministration.

Declarations similar in meaning and strikingly familiar in language are found in other State constitutions.

Moreover, a number of State constitutions expressly provide for parks and recreation. For example, the Virginia constitution states—

. . . nor shall this State become a party to or become interested in any work of internal improvement, except public roads and public parks . . .

Another example is found in the Wisconsin constitution, which provides:

The State or any of its cities may acquire by gift, purchase, or condemnation, lands for establishing, laying out, widening, enlarging, and maintaining memorial grounds, streets, squares, parkways, boulevards, parks, playgrounds, sites for public buildings, and reservations in and about and along and leading to any or all of the same . . . and after the establishment, lay-out, and completion of such improvements, may convey any such real estate thus acquired and not necessary for such improvements, with reservations concerning the future use and occupation of such real estate, so as to protect such public works and improvements, and their environs, and to preserve the view, appearance, light, air, and usefulness of such public works.

Parks and Recreation: Essential Governmental Functions. The provision of recreational areas and service by agencies of all levels of government has been recognized in legislation and by the courts as a necessary function of the various governmental units under the obligations assumed in the above pronouncements.

In a case in Kansas in 1927 involving the exercise of the power of eminent domain in acquiring the lands and buildings which comprise the Shawnee Mission as an historic park, and in which the owner of the property contested the action, the Court upheld the action of the State and in the course of the opinion made the following statement:

When life was simple, the power of eminent domain was expended in providing for simple necessities—public buildings, public ways, and other physically indispensable things. With the advancement of civilization new needs multiply. First comes that which is natural, and afterward, that which is spiritual, and cultural needs become just as cogent as the material needs of pioneer days were. The framers of the Constitution of Kansas understood this. The Constitution makes it mandatory upon the legislature to encourage the promotion of intellectual and moral improvement (Art. 6, par. 2). A specific method of encouragement is prescribed—establishment of a uniform system of common schools and schools of higher grade, embracing college and university departments. This method is not exclusive. The legislature must do that much, but it may resort to other methods perfected in the course of social progress. The end to be sub-served by state promotion of intellectual and moral improvement is better citizenship. (State v. Kemp, 124 Kansas, 716.)

In United States v. Gettysburg Elec. R. Co. (160 U. S. 668) the Supreme Court had before it the question of the appropriation of private property for use by the United States in restoring, preserving, and marking the Gettysburg battlefield. In the opinion of the Court, sustaining the appropriation, it was said:

Can it be that the Government is without power to preserve the land, and properly mark out the various sites upon which this struggle took place? Can it not erect the monuments provided for by the acts of Congress, or even take possession of the field of battle in the name and for the benefit of all the citizens of the country for the present and the future? Such a use seems necessarily not only a public use, but one so closely connected with the welfare of the republic itself as to be within the powers granted Congress by the Constitution for the purpose of protecting and preserving the whole country . . .

A ruling was made in Connecticut that "the control of public parks belongs primarily to the State, and municipalities in operating and managing them act as governmental agencies exercising an authority delegated to them by the State." (Epstein v. City of New Haven, 104 Conn. 283, 132 Atl. 467.) This is in keeping with the accepted principle that municipal corporations in their public and political aspect are not only creatures of the State, but are parts of the machinery by which the State conducts its governmental affairs. The following court decisions are in point:

In Indiana it has been held that a city, in establishing a playground within the city limits, and in determining the character of the equipment therefor, was exercising a duty purely governmental. (Indianapolis v. Baker, 72 Ind. App. 323, 125 N. E. 52.)

In Higginson v. Treasurer &c of Boston, Chief Justice Rugg (212, Mass. 589, 590, 1912) said:

Passing from a consideration of the authorities to the underlying principles, which in reason must govern, a park of the nature here in question appears to be for the general public rather than for the municipality in its proprietary capacity. The use of the park is in kind analogous to those confessedly public. It closely resembles roads and bridges. These are open to general public travel without reference to the residence of the traveler. The enjoyment of public parks hardly can be restricted to residents of a particular city or town. They can not be made a source of revenue as may a system of water-works or sewerage or gas, electric light, or markets. Their use by those most needing them might be prevented by any pecuniary charge. . . . Parks in the proper Sense to which the public are regularly admitted have been inseparably connected with a public agency. . . . Although the establishment of this park was permissive and not compulsory, this distinction is not decisive. It is the character of the use which stamps a given municipal venture as public or proprietary. (Tindley v. Salem, 137 Mass. 171, 176.) Adopting this as the test, the dominant aim in the establishment of public parks appears to be the common good of mankind rather than the special gain or private benefit of a particular city or town. The healthful and civilizing influence of parks in and near congested areas of population is of more than local interest and becomes a concern of the State under modern conditions. It relates not only to public health in its narrow sense, but to broader considerations of exercise, refreshment, and enjoyment. We should hesitate to say that the State would be powerless to exert compulsion if a city or town should be found so unmindful of the demands of humanity as to fail to provide itself with adequate public grounds. The municipal spirit which dictates an extensive park system is the same in kind as that which provides fine streets and avenues, beautiful bridges, and ample public schools of a high standard of efficiency, all distinctly public in their nature. The end subserved by these instrumentalities is essentially the same general public good.

In California it has been held that the maintenance of a park by a city for the sole benefit of the public, and not for any profit or benefit to the municipal corporation, is a governmental or public function. (Kellar v. Los Angeles, 179 Cal. 605, 178 P. 505.) The court further held that children's playgrounds and recreational centers established and maintained by a city for the general use of the children of the city do not substantially differ from a public park, stating:

It seems to us that the function in which the city was thus engaged (the conduct of a summer camp) was purely in the exercise of the governmental power and the discharge of the governmental duty of maintaining the health of the children of the city, and was therefore essentially governmental in nature. It will not be questioned that a city is charged with such a duty of sovereignty as that of maintaining the public health, and that in any measures it may adopt solely for that purpose, which are reasonably adopted to that end, it is acting strictly in a governmental capacity.

In Kentucky it has been said:

It may therefore be regarded as settled in this jurisdiction that public parks, maintained and managed without corporate or individual gain or profit, are not only exempt from taxation, but may be created and maintained by taxation. Hence they are essentially public places established for purely public purposes. The right of the city to support public parks by taxation is rested upon the ground that the municipal authorities are charged with the duty of maintaining the public health, and that parks where exercises and recreation can be indulged in, and pure and clean air breathed, contribute largely to the health of the community. Viewing the matter from this standpoint, the parks of the city occupy towards it and its inhabitants the same relation as do hospitals and other public institutions useful and necessary in the preservation of the health, safety and morals of the people. (Board of Park Com'rs v. Prniz, 127, Ky. 460, 105, S. W. 948.)

In Maryland the view is taken that to hold the operation of parks as a proprietary function would be against public policy, "because it would retard the expansion and development of park systems in and around our growing cities, and stifle a gratuitous activity vitally necessary to the health, contentment, and happiness of their inhabitants;" and that "in these days of advanced civilization, in a period when the unfortunate tendency is to abandon the countryside—the haunts of their own youth—and thereby add to the already over-congested metropolitan area, public city parks are almost as necessary for the preservation of the public health as is pure water." (Baltimore v. State, 168 Md. 619, 179 Atl. 169.)

In an opinion rendered by the Supreme Court of Michigan, public parks and recreation are clearly recognized as governmental functions at all levels of government.

Michigan, through its legislature, has recognized the acquisition, improvement and maintenance of free public parks as a governmental function by itself acquiring, improving, and maintaining at State expense, under its appointed board, the Mackinac Island State Park, and independent of the legislature, the people of the State, by adopting the present Constitution, have authorized any city or village to acquire and maintain parks, even without their corporate limits, grouping them with works which involve public health and safety. The Federal Government is also in "the park business" as a governmental function, and whether they be Federal, State, or municipal parks, the beneficial public purpose intended and served by such free recreation grounds for the people and the resultant benefits which justify their free maintenance at public expense as a governmental activity are the same except it be in degree; and in that particular a comparison of the beneficial results to the greatest number of people at large throughout this commonwealth from the free use and enjoyment of Belle Isle City Park and Mackinac Island State Park might indicate the degree is not necessarily in favor of the larger governmental unit.

While, like public schools for education, public parks are primarily provided for the recreation, pleasure, and betterment of the people within the limits of the governmental organizations which maintain them, they are not by legal restraint or custom or in fact solely for the benefits gratuitously offered. Along the lines of facilities which parks afford, playgrounds for healthy exercise, swimming pools, baths, appliances for manual training, and other equipment for balanced physical and mental development, with instructors as to proper use and methods, are now recognized and frequently adopted in the curriculum of our public schools as essentials of education and sanitation, both acknowledged subjects of state concern and governmental activity . . . The constitutionally authorized function this municipality was exercising was without private gain to the corporation or to individuals, for purposes essentially public and of a beneficial character in furtherance of the common welfare in harmony with the general policy of the state, and was in its nature a governmental activity, whether it be put upon the ground of health, education, charity, social betterment by furnishing the people at large free advantages for wholesome recreation and entertainment, or all of them. (Heino v. City of Grand Rapids, 202 Mich. 263, 168 N. W. 512.)

In Rhode Island it has been held that the maintenance of a public park is a discharge of a governmental function—

engaged in the performance of a public service in which it has no particular interest, and from which it derives no special benefit or advantage in its corporate capacity, but which it is bound to see performed in pursuance of a duty imposed by law, for the general welfare of the inhabitants of the community. (Blair v. Granger, 24 R. I. 17, 51 Atl. 1042.)

In Utah it has been held that the maintenance of a public park and the presentation therein of a pageant

are clearly matters of public service for the general and common good, designed exclusively for the social advantages, entertainment, and pleasure of the general public. (Alder v. Salt Lake City, 64 Utah 568, 321 P. 1102.)

In 1936 there was presented to the Supreme Court of North Carolina the question whether, without submitting the question to the voters, a city could issue its bonds for public park purposes without impinging the constitutional provision that—

no county, city, or town or other municipal corporation shall contract any debt, pledge its faith, or loan its credit, nor shall any tax be levied or collected by any officers of the same except for necessary expenses thereof, unless by a vote of the majority of the qualified voters therein.

The court held that an ordinance authorizing a bond issue for development and equipment of parks and playgrounds was a valid exercise of the police power, and that the bonds were for "necessary expenses" within the constitution, thus obviating the necessity for the voters' approval. The court said:

It has been said that "Health is wealth." These parks and playgrounds at all times, and especially in the heat of summer, are a benediction . . . to all the inhabitants of the city. Nothing is more conducive to health and good morals than these recreational places in a thickly settled city. (Atkins et al. v. City of Durham, 210 N. C. 295, 186 S. E. 330.)

Many other decisions could be cited which support the same premise of these decisions, namely, that the provision of recreational service is an essential governmental function, but their effect would be merely cumulative. Decisions holding parks to be proprietary functions have been rendered in Delaware, Missouri, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Texas, West Virginia, and Wyoming. Despite these decisions to the contrary, it is evident that there is general recognition of recreation as a public function of government.

FEDERAL LEGISLATION

Initial Federal legislation subsequent to the adoption of the Constitution recognizing parks and recreation as a national responsibility is found in an act of Congress approved June 30, 1864 (13 Stat. 325), granting to the State of California the "Yosemite Valley" and the "Mariposa Big Trees Grove" upon condition that the areas be held "for public use, resort, and recreation." This was followed by the Act of 1872 (17 Stat. 32) creating the Yellowstone National Park as a "public park or pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people." Subsequent acts similar in character have established additional national parks, battlefield sites, memorials, and parkways.

Figure 42.—Canyon of the Yellowstone River and Lower Falls,

Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming.

The Federal Antiquities Act was approved June 8, 1906 (34 Stat. 225) by which the "President of the United States is authorized in his discretion to declare by public proclamation, historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest that are situated upon the lands owned or controlled by the Government of the United States to be national monuments" and "when such objects are situated upon a tract covered by a bona fide unperfected claim or held in private ownership, the tract . . . may be relinquished to the Government and the Secretary of the Interior is hereby authorized to accept the relinquishment of such tracts in behalf of the Government of the United States." Under this authorization 82 national monuments have been established.

The National Park Service was created by an act approved August 25, 1916 (39 Stat. 535), "to promote and regulate the use of Federal areas known as national parks, monuments and reservations . . . by such means and measures as conform to the fundamental purpose of said parks, monuments, and reservations." Congress defined this purpose as being "to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wildlife therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations."

An act of 1924 (43 Stat. 463), authorized and directed the National Capital Park and Planning Commission (as successor to the then existing National Capital Park Commission) to acquire such lands as were deemed "necessary and desirable" in the District of Columbia and adjacent areas in Maryland and Virginia "for the comprehensive, systematic, and continuous development of park, parkway, and playground systems of the National Capital and its environs." That Congress has viewed the development of the parks in and around Washington as of national rather than mere local benefit is reflected by the Act of 1890 (26 Stat. 492), which established Rock Creek Park "for the benefit and enjoyment of the people of the United States."

By Act of August 21, 1935 (49 Stat. 666), Congress declared it to be a national policy "to preserve for public use historic sites, buildings, and objects of national significance for the inspiration and benefit of the people of the United States" and empowered and directed the Secretary of the Interior through the National Park Service "to survey, investigate, acquire, restore, preserve, maintain, and operate historic and prehistoric sites, buildings, objects, and properties of national significance," and also provide for "cooperative agreements with States, municipal subdivisions, corporations, associations, or individuals to protect, preserve, maintain, or operate" such historic sites.

By Act of June 26, 1936 (49 Stat. 1982), Congress declared it to be the policy of the United States to assist in the construction where Federal interests are involved, but not the maintenance, of works for the improvement and protection of the beaches along the shores of the United States, and to prevent erosion due to the action of the waves, tides, and currents, with the purpose of preventing damage to property along the shores of the United States, and promoting and encouraging the healthful recreation of the people.

The Federal Government has recognized its interest and responsibility in the provision of recreational opportunities in local communities and in the several States as evidenced by legislation passed to meet certain situations. For instance, an Act of 1890 (26 Stat. 91), relating to the reservation and sale of town sites in Oklahoma, made it mandatory that all surveys for such town sites contain reservations for parks. The Act of October 5, 1914 (38 Stat. 727), authorized the Secretary of the Interior to withdraw from other disposition and reserve for county parks, public playgrounds and community centers for the use of the residents upon the lands, such tracts as he might deem advisable (not exceeding 20 acres in any township) in each reclamation project or the several units of such reclamation projects undertaken under the reclamation laws. An Act of June 14, 1926 (44 Stat. 741), authorizes the Secretary of the Interior to withhold from appropriation unreserved nonmineral lands which he has classified as chiefly valuable for recreational purposes and to sell, lease, or exchange to the States for park or recreational purposes in exchange for other lands.

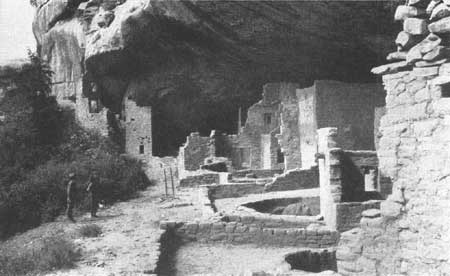

Figure 43.—Spruce Tree House, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado.

By an Act of July 10, 1930 (46 Stat. 1021), Congress enunciated the principle of conserving the natural beauty of shore lines for recreational use, and applied it specifically to all Federal lands which border upon any boundary, lake or stream contiguous to certain described areas situated in Minnesota or any other lake or stream which was then or eventually is to be in general use for boat or canoe travel, and for the purpose of carrying out this principle, generally prohibited logging of all such shores to a depth of 400 feet from the natural water line.

It is the general practice for Congress to authorize departments of the Federal Government by special act to convey to States and their civil divisions, lands, including improvements, for public park and recreational purposes. When such conveyances are made, it is stipulated that the States and local communities must assume the necessary obligations in carrying out the purposes of the grant. In case of nonperformance of the obligation within a certain period any property so conveyed reverts to the Federal Government.

Further recognition of the importance of recreation from a national viewpoint and the necessity for cooperative action between the Federal Government and the States and their civil divisions is reflected in the Act of June 23, 1936 (49 Stat. 1894) which authorized and directed the Secretary of the Interior, through the National Park Service, to make a study of park, parkway, and recreational-area programs, areas, and facilities and to cooperate with the States and their civil divisions in planning adequate and coordinated recreational systems.

It is apparent that the trend of Federal legislation is to broaden the responsibility of the Federal Government, not only in respect to the administration of areas and facilities directly under its supervision, but also in extending the recreational movement by cooperation with States and local communities in a Nation-wide program.

Figure 44.—On the beach, Cape Hatteras National Seashore Recreational

Area Project, North Carolina.

HISTORY OF STATE PARK LEGISLATION

Legislation dealing with the establishment, development, and operation of State parks—with a history of virtually the same length as that of national park legislation—has naturally reflected the changed, and changing concept of the scope of importance of the State recreational undertaking.

The earliest State parks, starting with the Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove in California, were created by individual and special legislation. Since neither the phrase nor the concept, "State park system" existed, the creation of a park almost invariably involved the concurrent establishment of some agency, usually a board or commission, to administer that park alone. Even long after many States had embarked on the creation of "systems," there were survivals of these single-park commissions, set up in law several decades previously, and they survive today in Massachusetts—perhaps the earliest State to give currency to the idea of a system—Pennsylvania and several other States. A separate commission still administers Mackinac Island State Park in Michigan. The California Redwood Park was separately administered until the State Park Commission was created in 1927; Watkins Glen and other New York State areas were individually administered under laws passed many years before, until the present system of regional park commissions was established in 1924.

The State of Massachusetts established a Board of Park Commissioners by an act passed in 1870, but this board was concerned with the ultimate Boston Metropolitan Park system rather than with a State-wide system of parks, and the present Boston Metropolitan District Commission offers the interesting anomaly of a State agency administering a metropolitan system.

We have in this early legislation—more comprehensive than anything, State or Federal, which had found its way to the statute books up to that time—many features since reflected in other park legislation, State and local. These include the "staggered" terms of office for the commissioners, special assessments against benefited real estate, and a very broad grant of police power.

The first act passed by any State creating an agency charged with administration of all State parks and related areas was apparently that of Wisconsin which created a State Park Commission in 1907.

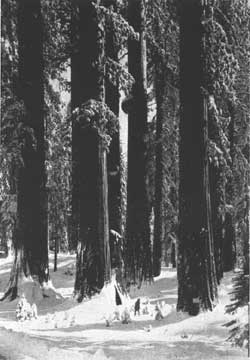

Figure 45.—Big Trees of the Mariposa Grove, Yosemite National Park, California |

It is quite understandable that the earliest State parks were individually created by legislation. Increasingly, as State-wide administrative agencies have been established, the power of creating new parks has been handed over to them, on the reasonable assumption that an agency primarily concerned with parks would do a better job of selection than a legislature would do. Even after this came to be a generally recognized power, legislatures continued, and continue from time to time, wisely or unwisely, to pass special legislation of this sort. Minnesota, with several properties that were classed a few years ago as "city State parks" exemplified the unhappy result of this haphazard and unscientific method of selection. However, it can be matched in a number of States where the State park agency has been equally impotent in resisting local pressures or lacking in ability to say "no" to prospective donors of park lands.

Early legislative grants of authority to park boards or commissions were generally very limited in scope, and, with the exception of those States which have come into this field within the past five or six years, have evolved from the simplest grant of power to administer to a gradual extension of power to meet needs as experience indicated that needs existed.

This extension of power is perhaps best exemplified with respect to exercise of the power of eminent domain. This power, old in law in its relation to undertakings acknowledged to be publicly necessary, has been extended rather cautiously in the field of State parks and even today nearly a third of the State park agencies do not possess it.

Legislation providing for what might be called a State park survey, recognizing the need of park planning on a State-wide scale, dated from an act of the Wisconsin legislature passed in 1907 which made possible a study by John Nolen in 1909. General authorizations to investigate prospective or desirable park areas or to make State studies have gradually found their way into the park laws of other States, though the Olmsted survey of California in 1928 was the result of a special legislative authorization and appropriation, as was the Iowa conservation study of Jacob L. Crane, Jr., carried on in 1931 and 1932.

The trend toward creation of departments of conservation, or, as Georgia and California call them, natural resources, or toward a consolidation of more than one conservation activity under a single person or group, has gained considerable momentum in the last decade. During the past five or six years there has been an increasing tendency also, in those States which started by placing parks under the State forestry authority, to give them coordinate status with forestry. Minnesota, Georgia, Tennessee, and more recently Alabama, are among the States which exemplify this trend. A similar trend toward coordinate status, from one of subordination to the fish and game department, is exemplified in Missouri.

State park legislation in those States new in the field has recently tended to tie in with more or less comprehensive legislation affecting the whole conservation field. Cases in point are Tennessee and Georgia. Until its 1937 act was passed, the latter had no park legislation.

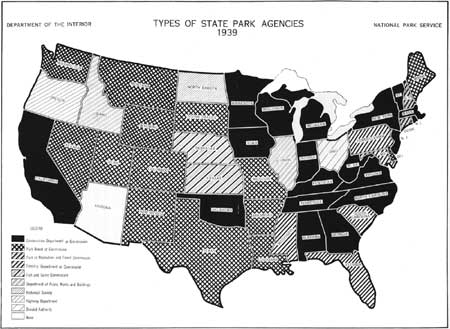

Figure 46. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

An interesting trend in relationships between park authorities and other State agencies is indicated by legislation, most of it approved during the past decade, which authorizes State highway departments to construct roads to and in State park areas, using highway rather than park funds. This authorization is, of course, highly desirable so long as decision as to location and character remains with the park authority.

A related trend is that which tends to bring counties and cities into a cooperative relationship with the State, either for actual administration of parks which mainly benefit local populations, or as contributors to the support of parks so located.

PRESENT STATUS OF STATE PARK LEGISLATION

Most of the legislation under which the present primary State agencies are authorized to function has been passed in the last decade. As shown in the following tabulation, 26 States have either passed their initial legislation establishing a State-wide organization for park work or have completely reorganized the basis of their functioning since 1930. Of these, only three had a State-wide park organization before that time. New Hampshire is the only State which had established its present organization before 1910, and the Connecticut, Idaho, Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Indiana State park agencies are operating under essentially the same legislative authority passed between 1910 and 1920. As indicated in the same tabulation, 14 States established their present State park agencies in the period between 1920 and 1930.

Year of establishment of present State park agencies

| 1900-10 | 1910-20 | 1920-30 | 1930- | |

| Number of agencies | 1 | 6 | 14 | 26 |

Thus, it is evident that few State park agencies have had long experience under existing legislation and therefore there is continual legislative activity with respect to this public service. In comparison with agencies which have been established for a longer period of time, it is to be expected that the scope and objectives of State park organizations, as well as their form of organization and modus operandi, have not been so definitely determined.

In the following tabulation the frequency of various types of State park organizations is shown, and on the map (type of State park agencies), page 112, their distribution is presented. Arizona has made no provision for a State park organization. Colorado passed an act in 1937 but has established no park organization.

It will be noted also that in three States in which there is a department of conservation this agency does not have charge of all State parks, but that other agencies or independent commissions have control of one or more of them. This is also true in the case of two States where a State park board is the primary authority and of one where the forestry department is responsible for this function.

From the map previously referred to it is evident that departments of conservation occur with a greater relative frequency east of the Mississippi River, while State park boards or commissions are more usual west of that dividing line.

Types of Primary State Park Agencies

| Department of conservation or natural resources | State park board or commission | Forestry department | Forestry, fish and game commission | Park or recreation and forest commission | Department of public works | Highway commission | Historical society | Divided authority | None | ||||||

| Total | Unified | Divided | Total | Unified | Divided | Total | Unified | Divided | |||||||

| 19 | 16 | 3 | 13 | 11 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

In many States forestry and fish and game departments are authorized to acquire and administer areas for recreational purposes supplementing the function of the primary agency.

As shown in the following tabulation, 10 primary State park agencies have an executive type of organization, while the board or commission form has been adopted in 37 States. In the former the responsibility for the formulation of policies is vested in an individual executive or administrator, while in the latter the board or commission has this authority.

Administrative provisions for primary State park agencies

| Executive | Board or commission | ||||||||||||||||||

| Total | Number of members | Number ex-officio | Term of office in years | ||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8-10 | 13 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | Indefinite | |||

| Number of agencies | 10 | 35 | 9 | 1 | 15 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 10 | 1 | 7 |

From the above tabulation it will be noted that these boards or commissions are composed of a varying number of members. Maryland and New York were not tabulated, since in the former the board of regents of the State university is the park authority, while in the latter State the work is organized into 11 regions of which 10 are under regional park commissions, the membership of these varying from 3 to 10 members.

All primary State park agencies have power to develop and maintain recreational areas; however, as revealed in the following table, some of them lack certain powers necessary to the proper growth and functioning of their systems.

Powers and duties of State park agencies

| Land acquisition | Development | Operation | |||||||||||||

| Purchase | Gift | Tax version | Devise | Eminent domain | Lease | Designation of State land | Exchange of land | Sale of bonds | Maintenance | Leasing facilities | Granting concessions | Making rules | Enforcing regulations | ||

| Number of agencies | 41 | 43 | 8 | 26 | 34 | 24 | 12 | 8 | 3 | 47 | 47 | 39 | 33 | 43 | 42 |

By virtue of their establishment as agencies of State governments, all State park authorities may receive and expend appropriations; however, there is considerable variety in other provisions with regard to financing, as indicated by the following tabulation:

Powers and duties of State park agencies

| Methods of financing | Disposition of income | ||||||||||||

| General appropriation |

Fees and charges |

Trust funds |

Gift | Sale of products |

Fines and forfeitures |

Sale of land |

Sand and gravel tax |

Rental of land |

Spent by department |

Returned to general treasury |

|||

| Total | Reappropriated | ||||||||||||

| Yes | No | ||||||||||||

| Number of agencies | 47 | 30 | 19 | 35 | 20 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 40 | 28 | 12 |

Increased attention has been given in recent years to the extension of the cooperative powers of the various agencies with other States, local governments, the Federal Government, other State departments, and private persons. Due to the increased concern of the Federal Government in this field of public service, and due to recently inaugurated cooperative programs with the States, much legislation enabling them to take advantage of this Federal aid has been enacted.

A few have various powers to cooperate with other departments and with private persons, as is shown in the following tabulation, and it is evident that the greatest deficiency is in the legal provision necessary for cooperative action between States.

Cooperative powers of primary State park

agencies

[Number of agencies]

| With | General powers |

Acquisition | Maintenance | Exchange of lands | Transfer of lands |

| Other States | 2 | 3 | 6 | ||

| Local Governments | 4 | 17 | 12 | 6 | 6 |

| Federal Government | 5 | 20 | 17 | 4 | 3 |

| Other departments | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 3 |

| Private persons | 3 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 3 |

INTERSTATE COMPACTS

The United States Constitution expressly provides that no State can, without the consent of Congress, enter into any agreement or compact with another State. Subject to such consent, however, it is well settled that the States may enter into any compact or agreement they see fit with each other. But the Constitution does not state when the consent of Congress must be given; whether it must precede or may follow the compact made, or whether it must be expressed or may be implied.

In general it may be said that no compact between States has been invalidated by reason of the absence of Federal consent. The presumption is that any agreement between two States requires the approval of Congress, subject to a showing that it is not in conflict with any Federal interest. The form of consent, however, is not fixed, and may precede or follow the agreement, and, in some cases, may be implied.

While it is thus open to some question whether the assent of Congress is required to every possible kind of compact or agreement which two or more States may make with each other, all doubt on the question of compacts or agreements respecting park, parkway, and recreational areas has been definitely removed by the act of Congress approved June 23, 1936 (49 Stat. 1894), which provides as follows (section 3):

The consent of Congress is hereby given to any two or more States to negotiate or enter into compacts or agreements with one another with reference to planning, establishing, developing, improving, and maintaining any park, parkway, or recreational area. No such compact or agreement shall be effective until approved by the legislatures of the several States which are parties thereto and by the Congress of the United States.

This enactment would appear to reflect the sense of Congress that such compacts properly require its consent and approval; that a Federal interest is involved. However that may be, in giving its prior consent to the negotiating and concluding of such compacts, the enactment definitely reflects a recognition by the Federal Government of the importance of interstate compacts in the field of recreation.

Interstate compacts as a means of furthering the mutual interests of the participating States have long been resorted to. Such agreements have been made since the formation of the Constitution, and, indeed, even before its adoption. But no compact respecting any park, parkway, or recreational area had been concluded prior to 1937, at which time the Palisades Interstate Park Commission was created as a joint corporate municipal instrumentality of the States of New York and New Jersey to manage and operate both the New York and New Jersey sections of the Palisades Interstate Park. This compact was subsequently ratified by the Seventy-fifth Congress. The same Congress also approved an interstate compact or agreement between the State of Ohio and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania relating to the development, use and control of the Pymatuning Lake for fishing, hunting, and recreational purposes, and which had previously been ratified and approved by the respective General Assemblies.

Palisades Interstate Park was established in 1900. Under the New York enactment provision was made for a board of ten commissioners, five of whom were required to be citizens of the State of New York, and five of whom may be residents of the State of New Jersey. Under the provisions of the New Jersey enactment provision was likewise made for ten commissioners, five of whom were required to be citizens of that State. In laying out and maintaining the park, each Commission was directed to give regard to the laying out and maintenance of such park as may be established by the other State along the Palisades and Hudson River, so as to form, as far as may be, a continuous park.

The relationship thus created has been referred to as an interstate compact. This, however, is erroneous. While it was the obvious purpose, and has been the practice, to appoint identical members to the two separate commissions, this policy rested upon comity, and without legal assurance that it would be continued. It was this lack of permanency, together with administrative and operating problems which had developed during the 36 years of the park's existence, that led to the adoption of the compact.

Resort to interstate compacts as a means of meeting the increasing demand for additional and extensive park, parkway, and recreational areas is feasible, logical, and of distinct advantage to the participating States. There are many interstate areas throughout the Nation possessing inherent or potential park and recreational values, but which, because of legal and practical barriers, cannot be acquired in entirety by any one State. Where territorial barriers preclude one State from acting alone, a single authority makes possible acquisition of the area as a unit. Once acquired, permanency of administration is assured. Administration, development, and maintenance of the area as a single unit by a single authority, equally representative of the participating States, insures uniformity in keeping with the highest park standards, and from which substantial economies should be realized. Cooperation with other agencies, Federal, State, and local, is simplified. Police officers will be unhampered by State boundary lines. The advantages of a mobile police force, with uniform jurisdiction and authority over the whole area, are obvious. Matters of personnel, taxation, rules, orders, regulations, gifts, trusts, charges, revenue, and kindred matters commonly attending park administration and operation, readily lend themselves to definite and satisfactory solution. No participating State need surrender or subordinate its powers or prerogatives to the other. Authority deemed incompatible with the purposes and objectives of the compact may be withheld. Appropriations, both as to amount and purpose, are determinable by the legislature of each State. While a primary purpose of such compacts is to insure permanency of administration, it is open to the participating States to stipulate the terms upon which the compact may be terminated. On the other hand, added authorities and duties may be conferred by a participating State, to be exercised exclusively within its territorial limits, without the necessity of concurrence by the other. Additional jurisdiction, authority, and duties may be conferred by action of the participating States. The compact, once adopted, becomes a contract protected by the Federal Constitution against legislation impairing its obligations.

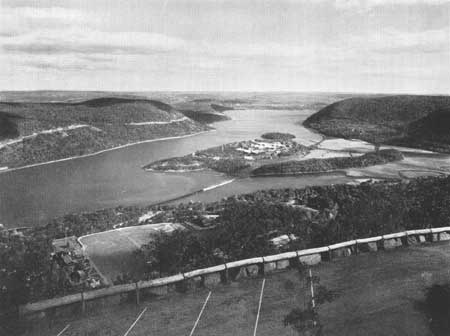

Figure 47.—Palisades Interstate Park, New York and New Jersey.

ENABLING LEGISLATION FOR LOCAL UNITS OF GOVERNMENT

The power to establish public park and recreational departments, and through them to provide recreational services, is conferred upon local governmental units in several forms. In a number of States the power is expressed in the constitution. In others the constitution confers home rule authority. However, the latter authority generally is granted only to incorporated municipalities of substantial population; and as the necessity for recreational authority became more generally recognized, other governmental units, both incorporated and unincorporated, were confronted with the necessity of seeking passage of general or special acts empowering them to render recreational services.

In recent years recreation has been recognized as one of the important municipal functions; consequently, in the acts granting charters to municipalities provision has been made for park and recreational systems. In some cases their form of organization has been specified in the city charter and occasionally more detailed provisions concerning their method of operation. Today the municipal charter, either by its original provisions or by amendments, is the most prevalent means of providing for the establishment of public park and recreational systems.

As recreational programs developed, it became evident that the needs of the people of a city could not be satisfactorily met within the limits of the municipal boundaries, and as a result special legislation was sought and passed creating metropolitan park districts, or empowering the cities or other units to acquire property and conduct activities beyond their boundaries.

Agencies entrusted with other functions of government have felt the desirability for a similar extension of their facilities and activities so that metropolitan utility districts, conservancy districts, etc., have been established. Often these metropolitan districts related to different functions are established with the same city as a nucleus, but their boundaries are not coterminous. It would appear to be a sound policy in establishing such districts to consider the whole field of social function so that such a district might serve all functions which require such an extension of influence.

It is still necessary in a number of States for local governmental units to secure special legislation for the establishment of park and recreational departments, or to extend the service of those departments beyond their borders. It is highly desirable that adequate legislation of a general nature be passed in those States which have not already done so, empowering cities and towns of all classes, as well as counties, townships, etc., to establish park and recreational departments and to perform all necessary functions within and outside their boundaries.

As the concept of the scope of a comprehensive recreational program embracing a multiplicity of activities based upon the variety of interests of people of all ages and inclinations has constantly enlarged, it has become evident that a similar diversity of areas and facilities is necessary to its successful functioning. In the early days of the movement, frequently playground departments were established which very often operated a limited program for the period of the school vacation and included only activities for children. Park boards very often did not provide leadership for a recreational program, and often school boards considered that their responsibility for recreation extended only to the pupils in their curricular and extracurricular activities. In recent years it is generally accepted that the facilities under the jurisdiction of the park boards and school boards should be available for community recreational activities. This often necessitates additional legislation expanding the function of these agencies or creating a recreational department with authority to conduct a program using all municipally owned areas and facilities suited to this purpose. This department is frequently governed by a recreational board or commission, and often provision is made for representation on this board of the various agencies having suitable facilities under their jurisdiction, together with other citizens.

General enabling acts should, therefore, provide for the establishment of the recreational department as a primary agency with authority to acquire areas by means of purchase, gift, devise, and other methods, to improve and develop them, to construct facilities and to conduct a program of activities for the benefit of the citizens of the particular governmental unit on any suitable area or in connection with any facility within or outside the boundaries of the governmental unit.

Provision should be made for the financing of the department through appropriation, gift, bequest, trust funds, through the issuance of bonds, a millage tax, and other means. Provision should be made for a minimum and maximum millage and such funds should be definitely allocated for the purposes of the recreational department and for no other purpose. Provision should also be made for the recreational department to enter into arrangements with other departments of the governmental units, other lesser governmental units, the State, and with the Federal Government in the acquisition, development, and operation of recreational areas and facilities, in the conduct of recreational programs, and in such activities as would promote the recreational movement.

ELEMENTS OF DESIRABLE LEGISLATION

The purpose of recreational legislation is to provide a legal structure through which park and recreational agencies may be established with all the powers and responsibilities necessary to their effective functioning in rendering an adequate and comprehensive service in accordance with the best thought and practice in this field.

Scope. It is evident from a study of the basic Federal and State legislation that much of it is inadequate and limited in scope in view of the present-day recognition of the importance of recreation as a means by which the happiness of the people may be attained. Many Federal agencies are rendering valuable recreational service under only implied authority or lack of clearly defined authority in this field. At present there is no Federal legislation adequate to provide a comprehensive and continuous service to the people through definite working relationships with public recreational agencies at all levels of government.

In only a few States is there specific authority for agencies in this field to function beyond the boundaries of the particular areas which they administer. The Missouri State Park Board is empowered to exercise its powers "for the recreation of the people of the State" and the Massachusetts Department of Conservation is entrusted with the "advancement of recreation and conservation interests and policies." Other legislation generally provides for the exercise of responsibilities regarding recreation on the areas under the administration of the agency and the acquisition of such areas. It is becoming increasingly evident that in order adequately to meet the needs of the people, State recreational agencies must render a more comprehensive service directly and through minor governmental units.

Objectives. There must be a clearly stated major purpose or objective of the thing to be done or the service to be performed and its relationship to the public welfare. The scope and responsibilities of the agency should be clearly defined so that its field of effort may be thoroughly understood. This will restrain dispersion of effort, discourage demands upon the agency to engage in extraneous activities, and minimize duplication of the efforts of other agencies.

The objectives of the State park departments are well expressed in some of the enabling legislation. Michigan, for instance, sets forth the purpose of its Department of Conservation as it relates to parks, as "to acquire, maintain, and make available for the free use of the public, open spaces for recreation"; in Virginia legislation, the purpose stated is "to acquire areas of scenic beauty, recreational utility, historic interest, etc., to be preserved for the use, health, education, and pleasure of the people." The Arkansas law expressed it, "to select and acquire areas of natural features, scenic beauty, and historical interest; promote health and pleasure through education and recreation." Some laws, on the other hand, simply provide for the acquisition, control, and management of State parks and parkways without defining their objectives. It is of primary importance that the objective for which the department is created be clearly set forth in the legislation.

Status of Department. The provision of parks and recreation is of such importance to the public interest and the technique of development and operation is so specialized that it should be recognized as a primary function of the State government, coordinate with other major services. If the administration of State parks is established as an independent agency under a board or commission it should have the status of other major departments. On the other hand, if their administration is organized as a division of a conservation department, it should be on a coordinate basis with such functions as forestry, fish, game, etc.

Integration of State Park Administration. The administration of State parks should be unified into a State-wide system in the interest of economy as well as in the interest of achieving the best results in serving the people.

Organization. The organic act must provide for the basic features of good internal organization and for all powers necessary to the effective functioning of the agency in rendering various services which contribute to the realization of its objectives. These requirements are discussed under "Administration."

General Powers. The agency should determine the policies of the department, and, if a board or commission, should select the executive officer and, upon recommendation of this executive, the heads of all divisions. It should also have power to make and enforce rules and regulations for the governing of its own employees and especially for the protection, care, and use of the areas it administers.

Term of Office. The term of office of the board members should be staggered so that not more than one or two members will go out of office at one time. This tends to stabilize policy and to assure continuity of service by satisfactory employed personnel, and makes possible long-range planning that has a fair chance of accomplishment.

Qualifications. Members should be selected for the board or commission because of their understanding of and demonstrated interest in parks and recreation.

Ex Officio Members. While it is recognized that in some cases it is expedient to have ex officio members on the board, on the whole it is not a desirable practice, particularly if members so selected are sufficient in number to dominate, for the following reasons:

1. The work in connection with parks and recreation is so important that it should be the primary official interest of those serving on the board or commission.

2. The work requires the enthusiasm of lay people whose motivation is a sincere interest in the movement.

3. Public officials have absorbing tasks in connection with their primary responsibilities and are generally unable to give the park and recreational work the time and attention it deserves.

Where it is considered necessary to have ex officio members on the board, it is preferable that they be nonvoting members.

Advisory Board. In lieu of the board or commission, the administration of State parks may be provided for by the establishment of a department with a commissioner responsible directly to the Governor, or as a major division of a department of conservation with or without a supervisory board. In case no supervisory board is provided for, citizenship participation obtained by appointment of a central advisory board, and/or regional or district advisory boards, appears to have definite advantages so long as their purely advisory function is fully understood. These latter would have responsibility for furtherance of the State park movement in a definite section of the State.

The Executive. The executive of a conservation department should be required to have demonstrated his administrative ability and to have a broad general understanding of the purpose and scope of all phases of conservation activity.

The director of park and recreational services should have demonstrated executive ability, and actual experience and training in the conduct of park and recreational systems involving both physical development and program. These qualifications should be embodied in the legislation.

Financing. Since parks and recreation constitute a public service, emphasis should be placed upon appropriations from the State treasury as a basic means of support. The department should have authority to make charges for special services, the income from which might be made available for park purposes. The department should also have authority to conduct and operate such services as are necessary for the comfort and convenience of the public. It is desirable, if possible, to secure support through a special tax. This has proved a satisfactory method of financing in many cities and metropolitan areas and in a few States. Provision should be made also for the acceptance of gifts and the establishment of trust funds through which areas may be secured and developed and the program enriched.

Land Acquisition. The law should permit the department to acquire real property by every possible means. This includes purchase, gift, tax reversion, devise, eminent domain, lease, designation of State land, or otherwise. "Real property" should be defined to include land under water as well as upland, and all other property commonly or legally defined as real property. The law should provide that acceptance of gifts or devises of land be in the discretion of the administering agency.

It is essential in working out a properly distributed system that the State park agency have the power to take land by eminent domain. The procedure varies in different States where park agencies or conservation departments have this power. It has been found in several States that the procedure of entry and appropriation whereby the State deposits the appraised value of the land with a court and immediately enters upon the land and develops it, is sometimes advantageous. This method avoids unnecessary delay in acquisition and use of lands.

Power to Cooperate. In government all services are or should be conducted in the interests of the people as a whole. There is always the necessity, therefore, to provide through the legal structure of a particular service for cooperative powers with other agencies of government. Such cooperative devices are essentials in good government.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

park-recreation-problem/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 18-May-2016