NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Park Structures and Facilities

|

|

BRIDGES and CULVERTS

BRIDGES IN PARKS include foot, bridle trail, and

vehicle bridges of widely varying widths, spans, heights, and types of

construction. In the interest of limiting the classifications within

this compilation, the less frequent underpass and the minor culvert are

embraced within this section.

In outward appearance, the bridge calls most

importantly for visible assurance of strength and stability. To be

entirely successful, it is not enough for the bridge to be functionally

adequate within the exact knowledge of the engineer; it must proclaim

itself so to the inexact instincts of the layman. In gesture to the lay

concept of structural sufficiency, it is pardonable park practice to

venture well beyond sheer engineering perfection in the scaling of

materials to stresses and strains.

The attainment of "the little more" that is so

desired by those who would have an eye-appeal scale brought to the

slide-rule, is all too rare in park bridges. Rather is there a too

prevalent flimsiness, ocular rather than structural. Considerably fewer

bridges fail to satisfy by seeming too ponderous for their function.

After the attainment of a sufficiency in material

pleasing to the eye, the next demand to be made upon bridges would be

for variety, avoiding the commonplace at one extreme, and the fantastic

at the other. The ranges of use, span and height, and the broad fields

of materials, arch and truss forms, local practices—among other

variety-making possibilities—promise endless combinations and

cross-combinations that could make for such individuality among bridges

that none need ever appear the close counterpart of another.

This presentation seeks merely to focus on the

characteristics that bring to bridges the most promise of compatibility

with natural environment. There is elsewhere abundant information,

including diagrams, rules and formulae, for the design of structurally

enduring bridges. Much more limited is the field of source material that

concerns itself with bridges that, by reason of appropriateness to

natural environment, truly deserve to endure. There are far too many

bridges which, after breaking every commandment for beauty and fitness,

seem to have sought to wash away all sins through the awful virtue of

permanence. Such penitent bridges should have no place in our parks. The

quality of permanence cannot be considered a virtue in itself. Unless

every other desirable virtue, big or little, is present, permanence is

only a vicious attribute.

In general, bridges of stone or timber appear more

indigenous to our natural parks than spans of steel or concrete, just as

the reverse is probably true for bridges in urban locations or in

connection with broad main highways. Probably there are few structures

so discordant in a wilderness environment as bridges of exposed steel

construction.

Too great "slickness" of masonry or timber technique

is certain to depreciate the value of these materials for park bridges.

Rugged and informal simplicity in use is indisputably the specification

for their proper employment in bridges.

In no park structure more than bridges is it of such

importance to steer clear of the common errors in masonry. Shapeless

stones laid up in the manner of mosaic are abhorrent in the extreme. In

bridges particularly is there merit in horizontal coursing, breaking of

vertical joints, variety in size of stones—all the principles

productive of sound construction and pleasing appearance in any use of

masonry. The curve of the arch, the size of the pier, the height of the

masonry above the crown of the arch are all of great importance to the

success of the masonry bridge.

Timber bridges may utilize round or squared members

to agreeable results. Squared timbers gain mightily in park-like

characteristic when hand-hewn. A common fault in bridges is the too

abrupt termination of the parapet, railing, or wing wall. These should

carry well beyond the abutments.

In general disfavor for park use are bridges of the

open wood truss type. There seem to be no arguments to their advantage,

while many are raised against them. In spite of most careful detailing

to prevent water entering and lying in the joints, this is hard to

overcome entirely. Shrinking of the timbers, rack under impact and

strain, and rot developing in the opening joints speed the deterioration

of this type of construction. It is short-lived and soon unsafe.

The culvert is too often handled as a conspicuous

bridge, when in reality it is merely a retaining wall pierced by a

drain. The facing of the culvert, like the treatment of almost every

other facility in natural parks, should be first and always informal and

inconspicuous. Facing and culvert proper should be adequate in materials

and in workmanship so that once constructed both can be forgotten and

make no demands upon maintenance appropriations.

The culvert proper is sometimes of local stone when

this is abundant and workable, but if, as is more frequently the case,

it is of concrete or of galvanized iron, reasonable concealment of the

fact is to be striven for. The retaining wall that is the end wall or

facing of the culvert should avoid disclosing that it is a mere veneer

by extending well into the culvert opening. Natural rock is certainly

the preferred material for the end walls. It may be laid either in

mortar, or dry, but the latter method of laying to be lasting should be

undertaken only when the available stone is of suitably large size.

If stone is not available locally or from within a

reasonable distance, concrete or wood must be resorted to in

constructing the retaining wall. Either is an unsatisfactory substitute

for the stone wall—concrete because of its harsh surface, and lack

of permanence if inexpertly mixed, and wood because of its tendency to

deteriorate rapidly under conditions of moisture.

As much care should be given to the design and

execution of culvert end walls as to other park structures. Usual

mistakes are insufficient care in the handling of mortar, resulting in

sloppy joints, and lack of variety in stone sizes, leading to monotony

and formality of surface pattern. These faults are common to much

contemporary stone work, not limited to park construction only.

|

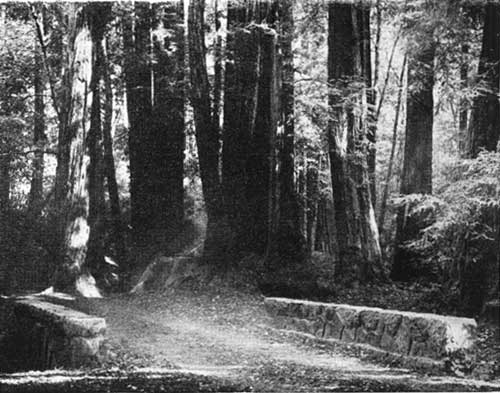

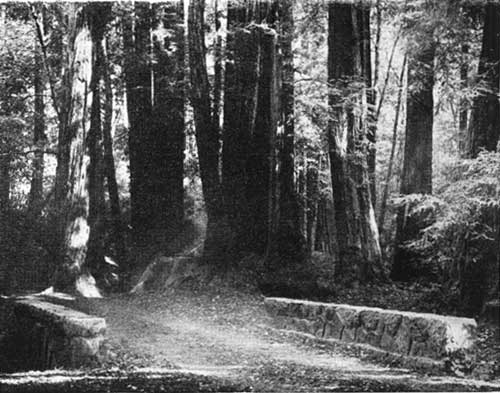

BRIDGE, WESTCHESTER COUNTY, NEW YORK

"Top flight" in all details that make

a masonry bridge truly a delight to the eye and assimilable in a haunt

of Nature. If the information regarding this example is accurate, it is

relayed here with some embarrassment. It is said to be an ancient

structure—not a consciously produced bridge of park implications.

Achievement will be considerable when, purposing to create park bridges

of equivalent distinction, actual accomplishment is more the rule and

less the exception.

|

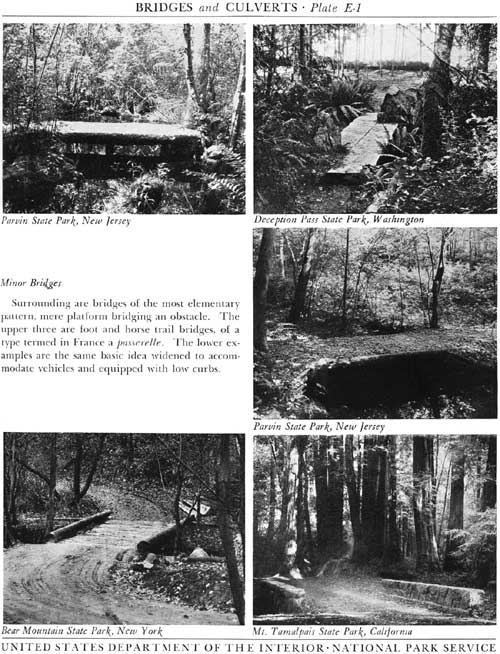

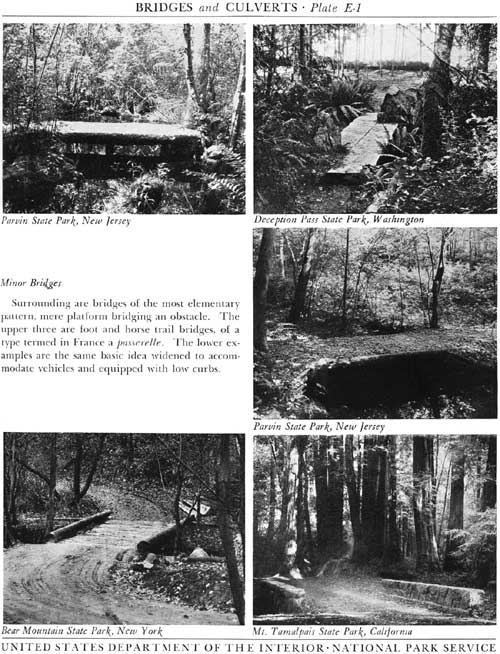

Minor Bridges

Surrounding are bridges of the most elementary

pattern, mere platform bridging an obstacle. The upper three are foot

and horse trail bridges, of a type termed in France a passerelle.

The lower examples are the same basic idea widened to accommodate

vehicles and equipped with low curbs.

|

|

Plate E-1 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Parvin State Park, New Jersey

|

|

|

Deception Pass State Park, Washington

|

|

|

Parvin State Park, New Jersey

|

|

|

Bear Mountain State Park, New York

|

|

|

Mount Tamalpais State Park, California

|

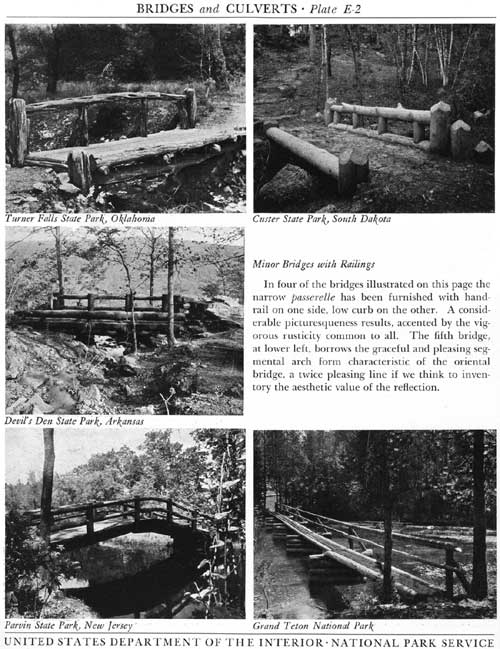

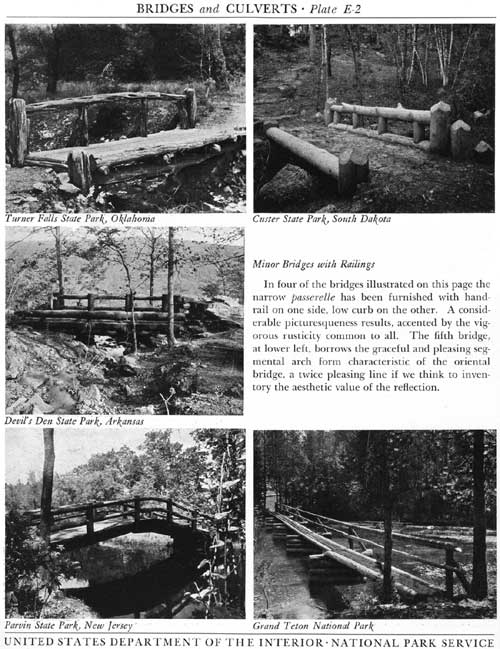

Minor Bridges with Railings

In four of the bridges illustrated on this page the

narrow passerelle has been furnished with hand rail on one side,

low curb on the other. A considerable picturesqueness results, accented

by the vigorous rusticity common to all. The fifth bridge, at lower

left, borrows the graceful and pleasing segmental arch form

characteristic of the oriental bridge, a twice pleasing line if we think

to inventory the aesthetic value of the reflection.

|

|

Plate E-2 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Turner Falls State Park, Oklahoma

|

|

|

Custer State Park, South Dakota

|

|

|

Devil's Den State Park, Arkansas

|

|

|

Parvin State Park, New Jersey

|

|

|

Grand Teton National Park

|

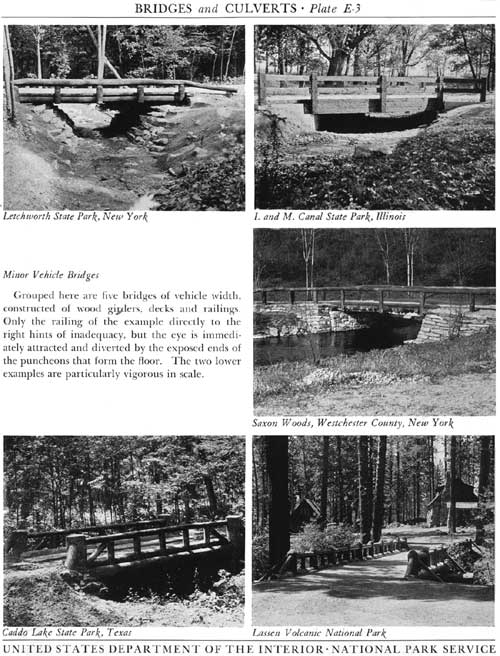

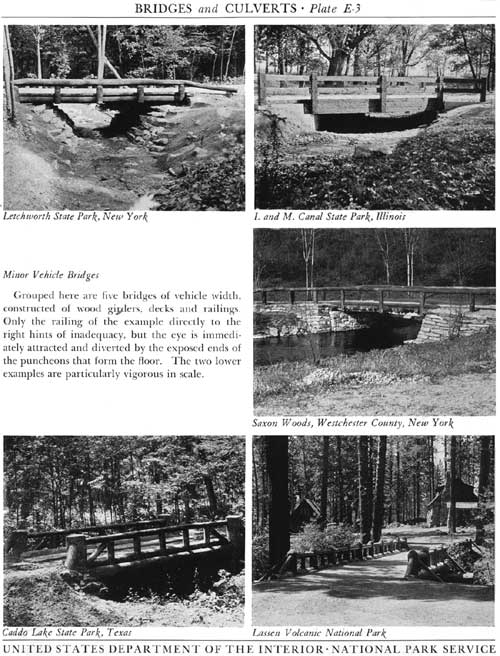

Minor Vehicle Bridges

Grouped here are five bridges of vehicle width,

constructed of wood girders, decks and railings. Only the railing of the

example directly to the right hints of inadequacy, but the eye is

immediately attracted and diverted by the exposed ends of the puncheons that

form the floor. The two lower examples are particularly vigorous in

scale.

|

|

Plate E-3 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Letchworth State Park, New York

|

|

|

I. and M. Canal State Park, Illinois

|

|

|

Saxon Woods, Westchester County, New York

|

|

|

Caddo Lake State Park, Texas

|

|

|

Lassen National Park

|

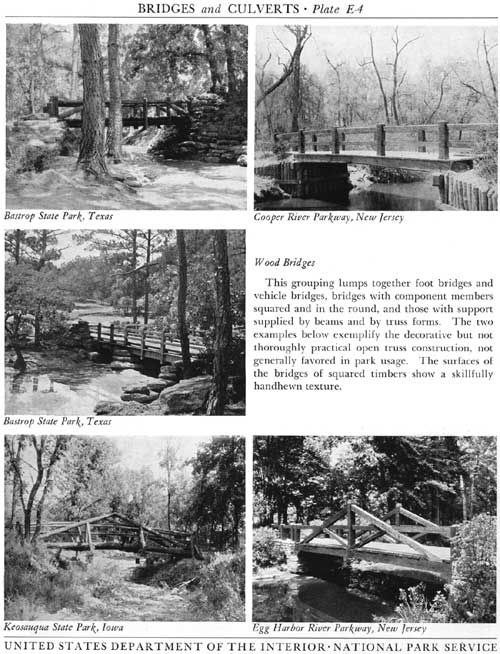

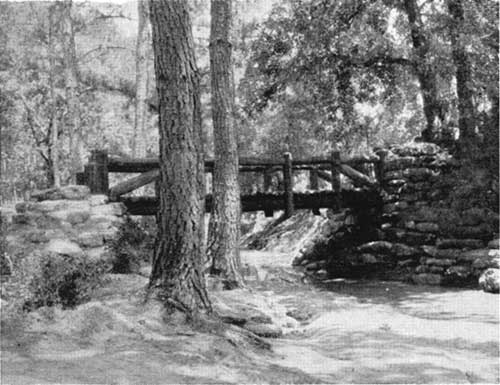

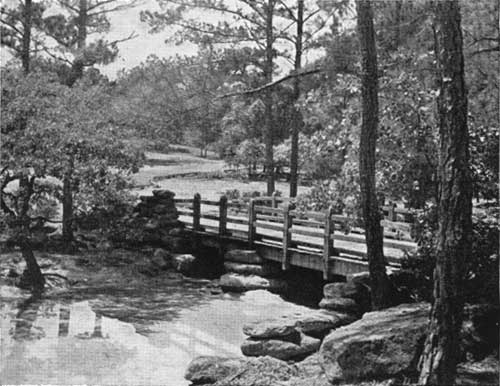

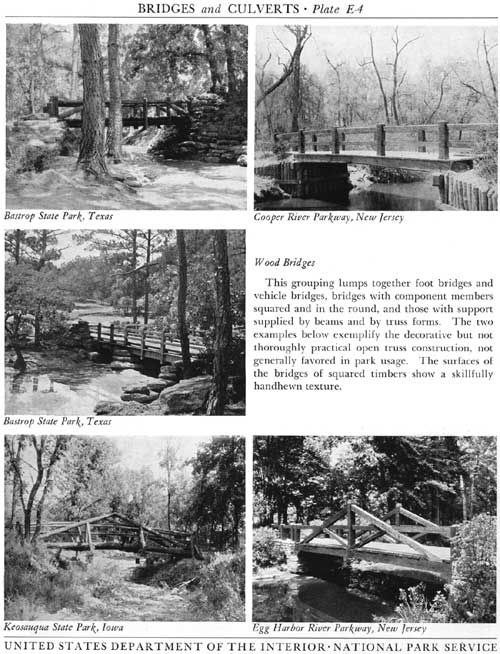

Wood Bridges

This grouping lumps together foot bridges and vehicle

bridges, bridges with component members squared and in the round, and

those with support supplied by beams and by truss forms. The two

examples below exemplify the decorative but not thoroughly practical

open truss construction, not generally favored in park usage. The

surfaces of the bridges of squared timbers show a skillfully handhewn

texture.

|

|

Plate E-4 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Bastrop State Park, Texas

|

|

|

Cooper River Parkway, New Jersey

|

|

|

Bastrop State Park, Texas

|

|

|

Keosauqua State Park, Iowa

|

|

|

Egg Harbor River Parkway, New Jersey

|

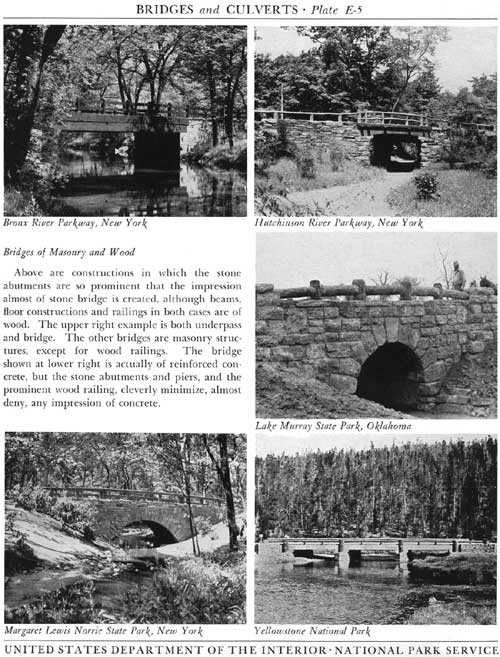

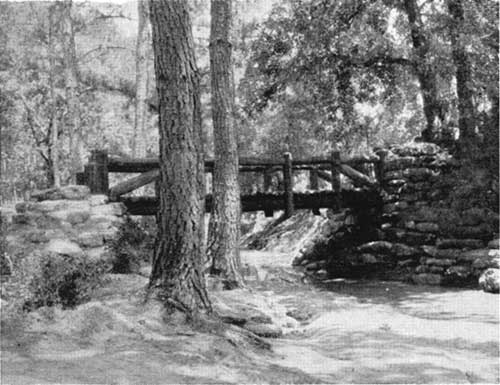

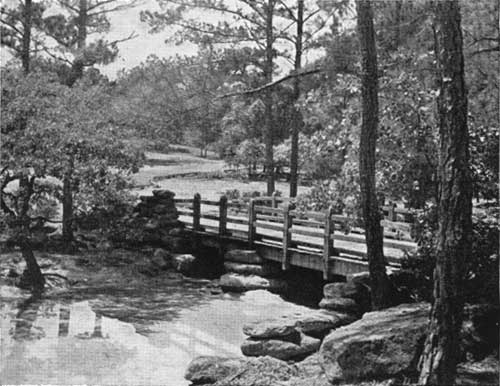

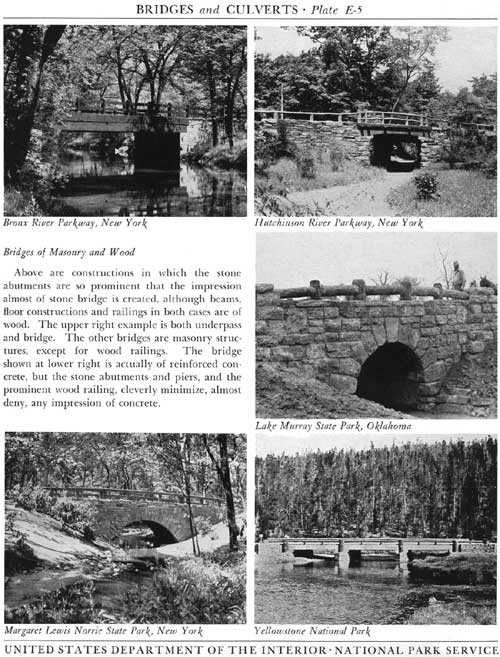

Bridges of Masonry and Wood

Above are constructions in which the stone abutments

are so prominent that the impression almost of stone bridge is created,

although beams, floor constructions and railings in both cases are of

wood. The upper right example is both underpass and bridge. The other

bridges are masonry structures, except for wood railings. The bridge

shown at lower right is actually of reinforced concrete, but the stone

abutments and piers, and the prominent wood railing, cleverly minimize,

almost deny, any impression of concrete.

|

|

Plate E-5 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Bronx River Parkway, New York

|

|

|

Hutchinson River Parkway, New York

|

|

|

Lake Murray State Park, Oklahoma

|

|

|

Margaret Lewis Norrie State Park, New York

|

|

|

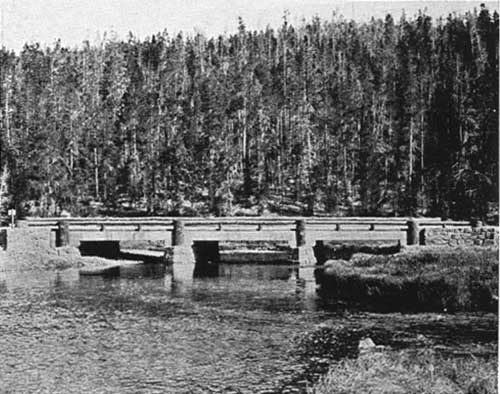

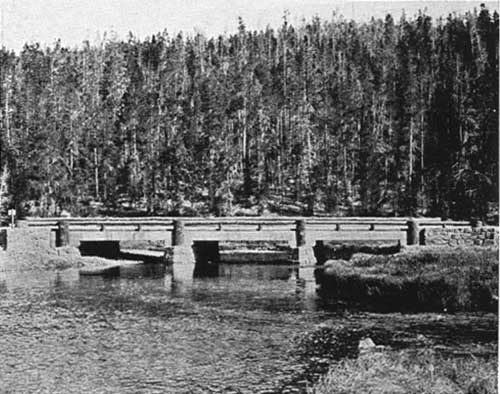

Yellowstone National Park

|

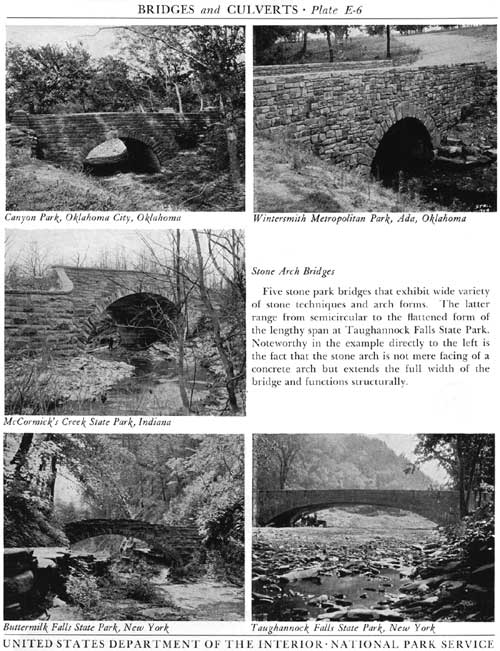

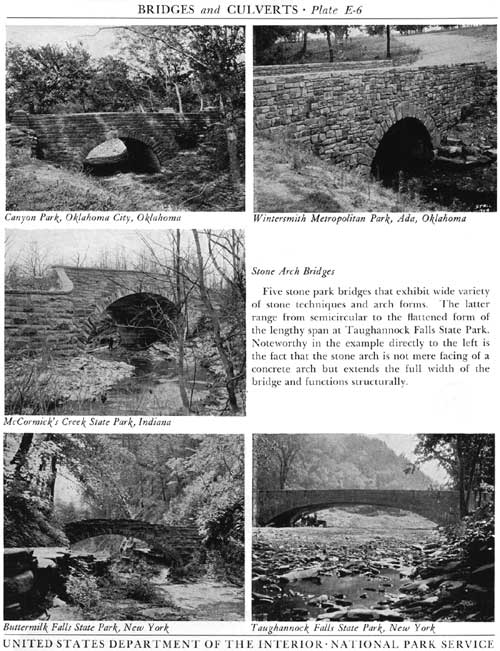

Stone Arch Bridges

Five stone park bridges that exhibit wide variety of

stone techniques and arch forms. The latter range from semicircular to

the flattened form of the lengthy span at Taughannock Falls State Park.

Noteworthy in the example directly to the left is the fact that the

stone arch is not mere facing of a concrete arch but extends the full

width of the bridge and functions structurally.

|

|

Plate E-6 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Canyon Park, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

|

|

|

Wintersmith Metropolitan Park, Ada, Oklahoma

|

|

|

McCormick's Creek State Park, Indiana

|

|

|

Buttermilk Falls State Park, New York

|

|

|

New Taughannock Falls State Park, New York

|

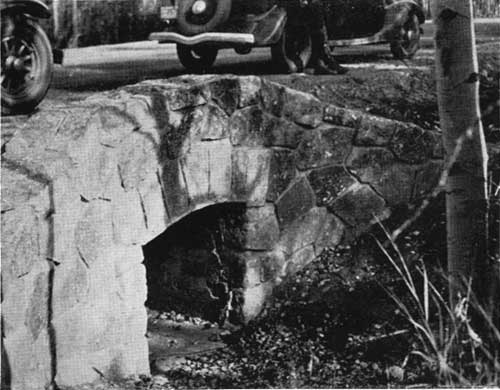

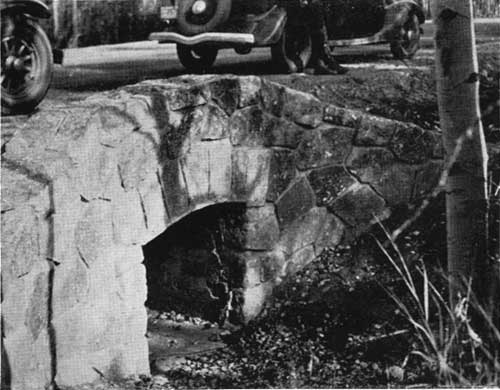

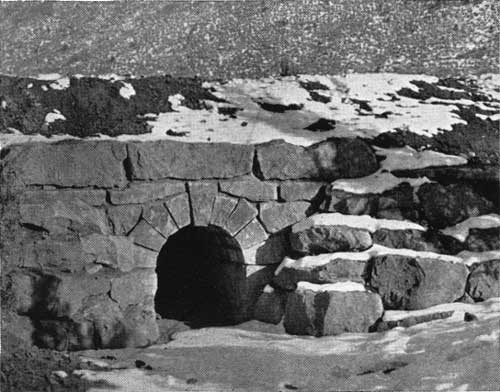

Culvert Treatments

The surrounding illustrations picture culvert

treatments in wide variety, from the most casual naturalistic treatments

of the examples above to the more formal facings of the lower row.

Particularly well blended to its site is the example at lower left.

Within the range of the culverts shown on this and the following page

should be found one to suit almost every possible topographical

condition, as well as the inherent limitations of any kind of native

rock.

|

|

Plate E-7 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Loveland Mountain Metropolitan Park, Colorado

|

|

|

Bronx River Parkway, New York

|

|

|

Rocky Mountain National Park

|

|

|

Hillcrest Park, Durango, Colorado

|

|

|

Pere Marquette State Park, Illinois

|

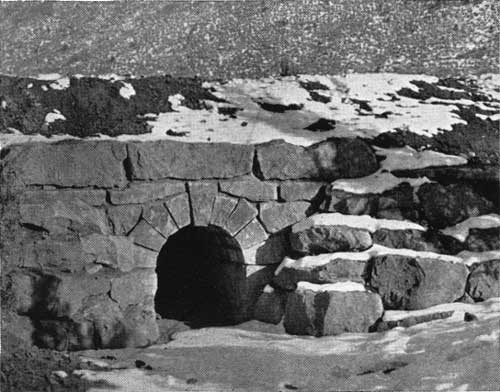

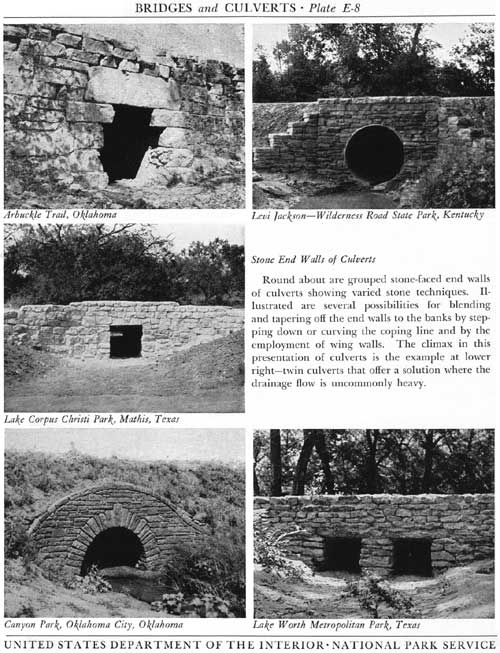

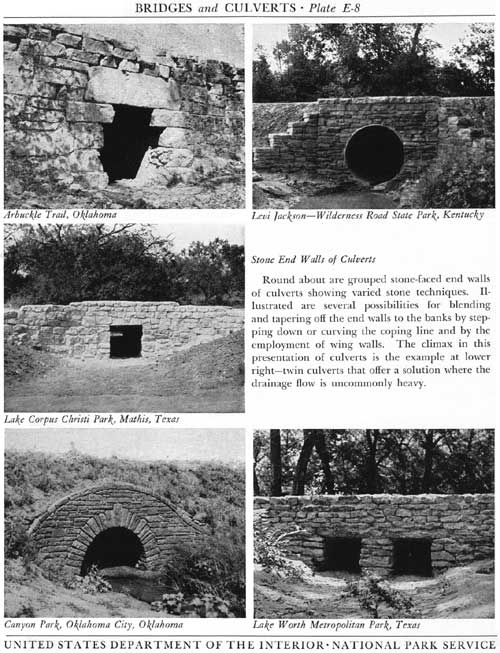

Stone End Walls of Culverts

Round about are grouped stone-faced end walls of

culverts showing varied stone techniques. Illustrated are several

possibilities for blending and tapering off the end walls to the banks

by stepping down or curving the coping line and by the employment of

wing walls. The climax in this presentation of culverts is the example

at lower right—twin culverts that offer a solution where the

drainage flow is uncommonly heavy.

|

|

Plate E-8 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Arbuckle Trail, Oklahoma

|

|

|

Levi Jackson—Wilderness Road State Park, Kentucky

|

|

|

Lakr Corphus Christi Park, Mathis, Texas

|

|

|

Canyon Park, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

|

|

|

Lake Worth Metropolitan Park, Texas

|

park_structures_facilities/sece.htm

Last Updated: 5-Dec-2011

|