NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Park Structures and Facilities

|

|

SHELTERS and RECREATION BUILDINGS

BEYOND DOUBT the most generally useful building in

any park is a shelter, usually open but sometimes enclosed or

enclosable, and then referred to as a recreation or community building,

or a pavilion.

It is admittedly no trivial task to achieve a

desirable and unforced variety in such buildings within the confines of

a moderate cost. This is true of other park structures, but it is more

apparent of shelters because they are so universally existent in park

areas. It is the almost invariable presence of at least one shelter, and

often of several shelters, in every park that tends to make us

especially and painfully aware of a spiritless monotony of design and

execution. Exertion of effort to bring character to a shelter, such as

will differentiate it from a thousand and one others, is all too rare;

attainment of the objective, without bizarre result, still more rare.

The attempt is worth all the creative effort expended; the successful

accomplishment, truly worthy of praise.

Because its purpose and use usually lead to its

placement in the choicest of locations within the park, where it is

natural to invite the park user to rest and contemplate a particularly

beautiful prospect or setting, the shelter finds itself in the very

center of a stage with a back-drop by the first Old Master. Its role is

thus a difficult one, and is ill-played if rendered in the flippant

slang or thin syncopated measures of the moment. Slapstick comedy

technique is inappropriate; some dignity beyond passing fad or fashion

is demanded of the shelter's stellar part.

The essentials of a shelter include first of all

overhead protection and a place to sit and rest. In size, shelters range

from the very small and minor, in a simple rendering, to the large and

complicated, when many extra-functional dependencies are included in the

ambitious structures of a large, much-used park.

Transition from the simplest to the specialized or

more complex structure may be effected by the incorporation of one or

more fireplaces, the partial or complete enclosing of the sides for

protection from wind or weather, the provision of ovens or grills for

picnic cooking and tables and seats for the picnic meal. The shelter of

special purpose or the recreation building for year-round use

results.

There are colloquial departures in shelters and their

functions that make for some well-defined varieties.

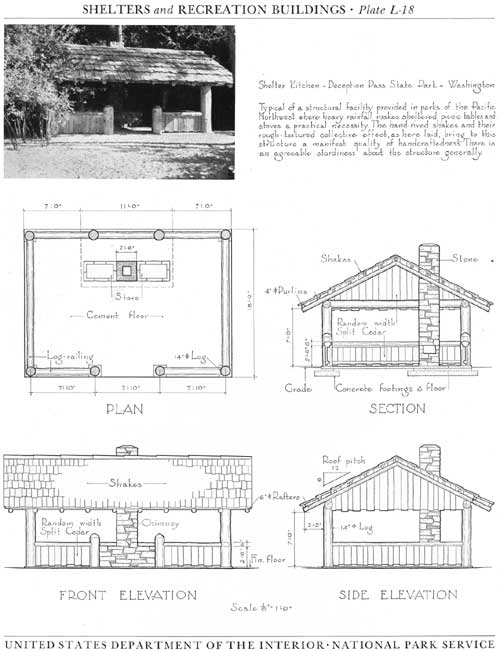

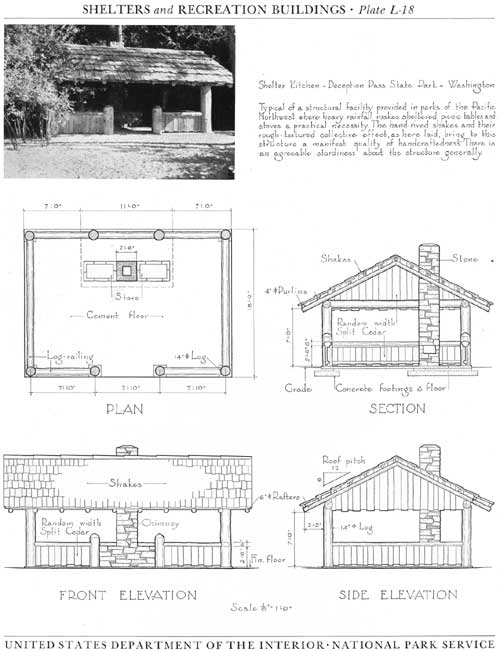

One such is the so-called kitchen shelter developed

in the Northwest, where presumably heavy rainfall is an abnormal threat

to cooking picnic fare in the open. The type evolved is a kind of

combined kitchen and picnic shelter, the sides widely open except

against the prevailing winds. Our countrymen of this region must fairly

radiate sweetness and light, for here almost invariably the facilities

for cooking are double, triple or quadruple ovens ranged in close

proximity about one chimney. The shelters bear no noticeable scars of

intergroup ruction and seem almost to refute the widely held conviction

that close contact of picnicking groups is provocative of trouble.

Perhaps from this peaceable region will spread forth the millennium when

the lion and the lamb universally can picnic on the same half-acre and

like it.

Typical of the Southwest is the ramada,

functioning in protection of the picnicker from the heat and brilliance

of the desert sun. Its name is from the Spanish, its style generally

derived from the Pueblo. It is built with rock or adobe walls or piers,

its practically flat roof carried on round poles, or vigas. The

roofs are usually covered with a kind of thatch allowed to hang down

over the edges as a fringed protective valance of bewhiskered

appearance. The ramada of the desert country is often equipped

with an integral open fireplace and chimney. Sometimes there is

provided instead an outdoor fireplace nearby for the preparation of

food. The ramada often accommodates more than one picnic

group.

There are logical combinations of the shelter with

other park structural needs which bring welcome diversification to its

form and appearance. Custodian's or concessionaire's quarters,

concession space, public comfort stations, storage space, and other

facilities have been successfully incorporated with shelters and

produced satisfying variations which avoid implication either of the

commonplace on the one hand or the fantastic on the other. There are

sufficient legitimate combinations and cross combinations of functions,

materials, forms, and other ingredients to make possible an almost

infinite number of agreeably different shelters, if served up without

economy of skill and effort in the contriving, and seasoned with a

palatable dash of individuality.

The shelter floor may be simply a gravel or earth

fill, or may be brick or stone laid on a sand fill. A wood floor for a

shelter has little to recommend it. Concrete pavement with one of

several surface materials may be used. The variety of soil and frost

conditions over the entire country precludes the making of a

recommendation in the choice of material. Available funds likewise will

affect its selection. Whatever material a thorough consideration of

circumstances may designate for use, it is rather to be urged that it be

intelligently employed with due thought for its fitness and durability.

So many pavements of open shelters have failed to survive the local

temperature range and frost action with such disheartening results, that

it is not unfair to assert that there has been too prevalent

ignorance or naive disregard of unchangeable material facts. Were it not

for the introductory promise to avoid the "primer" approach within these

discussions, there would be at this point a yielding to temptation to

point out that masonry expands under heat and contracts with cold, and

that proper expansion joints are a specific, that foundation walls are

unreliable unless carried below the local frost level, and that bounding

retaining walls do not long retain if moisture can collect underground

above the frost line. A promise being what it is, a recall of these

elementary facts must go herein unrecorded and neglected.

|

|

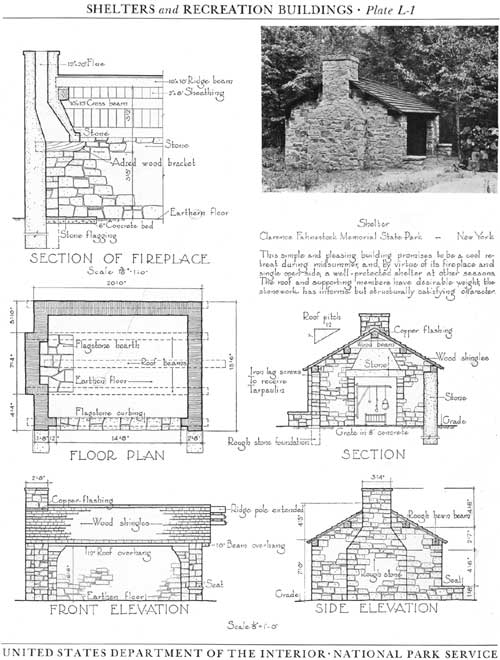

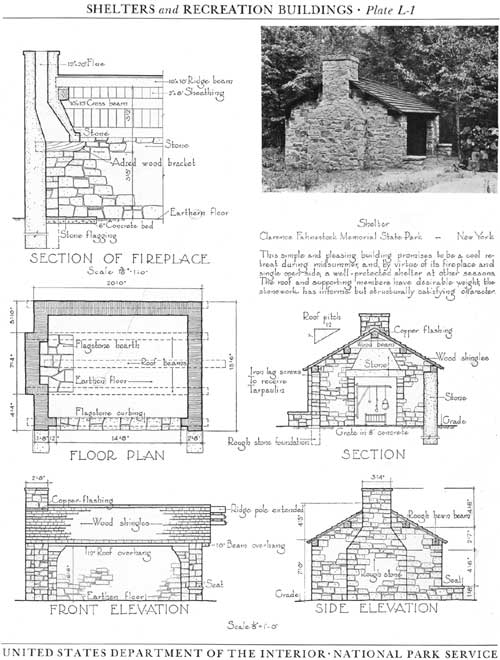

Plate L-1 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

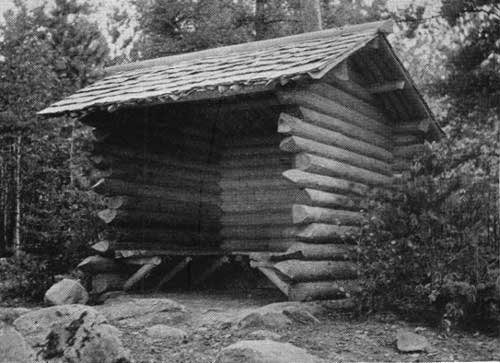

Plate L-2 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

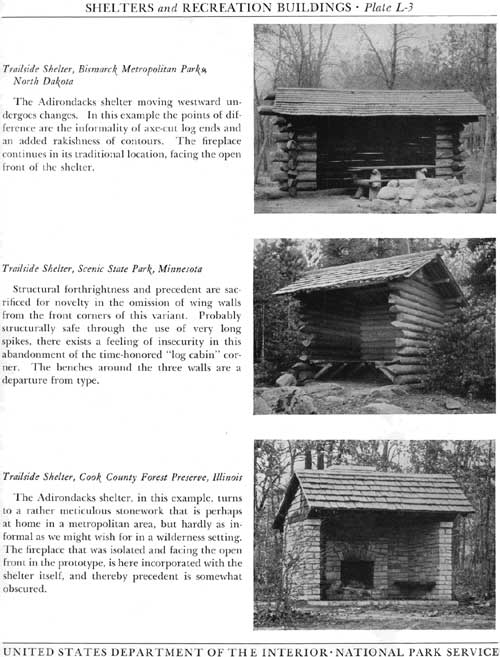

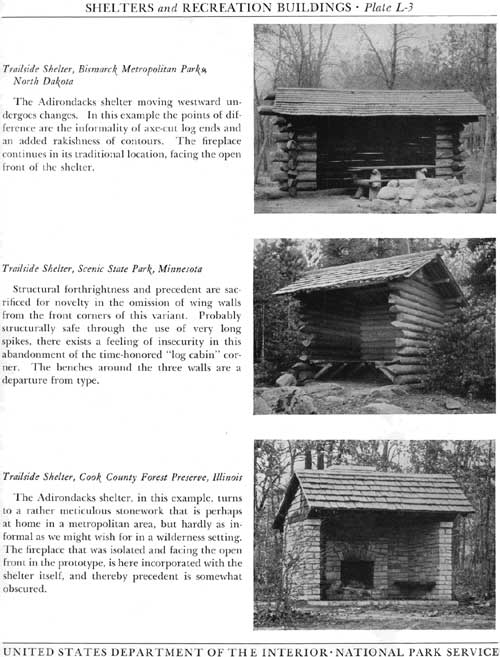

Plate L-3 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

Trailside Shelter, Bismarck Metropolitan Parks, North Dakota

The Adirondacks shelter moving westward undergoes

changes. In this example the points of difference are the informality of

axe-cut log ends and an added rakishness of contours. The fireplace

continues in its traditional location, facing the open front of the

shelter.

|

|

Bismarck Metropolitan Parks, North Dakota

|

Trailside Shelter, Scenic State Park, Minnesota

Structural forthrightness and precedent are

sacrificed for novelty in the omission of wing walls from the front

corners of this variant. Probably structurally safe through the use of

very long spikes, there exists a feeling of insecurity in this

abandonment of the time-honored "log cabin" corner. The benches around

the three walls are a departure from type.

|

|

Scenic State Park, Minnesota

|

Trailside Shelter, Cook County Forest Preserve, Illinois

The Adirondacks shelter, in this example, turns to a

rather meticulous stonework that is perhaps at home in a metropolitan

area, but hardly as informal as we might wish for in a wilderness

setting. The fireplace that was isolated and facing the open front in

the prototype, is here incorporated with the shelter itself, and thereby

precedent is somewhat obscured.

|

|

Cook County Forest Preserve, Illinois

|

|

|

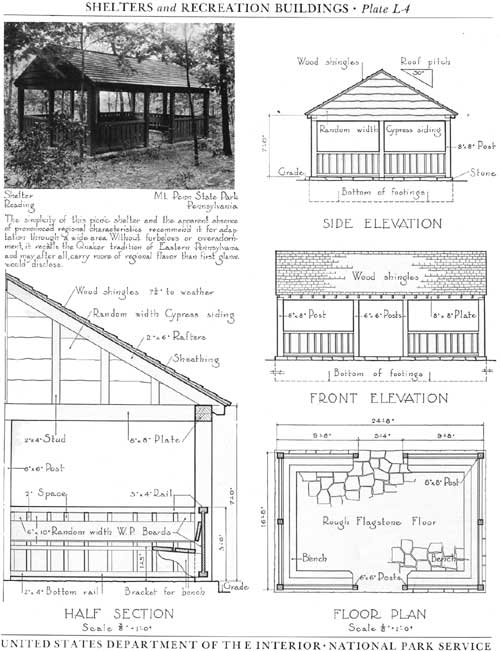

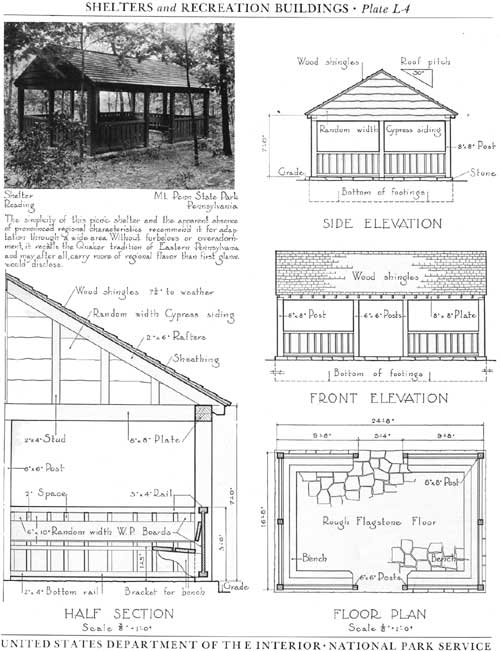

Plate L-4 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

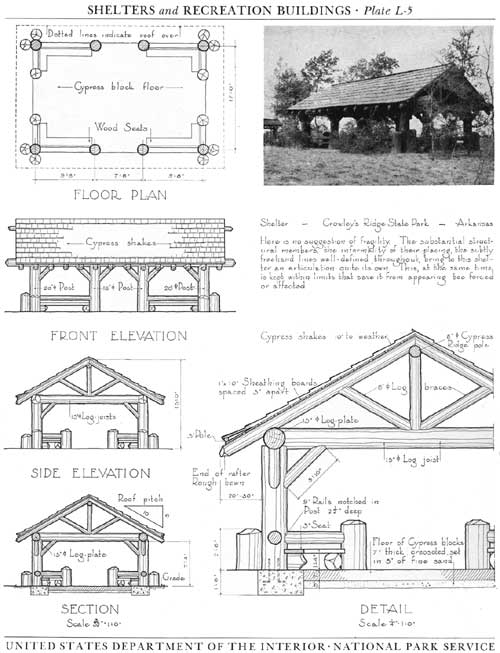

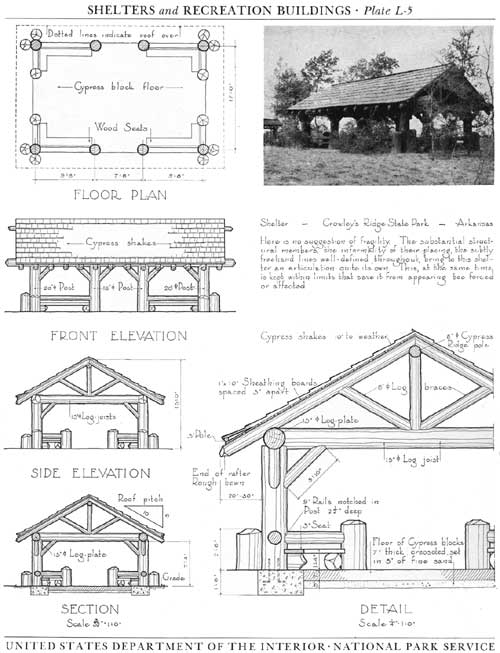

Plate L-5 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

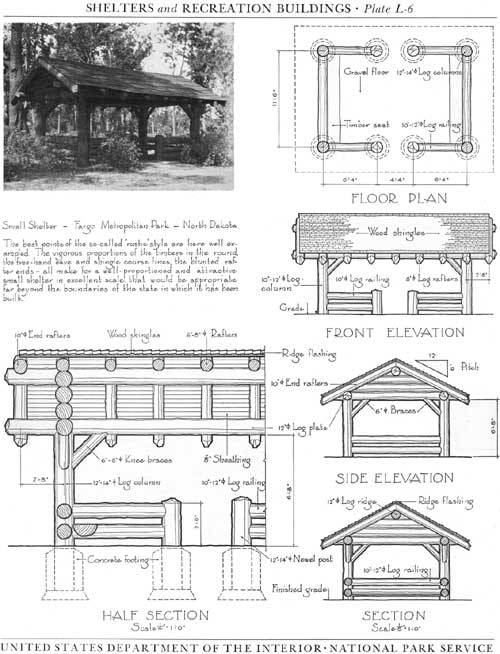

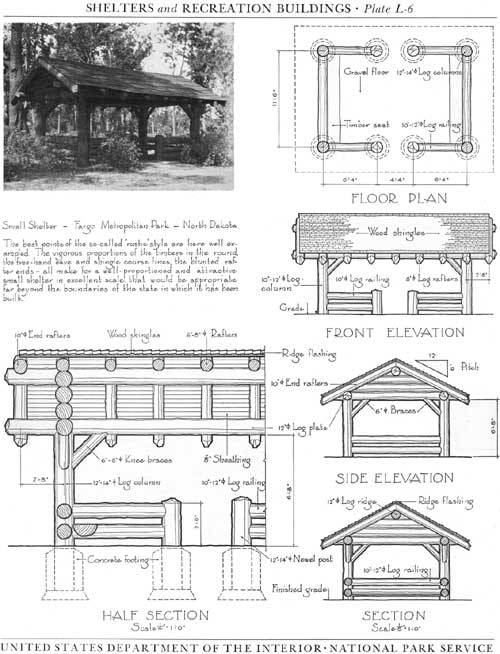

Plate L-6 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

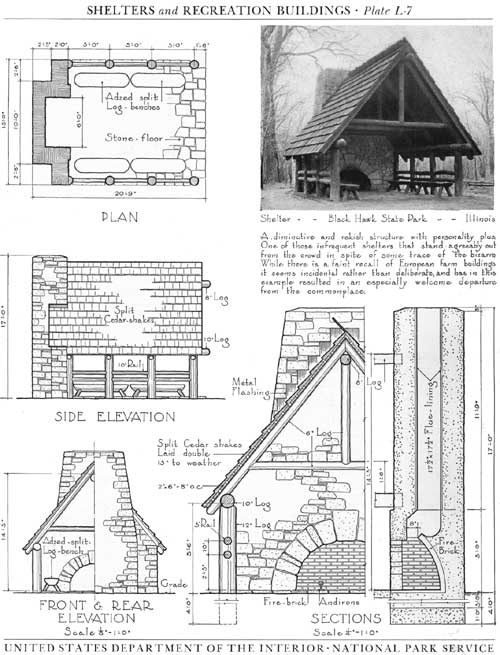

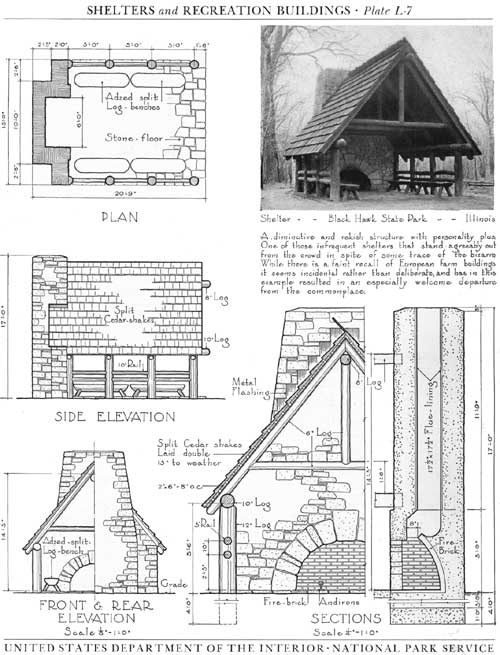

Plate L-7 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

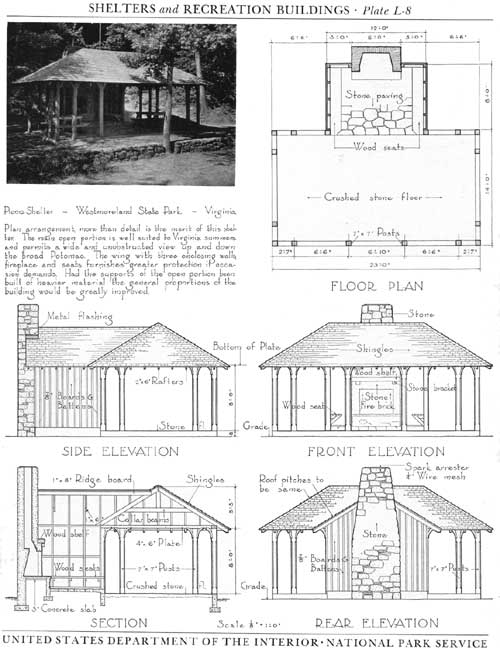

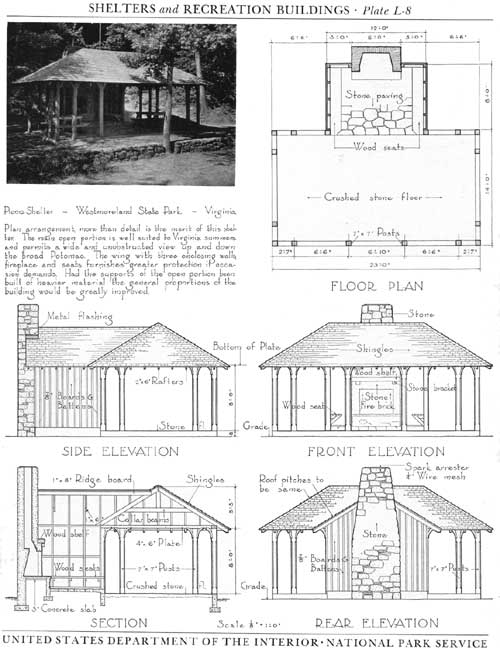

Plate L-8 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

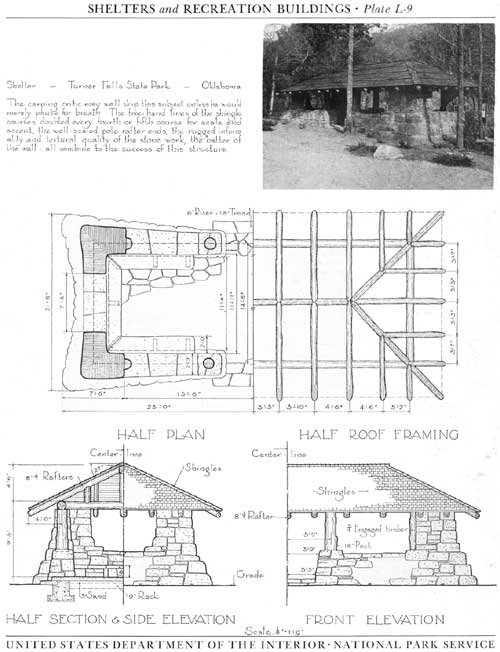

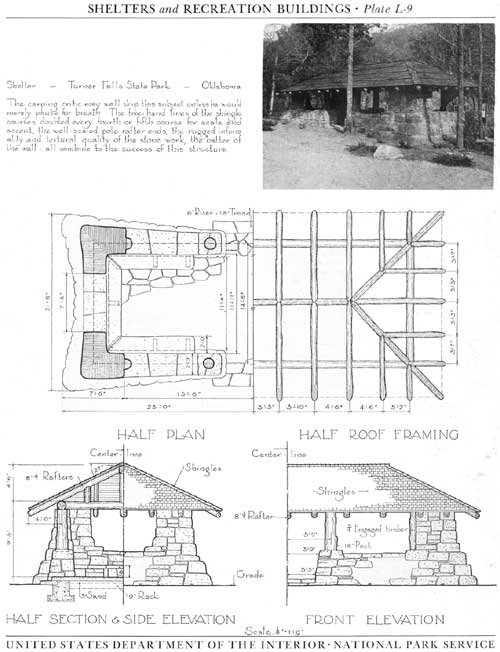

Plate L-9 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

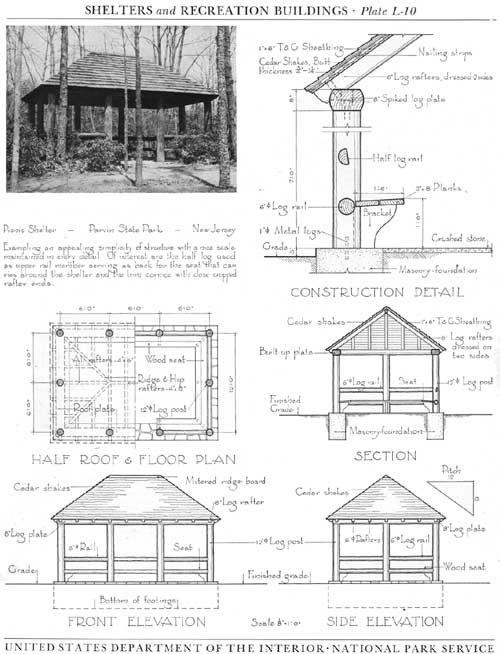

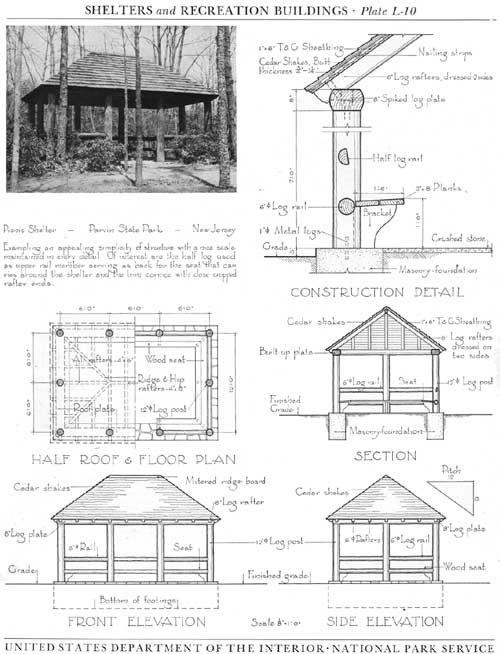

Plate L-10 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

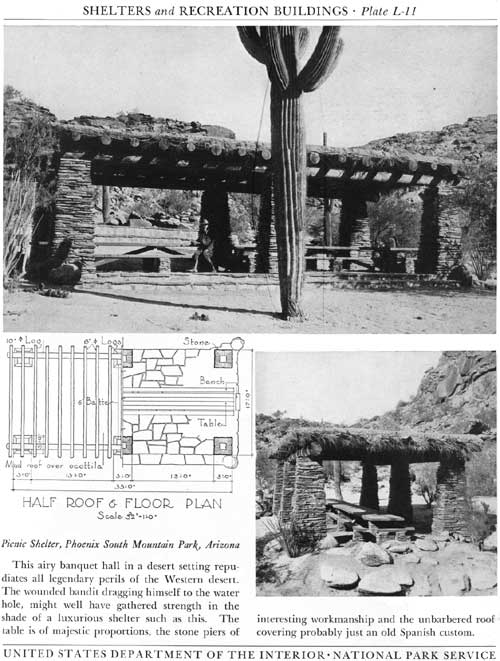

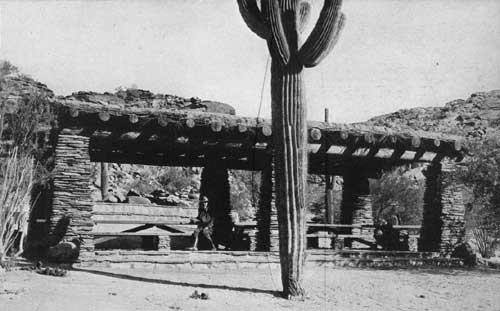

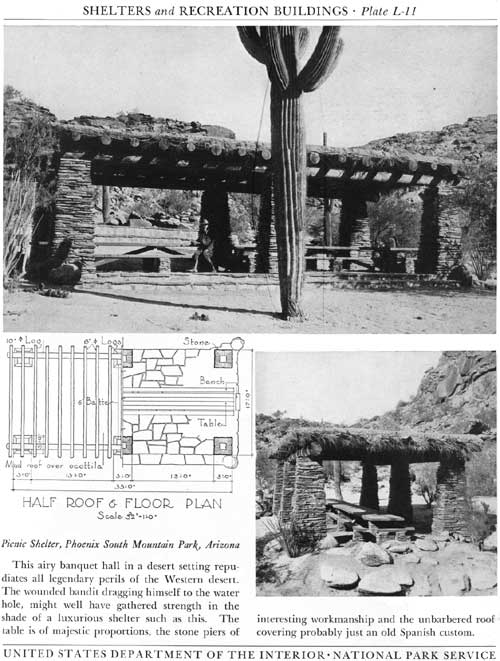

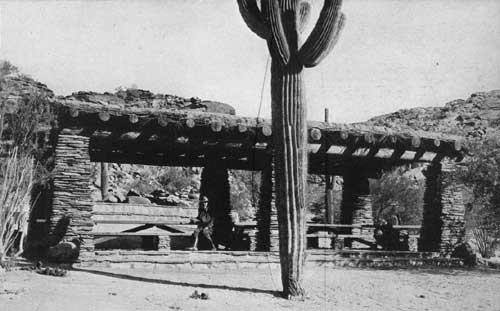

Picnic Shelter, Phoenix South Mountain Park, Arizona

This airy banquet hail in a desert setting repudiates

all legendary perils of the Western desert. The wounded bandit dragging

himself to the water hole, might well have gathered strength in the

shade of a luxurious shelter such as this. The table is of majestic

proportions, the stone piers of interesting workmanship and the

unbarbered roof covering probably just an old Spanish custom.

|

|

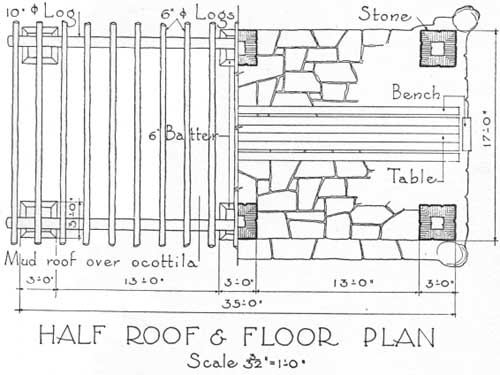

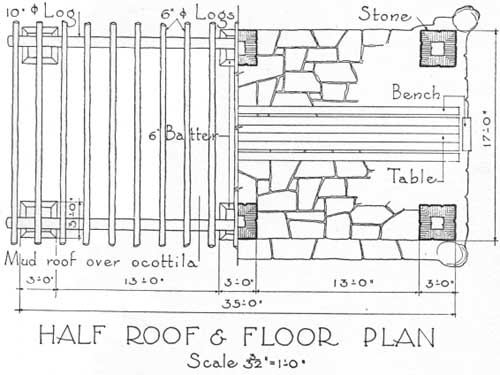

Plate L-11 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Phoenix South Mountain Park, Arizona

|

|

|

Phoenix South Mountain Park, Arizona

|

|

|

Phoenix South Mountain Park, Arizona

|

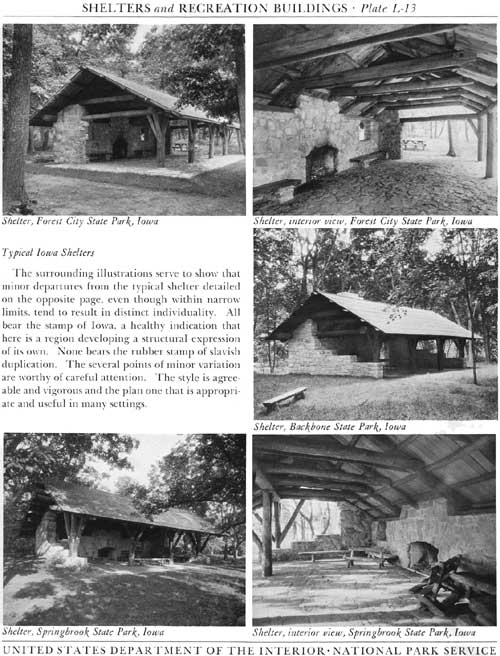

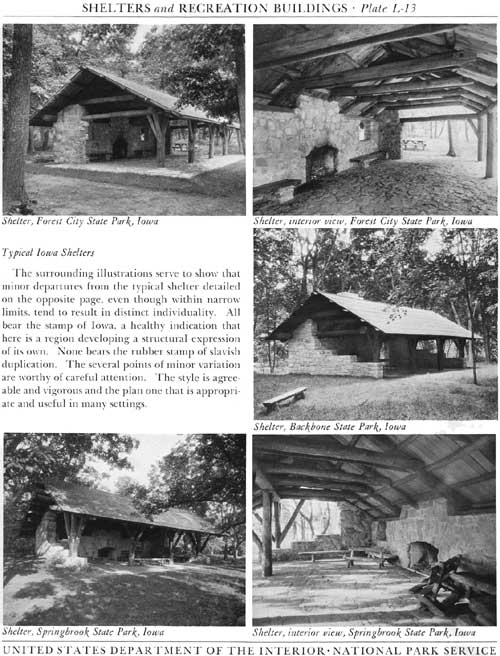

Typical Iowa Shelters

The surrounding illustrations serve to show that

minor departures from the typical shelter detailed on the opposite page,

even though within narrow limits, tend to result in distinct

individuality. All bear the stamp of Iowa, a healthy indication that

here is a region developing a structural expression of its own. None

bears the rubber stamp of slavish duplication. The several points of

minor variation are worthy of careful attention. The style is agreeable

and vigorous and the plan one that is appropriate and useful in many

settings.

|

|

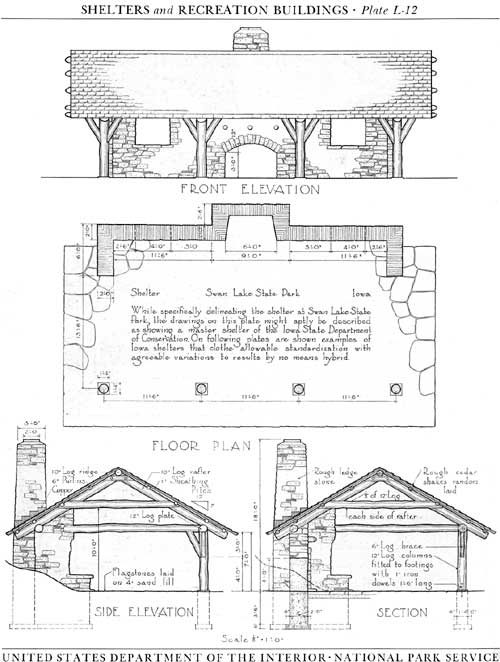

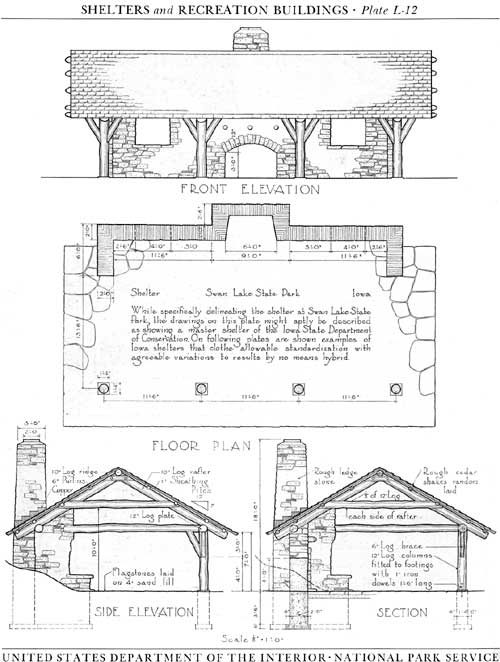

Plate L-12 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Plate L-13 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Shelter, Forest City State Park, Iowa

|

|

|

Shelter, interior view, Forest City State Park, Iowa

|

|

|

Shelter, Backbone State Park, Iowa

|

|

|

Shelter, Springbrook State Park, Iowa

|

|

|

Shelter, interior view, Springbrook State Park, Iowa

|

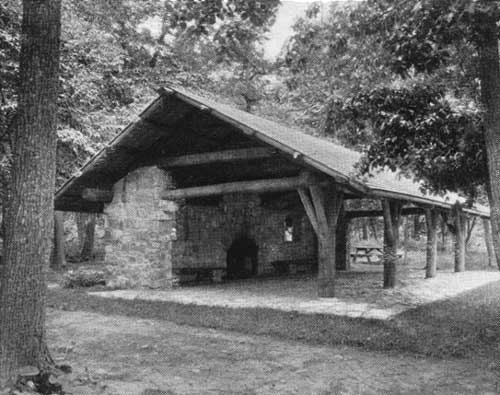

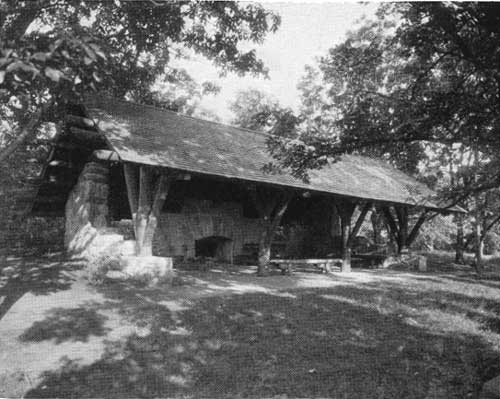

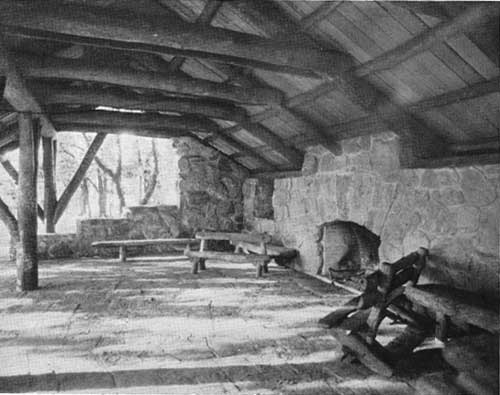

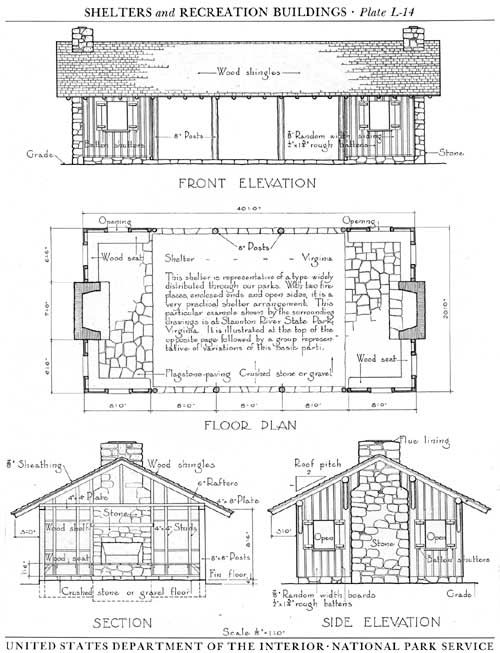

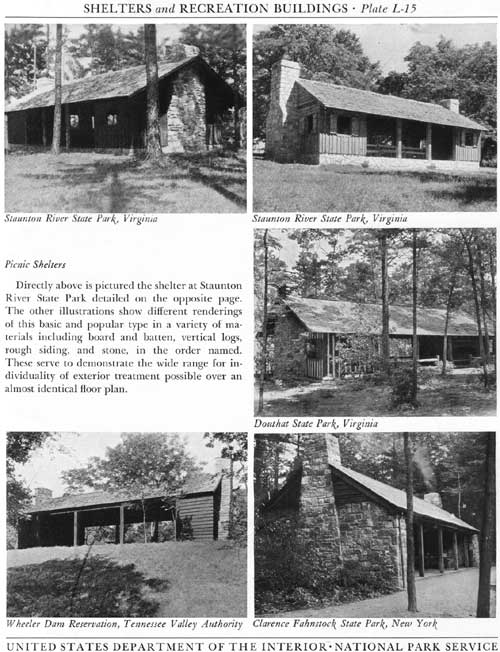

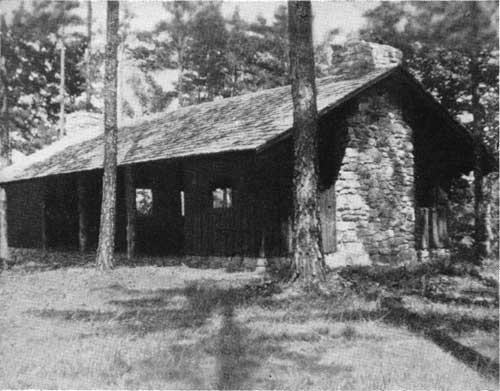

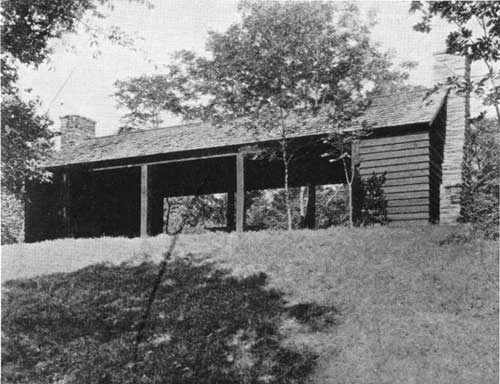

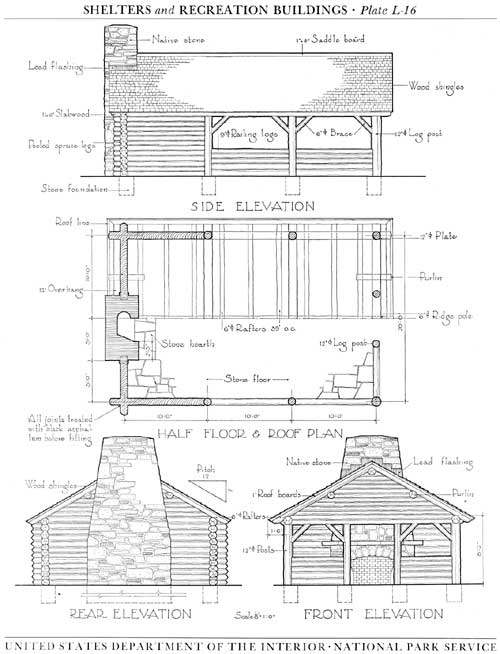

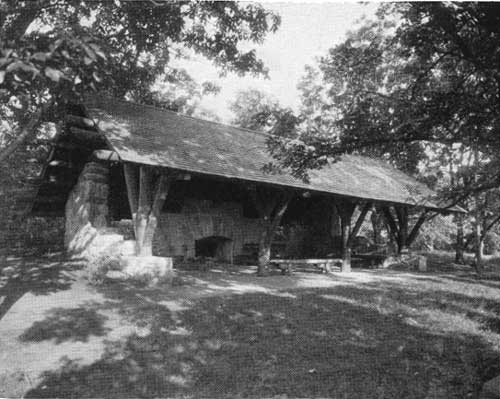

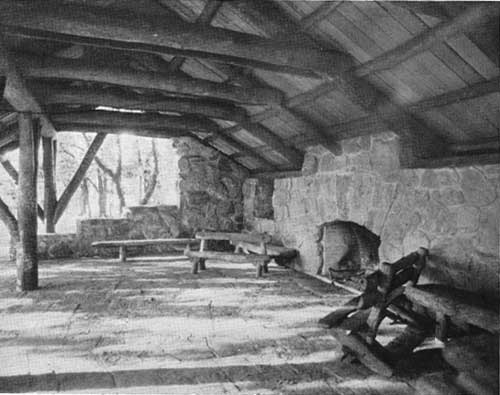

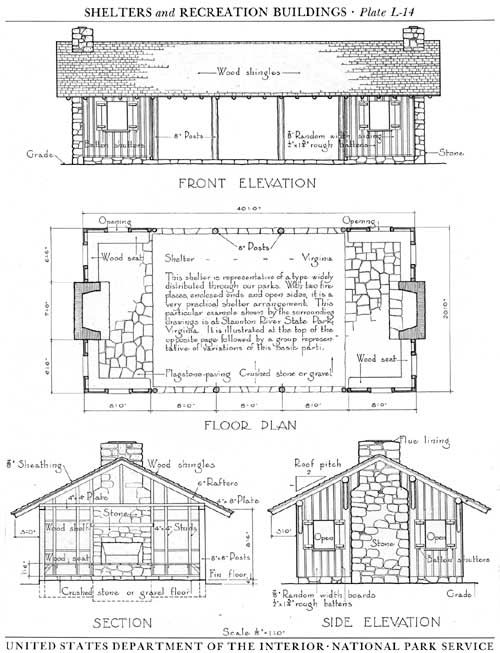

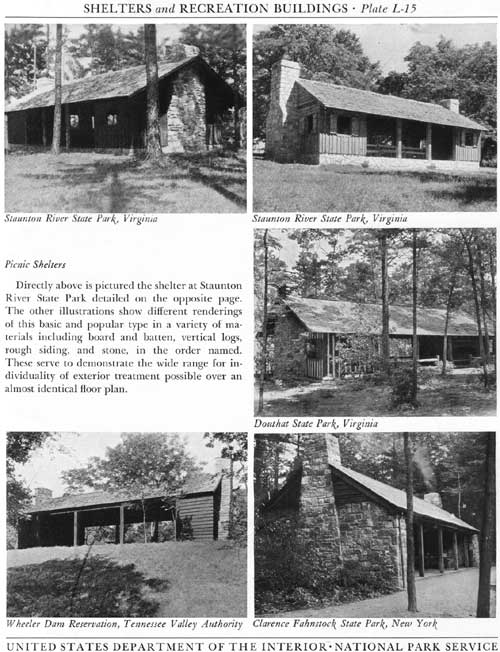

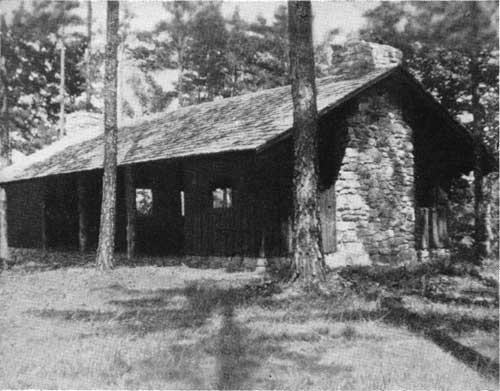

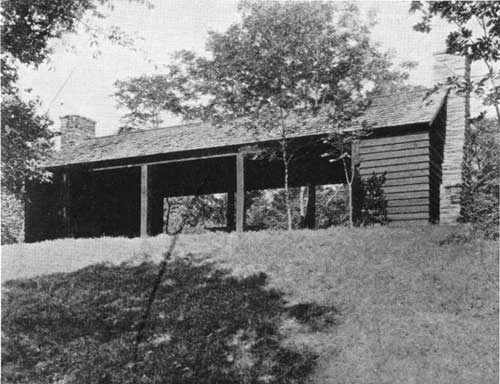

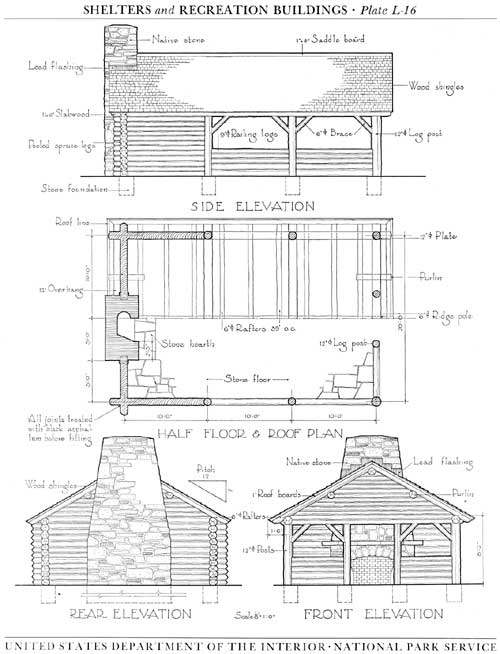

Picnic Shelters

Directly above is pictured the shelter at Staunton

River State Park detailed on the opposite page. The other illustrations

show different renderings of this basic and popular type in a variety of

materials including board and batten, vertical logs, rough siding, and

stone, in the order named. These serve to demonstrate the wide range for

individuality of exterior treatment possible over an almost identical

floor plan.

|

|

Plate L-14 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Plate L-15 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

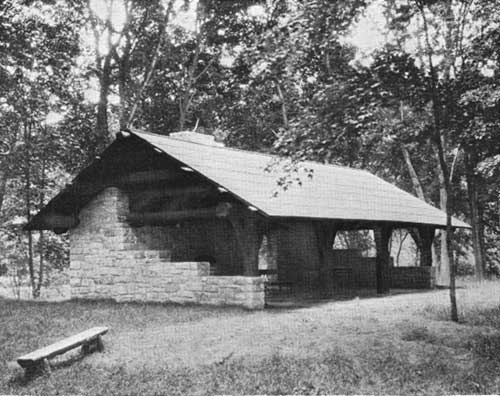

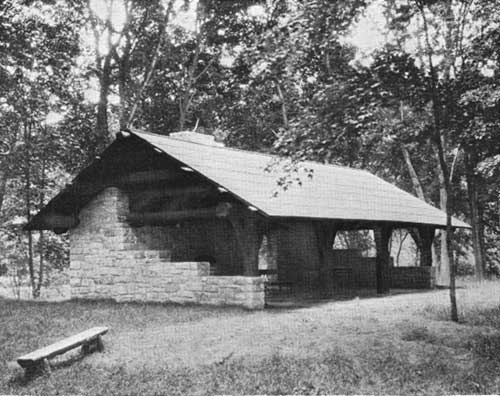

Staunton River State Park, Virginia

|

|

|

Staunton River State Park, Virginia

|

|

|

Douthat State Park, Virginia

|

|

|

Wheeler Dam Reservation, Tennessee Valley Authority

|

|

|

Clarence Fahnstock State Park, New York

|

|

|

Plate L-16 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Plate L-17 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

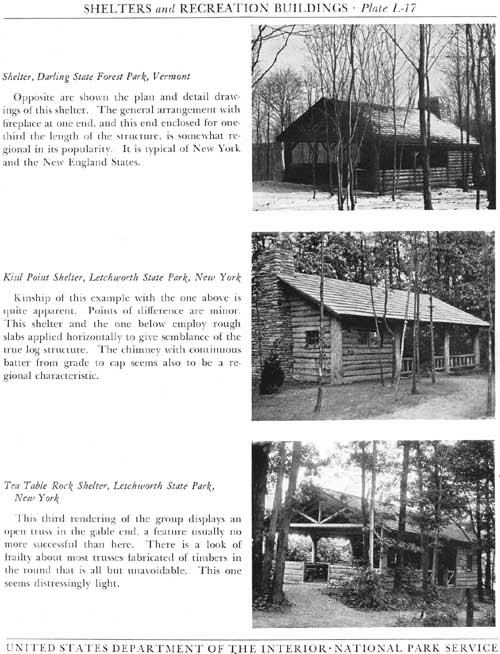

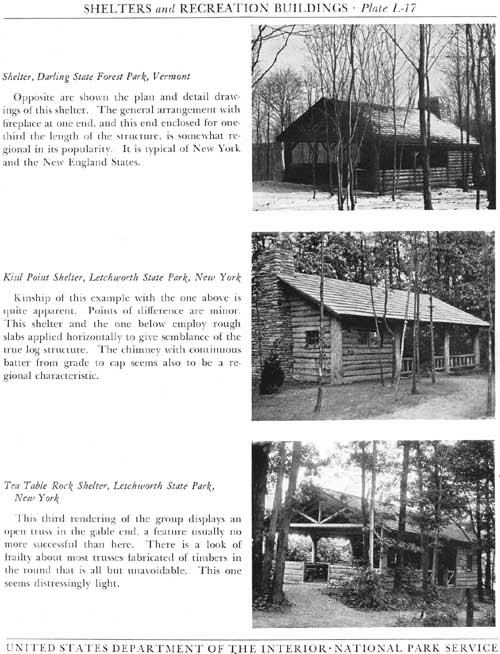

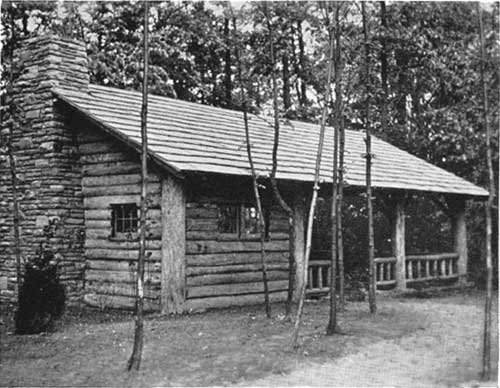

Shelter, Darling State Forest Park, Vermont

Opposite are shown the plan and detail drawings of

this shelter. The general arrangement with fireplace at one end, and

this end enclosed for one-third the length of the structure, is

somewhat regional in its popularity. It is typical of New York and the

New England States.

|

|

Darling State Forest Park, Vermont

|

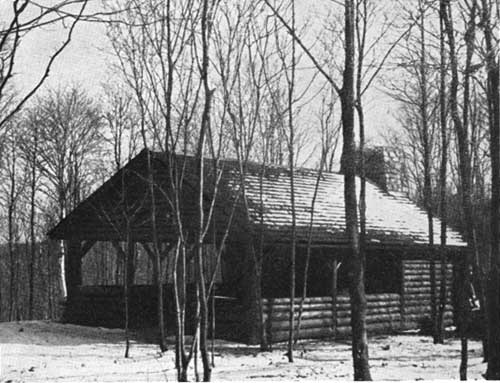

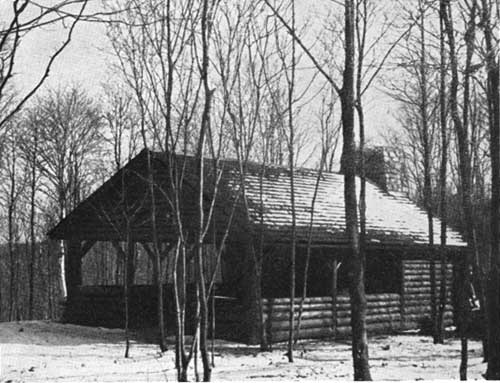

Kisil Point Shelter, Letchworth State Park, New York

Kinship of this example with the one above is quite

apparent. Points of difference are minor. This shelter and the one below

employ rough slabs applied horizontally to give semblance of the true

log structure. The chimney with continuous batter from grade to cap

seems also to be a regional characteristic.

|

|

Kisil Point Shelter, Letchworth State Park, New York

|

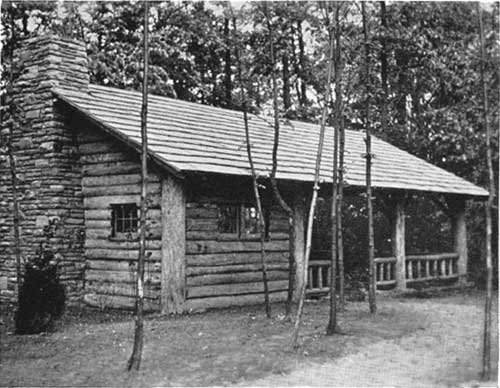

Tea Table Rock Shelter, Letchworth State Park, New York

This third rendering of the group displays an open

truss in the gable end, a feature usually no more successful than here.

There is a look of frailty about most trusses fabricated of timbers in

the round that is all but unavoidable. This one seems distressingly

light.

|

|

Tea Table Rock Shelter, Letchworth State Park, New York

|

|

|

Plate L-18 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

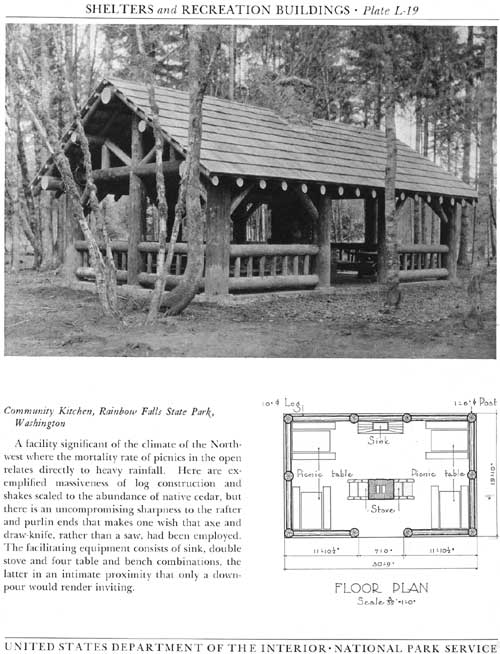

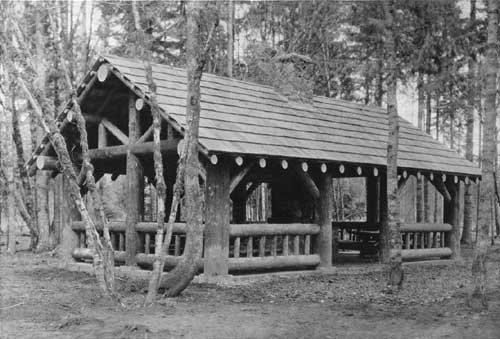

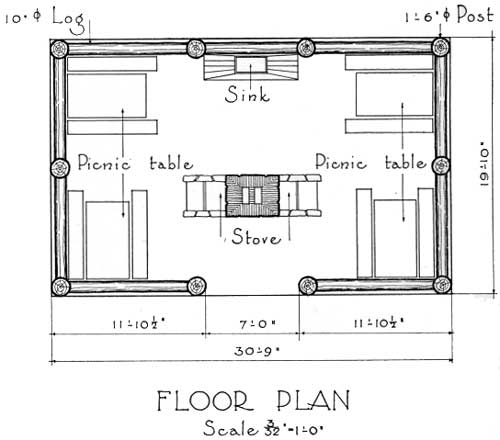

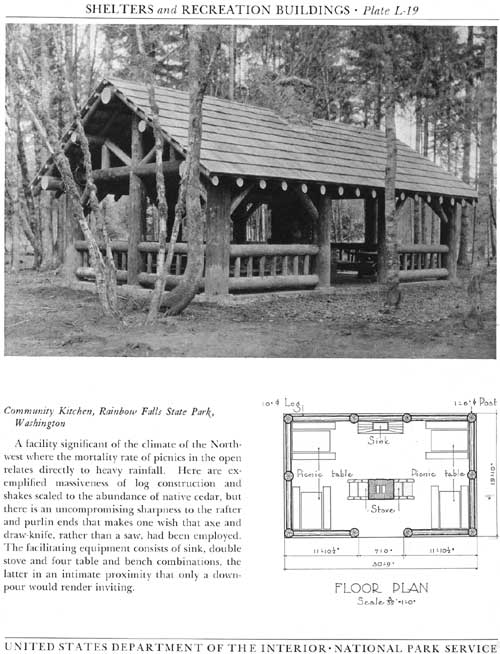

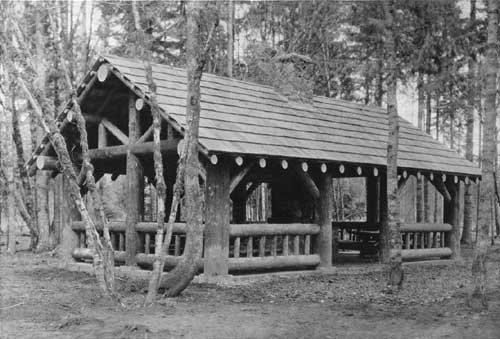

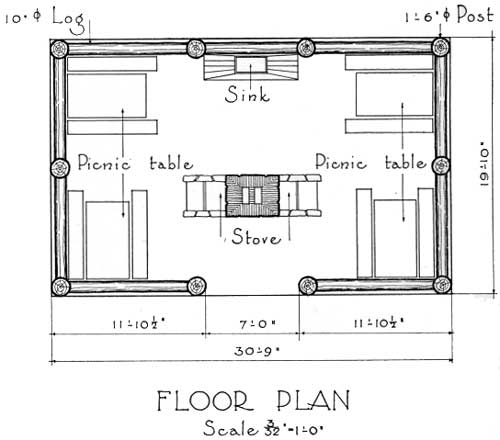

Community Kitchen, Rainbow Falls State Park, Washington

A facility significant of the climate of the

Northwest where the mortality rate of picnics in the open relates directly to

heavy rainfall. Here are exemplified massiveness of log construction and

shakes scaled to the abundance of native cedar, but there is an

uncompromising sharpness to the rafter and purlin ends that makes one

wish that axe and draw-knife, rather than a saw, had been employed. The

facilitating equipment consists of sink, double stove and four table and

bench combinations, the latter in an intimate proximity that only a

downpour would render inviting.

|

|

Plate L-19 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Community Kitchen, Rainbow Falls State Park, Washington

|

|

|

Community Kitchen, Rainbow Falls State Park, Washington

|

|

|

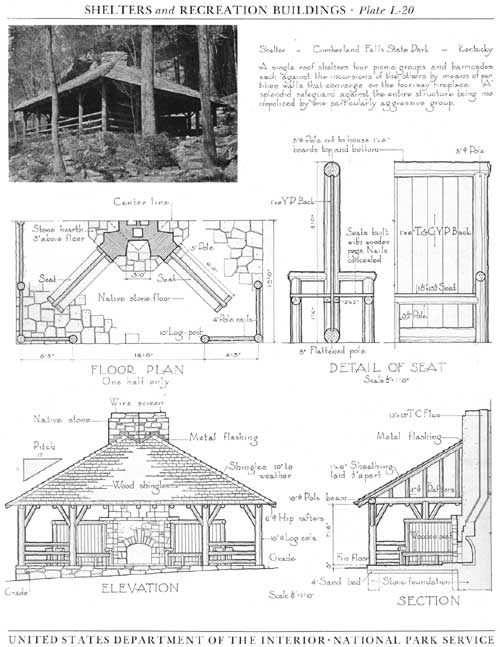

Plate L-20 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

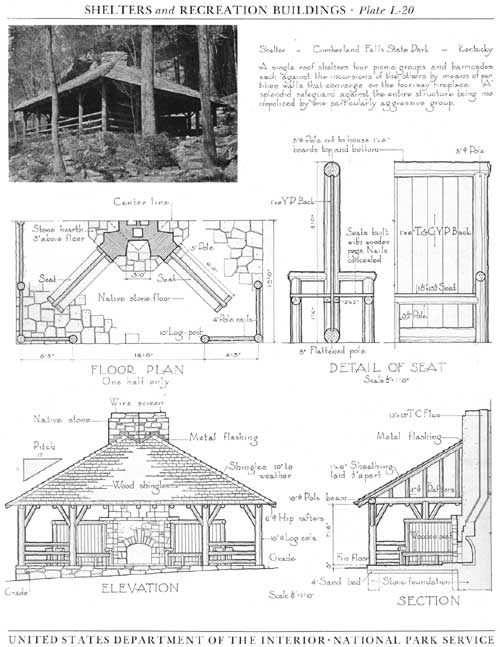

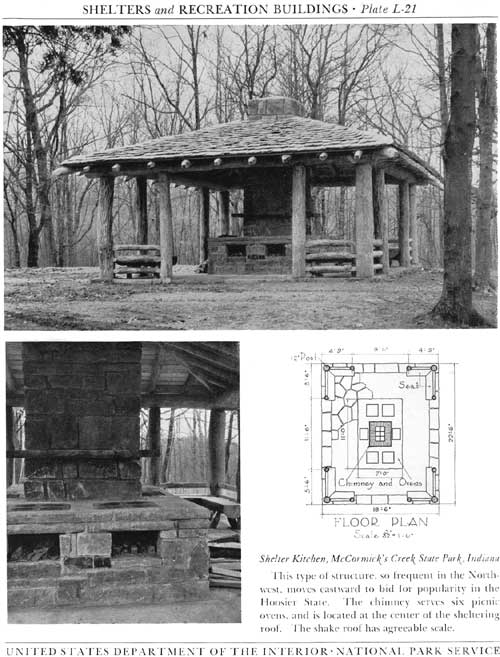

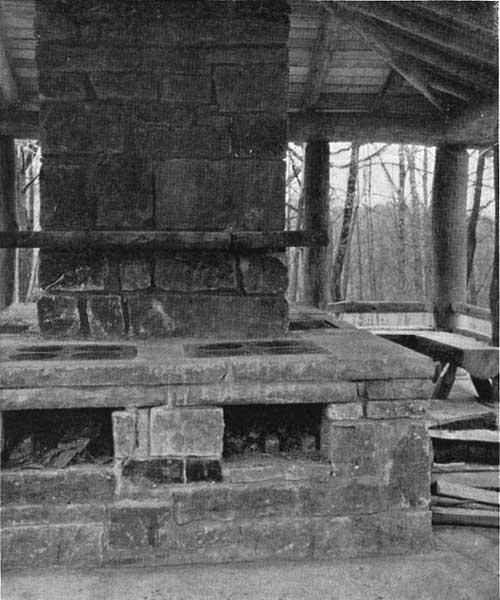

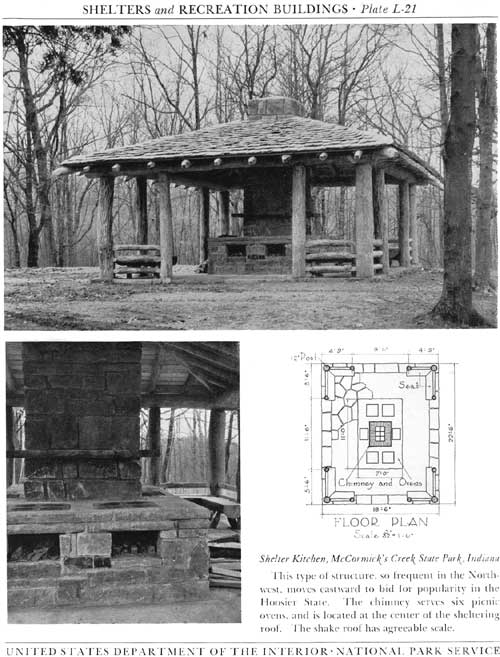

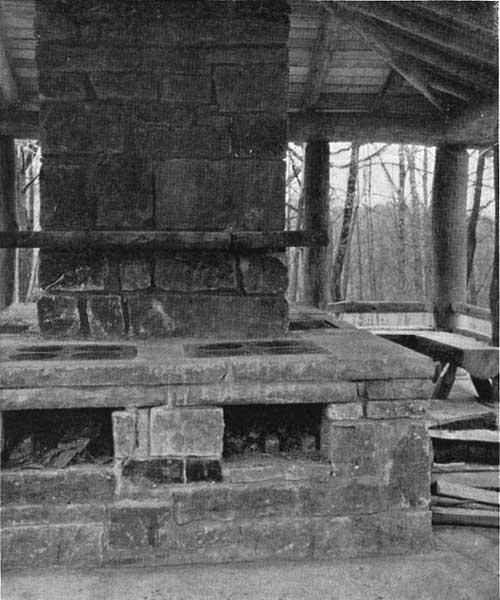

Shelter Kitchen, McCormick's Creek State Park, Indiana

This type of structure, so frequent in the

Northwest, moves eastward to bid for popularity in the Hoosier State. The

chimney serves six picnic ovens, and is located at the center of the

sheltering roof. The shake roof has agreeable scale.

|

|

Plate L-21 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

McCormick's Creek State Park, Indiana

|

|

|

McCormick's Creek State Park, Indiana

|

|

|

McCormick's Creek State Park, Indiana

|

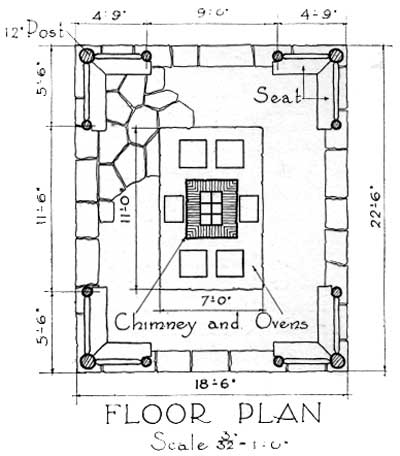

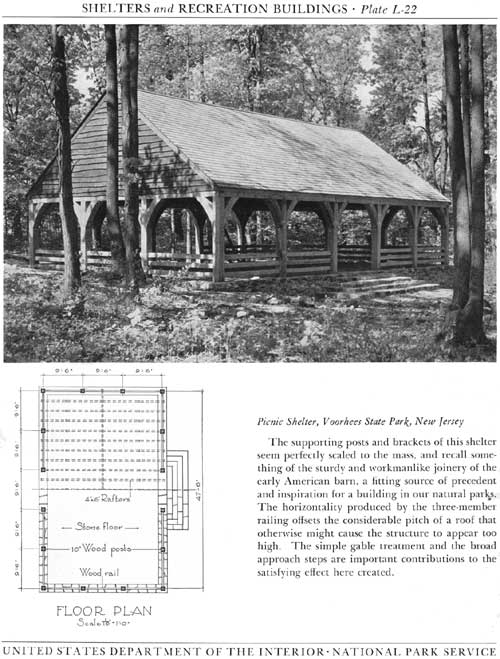

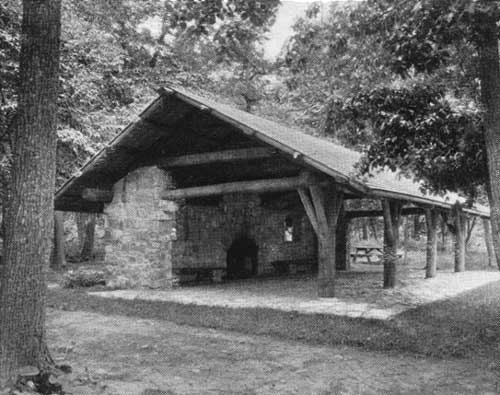

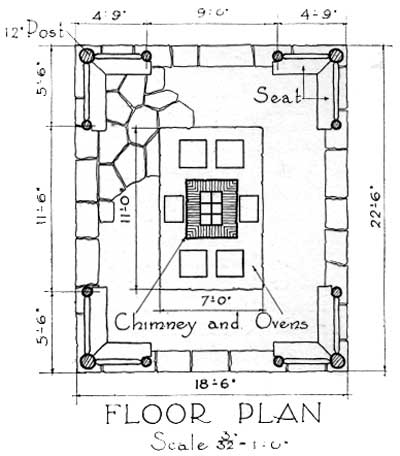

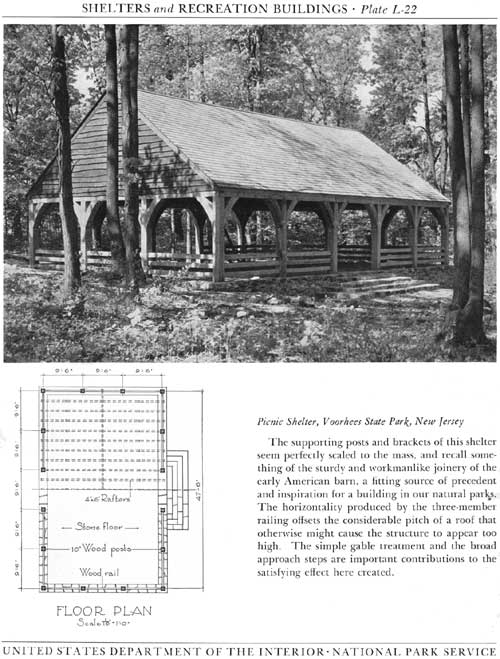

Picnic Shelter, Voorhees State Park, New Jersey

The supporting posts and brackets of this shelter

seem perfectly scaled to the mass, and recall something of the sturdy

and workmanlike joinery of the early American barn, a fitting source of

precedent and inspiration for a building in our natural parks. The

horizontality produced by the three-member railing offsets the

considerable pitch of a roof that otherwise might cause the structure to

appear too high. The simple gable treatment and the broad approach steps

are important contributions to the satisfying effect here created.

|

|

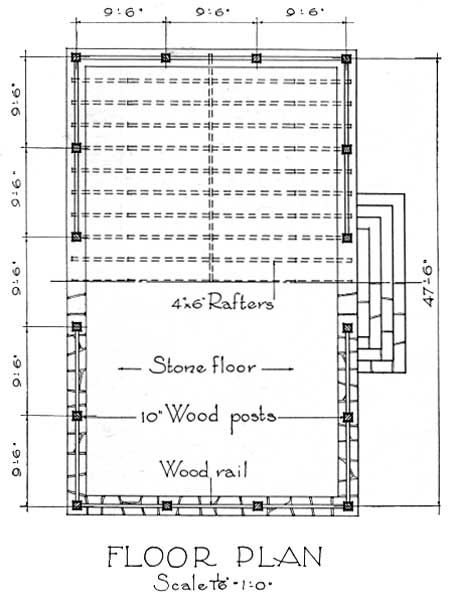

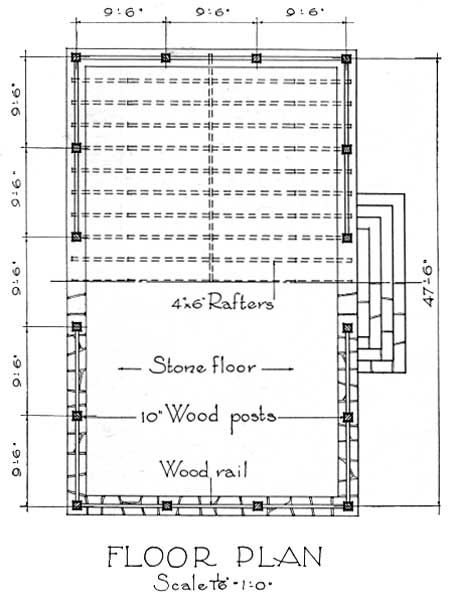

Plate L-22 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Voorhees State Park, New Jersey

|

|

|

Voorhees State Park, New Jersey

|

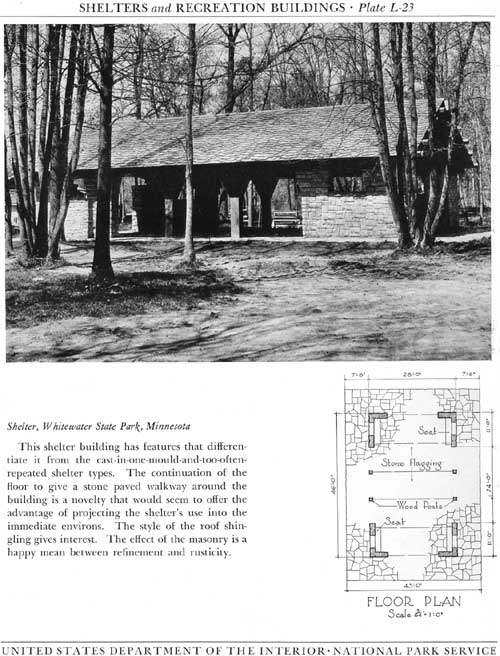

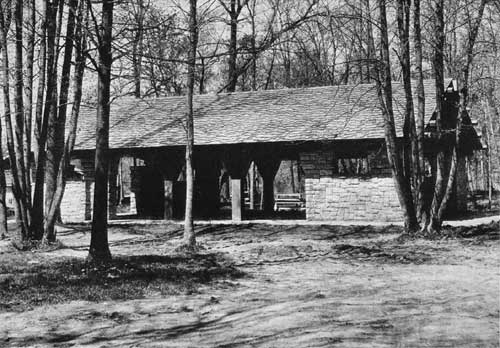

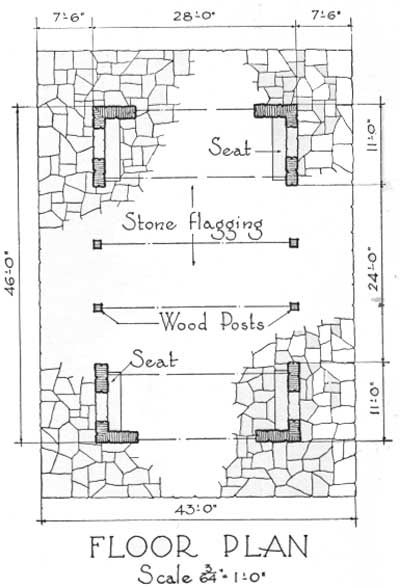

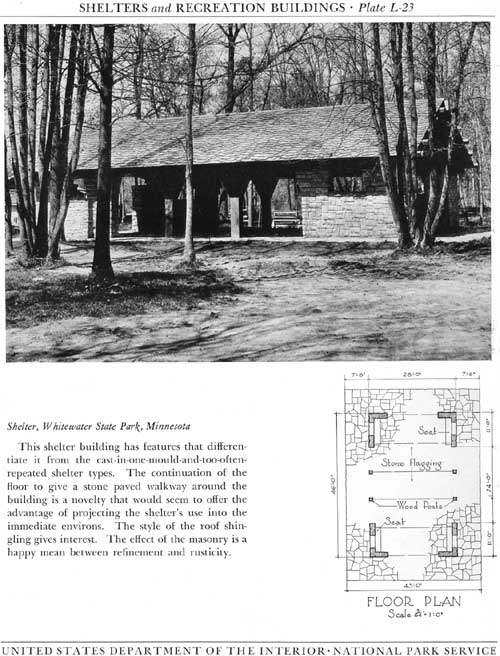

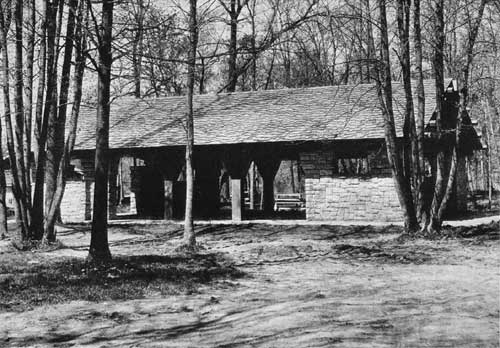

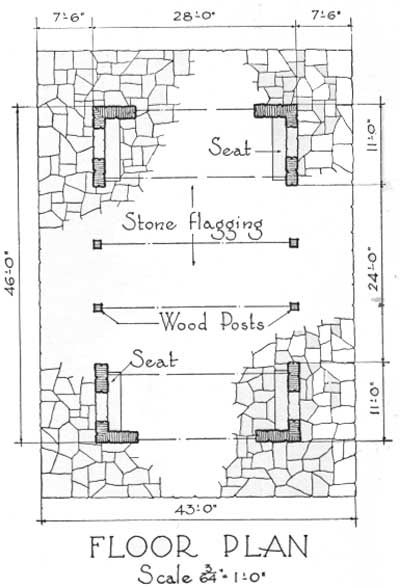

Shelter, Whitewater State Park, Minnesota

This shelter building has features that differentiate

it from the cast-in-one-mould-and-too-often-repeated shelter types. The

continuation of the floor to give a stone paved walkway around the

building is a novelty that would seem to offer the advantage of

projecting the shelter's use into the immediate environs. The style of

the roof shingling gives interest. The effect of the masonry is a happy

mean between refinement and rusticity.

|

|

Plate L-23 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Whitewater State Park, Minnesota

|

|

|

Whitewater State Park, Minnesota

|

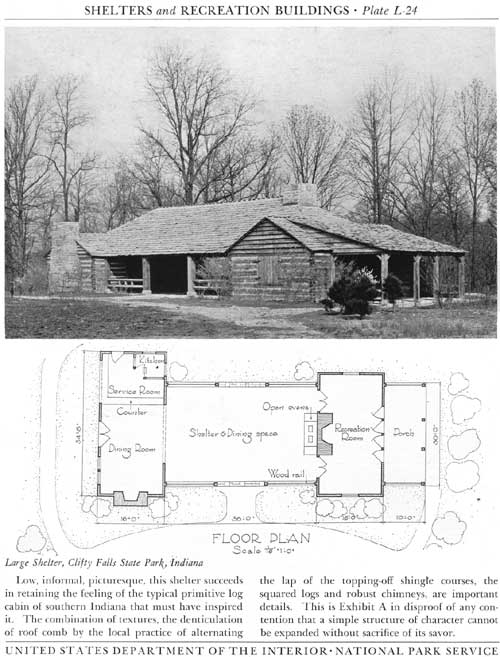

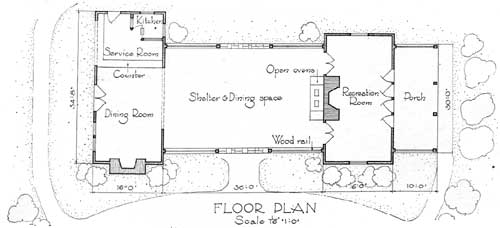

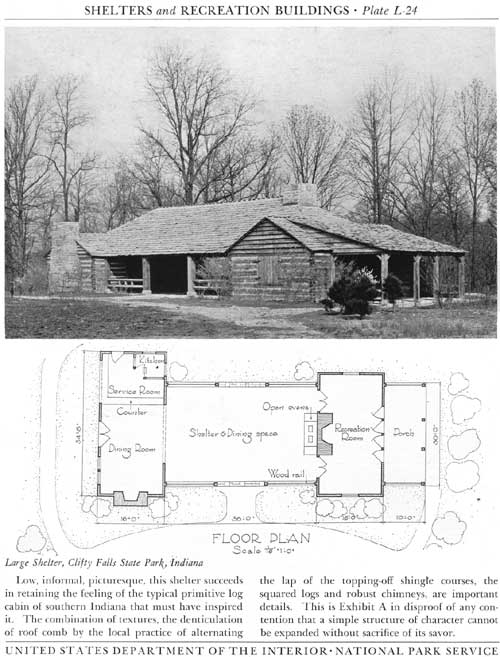

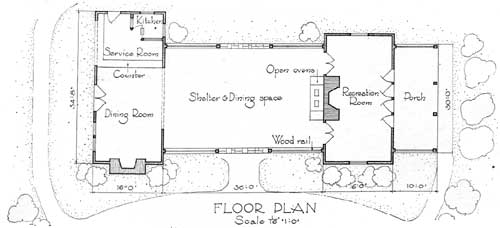

Large Shelter, Clifty Falls State Park, Indiana

Low, informal, picturesque, this shelter succeeds in

retaining the feeling of the typical primitive log cabin of southern

Indiana that must have inspired it. The combination of textures, the

denticulation of roof comb by the local practice of alternating the lap

of the topping-off shingle courses, the squared logs and robust

chimneys, are important details. This is Exhibit A in disproof of any

contention that a simple structure of character cannot be expanded

without sacrifice of its savor.

|

|

Plate L-24 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Clifty Falls State Park, Indiana

|

|

|

Clifty Falls State Park, Indiana

|

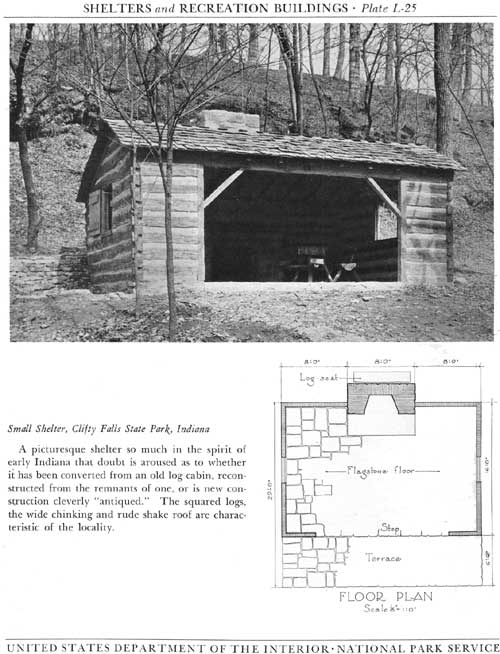

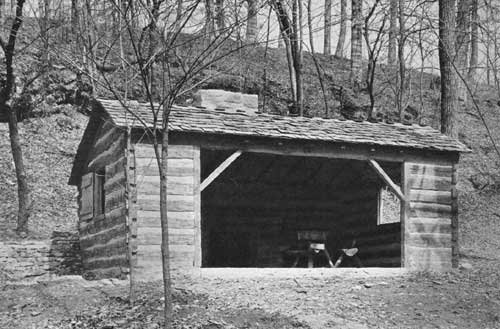

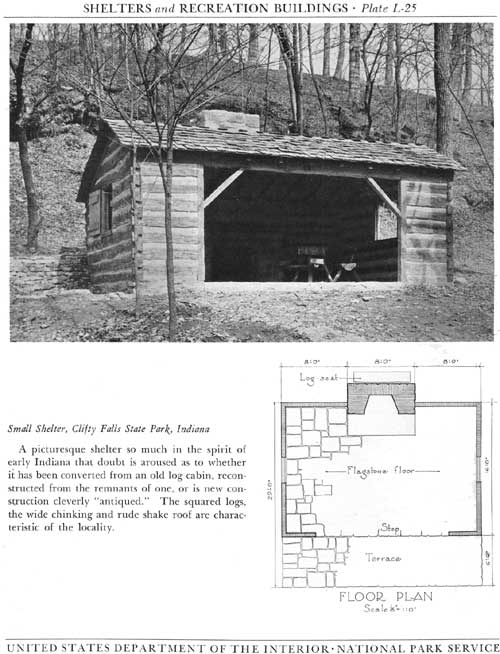

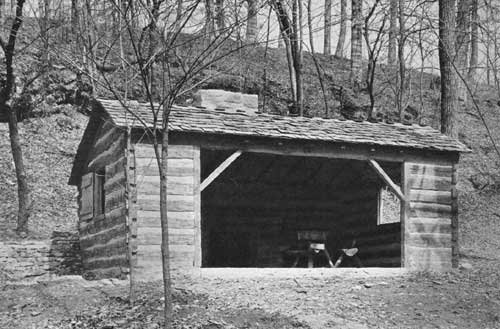

Small Shelter, Clifty Falls State Park, Indiana

A picturesque shelter so much in the spirit of early

Indiana that doubt is aroused as to whether it has been converted from

an old log cabin, reconstructed from the remnants of one, or is new

construction cleverly "antiqued." The squared logs, the wide chinking

and rude shake roof are characteristic of the locality.

|

|

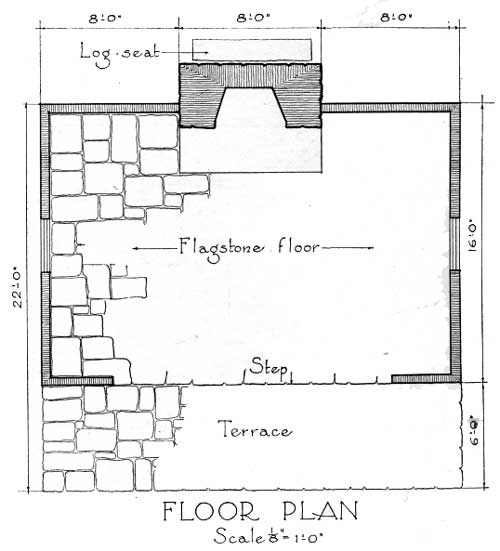

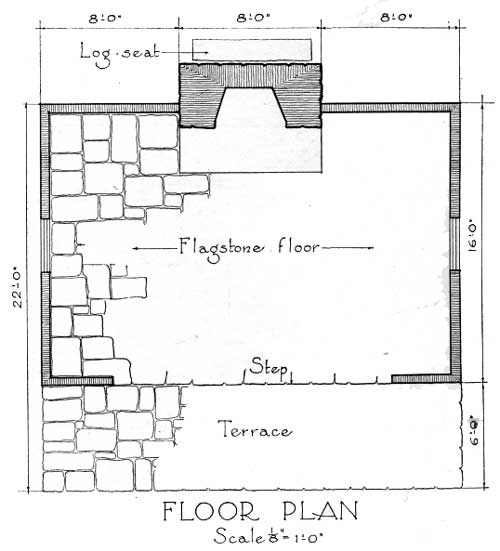

Plate L-25 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Clifty Falls State Park, Indiana

|

|

|

Clifty Falls State Park, Indiana

|

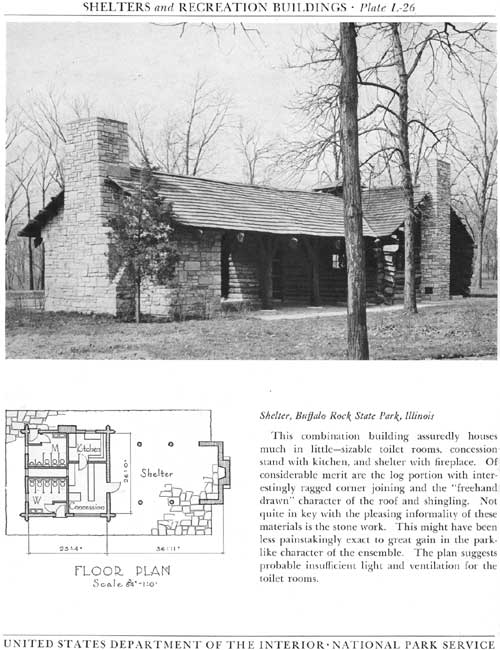

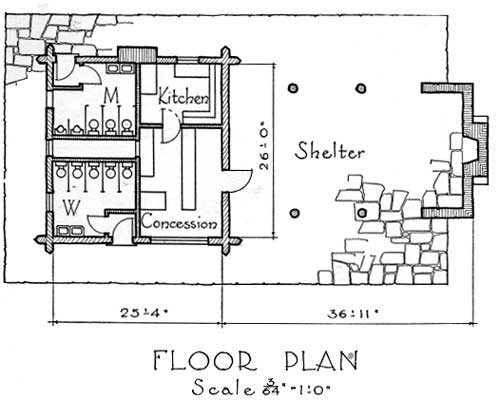

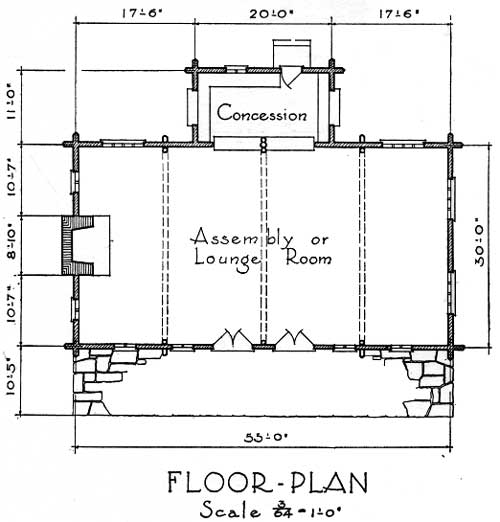

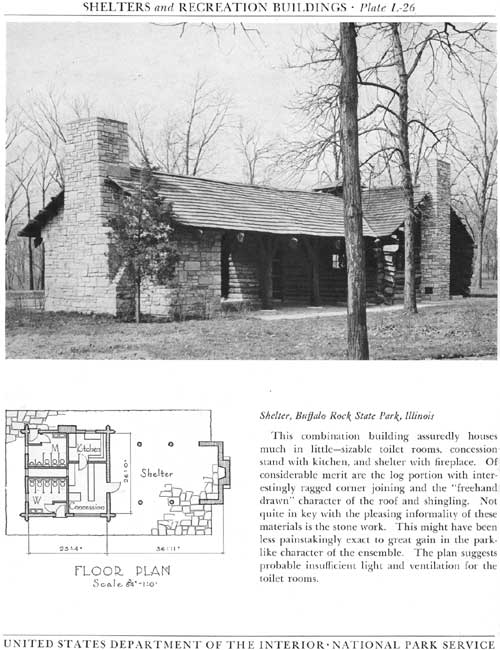

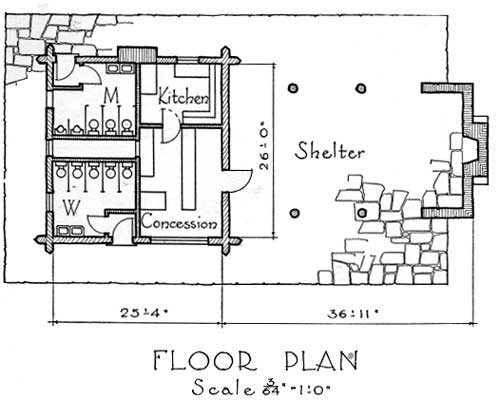

Shelter, Buffalo Rock State Park, Illinois

This combination building assuredly houses much in

little—sizable toilet rooms, concession stand with kitchen, and

shelter with fireplace. Of considerable merit are the log portion with

interestingly ragged corner joining and the "freehand drawn" character

of the roof and shingling. Not quite in key with the pleasing

informality of these materials is the stone work. This might have been

less painstakingly exact to great gain in the park-like character of the

ensemble. The plan suggests probable insufficient light and ventilation

for the toilet rooms.

|

|

Plate L-26 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Buffalo Rock State Park, Illinois

|

|

|

Buffalo Rock State Park, Illinois

|

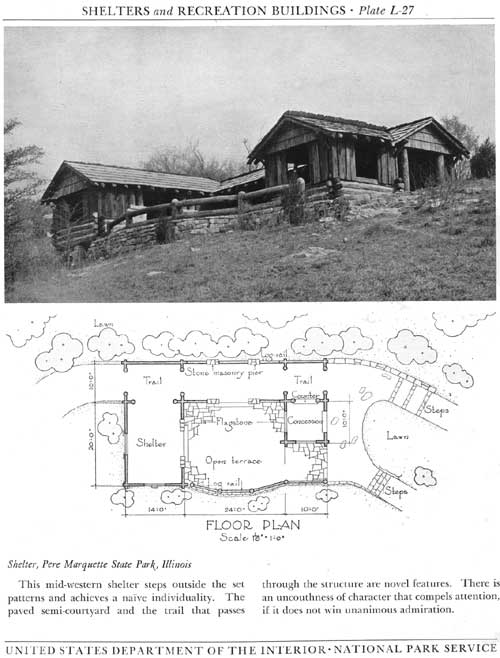

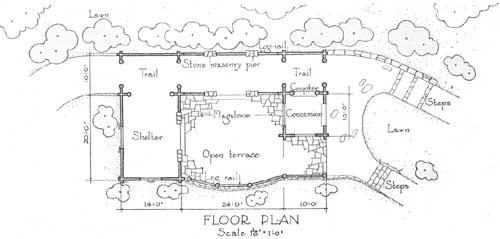

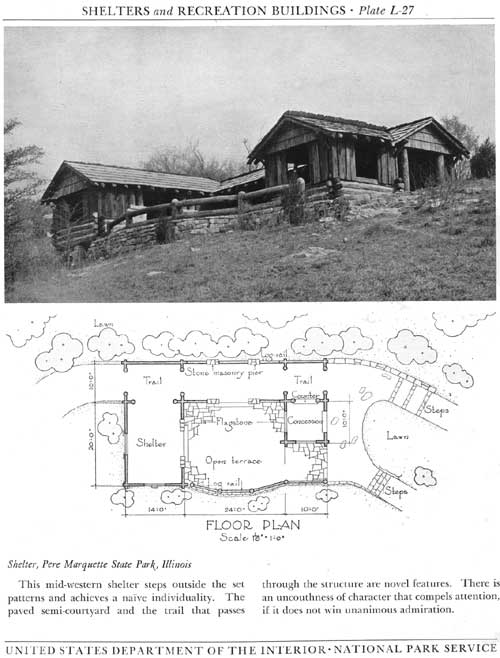

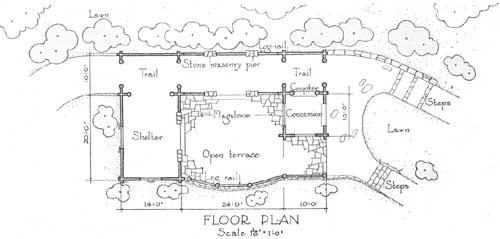

Shelter, Pere Marquette State Park, Illinois

This mid-western shelter steps outside the set

patterns and achieves a naive individuality. The paved semi-courtyard

and the trail that passes through the structure are novel features.

There is an uncouthness of character that compels attention, if it does

not win unanimous admiration.

|

|

Plate L-27 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Pere Marquette State Park, Illinois

|

|

|

Pere Marquette State Park, Illinois

|

Shelter, Mohawk Park, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Evidencing brilliant indifference to the hackneyed in

shelter plans, and a handling of materials free of hampering dictates of

tradition, here is a building that gives promise of an eventual American

park architecture. This accomplishment owes much to the irregularity of

the shingle courses, the curiously blunted beavering of the rafter ends

and the carefully careless ragged batter of the stone walls from grade

to sill of openings.

|

|

Plate L-28 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Mohawk Park, Tulsa, Oklahoma

|

|

|

Mohawk Park, Tulsa, Oklahoma

|

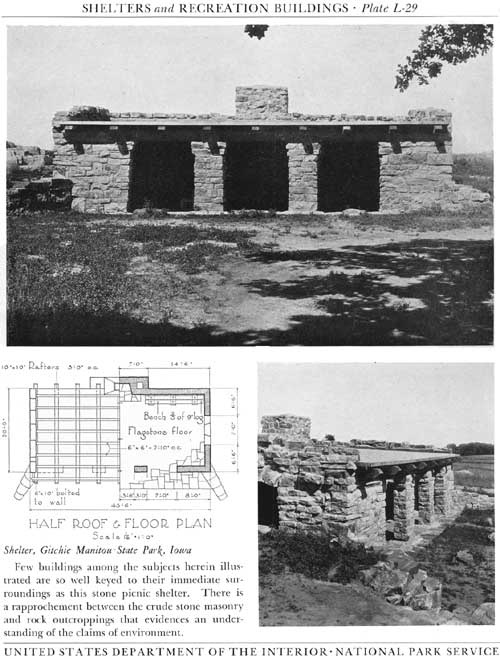

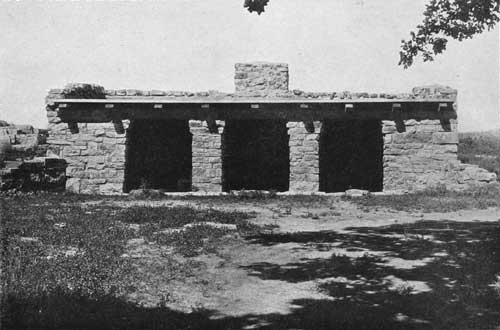

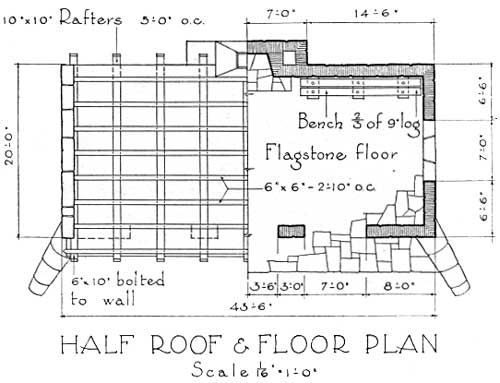

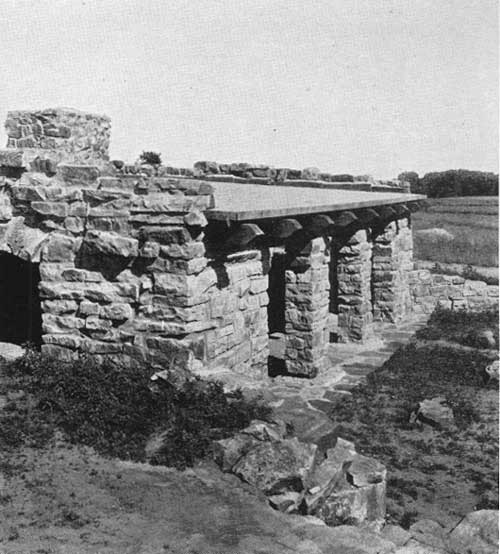

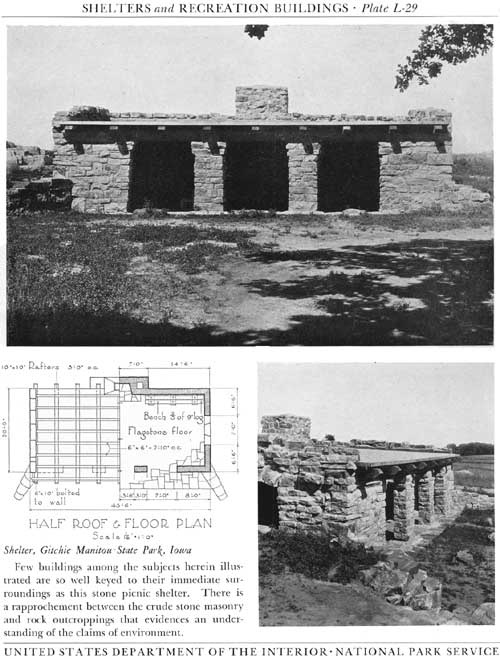

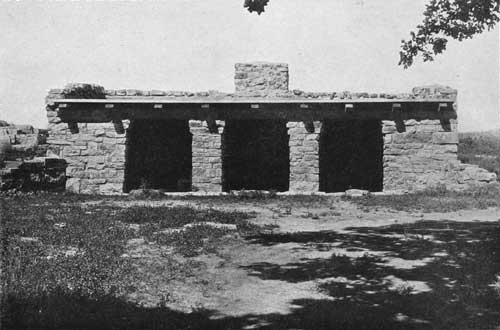

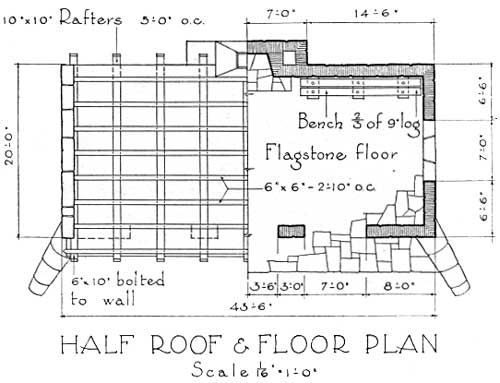

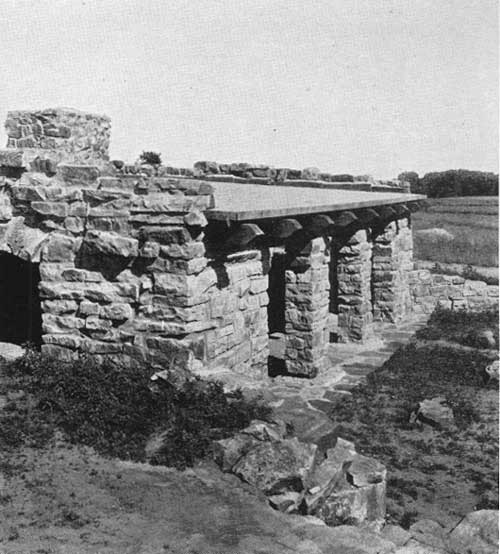

Shelter, Gitchie Manitou State Park, Iowa

Few buildings among the subjects herein illustrated

are so well keyed to their immediate surroundings as this stone picnic

shelter. There is a rapprochement between the crude stone masonry and

rock outcroppings that evidences an understanding of the claims of

environment.

|

|

Plate L-29 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Gitchie Manitou State Park, Iowa

|

|

|

Gitchie Manitou State Park, Iowa

|

|

|

Gitchie Manitou State Park, Iowa

|

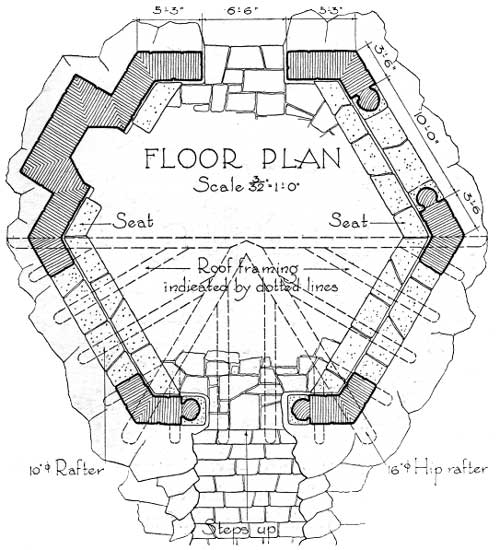

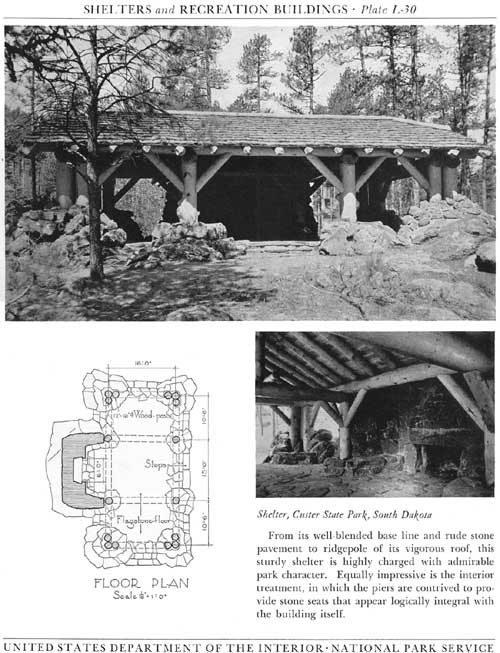

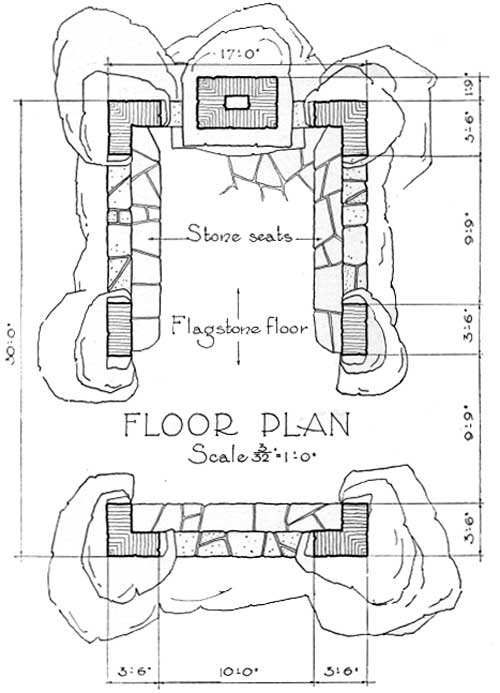

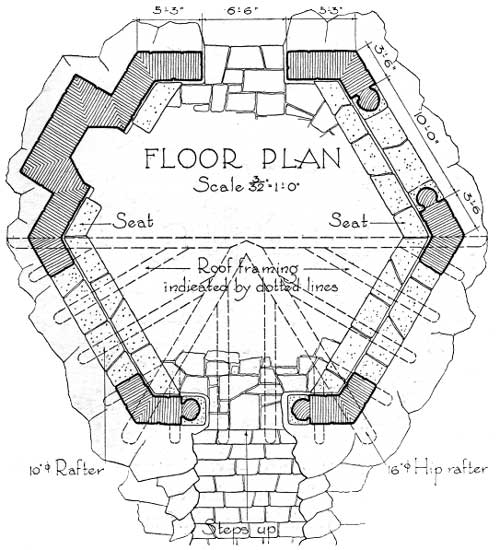

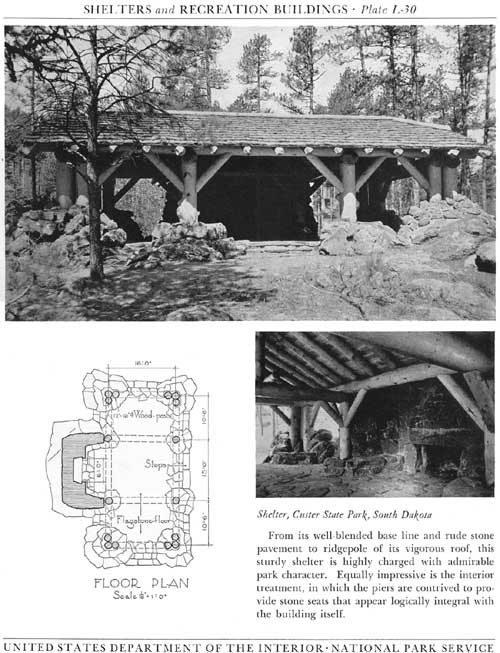

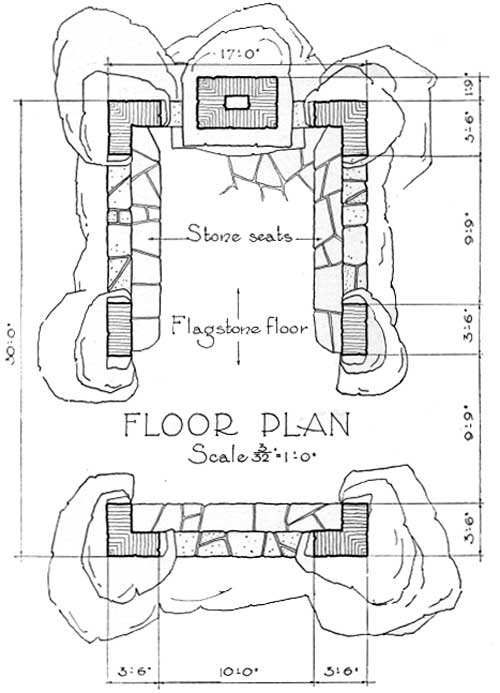

Shelter, Custer State Park, South Dakota

From its well-blended base line and rude stone

pavement to ridgepole of its vigorous roof, this sturdy shelter is

highly charged with admirable park character. Equally impressive is the

interior treatment, in which the piers are contrived to provide stone

seats that appear logically integral with the building itself.

|

|

Plate L-30 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Custer State Park, South Dakota

|

|

|

Custer State Park, South Dakota

|

|

|

Custer State Park, South Dakota

|

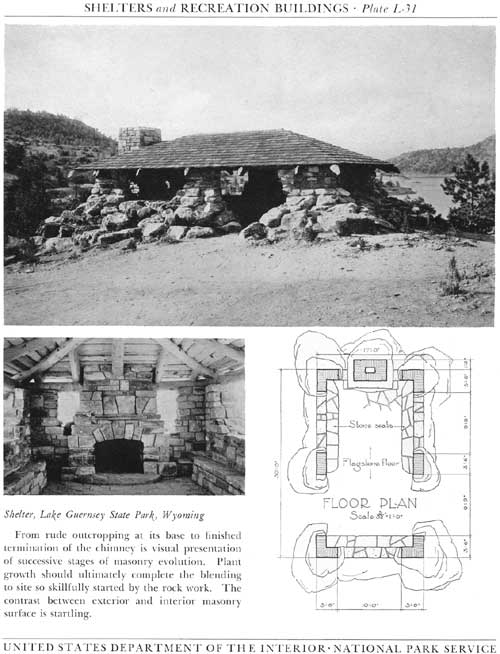

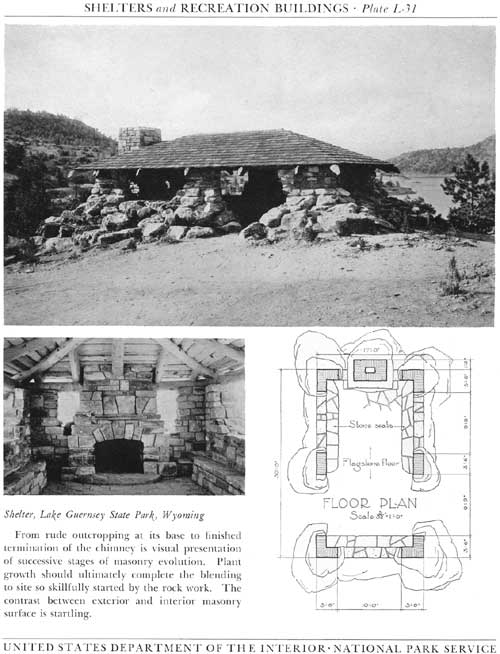

Shelter, Lake Guernsey State Park, Wyoming

From rude outcropping at its base to finished

termination of the chimney is visual presentation of successive stages

of masonry evolution. Plant growth should ultimately complete the

blending to site so skillfully started by the rock work. The contrast

between exterior and interior masonry surface is startling.

|

|

Plate L-31 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Lake Guernsey State Park, Wyoming

|

|

|

Lake Guernsey State Park, Wyoming

|

|

|

Lake Guernsey State Park, Wyoming

|

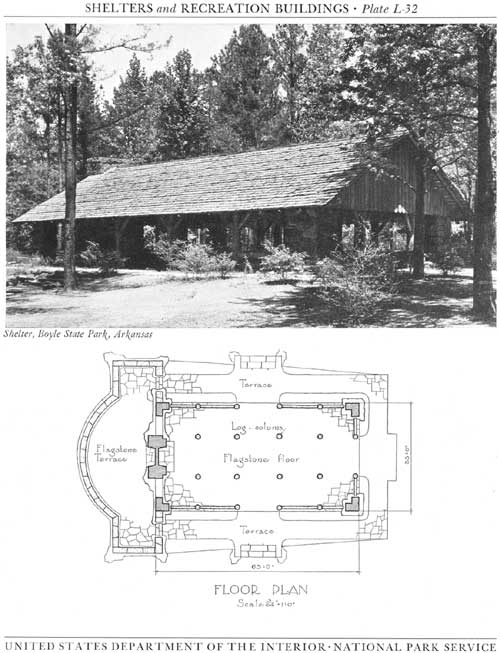

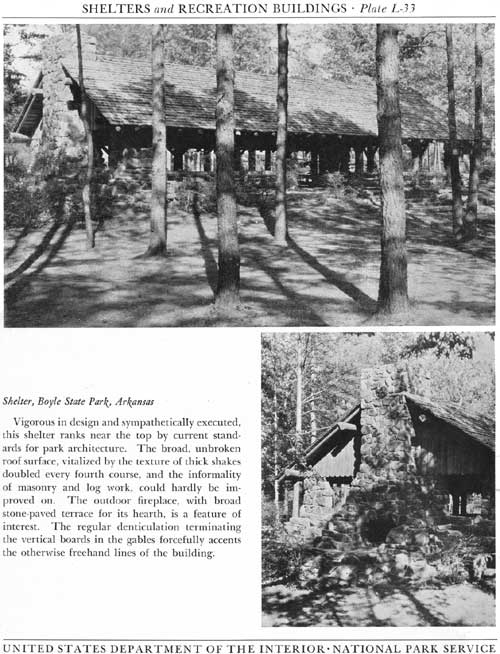

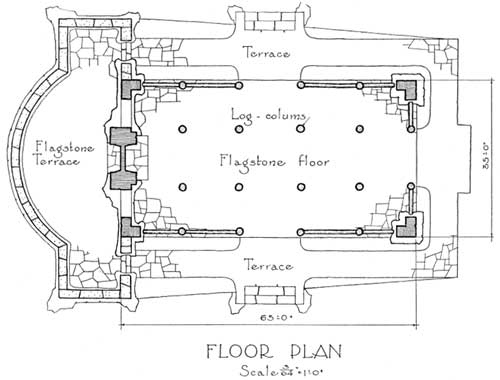

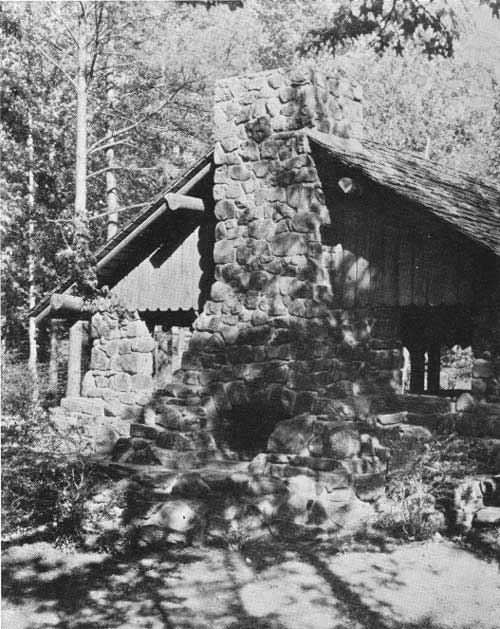

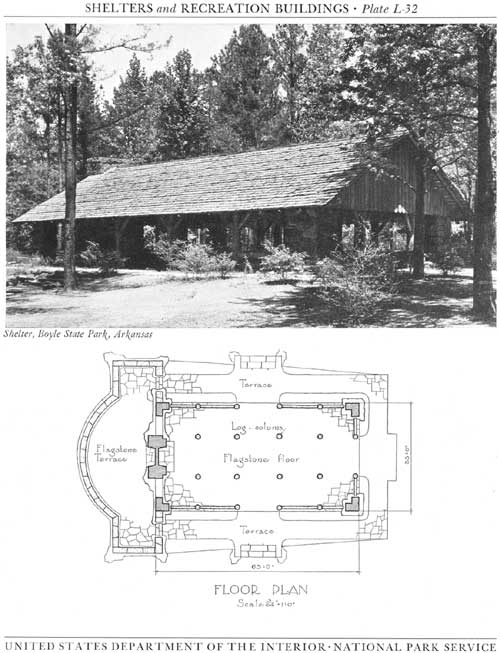

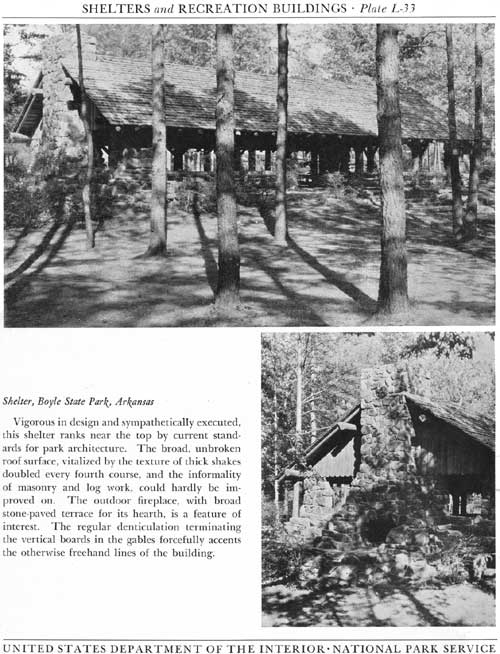

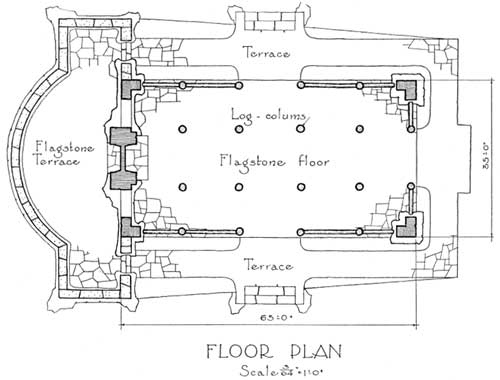

Shelter, Boyle State Park, Arkansas

Vigorous in design and sympathetically executed, this

shelter ranks near the top by current standards for park architecture.

The broad, unbroken roof surface, vitalized by the texture of thick

shakes doubled every fourth course, and the informality of masonry and

log work, could hardly be improved on. The outdoor fireplace, with broad

stone-paved terrace for its hearth, is a feature of interest. The

regular denticulation terminating the vertical boards in the gables

forcefully accents the otherwise freehand lines of the building.

|

|

Plate L-32 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Plate L-33 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Boyle State Park, Arkansas

|

|

|

Boyle State Park, Arkansas

|

|

|

Boyle State Park, Arkansas

|

|

|

Boyle State Park, Arkansas

|

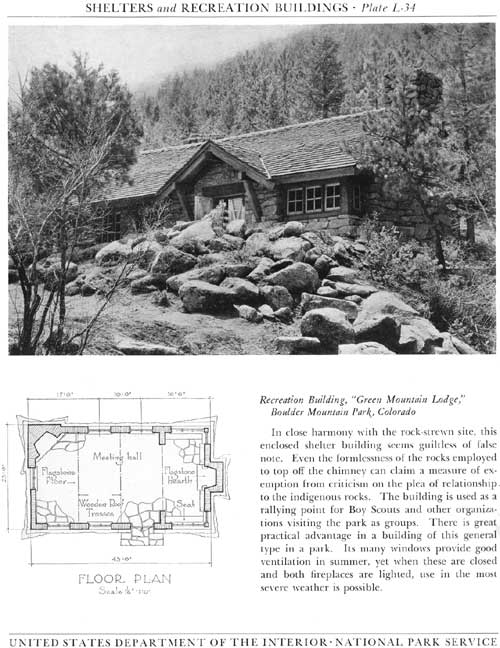

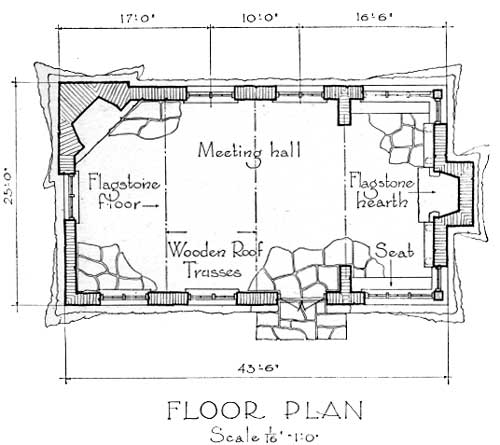

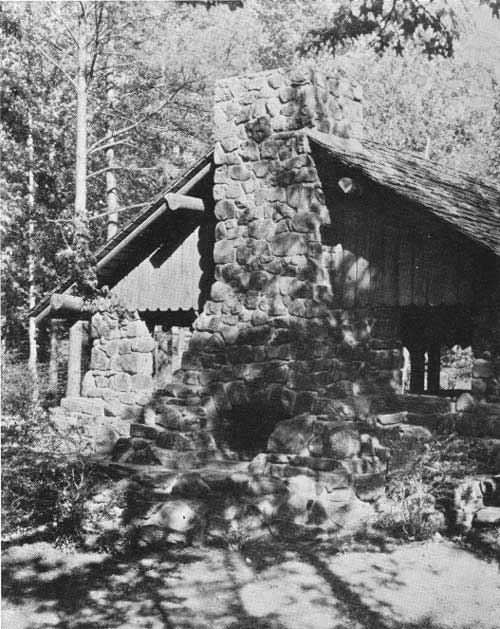

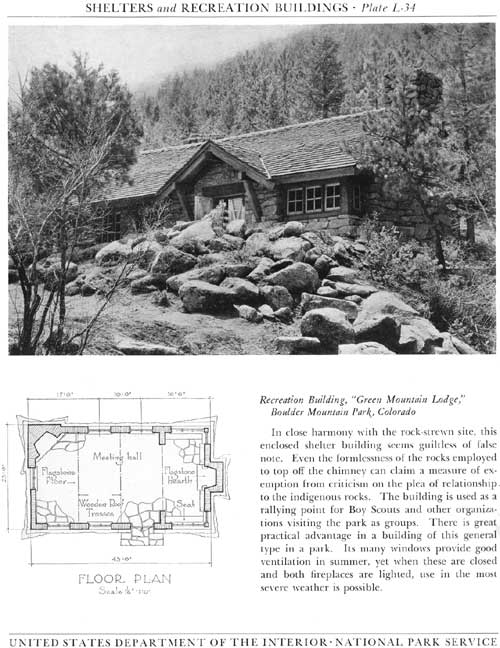

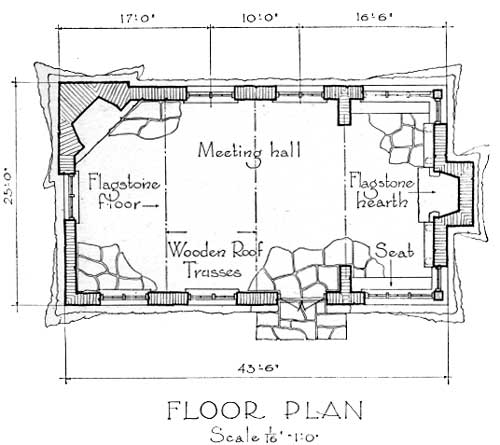

Recreation Building, "Green Mountain Lodge," Boulder Mountain Park, Colorado

In close harmony with the rock-strewn site, this

enclosed shelter building seems guiltless of false note. Even the

formlessness of the rocks employed to top off the chimney can claim a

measure of exemption from criticism on the plea of relationship to the

indigenous rocks. The building is used as a rallying point for Boy

Scouts and other organizations visiting the park as groups. There is

great practical advantage in a building of this general type in a park.

Its many windows provide good ventilation in summer, yet when these are

closed and both fireplaces are lighted, use in the most severe weather

is possible.

|

|

Plate L-34 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

"Green Mountain Lodge," Boulder Mountain Park, Colorado

|

|

|

"Green Mountain Lodge," Boulder Mountain Park, Colorado

|

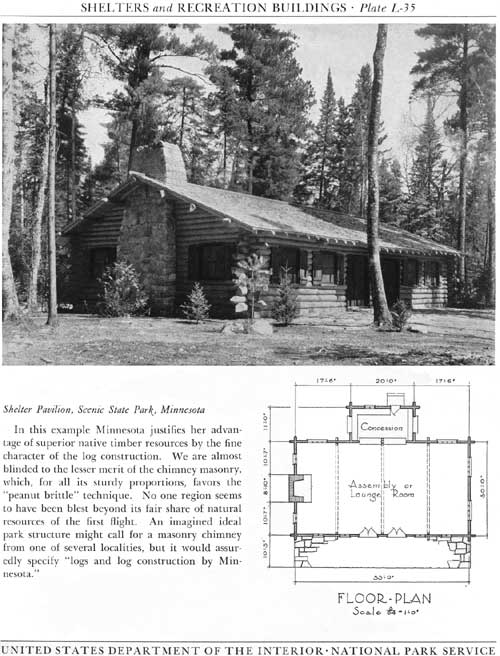

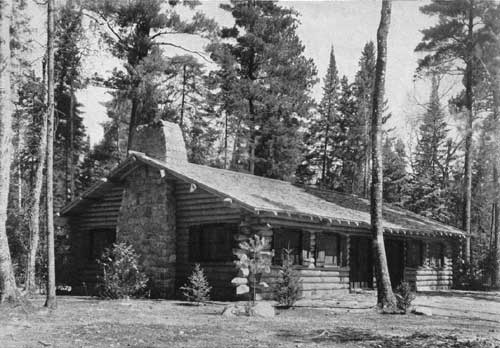

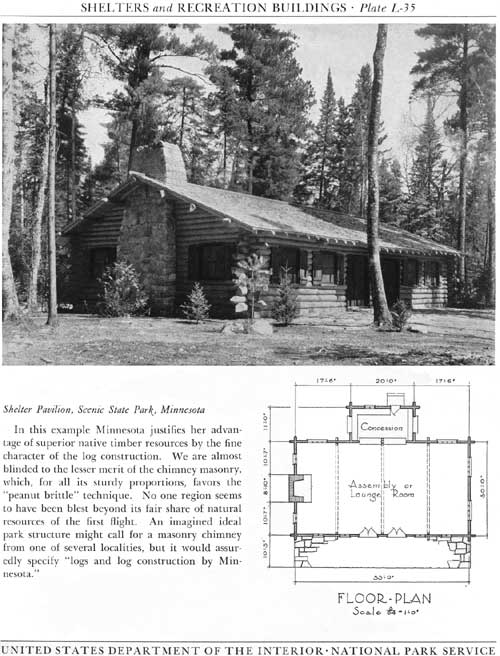

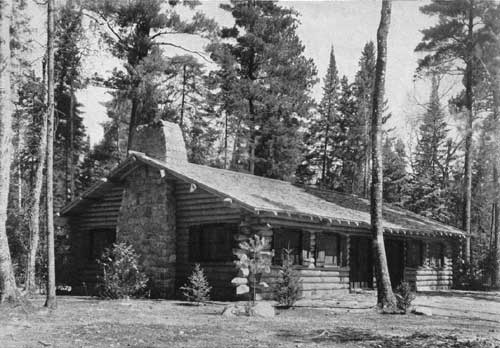

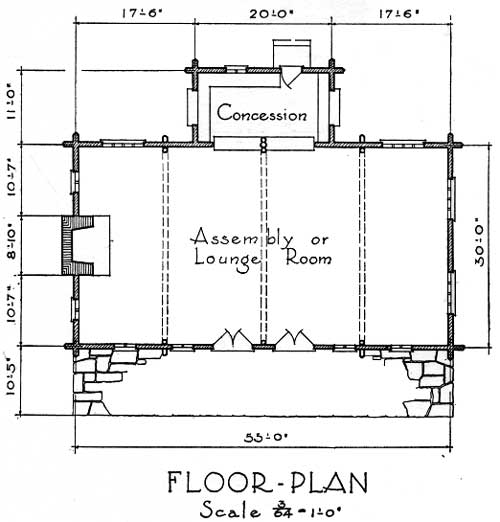

Shelter Pavilion, Scenic State Park, Minnesota

In this example Minnesota justifies her advantage of

superior native timber resources by the fine character of the log

construction. We are almost blinded to the lesser merit of the chimney

masonry, which, for all its sturdy proportions, favors the "peanut

brittle" technique. No one region seems to have been blest beyond its

fair share of natural resources of the first flight. An imagined ideal

park structure might call for a masonry chimney from one of several

localities, but it would assuredly specify "logs and log construction by

Minnesota."

|

|

Plate L-35 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Scenic State Park, Minnesota

|

|

|

Scenic State Park, Minnesota

|

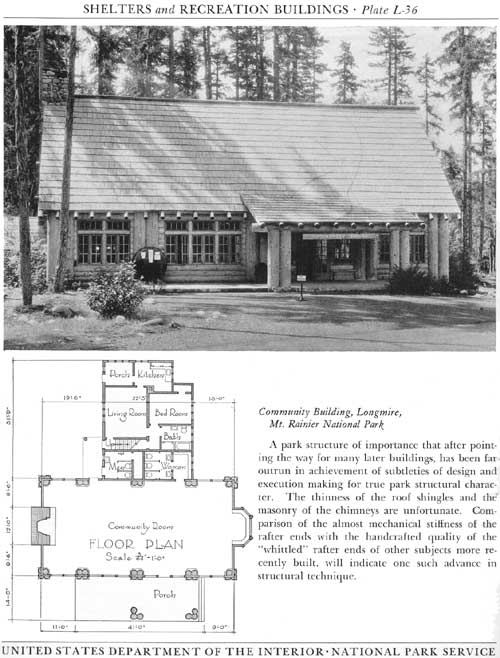

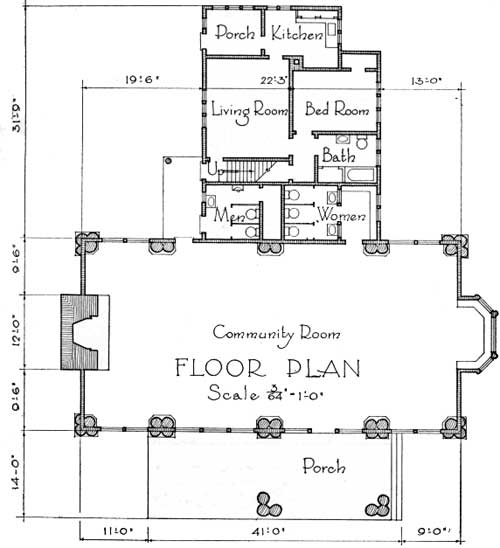

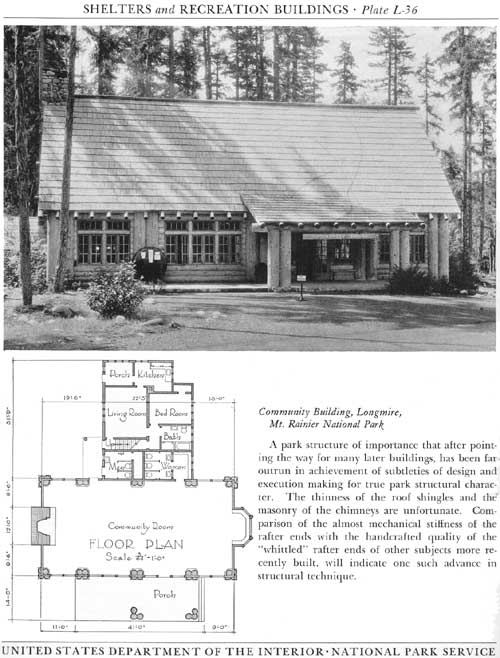

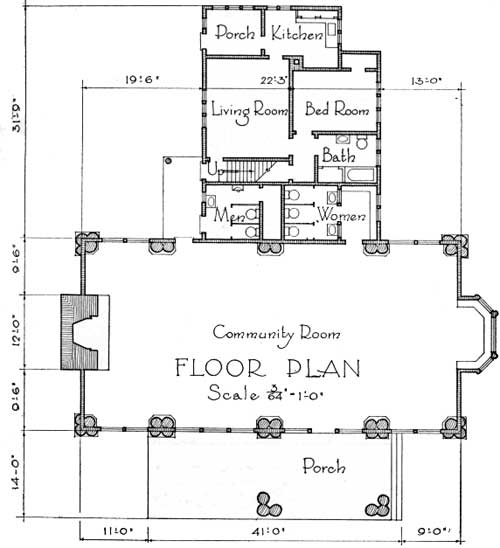

Community Building, Longmire, Mt. Rainier National Park

A park structure of importance that after pointing

the way for many later buildings, has been far outrun in achievement of

subtleties of design and execution making for true park structural

character. The thinness of the roof shingles and the masonry of the

chimneys are unfortunate. Comparison of the almost mechanical stiffness

of the rafter ends with the handcrafted quality of the "whittled" rafter

ends of other subjects more recently built, will indicate one such

advance in structural technique.

|

|

Plate L-36 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Longmire, Mt. Rainier National Park

|

|

|

Longmire, Mt. Rainier National Park

|

park_structures_facilities/secl.htm

Last Updated: 5-Dec-2011

|