NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Park Structures and Facilities

|

|

CABINS

AMONG BUILDINGS THAT HAVE COME to be regarded as on

occasion justified within our present conception of a natural park, the

cabin alone has the favorable advantage of long familiarity to us in

woodland and meadow. So accustomed have we become to the survivals of

frontier cabins that dot the countryside that we have grown to look upon

them as almost indigenous to a natural setting. Of all park structures,

those cabins which echo the pioneer theme in their outward appearance,

whether constructed of logs, shakes or native stone, tend to jar us

least with any feeling that they are unwelcome. The fact that park

cabins are usually erected in colonies or groups—which frontier

cabins as a rule were not—destroys the feeling of almost complete

fitness that is produced by a single primitive cabin. The further fact

that the true cost of such structures is usually much higher than their

purpose or the prospective income from them would justify imposes upon

the designer the necessity of availing himself of cheaper and more

easily handled materials, and of using them the best way he can. Hence

these groups are something of a dissonance in parks, acceptable only

when their obtrusiveness is minimized insofar as possible.

When occupied, the cabin becomes in effect private

property, serving an infinitesimal portion of the park-using public. In

consequence, if the cabin on public lands is to justify itself it is

essential that it at least pay its way during its lifetime, and that

charges for its use should bear a logical relationship to its true cost.

Any evaluation of that cost which fails to assign a reasonable value to

materials acquired on the site or to all labor, however compensated,

would be faulty.

A tendency frequently observed in connection with

cabin groups is to spread the effects of their presence over a

needlessly large area, on the assumption that the occupants of each are

entitled to complete seclusion. In groups composed of the simplest

cabin types this either compels a multiplication of toilet installations

or renders the use of central facilities so difficult that the cabin

occupant, particularly after dark, will frequently not go to the

required trouble, with consequent development of unpleasant and

unsanitary conditions. It also compels establishment of additional water

outlets—one more item of cost.

Even in the case of cabin groups equipped with

toilets and with running water, wide separation means added road

construction to make them accessible and greatly increased costs of

water distribution and sewage disposal. After all it seems fair to

assume that where cabins are erected in parks, their purpose is to

facilitate enjoyment of the park itself and that complete seclusion

during the hours when they are occupied is not the supremely important

goal it is so frequently assumed to be.

Often overlooked, but certainly the primary objective

in providing cabins in public parks, should be adjustment of cost and

facilities to the income range of the using public. There ought to be

just as sincere effort to make habitable vacation shelter available to

the patron of very limited means as there now exists an enthusiasm to

supply the more ample facilities which the higher income brackets can

afford and demand. Reasonable assumption of a range of rentals suggests

the logic of three basic types of vacation cabins. A large proportion

may well provide accommodations for five persons as the average American

family group.

The simplest type of cabin, the "Student" or

"Tourist" class (to initiate the figure of the passenger liner), must

seek to bring the required minimum of space need in shelter within a

most rigid limitation of cost, which must bear an arithmetical relation

to the very limited rent the humble park user can afford to pay. This

problem will tax the ingenuity of the ablest designer capable and

desirous of producing a nice relationship between traditional charm and

reasoned practicability. Of necessity such a cabin must be a very simple

affair, affording merely the most compact of sleeping accommodations and

small living space. In many localities an open or screened porch will be

desirable or necessary. But required economy will compel the omission of

toilet and bathing facilities, and even fireplace and kitchen that is

more than mere cabinet, alcove or closet, from this simplest type of

cabin. Group toilet and bathing facilities, and provision of very

limited and compact kitchen equipment will naturally reduce the cabin

unit cost, as compared with that of cabin groups in which toilet,

bathing and more complete cooking facilities are integral parts of each

cabin. A possible alternative for the very modest kitchen allowable

within the simplest cabin is an outdoor camp stove, preferably with

sheltering roof. If strategically located the camp stove may be a

multiple unit and the kitchen shelter thus made to serve several cabins.

Such is the prospectus for recreational or vacational cabin housing

within the normal budget range of the great majority, and possible then,

it should be borne in mind, for brief periods only and by dint of the

most careful economy on the part of the family unit.

A narrowing field of potential users results when

more ample space and added facilities, naturally accompanied by mounting

costs and proportionately higher rental charges, are offered in "Second

Cabin Class." Cabins of this type contain two rooms and a kitchenette.

Both rooms should provide for sleeping. The kitchenette will tend to be

something more than the simpler cabin type provides. A fireplace is an

allowable feature, since the larger cabin will probably have a longer

season of use. In the absence of a central recreation building as a

gathering place, the cabin unit is forced to a greater self-sufficiency.

Toilet and bath facilities within this class of cabin, while certainly

to be desired, are hardly to be encouraged, in the face of the cost of

these accessories.

The distinguishing features of cabins of the next

group, the "First Cabin Class," are toilet and bath facilities, along

with perhaps added spaciousness and greater privacy in sleeping

quarters. Arbitrary pronouncement of limitations in space and facilities

for these cabins is considered beyond the province of this general

discussion.

When examples of the "First Cabin Class" give hint of

elaboration to the point of becoming "Cabins de Luxe" or "Royal Suites"

their appropriateness within natural parks will be challenged by many

and defended by a few. Certainly such cabins are only justifiable if the

vacancy ratio is negligible.

At the lack of spread in cabin facilities and rentals

observable in many parks, just criticism can be leveled. It would seem

not only to be better park planning, but better business planning, to

have accommodations to offer over a wide price range and bearing some

logical ratio to the wide income range that prevails among park patrons.

It might be pointed out as an abuse of democratic principles if the

benefits of park areas are withdrawn from availability to the many to

the selfish enjoyment of the few. An abundant provision of cabins such

as only the few can afford, and a blind, or calloused, disregard of the

budget limits of the vast majority, are not social arithmetic.

It is not argued that the several "classes" of

cabins must rub elbows in the park area as a condition of serving with

equality the patrons of different social or financial strata. On the

contrary, this is something to be rigidly avoided in layout. There is

less emphasis on social differences and therefore less dissatisfaction

for all concerned in a discreet grouping of cabins of each type somewhat

to themselves.

While many cabins have been built as a single room

large enough to provide sleeping accommodations for an average family,

it is desirable even in such simple cabins to afford dressing space

privacy by means of partitions, or curtains on poles, around one or

more of the bed locations. Furthermore, the potential tenants are not

always a family group, and failure to provide some measure of privacy

results in a narrowing down of the tenant field.

Among space-saving possibilities to be carefully

weighed by cabin designers with praiseworthy urge to provide the utmost

for the cabin dollar, a wide opening between the enclosed living space

and the screened porch is to be especially recommended. Such an opening

about eight feet wide, and framing three- or four-fold, or sliding,

doors, by throwing together the limited space allotments of living space

and porch, makes for a spaciousness much desired on occasion.

Something on the subject of chimneys cries to be

heard, and since chimneys have no separate entity in these discussions,

their case must be presented and pressed by cabins, as "next

friend."

In the "what-not" or "mission" period of the

discredited past, some individualist seems to have been possessed of a

grim determination and an hypnotic ability to implant his school of

debased thought in chimneys for log cabins through the length and

breadth of the land. It must have been the life-long fixation of one

crusading apostle. Nothing else will account for such far-flung and

ardent faith in the sole and supreme appropriateness of boulder masonry

for this purpose. The unfortunate circumstance is further aggravated by

a quaint conviction that the less structural in appearance, the less

evident the bonding mortar, and the less apparent any reliance on

physical laws for stability, the happier and more creditable the

accomplishment. Need it be more than pointed out that from time

immemorial good stonework has always been that stonework which appears

incapable of toppling even if all mortar were to be magically removed?

It is highly possible that recurrently through history there have been

revolutionary viewpoints determined to go counter to what probably

seemed at the moment just trite and old-fashioned in masonry technique.

This is mere speculation, of course, because somehow the evidence

of such revolutionary experimentation, except that of the cited sponsor

of "peanut brittle" or "grape cluster" chimney techniques for log

cabins, has not survived the ravages of time to our day. It is indeed

regrettable that this non-survival went unnoted by the most recent

proponent, whose disciples, over the years, might have been spared many

chimney replacements which, if not necessitated by actual collapse, then

certainly blasted to ruin by the trumpets of good taste. As from time to

time these reconstructions must be made, it is hoped that the

reconstructors will appraise the chimney survivals of the American

pioneer, and if they are led to offend with globular masonry no more

often than did he, a weird ghost will have been laid.

When the timber resources of the American frontier

seemed limitless, it was usual to lay the starting logs of a cabin

directly on the ground, without supporting stone foundations. When after

a time the logs in contact with the earth had rotted to a point where

the cabin commenced to list and sag, another cabin was built and the

earlier one abandoned. This, it seems, in the economy of the frontier,

was more reasonable than to have provided a foundation under the earlier

cabin. Regardless of the pious respect a log cabin builder of the

present must have for the traditions of the past, the changed economy of

our day demands that his cabin be preserved against deterioration by the

use of masonry or concrete supporting walls or posts that extend well

above grade.

|

|

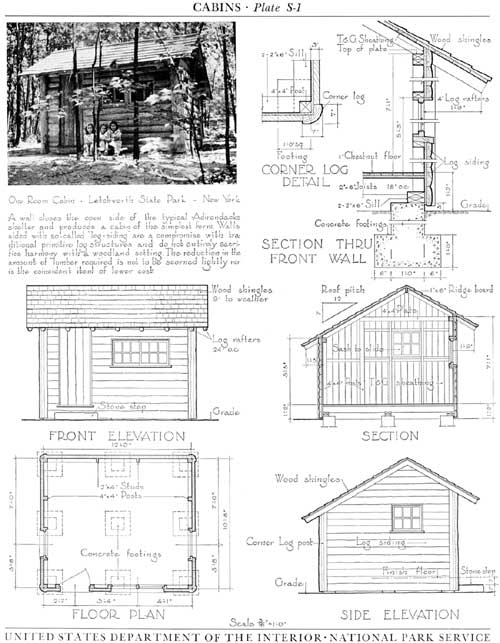

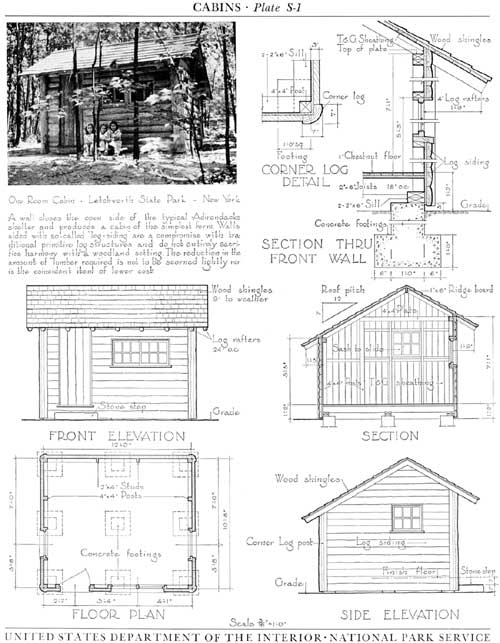

Plate S-1 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

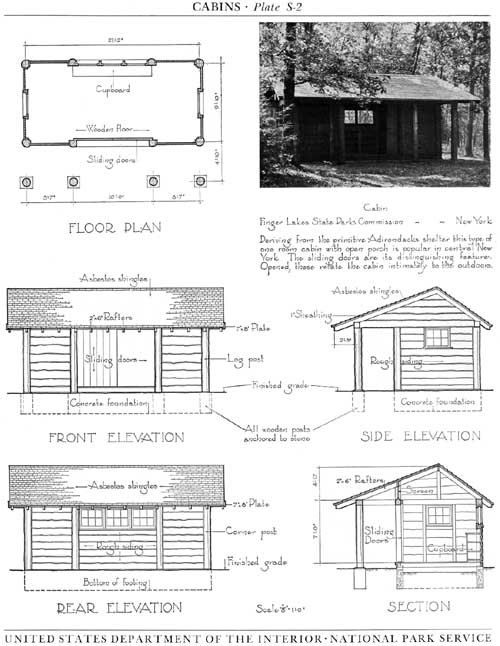

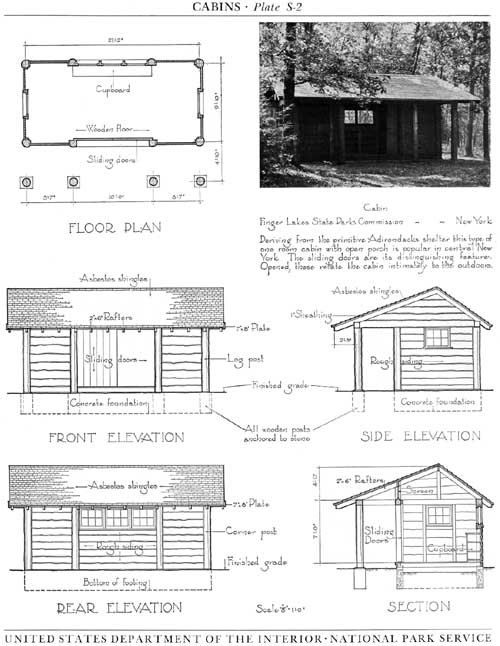

Plate S-2 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

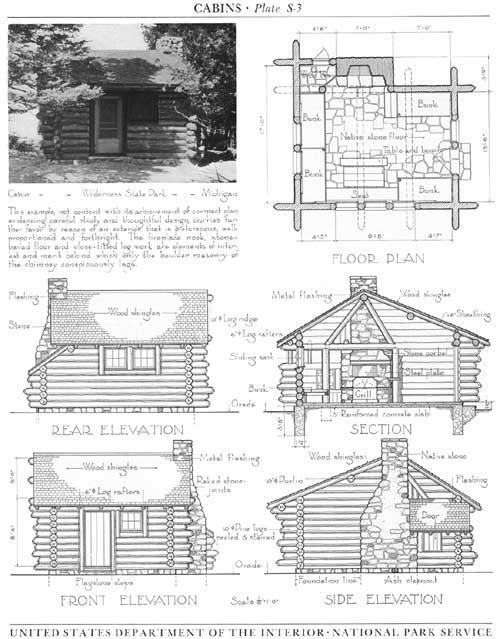

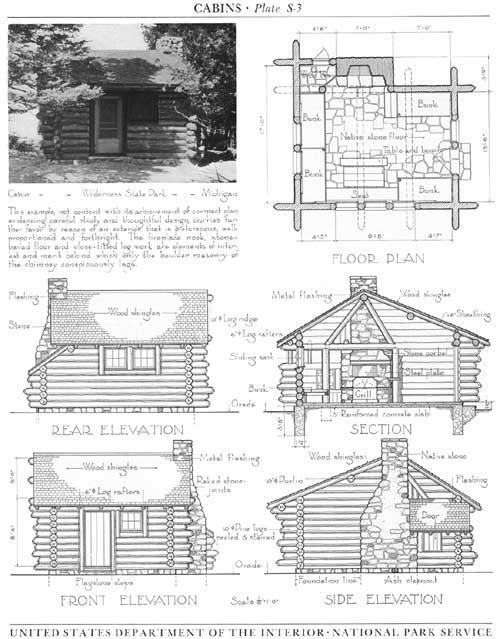

Plate S-3 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

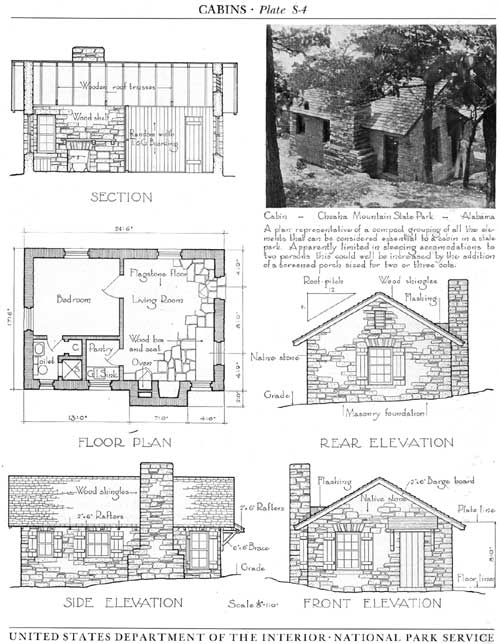

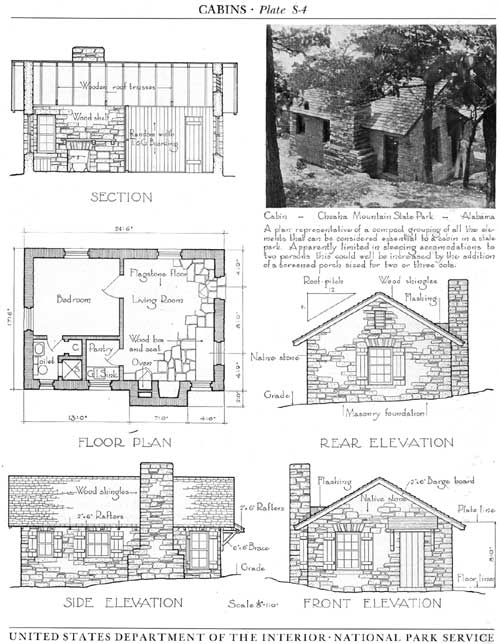

Plate S-4 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

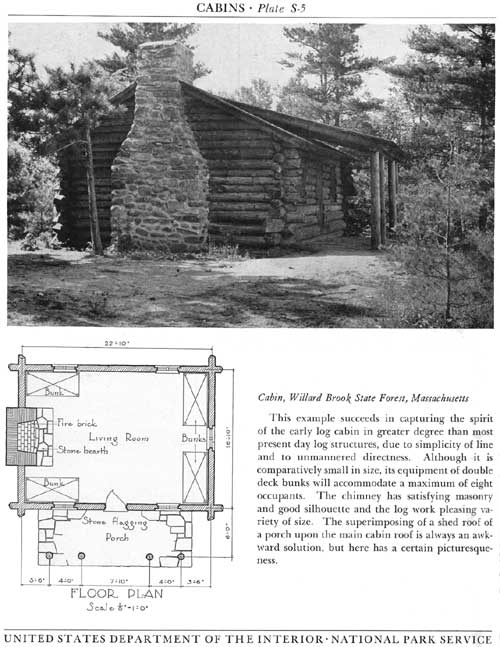

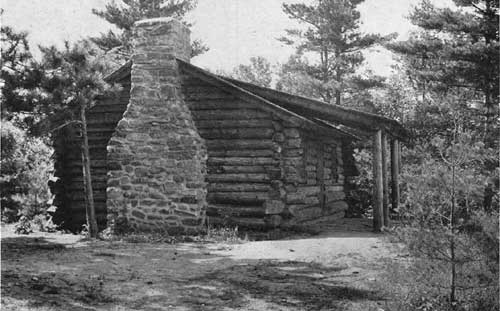

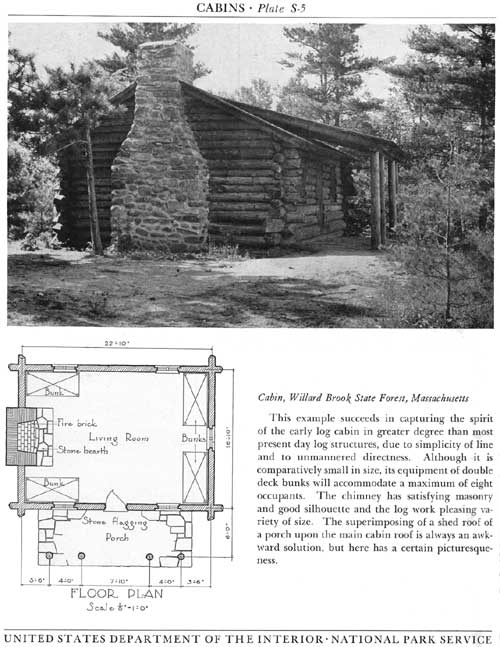

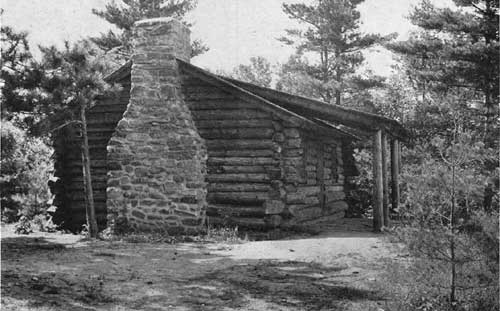

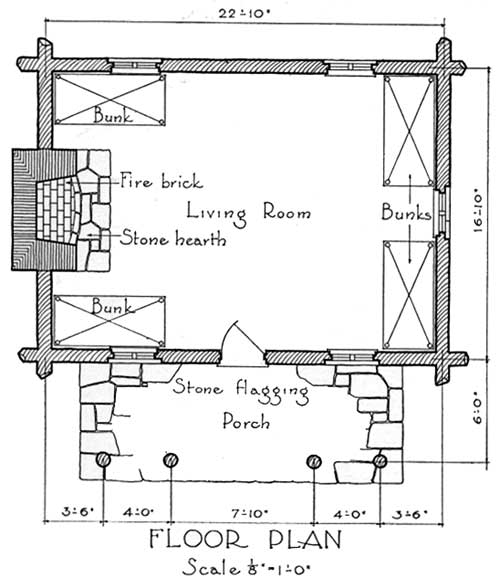

Cabin, Willard Brook State Forest, Massachusetts

This example succeeds in capturing the spirit of the

early log cabin in greater degree than most present day log structures,

due to simplicity of line and to unmannered directness. Although it is

comparatively small in size, its equipment of double deck bunks will

accommodate a maximum of eight occupants. The chimney has satisfying

masonry and good silhouette and the log work pleasing variety of size.

The superimposing of a shed roof of a porch upon the main cabin roof is

always an awkward solution, but here has a certain picturesqueness.

|

|

Plate S-5 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Willard Brook State Forest, Massachusetts

|

|

|

Willard Brook State Forest, Massachusetts

|

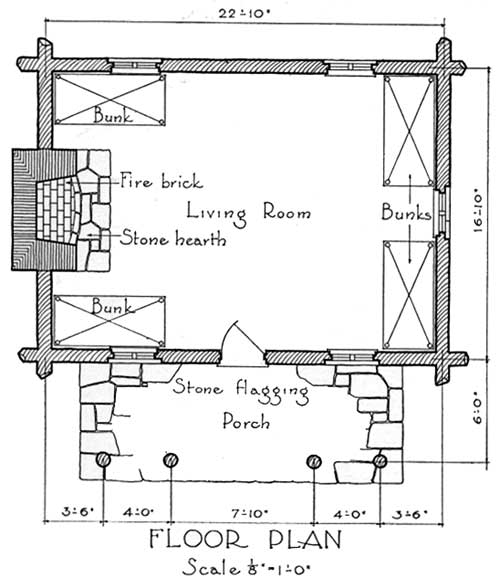

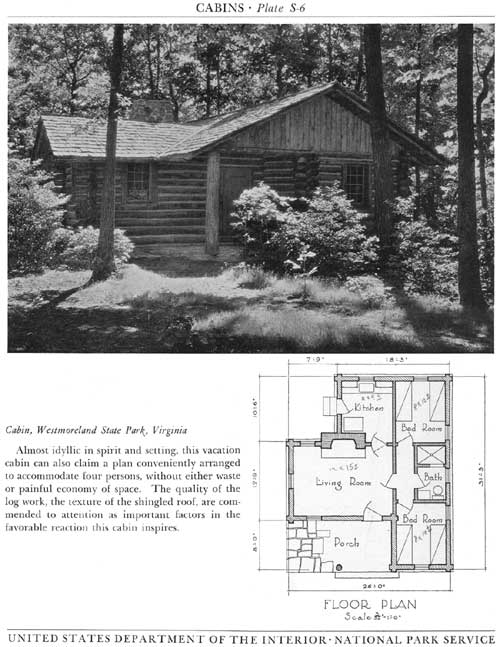

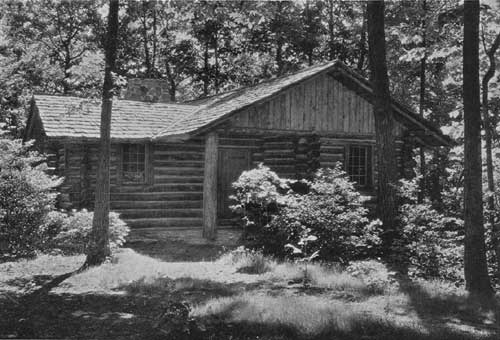

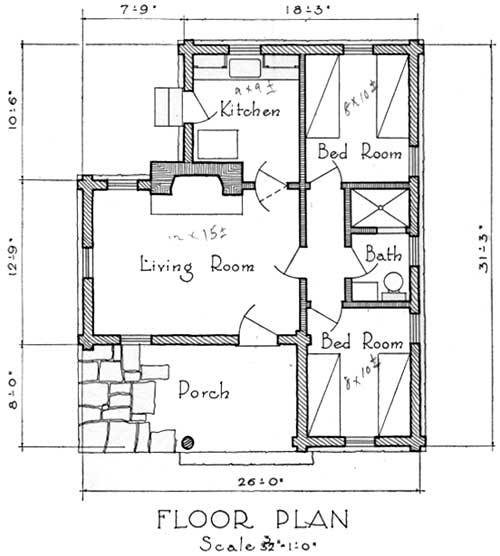

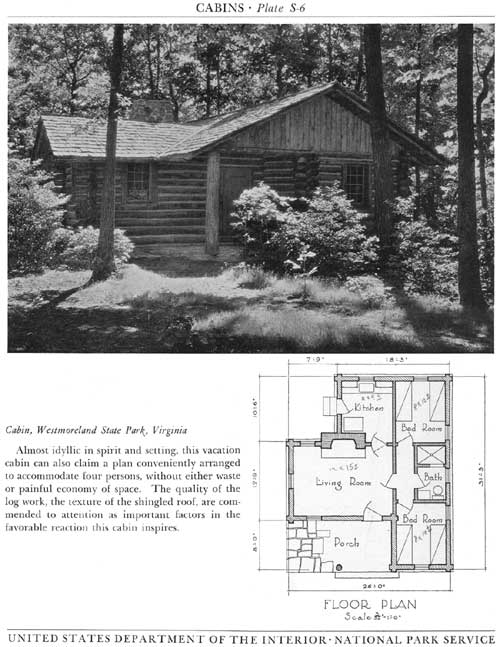

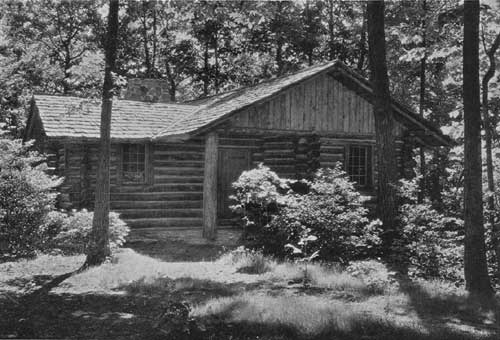

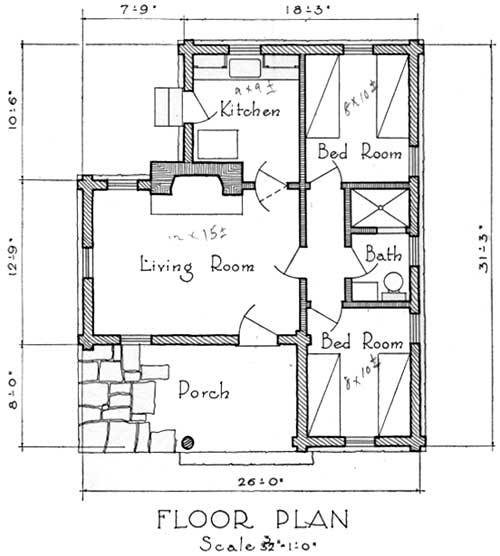

Cabin, Westmoreland State Park, Virginia

Almost idyllic in spirit and setting, this vacation

cabin can also claim a plan conveniently arranged to accommodate four

persons, without either waste or painful economy of space. The quality

of the log work, the texture of the shingled roof, are commended to

attention as important factors in the favorable reaction this cabin

inspires.

|

|

Plate S-6 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Westmoreland State Park, Virginia

|

|

|

Westmoreland State Park, Virginia

|

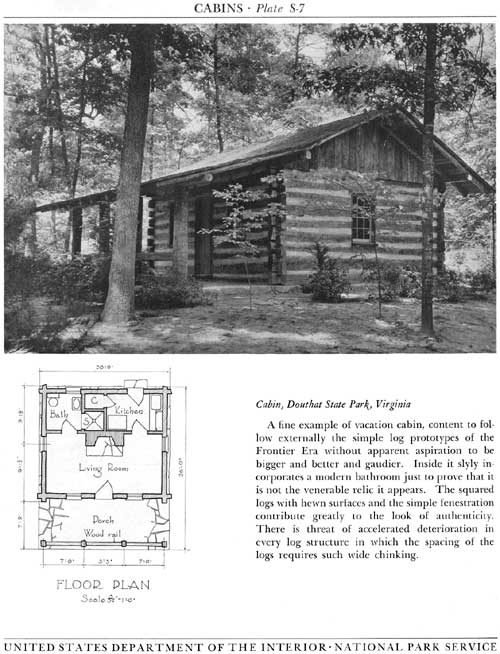

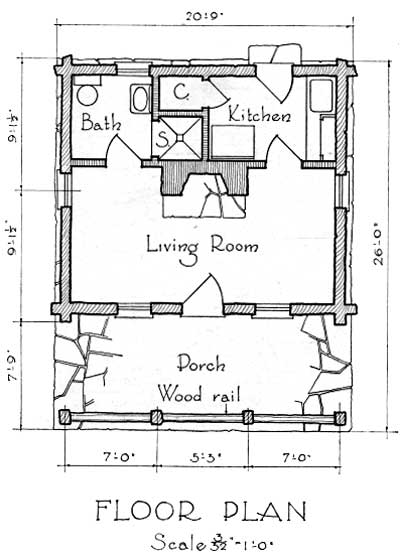

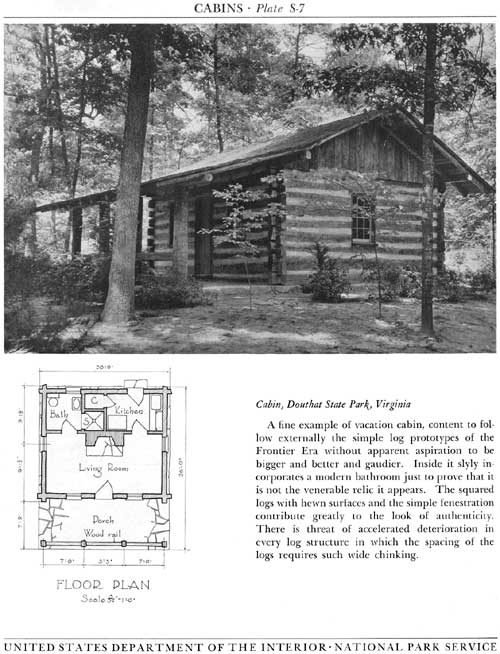

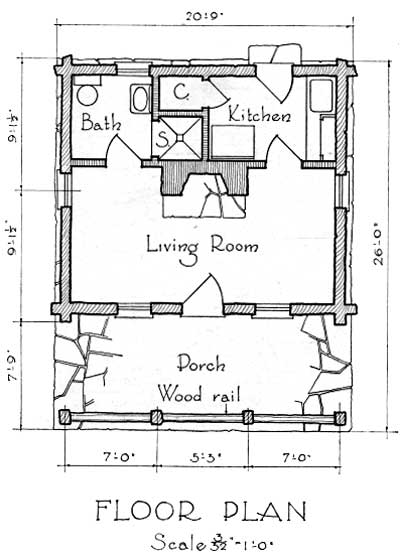

Cabin, Douthat State Park, Virginia

A fine example of vacation cabin, content to follow

externally the simple log prototypes of the Frontier Era without

apparent aspiration to be bigger and better and gaudier. Inside it slyly

incorporates a modern bathroom just to prove that it is not the

venerable relic it appears. The squared logs with hewn surfaces and the

simple fenestration contribute greatly to the look of authenticity.

There is threat of accelerated deterioration in every log structure in

which the spacing of the logs requires such wide chinking.

|

|

Plate S-7 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Douthat State Park, Virginia

|

|

|

Douthat State Park, Virginia

|

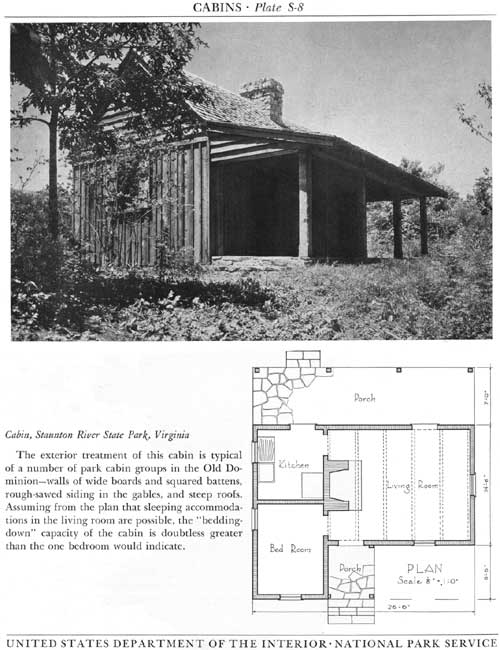

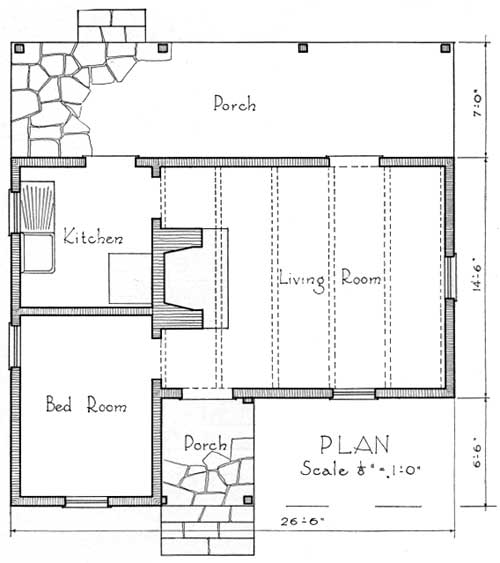

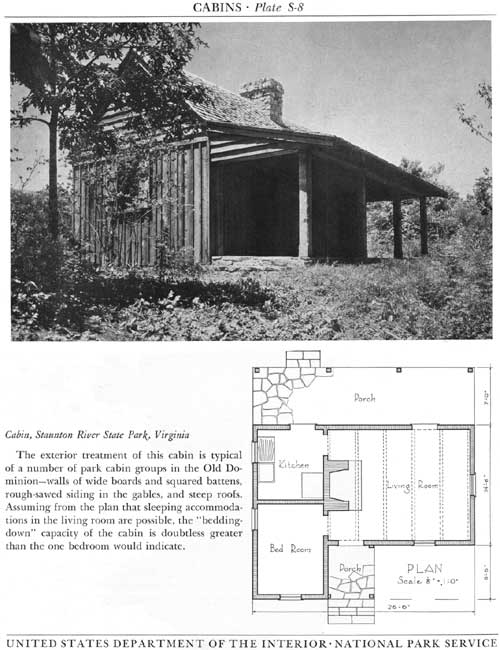

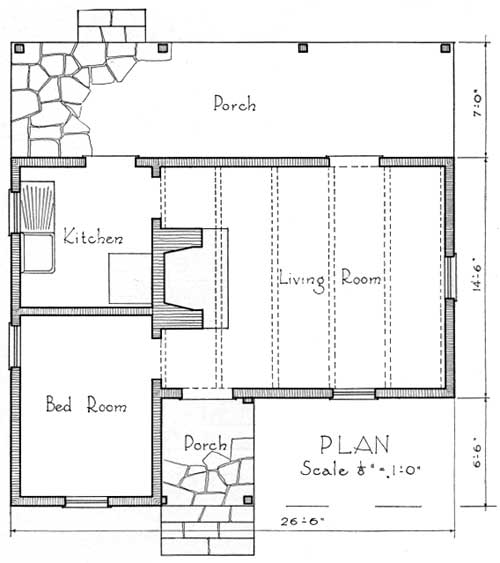

Cabin, Staunton River State Park, Virginia

The exterior treatment of this cabin is typical of a

number of park cabin groups in the Old Dominion—walls of wide

boards and squared battens, rough-sawed siding in the gables, and steep

roofs. Assuming from the plan that sleeping accommodations in the living

room are possible, the "bedding-down" capacity of the cabin is doubtless

greater than the one bedroom would indicate.

|

|

Plate S-8 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Staunton River State Park, Virginia

|

|

|

Staunton River State Park, Virginia

|

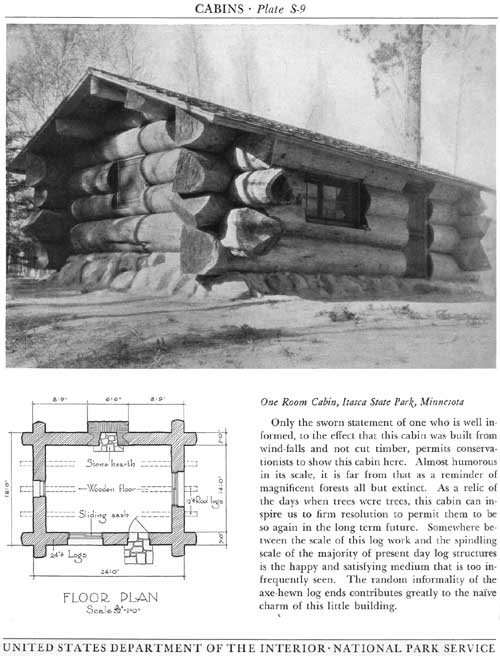

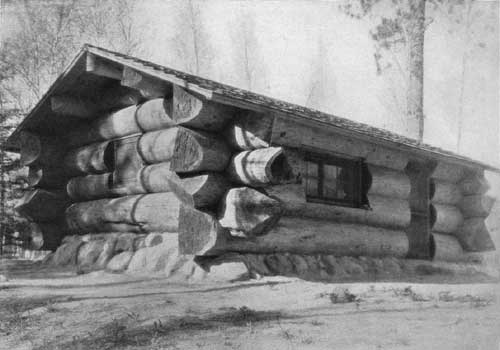

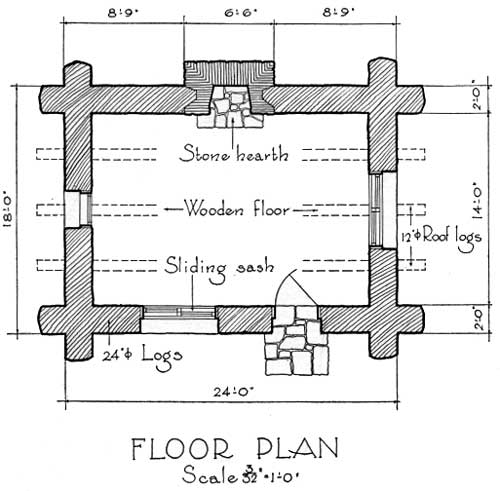

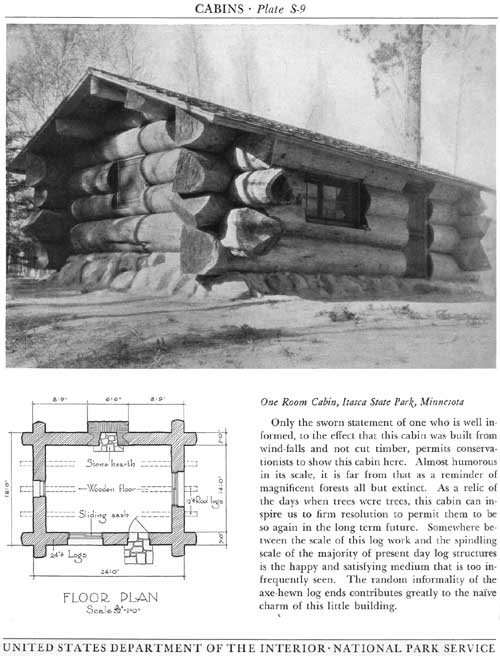

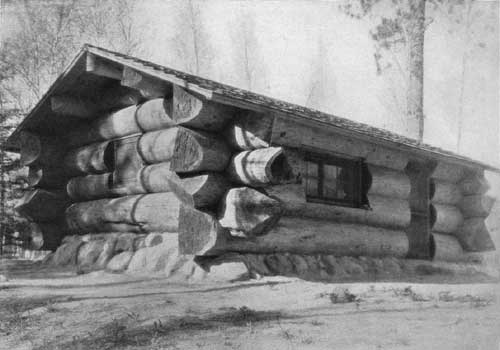

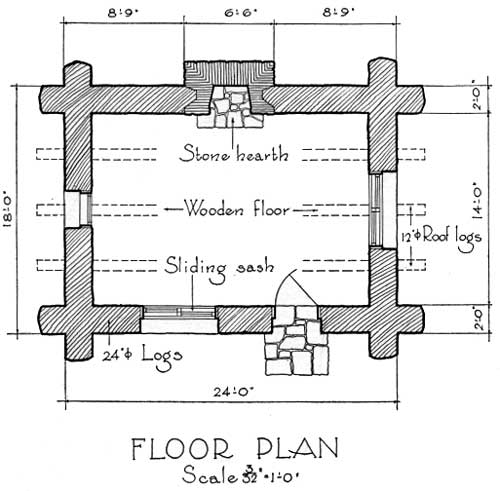

One Room Cabin, Itasca State Park, Minnesota

Only the sworn statement of one who is well informed,

to the effect that this cabin was built from wind-falls and not cut

timber, permits conservationists to show this cabin here. Almost

humorous in its scale, it is far from that as a reminder of magnificent

forests all but extinct. As a relic of the days when trees were trees,

this cabin can inspire us to firm resolution to permit them to be so

again in the long term future. Somewhere between the scale of this log

work and the spindling scale of the majority of present day log

structures is the happy and satisfying medium that is too infrequently

seen. The random informality of the axe-hewn log ends contributes

greatly to the naive charm of this little building.

|

|

Plate S-9 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Itasca State Park, Minnesota

|

|

|

Itasca State Park, Minnesota

|

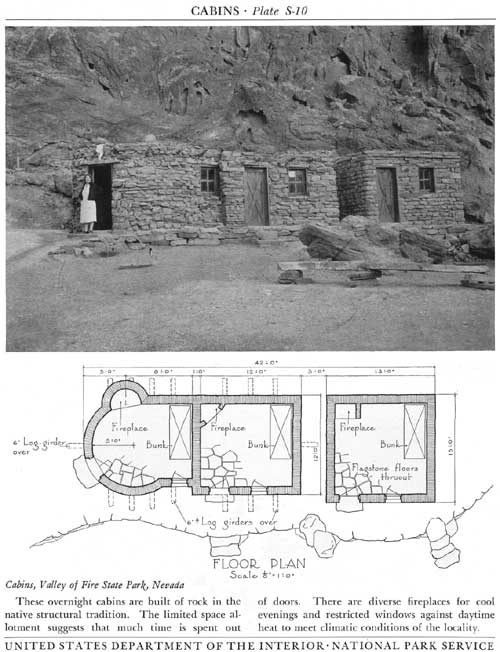

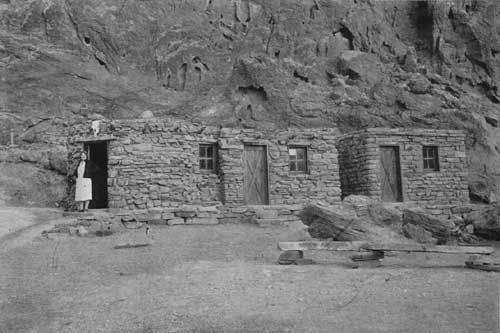

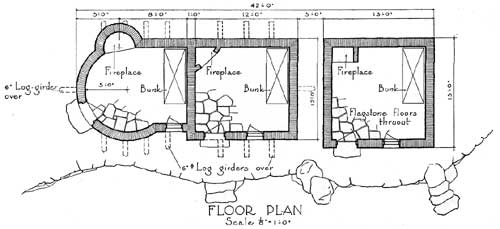

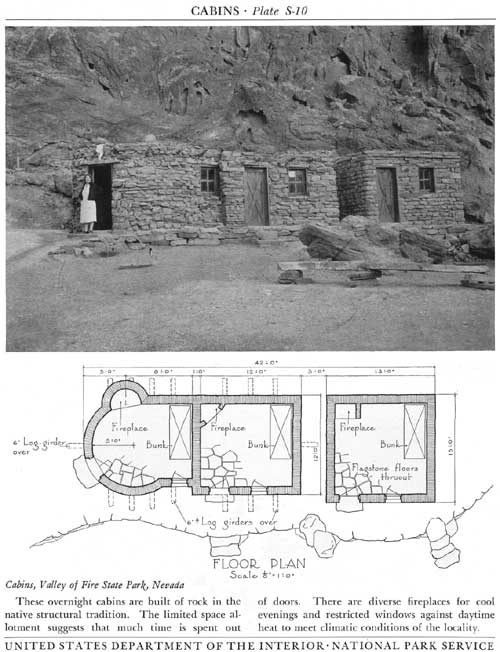

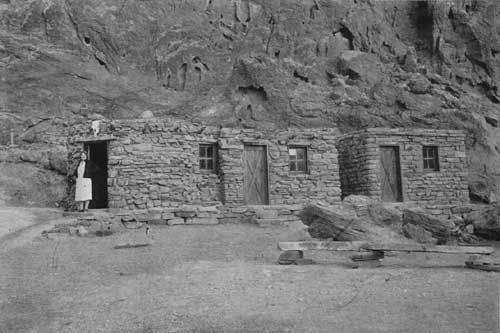

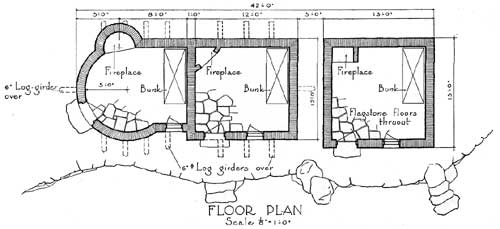

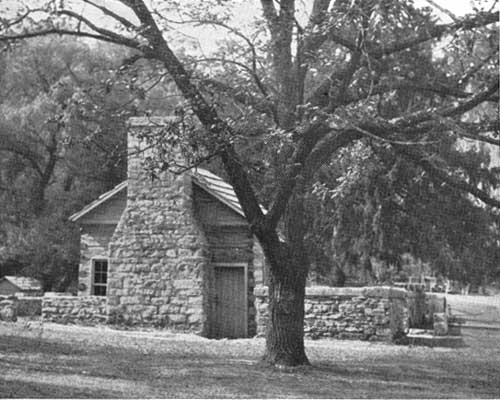

Cabins, Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada

These overnight cabins are built of rock in the

native structural tradition. The limited space allotment suggests that

much time is spent out of doors. There are diverse fireplaces for cool

evenings and restricted windows against daytime heat to meet climatic

conditions of the locality.

|

|

Plate S-10 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada

|

|

|

Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada

|

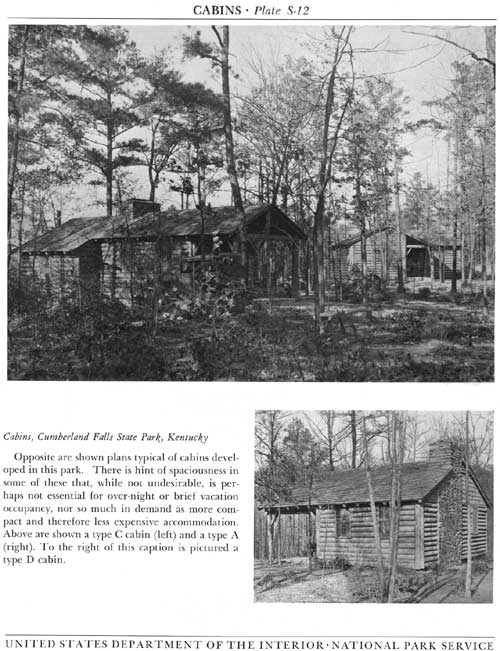

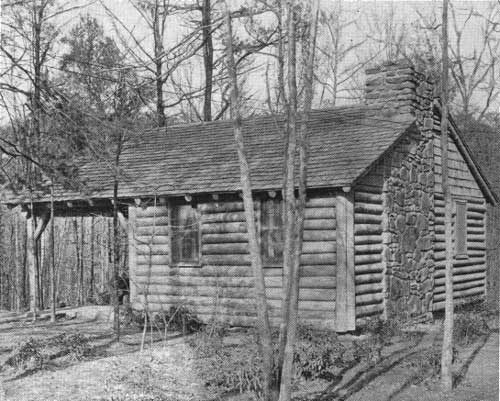

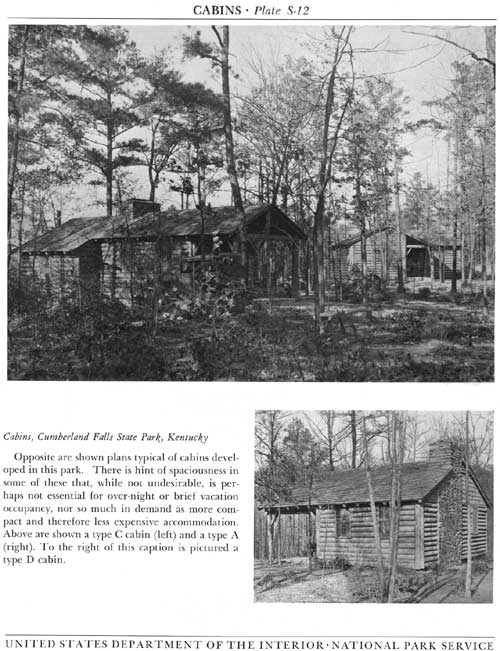

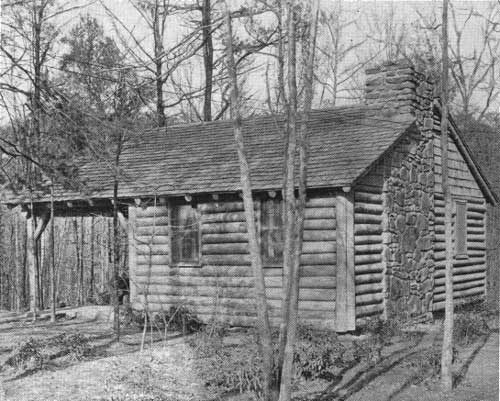

Cabins, Cumberland Falls State Park, Kentucky

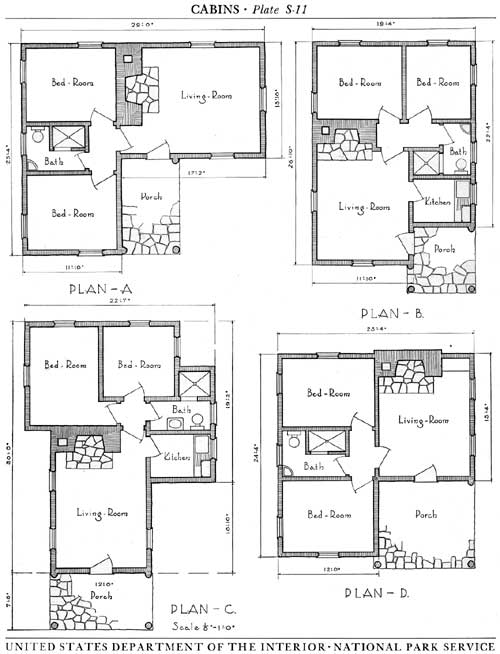

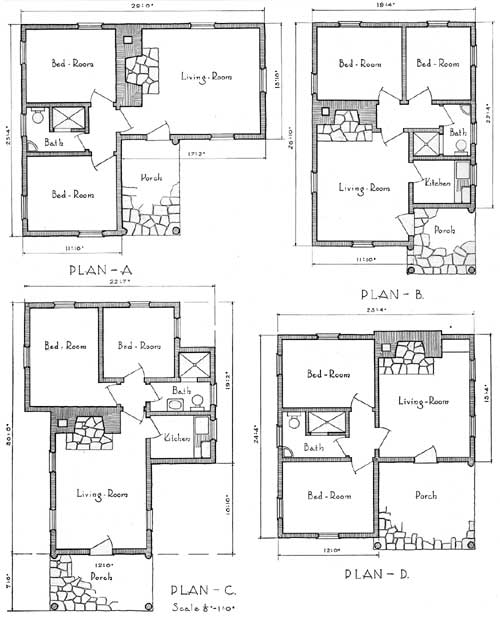

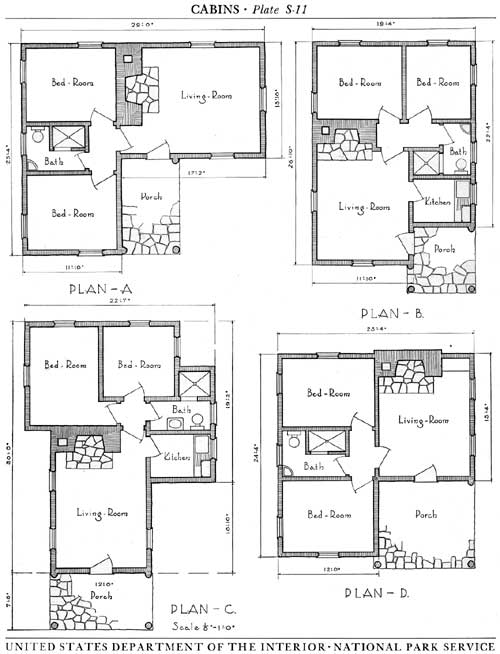

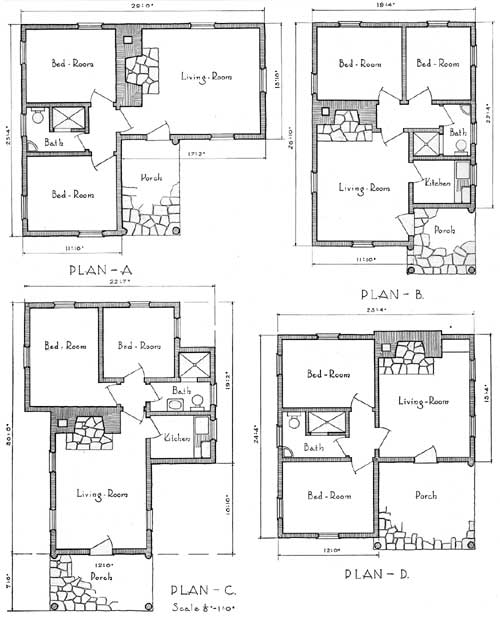

Opposite are shown plans typical of cabins developed

in this park. There is hint of spaciousness in some of these that, while

not undesirable, is perhaps not essential for over-night or brief

vacation occupancy, nor so much in demand as more compact and therefore

less expensive accommodation. Above are shown a type C cabin (left) and

a type A (right). To the right of this caption is pictured a type D

cabin.

|

|

Plate S-11 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Plate S-12 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Cumberland Falls State Park, Kentucky

|

|

|

Cumberland Falls State Park, Kentucky

|

|

|

Cumberland Falls State Park, Kentucky

|

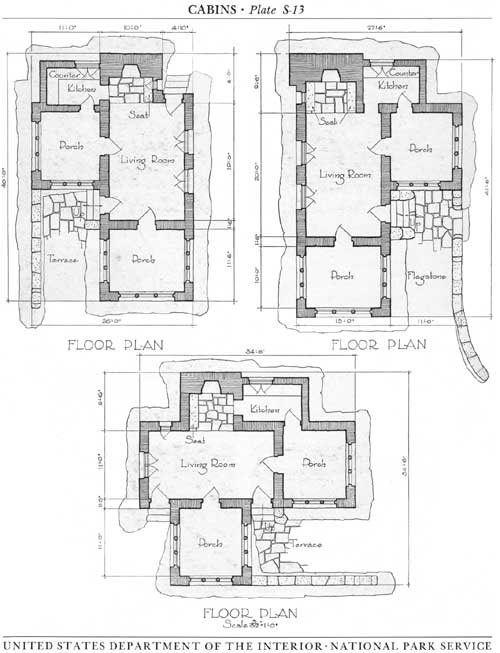

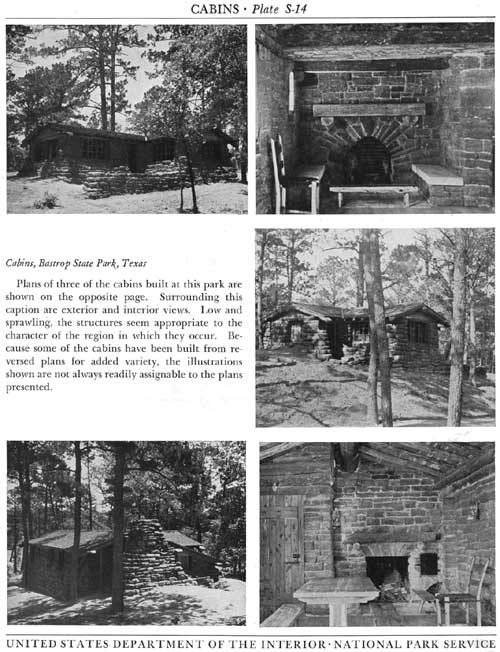

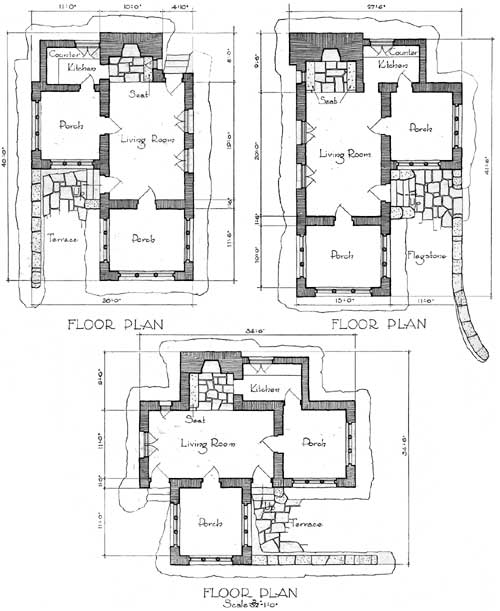

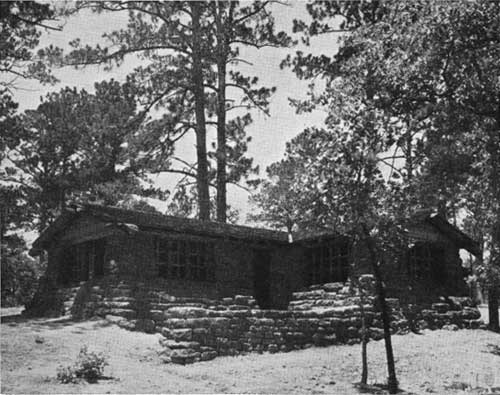

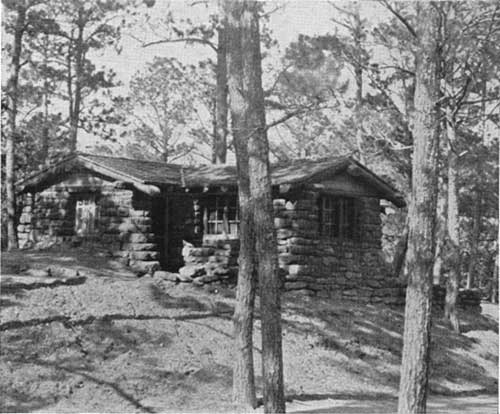

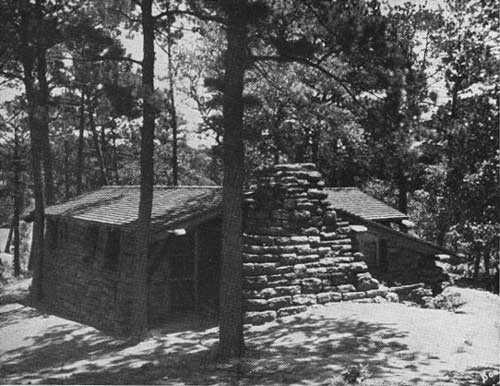

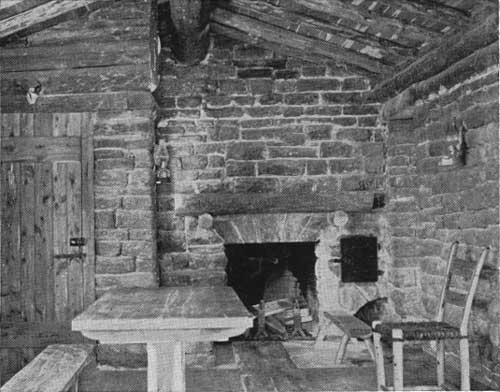

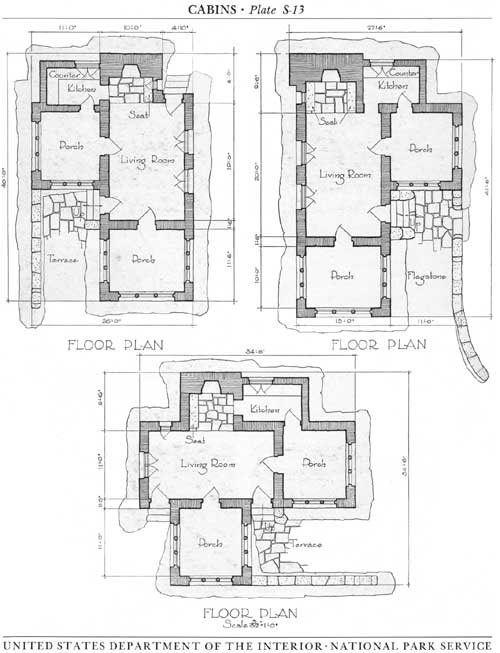

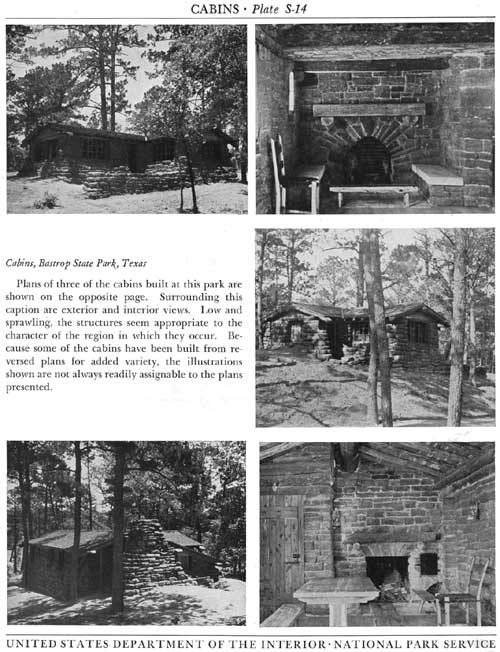

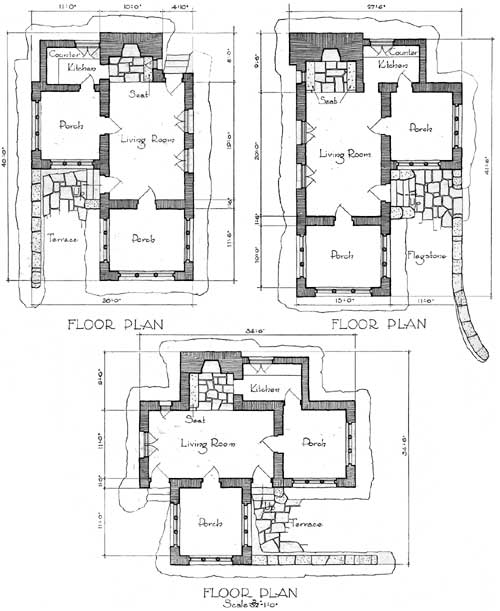

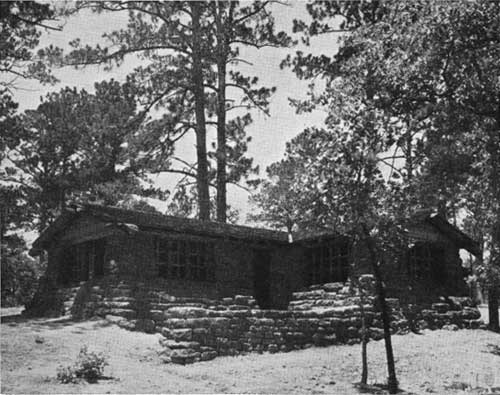

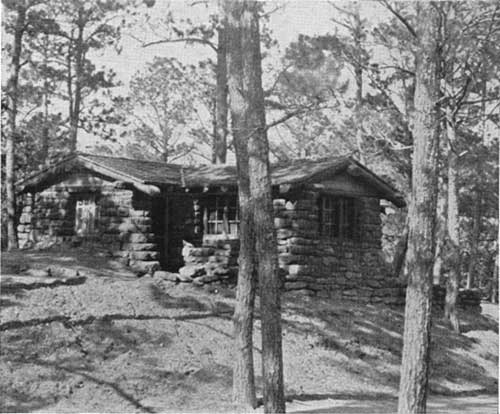

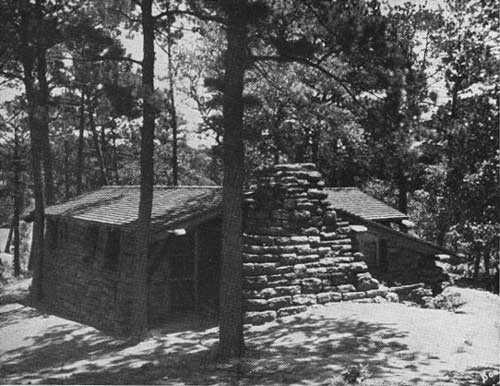

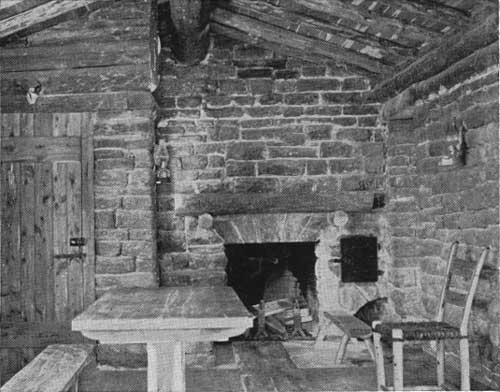

Cabins, Bastrop State Park, Texas

Plans of three of the cabins built at this park are

shown on the opposite page. Surrounding this caption are exterior and

interior views. Low and sprawling, the structures seem appropriate to

the character of the region in which they occur. Because some of the

cabins have been built from reversed plans for added variety, the

illustrations shown are not always readily assignable to the plans

presented.

|

|

Plate S-13 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Plate S-14 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Bastrop State Park, Texas

|

|

|

Bastrop State Park, Texas

|

|

|

Bastrop State Park, Texas

|

|

|

Bastrop State Park, Texas

|

|

|

Bastrop State Park, Texas

|

|

|

Bastrop State Park, Texas

|

|

|

Plate S-15 (click on image for a PDF version)

|

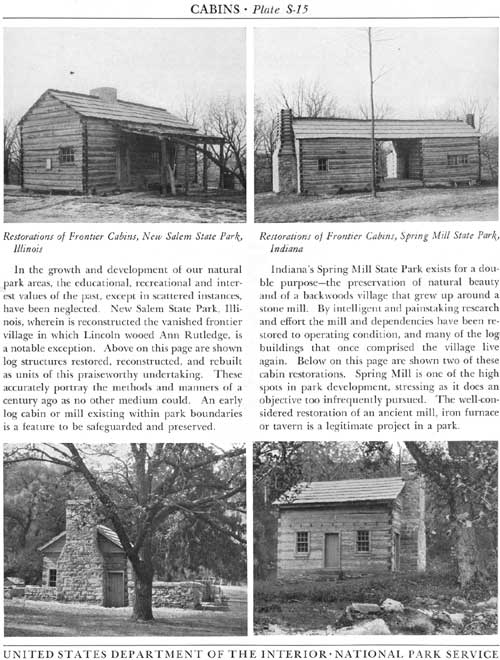

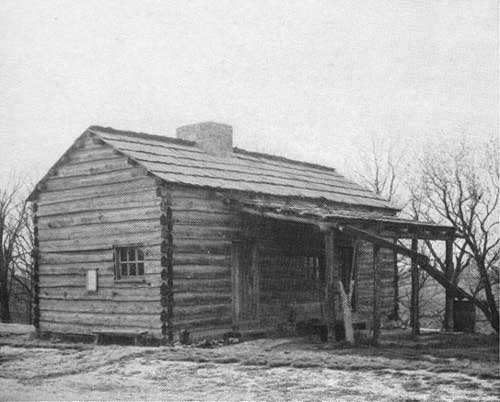

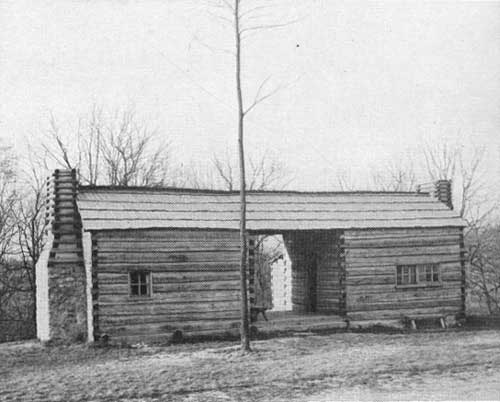

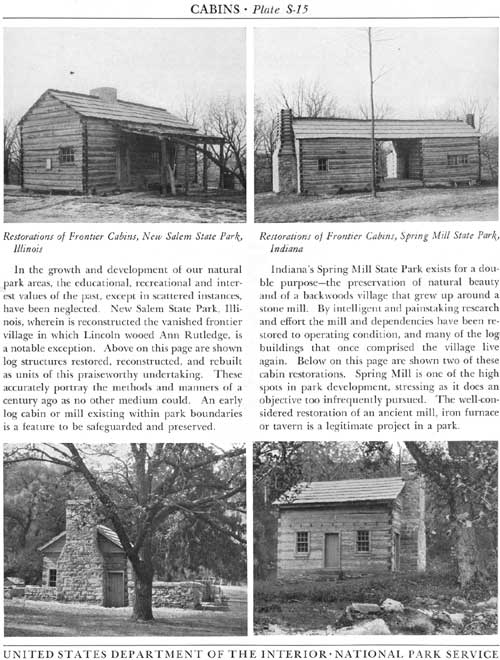

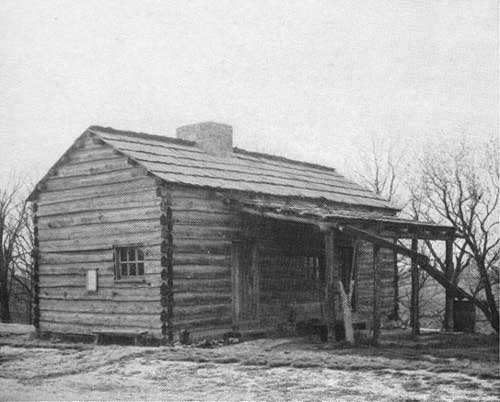

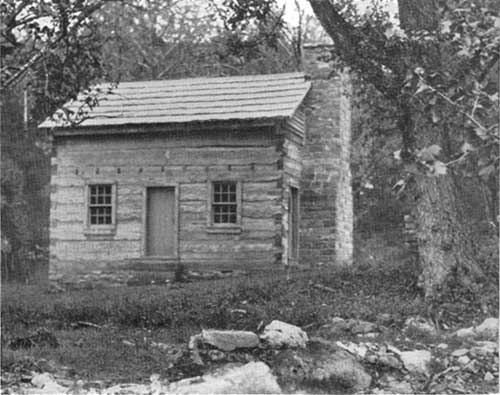

Restorations of Frontier Cabins, Spring Mill State Park, Illinois

In the growth and development of our natural park

areas, the educational, recreational and interest values of the past,

except in scattered instances, have been neglected. New Salem State

Park, Illinois, wherein is reconstructed the vanished frontier village

in which Lincoln wooed Ann Rutledge, is a notable exception. Above on

this page are shown log structures restored, reconstructed, and rebuilt

as units of this praiseworthy undertaking. These accurately portray the

methods and manners of a century ago as no other medium could. An early

log cabin or mill existing within park boundaries is a feature to be

safeguarded and preserved.

|

|

Spring Mill State Park, Illinois

|

|

|

Spring Mill State Park, Illinois

|

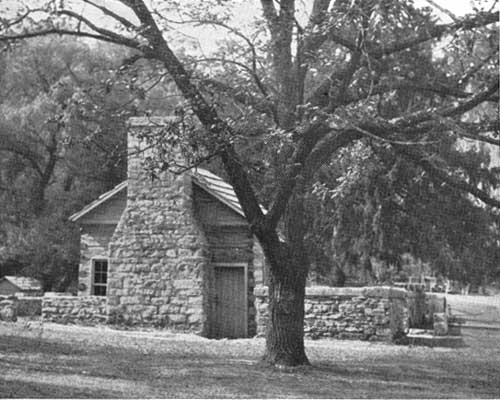

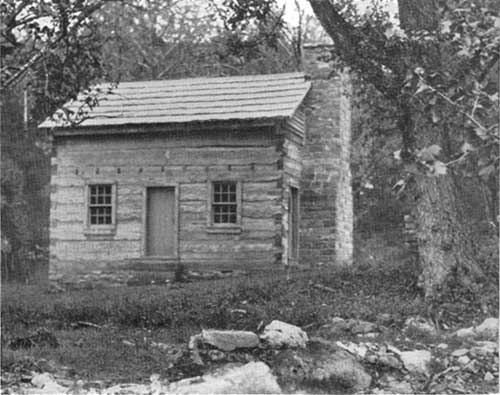

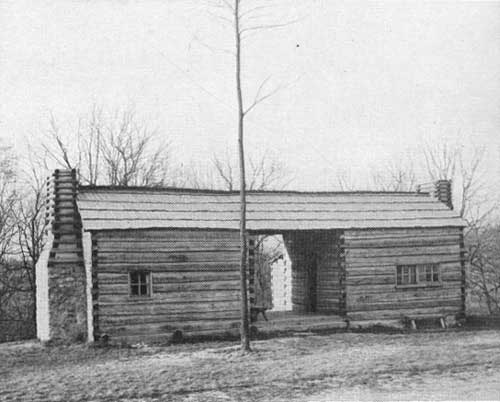

Restorations of Frontier Cabins, New Salem State Park, Indiana

Indiana's Spring Mill State Park exists for a double

purpose—the preservation of natural beauty and of a backwoods

village that grew up around a stone mill. By intelligent and painstaking

research and effort the mill and dependencies have been restored to

operating condition, and many of the log buildings that once comprised

the village live again. Below on this page are shown two of these cabin

restorations. Spring Mill is one of the high spots in park development,

stressing as it does an objective too infrequently pursued. The

well-considered restoration of an ancient mill, iron furnace or tavern

is a legitimate project in a park.

|

|

New Salem State Park, Indiana

|

|

|

New Salem State Park, Indiana

|

park_structures_facilities/secs.htm

Last Updated: 5-Dec-2011

|