|

Pipestone

A History of Pipestone National Monument Minnesota |

|

THE SETTLEMENT PERIOD

During 1870, public land surveys in the Pipestone area were completed, but no one paid attention to the long-standing instructions of the General Land Office, and the surveys overran the limits of the Pipestone Reservation.

Though the pace of settlement lagged a few years behind the surveyors, the first filings by land seekers of a speculative nature came soon after the surveys were made. The earliest known "homesteader" on reservation lands was Henry T. Davis. The next such filing was that of August Clausen in July 1871.

By July 1872 the General Land Office noted that the surveys had overrun the reservation limits and ordered the reservation to be resurveyed and the boundaries marked on public land plats. The new survey was completed in late July of that year. It was found that the reservation occupied part of sections 1 and 2, Township 106, Range 46 West, and a small strip of sections 35 and 36, Township 107, Range 46 West. It was also found that the reservation boundaries were not aligned parallel to public land survey directions, resulting in small portions of sections 1 and 2, Township 106, being outside the southern boundary of the reservation.

Another settler, Job Whitehead, filed a timber claim on a portion of the reservation in June 1874.

By late 1875, all of the filings on the reservation had been properly canceled, except that of Clausen. Under circumstances which later seemed highly questionable, a patent was issued to Clausen for the S.W. 1/4 of section 1, Township 106. He sold this patent soon thereafter to Congressman Averill in July 1874, and Averill resold it to Herbert M. Carpenter of Minneapolis on November 5, 1877.

More settlers came to the surrounding lands from 1876 to 1880. In 1876 the townsite of "Pipestone City" was platted, and by 1878 the village was a small but growing trading center. From 1858 until the arrival of settlers, nothing interfered with Yankton use of the quarries. By mid-1876, however, friction developed, and the Yankton agent passed on complaints of his Indians to Washington, but little action was taken.

|

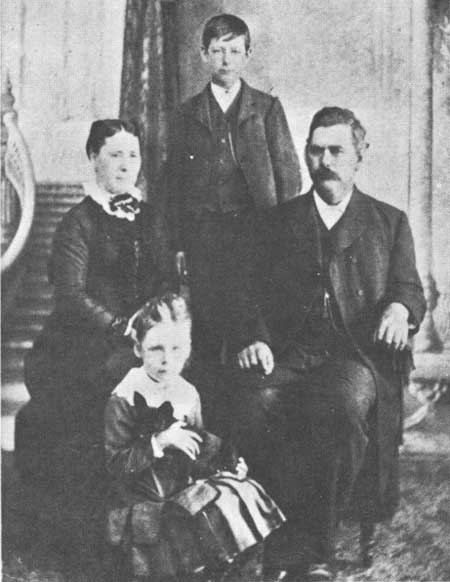

| Daniel E. Sweet and his family were the first settlers in Pipestone County. The little girl was the second white child born in the county. |

Not all the settlers were indifferent to Yankton rights. In the autumn of 1877, Daniel E. Sweet, early settler and prominent citizen, made the first of his many protests to the Government, requesting protection for Yankton quarrying rights.

The Yanktons, through their agent, formally complained of the intrusions in the area of the quarries in 1878. Extended discussions between the General Land Office and the Indian Bureau followed, and the issuance of the patent to Clausen came to light. In March 1879, Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz issued instructions to obtain the surrender of the Clausen patent. The document was traced to Carpenter, and a suit was filed to recover it. The case was heard in June 1880. Carpenter asked for a demurrer on the grounds that the Government owned the land, that Indian quarrying rights had not been interfered with, and that the Indians were not a party to the case. His contentions were upheld by the Circuit Court. The Government then appealed to the Supreme Court, but the case was not heard until 1884. In the meantime, the situation at Pipestone grew more complicated.

Late in 1880, a party of Yanktons returned from the quarries, and reported to their agent that white men were quarrying large amounts of stone on the reservation. The agent, Major Andrews, went to Pipestone to investigate on June 17, 1881. He found that Riley French, an agent for Carpenter, was opening a large quartzite building-stone quarry extending from the southern portion of the reservation across the section line to the south. Andrews was the first to voice suspicion that there had been collusion between Clausen, Carpenter, and unnamed persons in the Land Office in the issuance and transfer of the Clausen patent.

C. C. Goodnow, register and receiver of the Land Office at New Ulm, arrived in Pipestone early in 1882 to act as an agent for Carpenter, operating the quarry first noted by Major Andrews. Through this period the Yanktons continued to protest activities of this kind.

Lack of a firm policy or any vigorous action on the part of the Government encouraged more aggressive land seekers at Pipestone, and Goodnow, who was, by this time, mayor of Pipestone, was the first to move. In the spring of 1883, he built a two-story house, and fenced about 40 acres of land on the reservation. During the summer, he built another house nearby, this for his mother. In the autumn of that year, Hiram W. George built a small house near the west side of the reservation, and other Pipestone citizens quarreled over bits of land there.

Sweet wrote to Strike-the-Ree, Chief of the Yanktons, telling of these activities. An exchange of correspondence between them, the Yankton agent, and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs followed.

Early in November, the agent, Major Ridpath, visited Pipestone as instructed by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. He reported the settlement and building activities. He gave the settlers notice to remove, but they refused. None of them presented any evidence of title to the lands on which they were living. Ridpath said, "I can see no excuse for these parties, they are not ignorant of the law. I will take pleasure in removing them and in tearing down their buildings if you so direct."

The Commissioner of Indian Affairs favored Ridpath's suggestion, and submitted a detailed report to the Secretary of the Interior. At this time the Secretary was Henry M. Teller, a strong supporter of Western and settler viewpoints on Indian lands. Teller refused to support Ridpath's recommendations, and stated (1) that he did not believe the land constituted an Indian reservation, (2) that he believed the Yanktons had only quarrying rights there, and (3) that the settlers did not appear to have interfered with these rights. No further action was taken in the matter during the remainder of the Arthur Administration.

The Election of 1884, won by Grover Cleveland, brought many changes in personnel and policies concerned with Indian affairs. The new Secretary of the Interior, L. Q. C. Lamar; his Commissioner of Indian Affairs, J. D. C. Atkins; and the Attorney General, A. H. Garland, were all the more inclined toward just, realistic Indian land policies. So the renewed complaints of Sweet, Strike-the-Ree, and the new Yankton agent, J. F. Kinney, did not fall on deaf ears.

The hand of the Government was also strengthened by the decision of the Supreme Court in the Carpenter case in late 1884. The Court said:

The whole of such land was by treaty withdrawn from private entry or appropriation until the Government had determined whether any portion less than the whole should be reserved. Its power of selection, if the whole was not retained, could not be restricted by the action of private parties. So, in any view which can be taken, the entry of Clausen was void. It matters not whether the land had been surveyed or not, the treaty was notice that a part of the quarry would he retained by the government, and that the whole might be, for the use of the Indians. This purpose and stipulation of the United States could not be defeated by the action of any officers of the Land Department.

Complaints continued through late 1885. Additional persons had settled on the land, including W. W. Whitehead, F. A. Marvin, W. H. Hockabout, and G. W. Huntley. Beginning in December, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and his agent assembled a mounting collection of evidence. The Yanktons became more irate as time passed, and submitted a formal petition to the Commissioner in November 1886.

Action to remove the squatters got underway in earnest with the visit of Agent Kinney to Washington early in 1887. On his return, he reported that the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and the Secretary of the Interior favored such action and were prepared to back it up with force. The U. S. Attorney for Minnesota failed to take action to have the courts remove the settlers, so the agent was authorized to obtain assistance from the Army.

Written notices to remove were served on the settlers in March by the sheriff of Pipestone County, giving them until May 1 to leave. These notices were ignored.

A series of minor administrative details served to slow action, but at last, on October 8, 1887, orders were issued at Fort Randall, Dakota, to Capt. J. W. Bean to provide assistance to the agent. Captain Bean was instructed to meet the agent at Armour, Dakota Territory, with a detail of 10 enlisted men. Lt. W. N. Blow was to accompany the party as surveying officer.

The small force arrived at Pipestone on the evening of October 11, and camped in a field at the north edge of town. On the morning of October 12, Kinney and Captain Bean hired a vehicle and went to confer with the settlers. Finally, all agreed to move by the following Monday, October 17, and to remove their buildings by March 1, 1888.

While these discussions were taking place, Lieutenant Blow, assisted by the enlisted men, surveyed and re-marked the reservation boundaries.

Locally, the arrival of the troops caused quite a stir and some amusement as the long-standing resolve of this band of settlers melted when confronted by this small force of U. S. Regulars. The editor of the Pipestone Republican praised the conduct of Major Kinney, Captain Bean, and Lieutenant Blow, and noted their courteous performance of the duty assigned them. A considerable body of Yanktons was on hand to witness the removal, and was highly pleased by this action.

The local agricultural association and those Yanktons present negotiated an agreement by which the association could rent the fenced portions of the land for use as a fair grounds. This agreement was endorsed by the agent.

Kinney also reported the existence of a railway, which he found had been built across the reservation in 1884. He immediately contacted the company (Burlington, Cedar Rapids, and North Railway), which contended it had filed adequate notice to obtain right-of-way. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs notified the company that the general acts for rights-of-way did not apply on the reservation, and that Congress would have to solve this problem. A bill (H. R. 10766) was introduced in July 1888, but was not passed.

Congressman Lind of Minnesota introduced a more complex bill which did pass. It carried the title "An Act for the Disposition of the Agricultural Lands Embraced Within the Limits of the Pipestone Indian Reservation" (25 Stat. 1012). It provided (1) that a board of appraisers should evaluate all lands on the reservation, including the right-of-way; (2) that the former settlers might have priority to purchase lands from which they had been removed, if agreeable to the Indians; and (3) that the consent of a majority of the adult men of the tribe must be obtained and that the Indians might give their consent to the entire proposal or to either part individually.

|

| White men quarrying in area about 1889. (Courtesy, Minnesota State Historical Society.) |

In May 1889, the lands were appraised according to the provisions of the Act. The board gave an itemized appraisal of individual parcels of the reservation land, and set a value, including damages, of $1,740 for the railway land.

A commission was appointed to negotiate with the Yanktons. These discussions extended from August 3 through August 21. The Indians agreed to accept payment for the railway right-of-way, but refused to dispose of the other lands. By 1890, the railway company had paid the required amount. The General Land Office issued a patent to the company for only a part of the land in 1898, and the status of the balance is not yet clear.

With the settlement of the railway question to the satisfaction of the Yanktons in 1890, the problems connected with the settlement period came to an end.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

pipe/history/sec5.htm

Last Updated: 04-Feb-2005

Copyright © 1965 by the Pipestone Indian Shrine Association and may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the Pipestone Indian Shrine Association.