|

Pipe Spring

Cultures at a Crossroads An Administrative History of Pipe Spring National Monument |

|

PART I:

BACKGROUND

Location and Environment

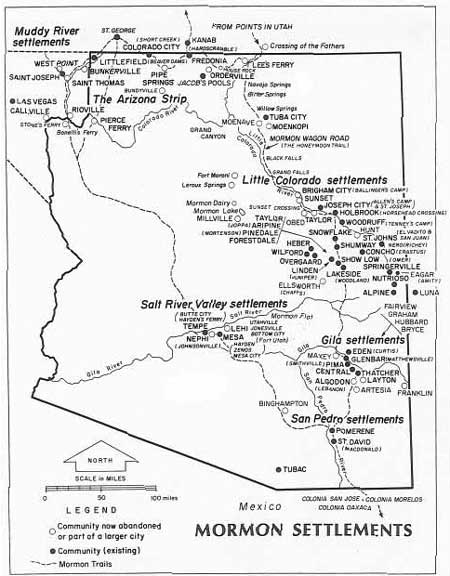

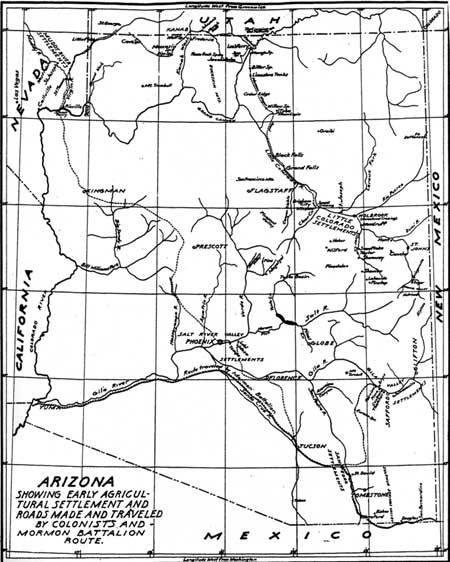

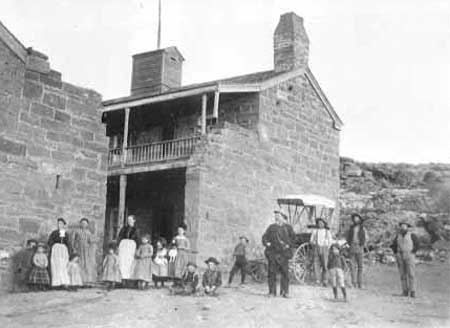

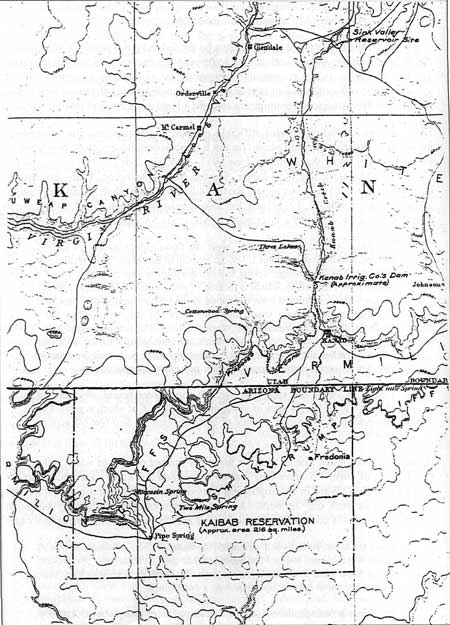

Pipe Spring National Monument is located on a 40-acre tract of land in Mohave County, in the northernmost part of central Arizona. The monument is eight miles south of Utah's southern boundary, 60 miles southeast of St. George, Utah, 20 miles southwest of Kanab, and 15 miles west of Fredonia, Arizona, on State Highway 389. The entire stretch of land between Utah's southern boundary and the Grand Canyon is known as the "Arizona Strip." This region has very strong historical and cultural ties with Utah among the immigrant "Mormons," a popular term for those with religious and/or cultural ties to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. [2] The Kaibab Paiute consider the larger area encompassing the southern half of Utah, northern Arizona, and portions of Nevada as traditional areas of prehistoric and historic use. Pipe Spring National Monument lies within the boundaries of the Kaibab Indian Reservation, established before the monument was created. [3]

Primary historic resources at the monument include three sandstone buildings (the Pipe Spring fort, east cabin, and west cabin), the historic-period sites of the Whitmore-McInytre dugout and a lime kiln, and other structures, including stone walls, the quarry trail, and the fort ponds. Reconstructed "historic" features include a vegetable garden, orchard, vineyard, telegraph line, and corrals. For the most part, modern developments are located at the southernmost part of the monument and include a residential area, maintenance area, and access road. This area is fairly well screened by plantings. There are three springs at the monument: the main spring (Pipe Spring), emerging from beneath the fort itself; tunnel spring (located just southwest of the fort); and cabin spring (a seep spring near the west cabin, once called the "calf pasture spring"). The springs are fed by the Navajo Sandstone aquifer to the north and west, via the Sevier Fault. Because there is more than one spring at the site, for many years it was referred to as "Pipe Springs," although the monument's official name was never plural.

The monument occupies the Moccasin Terrace of the Markagunt Plateau at the southern sloping base of the Vermilion Cliffs. From this site, a dry plain slopes southward for 40-50 miles before it descends dramatically into the Grand Canyon. The elevation of the monument is 5,000 feet, the climate is fairly temperate, and the plant and animal species are typically semi-desert. North of the monument is pinyon-juniper woodland. Intermingled with and at the edge of this woodland community is a sagebrush grassland with sagebrush dominant on the more level areas of ground and pinyon-juniper occurring on the shallow rocky soils and broken country of adjacent higher elevations. Other on-site vegetation includes rabbitbrush, prickly pear cactus, and sagebrush. Culturally introduced plant materials include a variety of shade trees (ash, cottonwood, poplar, elm, locust, ailanthus), fruit trees, a grape arbor, and a vegetable garden. Animal species include small rodents, reptiles, birds, coyotes, badgers, and porcupines. [4] High temperatures range in the summer from 90 to 115 degrees; in the winter, normal low temperatures range from 0 to 40 degrees.

|

|

1. Pipe Spring National Monument vicinity map; 1959, modified (Pipe Spring National Monument). |

Utah and the Arizona Strip: Ethnographic and Historical Background

Native American Occupation, pre-1776

"Pipe Spring" (as it was later named by Latter-day Saints), along with other springs in the immediate area, was used by indigenous peoples long before European or Euroamerican explorers and colonists discovered it. Prehistoric cultural resources appear in all portions of the monument and consist of ceramic and lithic scatters, charcoal deposits, and structural remains akin to what archeologists classify as the Virgin/Kayenta Anasazi (ca. A.D. 1100-1150). [5] These materials appear to be related to prehistoric structures in the area, including the large unexcavated pueblo of 22-40 rooms located immediately south of the monument, all of which are within the boundaries of the Kaibab Indian Reservation. Prehistoric petroglyphs are also found in and adjacent to the monument.

The arid region of southwestern Utah, southern Nevada, and northern Arizona was territory traditionally inhabited by the Southern Paiute by A.D. 1150. [6] Prior to the arrival of Europeans to North America, small bands of semisedentary people gathered the natural plants and hunted the fauna of this ecologically diverse region. Pine nuts were especially valued as a dietary staple. The Southern Paiute practiced small-scale horticulture, planting and irrigating crops of corn, beans, and squash near permanent water sources. Their lives depended on a wide range of seasonal resources in different ecozones. Considerable distances between these food sources demanded great mobility. Water was then, as now, a key resource available at only a few places, and these places governed band movement and territories. [7]

The Southern Paiute had contact and relations with other native peoples: the Hopi to the east, Ute to the north, Goshute to the northwest, Shoshone to the west, Mohave to the southeast, and Hualapai and Havasupai to the south, across the Colorado River. Today, most Southern Paiute believe they were the people, or were related to the people, that archaeologists refer to as the Virgin River Anasazi. (The Kaibab Paiute refer to these ancient people as the iinung wung.) Archaeologists, however, are not in agreement on this issue. Some believe the Southern Paiute came out of the Great Basin when the Virgin River Anazasi abandoned the area; others propose they were post-agricultural Anasazi using hunting and gathering strategies in response to recurring environmental crises. Existing evidence is insufficient to determine if the Southern Paiute pushed the Anasazi out of the area ca. A.D. 1100-1150 or joined with them to become a common people. [8]

The Kaibab Paiute are one of a number of distinct Southern Paiute bands that have inhabited the Arizona Strip. They believe the area to be their ancestral home, their mythology holding that the Kaibab Plateau was their place of origin. According to oral history accounts collected in 1932 by anthropologist Isabel T. Kelly, the southern boundary of Kaibab Paiute traditional territory extended from the junction of the Paria and Colorado rivers downstream until just beyond Kanab Creek Canyon. The western boundary extended northward crossing the Virgin River just east of Toquerville and ended at the Kolob Plateau. The northern boundary proceeded from that point to the Paria River, which formed the eastern boundary. A conservative estimate of their traditional territory is 4,824 square miles. [9] Events of the 18th and 19th centuries would irrevocably impact the extent of their territory and way of life, and pose a serious threat to their survival. The history of the Southern Paiute and in particular, the Kaibab Paiute, continues in the following sections.

Spanish and Euroamerican Exploration and Contact

The time period from 1776 to 1847 is marked by early Spanish and later Euroamerican contact with the Southern Paiute through their exploration and economic activities in the area. The 1776 expedition led by two Franciscan priests, Francisco A. Dominguez and Silvestre Velez de Escalante, through northern parts of the Southern Paiute territory provided the first historical references to the native peoples. The explorers were attempting to find a northern route that would connect Santa Fe with Monterey, California. [10] On the return to Santa Fe, the Spanish expedition crossed the Arizona Strip. [11] On the Pilar River (now called Ash Creek) near its junction with the Virgin River 25 miles below Zion Canyon, Escalante noted the Indians' cultivation of corn in irrigated fields located on small flats along the river bank, thus documenting Southern Paiute agricultural practices. While the expedition failed to accomplish its mission, it gained much knowledge of the Great Basin region. It was later followed by excursions into the region by fur trappers, including Jedediah Smith (1826) and William Wolfskill and Ewing Young (1830). The 1849 California gold rush brought large numbers of prospectors and others traveling through Southern Paiute territory.

Prior to the arrival of the Latter-day Saints in 1847, Southern Paiute bands were impacted by the slave trade, a topic discussed by Isabel T. Kelly and Catherine S. Fowler in their chapter on the Southern Paiute in Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 11, Great Basin. [12] By the early 17th century, Spanish colonies in what are now northern New Mexico and southern California had institutionalized slavery and other forms of servitude. [13] Ute and Navajo slave raiders preyed on Southern Paiute bands. Spanish expeditions and American trappers repeated this pattern. Women and children were the most sought after as captives. One Indian agent noted that prior to 1860, scarcely one-half of the Paiute children escaped slavery, and that a large majority of those that did were males. One history of Utah refers to the trade:

In historic times the Ute carried on an extensive slave traffic. Children were obtained by barter or by force from poorer bands of Paiutes and exchanged with the Navahos [sic] and Mexicans to the south for blankets and other articles. Certain Paiute bands were almost depopulated by this traffic. [14]

The Kaibab Paiute maintain a memory of these raids by the Ute and Navajo. Feelings of enmity harbored by the Kaibab Paiute toward these tribal groups is often explained today by reference to such past raiding activity. [15] Some documentation suggests that Southern Paiute bands responded to the threat of enslavement by retreating from heavily traveled areas, particularly the Old Spanish Trail that opened as a commercial route in the 1830s. (This 1,200 mile rugged path was charted to link the old established settlements in New Mexico with the fledgling Spanish colony of Los Angeles, California. The New Mexicans carried westward serapes, blankets, knives, guns, hardware items, and cloth bought in the Santa Fe trade. [16]) At the same time, the slave trade may have forced abandonment of ecologically favorable areas, inhibiting the expansion of horticultural activities among the Southern Paiute, while increasing their dependence on hunting and gathering as a way of life.

In their study, Kaibab Paiute History, The Early Years, anthropologists Richard W. Stoffle and Michael J. Evans calculated the pre-1492 population estimate for the Kaibab Paiute to be at least 5,500. By the mid-1800s, Stoffle and Evans estimated the Kaibab Paiute population to have declined to about 1,175. [17] Although Spain's colonizing activities never reached the Southern Paiute territory, Stoffle and Evans attribute Indian population decline to the effects of diseases (in particular, smallpox and measles) which the Spanish introduced into native populations in Mexico and the Southwest between 1520 and 1846.

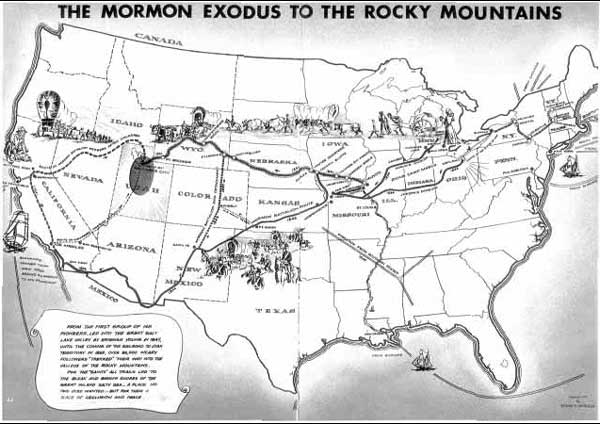

The Coming of the Saints and the Call to Dixie

Joseph Smith, Jr., born in Vermont on December 23, 1805, was the organizer and first president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. On June 27, 1844, Smith and his brother Hyrum were murdered by a mob at Carthage, Illinois. Brigham Young (also born in Vermont) succeeded Smith as Church president at the age of 34. Less than two years after the murders of the Smith brothers, Young and his group of followers left Nauvoo, Illinois, in February 1946, fleeing religious persecution. They headed for the Great Basin with the main party arriving at the Great Salt Lake Valley on July 24, 1847. [18] This region was then part of Mexico. With no official Mexican presence closer than Santa Fe and Tucson, many Latter-day Saints may have dreamed of establishing a new empire in the Great Salt Lake Valley.

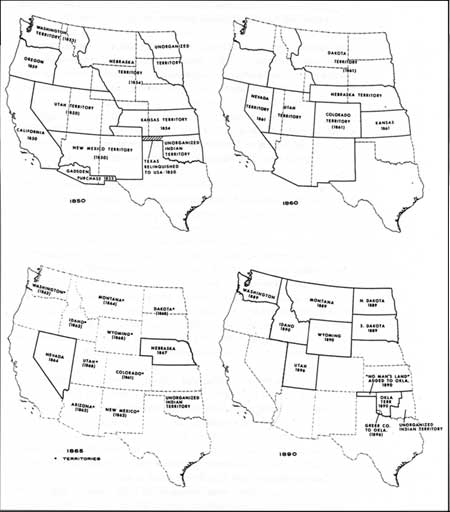

The United States declared war on Mexico on May 13, 1846. Its victory in the conflict and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed February 2, 1848, resulted in Mexico's relinquishment of all claims to Texas above the Rio Grande, an addition of 1.2 million square miles of territory to the United States. While this put an end to any hopes the Latter-day Saints may have had for an independent empire, they wrote a memorial to the U.S. Congress in December 1848 for creation of a territorial government. Without waiting for a response to the petition, the new immigrants undertook to create a provisional government for the "State of Deseret," electing Brigham Young, president of the Church, as their governor. On September 9, 1850, President Millard Fillmore signed a bill creating the Territory of Utah, renaming it after the Ute Indians. Young was retained as governor until 1857.

Not long after the arrival of Brigham Young and the Latter-day Saints to the Salt Lake Valley, parties of men were organized and sent out to explore other regions. [19] On November 23, 1849, one such party of 50 men set out under the leadership of Apostle Parley D. Pratt to explore southern Utah. By January 1850, Pratt's party had reconnoitered the country as far south as the mouth of the Santa Clara River, beyond the rim of the Great Basin.

|

|

2. "The Mormon Exodus to the Rocky Mountains" (Reprinted from Howells, The Mormon Story, A Pictorial Account of Mormonism, 1964). |

Kelly and Fowler report that slave raiding on the Southern Paiute ended soon after the arrival of the Latter-day Saints while noting that,

Initially the Mormons became unwilling participants in the trade, purchasing Indian children from the Utes who threatened to kill the children if the Mormons did not buy them. But active measures by Brigham Young and the territorial legislature ultimately ended the trade by the mid-1850s. [20]

While Mormon immigration to Salt Lake Valley went uncontested, resistance by native peoples began as soon as the colonizers headed south into the Utah Valley in 1849. The Walker War of 1853-1854 was precipitated by Mormon occupation of Ute lands. The war alerted the Church leaders that a more forceful Indian policy was needed. Five Indian missions were quickly dispatched between 1854 and 1856, all located on important trails within what were called the "outer cordon" colonies. [21]

Mormon settlers considered it their religious duty to influence the native peoples. They lived among Indians, baptized them, gave them Mormon names, and in a few cases married them. [22] By the end of 1858, only one mission survived, the Southern Indian Mission in southwestern Utah, where it served as a base for exploration, colonization, and Indian control. [23] Ironically, at the same time indigenous peoples in the Utah Territory were beginning to reel from the effects of Mormon colonization, the Latter-day Saints themselves felt their own way of life imperiled by the government of the United States. In 1856 President Brigham Young oversaw the formation of the Express and Carrying Company (also known as the Y.X. Company or the B.Y. Express Company). This business was the largest single venture undertaken to date by the Latter-day Saints in the Great Basin. It was designed to provide way stations for handcart companies and other immigration, to carry the United States mail between the Missouri Valley and Salt Lake City, and to facilitate the movement of passengers and freight between Utah and the East. In 1857 Anson Perry Winsor, an important figure in the history of Pipe Spring, was appointed to work for this company as wagon master. [24] Nearly all Mormon villages sent men to assist with the enterprise. The vast majority of them were called to work as missionaries. Their primary concern, of course, was the establishment of new settlements. [25]

On a trip to the Missouri River for Brigham Young's express company, Winsor arrived at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas Territory, on May 1, 1857. The year 1857 was marked by a serious political crisis in Utah, one that would hasten a movement of Latter-day Saints into the Arizona Strip and other areas far distant from Salt Lake City. The causes of this crisis and related events - known as the Utah War - are examined in detail in other Utah histories and will only be summarized here. [26]

In June 1857 President James Buchanan appointed a new governor for the Utah Territory. This move was designed to displace Church leaders with politicians closely tied to authority in Washington, D.C. An order directing troops to Utah was issued June 29, 1857, by the Commanding General of the Army and was justified as follows:

The community and, in part, the civil government of Utah Territory are in a state of substantial rebellion against the laws and authority of the United States. A new civil governor is about to be designated, and to be charged with the establishment and maintenance of law and order... [military action] is relied upon to insure the success of his mission. [27]

At the same time the new governor was appointed, the federal government cancelled all contracts with Brigham Young's Express and Carrying Company. Utah historian Leonard Arrington states that the activities of this company in carrying out the mail contract and in performing other economic chores for the Church figured prominently among the factors that led to the conflict with the federal government. [28] The desire of non-Mormons to impose national institutions and customs on Mormons (particularly with regard to the practice of polygamy) also played a role in the conflict.

The first of 2,500 federal troops left for Utah Territory from Fort Leavenworth under the command of Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston on July 18, 1857. The entire force committed to the expedition amounted to 5,606 men. "Express missionary" Winsor learned of the military action, known as the "Utah Expedition," while at Fort Leavenworth, and alerted Brigham Young of the impending advance of the U.S. Army. [29] Winsor sent a letter via Abraham O. Smoot who delivered the letter to Young on July 24, 1857, at Big Cottonwood Canyon, located near Brighton, Utah, about 20 miles southeast of Salt Lake City. [30] A reported 2,587 persons were gathered there that day to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Latter-day Saints' arrival in the Valley of the Great Salt Lake. [31] Thus Young had many months to take defensive action against the expected arrival of federal troops. The Utah Territorial Militia — consisting of about 3,000 men - was mustered into full-time service. While they were instructed to "take no life," the militia considerably slowed the advance of troops through implementation of a "scorched earth" policy, destroying resources ahead of the Army's advance. [32]

The advance of federal troops on Utah was considered a threat and Utah Mormons considered it continuing "gentile" persecution. [33] While the troops were still en route, a tragic event occurred in southern Utah. On September 11, 1857, Mormon militiamen killed over 100 men, women, and children who were part of a group of Missouri and Arkansas emigrants; the incident is known as the "Mountain Meadows massacre." While the massacre involved many individuals, John Doyle Lee was the only person brought to trial much later. An all-Mormon jury found him guilty and sentenced him to death, a sentence carried out on March 23, 1877. [34]

On September 15, 1857, Brigham Young declared martial law and proclaimed, "Citizens of Utah - We are invaded by a hostile force." Federal troops, in fact, were still en route. As he made preparations to defend the Kingdom, Young ordered Latter-day Saints in Idaho, Nevada, California, and other western states to abandon their settlements to "come home to Zion." The same directive was issued to missionaries scattered throughout the world, resulting in the return of several hundred. [35] Anson P. Winsor was later sent to Echo Canyon, east of Salt Lake City, in October 1857 to make fortifications and to guard the area against federal troops. In the spring of 1858, Winsor was called back to Echo Canyon with 300 men to relieve troops who had been on duty there the previous winter. Outright war was averted when negotiations held in February and March 1858 led to an agreement that Brigham Young would relinquish his governorship of the Utah Territory. Alfred Cumming, a federal appointee from Georgia who had served as Superintendent of Indian Affairs on the Upper Missouri, arrived to take over the territorial government on April 12, 1858.

The military actions of the federal government and its subsequent takeover of official government functions by "gentiles" reinforced the Latter-day Saints' long standing sense of injustice and oppression. [36] Just prior to Cumming's arrival, Brigham Young called a "Council of War" in Salt Lake City on March 18, 1858, where he announced his plan "to go into the desert and not war with the people [of the United States], but let them destroy themselves." Four days later, Young wrote, "We are now preparing to remove our men, women, and children to the deserts and mountains..." What followed has been called "The Move South." The events that follow chronicle this southern migration as it pertains to the Arizona Strip region near Pipe Spring.

Brigham Young instructed missionary and explorer Jacob Hamblin to learn something of the character and condition of the "Moquis" (whom we now refer to as the Hopi) and to preach to them. On October 28, 1858, Hamblin and a small party of men were sent southeast from the young southern Utah settlement of Santa Clara to contact the Hopi. [37] A Kaibab Paiute referred to as Chief Naraguts served as the party's guide through the region. Their other purpose was to determine if the Latter-day Saints could retreat to this region should the conflict with the U.S. Army become unbearable, to establish a mission among the Tribe, and to explore the region. [38] On October 30, 1858, the men encamped at Pipe Spring. Hamblin's party is the first documented visit by Euroamericans to Pipe Spring. Their explorations revealed the general topography between the Virgin and Colorado rivers to other Euroamericans, opening the way for later colonization of northwestern Arizona. The name "Pipe Spring" was in use by the time a second Hamblin mission to the Hopi passed by Pipe Spring on October 18, 1859.

Protected by the Utah Territorial Militia (also known as the Nauvoo Legion), Mormon expansion moved quickly, occupying the richest river valleys, reducing game, and pre-empting forage and water holes. Serious friction continued between Indians and settlers as whites penetrated other areas of Utah. [39] Between 1858 and 1868, 150 new towns were founded, and the 1850 Utah population of 11,000 grew to 86,000 by 1870. [40]

|

|

3. Erastus Snow, in charge of Arizona

colonization (Reprinted from McClintock, Mormon Settlement in Arizona, 1921). |

A move to relocate the Ute on the Uintah Reservation in the 1860s led to the Black Hawk Indian War of 1865-1868. [41] Initial fighting broke out between the Ute and the Latter-day Saints in 1865 in the Sevier Valley in central Utah. The war led the Church in 1867 to build Cove Creek Fort 200 miles south of Salt Lake City, located midway along the 60-mile stretch between Fillmore and Beaver. The fort's primary purpose was to protect the telegraph line that linked the area's settlements to Salt Lake City. [42] The Utah Territory's last major Indian conflict, the war forced the temporary abandonment of a number of southern settlements. Ute resistance was contagious, stirring some Southern Paiute into sporadic resistance. [43] However, no major confrontations took place between the Latter-day Saints and Southern Paiute. Some ascribe the non-combativeness of the Southern Paiute to activities of missionaries among them, most notably, Jacob Hamblin. [44] Perhaps, more likely, they simply lacked the numbers and resources with which to effectively stave off intruders, whether Euroamerican or Indian, such as the Ute and Navajo. [45]

The early 1860s mark the beginning of Mormon encroachment on Kaibab Paiute territory through the establishment of missions and permanent white settlements. At a semi-annual general conference of the Church held in October 1861, Brigham Young called 300 families to the Dixie Mission. [46] Utah's "Dixie" was in the Virgin River Basin, established to produce cotton, molasses, wine, and other warm-climate crops. On November 29, 1861, a group headed by George A. Smith and Erastus Snow left Salt Lake City to colonize the valleys of the Virgin and Santa Clara rivers. The town of St. George was surveyed and incorporated in 1861. Again on October 19, 1862, Young issued another call for 250 families to go south. Two other important events occurred earlier that year which would eventually spur colonization activity in southern Utah and northern Arizona, along with other western regions: passage of the Homestead Act on May 20, 1862, and President Abraham Lincoln's signing of the Pacific Railroad Act on July 1, 1862. The latter act authorized and provided financial aid for the nation's first transcontinental railroad. While the Civil War delayed its construction, the union of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads at Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 1869, ended the isolation of Brigham Young's Kingdom. Young organized a company to build a trunk line between Salt Lake City and Ogden, completed on January 10, 1870. The railroads provided a transportation corridor that linked Utah commercially to other states while ensuring a continuing stream of new immigrants. The Homestead Act, on the other hand, added an incentive to land-hungry settlers to take their families into arid lands that would have otherwise been considered desolate and unpromising by most folks back east. Not until 1869 did federal officials open a land office in the Utah Territory. Prior to that time, Church officers supervised settlement and land distribution, issuing land certificates to settlers in both Utah and the Arizona Strip. [47]

Other events had more immediate effects on settlements. Kit Carson's 1863-1864 bloody campaign against the Mescalero Apache and Navajo in the Territory of Arizona (which at that time included New Mexico) resulted in the infamous "Long Walk" during the winter of 1863-1864 and subsequent incarceration by April 1864 of about 9,000 Navajo and 400 Mescalero Apache at Fort Sumner in Bosque Redondo, New Mexico Territory. Many there suffered from disease, inadequate food rations, and crop failures. Before being released to return to their homelands in 1868, 1,000 Navajo died at Bosque Redondo. [48]

White settlers in Arizona and New Mexico hoped that the creation of reservations in the 1860s would solve the "Indian problem" and end their war with the Apache and Navajo. For Indians, of course, white immigrants and their protectors, the territorial militias, and the U.S. Army created the problem. Pockets of Indian resistance to white encroachment persisted for decades in some cases. [49] Displaced by years of conflict with the U.S. Army and refusing to go to their assigned reservation, some Navajo took refuge in Monument Valley and other remote locations while continuing to raid villages and livestock in southwestern Utah and along the Arizona Strip. [50]

Manuelito was the last of the Navajo war chiefs who held out against forced incarceration, hiding with a small band of about 100 men, women, and children along the Little Colorado. Finally, he and 23 defeated and emaciated warriors surrendered at Fort Wingate on September 1, 1866. [51] The free Navajo not only lived in fear of capture or death by U.S. Army soldiers, but also of Ute and Mexican slave raiders who still trafficked in stolen children. The choice between going to the reservation and remaining free was difficult, with either alternative posing considerable threats to survival. Some resistance leaders finally chose to surrender, concluding a treaty with U.S. government representatives led by General William Tecumseh Sherman at Bosque Redondo in May 1868. The 1868 treaty did not end hostilities along the Arizona Strip, however. Navajo raids continued to be a problem, particularly during the winters of 1867-1870. During the 1860s, the Latter-day Saints in Kanab Creek area permitted some Paiute Indians to have access to water and land for farming. In turn, these Paiute warned members of the fledgling white communities of impending raids by the Navajo, who were also the traditional enemy of the Paiute. [52] Since both Latter-day Saints and Paiute were vulnerable to the Navajo attacks, they served for a time as mutual allies.

In September 1870 Jacob Hamblin, accompanied by Major John Wesley Powell, concluded a peace treaty on behalf of the church with the Shivwits Paiute at Mt. Trumbull, on the north side of the Colorado River. (Powell was an explorer and geologist who convinced the Smithsonian Institute and Congress to fund two exploratory expeditions he led down the canyons of the Colorado and Green rivers during 1869 and 1871-1872. He conducted other explorations in Arizona and Utah in 1874 and 1875. Powell became director of the Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region in 1875, director of the Bureau of American Ethnology in 1879, and director of the U.S. Geological Survey in 1881. [53] ) Soon after, Hamblin and Powell embarked to Fort Defiance, New Mexico Territory, on a peace mission. At the time 6,000 Navajo were gathered there to receive their annual government allotments. Their meeting with the Tribal Council, begun on November 1, concluded on November 5 with a peaceful settlement. One source reports that Hamblin wrote Erastus Snow details of the meeting in a letter dated November 21, 1870. [54] Another source states that Hamblin returned to Kanab with word of the treaty about December 11, 1870. [55] The raids on white settlements soon ended, allowing the development of existing towns and the establishment of new ones.

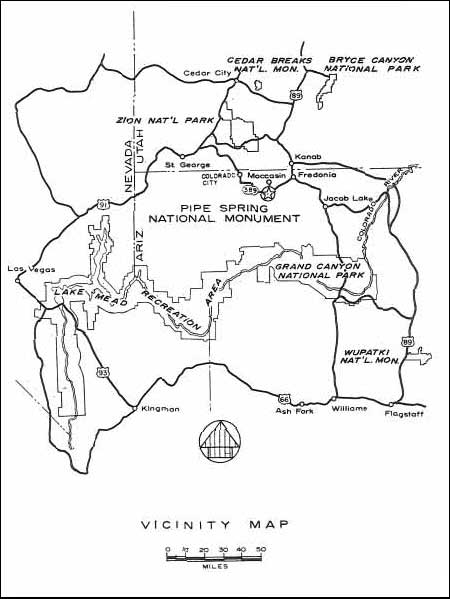

The Honeymoon Trail

Once peace was made with the Navajo, Latter-day Saints began colonizing along the Little Colorado River in Arizona. A ferry was established across the Colorado at the mouth of the Paria where both Jacob Hamblin and John Wesley Powell had found a feasible crossing. John D. Lee, in hiding for his role in the Mountain Meadows massacre, moved to this remote site with one of his wives, Emma, in December 1871. By January 1873, Lee offered regular ferry service to travelers seeking to cross the river and the place became known as "Lee's Ferry." Brigham Young issued a call that year for colonists to go to Arizona and fill the Little Colorado Mission. The missionaries - 109 men, 6 women, and 1 child - gathered at Pipe Spring, beginning the trek in 54 wagons. The wagon trail traveled nearly 200 miles, creating a rough road as it went. Historian C. Gregory Crampton describes their route to Lee's Ferry:

From the open valley of Kanab Creek the colonists wound along the ledgy, rocky western slope of the Kaibab Plateau. On top they had to traverse a thick forest of pinyon and juniper which snared animals and tore canvas. Then they jolted and bumped down the eastern slope of the Kaibab, which was steeper than the western slope. Through House Rock Valley and along the base of the Vermilion Cliffs they pulled through deep sand, headed washes and deep gulches, and finally arrived at the mouth of the Paria. [56]

Once they made the difficult crossing at Lee's Ferry, the first band of colonists had only a horse trail to follow along a steep and rugged rock crest known as "Lee's Backbone." Wagons had to follow switchbacks over a talus slope covered with sandstone blocks, then made their way southward along the base of the Echo Cliffs. Wagons continued into side canyons opening into Marble Canyon, through washes, barren hills, and across the Painted Desert until they reached Moenkopi, where they found spring water. Moenkopi was only 70 miles from Lee's Ferry, but the trek took the band 26 days, attesting to the ruggedness of the terrain. Proceeding on to the Little Colorado River, the settlers found a bleak and barren region with the riverbed nearly dry. Believing no settlement could be established in such a place, they headed back over the route just traversed.

Still, the road had been opened to the Little Colorado, soon to be traveled by a scouting party in 1875 and another mission of 200 men, organized in 1876. The settlers in this latter mission reached Sunset Crossing, near present-day Winslow, Arizona, in March 1876. Between 1876 and 1880, the Utah-Arizona road was in constant use as Latter-day Saints streamed into the Little Colorado region, establishing a foothold in northeastern Arizona. Beyond Lee's Ferry the route was known as the Mormon Wagon Road. By 1880 two other routes were used by Latter-day Saints traveling between Utah and the Little Colorado River settlements in Arizona, although neither was as heavily traveled as the Lee's Ferry route. [57]

|

|

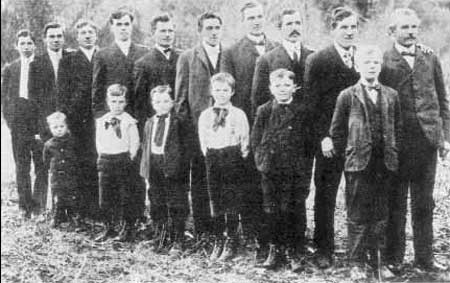

5. Map showing early settlement and roads in Arizona (Reprinted from McClintock, Mormon Settlement in Arizona, 1921). (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Once the St. George Temple was completed in 1877, young Mormon newlyweds, married by civil authorities in the Arizona settlements, traveled from the Little Colorado River settlements to St. George (by way of the Mormon Wagon Road and Lee's Ferry route) to have their vows solemnized in the temple. Generally, several wagons traveled together, providing both companionship and security in case problems were encountered along the primitive road. C. Gregory Crampton reports these treks were usually made in mid-November with the couples remaining in St. George for the winter, returning to the Little Colorado in April. [58] The route was traveled by so many newlyweds that it came to be known popularly as "The Honeymoon Trail."

Portions of the old road's well-worn trace can still be seen, including at the vicinity of Pipe Spring where late 19th century travelers would have naturally stopped for water. A portion of the Honeymoon Trail is shown on early 20th century area maps as the "Kaibab Wagon Road" as it passes through the Pipe Spring vicinity. Once Pipe Spring National Monument was established, a number of changes were made to the small section of historic road that traversed the 40-acre tract. In 1934 the road was relocated south of the fort ponds; it was abandoned altogether as a vehicular route, once State Highway 389 opened in 1967. While native vegetation now obscures much of the old road trace within the monument itself, it can be very easily discerned as one looks southwest far across the landscape from the fort. [59]

The Impact of Latter-day Saint Colonization on the Southern Paiute

Historian Leonard Arrington compared the early Latter-day Saints with this country's first colonists, the Puritans, whose religious dogma carried over into secular life. Arrington wrote,

[The Church's task] did not end with the conversion of individual souls. As the germ of the Kingdom of God, the church must gather God's people, settle them, organize them, and assist them in building an advanced social order. Ultimately, according to Mormon theology, the Church must usher in the literal and early Kingdom of God ('Zion') over which Christ would one day rule.... All individuals who participated in this divine and awesome task would be specially blessed and protected. One day, when the Kingdom was finally achieved, there would be no more wars or pestilence, no more poverty or contention. [60]

Brigham Young likened the process of teaching Indians the ways of white men and leading them toward Latter-day Saint conversion to the process of irrigation. Young stated, "[We must] cut channels" for water to run in "and gradually lead it where we want it to go.... Just so we must do with this people... by degrees we will control them." [61] With regard to contact between the white settlers and native peoples, Utah historian Charles S. Peterson observed:

Mormon relations with native Americans were at once an expression of faith and conquest. The Book of Mormon taught that Indians were a fallen people with whom God's spirit had ceased to contend but who were nevertheless united by blood and heritage to ancient Israel. In God's due time, the dark skin and 'loathsome' ways of the curse would be lifted and an inherited claim to the American continent be made valid. In the meantime the Saints watched closely for signs indicating that the curse was lifting and experimented with the means of redemption. [62]

Peterson refers to the strong cultural and religious overtones of Latter-day Saint colonization efforts: [63]

By the roads of the gathering the Mormons came to Utah. By colonization they distributed themselves and became a force in the West. By colonization they made a hostile land habitable and brought its discordant elements into a harmonious relationship with God's kingdom. Initiated in 1847, colonizing was repeated on successive frontiers during the next four decades. Responding in part to the Great Basin environment and in part to the teachings and experiences that made them a chosen people, Mormons developed their most distinctive institutions and practices in the process of colonizing. In other words, the climax of withdrawal from the larger society occurred not in arrival in Salt Lake City nor in the conflict that came to center there, but in the colonizing process - the call, the move, group control over land and water, and the farm village life. Developed to bring a raw environment into harmony with God's will on the one hand, and to protect the independence that its rawness permitted on the other, the practices of colonization proved impossible to perpetuate indefinitely, but until 1890 they distinguished Mormon culture and served as the vehicle of the church's geographic expansion. [64]

During the four decades of colonization that spanned from 1850 to 1890, Latter-day Saints established some 450 farm villages and towns. Even before the last watered lands in Utah were ferreted out during the 1870s and 1880s, the Saints extended their colonizing efforts to the neighboring states of Nevada, California, Idaho, Colorado, and Arizona. These settlements were a highly effective means of expanding the Church's area of the influence and economic power. By the 1890s, Latter-day Saint colonies were established as far as Canada and Mexico as a direct response to the U.S. government's crackdown on polygamists that began in 1885.

Several members of the Edwin D. Woolley, Jr., family recorded their recollections about Pipe Spring and the local Kaibab Paiute in the late 19th century. [65] Their observations included the following:

They are not a fighting tribe.... As a tribe they gave the white settlers little trouble. They seemed to have one need and that was food. They were always hungry. Their friendliness was the trusting friendliness of a child, and their pleasure and gratitude for kindness and a 'bees-kit' [biscuit] was of the same nature. We found them a most likeable people of many virtues, and fear never entered the relationships between the races when we were children. Indeed it seems that if they did not actually welcome the coming of the Mormons they were willing to settle for peaceful co-existence so long as the phrase meant Mormon food and clothing and a few of his utensils such as knives and guns.... Such an attitude on their part is understandable when the conditions of their life are appreciated. The lot of this handful of human beings was not a happy one even in good seasons but in bad seasons when nature forgot to send the rain life was cruelly hard. [66]

The narrative described the manner in which "wick-i-ups" were made by the Paiute, the use of various plants (particularly the squawbush), and various aspects of their material culture. "Clothing was scanty beyond belief," consisting of an apron made of strips of coyote and rabbit hide. Robes of rabbit skin were worn in winter. The pine nut "could be called the staff of life of these people... It became their first article of commerce when the white man invaded their land." [67] While the writer expressed admiration for the ability of the Paiute to survive in a harsh environment, it was obvious these Indians were viewed as extremely "lowly" in terms of cultural and social development. [68] This "backwardness" he attributed to the rigors of their way of life.

"They were always hungry." Some would argue that they had not always been hungry but that the deprivation witnessed by the Woolleys and their Latter-day Saint neighbors just prior to the turn of the century was caused by the indigenous people's loss of access to important resources. The impacts on native flora and fauna that accompanied Mormon settlement along Kanab Creek and other nearby locations, such as Short Creek, Pipe Spring, and Moccasin Spring, were disastrous, resulting in the loss to the Kaibab Paiute of their traditional means of subsistence. This in turn led to a rapid decline in population. [69] Stoffle and Evans cite starvation, rather than war or disease, as the primary cause of Indian deaths during the decade following the first arrival of Mormon settlers. From an estimated pre-contact population of 1,175, the Kaibab Paiute were reduced to 207 by 1873, representing an 82 percent decline in their numbers. [70] Although relations stabilized between Latter-day Saints and the Kaibab Paiute during the following three decades, the Indians found themselves in a desperate plight.

The immediate effects of colonization were apparent early on. Angus M. Woodbury, born in 1886 in St. George, Utah, of Latter-day Saint immigrant parents, wrote in A History of Southern Utah and its National Parks:

The coming of the Mormon pioneers gradually upset the Paiute government. The whites frequently settled on Indian campsites and occupied Indian farming lands. Their domestic livestock ate the grass that formerly supplied the Indians with seed, and crowded out deer and other game upon which they largely subsisted. This interference with their movements and the reduction in the food supply tended eventually to bring the Indians into partial dependence upon the whites.

Within a few years, farm crops and livestock brought the whites more food and clothing than the Indians had ever dreamed of. No wonder they became beggars in the towns and thieves of cattle and horses on the range. As long as the whites were in the minority, they used to feed the Indians.... As the whites increased and became strong enough to defy the Indians, the attitude changed from one of fear to that of domination.... In time, it became increasingly difficult for the Indians to maintain themselves. [71]

The Latter-day Saint's religion and charity proved to be woefully insufficient compensation for the Kaibab Paiute loss of traditional lands and other resources essential to their way of life.

In the 1860s, the federal government began establishing agencies (reservations) for Utah's native population. The Uintah Ute were attached to an Indian agency established in northeastern Utah in 1868. In an 1873 special commission report, John W. Powell and G. W. Ingalls recommended that the Kaibab Paiute also be placed under federal jurisdiction so that they might at least have food to eat and accessible farmland. No action was taken. In 1880 Jacob Hamblin wrote Powell, then director of the Smithsonian Institution's Bureau of Ethnology,

The Kanab or Kaibab Indians are in very destitute circumstances; fertile places are now being occupied by the white population, thus cutting off all their means of subsistence except game, which you are aware is limited. They claim that you gave them some encouragement in regard to assisting them eak [sic] out an existence....

The foothills that yielded hundreds of acres of sunflowers which produced quantities of rich seed, the grass also that grew so luxuriantly when you were here, the seed of which was gathered with little labor, and many other plants that produced food for the natives is all eat out [sic] by stock.

As cold winter is now approaching and seeing them gathering around their campfires, and hearing them talk over their suffering, I felt that it is no more than humanity requires of me to communicate this to you.... I should esteem it a great favor if you could secure some surplus merchandise for the immediate relief of their utter destitution. [72]

President Ulysses S. Grant issued the order establishing a reservation in 1872 on the Upper Muddy River in Nevada. Few but the Moapa Paiute went there. Powell responded with the recommendation that the Kaibab Paiute, now consisting of about 40 families according to Hamblin, move to the Uintah or the Muddy Valley reservations, so that they might obtain federal assistance. It is hardly surprising that the Kaibab Paiute shunned resettlement at the Uintah Reservation, given the history of Ute slave raiding among them. In the late 1880s, a federal appropriation was obtained to remove the Shivwits Paiute from their land on the Arizona Strip to a reservation on the Santa Clara River, just west of St. George. No evidence indicates that any Kaibab Paiute were able or willing to relocate to these reservations, choosing to remain instead on their traditional lands. As native subsistence became increasingly precarious, many Kaibab Paiute moved into closer proximity to the Latter-day Saint settlements of Kanab, Fredonia, and Moccasin, while others sought out wilderness refuge away from Euroamerican settlements, such as Kanab Creek Canyon.

Stoffle and Evans point out that the situation the Kaibab Paiute found themselves in was, in a number of ways, atypical of the post-conquest experience of most other native peoples in the region:

Unlike most other Native Americans, the Kaibab Paiutes did not during these years (1) have a treaty agreement with the United States government, (2) have any territory officially recognized as a reservation, or (3) receive regular welfare subsidies from either the Mormon Church or the federal government. It was a time of hunger, disease, and rapid cultural change for the Kaibab Paiutes. Yet they were ignored by the peoples and institutions that had set these processes in motion. [73]

Not until the early 20th century would the federal government take action to alleviate the dire circumstances of the Kaibab Paiute.

Pipe Spring and Its Ownership, 1863-1909 [74]

As they carried out Brigham Young's directive, Mormon settlers moved to southern Utah and into what soon was to become Arizona Territory, created by President Abraham Lincoln on February 24, 1863. They laid out town sites, allocated fields, and constructed communal irrigation systems. Between 1863 and 1865, stock ranches were established at Short Creek, Pipe Spring, and Moccasin Spring (also known as "Sand Spring"). At about the same time, ranches were established at the present site of Kanab although these were temporarily abandoned during the height of conflict with the Navajo. [75] Thus, within a very short time period, white settlers had expropriated all perennial water sources in the Kaibab Paiute territory. These were Kanab Creek, Short Creek, Pipe Spring, and Moccasin Spring. The latter two were the only large springs in the area. [76]

The first white man to lay claim to Pipe Spring was James Montgomery Whitmore. After joining the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Texas, Whitmore moved with his wife, Elizabeth, and several children, a brother, and a sister to Utah in 1857. Because he had been a druggist before coming to Utah, he was known as "Doctor Whitmore." [77] Whitmore remained in Salt Lake City until the 1861 call, then moved with his family to St. George. On April 13, 1863, Whitmore received a land certificate for a 160-acre tract, which included Pipe Spring. [78] (It is notable that John D. Lee, participant in the Mountain Meadows incident referenced earlier, signed this certificate.) Upon this tract Whitmore, assisted by Robert McIntyre, established a ranch, constructed a small dugout for quarters, fenced about 11 acres for cultivation, set out about 1,000 grape vines, built corrals, and planted peach, apple, and other fruit trees. [79] While some accounts refer to McIntyre as a hired hand, a number of writers report he was related to Whitmore. [80] It seems possible that he was both related to and worked for Whitmore.

It is important to note that Whitmore's settlement at Pipe Spring coincided with Kit Carson's military campaign against the Mescalero Apache and Navajo in Arizona Territory, as referenced earlier. In 1865 Navajo raiding parties began crossing the Colorado River, raiding settlements along the Arizona Strip. In December 1865 the Navajo attacked the Utah Territorial Militia garrisoned at Kanab, forcing the settlement's abandonment. On or about January 9, 1866, a party of Indians drove off a herd of sheep from Whitmore's ranch. (According to David Chidester of Venise, Utah, Navajo, aided by some Shivwits Paiute, made the raid on Whitmore's ranch. [81] C. Leonard Heaton, long-time monument custodian, wrote that the raiders were Navajo and some Paiute who had been "kicked out of the local tribe because of their wickedness." [82] ) Whitmore and McIntyre set out to trail the raiders, leaving James Jr., Whitmore's 11-year-old son, in the dugout. [83] When the men didn't return, the boy headed on foot for William B. Maxwell's ranch in Short Creek, 25 miles west. He was intercepted by men on horseback who then informed Maxwell of the situation. Maxwell, a major in the militia, began gathering men for a search party. On January 11, 1866, word was received in St. George from Maxwell of the disappearance of Whitmore and McIntyre. Thirty-one local volunteers under the command of Col. D. D. McArthur and a second detachment from St. George of 46 men led by Capt. James Andrus arrived at Pipe Spring to search for Whitmore and McIntyre. [84] Anson P. Winsor was one of those in the search party, as was Edwin D. Woolley, Jr., both prominent in Pipe Spring's later history.

Numerous conflicting accounts relate the events surrounding the militia's January 20 discovery of the bodies of Whitmore and McIntyre and the subsequent retaliatory killings of a number of Paiute men. Some reports say that the Paiute were found to have in their possession some of Whitmore and McIntyre's property. Years later, in July 1914, James Andrus told his version of the story to photographer Charles Ellis Johnson who wrote it down. [85] According to Andrus, his troops had encountered two Indian men in the process of attempting to kill several cattle. They took the two prisoners to the militia camp and turned them over to McArthur. In return for a promise of his freedom, the older of the two Indians led them to the bodies of Whitmore and McIntyre. [86] Later, again in return for a promise of freedom, the younger Paiute led the militia to the Indian encampment where the militiamen arrested nine more Paiute men. In spite of protestations of innocence by these captives, the militiamen held them accountable for the murder of Whitmore and McIntyre and shot and killed them. Thus, according to Andrus' account, nine Paiute men were killed; other reports of the number killed range from 6 to 13. [87] There is no record of what happened to the remains of the slain Indians. The bodies of Whitmore and McIntyre were returned to St. George for burial. All business was suspended on the day of the funeral, January 23, 1866, and over 300 people attended last rites for the two men. [88]

Jacob Hamblin later learned from contact with the Indians that the Paiute men the militiamen had shot to death were innocent. [89] It is worthy of mention that the 1866 slayings of Whitmore and McIntyre and the militia's subsequent killing of Paiute men are alive in the memory of many local Latter-day Saints and Kaibab Paiute today. The controversy would resurface in 1933 when the Utah Trails and Landmarks Association affixed a commemorative marker to the fort. The current site of the Whitmore-McIntyre dugout is located about 100 feet southeast of the fort. Not long after the construction of the Pipe Spring fort, the roof of the old Whitmore-McIntyre dugout collapsed, reportedly under the weight of a cow. The dugout was used thereafter as a trash pit by residents of Pipe Spring. [90]

The slaying of Whitmore and McIntyre and subsequent retaliation by militia against the Paiute were not to be the last blood shed between whites and Indians on the Arizona Strip. On April 7, 1866, Joseph Berry, Robert Berry, and his wife Isabella were killed by Indians near Maxwell's Ranch at a spot since known as Berry Knolls, located 1.5 miles south of Short Creek (now Colorado City). It was not known if the Paiute or the Navajo were responsible. The danger to the Mormon frontier was now grave. Martial law was declared and Brigham Young urged that small frontier settlements be abandoned with residents moving to larger towns for security. No settlement, he advised, should have less than 150 well-armed men. As the theft of livestock was thought to be the Indians' primary objective, Young urged settlers to guard their animals. Practically the entire eastern line of settlements, those in the Sevier Valley, most of those along the upper middle sector of the Virgin, and all the settlements in Kane County as well as Moccasin and Pipe Spring were abandoned, not to be reoccupied until about 1870-1871. [91]

Although Pipe Spring was within the new territory of Arizona, James M. Whitmore had received the land certificate for his Pipe Spring claim from Washington County, Utah Territory. The confusion was attributable to the shifting character of Utah's territorial boundaries, beginning 11 years after its creation, and to a prolonged effort by Utah officials to have the Arizona Strip returned to Utah. During its early history, Pipe Spring fell under the jurisdiction of three different counties in two different territories. From January 4, 1856, to August 1, 1864, it fell under the jurisdiction of Washington County. When Kane County was organized in 1864 Pipe Spring came under its jurisdiction where it remained until 1883. Both these counties were located in the Utah Territory. The size of its territory was reduced a number of times by the creation of the territories of Nevada and Colorado (1861), and Wyoming Territory (1868). More Utah territory was lost when the Nevada Territory's eastern boundary was moved eastward in 1864. As late as 1897, some Utah officials were still arguing to retain the Arizona Strip territory, lands that lay between the Utah border and the Grand Canyon, but to no avail. [92] Arizona's territorial boundaries were extended in 1883 to take in much of the Arizona Strip, and at that time the Pipe Spring ranch was placed under the jurisdiction of Mohave County, Arizona, where it has since remained. [93]

In 1866 Capt. James Andrus was given command of a cavalry company consisting of 62 officers and men and was instructed to examine the country along the Colorado River from the Buckskin Mountain (on the Kaibab Plateau) to the north of the Green River. The expedition left St. George on August 16, 1866, and traveled by way of Gould's Ranch, Pipe Spring, the abandoned settlement of Kanab, Skutumpah, to the Paria River, which they reached in the vicinity of the later site of Cannonville. [94] It may have been at this time (or shortly after) that a stone cabin was constructed at Pipe Spring to be used for periodic encampment by the militia (the north part of what is now known as the east cabin). On November 24, 1868, Colonel John Pearce camped at Pipe Spring with 36 men of the Utah Militia under his command. [95] By March of 1869, Erastus Snow, Bishop of Southern Utah, decided to make Pipe Spring a permanent supply base for the militia. Men were sent to plant turnips and corn where Whitmore had once raised his crops. [96] The stone cabin was repaired for use as guard quarters. In August of that year, John R. Young reported from Pipe Spring that four tons of hay had been cut on the "Moccasin spring creek," 2.5 miles north of PipeSpring. [97] Two tons of this hay were brought to Pipe Spring and a shed was built to shelter 16 horses. [98] By September 12 of that year, a decision was made to winter the militia at Kanab due to its proximity to the Colorado River. [99] The Pipe Spring supply base was soon vacated.

In April 1870 Brigham Young traveled to the site of Kanab and issued a call for it to be reoccupied. During this trip, he surveyed the Pipe Spring area and decided that the site would be a good location for some of the Church's tithed herds. For the safety of local settlers, Young also decided that a fort should be constructed at Pipe Spring. [100] He returned to Salt Lake City and appointed Anson P. Winsor to take charge of the operations, offering an annual salary of $1,200. On his return trip to consecrate the town of Kanab the following September, Young stopped at Pipe Spring to inspect the site for the new fort. Present there at the time were Major John Wesley Powell, Jacob Hamblin, and Chuarumpeak (nicknamed "Frank" by whites), Powell's Paiute guide. Powell reported that the Paiute Indians called Pipe Spring "Yellow Rock Water," after the nearby cliffs. [101] A map produced by Powell's expedition surveys of 1871-1873, however, depicts "Yellow Rock Spring" as located approximately 10 miles southwest of Pipe Spring. This leaves open the question of whether or not Pipe Spring and "Yellow Rock Water" are really the same. [102]

|

|

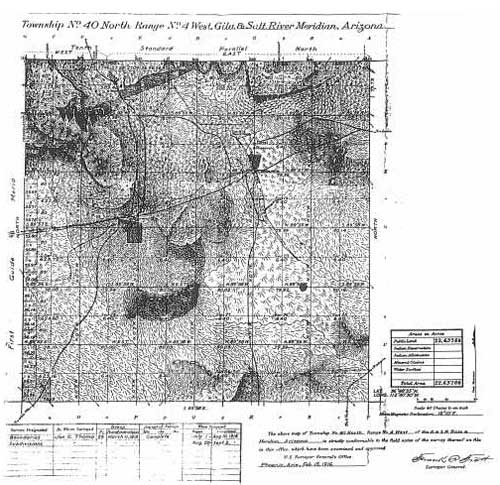

7. Detail from USGS survey map, John Wesley

Powell's expeditions of 1871, 1872, and 1873 (Courtesy Bancroft Library, University of California). |

How did the Church obtain the ranch property? Upon Whitmore's death on January 9, 1866, his widow, Elizabeth Carter Whitmore, inherited the ranch as part of her husband's estate. [103] In December 1870, Mrs. Whitmore made a verbal agreement with Brigham Young to sell the Pipe Spring ranch to the Church. [104] A record of payment to Mrs. Whitmore was not made until just over three years later, however, after the organization of the Winsor Castle Stock Growing Company (Winsor Company). Church historian Andrew Jenson provides a description of the meeting held for the purpose of organizing this cooperative livestock company. [105] The meeting convened in the St. George Tithing Office on January 2, 1873. Erastus Snow was chosen its first chairman. The maximum capital stock agreed to was $500,000. The Board of Directors elected Brigham Young, Sr., president; his nephew, Joseph W. Young, vice-president; and Alexander F. MacDonald, treasurer. [106] Initial subscriptions in stock were made totaling $17,450, with the Church as primary subscriber. [107] Minutes of the meeting stated:

In addition to the 140 acres of land at Pipe Springs, purchased by the Trustee and Trust of the James M. Whitmore estate in 1870, the church has since negotiated for a one-third interest in Moccasin Springs, but which, up to the organization of the Winsor Castle Stock Growing Company, has not been paid for; and therefore, will have to be paid for by that company. Some 15 acres of land have been irrigated by the one-third interest in Moccasin Springs. [108]

The reference to 140 acres is believed to be an error, one that has been repeated in other subsequent accounts. The size of Whitmore's original claim was 160 acres as verified by the land certificate. The reference to purchase of one-third water rights and irrigation of land at Moccasin Spring is important to note and will be discussed under a later section, "Moccasin Ranch and Spring." A memorandum of agreement was made on February 15, 1873, between the Winsor Company and Anson P. Winsor as follows:

In presence of President Brigham Young, Vice-President Joseph W. Young and Secretary Alexander F. MacDonald, at St. George. A. P. Winsor proposes to do the work of herding at the ranches of the company, also the farming and fencing connected therewith at Winsor Castle and Moccasin Spring and the dairy work at the ranches for $3,500 per annum. Anson P. Winsor to pay all board and expenses. [109]

Winsor was to receive $1,000 salary; the other $2,500 was to pay four hired men and one woman. (Winsor received $1,200 salary per year from May 1870 until January 1873. Under the new arrangement, his salary was reduced.) At the preliminary meeting it was recorded, "Mrs. Whitmore to be offered $1,000 in capital stock in the company if she will accept it, for ranch and improvements." [110] Accept it she did, for a January 1, 1874, entry in Winsor Company's Ledger B recorded that she was paid $1,000 in Winsor Company stock. Another Ledger B entry indicated a cash payment to Mrs. Whitmore of $366.64. The latter is believed to be for interest owed resulting from the three-year delay of payment. In exchange, Mrs. Whitmore provided the company with a bill of sale. [111] No legal record of the transfer of title from Whitmore to the Church has ever been located and may have never been executed, given the political tenor of the times.

James M. Whitmore's death left Elizabeth Carter Whitmore with nine children under the age of 12 to raise. After her husband's death, she managed the family farm, raising grapes, apples, and peaches. [112] She became a very influential person in St. George, holding and exchanging a great deal of property. [113] In September 1869 she purchased the home of Jacob Hamblin in Santa Clara. Then she and a "Mrs. McIntyre," whom she had previously been living with, moved to the Santa Clara home. [114] (Mrs. McIntyre may have been the widow of Robert McIntyre. If so, the fact that the widows of Whitmore and McIntyre were living together after the men's deaths lends credence to sources which say the two men were kin. The exact relationship of the two men and two women has yet to be documented.) In 1883 Mrs. Whitmore moved to Salt Lake City where she lived until her death on November 24, 1892.

Anson P. Winsor was one of the Latter-day Saints who responded to the call of 1861. Born August 19, 1818, in Ellicotville, New York, he was baptized into the Church in 1842. As a member of the faithful group gathered in Nauvoo, Illinois, he had acted as one of Joseph Smith's bodyguards. He emigrated from the Midwest to Utah in 1852 with his wife, Emeline Zenatta Brower, and a growing family, and soon located in Provo. (The couple eventually had nine children.) There in 1855, he took in plural marriage a second wife, Mary Nielsen, a Danish immigrant. Winsor's role in the Utah War (1857-1858) has already been mentioned. During the period of heightened conflict with Indians (late 1865-1869), Winsor served as colonel in the Third Regiment of the Utah Territorial Militia under General Erastus Snow. He is reported to have participated in several battles with Indians. [115]

In response to Brigham Young's call to colonize southern Utah, Winsor moved his families in 1861 from Provo to Grafton on the Virgin River, and was appointed its bishop in 1863. Grafton, along with Kanab and other settlements, was abandoned in 1866 during the period of Navajo raids. Winsor was living in Rockville when he was appointed in April 1870 to collect and oversee the Church's ranch of tithing cattle at Pipe Spring. [116] His role as ranch superintendent began that May. [117] Soon after, he sent his 15-year-old son, Anson Jr., to the site to plant a garden prior to the family's arrival. No documentation has yet identified the location of this early garden, but it is reasonable to assume it was the same land previously cultivated by Whitmore and the militia. Because of the lay of the land, the garden would most likely have been located south of the fort where it could be irrigated by gravity flow from the springs. The boy lived in the old Whitmore-McIntyre dugout during this period.

Joseph W. Young, president of the Stake of Zion in St. George and a nephew of Brigham Young, was charged with overseeing the construction of the fort. [118] Young wrote a letter on October 16, 1870, from his home in St. George to President Horace S. Eldredge in England describing his appointment and noting,

This work will keep me out most of the winter, but it is a very necessary work, and I am willing to do my part in it. This Pipe Spring and Kanab country is right between us and the Navajos, and it is the best country for stock raising that I ever saw if it can be made safe against the raids of these marauding Indians. I start out tomorrow with a small company to commence the work. [119]

Presumably, Young and his party left the following day and soon began the preliminary work of laying out the fort. John R. Young, brother to Joseph W. Young, brought his two wives, Albina and Tamar, and their children from Washington, Utah, to Pipe Spring in 1870 so that he could assist his brother with construction of the fort. John R. Young reported that his wife Tamar (born Tamar J. Black) assisted Joseph Young in drawing up the plans for the fort. Construction of the fort began that fall. [120]

It is not known exactly when the rest of the Winsor family arrived, but it was some time prior to Joseph W. Young's arrival. The one-room stone building constructed a few years earlier by the militia was modified in 1870 through the addition of another room to the south, the two rooms separated by an open bay. The Winsors lived in this building, now known as the east cabin. Anson P. Winsor's son, Walter, later reported that Joseph W. Young was also mayor of St. George, thus did not spend all of this time at Pipe Spring. [121] When he was at Pipe Spring, he reportedly shared the Winsors' cabin. In 1870 a second two-room stone cabin was erected west of the fort site to house workers (now referred to as the west cabin or bunkhouse).

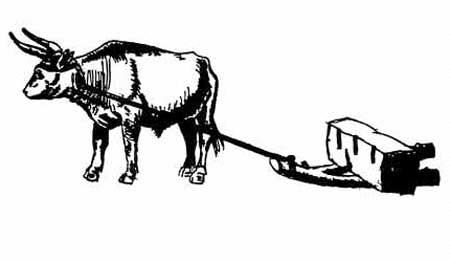

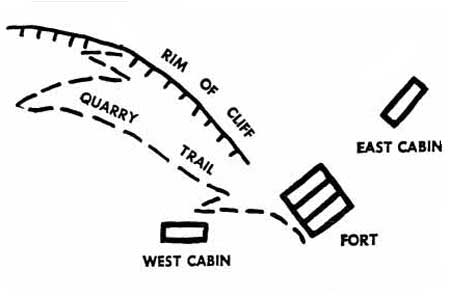

Blocks of sandstone for the construction of the fort walls were quarried from the sandstone cliff immediately west of the fort site. The partially worked stones were placed on a forked log called a "rock lizard" and dragged by an ox down a trail cut or worn into the face of the cliff. This contraption has also been called a "stone-boat," thus the trail has been referred to as both the "stone-boat trail" and the "quarry trail." The proximity of this trail to the fort is shown in figure 9.

|

|

8. An ox dragged building stone on a "rock lizard"

down the quarry trail (Pipe Spring National Monument) |

|

|

9. The quarry trail followed along the cliff face

to the fort's construction site (Pipe Spring National Monument) |

Lumber for the fort came from a sawmill at Mt. Trumbull (located 60 miles from Pipe Spring in the Uinkaret Mountains of the Uinkaret Plateau), and lime was brought from a deposit located eight miles to the southwest near Cedar Ridge. [122] While the fort was originally planned to be 152 feet by 66 feet, Young reduced it to approximately 68 by 44 feet, most probably because threats from Navajo to nearby settlements were no longer a problem after the November 5, 1870, treaty of Fort Defiance. [123] (As mentioned earlier, word of the treaty did not reach Pipe Spring until December, several months after construction activities began on the fort.) Once the possibility of Indian attacks was over, the fort's defensive function was rendered obsolete. Although reduced in size, it still retained its defensive design.

The Pipe Spring fort was completed by April 1872 except for interior work that continued for several years. [124] The completed structure consisted of two sandstone block buildings, each two-stories, that faced each other across a courtyard. Heavy wooden gates, which opened outward, enclosed both ends of the courtyard. Wood shingles covered the fort's roof. For defensive purposes, none of the buildings' exterior walls were constructed with windows but instead were supplied with gun ports.

The north building (or "upper house") of the fort abuts a hillside that historically yielded the site's primary source of spring water. The spring water flowed by gravity southward, beneath the floor of the north building's west room, then through a stone-lined trough across the courtyard, and into the west room of the south building (the "lower house"). The main function of the cattle ranch at Pipe Spring was to produce cheese, butter, beef, and hides for Mormon workers building the St. George Temple, which was under construction 1871-1877. Sheep were also kept at Pipe Spring during this period, providing a source of wool and lamb for the St. George workers. In addition to cooling the dairy room, the water that issued from the spring behind the fort was used for culinary purposes, crop irrigation, and stock watering. [125] Reports detailing the fort's construction, physical appearance, and history as the Church's cattle ranch are described in other sources, and will not be repeated here. [126]

During fort construction, a telegraph line was being constructed from Rockville, Utah, to Kanab, Utah. The organization of the Deseret Telegraph Company dates back to 1861, when the transcontinental telegraph reached Salt Lake City. Church leaders immediately planned to build a line for the settlements from north to south but the Civil War temporarily prevented them from acquiring the necessary wire, insulators, and equipment. During the winter of 1865-1866, the Latter-day Saints subscribed money and contributed teams and teamsters to form a train to transport these supplies from the Missouri Valley. A Church-run school for telegraphy was set up in Salt Lake City, the company was incorporated by the territorial assembly, and construction began on the telegraph line with men's labor credited as a Church tithe. Troubles with Indians during 1865-1870 hastened the line's construction. It reached St. George on January 15, 1867. Pipe Spring was chosen to be a station of the Deseret Telegraph Company, making it the earliest telegraph station in Arizona. The first message was sent from there on December 15, 1871. The telegraph line reached Kanab on Christmas Day, 1871. Eliza Luella ("Ella") Stewart was the first operator at Pipe Spring; she was also was the first operator in Kanab where the office was set up in the home of her father, Bishop Levi Stewart. The arrival of the telegraph line in southern Utah and the Arizona Strip enabled settlers there to communicate with Salt Lake City and thus with the rest of the world. It helped to end the terrible isolation that was characteristic of remote settlements and kept those in Salt Lake City informed of distant developments. By 1880 the telegraph line was about 1,000 miles; 1,200 miles of wire were strung over thousands of rough poles, and there were 68 offices or stations. In 1900 the company was sold to eastern interests. [127]

Major John W. Powell obtained supplies for his Grand Canyon expedition at Pipe Spring in 1871 and 1872. Anson P. Winsor's son, L. M. Winsor, reported that it was during these visits that Powell christened the new fort, "Winsor Castle." Prior to that time he said it was called "Fort Arizona." [128] L. M. Winsor also recalled the family had a vegetable garden planted with tomatoes, corn, potatoes, squash, and pumpkin. In addition, the family kept a vineyard and a variety of fruit trees (peaches, apples, and two varieties of plums) and planted black currants. [129]

The fort at Pipe Spring never came under Indian attack. Relations with the nearby Kaibab Paiute had long been friendly, and the peace negotiated by Hamblin and Powell with the Navajo while the fort was under construction eventually ended the raiding of white settlements. Few references to the Winsors' relationship with the Kaibab Paiute at Pipe Spring have been found so the following quotation is particularly useful. L. M. Winsor reported that his father, Anson P. Winsor, "...spent much time with the Paiute Indians who taught him many things. He acquired a love for these Indians that remained through life, and he always had some of them near or working for and with him." [130] While there had once been occasional Navajo raids in the area, the local Paiute were friendly to the family, the son recalled. In addition to a huge herd of cattle, the Pipe Spring ranch had a band of sheep. John R. Young's son, Silas, remembered that an Indian tended the sheep. [131]

After the signing of the November 5, 1870, treaty, the Navajo became frequent visitors and traders in Mormon settlements. Their raiding of Southern Paiute camps, however, continued. According to Stoffle et al., as threats of Navajo attacks on Mormon settlements gradually waned, the Latter-day Saints broke earlier mutual protection treaties with the Paiute. A significant decline in interactions between Euroamericans and the Paiute characterized the three following decades. Southern Paiute north of the Colorado River sought refuge with other peoples, such as the Hualapai and Havasupai, or moved to more isolated places like the lower Kanab Creek area, and to hidden places along the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon. [132]

A number of Kaibab Paiute cast their lot with the white settlements of Kanab, Fredonia, and Moccasin where they eked out a marginal existence by relying on occasional handouts of food and on limited opportunities for employment doing menial jobs. At least until 1900, payment was usually made in the form of produce or locally produced goods. Even menial jobs were not secure, however. As thousands of poor, land-hungry Church converts from Great Britain, Ireland, and Scandinavia continued to immigrate to the newly colonized areas, many of the unskilled tasks once performed by Indians were turned over to the immigrants. [133]

Anson Perry Winsor continued overseeing the Church's cattle at Pipe Spring until he was called to St. George in the fall of 1876 to labor there as an ordinance worker in the Temple. [134] After Winsor's departure, his son Walter was in charge at Pipe Spring until the arrival of Charles Pulsipher. [135] Pulsipher was elected superintendent of the Winsor Company's herd on January 3, 1877, moving to Pipe Spring from Hebron, Utah, where he had supervised another Church herd. [136] The size of the Pipe Spring herd in mid-1877 was 2,097. Pulsipher lived at the fort with the second and third of his three wives, Sariah and Julia, and children. [137]

By a unanimous vote of stockholders present at a meeting held January 1, 1879, the property of the Winsor Castle Stock Growing Company was transferred to the Canaan Cooperative Cattle Company (Canaan Company) of St. George, headed by Erastus Snow, president of the St. George Stake. Brigham Young, who was its primary shareholder until his death in 1877, founded the Canaan Company in 1870. It was probably the largest of the southern Utah cooperatives, operating dairies, farms, meat markets, and hiring agents to represent it. The company's main ranch headquarters was at Canaan Spring, in a cove at the base of the Vermilion Cliffs a few miles west of Short Creek. [138] Soon after the merger between the Winsor Castle Stock Growing Company and the Canaan Company, Pipe Spring's dairy cattle were transferred to Canaan's dairy ranch at Upper Kanab. Pipe Spring ranch operations then concentrated on the production of beef cattle.

Drought in 1879 and over-grazed range land reduced the Pipe Spring herd. On November 15, 1879, the Canaan Company returned the Pipe Springs property to the Church, or rather, to the Trustee in Trust, President John Taylor. At their next meeting on December 17, 1879, the Company directors approved paying the Trustee in Trust rent for the Pipe Spring ranch from July 1 through December 31, 1879. In late 1879, the Company's Chairman Erastus Snow and President Taylor agreed that annual rent in 1880 for the Pipe Spring ranch would be $250.

The transfer of Pipe Spring to the Canaan Company, then back to President Taylor, may seem curious, but in context of the events of the time, it can be better understood. At the personal orders of Brigham Young, the Pipe Spring fort had been constructed by a work mission of the Church and subsequently used as a tithing ranch. President Young held controlling stock of the Winsor Castle Stock Growing Company as Trustee in Trust for the Church. [139] The legal process to settle Young's estate, begun after his death (which took place on August 29, 1877), was not completed until some time in 1879. [140]

According to Leonard Arrington, the giant share of Church properties in Young's name was eventually turned over to his successor, John Taylor. It is probable that Pipe Spring wasn't immediately transferred to Taylor's control pending the outcome of the settlement of Young's estate. In any event, President Taylor continued the policy of secretly holding certain Church business properties in the names of individual trustees, presumably to prevent federal officials from knowing the actual extent of Church holdings. In early 1879, Canaan Company Superintendent James Andrus was appointed to take charge of the Winsor Castle herd but resigned later that year. Pulsipher stayed on at Pipe Spring into the winter of 1879-1880. [141] On December 17, 1879, the company hired James S. Emett to oversee the Andrus Spring, Short Creek, and Pipe Spring ranches. Census records indicate Emett lived in Kanab. He was released from his position the following year, and soon after the company notified Church President Taylor it would not renew its lease.

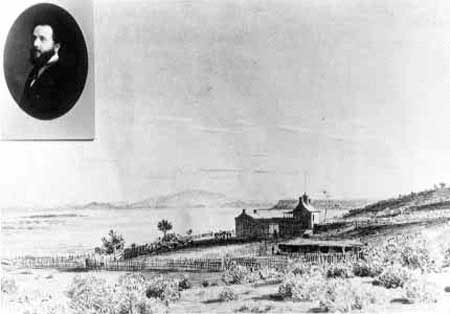

By 1880 the Church's policy in managing the Pipe Spring ranch was to lease it to interested cattlemen who would use it as an investment and care for the Church cattle herd. After the Canaan Company's lease expired (some time in 1880), the ranch was vacant until late 1881 or early 1882 when it was leased to Kanab resident Joseph Gurnsey Brown, who lived there with his wife Harriet. [142] In 1885, shortly before the Brown family left Pipe Spring, they received a visitor, a Frenchman named Albert Tissandier, who stopped both en route to and on return from Kanab. On the first visit, Tissandier drew a sketch of the fort and its setting, the oldest known picture of the site, and presented it to a Kanab family. [143]

|

|

10. Albert Tissandier and his drawing of Pipe

Spring, 1885 (Pipe Spring National Monument, neg. 5013). |