|

Pipe Spring

Cultures at a Crossroads An Administrative History of Pipe Spring National Monument |

|

PART II:

THE CREATION OF PIPE SPRING NATIONAL MONUMENT

Introduction

The reasons for the establishment of Pipe Spring National Monument can best be understood within the context of the overall development of parks, transportation systems, and tourism in southern Utah and northern Arizona during the late 1910s and early 1920s. To a much greater extent than is the case with other national parks and monuments, Pipe Spring's creation and later development hinged heavily on what was happening to parks in the surrounding area and to improvements to the region's transportation network. The development of the region's scenic attractions required a massive and coordinated effort of the federal government (most importantly, the National Park Service, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Bureau of Public Roads), state and county governments in Utah and Arizona, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Church) officials at all levels, the Union Pacific System (Union Pacific or UP) and its subsidiaries, local businessmen, and private citizens. With such a conglomerate of interests involved, it is hardly surprising to discover - as events will show - that this remote site became the vehicle to accomplish a wide variety of goals. Some objectives were quite temporary in nature; others were decidedly permanent. The metaphor for Pipe Spring as "vehicle" is most appropriate, for the invention and popularization of motorized transportation would have long-lasting impact on the fate of this historic site.

|

|

21. Barbara Babcock opening gate for car at Pipe

Spring, ca. 1920 (Courtesy Union Pacific Museum, image 643). |

The Impact of Auto Touring on Utah's Southern Parks and the Arizona Strip

The first automobiles in the United States were produced just prior to the turn of the century. At first considered a luxury, rapid technological improvements and Henry Ford's mass production methods soon made them available to the middle class. The advent of the automobile dramatically changed the nature of tourism in the American West. No longer dependent on the stagecoach or the railroad to reach one's destination, travelers with the incredible "horseless buggy" could now strike out courageously at a moment's notice and tour the countryside to their heart's desire. Edwin Gordon Woolley did just that in June 1909. (Woolley was a son of Edwin Dilworth Woolley, Sr., former manager of the Pipe Spring ranch.) Woolley drove with his wife and brother-in-law, D. A. Affleck (who drove a second auto), from Salt Lake City to Kanab. There they picked up Edwin G. Woolley's half-brother, Edwin D. Woolley, Jr., and Graham McDonald, then they took off for the Grand Canyon's North Rim. Three days later, they arrived at Bright Angel. "Indians came from miles around to see their first 'devil wagons,' which they were loath to believe could run," wrote Angus M. Woodbury about the event. [336] The Woolleys envisioned the wealth of development opportunities that would arise, if only good roads could be built and auto-owning tourists could be enticed into venturing across the desolate Arizona Strip! The U.S. Rubber Company, "to demonstrate the wonderful performance of their product," later proudly displayed the nine tires they wore out on their journey. [337]

Utah politicians could also see the potential for tourism to revive the state's agricultural economy, which plunged into a serious depression after the "boom" years of World War I. [338] Senator Reed Smoot introduced a bill to establish Zion National Park (previously Mukuntuweap National Monument) on May 20, 1919. The bill was passed by Congress, and was signed by the President on November 19, 1919. Stephen Mather was in Colorado's Rocky Mountain National Park for the fifth annual conference of superintendents when word came that Zion National Park had been established. At Albright's urging, Mather made his first visit to the area. He became enamored with the park, returning every year for the remainder of his life.

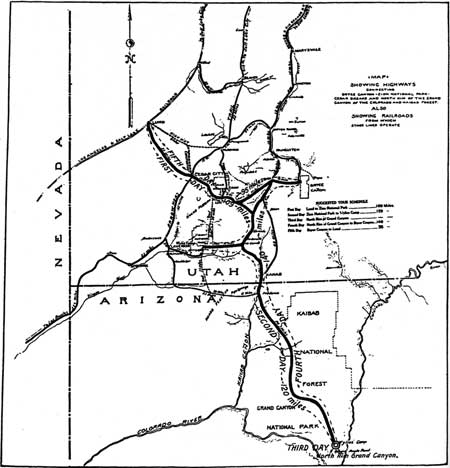

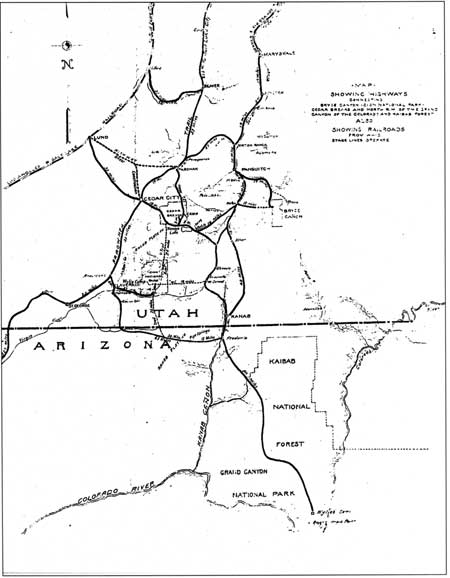

One of the most notable accomplishments of the good-roads movement, in relation to the national parks, was the August 1920 establishment and designation of a great, connected highway between the major national parks of the Far West. The purpose of the National Park-to-Park Highway was three-fold: 1) to make scenic areas more accessible to the public, 2) to aid further development of the West by bringing its industrial resources to the attention of the traveling public, and 3) to attract new settlement. The National Park-to-Park Highway Association (NPPHA) accomplished the undertaking, in cooperation with the American Automobile Association (AAA) and other western organizations. The official designation tour began in Denver, Colorado, on August 26, 1920, "at which time," Stephen Mather reported, "I formally dedicated the National Park-to-Park Highway with appropriate ceremonies to the American people." [339] The 4,700-mile-long circle tour passed through nine western states, crossed every main transcontinental highway and touched most of the north and south highways west of the Rocky Mountains. The only parks in the southwest included on this route were Mesa Verde, Petrified Forest, and the Grand Canyon's South Rim. Mather envisioned the Park-to-Park Highway as "but a nucleus of a great interpark road system which will be developed later on." [340]

|

|

22. Map showing National Park-to-Park Highway and

interpark road system (Reprinted from Report of the Director of the National Park Service, 1920). |

In conjunction with the dedication of the highway, a National Park-to-Park Highway conference was held in Denver, Colorado. Utah's Governor Simon Bamberger sent Randall L. Jones as its representative. (Jones was an architect and a native of Cedar City.) There, plans were laid to coordinate the local movements for good roads into a park-to-park system. The NPPHA and AAA continued to hold annual conferences each year in various western cities. By 1923, thanks to their efforts and those of chambers of commerce, boards of trade, and other local civic organizations, the "great circle route" had expanded to 6,000 miles and included 12 national parks. [341] The NPPHA's objective was to hard surface the entire route (only one-fourth of this length had been "permanently improved"). In support of the work of the NPPHA, the National Highway Association offered in 1923 to print maps depicting the National Park-to-Park Highway for public distribution by the Park Service.

While the nation wide effort to provide a highway to link national parks was growing, state and local officials in Utah and Arizona were well aware of the need for local road improvements. Without them, the vast majority of motorists would visit only the most well known and easily accessible of the parks. In the early 1920s, most of Zion National Park's visitors were Utah residents, folks long accustomed to the terrible conditions of rural roads. To reach Zion from the east, travelers drove down through central Utah to Fredonia in northern Arizona, then, passing Pipe Spring, westward to Hurricane "on a mere faint trail where there was some danger of getting lost and perishing," wrote historian John Ise. [342] There was a rough road from Hurricane to Rockville and to Zion's entrance. Even the best of roads and bridges were susceptible to washouts from flash floods, making a well-planned road trip still a gamble during some seasons. If one was spared the fate of washouts and of having one's vehicle mired in the tire-clenching "gumbo" created by rainstorms, a road trip through many parts of Utah or Arizona in those days was always accompanied by a steady diet of dust.

|

|

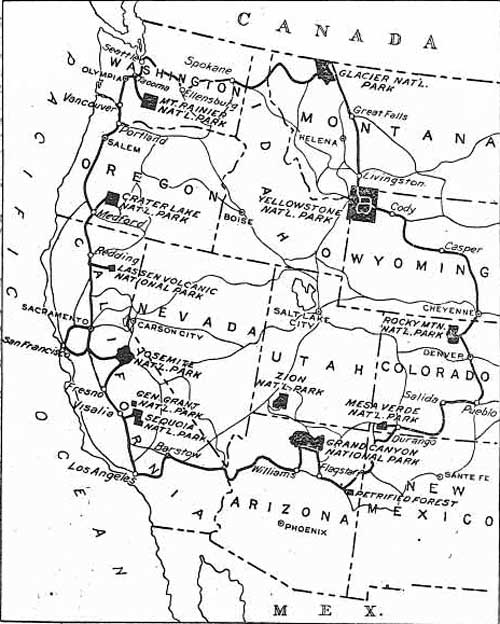

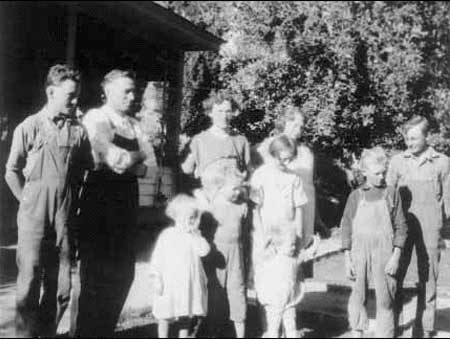

23. Map detail, Utah State trunk Lines, State Road

Commission, 1923 (Courtesy Union Pacific Museum). (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

In his 1923 annual report to Congress, Mather wrote that more than 60 percent of park visitors came in their own private automobiles. [343] A detail from the following map produced by the Utah State Road Commission and dated 1923, shows existing roads in Iron, Garfield, Washington, and Kane counties (as well as the Hurricane-Fredonia road) in 1923. Also depicted is the Union Pacific's Los Angeles and Salt Lake City Railroad line passing through Lund with its newly constructed spur line to Cedar City. (Pipe Spring National Monument is not shown on the map, perhaps because it was located in Arizona or because the map was produced prior to the establishment of the monument.)

Mather Visits Pipe Spring

Stephen T. Mather's first visit to Pipe Spring was made in conjunction with his participation in the dedication of Zion National Park that took place on September 15, 1920. Among those speaking at the dedication were Senator Reed Smoot and Church President Heber J. Grant. (In the usual blurring of lines between Utah's Church and State, Grant was representing Governor Bamberger at the event). The park's new status resulted in an immediate boost in visitation, which doubled between 1919 and 1920, from 1,914 to 3,692. After attending the dedication ceremony at Zion National Park, Mather drove south to visit other southwestern monuments. During his tour he stopped at Pipe Spring and took photographs of the fort. [344] (At this time the old wagon road traveled by motorists from Hurricane to Fredonia passed right by the fort.) Mather briefly discussed the idea of making Pipe Spring a national monument with the Heatons. Not only were they receptive totheidea, they promised to furnish labor should the National Park Service (Park Service or NPS) decide to undertake a restoration. [345]

On June 6, 1921, about nine months after making his first visit to Pipe Spring the previous fall, Mather wrote to Office of Indian Affairs Commissioner Charles H. Burke that he had found "a very interesting old homestead" on the Kaibab Reservation that he wanted to acquire for the park system. [346] What transpired during the time between Mather's letter to Burke and his next visit to Pipe Spring is only sparsely documented. If he was not already aware of the legal troubles Charles C. Heaton was having in proving his Pipe Spring claim, it is quite likely that Commissioner Burke informed Mather of the facts in 1921. Consultation with Arizona's Governor Thomas E. Campbell and U.S. Senator Carl Hayden would have also been in order, but no record of such contacts have yet been located. [347]

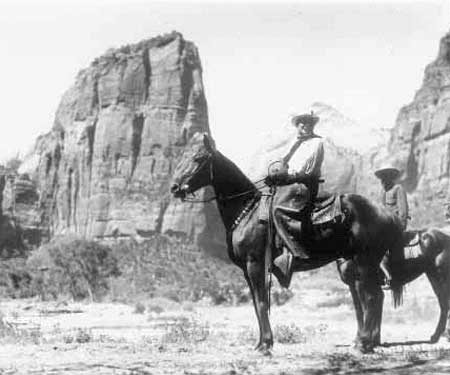

Mather returned to Pipe Spring in the fall of 1921, this time in the company of Union Pacific's President Carl R. Gray, Senator Hampton of Montana, and possibly one or two others. [348] Mather took the group on a tour of southern Utah and northern Arizona to demonstrate the area's potential for tourism. The men left Zion early one morning in Mather's Packard heading for the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. At Short Creek, Mather's automobile got stuck in the sand. In a 1991 interview, C. Leonard Heaton related the rest of the story as follows:

They were stuck there for about three or four hours in the sand, and when they come to Pipe Spring, along about one or two-o'clock, they were so famished and they didn't have any water with them. And while they were resting there he [Mather] began to look around the fort and my father [Charles Heaton] was down there riding on the range...

And then my father come up on horseback and Randall Jones was with him from Cedar City. He was promoter of tourism in southern Utah, and Dad knew Randall Jones, and he introduced him to Mather. And after Mather walked through the fort, the old fort (a lot of it was torn out then, inside of it and things like that), he asked my dad what the history of the place was. So Dad told him... about the early history of the place.

And then Randall Jones said, 'How close is it where we can get something to eat? These fellows,' he says, 'they haven't had anything since six o-clock this morning.' And my dad told him, 'You can go up to Moccasin and I think my wife can fix you a dinner.' ...And Dad told them how to get to Moccasin and he got on his horse and galloped up to here and by the time they got up here my mother had dinner about ready for them.... Mather had thought that Pipe Spring would be a good place for tourists to stop on the road from Zion to the Grand Canyon or the Grand Canyon back to Zion. And that was it. From that time it was Randall Jones and these other fellows, they decided to make Pipe Spring a national monument... [349]

Leonard Heaton was not at Pipe Spring at the time of Mather's visit, so he most likely heard this account from his father, Charles C. Heaton. The fact that Randall Jones was present with Heaton is a sure indication that this was a prearranged meeting. [350]

According to historian Robert H. Keller, Mather was sympathetic to the Church and fascinated by its history. He also could see the benefits of making the site a part of Union Pacific's tour package. He soon took direct action to acquire Pipe Spring for the National Park Service. On January 18, 1922, Mather wrote to Apostle George A. Smith, a high Church official, and asked him to approach the Heatons about selling Pipe Spring. Mather asked Smith to negotiate a purchase price and to then act as spokesman to raise the necessary funds. In his letter, Mather placed a heavy emphasis on his belief that Pipe Spring as a national monument would "be a big stimulus to the work that is now going on to develop the tourist possibilities of this southern Utah and northern Arizona country." [351] Smith and President Heber J. Grant worked together to help Mather achieve his goal, but progress was very slow. In the meantime, Mather, Union Pacific officials, and federal and state government officials began to focus on the daunting challenge of providing a road system capable of handling the tourist traffic they all dreamed of.

"If You Build It They Will Come" - The Challenge of Roads Less Traveled

On Director Mather's second visit to Pipe Spring, his party experienced first-hand the problems associated with Utah's poor roads. Yet in 1921 much was happening that would soon greatly impact the ability of states to improve their roads. That year the Federal Aid Law was passed which provided that the federal government would aid in the construction of highways in several states to the extent of funding seven percent of the total mileage of the public highways in each state. [352] This law is sometimes referred to as the "seven percent system" for highway development. Under this program, Utah received 74 percent of the construction costs of roads and paid the balance of 26 percent plus preliminary engineering costs. [353] Plans, specifications, and estimates had to be approved by the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads. Roads were required to have at least 18 feet of either gravel or paved surfacing with a three-foot shoulder on each side. Maximum grades were not to exceed six percent and there were certain specifications for bridges, culverts, and other road features.

The difficulty in Utah in the early 1920s was that the state had no funds for road construction, thus the 26 percent amount payable by the state had to be raised by individual counties through subscriptions. [354] Many rural counties in southern Utah were poor, resulting in a delay in financing road projects in some areas. County residents needed to be convinced that development of roads in their county would result in general economic or other improvements. Local associations were formed to promote the development of roads, while both state and local officials, as well as businessmen, acted as ardent boosters (Cedar City's Randall L. Jones was one such booster). Road development was a costly gamble toward future economic prosperity, with much at stake. Not surprisingly, competition for road funds and highway projects was at times fierce and always intensely political. While the struggle to raise local funds would be slow-going, the new Federal Aid Law set into motion in 1922 a number of serious road studies by federal agencies (including the National Park Service), the state road commission, and Union Pacific.

Along with its surveys of Utah's roads, Union Pacific directed its information-gathering efforts toward accumulating knowledge of the agricultural, mining, and scenic resources in southern Utah with the intent of expanding its transportation network in those areas with marketable resources. In 1921, at the urging of Utah politicians, Union Pacific's President Gray made a personal investigation of some of Utah's southern agricultural communities (Cedar City, Parowan, and Fillmore) and interviewed farmers and ranchers. Impressed with the area's potential, Gray authorized the building of a railroad spur to Fillmore, which was completed the following year. Later trips were made by UP officials in September and October. The latter occurred during the week of October 22, involving a Mr. Platt and an unidentified official who filed the report. Their purpose was to continue the company's survey of southern Utah and northern Arizona attractions. The two men traveled from Kanab to Zion via Pipe Spring and Hurricane. Their later trip report stated,

After making this second trip via the Pipe Springs desert and Hurricane, I am more than ever confirmed in the opinion that a touring trip in which the railroad is interested in advertising must avoid the most unpleasant hot desert trips via La Verkin, Hurricane and Pipe Springs on the south, and via Parowan, Bear Valley and Panguitch on the north. These hard hot trips would soon result in some very unfavorable advertising by tourists. The highways and roads on these portions of the trips are very bad. On account of being out of line of general travel, these particular stretches stand very poor chance of being maintained properly. A large part of these stretches are unattractive. The heat, dust and poor roads destroy the pleasure of the entire trip. [355]

This official proposed a route that would have excluded the "most unpleasant" roads described above and a loop tour that would have excluded Pipe Spring. This alternative route, however, required additional road construction and improvements. The significance of this report is that it appears to have been the first of several to recommend against use or development of the Hurricane-Fredonia route, a sentiment that resulted in continued isolation for Pipe Spring National Monument.

The problem of roads for the National Park Service was two-fold: first, how to construct and maintain a viable system within parks, and second, how to persuade state and local officials to finance a transportation network that would enable visitors to get to the parks. In late 1921 Director Mather called for a meeting to be held to discuss park developments in southern Utah. Called the Governor's Committee on National Park Development, the assembly was scheduled for December 19-20 in Salt Lake City. About three weeks prior to the meeting date, Mather wrote D. S. Spencer, General Passenger Agent of the Union Pacific System, regarding plans for the event. Mather's remarkable political acumen is illustrated by the request he made of Spencer, whose office was in Salt Lake City:

The success of the meeting will largely depend on how representative a one it is. We should absolutely count on having President Grant there, and Apostle Smith if possible. We will want men like Lafayette Hanchett and Mr. [William W.?] Armstrong of the National Copper Bank, besides the Governor, Mayor [C. Clarence] Neslen, and others. Cedar City should be represented by Randall Jones and one or two of their important men. Petty and some of the Chamber of Commerce men from Hurricane should be there, as well as Mr. [Joseph?] Snow of St. George. We ought also to get the elder [Ole] Bowman of Kanab, and Johnson [sic; Jonathan] Heaton, or one of his sons, as it will be advisable to bring up the Pipe Springs proposition at the same time. We should also count on having Mr. Adams and Mr. Basinger present. [356]

Lafayette Hanchett was president of the National Copper Bank in Salt Lake City and chairman of the Governor's Committee on National Park Development; H. M. Adams was vice-president of UP, in charge of traffic; W. S. Basinger was UP's passenger traffic manager. Joseph Snow was a promoter of the Arrowhead Trail, as well as represented St. George in the Southern Utah & Northern Arizona Road Association.

Horace Albright (at the time both superintendent of Yellowstone National Park and field assistant to Director Mather) was unable to attend the December meeting but sent a letter to Mather at Hotel Utah expressing his views on park development in southern Utah. It would be important to connect financial interests in Salt Lake City to the new developments, he advised. Albright also stressed the importance of a Park Service alliance with Union Pacific:

That Union Pacific support for the new project would be the biggest guarantee of its success. Such support would be beneficial in every respect and I do not see where any grounds could be found for criticism of the Park Service for dealing with the Union Pacific. I mention this because in the past it has been customary for everybody to rap a big corporation, particularly the railroads, and to look upon their every action with suspicion. I believe we are getting away from this sort of thing now and are coming to realize that railroads and other big organizations are necessary and desirable in our commercial life and that any business is not necessarily bad because it is big. [357]

Mather followed Albright's advice and achieved successful results in the region, as evidenced by later events.

The December meeting was held in Salt Lake City at the State Capitol's Commercial Club. It was called to order by Governor Charles R. Mabey and chaired by Lafayette Hanchett. One hundred representatives attended, including some from almost every county in southern Utah where scenic attractions were located. In addition to the National Park Service, the U.S. Forest Service was represented. Officials from the State Road Commission and from the railroads (Union Pacific System and the Denver & Rio Grande Western) were also present. The chief business of the meeting was "The Marketing of Utah Scenery." Topics for discussion included linkage of Utah's southern attractions with the Grand Canyon; the construction and maintenance of connecting highways and selection of best available temporary and permanent routes; the provision of adequate lodging and transportation facilities; plans for securing adequate state and federal legislation; enlisting the cooperation of national, state, and county organizations, as well as chambers of commerce and other civic organizations; and plans for adequate surveys of park territory and highways. Those present passed a resolution endorsing and pledging support for the plans made. Five subcommittees were created to tackle all of these issues. Appointees to the five committees constituted exactly the kind of powerful coalition that Mather had envisioned. Unfortunately, there is no record of whether or not Jonathan Heaton or a family representative attended the conference, but the fact that Mather had requested that a family representative attend strongly suggests that a Pipe Spring "deal" was already in the making by December 1921. [358]

At this meeting, Mather presented a plan for a system of roads that would link the scenic attractions of Utah. The convention unanimously adopted his recommendation. This system was intended to connect Zion, Cedar Breaks, Bryce Canyon, Kaibab National Forest, and the Grand Canyon's North Rim. The Salt Lake City meeting and Mather's proposals drew considerable attention in the press. The Deseret News published a lengthy report, which included the following excerpt:

State and local organizations and citizens must unite in placing suitable accommodations in the region of Utah's scenic wonderland and with these accommodations installed developments will be pushed rapidly by the federal government and the railroads. This appeared to be the consensus of opinions expressed today at the conference of officials called by Director Stephen T. Mather of the National Park Service for deciding on some definite course of action to pursue in exploiting the scenic attractions of the state...

The necessity of good roads and the founding of good hotels so that the people could be cared for was urged...

Director Mather presented a definite proposal before the convention that a state park association be organized in Utah with representatives from various part of the states as members. [359]

The next day, the Deseret News followed up the meeting with three more articles. The first, "Highway System to Link Utah Parks Proposed," reported that plans were adopted at the conference for the improvement of existing roads and the construction of new ones that would link the scenic attractions of southern Utah and northern Arizona together, hopefully by the 1922 travel season. Among a number of proposed plans was the construction of a road from Rockville to Short Creek and improvement of the segment between Short Creek, Fredonia, and Kaibab National Forest. The article reported another proposal: "Construct a road from Mount Carmel to the rim of Zion canyon." [360] No one at the time knew if such an idea could be carried out, or at what expense. The engineering subcommittee was to coordinate with the National Park Service, U.S. Bureau of Public Roads, U.S. Forest Service, and state, county, and local authorities to develop the improved road system. This article also points to the driving enthusiasm of Church President Heber J. Grant, who spoke at the conference. The newspaper referred to his speech:

Heber J. Grant told of the power of scenic attraction and how he had been led to visit the Yellowstone park and the Grand Canyon after being told of their wonders in Europe. He pronounced himself a thorough convert of the possibilities of a national park in Cedar Breaks and Zion canyon and announced that he believes in the 'gold mine of tourists.'

'I am ready to work,' he said, 'to the best of my ability to try to persuade other people to put up their money. I have been called long ago the 'boss beggar' in the 'Mormon' church.' [361]

President Grant meant what he said. His persuasive "begging" would eventually be successful in helping to raise the funds needed for the Park Service to acquire Pipe Spring from the Heaton family of Moccasin. The hopes of conference attendees that the new road network would be in place for the 1922 tourist season, however, were overly optimistic.

The second article appearing in the Deseret News referenced plans for an improved road system and reported that resolutions made at the Salt Lake City meetings included a call to enlarge Zion National Park to include Cedar Breaks, and for the state to take action to make Bryce Canyon a state park. [362] While Albright wanted to see Bryce Canyon brought into the national park system, Mather at this time favored the idea of it being part of a state park system that would supplement the national system. [363] (The Department of the Interior inaugurated the state park movement in 1921 with its first national conference held that year in Des Moines, Iowa. [364] ) A third newspaper article focused on Utah's need to complete a primary concrete road called the Arrowhead Trail. [365] The road passed through Iron and Washington counties, linking Cedar City to St. George. Large amounts of money were being spent to promote it as an all-year route from southern Utah to Los Angeles, reported Joseph Snow of the Arrowhead Trail Association, who believed their efforts had led to a substantial increase in automobile traffic and revenue in his home town of St. George.

The Role of Union Pacific in the Parks' Transportation Network

While the railroad and National Park Service shared a common goal - to attract people to the parks and to ensure them a memorable visit - there were different reasons behind their objectives. The Park Service's primary goal was preservation-oriented. It recognized that survival of the national parks and monuments hinged on the number of people who claimed direct benefits from scenic preservation. [366] As might be expected, the railroad companies' objectives were profit-oriented. There was a long and successful history of the railroads investing in Western tourism, both in promoting the establishment of scenic preserves and in offering transportation and accommodations to tourists to the relatively remote locations of such places. The Northern Pacific promoted the 1872 creation of Yellowstone National Park; Southern Pacific campaigned for Yosemite, Sequoia, and General Grant reserves in the 1890s, all ultimately set aside; the south rim of Arizona's Grand Canyon was made accessible in 1901 by the Santa Fe Railway; and the Great Northern Railway's Louis W. Hill enthusiastically supported the 1910 establishment of Glacier National Park in Montana. Some of the railroad companies constructed grand hotels in the nation's parks and spent huge sums of money advertising their scenic splendors in brochures, complimentary guidebooks, and full-page magazine spreads. [367] The parks needed the railroads and the railroads needed the parks. Their alliance was well established before World War I.

Immediately after World War I ended, the United States experienced what can only be described as a transportation revolution, brought on by the invention, mass production, and rapid spread of the automobile. By 1919 the availability and popularity of motorized vehicles posed a serious financial threat to the economic well-being of the railroads as former rail passengers purchased and used their own automobiles. Trucking companies were formed, offering expeditious freight transportation service. The motor bus was developed in 1912 by C. S. Wickman of Hibbing, Minnesota, who later founded the Greyhound Corporation. Steamships using the Panama Canal, opened in 1912, increasingly diverted freight traffic away from rail transport. Along with other railroad company managers, Union Pacific President Carl Gray found himself facing a new world. Railroad historian Maury Klein wrote that in 1919, "On every side, Gray found himself hedged in by forms of competition that had scarcely existed before the war." [368] A revolution in energy sources as well as means of transportation was in progress. Pipelines now transported much of the West's oil and natural gas to market, increasingly preferred by industries over coal, a staple of Union Pacific traffic. The rapidly developing field of commercial aviation was already eating away at one of the railroad's most lucrative services, mail delivery. To survive the challenge, wrote Klein, "the railroads had to redefine their place in an expanded transportation industry." [369]

As more and more people bought automobiles, the summer vacation emerged as a national institution. Not only were vacations touted as enjoyable recreation, but as a means of bringing about wholesome family togetherness. The transportation revolution required the rapid development of a road system. The total mileage of surfaced highway doubled between 1910 and 1920, then doubled again between 1920 and 1930. [370] Ironically, a major portion of the highway system came to be constructed on right-of-ways leased from the railroads. State and federal governments poured $1.8 billion into highway construction between 1922 and 1930. [371] Until 1929, states were challenged to find sources of funding for road development. Then in 1929 a gasoline tax was imposed in every state to defray the expense of road construction and maintenance.

The impact of the new forms of transportation was immediately felt by the railroads. In 1920 rail passenger travel reached a peak of 1.27 million passengers. Over the next 10 years, the numbers steadily declined toward 707,987 passengers in 1930. [372] Passenger revenues went from $1.17 billion in 1921 to $731 million in 1930, a drop of 37 percent. [373] The railroads were forced to accept the popularity of the auto, and to find a way to integrate automotive transportation into their tourism-related plans and operations. As a result some redefined themselves as transportation companies that not only sold rail travel, but offered planned motor coach tours, complete with restaurant and lodging accommodations, as well. During the 1920s, Union Pacific pioneered the practice of operating buses along with its rail lines in southern Utah and northern Arizona parks.

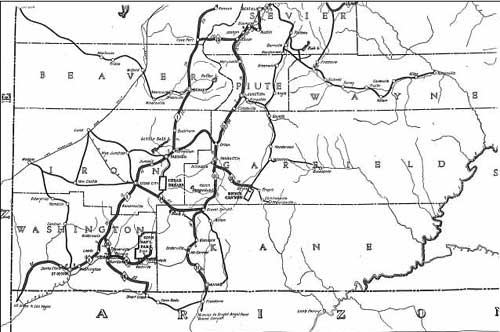

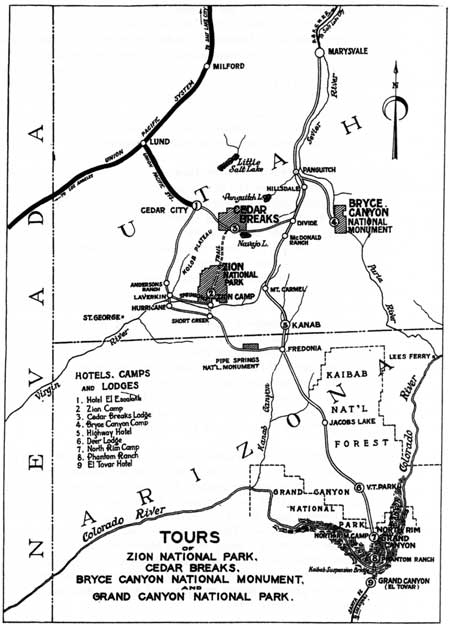

The January 1922 issue of The Union Pacific Magazine, included an article entitled "Zion - Our Newest National Park - And Other Southern Utah Scenic Attractions," by UP official D. S. Spencer. The first in a series of articles on scenic attractions found along the transportation routes of the Union Pacific, the article painted a highly romantic picture of travel in the area's "undiscovered country:"

The opening of Zion National Park to tourist travel during the last few years, has resulted in directing attention to other remarkable scenic regions in southern Utah and northern Arizona, including Cedar Breaks, Bryce Canyon, Kaibab Forest, and the North Rim Grand Canyon National Park, so that it is now impossible to think of Zion National Park without thinking of these other attractions, each of which has a distinctive geological individuality. To reach a fair estimate of them you must see each one, and as you pass from one to the other, inspiration exalts the soul, and reverence bows the head. [374]

Alluding to the Great Northern Railway's "See America First" campaign, Spencer declared "...until one has seen Zion and Southern Utah, he has not seen America." Along with the article, a map was offered to readers to assist them in their planning of future vacations.

The map herewith, based partly on actualities and partly on proposed improvements, gives an idea in tabloid of the relative locations of the features mentioned. Reference to it demonstrates that when the road plans are consummated, the schedule of the Southern Utah attractions will embrace a circle tour... [375]

What is interesting to note on this map is the 18-mile "trail" shown traversing Zion National Park toward Mt. Carmel. This trail appears to be the basis for Union Pacific's confidence that a road could be constructed that would perfect their plans for their circle tour, a multi-park trip they began to promote (at least internally by way of The Union Pacific Magazine) as early as January 1922. This approximate route would later become the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway, not to be completed until 1930. In addition, the UP map shows a 25-mile "trail" from Zion to the Hurricane-Fredonia road, terminating at about the location of Short Creek. This route approximates the Rockville cutoff road, to be constructed 1924-1925. The development of both routes was an important part of UP's plans and, when completed, would considerably shorten the travel distance between parks while improving the scenic aspects of the tour.

The Union Pacific tour outlined in this article began at Lund then went to Cedar Breaks, Zion National Park, the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, Bryce Canyon, and then ended at Lund. While tourist camps then existed at Zion, Bryce Canyon, and the North Rim, the article promised readers,

..it is reasonable to assume that within the next few years each of the four attractions [Cedar Breaks included] will be provided with both hotels and camps and; with the completion of the necessary connecting highways, will provide accommodations corresponding in service with those in Yellowstone Park and others of our long known National Wonderlands. [376]

The map showed no planned tour routes to travel the Hurricane-Fredonia road or to go to Pipe Spring (yet to be declared a national monument) on its 464-mile circle tour. The tour route counted heavily on road improvements along the route from Mt. Carmel to Kanab and on an entirely new road, the Zion-Mt. Carmel road. With planned road developments accomplished, Spencer assured readers, the circle tour could expected to take only five days. This article is an excellent example of a marketing tactic used by Union Pacific in its southern Utah campaign throughout the 1920s: that is, creating a public desire and demand for an improved road system in Utah by having its agents paint a glowing picture of the future that lay ahead, once the new road system was in place. It was so effective a tactic, in fact, that on at least one occasion, a Utah official pleaded for them to stop promoting the region until the necessary road improvements had been completed. UP official, J. T. Hammond, Jr., reported that in a November 1923 meeting he had with State Land Commissioner John T. Oldroyd, that Oldroyd "...stated to me that he thought it would perhaps be for the best interest of the Union Pacific and for the State of Utah as well for the Union Pacific not to feature Southern Utah until the roads were made safe and convenient for handling tourist travel." [377]

Union Pacific was by no means alone in agitating those in power in Utah for improved roads. In addition to the successful Salt Lake City Governor's Conference of December 1921, Mather worked on a local level to obtain his objectives where road improvements were concerned. Correspondence of April 1922 attests that Mather personally wrote to William W. Seegmiller of Kanab and Charles B. Petty of Hurricane urging them to push through the construction of the Hurricane-Fredonia road. (Petty and Seegmiller served on the committee of the Southern Utah and Northern Arizona Road Association. The committee included representatives from a dozen towns in the two areas. Zion's Acting Superintendent Walter Ruesch represented Springdale on this committee; Dr. Edgar A. Farrow represented Moccasin.) This Hurricane-Fredonia route took travelers from Zion to the Grand Canyon, which at the time some favored over the poor road that lay between Mt. Carmel and Kanab.

While construction work on the road from the Hurricane end commenced about February 1922, Petty informed Mather that nothing had happened on the Fredonia segment. Mather expressed his appreciation to Petty and informed him, "We have had a number of inquiries about travel conditions in Southern Utah and Northern Arizona, and I confidently believe that an increased number of people will visit that beautiful and interesting section during the coming year." [378] At Petty's suggestion, Mather then wrote Seegmiller, telling him of the progress in Utah under Mr. Petty while adding, "I know that you will see to it that construction on the Fredonia end of the road is carried out as soon as possible so that the whole road will be in good shape for this season. It is bound to be a great help to travel which should develop this year." [379]

During early July 1922, a party of UP traffic officials, headed by Carl Gray, H. M. Adams, and W. S. Basinger, toured the scenic areas of Utah's south. During this trip Gray reportedly offered to buy the El Escalante Hotel (designed by Randall L. Jones) in Cedar City. [380] Numerous other investigatory trips were made by UP officials in the following months, including one that consisted of a party of 10 men, with hotel and engineering experts, led by Basinger during the second week of October 1922. Accompanying the high level officials on this trip was NPS Chief Civil Engineer George E. Goodwin. The group traveled to Zion, Cedar Breaks, and Bryce Canyon studying potential sites for hotels and water sources.

The following month (November 1922) The Union Pacific Magazine touted its commitment to the development of transportation to and tourist facilities in the attractions mentioned above. It reprinted an article by D. S. Spencer previously published in the Salt Lake Tribune on October 16, 1922. [381] The article described the company's plans to construct two railroad branch lines, a 31-mile spur from Fillmore to Delta and a 32-mile spur from Lund to Cedar City, at a cost of $3 million. The company also planned to acquire and complete the El Escalante Hotel in Cedar City (which had been under construction for several years), to construct two hotels at Zion and Bryce Canyon, and to furnish a lunch station and limited hotel accommodations at Cedar Breaks, at an additional estimated cost to the company of $2 million. The Lund-Cedar City spur line would open up markets to agricultural land and enable locals to market the area's rich iron ore and coal deposits to industrial promoters. A new steel mill was planned in Provo in anticipation of access to the rich iron fields of Iron County; even automobile manufacturers had their eye on the area. The attention of railroad men, however, was first and foremost on developing the gold mine of tourism.

The Railroad Comes to Cedar City

The year 1923 was quite an eventful one in the history of tourism in southern Utah. The first step in Union Pacific's development program at Zion and Bryce Canyon was the completion of the Lund-Cedar City line. In 1922 the Interstate Commerce Commission had granted a certificate of necessity and convenience to Union Pacific allowing them to build the spur line from Lund to Cedar City. The new line was justified on the basis of anticipated traffic from livestock, agriculture, iron ore, and tourist travel. Cedar City residents had raised $57,000 to purchase a right-of-way for the new branch line. On March 12, 1923, the Salt Lake Tribune announced construction on the Union Pacific's Lund-Cedar City line would begin on March 15 and reported extensively on related southern Utah developments. [382] The UP had already taken over the El Escalante Hotel in Cedar City, repaying its citizens for the $80,000 already invested in a cooperative plan for the building's construction. (Union Pacific completed its construction by the summer of 1923. [383]) In addition, it was reported that Union Pacific would invest $250,000 to construct a 100-room hotel in Zion, with plans to invest another $200,000 in constructing a second hotel at the rim of Bryce Canyon.

In March 1923 a federal appropriation of $133,000 for Zion National Park was allocated for survey and specifications of park roads. The appropriation included $40,000 for the construction of a bridge on public land outside the park boundary, crossing the Virgin River near Springdale, Utah. The bridge was to be used to permit a shortcut into Arizona (later known as the Rockville shortcut or Rockville cutoff) with work undertaken during the winter of 1923-1924. The U.S. Forest Service, both in southern Utah and northern Arizona, continued its program of improving roads on lands under its jurisdiction. Not all improvements were the result of state and federal governments, however. In Washington County citizens raised $27,000 in subscriptions for road improvements in their area. Union Pacific's Parks Engineer Samuel C. Lancaster and NPS Chief Civil Engineer George E. Goodwin were reportedly in the process of going over the southern Utah territory. In anticipation of road improvements, Union Pacific planned to invest $750,000 in motor buses in 1924.

In early March 1923, Utah passed legislation allowing the leasing of state school lands at Bryce Canyon for hotel and tourist camp purposes for up to 25 years, with the option of a 25-year renewal. John T. Oldroyd had drafted the bill with the approval of Governor Mabey. It went into effect on March 26 when the governor signed it. On March 29, 1923, the Deseret News announced the incorporation of the Utah Parks Company, a subsidiary of the Union Pacific System. (Carl Gray and H. M. Adams headed both as president and vice-president, respectively.) The corporation was formed, reported the newspaper,

...for a period of 100 years for the purpose of building, buying, owning and operating practically every conceivable convenience for tourists visiting the park section including hotels, chatels, inns, restaurants, garage and livery stables, stage and truck lines, skating rinks, tennis courts, golf links, swimming pools, bowling alleys and billiard rooms, power lines and plants, water systems, real estate and concessions of various descriptions. [384]

By this time, the federal government had already given Union Pacific approval to construct visitor accommodations at Bryce Canyon. They and their subsidiary, the Utah Parks Company, were not interested, however, in investing huge sums in building tourist accommodations on land leased from the state. Rather, they sought to purchase sufficient land on which to site primary developments and to lease additional land. On May 4 Oldroyd announced that the former action withdrawing the entire school section of Bryce Canyon land from sale had been revoked. [385] The very same day UP's solicitor George H. Smith filed application to purchase a 40-acre tract of a state school land section located on the rim of Bryce Canyon and to lease an adjoining 600 acres. [386] The proposed sale was opposed by some on the grounds that scenic resources were the property of all the people and future generations. The Chamber of Commerce voted on May 12 to refuse endorsement of UP's application to purchase land at Bryce. [387]

Meanwhile, President Gray set about garnering support for Union Pacific's plans among the state's businessmen. On May 20, 1923, a large delegation of Los Angeles UP officials and Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce businessmen arrived in Utah to conduct a three-day inspection of the Delta-Fillmore agricultural area, to which UP had just completed building a spur line. [388] Gray traveled from New York City, arriving in Delta on May 21, to meet with the delegation and to present addresses at Delta's Chamber of Commerce. The following day, Gray and his party inspected Fillmore with Gray making another presentation at Fillmore's Commercial Club. Gray announced his intention to assist the community in growth and progress, and spoke of UP's $15 million campaign then underway "for the betterment of Utah." [389] On May 23 Gray made a third presentation at a luncheon held at Salt Lake City's Chamber of Commerce. Mayor Clarence C. Neslen and 61 retail merchants attended the event from six states. At the gathering Gray disclosed UP's plans to develop the economic and scenic resources of Utah. Gray and vice-president Adams then met with high-ranking members of the Chamber of Commerce to inform them that the company was willing to build a $200,000 hotel at Bryce Canyon only if the state would sell them the land or if it were owned by the federal government and then leased to them.

On the same day that Gray made his presentation to Salt Lake City's Chamber of Commerce (May 23, 1923), Governor Mabey returned from a 10-day trip to Washington, D.C. There, a federal road project was discussed that had a bearing on southern Utah's Arrowhead Trail. At a May 14 hearing concerning road projects before Department of Agriculture Secretary Henry C. Wallace, Lincoln Highway Association representatives argued against development of the Arrowhead Trail due to its poor "scenery." [390] Mabey also conferred with NPS officials in Washington, D.C., on how to handle the Bryce Canyon situation. Park Service officials favored a leasing system. "They are against the sale of any land except a very small area upon which a hotel resort is to be built," Mabey later reported. [391]

In response to Gray's firm position on Bryce Canyon development, the Salt Lake City Chamber of Commerce board of governors voted on May 24, 1923, to endorse UP's application to purchase 40 acres at Bryce and to lease the remainder of section to the company. [392] Negotiations were not yet over. Mabey and Oldroyd put off action on UP's application in order to reinspect the school section at Bryce with UP officials. Meanwhile, NPS and UP architects and engineers began surveying building sites and sketching preliminary plans. Confident that the Park Service would approve its developments in Zion and Bryce Canyon, Union Pacific started cutting timber and quarrying stone for its Zion and Bryce Canyon hotels in late May. Major construction efforts on the hotels at Zion and Bryce Canyon (as well as completion of Cedar City's El Escalante Hotel) hinged on the completion of the Lund-Cedar City branch line, which was projected for June. [393] All developments were planned to be ready for the 1924 tourist season. Meanwhile, campgrounds at Zion and Bryce Canyon were available in the 1923 season.

In the fall of 1923, Union Pacific's General Solicitor George H. Smith wrote Carl Gray a letter concerning federal aid for highway construction. Certain roads had already been selected by the State Road Commission for expenditure of federal funds with the approval of Secretary Wallace; others had been designated by the Commission, but still needed Wallace's approval. The total mileage of these roads equaled seven percent of all the roads in the state (1,612.7 miles out of 24,000 miles). The vast majority of funding was to come from the federal government either through the Federal Aid Law or the U.S. Forest Service. In the meantime, the State of Utah began to assume some of the road maintenance tasks formerly poorly performed by local counties in the area of Zion National Park, in order to assure better maintenance of approach roads to the park. Near year's end, Randall L. Jones assured UP's Vice-president H. M. Adams, "The roads next season should be in very good shape and with the maintenance being in the hands of the State Road Commission, there will be not only a decided improvement by the addition of many miles of new construction, but they will undoubtedly be kept in good repair." [394]

Shortly after this communiqué, Jones informed Adams that the Cedar City-Cedar Breaks road was financed in mid-November, and that he now would turn his attention to the Cedar City-Zion road. He later wrote to H. M. Adams,

With no road funds in the State Treasury and very little prospect of getting any in the near future, with the southern counties bonded to capacity and assessing for road purposes the legal limit, it became necessary to look to other sources for funds to build Utah's parks. There was only one source - liberal subscriptions from those interested in the development of the parks - Salt Lake City, Los Angeles, and the towns in the park district. [395]

Toward that end, the State of Utah looked beyond its borders to southern California. In early December 1923, a series of meetings took place in Utah and in Los Angeles to raise funds for road development, particularly for the beleaguered Arrowhead Trail. A party consisting of Randall L. Jones, Governor Mabey, Preston G. Peterson (Chairman, Utah State Road Commission), F. D. B. Gay (Secretary, Scenic Highway Association) and reporters from the Salt Lake Tribune and Deseret News first met with citizens of Parowan, Cedar City, and St. George. Then the whole entourage headed by auto for Las Vegas except for Governor Mabey, who took the train from Las Vegas. At the Los Angeles station he was met by Union Pacific official, M. de Brabant. Also in Los Angeles for the meeting were UP officials H. M. Adams and W. S. Basinger. On December 7, 1923, Mabey and Peterson presented Utah's road problem to the Auto Club of Southern California's Board of Governors. The following day, at the Auto Club's suggestion, they repeated their presentation to the officers of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce. By the end of the two meetings, the two organizations had promised Mabey they would raise $100,000 toward the completion of the Arrowhead Trail through Utah. [396]

There was a very good reason why Randall Jones appeared so eager to assure UP officials that road improvements in southern Utah would take place at a rapid pace. President Carl Gray's commitment to building hotels at Zion and Bryce Canyon had always been contingent on Utah improving the transportation network that served the region. The company was not willing to make a tremendous outlay of capital on hotels - not to mention a new fleet of motor coaches - if it wasn't convinced its concerns about safe and comfortable road travel would be addressed. [397] At the same time, UP had their own headaches: construction of a dependable water supply for developments at Bryce Canyon was proving to be more costly than anticipated, and the company's rights to offer motor transport service between Cedar Breaks, Zion National Park, and Bryce Canyon had yet to be secured. [398] Meanwhile, Director Stephen T. Mather had managed to line up a delightful place for tour buses to stop for lunch, once Union Pacific actually got its tour operations underway.

The Establishment of Pipe Spring National Monument

While Union Pacific officials were negotiating over the purchase and lease of lands at Bryce Canyon just prior to its establishment as a national monument, Director Mather was working in Washington, D.C., to have Pipe Spring established as another national monument. It would be seven long years before a feasible alternate route was available for travelers to go from Zion National Park to the Grand Canyon's North Rim. In May 1923 no one knew if it were even possible to construct such a road or just how and when the means could be found for the undertaking. Thus, the immediate concern for Union Pacific, state officials, and the National Park Service was to improve the existing route from Zion to the North Rim and to make it as pleasing to tourists as possible. Mather envisioned the majority of tourist traffic would traverse the Hurricane-Fredonia route, at least until the Rockville shortcut to Short Creek could be built. The fort and its natural spring water would offer a welcome respite to tour buses and individual travelers, weary from crossing miles of the desolate Arizona Strip. The establishment of a National Park Service site at this strategic location would, however, require more than the usual amount of political maneuvering. Issues of ownership of the Pipe Spring ranch had never been completely settled. The Office of Indian Affairs and General Land Office had refused to recognize Charles C. Heaton's claims to the tract and he had filed a motion for a rehearing on their decision. The creation of the new monument at Pipe Spring called for that problem to be addressed, along with others. To achieve his goals, Mather appears to have solved the problem in a rather convoluted yet successful fashion.

As mentioned earlier, Mather asked Church officials in January 1922 to serve as intermediary between the government and the Heaton family in determining a selling price for the Pipe Spring ranch. Nearly a year and one-half later on May 12, 1923, President Grant wrote to Mather to inform him that Charles C. Heaton had set the selling price at $5,000. The Church promised to subscribe some of the money and to approach the Oregon Short Line (a Union Pacific subsidiary) for additional funds. [399] Grant wrote,

Perhaps my associates may reconsider allowing the Church to subscribe for at least 10% toward purchasing this property, although it hardly seems in line for a 104.church, which is a charitable institution, to be spending money to purchase property to make a present to the United States government. [400]

Mather replied to Grant on May 21 informing him of the urgency of raising the funds within a month so that President Warren G. Harding could sign the proclamation establishing the monument before he left on a trip to the West. His letter ended with the plea, "so please do all in your power to put this pet project of mine through in the next thirty days." [401] Leaving little to chance, Mather also acted to enlist the aid of Lafayette Hanchett, president of National Copper Bank in Salt Lake City. Mather had scheduled a trip to take several congressmen to southern Utah and northern Arizona after President Harding departed the area. It was critical to establish the monument at Pipe Spring prior to President Harding's trip to southern Utah, Mather explained, "so that we can convince the Congressmen who are going to accompany me, and who happen to handle these specific appropriations, that we need funds for its [the fort's] proper restoration." [402] (In fact, the funds to purchase Pipe Spring were not raised in time, but this will be discussed later.) Hanchett offered to do his part while stating, "The preservation of Pipe Springs wakens little or no enthusiasm among non-Mormons, who seem to regard the place strictly as an old outpost of the Mormon Church, and who frankly say it is up to the Mormons to take care of the matter if they wish anything done." [403]

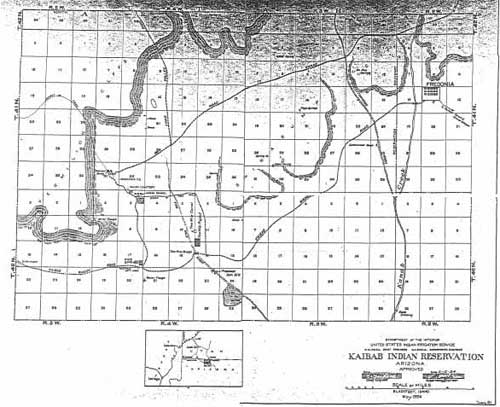

Meanwhile, Mather asked his assistant Arthur E. Demaray to draw up the proclamation, which was completed on May 23. [404] Mather then gave the draft proclamation to Commissioner Charles Burke, Office of Indian Affairs. Burke returned the draft to Mather two days later, disapproving it for lacking a provision by which the reservation's Kaibab Paiute could utilize the waters of Pipe Spring. Mather hastily inserted a clause prepared by Burke and returned it for the Commissioner's signature. Burke signed it on May 28 and returned it to Mather with the following memorandum addressed to Secretary Hubert Work:

The forty-acre tract described in the proposed Presidential Proclamation attached is within the Kaibab Indian Reservation in Arizona. The Indians have no special need for the land, and as a clause has been inserted giving the Indians the privilege of utilizing the waters from Pipe Spring for irrigation, stock watering, and other purposes, under regulations to be prescribed by the Secretary of the Interior, I concur in the proposed action to set the land aside as a national monument. [405]

There were still legal issues to work out over the clouded title to the land. The same week that Director Mather was working to obtain Commissioner Burke's cooperation and support of the monument's establishment, General Land Office Commissioner William Spry sent a memorandum to Assistant Director Arno B. Cammerer about the ownership of the Pipe Spring tract. The memorandum summarized actions related to Pipe Spring and surrounding lands, including those leading up to the creation of the Kaibab Indian Reservation. It stated that Charles C. Heaton's March 3, 1920, application to locate the Valentine scrip on the Pipe Spring tract was rejected on April 15, 1920, "for conflict with the withdrawals and for other reasons. The evidence of assignment from Daniel Seegmiller to the applicants [sic] was not sufficient." On December 10, 1920, Heaton's case "was transmitted to the Secretary of the Interior on appeal and has not since been returned," stated Spry. [406] Oddly, the fact that Assistant Secretary Edward C. Finney denied Heaton's appeal on June 6, 1921, and that Heaton had filed a motion for a rehearing of the case was not brought out by Spry in his memorandum to Cammerer. [407] It is also worthy of note that the date of Finney's denial of Heaton's application - June 6, 1921 - is exactly the same date that Director Mather wrote to Commissioner Burke about his interest in making Pipe Spring a national monument.

On May 29, 1923, Mather transmitted a form of the proclamation establishing Pipe Spring National Monument to Secretary Work. The transmittal included the proclamation, a draft letter to the President recommending its establishment, and three other memoranda: a copy of Commissioner Spry's memorandum of May 23 to Cammerer (cited above), Commissioner Burke's May 28 memorandum (also cited above), and a memorandum from Mather himself. The memorandum from Mather is quoted in full below:

Attached letter to the President transmits form of proclamation for the establishment of the Pipe Spring National Monument, Arizona.

There is attached memorandum from the Commissioner of the General Land Office relative to the Pipe Spring property in Arizona. It will be noted that on March 3, 1920 Chas. C. Heaton and the Pipe Spring L. S. Company filed application to locate the Valentine Script [sic] on the SE 1/4 SE 1/4 Sec. 17, which is the area to be established as the National Monument. The application has been held for rejection for conflict with the prior withdrawals and on December 10, 1920 the record was transmitted to the Secretary on appeal and has not since been returned to the General Land Office.

I have personally visited Pipe Spring several times and realize the desirableness of having this area established as a National Monument for the benefit of motorists traveling between Zion and Grand Canyon Parks. I have interested a number of Utah's representative citizens in this matter and have secured promise from the claimants of the property to sell it to myself and associates for $5,000. It is my intention, when this purchase has been completed, to have the claimants withdraw their application now pending on the appeal in order that the National Monument proclamation may be made effective.

[signed, Stephen T. Mather]

DirectorAt the suggestion of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs a clause has been inserted in the proclamation, giving the Indians of the Kaibab Reservation the privilege of utilizing the waters of Pipe Spring for irrigation, stock watering and other purposes under regulations to be prescribed by the Secretary of the Interior. [408]

Secretary Work transmitted the proclamation to President Harding on May 29, 1923, with the following memorandum, quoted in full:

There is enclosed form of proclamation to establish the Pipe Spring National Monument, Arizona, reserving 40 acres on which are located Pipe Spring and an early dwelling place, which was used as a place of refuge from hostile Indians by the early settlers. Pipe Spring, first settled in 1863, was the first station of the Deseret Telegraph in Arizona. The spring affords the only water on the road between Hurricane, Utah, and Fredonia, Arizona, a distance of 62 miles, which is the direct route from the Zion National Park, Utah, to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. It is an oasis in the desert lands and with the increasing motor travel between the two National Parks, it is highly desirable that this area be established as a National Monument.

I have, therefore, to recommend that you sign the enclosed form of proclamation. [409]

President Harding signed the proclamation establishing Pipe Spring National Monument on May 31, 1923. A copy of Presidential Proclamation No. 1663 establishing the monument and accompanying map depicting the monument's boundary is attached to this report as Appendix II. It states that the monument "affords the only water" between Hurricane and Fredonia, "a distance of 62 miles;" that Winsor Castle was used as a place of refuge from hostile Indians by early settlers; that it was the first station of the Deseret Telegraph in Arizona; and that, "...it appears that the public good would be promoted by reserving the land on which Pipe Spring and the early dwelling place are located as a National Monument, with as much land as may be necessary for the proper protection thereof, to serve as a memorial of western pioneer life..." [410]

The details of the sale and transfer of the Pipe Spring property to the federal government were still to be worked out. [411] While Pipe Spring had been proclaimed a national monument, the Heaton family still owned it, or - in the eyes of the Office of Indian Affairs - they still maintained their claim to ownership of Pipe Spring. Mather worried that the Heatons might not continue caring for the property so he had B. L. Vipond contact the Office of Indian Affairs to investigate the possibility of having the Kaibab Reservation superintendent look after the place to prevent vandalism. [412]

In July 1923 Mather's assistant, Arthur E. Demaray, led a congressional delegation to Pipe Spring in hopes of obtaining funds for the fort's restoration. (Mather was ill at the time and was directed by his physician not to make the trip.) Representative Louis C. Cramton of Michigan, chairman of the subcommittee for Interior Department appropriations, accompanied the group. When they arrived at Pipe Spring on July 1, an angry Charles C. Heaton met them. Apparently, Dr. Farrow had been to the fort at some point prior to this time to check on it, as requested by his superiors. Heaton thought that Farrow had come to the monument to oust John White, his caretaker, and to take over the administration of the site. Neither Heaton nor other local ranchers liked or trusted Farrow, given his six-year history of vigorously defending the interests of the reservation's Kaibab Paiute. Heaton had also received word of the last-minute clause inserted into the proclamation at the insistence of Commissioner Burke giving the Kaibab Paiute the "privilege" of using Pipe Spring water. Heaton feared that if left in charge of the monument, Farrow would take all the water for the Indians. Heaton informed Demaray and the accompanying delegation that he would not sell Pipe Spring unless assured that White would be retained as caretaker. He also told them that he had sold some of the water rights to local ranchers, and that this sale had to be recognized prior to his selling the property to the government. When Demaray told Heaton he could make no such promises, the argument intensified. Representative Cramton then declared he could not accept Heaton's demands and added that, under the circumstances, he would not promise any money for improvements and restoration. Mather's hope that this trip would result in funding for his "pet project," was thus unexpectedly dashed. In late July Mather made a partial concession to Heaton's demands by agreeing to let White and his family continue to live at Pipe Spring until the end of 1923. [413]

The unpleasant confrontation that occurred on July 1, 1923, at Pipe Spring exemplifies the realities and conflict involved in the final process of the sale and transfer of Pipe Spring to the federal government. Government agencies, represented by the National Park Service and the Office of Indian Affairs, had conflicting goals to a great degree. The national monument was established to preserve and interpret the historic site for future generations. The Park Service also had to take into consideration the needs of the traveling public. The reservation was established on behalf of the Kaibab Paiute and its agents had the responsibility for protecting the interests of the Indians. Charles C. Heaton, on the other hand, represented both the interests of the Heaton family and those of other cattlemen with a continuing interest in Pipe Spring water.

Reasons for the Establishment of Pipe Spring National Monument

The historical significance of the Pipe Spring cattle ranch, particularly as it relates to Church history, was certainly a consideration when Mather proposed its inclusion within the national park system. Yet the language of the proclamation and, even more so, the language of related internal correspondence justifying its establishment, seem noticeably more emphatic about its strategic importance as a rest stop for tourists.

When Secretary Franklin K. Lane proscribed National Park Service policy for adding new sites to the system (quoted earlier in Part I), he wrote to Mather that the standards of the national park system should not be compromised "by the inclusion of areas which express less than the highest terms the particular class or kind of exhibit which they represent." [414] Mather reiterated this caveat in his annual report for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1923:

National parks... must continue to constitute areas containing scenery of supreme and distinctive quality or some natural feature so extraordinary or unique as to be of national interest and importance as distinguished from merely local interest. The national park system as now constituted must not be lowered in standard, dignity, and prestige by the inclusion of areas which express in less than the highest terms the particular class or kind of exhibit which they represent... [415]

In the same report he announced the establishment of Pipe Spring National Monument, quoted in full:

The newest national monument is the Pipe Spring in Arizona, established by proclamation of May 31, 1923. This not only serves as a memorial to western pioneer life, but is of service to motorists, containing, as it does, the only pure water to be found along the road between Hurricane, Utah and Fredonia, Arizona. This area is famous in Utah and Arizona history, having been first settled in 1863. In 1870 it was purchased by President Brigham Young of the Mormon Church, and during that year, a stone building with portholes, known as 'Windsor Castle,' was erected to serve as a refuge against the Indians. This building still stands. The relinquishment of certain adverse claims to the lands contained in the monument was secured by the donation of $5,000 for this purpose by a few public-spirited people. [416]

What seems to be rather unusual for the Pipe Spring situation is that neither Mather nor his associates made a case for national importance of the site during the process of its establishment. The importance of its history to the states of Utah and Arizona was acknowledged, but real emphasis was given to the fact that Pipe Spring was "an oasis in the desert," providing a convenience to the traveling public. Ironically, the same natural resource that was responsible for Brigham Young establishing a cattle ranch at Pipe Spring in 1870 - water - was Mather's primary argument for setting it aside as a national monument 53 years later. Only this time, Pipe Spring would be a welcome watering hole for far-ranging tourists rather than for free-ranging cattle.

Another consideration in the era of the automobile was the necessity of a place motorists could refuel on the long distances between the region's scenic wonders. By 1926 the Pipe Spring caretaker would be running a lunch stand and gas station, with Director Mather's blessing. A review of files from the early 1920s led the Park Service's Branch of History in 1943 to make the following conclusion about why the monument was created:

In 1921, Director Stephen T. Mather visited Pipe Spring and expressed interest in its historical associations and its important location between Zion National Park and the north rim of the Grand Canyon. Aside from its historical interest, Director Mather believed the area might be developed as an important stopping place for the sale of gasoline on the proposed highway between Zion National Park and the north rim of the Grand Canyon. [417]

While Mather sought to realize a number of objectives, certainly none was in conflict with any of the motives of other interested parties, save perhaps the Office of Indian Affairs. His desire to work with Union Pacific as a partner has been well documented. His appreciation for Mormon history and culture has been alluded to, and certainly his agency benefited from good relations with the Church and its leadership. President Heber J. Grant had expressed and demonstrated a strong commitment to the development of southern Utah's scenic resources, a cooperative spirit to which Mather may have felt indebted. The establishment of a memorial to Mormon settlers made a fitting "thank you" to the Church and its leadership, while providing a long-overdue acknowledgment of the important role of the Latter-day Saints in colonizing the West (a sentiment that President Harding seemed to share). It is noteworthy, however, that the proclamation never once referred to the role of the Church or its followers at Pipe Spring, stating only that the monument was a memorial to "western pioneer life." One can ponder whether the outcome of Mather's efforts would have been successful had the uniquely "Mormon" aspects of Pipe Spring been emphasized in the proclamation or in official internal correspondence.

By the same token, the National Park Service was indebted to Union Pacific for all its financial investments in southern Utah. (Its development activities at the North Rim of the Grand Canyon were already planned, but took place a little later.) Even if Union Pacific needed Pipe Spring only as a tour stop for as long as it took to build the Zion-Mt. Carmel road, its availability for that time period was important in terms of enhancing the tourists' experience as they visited the region's national parks, forests, and monuments. Finally, Mather's actions to establish the monument certainly rescued the Heatons from a very difficult legal situation and ended the family's controversy of property ownership with the Office of Indian Affairs (although no documentation considered in this study suggests that this was one of Mather's objectives). As a result, Mather's success in having the monument established made quite a number of people happy: the Heatons and local cattlemen, Union Pacific, the Church, the states of Utah and Arizona, local tourism boosters, and last but not least, the National Park Service. Even the Office of Indian Affairs, while it would have preferred to have had all of Pipe Spring for the Kaibab Indian Reservation, won a small victory through its insertion of the water use clause into the proclamation. From the Park Service perspective, the establishment of Pipe Spring was what would be called today the perfect "win-win" situation.

Still, a valid question has sometimes been raised: why a national monument? Why not a state park? It is telling to contrast Mather's push for the establishment of Pipe Spring as a national monument with his initial reticence in the early 1920s to push for the same status for Bryce Canyon. Mather had urged Utah officials to create a state park at Bryce Canyon. (Recall that Mather at this time favored the idea of a state park system that would supplement the national system.) Why was his approach with Pipe Spring so markedly different? The site's significance arguably could have been considered to be of local or regional, rather than national, significance. Its history was related to the expansion of Latter-day Saint colonies from Utah into a neighboring state. It is highly unlikely that many people outside of the two-state area, particularly non-Mormons, had ever heard of Pipe Spring or of the events related to its history. Moreover, the primary resource at the time the monument was established (the fort) was in extremely poor condition, with its two associated buildings (the east and west cabins) in complete ruin.

Yet, as far as we know, Mather never contacted state officials in Arizona to propose such a solution. [418] A state park at Pipe Spring, had it been created, would have accomplished some of Mather's objectives, but certainly not others. It would not have been as attractive an offer to the Heatons, nor would it have solved the legal challenge to their ownership claim within the Department of the Interior. It would not have given the site the level of status afforded it by the federal government, possibly making it far more difficult for Church President Grant to raise the funds (particularly within the state of Utah) that would have allowed its "donation" to the State of Arizona. Creating a state park within the Kaibab Indian Reservation would most likely have been far more problematic than establishing a park unit administered by another federal agency within the reservation. In any event, if Mather ever explored this alternative, no record of it has surfaced. On the other hand, national status for Pipe Spring accomplished all the objectives mentioned earlier, and was a goal completely within Mather's realm of influence to achieve. The addition of Pipe Spring to the national park system makes complete sense within the framework of 1920's regional planning and politics. This historic site was simply one small piece of a very complex puzzle being assembled by many hands. All were seeking to develop the scenic resources and transportation network of southern Utah and northern Arizona for a variety of purposes.

The monument's validity would remain an issue. In fact, in 1932 Park Service officials called into question the status of Pipe Spring as a national monument. A letter of November 8, 1932, from Superintendent Roger W. Toll, Yosemite National Park, to Director Arno B. Cammerer suggested that a "trade" might be made in order to establish Capitol Reef National Monument. During the late 1920s and 1930s, Utah officials lobbied to have what was then called "Wayne Wonderland" made into a national park unit. Roger W. Toll was sent on a reconnaissance mission to determine if the area was worthy of such status. Included in his report to Cammerer, was the following suggestion:

Possible substitution for Pipe Spring

If it is felt that the number of national monuments should not be increased at present, it may be that the people of Utah and northern Arizona would prefer to have Pipe Springs National Monument discontinued and the Wayne Wonderland established in its place. Such a substitution would strengthen the value of the national monuments. Pipe Springs, while valuable as a state historical landmark, seems lacking in national interest, and has but few visitors since it is no longer on a main tourist route. No important event seems to have occurred in Pipe Springs, and there are many more important historical places in Utah and Arizona. The Wayne Wonderland, however, is an important scenic area and seems to have much more national value. Pipe Springs is located in Arizona, a few miles from the Utah line, and is probably of more interest to the residents of Utah and the 'Arizona Strip,' north of the Colorado River, than it is to residents of Arizona in general. [419]

Cammerer's response to Toll's idea of substituting Wayne Wonderland for Pipe Springs is undocumented, so it is unknown if it was given serious consideration. President Franklin D. Roosevelt eventually proclaimed Capitol Reef National Park on August 2, 1937.