|

Pipe Spring

Cultures at a Crossroads An Administrative History of Pipe Spring National Monument |

|

PART III:

THE MONUMENT'S FIRST TEN YEARS

Area Developments

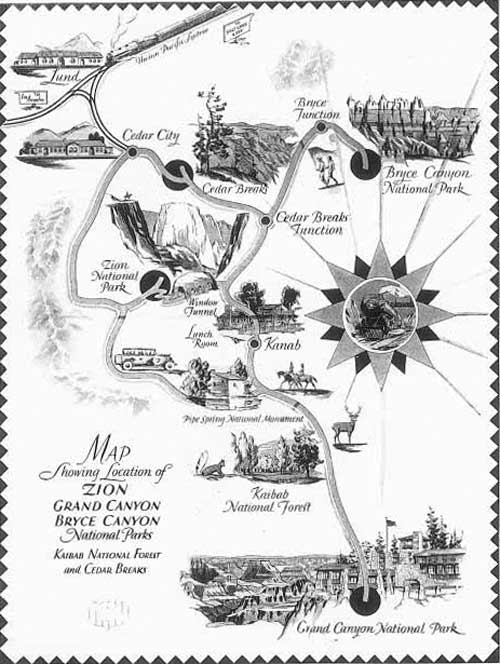

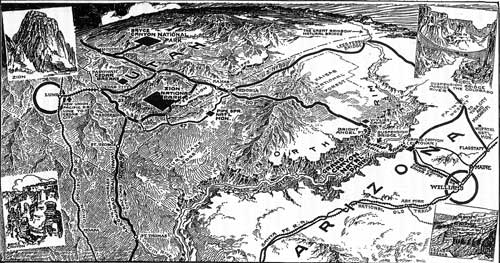

During its first decade as a national monument, from 1923 to 1933, Pipe Spring continued to be affected by developments taking place in national parks to the north and to the south. From 1924 to 1930, Pipe Spring was included on the Utah Parks Company's circle tour of Zion, Cedar Breaks, Bryce Canyon, and the Grand Canyon's North Rim. During those years tour buses regularly made scheduled lunch and rest stops at Pipe Spring. Motorists traveling in private automobiles also traveled the route from Zion to the North rim via the Rockville shortcut, passing by Pipe Spring. The event that proved most significant in Pipe Spring's history, in terms of visitation, was the completion of the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway in Zion National Park.

|

|

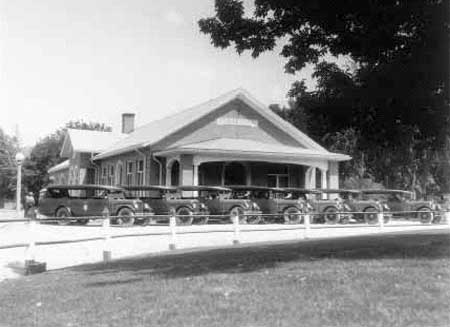

37. Utah Parks Company buses lined up at Cedar

City depot, ca. 1928 (Courtesy Union Pacific Museum, image 8635). |

Zion National Park

On April 9, 1924, Congress authorized appropriations of $7.5 million over a three-year period for construction of roads and trails in the national parks and monuments. The Interior Department appropriation act of March 3, 1925, carried an additional $1.5 million for road construction in national parks. The new funds were immediately available, providing added impetus to the park road program. The Bureau of Public Roads conducted the survey for the Zion-Mt. Carmel road in September 1925. In March 1925 the completion of the 220-foot steel bridge that spanned the Virgin River and the regrading of 15 miles of road beyond the bridge at Rockville shortened the distance from Zion to the North Rim by 30 miles. Tourists and others heavily used the Rockville shortcut for about five years prior to the completion of the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway.

The 1925 season was a significant one at Zion. It was the first highly advertised season, bringing 16,817 visitors - more than twice the previous year's visitation. The Utah Parks Company was ready by May 15 with its new two-story rustic lodge and 46 guest cottages. (The lodge was enlarged and an additional 15 cottages were built in the spring of 1926.) A new fleet of motor buses transported tourists from the railhead at Cedar City to Zion. Transportation to other scenic areas was provided by another subsidiary of Union Pacific, the Utah & Grand Canyon Transportation Company, whose motor fleet was also new. By the 1926 season, visitation at Zion had increased another 30 percent, enabling the Utah & Grand Canyon Transportation Company to maintain daily bus service to the North Rim via the Rockville shortcut.

In fiscal year (FY) 1927 Congress approved base plans to develop adequate road and trail systems in the national parks to modern standards which called for the ultimate expenditure of $51 million, in addition to $9 million previously appropriated. In FY 1928 Congress increased the authorization for park road construction from $2.5 million annually to $5 million annually. [504] It was during 1927 that construction work on Zion National Park's 25-mile road to Mt. Carmel began. This road, with its mile-long tunnel through solid sandstone, is considered one of the greatest pieces of road construction in the country. [505] Named the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway, the highly scenic road was dedicated and opened to general traffic on July 4, 1929, with National Park Service Director Horace Albright serving as master of ceremonies. [506] Utah's Governor George H. Dern presented the formal dedication speech, and a chorus of 30 men from St. George furnished musical entertainment. The new road finally made Zion National Park directly accessible from the east. Visitation rose from 33,383 in 1929 to 55,297 in 1930, an increase of 65.6 percent. [507] Another event that occurred at Zion National Park in 1930 was an expansion of its east and south boundaries through an act of Congress on June 13, 1930, adding 17,900 acres to the park.

|

|

38. Tourists boarding buses at Cedar City, ca. 1928 (Courtesy Union Pacific Museum, image 8634). |

The Grand Canyon's North Rim

For the most part, no development took place at the North Rim of the Grand Canyon until the mid-1920s. Before that time, the vast majority of visitors went to the Canyon's South Rim where both administrative and tourist developments were concentrated. [508] There was a Wylie camp at the North Rim in 1919 (as there was at Zion National Park) but little else. [509] By 1922 stage trips were available every other day from Lund and Marysville alternately, to Cedar Breaks, Bryce Canyon, Zion, and the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. [510] In 1924 plans were tentatively outlined for Park Service facilities that called for development of a water system and construction of several ranger cabins at Bright Angel Point, as well as area road and trail developments. Director Stephen T. Mather favored tourist accommodations at the North Rim to be camps rather than hotels: "This area should be kept exclusively for the benefit of nature lovers and for those who are willing to forego such conveniences as room with bath in order to visit it." [511] It would not remain so primitive.

During FY 1925 surveys were completed for the installation of water development at Bright Angel Point on the North Rim. A ranger cabin and support buildings were constructed. In 1925 visitation to the North Rim was up 110 percent over the prior year. [512] Camping at the North Rim was limited in 1925 and 1926 because water sources had yet to be developed. Poor roads in southern Utah and northern Arizona also played a part in limiting travel to the North Rim. Finally, funds were authorized for use in FY 1927 to develop a water system at the North Rim. Water from two springs was to be collected and pumped to a tank at Bright Angel Point, then distributed by gravity to nearby campgrounds.

In 1927 the boundaries of Grand Canyon National Park were changed, adding 51 square miles of the Kaibab Forest on the north. Also that year, a government contract was awarded to Utah Parks Company to construct a lodge and cabins at Bright Angel Point. The Company had already purchased the Bright Angel Camp from Elizabeth McKee, operating it during the 1927 season. Construction of a new lodge at Bright Angel Point at the North Rim began during the winter of 1927-1928. Leonard Heaton noted in his journal for the month of January 1928, "Large UP trucks pass every day for the Grand Canyon or back for Cedar City." [513] Heavy rain in early February made the road from Zion to Fredonia so soft and muddy that Heaton reported, "Two UP trucks four days on the road from Hurricane, Utah to Fredonia, Arizona, 65 miles." [514] By May Heaton reported tourists were starting to come through on their way to the North Rim, in addition to heavy freight traffic: "Lots of trucks passing hauling freight to the Grand Canyon for the UP. Also lots of tourists coming, on an average of six cars a day." [515]

|

|

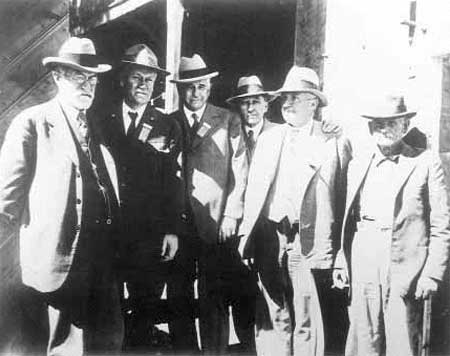

39. Officials at Pipe Spring, en route to the

dedication of Grand Canyon Lodge, September 1928. From left to right:

Heber J. Grant, Stephen T. Mather, Carl R. Gray, Utah Senator William

King, Harry Chandler, and Jonathan Heaton. (Pipe Spring National Monument). |

On September 14, 1928, the Utah Parks Company dedicated its new Grand Canyon Lodge at Bright Angel Point. An entourage of officials, most of whom were important in the creation of Pipe Spring National Monument, stopped at Pipe Spring en route to the dedication of the new lodge. A photograph taken at Pipe Spring that day shows Church President Heber J. Grant, Director Stephen T. Mather, Union Pacific's President Carl R. Gray, Utah Senator William King, Los Angeles Times Publisher Harry Chandler, and Jonathan Heaton, patriarch of the Heaton family and prior owner of Pipe Spring (see figure 39). [516]

At about the same time as the completion of Grand Canyon Lodge, the Kaibab Trail was completed to the North Rim, making it possible to travel by horse from the South Rim to the North Rim in one day instead of the two days previously required. By 1929 the Utah Parks Company added five, four-room deluxe cabins to the lodge complex at the North Rim. During the 1929 season, the Grand Canyon Lodge and cabins were open from May 28 to October 6. The company reported a very successful season in their first year of operation at the North Rim. The opening of the North Rim to tourists was a very important advance. To some, the North Rim was more attractive than the South Rim and much less congested. The road to the North Rim from Utah is of great scenic beauty, through the aspen and pine forests of Kaibab Plateau. Travel between the north and south rims of the Grand Canyon, as well as general park-to-park travel in the Southwest, was soon greatly facilitated by the completion of a steel bridge which crossed the Colorado River at Lee's Ferry. The Navajo Bridge opened on June 15, 1929.

Bryce Canyon National Park

A congressional act of February 25, 1928, increased the area to be included in Bryce Canyon National Monument and changed its name to Bryce Canyon National Park. The new park contained 22 square miles and was overseen by the superintendent of Zion National Park. Under an agreement reached with Union Pacific, the company's private holdings were deeded to the federal government. State lands within the area were exchanged for other lands outside the park boundaries.

Visitation to Bryce Canyon during FY 1929 was 21,997. (By contrast, Pipe Spring National Monument had an estimated 24,883 visitors that year, and Zion National Park 33,383. [517] The completion of the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway had an immediate and positive effect on Bryce Canyon's visitation, which increased in 1930 to 35,982, an increase of 63.5 percent over 1929. [518] All the efforts to improve roads and promote southern Utah's parks appeared to be successful, for Zion's visitation too had more than doubled since 1925. Improved driving conditions, advertising, and the growing popularity of the automobile contributed to a significant increase in the number of visitors to national parks and monuments by the end of the 1920s. While increased visitation to southern Utah and northern Arizona sites had been a chief goal of Mather and Albright, rapidly rising numbers of visitors created additional strain on Park Service caretakers and on scarce financial resources. More people meant demand for more camping space, more parking space, more toilet facilities, and — perhaps most challenging in the Southwest — more water.

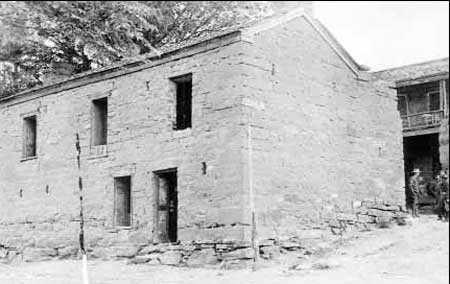

Presenting Pipe Spring National Monument

At the time of the monument's creation in 1923, the Pipe Spring site was visually unimpressive. The fort was in poor condition, particularly the lower building. Its primary associated structures, the east and west cabins, were in total ruin. Moreover, in the eyes of Park Service officials, the landscape was littered with an extensive array of old fences, corrals, and cattle troughs (the latter consisted of both wooden troughs and open, mud-ringed pools of water which served as watering holes). What is now referred to as the old monument road, previously called the Kaibab Wagon Road, had long passed through all of this, but now that Pipe Spring was federal government property, practical as well as aesthetic concerns immediately arose and needed to be addressed. [519]

|

|

40. Pipe Spring fort, ca. 1925. People in gateway are unidentified. (Pipe Spring National Monument, neg. 355). |

First, the Park Service wanted the visitor to the historic site to have a pleasant and memorable visit, as well as a safe one. As monument boundaries were unfenced, local horses and cattle criss-crossing the road to reach watering troughs spelled obvious trouble for motorists. In addition to addressing issues of safety, the Park Service also wanted to make all the sites as attractive as possible. During this period park managers were concerned with making all of its sites within the system "presentable" to the public, as NPS Historian Linda Flint McClelland documents so well in Presenting Nature: The Historic Landscape Design of the National Park Service, 1916-1942. [520] It is true that "beauty is in the eye of the beholder," for while a typical cattle ranch landscape may have appeared practical if not attractive to a cattle rancher, its looks were unappealing to urbanized Park Service officials from Washington, D.C., Union Pacific officials, and to most tourists that hailed from a city of any size. Thus there were two immediate problems to be tackled: 1) the cleanup of the landscape and 2) the restoration of the buildings. Because the first task required only unskilled labor and very little expense, it was the easiest and earliest one undertaken.

The "Boss" Directs First Improvements

The monument was one of many southwestern sites administered by Superintendent Frank Pinkley of Southwestern National Monuments, headquartered from October 1923 through August 1943 in Coolidge, Arizona. [521] Nicknamed "Boss" by the many men who served under him, Pinkley held this position from October 25, 1923, until February 14, 1940. He was in charge of general supervision of 18 national monuments in the Southwest, including serving as custodian for Casa Grande and Tumacacori. The appropriation for general repairs to historic and prehistoric ruins in all the monuments under his care was $5,000 for FY 1925; the same amount was requested for FY 1926.

By 1923, with the exception of three monuments that required a full-time custodian (Petrified Forest, Aztec Ruins, and Casa Grande), all custodians at other monuments served for the nominal salary of $12 per year. Their federal appointments and nominal salary gave them the legal authority to make arrests and otherwise enforce Park Service regulations. [522] During the 1926 travel season, visitation to the southwestern national monuments totaled just over 200,000. [523] With only a few full-time custodians and a dozen part-time and temporary men staffing the monuments, Pinkley reported in 1926 that the work force manning these sites was "totally inadequate." [524] Things would get worse. During the 1929 travel season, the number of visitors to the southwestern national monuments rose to nearly 300,000.

|

|

41. Southwestern National Monument's

Superintendent Frank Pinkley inspecting southwest corner of fort;

undated, ca. 1923-1925 (Pipe Spring National Monument). |

During the summer of 1925, Pinkley set about directing the landscape work at Pipe Spring to make the historic site and its setting more presentable to the public. Local laborers under the supervision of the monument's first caretaker, John White, did the initial work. [525] Work involved neither historical research nor an attempt to recreate the fort's historic period landscape. Rather, changes followed guidelines dictated by Park Service aesthetics and by officials' desire to provide unobstructed views of the fort and its two associated cabins. The fact that the fences, corrals, and troughs were an integral part of the fort's operations as an historic cattle ranch was not considered, only that they were "eyesores" and posed hazards for tourists. (But then, cultural landscapes as an historic resource would not even begin to be a Park Service concern for another 60 years.)

On August 1, 1925, Pinkley described to Director Mather the cleanup operations at Pipe Spring conducted during all of July:

We took out a hundred yards of fence on the line as one approaches from the west. This was a fence made of cedar posts planted as closely as they would stand some eight or nine feet high and they obscured the foreground as one approached the place. We replaced this with a barbed wire fence, which is quite inconspicuous as compared with the other.

We put in a cattle guard at the west entrance to the monument.

The main buildings at Pipe Spring, as you know, have long been used as headquarters for this whole cattle range and the place was all messed up with corrals and fences. We took out a cedar post fence just west of the spring which was spoiling the view to the southwest; a fence around the pools which was an eyesore and is no longer needed; two corrals to the east of the buildings which were in the foreground as one approached from the east; a fence and gate which connected these corrals with the fence around the pools; and the big corrals where the roundups have been held these last forty years and would have continued to be held if we had not removed them. We changed the line of about 200 yards of other fence, throwing it behind trees and bushes and hiding it almost completely.

We rebuilt 100 yards of rock wall around the two pools and graded two sites, one at the east and one at the west end of the pools for automobile campers. We built a terrace wall 30 feet long and from 1 to 3 feet high in line with the front of the big building and in front of the spring. [526]

An interesting aspect to the work revealed by Pinkley in the above report is that the removal of these ranch-related structures was needed not only to clean up the landscape, but also to change the habits of the local cattle ranchers. Given their practical nature and the site's historical use, the ranchers might have been inclined to continue to use any thing left standing. Probably as a concession to Charles C. Heaton, the two main corrals at the southwest corner of the monument were left standing. These had been used up to the time the site became a monument for branding and separating cattle during semi-annual roundups.

East Cabin Repairs; A New Caretaker Is Hired

The restoration of Pipe Spring's three historic buildings would take a great deal of physical effort, a good many years, and considerable funding to accomplish. It was a process that proceeded bit-by-bit, as labor and funds slowly chipped away at a very long list of needs. Even prior to the monument's creation Director Mather was aware that restoration funding was essential to the plans he had envisioned for the site. It was this vision that facilitated his selling the Pipe Spring idea to Union Pacific and Church officials who in turn helped bankroll the property's purchase.

In September 1923, just over one year prior to the Park Service's acquiring title to the Pipe Spring tract, Mather directed Frank Pinkley to go to the site and assess restoration costs. Mather told Pinkley the fort's large wooden gates needed to be rebuilt so the courtyard could again be enclosed, much of the woodwork needed to be replaced, and the roof required new shingles. Since the July 1924 incident between Dr. Edgar A. Farrow and Charles C. Heaton had soured Congressman Louis Cramton on providing restoration funds for the 1924-1925 year, Mather suggested that Pinkley try to solicit money for restoration and for road improvements from Arizona's Governor George W. P. Hunt. [527] Pinkley went to Pipe Spring early the following month (October 1923). After consulting with Charles C. Heaton, Pinkley reported to Mather that he thought the west cabin should be restored first since it would provide experience with local materials and labor. [528] Due to the scarcity of money, restoration of the fort had to be put on hold until the fall of 1924.

On October 15, 1924, Mather was able to get $300 set aside for restoration work at Pipe Spring. Pinkley assigned John White the task of gathering together native building materials for work on the west cabin. During the winter of 1924-1925, White obtained logsandstone to be used in its reconstruction. He also cleaned out 20 loads of dirt from the cabin's two rooms and removed rock that had been dropped in the cabin's chimneys by vandals.

Pinkley evidently changed his mind about wanting the west cabin reconstructed first, for he spent the month of July 1925 at Pipe Spring overseeing reconstruction of the east cabin. [529] As mentioned in Part I, Anson P. Winsor's family lived there while the fort was under construction, reportedly sharing it on occasion with Joseph W. Young who was charged with overseeing the fort's construction. Its use from 1872 to 1886 is unknown. During the Woolley period of occupation (1886-1891), the cabin was reportedly used as a chicken house and stable. [530] The cabin was allowed to deteriorate between 1895 and the time the property was acquired by the Park Service, being used as a cow and pigpen by those who lived at the fort. When Pinkley inspected the cabin in 1924, it was missing its roof, the back wall, and part of the front wall. Using most of the $300 appropriation he had for the monument that year, he had the east cabin reconstructed, using the materials gathered the previous winter by John White. For the roof, pine stringers were used to support peeled cedar posts fitted tightly together. It was then covered with cedar bark and dirt. At the time, funds were insufficient to replace the hand-hewn window and doorframes. These were installed the following year. [531]

|

|

42. East cabin and corrals, ca. 1924 (Pipe Spring National Monument, neg. 936). |

|

|

43. West cabin and meadow, ca. 1924 (Pipe Spring National Monument, neg. 4110) |

Earlier, in the spring of 1925, White notified Mather that he needed additional income and requested a five-year permit from the National Park Service to operate a gas station at the monument. Mather wrote Pinkley that he disapproved of the idea. Pinkley then informed White that while he would not be given the permit, he would be allowed to sell his farm products to tourists. Next, White asked if he could use the ground floor of the upper building to prepare and serve hot lunches to tourists, but it was determined that the floors of those rooms were too deteriorated for such use. Unable to make sufficient income to support his family at the monument, White left the monument in the fall of 1925. [532]

Soon after John White left his custodial job at Pipe Spring, Mather made the decision to offer the position to C. Leonard Heaton, oldest son of Charles and Maggie Heaton of Moccasin. Heaton had worked as a monument laborer under Pinkley at some point during 1925. [533] After attending high school in St. George, Leonard may have attended several of years college at Brigham Young University; when in Moccasin, he worked for his father. [534] At age 24, Leonard Heaton assumed his new position on February 8, 1926, riding to work his first day on a black horse named "Snake." [535] Although he acted as the monument's caretaker, Heaton's first job title was laborer. [536] In addition to pay of one dollar a month, his appointment included permission to operate a gas station and store, a request earlier refused to White. [537] In a 1991 interview, Leonard Heaton stated that the permit was issued and the store was opened in February 1926. While his memory is most likely correct regarding when the permit was issued (which coincided with his hiring), documentation suggests it took a number of months for the small store and gas station to be constructed. In a letter report for the month of April 1925 to Director Mather, Superintendent Pinkley wrote, "Mr. Leonard Heaton is building a service station and lunch stand at the monument. This is a very pleasant stop on the way from Zion National Park to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, but it is a very interesting relic in itself. We hope in time to rebuild this fort and furnish it with old-time Mormon furnishings." [538]

|

|

44. Restored east cabin, undated, probably late 1920s (Courtesy Union Pacific Museum, image 39023). |

The only photographs known to depict the store are taken from such a distance that it is impossible to give a detailed physical description of it (see figure 67). A number of later maps label it as a stone building. In a recent interview with Moccasin resident Grant Heaton, Heaton said he thought the store was about 12 x 16 feet. [539] It appears to have had a rectangular footprint with a flat roof. A 1933 service permit stated the store occupied a plot of land "not to exceed 30 feet square," located south of the fort ponds. That permit was issued to Grant Heaton (rather than Leonard Heaton) for one year at a cost of $3 per year beginning January 1, 1933. [540] Grant Heaton, who was only 15 years old at the time the permit was issued, stated in his interview that Leonard and Edna ran the store and that he only helped them out on occasion. [541]

The arrangement with Leonard Heaton - a nominal salary, a place to live, and a permit to operate a small business - was not particularly unusual for the National Park Service during that period. [542] In fact, the store (or "lunch stand," as Frank Pinkley called it) and gas pump served a real need that Mather had earlier identified when he suggested to President Carl Gray that Union Pacific set up a lunch station at Pipe Spring, and which the latter declined to act upon. As long as tourist traffic followed the Hurricane-Fredonia route to the Grand Canyon's North Rim, a gas station also filled a need of the traveling public.

In a 1991 interview, Leonard Heaton described his first meeting with Director Mather. He believed it took place in 1925, after Mather had taken his teen-age daughters on a trip to Yellowstone National Park. Heaton recalled of their meeting: "Well, he was just an ordinary man. He didn't seem to show any superiority about anyone else... [and] he was easy to talk to. He told me what he wanted to do but he said to use your best judgement in putting it back like it was." [543] The last time Leonard Heaton saw Mather was in September 1928, when the director was traveling through the area for the September 14 dedication of Grand Canyon Lodge at the North Rim. On November 5, 1928, Mather was stricken with paralysis. Due to ill health, reportedly "brought on largely through his steadfast devotion to his work," Director Mather resigned his position on January 8, 1929. [544] After 15 years of service to the National Park Service, he died on January 22, 1930, at the age of 63.

Horace M. Albright was appointed Mather's successor, serving as director until August 9, 1933. Even before Mather's death, Heaton had more contact with Albright than with Mather. Albright's early instructions, in Heaton's words, were as follows: "As custodian now, your first job is the traveling public and then your next job is to keep the place clean and presentable. Then if you've got any time left, it's yours." [545] Heaton would have little spare time, because in 1923 Mather and Pinkley started to put together a list of jobs to be undertaken at Pipe Spring which only grew longer after he was hired.

Repairs to the Interior of Pipe Spring Fort

In early 1926, after the appointment of Leonard Heaton as caretaker, Pinkley turned his attention to restoration needs of the fort. Repairs to the fort's interior were made first. The ground floor of the lower building had two rooms. The east room was in poorest condition. The floor was dirt, little plaster was left on the walls, and there was no glass in the window. Heaton replaced the glass in 1926. In early 1926 Pinkley also instructed Heaton to replaster the walls of the east room (which Heaton did later that year) as well as the walls of the west room, traditionally referred to as the "spring room."

In his report to Mather for FY 1926, Pinkley reported on activities at Pipe Spring: "Repair work here is going on at the rate of about $500 per year and we have already made a great improvement in the looks of the place." [546] In a later report made at the end of the 1926 travel season, Pinkley wrote to Mather, "Local interest is high here and all the neighborhood is interested in the repair and restoration work." [547]

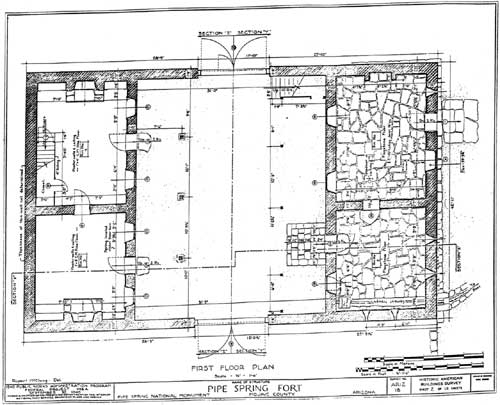

The spring had not flowed into the spring room since its diversion out of the fort by Edwin D. Woolley, Jr., in the late 1880s. It had originally flowed under the floor of the west room of the upper building, across the courtyard, then into the spring room. The cooled room was used during the historic period for making and storing cheese and butter. The restoration of spring flow into this room was thus linked to the condition and repairs required in the upper building. Heaton worked on this project over the winter of 1927-1928, reporting to Pinkley on March 1, 1928, "I have just completed the work of finding the [spring] water and getting it to run through the lower house. It is about three times more work than I thought it would be." [548]

The ground floor of the upper building also had two rooms (what are now the parlor and kitchen). Its floors were in very deteriorated condition, particularly those in the west room. Moisture from the spring that passed under the ground floor had wreaked havoc on its joists and floorboards. When Heaton removed these floors in August 1926, he found water standing on the ground beneath them. He believed that if he redirected the spring water across the courtyard and into the lower building, this would solve the moisture problem of the upper building. He proceeded to restore the spring flow into the spring room by using a two-inch pipe to conduct the water into the room where it entered a two-foot square concrete box. It exited the box into a wooden trough in the room. From the spring room it flowed into a rock-filled ditch which carried it to the ponds. [549]

|

|

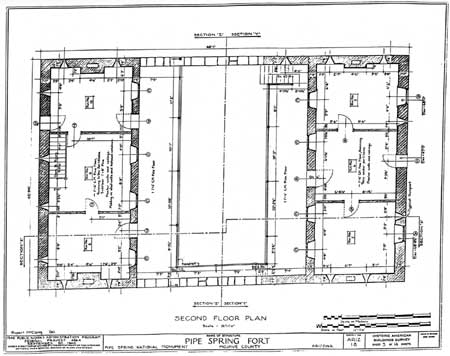

45. Floor plans of the Pipe Spring Fort, 1940 (Courtesy NPS Technical Information Center). (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Because he thought he had solved the moisture problem, Heaton made no attempt to waterproof the kitchen and parlor floors when he replaced them. He simply replaced them with tongue-and-groove pine boards that he nailed to new 2 x 8-inch joists. No measurements were taken of the floor as it was removed since it was one installed by Charles C. Heaton in 1910 (most likely due to earlier moisture problems). As it turned out, moisture problems would be a recurring problem in the upper building's first floor, particularly in the parlor.

Floors proved to be less problematic in the lower building. After the Park Service acquired the Pipe Spring fort, there was uncertainty over whether the original floor of the east room of the lower building had been wood or stone. (This room would later serve as Custodian Leonard Heaton's office for many years.) In 1926, because of the absence of a sill, Pinkley suspected the original floor was stone and directed Heaton to lay a rock floor, which he did during March and April of 1927. [550] (Eight years later Florence Woolley recounted there had been a wood floor when she lived at the fort.) The west (spring) room, on the other hand, retained much of its rock flooring. Only a few rocks were missing several feet from the north wall. Heaton and his father, Charles, replaced these in March 1927. The rock used to replace or repair the floors of both rooms came from Bullrush Wash, located seven miles south of the monument. [551]

The only part of the fort in fair condition was the second floor of the upper building. While it had some warped floorboards and its walls were in need of plaster, its condition was far better than the building's ground floor. It contained three rooms, two of which (the center and east rooms) were created by the addition of a partition in about 1874. [552] The floors and the wall plaster were thought to be original, according to Leonard Heaton. [553] This area had only to be cleaned before it could used. Once Heaton had replaced the floors of the ground level of the upper building, the entirety of the upper building was useable as living space.

In June 1926, probably just after the combination store/gas station was built (and just in time for the busy tourist season), Heaton married Edna Robertson of Alton, Utah. Leonard and his 18-year-old wife made their first home in the fort. The couple moved to the fort "with a horse, two dogs, table, no chairs, a few dishes, and bedding," Heaton later recalled. [554] Precisely where they lived in the fort varied from time to time, depending largely on the condition of the fort's various rooms. The upper building was in far better shape than the lower one, thus was the couple's first living area. Heaton later recalled,

We lived in the upper building because the lower building wasn't fit to live in. It was just used as a camp house and the porch on the south side is [was] torn out, and the partitions of the walls upstairs had been torn out to make [camp fires]... campers used to come in there in the winter time and they would go and knock a board out rather than go and cut a piece of wood. ...And when I got the lower building back into shape, we moved from the ground floor of the upper building into the second story of the lower building. [555]

Leonard's younger brother, Grant Heaton, spent quite a bit of time at the fort as a youth in the late 1920s and early 1930s. By this time, Heaton had repaired the floors of the first floor of the upper building and the family was able to temporarily expand their living area, for Grant Heaton recalled in a 1997 interview that Leonard and Edna slept in the west room of the upper building's ground floor (now the parlor). [556] The east room of that level was presumably used as the kitchen. According to Grant Heaton, when the family lived in the upper building, the three upstairs rooms were the children's bedrooms. Leonard's office was in the east room of the ground floor of the lower building. The west room (the spring room) was used for storage and as a "cold room." [557] The living arrangement changed in early 1930, with the family moving to the lower building.

At the time the National Park Service acquired Pipe Spring, the second floor of the lower building was one large open space, missing two of its interior partitions. The existing walls needed plaster and a number of floorboards were badly warped and needed to be replaced. Due to budget constraints, it would be another three years before Heaton could do anything with this area. In December 1929 Heaton hired a laborer to plaster the walls. In January and February 1930 he rebuilt the two missing partition walls. In early March Heaton reported to Director Albright,

We have moved into the upstairs of the lower house this month and find it much more agreeable and pleasant. Also I am glad to say that the upper house will be opened for the people to go through and see this year, with the exception of the west upstairs room which I intend to use to keep some of my things in. [558]

In November of that year, Heaton reported to Pinkley, "I am getting along pretty good with the repair work this fall; will have practically all of the repair work on the main building [fort] done this month." [559] The Heatons continued to live in the upstairs rooms of the lower building and did so without electricity. During the summer of 1933, Leonard Heaton asked Pinkley for permission to install electric lights in their living area of the fort. [560] Pinkley said there were no funds that year to purchase a light plant (electric generator) and doubted the Heatons wanted to go to that expense personally. It is doubtful that the family ever had electric power while living in the fort.

Floods would plague Leonard Heaton and family throughout his years of monument caretaking. Heavy rains, usually in August and September of each year, created floods that cut a wide, diagonal swathe through the monument from its northeast to southwest boundaries. Below is an undated photograph of one such flood, probably taken either in 1926 or 1927 (prior to the first replacement gates being hung on the fort). The tiny figure in front of the fort may be Edna Heaton with what appears to be a line of laundry hanging between the fort and east cabin.

|

|

46. Flood at Pipe Spring National Monument, ca. 1926-1927 (Pipe Spring National Monument). |

Repairs to the Fort Exterior and West Cabin

During Frank Pinkley's July 1925 visit to Pipe Spring, he directed Heaton to begin certain work on the fort's exterior. Mather had wanted the great gates entering the courtyard to be replaced, but before that could be done the stonework that had once surrounded the gates needed to be rebuilt. Heaton and his father Charles began restoring the stonework for the courtyard gates in February 1928, completing the east gate reconstruction in March. [561] Work on the west gate began in late April and was presumably finished in May. [562] Grant Heaton was about 11 years old and living at the fort at the time. He remembered watching the older men work on the stonework, using two 12 x 12-inch beams to hold the rock in place. The father and son had found and used the original stones stacked neatly near the fort. [563] In June 1928 Heaton reported, "The old fort here at the monument is beginning to look inviting now as we are getting it pretty well cleaned up and fixed up." [564] In August 1928 Leonard Heaton completed and installed three of the four gates. [565] The fourth gate was presumably hung shortly thereafter.

Pinkley had also directed Heaton to repair or replace the verandas on the upper and lower building. The one on the lower building was in especially poor condition. Heaton began work on the south veranda as soon as lumber arrived in September 1926 and completed work by April 1927, replacing everything except the center support post. He also replaced missing balusters and the flooring of the north veranda, but retained the original floor joists. [566]

|

|

47. West cabin ruins, ca. 1924 (Pipe Spring National Monument, neg. 3585) |

|

|

48. Landscape and view of meadow and west cabin, ca. 1924 (Pipe Spring National Monument, neg. 4055). |

The two-room west cabin, built in 1870 to house the workers who constructed the fort, is believed to have been used later by cowhands working at the Pipe Spring ranch until the mid-1890s after which it probably stood vacant. By the time the Park Service acquired Pipe Spring, the cabin had no roof and only partial walls. [567] It was not until 1929 that Heaton was given the job of reconstructing the west cabin. For the most part, Heaton reconstructed the cabin based on Pinkley's ideas. The walls were rebuilt to their original height, repointed, and window frames were installed. Pine stringers were used to support thecedarpoleroof covered with cedar bark and dirt. On July 20, 1931, the west cabin roof beam broke and part of the roof caved in, requiring repairs.

Correspondence from March 1930 indicates that some consideration was given at that time to erecting two Park Service-designed buildings at Pipe Spring, neither of which was constructed. Zion's Landscape Architect Harry Langley drew up plans for a tool and implement shed and a comfort station. Langley conferred with both Zion's Acting Superintendent Walter Ruesch and the Park Service's Branch of Planning and Design in San Francisco about the matter, advising that native stone be used "with as little dressing as possible and set up with plenty of mortar in a very irregular manner." [568] The rustic style described by Langley, which was highly characteristic of the period, was a far cry from the comfort station ultimately built at Pipe Spring during Mission 66, discussed in a later chapter. Why these two buildings were not constructed after the initiation of public works programs at Pipe Spring is not known. There simply may have been insufficient funds to address more than the monument's most pressing needs. Visitors continued to use pit toilets for years, while Heaton eventually constructed his own storage shed for tools.

So Much To Do, So Little Help

For the most part, Heaton seems to have kept busy with restoration and repair tasks assigned him by Superintendent Pinkley. On occasion, he completed his list of jobs and had to await further instructions. In early September 1929 Heaton reported, "I have not done anything on the monument the past two months, hoping that Mr. Pinkley would be up here and help plan what is to be done this year." [569] Heaton had certainly not been idle for the two months, since the summer of 1929 appears to have been one of the busiest ever at Pipe Spring in terms of visitation.

Congress finally approved funding for the custodian's position at Pipe Spring for fiscal year 1932; it took effect July 1, 1932. Beginning then, Heaton was paid $75 per month. [570] He had no staff, even seasonal, until 1953.

In addition to special projects assigned to him by Pinkley, routine work for Heaton by the 1930s, as well as in later years, included the following activities: trap setting, bird banding and record keeping; sweeping the fort and cleaning its windows (a constant chore, thanks to a "dirty west wind"); constructing or cleaning out irrigation ditches; watering vegetation; routine building maintenance; controlling weed growth (foxtail, milkweed, wild morning glory, thistles); tree planting and trimming; cutting dead trees; raking leaves and trash; cleaning fort ponds; journal keeping; writing monthly reports; gathering and pressing plant specimens; cleaning out pipelines to springs; cleaning out cattle guards; trapping gophers (who ruined the meadow and irrigation ditches, and ate tree roots) or plugging up their holes; replastering fort walls and ceilings when old plaster fell down; maintaining the monument road (hauling gravel, filling holes, grading); clearing the road of snow; cutting up firewood for campground or monument use (or hauling it from local sawmills); hauling coal from local mines for fuel; keeping museum collection records; maintaining or repairing the Park Service truck; preparing cost estimates for rehabilitation and other projects; keeping track of expenses; preparing fire reports; cleaning the camping areas; and last but not least, giving guided tours of the fort. Heaton also often came to the aid of motorists whose cars became stuck in mud holes on the abysmal approach road to the monument.

For many years, Heaton regularly worked six days a week for the monument. In addition, Heaton was active in local church and community activities. He usually tried to take one-half or all of Sunday off to attend church or to tend to personal chores. However, at least in 1932 Heaton reported, "In the summer my wife and I take turns in showing the visitors [the fort] on Sunday, that is she goes to church one Sunday and I the next." [571] The Heatons also had a farm in Alton, Utah. Leonard used most of his approved leave from the monument to plant or cultivate wheat there. He was also heavily involved with the Boy Scouts of America, and sometimes took leave to attend their official gatherings. From time to time, Heaton recruited the boy scouts to do small jobs on the monument such as weeding, paying them $2.50 per day. The boys used the money to attend July summer camp.

In addition to maintaining the monument and tending their store and gas station, Leonard and Edna Heaton began raising a family that grew over the years to number 10 children, seven boys and three girls. Five children were born between June 1927 and April 1934 (Maxine, Clawson, Dean, Leonard P., and Lowell); two more were born in 1936 and 1939 (Sherwin and Gary). The last three (Olive, Claren, and Millicent) were post-World War II births. [572] All of the children were brought up on the monument, with exception of the years the Civilian Conservation Corps camp was at Pipe Spring (1936-1940). During those years the family lived in Moccasin. [573] The children attended elementary school in Moccasin and later, high school in Fredonia. Years later, a proud father wrote that seven of the children attended college, two served in the Korean War, and five went on Church missions. [574]

Heaton had little or no money to pay for help for much of his long tenure at Pipe Spring. Members of both his immediate and extended family were recruited to help with some of the day-to-day tasks. Edna Heaton in particular helped out with giving tours, as did many of the children as they grew older. Leonard Heaton often expressed dismay in his journal whenever visitors (or worse, a surprise visit by Park Service officials) caught him in dirty or disheveled clothing while performing routine chores. He once wrote, "I try to be halfway presentable when doing outside work to take the visitor through the fort." [575] As hard as the outdoor monument work was, Heaton far preferred physical labor to working in the office writing reports or filing correspondence, chores he distinctly disliked. Edna often helped out with the filing, keeping museum collection records and helping her husband prepare plant specimens.

The summers were always a very busy time for the Heatons — maintaining the monument, supplying and running the store and gas station, in addition to taking care of personal chores (his farm in Alton, fruit trees and gardens at Pipe Spring, household tasks, and large family). The winters, on the other hand, could get boring. In December 1932 Heaton reported "the worst blizzard that I have ever seen in this country raged, causing death and misery to many birds and animals and much discomfort to us humans." [576] During that month Heaton wrote headquarters,

I find that I have got more time than I know what to do with on my hands this winter and I am going to ask you to give your opinion on some of the things that I have thought of to do here, not only to keep me at work but to make the place more attractive and educational. A few of my ideas are as follows:

1) Fixing up the lower east room of the lower house for use as a registering office and [with] literature of the Monument, also having some of the relics on exhibition in this room.

2) Label all of the furniture as to when it was made and who now owns it.

3) Make hitching racks or tie posts for the horses instead of letting horsemen tie [them] to the trees.

4) Collect plants and insects found on the Monument, giving them the common and scientific names.

5) Make a nature garden of all plant life with signs telling of the kinds of plants.

6) Make a lookout point on the top of the hill back of the Fort showing the interesting places in the development of this country.

7) Have a museum of the live reptiles to be found on the monument.

8) Make a sign of shrubbery, 'Pipe Spring National Monument,' for the airplanes so they can locate this place while flying past. [577]

(This last item suggests the custodian might have been suffering from a sense of neglect, as few visitors - including official ones - stopped by to see the monument, partly due to the distance of the site from U.S. Highway 89.) Heaton assured Pinkley there would be very little cost involved in these projects as he planned to use materials on hand. He wrote that with few visitors, there was little work for him to do and he would enjoy doing these projects. The conscientious custodian added, "Another reason that I want to do it is that when a man gets a government job it is said he can lay around and do nothing. I don't want it said that I did not try to earn the salary that the Government is paying me for staying here." [578]

As a rule, the workload was far heavier in the summer than during the winter. As the weather worsened, very few visitors came by the monument. Less seems to have been done by either the Indian Service or Mohave County road crews to maintain the roads once the travel season ended, making travel conditions over the winter worse than usual. Heaton tried to keep the fort clean and to stay warm in his office, located for many years in the east room of the lower building's ground floor. During this time he usually read or wrote in his journal (often expressing boredom during the winter months), trapped birds, updated bird and museum records, maintained the monument road, repaired museum furnishings, worked on woodwork and floors, or painted inside areas of the fort. The arduous work of cleaning out irrigation ditches and watering vegetation could begin as early as February each year, depending on the weather. Winter brought the area's children a new recreational opportunity: children skated on the meadow pond when it was sufficiently frozen.

Heaton worked very hard to learn as much as he could about the natural history of the area, both for the purpose of sharing this knowledge with visitors and in order to keep official monument records. Heaton faithfully recorded bird sightings in his journal. [579] Heaton also noted numerous reptiles on the monument. [580] Monument reports over the years have many references to finding rattlers on the monument, particularly during the driest months. In July 1931 Heaton reported, "The rattlesnakes seem to be taking a liking to this place this summer, as I and others have killed some on the monument, and some of them are [as] large as I have ever seen, one having 14 rattles and a button, and measuring over three feet long." [581]

In addition, Heaton studied the monument's plant life, seeking outside professional assistance in identifying any kinds of plants he was unfamiliar with. He often sent specimens to Boyce Thompson Arboretum in Superior, Arizona, for identification. As Heaton became more familiar and appreciative of the area's native plants and animals, he also became increasingly protective of those on the monument. His resolve to "preserve and protect" both natural resources and cultural resources would be severely put to a test after the Civilian Conservation Corps camp was established at Pipe Spring.

The job of tending to the monument as well as trying to make a living on the side could be quite a juggling act for Heaton at times. He reported to Pinkley in June 1932,

Just a line to let you know that I am still at the place and trying to take care of it and do the farm work and make a living. Have been spending most of my time getting in crops and gardens and have somewhat neglected the care of the fort, but I am about through with the farm work.... There has not been very many people here this month. [582]

The Heatons' Store, Gas Station, and Lunch Stand

The Heatons' little store and gas pump were situated on the south side of the old monument road, directly below the fort and its ponds. [583] The newlyweds ran the service station and store "for about five years," Leonard Heaton told historian Robert Keller in 1991, suggesting he had been given a standard five-year permit to run their business. [584] During this period it was the family's primary source of income. [585] From all accounts, Edna was as involved in running the store as Leonard, making and serving sandwiches and attending to tourists' needs. [586] Gasoline was hauled in from Cedar City in 55-gallon iron barrels. Supplies to stock the store were also bought in Cedar City. Heaton later recalled that the dirt road that passed by the monument had very little travel at first, "maybe one a day on average." [587] Travel slowly increased over time, reaching its peak in 1929, with most visitation occurring during the summer months. From the small number of cars passing by the monument, routinely reported by Heaton, it is hard to imagine that individual traveling motorists could have generated very much income. It would have been the lunchtime stops by the Utah Parks Company's tour buses that provided the Heatons' "bread and butter."

Tourists were not the only people to patronize the little store, however. The Kaibab Paiute from nearby Kaibab Village, few of whom had automobiles to drive to Fredonia or Kanab, also came to the Heatons' store at Pipe Spring to buy groceries and candy. In fact, recent oral interviews with two tribal elders suggest that visits to the store were their earliest and strongest memory related to the monument. Born in 1921 and a little boy at the time the store was at Pipe Spring, Kaibab Paiute elder Warren Mayo remembered the store. Mayo smiled as he spoke of trips to the store he had taken long ago with childhood friends to buy candy, one of whom is another tribal elder, Leta Segmiller. [588] Segmiller, born in 1925, also recalled visiting the Heatons' store as a little girl. In a 1997 interview conducted by ethnographer David E. Ruppert and the author, Segmiller remarked,

...it was just across from the fort they had that gas station and that store there. And my uncle and I used to go down there [in his car].... That was in 1931, when I was about six years old, that he used to take me down there to buy crackers and candy and all those junk food. That's when I knew there was - he used to tell me about it, that there was a fort there, and that the white man built [it] to defend themselves. He used to tell me that. [589]

Segmiller laughed as she spoke of the store. She was asked if she had visited the store very often and replied, "Yeah, we used to go down there all the time, because we could buy things there to eat. They had mostly everything in there, so we wouldn't [have to] go to Fredonia or Kanab." [590] She also recalled,

And they also had that old-fashioned gas pump that used to stand in the front [chuckles]. People used to buy gas there then, you know, 'cause it was so far to Kanab from here, and Fredonia. So that was good when they had that gas there for the cars. You didn't have very many cars. You know, very few people owned cars around here then. [591]

Segmiller was asked if she ever went inside the fort when she was a little girl and, if so, did she remember anything displayed? She replied:

Well, he had the grinding stones, and all those little things that go with it. And I think the reason why the [Indian] kids didn't go there was because he had skull in there - you know, an old skull that used to sit in the window. And I went in there with my uncle twice, because he said I needed to see what was in there, when I'd keep asking him about the water. And he showed me where the water was coming from, that was flowing out [of the spring]. And I would never go back in there myself, because there was a skull sitting in there. You know the Indian people are not supposed to associate with old skulls — you know, Indian children, when we were little. And I used to be scared of that, and I thought maybe I'd have nightmares, if we, you know, continued all the time to go down there.

.... Oh, they didn't want us to go there, because they said that the white man took the skull out of the ground, or robbed the Indian out of his head. You know, stories like that, so we would [not] go in there.... There were displays, you know, along the wall of the fort, and you could see all the things like old bowls. I always wondered what happened to those Indian bowls they had in there. [592]

Segmiller wasn't the only one who remembered seeing the skull in the fort as a child. In the mid-1970s, when she was middle-aged, Segmiller worked briefly at Pipe Spring demonstrating traditional Paiute crafts. She was hired by the Park Service to do so, along with another Kaibab Paiute woman, Elva Drye. Drye too was haunted by childhood memories of the skull in the fort window, according to Segmiller:

....when me and Elva were working there, we went up there and Elva [was] talking about that skull [laughs], you know, [about] how scared she used to be. She said, 'I don't want to go in there, because there's a skull sitting in the window.' So we went up there, and it wasn't in there then. They must [have moved it] because when Mr. Tracy — she was asking Mr. Tracy about the skull. He said he didn't know where it went to. They were like that. [593]

Segmiller was referring to Superintendent Bernard Tracy, who oversaw the monument in the 1970s.

Pipe Spring as A Gathering Place

Pipe Spring has served as a gathering place at many different points of its history. Before and after becoming a national monument, it was a natural gathering place for ranchers. For a number of years after the creation of the monument, cattlemen held meetings at Pipe Spring, such as the one Leonard Heaton noted in a 1930 report to Pinkley: "August 24th, the cattlemen of this region met here to discuss their range problems as to cattle thieves, cattle sales, and etc. They brought their wives and we had a fine crowd." [594] The following year, Heaton reported: "Our visitors this month have been mostly cattlemen and riders gathering cattle for sale: there have been about 40 men here the last few days handling about 3,000 head of cattle. It sure seems like the good old cattle days [to] have them back." [595] Heaton reported the low spirits of cattlemen that October 1931, due to low prices and "not many buyers." In August 1932, 16 Arizona Strip cattlemen met at Pipe Spring to discuss "their troubles and the range conditions." [596] Similar meetings were held throughout the 1930s. Heaton seemed to look forward to the fall cattle roundups. Heaton wrote in September 1932, "The cattlemen are now gathering the steers for sale and in a few days this place will be alive with cowboys and cattle, reminding one of the old days when Pipe Spring was a cattle ranch." [597]

The year 1933 was the first ever that Heaton could recall the region's annual fall roundup not being based at Pipe Spring. Usually cowboys rounded up several thousand head of cattle each fall, camping at Pipe Spring the last three or four days of their effort to get steers to market. That year ranchers had to graze their cattle on other parts of the range, the grazing was so poor in the area. In October Heaton reported that only 100 or so were at Pipe Spring and that "they were cattle that are pastured [in the area] most of the time." He mused that the corrals in the monument's southwest corner "will soon be all that will be left to remind us of what was once a common sight here in the past." [598]

The monument provided a congenial atmosphere for social gatherings. In October 1931 the Young Men's and Young Women's Association of the LDS Church held a Halloween party at the fort. Heaton reported on the success of the event, which had 67 attendees: "Whites and Indians all joined in and had a very good time.... After all the 'spooky' places were visited, we all met in the upper house and danced and ate watermelons." [599] This is the only Halloween party reported to have been held at the monument. On May 20, 1940, Heaton reported the Stake M Men and Gleaner Girls had a moonlight party and supper at the monument. Summer outings by boy scout troops and Beehive Girls from Kanab, Fredonia, and Moccasin were also common through the years. [600] School groups often made outings to the monument over the years, especially toward the end of the school year. Most children came from schools in Kanab, Fredonia, Moccasin, Hurricane, and Short Creek, but at times they came from as far away as St. George. The Kaibab Indian Reservation's school children also made outings to Pipe Spring. School groups usually toured the fort, picnicked, and/or played ball while at the monument.

Numerous other social groups, as well as Church and civic organizations, held outings at Pipe Spring throughout its history as a monument. Heaton reported that during the month of July 1933 eight parties were held at Pipe Spring with a total attendance of 171. [601] Group picnics, dances, chicken roasts, barbecues, and swimming parties were common. The site was also frequently used for family reunions over the years. Also quite common (particularly in the 1940s and 1950s) were Easter weekend outings at the monument. [602] On May 17, 1941, Heaton reported a group of men and boys from Kanab Stake "came out to get acquainted with early history of their ancestors that settled southern Utah and northern Arizona." [603] Many people had family ties either to the site itself or to the area, and coming back reminded them and their children of a shared history. Others enjoyed the old buildings, the ponds, and the shade of large towering trees. These had long been there. What was much newer by the later 1920s was the absence of fencing, corrals, and water troughs from the immediate fort area and the growing expanse of green irrigated meadows, gardens, and fruit trees.

The Greening of Pipe Spring

Under the care of Leonard Heaton, the 40 acres that comprised Pipe Spring National Monument was quickly being transformed from a cattle ranch into a little Garden of Eden. The Park Service's 1925 removal of landscape features associated with cattle ranching was just the first of many landscape changes that took place at Pipe Spring after it was made a national monument. In fact, Leonard Heaton's tenure as the monument's caretaker was just the beginning of the gradual "greening" of Pipe Spring. While a certain amount of both native and introduced plant growth had always been associated with the presence of the springs and ponds at the site, it was only after the site became a monument that planting and irrigation significantly increased. Prior to that time, water had been used primarily for stock-watering purposes and for domestic consumption. At an unknown date, the Heaton brothers (presumably during their ownership) constructed a pond "just north of the present public campground," Leonard Heaton wrote ca. 1945. [604] Built on sandy soil, Heaton reported, it was unsuccessful as a reservoir, for water "soaked out through the bottom." [605] In 1926 and 1927 two new ponds (referred to as the upper and lower meadow ponds or pools) were constructed southwest of the fort by Leonard Heaton, apparently with the approval of Mather and Pinkley. [606] They were gravity fed by water from tunnel spring. Grant Heaton reported in 1997 that Leonard built these to irrigate his garden. [607] Water flowed by gravity to a large grassy meadow where Heaton pastured his livestock, south of these ponds. Heaton's main garden, kept with permission from the Park Service, was located just below the irrigated meadow. (The Heaton brothers' pond and the upper meadow pond were both done away with - or as Heaton put it, "leveled off " - by the Park Service in 1932. [608] The ponds' removal coincides with a severe drought in the region as well as with a highly sensitive time of water negotiations between the Park Service and the Office of Indian Affairs, described in Part IV.)

Grant Heaton reported that Leonard and Edna kept horses, a milk cow, some sheep, chickens, ducks, and geese. [609] In fact, in January 1931 Heaton reported that he had 220 chickens. [610] From time to time, even a few young deer could be found living on the monument. [611] A small corral, barnyard, and barn were located northwest of the meadow ponds, just below the monument road. The Heaton family's two chicken houses, originally located east of the meadow, were eventually relocated to a more remote site near the monument's southern boundary, east of the two main cattle corrals. [612]

In early 1926 Heaton planted a few peach trees and some gooseberry and currant bushes on the south side of the field and around the corrals. Later that year he planted more fruit trees and some grapevines. In the spring of 1927, Heaton set out 54 apple and plum trees south of the fort and 25 elm trees to the west along the fence south of the monument road. He also planted 500 grapevines. [613] The main spring provided an ample supply of water which Heaton took full advantage of, cultivating and irrigating as much of the land encompassed by the monument's boundaries as the Park Service would permit.

Other landscape changes took place over the winter of 1927-1928. In December 1927 Heaton worked on improving the approach road west of the monument. [614] Another change related to the safety issue of livestock crossing the old monument road to reach their watering holes. For many years the main troughs and watering holes had been located north of the old monument road and due west of the fort. Grant Heaton reported that cattle for a 10-mile radius would water there. [615] In March 1928 Leonard Heaton reported a change: "The cattlemen have made the water pond south of the road, so the cars will not be bothered by cattle on the highway this summer." [616] In August 1928 Heaton repaired the monument's south boundary fence, which also helped to keep out livestock.

Weather conditions, motorists, and auto campers also made their mark on the landscape. Heaton reported in March 1928 that with the arrival of spring weather, he had 28 campers and an average of 12 cars passing each day. Spring rains, however, brought muddy roads. The next month an average of four cars a day passed the monument. Due to a scarcity of rain in April, the dirt road from Fredonia west to the Utah line was "full of dust and pot holes," Heaton reported. [617] If the truth be told, there was only a rare, totally unpredictable, and small window of time when the condition of the dirt road passing the monument could be called "good," since its state was so subject to weather conditions and infrequent maintenance. In April 1929 motorists encountered a more unusual problem: high winds had created sand drifts four to five feet high south of the monument. Union Pacific had to send its snowplows to clear the road in time for the beginning of its travel season. In July 1929 Heaton wrote, "We are still having dry and windy weather here. No storms as yet, and the roads are getting almost impossible to travel on account of the deep ruts and sand." [618]

Blowing sand and dirt created more than just a road problem. Heaton was continually challenged to keep the stuff out of the fort and to keep the windows clean. "We have had west winds that have drifted the sand and dust about every day," he wrote in the summer of 1929, "so that it has been almost impossible to keep the old fort clean of dirt." [619] One of the most effective ways used to reduce the dust problem around homes in such arid regions is to plant trees or other vegetation, thus Heaton's planting activities also served a practical function in addition to creating a more attractive site for tourists.

Despite the difficulty motorists encountered reaching Pipe Spring because of poor road conditions, auto camping was quite popular at the monument. A report from Pinkley (cited earlier in this section) indicated that in July 1925 he had two areas graded for camping, one at either end of the fort ponds. [620] Most camping took place east of the ponds. The ground to the east of the ponds is considerably dryer due to a seep spring near the west cabin. [621] During every night in June 1929, there were usually two or three cars whose occupants camped at Pipe Spring. [622] The travel season in the region usually ended about mid-September. During the month of October, traffic consisted primarily of deer hunters en route to the Kaibab National Forest. In November 1929 only three or four cars passed by the fort each day; nearly all were local traffic. [623] Even after the opening of the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway, campers continued to stop at Pipe Spring. At the end of May 1932, Heaton reported, "There has been a total of 43 campers this month, the most I have seen since last fall." [624]

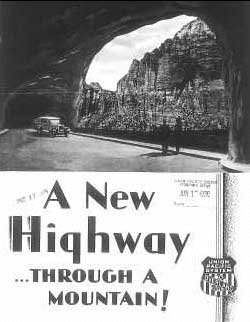

"A New Highway...Through a Mountain!"

During the 1929 travel season, Pipe Spring National Monument experienced its highest visitation since establishment. But the winds of change were starting to blow. As mentioned earlier, the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway was dedicated and opened to traffic on July 4, 1929. The road's impact on both travel past and visitation to Pipe Spring National Monument was nearly immediate for beginning in the 1930 travel season, commercial tours no longer took the road that passed by the monument. Nor were many private auto-tourists inclined to take the longer and less scenic route, even though the distance from Zion to the North Rim had been reduced by the Rockville shortcut.

|

|

49. Kanab Lodge, ca. 1928 (Courtesy Union Pacific Museum, image 8519). |

Union Pacific published its 1929 maps and promotional literature offering trips to the North Rim via the new highway. Only one trip traveled the Pipe Spring route, a tour of Zion, Bryce, and Cedar Breaks, with the footnote that the Zion road would be taken as soon as it was completed. It offered only a 15-minute stop at Pipe Spring. [625] Beginning in 1929, UP's tour scheduled a new stopping place for lunch: Kanab, Utah.

From that year on, all of UP's tours exclusively took the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway in its park-to-park travel. That year's promotional maps showed both routes to the Grand Canyon. In later years, UP's promotional maps would either show the Pipe Spring route by a very faint line or not show a road there at all. The company's venture with tour buses in southern Utah proved so successful that in 1929 Union Pacific and Northwestern bought out a bus company called Interstate Transit Lines and launched a series of interstate bus routes, soon paralleling all its major rail routes with bus service. By 1931 Utah Parks Company was running 65 buses in its circle tour of southern Utah parks and the North Rim. [626]

|

|

50. Union Pacific promotional map, May 1929 (Courtesy Union Pacific Museum). |

|

|

51. Cover of Union Pacific's publication on

Zion—Mt. Carmel Highway, 1929 (Courtesy Union Pacific Museum). |

Heaton's monthly reports to Pinkley indicate the new road did not impact visitation to Pipe Spring during the 1929 travel season. [627] The decline became noticeable, however, by early 1930. At the end of January 1930, Heaton reported, "Very few cars and visitors this month aside from the mail truck. There has not been more than two cars per day this month. This is probably due to the fact that the Zion-Mt. Carmel road is now open to travel." [628] Another factor in low visitation that month was most certainly the weather, for one of the worst snowstorms to sweep over southern Utah occurred between January 9-18, 1930.

Still, Heaton's observations about the impact of the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway on Pipe Spring travel were an ominous sign of things to come or - it might be more accurate to say - not to come. For the month of February Heaton observed, "There has been very little travel this month and it has been all local people. The Zion-Mt. Carmel road has been opened to the travel and that has taken the travel from this way." [629] Again in March, Heaton reported, "...very little travel this month." [630] By summer Heaton still reported low visitation even though road conditions were improved due to rains. He wistfully wrote, "...wish more travel would come this way." [631] Things did not pick up in July, usually the heaviest travel month for the region's parks. Heaton's report for July stated, "There is very little to report.... Only one car camped here this month and an average of one car of tourists per day and only about half of them stop." [632] Two years later Heaton reported that visitors who came generally drove out from Fredonia, rather than from Short Creek: "After spending an hour or more here they return to the highway and continue on their way to Grand Canyon, Bryce or Zion National Parks." [633]

While visitation in Zion rose 65.6 percent the year after the opening of the new highway, visitation figures for Pipe Spring dropped dramatically. From the estimated 24,883 Pipe Spring visitors reported for FY 1929, only 8,765 were reported for FY 1930, a 65 percent drop. [634] (The drop corresponds almost exactly with the amount of increase in visitation to Zion and Bryce Canyon for the same period.) In 1931 visitation to Pipe Spring dropped to an estimated 2,300; in 1932, only 2,100 visitors came to Pipe Spring. [635] Thus in just two years after the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway was completed, Pipe Spring National Monument experienced more than a 90 percent decrease in visitation.

|

|

52. "If it's a National Park..." Union Pacific

advertisement, ca. 1930 (Courtesy Union Pacific Museum). |

Zion National Park's travel statistics for FY 1930 recorded another marked trend: while the number of people driving automobiles to Zion nearly doubled between 1929 and 1930, the count of those coming by train dropped by about 20 percent. [636] As more people took their personal cars on vacation, their destinations and routes were no longer constrained by Union Pacific's planned tours. One would think this would have lessened the impact of the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway on Pipe Spring, but it did not. Because the spectacular new highway with its mile-long tunnel cut through solid rock was a not-to-be-missed attraction in and of itself, its construction resulted in a permanent rerouting of tourist traffic traveling from southern Utah parks to the Grand Canyon's North Rim. Shortly before the 1930 travel season, Union Pacific published a large format, five-page advertising brochure on the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway, complete with panoramic photographs of Zion scenery taken from the vantage point of the new road. The publication proclaimed that the new $2 million, 24-mile highway "is one of the most spectacular scenic roads in America, if not the whole world." [637] It also stated that one of the new road's chief advantages was that the shorter distance between parks resulted in a $15 reduction in the cost of the tour. The amount of driving distance saved, however, completely depended on what parks one was visiting. If one traveled from Zion to Grand Canyon, the new highway was only 18 miles shorter than the old route past Pipe Spring. On the other hand, if one traveled from Zion to Bryce Canyon, a distance of 61 miles was saved. The new road provided an obvious boost to visitation at Bryce Canyon, but then Bryce Canyon had just been elevated to national park status. The new park's visitation doubled between the 1929 and the 1930 travel seasons. [638]

About 1930, Union Pacific's advertising wizards hatched the slogan, "If it's a National Park it's probably on the Union Pacific." By then 13 of the nation's 19 national parks were either directly on UP rail routes or could be conveniently reached by UP service, such as the Utah Parks Company's bus operations serving the Cedar City tourist railhead. It was most likely a very effective advertising message but carried with it the veiled implication that what wasn't on their route perhaps wasn't worth seeing. By the 1940s, a number of UP's promotional maps did not even depict the old route past Pipe Spring and certainly never advertised it, as UP had (by including it in their itinerary) from 1924 to 1929. The fortunes of Pipe Spring, "monument to western pioneers," seemed destined to suffer the whims of tourism. As the demands of motoring tourists (and those who served them) contributed to the monument's establishment in 1923, so did their changing travel patterns lead to near abandonment of Pipe Spring National Monument after 1930.

|

|

53. Sketch map of Southwest Utah and Grand Canyon, 1930 (Courtesy Zion National Park). (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Union Pacific wasn't the only agency changing its maps. A map of southwestern Utah and northern Arizona included in the general circular for the 1930 travel season, issued by Zion and Bryce Canyon, also indicated that the Zion-Mt. Carmel route was the one to take from Zion to reach either Bryce Canyon or the North Rim. Major routes were depicted in bold, as opposed to the fainter line of the old route that passed Pipe Spring. At least the Park Service circular that contained this map included a few enticing paragraphs describing the monument:

Pipe Spring, now a national monument, contains the finest spring of pure water along the road between Hurricane, Utah and Fredonia, Arizona, a distance of 62 miles, and some beautiful shade trees, and to travelers it is a welcome oasis in the desert...

Pipe Spring is an attractive place for motorists using the old road to stop and eat lunch... [639]

The circular fails to mention that camping was allowed at Pipe Spring, only saying that comfortable accommodations could be had in Fredonia and Kanab. Neither is there any reference to the history of Pipe Spring.

It would not be accurate, however, to view the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway as the sole reason for the dramatic drop in visitation to Pipe Spring by 1932. Travel statistics to nearly all southwestern national monuments show a marked downward trend after 1929. While a steady increase in visitation was experienced in the late 1920s, this trend began to reverse after the Wall Street stock market crash of October and November 1929. Overall visitation to all southwestern national monuments was at its peak for the 1929 travel year: 567,667. The following year, the figure dropped to 472,095. In 1931 it fell even further to 392,011, representing a 69 percent drop in only two years. One might argue that the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway caused Pipe Spring's initial 65 percent decrease in 1930, but that the continued decrease in 1931 and 1932 (the other 25 percent drop) was caused by the effects of the onset of the Great Depression.

While the completion of the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway spelled trouble for Pipe Spring, a road disaster in Zion could just as easily bring about good times again. In September 1932 the road's mile-long tunnel was blocked by a cave-in and was closed for the entire month of October. Heaton reported, "...the contractors on the Zion road had some bad luck by having the tunnel blocked by a cave-in. I don't wish Zion Park any bad luck but their bad road has boomed my travel. It sure puts new life into a fellow after two years of depression in travel to see cars coming and going all hours of the day and night. It is like it was before the Zion-Mt. Carmel Road was opened." [640] Visitation at the monument went from 411 visitors in September to 750 in October with an average of 10 cars per day. By November the tunnel had reopened and visitation was down to 165, mostly local travelers.

Throughout his tenure at Pipe Spring, Leonard Heaton demonstrated a willingness to follow whatever direction he was given by Park Service officials. There were times though, particularly in the early 1930s, that the monument received few official visits. On July 1, 1930, Heaton had to travel to Kanab to meet with Horace Albright, as the director either wasn't inclined or didn't have time to make the 15-mile drive to Pipe Spring on the poor road from Fredonia. At such times Heaton used his own judgment in administering the monument, just as former Director Stephen T. Mather had advised him. Two things began to alter this pattern: 1) the push beginning in 1929 by the Bureau of Indian Affairs to obtain water from Pipe Spring for the Kaibab Paiute, and 2) the launching of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal programs, most enacted by Congress beginning in March 1933.

Early Interpretive Efforts in National Monuments