|

Pipe Spring

Cultures at a Crossroads An Administrative History of Pipe Spring National Monument |

|

PART IV:

THE GREAT DIVIDE

Introduction

Despite the water agreement reached at Pipe Spring National Monument on June 9, 1924, between the National Park Service, Office of Indian Affairs, and Charles C. Heaton (representing area cattlemen), the issues of water rights and distribution came up again in the summer of 1929 and continued to surface into the 1930s. [667] They primarily arose from the Office of Indian Affairs' concern about the amount of water being used on the monument by caretaker Leonard Heaton. Prior to Heaton's appointment, little if any monument water was used for landscape maintenance. There is no evidence of landscaping activities at Pipe Spring while the monument was under John White's direction, other than removal of fences and corrals. With Park Service permission, White did maintain a small family garden, and the Office of Indian Affairs had made no objection to that concession. However, once Leonard Heaton was hired as monument caretaker in early 1926 things quickly changed. In addition to the Heaton brothers' pond (mentioned in Part III), two new reservoirs (the meadow ponds) were built to impound spring water for irrigation. Some of the water was used to irrigate land for the Heatons' personal use (for grazing meadows, gardens, and fruit trees) while other water from Pipe Spring sustained vegetation of direct benefit to the public (shade trees around the fort and nearby camping areas). Although Heaton's planting activities demanded ever-increasing amounts of water to maintain, a surprising five-year period of calm reigned between the signing of the 1924 agreement and 1929 when conflict over water issues erupted once again to a level requiring involvement by Washington's Department of the Interior officials. To understand why this was so, one must know what was happening a few miles to the north.

Water Problems at Moccasin Spring

After ownership of Pipe Spring was transferred to the federal government in 1924, the Office of Indian Affairs and its agent, Dr. Edgar A. Farrow, grew increasingly concerned about the Kaibab Reservation's water supply at Moccasin. (Farrow's worries were no doubt heightened by the 10-year drought that began in 1922.) One-third of Moccasin Spring served the Kaibab Agency and School headquarters, provided the domestic water for the Indians, water for their work animals, and water for irrigation of the school and Agency gardens and the Indians' fields. For years an almost constant controversy persisted between Agency personnel (especially Farrow) and the extended Heaton family about Moccasin Spring, whether it was a dam below the weir, a pipe outlet above the weir, pollution of the spring by stock and poultry, the development of nearby springs by the Heatons (believed by Farrow to reduce the flow of the main spring), or other matters. In addition to these long-standing problems, by the mid-1920s the old division weir and water pipeline constructed by the Indian Irrigation Service in 1907 had seriously deteriorated. In a January 1925 letter to Office of Indian Affairs Commissioner Charles H. Burke, Farrow reported that "the condition of the weir is exceedingly bad. It is doubtful if temporary repairs can be made to prevent leaks. A portion of the pipeline leading from the weir has become eroded to such an extent as to make it unsafe." [668] Farrow made several recommendations to make the weir and pipeline safe and effective. He had no funds to pay for the work, however, thus sought assistance from the Washington office.

After informing Commissioner Burke of the poor state of the reservation's water system, Farrow went back and thoroughly reviewed C. A. Engle's report of May 14, 1924. [669] Believing that the Indian Service had overlooked several points in this report, he wrote to Burke to bring them to his attention. Farrow also stressed the need for water measurements to be taken right away to determine what effects planned water development by the Heatons might have on the flow from Moccasin Spring. He suspected that an observable decrease in spring flow was caused by the family's attempts to develop additional water supplies in the immediate area. [670] Farrow advised Burke that immediate construction of a new weir was needed and that a new pipeline should be laid over the Heaton family's garden plot prior to planting time. [671] He also reported on recent conversations that he had with "Mr. Heaton, Sr.," (Jonathan Heaton) over the water situation:

He believes that legally he is entitled to this water without division but is willing to waive this point and allow the Indians one-third of the water as it flows to the present weir. As to the justice of this contention, I have no means of knowing and doubt if it could be determined even after much litigation. [672]

This is the first and only instance encountered to date where the Indians' one-third right to Moccasin Spring was called into question, even during all the years of the Heatons' litigation over homestead claims on the reservation. Jonathan Heaton, according to Farrow, was now implying that he was letting the Kaibab Paiute have the one-third share of water out of the goodness of his heart, not because they were entitled to it. The fact that the patriarch of the family made such a comment in 1925 bolstered Farrow's fear that the water supply, so long depended on by the Kaibab Paiute, was in grave danger of being taken over by the Heatons. It also suggests that while Moccasin Spring supplied enough water for both the handful of white residents and the small band of Indians who lived there in the late 19th century, its resources were now being stretched beyond capacity by increasing population of both Heatons and the Kaibab Paiute, their growing livestock herds, and the area's drought. [673]

By the winter of 1926, Farrow had managed to buy materials for improvements to the reservation's water system. In January 1926 Farrow notified the Commissioner of Indian Affairs that pipe and cement were on site and that lumber was soon to be purchased for the project. He requested the assistance of an engineer to oversee the work and stated, "It is proposed to change the location of the weir and construct it in such a manner as to guarantee uncontaminated water for the domestic supply of the Kaibab Agency and Indian settlement." [674] Engineer C. A. Engle had expressed his willingness to do the work if authorized by the Washington office. Assistant Commissioner E. B. Meritt responded to Farrow's request, informing him that no additional funds were available for allotment to the Kaibab Indian Reservation, but that if Farrow could pay the engineer out of his existing budget, then Engle would be authorized to do the work. [675] Farrow wrote Engle on March 5, and asked if he could begin work after March 15th for he wanted the new system completed before planting season. Engle replied he was unable to come until late summer due to other work priorities. He recommended instead that Farrow use another engineer, Leo A. Snow of St. George. [676]

Engineer Snow was contacted in late March and consented to do the work for $10 per day plus mileage. On June 1 work commenced on the Moccasin weir. Immediately upon arrival, Snow measured the flow of the spring with a 24-inch Cipolle weir. The spring flow was 0.60 second feet. "Without a full understanding and appreciation of the problems involved or the spirit and temperament of the contending parties concerned, I permitted the small impounding dam to be cut before making a careful observation of losses due to this impounding," Snow later reported. [677] The reservoir was drained and a concrete cutoff wall was constructed, into which an 18-inch weir was installed. Original plans had to be modified due to objections by Moccasin residents. Seepage that occurred prior to the concrete wall further complicated the water division, requiring Snow to modify the weir. Snow reported that he had had to go to considerable lengths "to satisfy the demands of residents of Moccasin." [678] In addition to the construction of the new weir, the old pipeline to Kaibab Village was replaced with 7,800 feet of four-inch steel pipe. Snow wrote in his final report,

I was very much grieved to see that the residents of Moccasin felt to distrust every effort toward the correct division of the waters and even expressed their determination of employing an engineer to go over the work accomplished and see if it was correctly done and that they were not being mysteriously robbed. [679]

In September Farrow forwarded a copy of Snow's report to Engle who in turn commended Farrow and Snow for their good work. Engle said the concrete weir was "a great improvement over the old system, especially regarding the important considerations of conservation of the limited water supply, and the sanitary conditions affecting it." [680] He also called attention to a slight error he believed Snow had made in proportioning the weir which would result in the Indians getting slightly less than the one-third share they were entitled to. He requested that Snow recheck the flow and make adjustments if needed by making a change in the position of the knife-edge dividing the weir. It is presumed that Engle's request was carried out (no further correspondence on the matter was located). What is apparent from the actions described in connection with the installation of the new weir and replacement pipeline is that the Office of Indian Affairs went to considerable lengths to ensure a fair division of Moccasin Spring water, in spite of the intense distrust displayed by the white residents of Moccasin. These feelings of distrust, however, were not at all one-sided; Farrow had expressed similar feelings for years.

At about the same time Farrow noticed that the water flow from Moccasin was diminishing, the reservation's use of water for irrigation was approaching its peak. From the time of its being set aside in 1907 and 1938, land irrigated on the reservation varied from 15 to 45 acres. In 1931, 44 acres were being irrigated. Meanwhile, Moccasin farmers were irrigating 90 acres of land. (By way of comparison, 22 acres were being irrigated on the reservation in 1914 versus 75 acres in Moccasin. [681])

Water was not the only area of contention between local ranchers and the reservation's agent. During the 1920s and early 1930s, issues of stock trespass, grazing permits, and grazing fees on Indian land were also areas of considerable conflict. [682] Local competition for water and grazing land was becoming particularly intense and, perhaps not surprisingly, increasingly antagonistic. The 10-year drought and onset of the Great Depression only worsened the situation.

Although Farrow and his family left the reservation to move to Cedar City, Utah, in 1926, Farrow continued to serve as the Indian Service's agent for the Kaibab Indian Reservation. [683] During the summer of 1928, two influential visitors from the East visited Anna Farrow in Cedar City (Dr. Farrow was away at the time). The two were Mary Vaux Wolcott of the Board of Indian Commissioners and John Collier, Office of Indian Affairs. [684] Collier already had the reputation of being a tough, zealous, and idealistic crusader for native rights. According to one source, he had heard that the establishment of Pipe Spring National Monument shorted the Indians water. [685] If the Indians were not receiving their share of water, he told Anna Farrow, he planned to launch a "press campaign in Washington, which would show up... the Park Service." [686] When Collier succeeded Charles J. Rhoads as head of the Office of Indian Affairs in May 1933, change at Pipe Spring was inevitable. [687]

|

|

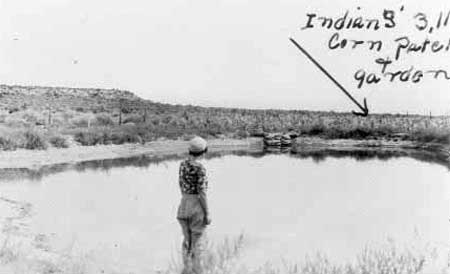

56. Kaibab Paiutes hauling water, Kaibab Indian Reservation, 1932 (Photograph by C. Hart Merriam, courtesy of Bancroft Library, University of California). |

The Indian Service Looks Toward Pipe Spring

Assistant Commissioner E. B. Meritt reported to Secretary Hubert Work in August 1926 that "the Indians do very little farming, owing to their lack of water, and have very little stock. They gain their livelihood principally by day labor." [688] The economic well being and health of the Kaibab Paiute heavily depended on access to a safe and sufficient supply of water. A number of earlier surveys on the Kaibab Indian Reservation had been made with a view to improving the water supply for irrigation (Means, 1911; Dietz, 1914; Engle, 1924) but nothing feasible was reported. [689] Aside from Moccasin Spring and Pipe Spring, there were a number of other springs on the reservation, but these were used only for stock watering as they were small and not permanent. The washes were only an occasional source of water for cattle. While they carried water after storms, they were dry most of the year. A suggestion had been made in at least one of the early reports that investigations of underground water supplies be conducted, but even if a source could be located, its development would entail considerable expense. Increasingly, it became obvious to the Indian Service that a less costly solution would be to use Pipe Spring water, as already provided for in the monument proclamation. At the same time the Indian Service cast its eyes at Pipe Spring as a promising new source of water, the monument caretaker was busily impounding much of it in two new reservoirs (the upper and lower meadow ponds) and greatly expanding his agricultural and landscaping activities.

Heaton's flurry of activity in farming, irrigating, and tree planting on the new monument had not for one moment escaped the attention of Dr. Farrow. The reservation's superintendent looked upon Leonard Heaton's actions as a deliberate move to deprive Indians of their rights to Pipe Spring water. He wanted and believed the reservation was entitled to any monument surplus water to irrigate the gardens of the Kaibab Paiute. Yet the clause that Commissioner Burke had insisted be inserted into the 1923 monument proclamation left too much room for conflicting interpretation. By the late 1920s, it was becoming apparent that the water provision for the Indians needed to be spelled out in much clearer terms.

In June 1929 Supervising Engineer L. M. Holt of the Indian Irrigation Service visited the Kaibab Indian Reservation to measure the flow of water from Pipe Spring. [690] The engineer then recommended to his superiors in Washington that the Office of Indian Affairs and the National Park Service jointly develop regulations governing the use of water at Pipe Spring. Assistant Commissioner J. Henry Scattergood requested a conference for the purpose of formulating definite regulations. [691] Associate Director Arno B. Cammerer replied that the Park Service was agreeable to the meeting but asked that the Indian Service furnish its suggestions in advance so that they might be considered by local field officers prior to the conference. [692] Commissioner Rhoads replied in a letter to Director Horace M. Albright, explaining that the engineer had been sent to Pipe Spring due to the difference of opinion between Farrow and Heaton over the division and use of the water. Rhoads wrote,

As we understand it, there is nothing in the President's proclamation to indicate that this water was to be used by the National Park Service for irrigation purposes, and it does appear that the language shows clearly an intention to allow the Indians the use of surplus water for irrigation and other purposes. It is reported that the Caretaker of the National Monument has conveyed water from the springs through two small reservoirs and uses it for irrigating his garden. It is further reported that there are indications that he intends to construct another reservoir to impound more of the water, evidently to be used for irrigation.

...The total flow of the springs was found to be only 33.56 gallons per minute, from which there would still remain after depletion by evaporation from the surface of the pools and by the use of the Caretaker for domestic purposes a sufficient amount to irrigate several acres of garden, which would add greatly to the food supply of these Indians...

It was with a view to preparing definite regulations primarily on this feature that a conference with your service was suggested. [693]

The reference to Heaton's plans to construct a new reservoir is important for it would have alarmed Farrow sufficiently to request that Washington send an engineer to Pipe Spring. This may have been the trigger that led to the eruption of problems in 1929. John Collier probably was also behind the Indian Service's new push for a share of Pipe Spring water.

In response to Rhoads' letter, Assistant Director Arthur E. Demaray directed Superintendent Frank Pinkley to prepare a report detailing local conditions and the monument's water needs, along with his recommendations on regulations, so that the director's office could prepare for the proposed conference. Pinkley wrote back expressing his views in strong terms. He pointed out that the Office of Indian Affairs was basing its demand on the clause in the proclamation, not on water rights legally established under controlling Arizona state law. He wrote:

If they could have shown prior use of water or some such valid ownership, they would have most certainly have put it in [the proclamation] at that time. This arouses a pretty strong assumption that they knew they did not have a legal title to the water and so built this clause in the proclamation on which they could make a demand at a later date. That time has now come.

So far as I know, the water law of Arizona covers that National Monument and under the Arizona law the water goes with the land, cannot be sold or transferred apart from the land, and the right to it is established by prior use.

What prior use of the waters of Pipe Spring for irrigation on behalf of the Indians can the Indian Service show? If they could show prior usage they most certainly would not be putting their claim on this clause in the proclamation and letting the real legal right drop into the background. I know of no usage by modern Indians for irrigation. On the other hand, the water has been used for irrigation by the owners of the land now included in the monument for some time in the '80s, if the old timers have reported correctly to me. Under the Arizona laws if the Park Service were a private corporation owning that land I don't believe the Indian Service would have a leg to stand on in bringing suit to take the water over our boundaries and give it to the Indians. They must admit this to themselves or they would not base their demand on the fact that they can take it for use in one Service because the title lies in another Service and both Services belong to the Government. [694]

Pinkley thought the Office of Indian Affairs was playing with words in the proclamation and that under no circumstances did it need to be spelled out exactly how the monument would use the water. Disagreement was on the word "surplus." Referring to Commissioner Rhoads, Pinkley continued,

In other words he is going to allow us to use enough water to supply the needs of only one family and he takes the remainder for the Indians! And this is done on the basis of the clause, which says the Indians shall have the privilege of using waters from Pipe Spring. Maybe we overlooked something when we didn't put a clause in that proclamation allowing the Park Service the privilege of using some of the waters too. If they take the irrigation water after 40 years or so of use on the land, they will be back next year after the drinking water and tell us to catch rainwater for our Custodian! [695]

Pinkley argued that since Heaton was receiving virtually no pay for his services (only a nominal salary of $1 per month), he should be allowed to grow his own crops. Pinkley asserted that no change regarding water use should be made prior to the monument hiring a paid custodian. He wanted to make clear

...that the right and title to the spring rests with the monument but that we will let the Indians use not to exceed half of the flow of the spring out of which they will have to furnish half the stock water when and as needed. If they put that to good use and we find that we can spare any more in future years after we see how this monument develops, we may give them an additional percentage.

It might be well to write into any agreement that they are to take their share of the water at a point to be determined by us. The whole spring might as well run out into the pools and be enjoyed by our visitors and the water divided after that at an inconspicuous point chosen by our landscape experts. [696]

Pinkley had no objections to a time-division of the water if the director cared to go that route, and suggested various methods of distribution. [697] Notice Pinkley's caveat above, "If they put that to good use...." What this appears to have meant from the Park Service point of view was that the Indians needed to demonstrate that any water released to them from Pipe Spring would be used for agriculture (either stock raising or gardening) with a minimum of waste. While a cultural bias was inherent in this demand, it also reflected the reality that water was a scarce and precious resource.

Nothing was done immediately to resolve the situation. For the time being, Heaton continued using water as he had in the past. On occasion, Heaton received requests from local ranchers for water from Pipe Spring. When this happened, he consulted with Superintendent Pinkley for permission, as he did in April 1931 when Lloyd Sorenson of Hurricane asked to water his sheep on the monument for four weeks or until rains filled his own tanks. [698] Pinkley replied to Heaton's request,

There will be no objection from our Park Service standpoint if there is none from the Indian Service.... We will make no charge for the water but he ought not to be allowed to use it longer than is absolutely necessary. We don't want to set up any general practice of having these men depend on us for water, but we are willing to help them out in a neighborly way if they are caught in a jam. [699]

Pipe Spring National Monument had goodwill aplenty, but when it came to water, there just didn't seem to be enough to go 'round.

A Bittersweet Trade

The controversy over interpretation of the proclamation clause that simmered during the fall of 1929 was kept on the bureaucratic back burner until the spring of 1931. In April of that year, Commissioner Rhoads sent a lengthy letter to Secretary of the Interior Ray Lyman Wilbur regarding land and water rights at Pipe Spring. The letter outlined the history of the establishment of the Kaibab Indian Reservation as well as provided a summary of the Heaton land claims. [700] Then Rhoads discussed Pipe Spring (which he referred to in plural form), first pointing out that Charles C. Heaton's claim, which he attempted to locate under the Valentine scrip, had been rejected by Departmental finding of June 6, 1921. Rhoads continued:

The 40-acre legal subdivision upon which the Pipe Springs are located having thus in 1921 been officially cleared as to prior homestead or entry rights became the subject of discussion as a suitable location for a national park which culminated in a Proclamation by the President under date of May 31, 1923 actually designating said 40-acre tract as a national monument. The Proclamation, however, contains the following provision regarding the use of the water of the Springs... [701]

Rhoads then quoted the provision as contained in the monument proclamation that granted water privileges to the Indians of the Kaibab Indian Reservation under regulations to be prescribed by the Secretary of the Interior. Rhoads referenced the meeting held during the summer of 1924 at Pipe Spring between Chief Engineer Reed, Dr. Farrow, Superintendent Pinkley, Charles C. Heaton, and Randall L. Jones for the purpose of discussing ownership and use of waters at Pipe Spring, the meeting which led to the June 9, 1924 memorandum. [702] Commissioner Rhoads pointed out to Secretary Wilbur that,

This memorandum agreement does practically nothing more than to acknowledge the ownership of one-third of the waters from these Springs as belonging to the cattlemen and granting them the right to conduct that quantity of water to and upon any portion of the land covered by their grazing permits, or upon the expiration of such permits, to conduct that quantity of water off the reservation.

Notwithstanding the provisions of the Presidential Proclamation and the subsequent agreements in regard to the use of the waters of these Springs, there still continues a controversy in the matter and the same was the subject of a conference recently held in the Indian Office between officials of the National Park Service and the Indian Irrigation Service at which Dr. Farrow, Superintendent of the Kaibab Indian Reservation, was present. The following facts and conditions were brought out:

1) In regard to the National Park Service, their present Caretaker of the Pipe Springs National Monument is serving practically without salary other than the benefits he may derive from the premises furnished him on the grounds, the value of which depends almost altogether upon his being permitted to have the use of the water from Pipe Springs over and above the one-third set apart for the cattlemen. The National Park Service raises a question as to the validity of the claim to a use of this water for irrigation purposes by the Indians. But they further point out that if it shall be decided that the use of this water belongs to the Indians, it will be necessary for the National Park Service to recommend legislation looking to the establishment of a definite salary for the Caretaker of the National Monument or to an appropriation of funds with which to purchase any rights the Indians may have to the use of the water.

2) In regard to the Indian Service, the records show clearly that the available water supply from Pipe Springs over and above the one-third set apart for the cattlemen and the water required for general domestic purposes, is only sufficient to irrigate garden tracts upon which the Indians would depend for subsistence and would leave none for the Caretaker to use for irrigation purposes.

It is the contention of the Indian Service that these Springs being situated within the boundaries of the Kaibab Reservation and having been cleared officially by the General Land Office as to prior homestead or entry claims, clearly come within the principle laid down in the Winters case whereby the Indians are entitled to the use of the water for irrigation, as was recognized in the Presidential Proclamation. If this contention be true, it is the plain duty of the Indian Service to insist the Indians be protected in their rights to the use of the water, or if it shall be found that they are without valid rights thereto, that fact should be established so that other provisions may be made for these Indians.

It is respectfully requested therefore that this matter be referred to the Solicitor for the Interior Department for his opinion as to who really has a legal right to the use of that portion of the water of Pipe Springs available for irrigation over and above the quantity required for stock water and domestic purposes. [703]

"It is the contention of the Indian Service that these Springs .... clearly come within the principle laid down in the Winters case." What Rhoads is referring to is known as the Winters doctrine. This doctrine of reserved water rights emerged from the legal case of Winters v. U.S (207 U.S. 564, 1908). The suit was brought before the government to restrain appellants and others from constructing or maintaining dams or reservoirs on the Milk River in Montana, or in any manner preventing the water from this river or its tributaries from flowing to the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation. This reservation, located in eastern Montana, was set aside in 1888 for the Gros Ventre and Assiniboin Indians. The U.S. Supreme Court made the decision that access to water there was a "reserved right" implicit in setting aside reservation land, for without water, the court argued, arid land was "practically valueless." In the case of Winters v. U.S., it was decided that the traditional western legal doctrine that guaranteed prior appropriation of water was subject to preceding Federal reservation of lands and implicit reservation of water rights in the amount sufficient to fulfill the purposes of the reservation. The doctrine was not absolute, however. It did not affect pre-reservation appropriations, and the amounts of water reserved were limited to the amounts reasonably necessary for present and future Indian needs. [704] Rhoads' contended in his statement above that the clause inserted into President Harding's proclamation provided de facto recognition that the Winters case applied on the Kaibab Indian Reservation.

Director Albright indicated his concurrence with Commissioner Rhoads' request for a decision by the Solicitor. First Assistant Secretary Joseph M. Dixon also concurred, then the matter was referred to Solicitor Edward C. Finney for an opinion on April 15, 1931. On May 6, 1931, Finney responded to the Department of the Interior's request about the use of Pipe Spring water. He stated that "certain premises" in the proclamation were very important in determining the rights of the springs. These premises were:

1) that the spring afforded the only water along the road between Hurricane, Utah, and Fredonia, Arizona;

2) that the public good would be promoted by reserving land on which Pipe Spring and the early dwelling place were located; and

3) that the Indians were to have the privilege of utilizing the water from Pipe Spring.

Finney stated that in the dispute between the Park Service and the Indian Service on the use of the waters the problem narrowed down to the

...right of the caretaker of the national monument to receive part or all of his pay for service rendered the United States by the use of the waters of Pipe Springs for irrigation or other purposes.

The rights as referred to in the Presidential proclamation to the use of the waters of Pipe Springs apparently contemplate (a) use by travelers on the highway, (b) the privilege of the Indians of utilizing the water for irrigation, stock watering, and other purposes, and whenever these priorities are satisfied the rights of the junior appropriator would begin. It is, however, not intended to define or determine the rights or priorities under (a) or (b) above. [705]

What Finney completely sidestepped in his decision was the legal question of water rights. Rhoads' contention that the Winters case applied to Pipe Spring went unaddressed, as did Pinkley's assertion that, under Arizona water laws, legal ownership of two-thirds of Pipe Spring's water was acquired when the Park Service took possession of the land.

Commissioner Rhoads forwarded copies of the joint request for the Solicitor's opinion on water use at Pipe Spring, as well as the Solicitor's response, to Dr. Farrow at the Kaibab Indian Reservation. In addition, he informed Farrow that Director Albright had asked permission to continue existing conditions for the time being, to allow the Park Service to approach Congress when it reconvened in December with a request for "necessary relief of the situation." Rhoads directed Farrow to grant Albright's request "to the fullest practicable extent without serious loss to the Indians..." [706]

The opinion rendered by Finney meant the Park Service could no longer offer Heaton a livelihood in exchange for his labor. On the other hand, it created the perfect "crisis" situation for asking Congress for an appropriation to fund a salaried position. In a May 18 letter to Chief Landscape Architect Thomas C. Vint, Pinkley wrote,

We just got a body blow at Pipe a few days ago when the solicitor of the Department ruled that we had no right to use of the spring water for irrigation; that it belonged to the Indians. Since we are paying the Custodian $12 per year and the use of the water as his compensation, this is going to force us to make other arrangements in the matter of a Custodian. It is possible it will result in us getting a full paid salary there in the next deficiency bill. [707]

In June 1931, at the director's request, Pinkley forwarded budget estimates for the monument for FY 1932 and FY 1933, with the warning, "Unless we get a full time custodian at Pipe Spring, we will be forced to do without one altogether, as Mr. Heaton will be unable to continue holding the place down if he is deprived of his irrigation water for his crops." [708] Shortly thereafter, Pinkley informed Heaton that the Park Service had permission to continue using water as they had in the past until the matter could be brought before Congress, so that the Park Service could get relief in the way of a full salary for the custodian. He wrote optimistically, "I feel fairly certain that this salary will be allowed." [709] The result was that the Park Service would soon get its funding for a custodian, but only at the cost of sacrificing its previously unregulated use of two-thirds of Pipe Spring's water.

The Opposition Rallies

While Solicitor Finney's opinion had somewhat of a bright side for the Park Service (it would get a salaried position), it was viewed strictly as bad news by white residents of the area and others as far away as Salt Lake City. Leonard Heaton was caught smack in the middle of this mess and could hardly be expected to remain neutral. On the one hand, he was a Department of Interior official (and thanks to the water dispute, soon to be a paid one). On the other hand, he had strong allegiance to his family and heritage, and to area ranchers. On June 10, 1931, Leonard Heaton wrote Pinkley that there was opposition to the Solicitor's opinion, men who "expressed themselves to the fact that the Indian Department would not get the water without hearing from them. They are asking that I send them all the material that I have regarding the matter and they will take the case to Senator Smoot and [Senator] King of Utah." [710] Heaton wrote in the same letter that his father, Charles C. Heaton, had been to Salt Lake City to garner the support of powerful men there. [711] At the end of this uncharacteristically short but highly charged letter, Heaton signed his full name, "Charles Leonard Heaton." In previous (as well as later) correspondence, Heaton always signed his correspondence, "C. Leonard Heaton" or "Leonard Heaton." The use of his entire name in this instance suggests he may have been feeling a particular allegiance to the Heaton family as sides prepared to mount for the anticipated battle over water at Pipe Spring.

Even though the cattlemen had been assured their one-third rights to Pipe Spring (just as the Indians had been assured their one-third rights at Moccasin Spring many years earlier), it appears that they deeply distrusted the intentions of the Indian Service, perhaps fearing they would lose their rights to Pipe Spring water. After all, in the negotiations of June 1924 whereby Charles C. Heaton agreed to deed over Pipe Spring to the federal government, the cattlemen believed the Park Service would be in control of water at Pipe Spring. The Solicitor's opinion now created the very real possibility that the Indian Service would be calling the shots on the use of this precious resource. It is no wonder then, given the history of mutual distrust over the division of water in Moccasin, that a number of local white ranchers and others loudly protested the Solicitor's opinion.

The uncertainty of his economic future must have also been agonizing to Leonard Heaton. In early January 1932, Heaton asked Superintendent Pinkley about the status of the water situation. If the Indian Service was to get the water he had been using, could he at least raise a garden of about one-half acre? In addition to the 220 chickens and 20 x 40-foot house he already had, could he get 300 or 400 more hens and erect a second 20 x 40-foot chicken house? (Possibly Heaton was thinking of going into the egg business, if he was not already engaged in it. One family could hardly eat the eggs of 660 chickens!) [712] Pinkley wrote back saying that he

...had word from the Washington office just lately that we were likely to get the salary there raised to $1,200 per year so it would be worth someone's while to stay there without having to raise a living out of the soil to keep from starving to death. This is not an absolute certainty yet, but I feel pretty safe about it...

I think it would be all right to build the extra chicken house if you put it where it will not be an eye-sore from the road and if you want to continue on the place with this $1,200 salary which will start on July 1. Can you make ends meet on that basis? [713]

On January 19, 1932, Director Albright informed the Office of Indian Affairs that if the custodian's position was funded the Park Service would be in a position to release the water previously used by Heaton, permitting it to be used by the Indians. The filling of the position of laborer (GS-4) at $1,200 was approved by President Herbert Hoover on June 18, 1932, authority No. 98. [714] Beginning July 1, 1932, Heaton became a salaried employee.

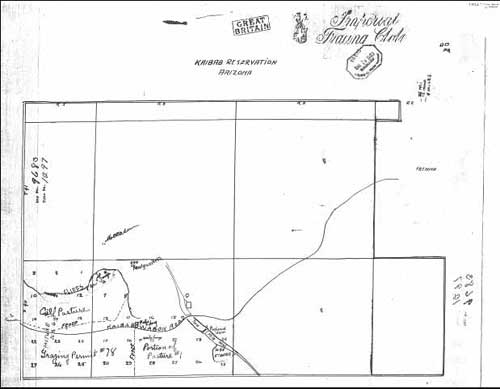

Local sentiment over the water issue at Pipe Spring continued to simmer into the summer of 1932. During a hot, dry May, about 3,000 cattle were watering at Pipe Spring, Heaton reported, "and if there is no storm before long there will be a lot more." [715] A major controversy over the issue of cattle permits was taking place during this time. [716] Up until 1932, a conglomerate of non-Indian cattlemen had been grazing on 6,000 acres of Indian land under three-year permits issued by the reservation. The southwestern section on which permits were issued was known as Pasture 2 (also known as the "calf pasture") located west of the Pipe Spring fort. A 10-year drought and the onset of the Great Depression had resulted in poor grazing and extensive cattle losses. In August 1932 the cattlemen petitioned the Office of Indian Affairs through Arizona Senator Carl Hayden that their permits be renewed at half the rate and that an outstanding debt of $600 to the reservation be cancelled. The petition was signed by five members of the Heaton family, two affinal Esplins, three affinal Lambs, and various Maces and Judds. The Commissioner replied to Hayden in October that he had no authority to cancel the debt, but if it were paid he would consider a reduction in the new permit fee if cattlemen would agree to lower carrying capacities and "provided the Kaibab Indians agree to such action." [717] The outcome of this request will be discussed a little later on.

In August 1932 Office of Indian Affairs Acting Commissioner B. S. Garber wrote to Director Albright pointing out that since Albright's last communication of January 19, his office had assumed that the custodian's position had been funded. Garber then dropped the other shoe: he asked to know when the Park Service would release surplus water to Farrow, "over and above the amount required for domestic use, for the irrigation of the Indian lands." [718] On August 30 Associate Director Cammerer sent a letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs releasing the surplus water "which you permitted the Custodian of Pipe Spring National Monument to use." [719] On the same date, he forwarded copies of this letter to both Pinkley and Heaton and informed them that the surplus water had been released by the Park Service to the Indian Service. [720] There is no record of any discussion or arguments made in favor of the Park Service retaining water for resource purposes.

|

|

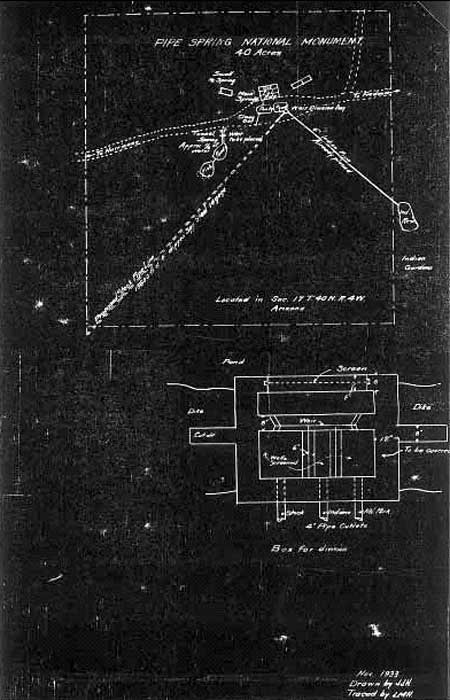

57. Sketch map showing location of pasture No. 2

("calf pasture"), 1921 (National Archives, Record Group 75). (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The dispute at Pipe Spring over water use was hardly settled. It would take more than a year of negotiations between the stockmen, National Park Service, and Kaibab Indian Reservation officials over use and distribution of water from Pipe Spring before a mutual agreement was reached. Men at the highest levels of power in the State of Utah rallied to defend the water of Pipe Spring from the Indian Service. (Obviously, some considered the old fort was finally under the anticipated Indian attack for which it had originally been built!) On September 23, 1932, Apostle George A. Smith (who would succeed Heber J. Grant as Church President in 1945) instructed Senator Reed Smoot to lodge a protest with the Commissioner of Indian Affairs over the water issue. [721] On October 4 Senator Smoot protested to Commissioner Rhoads of the Office of Indian Affairs that the monument needed its water "for the beautifying of the grounds." [722] Rhoads responded to Smoot's suggestion that the Indian Service utilize Two Mile Wash for additional water:

That matter has already been carefully considered by our engineers with the result that it does not appear feasible for the Indian Service for the reason that the sides of the wash are almost perpendicular, and to get the water out by gravity is practically out of the question. It would require a dam of considerable proportions and of material that would resist the elements, which would be expensive beyond practicability...

We regret that the conditions are such as to make it necessary for this Office to insist upon the use of the water from the spring for the Indian lands. [723]

Smoot sent a copy of Rhoads' reply back to George A. Smith, writing, "I regret that the reply is unfavorable but know of nothing further than can be done in the matter." [724] Smith later forwarded copies of Rhoads' and Smoot's letters to Charles C. Heaton, writing,

I regret exceedingly that this complication has occurred but if Senator Smoot knows of no way to remedy it, I am sure I do not. I have given the Senator all the information that you gave me but he evidently concludes that there is nothing he can do in the matter.

I am sorry that the department has taken the attitude it has on this very important matter and hope that there may be something develop in the future to improve the situation. I am closing the incident as far as I am concerned at the present time.

It does occur to me that you might take this matter up with your Arizona Senator and the new administration and in that way have it reopened. [725]

In early October Leonard Heaton wrote directly to Director Albright, expressing his surprise that the water had been turned over to the Indian Service. Although the proclamation had left decisions about water use in the hands of the Secretary of the Interior, he protested, "... as yet I have not read of any action taken by him on this matter." [726] Heaton interpreted the Solicitor's opinion of 1931 as meaning that the apportioning of water would be determined according to prior use, thus the monument had the right to keep as much as had been used "ever since 1863." He continued:

Maybe I am over stepping but as Custodian I am working for the best of the Monument as I see it. If all the water is taken from the Monument and not allowed to water the meadow and trees it will be a matter of a year or so till most of the trees and meadow will be dead. I can't quite bring myself to the idea that those men that purchased Pipe Spring and gave it to the Government meant that the water should go the Indians, but rather that it should be used in making the place more attractive to the public. I am sure that this is what the late Mr. Mather had in mind in having it as a monument. It is also the wishes of the local people that are interested in this place. [727]

Director Albright responded to Heaton's letter by explaining that Solicitor Finney's opinion did not preclude Heaton from using water for domestic use "and as may be required for the benefit of visitors to the monument including that necessary for the preservation of trees and shrubbery." [728] He requested that Heaton submit a report "at as early a date as possible" describing the water situation at the monument, providing maps showing the trees and shrubbery and estimating the amount of water required to maintain them.

Heaton complied with Albright's request by letter of November 7, 1932. He pointed out to the director that even though one-third of the water at Pipe Spring had been reserved for cattlemen, no division had ever been made of the monument's water. Now that the Indian Service was claiming part of the water at Pipe Spring, Heaton believed the cattlemen would demand that a formal division be made to ensure that they received their share. Heaton reported that about 12 acres of land were being irrigated on the monument. Should he cease irrigating, he wrote, much of the land "will turn to sand dunes if nothing is put on it, and the rest will go to thistles and cockleburs. I suggest we get something growing on it as planting it back to its native state of brush and cedar if we can't keep the water to make further improvements in trees and meadows for the benefit of the public and tourists." [729] Heaton protested the Indians getting more water, "as they have not been making use of the water that is on the reservation. About two and one-half miles to the east there is a stream of water that is larger than all the water combined at Pipe Springs. It seems to me that there was a selfish motive connected with the writing of the proclamation." [730]

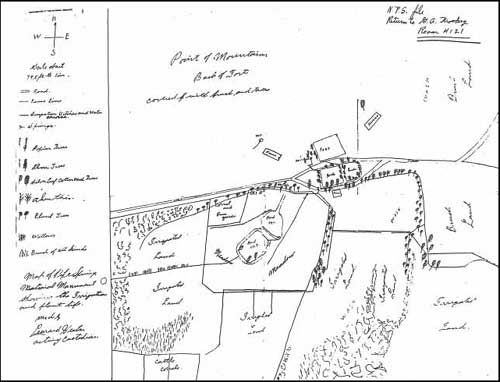

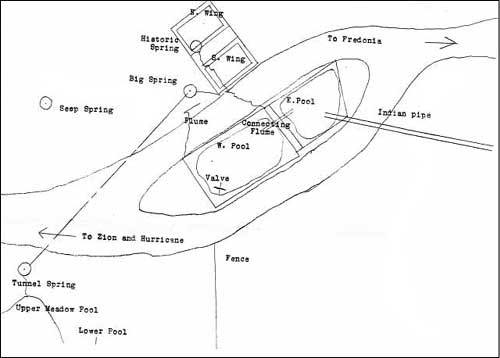

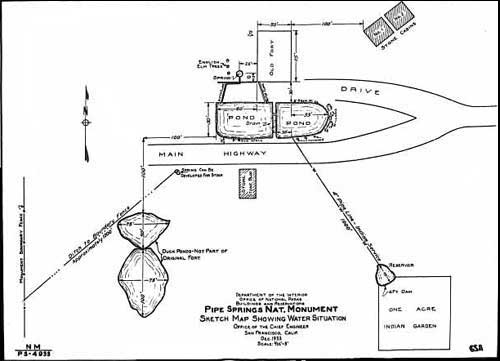

Included with Heaton's letter was a detailed, hand-drawn sketch map depicting - in addition to the historic buildings - the springs, irrigated areas, irrigation ditches, location and types of some of the trees, and other landscape features (see figure 58). Heaton wrote Albright, "There is more trees and brush on the place by about three times but they are located as indicated on the map, and all are along the irrigation ditches.... It will also be seen that the meadow is about one-third of all the land irrigated." [731]

In addition to the earlier fort ponds, the map shows the two meadow ponds, surrounded by meadow. Heaton's small corral and barnyard are shown immediately northwest of the meadow ponds. To the west and south of these ponds and meadow, extending to the monument boundary, was a large expanse of irrigated land. All that remained of the historic cattle corrals at Pipe Spring were the two cattle corrals located at the southwest corner of the monument. In addition to the meadow areas, much of the land directly south of the fort and its ponds was irrigated. Only the areas directly east of the fort were characterized by Heaton as "brush land." Heaton labeled the unirrigated areas as "wash" areas, suggesting that periodic flooding made cultivation there impractical. The location of irrigation ditches is shown on this map as well as the location and identification of trees by type. The location of the old monument road (previously the Kaibab Wagon Road) is shown on this map and should be noted, as it would soon be relocated. The small building shown just south of the west end of the fort ponds labeled "house" represents the Heatons' store which was not removed until 1935.

|

|

58. Sketch map of Pipe Spring landscape, 1932 (Drawn by Leonard Heaton, courtesy National Archives Record Group 79). (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

What is obvious from Heaton's sketch map is that much of the monument landscape was being heavily irrigated and cultivated by the early 1930s. Prior to the creation of the monument, such a landscape would have been highly incompatible with the site's use as a stock watering and corral site for thousands of cattle. Once cattle were no longer watered on the monument and most corrals and fencing were removed, a whole new world of possibilities opened up for the landscape. Heaton only did what any other self-respecting farmer would have done under the circumstances: he irrigated and cultivated the land. Given the number of years the ground had been trod on by large herds of cattle, it seems rather remarkable he could loosen the soil enough around Pipe Spring to permit plant growth, but this he accomplished within only a few years. In this regard, Heaton merely exemplified the tenacity and resourcefulness for which Latter-day Saint settlers in the arid West have long been famous.

Heaton's efforts were at least partly aided and abetted by Park Service overseers who viewed the increased vegetation as making the monument more inviting to tourists. After all, additional trees created shade for campers and picnickers and lush green meadows added visual appeal to the site. Fruit trees have an extremely strong association with the traditional Mormon landscape and would have appealed to the aesthetics and sentiments of many visitors. Besides, the cattlemen seemed content with their share of monument water derived from tunnel spring. Until the Office of Indian Affairs forced them to, the National Park Service simply had no reason to question or limit Heaton's activities with regard to water use at the monument.

The effect of Heaton's increased agricultural activity was that it certainly boosted the amount of water required to maintain the monument's landscape. Yet it must be stated that no documentation has surfaced to indicate that the motivation of either Heaton or the Park Service, which sanctioned his activities, arose from a desire to artificially inflate water requirements and/or usage on the monument. At the time Heaton was undertaking his landscaping activities, he believed the Indians were not entitled to any of Pipe Spring's water, regardless of what the proclamation said. This being the case, why would he need to take action to circumvent their getting it? Given the benefit of the doubt, Heaton appears to have acted as he did in order to provide support for his immediate family and to perform a service to the Park Service, sincerely believing these agricultural activities enhanced the monument's landscape for visitors.

In early December 1932, Associate Director Arno B. Cammerer acted on Heaton's November 7 report on the Pipe Spring water situation. He wrote Commissioner Rhoads stating that the Park Service interpreted Solicitor Finney's opinion as meaning that only waters used by the custodian for his personal farming operations were to be turned over to the Indian Service, and that no objection had been made by the Solicitor to the continued use of water required for "benefit of travelers, including that required for the maintenance of the landscape features at the Monument and for the domestic purposes of the Custodian." [732] He reported that Heaton claimed if the cattlemen demanded their full one-third of the monument's water there would not be enough remaining to meet the needs of tourists and travelers or to maintain the landscape features. Cammerer made the following request of Rhoads:

Under the circumstances, it would appear advisable that the surplus waters of Pipe Springs be left available for the use of the traveling public, including that required for the maintenance of the landscape features at Pipe Springs National Monument and for the Custodian's domestic purposes so far as practicable and until absolutely necessary to draw on it for the Indians. Accordingly, this Service would respectfully request that nothing be done to impair the Pipe Springs National Monument by the diversion of any of the waters from the springs within the monument area for other uses. [733]

On December 27, 1932, Assistant Commissioner Scattergood wrote Director Albright in response to Cammerer's letter opining that, at the time of the monument's establishment, it was "evidently intended" that the surplus water overflowing from the two fort ponds "should be permitted to go to the Indians for their use as stipulated in the proclamation." [734] He pointed out that water taken from the fort ponds would not affect the water taken by cattlemen from the tunnel (tunnel spring). The Indian Service interpreted Cammerer's earlier letter of August 30 as meaning that the Indian Service would get all the water impounded by the meadow ponds as well as overflow from the fort ponds. It was the opinion of its supervising engineer that seepage from the fort ponds would be adequate to maintain the trees and shrubbery surrounding the fort and grounds immediately adjacent to it. Scattergood was opposed to any Park Service plans to enlarge the landscape or maintain vegetation beyond the immediate fort area for this "would hardly be consistent to require the Indians to sacrifice the water for such purposes, which water they are very badly in need of in order to grow the garden crops for their subsistence." [735] Scattergood informed Albright that Dr. Farrow had already purchased pipe to convey the surplus water from the spring to Indian lands and contemplated employing Indian labor to perform the work of laying the pipeline and constructing the reservoir "in the near future." He asserted that the Indian Service could make no further concession of the Indians' water rights "which are recognized in the Presidential Proclamation and are so essential for their subsistence." [736]

The year thus ended with the Office of Indian Affairs insisting that all surplus water at Pipe Spring be turned over to the Kaibab Paiute. But exactly what constituted "surplus" water? That question would take more time, investigations, and negotiations to address.

1933

President Franklin D. Roosevelt's election in November 1932 was soon followed in March 1933 by the appointment of Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes. Historian John Ise described Ickes as an "honest, honorable man and a devoted public servant, but a crusty, crabbed 'curmudgeon'....not an easy man to get along with." [737] Confident that the Park Service was in good hands, Horace Albright tendered his resignation on July 17, 1933, but continued to provide active and constructive leadership in the conservation movement throughout the remainder of his life. His successor was Arno B. Cammerer, who assumed office on August 10, 1933.

>The year 1933 was a pivotal one in the history of Pipe Spring National Monument with regard to decisions made and actions taken affecting the use and distribution of water. In early January of that year, Cammerer forwarded Leonard Heaton a copy of Scattergood's letter of December 27, 1932, informing him that Farrow would soon install a pipeline. Given the position of the Indian Service, wrote Cammerer, "there does not appear to be anything further we can do to forestall the use of water from Pipe Springs by the Indians after that Service has installed the necessary pipeline for that purpose." [738] Heaton then sent a lengthy letter to Superintendent Pinkley on January 11 "to show that there are some facts that have not been considered" in the water matter at Pipe Spring. [739] Heaton wrote,

As you know my Father and his brothers owned Pipe Springs before it was made a National Monument. In about 1920 or 1923 there was a law suit on between the Heatons and the Kaibab Indian Reservation, with Dr. E. A. Farrow supt. over the water and rights here. In this suit the Indians were allowed the place by [the] Sect. of Interior, but the Heatons appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court where they won the case by getting the water and forty acres of land. Before they had the deeds all straightened out it was made a National Monument.

Dr. Farrow, knowing that he had now lost the water by the Supreme Court's decision, saw an opening whereby he could get the water if he could get the CLAUSE put in to the proclamation setting aside Pipe Springs as a Monument, which was done. [740]

It is obvious from this statement that Heaton himself had a poor grasp of the facts, since these statements are completely untrue. The issue never went to the Supreme Court, Charles C. Heaton had just threatened to take it there rather than lose the Pipe Spring tract and water to the Indians. Still, it is important to know that the monument's Custodian believed these assertions to be the facts, although how he obtained these impressions is unknown. It is apparent that there was strong, negative feeling on the part of the Heatons about the water use clause that Commissioner Burke had had inserted at the last minute into the proclamation. To some extent, the family (and perhaps others in Utah who had supported the monument's creation) felt betrayed, as this provision had never been put forth by Mather as a condition for having the site made a national monument. Heaton's words imply that the Office of Indian Affairs had somehow tricked Mather (as well as the Heatons). Heaton wrote,

In going over the letters to Charles C. Heaton from Mr. Stephen T. Mather, he never once mentioned the possibility of the Indians getting part of the water. From the statements that I heard made here by Mr. Mather and others, when they were on their way with Mr. Gray to the Grand Canyon Lodge opening, [I believe] that they did not know that the Indians were to get any water at all and did not know of the part of the proclamation giving them the water. They seemed surprised to learn of the fact. [741]

The occasion Heaton is referring to, the dedication of Grand Canyon Lodge, took place on September 14, 1928. Of course, Mather was aware of the clause inserted into the proclamation, but not at the time of his discussions with the Heaton family. He knew of it just before the signing of the proclamation.

Heaton's heated letter to Pinkley continued with a series of questions: Why didn't the Indian Service demand their water as soon as the Park Service had a clear title instead of waiting until 1930? Why, if the Park Service could keep the Indian Service from getting the water for 10 years, could they do nothing now? "It seems to me that there is a 'nigger' in the woods that is being kept covered up and needs to be seen," Heaton stated. [742] He vehemently refuted the Indian Service's supervising engineer's contention (referenced in the Scattergood letter) that seepage from the fort ponds was adequate to sustain monument trees and shrubbery. "I am wondering... if he has a knowledge of the nature of the soils and the lay of the land, also the action of water in seeping in sandy soils and uphill. For there are trees and the meadow that will never -world without end - get water from those two ponds which he refers to, by seepage." [743] Heaton argued that the Indian Service could develop Two Mile Wash. (This is a proposal the Indian Service maintained was not feasible year after year. Nevertheless, Heaton continued to beat this dead horse over the years, time and time again.) Heaton suggested to Pinkley that Park Service and Indian Service officials investigate the water problem, "together with the local men." He urged, "Have this investigation here before anything further is done by either party." [744]

Heaton wrote a second, hand-written letter to Pinkley on the same date, January 11, 1933. The letter was more of a private nature, "matters that I don't care to have made public unless you think they would help to preserve the water for the Monument." Heaton wrote:

When Dr. Farrow first came here, he and the Heatons did not get started off together and they have been fighting over water and land ever since, and now there is more trouble coming up over the water at Moccasin. Soon after Farrow came he made the statements that he would have the Heatons out of Moccasin in six months or so, and that he would have the water at Pipe for the Indians, so that brought about the lawsuit as mentioned in the other letter.

I have withheld writing this way because I don't want to make more trouble than necessary but things have gone on till I am ready to fight to a good finish to see that justice is done. I know and anybody else does that Farrow is after the water and to show the Heatons that he can get the water. I might say in all the cases that he has brought against the Heatons, he has lost.

The above is the starting and bottom of the whole affair and not that the Indians need the water....

There are going to be several problems come up when the Indians get the water, such as the fish in the ponds, watering of livestock from the spring and several others if Dr. Farrow carries out his fast policies here as he did at Moccasin..Gosh, it will be like having an eyetooth pulled to see the water go and the meadow and trees left to die. [745]

The impact of the Great Depression was being felt all over the country by this time, particularly in unemployment. In February 1933 Commissioner Rhoads wrote to Director Albright that Dr. Farrow had reported there was no prospect of work (i.e., day labor) for the reservation Indians and that they needed to produce as much foodstuff as possible on their lands. Consequently, stated Rhoads, "it is essential that they be permitted to use the surplus water from Pipe Springs as soon as the irrigation season begins." [746] Rhoads asked Albright to instruct Leonard Heaton "to release the water for the use of the Indians" in conformity with Director Cammerer's earlier directive of August 30, 1932. On February 24 Albright sent a telegram to Heaton stating, "Indian Service desires early transfer surplus water from Pipe Springs to Indians. Please make arrangements for this purpose immediately." [747] Albright then informed Rhoads that the action had been taken.

The day he received Albright's telegram directing him to release water to the Indians, Heaton wrote two letters, one to Superintendent Pinkley and the other to Dr. Farrow. To the latter he stated curtly that "...as soon as I hear from Superintendent Pinkley of the Southwestern Monuments regarding the outlet of the water, I will be ready to turn the water over to [the Indians.]" [748] In his letter to Pinkley, Heaton asked where the outlet should go and what type of headgate the Indian Service should use? He also informed Pinkley that he planned to talk with Farrow about three points when Farrow came to get the water. First, he would inform him that "surplus" water was what remained after meeting the needs of "the meadow and other plant life on the monument when it was set aside." [749] Second, the Tribe would be allowed to use the ponds by the fort as their storage ponds but Heaton wanted the water level kept from overflowing so as to prevent the road and campgrounds from getting muddy. Third, Heaton wanted to work out a way with Farrow that he could use some of the water for his family garden and domestic needs. Heaton must have been dreading the encounter with Farrow. In ending his letter to Pinkley he wrote, "I suggest, since you have not been up here for over three years, that you come up and help in settling this water problem..." [750]

The new Secretary of the Interior, Harold L. Ickes, assumed office on March 4, 1933. Pinkley replied to Heaton's above letter on March 11. He told Heaton that while he was of the opinion that Arizona water law should govern the usage and appropriation of water at Pipe Spring, when he brought the matter up for discussion in Washington he had been overruled. Thus, he wrote Heaton,

...we can do nothing but follow out the orders of our superior officers. We will have to deliver the water to the Indian Service and then try to get the Director to come to Pipe and go into the legality of the original usage and the rights we acquired when we acquired the title. Like you, I am inclined to think we may hear of trouble about the division of the water with the cattlemen, but there again, we can do nothing until we have proof that they are being injured.

I do not think the Indian Service has any idea of putting the two old ponds out of use and they will probably want to take their water some place below that. You will let them choose their place for the headgate. Our best play right now is not to fight the Indian Service, but obey the decision of the Secretary of the Interior and find out what use and how much use the Indian Service is going to make of the water when it is turned over to them.

I plan to come up there as soon as I can this spring and we can then go over the details... [751]

About the time that Pinkley wrote his letter to Heaton, a Mr. Lindquist (an inspector for the reservation) and Dr. Farrow visited Pipe Spring to make preparations for installing the new headgate and pipeline. Heaton wrote Pinkley that he hoped to get the Indian Service to allow him to use the fort ponds 4 out of every 12 days for irrigating the meadow and trees. Meanwhile, knowing he could no longer use Pipe Spring water to irrigate a garden, he had not made preparations for one. As area farmers began their spring plowing and seeding, Heaton wrote dejectedly, "It seems something is missing here this year, not having the fields plowed and preparing to plant some kind of crops." [752] He brightened at the thought that Pinkley and his Assistant Superintendent Robert H. (Bob) Rose would soon be visiting the monument. As he closed his monthly report for March, Heaton wrote, "Your visit cannot be any too soon to suit me." [753]

Heaton informed Farrow by letter at the end of March 1933 that he could proceed with putting in the Indians' pipeline, taking the water from the top of the ponds, as the two men had previously discussed. The water was to come from the southeast corner of the east pond. [754] He then wrote Pinkley that his plans were to let the Indians use the two fort ponds as their storage and "take only the water that is not required for the watering of the meadow and trees." [755]

In order to eliminate any possible misunderstanding about the use of the waters at Pipe Spring between the Park Service and the Indians, Commissioner Rhoads issued the following regulations on April 3, 1933:

1) The National Park Service will retain the two reservoirs constructed prior to Presidential Proclamation of May 31, 1923, and use such water from these springs and/or the said reservoirs as may be necessary for domestic and stock watering purposes including that necessary for the accommodation of travelers and tourists.

2) The Indians of the Kaibab Reservation shall be permitted to use for domestic, stock watering, and irrigation purposes all water from these springs except such above described use by the NPS and their rights to such use shall not be interfered with. The Indians in connection with such use of the water as herein defined are hereby authorized to construct, operate, and maintain a pipeline or lines to convey same to their point of use. [756]

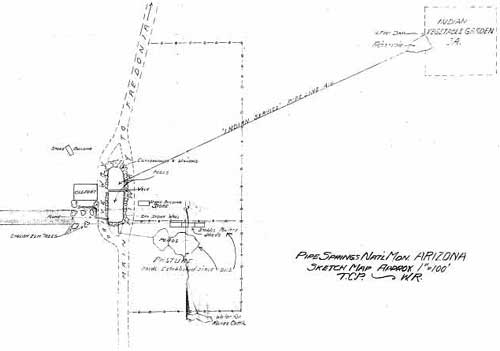

Later correspondence indicates that Rhoads submitted the draft regulations to Albright on April 3 and obtained the director's concurrence with the provisions. [757] Rhoads then transmitted the regulations on the same date to Dr. Farrow. The Indian Service began work on the new pipeline at Pipe Spring on April 5 and completed installation on April 7. [758] The work was performed by eight Indians under the supervision of a Mr. Hanrion, who presumably worked for Farrow. Heaton reported, "It starts from the south side of the east pond and runs in a southeasterly direction to the Indian land where they intend to do some farming." [759] The reservoir with its four-foot dam was located about 1,000 feet southeast of the fort ponds, just outside the monument boundary. (See Thomas C. Parker's sketch map of June 1933, figure 59, or a December 1933 sketch map, figure 65, later in this section.) The first water ran through the Indians' pipeline on April 19. On the same day, Farrow wrote Commissioner Rhoads that the pipeline was completed and the Indians' reservoir ready for the water. Farrow stated that Leonard Heaton wanted to tap the pond reservoirs with a four-inch pipeline and take a turn using the water once in every nine days. In Farrow's opinion, this would practically defeat the purpose of the Indians' pipeline. He expressed the difficulty in knowing what constituted "surplus" water. In Farrow's view, a reasonable concession to Heaton was to provide him with whatever water was needed for culinary use and possibly enough for Heaton's cows and chickens. "I request that a conference be had with the Director of Parks and that a definite understanding be had and that I be advised as to the results," Farrow wrote. [760]

Heaton received a copy of Farrow's letter. Sensing his intentions had been misrepresented, he wrote Director Albright explaining he wanted to run a four-inch pipeline from the west outlet ditch to water the trees and shrubbery east of the ponds, not tap directly into the reservoir itself. With regard to taking turns, he had wanted it to be worked out so that about every third or fourth time the reservoirs were filled, the Indian Service and Park Service would alternate taking water from them. He then suggested a rather complicated method of watering "turns" based on hours of use. [761]

Meanwhile, Heaton reported for the month of April that "Albert Frank and Ray Mose, two young Indians with their wives, have moved here and are making their home just south of the Monument. They are going to do some farming with the water that comes from Pipe Springs." [762] Frank Pinkley held off until mid-April before sending Albright a transcription of the contents of Leonard Heaton's first letter of January 11 (referred to earlier) in which Heaton related "the facts" of the Pipe Spring water controversy (Pinkley did not include or mention excerpts from Heaton's second letter). Pinkley pointed out that although Heaton's statements were "tinged with some personal feelings... there is still enough to cause some reflection." [763] He asked if it would be possible to have Assistant Director George A. Moskey (who was also an attorney) brief the file letters to see how much could be dug up about "the old water fight" at Pipe Spring. Pinkley then put forth his own view in the controversy:

I have always had a distinct impression that the Arizona Water Right Law ought to obtain [sic] in the settlement of who owns the water at Pipe Spring, but nobody else seems to have been interested in that angle. It seems to me that the Indian Service wrote the phrase protecting any rights of the Indians into the proclamation and then afterward pointed to it as evidence that the Indians had some rights and this claim was allowed by the Secretary of the Interior, sort of on the basis that if the Indians hadn't had any rights the phrase would have never been put in the proclamation. My personal opinion is that we have given up water to which we had a legal right if the case were tried under the Arizona water laws and I would like to see one of the lawyers sent out to Pipe Spring this summer to gather the evidence and see if we have not a case to go to court with and get a final adjudication on. [764]

This information from Pinkley gave Albright pause to reconsider the regulations just issued by Rhoads with his concurrence. Albright then appeared to backpedal. On April 27, 1933, the director wrote the commissioner about the regulations, stating that he believed "in general they are satisfactory." Albright continued,

I am fearful, however, that the matter of saving enough water to the National Park Service for the preservation of the vegetation and trees at the monument headquarters is not covered sufficiently to avoid future misunderstanding. It seems to me that this problem is deserving of a more thorough investigation and understanding and I feel that your Service would not wish any unnecessary action taken that would cause the monument area which is not planted to go back to a barren desert. This is quite an oasis in the desert and every effort should be taken to further the development of this growth. To do this would require a modification of the proposed letter, which would incorporate some irrigation by the Monument Custodian...

May I suggest that before these regulations are finally decided one of our engineers in the vicinity go over the matter on the ground with your superintendent and make careful measurements of the spring flow and report on the possibilities of a fair adjustment of water, and a method of piping and control? This can be arranged for at once and a report secured within the next few weeks. [765]

In the meantime, Assistant Director Demaray contacted Zion National Park Superintendent Preston P. Patraw at to ask for his assistance, pending the Commissioner's approval of the above Park Service proposal.

At this point, however, Rhoads was no longer in charge of the Office of Indian Affairs. Beginning in May 1933 the new commissioner was John Collier. Collier seems to have regarded Albright's request for a conference to discuss the water matter as just another Park Service stalling tactic. Collier considered Albright's request, then appears to have denied it in the following response:

...on account of the careful investigations and reports that have been made in connection with this matter and the further fact that the Indians are even now in need of the water for irrigation, it is not believed further delay should occur. Our contention is that the Indians are entitled to all of the water of these springs with the exception of that necessary for domestic and stock watering purposes in connection with the operation of the National Monument, and that while the preservation and further development of trees and vegetation planted at the Monument are, of course, very desirable yet the use by the Indians of this water for growing subsistence is of much greater importance. [766]

Commissioner Collier referenced the April 3, 1933, regulations, pointing out they had been jointly agreed upon, while stating "I believe that the division of the water as therein contemplated is as much of a concession as the Indian Service can make." [767] The lines were clearly being drawn in Arizona's desert sand for an interdepartmental battle over water. In anticipation of a legal challenge, within a few months Collier had his staff outline legal arguments for Kaibab Paiute water rights at Pipe Spring. In addition to falling back on Solicitor Finney's 1931 decision, the Indian Service interpreted the "all prior valid claims" language in Harding's proclamation to mean protection of an Indian prior water right as of at least October 16, 1907. (The cattlemen and Park Service, on the other hand, interpreted "all prior valid claims" as applying only to white settlers' claims.) Collier argued that the stockmen's agreement of June 9, 1924, had not been officially approved by the Secretary of the Interior, even though the Park Service and Indian Service had agreed to it, thus lacked legal status. [768]

At about the same time Pinkley was asking Director Albright for legal assistance on the water issue and the Indian Service was tapping into the Pipe Spring water supply, the fate of an earlier request by cattlemen was being decided by Kaibab Paiute men. As mentioned earlier, in August 1932 Commissioner Rhoads had received a request by cattlemen who grazed on reservation land and watered their stock at Pipe Spring that their permits be renewed at half the rate and that an outstanding debt of $600 to the reservation be cancelled. Rhoads had left the decision up to the reservation's Indians. This may have been the first time the Kaibab Paiute were directly consulted about an issue of this kind. Farrow put the cattlemen's request before a general council of Kaibab Paiute men in the spring of 1933. By a majority vote, the men rejected the proposal. On May 15 several cattlemen appealed to Utah Senator William King to have the decision overturned, stating,

Prior to the creation of the Kaibab Indian Reservation the cattlemen had water, corrals, and pastures capable of handling 5,000 cattle.... To deprive the cattlemen of this pasture leaves them without facilities for handling their cattle and no place to go. Again Pipe Springs is the only fresh waster on this part of the desert, and in hot weather and during drought periods it is the salvation of the cattlemen and cattle industry here. We must have access to these waters. [769]

Should their permits not be renewed, the cattlemen asked King to arrange for a three-quarter- mile-wide right-of-way that would allow them access across reservation land to Pipe Spring. Further negotiations resulted in the Kaibab Paiute agreeing to allow three-year permits on Pasture 2 but only with the understanding it was the final agreement and that a permanent solution to the problem would be reached before expiration of the permits. The cattlemen quibbled over the price of the permits and the compromise fell through during the summer of 1933.

Meanwhile, soon after the Kaibab Paiute general council voted not to renew the cattlemen's leases, local tensions quickly escalated and a direct confrontation took place. Heaton wrote in his monthly report for May: "The most interesting topic of the day in this section is the fight between the cattlemen and the Indian Department as to the rights of the cattlemen to one-third of the waters of Pipe Spring. The Indian Department has closed the cattle away from the water and are claiming that the cattlemen have no right whatever to any water." [770] Indeed, on May 23, 1933, Farrow prevented the cattlemen's stock from using Pipe Spring water. In immediate response, the cattlemen sent telegrams to Washington demanding an investigation. They also defiantly told Farrow they would water their livestock at Pipe Spring when the cattle became thirsty. Heaton informed Director Albright of this situation on May 26 and added that the cattlemen were going to demand their one-third of Pipe Spring water, "which means that all of the water will have to be measured and division pipes put in for the Park Service, Indian Service, and cattlemen." [771] In a separate letter of the same date, Heaton informed Director Albright that he had worked out his own method of distributing surplus water to the Indians, emphasizing his conviction that the needs of the Park Service and the cattlemen should be fully satisfied before any water was given to the Indians.

By coincidence, on that same day, May 26, 1933, Associate Director Cammerer wrote Heaton that Park Service officials had met with an official from the Office of Indian Affairs to discuss the proposed regulations of Pipe Spring's water (those drafted on April 3 by Rhoads). Both offices agreed to submit the regulations to Heaton and to Farrow "in order that the same may be thrashed out on the ground and either individual or joint reports submitted to the two Services for final adjustment and agreement here in Washington." [772] Cammerer informed Heaton that the Park Service desired