|

Pipe Spring

Cultures at a Crossroads An Administrative History of Pipe Spring National Monument |

|

PART IV:

THE GREAT DEPRESSION

Introduction

By the fall of 1930, Custodian Leonard Heaton's monthly reports to headquarters referenced problems of area unemployment. In November he wrote, "There have been only a few people here this last month and they have been hunting work and something to eat." [830] In August 1932 he reported, "The people of this section received 10,800 pounds of flour from the Red Cross which will be a great help to some, but if work is not furnished to some they will go hungry or will have to be kept by some charity organization this winter." [831] During the fall of 1932, Mohave County offered roadwork to help alleviate the problem. Heaton reported, "Road work on Highway 89 is underway allowing married men 30 hours of work each week at .50 per hour. The work has been so arranged that about six or seven men from each settlement will be at work all the time." [832] Yet the problem of unemployment was far too acute and widespread to be solved by local, county, or even state measures. The mobilization of federal forces was required to address the worst financial crisis of the 20th century, known as the Great Depression. The federal programs implemented during the 1930s would considerably impact Pipe Spring National Monument.

The First New Deal

The economic crisis sparked by the stock market crash of late 1929 only deepened during the early 1930s. Before Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in early March 1933, a total of 5,504 banks had closed. Nearly all the remaining banks had been placed under restriction by state proclamations. That month, President Roosevelt took immediate steps to strengthen the banking system while initiating his nationally radio-broadcasted "fireside chats" in an attempt to calm the fears of the nation. Congress then held a 100-day session to address unemployment and farm relief. The resulting legislation was aimed primarily at relief and recovery. Known as the "First New Deal," it lasted roughly from 1933 to 1935.

By an act of March 31, 1933, the agency known as Emergency Conservation Work (ECW) was created to provide work for the unemployed. The law authorized the federal government to provide work for 250,000 jobless male citizens between the ages of 18 and 25. Their duties were to be reforestation, road construction, prevention of soil erosion, and national park and flood control projects. Roosevelt's Executive Order 6101 of April 5, 1933, authorized the commencement of the program. Robert Fechner was named director of the ECW, later more commonly referred to as the Civilian Conservation Corps, or CCC. [833] He served in that position from fiscal years 1933 through 1939. Four government departments (War, Interior, Agriculture, and Labor) cooperated in carrying out the program. At its peak the CCC had as many as 500,000 on its rolls; over two million were enrolled over the course of the program by the end of 1941. [834]

Placed under the direction of Army officers, CCC work camps were established with youths receiving $30 per month, $25 of which went to their families. The government provided room, board, clothing, and tools. The enrollee was expected to work a 40-hour week and adhere to camp rules. Initially, enrollment for conservation work was limited to single men between the ages of 18 and 25. New categories were opened during the months of April and May 1933. On April 14 enrollment was opened to American Indians, who were generally allowed to go to their work projects on a daily basis and return home at night. On April 22 enrollment was opened to locally employed men (known as LEMs). The marriage and age stipulations did not apply to these men, most of whom were in their 30s or 40s. While a limited number of skilled local men were employed, the bulk of the CCC work force came from the unemployed in large urban areas. On May 11 enrollment was opened to men in their 30s and 40s who were veterans of World War I. These enrollees were given special camps, operated with more leniency than the regular camps, and selection was determined by the Veterans Administration rather than the Labor Department. [835] Except for a few installations in Northern states, the camps were racially segregated into white, Negro, and Indian camps.

The program was to be started in the East and extended to the rest of the country as soon as possible. Roosevelt's goal was to have 250,000 youths at work in national parks and forests by July 1, 1933. Various agencies of the Department of the Interior directed the work of the CCC camps: the Office of Indian Affairs, the Bureau of Reclamation, the General Land Office, the Grazing Service (also referred to as the Division of Grazing), the Fish and Wildlife Service, and the National Park Service. In the state of Arizona, the National Park Service directed camps in Grand Canyon National Park and the following national monuments: Petrified Forest (NP-8), Chiricahua (NP-9), Saguaro (NP-10), and Wupatki (NP-11). In addition, Mt. Elden Camp (NP-12), located at Walnut Canyon, performed work there, at Wupatki, and at Sunset Crater National Monuments. [836] In the case of Pipe Spring National Monument, however, the Grazing Service oversaw the camp. Designated Camp DG-44, its work activities concentrated on the public domain. [837] By contrast, for its first two years CCC camps administered under the Park Service were forbidden from working outside park boundaries.

On March 16, 1933, the NPS Washington office issued a memorandum to parks and monuments requesting a report of the number of unemployed in the area, projects on which they could be put to work, and available housing. Heaton reported that 25 men were unemployed in the area of the monument, 18 were supporters of families, and seven were single. All came under the class of common laborer. Unemployed Indians, he reported, were not included in this count as the local Indian Agency was caring them for. Heaton stated that he could house 40 or more men at the monument. (Presumably he was considering the fort and two cabins for housing.) No plans had been formally prepared for the monument, but Heaton suggested a number of possible work projects. [838]

The Office of Indian Affairs participated in the CCC program, and more than 88,000 Indian men enrolled nation wide. The work performed under this program was generally carried out on Indian reservations. CCC regulations were changed according to the realities of reservation life. The War Department was not involved in camp administration on reservations. [839] In September 1933 Heaton reported to Southwestern National Monuments Superintendent Frank Pinkley, "Nine of our Indians have got work in one of the CCC camps for the winter and a large percent of our unemployed are in these camps. There are five of them within 150 [miles] of here." [840] It would be two more years, however, before a CCC camp would be located at Pipe Spring National Monument.

Of earlier importance than the CCC at Pipe Spring National Monument was the Civil Works Administration (CWA), established on November 8, 1933, as an emergency unemployment relief program for the purpose of putting four million jobless persons to work on federal, state, and local make-work projects. Funds were allocated from Federal Emergency Relief Act (FERA) and Public Works Administration (PWA) appropriations supplemented by local governments. [841] The CWA was created in part to cushion the economic distress over the winter of 1933-1934. It was terminated in March 1934 and its functions transferred to FERA.

On the date of the CWA's establishment, Director Arno B. Cammerer issued Circular No. 1, "The Civil Works Program," which was distributed to parks and monuments. Data was requested from the parks and monuments to enable the Washington office to compile a comprehensive outline of possible Civil Works Projects with an estimate of the number of men who could be employed. On November 8, 1933, Chief Engineer F. A. Kittredge telegramed Heaton to inquire how many men and women he had working on Civil Works Projects. Heaton telegramed back that he had not yet been authorized to commence work, that he would only be employing men, and that men were available and ready for work. On November 15 Kittredge informed Leonard Heaton that his office had wired Washington, D.C., requesting 15 men for work at Pipe Spring National Monument, at a cost of $3,510 for the three-month program. The men were to live at home while working. The projects listed for the men to work on were described as "repairs to one-fourth mile road, general clean-up, shifting outhouses, etc.; repairing and rebuilding fences, grading, and planting." [842]

On December 3, 1933, Southwestern Monuments headquarters notified Heaton that funding for work at Pipe Spring had been approved by the Washington office under the Civil Works Program. The monument was allotted $3,167 for labor and $405 for other expenditures. Workers authorized included 13 unskilled men, 1 semi-skilled man, 1 skilled man, and 1 foreman. The next day, Heaton wrote to Pinkley about his plans to use the men:

I have spent some time in planning what work that would be the most benefit at present. I have come to the conclusion that the road be the first consideration, which will be connected up with the changing of the wash so that it will run the water down the east side of the campgrounds and through the place where the old stock corrals were, the filling up of the present wash preparatory for the building the restrooms and residence buildings as Mr. Langley has them planned.

The rebuilding of some of the rock walls and lay[ing] them up with mud [mortar] to keep the rats and rodents from digging out the soil and thus causing the [fort] walls to fall down, also the rock walls around the ponds be pointed up with some material to keep out rodents.

Then I would like to fix up the tunnel [spring] some way and level up the meadow. Then there is the fencing of the monument and putting in a good cattle guard on the east. [843]

Heaton estimated that three or four teams of horses would be needed to keep the men at work on the projects and that they could be accomplished in the 12-week period allowed.

On December 14, 1933, Heaton received the go-ahead from Pinkley to put the men to work. He went to Short Creek to request 16 men from the local Civil Works Administrator. Clifford K. Heaton was hired as foreman at $30 per week. Unskilled men on the work teams were paid 30 cents per hour. The men were to work five days a week, six hours per day. [844] Leonard Heaton purchased materials in Kanab the next day. Park Engineer Arthur E. Cowell arrived from Zion National Park on December 16, as did eight workmen. Cowell, Heaton, and two of the men surveyed the road from the west to east boundary in preparation for its relocation. Five more men arrived two days later, joined by another three on December 23. Heaton had the men work on the monument road and on cleaning up the meadow and the tunnel. The men were to relocate the road that passed between the ponds and the fort to a location just south of the ponds. An archeological discovery of old watering troughs was made during the first week of roadwork, as Heaton describes below:

We had a surprise in digging out the road where we are taking a part of the hill off. After we had taken off about eight inches of dirt from the highest part we began to find cedar and pine logs which had hardly decayed at all. When we reached the 18-inch level we dug up about 20 feet of 2-inch pipe, 15 feet of 1- inch pipe, and some scrap iron. There were several different colors of dirt, indicating that it had been hauled in at different times and from different places. After talking with some of the old timers about my finds, I found that at one time the troughs for watering stock were about in that place and the timbers had been put there to keep the ground from getting soft and sloppy. I am taking this hill down about 24 inches and putting the dirt in the low place east of the pools. [845]

In addition to the roadwork, Superintendent Pinkley directed Heaton to have the entrance to tunnel spring cleaned out, to put in "some sort of rock box for the water," to install cattle guards, and to rebuild monument boundary fences. At the end of a busy December, Pinkley lauded Heaton in the Southwestern Monuments Monthly Report for his careful attention to the "pages and pages of instructions" that were sent out related to reporting requirements for the Civil Works Projects. Headquarters reported that Heaton "turned in the best papers that have come out of the field." [846]

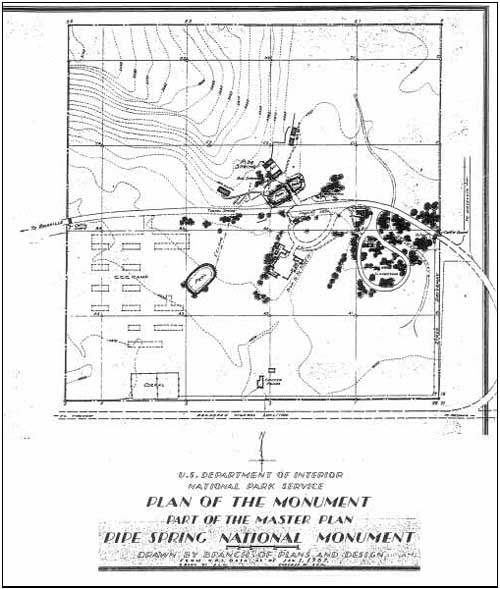

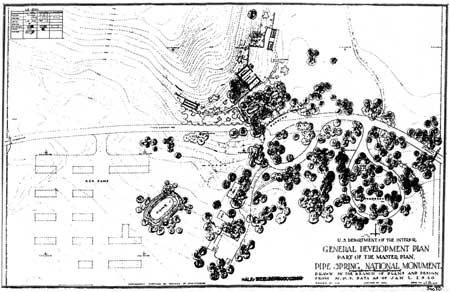

Meanwhile, the Park Service's Branch of Plans and Design in San Francisco completed the monument's first "General Development Plan." [847] Chief Engineer Kittredge forwarded the plan to Cowell at Zion National Park at the end of December 1933 with the request that he proceed to Pipe Spring as soon as possible to stake out the various developments. The plans called for the construction of a campground and comfort station, to be located east of the fort ponds and north of the monument road; a parking area south of the fort ponds and monument road; and two residences, an equipment shed and garage, just below the parking area. [848] All development was sited in close proximity to the fort. Director Cammerer approved these plans in February 1934.

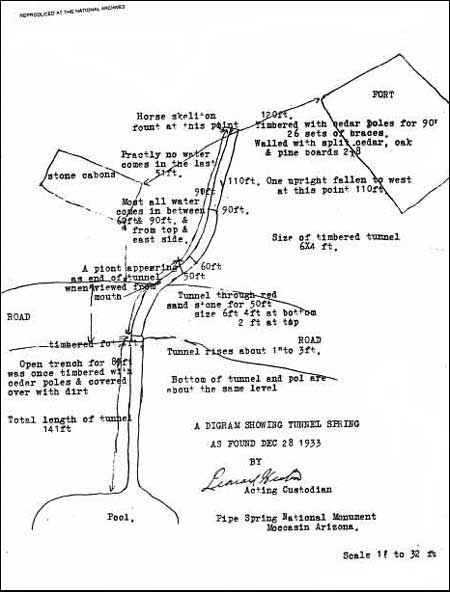

As Heaton and the workers cleaned out the tunnel, they discovered that the original bottom was 2.5 feet lower than previously thought. Heaton speculated, "If we rock up the sides of the tunnel as we had planned, it will mean that the upper meadow pool will be lowered about two feet. I will therefore wait until some Landscape man comes in before I rock it up." [849] On January 5, 1934, Heaton reported on the progress made cleaning out the tunnel. With the help of some boy scouts, he took measurements to send to Pinkley. The first part of the tunnel was six feet high and four feet wide. The tunnel went 88 feet (including four feet of timber at the mouth of the tunnel) until it reached "the hill." At that point, tunneling through sandstone, it proceeded another 50 feet. Within the rock, its dimensions were four feet wide at the top and two feet wide at the bottom. Heaton made several surprising discoveries as he explored the tunnel. The first was that most of the water was encountered between 60 and 90 feet into the tunnel, and practically none at the terminus. The other surprise was at the end of the tunnel a horse's skeleton was found. Heaton stated the horse once belonged to O. F. Colvin who lived at Pipe Spring "from about 1908 to 1914." "He never knew what became of his horse," reported Heaton. [850] Heaton included a rough sketch map with his letter (see figure 66).

|

|

66. Sketch map of tunnel spring, December 1933 (Drawn by Leonard Heaton, courtesy National Archives, Record Group 79). (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Cleaning out the tunnel had created a new problem however. Heaton wrote,

Now the trouble I am having is to decide as to what to do with the tunnel, for the bottom is about on the level of the bottom of the upper pool, and if the flow of the water is changed much by cleaning it up we may have to do away with the pool. The sides keep sloughing in so that we will have to cut the banks on a slope about 20 percent to keep them from caving in.

Mr. Cowell suggested that we place a 3 or 4-inch pipe in at the mouth of the tunnel, then cover up the open trench out to the pool, but I am in favor of rocking it up if possible, as it would add to the beauty of the place. [851]

Chief Engineer Kittredge approved of Cowell's plan to pipe water out of tunnel spring. He wrote, "I see no reason why you should not construct within the tunnel the desired catch basin at each spring, and conduct the assembled flow of water from them to outside the tunnel." [852] Kittredge advised Cowell to construct the collection boxes "in a very permanent manner, preferably out of concrete." Kittredge assured Cowell that the meadow pond would not be lost if he kept the pipe at the same elevation water had flowed through the tunnel in the past. Ultimately, 75 feet of two-inch pipe was placed in the tunnel to carry water to the upper meadow pond. The mouth of the tunnel and pipeline were covered up and a man-hole was left for inspection and cleaning purposes. [853]

Civil works projects continued into early 1934. Harry Langley made several trips to Pipe Spring during this period, one on January 31 and the other on February 6. He reported to Chief Architect Thomas C. Vint that the CWA crew had been cleaning out tunnel spring, grading the campground area, constructing a road through the monument on a new location, planting the campground area, and constructing a diversion ditch to protect the campground from flooding. [854] Langley recommended that the Heatons' store be removed at once to allow completion of the parking area grading (it was situated right in the center of the proposed parking area). He also opined, "The condition of the fort will always be a disgrace to the Office of National Parks, Buildings and Reservations until such time as all living quarters are excluded from it." [855] Vint forwarded Langley's report to Director Cammerer, emphasizing the importance of providing the custodian with a residence. Cammerer replied that Langley's recommendation for development "seems to be to be just about what is desired for Pipe Spring National Monument." [856] Descriptions and estimated costs of the proposed projects, Cammerer wrote, would need to be included by Pinkley when he sent in his request for future Public Works Administration projects.

At Superintendent Pinkley's request, Heaton developed a list of additional projects to undertake if CWA work continued. Proposed projects included work on the east and west approach roads; construction of a water system for the campground and residences; irrigation of trees and meadow; planting of lawns and trees; quarrying of stone for the proposed comfort station, residence, and garage; and completion of filling the wash. Heaton recommended that the irrigation project be done as soon as possible for, once the water was divided three ways, he asserted, "there will be not enough water to irrigate the meadow and trees by the ditch method and to plant trees and lawns as being planned." [857] He also suggested that a trail be constructed "to the top of the hill beginning at the fort going west along the old road where the rock was hauled in for the fort then on top at the monument boundary, from where a good view of the surrounding country and mountains [can be seen] and then coming back down the hill east where the cactus and other plant life can be seen." [858] (Heaton's idea for a nature trail would be around for many decades before it was implemented.) The irrigation system was "first and most important," wrote Heaton. Vegetation was then being irrigated by the ditch and flood system and Heaton felt the Park Service should convert to a piped system and use of sprinklers. A water system would be required if the new residences and comfort station were to be built as planned. Only a few of these projects would ultimately be constructed during the 1930s.

On February 15, 1934, the 30-hour-work week for CWA crews was cut to 15 hours and Heaton was required to lay off some men. Work continued on irrigation ditches and more trees were planted. Cedar and pine trees were set out on the south side of the monument on land that had been farmed. On March 15 Heaton reported to Pinkley that construction on the road and cattle guards was still incomplete. Langley returned to Pipe Spring on March 16 to inspect work projects, to discuss landscaping plans for the monument with Heaton, and to do some fishing in the fort ponds. After six hours of work, Langley spent one hour fishing. Heaton reported he caught five good-sized trout and that Langley asked him to "get some more fish so that he can get to fish every time he comes in." [859] (Heaton made numerous efforts to obtain more fish over the next few years to no avail.) In addition to visits by Langley, Park Engineer Cowell visited Pipe Spring about every other week to oversee CWA work while it was ongoing.

The work program was terminated at the monument on March 22, 1934, leaving Heaton to finish up projects as best he could. Heaton reported that due to the early layoffs, "I was not able to complete a single project." He asked to retain surplus materials associated with the CWA work so that he could complete the projects. The leftover cement was needed to make headwalls for culverts and a rock wall to divert flood waters around the campgrounds. ("If this wall is not completed the first flood that comes will undo all the filling in for the new road, also damage the campground considerable," Heaton explained. [860] ) Wire and staples were also needed to complete the boundary fence to keep out cattle and horses (there was about 250 yards still to be fenced). The surplus galvanized pipe was needed to irrigate trees on the south side of the monument; gates were needed on the monument road to keep loose stock from entering the monument area.

In April Heaton sent in a final report on the projects completed under the CWA program from December 16, 1933, to March 22, 1934. The projects included relocation of the monument road, flood diversion in the area of the new campground, removal of old fences, trimming of deadwood from trees, work on tunnel spring, removal of old reservoir dikes and grading the campground area, survey of boundary lines and installation of new fencing (cedar posts and barbed wire), and preparation of a contour map of the monument by Zion National Park engineers. The work to construct an irrigation system to water monument vegetation had been started but not completed. Heaton reported a number of archeological finds were made during the relocation of the road and grading of the campground, all historic period materials. He estimated that the projects were 80 percent complete by the time work was stopped. The weather had been "ideal," Heaton stated. No work days were lost due to bad weather.

Park Engineer Cowell also filed a formal report on Civil Works Projects at Pipe Spring. (The Pipe Spring work was designated CWA Work Project F68, U.S. No. 8.) In addition to the projects listed by Heaton, Cowell's report noted that boundary survey markers had been placed and location surveys made of the road, campground parking loop, and other planned developments. Topographic surveys were completed for the entire area. Only 80 percent of the grading for the relocated road had been completed; parking area grading was only 40 percent completed. Culvert pipes for drainage had been installed but headwalls still needed to be constructed. Cattle guards had been sited at the monument's east and west boundaries, but not constructed. Boundary fences were about 75 percent completed. Flood drainage rockwork was "about 20 percent" complete. In describing work on tunnel spring, Cowell stated that the outer four feet of tunnel (which was timber) and 14 feet of the tunnel were cleaned out and stoned up and provided with a manhole. A six-inch intake was set in a concrete wall at the lower end of this stone-lined section from which water was carried 185 feet through a two-inch pipe to the upper meadow pool, supplying water to stock. The cut had been backfilled and landscaped. Pipe had also been installed to carry water from the fort ponds to the campground and utility area to irrigate trees. A pipe supplying water from the main spring to roadside was installed to accommodate the public. No work was done to any of the buildings. The total cost of all projects was $2,207.50 in labor and $138.15 in "other," or a total of $2,345.65. [861]

|

|

67. View of Pipe Spring landscape, looking west

toward the fort, 1934 (Pipe Spring National Monument, neg. 367). |

Development planning for the monument continued, with Cowell working under the direction of Chief Architect William G. Carnes, Branch of Plans and Design. In late April 1934, Cowell reported the state of developments at Pipe Spring. He recommended that the irrigation system be extended to cover more of the proposed utility area and the comfort station site. A sewage system was needed, along with completion of all other projects begun under the CWA program. His cost estimates for completing all work (water and sewer systems, roads, fencing, grading, cleanup, drainage, and engineering) was $4,639. [862]

As mentioned, development plans called for the removal of the Heatons' store from its location south of the fort ponds as this area was to be used for visitor parking. In June Heaton informed Assistant Superintendent Hugh M. Miller at Southwestern National Monuments that he wished to move the store and gas pump "to a point just opposite from the road that leads to the campground site." [863] The Heatons planned to enlarge the store at its new site and Grant Heaton sought renewal of his permit. In mid-July, however, Superintendent Pinkley turned down the application to operate the store and gas station due to insufficient traffic at the monument for the previous two years and undemonstrated visitor need. [864] The exact date of the store's removal is unknown, but by April 1935, Heaton reported it had been removed. [865] In a recent interview, Grant Heaton confirmed that the store was torn down and not moved. [866]

Completing the Division of Water

After months of frenzied CWA program activity, things began to settle back to normal at Pipe Spring. Heaton reported to Superintendent Pinkley in April, "I could not resist the call of the garden this spring, so I have plowed up a plot of ground and planted me a garden just south of the meadow. Talking about gardens brings up the question of the water. I have been wondering if anything is going to be done about it this year." [867]

In fact, Dr. Farrow, Kaibab Indian Reservation superintendent, had not been idle on the issue. In mid-November 1933, Farrow spoke with Heber Meeks of Kanab. Meeks had assured Farrow that if the Indian Service purchased the pipe, the cattlemen would lay the pipeline from tunnel spring. The Indian Service then proceeded to obtain the materials. On February 2, 1934, bids were opened by the Office of Indian Affairs on 15,600 feet of four-inch, 16-gauge steel pipe for the construction of the cattlemen's pipeline from tunnel spring to the border of the reservation. The total cost of supplies needed for the pipeline was estimated at $4,600. Before the contract was awarded, Supervising Engineer L. M. Holt informed Office of Indian Affairs Commissioner John Collier that, "we know little regarding the stockmen, whether or not they will be ready to do the work of trenching and laying the pipe when the same is delivered, and line located on the ground." [868] Holt recommended that Farrow be allotted the funds for the work and be put in charge of making arrangements with the stockmen for laying the pipe. Farrow then attempted to recontact Meeks, only to discover he had since died. He wrote to Lee Esplin to find out who had succeeded Meeks as head of the stockmen's committee. [869]

While CWA projects were still underway at Pipe Spring, Langley, Cowell, and Heaton had decided the division box should be placed on the west end of the fort ponds. Heaton informed Superintendent Pinkley in his April report that Dr. Farrow had said the Indian Service was buying three miles of four-inch pipe, that it would be delivered May 15, and that their engineer would be installing the division weir. (The weir was being designed by Cowell.) Heaton doubted that he could sufficiently water the meadow without the flood method, but said with resignation, "I will do the best I can." On a more upbeat note, a proud father announced, "On April 9 a nine lb. boy arrived here to help with the monument work. Mrs. Heaton and baby are getting along just fine." [870] This was the couple's fifth child and fourth son, named Lowell.

On May 3, 1934, Park Engineer Cowell, N. A. Hall (Indian Service Engineer), and Dr. Farrow met with Heaton at the monument in preparation for measuring the flow of the springs and installing a division weir. [871] The Indian Service approved the division weir design suggested to Cowell by Chief Engineer Kittredge with the exception of the weir plate. The Indian Service had a design for a weir plate that Cowell agreed to send to Chief Engineer Kittredge for approval and fabrication; consequently, it was not installed until almost one year later. Hall and Cowell measured the flow by the weir method on May 7 with Charles C. Heaton present, representing the cattlemen's interests. The flow for the main spring (referred to as the "historic spring") was 34.03 gallons per minute; for tunnel spring, 8.12 gallons per minute. The combined flow was 42.15 gallons per minute. A division into thirds provided 14.05 gallons per minute to each party. It was decided that the elevation of tunnel spring could not serve the needs of the Park Service or Indian Service, but met all the requirements of the stockmen. It was agreed that the stockmen would receive all the water from tunnel spring along with 5.93 gallons per minute from the main spring. Three discharge lines were to be installed at the division box, one for the Tribe's pipeline, one connecting to the monument's water system, and one that discharged into the tunnel spring. [872]

From May 8-10, 1934, Indian Service Engineer Hall supervised three Indian CCC workers as they installed the division structure. The concrete box measured 42 x 42 x 42 inches on the inside and had six-inch walls. It contained three compartments, 12 x 18 x 42 inches in size, and a two-inch outlet pipe located three inches from the bottom of the box. The weir was to be placed about 12 inches below the top of the box. The top of the division box was level with the water of the ponds. On May 16 the Indian Service re-laid a two-inch pipeline to carry water from the division structure to a point outside the eastern boundary of the monument. On the same date, the Park Service connected a two-inch cast iron pipe from the structure to the monument's water system. The system directed water to the south side of the monument where the corrals and chicken houses were located and east to the campground. When Heaton tested the system about a week later, he found the campground was getting insufficient water through the line, but that other points were receiving enough water. [873] "It looks to me as if some other method must be found to get the water to the trees on the north side of the campground or the campground will have to be moved to a lower level if trees are to be grown on it," Heaton reported to Superintendent Pinkley. [874] The alternatives, Heaton suggested, were to hand-carry water to the trees, purchase and install a pump, or construct an open ditch to irrigate the trees. None of these alternatives was practical, however, and the following spring officials decided to relocate the campground south of the road where it could be gravity fed with water.

The division of the water was held up further awaiting the construction of the brass weir plate at the Branch of Plans and Design. [875] The stockmen's pipeline also had yet to be constructed. In late May the pipe for the stockmen's pipeline finally arrived. Farrow had it delivered to the monument on May 28 and informed Heaton that the stockmen could begin immediately to lay the pipe. The stockmen refused to lay the pipe, complaining that the 16-gauge sheet iron pipe purchased by the Indian Service would not last more than three to five years in the mineral soil and that they'd been told the pipe would be galvanized. [876] Heaton reported the Indian Service pipe was "tarred" and that its value was decreasing the longer it sat in the hot sun, tar melting, awaiting installation. So the Indian Service had no choice but to trench and lay the pipeline themselves. The pipeline was 2.25 miles long and terminated about 250 yards outside the reservation on land leased by Charles C. Heaton. [877]

That wasn't the only problem, however. Heaton dreaded losing the meadow pond that had been filled by tunnel spring. "A lot of swimmers come there to cool off," Heaton told Pinkley. [878] Of course, the pond had always furnished irrigation water for Heaton's family garden and it was often stocked with fish, so there was more at stake than visitor recreation. The stockmen feared they would be getting less than their one-third share if the meadow pond remained, due to evaporation and seepage. Heaton assured them they had never needed the full one-third in the past. He asked Pinkley if he could rock up or cement the bottom and sides of the pond if the stockmen would let it remain. Pinkley responded that if the cattlemen insisted, the monument would have to do away with the pond, but he agreed with Heaton that their cattle would never need their full one-third share of water. He suggested running a ditch around the pond to allow bypassing the pond when the cattlemen needed more water. No funds were available to cement or rock-line the ponds, Pinkley told Heaton. [879] Heaton then brought up another problem. As the horses "have not learned to drink out of a faucet," he asked if he could construct a concrete watering trough for them and place it "somewhere near the head of the meadow." [880] Apparently, this was a need that had never occurred to Park Service planners and designers back in San Francisco! Pinkley approved his request, but asked Heaton to have Langley draw up the plans and choose the site for the trough.

On August 3, 1934, a crew of 15 Indians began digging a 2.5-foot deep trench to lay the stockmen's pipeline. Farrow informed Heaton that they would not turn the water on until the stockmen constructed cement or wooden troughs outside the reservation boundary for the water to run into. The cattlemen protested they didn't know how they were going to finance such construction as cattle sales had been so bad, which was indeed true. Heaton was incensed that Farrow had once again issued an ultimatum. Tensions escalated again over water. Heaton went to Kanab to meet with the stockmen where,

For some reason which I could not find out, they all blew up and I could not get any word or suggestion in that they would listen to. They even went so far as to suggest that they get their water from the main spring as they were owners of one-third. Some expressed that they had no faith in any of the Government Services and wanted to get as far away and have as little to do as possible with them.

This much I did tell them, that the Park Service did not work against the stockmen and that the water that the stockmen got was coming from the tunnel and from the division box to the west end of the ponds... [881]

Leonard Heaton was caught in the middle. Superintendent Pinkley advised him "to remain neutral in any controversy between the Indian Service and the Cattlemen." [882] The details of how this particular impasse was resolved are undocumented. The pipeline was completed and all tunnel spring water turned into it on September 4. By September 18 several leaks were repaired and the pipe was covered. By the time Heaton filed his monthly report on the 24th, the meadow pond was nearly dry.

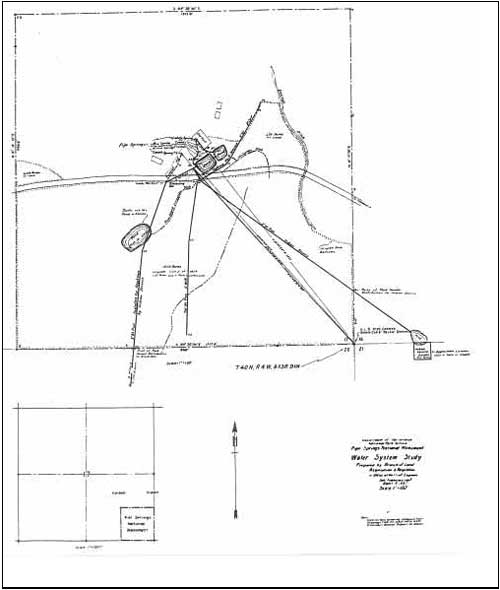

In August 1934 an allotment of $900 was given to Pipe Spring under the Public Works Administration program for completion of the monument road. Park Engineer Cowell and his wife spent several hours on September 21 at the monument so that Cowell could gather data related to the roadwork. During this visit, Cowell also delivered the long-awaited weir plate for the division box (it would still be more than six months before it was installed). Meanwhile, plans for the monument road were being completed in the Park Service's San Francisco office. In October Pinkley informed Heaton that the funds for the road were not sufficient to complete the road, parking area, and cattle guards. Pinkley wanted the cattle guards to be built first and then the parking area finished. That way, Pinkley explained, Heaton could begin the landscaping around the parking area. [883]

Heaton was already in a planting mode. In early October 1934, he reported that he was getting "more ground ready to set out more trees this fall around the campgrounds, and my sheds to the south." [884] Heaton later wrote to Pinkley of his plans to plant cedars and pines "to help take away the bareness of the land that has been farmed on [the] east side" and to gather and plant some cacti to "help nature to bring back the plant life on the monument..." [885] A dispute erupted over water between Heaton and Reservation Agent Parven E. Church in November when Church learned Heaton was using pond water to irrigate campground trees. [886] Heaton reported the incident to Pinkley, expressing annoyance that the "the Indian Service has made no attempt whatsoever this summer to use the water that has been running into their pipe, which for the most part of the summer has been about half of the water from the ponds by the fort." [887]

Also in October, the Mohave County Board of Supervisors wrote Superintendent Pinkley to request that a new road between Fredonia and Pipe Spring be built as "in wet weather the road is practically impassible." [888] As 19 of the 20 miles passed through Indian reservation and since tourists were the primary users of the road, the letter argued, couldn't a new road be constructed using 100 percent federal aid? [889] Believing the road might qualify as an approach road, Pinkley forwarded the letter to Cammerer and asked that a preliminary survey and estimate be directed to see if the road could be requested under emergency construction or other emergency funds. In December Park Engineer Cowell was instructed to prepare a map that showed the location of the proposed road. The map was prepared and sent to Pinkley at the end of December. [890] At least 90 percent had to cross government-owned land for it to qualify as an approach road. Cowell informed Pinkley that lands adjacent to the road were government owned, and with the exception of the monument, were all part of the Kaibab Indian Reservation. A more formal road survey for the Fredonia-Toroweap approach road was completed in 1937 and will be described later in this chapter.

The Second New Deal

In his annual message to Congress on January 4, 1935, President Roosevelt outlined a program of social reform that signaled the beginning of the second New Deal. The chief beneficiaries of this phase of the New Deal were labor and small farmers. Most of the projects were geared to the employment of manual labor. Congressional passage of the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act of 1935 on April 8, 1935, extended the ECW until March 31, 1937. The current size of the work force was 300,000. Roosevelt issued a directive on April 10 to double enrollment to 600,000. To achieve this increase, the maximum age limit was raised to 28 and the minimum lowered to 17. By the fall of 1935, however, Roosevelt instructed Fechner to reduce the ECW back to 300,000 men by June 1, 1936.

Roosevelt's sudden reversal on the size of the CCC workforce was linked to his efforts to make the ECW a permanent government agency. While his New Deal social and economic programs were attacked by a coalition of Republican adversaries, Roosevelt was overwhelmingly re-elected for a second term in the 1936 elections. Democrats vastly outnumbered Republicans in both the House and Senate. In his annual budget message to Congress for January 5, 1937, Roosevelt lauded the ECW's accomplishments and asked Congress to pass legislation establishing the force as a permanent federal agency. The new agency was to be called the Civilian Conservation Corps. Congress passed legislation on June 28, 1937, formally establishing the CCC, but it did not make it a permanent agency; it only extended its operations for three more years. Roosevelt signed the bill into law. The reduction of CCC camps continued throughout 1937 and 1938. In 1939 another attempt was made to make the CCC a permanent agency and failed. No large-scale reductions in camps took place in 1939, but some camps were phased out or relocated to other areas.

On December 31, 1939, Robert Fechner died from complications following a heart attack. His successor was James L. McEntee, formerly Fechner's assistant director. With the beginning of World War II in Europe during the spring of 1940, Roosevelt turned his attention to defense planning. The trend in 1940 was to reduce the number of supervisory positions in the camps, with regional offices assuming some of the supervisory duties. Many of the camp supervisors were reserve military officers who were withdrawn for active military duty. Two resolutions were introduced in the House of Representatives to require eight hours per week of military tactics and drill to CCC enrollees. Opposition prevented them from being passed. Director McEntee, however, revamped CCC training and education programs to meet some of the needs of national defense, such as shop, mathematics, blueprint reading, basic engineering, and other skills considered vital to national defense.

By 1941 the national defense program with its higher paying jobs was competing with the CCC program and it became harder to attract recruits. Beginning in April, further camp reductions were made. A program adopted in January allowed CCC youths to be excused from work five hours per week if they would volunteer an additional 10 hours per week in national defense training. In August rules were adopted to drill all CCC enrollees in simple military formations, but no guns were issued. Twenty hours a week or more were to be devoted to general defense training, eight of which could be done during regular work hours. In September the number of camps was reduced further. The establishment of new camps in areas with national defense projects took precedent over camps in park areas.

The country's entry into World War II on December 8, 1941, led to the termination of all CCC projects that did not directly relate to the war effort. On December 24 the Joint Appropriations Committee of Congress recommended terminating the CCC no later than July 1, 1942. Roosevelt argued it should be maintained as it performed needed conservation work and served as a training program for pre-draft-age youth. Meanwhile, McEntee ordered the closing of all camps unless they were either engaged in war work construction or in protection of war-related natural resources, to take effect at the end of May 1942. Congress refused to appropriate funding to continue the CCC program during the summer of 1942. Instead they voted sufficient funds to terminate the program. Termination was completed by June 30, 1943.

Pipe Spring National Monument was one of many Park Service sites that served as a site for a CCC camp. While many national park units had Emergency Conservation Work camps in them performing unprecedented levels of development, this was not to be case at Pipe Spring. Because the Park Service did not administer it, its usefulness, in terms of monument development, was limited. Work assignments for the vast majority of CCC enrollees residing at Pipe Spring would be mostly outside the monument rather than in it. Pipe Spring would experience all the pitfalls of being occupied by an army of adolescent boys and very few of the benefits. While the camp was constructed in July and August of 1935, the main contingent of boys would not arrive until November 1935. Meanwhile, there was much to keep Custodian Heaton and planning officials fully occupied. The following section describes monument activities that immediately preceded the establishment of the CCC camp at Pipe Spring.

Planning Continues at Pipe Spring

During the spring and summer of 1935, Heaton did what he could to complete projects begun by CWA crews. In March the monument road was graded and cattle guards were installed. [891] (This one-quarter mile road section was part of State Highway 40.) Then, with Superintendent Pinkley's blessings, Heaton left Grant Heaton in charge of Pipe Spring operations from April 6 through April 14 to make a tour with his wife Edna of southwestern national monuments. Their tour included Wupatki, Petrified Forest, Tonto, Montezuma Castle, and Walnut Canyon national monuments, as well as headquarters in Coolidge. His trip filled him with renewed appreciation for the "jolly high class of men and women willing to serve" in the Park Service, he later wrote Pinkley. [892] Upon their return, he and Edna started planning a second trip for the following year to visit the other 18 monuments in the Southwestern National Monuments system.

Monument development planning continued in order to take full advantage of any Public Works Administration funds or labor that might become available. During April 1935 the monument received a number of visits by high officials. Assistant Director Hillory A. Tolson visited, as well as Chief Landscape Architect Thomas C. Vint, Chief Engineer Frank Kittredge, Harry Langley, and A. E. Cowell. On April 4 Cowell and two assistants finally installed the weir ensuring the three-way division of the monument's water. [893] The following day Kittredge paid Heaton a surprise one-hour visit to inspect developments on his way to Zion National Park. On April 22 Tolson, Vint, and Langley spent two hours at Pipe Spring. While they were there the decision was made to relocate the campground and pit toilets south of the road, and to keep everything north of the monument road undeveloped to preserve a more natural and undisturbed setting for the fort. Everyone reiterated the need for a custodian's residence. Preliminary drawings for a custodian's residence were prepared by the Branch of Plans and Design and forwarded to Pinkley in mid-April. [894] The proposed stone residence was to be a public works project. Pinkley reviewed the plans and requested a few minor modifications.

During his visit, Harry Langley also reiterated the need for Heaton to restock the ponds with trout. He suggested Heaton contact officials in Salt Lake City to acquire more fish. Heaton did so, explaining to the official there that he had stocked the ponds in August 1927 with 5,000 fingerlings from the federal government. At the end of eight years, "I have only about 15 fish left," he wrote. [895] He inquired if he could get more fish to restock the ponds and estimated the ponds "would support 3,000 or 4,000 fish as the water is almost as full of water bugs as it can get and still be fresh." [896] Nothing came of the letter. Heaton pursued the matter again in September with Russell K. Grater, Assistant Wildlife Technician at Grand Canyon National Park, during his visit to Pipe Spring. Grater in turn, asked Pinkley for ideas but no restocking occurred that year.

In April 1935 Heaton wrote Superintendent Pinkley seeking permission to use spring water for his family garden. He asked, "Will there be any objections to the use of the water if I do not let the monument trees and meadow suffer, but just use that part of the water that is not needed for monument purposes?" [897] Pinkley had no objections and granted permission. At the same time, Heaton raised the question about his employment status - was he classified as Civil Service? Pinkley wrote to Director Cammerer about the matter. Hillory Tolson replied that Heaton could not obtain Civil Service status without passing an examination given by the Civil Service Commission. His appointment had been issued outside of the labor regulations, wrote Tolson. [898]

Park Engineer Cowell submitted cost estimates to Chief Engineer Kittredge for proposed public works projects for the monument on May 4, 1935. Eighteen projects were listed, including road work; construction of a parking area, campground loop road, service roads, and graveled walks (300 linear feet); placement of field stone barriers along roads and parking areas (2000 linear feet); clay surfacing camp sites; filling of wash at building sites; installation of a water and sewer system; construction of storm water drainage ditch; completion of boundary fences; improvement of grounds, fine grading, landscaping and planting; and restoration of the fort. The total cost for these projects was estimated at $11,135. [899]

Heaton reported to Pinkley in May 1935 that a meeting was held in which Grazing Service officials asked stockmen and citizens of the Arizona Strip how they would feel about the establishment of one or two CCC camps in the area. The question of sites came up and Pipe Spring was suggested as a possible site. Heaton later reported,

So these two men came out here to look the place over and three possible camp sites were selected... one at Moccasin, one at the southeast corner of the monument, and one four miles south of the monument where the stockmen's water is now piped to.

You will probably have word from these men before you get this letter as I referred them to you about the use of the monument for one of their camps. [900]

The Establishment of DG-44

On June 10, 1935, Director Cammerer received the following radiogram message:

Request authority to locate our DG Forty Four in Pipe Springs National Monument area northwest Arizona and to use approximately six thousand gallons of water daily from springs supplying the monument area (stop) Present capacity of springs now fifty-five thousand gallons per day (stop) Army recommend [sic]as only possible site (stop) Kindly wire answer - OTT Division of Grazing ECW Salt Lake City. [901]

The request was approved and plans proceeded for the Grazing Service to locate the CCC camp at Pipe Spring. A brief description of the camp's purpose is provided below, prior to a description of their operations.

The Taylor Grazing Act was passed on June 28, 1934. This was the first law ever passed by Congress to regulate grazing on the public domain. [902] The Grazing Service was established on July 17, 1934, to administer the Taylor Grazing Act. [903] Its objectives were conservation of natural resources by prevention of overgrazing, range rehabilitation by development of necessary facilities for efficient range utilization, stabilization of the livestock industry through cooperation with local stockmen, orderly use of the range, enforcement of trespass regulations, and enforcement of local rules on range practices. The establishment of the CCC provided the primary means by which the agency carried out its range improvements. Seven camps were allotted the Grazing Service in April 1935. By the end of fiscal year (FY) 1936, the agency administered 45 camps. Camps were established in 58 grazing districts in 10 western states. [904] Projects initiated and carried out from these camps were suggested and approved by the local advisory boards of the grazing districts who knew the most urgent needs of the districts. Projects included water hole construction, reseeding of burned over range, fence building, surveying and map making, construction of stock bridge and trails, erosion control, flood control, eradication of poisonous weeds and plants, and cricket and rodent control. [905] Much of Arizona's 10,685,000 acres of public land was suitable only for grazing. By 1936, grazing districts comprised 7,000,000 acres of the state of Arizona. [906]

The establishment of a CCC camp at Pipe Spring National Monument in July 1935 and its four years of operations there had considerable impact both on the monument's development and on its landscape. On July 20 Landscape Architect Alfred C. ("Al") Kuehl, Southwest Region, visited the monument with Park Engineer Cowell and the decision to relocate the monument's campground to the southeast part of the monument was confirmed. This required the Grazing Service to modify its plans and to site the CCC camp operations in the monument's southwest quadrant.

Heaton was notified that officers and 10 CCC enrollees were being sent to establish the camp in mid-June. On July 4, 1935, U.S. Army and Grazing Service officials came to Pipe Spring to decide on a site for the camp. At 1:00 a.m. on July 12, 10 trucks arrived with 24 more enrollees and two officers. These were advance men for Co. 3298, DG-45 and Co. 3287, DG-44. The boys from Co. 3298 remained at Pipe Spring until July 22, when they returned to Black Canyon, Arizona. The 12 remaining boys soon returned to California, replaced by 10 boys from Utah. Construction materials for the camp arrived between July 17-24, until 200,000 feet of lumber had been delivered. On July 24, 23 enrollees began the work of building the camp, joined by 10 more workers on July 25. Heaton reported to Superintendent Pinkley on that date, "The head boss says that in about three weeks the camp will be about finished. If they keep up the speed of yesterday and today I think the camp will be ready for the Eastern Boys by the last of August, if not before." [907]

In late June 1935, Heaton told Superintendent Pinkley that the three rooms of the lower house of the fort were not enough space for his growing family. He asked permission to move to the upper house of the fort. Pinkley denied the request, reasoning that a permanent custodian's residence for the Heatons would soon be constructed under the Public Works program. Pinkley, Harry Langley, and Al Kuehl, discussed the custodian's residence and decided to try to have it built from ECW funds. On August 1 Kuehl asked Chief Architect William G. Carnes to prepare estimates for the cost of materials for the residence. Estimates were submitted to him on August 7, with the cost estimate ranging from $3,021 to $3,586. (The higher figure was for an alternate plan including an additional room.) In late September Heaton informed Pinkley he planned to move his family to Moccasin for at least the school year in order not have to make the trip back and forth twice daily to the school. [908] The family did not actually locate a residence and move until late February 1936. [909]

By mid-August 1935, most of the CCC camp was built. It included: eight 26-men barracks, an administration/recreation building, mess hall, hospital, officers quarters, shower house, garage, six smaller out buildings, a "cooler," powerhouse, cellar, latrines, and tool shed - 20 buildings in all. Heaton reported, "They have used most of the old west field down to the stockmen's corral and part of the meadow, on the southwest corner [of the monument]..." [910] On August 17 a dance was held in the camp's new recreation hall. Attendance was 140 with people coming from the neighboring towns. "A very enjoyable time was had by all," Heaton reported. [911] No word had yet been received by Heaton on when the main body of enrollees would arrive.

What effect did the camp's establishment have on the carefully worked out water agreement between the Park Service, Indian Service, and cattlemen? On August 15, 1935, an agreement was reached between these three groups, the Grazing Service, and the Army that the camp's water supply would be provided by the cattlemen's share of water. The agreement stipulated that if the cattlemen's share proved insufficient the Park Service, Indian Service, and cattlemen would furnish an additional 6,000 gallons per day, each furnishing an equal share not to exceed 2,000 gallons per day each. [912] It is unknown if the Grazing Service paid for the privilege of using the cattlemen's water or if the cattlemen simply expected to benefit in other ways by having the camp in the area.

On August 25, 1935, a severe flood occurred on the monument. A storm "turned loose on us all the water that it could in about two and one-half hours, causing the largest flood that we have had in several years and doing us a lot of damage," Heaton reported the following day. [913] The flood deposited trash, brush, and sand on the monument, stopping up the head of twin culverts installed by the CWA. As a result, the new drainage wash filled with sand and turned the water into the old channel, washing out the service road to Heaton's barn and hen house and covering up or washing out most of the irrigation ditches on the east side of the fort. Heaton estimated damage at about $350. CCC enrollees later carried out much of the repair work, along with making improvements to prevent future flood damage.

The monument's CCC camp was constructed during the fifth period of the ECW Program (April 1-September 30, 1935). Other than the construction of the camp, no monument projects were worked on during that period. The sixth period lasted from Oct 1, 1935, to March 31, 1936. The work program for the monument submitted for both periods consisted of nine projects. Some were completion of projects begun by the CWA crews. All projects were part of the approved 1935 master plan for the monument. On September 21 Cowell visited the monument to go over with Heaton a list of projects to be accomplished. In mid-October Hillory Tolson sent Pinkley a list of projects in his region whose applications were disapproved for funding by the National Emergency Council. Among them was the monument's water and sewer system. Without this infrastructure, plans to build permanent buildings at Pipe Spring could not go forward.

The impact of President Roosevelt's "about face" on the size of the CCC was being felt at Pipe Spring. As mentioned earlier, President Roosevelt's April 1935 directive to increase the size of enrollment to 600,000, was followed that same fall by instructions to Director Fechner to reduce the ECW back to 300,000 men by June 1, 1936. On October 11, 1935, Acting Associate Director Hillory Tolson informed Pinkley of how the cutbacks in manpower would impact developments at Pipe Spring National Monument. The allotment for sixth period ECW camps had been reduced from 2,916 to 2,427 camps and a reduction from 600,000 to 500,000 enrollees nationwide. Hillory wrote,

All technical agencies have been forced to reduce the number of camps originally allotted to them for the sixth enrollment period and consequently approval of your sixth period program has been withheld until this definite information was made available within the last few days. Every effort should be made to complete our approved program, since it appears probably that a further reduction in camps will be required for the next enrollment period. [914]

Tolson approved the work program for Pipe Spring with several stipulations, including a $1,500 building limitation and requirement that projects had to have approved plans. Tolson also requested the boundary fence "not interfere with the movement of wildlife," that the walks be made of flagstone instead of graveled ("to be in keeping with old developments") and that only native trees and shrubs be used in landscaping the campground. As the Grazing Service was to finance work undertaken, Tolson told Pinkley his cost estimates would have to be approved by the Grazing Service.

In either late September or early October 1935, the small group of CCC boys and officers at the monument were transferred to Vayo, Utah, to construct another camp. [915] Heaton had the place to himself during the month of October. During that month, Superintendent Pinkley asked custodians to begin keeping a daily diary of their activities. [916] Heaton expressed his approval of the requirement, writing, "for the past 3 years I have kept a personal diary written up every night or at least every week.... With a daily monument diary one would not have to worry and stew about his monthly report." [917] Heaton had a short entry at the end of October, then began keeping a daily work journal that continued until his retirement in 1963.

Camp DG-44 was administered by the War Department, which oversaw nine corps areas. The company assigned to Pipe Spring National Monument was Company 2557. [918] Company 2557 was designated a 5th Corps Area, thus its enrollees could come from Ohio, West Virginia, Indiana, and/or Kentucky. The company's initial officers were Capt. Earl S. Jackson, Lt. Donald A. Wolfe, Lt. John J. Prokop, Jr., and Lt. Ralph W. Freeman (the camp doctor). Aland Forgeon was the camp's first educational officer. [919] On October 29, 1935, Capt. Jackson and a small advance group of enrollees arrived at Pipe Spring to get the camp in shape for the main contingent.

|

|

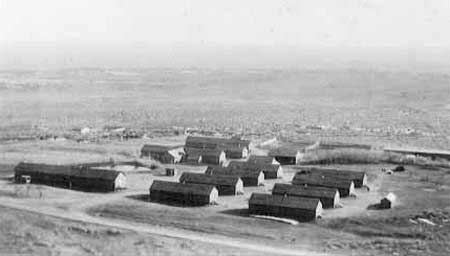

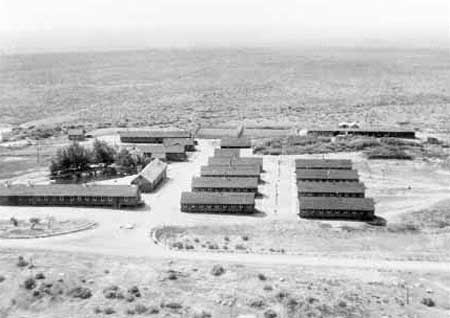

68. Early photo of Camp DG-44, ca. late 1935 (Pipe Spring National Monument). |

On October 31 Heaton received word that the CCC boys would arrive in Cedar City at noon the following day. At 8:00 p.m. on November 1, 180 junior enrollees from Ohio, Kentucky, and Indiana arrived at the monument from Fort Knox, Kentucky. [920] Heaton reported on November 23, "We now have the largest town in Mohave County north of the Colorado River, and all on a 10-acre lot." [921] The photo shown here (figure 68) was most likely taken shortly after the camp's construction. This early view of the camp does not show later stone curbing at the entrance (probably added in 1936) or the education building, constructed in March 1938.

In addition to the Army officers, a number of U.S. Forest Service men were employed as instructors, supervisors, and foremen to teach classes and to oversee work performed by enrollees. DG-44 had six such men during the sixth period, with Hamilton A. Draper serving as project superintendent. It was Draper and Heaton who oversaw most of the work performed on the monument. On November 25 Capt. Jackson was transferred to St. George, and Capt. Alma S. Packer assumed command of the camp.

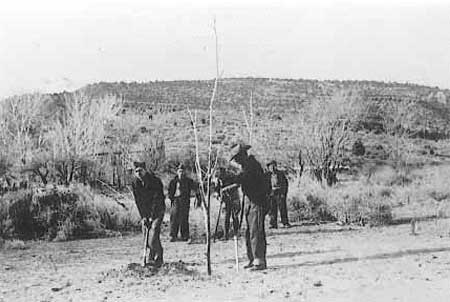

No Grazing Service projects were yet approved, so for the remainder of 1935 work focused on the monument. One group of 25 enrollees was immediately assigned to work on the monument. Another group worked on Hurricane-Fredonia road improvements. By Christmas 1935 Heaton reported the following monument projects either underway or completed: boundary fence, 65 percent complete; ditch diversion, 30 percent complete; flagstone walks laid out but not constructed (50 percent of the rock had been obtained). [922] Most work had been in the new campground area that had been staked out. [923] The following cuttings and/or trees had been set out in the campground: 25 Carolina poplars, 121 black locusts, 55 Lombardy poplars, 13 black cottonwoods, 5 ailanthus, 11 elms, and 32 silver leaf cottonwoods (153 total). [924] Some irrigation ditches were relocated and others were newly dug to irrigate campground trees.

T'was not all work and no play, however. During the sixth period, a tennis court, baseball diamond, basketball court, volleyball court, and boxing ring were constructed, presumably all within the monument. The camp owned an impressive amount of both indoor and outdoor athletic equipment, including two pool tables. Sports activities often pitched enrollees against boys in surrounding schools and communities. Boys attending Forgeon's journalism class published a bimonthly camp paper called The Pipe Post. The camp also had two libraries (one permanent and one traveling), and an upright piano. Just west of the camp barracks was the meadow pond that Heaton had built in 1926. Both are shown in figure 70, a photograph taken prior to the lining of the pool with sandstone.

Church services (one interdenominational and one Catholic) were conducted twice monthly by the district chaplain, in addition to two programs offered each month by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Three classes were held per day, five days a week. Classes were offered at three levels, elementary (reading and writing), high school (journalism, vocal music, history, shorthand), and college level (physiology, psychology). Vocational courses included baking, cooking, construction (building, concrete, road), photography, use of explosive powder, typewriting, and care and use of tools and trucks.

|

|

69. Trees being planted on the monument by CCC

enrollees, probably 1935 (Pipe Spring National Monument). |

|

|

70. CCC barracks with meadow pond in

foreground, late 1935 or early 1936 (Pipe Spring National Monument). |

The majority of enrollees attended the latter courses. Informal activities included woodworking, photography, drawing, drama, nature study, discussion groups, and safety meetings. Heaton too, assumed a new role, as he was asked to speak several times per month to the boys about the National Park Service and its sites (this was in addition to the fort tours he always gave whenever a new group of enrollees arrived). Not all the CCC boys were "happy campers," however. In early December, 21 enrollees were discharged for causing trouble and refusing to work. [925]

On November 21, 1935, four Ohio enrollees discovered Major John Wesley Powell's survey marker buried under a rock cairn north of the fort outside the monument boundary. Sealed within an old-style lye can was a rare and valuable hand-written document, a survey record left by Major Powell's expedition when they visited the fort in December 1871. The company doctor brought the document to show Heaton so that he could make a record of it, as the boys were claiming ownership of their valuable "treasure." Heaton reported the find in his monthly report to Pinkley, who included it in the Southwestern Monuments Monthly Report for November 1935. Upon reading of the discovery, Acting Chief O. T. Hagen, Branch of Historic Sites and Buildings, Western Division, immediately wrote Heaton and sent him a copy of the Antiquities Act of 1906. Hagen wrote,

The finding by CCC enrollees of the marker... is of such importance as to require immediate attention.

No doubt, Superintendent Pinkley has already advised you of the proper procedure for the retention of the document....

In historical and archeological areas, all materials found have been considered as property of the National Park Service and not as that of the finder. The enrollees should be made to understand this and also that unauthorized digging or excavating is unlawful. [926]

Hagen requested a photographic copy of the document. On December 21 Heaton attempted to reconstruct the Powell survey marker monument as best he could. He noted several sets of initials on several of the rocks and surmised they were placed there at a later date. Heaton provided a description of the location of the marker in his December report to Pinkley and suggested that the monument boundaries be extended to include the marker as well as to "take in the old Indian ruins just south of the monument." [927] This suggestion would be echoed again and again by others in years to come.

1936

During January 1936 monument work continued on two projects: laying the walkway from the east cabin to the fort and construction of a diversion ditch. Heaton suspended completion of the walk on February 13 when his crew of boys uncovered what Heaton soon suspected to be the site of the Whitmore-McIntyre dugout. The boys continued to excavate under Heaton's supervision the following day until Heaton's suspicions were sufficiently confirmed by finds of broken crockery, animal bones, a mule shoe, burned rock, and other materials. Heaton then stopped work and reported his find to Al Kuehl and Superintendent Pinkley, asking them for directions. Assistant Superintendent Hugh Miller telegramed Heaton from Coolidge, "Park Service regulations prohibit excavations by Rangers and Custodians therefore you cannot continue work described in your letter February sixteenth. Fill trenches made to prevent damage by rains and snow." [928] The alignment of the walkway was subsequently rerouted to avoid the archeological site, which was not excavated until 1959.

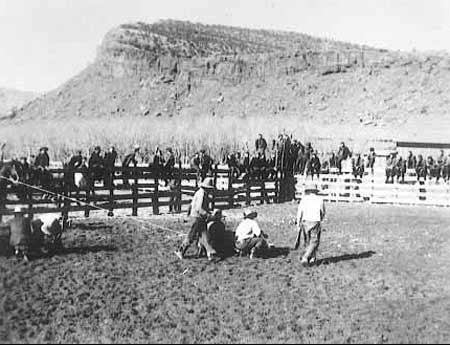

For many CCC enrollees, their time at Pipe Spring would be their first contact with Native Americans. Imagine their surprise to meet Indian cowboys and watch them in action! There are several photographs of Kaibab Paiute men with CCC enrollees, but very little written about the circumstances under which they came together on the monument.

|

|

71. Morris Jake, Dan Bulletts, and CCC enrollee

Bernie Effler, 1936 (Photograph by Jack L. Harden, Pipe Spring National Monument). |

In February 1936 the Heatons moved out of the fort and into a place in Moccasin. Heaton wrote in his diary, "I feel like now I can really show the monument.... As I have only one room fixed up as an office and all the rest will be filled with relics and museum stuff." [929] As Heaton took note of the 10th anniversary of his working at Pipe Spring, he wistfully recounted some of the changes that had taken place over the years:

Once [this was] a place of activity for cattlemen and the watering of hundreds of cattle, now none are allowed to come near the water.

Once a stopping place on the main highway between Zion and Grand Canyon Parks with a yearly travel of 26,000, now only a few hundred.

Once, irrigation of 15 or 20 acres, now only the meadow and shade trees to beautify the monument.

Once buildings in a falling down state, now practically restored to the condition when built.

Once rooms barren of all furniture of pioneer life, now a few pieces of prehistoric Indian and pioneer relics are placed to break the barrenness of them.

Once a poor place for campers, now the beginning of an ideal campground.

Once a poor road which took hours to get over, now it takes only minutes.

Once the wind blew and the stoves and fireplaces smoked with every breeze, and IT IS THE SAME TODAY & IT WILL ALWAYS BE SO IN THE FORT.

All in all, I have enjoyed my life here at the Monument very much and hope that I will be able to continue my services for some time to come. [930]

|

|

72. CCC enrollees watching Kaibab Paiute cowboys

dehorn cattle in monument corrals, undated (Photograph by Leonard Heaton, Pipe Spring National Monument). |

|

|

73. Dan Bulletts and John Boyce, January 23,

1936 (Photograph by Leonard Heaton, Pipe Spring National Monument). |

In March 1936, approaching the end of the sixth period, Camp DG-44 was formally inspected by J. C. Reddoch. The primary work of the camp during the sixth period had been monument landscaping, his report stated. Outside the monument, the chief project had been road maintenance and construction. Commander Packer told Reddoch that he was of the opinion that the enrollees discharged in December "were Communistically inclined," even though no Communist propaganda could be found in their possession. Reddoch concluded the boys just wanted to go home. He reported that the morale and spirit of the 180 remaining boys was "good." [931]

For the first three weeks of March 1936, Heaton performed guide work at Casa Grande National Monument, leaving the monument under the care of Ranger Donald J. Erskine from Zion National Park. Landscape architects Harry Langley and Edward L. Keeling visited on March 11 to go over ECW projects. The diversion ditch, monument fencing, and leveling of the parking area had all been completed. Completion of the walkways had been held up by the discovery of the Whitmore-McIntyre dugout. Despite all the work that had been accomplished, Ranger Erskine's report to Superintendent Pinkley at month's end suggested serious trouble was brewing between the Army and the Park Service. Erskine was living at the monument "at the courtesy of the officers," he reported in March, sharing their quarters. Thus he had a first-hand look at what went on in the camp 24 hours a day. He expressed serious reservations to Pinkley about the camp officers, stating,

I feel that I should go on record as stating the situation here truthfully. The officers of this CCC camp could not be less cooperative with the policies of the National Park Service as it pertains to the camp and the surrounding area. Capt. Packer has shown no inclination to cooperate anyplace where he has the slightest wish on his own part for a result contrary to what we desire. [932]

Langley, for example, had asked that a road system be laid out in the camp area in order to preserve what little remained of vegetation. Packer shrugged off Erskine's frequent reminders of Langley's request by saying the Army and Park Service had a difference of opinion. Erskine was also told by some of the CCC boys that officers were shooting birds on the monument. Upon his return, Heaton wrote in his journal,

There seems to be some friction coming up between the Army officers and the policies of the Park Service, and the Captain, Mr. Packer, wants to have his way regardless of what the NPS has in its program for the development of the monument, so maybe we will have some excitement yet. [933]

A few days later Heaton wrote, "Had a long talk with Captain Packer and he is getting more determined to have his own way and insists on telling me how I must run this monument, and they are mostly Army methods..." [934] Three days later, Heaton wrote in his journal,

Did some cleanup on the east side of the meadow to please Captain Packer, who keeps suggesting things and how the monument should look like a DANCE FLOOR.... We also discussed the water and the making of a swimming pool in the meadow where the old pond is. I told him that I did not think there would be enough water to keep it fresh unless there was put in cement or rocks to hold the seepage... [935]

(Recall that two years prior to this, the idea of lining the meadow pond with stones or cement had already been discussed between Heaton and Pinkley as a way of conserving tunnel spring water; no funds were available at the time, however. No doubt, Heaton was delighted to have the Grazing Service do this at no expense to the monument, albeit for different objectives!)

|

|

74. CCC enrollees placing line fence: Hemsley,

Wright, Boyce, Effler, and Bill Thompson, February 26, 1936 (Photograph by Leonard Heaton, Pipe Spring National Monument). |

|

|

75. Diversion ditch under construction by CCC

enrollees to prevent flooding of campground, probably 1936 (Photograph by Leonard Heaton, Pipe Spring National Monument, neg. 165). |

As the end of the sixth period neared (March 31, 1936), Heaton found it increasingly difficult to get much work out of the enrollees who were about to go home. This was a time when boys were also most likely to search about for souvenirs of their stay at Pipe Spring, such as the illegal gathering of cactus or the pilfering of museum artifacts. Or they found a way to leave their "mark" at the monument - inscribing their names or initials into historic buildings was a common method. Some boys didn't wait to go home, mailing horny toads and lizards caught during their monument stay. [936] Others found and killed snakes for their skins, which they sent home or put on their belts. Rattlesnakes in particular were killed on sight.

Heaton's monthly accounts of such activities, included in the Southwestern Monuments Monthly Report, distressed Acting Chief Victor H. Cahalane, Wildlife Division, who wrote Superintendent Pinkley asking him to have Heaton call to the attention of enrollees the monument's responsibility to preserve and protect native wildlife. Heaton enlisted the camp commanding officer's aid in an attempt to dissuade the boys from their more destructive activities. "There are one or two who have been raised out in the open that can't see any good for any living shake or smaller animal, only to practice on with a rifle or rock," Heaton wrote Pinkley. "I might confess," he continued, "that I was that way till I began to study the life and use of wild animals to man, and this has mostly all happened since I have been working for the National Park Service. I surely have repented of my evil ways of taking the life of such harmless creatures, and get after everyone else that delights in killing the same." [937]

Heaton's heightened sensitivity toward monument wildlife, however, did not apply to domestic pets living on the monument. He frequently expressed his frustration in dealing with cats and dogs brought into camp by CCC boys or Army officers and their families. Heaton grew to intensely dislike these animals for the damage they did to the wildlife and regarded them as a nuisance. Moreover, boys and dogs chased down his domestic geese until none were left. Cats broke into his bird traps killing the birds. When a grader ran over a dog in late April, Heaton wrote in his journal, "Well, this saved me the job. I wish the same thing would happen to the rest of the dogs hanging around here." [938] It is also not uncommon to find a Heaton journal entry during this period that reads, "Got rid of another cat last night." Even Pinkley sympathized with his plight but cautioned, "You are quite right to kill the house cats, though if the Army should bring cats to the monument I would rather you would talk the policy over with them before doing anything which would result in antagonism." [939]

While Heaton thoroughly disapproved of the mailing home or killing of wildlife, he never objected when the boys caught reptiles and delivered them to his earlier brainchild, the monument's caged reptile exhibit. Not all captured reptiles were kept for exhibit, however. In an attempt to monitor wildlife at Pipe Spring, Heaton developed a unique, "digital" method of marking, releasing, and tracking lizards. On March 30 he wrote in his journal,

I got the bird traps set, three of them. About noon I caught three chipmunks, two English sparrows and one Stephegers Blue-bellied Lizard and marked it by cutting off one of its toes. By this system of marking I will be able to mark a lot. The system is cutting off a different toe each time and keeping a record of each individual lizard. [940]

While Heaton was busy thus "marking" lizards, temperatures were starting to climb and CCC enrollees became hell bent on converting the meadow pond into a swimming pool. Meanwhile, they cooled off by taking dips in the fort ponds. A cat and scraper were used to slope the sides of the meadow pond. In late April 1936, Heaton reported to Pinkley, "The Army is now working like beavers to get the meadow pond in shape for a swimming pool. It is being lined with flagstone rock and cement in the cracks, so it ought to be almost water tight." [941]

Assistant Director Conrad Wirth, chief of the Branch of Planning, visited the monument with his wife on April 20, 1936. Wirth met with ECW Superintendent Draper to discuss work projects and to get his assurance that enrollees would continue to be available for monument work. (The Grazing Service thought the boys were only to be used by the monument for the sixth period.) Draper later told Heaton he could have 10 boys whenever he wanted them but that the monument had to buy its own materials for projects. More often, no more than eight boys were available.