|

Pipe Spring

Cultures at a Crossroads An Administrative History of Pipe Spring National Monument |

|

PART VI:

THE WORLD WAR II YEARS

Introduction

The entry of the United States into World War II created critical management problems for the National Park Service. Congress cut park appropriations by more than 50 percent. Between June 30, 1942, and June 30, 1943, the number of permanent, full-time positions in the Park Service was reduced from 4,510 to 1,974, a cut of more than 55 percent. With the imposition of gas rationing, visitation fell dramatically; all travel promotion activities within the agency ceased. Even the railroads abandoned their policy of putting on special supplemental trains and reducing rates to the parks. Total visitation to national parks and monuments for 1942 (the first travel year after the country went to war) fell by 55 percent. [1166]

For the previous decade, the Park Service had derived incalculable benefit from the labor of the Civilian Conservation Corps and other public works programs. All CCC camps were ordered closed by June 30, 1943 (as discussed in Part V, Pipe Spring National Monument lost its camp considerably earlier, much to Custodian Heaton's relief). The loss of CCC camps and their work crews from the National Park Service and U.S. Forest Service units was only slightly ameliorated by the Selective Service's establishment of Civilian Public Service camps, manned largely by conscientious objectors. [1167] Now, in addition to the cessation of these work programs, finding qualified or experienced men to hire became a difficult challenge because so many men joined the military or became otherwise involved in the war effort. In fact, some parks became so desperate that they - like private industry - began hiring women in positions previously reserved for men, as rangers and fire lookouts.

A minimal staff of engineers, landscape architects, and historians was retained in the Washington office and four regional offices in order to maintain certain basic functions and to continue the work of planning for future developments. Certain other activities, however, ceased to function at all during the war years, such as the Historic American Buildings Survey. To make matters even more complicated, the offices of the National Park Service, as well as two other services, were moved from Washington, D.C., to Chicago in 1942 to make room for military functions in the nation's capitol. They were not moved back until 1947.

Some parks were heavily impacted by wartime activities, particularly by military demands for their natural resources. Secretary Harold L. Ickes called on the various bureaus in his department for "full mobilization of the Nation's natural resources for war..." [1168] Fortunately, Pipe Spring National Monument had absolutely nothing the military needed or wanted. Nonetheless, the war's impact was felt in a number of ways. The worst drop in monument visitation since the opening of the Zion-Mt. Carmel Tunnel occurred during the war years. Perhaps of even more significance to Pipe Spring was the transfer of the monument's administration from Southwestern National Monuments (Southwestern Monuments) to Zion National Park. Although Custodian Heaton then faced an unprecedented number of official inspections, property inventories, and lectures on how to do things "right," he responded with his characteristic humility and desire to do whatever was asked of him. As in other park units, monument development plans were executed, reviewed, and commented on, to be put "on the shelf " until the war's end. Historical research continued, particularly as Zion officials asked new questions about the importance of the monument's historic landscape. Progress continued in transforming the fort into a historic house museum. Road issues continued to be debated during the war years, whether discussions centered on the monument road or the only sporadically maintained approach roads from east and west. Finally, the question of water rights at the monument was revived again, precipitated by a federal ruling in 1942 on water reserves and park units.

Otherwise, life at Pipe Spring went on pretty much as usual, with the local folk continuing to gather at the site to picnic in view of the old Mormon fort and under the shade of its many trees. There was another important attraction, of course. Now that the monument's water was no longer demanded by the Army for CCC camps, local Mormons and Indians alike were welcome to cool off in the meadow pool, an opportunity many took advantage of during the hot, dry summers that were characteristic of the Arizona Strip.

Monument Administration

The end to all CCC-related activity at the monument in 1940 left Heaton alone responsible for maintaining and protecting Pipe Spring National Monument. Park Service funds were scarce and visitation low in park units nationwide during World War II. Consequently, no major projects were undertaken at the monument. Only minor maintenance or stabilization work was performed on historic or other buildings. [1169] Most of Heaton's time was spent in performing routine maintenance and protection work - repairing fences, cleaning irrigation ditches, reducing fire hazards, tree pruning, and keeping the campgrounds in an orderly condition. Heaton's two oldest sons, Clawson and Dean, often helped with such work during the war years. [1170]

Although development planning for the monument continued during the war years, no building projects were undertaken. Zion and regional office staff made studies for campground development at the monument. A number of NPS officials visited Pipe Spring during the war years, including Director Newton Drury, Regional Director Minor R. Tillotson, Regional Chief of Planning Harvey Cornell, Regional Architect Lyle Bennett, and Chief Landscape Architect Thomas C. Vint. [1171] The visits were made to inspect the monument and to plan post-war work on buildings and a parking area, residence, and utility area. Heaton wrote after their visit, "Promised to get the residence building, but I expect it to be some time." [1172]

For the month of January 1942 Heaton reported, "Not a visitor this month. Looks like the ban on tires and cars will stop visitors to the monument an awful lot for the next few years." [1173] That was not to be the war's only impact on the monument. Southwestern Monuments' Superintendent Hugh Miller was still on his three-month tour of duty in the Washington office. In early January Miller formally notified Chief of Operations Hillory A. Tolson of a change of mind:

You are familiar with my opposition to the transfer of responsibility for the administration of Pipe Spring National Monument from the Superintendent of the Southwestern National Monuments to the Superintendent of Zion National Park. Circumstances related to the war economy appear, however, to have changed the problem to such an extent as to warrant a change in my position with respect to it.

In view particularly of the necessity of restricting automobile travel it would now appear to be in harmony with the policy of the administration to place Pipe Spring National Monument under the Superintendent of Zion National Park and this memorandum expresses my concurrence in the proposal. [1174]

On January 24, 1942, Heaton received word from the regional office that the administration of the monument was to be transferred to Zion National Park. He described this news in his journal entry that day as being "a bomb in the mail." [1175] He wondered what changes would take place and how he would fit into the new organization. As Heaton waited to learn the date the transfer was to take place, he filed his last monthly report to headquarters in Coolidge:

For sixteen years I have been making reports to the Superintendent of Southwest [sic] National Monuments, and it is with no little regret that I think of having to make them to another. Not that I have anything against the other outfit, but I have been so long with the Southwestern Monuments and watched it grow from a traveling office in the old Ford with the Boss to the well-equipped building and staff of a dozen men at Coolidge. After 16 years living with such an outfit there are certain bonds of affection attached with it and friendship that has grown... [1176]

Director Drury issued the memorandum directing the transfer on January 13, 1942. The administration of the monument was formally transferred to Zion on February 16, 1942. [1177] (In addition to administering Zion National Park and now Pipe Spring National Monument during this period, its superintendent oversaw Cedar Breaks National Monument and Bryce Canyon National Park. [1178] ) After the transfer, Heaton's monthly reports to Zion's Superintendent Paul R. Franke took on a more formal and succinct format, rather atypical of Heaton's earlier "chatty" (and more entertaining) reports to Southwestern Monuments. [1179] The custodian described a day spent in the office typing out his monthly report as "my most tiring day's work." [1180]

During the slow winter of early 1942, Heaton painted fort woodwork with linseed oil and worked on remodeling and making repairs to his residence. He received the preliminary plans for the approved new residence in February. [1181] It was to be a handsome, three-bedroom, stone residence located just a short distance east of the meadow pool. (This structure would never be built, but the plans must have given the Heatons a small ray of hope to hang onto.) On March 16, 1942, Heaton made his first official trip to Zion to meet with Franke and the other park staff. The trip via Short Creek was 50 miles; via Kanab it was 61 miles. Either way, the one-way drive - just the first of many he would make - took two hours. [1182] On March 23 he went to Zion to discuss park business and to attend a weekly class. These were being held each Monday night in the rangers' building. [1183] Class that week was on the rating system. Afterward Heaton wrote in his journal, "I can see that I will have to keep on my toes and work up if I hold the rating given me by the Southwestern Monuments." [1184]

|

|

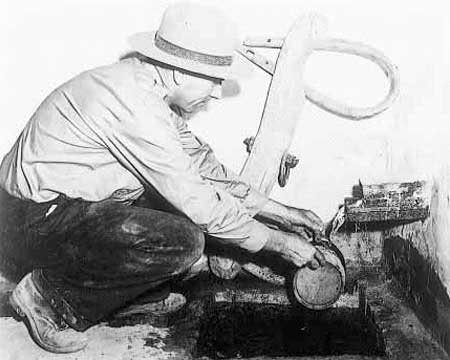

86. Custodian C. Leonard Heaton in spring room of

the fort, ca. 1942 (Pipe Spring National Monument). |

Franke made his first official inspection visit to the monument on March 28, 1942, and spent two hours going over the site discussing problems and reviewing the monument's master plans. Among the proposals that Heaton and Franke talked about that day was planting part of the land back into orchards and gardens; cleaning the ponds and restocking them with fish; furnishing the fort rooms using some of Zion's museum collection; constructing a checking station and comfort station; and changing the location of service roads. Franke told Heaton he would try to visit once a month.

The war years brought a number of servicemen to Pipe Spring National Monument and other park units in the surrounding area. In his first annual report to the Secretary of the Interior since the beginning of the country's involvement in the war, Director Drury emphasized,

In war, no less than in peace, the national parks and allied areas have served as havens of refuge for those fortunate enough to be able to visit them. Proving an environment that tends to give relief from the tension of a warring world, the parks are being looked upon as a factor in a program of rehabilitation, physical and mental, that will be increasingly necessary as the war progresses. [1185]

While he had to report a significant decline in attendance to park units, Drury was obliquely making a strong argument for their "usefulness" to the war-effort. [1186] Perhaps to collect supporting evidence of park units as psychological havens for war-weary soldiers, all parks and monuments were required to keep a record of visits by members of the U.S. Armed Forces during the war years. No such visits were recorded at Pipe Spring until December 1942, when 12 soldiers visited the monument. These men, like many others who either passed by or visited the monument during the war years, were sent on detail to the area from their military base in Kingman, Arizona, to remove the three area CCC camps. [1187] The men temporarily lived at the Fredonia camp while they completed taking down the Antelope Valley camp (G-173) in May and June 1943. The Short Creek camp was also removed about this time. It is presumed that the Fredonia camp was the last to be removed. When servicemen came to Pipe Spring, they nearly always toured the fort and often picnicked in the campground. This helped boost the monument's lean travel figures as well as brought young men into contact with a part of United States history they might never have otherwise been exposed to.

With the German Luftwaffe's aerial bombings of Great Britain in 1940 still fresh in people's minds (not to mention Pearl Harbor), the war had many in the country on edge. Some may have glanced skyward perhaps a little more often than usual for unaccustomed airplane activity. On April 9, 1942, Heaton reported something quite out of the ordinary:

Witnessed one of the most unusual sights in the sky at about 10:30. Heard an airplane flying from west to east, north of the monument. Shortly after it had passed, a white stretch of smoke or clouds started to form, beginning north of the monument and going east, something like the smoke writing from an airplane. But this was white like a cloud and stayed in some shape for 10 to 15 minutes, then small shafts and mists began to drift northward and it did not entirely disappear for at least 1? hours. It appeared to be like a ball being thrown through the air and one could see the clouds forming. At first we thought it might be a plane on fire, but not black enough for that. It is my opinion a cold shaft of air was hurled through the air that formed the cloud, maybe in the trail of the plane. The cloud or smoke turned out to be a flame. [1188]

The cause of the mysterious cloud in the sky is not known. Heaton enjoyed a much more familiar sight in late May, when he wrote in his journal, "Another of those hot dry, windy and dirty days. About like old cattle days at the south side of the monument today. The Indians are branding the calves. With the bellowing of the cattle, shouting of the riders, and smell of burnt hair, makes one think of days gone by." [1189] The old cattle corrals were still in use, only now by Indian stockmen. In December that year, Heaton reported the Indians held a bunch of calves at the old stock corrals. [1190]

The Heatons seemed to have gotten along well with their neighbors, Indian and Mormon alike. When anyone got in trouble or found others in that state, it was customary that whoever was closest helped out as much as possible. For example, when Custodian Heaton's truck became mired in the road one day, two Indians on horseback towed him out. Another time, eight-year-old Bill Tom was injured when the horse he was riding fell and Heaton gave him first aid. He then had one of his sons accompany the Kaibab Paiute boy home. [1191] Heaton's daily journal routinely reported such examples of mutual aid. [1192] The "neighbor" problem most often encountered at the monument was rabbit hunting. In June 1942 Heaton reported, "Stopped Joseph Jolmary, an Indian, from shooting rabbits on the monument this morning. The hunting of rabbits is my biggest trouble with the local people, especially the Indians, who make the rabbit one of their main dishes at the table and there are a lot of rabbits on the monument." [1193] The rabbits, of course, knew a lush playground when they saw one. Besides, hunters hemmed them in on all sides, both Indian and non-Indian. Heaton reported several years later, in May 1944, "The rabbits are not much more than holding their own as the Indians and hunters are after them for their meat. This hunting is being done on the Indian Reservation." [1194] Heaton also reported coyotes were being heavily hunted, considered a menace to the ranchers' lambs and calves.

Rabbits weren't the only furry animals abundant at the monument. Particularly during dry summer weather, a large number of squirrels, chipmunks, rats, and mice could be found at Pipe Spring, being attracted to its water and abundant vegetation. Porcupines, too, lived at the monument; their habits were harmful to certain trees. [1195] In spite of cattle guards, reservation horses and cattle also wandered onto the monument to graze or to water. Other monument residents were gophers. These animals were especially destructive pests in Heaton's eyes, as they damaged tree roots and wreaked havoc on his system of irrigation ditches. (Heaton attributed the monument's loss of several Carolina poplars in 1945 to gophers and disease. [1196] ) While gophers did all of their dirty work underground or at least out of doors, mice and rats munched away on antique furnishings inside the fort. In May 1944 Heaton wrote, "...sure need some rat poison as the mice and rats are so thick around buildings that they cover up all tracks with their running around and are building nests everywhere they can find a dark corner to get into." [1197] There was one other pest that Heaton fought during the summer - ants. His customary extermination method involved pouring about a quart of gasoline into each ant bed then covering it with a sheet of newspaper. If all the ants were in their hole when this ritual was performed, Heaton reported, two applications usually did the job. Even wartime gas rationing didn't stop the monument custodian from using this tried-and-true method of pest control.

One good thing about the war years, now that all the area CCC camps had been abandoned, Heaton was free to refill the meadow pool. In mid-June 1942, Heaton had his sons clean out the pool so that the family and neighbors could cool off by swimming. That Fourth of July, 30 people came to spend the afternoon in the shade of the trees and to swim. Indian children also came from time to time to swim in the meadow pool. [1198] The pool was especially welcome that summer. Heaton reported in his daily journal, "It has been a number of years since we had so much hard west wind and so long. Everyone is on edge. I don't remember when I have been so tired and hate the weather as I have of this continual, hard, west wind. Never a day but what one has to fight the wind to get anything done." [1199] In spite of the unpleasant weather, Heaton managed to get a few things accomplished. During that summer the south wall of the west cabin was stabilized and monument boundary fences were repaired, along with other routine maintenance work. [1200]

In September 1942 Franke paid a surprise visit, bringing with him Landscape Architect John Kell from the regional office, introducing him as Al Kuehl's replacement. The men inspected the work Heaton had done on the west cabin and made recommendations for future mortaring work. Kell later filed a report to Harvey Cornell, suggesting ways the monument's master plan might be modified if a bypass road was ever constructed south of the monument. Kell thought development should be moved away from the fort in order to achieve a more natural setting for the historic buildings. "It was my impression," reported Kell," that there was an abundance of tree growth in the headquarters area." [1201] While he had no objection to the older "historic" trees being retained, Kell recommended removal of some of the smaller ones, especially those that had sprouted up along irrigation ditches.

Franke brought up the landscape issue again two months later in a memorandum to Regional Director Tillotson commenting on monument development plans. The superintendent referred to conversations he had during the summer of 1942 with Randall Jones, tourism booster of southern Utah and northern Arizona for nearly 40 years. Jones had questioned the Park Service's policy of "turning the area into a natural national monument by over-planting with trees and shrubs." [1202] Later Franke started asking questions of the old-timers and reviewing monument correspondence to learn what official policy was on the monument landscape. While there was no question that the Park Service was charged with the preservation of the historic buildings, Franke wrote Tillotson, no commitments had ever been made to preserve or restore the landscape as it was during the historic period. He proposed that part of the landscape be made to look like a typical pioneer ranch - what today would be called a "type" reconstruction, rather than an accurate restoration. Franke wrote,

What has happened to the rail fences, the orchards, gardens, and livestock pasture? Surely they were part of the ranching, dairying, and farming period of 1870 to 1890. In place of maintaining them we permit and encourage the area to develop into a false jungle of alien cottonwoods, willows, box elders, and other specie never part of the pioneer ranch, whose major objective was producing foodstuffs...

We concur in general with the plan giving location of proposed new developments. We suggest there be a general line of demarcation, providing to the east of this line an area for parking of cars, checking station, comfort station, and public campgrounds. To the west of this line we suggest that the landscape be returned to the ranching, farming, dairying, and fruit raising pioneer period of 1870 to 1890. [1203]

Franke stated that in the western part of the monument Heaton should be encouraged to cultivate fruit trees, gardens, and grain fields. "The proposed residences and utility buildings should be architecturally designed to appear as outbuildings of the farmyard but not for public visitation," he added. [1204]

This new plan would have required a complete redesign of the dignified stone custodian's residence (whose final plans had already been approved) into something resembling an agricultural outbuilding, or at least into something no visitor would ever be tempted to set foot in! What is also noteworthy about Franke's proposal - somewhat indicative of his ignorance of past planning decisions made at the monument - is that whereas the decision had been made in the early 1930s to distinguish the historic from non-historic areas by a north-south demarcation (with the monument road being the boundary), now Zion was asking for an east-west bifurcation of the two areas. The general area where Franke wanted to see the new parking area constructed, east of the fort, was the area where earlier planners excluded the campground in order to preserve the fort's historic setting.

In early January 1943, Tillotson wrote a lengthy response to Franke. "The general approach outlined in your memorandum of December 23 is undoubtedly the correct one," he wrote. [1205] Tillotson asked what historical evidence existed for installing orchards, gardens, pastures, etc.? In the absence of historical evidence, he saw Franke's policy as "largely one of type restoration or general period restoration, rather than exact reproduction..." Tillotson also expressed concern about the upkeep of such an agricultural operation and wondered if a "living museum" arrangement with farming and dairying activities carried out by people living at the place might be a solution. "This might or might not be considered desirable and practicable," he added. Tillotson remarked on the absence of a place for interpretive exhibits, supplemental to the period restoration in the fort. He added,

...we hope to be able to give this project the necessary time and historical research to carry out a development program along the general lines you have suggested in such a manner that it will be a credit to the Service and meet with the approval of all concerned, including the Mormon Church and the local old-timers. With this in mind, it will be of immense help if you will gather and assemble all the information and evidence possible as to the original appearance of Pipe Spring and the surrounding gardens, orchards, fences, fields, outbuildings, etc. [1206]

Acting Supervisor of Historic Sites Herbert E. Kahler wrote Tillotson a few weeks later regarding Franke's proposal and Tillotson's response. In order that the interpretive program be historically sound, Kahler recommended that a historical base map, an interpretive statement, and a detailed historical narrative be prepared and included in the next edition of the monument's master plan. [1207] Oddly, no one raised the question of water and how much would be needed to sustain an operation of the kind Franke was proposing.

|

|

87. Charles J. Smith, superintendent of Zion

National Park from 1943 to 1952, undated (Courtesy Zion National Park, neg. 4287). |

At Franke's suggestion, Cornell held certain development plans in abeyance, "pending an investigation which may or may not lead to the inclusion of such features of historical significance as orchard, garden, hitching posts, rail fence and the like." [1208] Franke, on the other hand, set about gathering (with Heaton's assistance) whatever historical information could be found on Pipe Spring's history. This effort included contacting anyone who could be found who had old ties to the site and interviewing them for information, particularly about early agricultural operations and the appearance of the landscape. This information was then forwarded to Park Service temporary headquarters in Chicago where it was passed on to the Branch of Historic Sites and Buildings for its use in the preparation of a historic outline.

Meanwhile, everyday life at the monument in the early war years went on. In the fall of 1942, Heaton took extended sick leave from October 6 until early November to undergo surgery. During this time his wife Edna was in charge of the monument. [1209] On October 24 the monument's trash dump caught on fire. [1210] The fire was started accidentally by his children emptying hot ashes onto the dump. Edna and the children, with the help of Charles and Maggie Heaton (who happened to be passing by), were able to put out the fire before it spread further. The most common fire hazard at the monument was dry foxtail grass. Leonard Heaton tried to reduce the fire risk by routinely cutting or burning the grass and other weeds around the buildings.

The monument received some good publicity with the publication of Jonreed Lauritzen's article, "Pipe Spring, A Monument to Pioneers" in the February 1943 issue of Arizona Highways. Lauritzen was a resident of Short Creek, Arizona, and the son of Short Creek's founder, Jacob Lauritzen. He obtained his dates and other facts used in the article from Leonard Heaton in May 1942. [1211] When they viewed the old fort at Pipe Springs, Lauritzen assured his readers, visitors would "think of men and the struggle they had to bring this wilderness under control." [1212] The monument "in its homely strength and simple dignity typifies the life and character of the early Mormon," the author wrote, a view shared by other descendents of 19th century Mormon settlers. [1213]

On June 13, 1943, Heaton learned that Franke was being transferred from Zion National Park to Grand Teton National Park. (Franke would return to Zion in 1952 to superintend it for the remainder of the decade.) While making a supply run to Zion a few days later, he learned Franke's replacement was to be Charles J. Smith, previously superintendent of Grand Teton National Park. Heaton met Smith and Assistant Superintendent Dorr G. Yeager at the end of the month when he returned to Zion for supplies. He wrote in his diary that night, "Both fine men and believe we will get along just fine." [1214] It would soon be made clear to Heaton that the new superintendent and his assistant intended to run a very tight ship.

During June and July 1943, Heaton hauled rock (probably from Bullrush Wash) and laid a rock floor in "Garage No. 2." The following year, he returned from Zion with an old gasoline-powered Delco light plant, which he set up in the garage. As the old monument truck seemed to be in constant need of repair, Heaton needed this lighted workspace. When he was unable to find and fix the problem, he took the truck to Zion mechanics; if it wasn't driveable, the park mechanic came to the monument. During the summer, the monument's custodian and regional office officials reviewed plans for the monument's public contact and comfort station. [1215] The building was to serve as the public contact station and custodian's office, and to provide public restrooms. Officials had long wanted to end any use of the fort, whether for living or office space, so that it could be converted into a house museum. The need for a modern comfort station was equally important, as old pit toilets were still in use at the monument. While the regional office approved the plans, concerns were expressed that the proposed building lacked room for exhibit space. [1216] The reason this building was never built, however, is the same reason the custodian's residence was not constructed: lack of funding.

In early 1944 Heaton lamented in his journal, "My hardest task on the monument [is] to tell where letters should be filed." [1217] That March Zion's Chief Clerk Carl Walker and an assistant spent a day inspecting Heaton's official files. The filing system must have left something to be desired by Park Service standards, for all of the monument's files were taken back to Zion to be organized. When Heaton picked them up from Zion a month later, he reported that the files were "...all arranged as they ought to be. Now if I can keep them up to date and in order." [1218] Office work was never a job the custodian enjoyed doing.

During the spring of 1944, Heaton laid 180 feet of two-inch irrigation pipeline from a point 200 feet east of the ponds to the north side of the campground. This was done to reduce water loss from the campground's open irrigation ditches. In July 1944 Heaton received a visit from Assistant Superintendent Yeager and Chief Ranger Fred C. Fagergren. The men brought along fire fighting equipment for the monument. Fagergren conducted the first official fire inspection ever made at the monument, Heaton later wrote. Fagergren identified several fire hazards, which Heaton worked to address soon after the men's departure. During the summer of 1944, an attempt was made to develop a combined departmental fire crew to be made up of men from the Grazing Service, Indian Service, and Park Service. [1219] As a precautionary measure, Heaton taught some of his family members how to use the fire fighting equipment on grass fires. "[I] want to hold several more classes 'til all know how to use [the equipment] and what to do in case of fire." [1220]

Heaton always left family members in charge of the monument when he traveled to Zion or during short periods of leave from the monument. He took longer stints to work on the family farm in Alton, Utah. [1221] On those occasions, he was home in the evenings, but during the day his wife and older children tended to the needs of monument visitors. Heaton reported being in Alton from August 15-25, 1945, doing farm work. "During this time some members of the family were here at the monument and they seemed to carry on about as well looking out for the monument interests as if I were here," he reported to headquarters. [1222] Like earlier Southwestern Monuments officials, Zion officials apparently had no problem with this arrangement, partly because visitation was so low during the war years and partly because it saved Zion the trouble and expense of finding a replacement for Heaton. Of course, neither Edna nor the children were ever paid for rendering such services. Edna Heaton had been "filling in" on a regular basis for Leonard since his appointment in 1926. As their children grew up on the monument, they too were recruited for monument work, according to their age and abilities. [1223]

The war in Europe formally ended on May 8, 1945, while Japanese surrender terms were signed on September 9, 1945. Between those two events, in July 1945, Heaton began to write a detailed history of the monument "as I have it in my head.... I thought I should get what I can remember on paper. Should I leave the place, there will be a record for the next fellow." [1224] This work went very slowly, usually only a page or two at a sitting. Heaton was still working on the project over a year later. [1225]

Wartime Visitation

Fort visitation for fiscal year (FY) 1942 was the lowest ever in the monument's history - only 372 people - compared with 1,259 visitors the previous fiscal year. After gas rationing went into effect during the fall of 1942, visitation to Pipe Spring National Monument continued to drop. Only eight visitors came in October and only four in November 1942. [1226] In December travel figures were boosted to 20 by a visit of 12 men of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers sent to the area to begin removal of the two CCC camps at Fredonia and in Antelope Valley, Camp G-173. (Demolition of the Short Creek camp did not begin until May 1943.) These pitifully low figures would never be revealed by the director's annual report to the Secretary of the Interior for FY 1943, for on October 1, 1942, park units were instructed by Director Drury to begin a new system of counting visitors. [1227] Whereas up to this time Heaton had based visitation figures on those who came to what he called the "fort museum," under the new system he was to count all travelers using the monument road during daylight hours, whether or not they stopped.

The consequence of adopting this new system was that the travel figures for Pipe Spring for FY 1943 were so inflated that they are virtually meaningless. Heaton reported in March 1943 that about 97 percent of the cars that passed through the monument were local people going to and from their ranches or to nearby towns, yet these would have been counted in annual travel totals. [1228] A crew of 15 soldiers involved in the removal of Camp G-173 passed through the monument every day to go back and forth to work, thus Heaton was required to report travel of 338 soldiers to the monument that month. At the end of FY 1943, "official" travel for the monument was 6,310, compared to 372 for 1942. In August 1943 Heaton was directed by Zion officials to return to the old method of counting for FY 1944. [1229] Pipe Spring received 515 visitors that year. The last war year (FY 1945) visitation to the monument was 635. [1230]

Gas rationing was lifted during the summer of 1945. Heaton was dismayed to report the following: "There has not been any noticeable increase in the travel here since the rationing of gas was lifted. The majority of the travel has been parties in the campground or to swim in the meadow pond.... a total of 54 people at the monument for the month of August." [1231] Heaton was encouraged the following month when he received 152 visitors. Visitation for FY 1946 increased to 1,193.

Weathering the Infirmary and Other Cold Places

The Heatons experienced first hand the drawbacks of inhabiting a CCC building over the winter of 1941-1942. Heaton reported to headquarters "that it is so hard to heat and keep warm during windy days. The wind comes in one side of the building and the heat all goes out the other, even though the stoves consume 100 to 150 pounds of coal and wood daily. (Thanks to the old CCC coal pile, by screening, we get enough to keep warm in the living room and kitchen.)" [1232] The many cracks in the board-and-batten frame building - never designed nor constructed to be a permanent structure - let in as much cold as they let out heat. Fortunately for the Heatons, the closure of nearby camps resulted in the family having an additional supply of coal. In February 1943 Heaton built a coal bin to store coal picked up from the abandoned Fredonia camp. He placed the bin on the south side of the willow patch in an "old concrete and rock washing spot, built by the ECW when the camp was here..." [1233] In September 1944 he picked up an additional five to seven tons of good stoker and large coal from one of the camps - enough, he estimated, to last about a year. By the fall of 1945, he ran out of salvage coal and had to start making trips to the coal mine in Alton several times a month to buy coal.

The coal not only heated the residence but also took some of the chill off of Heaton's drafty office in the fort. Working in his office a few days before Christmas 1943, he reported "...trying to keep warm with the little 2 x 4 heater. Have to stuff wood and coal into it about every 15 or 20 minutes to keep the room warm enough to keep from getting cold. Feet always cold. Floor is rock and a bit damp most of the time." [1234] Poor Heaton had nowhere to get warm. Even the old monument truck had no heater in it, making winter trips to Zion an unpleasant affair. In January 1944 Heaton went to Zion for supplies in the pickup, writing later that the long trip was "one of the coldest rides I have had since about 1924 or '25." [1235] In December 1945 Heaton worked in the office filing papers and studying reports. He wrote, "Very hard to keep the place warm. Have to get up every five or ten minutes to stuff the stove with fuel to keep the chill out of the room. Still one's feet are always cold." [1236]

The warmth of springtime was thus always welcome at the monument. By the spring of 1942, however, the Heatons could no longer stand the bare look of the old CCC infirmary's landscape. In early April Heaton transplanted lawn grass from Moccasin to the front of the family's quarters. The following spring he planted trees around the residence to create a windbreak. That fall, with no hope of a new residence being built, Heaton wrote, "...since it looks like it will be several years before a new residence building will get put up, I am going to improve the grounds around the residence building we live in now, plant lawns, trees, and shrubbery." [1237] The grass earlier transplanted from Moccasin apparently didn't transplant well, for in November, Heaton wrote in his journal, "Want to plant some lawn early next spring to make the place look like a home rather than a shack. [For] 18 years I and the wife have been at the monument without decent outside grounds and I am going to change this condition if possible." [1238] For a Mormon couple used to the well-irrigated surroundings of Moccasin, the natural desert vegetation of the monument (or at least what little of it remained) must have appeared terribly unattractive.

In May 1944 Heaton was informed that Zion had received a $50 allotment for repairs to his quarters. In June 1944 Heaton went to Bullrush Wash for a load of flagstone rock to lay a path to his residence. In mid-month he excavated a new cesspool north of his quarters. He then filled in the old cesspool northeast of the residence and leveled ground in preparation for planting a lawn over it. During the war years, a number of cesspools associated with Camp DG-44 had caved in. Heaton filled these in with dirt.

Flood Problems

Floods continued to be a problem in the area, as they had been for many years. On August 9, 1942, the second most destructive flood in two years occurred in Moccasin. Crops and fields were covered with two feet of sand and water during the 40-minute storm. No significant damage was incurred at the monument. It was only a matter of time, however. In February 1943 Heaton cleaned out the diversion ditch north of the culverts while observing, "A lot of work needs doing at the upper end of the wash to keep the floodwater from running over and down through the parking area and campgrounds." [1239] That month he and his sons hauled seven truckloads of sand from the diversion ditch into the wash to cover up trash and debris.

On August 29, 1943, a flash flood in Two Mile Wash resulted in flooding on the monument, which damaged roads, the campground area, and fencing. [1240] Floodwater even flowed into the cellar, garage, and over the Heatons' "victory garden." Floods also caused damage in Moccasin and along area roads. "This was the worst flood at the monument for some 10 or 12 years. I think it will take me 4 to 6 weeks to get everything back into shape and fixed up," wrote Heaton. [1241] The following day he made a detailed report of flood damages and listed the work required to make repairs, estimating between two and three months of labor. On August 31 Smith and Yeager visited the monument to inspect flood damages. After spending several months cleaning up the mess, Heaton borrowed a tractor and scraper from Grant Heaton to level and fill in around the residence to divert floodwater around from it and away from the cellar.

Near the end of 1944, Heaton contacted Reservation Agent Parven Church and asked if he could create a diversion for flood water at the northeast corner of the monument so that in case of heavy rains the water would run to the east of the monument instead of through it. Then, in late January 1945, Heaton modified the wash as proposed to Church, using a tractor to create the new channel. "Will help considerably in keeping the flood wash through the monument free of sand," he wrote. [1242] A few days later Heaton turned another drainage wash just north of the monument.

Museum Collection

Zion National Park officials dispensed more than advice to Pipe Spring National Monument the first year it oversaw the site. By December 1942 the park had loaned Pipe Spring a large collection of pioneer-era antiques from their collection. Custodian Heaton spent much of the winter cleaning and repairing artifacts, and trying to decide how and where to best display them in the fort. Heaton wrote in his journal that winter, "Worked in the fort most all day... taking care of relics, fixing them up. Having a tough problem deciding just what to do with all the pieces of museum articles. Need some display cases, shelves, and tables. Am starting on plans I would like seen put through to exhibit these articles." [1243]

During December 1942 Heaton was given an Indian skull found in a dry wash bed some 10 miles southwest of the monument by L. J. ("Ren") Brown and Grant Heaton. Just the top part of the misshapen skull was intact. Heaton speculated that its original owner had been hit a hard jolt in the left temple, probably causing death. [1244] This may have been the skull that several Kaibab Paiute women elders reported in recent interviews having seen (and being frightened by) in the fort as young children. [1245]

In September 1943 Zion staff made an official inventory of monument property. Heaton later wrote in his journal that this was the first property inspection the monument had ever had in all the years he had been there. Yeager also did some rearranging of museum articles and made recommendations to Heaton on how to improve the exhibits. [1246] Zion staff also spent time this year assisting Heaton in rearranging the filing system and in advising him on clerical procedures.

In early May 1945, Heaton obtained the donation of an important collection of pioneer artifacts from Glendale, Utah. [1247] These once belonged to Bishop John Hopkins, carpenter and blacksmith at Pipe Spring during the fort's original construction. Heaton had obtained part of this collection from Alvin Black in late 1941. He picked up additional artifacts on May 3, including many more tools. The following October, Heaton received a request from Mr. Black's daughter, Mrs. D. A. Smith of Glendale, that he return her father's carpenter and blacksmith tools. Heaton consulted with James Esplin in Glendale and was told that since the deal had been closed for some time, that Heaton was under no obligation to return them to Smith. The artifacts remained in the monument's collection.

Significant progress was made during the war years toward researching the monument's history and developing a furnishings plan for the fort (see "Interpretation" section).

The Ponds and Fish Culture

In April 1942 Heaton reported cleaning the fort ponds, an arduous job that took one man 8-10 days. He described the process: "shoveling [muck] into a wheelbarrow, wheeling it out up a runway and dumping [it] into the truck.... hauling the muck off and then scraping it out of the truck..." [1248] The ponds were then refilled by the monument's main spring. Heaton wrote that it "took about 50 hours to fill the 2 ponds" with water. It had taken 60 hours in 1933, he recalled. [1249] Heaton attributed the difference to the "new spring uncovered in 1941" at the fort's northeast corner. The custodian calculated this was the fourth time the ponds had been cleaned out since the monument's establishment. The first times were in 1926 and in 1930 (both times with the help of a horse team instead of a truck), and the third time was in 1937 (with the help of CCC labor). [1250] By the time Heaton was finished with the 1942 cleaning, only 10 trout remained in the west pond; several hundred carp were in the east pond, most from 1.5 to 5 inches long. The two largest carp (more than 16 years old) weighed 15 and 17 pounds, Heaton reported. He put those in the meadow pond.

In August 1943 Heaton took four of his sons to pick up trout at the Utah State Fish Hatchery in Panguitch. He got 1,900 rainbow trout, about 3.5 inches long, and planted them in the two fort ponds. [1251] Prior to putting them in the ponds, he screened the pond outlets so the trout could not get out through them. In the spring of 1944, Heaton tried an experiment to reduce the usual fish loss associated with cleanings. He cleaned out the ponds in sections, reporting, "I am only doing part at a time as once I killed all the trout in one pond by cleaning it all out in one day." [1252] During the summer of 1944, Heaton reported, "Caught 2 little Indian boys fishing in the ponds by the fort this evening." [1253] (Apparently, Heaton only allowed this privilege to Park Service officials, like Harry Langley.) In May 1945 the custodian reported a number of fish died of unknown causes. "I am of the opinion that another planting of a 1,000 or 1,300 could be made this year," he later wrote, but there are no reports of the ponds being restocked with trout again until 1963. [1254]

Leaving Their Mark

In May 1944 Heaton reported, "The other day my boys found some initials on some rocks... also pictures of trees, and one horse head, [and] other paint writings. Am not sure as to just what it is. Will make a more thorough study later. More Indian picture graphs were also found on ledges west of monument. These were of human figures as well as snakes and bear tracks." [1255] The first group Heaton refers to were located about one-quarter mile northwest of the monument "in a heart-shaped canyon." [1256] The "picture graphs" reported west of the monument were located approximately 300-400 yards west of the boundary. From time to time, Heaton would take small groups to see the Powell survey marker monument, which was on reservation land. [1257] Now, with the "discovery" of the Indian petroglyphs, he added a walk to Heart Canyon (also on the reservation) to take visitors to see the drawings as well.

The following year Heaton learned that this ancient Indian art form was being kept alive (albeit in a more popularized form) by Kaibab Paiute children. On May 16, 1945, the fort gates were defaced by a group of them. [1258] "Made a copy of names and initials left by Indian children on the fort." The names belonged to F. Jake, Bill Tom, Elouise Drye, E. Sampson, K. Mcartes, Charlie Chassis, and Warren Mayo." [1259] The east big gates had names, initials, dates, and drawings (such as a heart), scratched on with either plaster, sticks, and/or rocks, thought Heaton. The office door on the south of the building had pencilled graffiti on it. The lower half of east gate and office door were "pretty well covered," wrote Heaton. Some time later he spoke to Parven Church about the Indian children leaving their names on the fort. Church told him he would try to have the children come down and remove their names.

The Stockmen's Two-acre "Reserve"

In 1943 Zion officials requested details from Heaton about the acreage and cost of land acquired for the monument, and asked for tax information. [1260] Yeager asked Heaton to provide the information, and in doing so, Heaton revealed quite a surprise:

The acreage of Pipe Spring National Monument under the original transfer to the National Park Service was 38 acres and the cost of the land, water and buildings subscribed to by private persons and concerns was $5,000.... Two acres of land in the southwest corner of the monument, or the 40 acres, to be used as a place to handle cattle and the big corrals on the east side of the area. These corrals were moved on the east half of the two acres reserved by the stockmen in 1935, and have been in use since that date. I am not familiar with the status of the two acres at the present time tho' I have heard some of the stockmen say they still own them. [1261]

This was certainly news to the Park Service, for the monument comprised 40 acres, not 38! In February 1945 Heaton wrote in his journal that he tried to get information from his father on the lease of two acres of the southwest corner of the monument to cattlemen. He copied letters and sent them to Zion as per their request, but no copies of that correspondence have been located. The answer to the mystery of these two acres would be revealed 26 years later, in 1969. (See "General Historical Research and Publications" section, Part X.)

Area Roads

Indian Service work on a section of the road from Fredonia continued in early 1942. The Indian Service began construction of a new road from a point 100 yards east of the monument to a point about six miles east toward Fredonia. Its alignment did not follow the Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) survey made in 1937 and some of the grades appeared overly steep to Heaton. The work was to be completed in two months. Heaton alerted Southwestern Monuments, sending a sketch map of the road's location. That office in turn alerted Superintendent Franke at Zion. Landscape Architect Al Kuehl opined the proposed location was in the general location of the BPR survey and had no objection to it. (It is presumed the work was completed.)

The Indian Service had no interest either in building or maintaining any road west of the cutoff to Kaibab Village. The dirt road toward Kaibab Village was not improved to the level of the road from Fredonia (it was not graveled) but was sporadically maintained by the Indian Service. Very little if any work was done on the road from Pipe Spring westward during the war years, and this was by far the worst section of the Hurricane-Fredonia route, as it had been prior to 1941. Heaton reported that in July 1943 the road from Pipe Spring to the Utah state line was in very poor and dangerous condition. Beyond the state line in Utah the road conditions improved. [1262] Washington County officials maintained that section of road to Zion. Apparently little attention had been paid to the section, either the portion which lay within and was maintained by the reservation or the larger stretch of road to the Utah state line which was the responsibility of Mohave County road crews to maintain.

In May 1943 the regional office in Santa Fe submitted two road-related project proposals in the monument's project construction program. One was to relocate the monument road (State Highway 40) to a location outside the monument boundary; the other was to construct a road from the relocated road to the monument's east boundary. It was noted in the proposals that there was no authorization for the expenditure of funds on lands administered by the Office of Indian Affairs, unless the roads were officially designated as approach roads. The two proposed routes were subsequently not recommended for designation as approach roads, so the proposals were eliminated from the program. Then in July the regional office proposed to combine both proposals into one as the "West Approach Road," hoping that this move would facilitate getting it designated as an approach road. [1263]

The relocation of the monument road was too important an issue to let drop, particularly at a time when development plans for the monument were being finalized. How could Superintendent Smith's vision of a "living ranch" be realized with a highway cutting a swathe through the tiny monument? How could any of the fort's historic setting be recreated with the highway passing right in front of it? Assistant Director Tolson wrote to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1943 that such traffic conditions were "very disturbing to visitors." [1264] Tolson informed the commissioner of the Park Service's plans to relocate the road outside the monument on reservation lands. If the plan met the approval of the Office of Indian Affairs, Tolson said the Park Service would request its designation as an approach road for construction after the war. In response, the Office of Indian Affairs asked for a detailed map showing the proposed location of the road tied in with legal subdivisions (Tolson had sent only a rough sketch map). Upon receipt of the map, they intended to take the matter up with the superintendent of the Kaibab Indian Reservation. Tolson sent back the same map he had sent earlier with only township and range data and section lines imposed on it. "We are not in a position at this time to have more detailed engineering data obtained in the field," he wrote, adding that this work could be done only after the route was designated as an approach road. [1265] It appears that no further action was taken on the relocation of the road during the war years.

In April 1945 Heaton reported improvements in approach road maintenance. That month the Indian Service worked on the road east of Pipe Spring, and Mohave County crews worked west to Short Creek. The whole of the approach road was finally in good condition, Heaton reported. [1266] But good roads could change to impassable roads in a matter of days in the region. Frequent maintenance was required, given the low standard of the area's roads to begin with. By October 1945 Heaton reported rainstorms had made the roads very rough. Neither the Indian Service nor Mohave or Washington counties had done anything to improve them, he advised Zion officials.

The maintenance of roads on the monument itself was an ongoing activity, with the primary road requiring frequent regrading and graveling. The gravel pit was located 6.5 miles east of the monument and gravel was purchased from the reservation. [1267] A typical application on the monument road took about 20 truckloads of gravel. It was hard work but - as was so often the case - Heaton drew on the familial labor pool. On October 20, 1943, he wrote, "...got two loads of gravel and graded the roads using my 13-year-old boy as truck driver while I ran the grader." [1268] In addition to gravel, Heaton sometimes used coal screenings to surface the monument road. Heaton screened out the larger pieces to burn in the residence and fort office then spread the residual coal dust on the road.

Water Issues

Water issues once again emerged during the war years to challenge Park Service officials and lawyers. In early March 1942, Indian Service representatives Alma Pratt and Parven Church visited the monument to investigate the water situation. The men objected to a pipeline that carried water to the campground, hydrants, water trough, and residence directly from the springs without passing through the division weir. It was later determined by Franke why this was so. Apparently, while the CCC camp was at the monument, culinary water requirements had dictated that the Army take the water directly from the spring to eliminate the possibility of contamination. The Army had thus installed their own connection prior to the water entering the fort ponds. Some time after Camp DG-44 left Pipe Spring, Heaton connected up his main supply line to this same place. Heaton most likely did this for the same reasons as the Army, to have a clean source of water, thereby reducing the threat of typhoid in the family. It is unknown if this was authorized or sanctioned by Park Service officials. It certainly saved the Park Service from having to provide a chlorinating system for the Heatons' culinary water.

Heaton's arrangement meant that only the monument's open ditch irrigation system was being provided from pond water that passed through the division weir installed in 1934. Heaton was diverting all other water being used for Park Service needs prior to the division weir. [1269] If Heaton was aware this was a breach of the 1933 agreement, there is no indication of it in the records he left behind. The Indian Service's later discovery of this practice, however, reinforced their long-standing view that the extended Heaton family wasn't to be trusted when it came to water issues. [1270] It is hardly surprising then that the Indian Service officials were upset. The Indian Service had no intention of letting Heaton's modified system of water distribution and use of water at the monument go unchallenged. [1271]

As serious as the situation was, this was not the only concern the Indian Service had at the time, however. The Park Service and Indian Service agreement in October 1940 to construct a road through the southern part of the monument and the adjoining portion of the reservation (discussed in Part V) would impact the Tribe's pipeline from Pipe Spring, as well as the associated reservoir and gardens. As these were located at the monument's southeast corner, the road relocation would have required abandonment of that area. Indian Service officials were looking at the possibility of piping the Indians' share of Pipe Spring water through the stockmen's pipeline which, after all, the Tribe had paid for and installed. If this was done, they would then move their gardens to the location a mile south of the monument boundary where the stockmen's water had been piped since the summer of 1934. [1272] It is unknown whether or not the Indian Service also contemplated a change in their eight-year-old arrangement with the stockmen. Fortunately, since neither money nor labor were available during the war years to construct the road, the arrangement southeast of the monument remained the same for many more years.

In mid-March 1942, the Indian Service's Superintendent C. C. Wright (administrator over Indians in southern Utah) traveled to the reservation to continue the discussions begun by Pratt and Church. Wright asked Heaton what correspondence he had in his files on the subject of the water division. Heaton later wrote in his journal, "I am afraid they are going to attempt a change in the setup here at the Monument that the Park Service will oppose pretty strongly." [1273] Heaton began to read through all the old correspondence he had on the water issue. In late March, during an inspection visit to the monument, Franke directed Heaton to avoid bringing up the water question with Indian Service representatives (to "not open up old wounds") until more information on what they wanted was known. [1274] In early April Franke requested any data that Southwestern Monuments had on water issues; the "Water Problems" file was immediately sent to him.

A ruling during the summer of 1942 by Acting Solicitor W. H. Flanery led to the reopening of discussions concerning Pipe Spring water rights among Park Service officials. In February 1943 Hydraulic Engineer A. van V. Dunn wrote Attorney Albert L. Johnson (both Park Service, Water Rights Section, San Francisco) a memorandum that not only describes important aspects of the problem not previously referenced in other reviewed documents, but also provides an excellent summary of events surrounding the monument's water issue up to 1943. For these reasons, Dunn's memorandum is quoted in its entirety below.

This is to suggest that the water rights at Pipe Spring National Monument may need reconsideration.

We prepared to make a formal appropriation of these springs during 1937. By letter of March 12 of that year the Assistant Commissioner of Indian Affairs objected, or at least refused to concur in the Director's plan to authorize us to file a claim in Arizona.

The Indian Service was then in court to define its water rights in the Walker River Reservation, although the Commissioner did not so state, and the Park Service filing to include use for the Indians at Pipe Spring might have had disastrous effects. Since then, the Walker River case has been settled to the satisfaction of the Indian Service. However, I am not sure that the Walker River case gave the Indian Service any claim to rights at Pipe Spring, and I am quite certain that it did not provide any protection of the claims of the United States or the local stockmen.

On April 17, 1916, the area within one-fourth mile of the springs was proclaimed Public Water Reserve No. 34. The whole township was withdrawn on July 17, 1917, for the Kaibab Indians, and an adjusted interpretation of the water reserve was made by the Secretary on May 31, 1922. On March 3, 1920, Charles C. Heaton and the Pipe Spring [Land and] Live Stock Company filed application to locate Valentine scrip on the SE? SE? Sec. 17, which is the monument, and nominally also the water reserve since the springs are near the center thereof. This was rejected as being in conflict with the withdrawals, but a letter from the director to President [Heber J.] Grant of the Mormon Church, of Oct. 29, 1924, advises that the Secretary had just accepted a quitclaim deed from Mr. Heaton to cover the area. The area was proclaimed a national monument in 1923. By 1933 the local stockmen and Park Service were so dissatisfied with the meager amount of water they obtained after the Indian Service made its diversions that it became necessary for the Assistant Secretary to issue regulations to divide the water equally three ways. By decision approved June 15, 1942, Acting Solicitor W. H. Flanery ruled that water reserves were void when superseded by national parks or monuments. [1275]

All of this suggests that if past correspondence and proclamations are intended to show Park Service water rights protected, the protection was supposed to be under the water reserve. However, the ruling of June 15, 1942, seems to nullify the basis for earlier contentions.

The present Arizona water code took effect in 1919. Any use initiated by individuals before that date are vested. On this basis, the stockmen and Indian Service might have vested rights, but the Park Service does not unless by the quitclaim deed to the United States from Charles C. Heaton in 1924.

In past correspondence the point has been brought up that no appropriation might be needed if the natural stream flow did not leave the Park Service area. This seems to need interpretation. A spring does not have to be formally appropriated in Arizona if its flow does not leave the claimant's land. On this basis, it would not have to be appropriated even if it left the monument area if it did not further leave the Indian and other adjacent federal land.

If you look at this Arizona statute from the practical side it says you do not have to file on a spring to which others do not have access because those others cannot introduce conflicts without your consent by providing access. At Pipe Springs the private access has been provided by a pipeline, a tri-party agreement and regulations by the Assistant Secretary. The stockmen may have a perfected vested right now, and if not, there seems to be nothing to prevent them from perfecting one by filing and proof unless there are implied bans in the agreement and regulations. Since the regulations seem to be based on the existence of a water reserve, they may not have any standing at this time. In that case, the agreement is a division of the property of a fourth party, the State of Arizona.

I feel that we should file on one, two, or three thirds of the flow to get title from the State for ourselves, and for the stockmen and Indians if necessary. If we file on all, we can state in the claim that the United States does not waive any rights which may accrue from past reserves or vested rights. We can also specify that the filing is merely to strengthen the tri-party agreement. [1276]

At Dunn's request, Johnson transmitted the above memorandum to the regional office on March 4, 1943. Dunn was planning to be in Santa Fe on March 9 and wanted officials there to have time to think over the matter before his arrival. Johnson wrote to Regional Director Tillotson that the decision to abandon the Park Service's plan to file on the springs in 1937 had been explained by Associate Director Arthur B. Demaray in a letter of May 21, 1937. Johnson wrote,

Now Mr. Dunn sees a chance for revival on the theory of the opinion of Acting Solicitor Flanery of June 15, 1942, acknowledging the superiority of monument reservations to that of water reserves. [In] Mr. Dunn's memorandum you will note that he says 'the stockmen and Indian Service might have vested rights, but the Park Service does not...' I rather agree with Mr. Demaray in the last page of this memorandum of May 21, 1937, in stating his doubt whether the stockmen could acquire water rights and whether there was any vesting of water rights prior to the enactment of the [Arizona water] code. [1277] I feel that whatever rights are acquired by the Indian Service are acquired for the benefit of the United States, the same as when the Park Service makes an appropriation. [1278]

Johnson was willing to proceed with filing if Tillotson or the Park Service chief counsel thought doing so would offer better protection of the Park Service's rights. The regional office sent Dunn's letter to Franke at Zion, advising Johnson they would not take further action without his comments. In addition, Dunn personally discussed the matter with Franke in Salt Lake City. [1279] Franke then wrote the regional office on March 20, 1943, requesting that the Water Rights Section prepare and submit to him "a complete and clear >outline of the problem and its suggested solution." [1280] Franke intended then to take the matter up with local Indian Service officials to see if an agreement could be reached. "If Field agreements are reached by these Interior Department representatives, later difficulties may be avoided," Franke wrote. [1281] While on the surface this may have appeared to be a reasonable managerial approach to the problem, Franke's suggestion revealed his utter lack of familiarity with the complexity of water issues at Pipe Spring and the long-standing enmity between the Indian Service, the stockmen, the Heatons of Moccasin, and the national monument.

In response to Franke's request, A. van V. Dunn prepared a nine-page report that he submitted to Attorney Johnson in April 1943. Dunn's report, which he described as an "analysis of conditions," drew heavily on the 1933 Robert H. Rose report ("Report on Water Resources and Administrative Problems at the Pipe Spring National Monument") for information. [1282] As previous decisions concerning Pipe Spring water had been made at the highest levels in Washington, D.C., Dunn strongly advised against Franke saying anything to local Indian Service officials or to the stockmen about the possibility of the Park Service filing on Pipe Spring water. A summary of Dunn's analysis follows, accompanied by pertinent excerpts. [1283]

It seemed to Dunn that water had been used "fairly continuously" on the monument area since about 1863 while Arizona was still a territory. Any water rights established between 1863 and February 14, 1912 (when Arizona became a state), were in accordance with the territorial water code. Dunn wasn't certain, but thought this code "probably recognized rights based on physical diversion and use without requirements for filing." [1284] A system of county filings had been used in Arizona between 1912 and 1919. "So far as I know, no one had investigated the county records," wrote Dunn, recommending that this be done. [1285] It was unclear to Dunn that Pipe Spring was included in the October 16, 1907, withdrawal of the township for use by the Kaibab Paiute. [1286]

If the monument was part of the Indian Reservation the case of Winters et al vs. United States (207 U.S. 564) could easily apply.... It is particularly interesting to note that the Fort Belknap Reservation... was established while Montana was a territory just as the Kaibab Reservation was established while Arizona was in the same status.

If we acknowledge that the Indians acquired a right to waters on their reservation we do not know yet whether the monument was part of this initial reservation or whether the Indians actually used water from Pipe Springs at that time...

...all land within one quarter mile of Pipe Springs was withdrawn as Public Water Reserve No. 34 on April 17, 1916 and [readjusted] on May 31, 1922. This was after Arizona became a State but before it adopted its present water code.

If we accept the Solicitor's opinion of June 15, 1942, to the effect that establishment of national monuments cancels water reserves we can also probably assume that no water reserve would have been necessary in 1916 if the area was already on Indian Reservation — unless the water reserve was established to limit Indian use in the interest of the white public. At all events, using the Solicitor's opinion of June 15, 1942, would not the withdrawal of 1916 cancel any portion of the Indian Reservation within one-quarter mile of Pipe Springs? [1287]

In Dunn's view, the July 17, 1917, withdrawal seemed to cancel out the water reserve, yet the water reserve had been adjusted on May 31, 1922, to cover the area of Pipe Spring (soon to become Pipe Spring National Monument). The fact that the Secretary of the Interior had made the adjustment, however, might be meaningless as it took an executive order of the president of the United States to establish a water reserve. The application filed by Charles C. Heaton and the Pipe Springs Land & Live Stock Company was rejected on April 15, 1920, stated Dunn, "as conflicting with the water withdrawal. Note that this was between the creation of the Indian Reservation in 1917 and the interpretation of the water withdrawal of 1922." [1288] The area of Pipe Spring National Monument comprised the east half of the amended water withdrawal of 1922. Its establishment on May 31, 1923, seemed - in Dunn's view - to nullify "any water withdrawal or Indian Reservation covering the same area." [1289]

A few important pieces of information are missing from Dunn's account of the history to this point. Charles C. Heaton had appealed the rejection of his application and was denied again on June 6, 1921. As mentioned in Part II of this report, the second rejection came on the same date that Director Stephen T. Mather wrote Office of Indian Affairs Commissioner Charles H. Burke about his interest in making the site a national monument. Then Heaton filed a motion for a rehearing of his land case. It was during this waiting period that the monument was established. (None of the preceding information was in Dunn's report.) When Heaton executed the quitclaim deed to the Pipe Spring property on April 28, 1924, he withdrew his application. "Regardless of past claims," Dunn maintained, the United States government seemed to have clear title to the monument area under the supervision of the Park Service. He continued: "....any water rights existing when the present water code was adopted in 1919 were probably manifest only in use under territorial code. I wonder if the Arizona code of 1919 was subject to vested rights. I think the matter needs further investigation." [1290]

It was Dunn's opinion that the tri-party agreement made on June 24, 1924, for the equal division of water between the stockmen, Indian Service, and Park Service was confirmed on November 2, 1933, by the Assistant Secretary Oscar Chapman's signing of the "Regulations for the Division of the Waters of Pipe Spring." [1291] Dunn was concerned about the fact that Heaton was allowing some local people access to water at Pipe Spring who were not among the stockmen who signed the 1924 agreement. "There seems to be a potential danger of private appropriation if any of the local people have access to the water," he warned. [1292] A right might be established even if only intermittent access was open to local people.

In addition, the question of whether or not the spring flow ever left the monument or the reservation was a critical one. Water had been impounded and used at Pipe Spring for so long, Dunn noted, that "No one can now state how far the water would flow under natural conditions, but it is quite possible that it would reach Section 32 at times. If so, the ponds and other local use can be protested unless they are covered by a territorial right or by prescription. I think both may exist." [1293] Also, because the stockmen had been piping water off the reservation since 1934, Dunn thought that, under the 1939 water code, the stockmen might perfect a water right to cover their beneficial use, citing two sections of the code to make his case. [1294]

Under the 1939 water code, Dunn argued that a person might perfect a water right on the public domain superior to those perfected by a later entry-man, that he might evoke the right of eminent domain (except against the United States) to perfect a right, and the only way to lose it was by five years of non-use. "I wonder if we cannot also state that any use continuing since prior to 1907, 1916, or 1917, is vested and superior to Indian or water reserve claims," he added. If all this was true, cautioned Dunn, then the United States needed to either perfect or protect all its potential rights to the springs. Toward this end, Dunn prepared estimates of water demand by each of the three parties - Park Service, Indian Service, and stockmen. He based his estimates on the output of both tunnel spring and the main spring (what Robert H. Rose identified as two springs, "big spring" and "main spring," but which were in fact one). His calculations showed slight deficits for the Park Service and stockmen, and a considerable surplus for the Indian Service. [1295] According to Dunn's estimates, the Indians had a surplus that exceeded their demands by 25 percent. "Clearly, the Indian Reservation has not made use of more than 65 percent of its one-third of the spring flow since the pipe was installed, unless it hauled water or brought its stock onto the monument," wrote Dunn. [1296] His documentation indicated that Pipe Spring water supplied was then supplying the needs of three Indian families, 100 head of Indian-owned livestock, and a 3.11-acre irrigated garden. The stockmen's demands comprised 13 families and 1,582 head of livestock. The monument's demands included water for the custodian's family, tourists (based on an average year of 3,000), maintenance crew and rangers, 10 families west of the monument, livestock, and the irrigation of 4.39 acres of monument land. [1297]

Dunn raised four questions whose answers would bear on the water issue: 1) Do the Indians have the valid right to more water than they now use when they care to divert it? 2) Is the Indian population likely to increase to justify more demand? 3) Would their potential increase in living standards and occupation require more or less water? and 4) Since the Office of Indian Affairs built the pipeline for the stockmen, does the pipeline establish a right-of-way across the monument and reservation land for perpetual access by the stockmen? Dunn argued that if the Park Service could use the Indians' (and possibly the stockmen's) "surplus" water (by his calculations), then additional monument acreage could be irrigated. Instead of the 4.39 acres then being irrigated, somewhere between 6.25 and 8 acres could be watered, he estimated. [1298] The "surplus," as Dunn interpreted water law, was unappropriated and therefore subject to appropriation. [1299]

Dunn recommended that someone research what the water codes were prior to 1919 and the status of the codes after the Arizona water code of 1919 went into effect. "We should also find out how the quantity of water in these early rights is now determined." [1300] Dunn doubted that the full spring flow was used prior to 1919 on the monument area and Indian Reservation. [1301] If this was the case, then some may have been unappropriated and thus would be subject to appropriation "at the present time." While there was no reason the stockmen couldn't file their own application for water rights, stated Dunn, "this might result in complicated joint interest in pipeline and right-of-way across the federal land. It would seem better for the United States to perfect such rights as are necessary, including those to deliver such water to Section 32 as may be required by present or future agreements." [1302]

Dunn could see no reason why the Indian Service and Park Service couldn't arrange proper agreements for full use of the water not needed by the stockmen "and keep State claims as a unit." The tri-party agreement of 1924 had "much the status of a decree," wrote Dunn. However, he wrote,

The meeting at which it was signed was an informal adjudication. We might be able to have it recognized by the State without the use of normal application, permit and license, but it is weak for such recording because it does not show that all potential claimants are parties, and it might fix allocations to the three parties enough to complicate future amendments. [1303]

Dunn had been the author of the application drafted in 1937 then set aside by the director. Having noted the Office of Indian Affairs' objections made at the time, he offered several new paragraphs that he felt would address their concerns. He recommended that any final draft of the application should be worked out between Indian Service and Park Service engineers with more complete data.