|

Pipe Spring

Cultures at a Crossroads An Administrative History of Pipe Spring National Monument |

|

PART VII:

THE CALM BEFORE THE COLD WAR

Introduction

The relative quiet that Pipe Spring National Monument experienced during World War II continued for the remainder of the decade. This chapter focuses on the events that took place at the monument from January 1946 to January 1951, when the United States government began aboveground testing of atomic weapons in Arizona's neighboring state of Nevada. While the post-war years are also part of the Cold War era (described in the introduction of Part VIII), impacts of the Cold War would not be directly experienced at Pipe Spring until 1951. The highlights of this period at the monument include completion of the master plan, the installation of the Bishop Hopkins collection in the west cabin, Custodian Leonard Heaton's acquisition of a new truck, and the Kanab celebration of Utah's Centennial (all in 1947); replacement of the fort's kitchen and parlor floors (1948), its big gates (1949), and catwalk (1950); stabilization and repairs to the west cabin (1950); and a community barbecue attended by Arizona Governor Daniel E. Garvey and other officials (also 1950). Also worthy of note were two reservation fires, one in 1948 and the other in 1950. The April 1948 Indian School fire - which Leonard Heaton and Moccasin residents helped to fight - was the far more destructive of the two. Finally, significant improvements were made to the Heatons' residence during 1948, in part to make the temporary structure more livable, but also to accommodate a growing family.

Conspicuously absent from these years is any dispute over Pipe Spring water between the Indian Service, Park Service, and those cattlemen entitled to a share. In the absence of contrary evidence, it can only be presumed that all parties found their needs being sufficiently met by the existing arrangement.

Monument Administration

During the 1940s, Leonard and Edna Heaton's growing children provided increasing assistance to their parents in carrying out everyday chores, both with personal and monument work. One of the more notable aspects of the post-war years, in terms of day-to-day work, was Heaton's frequent references to help given him by his sons. By the second half of the 1940s, six of the boys - Clawson, Dean, Leonard P., Lowell, Sherwin, and Gary - were of sufficient age and size to help him with many routine maintenance tasks and projects around the monument. Heaton reports in his journals during these years that the boys assisted him with the following kinds of work: dragging the monument roads, hauling cedar wood from the area sawmill for campground and residence fuel, cleaning the fort ponds, cutting up dead limbs, painting monument signage, digging up and cleaning out irrigation pipes, hauling and spreading gravel on monument roads and walkways, and other types of maintenance work. [1325] In addition, all but t he very youngest children were pressed into guide service for the fort during Leonard's absences. His son Gary was only nine years old when Heaton left him "in charge of the fort" for two days while he took annual leave to tend to his fields in Alton, Utah. [1326] Edna Heaton, of course, would have remained on site when Leonard was away, but had much work of her own to do. In addition to her other domestic responsibilities, she took care of three new children born between 1942 and 1947.

Frequently, Leonard Heaton had to be away from the monument. The custodian was required to make two trips a month to Zion National Park to attend staff meetings. Heaton usually picked up supplies at the same time or had repairs made to the truck or generator. He was also expected to attend certain in-service trainings at Zion. In addition to work-related absences, Heaton often spent holidays and annual leave tending to his wheat farm in Alton. His usual days off were Saturday and Sunday, although this schedule sometimes changed to accommodate increased summer weekend visitation. [1327] (Heaton preferred having Sunday off to attend church and to perform church service work. [1328] ) Trips made to get coal in Alton or wood from the area sawmill took him away from the monument, sometimes for the entire day. A typical winter trip to the Alton mine might require waiting in line for four or five hours in an unheated truck, picking up a ton of coal, then having one or more flat tires coming home with the heavy load. [1329] During all these absences - including weekends — Edna Heaton and the older children made themselves available to guide and assist monument visitors. For example, in April 1946 Heaton went to Zion for a five-day fire school, leaving his family in charge. He then took leave to tend his farm in Alton. He wrote after his return, "Back in the job after a week's annual leave. Mrs. Heaton has done a very good job of looking after the monument and visitors have been out." [1330] As in the past, all work performed by Heaton's immediate family members during this period was unpaid.

The Challenge of Living in Post-war Rural Arizona

The early post-war era was a time when many homes in cities and small towns were becoming equipped with such conveniences as electric stoves, refrigerators, and washing machines. Rural areas, however, often lacked commercial electricity for such luxuries. While small gasoline-powered electric generators were not uncommon, such as the one used by the Heatons at Pipe Spring, they varied in how much power they could produce. While Kanab had commercial power from the early 1930s, it would be another 27 years before Moccasin residents enjoyed such service. [1331] This wasn't for lack of interest, however. In 1946 the community of Moccasin attempted to get government assistance in bringing electric power to their area by arranging a meeting with a representative of the Rural Electrification Administration (REA). The REA was established by executive order on May 11, 1935, under powers granted President Roosevelt by the Federal Emergency Relief Appropriation Act. Its purpose was to formulate and administer a program of generating and distributing electricity in isolated rural areas that were not served by private utilities. The REA was authorized to lend the entire cost of constructing light and power lines in such areas, on liberal terms of three percent interest, with amortization extended over a 20-year period. The Moccasin REA meeting was held on September 27, 1946. Among its attendees was Leonard Heaton. Heaton wrote later that the government representative at the meeting "felt there was not enough homes or users to justify a new setup at this time..." [1332] (Presumably, Kaibab Village did not have electricity either, other than that produced by generators.) In 1949 Heaton reported, "Some REA Government men were out signing up for a power line through this area. Hope we get the power soon." [1333] As with many such hopes, patience on the Arizona Strip was a virtue. Moccasin, Kaibab Village, and Pipe Spring National Monument would not get commercial power until April 1960.

One convenience the Heatons did have was a telephone. On numerous occasions, the Heatons received calls at the monument and communicated urgent messages to their neighbors who didn't have phones. [1334] One other "improvement" came to the monument in 1946: a new product for controlling insect pests called "DDT." [1335] While Leonard Heaton did not entirely abandon his old method of pouring gasoline on ant beds he, like millions of his countrymen, now also sprayed them liberally with DDT. A later caterpillar infestation in the willow patch in the spring of 1949 was also treated several times with DDT. Heaton even found this chemical cocktail to be effective against bedbugs when sprayed on the family beds. (Use of DDT was banned in the U.S. in 1972.)

Being some miles off the beaten track (in this case, U.S. Highway 89), official visitors to the monument often dropped in without warning, usually en route to or from southern Utah parks and the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. As Park Service staff worked to finalize the 1947 master plan and prepared to make use of the "on-the-shelf " drawings executed during the war years, Heaton received numerous unscheduled visits from landscape architects, planners, or other officials stopping by to review development plans or to familiarize themselves with the site. As in earlier years, Heaton was quite embarrassed during such unannounced visits, particularly if he was in the midst of an arduous maintenance project and in dirty work clothes. He would later write in his journal comments like, "Enjoyed their visit very much but wish they would notify me when they were coming in so that I would be somewhat prepared to meet them." [1336] Surprise visits by Park Service officials continued to be a bit unsettling to Heaton throughout his tenure at Pipe Spring, for he always wanted them to see the monument - and its custodian - at their very best. At a staff meeting Heaton attended in March 1947, he learned that he would have to get a new uniform that summer and that his efficiency rating would include personal appearance. Heaton became all the more worried about impromptu official visits.

Buffalo Hunts, Rat Roundups, Monstrous Moccasins, and Dinosaur Tracks

Every once in a while, something out of the ordinary would happen in or around Pipe Spring. On May 1, 1947, Heaton reported two rather unusual events. The first happened in the sky: "Twenty large planes passed over the monument today. Seventeen Army 4-engine bombers going south." The second odd happening was on the ground: "Report came in that a buffalo was seen in Pipe Valley yesterday." [1337] Over the next few days, an exciting chase for the buffalo ensued. Heaton wrote in his journal, "Arizona State Deputy Game Warden and others are out trying to find the buffalo. [A] $30 reward for getting him. Hunt going on in cars, trucks, and planes." [1338]

Heaton conducted spontaneous hunts of his own at the monument, although they were for critters much smaller than buffaloes. Despite his continuing to set out poisoned corn and wheat as bait, and his sparing of all monument snakes but rattlers, rats continued to be a problem in the fort and a threat to its antique furnishings. In early August 1947, Heaton reported to headquarters that a "plague of wood rats moved into the fort and did considerable damage to the woodwork and some museum articles before they were caught and driven out." [1339] (He attributed an increase in rodents and rabbits to the widespread killing of coyotes and cats that took place the previous winter.) Heaton referred to this particular incident in his journal as a "rat roundup." [1340] No details were offered on how Heaton spoiled the rats' foray into the fort. (Hopefully, the "roundup" offered the custodian a temporary diversion from the mundane office work he abhorred!) Ridding the fort of rodents was to be a never-ending battle however. Heaton reported in October 1950, "Seems every fall we have a moving day from hills and valleys into the fort building of these pests." [1341]

On June 12, 1947, the nearby town of Kanab, Utah, celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Mormon immigrants' arrival to the Great Salt Lake Valley. [1342] Heaton was elected chairmen of a committee of Moccasin citizens whose purpose was to plan and construct "a Pipe Spring float" for a parade being held as part of Utah's centennial program. "Plans are now to combine the float, making a moccasin of the bottom of the truck, and [commemorating] the naming of Pipe Springs by Jacob Hamblin's party in 1858," he wrote. [1343] Heaton worked for four days on this project. On the day of the event, Heaton described the results of his committee's efforts:

By 10:30 [a.m.] the float representing Moccasin and Pipe Spring was finished and I drove the truck which paraded up and down Main Street in Kanab 3 times. Some 20 floats were there showing history and life in Kanab Stake area. Our float won honorable mention for its flowers that covered the front and edges. [1344] The plan was a canvas moccasin covering the entire truck, with scenery and characters on the back showing the naming of Pipe Springs by Jack [sic] Hamblin and party in 1858. It showed the spring coming out of the rock and meadow, the silk handkerchief and pipe, old guns, camp outfit. Lorenzo Brown as Jacob Hamblin, Leonard P. Heaton as Bill Hamblin, the shooter, and Landell Heaton, a member of the party. During the Centennial Program, Pipe Spring was mentioned a number of times... [1345]

Heaton added in his monthly report that boy scouts from the Moccasin troop represented the "early pioneers" on the float.

While not extremely rare, the discovery of human remains in and around the monument was also an event considered out-of-the-ordinary. One such find took place in June 1947, when Heaton's children discovered an Indian burial in the wash south of the monument. "Upon investigation," Heaton reported to headquarters, "it was found that the winds had uncovered the burial of an Indian of several hundred years ago. The children have been instructed not to disturb it as it might prove of some worth to the Monument and early Indian history." [1346] In July Heaton reported, "Made a trip to where the children found the burial and paint. Part of the head and arm and ribbons exposed and being scattered, so gathered them up and brought them to the fort. Head to the southwest, no artifacts. Noticed a rock at the head, laid out straight." [1347] (The presence of ribbons in the burial raises a question as to the accuracy of Heaton's estimate that the burial was made "several hundred years ago.")

In 1949, while local Moccasin residents were excavating clay and gravel on the reservation at a ridge just south of town to make area road repairs, two Indian burials were uncovered. Heaton reported to Superintendent Charles J. Smith that once the burials were recognized they were left alone, "as the older people have been told about the penalty of molesting Indian burials." [1348] Two other burials had been found in that area several years earlier, Heaton reported to Smith. "There has [sic] been a number of Indian burials found in and around the town of Moccasin over the past 30 years," he added. "Some pottery was found, most of which is now in the museum here at Pipe Spring National Monument." [1349] In March 1950 while Heaton, Assistant Superintendent Art Thomas, and Park Naturalist Merrill V. Walker were looking at "some old Indian relics south of the park," Heaton reported they found yet another burial. [1350]

Indian burials were not the only subject of scientific interest during these years. On July 20, 1949, Heaton spent several hours with two visitors, Dr. Edward H. Colbert of the American Museum of Natural History and another man named Von Frank, hunting for dinosaur tracks six miles north of the monument. Heaton later wrote, "Did not find the first tracks but located another set in the canyon west." [1351] In October Merrill Walker came over from Zion to look for the tracks with Heaton in the same area. Heaton reported, "Found a number, got one and brought it home.... Walker took some pictures of the track here at the fort. He will write Dr. Colbert over findings." [1352] The following summer, Heaton spent time with Dr. Charles L. Camp, a geologist from University of California, looking at the same dinosaur tracks. [1353] In addition to paleontological and geological interest in the Pipe Spring area, a number of botanists visited the monument through the years to study the monument's desert plant life, some from the Desert Botanical Garden in Phoenix, Arizona.

Planning and Development

After the war ended, Park Service officials in Washington, D.C., expected increased interest in and visitation to the nation's parks and monuments. In late 1945 Director Newton B. Drury sent out a letter to all park units asking park administrators to answer two questions: 1) What is the national significance of the area I supervise? and 2) How can it be made to provide the greatest service to the nation? To the first question, Custodian Heaton replied that Pipe Spring National Monument "stands for the hardships, trials, sorrows, joys, deaths, battles, and successes the pioneers passed through to establish the rights of free people in the Rocky Mountains and our present civilization." [1354] It was one of the few western forts constructed for protection of settlers still standing, thus its importance increased through the years, he wrote to the director. To the second question, Heaton opined that the buildings should be restored "to give the visitor a feeling of what the pioneers passed through." [1355] They should be refurnished with antiques of the period and interpreted by persons well acquainted with the history of the region and the west, a person who also had a sincere desire to serve the public, he added. "Better roads" were also needed, Heaton wrote the director.

The monument still limped along with insufficient funds to fully carry out the goals Heaton described. It was unlikely that money would be found for furnishing the house museum, however, when allocations of the period did not even cover some other basic administrative needs, such as personnel and equipment. During the war years, insufficient allocations for Pipe Spring had required occasional transfers of funds from other areas. When Superintendent Smith submitted his preliminary budget estimates for Pipe Spring National Monument for fiscal year 1948, he pointed out to Regional Director Minor R. Tillotson that the estimate of $3,924 represented an increase of $1,723 over fiscal year (FY) 1947. About one-half of the requested budget increase was needed for equipment (a refrigerator for the residence, a new generator, and a two-way radio). Most of the remaining increase was to be used to hire someone to relieve Heaton during his days off and when on official absence from the monument. Smith also wanted to upgrade Heaton's position at an additional cost of $66 for the year. Apparently, the monument did not get the increased funding requested by Smith either for FY 1948 or for FY 1949, for Edna did not get a refrigerator nor Leonard his raise until 1950; the monument didn't get a two-way radio until 1951; and the Heaton family continued to provide guide service during the custodian's absence until 1953 when a seasonal laborer was hired.

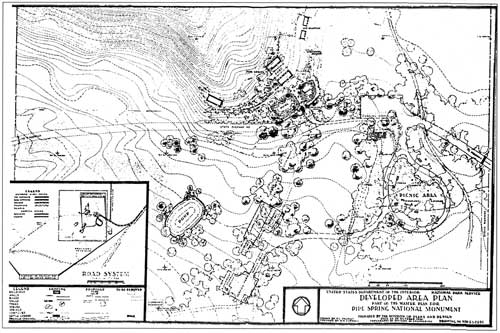

During the fall of 1946, the Western Office, Division of Plans and Design (WODC), collected field data for preparation of the monument's 1947 master plan. Perhaps the most significant change between this plan and the earlier one developed in 1940 was the change in location of the parking area. The 1947 plan called for the parking area to be located directly north of the campground and picnic area and for the old parking area, built south of the fort during the 1930s, to be obliterated. Like the 1940 plan, the 1947 plan called for relocation of the monument road to a point south of the Indian ruins (previously investigated by Jesse Nusbaum and others); all traces of the old road, except for a small section at the east entrance, were to be obliterated. (The one-mile detour section was proposed to be constructed by the Indian Service.) The inadequate slab culvert at the east entrance was to be replaced with a larger concrete box culvert to alleviate flood problems. New buildings proposed included a contact/comfort station, two staff residences ("of Mormon-type stone masonry"), an equipment storage building, and fuel storage house. Additional flagstone walks were proposed to access the historic buildings with the proposed new developments and 18-inch high stone walls were to be constructed in the utility and residential areas. A bituminous-surfaced nature trail was also proposed which would lead to a ridge one-quarter mile northwest of the fort. The plan also called for a restoration of the fort's interior furnishings so that it could be used as a historic house museum. The plan for utilities included construction of one 20,000-gallon reservoir on the hill northwest of the fort and replacement of the gravity flow water system with the installation of a pump. The installation of two five-kilowatt generating plants was proposed to service the electrical needs of the monument's new buildings. The master plan received formal approval on May 15, 1947. (Zion officials gave Heaton a copy of the monument's master plan about five months later.) While project construction program proposals were submitted to fund developments as outlined in the 1947 master plan, the only one of these projects funded and completed between 1946 and 1950 was the one to prevent monument flooding.

|

|

88. Developed Area Plan, 1947 Master Plan for Pipe

Spring National Monument (Courtesy NPS Technical Information Center). (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

On May 24, 1947, Superintendent Smith, Park Naturalist Merrill Walker, Chief Ranger Fred Fagergren, and Regional Chief of Planning Harvey Cornell met at Pipe Spring to inspect the monument and discuss the rehabilitation program for the fort. The men spent several hours considering changes to the flood washes and repairs to the fort. The monument's custodian must have taken it as a hopeful sign. "This is the first visit from park officials for nearly a year," Heaton later recorded in his journal. [1356]

Returning from a long lunch break on July 22, 1947, Heaton was disappointed to learn from Edna that he had missed the visit of some important Park Service officials. Past Director Arno B. Cammerer and NPS engineers Sam D. Hendricks and A. van V. Dunn had stopped at Pipe Spring, accompanied by Merrill Walker. As usual, Heaton had received no notice of their intended visit. Heaton bemoaned having missed them in his journal that evening, "Just because I took an extra hour off at noon, I missed seeing two park men on roads.... It seems like if I stay around waiting for people to come, they never get here, but sure as I leave or [am] in dirty clothes, I always get some visitors." [1357] Heaton was so weary of this sort of thing happening that he finally requested in the September 1947 staff meeting that he be given advance notice of official visits. The truth was, high officials rarely came to Pipe Spring, but when they did Heaton hated to miss them or be caught unprepared.

In August 1947 Heaton reported something serious was threatening the monument's elm trees. During the summer all but two or three of the elms planted by the CCC in 1937 either died or looked as if they were about to die, Heaton reported. Water did not seem to be the problem, he wrote, but woodpecker holes in the trunks suggested insect infestation. Even three of the old trees by the fort showed signs of dying. In addition to the elm problem, a few poplars suffered from insufficient water. In the spring of 1950, Heaton reported the willow patch and Carolina poplars were insect-infested. Later investigation determined the poplar problem was "leaf miners and rollers," which almost denuded some of the trees. Superintendent Smith proposed at year end that funding be budgeted for annual spraying of the monument's deciduous trees in the early spring. Wildlife, on the other hand, was proliferating. The flock of Gambel quail living in and around the monument was estimated in 1947 at 100. [1358] In the fall of 1950, Heaton reported that quail were still "plentiful" in the area. [1359]

The 1937 Ford pickup that Heaton had been driving at the monument had been in need of replacement for many years. Finally in September 1947, much to Heaton's surprise, he was told after a staff meeting at Zion to exchange the old truck for a new 1947 International pickup. "Runs fine," he reported, although it didn't have a heater in it. Given that the custodian's journal for the preceding years is replete with entries about frequent breakdowns and repairs to the old truck, receiving the new vehicle must have been a very welcome event. [1360] In March 1949 he exchanged the International for a 4-speed Dodge truck. Before winter Heaton even got a heater installed in the truck.

From October 1947 through mid-March 1948, Heaton was involved in preparation for and repair work in the fort's kitchen, in particular the replacement of its floors. When this job was completed, Heaton and his brother Grant Heaton commenced work on replacing the parlor floors, and work finished in early April. Heaton also did some preliminary work in preparation for replacing the fort's big gates during the summer of 1948, but did not build the gates and install them until the summer of 1949 (see "Historic Buildings" section for details on these projects). Throughout 1948 Heaton and his sons also did considerable work to improve the family's residence (see "The Heaton Residence" section).

Perhaps the biggest story in 1948 was the Indian School fire that took place the afternoon of April 29. Custodian Heaton recorded the event at the end of the day:

Got a call for a fire at the Indian School at 3:40 [p.m.]. Took all my fire fighting equipment up, but was too late to do much good on the second building, but helped save the third. The fire started about 2:30 in the schoolhouse, either from a defective flu or children playing with matches in a playhouse on north side of the building. By 3:00 this building was falling down. The house north caught fire but was put out once, then the southwest wind carried the flames from the 1st building and fire broke out along the eaves and got in under the roof. When I got there and no chance to get at the fire. It was believed if the park equipment had been there at 3:00 the 2nd building could have been saved. The 3rd building to the east caught fire several times but with tubs of water and extinguisher the fire was kept under control. Very little was saved from the schoolhouse, but practically everything that could be moved was gotten out of the 2nd house. Sparks were blown 100 yards and started [a] fire on the roof of an Indian home and 200 yards to a pile of posts which was charred before the fire was put out. Five men from Moccasin arrived at the fire call first, then several others arrived later. The women folks did a fair job in helping move things out of the house and taking care of them afterwards. By 4:30 or 5:00 both houses had burned to the ground leaving only 3 flues standing. It was all Government property that was lost in the fire. [1361]

Heaton did not report on ensuing events with regard to the replacement of the burned buildings. Later that year, the monument had a little fire scare of its own. "Had a fire in the wash this morning at 4:00 a.m. caused from dumping hot ashes. No damage was done, just burned trash and garbage." [1362] This was the same way the 1942 monument fire had started.

During April and May 1948, Heaton worked on improvements to the monument's drainage system, to prevent future floods, and to its irrigation system (see "Flood Diversion, Irrigation, and Pipelines" section for details). In May Heaton received a visit from Assistant Superintendent Art Thomas, Dell Campbell, and Regional Archeologist Eric K. Reed. The men spent most of a day inspecting the buildings and gathering information about the monument's history and restoration work. [1363] Reed later described the repair work Heaton had done on the fort as "excellent." In June Chief Ranger Fred Fagergren made a fire inspection at the monument. "Found things in pretty poor shape," reported Heaton. [1364] Fagergren's report after this inspection recommended that a generator house be built. Heaton built a small generator house during the last two weeks of July 1948. The structure was located "at the southeast corner of the willow patch, halfway between the residence and Garage No. 2," Heaton reported. [1365] In May 1950 Heaton installed a 55-gallon underground fuel tank to store gasoline for the generator.

Heaton was disappointed to learn at a staff meeting in late June 1948 that he was not going to get a long-awaited pay raise. A few weeks later after the next staff meeting, he met with Thomas "about why I didn't get the raise in pay but doesn't look like I will get one, yet all the other fellows have in the ungraded class." [1366] In September he once again discussed the lack of raise with Thomas: "Talked with Art Thomas about my wages and found out the reason some were not raised is that Pipe has a spindly allotment and not enough to pay the next grade rate of $1.25 so until someone turns loose some more money I am stuck with $1.00 an hour rate." [1367] Considering the Park Service benefited from the unpaid labor of at least half of Heaton's large family, they were getting quite a bargain indeed! The following summer, in August 1949, Heaton took the park ranger's exam in Cedar City, Utah, for the second time. (He had first taken this exam in May 1937. At that time, and presumably in 1949 as well, a college education was still required to attain this position.) There was no report of the results by Heaton.

Some days were more tedious for Custodian Heaton than others at the monument. One can imagine his feelings when, after a hot August in 1948, he wrote in his journal, "Washed the windows in the three fort buildings, 309 separate window panes in the windows, 618 sides to wash. Takes three good hours to go over them." [1368] In early October Heaton decided to relieve a different kind of tedium by taking his wife and 15-month-old baby with him to attend the four-day Superintendents' Conference in Grand Canyon National Park. Heaton's 14-year-old son Lowell was left in charge during the couple's seven-day absence. The meeting was attended by 200 park managers and presided over by Director Drury, Associate Director Demaray, and Assistant Director Tolson. By the last day of the conference, Heaton wrote, "Everyone worn out and nerves on edge. Glad the conference is over." [1369] The Heatons returned to Pipe Spring on October 9 by way of Lee's Ferry. Shortly after his return, Heaton constructed a new coal storage bin from salvaged materials. It was located at the northeast corner of the old cattle corral, south of his residence. "Some job using old scrap lumber and rusty nails," he wrote. [1370]

The winter of 1948-1949 was an unusually severe one on the Arizona Strip. On February 7, 1949, Heaton reported "a lot of cattle are dying of starvation and cold." [1371] Heaton wrote four days later,

A lot of cattle are being driven into the pasture just outside of the monument for feeding and warm water and they are getting into the monument across the cattle guard and gate being left open.... Quite a lot dead cattle being found in different parts of the range. Considerable trouble is being had with different stockmen because they think they are being hit the hardest and want all the snow equipment to work on their place first. Heard that it was all being called off because of the selfishness of two or three men who won't cooperate with the other stockmen. [1372]

On Valentine's Day 1949, the temperature dipped to 12 degrees below zero. Drifting snow blocked roads and mail delivery was infrequent and unpredictable. So many trucks passed over the road hauling hay and feed to suffering livestock that winter that the road through the monument had 18-inch wide, 12-inch deep ruts in it. Heaton's truck became mired on at least one occasion; he towed others out of mud holes when necessary. In addition to truck damage, between 40 and 60 head of cattle got into the monument over cattle guards frozen with snow. He tried his best to fill in the road ruts with sand, predicting "one dirty mess" once spring arrived. On February 22 Heaton's sons reported the ice on the meadow pond was 13 inches thick; the east fort pond was covered with nine inches of ice.

In spite of road problems that always arrived with melting snows, the harsh winter was followed by a glorious spring. Easter visitors came, as they usually did, to celebrate the holiday amidst the monument's budding vegetation. Heaton wrote in 1949,

Easter Sunday, had a large crowd out today. Made no effort to conduct parties through the fort as they keep coming in and out all the afternoon, so just wandered about answering questions and giving information. About 20 cars and 70 or more people out to picnic and outing.... One of the visitors was Mrs. Elvira Winsor Jahovac, great great granddaughter of Bishop A. P. Winsor who built the fort in 1870. [1373]

Heaton reported that April that plum trees on the monument were blooming and swarms of butterflies were attracted to their fragrant blossoms: "Hundreds of small red-spotted butterflies are on the plum blossoms now, the most I have ever seen at this monument." [1374] Only three days later, Heaton wrote, "The small red butterflies have about all left... but there are thousands of white moths, or millers, at night now." [1375] (These moths were responsible for the caterpillar infestation on the willows that Heaton had to spray with DDT.)

During the summer of 1949, Heaton constructed 9 x 6-foot book shelves for his office, which was still located in the fort's lower building, southeast corner of the ground floor. The custodian spotted three or four horned owls living at the monument that summer, roosting during the day among the campground trees or among those near the fort. Two golden eagles were also seen. In August Jay Ellis Ransom, from Desert Plant Magazine, visited Pipe Spring to prepare an article. Natt Dodge (regional office) also stopped by on his way to Zion to visit with Heaton and take pictures of the fort. At the end of the travel year (FY 1949), Heaton reported 1,381 visitors, adding,

This is the largest figure for several years. I am sure if there was a guide on duty all the time we would double our figures, as I am away about half the time, two days Saturday and Sunday, one day every two weeks to Zion, annual leave and holidays and other Government duties, that take me away. Would average only four days out of the week [that] people could have guide service. [1376]

Heaton found himself in a bind. He wanted to welcome as many visitors as he could but had to frequently leave the monument for legitimate reasons. Of course Heaton knew that visitation numbers were important to those in Zion and Washington, D.C. This could have been one of a number of reasons his family members were so willing to offer guide service during Heaton's periods of absence from the site. Had the fort actually been locked up during all the times Heaton was away, visitation figures would have fallen significantly. On the other hand, Heaton's journal and monthly reports document his family's sincere desire to accommodate visitors to this remote site as a simple act of courtesy, thus it would be inaccurate to construe they only helped out to boost travel figures. The monument's custodian had wrestled with the problem of meeting visitors' needs right after the war. In June 1946 Heaton reported,

There has been a question as to just what should be done here at Pipe Spring National Monument now that we are getting visitors every day of the week, especially when they come so many miles to see the fort, and then not be able to get in, or have someone here to tell them the history. The custodian has talked it over with his family and it is agreed that some one of us will be at the monument to show visitors about every day of the week, regardless of compensation we might receive. In this way someone will be here for fire and other protection measures, as well as [for] guide service. [1377]

Zion officials (just like Southwestern National Monuments officials before them) seemed to have no objections to the Heaton family's solution to the problem. Until funds could be found to hire an assistant for Custodian Heaton - a pipe dream indeed! - there seemed to be no alternative to the family but for them to volunteer their services.

It was mentioned in an earlier chapter that Heaton sometimes captured a deer fawn or two, raised them in the meadow, and later sold them to the U.S. Forest Service. Although this practice seems to have been discontinued in the 1940s, Heaton's deer tending days weren't quite over. During the summer of 1949, some reservation Indians found a fawn and brought it to Heaton. A few months later, Heaton wrote of the deer, "The tame deer is getting to be a pest and [we] will have to get rid of it before long. It is bothering the children and may hurt them." [1378] He waited until the spring of 1950 to cart the deer away, which evidently soon became homesick: "The deer we raised and was taken off five weeks ago is back again," he reported in late May. [1379] The deer wasn't the only intruder. Heaton reported in October 1949 that "four or five head of horses keep coming into the monument at night and [are] out before morning, crossing the cattle guard." [1380] These were horses (owned by the Kaibab Paiute) that were attracted to the lush grazing at Pipe Spring. It appears that Heaton's earlier practice of driving them out when he discovered them in the morning had "trained" them — he believed they now left voluntarily before he arose! In September 1950 he reported that Indians' horses "forgot [to leave] and stayed 'til 7:00 [a.m.]. Got in the truck and chased them out two miles." [1381] A few horses continued their practice of grazing on the monument at night, in spite of Heaton's efforts to keep them out. In 1952 he reported chasing trespassing horses out of the monument "with a gun and car." [1382]

In November 1949, at the encouragement of Superintendent Smith, Heaton filled out employment papers for the Washington office to see if could attain a permanent custodial appointment at Zion National Park under a Civil Service grade. In February 1950 Heaton wrote in his journal, "Went to town to get some Civil Service examination papers for a maintenance man position at Zion Park. Got word that I should try for it to keep my job here at Pipe. It doesn't make me feel any too well. I am wondering if it would not be better for me to try and get a farm to work." [1383] Heaton had by then been overseeing the monument for 24 years and was still an ungraded Park Service employee making only $1 an hour. Finally, Heaton was given "competitive status" under Executive Order 10080 in May 1950. [1384] He did not get the position he applied for at Zion but in August 1950 he learned that he would receive a modest raise of 17.5 cents per hour. He wrote in his journal, "Beginning August 6, 1950, will receive $100.66 each two weeks in place of the $81.50." [1385]

The winter of 1949-1950 was another very cold one. Heaton reported a few days before Christmas 1949, "Another very cold night and day, 6 below zero this morning.... Spent the day in the office taking care of papers, writing letters. Feet freezing. Keeping up the fire in the old pot-belly stove which doesn't give out enough heat to reach the desk." [1386] In the midst of sub-zero temperatures, poor road conditions, and no visitors, Heaton received one encouraging word at the start of the new decade: "Electric power lines ready to go as soon as the Government gives the go ahead sign. Contracts let to several companies." [1387] The prospect of power lines coming to the area was probably as welcome to Heaton as the acquisition of his new truck in 1947. The two electric generators at Pipe Spring seemed to have required as much time for repairs (and caused as much aggravation) as the old truck had. Once again, however, his vision of electric power lines was premature.

When Heaton attended staff meeting on March 1, 1950, he was directed to make a name change: "Got instruction to change the name of Pipe Spring National Monument to Pipe Spring National Historic Park. It is OK with me, if I can get the wage and money that goes with a Park name." [1388] No further mention was made of a name change, which was never carried out.

During an inspection of the fort by Zion officials in the spring of 1950, it was learned that several trees very close to the fort had been struck by lightning in previous years. Heaton told the men that lightning had never struck the fort but that lightning storms had struck violently on Rocky Point, just behind the fort. Superintendent Smith later wrote Regional Director Tillotson,

It occurs to us that with the lack of fire protection facilities at Pipe Spring, a lightning protection system should be installed on the fort itself. It would seem possible that some time lightning may strike the fort itself and set a fire which would be hard to cope with. Although we cannot accomplish it with funds available this year, it is believed that a lightning system should be designed and installed on the fort in the near future. We will want the advice of Regional Architects and Engineers before going ahead with the lightning protection plan. [1389]

The subject of lightning protection came up every few years after Superintendent Smith wrote this memo to Tillotson, but it appears that costs prohibited further action until June 1956 when five lightning rods were finally installed on the fort. [1390] In addition to lightning protection, Zion officials recommended in 1950 that future budget estimates include funds for the purchase of a Pacific-type fire pumper and 500 feet of hose, to be located near the fort ponds for protection of the fort. The monument obtained this fire protection equipment in 1953.

|

|

89. Crowd gathered in meadow for the community

barbeque at Pipe Spring, April 29, 1950 (Photograph by Merrill V. Walker, Pipe Spring National Monument, neg. 396). |

Unquestionably, the biggest event in the spring of 1950 was a barbecue held on April 29 for Governor Daniel E. Garvey. The fete was planned to convince the governor and other high officials of the need for an all-weather Hurricane-Fredonia road. Heaton cleaned all the fort's windows and had a couple of his sons help him clean the meadow "for the big eat," as he described it. On April 22 Heaton started building the fire pit for the barbecue. On the 25th, he fussed with the arrangement of museum articles ("for the crowd," he wrote) and on the 26th picked up two additional pit toilets at Zion. On the evening of the 28th, the custodian prepared the meat for cooking, putting it in the pit at 6:00 a.m. the day of the big event. The meat cooked for 10 hours until about 4:00 p.m. Meanwhile the huge crowd began arriving at 12:30 and by 2:30, Heaton wrote, "we had the place full. Used the parking area, 3 rows of cars on east and south of the meadow, 216 cars with 816 people visiting the monument." [1391] Art Thomas, Fred Fagergren, Merrill Walker, and two Zion rangers helped with parking and guide service.

The program that day was at 2:00, and "eats" at 4:00, held on the meadow. Among the dignitaries were Governor Garvey, Mr. and Mrs. Dudley Hamblin, Dr. and Mrs. Herbert E. Gregory, officials from Zion and Grand Canyon National Parks, and Forest Service and Indian Service officials. [1392] Heaton reported that county supervisors from Mohave and Coconino counties in Arizona and from Washington, Iron, and Kane counties in Utah attended the event, along with representatives from Fredonia, Flagstaff, Moccasin, Short Creek, Kanab, Hurricane, St. George, Cedar City, "and several other places" also attended the barbecue. Heaton later reported "everything was just fine, the crowd was very well-behaved and after it was over very little cleaning up to do for such a large crowd." [1393]

Heaton later reported it was the largest crowd at the monument "since about 1929 when we had several large tours stop here on their way from Zion to Grand Canyon National Parks." [1394] Only one unfortunate occurrence marred that day's festivities: Heaton's seven-year-old daughter Olive fell from the railing of the speakers' stand and hit a sharp board, cutting a four-inch long, one-inch deep gash in her right leg, below the knee. The wound required 12 stitches to close. Of all Heaton's children, little Olive seems to have been the most accident-prone (see the section, "Births, Deaths, and Accidents").

Heat and drought seemed to arrive early on the Arizona Strip in 1950. Heaton reported that month, "Stockmen have been moving a lot of cattle this past week by the monument to their summer pastures. Also hauling some water from the monument to tide them over 'til rain comes." [1395] In early June he reported, "More stockmen hauling water to supplement the shortage of water in their wells." [1396] Otherwise, the summer was not very eventful.

Fires were always a special danger during the hot, dry summers. On June 26, 1950, a fire broke out at Kaibab Village. Unlike the 1948 Indian School fire, this time no buildings were destroyed. Heaton reported,

Was called to a fire at the Indian Village at 11:30. The fire started in some weeds at the corrals. Burned one stack of lumber. With four of my boys, took park fire extinguisher, shovels, and helped in confining the fire to the pile of lumber. Another pile of lumber caught fire next to a barn but with our equipment [we] stopped it before it got to burning. There was only women folk and children on the place. In about 1? hours the fire was out except some hot coals buried deep in the sand and wet ashes. [1397]

Summer heat guaranteed more visits by area residents to Pipe Spring National Monument, children in particular. In July and August 1950, Heaton reported the majority of "travel" to the monument was by local folks coming to swim in the meadow pond. [1398] What seems remarkable is that no visitors were ever involved in swimming accidents during all the years the meadow pond was used recreationally. Diving into the flagstone-lined meadow pond did have its hazards, however, as discovered by one of Heaton's sons in 1949 (see "Births, Deaths, and Accidents" section).

In the spring of 1950, Heaton received a request for a list of plants that grew on the monument from Pauline Patraw of Santa Fe, New Mexico, who was compiling a publication on Upper Sonoran Zone plants for the Southwest Monuments Association. In response, he compiled a list of cactus, other flowering plants, trees, shrubs, and bushes and sent it to her in July. [1399] In early September 1950, Heaton received a visit from former Superintendent Paul R. Franke (now in the Washington office) and Natt Dodge. Franke suggested Heaton get some geese or more ducks as well as more fish for the ponds, and for him to plant an orchard "where the old one used to be." The men promised as soon as monument visitation picked up they would help get Heaton more money to fix up the museum.

Post-war Visitation

While visitation figures had risen the first post-war year from 635 to 1,193, it declined again in 1947 (760) and 1948 (839). [1400] Travel increased in 1949 (1,290) and again in 1950 (2,352), although the latter jump in visitation is attributed to high attendance at the barbecue held in April 1950. [1401] As in years past, school children of all ages visited the site, especially near the end of the school year. In May 1950 an outing of 50 Dixie College students interrupted Heaton as he undertook stabilization work on the west cabin's south wall. While Heaton was on annual leave that month Edna Heaton took charge of tours for school children from Alton, Orderville, and Glendale, Utah. Also in May a group of 49 students from Fredonia High School camped out at the monument. Kanab seventh graders also came to Pipe Spring on an outing that month. This kind of school activity was fairly typical for the monument in late spring.

In addition to school outings at Pipe Spring, the monument received visitors associated with Church-sponsored organizations. Heaton reported in May 1946 that a party of "72 young men and boys gathered here for an outing from Kanab Stake under the direction of Edward C. Heaton, chairman of the Aaronic Priesthood, a Church group. Lunch and ball games were enjoyed." [1402] In March 1947, while Heaton was making a trip to Zion for a staff meeting and supplies, a group of 60 to 70 students from the Utah Seminary visited the monument. Heaton family members gave them a guided tour through the fort. In May 1949 Heaton guided a groups of 60 Kanab Stake Beehive Girls through the fort. After this outing, Heaton reported, "Gave first aid to one girl that was stung by a wasp. Killed a rattler the girls discovered at the southwest corner of the fort." [1403] In addition to many such groups visiting the monument, Heaton was frequently asked and agreed to give talks on Pipe Spring and on other southwestern parks and monuments to adult groups in Kanab, Moccasin, and Fredonia. In May 1949 Edna Heaton gave several artists a tour through the fort: Ivan House (Portland, Oregon), Avard Fairbanks, and Elbert Porter (both from Salt Lake City). Indian Service officials also made a few visits to the monument during this period.

As in earlier years, the fort was a favorite destination for descendents of the early Mormon settlers of Utah and Arizona or for others with family connections to Pipe Spring. Only a few of them will be mentioned here. In August 1946 a man named Heber Monair came by the monument and told Heaton he had once worked at the ranch when it was owned by David D. Bulloch and Lehi W. Jones. Monair said he had been the ranch foreman in 1895-1897. As he did with many others who had once lived at Pipe Spring, Heaton questioned him about the period and later made notes of their conversation. [1404] In August 1947 visitors to the monument included some great-grandchildren of Bishop Anson P. Winsor. On a Sunday afternoon in September 1949, Heaton reported, "A group of Sons of Utah Pioneers organization stopped for lunch and to see the fort." [1405] On Easter Sunday in 1950, visitors included more descendants of Anson P. Winsor, including 86-year-old Joseph Winsor, who provided Heaton with information about how the east and west cabins were originally used. [1406] Mrs. Sarah Terry Winsor was also among the Easter visitors. She lived at Pipe Spring in 1874-1875 and operated the telegraph office. In April 1950 visitors included the children of Luella Stewart Udall, the first telegraph operator at Pipe Spring. In October 1950 Heaton reported that Mrs. Parsellow S. Hamblin Alger, daughter of William (Bill or Gunlock) Hamblin and members of her family visited the monument. This was the Hamblin whose marksmanship, according to Heaton, "gave Pipe Spring its name in September 1858." [1407]

From time to time, Heaton received unexpected after-hours visitors at the monument, such as one he reported entered on a Saturday night in December 1948: "An Indian woman walked in last [night] about 10:30. There must have been a drunken party in town. Took her home." [1408]

In addition to the events described above, the following sections describe events from 1946 through 1950 as they relate to specific areas of interest.

Births, Deaths, and Accidents

Living on the remote Arizona Strip posed certain risks, particularly years ago when driving over miles of rutted dirt roads was an ordeal in and of itself. One had to travel to Kanab to see a doctor or to reach a hospital. (For serious medical conditions or operations, the Heatons went to the hospital in St. George). Farm and ranch work have always had inherent hazards. What is surprising is the low number of accidents Heaton reported. Most accidents or injuries involved either him or his family, rather than visitors, and these (judging from Heaton's journals and monthly reports) did not occur frequently.

Accidents near the monument were often road-related, such as the one Heaton reported in 1946:

At 2:00 a.m. [on] May 23rd, a truck driven by Mr. A. Jesup of Short Creek, Arizona, driving west on the road just east of the monument failed to make the sharp turn about 500 feet east of the monument and overturned. In it with Mr. Jesup were two women, three children, and an elder man. No one was seriously injured and after an hour and one-half, with the help of the custodian and members of his family, the truck was righted and the people cleaned up.... This turn should be fixed before someone is killed or maimed for life. [1409]

It appears that nothing was done to remedy this particular road problem. Area residents had a hard enough time just keeping the approach roads maintained in driveable condition, much less redesigned for safety (see "Area Roads" section).

What stands out most about accidents reported in Heaton's journal was the recurrence with which his daughter Olive was involved in them. Her fall from the railing of the speakers' stand at the April 29, 1950, barbecue has already been mentioned. That was not the first time she had suffered serious injuries, however. On a Tuesday in early January 1947, Heaton reported. "...when returning from taking my 3 boys to school at Moccasin the rear door of the car came open and pulled my 4-year old girl Olive out and injured her very seriously. Bruising her on the left side and back, sending her unconscious 'til 6 or 7 a.m. on Wednesday morning." [1410] Heaton took Olive to the family doctor in Kanab the day after the accident (Wednesday). After checking her, the doctor told the concerned father that everything was all right, except for the bruises and shock. The following year, in May 1948, Heaton reported that he "...had to take my 5-year-old daughter Olive to the hospital for an appendix operation. It was in the last stages before it would have ruptured. She was resting well last night." [1411] The little girl also was involved in a very serious farm-related accident a few years later (see Part VIII).

From time to time in his journal, Heaton reports area searches for missing persons. On May 26, 1947, Heaton joined a search party of between 75 and 100 men to hunt for his missing uncle, Lynn Esplin. Esplin, according to Heaton, "through worry and sickness wandered away from his sheep camp." [1412] It was discovered that he had fallen from a 300-foot ledge in a side canyon of Orderville Gulch, northeast of Zion. Heaton and other men carried Esplin's body out of the canyon on foot, then took it by horseback to the nearest road, all together a two-hour ordeal. [1413] Returning from a trip to Zion on May 28, Heaton stopped in Orderville to attend the funeral services for his uncle.

Oddly, with the frequency that rattlesnakes had been spotted at the monument in the 1930s and 1940s, no venomous snakebites were ever reported by Heaton. While swimming at the monument was very popular, only one swimming-related accident was recorded during these years and it involved one of Heaton's teen-aged sons. In the summer of 1949, Heaton reported, "My son Dean had an accident while swimming. Dove too straight into the pond and hit his face on the side, cutting a wound on the bridge of the nose, a hole through the upper lip, skinning the chin and breaking the inside corner of his two upper teeth. Had to have the doctor take two stitches in his lip; also wrenched his neck a little." [1414]

More common than accident reports at the monument was Heaton's news of a birth or a death. Pregnancies and births among the extended Heaton family appear to have been so common that such experiences by his wife provoked little comment in Heaton's journal. One has to make some effort to discern when they occurred. For example, on May 20, 1947, Heaton wrote, "Took Mrs. Heaton to the hospital, nothing much to report today." [1415] About two weeks later he mentioned, "Brought Mrs. Heaton and baby home feeling pretty good." [1416] (It is unclear if the trip to the hospital was for a check-up or for the baby's delivery.) Just a few of his children's births are mentioned in his journal. Only one of a number of funerals attended by Heaton during this period will be mentioned here. In 1948 Heaton attended funeral services for Fred Bulletts, a Kaibab Paiute man. Heaton wrote in his journal, "A large crowd of Indians and whites [were] there." [1417]

Historic Buildings

The Fort

No restoration or repair work was done to the fort in 1946 and 1947, except for Heaton's efforts in April 1947 to clean tree roots out of the pipeline that led into the spring room. [1418] In September that year, Heaton visited a blacksmith in Kanab to make arrangements for making the big locks for the fort gates. During October 1947, Heaton planed lumber to be used as new floorboards in the fort's kitchen. In late November he removed the old kitchen floor (not the original). He reported during this process, "Worked all day taking up the floor of the kitchen of the fort. Found the boards very rotten and hard to get up. Broke most of the floorboards getting them up as the nails were rusted and the boards rotten. The floor joists were about 1/2 rotted away. Those in the west end were the worst, two or three of the east end fairly good, where there was more ventilation and less seepage of water. The back part is very damp and wet." [1419] He finished removal of the deteriorated kitchen floor in early December. While removing the floor, he made a discovery of some original flooring: "Finished cleaning out the kitchen rooms of the fort. Found a small section of the original floorboards. They are 1 full inch thick, 4-1/2, 5, 5-1/2, and 6 inches wide and tongued and grooved, nailed with the old square-cut nails to a 2 x 6." [1420]

Several other discoveries were made during Heaton's work on the fort's floors. Before the new floor joists could be installed, the kitchen's two cupboards that flanked the fireplace had to be removed. Under the north cupboard Heaton found "a teaspoon of a plain 'Roger Nickel Silver.' Under the south cupboard a small, very flat case with a flowered handle silver coated 'Standard,' also at the edge of the hearth stone an iron handle of some tool. Too rusty to determine just what it is." [1421] Work was suspended for several weeks while Heaton waited for Assistant Superintendent Art Thomas to come and inspect the project. Thomas approved the work at the end of December and Heaton proceeded with installing the joists and floorboards in January 1948. He poured cement along the kitchen's back wall and around the fireplace for the floor joists to rest on, and also braced the staircase. Unlike the first time the floor was replaced in 1926, this time an effort was made to make the replacement floor more rot-resistant. The joists were painted with hot linseed oil and wood preservative; more sub-floor ventilation was also provided. [1422] A large rock that lay beneath the center of the kitchen floor had to be chipped down to accommodate a 6 x 7-inch concrete strip centered beneath the floor to support the new joists. Toward the end of January, Heaton began relaying the kitchen floor, completing this job in early February. In March he repeated much the same process in the parlor (west room), only this time with the help of his brother Grant Heaton, hired as temporary laborer. The parlor floors were replaced by the month's end. Other work in the kitchen and parlor at this time included woodwork, plastering, and painting. [1423]

In mid-January 1949, Zion officials asked Heaton to make up a report on all stabilization work that had been done to the fort since 1942. He completed his report on February 1, 1949, recording the information on a Ruins Stabilization Record. (It is believed that no photographs were taken during any of the work.) Erik Reed later transferred this information to a copy of the earlier HABS (Historic American Building Survey) drawing of the fort. [1424]

The next big project at the monument was reconstruction of the fort's big gates. The first replacement gates were built and installed by Heaton in 1928, but these apparently weren't authentic enough for later Park Service officials. The new ones were to be replicas of the originals. [1425] In June 1948 Heaton prepared the lumber for the job by tonguing and grooving it with a plane borrowed from William C. Bolander of Orderville, Utah. No more work was done on this job until almost a year later. In April and May 1949, Heaton built gates for both ends of the fort, using square nails in the construction of one if not both sets of gates. [1426] In early June he put in a new sill for the west gate. When he and three of his sons tried to hang the west gates they discovered that they didn't fit, so they had to be cut down in size. Heaton wrote that he "painted the sill timber of the west gate with old motor oil, creosote and wood preservative and termite poison. Hope it will last 30 or 40 years." [1427] In mid-June the east gates were taken down. Heaton reported, "Found the sill log almost rotted away under the door frame uprights. Cut the door frames off about 2 inches to get [to] the solid wood. Replaced the sill timber and painted it with preservative. Bored some holes in the door frames about 12 inches up from the bottom to fill with preservative to keep out termites and rot." [1428] The east gates were hung on March 14 and 15 with the help of Heaton's teen-aged sons, Dean and Lowell. Heaton cemented around the frames of the gates, reset the top and middle hinges, and installed new locks. No other work worthy of note in the fort took place until July 1950. A considerable amount of plaster had fallen from the walls of the spring room and there were signs of stone deterioration. Zion officials recommended in April that Heaton install a few drains and replace the plaster with water-resisting cement to retard capillary action and preserve the room's walls. Heaton carried out this work in July. [1429]

In October 1950 Heaton removed and replaced the deteriorated catwalk near the fort's west gates. [1430] The fort's north balcony was in such poor condition, that in September 1950 Heaton installed three braces beneath it. "They don't look too good but [were] put up as a safety measure," he wrote. [1431] On November 18, 1950, the monument had a visit from Regional Architect Kenneth M. Saunders and his wife. Saunders returned the following day to inspect the fort and cabins. Heaton wrote, "Mr. K. M. Saunders called again about noon to see the fort. He is quite taken up with it. Wants to see it fixed up. Is going to try and get some money for repairs on the porches and southwest corner [of the west cabin]." [1432] Regional Director Tillotson later transferred $500 of ruins stabilization funds to Pipe Spring to enable additional work to be done to reinforce the fort's balconies during fiscal year 1951 (see Part VIII).

The West Cabin

The west cabin was in dire need of stabilization work by the end of World War II. In November 1946 Heaton noted in his journal, "The west cabin is again settling on the southwest corner, causing a large crack to come over the west door and west end of the building." [1433] Heaton thought spring water behind the west cabin was causing the building to settle. He called Art Thomas' attention to the problem during his and Erik Reed's visit of May 1948. In early April 1950, Superintendent Smith requested ruin stabilization funds for the west cabin from the regional office and submitted an outline of proposed work. The sinking of the cabin's southwest corner had caused a large crack from floor to ceiling on the cabin's west side. An old spring developed by early settlers on the hill above the building had become choked with weeds and grass, causing water to spread downward toward the cabin, Smith reported. Moisture under the foundation was causing slippage of the shale beneath the cabin. Smith's plan was for Heaton to install gravel drains to divert the spring water away from the cabin and to pull the cabin wall back into place with steel rods and turnbuckles. After the wall was back in place, Heaton was to reinforce the foundations with concrete footings and repair the cracked portions of the wall. [1434] It is presumed the funds for materials were received, for Heaton carried out the work as outlined by Smith from April to June 1950, at times with the help of his sons Leonard, Lowell, Sherwin, and Gary. [1435] Heaton then relaid those portions of rock walkway that had been removed in front of the cabin prior to stabilization work.

Monument Walkways

The monument's sandstone walks laid during the 1930s began to look a bit worse for the wear by the post-war years. Heaton blamed badgers for undermining about one-third of the walkway to the west cabin; this much he replaced in the summer of 1947. In 1949 Heaton was given permission to remove the stone walks that linked the fort and east and west cabins and to replace them with stone-bordered gravel walkways. This work was accomplished in July.

The Heaton Residence

On March 13, 1946, Zion's Assistant Superintendent Dorr G. Yeager, Chief Ranger Fred Fagergren, and a clerk ("Mrs. Russell") came to the monument to appraise the value and take pictures and measurements of the Heaton family's monument residence, the old CCC infirmary. (Fagergren came along to check the monument's fire extinguishers.) Heaton got the impression the men were making plans for disposal of the building, pending construction of the new residence. Heaton wrote optimistically in his journal, "Well, I think this summer will be our last here as a family." [1436] That was to be a highly inaccurate prediction. The appraisal of quarters was for the Government Accounting Office. The appraisal reported the residence had five rooms with bath, kitchen, and two sleeping porches. [1437] A small gasoline generator furnished electricity and a coal-circulating heater heated the residence. The family used a coal-burning cook stove with an attached hot water heater. There was no refrigerator or cooler and the grounds were not landscaped, the report stated. "All space is decidedly below average and is so situated that the custodian is subject to continual interruption by visitors." [1438]

In September 1946 Heaton wrote Zion to say that because the stoves were located on the east end of the residence the west part was nearly impossible to heat. Heatons asked Zion officials if he could dig a basement of sorts under the west part of the house and install a furnace there, but they turned down the request. So the family continued, as they had in the past, to heat the uninsulated wood frame building with coal and wood. After the war, the little 32-volt electric generator the Heaton family had relied on for electricity since 1940 began giving constant problems. "Sure wish we could get a 110 V motor for the washer as I spend 2 to 4 hours each week to get the 32 V [volt] plant to running." [1439] When Heaton couldn't solve the problem, he had to drive it to Zion for repairs and was given a temporary generator in its place. Even when it was working the little generator could no longer meet the family's needs. (They could use a washing machine or they could have lighting, but apparently not both at the same time.) In early December 1946, Heaton installed a 110-volt light plant provided by Zion. He then changed the electrical wiring so he could use either the 110-volt or the family's old 32-volt light plant. The family planned to use the 32-volt plant to run the washing machine and for late night use and to use the 110-volt plant for evening, when lighting demands were heaviest.

|

|

90. Custodian's residence (old CCC infirmary), 1946 (Photograph by Russell K. Grater, Pipe Spring National Monument, neg. 372). |

In January 1947 a windstorm removed part of the residence roof. While Heaton did some repairs that month, he and a few of his sons did most of the repair work the following April. In December 1947 Heaton received word that an allotment of $600 was being given the monument to make improvements to the old CCC infirmary where his family had resided now for six years. To Heaton, it seemed a waste to pour money into such an old and temporary building, particularly since the plans for a new residence had been finalized. The building was cramped year-round and very cold in the winter. The best use of the funds, he thought, was to build on an addition to the residence and to insulate it. After discussing the matter with Edna Heaton and drawing up a sketch plan, he went to a Zion staff meeting with Mrs. Heaton in tow. The couple met to discuss their proposal with Zion officials. Their plans were approved in December.

Work on the residence took place during all of 1948 and proceeded slowly as Heaton's other monument responsibilities took priority. In February 1948 Heaton and four of his sons first raised the ceiling of the residence a foot, then used 68 sacks of rock wool to insulate the walls. In May and June, several interior walls of the residence were changed and the southwest corner room was enlarged, adding about 56 square feet of living space. Two fire hydrants were installed for fire protection, one 20 feet north of the residence and one 15 feet to the south. In July Heaton and two sons reroofed the garage. Work continued in the fall on plumbing, sewage, and interior painting. Heaton decided in December to change the cesspool for the residence to the south of the building, some 40 feet to the old CCC drain and sump hole. This required constructing a new cesspool and putting in a new sewer line to his house. Finally, as they appear to have done at the onset of each winter, Heaton and his sons boarded up the porch of the residence and around its foundation to keep out wind and snow.

When spring came in 1949, Heaton and his sons leveled up the ground on the south side of the house to plant lawn, trees, and shrubbery. His efforts to plant and grow a lawn continued throughout the summer. "All the area to be planted," he wrote. [1440] Heaton also picked up 400 bricks at Zion to rebuild the flue for the heater in the residence, a job he worked on the following September and October. At year's end, Heaton installed a hot water heater in the residence kitchen. In January 1950 Heaton and two of his sons, Clawson and Dean, put in a new sewer system which consisted of two 50-gallon iron tanks and just under 100 feet of open-end drain tile. The tile was buried about 2.5 feet with gravel around it. That August, Heaton laid new linoleum in the residence dining room and kitchen. Edna Heaton finally got an electric refrigerator in May 1950 from Zion. [1441] Compared to what they moved into 10 years earlier, the Heatons were now practically living in the lap of luxury!

During the summer of 1950, a fire inspection was made of the monument. In his report to Regional Director Tillotson, Superintendent Smith stated that even with all the improvements to the residence made by Heaton,

... it remains a virtual firetrap, tinder dry most of the time with winds across the area that this spring reached a velocity of 40 m.p.h. It would take but one small spark to wipe out the only government quarters in the area and all of the personal belongings of the ranger and his family. This building should be replaced with a modern residence as soon as possible. [1442]

The only other work to the family's quarters during this period was in November 1950 when Heaton replaced the old battens on the building with new ones. All the family's efforts to improve the residence, as it turned out, would be very worthwhile for the Heatons lived in the remodeled CCC infirmary for another 10 years.

Fish and Ponds

The meadow pond was the focus of much activity in the post-war years. Heaton began draining it in May, an event he later reported several local children took advantage of: "Some little Indian boys raided the meadow pond I was draining to clean out and took all the camp fish, including the old carp I had here since the spring of 1926, weighing about 17 lbs. and 30 inches long." [1443] Once the pond was drained, Heaton's sons and some of their Moccasin friends cleaned out the trash so that it could be refilled and used for swimming. By early August, Heaton reported, "A lot of swimmers are coming out to cool off." [1444]

The fort ponds were drained and cleaned again in July 1947. Heaton reported, "Ponds drained this morning. It looks like most of the trout died because of circulation of water in the ponds.... My boys got into the ponds and caught 9 big carp and 50 or more trout which I had them put into the meadow pond, while we clean out these by the fort." [1445] Heaton's sons, Clawson and Leonard P., cleaned muck and trash out the fort ponds. Heaton replaced an old wooden culvert with an eight-inch metal culvert, then refilled the fort ponds. He reported it took three days to refill them. There are no reports of restocking the ponds with fish during this period.

In July 1948 Heaton noticed some unusual coloring in the fort ponds, which he later reported at the August staff meeting. His monthly report stated,

One of the most unusual sights at the monument is the red coloring that appears from time to time on the bottom of the west pond by the fort. At times it gets to be a bright red and covers large areas between the weeds that grow in the ponds, some times hanging low on the bottom and at other times rising in small clouds several inches above the bottom. [1446]

In September Botanist Lyman Benson of Pomona College, Claremont, California, inspected the ponds. Heaton gave him a sample from the ponds to analyze, but he was unable to identify what was producing the odd color. The following May 1949, Heaton reported, "The purple coloring in the west pond is spreading and seems to be killing out all the plant growth where it is." [1447] Perhaps to try to solve the problem, the fort ponds were cleaned out in August 1949 and again in April 1950.

Flood Diversion, Irrigation, and Pipelines

In an attempt to prevent future flood damage on the monument, changes were made in 1948 to the drainage wash and culverts. The work for flood diversion plans was outlined during the May 24, 1947, visit of Smith, Fagergren, Walker, and Cornell, referenced earlier. Zion officials returned in October to look over the wash and culvert situation.

Work undertaken in April and May 1948 consisted of modifying the wash and installing a new 36-inch culvert and headwalls near the campground area. Two of Heaton's brothers, Grant and Sterling Heaton, assisted with this work. The new flood diversion arrangement required a change in the irrigation pipeline to the campground and to the trees by the east entrance. The culvert headwalls and changes to the irrigation system were completed by mid-May.

In addition to relocating some irrigation pipeline, Heaton was frequently faced with the need to unclog existing pipelines. [1448] In June 1948 Heaton reported, "The 2-inch pipeline to the Indian ponds to the east of the monument are almost completely plugged up. Tried to find the stoppage but it will necessitate digging up several lengths of pipe to get it cleaned." [1449] In August the spring pipeline in the fort became clogged again with tree roots, requiring Heaton's attention. [1450] In September he was still working to unclog pipelines, only this time the stoppage was in the lines coming from the ponds. Heaton used a hydromatic air pump to clean out the pipeline on this occasion. From time to time, the custodian pondered ways he might improve the water system to reduce such demands on his time. In January 1948 he wrote, "Spent the day in digging up the 1-inch pipeline to water trough. Had to take up two lengths to get it cleaned out so decided to change it over to the main water line to campground area. Will have to get a few fittings to make the connections. Will do away with the 1-inch line from the spring and will take that line up this spring." [1451] In addition to clogged lines, at times Heaton had to dig up and replace pipelines that froze and burst over the previous winter. As with many maintenance chores, Heaton's sons were often recruited to help him with such jobs.

Floods

In spite of the improvement work of 1948, Pipe Spring National Monument had not seen the last of its floods. On August 11, 1950, Heaton described what was by now an all-too-familiar scene:

At 3:15 [p.m.] a heavy storm of hail and rain hit the monument. By 3:30 water was running everywhere, leaves and small twigs being knocked off the trees and plants. The ground was white with hail in 10 minutes. The heaviest hail was to the south of the monument about 2 miles. The ground stayed white till after dark. By 3:45 p.m. a flood came down the wash which was almost twice too large for the culvert and again as in 1942, the camp area, road, parking area and south was flooded, leaving piles of trash and sand over the area which will take several days to clean up. There was so much trash and hail in the flood that it built its own bank as it went along in places, 2 feet high. Very little washing was done because of the weeds and plants. The roads were blocked by washout and sand drifts across the road southwest and east and north. [1452]

Heaton described the event as "not quite as large a flood" as the one in 1942. Still, the flood deposited an estimated two to 18 inches of sand on the road from the parking area south of the fort to the east cattle guard and on the north side of the campground, and washed trash into monument trees and brush. [1453] Heaton hired Kelly Heaton to remove the sand from the monument road and campground area with a tractor and scraper later that month. Heaton then hauled in clay and several loads of gravel to build up the road where sections of it had washed out.

|

|

91. Monument campground and picnic area, June

1950 (Pipe Spring National Monument, neg. 8). |

Soil Conservation

On August 21, 1947, Soil Conservationist Paul L. Balch (regional office) made one of at least three visits to Pipe Spring during the post-war years. During this visit he inspected the monument's vegetation with Grand Canyon National Park's Ranger Art Brown and checked it for erosion conditions. While noting the climax grass in the area was Galleta (Hilaria jamesii), it had been almost entirely eliminated by overgrazing and now was replaced by cheat grass (Bromus tectorum). Although grazing in the monument was no longer allowed, wind erosion had caused blowouts and sand dunes. Sheet and rill erosion was present, but no active gully erosion was observed. Balch noted that erosion conditions within the monument were worse than on the reservation's grazing lands located just outside its boundaries. He recommended reseeding the monument with native Galleta grass to deter further wind and water erosion. [1454]