|

Pipe Spring National Monument Arizona |

|

NPS photo | |

Life Source in a Dry Land

Water is a powerful force in human affairs. For millennia Pipe Spring has drawn a succession of peoples—either as an oasis on their journeys or as a water source for permanent settlements. The spring is on the Arizona Strip, a vast, isolated landscape that lies between the Grand Canyon and the Vermilion Cliffs of northern Arizona. It is an arid and seemingly uninhabitable region, but hidden geological forces have brought water to a few places here, opening them to human settlement. The Strip is the first in a series of terraces that step up to the high plateau of central Utah some 200 miles to the north. There, water from rain and snow-melt percolates down to a hard shale layer and flows southward to the base of the Vermilion Cliffs, where it is forced to the surface at places such as Pipe Spring.

For 12,000 years the Strip was a travel corridor for nomadic big game hunters, hunter-gatherers, and traders, the first people to be sustained by these springs. Ancestral Puebloan peoples were the next to settle in the area, followed by related Southern Paiute tribes who live here still. Beginning in the 1700s, missionaries and explorers visited the area to chart the land. In the mid-1800s the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons) came upon the Arizona Strip while seeking water and land to expand their new homeland in the West. Each of these cultures affected how the others adapted to this hard and demanding place in the high desert.

The Peopling of the Arizona Strip

Ancestral Puebloans

Semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers traveled the Arizona Strip until around 300 B.C., when they were supplanted or assimilated by ancestral Puebloan peoples. The earliest of these people lived in pithouse villages, combined farming with gathering and hunting with bow and arrow, wove baskets, ground seeds with shaped stones, and traded salt, turquoise, and seashells. As their culture evolved, they turned increasingly to farming, began making pottery, created more sophisticated stone tools, and built above-ground pueblos. Between 1000 and 1250 the ancestral Puebloan culture gradually faded from the Arizona Strip. There was a prolonged drought during this period, and perhaps the land could no longer support such a concentrated population. They may have simply moved away or been absorbed by various Southern Paiute bands.

Paiutes

The Kaibab Paiutes were superbly adapted to their harsh environment. Moving in small, semi-nomadic groups, using natural shelters or building kahns of juniper branches and brush, they were better able to glean the region's resources than the sedentary Puebloans. They cultivated maize and beans at places like Pipe Spring but also moved seasonally to hunt deer, pronghorn, rabbits, and lizards. They gathered grass seed, piñon nuts, roots, and cactus fruit. From hemp dogbane fiber they wove nets to trap rabbits, whose pelts were used to make robes. Basketry, their finest material achievement, met a variety of needs: seed fans for beating seeds from bushes, conical harvesting baskets, winnowing baskets, seed gruel bowls, meat baskets, pitch-coated water jugs, and women's hats. This efficient way of life sustained them well until the arrival of Europeans in the late 1700s, after which introduced diseases and Navajo and Ute slaving raids reduced their numbers from 5,500 to 200 by the 1870s.

Missionaries and Explorers

The first Europeans to encounter the Southern Paiute tribes. Catholic missionaries Antanasio Dominguez and Silvestre Velez de Escalante, likely owed their lives to them. During the missionaries' unsuccessful 1776 expedition from Santa Fe to California, the Paiutes provided them with food and told them of a route across the Arizona Strip that skirted the Grand Canyon. Mormon missionary Jacob Hamblin undertook the first of his missions to the Hopi tribes in 1858, stopping at Pipe Spring. Explorer John Wesley Powell first visited Pipe Spring in 1870 between his trips down the Colorado River. Powell and Hamblin traveled across the Arizona Strip contacting the Indian tribes to promote peace with the settlers. Powell's topographical survey crews stopped at Pipe Spring several times in the early 1870s.

Mormon Pioneers

By the late 1850s the Mormon Church was calling its members to spread out from Salt Lake City to found settlements in southern Utah. Some ranchers moved on into the Arizona Strip, drawn by its high-desert grasses and water sources like Pipe Spring. Mormons soon controlled most of the area's water, further stressing Paiute tribes, whose populations were already declining. In 1863 James Whitmore was one of the first Mormons to move sheep and cattle onto the Strip. He acquired title to 160 acres around Pipe Spring, built a dugout and corrals, and planted an orchard and vineyard. The following year Navajo Indians began raiding Mormon livestock on the Strip, and in 1866 Whitmore's stock was stolen. During an attempt to recover his livestock he and his herdsman were killed. This resulted in several revenge killings between Mormons and Indians. In 1868 Mormon militiamen built a small stone cabin at Pipe Spring as a stronghold against continuing Navajo raids.

Pipe Spring is situated at the foot of... the Vermilion Cliffs, and is famous throughout southern Utah as a watering place. Its flow is copious and its water is the purest and best throughout that desolate region.

—Clarence E. Dutton, Tertiary History of the Grand Canyon District, 1882

Ranch and Refuge

The Mormon Outpost

The ranch at Pipe Spring was part of Brigham Young's vision for the growing Mormon population. Mormons often tithed (gave 10 percent) to the church in the form of cattle, and the growing tithing herds of southern Utah needed more space. Young also needed a source of beef and dairy products to feed hundreds of laborers working on the Mormon temple and other public projects in St. George, Utah. Noting the presence of water at Pipe Spring and the expanse of free grazing land on the Arizona Strip, Brigham Young decided to create a tithing ranch and business venture here. He purchased the land from James Whitmore's widow and appointed Anson Perry Winsor as the first ranch manager.

In September 1870 Young and Winsor stepped off the rough outlines of the ranch's main structure. Built to safeguard the ranch manager and his family, "Winsor Castle" had two sandstone buildings facing a courtyard enclosed by gates. The main spring was covered by the structure. Even before the fort was completed, a relay station for the Deseret Telegraph system was installed, connecting this remote outpost on the Arizona Strip to other Mormon settlements and Salt Lake City, Utah.

From 1871 to 1876 the ranch was a beef and dairy operation. Every two weeks Winsor took butter, cheese, and cattle to St. George. The ranch prospered under a succession of managers, and the herd grew rapidly. In 1879 it was running more than 2,200 head of cattle. But dry seasons, along with the large herds at Pipe Spring and other ranches, began to damage the range. Pipe Spring suffered economically, although it continued to be an active ranch and resting place for travelers.

In the 1880s and 1890s the remote fort at Pipe Spring became a refuge for wives hiding from federal marshals enforcing anti-polygamy laws. Polygamy was the early Mormon doctrine of men having more than one wife. A number of women and their children hid at Pipe Spring to save their husbands and fathers from prosecution. Faced with the confiscation of church property and the declining range, the Mormon Church sold Pipe Spring ranch in 1895.

Although private, it continued as a central ranch for large herds of cattle on the Arizona Strip. Its doors remained open to travelers of every stripe: cowboys, traders, salesmen, and neighbors. Hired girl Maggie Cox Heaton recalled: "I welcomed lots of strangers and made pies and cakes and bread for 'em . . . . It was a busy place, a real busy place because of the cattle."

During this period the Kaibab band of Paiutes struggled to survive as Mormon settlements displaced them from their traditional hunting, farming, and gathering lands. In addition, overgrazing worsened by drought reduced the availability of native foods, leading to starvation. Increasing federal concern for their welfare prompted the formation of the Kaibab-Paiute Reservation in 1907, which included a small portion of their traditional lands. Pipe Spring, surrounded by the newly formed reservation, remained a private ranch. Conflicts over water rights and land use issues developed during this period and persisted for many years.

The National Monument

Steven Mather, the first director of the National Park Service, paved the way for Pipe Spring to become a national monument. Following the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916, Mather actively sought public support for the agency and the parks that composed the National Park System. He worked closely with the railroads and their bus companies to bring Americans to the large western parks, including Zion and Grand Canyon. In the early 1920s the Utah Parks Company, a transportation subsidiary of the Union Pacific Railroad, transported tourists from Zion to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon across the hot, dusty roads of the Arizona Strip. Mather realized the value of Pipe Spring as a cool oasis and potential lunch stop for the tourists making this rugged trip. Moreover, Mather was fascinated by the history of Pipe Spring and the old fort. He suggested its addition to the National Park System, and on May 31, 1923, President Warren G. Harding signed the proclamation setting aside Pipe Spring National Monument.

Pipe Spring Today

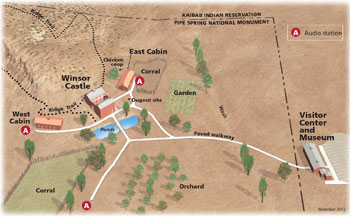

(click for larger map) |

Pipe Spring National Monument offers a glimpse of American Indian and pioneer life in the old West. Winsor Castle can be seen by guided tour every half hour. Visitors can see the rest of the monument at their leisure—cabins, ponds, corrals, orchard, and garden. The joint Tribal-National Park Service visitor center provides a schedule of daily programs at Pipe Spring and information on other public lands. The museum focuses on Kaibab Paiute history and introduces the history of Mormon settlement in the area. A short video provides an overview. The 1/2-mile Ridge Trail has excellent views of the Arizona Strip, Mount Trumbull, the Kaibab Plateau, and Kanab Canyon. The park is closed Thanksgiving, December 25, and January 1.

For Your Safety The park's livestock are not tame; keep a safe distance. There are rattlesnakes and other desert wildlife in the area.

Accessibility The visitor center and gift shop are wheelchair-accessible. Paved walkways lead to all the historic structures, but the interiors are not wheelchair-accessible.

Directions Pipe Spring, 14 miles southwest of Fredonia, Ariz., is reached from U.S. Alt-89 via Ariz. 389. From I-15, Utah 9 and 17 connect with Utah 59 at Hurricane, Utah, which leads to Ariz. 389.

The Kaibab Paiute Reservation encompasses more than 120,000 acres of plateau and desert grassland surrounding the park. The tribe retains rights to one-third of the water flowing from the spring. Part of the Southern Paiute Nation, the Kaibab band has 240 members, whose traditional language is Southern Numic. Agriculture, tourism, and the tribal government sustain the economy. The tribe offers interpretive programs on its culture and leads tours of ancient rock art sites. It is an active partner with the park. Members work as seasonal rangers and help tell the Pipe Spring story from the Paiute point of view.

Source: NPS Brochure (2008)

|

Establishment Pipe Spring National Monument — May 31, 1923 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora, Pipe Spring National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR-2008-131 (Walter Fertig and Jason Alexander, October 2008)

Arizona Explorer Junior Ranger (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Brief Historical Sketch of Pipe Springs Arizona (Arthur Woodward, 1941)

Cultures at a Crossroads: An Administrative History of Pipe Spring National Monument Intermountain Region Cultural Resources Selections No. 15 (Kathleen L. McKoy, 2000) (HTML edition)

Ethnographic Overview and Assessment: Zion National Park, Utah and Pipe Spring National Monument, Arizona (Richard W. Stoffle, Diane E. Austin, David B. Halmo and Arthur M. Phillips III, July 1999, revised 2013)

Foundation Document, Pipe Spring National Monument, Arizona (November 2015)

Foundation Document Overview, Pipe Spring National Monument, Arizona (January 2015)

Geohydrology of Pipe Spring National Monument Area, Northern Arizona U.S. Geological Survey Water-Resources Investigations Report 98-4263 (Margot Truini, 1999)

Geologic Map of Pipe Spring National Monument (April 2009)

Geologic Map of Pipe Spring National Monument and the Western Kaibab-Paiute Indian Reservation, Mohave County, Arizona USGS Scientific Investigations Map 2863 (George H. Billingsley, Susan S. Priest, and Tracey J. Felger, 2004)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Pipe Spring National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2009/164 (J. Graham, January 2010)

Historic Furnishings Report, Pipe Spring National Monument: Winsor Castle (HS-1), East Cabin (HS-2), and West Cabin (HS-3) (Jerome A. Greene, 2004)

Historic Resource Study: Brigham's Bastion — Winsor Castle at Pipe Springs and its Place on the Mormon Frontier (John Alton Peterson, Date Unknown)

Historic Structure Report, History Data Section: Pipe Spring National Monument, Arizona (A. Berle Clemensen, December 1980)

Information Brief: Vegetation Mapping at Pipe Spring National Monument (2011)

Junior Arizona Archeologist (2016; for reference purposes only)

Junior/Senior Ranger Activity Book, Pipe Spring National Monument (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Pipe Spring National Monunent (March 2000)

Master Plan, Pipe Spring National Monument, Arizona (March 1978)

Monitoring and Analysis of Spring Flows at Pipe Spring National Monument, Mojave County, Arizona NPS Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-97/125 (Richard Inglis, July 1997)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Pipe Spring National Monument (Susan A. Tenney, September 28, 1984)

Pipe Spring National Monument Historic District (Boundary Increase) (Kathy McKoy, July 5, 2000)

Oral History Collection, Pipe Spring National Monument, Moccasin, Arizona: Volume II (Mary Jane Lowe and Catherine R. Williams, 1996)

Physical Resources Information and Issues Overview Report, Pipe Spring National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/WRD/NRR-2009/149 (David Sharrow, September 2009)

Pipe Spring Southwestern Monuments Special Report No. 14 (Vincent W. Vandiver, February 1937)

Preliminary investigation of structural controls of ground-water movement in Pipe Spring National Monument, Arizona USGS Scientific Investigations Report 2004-5082 (Margot Truini, John B. Fleming, and Herb A. Pierce, 2004)

Remote Sensing Investigation at Pipe Spring National Monument (Blake Weissling and William A. Dupont, Center for Cultural Sustainability, The University of Texas at San Antonio, June 2013)

Statement for Management, Pipe Spring National Monument (July 1990)

Statement for Management, Pipe Spring National Monument (July 1995)

Summary of Spring Flow Decline and Local Hydrogeologic Studies, 1969-2007, Pipe Spring National Monument NPS Technical Report NPS/NRPC/WRD/NRTR-2007/365 (Larry Martin, April 2007)

Vascular Plant Flora of Pipe Spring National Monument: 2008 Update (Walter Fertig, November 13, 2008)

Vegetation Classification and Mapping Project Report, Pipe Spring National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR-2008/122 (Janet Coles, Aneth Wight, Jim Von Loh, Keith Schulz and Angie Evenden, September 2008)

Vegetation Management Plan Phase I: Alternative Actions, Pipe Spring National Monument (Craig Johnson, Michael Timmons and Colleen Corballis, March 16, 2009)

Vegetation Management Plan Phase II, Pipe Spring National Monument (Michael Timmons, Craig Johnson and Colleen Corballis, May 2010)

Vascular Plant Species Discoveries in the Northern Colorado Plateau Network: Update for 2008-2011 NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR-2012/582 (Walter Fertig, Sarah Topp, Mary Moran, Terri Hildebrand, Jeff Ott and Derrick Zobell, May 2012)

pisp/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025