|

Prince William Forest Park

An Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER THREE:

THE EFFECTS OF SEGREGATION ON PARK MANAGEMENT

No account of Prince William Forest Park's early growth and development would be complete without giving recognition to the effects of segregation on the planning process. Prince William Forest Park was substantially developed between 1936 and 1950 in rural Virginia. Although the official policy of the NPS was one of non-discrimination deference was paid to "local custom" when developing parks in southern states. [129]

To understand the role segregation played in the development of the park it is necessary to identify the key decision makers. Critical input was provided by the NPS staff, camp users and, to a lesser extent, area residents.

The NPS was divided into regions. Prince William Forest Park fell into Region One headquartered in Richmond, Virginia. Early in the planning process a tug-of-war developed between the Richmond office, headed by M. R. Tillotson, and the Land Planning Division of the NPS in Washington, headed by Conrad Wirth, assisted by Matt Huppuch.

Mr. Tillotson felt very strongly that the planners of Prince William Forest Park recognize

the long-standing attitudes and customs of the people, which require, as a fundamental, that recreational areas and facilities for the two races be kept entirely separated. Such a policy should not be considered discriminatory, since it represents the general desire of both races. [130]

In contrast to Mr. Tillotson's views, Mr. Wirth was obliged to uphold the beliefs of his bosses, Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, and Harry Hopkins, administrator of the FERA. Progressives formed in the same mold as President Roosevelt, Ickes and Hopkins fought for equal rights for blacks. [131] Within the Interior Department, Ickes insisted

that no race, or creed or color should be denied that equal opportunity under the law. . . .Times have changed for all of us. . . .If we are to enjoy the rights and privileges of citizenship in the different world that lies ahead of us, we must share in its obligations as well as its responsibilities. This principle applies to all of us, Caucasian, and Asiatic and Negro. [132]

At issue were these two points: a) would the area be divided into separate camps for white and black and b) how would roads and entrances reflect the separation of the races. Caught between the Washington and Richmond offices were the two early managers of the area, William R. Hall and Ira B. Lykes. Hall and Lykes also came into contact with groups sponsoring organized camping in the park which constituted a third and equally forceful body of opinion.

An incident occurring in July 1941 illustrates the attitudes of many park patrons. Contrary to policy, someone in the office of the superintendent of the National Capital Parks issued a permit for the Girl Scouts of Washington, D. C., to use an unused portion of Cabin Camp Two housing the Girl Scouts of Arlington, Virginia. Wisely, Miss Eleanor Durrett, director of the Girl Scouts of Washington, D. C., wrote a letter to Miss Ida Fleckinger, camp director for the Arlington Girl Scouts, requesting her permission to use the vacant cabins in Unit C. Miss Fleckinger promptly reminded Ira Lykes that

. . . the facilities and program have been planned for white campers only. A mixed group of colored and white campers living simultaneously in the same camping units will not bring the desired results in the state of Virginia. [133]

Clearly, the "customs of the people" were incongruous with the principles of equal opportunity upheld by Secretary Ickes, to the vexation of Hall and Lykes.

The issue of racial segregation was most hotly debated between 1935 and 1939 when the cabin camps were being constructed. No one wished to be drawn into a controversy over segregation, aiding the search for a workable compromise. [134] What developed was an interesting divergence between policy and practice about which little was said. [135]

As can be seen on the 1939 Master Plan in Appendix III, the area was divided into separate sections for white and black campers. The cabin camps were numbered in the order in which they were built. Camp One was built in the section set aside for Negroes and the facilities were designed to meet the needs of underprivileged blacks in Washington, D. C. [136] Official recognition could not be given to this arrangement, therefore responsibility for the racial composition of the camp was assigned to the "maintaining agency" as follows:

Our policy is not to construct camps for any particular organization but to provide sufficient facilities to meet community needs, those facilities include provision for both white and colored wherever such arrangement is satisfactory to the maintaining agency. [137]

Thus, by placing access to the cabin camps under the control of the organizations using the facility Wirth was able to bow to prevailing racial attitudes without officially endorsing racial separation. By 1942 Camps One and Four had become known as Negro camps and Camps Two, Three and Five as white camps. (See Illustration Six for details on maintaining agencies.)

ILLUSTRATION VI

SEGREGATED USAGE OF CABIN CAMPS

| Camp 1 - | Negro YMCA |

| Camp 2 - | Social Welfare Group Arlington Girl Scouts |

| Camp 3 - | Family Service Association for White Children. It was built primarily for expectant mothers, mothers with new-borne babies and mothers with children up to 3 years of age. It was only used for 1 year for its original purpose. Its flexibility allows other uses. |

| Camp 4 - | Designed for Negro mothers and children, same as Camp 3. |

| Camp 5 - | Washington Salvation Army |

| CCC Camp - | Can be used for group purposes, not designed for organized camping. |

** Based on minutes of the meeting of the NCP officers and the Social Service Agencies of Washington, D. C. area, December 11, 1942.

As plans were drawn for the park's entrance and interior roads the issue of racial separation again arose as a major concern of the Richmond office. Mr. Tillotson recommended "separate entrances to each the White and Negro areas be established" to "prevent public access to" organized camping areas thereby making it impossible for "patrons destined to the Negro day use area" from having access to "White camping areas." [138] (See Appendix VII for copies of Tillotson and Wirth's letters.)

In response, Wirth stopped short of making a counter proposal to the Richmond plan but noted the increase in cost of two entrances and the fact that the necessary signs "informing the public of the segregation of the races" was "objectionable. [139] The Washington office favored one entrance over the Quantico Reservation. Circumstances prevented the issue from coming to a head. Lack of funds for road construction allowed time for representatives of the Richmond and Washington offices to meet and work toward a compromise. Their deliberations produced no less than three separate road plans. (See Appendix VIII for a description of each plan.)

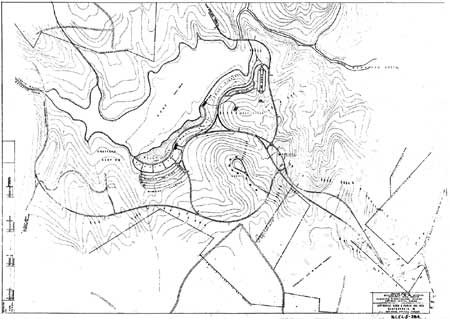

The most elaborate day use and entrance plan provided for two separate entrance roads converging on a double-looped control circle which would divide white and black patrons to routes connecting to separate day use areas bordering a lake. Amenities included athletic fields, a boat house and pavilion, and large parking lots in each day use area. Revised in 1942, this plan retained the concept of a traffic control circle and separate roads leading to white and black day-use areas. (See map in Illustration Seven.) Today, all that remains of this plan is a vastly scaled down circle in front of park headquarters.

ILLUSTRATION VI

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Debate over the placement of the entrance road delayed the construction of other key buildings in the park. The superintendent's residence, park headquarters, and a permanent utility area could not be located until the location of the entrance road was finalized.

A decisive meeting was held on October 4, 1939. [140] It was determined that one entrance from Dumfries, Virginia, would be built at the intersection of Route 1 and Route 629. The entrance road would follow Route 629 for a short distance to a one-point control circle at the intersection of the main entrance road and the roads to the day use and organized camps. Actual construction was delayed until the right of way could be purchased and the necessary funds appropriated. (See Chapter Four for acquisition details.) Elated by the breakthrough Inspector Ray M. Scheneck, who had worked on the park steadily since its inception, suggested "October 4 should be declared as a day of annual celebration for the Chopawamsic Area " and an open house "should be held on that day." [141]

An apparent victory for the Washington office, this decision was actually a well disguised compromise. Pending completion of the entrance road there would be two effective entrances: one off Route 234 into the black camping and day use area and one off Route 626 and Joplin Road into the white camping and day use areas. [142] The lack of funds for land acquisition and road construction brought on by the pending involvement of the U. S. in World War II meant the single entrance road so detested by the Richmond office was far from becoming a reality. Regardless, Wirth could point to the absence of discrimination in the official design of the park. The road was built in 1951.

The battles waged between the Washington and Richmond offices of the NPS over camp facilities and access roads had little bearing on the day usage of the park. This is not to suggest that racial prejudice did not exist in Prince William County. Simply stated, from 1935 to 1950 there were no day use facilities to speak of in the park. The Pine Grove Picnic Area was not constructed until 1951. The few roads in the park were made of rough gravel, uninviting to motorists. Casual sightseeing was further discouraged by signs which read "Federal Reservation. Closed except to persons holding camping permits." [143] Were that not sufficient to deter the curious, recent memory of the OSS occupation was enough to convince the local population that the park was off limits.

Race relations in Prince William County during this period are described as a time of peaceful coexistence by white residents. Area blacks remember rigid codes of discrimination which bound one from entering white churches, stores, restaurants, or theaters when an invited entrance left one open to "getting your feelings hurt." [144] Even the county courthouse provided separate bathrooms for white and black citizens. With few exceptions the dependence of the small black population in the county on the white majority for jobs discouraged flagrant, mass violations of the accepted code. When it occurred, defiance was on the interpersonal level. For example, Miss Annie, a highly respected black midwife, recalls refusing food or drink if acceptance meant consuming it in a segregated section of a home or restaurant. [145] Adherence to the code was the norm, however, leaving area whites to believe they were blessed with a "good bunch of Negroes here." [146]

Only after 1950 did the park experience substantial day use. Whites and blacks used the Pine Grove Picnic Area without incident. Area residents assumed the park was integrated from the beginning. [147] Only one violent incident has ever been linked to racial tension. On June 23, 1960, a group of white postal employees, having consumed two kegs of beer, decided to oust a group of blacks using an adjacent softball field. Words were exchanged "whereupon a postal employee threw a bottle at a Negro and another shoved a small boy." The conflict escalated. A "Negro inflicted minor knife wounds on a postal employee," a "white threw a baseball bat and hit a Negro." In all about 350 people were around. Ten to twelve state troopers responded to the call that a "riot" was in progress. The violence ended in about 15 minutes. Two blacks and one white man were arrested and turned over to the state police. The park ranger on duty believed the two kegs of beer were the principal antagonist and subsequently alcohol usage was banned from the park. Preferring to call the incident a "disturbance" and not a "riot," the ranger noted it was the "only incident of this kind in the park. . .involving White and colored boys." [148] [sic]

Prevailing racial separation among organized campers became a concern of park management. In 1956 a program was instituted by the park naturalist to encourage interaction between the organized camps. A "Friendly Forest Fair" was initiated to unite the camps in an "annual festive holiday." [149] Exhibits were planned to provide an "exchange of ideas for nature recreation" and encourage "good quality nature and wood crafts." [150] Optimistic in concept, the Friendly Forest Fair met with only marginal success. Only Camp Lichtman and Camp Pleasant, black camps, took an interest in the project and put forth the greatest effort, producing some fine displays. The white camps, which had not placed a high value on the event, were overshadowed and immediately objected the "competition [had] no place in camp life." A discouraged park naturalist concluded that they had "missed the spirit of the event" and recommended that it be discontinued. [151] Today, attempts at upgrading the awareness of nature among patrons of the organized camps is conducted on a camp-by-camp basis.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

prwi/adhi/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 31-Jul-2003