|

Rainbow Bridge

A Bridge Between Cultures: An Administrative History of Rainbow Bridge National Monument |

|

CHAPTER 7:

The Modern Monument: Managing Rainbow Bridge, 1955-1993

When Congress passed the Colorado River Storage Project Act in 1956, Rainbow Bridge NM was already part of the national recreation lexicon. While Park Service personnel, politicians, and environmentalists sparred over the proper and effective means to protecting the bridge from the inevitable encroachment of Lake Powell waters, the monument still required daily management. Despite the national attention focused on this remote 160 acres of federal land, the practical considerations of daily visitation, trail maintenance, and cooperation with the Navajo Nation continued. This chapter focuses on the decisions and plans that made that daily process both possible and productive. Much of the tenor of today's monument was shaped in theory and practice between 1956 and 1993 by dedicated Park Service personnel who stayed focused on "at hand" issues in spite of the national furor over the integrity of the monument's boundaries. This period began with the Mission 66 program and culminated with the General Management Plan of 1993. Because of the unique location of Rainbow Bridge NM, bordered on three sides by the Navajo reservation, as well as the controversial history of the Paiute Strip, the evolving relationship between the Park Service and the Navajo Nation dominated most decision-making issues. Between 1955 and 1993, modernism and traditionalism continued to intersect at Rainbow Bridge.

With the dam at Glen Canyon a foregone conclusion, local Park Service personnel turned their attention to the internal needs of the monument. Trail improvements, rest room facilities, and maintenance were just some of the issues at hand in 1956. Visitation had increased steadily from 142 people in 1923 to 1,081 in 1955. In the decade after World War II, park visitation nationwide increased every year, reaching a record high of more than 50 million people in 1955. [304] This figure represented a 236 percent increase in nationwide visitation since 1941. Since its beginning in 1916, the National Park Service operated under the philosophy of Stephen Mather: encouraging tourism brought people to the parks which translated into congressional support for the national park system which in turn ensured the survival of the parks. It was a good philosophy, but it assumed limited visitation growth. No one at the Park Service could have predicted the general post-World War II affluence that most Americans enjoyed. Nor was anyone prepared for the way that affluence translated into dramatic increases in park and monument visitation. This intense shift to maximum use of the parks by the public meant exponentially greater pressures on all Park Service personnel as well as individual park resources. The popular phrase among Park Service personnel during the 1950s was that the public was "loving the parks to death." [305]

The Park Service's philosophy progressed into one that encouraged development and control at the individual park level as a means of preserving and maintaining park resources for the longest possible period. In 1962, Yellowstone superintendent Lemuel Garrison called this new approach the "paradox of protection by development." [306] The idea of protecting the park system through planned development was the backbone of Director Conrad Wirth's Mission 66 program. Succeeding Newton P. Drury in 1951, Wirth inherited a Park Service administration plagued by complaints from visitors over the condition of park resources and the lack of public facilities. Historian Bernard DeVoto, in his famous 1953 Harper's Weekly article, stated flatly that many of the most popular national parks should be closed because of poor conditions. DeVoto was one of the first people to make public the poor living conditions of Park Service personnel employed at various high-profile destinations such as Yosemite and Yellowstone. For all his bluster, though, DeVoto was right about one major point: the park system needed a general planning overhaul, and Wirth designed the Mission 66 proposal to meet that need.

Mission 66 was a ten-year plan which focused on renovating existing park facilities as well as public use resources. Wirth announced the plan at a Washington, D.C. banquet on February 8, 1956. Personnel at Navajo NM, led by Superintendent Foy L. Young, had already prepared a prospectus for implementing Mission 66 at Rainbow Bridge NM. Young's prospectus was completed by July 1955. Review of the plan continued through the remainder of 1955. One month after Director Wirth's announcement. Associate Director E.T. Scoyen approved the summary prospectus for Rainbow Bridge NM. [307] Planning was tentative in early 1956, given the uncertainty of the final scope of the Colorado River Storage Project. Park Service personnel revised the prospectus on the assumption that Congress would approve the CRSP, stating, "completion of the Glen Canyon Dam by the Bureau of Reclamation will open an entirely new era in our operation and management of this area. It is estimated that at least 10,000 visitors a year will then reach the monument, via boat and trail." The basic problems that Park Service personnel faced revolved around the fact that Rainbow Bridge NM was completely undeveloped. Based on the projected completion date of Glen Canyon Dam and the creation of Lake Powell, they barely had ten years to get ready for the definite and massive influx of visitors who would reach the monument via the Lake Powell corridor. [308]

The formal Rainbow Bridge Mission 66 prospectus, submitted April 23, 1956, called for enlarging the monument's boundaries to accommodate necessary facilities, trail improvements, construction of utility and residential buildings, utility systems, and some level of permanent staff. One year later, Director Wirth approved the prospectus. The development plan included a visitor center, campfire circle, campground, signage, and comfort stations. It also provided for both year-round and seasonal staffing and the facilities necessary to accommodate those additions. No independent supervision existed at this time at the monument; the Superintendent at Navajo NM also managed Rainbow Bridge. Management of the monument was not transferred to the auspices of Glen Canyon NRA until 1964. Bearing this in mind, the Mission 66 prospectus for Rainbow Bridge was a radical departure from the management philosophy employed up to this point at the monument. In that context, Mission 66, as it was applied at Rainbow Bridge, represented the best example of dynamic Park Service management in the ever confrontational 1950s. Within one year of recognizing what the CRSP would mean to visitation at the bridge, the Park Service responded with a plan that would meet those demands. [309]

Unfortunately, the application of the Mission 66 prospectus ran into difficulties between 1957 and 1966. There was some activity toward improving trails in the monument. But trail improvements and other development involved land beyond the monument's boundaries. Since the monument was bordered on three sides by the Navajo reservation, this meant cooperating with the Navajo Nation. Visitation was so infrequent at Rainbow Bridge before the 1950s that development had not been an issue. As a result, Park Service personnel were not often exposed to the opportunity to negotiate directly with the Navajo Nation over any significant issues. These opportunities grew more numerous as the need to develop and manage Rainbow Bridge grew more intense.

In 1956, Glen Canyon Dam was at least five years from completion; indeed, after the success of the Sierra Club at Echo Park Canyon it was possible that Glen Canyon Dam might suffer a similar defeat in spite of Congressional approval of the CRSP. Environmental groups such as the Sierra Club wielded genuine political power in the mid-1950s. In the meantime, Park Service personnel were faced with implementing much needed improvements at Rainbow Bridge. Senator Barry Goldwater spearheaded one of the largest trail improvement projects in 1959. Goldwater owned the primary interest in Rainbow Lodge, located at the foot of Navajo Mountain. The lodge's manager and co-owner, Myles Headrick, thought that Lake Powell would definitely mean a new, water-based line of visitation to the monument. This would have definitely cut into the lodge's traditional customer base. In response, lodge management decided to improve the existing land-based line of travel from the lodge to the monument in an attempt to make trail approaches to the bridge as inviting as water approaches. Based on this belief, Headrick persuaded Goldwater to lobby the Department of the Interior for approval to improve fourteen miles of trail from Rainbow Lodge to the bridge. The plan met with some initial resistance. But key NPS personnel, including then Regional Director Hugh M. Miller, lobbied to see the trail improved. On August 5, 1959 the Park Service's efforts met with approval from the Navajo Nation. The Nation viewed the improvement of the trail as mutually beneficial to themselves and the Park Service. The Nation's only stipulation was that the majority of men hired to carry out the improvements be Navajo and that construction remain limited to the linear boundaries of the proposed trail. [310]

The trail improvements proposed by Goldwater and Headrick raised an interesting problem between the Park Service and the Navajo Nation, a problem the Park Service had not encountered before. Most of the proposed trail was outside the boundaries of the monument. BIA Acting General Superintendent K.W. Dixon pointed out to Hugh Miller, then NPS Region Three Director, that the proposed trail would require a right-of-way grant from the Nation. The Park Service believed it only needed a BIA permit and the consent of the Nation to conduct immediate improvements and future maintenance. But consent from the Nation only authorized work to commence and did not guarantee any future agreement. [311] To make matters worse, between 1959 and 1961 the issue of protective measures at the monument consumed Park Service personnel. Trail improvements as well as applications for formal right-of-way were put on the back-burner while the Park Service and the Bureau of Reclamation negotiated over protecting Rainbow Bridge from the waters of Lake Powell.

The controversy over protective measures did more than de-emphasize Park Service plans for trail improvements. It also heightened awareness among the Navajo Nation over the potential commercial significance of Lake Powell and Glen Canyon NRA. The Nation knew that it had a vested interest in maintaining as much shore access to the future lake as possible. That access promised real economic potential in the form of docks, concessions, and tour operations. This meant that negotiations over the proposed trail improvements and the associated rights-of-way had to be conducted in light of what those rights-of-way meant to Tribal commercial development at Lake Powell. During negotiations over the trail improvements, the Park Service realized that it needed some form of a "cooperative agreement" with the Nation in order to commence improvements and continue effective management of the monument.

The cooperative agreement was a prerequisite for authorizing Park Service funds to improve non-Park Service lands. NPS Solicitor Richard A. Buddeke noted to Miller that based on the Basic Authorities Act of 1946 (60 Stat. 885; 16 U.S.C., Sec. 17j2b) the Park Service could appropriate funds for trail improvements and maintenance for lands "under the jurisdiction of other agencies of the Government, devoted to recreational use and pursuant to cooperative agreements." [312] The "other" agency in this instance was the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Field Solicitor Merritt Barton observed that without a cooperative agreement, the Park Service would have no legal authority to construct or maintain the trail to Rainbow Bridge. [313] Pursuing the cooperative agreement raised issues regarding the status of the land in question as well as the status of lands that provided future water access to the monument via Lake Powell. The process of improving the horse and foot trail to Rainbow Bridge was no longer the simple request of Myles Headrick, it was the watershed for negotiating the legal status of lands that would be extremely valuable after 1962 (the year Glen Canyon Dam was proposed to be completed).

In January 1963 water began to fill behind Glen Canyon Dam, forming what is now known as Lake Powell. At the same time that the Park Service was negotiating with the Nation over access to Rainbow Bridge, the management authority over the bridge changed hands. During these initial negotiations, Park Service personnel raised the question of who should manage Rainbow Bridge in the long term. For immediate work projects, such as the proposed trail improvements, Miller suggested that Navajo NM Superintendent Art White continue in his dual capacity as acting superintendent of Rainbow Bridge. Miller also suggested that in the future, after Glen Canyon NRA was developed, Glen Canyon staff be charged with administering and protecting Rainbow Bridge. [314] This suggestion was not lost on regional administrators. In June 1962, before Lake Powell began rising, the Bureau of Reclamation and the National Park Service entered into a Memorandum of Understanding regarding the management and development of the lake. The Bureau of Reclamation took responsibility for facilities and resource management related to the operation of Glen Canyon Dam. The reservoir (Lake Powell) was created for the purpose of fulfilling the intent of the Colorado River Storage Project; consequently, Reclamation retained control of the lake's water level and flow as a method of responding to power needs along the project's corridor. Upon completion of innundation, the reservoir would be known as Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Management of the reservoir was transferred to the Park Service for specific purposes, including public safety, recreational use management, wildlife management, and concessions and public revenues. Effectively the total management of the area was divided between Reclamation and the Park Service, with the mission of each entity guiding the scope and application of its respective management responsibilities. [315]

As part of the Memorandum of Understanding, protection and preservation of Rainbow Bridge NM became the responsibility of the superintendent of Glen Canyon NRA. NPS Director Hartzog approved the transfer of administrative control over Rainbow Bridge to the Superintendent of Glen Canyon NRA on August 5, 1964. The recreation area operated in a legislative void for nearly a decade. Park Service personnel were assigned to administrative and recreational management of Lake Powell soon after innundation began. But in 1972, after inundation of Glen Canyon was nearly complete, Congress approved the establishment of Glen Canyon NRA. [316] With the transfer of control, Rainbow Bridge would no longer be an undeveloped Park Service unit nor would it fail to register on the appropriations radar. It became one of the best managed jewels in the national park system's Southwest crown. More progress in comprehensive management needed to be made, however, as visitation reached 12,427 by the end of 1965. [317]

During the negotiations with NPS, the Navajo Nation questioned some of the basic assumptions held by the Park Service, specifically the legal status of lands in Bridge Canyon. The negotiations moved beyond the simple need for acreage dedicated to a horse and foot trail. The creation of Lake Powell meant the Nation needed to know what type of water access to the bridge would be available. The same month the diversion tunnels closed at Glen Canyon, Assistant Regional Director Leslie P. Arnberger met with the Nation's attorney, Walter Wolf, to discuss various issues related to land exchange. They discussed draft legislation to effect a land exchange between the Nation and the Park Service. What began in the late 1950s as the need for trail access turned into a debate over commercial development. The Nation changed its position, stating it was no longer amenable to giving up land around the monument. The meeting also included initial discussions of a Memorandum of Agreement regarding recreational use and development at Lake Powell. Wolf let the Park Service know that the Navajo Nation intended to develop commercial activities to the fullest extent possible along the southern shore of Lake Powell, which was part of the Navajo reservation. When Arnberger brought up the possibility of floating dock facilities in Bridge Canyon, to be located somewhere near the bridge, Wolf made it clear that the Nation reserved the right to approve any such plans. [318]

In September 1958, Congress approved legislation that transferred certain Navajo lands to the public domain (72 Stat.1686), known as Public Law 85-868. This law contained language that the Nation and the Park Service interpreted very differently. P.L. 85-868 stated, "the rights herein transferred shall not extend to the utilization of the lands hereinafter described under the heading parcel B for public recreational facilities without the approval of the Navajo Tribal Council." The Nation contended that all the lands in question around Rainbow Bridge were Parcel B lands. This interpretation specifically allowed for Tribal approval of all recreational facilities in Parcel B lands provided that those lands lay 3,720 feet above sea level. In 1963 topographic data suggested that the proposed site of Park Service floating facilities, just north of the confluence of Bridge Creek and Aztec Creek, indeed lay above 3,720 feet. But the floating facilities would not be anchored or moored to the shore. Did Tribal approval extend to the waters that covered the Parcel B land? This was the real point of contention. The Nation argued that the innundation of various canyons near Rainbow Bridge did not change the Parcel B status of those lands. The Park Service contended that all the lands in question were part of the system of legal public access to a national monument and once submerged became subject to the same laws that regulated all the navigable waters of the United States. The Nation reasserted its position that the 1958 Act superceded Park Service intentions and made any proposed recreational use of those lands subject to Tribal approval. [319]

This was not a situation the Park Service wanted to wade through. The history of Anglo/Indian relations over land and water rights in the American Southwest was not a history that favored the Park Service. The Nation was in an advantageous position, bargaining with access to Rainbow Bridge in exchange for boat and tour concessions along Lake Powell's southern shore. The Nation advanced a revised Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) in late 1963. In the revised MOA the Nation tipped its hand in terms of what it wanted from the Park Service. The Navajo Nation retained the right to operate boat services subject to the standards of approval used by the Park Service in assessing all concessions contracts. The Nation offered unrestricted access to Rainbow Bridge via land or water and by extension released control of that access to Lake Powell. Also of importance was the Nation's willingness to transfer lands, in the form of an easement, necessary to the operation of the monument including approval to build and maintain structures or modifications designed to facilitate public access to the bridge. [320]

Despite the conciliatory tone of the Nation's revised MOA, the Park Service had much to consider in terms of permitting Navajo concessions along the south shore of Lake Powell. Contrary to the proposed MOA terms, between 1964 and 1966 the Navajo Nation grew more convinced that it would have to have permitted access to large sections of Lake Powell's southern shore for both recreational and retail development. At the same time, the Nation went through a series of leadership changes that consolidated the Nation's desire for commercial access to shore front land. These leadership changes hampered the Park Service's ability to negotiate for desired easements as the Tribal Council grew ever more wary of the Park Service's intentions. [321]

The major issue by 1966 concerned shoreline development and facilities on Aztec Creek, located one mile downstream from Rainbow Bridge. The Park Service and the Nation were trying to negotiate a land swap that granted the Park Service access to the shore along Aztec Creek in exchange for Tribal rights at Echo Camp, located just south of the Bridge. The basis for Tribal approval of facilities at Aztec Creek was in the elevation language of Public Law 85-868, as mentioned previously. Based on this law, all lands above 3,720 feet could only be developed by the Park Service with the Nation's approval. But the Park Service determined that the water level at the mouth of Aztec Creek lay below the stipulated elevation requirements. Also, the Park Service did not intend for the floating facilities to be available for use by the general public. Based on this assessment, the Park Service had installed a small floating dock facility in August of 1965. This fact did not meet with the Nation's approval. To let the Park Service know it was serious about reserving access, the Navajo Nation issued a business permit to Harold Drake that allowed Drake to develop concessions at Echo Camp. The permit was issued before any MOA was completed. In addition, the Nation solicited development support from Standard Oil Company to help develop concessions facilities at Padre Point. The latter event involved lands that were below the 3,720 foot level reserved to Park Service control in Public Law 85-868. Given Standard Oil's interest in Tribal concessions, the Nation was anxious to complete a MOA. As a result of these events, a large scale meeting was scheduled between the Park Service and the Nation to work out as many details as possible toward competing an MOA. [322]

| |

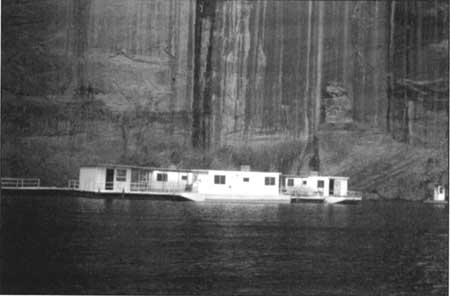

| Figure 33 Rainbow Bridge marina, 1965 (Woodrow Reiff Collection, NAU.PH.99.5.177, Cline Library, Northern Arizona University) | |

The conference was held at the Tribal headquarters at Window Rock, Arizona on January 26, 1966. Tribal representatives included Frank Carson, director of the Nation's Parks, Tourism, and Recreation Development council; Bill Lovell, Navajo Tribal attorney; and, Edward Plumber, Sam Day III, and Roger David, members of the Navajo Tribal Council. The Bureau of Indian Affairs sent seven regional representatives. The Park Service was also represented in force: Norman Herkenham and Joe Carithers from the Santa Fe Regional Headquarters; Superintendent Gustav W. Muehlenhaupt and Lyle Jamison from Glen Canyon NRA; Superintendent Meredith Guillet from Canyon de Chelly; and Superintendent Jack Williams from Navajo NM. The conference had an extensive agenda, but the majority of the issues revolved around Park Service plans to develop facilities near Rainbow Bridge and Tribal demands on access to Lake Powell's south shore. In addition to land issues at Rainbow Bridge, the Park Service and the Nation tried to work out details concerning a proposed land expansion at Navajo NM.

The conference did not go as the Park Service anticipated. Based on the stipulations of the 1958 Act, the Nation felt that the Park Service was trespassing on Tribal lands at Aztec Creek, given that the Park Service did not solicit Tribal approval to construct floating docks. The Park Service responded that this was the purpose of completing a Memorandum of Agreement—to retroactively obtain Tribal approval for necessary facilities. The Nation was willing to grant such approval but only if the Park Service agreed to grant exclusive concessions rights to the Nation at those facilities. Regarding the land exchange for Navajo NM, the Nation felt betrayed when it was informed that they would have to pay rent to operate a Navajo crafts concession at the new Betat' akin visitor's center. Tribal representatives said they had been assured that no such rent would be required. The Park Service maintained that this was always couched in terms of the Nation granting approval of the desired land expansion at Navajo NM. Tribal attorney Bill Lovell maintained an extremely diplomatic tone during the course of the heated negotiations, according to Park Service reports. Norman Herkenham said that it was Lovell's commitment to productive negotiations that prevented the conference from breaking down completely. The conference ended with both the Park Service and the Nation committed to finding mutually acceptable solutions to the issues that concerned Rainbow Bridge. During the conference, Frank Carson solicited Park Service assistance with developing his Parks and Tourism department, asking for information on Park Service boating regulations, concessioner rate schedules, and examples of concessions prospectus. Carson felt that, overall, the Nation still possessed an enormous commercial opportunity at Lake Powell and Rainbow Bridge even in the penumbra of Park Service regulations. [323]

Based on the reasonable progress made at the January conference, the Nation scheduled another meeting for March of 1966. The Park Service knew that the issue of "trespass" at Aztec Creek would figure heavily in the March meeting. Prior to the meeting, Norman Herkenham obtained the opinion of Park Service Field Solicitor Gayle Manges regarding the Park Service's interpretation of the 1958 Act. The issue was more complicated than anyone anticipated. Manges argued that based on court precedents, the waters of Lake Powell and the Colorado River were "navigable [waters] in fact" which made them "navigable in law." [324] Because the floating facilities at Aztec Creek were not permanently moored to the shore or the land below the water, those facilities were subject to the laws governing navigable waters of the United States and therefore exempt from any Tribal jurisdiction. Manges wrote:

As the Tribe is vested with only a right to approve recreation facilities built on the surface estate, either upland or lake-bed, it has no possession or title to support an action for trespass for use by the public of navigable waters over Parcel "B". It is my opinion that the United States need not obtain the permission of the Tribe in order to either locate a free-floating dock or other vessel on the navigable waters above Parcel "B" on lands in Lake Powell. [325]

The March conference produced another draft of the MOA, with most of the Nation's previous concerns over Aztec Creek still extant and unaddressed. Between 1966 and 1967, Park Service relations with the Navajo Nation deteriorated to an all time low. A series of Tribal elections in 1966 did not help matters, as the Park Service observed that the emerging Tribal Council was extremely factionalized. Most of the newer council members were very much in favor of maintaining the Nation's positions concerning concessions at Lake Powell. The Nation was distressed over the Park Service's apparent uncompromising attitude concerning Aztec Creek and Navajo NM. The Park Service was aware of the poor state of affairs and in response, assigned Superintendent John Cook at Canyon de Chelly the duties of Navajo Affairs Coordinator. The Coordinator's goal was to improve relations with the Nation and help solve the problems that plagued the MOA. [326]

By March of 1967 the Park Service was negotiating from a poor position. Various attempts to solidify an MOA were met with Tribal charges of deception and fraud. The Park Service started to reconsider its need for adding any land to Rainbow Bridge NM, maintaining the simple desire for Tribal approval of public access via Aztec Creek's floating facilities. Cook, also appointed as the Navajo Affairs Coordinator, advocated a non-aggressive posture toward the Navajo Nation. Writing to the Director, Cook said "we are going to clean our own house, stick to our word and proceed in a more professional manner utilizing our knowledge of Navajo thinking." [327] This perspective represented a genuine effort by the Park Service to negotiate with the Nation on a more qualitatively equal plane.

In this new spirit, another meeting took place between legal representatives of the Nation and Park Service Regional Director Daniel Beard. After the meeting, during which another draft of the MOA was presented and discussed, Tribal Council Chairman Raymond Nakai wrote to Beard requesting Park Service assistance in helping the Nation generate a total development plan for the Nation's shoreline interests at Lake Powell. Beard responded enthusiastically, pledging the complete support of the Park Service and its resources. [328] This spirit of cooperation continued throughout 1967. The Nation focused on two issues of concern in the next draft of the MOA. In that May 1967 draft, the Nation eliminated the Park Service's requirement that any Tribal road or facility construction be pre-approved by the Park Service. The Nation also granted itself easements that would allow Navajo-controlled floating structures along the south shore of Lake Powell. In addition, the Tribal draft proposed exclusive concessions rights along all shoreline that abutted the Navajo reservation. As a conciliatory gesture, the draft contained language that granted approval to floating facilities at Aztec Creek. The Nation only required that the Park Service give due consideration to a proposal that the Nation operate the facility on a permanent basis at some point in the future. [329]

The Park Service responded that it could not guarantee approval of a plan to transfer control to the Nation, especially if such pre-approval was a prerequisite for completing the MOA. Director George B. Hartzog offered to remove the floating facility from Aztec Creek if the Nation preferred. In a letter to Nakai, Hartzog reminded the Nation that the Park Service was in the process of generating a massive development plan for the Nation that included plans for Tribal floating facilities at Padre Point. At the same time that the Director was buffering the Park Service's position, Don Clark replaced Frank Carson as head of the Nation's Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Development Department. This was good news to the Park Service as Clark favored improved relations between the Park Service and the Navajo Nation. [330]

Under Clark's guidance, the Nation negotiated through 1968 from a different perspective, narrowing its demands at Aztec Creek and along the south shore. Late in 1968 Sam Day III replaced Clark. Day was even more commercially oriented than Clark. Under his guidance, the Tribal Council met in October 1968 at Window Rock with representatives of the Park Service, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the Bureau of Reclamation. The Window Rock conference produced a complete and mutually agreeable draft of the MOA. It was sent immediately to the Navajo Tribal Council for consideration. Unfortunately, Council Chairman Nakai rejected the draft out of hand and the council never got the chance to see it. Nakai contended that the agreement was not sufficiently favorable to the Nation and as such did not merit consideration. [331]

At another meeting in April of 1969 in the office of Regional Director Frank Kowski, Chairman Nakai and Tribal attorney William McPherson argued that the Nation should be guaranteed in the MOA the prospect of assuming control of all operations at the Aztec Creek floating facilities. Nakai also insisted that the Park Service guarantee south shore development funds for the Nation equivalent to those funds the Park Service already guaranteed to north shore development. These were two points that threatened to derail the entire MOA process that had gone on for over six years. The Park Service reacted with a touch of frustration. Kowski informed Nakai and McPherson that Navajo control of the floating facilities at Aztec Creek was not an option and non-negotiable. Under guidance from Director Hartzog, Kowski said that if an MOA was not completed soon, the Park Service would move the floating facility to another location and thereby end negotiations for a Memorandum of Agreement. The Nation, in true diplomatic fashion, responded by saying that such a decision would be the Park Service's choice and not done at the request of the Navajo Nation. Representatives of the Nation and the Park Service met nearly every month throughout 1969 to clarify details of the MOA. The fact that the Nation was facing financial difficulties (Chairman Nakai told Kowski at a June meeting that the Nation could be "broke in six years") also heightened their commitment to the MOA and the tourism revenues it could ensure. [332]

The mood on both sides of the table softened during 1969. The Navajo Nation was more concerned with maintaining Park Service support of Navajo interests at Padre Point than Rainbow Bridge. The Nation also realized that it would benefit from Park Service development support and planning as public use at Lake Powell increased. Kowski spearheaded Park Service efforts to generate as much development funding as possible for the Navajo Nation, including grants for specific development at Padre Point. On December 2, 1969 the Navajo Tribal Council passed a resolution authorizing Chairman Nakai to negotiate and complete a Memorandum of Agreement regarding Glen Canyon NRA and contingent areas. The resolution invested unilateral authority in Nakai to complete and approve the MOA on behalf of the entire Navajo Nation. [333] The following year was dedicated to finalizing details of the agreement and assuring the Nation that the Park Service would support development plans along the south shore. In addition to developing an acceptable MOA the Park Service pursued cooperative training issues with the Nation in an attempt to train potential Navajo employees at Park Service facilities for employment at both Navajo and Park Service concessions. The good will that flowed between the Nation and the Park Service paid off when the Secretary of Interior signed a Memorandum of Agreement on September 11, 1970. The agreement was made none too soon as visitation reached 39,959 by the end of 1970. [334]

There were no surprises in the agreement. The Park Service agreed to help develop and manage any and all Navajo recreational facilities located at Lake Powell and on Navajo land. The agreement specifically excluded Rainbow Bridge and its floating facilities from Navajo control; however, the power of approval of any development plans for all other Parcel "B" lands above 3,720 feet remained with the Nation. All other Lake Powell development was subject to approval by the Park Service based on the overall development plan of Glen Canyon NRA. The same approval was required of any Navajo development plans for Parcel "B" lands below 3,720 feet. The Park Service also gave first-hire preference to Tribal members who applied for work at Glen Canyon NRA and offered to "encourage and assist members of the Tribe to qualify for positions" for which they may not have previously been qualified. This included specific training programs for positions in interpretation, conservation, fire protection, search and rescue, and historical programs, all designed to make Tribal applicants better candidates for federal employment. Pertaining to Rainbow Bridge, the Park Service agreed to pursue legislation that would transfer the annual concession franchise fee (normally paid to the Park Service) to the Nation in exchange for Tribal approval of existing floating facilities and the construction of any additional future facilities. [335]

The controversy of the 1970s was not limited to relations with the Navajo Nation. The 1970 Friends of the Earth lawsuit and the subsequent 1973 ruling in favor of the Park Service had real impacts on monument management. The Court's decision did not dispute the legal imperative to protect the bridge; rather, it confirmed the Secretary of the Interior's discretionary power to determine how that protection was executed. To help determine whether or not damage was being done to the bridge, the Tenth Circuit Court mandated that the Bureau of Reclamation monitor the effects of Lake Powell on the bridge for a period of ten years. The monitoring program commenced in 1974. The Bureau of Reclamation was extremely thorough in its program. Every aspect of the bridge's behavior was monitored and analyzed. The program included surveys, photography, and geologic methods of a non destructive nature. The geologic methods included Whittemore strain gauges on the bridge's legs, measurement of Bridge Canyon's width, seismic monitoring, and laser measurement of bridge movement. The Bureau reported its findings at regular intervals and made copies of those findings available to the Park Service.

The monitoring program yielded some interesting results in the ten years it operated. The most amazing realization was that the original 1909 measurements taken by William B. Douglass were incorrect. Douglass measured the bridge's height at 309 feet and the width of the span at 278 feet. These figures were the official measurements since 1910. But Reclamation measurements, using slightly more sophisticated instruments, found the height to be only 291 feet and the span 275 feet. That the original measurements were so far from accurate was a surprise to the Bureau and the Park Service. The other result of the monitoring program that amazed everyone was the degree of regular motion exhibited by the bridge. The laser measurements revealed that the bridge could rise or fall as much as 0.38 inches from winter to summer. The Whittemore Strain Gauge recorded the displacement or movement of selected cracks as those cracks responded to the environment and stress in which they existed. Results from the Whittemore gauges revealed the same type of cyclical expansion and contraction patterns. Daily temperature changes, weather conditions, and exposure time to the sun all affected the behavior of various cracks in the same way the volumetric size and height of the bridge was affected. [336]

Whether or not the presence of water beneath the bridge contributed to the extent of this volumetric and crack variation was not part of the survey's conclusion. Whether or not moisture absorption or dehydration affected the extant structural fissures in the bridge could not be determined. Rock samples taken over the course of the program did not reveal any abnormal hydrologic effects. Thus, in 1985, the Bureau announced that Lake Powell was not contributing to any structural impairment of the bridge. Admittedly, it would have come as a major surprise if the Bureau had concluded any other way. Given the extremely short term (in geologic time) nature of the monitoring program, the Bureau's assessment was a forgone conclusion. But their efforts complied with the Court's mandate, and the bridge was found to be structurally sound.

In addition to the legal imperatives associated with managing the monument, tourism via Lake Powell began in earnest in the mid-1970s. After moving north and developing Wahweap Marina, Art Greene's Canyon Tours began running all day trips to Rainbow Bridge in the late 1960s. Demand for water access to the bridge grew as steadily as the popularity of Lake Powell among water recreation enthusiasts. By early 1975, Green was conducting half-day tours to accommodate the growing visitor demand. At the time Greene was the only licensed, official tour operator on Lake Powell. But the Park Service and all those involved at Rainbow Bridge knew that water craft tourism had permanently replaced land travel to the bridge. The growing number of visitors dictated that the monument and its environs needed careful and attentive management. By 1976 visitation reached more than 65,000 people. [337]

With a Memorandum of Agreement completed, the Park Service and Navajo Nation set about identifying potential development locations on Lake Powell's south shore. But the issues related to access and use of Rainbow Bridge were far from resolved. During the 1970s the Park Service personnel at Rainbow Bridge and elsewhere were consumed by the legal battle that erupted over Navajo First Amendment claims regarding unfettered access to the bridge. The Memorandum of Agreement had only been in effect for three years when Lamar Badoni filed suit against the Park Service and the Department of Interior over the effects of Lake Powell on Navajo religious practices (see Chapter 4). The Park Service response, once the legal conflict subsided, was to generate the Native American Relationships Policy (NARP). The NARP was precipitated by passage of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 (P.L. 95-341). The policy's intent was to make the Park Service more sensitive and responsive to the cross-cultural makeup of the region surrounding Rainbow Bridge. Managing the monument in terms of cultural diversity, as well as increasing visitation, was the tenor of Park Service administration in the 1980s. Working from the existing management guidelines, the Park Service modified the Statement For Management for Rainbow Bridge NM several times during the 1980s. Eventually the Park Service personnel at Glen Canyon and Rainbow Bridge under Superintendent John Lancaster realized that a new plan had to be drafted. Continual modification of existing guidelines was simply not keeping pace with the management demands at the bridge.

As relations with the Navajo Nation warmed throughout the 1980s, the Park Service began considering a large-scale management plan for the monument. Visitation as a result of improved monument access via the Lake Powell corridor increased exponentially in the 1980s. In 1979 the Park Service tallied 97,066 monument visitors. By 1985 that number increased to 177,971 visitors. The Park Service knew that a General Management Plan (GMP) was the next logical step in the administrative and development planning of the monument. The GMP was in regular use at other units of the national park system. It was a relatively standardized document that made use of local resources and perspectives in pursuit of a cogent management plan. In the case of Rainbow Bridge, special concern had to paid to the Native American interests in the region as well as the special visitation problems presented by the limited geographic access vis-a-vis Bridge Canyon. Developing a modern general management plan (GMP) for Rainbow Bridge meant including cultural, natural, and human resources that were unused previously. One of the most significant considerations for Park Service personnel was including the viewpoints of local Navajos and Paiutes in the GMP's development. Interviews with Tribal members began in 1988. At the same time, interviews were undertaken by Pauline Wilson, American Indian Liaison for Glen Canyon NRA, to determine the scope of Navajo religious affinity at Rainbow Bridge. In 1989 the Park Service solicited public opinion at large, generating a questionnaire for visitors to the bridge and establishing a comment register where people could relate their views on improving and managing the monument. In 1989 visitation to the monument reached 238,307. The Park Service knew that it could not keep pace with growing visitor needs and demands without a comprehensive management strategy. [338]

In 1990, Glen Canyon NRA personnel, under the direction of Pauline Wilson, Environmental Specialist Jim Holland, and Public Affairs Officer Karen Whitney, continued to conduct meetings at Navajo chapter houses to gauge Navajo opinion of the proposed GMP. Holland related at each of the meetings that the Park Service had a number of specific goals attached to the GMP: preserving Rainbow Bridge for future generations; identifying and protecting the cultural significance of the bridge to Navajo and other cultures; and maintaining a productive relationship with the Navajo Nation. It was obvious that the cultural imperatives born of the legislative and judicial events of the 1970s and 1980s were not lost on Park Service personnel at Rainbow Bridge. Despite the previous conflicts between the Park Service and the Navajo Nation, the Park Service was committed to improving that relationship via a culturally sensitive GMP for the bridge. By September 1990 the Park Service had created a Draft GMP that could be reviewed by the public. That review process began in earnest among the Navajo Nation in October 1990. [339]

The initial concerns for the GMP revolved around managing the growing population of visitors to the bridge. Visitation had increased substantially every year since the availability of water access via Lake Powell. The effects of that increased visitation were obvious: graffiti, refuse, human waste, and off-trail damage were all evident. Phase I and Phase II initiatives in the draft GMP limited the number of people at one time (PAOT) at the bridge to about four hundred. The Park Service also proposed that NPS interpreters be on each tour boat headed to the bridge to provide information regarding the sensitivity of the bridge's ecosystem and the need to protect both natural and cultural resources. The draft GMP also advocated a seasonal contact station in Forbidding Canyon to collect entrance fees and regulate traffic to the bridge, interpreters at the bridge, and other contact stations. The plan's intent was to protect the area's diverse resources through increased contact with visitors. While no regulation prohibiting physical access to the bridge was proposed, the hope was that visitors would voluntarily comply with protective goals if a proper level of information was made available. The Park Service, in subsequent drafts of the GMP, never advocated statutory enforcement of provisions to prevent visitors from approaching the bridge. [340]

The idea of limiting numeric access to sensitive areas was not new in the Park Service or within the national park system. Zion National Park in Utah had been limiting the number of hikers in The Narrows section of the park to 70 people per day since approximately 1988. [341] The reasons at Zion were echoed at Rainbow Bridge—limitations were necessary for both public safety and resource protection. Regardless of the cultural implications to a given group, the Park Service had always made preservation one of its top priorities in sensitive areas. The draft GMP also advocated a permit and fee scenario for bridge visitors, much like other parks and monuments had in place for their more delicate zones. Needless to say, the draft GMP ignited a controversy. Navajos wanted unfettered and non-permitted access based on their long-held religious beliefs about the bridge. The public comments were divided. Some respondents favored no controls of any kind, while some favored even stricter controls on access to the bridge. A few wondered why the Park Service was involved in any way at Rainbow Bridge. The Park Service, via Pauline Wilson, solicited local Navajo input on the GMP through 1992. [342]

In 1993, after soliciting extensive public opinion, the Park Service produced a final draft of the General Management Plan. The final GMP included plans covering development concepts and resource management, an interpretive prospectus, and an environmental assessment. It was the most comprehensive look at managing Rainbow Bridge NM ever produced by the Park Service. It was an extremely timely document. With most of the litigation concerning the bridge behind it, the Park Service could focus on tangible management problems such as graffiti, boat traffic in Bridge Canyon, waste disposal, and foot traffic at and under the bridge. Many of these concerns reached their apex by 1993, as visitation to the Bridge exceeded 250,000 the prior year. The GMP zeroed in on the most pressing concerns at the monument: carrying capacity, resource management (cultural and natural), and use definition. [343]

One of the more controversial elements of the GMP was its determinations on carrying capacity. There really had not been any limits to visitation before the 1990s. While certain references in various Park Service memoranda indicate that the Park Service hoped visitation and impacts could be limited, little administrative action was taken prior to formulating a GMP. Based on a survey of the resources at Bridge Canyon and the canyon dock facility, the GMP determined the maximum PAOT should not exceed three hundred and ninety. The plan also called for a fee for access to the monument. The carrying capacity was to be evenly divided between private boats and tour boats. The contact station also provided for concerns about human waste, trash, and prevention of unacceptable activity at the bridge via Park Service enforcement. One of the most revolutionary ideas in the GMP, designed to mitigate individual impact on the monument, involved transferring private individuals from their boats to Park Service boats to ferry those individuals to the bridge. No boat traffic would be allowed past the contact station unless there was room at the monument. Using Park Service-operated transportation would have been unique at Rainbow Bridge but is now employed in numerous units of the national park system including Zion and Yosemite. Ultimately the desire of the Park Service to regulate access to Bridge Canyon took the form of employing concessionaire tour boats and limits on their maximum passenger allowances. But the GMP did represent the Park Service's desire for hands-on management at Rainbow Bridge. [344] Employing the carrying capacity formula proposed by the GMP, Rainbow Bridge could be seen by more people with less trouble and more control.

In terms of handling cultural resource issues, the GMP was not the only tool in use in the early 1990s. In addition to soliciting public and Native American opinion of the GMP, the Park Service's Resource Management Division at Glen Canyon entered into a cooperative agreement with Northern Arizona University (NAU) to study the ethnography of the Rainbow Bridge region. In 1991, Dr. Robert T. Trotter, II was assigned as principal investigator for the project with Neita V. Carr acting as the primary researcher and writer. The study was designed to provide a general overview of contemporary Native Americans who were associated with Glen Canyon and Rainbow Bridge and to define the cultural and natural resources under Park Service management that those tribes valued and used. Carr and Trotter generated a basic summary of the use patterns and affiliations of both Hopi and Navajos at Rainbow Bridge. That information is presented in greater detail in Chapters 2 and 5 of this administrative history.

What the ethnographic overview and assessment did confirm was the desire of the tribes to be more directly involved in the decision-making process at Rainbow Bridge. Every tribe that expressed cultural and historical affiliation with the bridge and its environs also indicated that their interests should be part of the criteria that underpinned management at the bridge. The ethnographic overview was a big step toward realizing comprehensive management at the monument. That goal was broadly defined in the Cultural Resources Management Technical Supplement, published by the Park Service, in August 1985. The summary of Carr and Trotter's report was that the Park Service needed to continue its efforts at ethnographic study and expand them to include other Native American groups, such as the San Juan Southern Paiute and Hopi Tribe. The report made general recommendations toward field studies, resource analysis, and the creation of a large-scale ethnographic data base that would be available to Park Service personnel for help in decisions that might affect affiliated tribes. Carr and Trotter observed, "it is clear from the literature search and our cultural consultation that multiple field studies are both desirable and necessary to create [an] appropriate data base and to provide a stable condition for relations with [Glen Canyon] and [Rainbow Bridge] associated peoples." In various forms, these suggestions were followed by the Park Service. The ethnographic overview, completed in March 1992, was definitely an influence on the final draft of General Management Plan, the creation of a Native American Consultation Committee, and eventually the Comprehensive Interpretive Plan. [345]

The public comment period for the GMP continued through 1992, with revised drafts being made available to Navajo, Hopi, and Paiute Tribal representatives. Pauline Wilson continued to take drafts to the Navajo and Paiute chapter houses for public comment and the results of the NAU ethnographic study were used to modify the parameters of interpretation toward maximum sensitivity to all affiliated Native Americans. The Park Service generated the final draft of the GMP in June 1993. It reflected much of the public comment that was gathered by the Park Service during the previous three years. In terms of the issue of carrying capacity, the final plan was radically different from its various drafts. It called for a maximum of 200 PAOT, with 150 allotted to tour boats and the remaining 50 to private boats. The docks would be reduced in length to accommodate the modified carrying capacity and a ranger would staff the exit point on the docks to ensure compliance with the carrying capacity limits. While this did not sit well with ARAMARK, the Lake Powell concessioner, the plan's focus was minimizing impact rather than maximizing revenue. Because of increased visitation over the years, the environs of Rainbow Bridge suffered a severe toll; the Park Service was dedicated to restoring the monument as much as was feasible. [346]

Protection of natural resources and processes in the monument was also a focus of the final GMP. Tamarisk, an exotic and non-native tree species, had been spreading rapidly near the bridge. It was long considered a threat to surrounding vegetation and to developing riparian communities. The GMP authorized the removal of tamarisk from the viewing area and near the bridge. Off-trail travel was forbidden in the new management strategy. The amount of cryptogamic soil damage was hard to measure, but it was extensive. The GMP also called for revegetation of impacted plant species and discouraging visitation beyond the assigned viewing area. Cultural resources also formed the object of intense management in the final GMP. Restricting certain access to the bridge in the form of petroglyph and archeological site protection was to be accomplished through increased Park Service presence and mandated trail boundaries. While nothing in the GMP provided for restricting access to the bridge (there were no mandates to stop visitors from approaching or walking under the bridge), the plan did seek to "discourage" visitor use below the bridge. The effects of these decisions would be monitored through visitor-use surveys and Park Service/visitor contact. It should be made clear, however, that the GMP never advocated that visitors be prevented in any way from approaching or going under the bridge. [347]

The GMP also contained a fifteen-page interpretive plan. Based on research done by NAU and the collective response from Anglo and Native American groups over the significance of the bridge, the Park Service developed an interpretive framework to facilitate and enhance the visitor experience at the bridge. The GMP made its purpose plain, stating, "the significance of Rainbow Bridge lies not only in its geological character, but in its power to move and inspire the human soul. For Navajo, Hopi, and other native peoples it is part of who they are and what they consider sacred and meaningful in this life." [348] The GMP acknowledged that the bridge occupies esoteric importance to other worldviews. In order to be fair to those peoples with a worldview that was not Anglo, the GMP advocated administering the monument in such a way that both worldviews were represented. In essence, the GMP took a non-Anglocentric vector and suggested that the Anglo interpretation of the history of the bridge was not the only acceptable interpretation but rather one of many. It is important to remember that this portion of the GMP was generated in a spirit of cooperation and diversity and not as a result of harassment or litigation. When all was said and done the Park Service recognized its responsibility to incorporate alternative worldviews into the Rainbow Bridge interpretive experience.

The interpretive goals for the monument were categorized around multiple resources. The GMP recognized the importance of prehistoric, historic, ethnographic, and natural resources. Since the monument barely measured 160 acres and visitation was averaging over 250,000 people per annum, the Park Service realized it had to act aggressively to preserve the resources at Rainbow Bridge. Native American groups were to be utilized in a consultation capacity regarding information that should be passed on to visitors (in the form of Native American historical beliefs about the bridge) and regarding the appropriate level of contact between visitors and the bridge itself. The Park Service did not advocate that its personnel prevent visitors from approaching the bridge; rather, rangers and interpreters sought visitors' voluntary deference to Native American requests that the bridge remain free from direct human contact. In July 2000, Stephanie Dubois, Chief of Interpretation for Glen Canyon NRA, stated in an interview that no visitor had ever been cited for approaching the bridge on designated trails or for walking beneath the bridge. Chief Dubois also indicated that there was no Service policy to prevent or dissuade any visitor from approaching the bridge once the visitor has made the decision to leave the congregating area. Visitors are only cited if they violate the published restrictions on activities related to swimming, fishing, or entering closed or revegetating areas. [349] The interpretive outline of the GMP recognized the potential for conflict with Anglo belief systems, stating that there would be "other concerns that will surface, which affect interpretation at the monument. To be sensitive to the values and experiences of other people, to bridge the cultural gap, will be the challenge to interpretive managers." [350] Indeed, this is still the goal of managers in the 21st century.

The GMP settled on five major interpretive themes: that geological processes formed Rainbow Bridge; that Rainbow Bridge is part of the greater Colorado Plateau ecosystem; that people interacted with the bridge in prehistoric times; that people interacted with the bridge in historic times; and, that people continue to impact the monument. The Park Service made each of these themes a part of the interpretive goal for each Park Service interpreter working in and around the monument. The GMP also recommended that Park Service interpreters be part of each ARAMARK boat tour entering the monument, ensuring a maximum level of Park Service/visitor contact. [351] The GMP also called for interpreters to be stationed on a rotating basis at the monument to greet visitors and help enhance the Rainbow Bridge experience. No single cultural viewpoint was ever emphasized over the other defined thematic goals; rather, the cultural significance of the bridge to both Anglos and Native Americans was added to the larger interpretive matrix. Signs, exhibits, Park Service interpreters, revised access restrictions based on environmental concerns, and updated brochures all formed the core of making the interpretive experience both comprehensive and widespread. [352]

The signage that was part of the GMP wayside exhibit plan was to become one of the more contentious issues at Rainbow Bridge in 1990s. Signs seem to have taken on a peculiar significance to Americans, especially those signs that concerned religion or spirituality. The GMP allowed for one sign to be placed near the congregating area, which tried to inform the public that Rainbow Bridge was considered sacred to Navajos and other Native Americans. The wording of the sign was a major concern to the Park Service. But the GMP-authorized sign was not the first to define Rainbow Bridge's place in Native American spirituality. Located in the interpretation archives at Glen Canyon NRA headquarters is a photograph of a sign that was in place at Rainbow Bridge in the late 1980s. The sign read:

There are places mentioned in Navajo legends which are said to be sacred. Rainbow Bridge is one thought to possess supernatural powers.

According to one Navajo legend, the Diné (Navajo People) once believed that harm would befall anyone who walked beneath Rainbow Bridge without first chanting a prayer of protection. Over the years the prayer was forgotten and the Diné would no longer enter the area.

Today you are about to approach this special place. Do so with reverence, for it is said: "Those who pause to rest within the shadow of the bridge will leave their troubles behind."

Investigation by Park Service personnel at the Harpers Ferry Center in West Virginia produced no clues as to the sign's origin. The Wayside Exhibits division at Harpers Ferry Center only had record of two signs constructed for Rainbow Bridge NM. Those signs dealt with the "discovery" of the bridge and the geologic formation of the bridge. Presumably this sign was placed at the bridge on the heels of the 1980 Badoni decision and the passage of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act in 1978. The signs may also have been placed after the Department of the Interior released the Native American Relationships Policy in February 1982. [353] Regardless, the mood of both the Park Service and public between 1980 and 1993 was one of conciliation. The reaction of the public and the Park Service to renewed Native American concerns over appropriate use and interpretation of Rainbow Bridge after 1995 is the subject of Chapter 8.

The GMP represented the culmination of the Park Service's efforts toward effective management of the monument. After lengthy solicitation of numerous opinions and viewpoints, the Park Service produced a plan that would manage the monument in terms of resources rather than profits. The Park Service's decision to limit ARAMARK's tour boat access to 150 PAOT, instead of 150 people per boat as ARAMARK wanted, was a testament to the Park Service's ability to manage beyond the traditional scope of visitor demands. Ensuring the longevity of Rainbow Bridge and its environs for as many generations of visitors as possible was the mission of the new GMP and the Park Service after 1993. Undoubtedly the Park Service would not escape criticism. Anglo proponents for unrestricted and secular access to Rainbow Bridge would criticize the Park Service for its cultural sensitivity. Certain Native Americans favored days dedicated to segregated Indian access to the bridge and so would criticize the Park Service and the GMP for not going far enough. Regardless, the period between 1955 and 1993 was one of major growth for the Park Service at Rainbow Bridge. The staff had managed the monument through national swings in political mood, through the Colorado River Storage Project and the creation of Lake Powell, and took ever more aggressive management action as visitation increased from 1,081 in 1955 to 256,158 in 1992. Keeping pace with these changes was not an easy task. The Park Service approach to managing Rainbow Bridge NM, as described in Chapter 8, was one of flexibility and willingness coupled with a firm commitment to managing the monument in terms of resource protection versus income maximization.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

rabr/adhi/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 31-Aug-2016