|

National Park Service

Recreational Use of Land in the United States |

|

SECTION I. LAND USE AND RECREATION

1. ORIENTATION

The Problem

In the general program of the National Resources Board the National Park Service has been assigned the section which deals with recreational use of land. This has been interpreted to mean recreational use of land and water, since the two are actually inseparable.

The quest of the present report is not only for that recreational vein which flows abundantly through our national resources, but for the most effective means of tapping that vein. Shall it be in the easy and casual "water-witching" method, or shall it be a planned attack? Certainly, the real, human need for abundant and varied recreation, and the long-established value of a planned campaign, dictate that our method should be the latter. In other words, our recreational resources are to be considered in this report as national resources, to be found and developed under a national plan. Therefore, recreational use of land in the United States must be coordinated with other forms of land use.

To correct any misconception that a national plan for utilizing our national recreational resources would imply inhibition of individual choice of such values, it should be stated at the outset that the very essence of recreation involves an element of individual choice or freedom.

Recreation, as used in this report, connotes all that is recreative of the individual, the community, or the Nation. In this sense it is broader than the "physical activity" concept. It includes mental and spiritual expression. It allows gratification of the nearly infinite variety of tastes and predilections so far as that gratification is consistent with sustained utilization of the Nation's recreational resources.

A specific example of this broader concept is given by Lovejoy.

* * * the backbone of "outdoor recreation" is the production and direct or indirect utilization of 'wildlife.' In the past this has usually meant hunting or fishing facilities, but in he modern and wider sense includes the aesthetic as well; the chance to see a deer as well as the chance to shoot one; the chance to photograph a beaver lodge as well as to wear a fur collar; the chance to observe arbutus peeping through the snow-packed leaves, as well as to buy bunches of the naked flowers from a car window; the chance to wander down aisles carpeted with soft brown pine needles and to listen to the sighing of the zephyrs in the boughs, as well as to buy lumber.1

1 Lovejoy, P. S., Concepts and Contours in Land Utilization (in Journal of Forestry, vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 381-391. See p. 388, April 1933).

National resources of recreational value may be found almost anywhere, and a national plan for utilizing them must include their conservation for recreational use. The conservation of any large national resource involves land-use planning of national scope. For example, recreation may be found in the conventionalized social routine of the popular summer resort, or it may be found in the solitude of the wilderness. Facilities for the former are commonly supplied. Suitable areas for the latter must be reserved before all have disappeared. They must be of sufficient extent to give complete satisfaction.

It is the purpose of this report to disentangle some of the conflicting and inhibiting views which have prevented national recreational resources from being used, and to present a plan for coordinating their use with other land uses.

This means that the recreational function of the various forms of land use must be analyzed, evaluated in relation to the other functions, and provided for by the various administrative organizations of the Nation according to their particular capacities and responsibilities.

The continental United States contains 1,903,000,000 acres of land. Of this, approximately one-half is physically adapted to the production of harvested farm crops for food, clothing, etc. Progressive developments in agricultural technique hold out the promise that from this one-half of the total land area, plus limited pasturage of parts of the other half, the needs of the prospective population of the United States for food, wearing apparel, and export commodities, etc., can be met for an indefinite period.

This primary and dominant fact raises sharply the question of the future economic and social destiny of the remaining half of the land area of the 48 States. It is not needed for farm-crop production. Our cultivated area needs contraction, not expansion, and attempts to use such lands for that purpose will entail expenditures of capital and human effort far disproportionate to the average returns obtainable. On the other hand, the abandonment of such lands, the cessation of all organized and systematic protection against deterioration and destruction, would set in motion a process of slow attrition which, over the years, would markedly impair one of the Nation's basic resources, its soil capital.

The fact that one-hall of the land area of the 48 States is poorly adapted to and not needed for farm-crop production does not mean that it is lacking in potentialities for social and economic services. On the contrary it is rich in such potentialities, which readily can be realized by systematic determination of the kinds of economic or social service to which specific types of areas of land are best adapted, and by the gradual adjustment of the use of such lands, through voluntary private action or legislatively authorized public action, to the forms of service so determined.

It is evident, for example, that a balanced economy and sound program of industrial and social organization will require that adequate supplies of timber be permanently available to meet national needs, and shall be so distributed regionally as to maintain a proper balance between regional production and consumption. To this end, a large proportion of the available area should permanently be dedicated to forestry.

Another need of large dimensions is that of provision for the scientific, educational, and recreational requirements of a population steadily growing not only in numbers, but in cultural standards; a need made progressively acute and important by the increase in leisure time and the growing intensity of metropolitan existence. To satisfy these needs an adequate part of the territory not required to feed or clothe the Nation or to furnish products for export should be dedicated to public service as parks, monuments, recreational areas, playgrounds, etc.

As time goes on, the great social, scientific, educational, and economic potentialities of the wildlife resources of the Nation gain enlarged recognition. Their conservation, development, and augmentation are dictated by all considerations of public interest and welfare, and the dedication to that purpose of large areas of available lands through their permanent establishment as wildlife refuges or sanctuaries, with certain related areas for public shooting grounds, would be good public economy, productive of a high type and return of social and economic service.2

2 U. S. Department of Agriculture, National Land Use Planning Committee First Annual Report, Publication No. V, Washington, D. C., July 1913. See pp. 12—13.

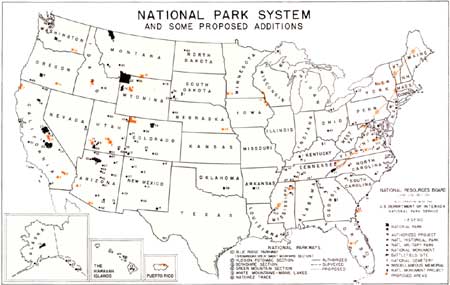

FIGURE 1.

Discussion of Terms

The rapidly growing interest in recreation in America during the past 30 years has given rise to the frequent use of many words and terms not always clearly defined as to their functional meaning.

Because of this confusion, a few terms are defined here, since it is desirable that the reader know what meanings these terms have, as used in this report.

Outstanding among these words are "leisure", "recreation", and "conservation".

Other words and terms in common usage relate to specific land and water areas used for recreation, the most common of which is "park." Others relate to types of recreational facilities, and still others to types of activities, administration, and personnel.

Leisure.—Leisure is that segment of time in the life of any individual, separate and apart from time spent as necessary for his personal care, sleep, and securing the necessities of life for himself and those dependent upon him, and the accumulation of surplus wealth.

Leisure connotes freedom to act at will, while other forms of time consumption involve certain elements of compulsion, either real or imaginary.

Recreation.—Recreation is the creative use of leisure.

It takes many forms expressive of needs, desires, qualities, powers, interests, and instincts of individuals. In character, it may be passive, as in complete rest and relaxation without action; semiactive or mildly active, as in listening to music, viewing works of art or a beautiful landscape, strolling, reading for pleasure, attending a dramatic performance, witnessing sports and games, taking part in quiet conversation; active, as in participating in sports and games, swimming, rowing, hiking, riding, fishing, hunting, camping, playing a musical instrument or singing, acting in a play, painting a picture, studying for self-improvement, traveling, gardening, engaging in various kinds of handicraft arts, dancing, taking part in civic, political, or social activities, writing, public speaking, or debating. In quality, recreation always involves the idea of freedom of choice and freedom of action. It has the further quality of bringing immediate personal satisfaction or happiness. Recreation is an end in itself; it may have and usually does have far-reaching beneficial results, both individual and social.3

3 "Recreation is any pleasurable activity of mind or body which is stimulating and refreshing, and which is entered into without compulsion or expectation of material gain. It is a form of wish fulfillment and is usually associated with leisure." Lee F. Hammer, Russell Sage Foundation, New York, Letter Aug. 17, 1934.

Conservation.—Conservation is the wise use of natural resources.

The conservation of any natural resource requires first that the resource be dedicated to the highest uses for which it is suited. The second requirement is for immediate protection against all influences adverse to this highest use. Then comes determination of the question as to whether the public interest will be best served by immediate or deferred utilization of the resource. If use is to be immediate, then a plan of development must be invoked which will perpetuate or possibly even increase the resource for the type of utilization to which it is dedicated. If the highest use of a natural resource is to be found in the perpetuation of its primeval condition, any or all developments which lessen this primeval condition are destructive of that resource.

Types of Recreational Areas

Park.—A park is an area set aside for recreation, especially characterized by landscape either natural or designed.

It functions recreationally as a retreat for the people for rest, relaxation, and inspiration, in an environment of quietness and natural beauty, and for such activities as do not essentially conflict with the character of a naturalistic landscape.

Playground.—A playground is an area designated and used primarily for the play of children.

Such areas are sometimes divided into three types: (1) The kindergarten playground for children under 5 or 6 years of age; (2) small children's playground for children from 6 to 10 years of age; (3) neighborhood playground designed for the use of children of all ages up to 15 years.

Auxiliary use: The neighborhood playground may have and usually does have an auxiliary recreational use for youths and adults.

Administrative authorities: Playgrounds are types of areas most commonly provided in municipal recreational systems and in connection within educational systems. They are, however, frequently provided in county and metropolitan recreational systems.

Playfield.—A playfield is an area designated for the sports and games of young people and adults.

Auxiliary use: A playfield area may include a children's playground.

Administrative authorities: Playfields are most commonly provided in municipal, county, and metropolitan recreational systems. They are likewise common in educational systems, and occasionally appear in State recreational areas.

Athletic Field.—An athletic field is all area designed for highly organized, competitive games and sports of youths and adults.

Attendance at athletic fields is usually subject to a fee, the design including provisions for track and field sports, competitive, highly organized games, seating for spectators, and field house, the entire area being enclosed with a wall-like fence.

Administrative authorities: Athletic fields are most commonly parts of municipal recreational systems and school systems, but are also occasionally found in county and metropolitan recreational systems.

Recreation Center.—A recreation center is an area designed and equipped for a wide variety of outdoor and indoor recreational activities for children, youths, and adults.

The design for such an area includes a children's playground, outdoor games and sports facilities for young people and adults, outdoor or indoor swimming pool, and a recreation building or community house equipped for social, civic, cultural, and physical activities.

Administrative authorities: Such areas are most commonly parts of municipal recreational systems, but are also occasionally provided in county systems. In many modern public schools systems may be found such a combination of an area and a building as would qualify as a recreation center.

Neighborhood or "Intown" Park.—A neighborhood or "intown" park is a recreational area designed according to the principles of landscape architecture primarily for adornment of the neighborhood in which it is located and as a place for relaxation for the inhabitants living near it.

In size, such an area may range from 2 or 3 acres to 20 or 30 or even more acres.

Comment: The neighborhood or "intown" park is the modern descendant of the "commons", "plazas", "squares", of the colonial towns and cities.

Auxiliary uses: It is not uncommon to use such parks for the play of very little children, conducting of concerts, dramatic performances, socials, neighborhood civic celebrations, and other public gatherings.

Administrative authorities: This type of park is most commonly found in municipal recreational systems, but appears occasionally in county and metropolitan systems.

Large Recreational Park.—A large recreational park is an area ranging from several hundred to several thousand acres, designed and constructed according to those principles of landscape architecture known as the "naturalistic", preserving and presenting a varied naturalistic landscape, and primarily intended as a retreat for the people for relaxation, inspiration, and enjoyment of the beauties of nature, and renewal of contact with the soil and growing things; as an escape from the crowding, sights, and sounds of the city; and for such active recreations as fit harmoniously into a naturalistic landscape.

Comment: These large recreational areas have become commonly subjected to uses not in harmony with their primary purposes or character, such as being utilized to an excessive degree as sites for playfields athletic fields, stadia, or swimming pools—a practice that unfortunately is likely to continue.

Administrative authorities: This type of park is most commonly associated with municipal recreational systems but it also appears in county and metropolitan recreational systems in those situations where such systems exist under practically urban conditions.

Parkway.—A parkway is an elongated, naturalistic, landscaped, recreational area comprising as its prominent features a pleasure driveway with a bridle path and hiking trail through its entire length, not always but often connecting two or more large recreational areas of park character.

Auxiliary uses: The areas along a parkway road frequently present opportunities for various forms of passive recreations and for such active recreations as picnicking, hiking, riding, bicycling, playing of games in open meadows; and swimming, boating, skating, and canoeing, if the topography includes a stream.

Administrative authorities: Parkways are features of municipal, county, metropolitan, State, and national recreational systems.

Stream. Easement.—A stream easement is an area along the bank or banks of a stream leased for a special period of time by some public agency for the purpose of allowing the public free access to the waters of a privately owned stream for fishing.

Administrative authorities: Such easement areas are administered at the present time (1934) exclusively by State agencies.

Great Pond.—A great pond is an area of natural water of 10 acres or more to which the public has a right of free access for fishing and fowling subject to Federal-State laws regulating fishing and fowling.

Types of Wildlife Reservations

Since the various forms of wildlife utilization provide different types of recreation, and since these different types of recreation frequently demand conflicting uses within a single wildlife area, it is desirable to define types of wildlife areas according to their uses.

Wildlife Sanctuary.—A wildlife sanctuary is an area set aside and maintained for the inviolate protection of all of its biota.

This is the type of area which is set aside for the pleasure of seeing and studying the biota, and is not subject to hunting, trapping, or any other commercial utilization. Whether or not the biota of the sanctuary produces a surplus which is harvested outside the boundaries of the sanctuary is incidental when compared with its main objective—protection.

Refuge.—A refuge is an area wherein protection is accorded to selected species of animal life.

Refuges are established for either game (game refuge) or nongame animals (i. e., pelican refuge) or in some cases both, but they involve the protection of the selected species for some particular purpose, whether that purpose is a matter of aesthetics, scientific investigation, hunting, or commerce. Other forums of animal life predatory upon or adversely affecting time selected forums within the refuge might be controlled.

Preserve.—A preserve is an area set aside and maintained for the production and/or harvesting of wild animal life on a sustained yield basis.

Wildlife Preserve is an area set aside and maintained for the production and harvesting of any or all forms of the native biota on a sustained yield basis.

A Game Preserve is an area set aside. and maintained for the production and harvesting, or harvesting only, of game animals.

2. SUMMARY

Recreational Resources

The desire of the American people for the kinds of recreation that lands of various types may provide is a natural and legitimate one. It amply justifies public agencies, Federal, State, and local, in assigning lands to recreational use. That this desire is universally prevalent needs no argument—it has been conceded for a long time.

The history of the public recreational use of lands in the United States dates back to the town commons, squares, plazas, and great ponds of colonial times. Though town planners did not give much thought to recreational areas following the close of the colonial period, the movement has gained great impetus since the middle of the last century. New York took the initiative by establishing Central Park, and the Federal Government entered the picture when Yellowstone National Park was created. Today magnificent park systems of certain cities and States conclusively demonstrate both the desires of communities and the attainment of these desires. In their fulfillment is indicated in large measure the cultural achievements and standings of the respective communities.

Social and economic trends indicate a greater need for recreation, and there is a strong and growing tendency toward universal appreciation and understanding of outdoor recreational values. This is well exemplified in the rising protest against the continuing destruction of the Nation's few remaining wildernesses. The trend is in the direction of a great variety of new uses of land and is fulfilling the high motives of those who originally made recreational areas possible.

Since the recreational use of land does not stop with physical rehabilitation, but, in addition, stimulates invigorating mental exercise and cultivates salutary mental dispositions, the possession of which may be determining factors in the quality of life in the community, State, and Nation, it is vital that recreational resources be protected and developed.

It is this broader aspect of public policy which has actuated the Federal, State, and local recreation agencies, while fulfilling their duties as preservers, to render the possessions in their custody enjoyable and culturally profitable to the public. This has resulted in the provision of educational staffs, museums, road and trailside exhibits, and a wealth of informative literature—high attainments in rendering recreational resources culturally profitable and enjoyable.

Editor's Note: since citations for data quoted in this summary section are given the expanded text, they are not repeated here.

The recreational desires of a progressive people, however, are not and cannot be satisfied with what a single governmental agency may provide and administer. A citizen may find congenial recreation in the inspection of various governmental projects and activities. One visitor may stand spellbound at the brink of a canyon, while another enjoys equivalent emotions when looking down upon some huge engineering project.

It seems that the time has come when the concept of our national recreational resources can no longer be limited solely to certain prescribed areas specifically and primarily devoted to recreational use. It must instead, as far as is practicable, comprehend all those resources of the country as a whole which are susceptible of use for recreation. In this concept, lands held as public parks or monuments appear as a subdivision, though a highly important one, of the vast lands which, in greater or lesser degree, can and will contribute recreational satisfaction. Furthermore, if the fullest recreational usefulness is to be derived from these resources, information concerning them should be widely disseminated.

It has been with such a concept in mind that the Federal Government has carried forward its task. Impressed though it has been with the importance of the service which it should render in the field of recreation, it also has been keenly aware that, if recreational lands are to be considered from the standpoint of the total number of persons who use them, and the frequency of their use, then the focal point and the foundation of a national recreational program is within the numerous municipalities and their immediate environs. It is there that the need for publicly provided facilities is greatest, and it is there alone that frequent use, by all for whom these facilities are designed, is actually possible. No other recreational system can possibly be laid out on a basis of such frequency or universality of use.

The users of the recreational facilities to be provided by the States, incomplete though the State systems be, are several times as numerous as the users of the far-flung areas owned by the Federal Government. Upon the States rests the responsibility for acquiring and conserving examples of the native landscape which deserve protection, but which lie outside the field either of the Nation or of the municipalities, as well as places which possess similar distinction because of historic, prehistoric, or scientific features. Every reasonable encouragement and cooperation needs to be given them by the Federal Government in order that they may occupy satisfactorily the place in the national recreational scheme which is properly theirs.

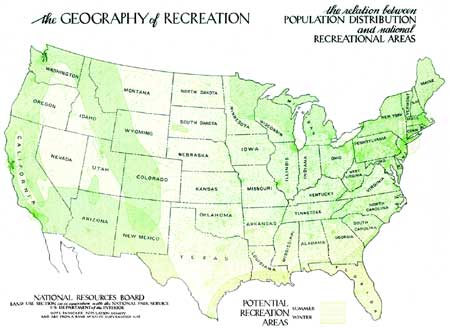

FIGURE 2.

Recreational Needs of the People

Man is essentially an outdoor animal as far as his biological and physiological needs are concerned. The supplying of means for the satisfaction of these needs among a highly urbanized people is one of the fundamental reasons for the reservation of lands and waters for recreational use. It is one of the laws of the growth of human beings that there is required a considerable measure of activity in forms expressive of age-old urges, impulses, and instincts. Juvenile and youth delinquency, and other antisocial expressions are, without question, partly the result of society's failure to recognize this principle.

Population in the United States increased from 4,000,000 in 1790 to 123,000,000 in 1930, but the rate of increase has been declining since 1860. The trend indicates that growth of the population in the future will be small, the estimate for 1980 being 170,000,000. The total birth rate has been falling steadily, which means that the proportion of older people in the population is growing larger. This trend has been accentuated by a steady decline of the death rate. Present indications are that the proportions of native whites will increase faster than Negroes, and that the proportion of foreign-born whites will decline.

Population is distributed very unevenly throughout the United States, as is well illustrated by the fact that the Mountain division has 3 percent of the population and 28 percent of the total land area, whereas the New England, Middle Atlantic, and East North Central divisions, comprising only a little more than 13.7 percent of the total land area, have almost 48.7 percent of the total population. Study of population distribution is helpful in revealing where particular attention should be given to reserving lands and waters, if the people are to have adequate and frequent opportunities for outdoor recreation.

Recent trends in urban and rural population have an important bearing upon recreational land problems. For instance, in 1890 the rural population made up 64.6 percent of the total population, while in 1930 it was only 43.8 percent. At the same time, the last census showed that the large cities have increased in area, but not in density of population within their older sections. Three-fifths of the total population increase occurred in five well-defined groups of cities which had but 26.2 percent of the Nation's population in 1920. Today a total of 47,395,009 inhabitants, or approximately 38 percent of the total population, is crowded on one-fifth of 1 percent of the total Land area of the United States.

Recreational needs and requirements during the past 70 years have been affected profoundly by the tremendous shift from agriculture to industrial, commercial, and professional occupations, because of the resultant concentrations of population.

In 1930 only 21.3 percent of all gainfully employed persons over 12 years of age were engaged in agriculture, lumbering, and fishing, whereas manufacturing and mechanical industries, trade and transportation, and clerical employment accounted for 57.5 percent.

In 1890, 18 percent of all children from 10 to 15 ears, inclusive, were gainfully employed. When the new code regulations went into effect in 1933, the employment of this age group was practically abolished. Since school attendance of children and young people occupies only 6 hours a day and 180 days a year, it behooves the public to provide adequate recreational facilities for them, so that their leisure time may be utilized beneficially.

With the continued development of labor-saving devices and scientific management of industry, opportunities for gainful employment will be fewer. There has been a steady decline since 1910 in the percentage of males in all age groups gainfully employed. The decrease in opportunities for gainful employment will likely affect more and more the children, young people, and old people of both sexes. Between these two extreme age groups there will be a group of gainfully employed persons working shorter hours.

This situation—fewer persons gainfully employed and shorter hours of work for those who have employment—creates an unprecedented and critical problem which demands farsighted planning for use of the increased amount of leisure at the disposal of the public. This leisure can be made of value in raising the physical, cultural, and spiritual level of the American people, if proper provision is made for its use, and it is guided into proper channels. Failure properly to provide for it throws the doors wide open to every antisocial influence, since the truth of the old saying "the devil always finds some work for idle hands to do", is as true now as it ever was.

In addition to planning for the recreational use of leisure, it would appear highly desirable to devise ways and means of using a measure of this enforced leisure in various forms of public service, as is being done now through the Civilian Conservation Corps, and also in developing home handicraft arts.

All of these conditions have given rise to the public responsibility for bringing about an adjustment between nature and man, out of which have come the present provisions and new plans for varied types of recreational areas.

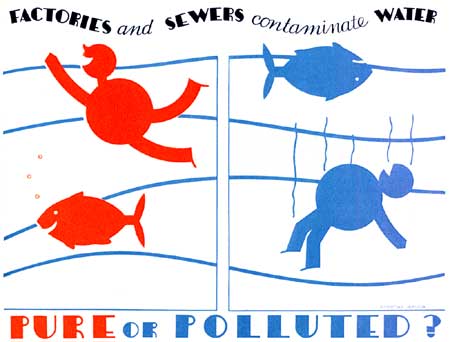

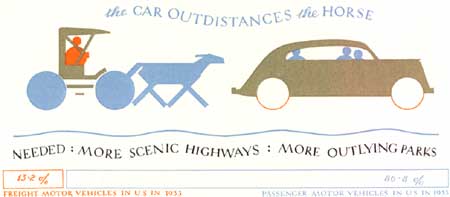

FIGURE 3.

(click on image for a enlargement in a new window)

Geography of Recreation

Humanity is distributed without any orderly relationship to recreational resources. When population is favorably situated with reference to recreational resources, it can only be considered a matter of fortunate accident. Recreational planning cannot be successful unless it takes into account the discrepancy between the distribution of populations and recreational resources.

Variety of elevation is an important factor in the recreational value of lands—the mountains are always eagerly sought. Water resources—lakes, streams, waterfalls, bays, and oceans—are a factor of the utmost significance in the recreation scheme, both because they constitute such a great part of the beauty of the outdoor scene, and are highly valuable for active recreation. On almost every recreation area the greatest concentration of use occurs in the immediate vicinity of the water. It is a happy circumstance that 45 percent of the total population, or 55,000,000 persons, live within 55 miles of the sea coasts and Great Lakes.

It is axiomatic that pleasurable outdoor recreational experiences require favorable climatic conditions. Rainfall, sunshine, humidity, and temperature all have their effect upon the pattern of recreational geography.

Flora and fauna provide the living interest, without which no recreational area is complete. Forested areas, of course, rank high in the order of preferment, and natural abundance of plant life of many kinds is always an asset. In the geography of recreation, the variety, abundance, and the distribution of fauna are important factors. The smaller forms of wildlife, particularly the birds, add materially to the value of the smallest recreational areas, such as downtown parks and residence gardens. Hunting and fishing are among the leading, if not the greatest, of American outdoor recreational activities. They are factors which exert a great "pull" on population.

While all these factors have an important bearing on recreation from a national viewpoint, they have an equally important recreational significance considered from a regional, State, county, or metropolitan viewpoint, the principal difference being that the range of choice progressively decreases as the size of the unit under consideration decreases. Other things being equal, that area, whether national park, regional park, State park, or metropolitan park, which has favorable natural factors of the highest order available within the area be served, will exert the strongest "pull", and will tend to the greatest extent to refute the validity of any scheme which is based on a fixed pattern of distribution.

FIGURE 4.

Some Competitors of Recreational Land Use

Some of the important competitors of recreation are: Private consumption of recreational resources, water pollution, lumbering, grazing, drainage, and artificial stream control.

The common desire to own a small segment of forested lake front or stream side for a summer home is rapidly leading toward the exhaustion of these resources, insofar as their availability to the great portion of our population is concerned. It is not probable that the common demand for outdoor living will be satisfied when this limited natural resource will have passed into private hands. Moreover summer homes, dude ranches, and resorts frequently occupy strategic points which actually control the much larger hinter land. It is believed that the policy of permitting summer homes within public lands of recreational value should be carefully reconsidered to the end that a more equitable and sustained use of the resource may be attained.

No definition of water pollution is needed. Every one knows that large quantities of foreign matter such as oil, refuse from rayon, paper, and saw mills, sulphurous water from mines, sewage, and other industrial and civic wastes are discharged into our rivers, lakes, and harbors. In addition to the effect upon aquatic life, healthful water and shore recreation are affected, and fire hazards created.

Lumbering is one of the necessary forms of land use but it does not improve the recreational value of an area. Unless an aroused and enlightened public acts in its own behalf, the finest remaining primeval forests will go down before the logger.

Stock grazing has a definite effect on recreational values. Where overgrazing occurs erosion is abnormally accelerated and the final condition of terrain renders it almost useless for wildlife, and, in fact, for any kind of recreational use whatsoever. Overgrazing on the headwaters of a stream may render its entire course unfit for recreation.

No problem today more vitally affects the future of our wild waterfowl (and therefore the recreation of millions of people) than the drainage of swamps and marshes. As a nation we have been dealing with our marshes much as we have with a great many natural resources; acting first and considering consequences later. The recreational value of such areas has been brushed aside as a matter of idle sentiment. Drainage is conducive to rapid rum-off resulting in erosion, streams of flood character, and the depositing of debris. Certainly, drainage projects should not be undertaken without comprehensive knowledge of the ends sought, the values involved, and the probable results.

The construction of reservoirs for irrigation and power frequently results in the destruction of scenic, historic, and archeological values. In extremely arid regions reservoirs may add recreational value; but this should not be overestimated, for fluctuating water levels leave an unsightly, unusable "no-man's land" between high and low water, wherein all vegetation dies and the accumulating litter decays.

It becomes evident that the forms of land use which compete with recreational land use are not confined to recreational areas per se. In other words, area is not a proper unit of measurement because recreational resources permeate the whole mosaic of our national resources. Recreational use of national resources, therefore, must be correlated with other forms of use, except within areas of primary recreational value. In these latter, no competing use of the resource can be permitted. Any analysis of such forms of land use and abuse and their relation to recreational resources suggests very strongly the need of a Federal agency whose responsibility it should be to call attention to recreational resources, particularly when other uses of such resources would needlessly destroy their recreational value.

FIGURE 5.

Economic Aspects of Recreation

Since it costs money to provide recreation, and since its provision has certain economic effects, it is important to know to what extent the public provision of certain kinds of recreation is justified. What is the cost of providing Americans with leisure time occupation? What effect do the parks have on property values and employment? Does the public cost of providing recreational facilities have offsets in decreased expenditures for jails, insane asylums, and correction homes? How is the public to bear its share of the cost of selecting, acquiring, developing, and operating recreational facilities, and what costs may the users of publicly owned recreational facilities be expected to bear? What is the extent and importance of private enterprise in recreational economy?

A few years ago it was estimated that the annual national expenditure for recreation amounted to more than $10,000,000,000. In 1932 the Federal Government expended $10,857,000 for development and operation of areas and facilities established for recreational use. In addition to the National Park Service appropriation there is included in this figure the funds specifically appropriated to the Forest Service for recreational facilities. Portions of the appropriations of other bureaus, such as time Bureau of the Biological Survey and the Bureau of Fisheries, should be added to the Federal recreation bill.

In 1931 estimates of State expenditures for recreation indicated a total of $41,830,000, and of this total $14,258,000 was for operations. Expenditures by county, metropolitan, and municipal governments approximated $162,853,000.

Funds for the establishment of recreation areas are acquired by general taxation, special assessments, excess condemnation, donations, transfers, leases and permits, or any combinations of these. Costs are to some extent offset by income which is derived from the use of public recreational facilities. During the fiscal year 1934, $731,332 was received by the National Park Service from various park fees. Concessions of various types serving recreation seekers brought an income of $297,831 to the United States Forest Service in the same year. Figures on the State income for recreation are not available at the present time, but there has been a marked tendency in recent years to make State parks earn at least a part of their development and operation costs. There is a growing feeling that the special service charge is a more equitable means for providing maintenance funds than is the straight entrance fee. Fish and game activities are largely supported by State license fees.

Developed recreational resources have economic effects, one of which is the improvement of adjacent property values. However, no comprehensive figures are available on this. Creation of parks has stimulated logical civic planning, such as the creation of zoning restrictions. The study of recreational land use as a factor in rural economic life is yet in its infancy. Certainly, in many localities encouragement of recreational business has served partially to offset the decline in agricultural values. It is possible that this factor will prove to be the economic salvation of some upland States. These benefits come chiefly from establishment of summer homes, summer camps, resorts of various kinds, and all the commercial undertakings which derive benefits from these and from the people who use them. In Connecticut, for example, the total assessed value of land and buildings devoted to recreational purposes is $200,000,000.

State parks which draw an appreciable volume of more than 1-day use create markets for farm products. State park users are frequently good customers for rural handicraft products. They sometimes create demand for overnight accommodations in nearby towns and farms.

One economic result that is socially undesirable but which has an influence on real estate values is the tendency of parasite commercial ventures to establish themselves close to park entrances. The experience of State park authorities in obtaining extensions of existing parks is ample proof of increased values either actual or assumed. The natural economic benefits of park establishment to surrounding lands are responsible for pressure to secure parks in areas unsuitable for park purposes, and this pressure must be resisted for obvious reasons. Planning predetermines which sites are desirable, thus providing bulwarks against such pernicious pressure.

It would be impossible to determine the amounts of the offsets to certain other governmental costs which arise from the adequate provision of recreational facilities. There are many examples, however, where a definite decrease in crime and in juvenile delinquency has come as a result of providing accessible recreational facilities.

Private enterprise in the field of recreation constitutes one of the major businesses of the country. The public provision of recreational facilities is a very large factor in the promotion of commercial recreation enterprise. It is estimated that almost $4,000,000,000 was spent in motor camping and other vacation travel in the United States in 1929. For the same year it is estimated that hunters and fishermen spent $650,000,000 in addition to their transportation expenses. The investment of duck shooters in sporting equipment has been estimated at between one and two hundred million dollars. As a very rough estimate it was said that $1,750,000,000 was expended on forest recreation during the peak recreation year of 1929. A type of active recreation which looms large in the economic picture is golf. The estimated value of private golf club properties was $765,000,000 in 1931. Existence of publicly owned golf courses, tennis courts, baseball diamonds, etc., is directly responsible for a large part of the investment in sport clothing and equipment.

A large volume of privately conducted commercial enterprises is found actually within the public forests and parks themselves, where hotels, lunchrooms, and stores have been established and are operated under concession or franchise contract. Recent studies by the Forest Service show that there are within and near the national forests more than 5,000 farms and ranches primarily operated for recreational purposes, including hunting and fishing. The 1929 report of the Dude Ranchers' Association, an organization composed of ranches in Montana and Wyoming whose business is based on recreation, shows 51 ranches with property valued at 6-1/4 million dollars, and annual receipts of nearly a million and a half dollars.

Federal Agencies Concerned with Public Recreation

National Park Service.—The primary function of the National Park Service is to administer the federally owned areas of superlative scenery, and of outstanding historic, prehistoric, and scientific importance, with the twofold objective of preserving the principal features of these areas, and of providing for the public enjoyment of the same in such manner as to leave them unimpaired for the future. The Service also has other duties which include the administration of the parks of the National Capital, operation of certain Government buildings, and supervision of Emergency Conservation Work in State, county, and metropolitan parks, as well as in national parks and monuments.

The first national park was Yellowstone, established by act of Congress in 1872. The National Park Service was not created until August 25, 1916, when there were already 16 national parks. There are now 24 national parks and numerous national monuments and other reservations under the administration of the National Park Service. The earliest national parks were spectacular areas of the public domain, withdrawn from entry and reserved for public use. More recently there have been added to the system suitable lands that have been acquired from private ownership and presented to the Federal Government.

The Antiquities Act of 1906 authorized the establishment of national monuments by Presidential proclamation. The national monuments are Federal areas containing objects of historic, prehistoric, or scientific interest.

For 18 years Yellowstone was the only national park, During the first 25 years of its history many questions regarding its administration came up in Congress, and policies were established that have since been applied to other national parks, thus helping to form a code of administration for the system. The merit of Yellowstone as a national reservation did much to stimulate the general policy of Federal control of superlative areas. The twin purposes are the preservation of the areas for future generations and their use by the present generation. No individual can acquire exclusive control over any part of a national park. Facilities for public use are provided by operators who hold leases under contracts which provide for supervision of their operations and regulation of the prices charged.

The national interest dictates decisions regarding public or private enterprise in the parks. National parks are wildlife sanctuaries and hunting is not permitted, though fishing is allowed because of the replaceable nature of this resource.

The educational opportunities of national parks and monuments are great, since the areas contain the supreme in objects of scenic, historic, or scientific interest. Education is an important part of the enjoyment and benefit that may be derived from the use of the parks. An important service to individual development is that of inspiration. The naturalist service supplements, but does not duplicate, the natural history offered by schools and colleges. This service is made freely available to all park visitors to aid in their appreciation and interpretation of scenery and other park features. The extent to which visitors utilize this service depends upon whether their interest is elementary or technical, casual or constant.

Administration of the parks deals with problems in forestry, construction of roads and buildings, and wildlife conservation. Careful attention is given to landscape matters in order that developments may aid, and not interfere with, the primary purpose of the reservations.

At the present time the areas administered by the National Park Service in the 48 States are designated as follows: 24 national parks, 1 national historical parks, 11 national military parks, 67 national monuments, 10 battlefield sites, 11 national cemeteries, and 4 miscellaneous national memorials, making a total of 128.

The total area of the principal groups within the 48 States is as follows: National parks, 6,444,734 acres, national monuments, 2,825,469 acres, other designations, 18,407 acres, making a total of 9,288,610 acres or approximately 14,513 square miles.

Travel to the national parks has increased with the greater use of automobiles, with improvement of the highway systems of the country, and with a more widespread knowledge of the national parks and a growing public interest in them. At the time of the organization of the National Park Service in 1917 the volume of travel to the national parks was small, less than one-half million people. In the 1934 travel year (Oct. 1, 1933—Sept. 30, 1934) there were more than 3-1/2 million visitors to the national parks, and the total number of visitors to all national parks, monuments, and other reservations exceeded 6 millions. The need for development of facilities for visitors to national parks has grown greater with the increase in travel, but in many of the national parks and other areas the development has lagged behind the actual needs.

The Government builds and maintains administrative and housing facilities for the employees of its organization; also builds and maintains roads, trails, museums, information offices, comfort stations, public camp grounds, and facilities, which are available to the public without charge. Hotels, restaurants, hospitals, transportation, and other services, for which a charge is made, are provided by privately owned companies. National park automobile license fees are collected from private automobile entrants in some of the parks, and all parks revenues are turned in to the Treasury as miscellaneous receipts.

Congress has authorized the establishment of the following national parks and national monuments when the ands involved are deeded to and accepted by the United States without cost, and when certain other special provisions in individual cases are met: Shenandoah National Park, in Virginia; Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky; Isle Royale National Park in Michigan; Everglades National Park in Florida; Badlands National Monument in South Dakota; Monacacy National Military Park in Maryland; Ocmulgee National Monument in Georgia; and the Pioneer National Monument in Kentucky.

Bureau and of Biological Survey.—This Bureau administers lands reserved, purchased, or leased for the benefit of migratory birds and other wildlife. The principal value of these game and bird refuges is recreational. They offer recreation by improving the hunting (both gun and camera) elsewhere. Preserving rare species of birds and animals from extinction also has a recreational value. The Bureau administers 104 wildlife refuges, of which 65 are maintained primarily for migratory waterfowl.

Bureau of Fisheries.—This Bureau conserves aquatic resources by means of restocking, makes biological investigations and technological studies, and regulates the Alaska fisheries. It furnishes recreation by maintaining the supply of game fish in addition to serving commercial fisheries. It is estimated that there are about 10 million anglers in the United States. The Bureau cooperates with other Federal agencies and with the various States and organizations of sportsmen. The annual output of its hatcheries includes about one hundred million game fish and several billion commercial fish. The greater part of the Bureau's funds and activities are devoted to the production of game fish, which require much more care and expense than commercial fish.

Forest Service.—Under direct administration by the Forest Service are more than 160 million acres of national forests in 33 States, as well as in Alaska and Puerto Rico—an area approximately equal to the unappropriated and unreserved public domain. This acreage is being rapidly increased, particularly in the South and Middle West, under the present purchase program.

The national forests are managed on the principles of providing the greatest good for the greatest number in the long run. In national forest recreational development the stress is laid on providing healthful outdoor recreation. Camping, hunting, fishing, hiking, and mountaineering are encouraged.

Several different types of recreational forest areas are recognized: Superlative areas, primeval areas, wilderness areas, roadside areas, camp-site areas residence areas, and outing areas. Another grouping, in more general use at present, is composed of natural areas, primitive areas, and recreational areas.

The Forest Service looks upon the recreational possibilities of the national forests as a public resource to be used wisely and to be carefully safeguarded. Special use permits are given to those who desire summer homes, hotels, and resorts.

Recreational use is secondary to the primary objective of forestry, but the two uses are generally coordinated. It is necessary to supervise the recreational use of the forests to reduce fire hazards and unsanitary conditions. Fishing and hunting are permitted in most of the national forests. Some Federal game refuges have been established and numerous State game refuges have been created within the forests.

In 1917, there were 2 million visitors to the national forests; by 1933, there were 35 million, including not only those who camped or hunted or fished on the forests but those who drove through them.

About 3 million acres of national forests have been closed to domestic livestock in the interest of wildlife improvement.

Bureau of Reclamation.—The Bureau is charged with the investigation, survey, and construction and maintenance of irrigation works for storage, diversion, and development of waters for the reclamation of arid and semiarid lands in the States west of the one hundredth meridian, and also with the development and use of hydroelectric power in connection with such projects. The reclamation projects are generally unsuited for national parks and monuments because the works of man predominate over the works of nature. Recreation is a secondary consideration to reclamation projects, and no extensive developments have been undertaken by the Bureau for recreation. However, there are some boating and fishing on reclamation reservoirs, and camping near reclamation projects. Recreation in connection with reclamation projects could be stimulated by the Federal Government.

In 1932, the area irrigated with water from Reclamation Service projects was 2,769,605 acres. Many of the storage reservoirs administered by the Bureau are stocked with fish.

Office of Indian Affairs.—The Office of Indian Affairs is charged with all matters pertaining to the Indians while they remain on their reservations. The areas of the public domain which have been set aside as Indian reservations (1934) comprise 48,131,070 acres.

Many of the Indian reservations are highly scenic, and if made available for public use, parts of the reservations could be developed for recreational purposes; but since the areas are set aside primarily for the Indians, any recreational use of the reservations must be restricted to that which is consistent with the welfare of the Indians.

General Land Office.—The General Land Office supervises the survey, management, and disposition of the public lands and the public mineral lands, the granting of railroad and other rights of way, and surveys lands in the national forests, public domain, and national parks and monuments. The original public domain in the United States proper contained 1,442,200,320 acres. The 378,165,760 acres of Alaska are also part of the public domain. The lands for which title has passed from the United States total 1,016,214,480 acres. The unappropriated and unreserved public lands in the continental United States as of July 1, 1933, amounted to 172,084,580 acres.

There are few areas of the unappropriated public domain which are extensively used for recreational purposes.

Some parts of the unappropriated public domain are highly scenic, and certain areas should be added to existing national reserves. Other portions of the public domain would be valuable for wildlife production, if present overgrazing by domestic stock were prevented.

Federal Lands in the Territories and Insular Possessions.—The total area of Alaska is 378,165,760 acres, of which 27,628,378 acres are reserved as national forests and national parks and monuments. The total area of the Hawaiian Islands is 4,117,360 acres. Hawaii National Park has an area of 156,800 acres. Many opportunities for recreation are found in these islands, such as swimming, fishing, hiking, tennis, horseback riding, and hunting.

There are few public lands available for recreational development in insular possessions such as Puerto Rico, Guam, Virgin Islands, Samoa.

The territories and insular possessions offer opportunities to the people of continental United States for recreational and educational travel.

State and Interstate Systems

State Parks.—The total area of all State parks 3,755,985 acres, or about 3 percent of the area of the national forests. This acreage comprises five types of holdings, i. e., State parks, recreation reserves, monuments, waysides, and parkways, and yet because the State parks are readily accessible from large centers of population, they are visited annually by a greater number of people than visit the national parks and forests combined.

Forty-six of the 48 States now have State parks or areas set aside primarily or wholly for recreational use, Colorado and Montana being the only two not having State-owned areas for recreational use. It is estimated that the number of visitors to State parks in 1930 was 45,000,000.

The first recreational areas established by a State were the "Great Ponds" of Massachusetts, which were decreed by ordinance in 1641 to be "forever open to the public for fishing and fowling", and their legal status remains unchanged today.

The first State park included Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove, and was granted to California for that purpose by Congress in 1864. Later it was returned to the Federal Government for inclusion in Yosemite National Park.

The comparatively low acreage of State parks in many Western States is partly compensated for by the fact that national parks and national forests offer excellent recreational opportunities for the people of these States.

A few States have made reasonably adequate funds available for the acquisition, development, and maintenance of State parks, but in most States this field of activity is still struggling for sufficient recognition. In some States comprehensive surveys of recreational resources have been made, and a few States have built up excellently balanced systems of State parks, but in many cases areas have been included which are either too small, of little value for recreation, lacking in scenic quality, or too expensive to operate. While most State recreational areas are called State parks, the parks themselves vary from large, important areas to small tracts of little value.

The method of administering State parks varies widely. The commission form is one of the most frequent and successful types of administration. State parks are often administered in connection with State forests. The powers of the park administration representing the State usually include the purchase of lands for use as parks, the acceptance of lands or funds, the right of eminent domain, the construction of roads, buildings, and other facilities, the employment of personnel, and the enforcement of rules and regulations.

Those States which have employed competent, technically trained men have usually been most successful in developing areas for public use without destroying the primitive scenic values of the areas.

Camps and picnic grounds are usually operated by the States, while overnight lodging, cafes, and similar services are provided by concessionaires. The granting of summer home sites and other exclusive, individual rights, has been tried, but such a policy is generally disapproved.

Nature guide service is given to visitors in the case of a few States; some nature trails are in use; and museums are found in a number of parks. The extension of educational uses of State parks offers a wide field of opportunity for the future.

The preservation of natural conditions and development for recreational use are the principal objectives of State parks.

A number of State park systems include areas which have historic, prehistoric, or scientific importance, as well as areas of scenic value. Historic sites are usually not suitable for active recreation, and their value should not be impaired by any use which conflicts with their main purpose.

Foot Trails.—In some States foot trails have been established, usually with the aid of outdoor organizations. These trails are carefully selected strips of land over which the right-of-way has been granted by landowners. The Appalachian Trail, extending along the mountain ranges from Maine to Georgia, more than 2,000 miles in length, is a notable project of this type.

State Forests.—State forests have important recreational values, and they are utilized to a varying extent in different States. Some of the State forests offer excellent opportunities for hunting and fishing, as well as camping and a variety of outdoor activities. The State forests are usually larger areas than State parks and have less density of use.

Local Systems

Metropolitan Recreational Areas.—A metropolitan district, as defined by the. Federal Census Bureau, comprises a central city and all adjacent civil divisions having a density of population of not less than 150 inhabitants per square mile. In 1930 there were 96 metropolitan districts in the United States, each having an aggregate population of 100,000 or more.

The objective of metropolitan park planning is to secure recreational areas which are accessible for frequent use by the people of the district. Metropolitan recreational systems include areas within the central city, and in the smaller cities of the district, but the larger areas are usually located in the more open and less populated parts of the region. With the present use of automobiles, areas within approximately 50 miles of the center of a metropolitan district, are accessible for frequent recreational use, even though they lie outside of the district itself.

There are only six special metropolitan park districts in the United States.

In 1930, 186 cities of the United States reported owning a total of 381 parks, outside of their boundaries, but within their metropolitan region. The area of these parks was reported as 90,000 acres.

County Recreational Areas.—The county has potential importance as a governmental agency in metropolitan park planning. The total area of county parks in the United States in 1930 exceeded 100,000 acres. The majority of the 74 counties reporting one or more county parks in 1930, lie wholly or partially within the metropolitan regions of cities. More than half of the total county park areas in the United States is in counties of the metropolitan regions of New York and Chicago.

Recreational services provided in many county parks include those services which are offered in city parks.

Other county parks are larger areas, kept in a natural condition, and with a limited amount of development.

A prominent feature of the larger county park may be the parkway. Usually a parkway may offer other recreational opportunities in addition to motoring.

Municipal Recreational Areas.—Because of the present high concentration of the population of the United States in urban communities, the chief burden of year-round recreational service must fall upon the municipal parks. The best utilization of lands and waters within and near the boundaries of cities, is highly important.

In 1930, 1,072 cities having a population of 5,000 or more, reported having a total park area of 308,805 acres. The average ratio of park area to population was one acre to every 208 persons.

In municipal recreation systems, the children's playgrounds and neighborhood parks are the most numerous. The greater part of the area, however (more than 75 percent of the total), is in large parks, such as outlying forest parks or similar reservations. Municipal recreation systems sometimes show lack of balanced planning. The area devoted to children's playgrounds and neighborhood playfields is often inadequate, and so, too, are the areas devoted to educational-recreational purposes.

The ratio of 1 acre of recreational area to every 100 of the population in cities of 10,000 is generally accepted as a reasonable standard, and a ratio of one acre to 275 inhabitants may be assumed as a standard for cities of between 5,000 and 10,000 population. On this basis all cities having a population of 5,000 and above have less than one-half of the desirable minimum acreage of recreation space.

Township Recreational Areas.—The township unit is more important in New England than elsewhere in the United States. For statistical purposes, these recreational areas are usually grouped with those of municipalities.

FIGURE 6.

Park Educational Work

Some guiding principles of park educational works are

1. Simple, understandable interpretation to the public of the major features of each park by means of field trips, lectures, exhibits, and literature.

2. Emphasis upon leading the visitor to study nature in situ rather than to utilize second-hand information

3. Utilization of a highly trained personnel with field experience, able to interpret for the public the laws of the universe as exemplified in the parks, and able to develop concepts of the laws of life useful to all.

4. Pursuance of a research program for the purpose of furnishing a continuous supply of dependable facts suitable for use in connection with the educational program.

In the field of national parks, endeavor has centered upon placement of trained men—scientists or historians—in every parks to act as curators of natural treasures and technical advisers on scientific features, and with the help of temporary naturalists or historians, to conduct a five-point program consisting of guided trips, and campfire lectures, museum programs, nature trails, and useful publications. Guided trips constitute the most important and most unique part of the program. The method stressed is expressed in Agassiz's old dictum: "Study nature, not books."

An essential part of an interpretive program is the park museum and the orientation station. Objective materials have been used to tell a simple story. In some cases a central museum has rooms devoted to geology, biology, ethnology, and history; in other cases wayside museums have been provided, each one explaining nearby phenomena—rock formations, geysers, history, or animal life. The museums provide head quarters facilities for the educational staff.

The nature trail is an efficient method of helping park visitors to become acquainted with interesting geologic and biologic features along a trailside. There are always those who prefer studying things quietly by themselves, and labeled rocks, trees, and plants fulfill this requisite. Self-guiding nature trails are now available to the public in many parks.

The Yosemite School of Field Natural History is an annual summer school for the training of naturalists, where emphasis is placed on the study of living things in their natural environment. The teaching staff is composed of university professors who donate their time and of members of the Yosemite naturalist service staff. Though no university credit is offered, a certificate indicating accomplishment is awarded graduates of the school.

An educational program must be founded on reliable facts secured through scientific research. Facts useful in the work must be culled from literature, and much library work must be done by trained historical assistants before a dependable story can be told. Hence, the need for the historical research staff located at the Library of Congress. Likewise in the field of biology there must be a staff of technically trained men to study the fauna and flora of the park areas, furnish the facts needed for proper wildlife administration, and develop wildlife policies to be followed. Only a start has been made on a research staff sufficient to improve accuracy of statement and safety of method employed.

Present park educational programs are inadequately supported financially and are undermanned everywhere. Added financial support to permit increased personnel, looking toward adequate meeting of demand, and additional working tools is the greatest need at present. With increased travel and use of educational facilities must come an expanded program. The national park educational program, but 14 years old, has passed the stage of an experiment and attained that of a stabilized and valued activity. There remains little need for changing objectives or methods but great need for serving the public more adequately. This can readily be accomplished by an increase in permanent and temporary personnel and provision of museum units where needed.

It is in State and municipal parks that there is greatest need for educational programs. Travel is very heavy and visitors seek profitable utilization of their time. There is ample proof from such projects as Oglebay Park in West Virginia and Bear Mountain Park in New York that national-park methods are equally applicable in State and territorial parks. Modification of programs to meet the shorter stay and the more local-minded visitor is relatively easy, if emphasis be placed on self-guiding trails and museums, as is done in Bear Mountain Park in New York State.

The National Plan for Public Recreation

The national recreational plan developed herewith rests upon the following postulates:

1. Recreation connotes that which is re-creative of the individual, the community, or the Nation.

2. Recreational use of resources is not restricted to parks and recreation areas, but may be a concomitant use of almost any resource.

3. Recreation is dependent upon conservation.

4. Areas, primarily of recreational value, should be designated and conserved unimpaired as such, and should not be jeopardized by other commercial use.

5. Because recreational use of national resources frequently must be concomitant with other uses, the provision for recreation must be included in a national conservation plan.

Details of a national recreation plan must be developed upon a continuous recreational survey. Existing agencies of government, however, can inaugurate a national plan for the conservation of recreational resources. The principles upon which it is proposed to coordinate existing agencies of government toward the inauguration of such a plan are developed in this report as follows:

To provide facilities for the day-by-day recreational needs of the people is primarily a local responsibility, whether met by municipalities of sufficient population and wealth to supply all the various types of recreation required, or by county or metropolitan park boards which, dealing with the needs of a group of urban and rural communities, make it possible for each of those communities to enjoy such facilities. Use by outside residents of facilities so supplied and maintained is incidental.

Every State has areas either of such high scenic value or of such high value for active recreation, or both, or possessing such interest from the scientific, archeological, or historical standpoint, that their use tends to be State-wide in character. Acquisition of such areas and their development and operation appear to be primarily a function of the State, though this should not preclude joint participation in acquisition, and possibly in development and operation, by the State and by such community or communities as might receives, a high proportion of the benefits flowing from their establishment.

Taking the Nation as a whole, there are, again, areas of such superlative quality, because of their primeval character or scenic excellence, or historical, archeological, or scientific importance, or because of some combination of these factors, that they are objects of national significance. It is the responsibility of the Federal Government to acquire and administer these.

The Federal responsibility is emphasized particularly in the case of the primeval wildernesses. There are several reasons for this. Remaining areas of primeval condition are few. Those who live in the regions immediately adjacent to the wilderness are usually pioneers whose lives and thoughts are devoted to wilderness conquest. Hence the Federal eye rather than the local eye must be depended upon to recognize and protect the wildernesses that remain. A wilderness reserve ordinarily must be of great size, if it is to remain primeval, and the present value may seem insignificant, whereas the deferred value is very great. With all these conditions and circumstances, it is apparent that the monumental tasks of saving the primeval must be very largely a Federal responsibility.

In addition there is another group, the ocean and Great Lakes beaches, which are so heavily freighted with national interest, and are so extensively sought by persons living at great distances from them, and which are so unlikely to be acquired by the States to a sufficient extent, that it would appear reasonable to expect the Federal Government to acquire and administer a representative group of them.

It becomes evident, therefore, that a national recreation plan must have local, State, and Federal components.

Park Requirements of Municipalities.—The focal point and foundation of a national recreation plan are within the municipalities and their immediate environs. The essential problem is to provide places for rest and active recreation within easy access of the inhabitants of these municipalities.

Essential recreational requirements of any municipality include adequate and properly distributed play areas for children and adults, "intown" small landscape parks, and a few parks of the types generally referred to as large parks.

While the provision of one acre of recreation area to each hundred persons—of which 30 to 50 percent would be comprised of play areas of various types—is accepted as a desirable and satisfactory minimum for municipalities of 10,000 inhabitants or over, it appears that to provide communities of smaller population with the essential components of a city park and playground system, the ratio of recreational area to population should be larger, approximately as follows:

| Community population | Number of inhabitants served by 1 acre of park and playground |

| 5,000-10,000 | 75 |

| 2,500-5,000 | 60 |

| 1,000-2,500 | 50 |

| Under 1,000 | 40 |

Cities of 10,000 inhabitants or over have a total population of 58,340,077. The minimum desirable recreational area for these cities is estimated at a total of 583,401 acres; the total for towns and cities with less than 10,000 inhabitants each is estimated to be 362,737 acres. On this basis, the total minimum desirable area devoted to municipal recreation would be about 10 percent of the total area of all lands devoted to municipal uses in the United States.

Cities of 10,000 inhabitants or more may be expected to provide year-round administration for their recreation properties. This appears to be impossible for the smaller communities which must look to some larger governmental unit, such as the county, to provide it. In so doing the county can, at the same time, provide recreation service, under leadership, for the population resident in the open country.

In cities where the requirement is 1 acre to ever 100 persons, the total recreational area should be divided approximately as follows: Children's playgrounds, 12 percent, composed of units from 3 to acres in extent; neighborhood playfields, from 15 to 1 percent; miscellaneous recreation areas, an undetermined percentage, depending on the kinds of recreation to be provided; the three types totaling 30 percent to 5 percent of the whole. The balance would be compose of equitably distributed neighborhood or "intown" parks and large areas characterized by landscape or natural features, in acquisition of which it is desirable when possible, to exceed the standard minimum acreage by a comfortable margin.

Park and Playground Requirements of Metropolitan Regions.—Provision of parks and playgrounds for the population of metropolitan regions comes next in importance in the national recreational scheme. Here, planning involves provision of recreation service for the inhabitants of the principal cities of a kind which cannot be supplied effectively within those cities; an in addition, recreation service for residents of small "satellite" cities and of rural farm and rural nonfarm areas.

With the steady movement of population into metropolitan areas, outside of the central municipalities, and the loss of population within the central municipalities, there is also a definite drift of population into zones close to the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, the Gulf, and the Great Lakes. About 50 percent of the population now lives within daily access of cities of 100,000 inhabitants or more. Within metropolitan districts, as defined by the Bureau of the Census, there are 54,753,645 persons, of which 16,939,035 live outside the central cities.

Because the rate of population increase for the metropolitan areas outside the central cities is greater than the increase for the country as a whole, and because the central city population is declining, it appears that emphasis on planning land use for recreation in this group should be centered in the metropolitan areas outside of the central cities. Not only is this necessary to prevent recurrence of the lack of needed open space characteristic of the central cities, but to provide types of areas which neither the central cities nor the outlying cities can provide for themselves.

Metropolitan regional planning can exclude both the central city and the large municipalities in the metropolitan district, which are expected to provide municipal parks and playgrounds for themselves. Planning tends to concern itself with zones: One, the area of fairly heavy population surrounding the central city where the types of recreation area to be provided are analogous to those within the municipality; the other, the more sparsely populated area within approximately 2 hours of automobile travel of the central city. Provision of recreation lands in the inner zone demands special attention, and should be on a liberal scale so that, with the anticipated increase, the requirements as to types, and extent as established for municipalities can be properly met. Provisions within the outer zone should be of more extensive areas of naturalistic character.

Determination of responsibility for provision of lands required for recreation within metropolitan regions is a complex matter. A number of cities have gone well beyond their borders in acquiring parks. Counties, special metropolitan park districts, and States may all act as agencies for provision of metropolitan parks. A very large number of States have shown themselves disposed to accept a liberal share of responsibility for provision of the large outlying areas characterized by better than average natural scenery or by high active-recreation value. They appear to continue to play an important part in the metropolitan park field.

Counties in metropolitan districts have acquired in excess of 100,000 acres of parks and play areas. The fact that a single metropolitan district may lie in two or more counties or even in two or more States makes it difficult to attain uniformity of planning and administration on a county basis. This fact indicates the wisdom, in many cases, of special metropolitan park boards of the type established in Ohio.

The Federal Government, chiefly by chance, has established areas of various types within metropolitan regions. As a result of the emergency program of submarginal land acquisition, it may become an increasingly important factor.