|

National Park Service

Recreational Use of Land in the United States |

|

SECTION II. RECREATIONAL RESOURCES AND HUMAN REQUIREMENTS

1. HISTORY OF RECREATIONAL LAND USE IN THE UNITED STATES

The history of the public recreational use of land in the United States may be said to date from the earliest colonial settlement. In a modest way, and more often for general civic purposes than for recreation as known today, the early town planners and builders made provision for open spaces in their plans. The New England town common is a distinguishing feature of the New England cities of today; the bowling green of Dutch New Amsterdam was an active recreation center; the squares of old Philadelphia and Savannah were reservations for aesthetic, rest, and relaxation purposes; the plazas of the Spanish colonial towns were social, political, and cultural centers. The plans for the new capital city of the Nation, drawn toward the end of the eighteenth century, set a new standard in the number of open spaces or reservations for parks in cities of that time. A decision of the Boston Bay Colony in 1641, that all "Great Ponds" were to be forever open, free to the people for fowling and fishing, was the forerunner of the modern conservation movement for recreation purposes by States.

Unfortunately, from the close of the colonial period to the middle of the last century these excellent examples of town planning and building were not followed except in a few instances, as in Salt Lake City and other towns of Utah, California, etc. Old towns grew into cities, new towns and cities were founded and grew rapidly without any comprehensive planning of open spaces for adornment or recreation. Waterfronts in cites were appropriated for industrial, transportation, and commercial uses. No plans or policies were developed in the first seven decades of the last century by either the Federal or State Governments for the preservation of natural resources of land and water for recreation. About the middle of the last century a few people, noticing the tendency toward urban growth, began to write and speak of the individual amid social evils of crowding too many people on too small areas in cities, without making provision for the people to keep in frequent contact with the elements of a natural environment. They advocated the preservation of large areas within cities to serve as retreats for the people, for rest, in an environment of peace, quietness, and natural beauty, and for such forms of active recreation as would not destroy the essential quality of the areas as places of inspiration and enjoyment of the beauties of nature.

The first concrete result of this movement was Central Park in New York City (1852), followed in rapid succession by the establishment of similar parks in several other large cities of the United States.

From these beginnings during the last half of the last century, have evolved the elaborate systems of recreational areas providing for both active and passive recreations in the cites of today.

The establishment of Yellowstone National Park in 1872 marks the entrance of the Federal Government into the field of conservation of natural resources for recreation, from which has grown the magnificent system of national recreational areas comprised in the national parks and monuments.

Between 1870 and 1890 a few States (California, New York, Michigan, Minnesota) began to establish State recreational areas—a movement which has since spread to nearly every State in the Union.

In 1892-93 the Boston Metropolitan Park System was established as a special method of handling on a district basis the acquisition, development, and administration of recreational areas which it was not practicable for local, town and city, governments in the region to handle alone. The metropolitan district plan has spread to other sections of the country, as seen in Rhode Island, Ohio, Washington, and Illinois.

In 1895 the first county park system was established in Essex County, N. J. Within the past two decades the acquisition, development, and administration of recreational areas by counties have progressed very rapidly. The principal developments have been in counties in the metropolitan regions of large cities, serving practically the same functions as metropolitan park districts, although in a few counties the recreational service provided is primarily for rural and small rural-urban communities.

In all of New England and in some of the other States of the Union the acquisition, development, and administration of recreational areas by townships is authorized by law, powers which have been exercised by many such minor political divisions.

Supplementing areas which have been set aside far various kinds of recreational use by the Federal, State, county, metropolitan, municipal, and town Governments, there are other types of areas which have been acquired by one or more of these political agencies for other primary purposes, but which may have auxiliary recreational uses. Chief among such areas are public forests. The public ownership of forests to its present extent is a development of the past 50 years, although the inception of the movement was earlier. Classed according to ownership, there are National, State, county, municipal, and town forests, with the Federal Government controlling the bulk of such areas. The water reservations, controlled chiefly by cities, and a few metropolitan districts, for supplying potable water to the inhabitants of urban communities, constitute another type of publicly owned areas with a possible auxiliary recreation use. Sanitary considerations often limit the recreational use of potable water reservations, although there are many examples of such use; water reservations for the purpose of supplying water for irrigation, industrial, and power purposes have many possibilities as recreation areas, and are becoming increasingly so used.

The various forms of wildlife reservations set aside, chiefly by the Federal and State Governments, are primarily of recreational and scientific value.

The vast system of National, State, and local highways which cover the country like a network, while not originally created for recreational use, have become of primary importance recreationally, since the invention and widespread ownership of the automobile.

During the past decade attention has been directed to planning of metropolitan regions, and in all such plans a prominent position has been given to conservation of lands and waters for recreation.

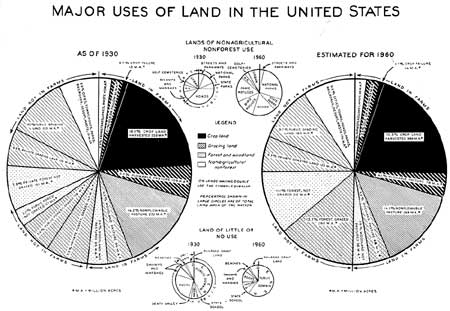

A little over half at the land in the Nation is in farms. Of this land in farms, 38 percent was in crops in 1929 (including crop failure), 37 percent was in pasture (excluding woodland pasture), and 15 percent in woodland, the remainder being crop land lying idle, farmsteads, lanes, and waste land, All crop land is in farms, but the acreage of pasture, including range land outside of farms, exceeds that in farms. About 60 percent of this pasture land not in farms is publicly owned and 40 percent is privately owned. Nearly all this land is in the western half of the country and consists of range, mostly native, short-grass and bunch-grass vegetation adapted to the semiarid or arid conditions, in addition, much forest and woodland (over one-half) is grazed, particularly in much of the west and portions of the south, where the forest is quite open, permitting sunlight to reach the soil. The carrying capacity of this woodland pasture, like that of range pasture, is generally low. The 53 million acres of land used for nonagricultural and nonforest purposes is small, but its value is great, particularly the urban land. Finally, there are about 77 million acres of absolute desert, bare rock, certain marsh lands and coastal beaches which are now valued at almost nothing, but have a social utility for wildlife and recreational use.

Looking to the future, it appears that the estimated prospective increase in population is likely to involve a slight increase in crop land, a decrease of pasture land and of forest in farms, if past trends continue, and increase in forest not in farms, more and more of which seems likely to pass into public ownership, and a notable increase in land devoted to recreational purposes. The increase in crop land will be the net result, as in the past, of decreases in some areas, mostly hilly or eroding lands, or sandy or infertile soils and increases in other areas inherently more fertile or less exhausted of their fertility, or otherwise more productive, or which can be made productive by reclamation.

Within the past 2 years interest has centered on National and State planning through the creation by President Roosevelt of the National Planning Board, later reorganized as the National Resources Board. This organization has stimulated the organization of a large number of State planning boards. Practically all of these State planning organizations have either actually undertaken or contemplate a thorough-going recreational survey and plan for their respective States.

These various public administration agencies have been the primary factors in the evolution of the various systems of National, State, metropolitan, county, and municipal recreation areas, supported, inspired, and sometimes prodded by powerful private organizations of citizens interested in different phases of the conservation of national resources for recreation.

Early in this century the general city planner and the city planning board became another important factor. Planning land utilization for recreation in cities is universally recognized as a fundamental part of general city planning.

Coincident with the establishment of the first municipal parks, an administrative agency was desired in each city to have charge of the acquisition, development, maintenance, and operation of lands for recreational use. This agency universally took the form of a board of citizens, a plan of government still widely prevalent in cities today, although changed in many by the institution of new forms of municipal government (city manager, strong mayor, and commission form of government). County and metropolitan park systems are almost universally governed by boards of citizens, and many of the States have adopted this method of administering recreation areas.

The public recreational movement in America represents a conscious cultural ideal of the American people, just as the great system of public education represented such an ideal. It takes rank with the system of public education as the necessary addition to the cultural equipment of the Nation. Its supreme objective is the promotion of the public welfare through the creation of opportunities for a more abundant and happier life for everyone. The conservation of the resources of the Nation to this end is a most fundamental and important phase of the recreation movement.

2. RECREATIONAL NEEDS OF THE PEOPLE

Physiological and Moral Aspects

Man is essentially an outdoor animal as far as his biological and physiological needs are concerned. Some of the fundamental requisites for his well-being are an abundance of fresh, pure air and sunlight, pleasurable physical activity—especially out of doors—and periods of rest, relaxation, and repose in environments of natural beauty, free from too close human contacts, and from the harsh noises and the high-speed tempo of this machine age. These needs are common to all ages and to both sexes. The supplying of means for the satisfaction of these needs where people are highly urbanized is one of the fundamental reasons for the reservation of lands and waters for recreational use.

It is one of the laws of the growth of human beings (whether growth refers to physical development, mental expansion, cultural enrichment, or social adjustment) that a considerable measure of activity is required in forms expressive of age-old urges, impulses, and instincts. Fullness and richness in living come only when there can be satisfying expression of the natural qualities and powers of the individual which are of physical, mental, spiritual, and social character, during all the age stages of his life. Society justifies itself only to the extent to which it utilizes the natural resources in its keeping. The troublesome question of juvenile and youth delinquency and other antisocial expressions are, without question, partly the result of society's failing to recognize this principle.

It is said that little can be done by society to change the fundamental traits or qualities of any human being, but that much can be done through environment to form attitudes and to determine the direction in which interests and instincts may be expressed. The difference between a delinquent child or youth and a law-abiding child or youth is generally the difference in expression of the same human impulses to action, which—originally neither good nor bad—were subjected to different environmental influences. The lighting impulse which leads a youth to commit law less acts with his "gang" is the same impulse which may make him a highly prized member of an organized sports team. Hence it follows that, given an environment comprising material facilities for the expression of natural, normal impulses, interests, and urges, and given intelligent, sympathetic leadership, it is possible for most children and young people to live fully and happily in harmony with the established usages, customs, and laws of the community.

FIGURE 12.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Population Trends

Total Growth of Population.—The growth of population in the United States during the past 150 years has been phenomenal. It has risen from about 4,000,000 in 1790 to approximately 123,000,000 in 1930, or over thirty-fold. The increase in the decade 1920—30 was 17,064,426, the largest growth ever recorded.1 The rate of increase, however, has been declining since 1860. Prior to that time the average decennial increase had been about 35 percent. The probabilities are that the growth of the population in the future will be small. "Continuation of recent trends would mean that the population probably will he between 132,500,000 and 134,000,000 in 1940, between 140,500,000 and 145,000,000 in 1950, and between 145,000,000 and 170,000,000 in 1980."2

1 U. S. Bureau of the Census, Fifteenth Census of the United States 1930, Population, Vol. 1, Number and Distribution of Inhabitants. (See p. 6.)

2 President's Research Committee on Social Trends, Recent Social Trends in the United States, New York. McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1923. 2 vols., tables, charts. (See p. 2.)

Natural Increase of Population.—The trend in the natural increase of the population of the United States is very disquieting to those who believe that a high birth rate is necessary to the national welfare. The total birth rate has been falling since the population has become so highly urbanized. The birth rate is declining in the country, but to a lesser degree than in the cities. The percentage of children under 5 years of age has fallen greatly since 1870. In that year the number of children under 5 years of age was 14.3 percent of the total population, while in 1930 it was only 9.3 percent. The limiting of immigration; later marriages by reason of higher standards of living; increasing number of women in commercial, industrial and professional life; the deterrent biologic influences of an urban environment; increasing knowledge of birth control; and the fact children are more likely to prove to be expensive liabilities than economic assets under urban conditions, are some of the factors in the declining birth rate. The rate per thousand in 1930 was 18.963 and has fallen from 27.63 per thousand since 1910. The decline in birth rate has been steady and almost continuous since 1924.

3 Willcox, Walter, Introduction to the Vital Statistics of the United Stales, 1900—30, U. S. Bureau of the Census, 138 pp. (See p. 78.)

It is reported that the number of 6-year-old children is now practically stationary; that the enrollment in the first grade of the schools has declined since 1918, in the second grade since 1923, and in the third grade since 1925.4 The percentage of the total population in the age groups 5-9, 10-14, 15-19 years has declined since 1900. This, taken with the previous statement concerning the marked decline of the percentage of the total population of the age group under 5 years means, of course, that the proportion of older people in the population is increasing.

4 Phillips, Frank M., Statistical Survey of Education, 1925—26, U. S. Bureau of Education, Bulletin No. 12, 1928. (Quoted in What About the Year 2000? American Civic Association, 1928.)

On the other hand "the death rate in the United States has been falling for at least half a century * * * The death rate of the United States as a whole in 1900 was not far from 18, in 1930 not far from 12, per thousand", the most remarkable decrease occurring in urban communities.5 The urban and rural death rate are now approximately the same. "The death rate of males is about one-sixth higher than that of females * * * The most marked fall in the death rate between 1900 and 1930 was at the age period 1 to 4 which in 1930 was about one-fourth of the 1900 rate * * * The death rate at ages below 30 fell by more than one-half, at higher ages by less than one-half * * * The death rate of girls and women at every age fell faster than that of boys and men. * * * The death rates of Whites and Negroes decreased at about the same rate but at ages above 35 the death rate of the Negroes Was higher in 1930 than in 1900."6

5Willcox, Walter. Introduction to the Vital Statistics of the United States, 1900-1980, U.S. Bureau of the Census, 138 pp. (See pp. 3—4.)

6Willcox, Walter, op. cit., pp. 3—4.

Growth by Race and Nativity.—Present trends as to population growth among native whites, foreign-born whites, and Negroes show the native whites will increase faster than the Negroes, and that the foreign-born whites will decline. In 1930 Negroes constituted 9.7 percent of the total population as compared with 10.7 percent in 1910. In 1930 the native whites constituted 77.8 percent of the population as compared with 74.2 percent in 1910, while the foreign-born whites were only 10.9 percent of the population in 1930 as compared with 14.3 percent in 1910.7 These trends have a very definite bearing on recreation area planning.

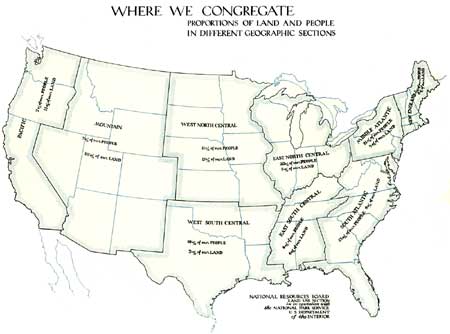

Geographic Distribution.—The land area of the United States comprises 2,973,776 square miles or 1,903,216,640 acres. The gross area of the continental United States8 is 3,026,789 square miles of land and water or 1,973,144,960 acres. Within the confines of this huge area dwell 122,775,046 people.9 The distribution of the population throughout the United States is very uneven, as the following general table of distribution by geographic areas will show.

7 President's Research Committee on Social Trends, op. cit., p. 6.

8 Editor's note: The 48 States and District of Columbia.

9 United States Bureau of the Census, Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930, Population, op. cit., p. 5.

| Geographic divisions | Population 1930 |

Percent of total population |

Land area square miles |

Percent of total land area |

| New England | 8,166,341 | 6.65 | 61,976 | 2.08 |

| Middle Atlantic | 26,260,750 | 21.39 | 100,000 | 3.36 |

| East North Central | 25,297,185 | 20.61 | 245,564 | 8.26 |

| West North Central | 13,296,915 | 10.83 | 510,804 | 17.18 |

| South Atlantic | 15,793,589 | 12.86 | 239,073 | 9.05 |

| East South Central | 9,887,214 | 8.05 | 179,509 | 6.04 |

| West South Central | 12,176,830 | 9.92 | 429,746 | 14.45 |

| Mountain | 3,701,789 | 3.62 | 859,009 | 28.88 |

| Pacific | 8,194,433 | 6.67 | 318,095 | 10.70 |

| Total | 122,775,046 | 100.00 | 2,973,776 | 100.00 |

The New England, Middle Atlantic, and East North Central divisions comprise only a little more than 13 percent of the total land area, but have almost 48.9 percent of the total population of the Nation. At the other extreme are the Mountain and Pacific divisions with 40 percent of the land area and only about 10 percent of the total population.

The Mountain division shows the widest divergence between area and population, including only 3 percent of the total population of the Nation, while comprising 28 percent of the total land area.

The greatest regional density per square mile is in the Middle Atlantic States (262.6 per square mile), with the New England States next (131.8), and the East North Central States third (103.0). The ranking States in density of population per square mile are Rhode Island (644.3 per square mile), New Jersey (537.8), Massachusetts (528.6), Connecticut (333.4), New York (264.2), and Pennsylvania (214.8). The population center is in Indiana, while the geographic center is in Kansas, some 600 miles westward of the center of population.

In the three States of Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont the average density of population per square mile is less than the average density per square mile in the Nation, the heavy concentration of population being in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. In New York State more than one—half of the total population is in one large city (New York City), and in New Jersey the greater portion of the population is in the northern part of the State.

in 1930 only four regions showed a percentage growth in population larger than the percentage growth of the country as a whole, these being the Middle Atlantic, East North Central, West South Central, and Pacific. New England's percentage of growth has been declining since 1900; the Mountain section's since 1910; the West North Central's since 1880; the South Atlantic's since 1900; the East South Central's has declined since 1900, falling to 5.7 percent increase in 1920 and then rising to 11.2 percent in 1930. Only 17 of the 48 States made an increase in growth higher than the percentage of growth for the country as a whole, and only 9 States made as much as 20 percent. increase or more (New York, New Jersey, Michigan, North Carolina, Florida, Texas, Arizona, Oregon, and California). Manufacturing was the determining factor in the increase in four of these (New York, New Jersey, Michigan, and North Carolina); climate was a determining factor in two, and an important factor in two others (Florida and California, Arizona and Oregon, respectively). In Texas the determining factor was probably the expansion of cotton growing and the production of oil. There were 18 of the States in which the growth was less than 10 percent (Delaware, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Virginia, South Carolina, Georgia, Kentucky, Arkansas, Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Montana, and Idaho). Four of these were semi-industrial States, and the remainder agricultural. Montana was the only State which decreased in population.10

10 United States Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930, Population, Vol. 1, op. cit., p. 12.

The chief significance of these factors concerning the geographic distribution of the population is to show where special attention should be concentrated in planning for the reservation of lands and waters, if the people are to have adequate and frequent opportunities for outdoor recreation.

FIGURE 13.

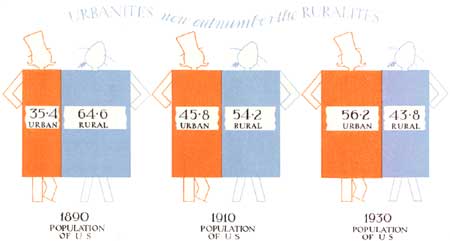

Urban and Rural Trends

In 1930 the urban population was larger by 14,650,220 than in 1920; the rural nonfarm population increased about 3,600,000, while the rural-farm lost approximately 1,200,000. In 1890 the rural population made up 64.6 percent of the total population, while in 1930 it comprised only 43.8 percent. In 1890 the urban population was 35.4 percent of the total population, while in 1930 it was 56.2 percent.

In 32 States the rural-farm population declined, and in 16 States it increased, according to the 1930 census, but in 8 of these 16 States the increase was slight. The tendency toward greater concentration in the larger cities continued. The percentage of the total population living in cities of 500,000 and over rose from 10.7 percent in 1920 to 17.0 percent in 1930; the proportion in cities of 100,000 to 500,000 rose from 8.1 percent to 12.6 percent; in cities of 10,000 to 100,000 from 13 percent to 17.0 percent, while the percentage of the total population living in cities under 10,000 changed only from 8.3 percent to 8.6 percent.11 The larger cities, however, made no growth of population in their older sections, the growth being chiefly in their more open portions, especially near their boundaries. Urban communities in the environs of cities gained much more rapidly in most cases than did the central large city. This indicates a tendency toward decentralization, caused by the desire of the people to escape from congested living conditions, and made possible by improved roads and new methods of transportation, especially by automobile.

11 President's Research Committee on Social Trends, op. cit., p. 12.

FIGURE 14.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Places of Most Rapid Growth.—It is important to emphasize the fact that almost three-fifths of the total population increase occurred in five well-defined groups of cities which had but 26.2 percent of the Nation's population in 1920.12

12 Ibid.

These five groups may be briefly described as follows:

Group 1. The metropolitan districts of the Middle Atlantic seaboard from New York City to Baltimore by way of Philadelphia.

Group 2. The metropolitan districts of the Great Lakes region from Buffalo to Milwaukee. This includes the Akron, Canton, and Youngstown metropolitan districts in Ohio, the Flint district in Michigan, and the Fort Wayne and South Bend districts in Indiana as well as those directly on the lakes.

Group 3. The metropolitan districts in Tennessee, Florida, Alabama, and northern Georgia, together with the cities of 25,000 to 100,000 in North Carolina and Florida.

Group 4. The metropolitan districts from Kansas City to Houston, and cities in Texas of 25,000 to 100,000.

Group 5. The metropolitan districts in the Pacific Coast States, except Spokane in Washington.

The cities in these five groups increased 36.1 percent between 1920 and 1930 compared with a 9.0 percent increase for the remainder of the United States, and 16.9 percent for the metropolitan districts not included in these five groups. They added a total of 10,010,063 to their populations, which is 58.6 percent of the increase of population in the entire United States during the decade just mentioned. Furthermore, over three-fifths of the increase in these five groups of cities is found in the first two which are composed entirely of metropolitan districts and which now have about 27,500,000 people concentrated on 11,962 square miles.13

13 President's Research Committee on Social Trends. Recent Social Trends in the United States, New York, McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1933, 2 vols., tables, charts. (See pp. 15—16.)

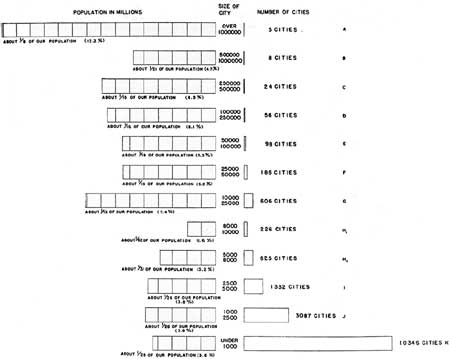

FIGURE 15.

However, this statement does not give a true picture of the actual extent to which the population is gathered on more or less restricted areas of land. In 1930, in addition to the 3,165 incorporated places and towns having each 2,500 or more inhabitants, with a total of 68,954,823 persons, or 56.2 percent of the total population, there were 13,433 incorporated places having each under 2,500 inhabitants with a total population of 9,183,453, or 7.4 percent of the total population of the Nation. These latter places are classed as rural,14 but not infrequently from the viewpoint of congestion on small areas many such communities present true urban conditions. Including these 13,433 incorporated places with the areas technically classed as urban there was a total (1930) of 78,138,276 inhabitants, or 63.7 percent of the entire population, living on more or less restricted areas of land.

14 United States Bureau of the Census, op. cit., 1930, Population, Vol. 1 (See p. 7).

| Group | Number of cities | Land area (acres) |

| Group I—500,000 and over | 13 | 1,046,559.9 |

| Group II—300,000 to 500,000 | 12 | 471,533.3 |

| Group III—100,000 to 300,000 | 69 | 1,271,432.3 |

| Group IV—50,000 to 100,000 | 95 | 698,991.8 |

| Group V—30,000 to 50,000 | 121 | 856,320.0 |

| Total | 310 | 4,344,837.3 |

The total population of the cities in these five groups is 47,395,009 (1930), or approximately 38 per cent of the total population of the Nation. A total of 47,395,009 people is crowded on two-tenths of 1 per cent of the total land area of the United States. In reality they occupy much less space than this, for seldom is the entire land area within the boundaries of cities fully utilized for any purpose. The average density of population is 10.9 per acre.

Cities of sufficient size may be expected to plan, acquire, and develop sufficient areas for recreation, and to operate a recreational system on a year-round basis. In this group should be included all cities of 10,000 population and over. The following table shows the number of such cities, according to geographic divisions, and the total population in the cities of each division.

| Geographic division | Number of cities | Population |

| New England | 133 | 5,699,915 |

| Middle Atlantic | 238 | 17,997,318 |

| East North Central | 218 | 14,599,766 |

| West North Central | 89 | 4,372,334 |

| South Atlantic | 91 | 4,551,186 |

| East South Central | 48 | 2,121,353 |

| West South Central | 68 | 3,234,019 |

| Mountain | 27 | 967,148 |

| Pacific | 70 | 4,797,038 |

| Total | 982 | 58,340,077 |

The total population of the above cities was 47.5 percent of the total population of the Nation in 1930; this has probably increased slightly since that time.

Many cities in the group from 8,000 to 10,000 may find it possible to provide the necessary open spaces for recreation and to operate a year-round recreational system. The number of cities in this group is 226 and the total population is 1,993,375. The combined population of all cities of 8,000 and above is 60,333,452, or 49.1 percent of the total population of the Nation (1930).

The following groups of incorporated urban and rural communities may be expected to provide and maintain certain types of areas for recreation, but they cannot be expected, for financial reasons, actually to operate a recreational service the year round.

| Groups | Number | Population |

| Cities from 5,000 to 8,000 | 625 | 3,903,781 |

| Cities from 2,500 to 5,000 | 1,332 | 4,717,590 |

| Rural from 1,000 to 2,500 | 3,087 | 4,820,707 |

| Rural from 1,900 and tinder | 10,346 | 4,362,746 |

| Total | 15,390 | 17,804,824 |

In general the population in these urban and rural incorporated communities will have to rely on some type of administrative unit larger than themselves for year-round, programmed recreational service. The same may be said of the 44,636,770 people outside incorporated places. Such an administrative unit may be a county, or a metropolitan district, or some other type of administrative unit yet to be devised.

Occupational Trends

Occupational shifts.—Recreational needs and requirements during the past 60 years (1870—1930) have been profoundly affected by occupational changes. There has been a tremendous shift of the population from agricultural and allied occupations to industrial, commercial, clerical, and professional occupations. In 1870 more than half (52.8 percent) of the gainfully employed persons, exclusive of children, were found in agriculture, lumbering, and fishing, but in 1930 only 21.3 per cent of all gainfully employed persons 12 years of age and over were so employed. On the other hand those engaged in manufacturing and mechanical industries rose from 22 percent in 1870 to 28.6 percent in 1930. Trade and transportation employment rose from 9.1 percent in 1870 to 20.7 percent in 1930. Clerical employment rose from 1.7 percent in 1870 to 8.2 percent in 1930.

These occupational changes are coincident with the rise of industrialism and the growth of cities.

The recreational significance of this change lies in the fact that many millions of people were drawn from an environment in the open country which was more or less in harmony with the biological and physiological needs of man to an unnatural, artificial environment. This entailed crowded living on limited areas of land on which the natural conditions had been destroyed, and necessitated working indoors in factories, shops, stores, offices, etc., without adequate opportunities for contact with the soil and growing things, or for outdoor activities in the open air and sunlight. This condition gave rise to the idea of public responsibility for trying to bring about an adjustment between nature and man, out of which came the modern provisions in cities and their environs for playgrounds, playfields, small and large parks, and other types of recreational areas.

Increase of leisure time.—Another significant change is the decline in the employment of children in gainful occupations, especially in very recent years. In 1890, 18 percent of all children from 10 to 15 years, inclusive, were gainfully employed; in 1930 only 4.7 percent of this same class were gainfully employed.

While some of the free time of the children and young people is taken up by the increased attendance at schools and colleges, and children on the farms still have traditional chores and some real work to do, children and young people in the cities have an unprecedented amount of free time on their hands. As their attendance at school usually occupies about 6 hours a day for only 5 days a week, and as their yearly attendance is approximately only 180 days, most of them find a great deal of leisure time at their disposal. It be hooves the public to provide for them attractive and adequate recreational facilities so that this time may be utilized wisely and beneficially, rather than be left to them to make, in many cases, foolish or harmful disposition of it.

It seems certain that continued development of labor saving devices and scientific management will further reduce the opportunities for steady employment for very large numbers of people in the United States, unless the hours of labor are still further shortened; new products desired by the people may give rise to new industries, and foreign commerce may again be brought to a flourishing condition. There has been a steady decline since 1910 in the percentage of males in all age groups gainfully employed, the greatest decline being in the age group from 10 to 15 years, inclusive, and the next greatest in the age group 65 years and over. On the other hand, among the women 16 to 45 years, the 1930 census showed an increase in the percentage gainfully employed. Among the females there was a sharp decline in the percentage of children from 10 to 15 years gainfully employed, and a slight decrease in the percentage of employment of women over 65 years.

The cutting off of opportunities to be gainfully employed will likely affect more and more the children, young people, and older people of both sexes, and there will be a possible decline in the numbers of women gainfully employed at the height of their productive capacity. In between these two extreme age groups there will be a group of gainfully employed persons working shorter hours than formerly. This creates an unprecedented situation with respect to the amount of leisure in possession of the people, demanding broad-gage and farsighted planning for its use, especially on the part of public authorities. In addition to planning for the use of leisure recreationally, it would appear highly desirable to devise ways and means of using as much as possible of this "enforced" leisure in various forms of public service, as is being done now through the Civilian Conservation Corps and in developing home handicraft arts.

3. GEOGRAPHY OF RECREATION

Like all other natural resources, recreational resources exist where Nature has scattered them in careless abandon, and without any orderly relationship to human demand. When they are favorably situated with reference to populations, it can only be considered a matter of fortunate accident. Moreover, since the industry of man is definitely detrimental to those recreational resources whose principal value lies in their wilderness character, recreational areas of this particular type are nearly always remote from centers of human concentration.

Because the everyday outdoor recreational needs of the people must be met by facilities which are immediately at hand, large expenditures are constantly being made within city and metropolitan district boundaries for the purpose of restoring, at least to a semblance of natural character, areas whose natural recreation facilities have been spoiled by human activities.

It is well to note that even within a city the selection of recreational areas is governed to a large degree by topography. Natural ponds and lakes, the depressions occupied by streams, and the more rugged hilltops are areas whose natural characteristics give them preferred recreational value. Fortunately, such sites are frequently of minor value as real estate developments.

Geographical factors, more than anything else perhaps, are responsible for the element of Federal responsibility for recreation. Scenic, climatic, and wildlife resources do not recognize the boundaries of political subdivisions. Where use of these resources is had by all of the people, the Federal Government has the responsibility of safeguarding them. Recreational planning cannot be successful unless it takes into account the discrepancy between the distribution of populations and recreational resources.

Population—its nature and the pattern of its distribution—is of the greatest importance in locating areas which are to be devoted partly or wholly to recreation. A "counter pull" is exerted by a group of natural factors, some of which are almost generally given consideration, some of which are more often than not quite neglected. The very existence of these natural factors and their "pull" are inconsistent with the idea that there should, or ever could, be a more or less fixed pattern of distribution of the areas and facilities which people desire for their leisure time use. These factors, all of which need to be weighed against population distribution in the selection of parks and other recreational areas, appear to be as follows:

Land Reliefs

Variety of elevation is one of the important determinants in recreational value of land. Park folk in their search for recreational locations instinctively look for areas which possess this quality. Moreover, persons planning vacation trips are prone to seek locations whose altitudes are opposite from those of their home environments. Change of environment, as is well known, is in itself a recreational factor of the greatest importance. The altitude factor enters here with a special emphasis, because of the physical refreshment which most people experience from a change of environment of this particular sort.

The accompanying relief map of the United States (fig. 16) shows clearly the distribution of the principal mountain ranges of the country. It. emphasizes the fact that the majority are located in the western part of the country. Comparison of this map with the map (p. 26) of present and proposed Federal park areas demonstrates how variety of land relief has been a determinant in the selection of a majority of the national parks.

FIGURE 16.—Relief map of the United States.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Monotony is anathema to recreation. The maximum varieties of scenic interest are to be found in the rugged areas, whereas the plains only provide minor variations of the one scenic theme. All of a plain is usually within one life zone, whereas mountain ranges frequently include as many as five life zones. Thus, topographical variety brings a variety of flora and fauna. There are many other points which could be brought out to illustrate the importance of land relief in the recreational picture, but this hardly is necessary, since the recreational values of the mountains are universally recognized. Rugged areas are high in recreational value, but as a general thing they are remote from large population centers.

FIGURE 17.

Water Resources

Water resources—lakes, streams, waterfalls, bays, and oceans—are factors of the utmost significance in the scheme of recreation, both because they contribute beauty to any outdoor scene and because of their high value for active recreation.

First of all, it should be borne in mind that lands which do not have a sufficient supply of water have a low recreation-acre value, just as they have a low forage-acre value. Whereas the great desert areas of the Southwest have very real recreational value, recreational use is necessarily concentrated in a relatively small number of centers, and many thousands of intervening square miles forever must remain unoccupied.

Detailed discussion of the various forms of active recreation which are dependent upon the presence of water resources is not necessary here. This value, for example, has been recognized by New York, which has gone so far in setting up standards in selection of State parks as to make water recreational facilities, either actual or potential, a primary requisite. On almost every recreational area the greatest concentration of use occurs in the immediate vicinity of the water, and movement away from the water courses ordinarily takes the form of excursions of relatively short duration.

Sea coasts have a recreational value of unique and matchless character. The recreational value of beaches is of the highest order for several obvious reasons. The inspirational element is of such compelling order that even persons who are not ordinarily stirred by manifestations of nature, experience a stir of emotion when they come upon the shores of the ocean. It is also true that concentrated use of beaches does not shut nature out. Such intensive use of other types of recreational areas destroys the feeling of intimate contact with nature. It is fortunate, too, that intensive use of beaches does not destroy their natural character. Thousands of persons tread the sands and the next high tide effaces every evidence of their tracks.

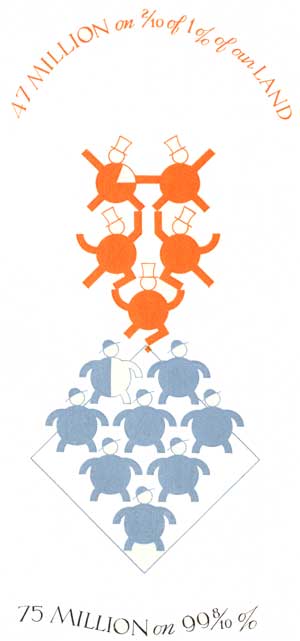

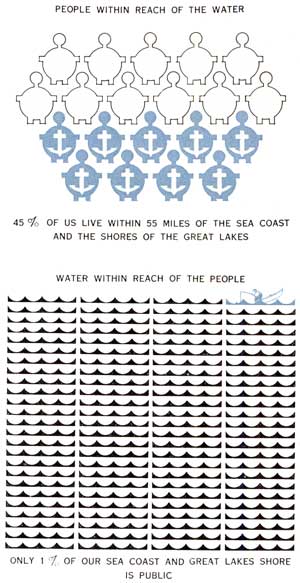

Twenty-one of the 48 States have ocean frontage, and the total length of the general seacoast of continental United States is approximately 5,000 miles.

A comparatively small portion of seacoast is now in public ownership for recreational use, and this field. should be enlarged and developed.

The general coast line of the United States and outlying territories is as follows:

| Miles | |

| Continental United States | 4,883 |

| Alaska | 6,640 |

| Puerto Rico | 311 |

| Hawaiian Islands | 775 |

| Panama Canal Zone | 20 |

| United States Samoan Islands | 76 |

| Total | 12,705 |

(The above tabulation excludes the sea coast of the Philippine Islands, and does not include the Virgin Islands.)1

1 U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, Lengths, in Statute Miles of the General Coast Line and Tidal Shore Line of the United States and Outlying Territories, November 1915. (See p. 22.)

The total length of tidal shore line of the continental United States, measured by a unit 1 mile long, and including the shore line of those bodies of tidal waters more than 1 mile wide, which lie close to the main waters, is 21,862 miles (continental United States, 11,936; islands of the continental United States, 9,926).

The beaches are one fortunate instance of a recreational resource which is to be found in proximity to the centers of human demand. Forty-five percent of the total population, or 55 million persons, live within 55 miles of the sea coasts and Great Lakes.

Climates

It is axiomatic that pleasurable outdoor recreational experiences require favorable climatic conditions, inasmuch as there is no recreation without enjoyment, and no one, except perhaps the eccentric, enjoys himself in an atmosphere of physical discomfort. Climates have a still more positive place in the recreation picture for the reason that the principal motive of many recreational outings is the search for a pleasurable climate.

Rainfall.—Rainfall is a climatic factor which affects and in many cases definitely determines the seasonal value of certain regions for recreational use. For example, in the coastal section of the Pacific Northwest, the recreational advantages of relatively mild temperatures during the winter months are offset by the heavy and often long-continued rainfall which that region normally receives during the same months. On the other hand, light rainfall in the summer is a factor in making this section one of the most delightful outdoor recreational areas in America; and light rainfall, during the winter months, contributes much to the outdoor recreational popularity of southern California, the Southwest, and Florida.

From the accompanying map (fig. 18), prepared by the United States Weather Bureau, which shows the range of average annual precipitation, it will be noted that 8 percent of the land area of the United States has a rainfall of less than 10 inches per year. This includes the great deserts of the United States. Many of these areas are warm during the winter months, have a high percentage of sunshine, and offer exceptional recreational possibilities during that season. Some of them may also be suitable for recreation during the summer months.

FIGURE 18.

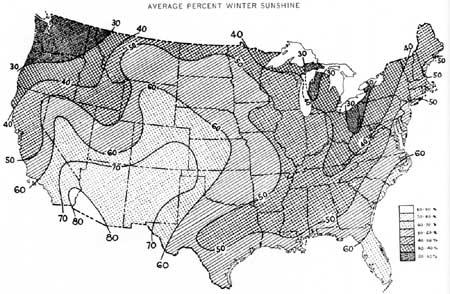

Sunshine.—Areas having a high percentage of sunshine in the winter months are particularly attractive for recreational purposes. In the United States the winter sunshine regions are remote from the centers of greatest population density. This is most significant because it means that the majority of our people cannot reach this salutary sunshine at the time of year when it is most needed for good health.

The accompanying map of the United States (fig. 19), published by the United States Weather Bureau, shows the actual amount of sunshine expressed as a percentage of the total possible sunshine for the winter months. It will be noted that portions of Arizona. and southern California receive from 80 to 90 percent of their total possible sunshine for this period. Any area having 60 percent or more sunshine may be considered as possessing an important factor, which in conjunction with other advantages, will determine its popularity and desirability for winter recreational uses in the United States.

FIGURE 19.

Humidity.—Humidity plays a large part in determining the recreational desirability of certain regions. High humidity, much more than high temperatures, is responsible for the fact that the Chesapeake Bay region is not an ideal summer recreational area. Low humidity makes an important contribution to the winter recreational advantages of such regions as the Southwest.

The principal low humidity regions are the Southwest and the Great Basin regions. Although their dry atmospheres make them valuable as health and recreation areas, they are unavailable to the majority of the citizens of the United States because of their remoteness from heavily populated zones.

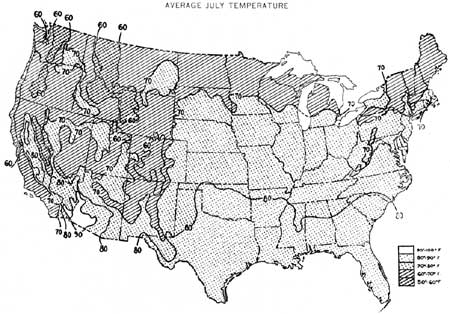

Temperature.—Temperature is an important factor in the geography of recreation. Generally, high temperatures are an adverse factor in summer and a favorable one in winter. Temperature exerts a pull of sufficient strength to cause many millions of miles of tourist travel every year.

Popularity of mountain areas in the summer, and of the southern areas in the winter, is determined largely by the relatively low summer temperatures of the former and the comparatively high winter temperatures of the latter.

The summer season is the period of the year during which the greater part of the people seek outdoor recreation. This is true not only of the more extended vacation period, but also of the shorter week-end vacations and Saturday half holidays. Summer evenings offer abundant opportunities for outdoor recreation, whereas the winter evenings, usually, must be spent indoors.

The average July temperatures of the country are shown on the accompanying map (fig. 20). Average temperatures for this month, ranging from 90° to 100°, are found in the vicinity of the lower portion of the Colorado River in Arizona and in southeastern California. A large area in the Southern States has average July temperatures ranging from 80° to 90°. In general, this temperature is too high for comfort, and people of that region will seek cooler areas for their vacation grounds. Most of the Eastern and Central States have average July temperatures ranging from 70° to 80°. For people in this area also regions of lower temperatures are desirable for summer vacations.

FIGURE 20.

This map also shows the areas of the United States having average July temperatures of 60° to 70°. In this classification come the Northern New England States, much of New York State, areas in the Appalachian Mountains, the tier of northern States from Michigan westward, and large areas in the Western States.

For summer recreation grounds those areas having July temperatures averaging between 50° and 60° are at a high premium. These areas occur throughout the Rocky Mountains, the Sierra Nevada, and the Cascade Range.

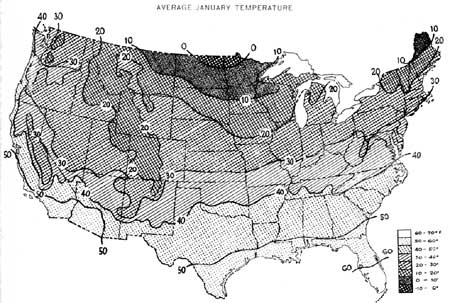

The accompanying map of the United States (fig. 21) published by the United States Weather Bureau, shows average January temperatures. It will be noted that in a small area of the North Central United States average January temperatures below zero are found. Less severe temperatures occur southward from this area.

Winter sports are at their best in areas of heavy snowfall combined with moderately, but not bitterly, cold weather. Extremely low temperatures militate against the recreational desirability—for winter sports—of many northerly regions.

FIGURE 20.

Many people seek winter recreational grounds in the warmest areas that are accessible to them. It will be noted that all of the Gulf States, southern California, and Arizona contain areas where the average January temperature is between 50° and 60°. These States offer great recreational attractions in the winter to the people of the colder, Northern States. The southern half of the Florida Peninsula has an average January temperature of 60° to 70°, and is, therefore, a great winter recreational ground, convenient to the densely populated areas of the Eastern States.

Unfortunately, the regions of densest population, with only limited recreational resources available, have unfavorable summer and winter temperatures. Those who would seek cool summers and warm winters must travel great distances. The individual who does not have the time and money must forego long trips and endure discomfort, or at best seek such relief as is locally available.

Flora and Fauna

Flora and fauna provide the living interest without which no area is recreationally complete. Assume an area—if such a thing were possible—which is recreationally complete as to topography, water resources, and climatic factors, but which is without plant and animal life, and then judge the value of this area as a recreation ground. The mental picture created gives a plain answer to the question implied.

Though the importance of flora to a park area is abundantly recognized in the effort and money which are expended for the purpose of establishing and maintaining the floral elements of city parks, there is frequently evidenced a paradoxical disregard of the floral constituents of outlying parks whose chief value lies in their unspoiled condition. Yet of the two types, the natural flora is the most sensitive and the most difficult to restore when it has been abused.

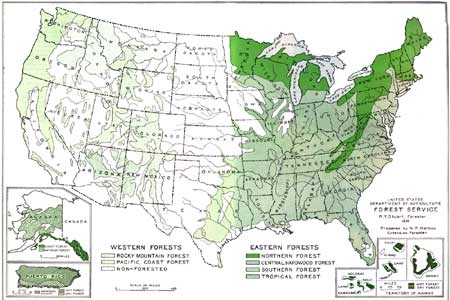

(click on image for a PDF enlargement)

Forests.—Forests and wooded areas provide great opportunity for recreational use. They offer cool, shady retreats for escape from summer heat. Birds and game animals are abundant in these vicinities. Woods enrich scenic values and have a rich botanic interest.

The forest regions of the United States may be divided into the following principal groups:

Eastern forests.

Northern forest.

Central hardwood forest.

Southern forest.

Tropical forest.

Western forests.

Rocky Mountain forest.

Pacific coast forest.

The presence of some forest growth is almost as basic, and as widely recognized, an element in selection of land for recreational use as topographic variety, water, and favorable climate. Fortunately for the task of providing recreation for the densely populated Atlantic coast and Great Lakes sections, these are regions of persistent and luxurious tree growth. Where tree growth is abundant, areas of relatively small size may still have a high recreational use value. A 20-acre tract of eastern hardwoods would make a valuable recreational area, whereas an average 20-acre tract in the treeless plains and desert regions of the West would, in all likelihood, be a useless recreational unit. In the city of Washington, for instance, there are hundreds of vacant lots which have a real recreational value because of the trees which flourish on them.

Plant Life in General.—The value of attractive vegetative covering is too well known to need detailed discussion. In addition to the aesthetic enjoyment arising from colorful wild flower displays and the restful effects of green vegetation of all forms, much entertainment is had by those who sojourn in the woods to gather edible berries and nuts, pick mushrooms, and so on.

Certain vegetative types have exceptional recreational value because of their unique characteristics. Notable among these are the cacti of the southern deserts, and the interesting plant inhabitants of the southern swamps.

Fauna.—In the geography of recreation, the variety, abundance, and distribution of fauna are important factors. For consideration here it is useful to consider the large and small forms of wildlife separately.

Small birds and mammals, originally widely distributed, have in general maintained their populations very well in the face of pressure of civilization. Many of them, in fact, particularly birds, have profited by the environmental changes which man has induced. Los Angeles, Calif., for instance, is abundant in bird life, because of the extensive garden developments, and the presence of these birds adds materially to the recreational values which are to be found today within the limits of the city proper. On the negative side there are a few of the smaller species which are destructive of recreational values. In the city of Alameda, Calif., alarm clocks were resorted to in an effort to disperse an objectionable colony of black crowned night herons. In the city of Washington toy balloons are the current weapon in a campaign against starlings. On the whole, however, it must be recognized that the smaller forms of native wildlife, particularly the birds, add materially to the value of the smallest recreational area, such as a downtown park or residence garden.

The larger wildlife species, including big game, require large areas of their native habitat, if they are to survive. There is no big game or wildlife area in this country which is free from the cumulative encroachments of agriculture, the persistent pressure of hunters and trappers, and the combined voices of special interests. Therefore, wildlife reservations must be established, and wildlife management practiced where wildlife can exist, regardless of local pressure or remoteness from centers of population.

Hunting is of great recreational importance. The lack of quarry to hunt would be a tremendous loss. Big game in the United States today is largely restricted to the Western States, and to the Territory of Alaska.

Fishing is one of the leading, if not the greatest, of American outdoor recreational activities. In the past the best fishing has been found in the most remote places, and this condition is likely to continue for some time to come, in spite of the remarkable improvements in fish cultural methods and the increasing extent to which they are being applied.

Thus, it may be seen that wildlife is another of the recreational factors which exerts a "pull" on population.

Conclusions

While all of these factors have an important bearing on recreation from a national viewpoint, they have an equally important recreation significance considered from a regional, State, county, or metropolitan viewpoint, the principal difference being that the range of choice progressively decreases as the area under consideration is contracted. Other things being equal, that area, whether national park, regional park, State park, or metropolitan park, which has favorable natural factors of the highest order available within the area to be served, will exert the strongest "pull" and will tend to the greatest extent to refute the validity of any scheme which is based on a regular pattern of distribution.

Mentally superimposing upon one another these maps showing relief, forest types, temperatures, precipitation, etc., and viewing the result in the light of the principles of administrative responsibility, we are led to several conclusions:

1. That there is a seasonal shifting in the utilization of recreational areas.

2. That the centers of population and the recreational areas (i. e., those with a congenial interplay of natural factors) seldom coincide.

3. That this lack of coincidence of recreational needs with natural recreational resources, coupled with the seasonal shifting in the utility of these resources, indicates the desirability of a national husbanding of recreational resources. In other words, the "migratory" character of these recreational resources makes them the property of the Nation, and strongly indicates that there should be a national recreational system.

4. HISTORIC SITES AND RECREATION

The relationship of historic sites to a general report on recreation becomes clear when it is realized that at present there are 600 or more historic and archeological sites merged more or less completely into existing Federal, State, local, and private recreational systems. Public holdings embrace sites covering all periods of American development, and contain extensive archeological remains, including many in the Southwest. Among the more notable historic sites are colonial homes, Revolutionary battlefields, sites associated with the lives of Washington, Lincoln, and other famous men, battlefields of the Civil War, besides reminders of our more recent history. In the various State park systems, and grouped as public holdings, are approximately 200 historical and archeological sites, scattered through 30 States. Of varying sizes and types, these areas include Indian remains, sites of battles with Indians, early French and Spanish forts and missions, colonial houses and forts, battlefields of the American Revolution, many early log structures, pioneer sites, and other remains connected with the westward development of the country, homes of individuals famous in American history, and other memorials.

Besides the public holdings, summarized above, there are numerous historical and archeological sites of genuine and widespread recreational interest owned by semi-public or private historical organizations and societies, or by individuals, but open to the public. These holdings include a great many historic houses, besides Indian mound sites, farm plantations, and even complete villages, dotting the country from Maine to California. Most of these have been developed in the past 40 years, and the greater proportion in the past 15. Drawing hundreds of thousands of visitors every year, these Federal, State, and local holdings form an important element of national recreational resources and the national recreational program.

Besides the problem of planning for the best use of existing park facilities, development of land and water use on a broadly planned scale raises the question of preserving historic and archeological sites which are at present unprotected.

In the midst of the great changes now affecting our national social and economic structure, it is easy to destroy undeveloped historic and archeological sites without giving full consideration to their importance. Industrialization, urbanization, movements of population, regional planning, electrification, housing programs these can easily crush, in their onward way, the fragile, and irreplaceable symbols which tie us to the past, and which we may later wish we had preserved. In the development of a great river valley, in its electrification, in the migrations necessitated by demand for a balance between agriculture and industry, there is a tendency, more local than national, to demand the destruction of old buildings and ancient remains, in order "to clear the way for the future." Old log cabins, a dilapidated southern plantation home, an Indian mound, as characteristic in their way as an old castle along the Rhine, may appear to the persons directly charged with carrying out a broad social plan to stand in the way of progress. But actually such buildings may be an invaluable national asset, as real as a hundred square miles of forest, and more completely irreplaceable when lost. Such structures provide us with a feeling of continuity in our development, they recall to our minds our most valuable traditions, such as pioneer courage or the generous social impulses of the South; they give us faith in our ancestry; and they provide us with visible symbols of the long, steady progression of our civilization.

In a general program which looks toward widespread physical changes in land and water use, attention should be given to the protection and preservation of important historical and archeological remains during the process.

With regard to matters of population, it should be noted that there is a relatively close correlation between the distribution of historic sites and the distribution of population. This fact possesses a double significance. The growth of population, with the resulting urbanization and industrialization, is likely to result in an undiscriminating destruction of everything old, unless legislation is enacted, as in European countries, to prevent it. Secondly, since historic sites are often already close to large bodies of population, they are in a position to furnish a natural and inspiring form of recreation amid education without involving the necessity of leaving the population areas.

There is likewise a close relationship between geography and history, the former having in one sense laid a natural basis for the great main line of American development. The location of our historic cities, the population in our fertile valleys, the sites of the battles on American soil are to be explained largely in terms of geography. The great natural highways and avenues of communication throughout America are likewise often the historic routes—the Cumberland Gap roads, and the Hudson Valley and Ohio Valley routes, for example. In American development, historic and geographic elements have become intermingled.

Historic sites fill an essential social need, and it follows from this that a program regarding them is a public responsibility. Our American historic sites are among the most important tangible symbols of our unity as a Nation. From California to Maine and from Texas to Michigan we have a common cultural and social interest in our background, in the events that made our Nation, in the great experiences of the Revolution and the Civil War. Symbolized in such places as Yorktown, Gettysburg, and Abraham Lincoln's birthplace, this common national history forms perhaps our strongest single social bond. Furthermore, historic sites help to nourish our national traditions out of which much of culture comes. The pioneering outlook of the West, the social generosity of the South, the civic strength of New England, are among the most important social resources of America. To allow the historic buildings and sites which embody these traditions to fall away from neglect is to nullify the physical evidences of the best productive labors of our forefathers. Especially to people in great cities, where crowding populations and industrial ugliness are strong, contact with the survivals of an earlier America brings "an invaluable corrective to their mental and imaginative outlook." To insure the accomplishment of this by some agency, public or private, is an essential duty of government.

Historical and Archeological Sites

The growing demand for a more comprehensive program to preserve important buildings and sites connected with our national past is largely the result of a new appreciation on the part of the American people of the value of their historical heritage.

The significant cultural and social values of the physical remains relating to our past history are becoming increasingly apparent as various public and private agencies accept the responsibility for their controlled development, preservation, and educational use. Thus, by working with such areas, as well as by surveying and studying other historical sites and remains in every part of the Nation, the controlling agencies have been able to develop much information relating to the preservation and use of the physical elements of history.

Among these agencies the National Park Service, through its developing program and through the American historic buildings and the historic sites surveys, has contributed much information relating to the problem and may be expected to contribute more. Not the least in the results of these varied activities has been their value in arousing public concern for the preservation of the national historical heritage.

Among the further evidences of this growing national interest in a broadly based preservation policy is the growing appreciation of America's own past, as seen in the individual site. We are becoming increasingly aware, for example, that the log cabins of Boonesborough, the Emerson, Longfellow, and Whittier homes in Massachusetts, the Hermitage in Nashville, the frontier settlements along inland waterways and forts along the Oregon and Santa Fe Trails, are American counterparts to historic remains in Europe. These American buildings and sites are coming to mean to our own people what the ruins of Rome mean to the Italian people, Stratford-on-Avon to the English, or the baronial castles along the Rhine to the Germans. But even though much interest has been aroused and much knowledge accumulated through experience in administering historic sites, as well as in surveying problems not yet properly controlled, it is likely that as a nation we have only begun to appreciate the tremendous possibilities which may be realized through the wise utilization of important sites. To teach the broad cultural significance of these resources, and to see that some agency, whether Federal, State, or local, preserves the most important of them, is a matter of public responsibility.

Among the almost innumerable examples which might be cited, one notes important Indian mounds in the Tennessee, Ohio, and Mississippi Valleys gradually eroding from the effects of weather and the plow, as well as archeological remains undergoing other forms of destruction. Often these remains are handled so improperly that their true significance is lost sight of in bizarre methods of public exploitation.

PHOTO 1.—Whitley's Mill, Mecklenburg County, N. C. |

PHOTO 2.—The Shamrock (Porterfield residence), Vicksburg, Miss. This fine old home with its high basement story and unpedimented two-story portico is typical of a class of houses fast disappearing from the deep South. |

Moreover, numerous fine examples of the early architecture of this country have been abandoned to the ravages of time. Only in rare instances are efforts being made by worthy individuals and societies to preserve these evidences of our cultural growth. Among important buildings suffering from neglect we find such examples as The Shirley-Eustis House, Roxbury, Mass.; Santee near Corbin, Va.; and Belle Grove at White Castle, La.

Earthworks from the Revolutionary and Civil War periods in many States have been destroyed by erosion, or are in a state of ruin and neglect, as those at Harrison's Landing in Virginia, at Kenesaw Mountain in Georgia, and at Corinth in Mississippi.

In Washington, D. C., many houses rich in history and interest have not been preserved. The reconstruction of the capital city has been responsible for many historical casualties, such as the National Hotel, the old Harvey House, the home of John Quincy Adams and numerous ancient boarding houses with which were associated famous names in American history.

One aim of the Federal survey of historic sites now under way is to gather careful data and provide recommendations concerning legislation for general conservation of historical remains, as well as for the care of specific sites. The valuable, though sporadic, efforts of individuals, private groups, and even some of the States are not enough to prevent an irreparable historic and artistic loss to America. The Federal Government must assume its share of the responsibility in this problem, both in education and, where necessary, in control.

In regard to possibilities for a broad preservation program not necessarily involving direct Federal control, it may be pointed out that the most important general and basic legislation regarding historic and archeological sites in the United States is the act for the preservation of American antiquities, 1906, confirmed in purpose by the National Park Act of 1916. These acts provide only the barest legislative protection for areas already a part of the public domain and, with regard to those areas not at present public property, provide practically no protection at all.

In this connection, it may be observed that data from other countries regarding this general problem are growing, and are being made available through the International Commission on Historic Monuments.

The present status of legislation in other countries, for example in France, is indicated by the fact that, though a historic or artistic building may remain in private hands, the owner in many cases is not allowed to change or destroy it without permission from the National Government. Legislation of similar import obtains in other countries, including England and Mexico. In this regard, attention may be drawn to the conclusions of an international conference held at Athens regarding the development of the plan for the International Commission on Historic Monuments. The following is quoted from the conference report:

It unanimously approved the general tendency which, in this connection, recognizes a certain right of the community in regard to private ownership.

It is noted that the differences existing between these legislative measures, were due to the difficulty of reconciling public law with the rights of individuals.

Consequently, while approving the general tendency of these measures the conference is of the opinion that they should be in keeping with local circumstances and with the trend of public opinion so that the least possible opposition may be encountered, due to allowance being made for the sacrifice which the owners of property may be called upon to make in the general interest.

It recommends that the public authorities in each country be empowered to take conservatory measures in cases of emergency.

It earnestly hopes that the international museums office will publish a repertory and a comparative table of the legislative measures in force in the different countries and that this information will be kept up to date.1

1 Institut International de Cooperation Intellectuelle, La Conservation des Monuments d'Art et d'Historie, Société des Nations; Les Dossiers de l'Office International des Musées. Geneva, 1931. pp. 18—19.

The statements of this conference, similar data available through this and other international commissions, and the conclusions of other studies and surveys now going forward under the auspices of the National Park Service are providing the basis upon which it is expected that general recommendations for legislation to preserve historic sites will be made.

PHOTO 3.—Memorial mansion and grounds at George Washington's birthplace, Westmoreland County, Va. |

PHOTO 4.—Earthworks at Battery No, 5, Petersburg National Military Park, Va. |

From similar origins has grown a considerable body of principles and techniques relating to problems of preservation and restoration of historic remains. In the course of its experience in developing historic sites under the various emergency programs, the Federal Government has brought to bear upon its problems the special knowledge of experts in various fields. These include, among others, special engineering, architectural, landscape, and even forestry techniques applied particularly in the development of the historic sites and remains now in the possession of the Federal Government, such as Gettysburg, Yorktown, and Vicksburg. There is an ever-increasing skill in the application of these techniques in the field of history.

In another way, a growing appreciation of this developing method and technical skill in the preservation of historical remains and of the significance of these historical remains for the scholarly world has resulted in the growth of a closer liaison between the Historical Division of the National Park Service and the joint committee on materials for research of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council. This joint committee, which was originally developed to conserve the interests of scholars in research materials, and in methods and techniques relating to them, is working in close cooperation with the National Park Service on these problems as applied to historical remains.

The various elements in this developing program come naturally together at this point. The activities of the Federal Government in conducting surveys of historic buildings and sites, its extensive experience with the historical values involved in specific sites already under Federal control, and its developing contact, through the International Commission on Historic Monuments, with the historic sites problem as viewed in other countries have laid the basis for an enlarged national program, including comprehensive legislation for the preservation of historic sites in America. Although the ultimate plans and policies which may finally be developed are not as yet ready for formulation in this report, certain principles applicable to problems of national planning are already clearly evident.

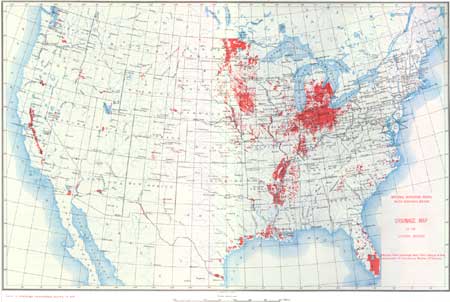

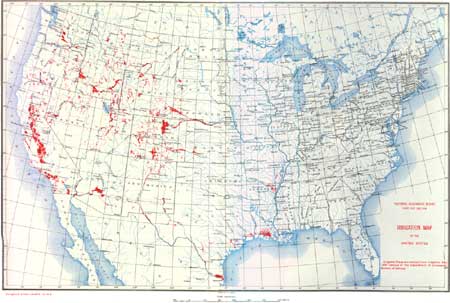

5. SOME COMPETITORS OF RECREATIONAL LAND USE

Perhaps because recreation is more than just pleasurable physical exercise, perhaps because it partakes of the freedom of open country, the "competitors" which logically come to mind are those which directly affect the attractiveness of the open country. Some of these are: Private consumption of recreational resources, water pollution, lumbering, grazing, drainage, and artificial stream control.

Private Consumption of Recreational Resources

The common desire to own a small segment of forested lake front or stream side for a summer home or resort is rapidly leading toward the exhaustion of this waterfront resource, insofar as its availability to the great portion of our population is concerned. The desirable and habitable areas can be quickly consumed by a relatively small proportion of the population. It is, of course, true that great recreational value may accrue to the occupants of such retreats, but the question arises: Is this luxurious and extravagant utilization of a limited resource the wisest use? When every choice lake front, stream side, and beach is taken by private homes, clubs, stores, amusement devices, and exclusive resorts, will the common demand for outdoor living have been satisfied? It is not probable.

Unnoticeable, at first, is the fact that some summer homes, dude ranches, and resorts occupy the strategic points which actually control the much larger hinterland. The wilderness—whether pristine or greatly modified—is an organism. For example, if the stream banks, lake shores, and springs are taken by a relatively few residents, the whole area is, in effect, taken. Likewise, if a summer home is located at the mouth of a precipitous and scenic canyon or secluded mountain valley, the use of the entire canyon or valley is, in effect, preempted by the one holder, his family, and guests.

Examples of this sort of private consumption are to be found among the resort and summer-home colonies at Grand Lake and around Estes Park, Colo.; Lake Quinault and Lake Crescent, Wash.; some of the dude ranches of Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, and Colorado; and, in general, in the numerous strategically located private holdings around almost every lake in the East.

Let us take a specific example. At the south end of Grand Teton National Park lies Phelps Lake—an unusually picturesque lake at the mouth of a precipitous gorge which cuts back into the Tetons. The trail to this section of the mountain hinterland leads up the gorge behind the lake. Until 1932 a private ranch controlled the lake. A mile away from the lake the public was halted by a fence and a "no trespass" sign which could only be hurdled at the price of $10 a day. This one ranch, then, not only consumed a beautiful lake and mountain setting but also controlled hundreds of square miles of superb mountain hinterland. This same case could have been repeated at numerous places along the base of the Tetons; in fact, this type of wilderness utilization would have had the mountain range completely locked and closed, except to a few people, had it not been for the establishment of Grand Teton National Park and the subsequent efforts of the Snake River Land Co.

The location of such privately owned recreational facilities frequently limits the use of vast recreational resources to a comparatively few individuals. Such is the manner in which large portions of this type of recreational resource are being dissipated. It is submitted, therefore, that the policy of permitting summer-home and resort sites within public lands of recreational value should be carefully reconsidered to the end that a more equitable and sustained use of the resource may be attained.

Water Pollution