|

National Park Service

Recreational Use of Land in the United States |

|

SECTION III. PRESENT EXTENT AND USE OF PUBLIC LANDS FOR RECREATION

1. FEDERAL LANDS

Lands Administered By National Park Service

Functions.—The primary function of the National Park Service is to provide an administration for national parks, monuments, and reservations with the objects of preserving their scenery, natural and historic objects and wildlife, and of providing for the public enjoyment of the same in such manner as to leave them unimpaired for the future.

The Executive order of June 10, 1933, greatly increased the work of the National Park Service by transferring to it (with certain exceptions) the parks, monuments, cemeteries, and memorials from the War Department, national monuments from the Department of Agriculture, and, further, increased its primary functions by charging it with the administration of public parks within and contiguous to the District of Columbia and (with exceptions) public buildings, both within and outside the District, and the duties and responsibilities of the former Public Buildings Commission, including control and allocation of space.

Scientific Data Available.—(a) There is careful planning in the subdivision of land uses within each park and monument, and master plans are used to control development in such manner that proper use of each class of land will be assured.

(b) Systematic surveys are made of the many new locations that are constantly being proposed for national park or monument status and for addition to existing parks. An adverse report of such investigation frequently carries a recommendation as to suitability of the area for inclusion in a State park system.

(c) Responsibility for the supervision of Emergency Conservation Work on State, county, and metropolitan parks and recreation areas is vested in the National Park Service. This has resulted in close association with all parks planning activities throughout the country.

(d) The National Park Service is further invested with authority to select the submarginal lands and prescribe the development thereon within the scope of the Submarginal Lands Acquisition Program where these are to be used for recreation purposes.

Relations to Other Federal Agencies.—There are formal cooperative agreements with the Bureau of Public Roads, Bureau of Fisheries, Bureau of Entomology, Bureau of Plant Industry, and the Public Health Service whereby specialized advisory services are rendered to the National Park Service. The Bureau of Public Roads actually carries on road construction, and the Bureau of Fisheries maintains and operates fish production plants in the parks.

Advisory assistance from other Federal bureaus is sought informally as the occasion demands. In addition there are local cooperative agreements such as those between certain parks and adjacent national forests for fire protection.1

1 National Resources Board, National Land Planning Activities, July 1934 (mimeographed), 34 pp. (see pp. 13 and 14.)

FIGURE 22.

History.—The first national park, Yellowstone, was set aside by Congress in 1872 for the dual purposes of protection and use. Other areas were later withdrawn for similar purposes, and it became an unwritten policy that public-domain areas of outstanding scenic value should be retained in public ownership as national parks.

The national parks, from the first, have been administered by the Department of the Interior. The National Park Service was established by act of Congress in 1916 as a bureau of the Department of the Interior for the administration of these areas. The organization of the bureau was effected the following year. At that time there were 16 national parks, 1 of which has since been abolished, and 1 has been reclassified as a national monument.

The early national parks comprised public domain which had been withdrawn from entry. All of the early national parks were located in Western States for the reason that the public domain existed only in those States.

Later the policy was expanded to permit the establishment of national parks on areas of outstanding scenic value which might be returned from private to public ownership. In general, Congress has adopted the policy that such lands should not be purchased with Federal funds, but that suitable areas may be established as national parks, provided they are deeded, without cost, to the Federal Government.

In 1906, Congress passed "an act for the preservation of American antiquities", authorizing the President to set aside, as national monuments, areas of special interest or value for scientific, prehistoric, or historic purposes.

The following is an extract from the act (Public, No. 209):

That the President of the United States is hereby authorized, in his discretion, to declare by public proclamation historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest that are situated upon the lands owned or controlled by the Government of the United States to be national monuments, and may reserve as a part thereof parcels of land, the limits of which in all cases shall be confined to the smallest area compatible with the proper care and management of the objects to be protected: Provided, That when such objects are situated upon a tract covered by a bona fide unperfected claim or held in private ownership, the tract, or so much thereof as may be necessary for the proper care and management of the object, may be relinquished to the Government, and the Secretary of the Interior is hereby authorized to accept the relinquishment of such tracts in behalf of the Government of the United States.

For 18 years, Yellowstone was the only national park in the world, and its origin and early history are therefore the origin and early history of the national park movement.

In 1932, Hon. Louis C. Cramton made a study of the early history of Yellowstone National Park, including its exploration, its establishment in 1872, and its hater history. The following extract from Mr. Cramton's work summarizes the first 25 years of Yellowstone's history with particular reference to the development of existing policies:

During that period of time, there was fought out in the Congress of the United States and gradually crystallized in the Nation that fairly definite code of policies which now obtains in the administration of the national parks and monuments under your charge. The history of the first quarter century of Yellowstone National Park is in fact the history of the development of our present national park policies.

Some of these policies are so universally concurred in that it does not occur to us now that they ever could have been questioned. Others, not so universally accepted, have become thoroughly established as our national policy in connection with the areas under your administration through the trials of Yellowstone. Among these policies may be noted the following:

1. That the Federal Government may, under proper circumstances, itself undertake the administration of a reservation of land "dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people."

It is true that in 1872 this region was a part of the public domain of the United States within certain of its Territories and, therefore, the question of turning it over to a State for administration was not at that time directly an issue. That course had been followed a few years previously in the case of Yosemite, and the brief debate in the Senate, January 30, 1872, in connection with the passage of the Yellowstone bill shows that the experiment of turning great scenic regions over to the State for administration was not deemed successful. The merits of Yellowstone as a park project and its outstanding importance did much to establish a general policy of Federal control in such cases. After the Territories concerned became States, demand for transfer of control to the States could, as to Yellowstone, make no headway.

2. The twin purposes of such a reservation are the enjoyment and use by the present, with preservation unspoiled for the future. The act of March 1, 1872, set the area apart as a "pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people", and at the same time required "the preservation, from injury or spoliation of all timber, mineral deposits, natural curiosities or wonders within said park and their retention in their natural condition." There has never been any serious controversy in Congress concerning the wisdom of each of these.

3. The parks are to be administered primarily for the enjoyment of the people. The early and long-continued contest concerning leases and concessions in the park has always revolved around the determination of Congress that the welfare of the visitor shall be the first consideration in park administration.

4. Enjoyment of these areas shall be free to the people. The preface to Dunraven's "Great Divide" voices protest against the fee system universal in Europe which was securing widespread foothold in the United States and popular appreciation of a nonfee system in the national parks.

The park came into being within a few years after the close of the Civil War when the national debt was large, taxation was onerous, and economy in Federal expenditures was necessary. Very soon came panic and years of depression. But at no time was there any proposal for adoption of a fee system in Yellowstone. All the debate stressed the idea that this wondrous land be free to the public. At first there was the theory that revenues from leases of needed utilities would be sufficient for the development and maintenance of the park. But as it became clear that this would not be the case and the needs became understood, the policy of appropriations from the Federal Treasury began, 1878, and has never been seriously challenged.

5. Administrative responsibility shall be civil rather than military. The act of March 1 provides, "Said public park shall be under the exclusive control of the Secretary of the Interior."

With negligible appropriations and resulting lack of administration, attended by alarming reports of game destruction and park spoilations, Congress in 1883 directed the Secretary of War, upon the request of the Secretary of the Interior, to make necessary details of troops for park protection. It was also provided that the construction of roads should be under the supervision and direction of an engineer officer detailed by the Secretary of War. In 1886 the appropriation for the park carried the provision that thereafter a company of cavalry should be stationed there for the protection of the park and eliminated any appropriation for civilian administration. Complete transfer of the administration to the War Department was proposed in bills introduced and in congressional debates. Because of the presence of troops on the frontier and the need for economy in Federal expenditures this same military administration continued for some years, but at no time did the complete transfer of the administration to the War Department make any headway in Congress. Eventually Congress eliminated the military protection and became definitely committed to civilian administration and civilian protection.

6. The welfare of the public and the best interests of the park visitors are conserved by protective permits for needed utilities. In the early days there was much fear, probably well-founded, that some monopoly would secure leases of land at strategic points which would enable them to hold up the public. No feature of park administration has had the amount of debate in Congress that there has been about Yellowstone leases. Through the insistence of Congress that the welfare of the visitor be the first consideration and through gradual growth of understanding of the necessities of the situation, the policy of protective permits with Government control of rates, service, and the extent and character of improvements has been developed.

7. The park area is to constitute a game preserve and not a hunting reservation. When the bill was under consideration in the Senate, it being observed that the destruction of game and fish for gain or profit was forbidden, Senator Anthony urged that "Sportsmen going over there with their guns" were not wanted, that the park ought not be used as a preserve for sporting. Senator Tipton urged a prohibition against their destruction for any purpose. They were satisfied with assurance that hunting would not be permitted, and that the policy has remained unquestioned.

8. No commercial enterprise in a park is to be permitted except so far as is essential to the care and comfort of park visitors.

9. The national interest shall be supreme in the park area, and encroachments for local benefit shall not be permitted. The fight to maintain and establish this policy in Yellowstone was spectacular with well-financed and influential private interests supported by some official sanction determined to secure a right-of-way in the park area for a railroad connection, ostensibly for mining development, but actually in considerable degree at least, for speculative purposes. Failing to secure such a right-of-way, the effort was made to eliminate from the park the area involved, in return adding to the park much larger areas desired elsewhere. For years the House was amenable to the desires of these private interests, and the Senate was the stronghold of opposition under the leadership of Senator Vest. It is interesting to note how in this critical period so many men of the greatest caliber in the Senate rallied to defense of the public interests. And when the Senate lost hope and was prepared to accept the inevitable the House reversed its attitude. Finally the time came that any railroad right-of-way proposal or park segregation scheme brought definite adverse report from congressional committees. The disintegration of national park areas to meet local demands has been made impossible through the struggles that revolved around the Yellowstone.

10. Recreation is an essential purpose of park use even though secondary or incidental.2 The Yellowstone Act sets the area aside as "a pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people." Senator Pomeroy in urging the bill in the Senate said, January 23, 1872, that it was proposed to "consecrate and set apart this great place of national resort, as it may be in the future, for the purposes of public enjoyment." The park then 500 miles from any railroad and its nearest railroad point so remote from centers of population under existing modes of travel, it is surprising that any large park travel could have at that time anticipated.

2 Cramton uses the term "recreation" in its more restricted sense. Recreation, as throughout this report, connotes all that is re-creative, including spiritual and stimulation as well. In this broader sense, recreation is the primary purpose.The Montana Legislature, in its memorial in 1872, asked that this area "be dedicated to public use, resort, and recreation." The Hallett Phillips report, which had much influence with Congress in 1886, said the first object accomplished by Congress in the establishment of the park was "a pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people." Preservation of these areas for scientific study, or for the enjoyment of the aesthetic taste in looking upon the beauties of nature, or the preservation of the great species of game from extermination, or the protection of an important watershed, are all purposes that have had congressional support. But the simple idea of the common people going to these regions and enjoying themselves—recreation—has always had strong appeal to Congress.

11. "In a national park the national laws and regulations should be enforced by a national tribunal." These are the words of Joseph Medill, the great publisher, and was his verdict after he had observed at first hand the workings of the attempt to enforce laws of the State of Wyoming through local officials in the Yellowstone. When the park was s created, its nearest boundary was 140 miles from the nearest civil authority. The country loudly demanded park protection, but Congress was loath to give substantial appropriations. Finally, the State of Wyoming passed a law specifying offenses and punishments, and its enforcement was attempted. The best legal authorities questioned any such authority in the State, and the effort was abandoned.

Vest fought for years to secure an enactment of needed legislation prescribing offenses with penalties therefor and sought a Federal organization to administer the park. Because of the deadlock which ensued as to railroad and boundary legislation, the needed park legislation was not secured until 1894, when the Lacey Act became effective, May 7, 1894. This act followed debate and controversy of a score of years. It declares that the Yellowstone National Park shall be under the sole and exclusive jurisdiction of the United States; that the park, although portions of it are in Montana amid Idaho, shall constitute a part of the United States judicial district of Wyoming and the district and circuit courts of the United States shall have jurisdiction of all offenses committed within the park; that any offense committed which is not punishable by Federal law shall be subject to the punishment provided by the law of Wyoming; that the United States circuit court shall appoint a commissioner who shall reside in the park and try persons charged with offenses in the park, an appeal being possible from his decision to the Federal court; that one or more deputy marshals may be appointed to reside in the park, but that arrests may be made by any officer or employee in the park of any person taken in the act. This whole structure of Federal control through existing Federal courts supplemented by a resident commissioner was worked out after 20 years of debate. Once enacted, its wisdom is generally accepted.

12. In the national parks nature is to be preserved and protected and not improved. The act of March 1 requires "retention in their natural condition." The report of the subcommittee of the committee on appropriations by Representative Holman in 1886 reads: "The park should so far as possible be spared the vandalism of improvement. Its great and only charms are in the display of wonderful sources of nature, the ever-varying beauty of the rugged landscape, and the sublimity of the scenery. Art cannot embellish these."

The above are the principal policies of a legislative character, or affected by legislative influences, which now governs in our park system. I have no doubt that many of our present policies and practices of a more purely administrative character in vogue today in various parks were likewise evolved through experience in Yellowstone.3

3 Louis C. Cramton, U. S. Department of the Interior, Early History of Yellowstone National Park and Its Relation to National Park Policies, U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington, 1932, pp. 1—4.

Policy.—The establishment of national parks was, for a long period of time, governed by an unwritten policy, indicated by the action of Congress. Some areas were established as national parks and other areas were rejected, without any written specification as to what qualifications were requisite. It came to be understood that superlative areas, of national value, are eligible to be established as national parks.

In 1918, when the National Park Service had been in operation for 1 year, Secretary Lane prepared a statement of policy for the guidance of the service, from which the following extracts are taken:

This policy is based on three broad principles:

First, that the national parks must be maintained in absolutely unimpaired form for the use of future generations as well as those of our own time.

Second, that they are set apart for the use, observation, health, and pleasure of the people.

Third, that the national interest must dictate all decisions affecting public or private enterprise in the parks.

In studying new park projects, you should seek to find scenery of supreme and distinctive quality or some natural feature so extraordinary or unique as to be of national interest and importance. You should seek distinguished examples of typical forms of world architecture.4

4Letter from Franklin K. Lane, Secretary of the Interior, to Mr. Stephen T. Mather, Director, National Park Service, May 13, 1918.

Other statements of policy have been made since that time, one of the most complete being the following, which was approved by the Director of the National Park Service in 1932:

1. A national park is an area maintained by the Federal Government and "dedicated and set apart for the benefit and enjoyment of the people." Such Federal maintenance should occur only where the preservation of the area in question is of national interest because of its outstanding value from a scenic, scientific, or historical point of view. Whether a certain area is to be so maintained by the Federal Government as a national park should not depend upon the financial capacity of the State within which it is located, or upon its nearness to centers of population which would insure a large attendance therefrom, or upon its remoteness from such centers which would insure its majority attendance from without its State. It should depend upon its own outstanding scenic, scientific, or historical quality and the resultant national interest in its preservation.

2. The national park system should possess variety, accepting the supreme in each of the various types and subjects of scenic, scientific, and historical importance. The requisite national interest does not necessarily involve a universal interest, but should imply a widespread interest, appealing to many individuals, regardless of residence, because of its outstanding merit in its class.

3. The twin purposes of the establishment of such an area as a national park are its enjoyment and use by the present generation, with its preservation unspoiled for the future; to conserve the scenery, the natural and historic objects and the wildlife therein, by such means as will insure that their present use leaves them unimpaired. Proper administration will retain these areas in their natural condition, sparing them the vandalism of improvement. Exotic animal or plant life should not be introduced. There should be no capture of fish or game for purposes of merchandise or profit and no destruction of animals except such as are detrimental to use of the parks now and hereafter. Timber should never be considered from a commercial standpoint but may be cut when necessary in order to control the attacks of insects or diseases or otherwise conserve the scenery or the natural or historic objects, and dead or down timber may be removed for protection or improvement. Removal of antiquities or scientific specimens should be permitted only for reputable public museums or for universities, colleges, or other recognized scientific or educational institutions, and always under department supervision and careful restriction and never to an extent detrimental to the interest of the area or of the local museum.

4. Education is a major phase of the enjoyment and benefit to be derived by the people from these parks and an important service to individual development is that of inspiration. Containing the supreme in objects of scenic, historical, or scientific interest, the educational opportunities are preeminent, supplementing rather than duplicating those of schools and colleges, and are available to all. There should be no governmental attempt to dominate or to limit such education within definite lines. The effort should be to make available to each park visitor as fully and effectively as possible these opportunities, aiding each to truer interpretation and appreciation and to the working out of its own aspirations and desires, whether they be elementary or technical, casual or constant.

5. Recreation, in its broadest sense, includes much of education and inspiration. Even in its narrower sense, having a good time, it is a proper incidental use. In planning for recreational use of the parks, in this more restricted meaning, the development should be related to their inherent values and calculated to promote the beneficial use thereof by the people. It should not encourage exotic forms of amusement and should never permit that which conflicts with or weakens the enjoyment of these inherent values.

6. These areas are best administered by park-trained civilian authority.

7. Such administration must deal with important problems in forestry, road building and wildlife conservation, which it must approach from the angles peculiar to its own responsibilities. It should define its objectives in harmony with the fundamental purposes of the parks. It should carry them into effect through its own personnel except when economy and efficiency can there by best be served without sacrifice of such objectives, through cooperation with other bureaus of the Federal Government having to do with similar subjects. In forestry, it should consider scenic rather than commercial values and preservation rather than marketable products; in road building, the route, the type of construction, and the treatment of related objects should all contribute to the fullest accomplishment of the intended use of the area; and, in wildlife conservation, the preservation of the primitive rather than the development of any artificial ideal should be sought.

8. National park administration should seek primarily the benefit and enjoyment of the people rather than financial gain, and such enjoyment should be free to the people without vexatious admission charges and other fees.

9. Every effort is to be made to provide accommodations for all visitors, suitable to their respective tastes and pocketbooks.

Safe travel is to be provided for over suitable roads and trails. Through proper sanitation the health of the individual and of the changing community is always to be protected.

10. Roads, buildings, and other structures necessary for park administration and for public use and comfort should intrude upon the landscape or conflict with it only to the absolute minimum.

11. The national parks are essentially noncommercial in character and no utilitarian activity should exist therein except as essential to the care and comfort of park visitors.

12. The welfare of the public and the best interests of park visitors will be conserved by protective permits for utilities created to serve them in transportation, lodging, food, and incidentals.

13. The national interest should be held supreme in the national park areas, and encroachments conflicting therewith for local or individual benefit should not be permitted.

14. Private ownership or lease of land within a national park constitutes an undesirable encroachment, setting up exclusive benefits for the individual as against the common enjoyment by all, and is contrary to the fundamental purposes of such parks.

15. National parks, established for the permanent preservation of areas and objects of national interest, are intended to exist forever. When, under the general circumstances such action is feasible, even though special conditions require the continuance of limited commercial activities or of limited encroachments for local or individual benefit, an area of national park caliber should be accorded that status now, rather than to abandon it permanently to full commercial exploitations and probable destruction of its sources of national interest. Permanent objectives highly important may thus be accomplished and the compromises, undesired in principle but not greatly destructive in effect, may later be eliminated as occasion for their continuance passes.

16. In a national park the national laws and regulations should be enforced by a national tribunal. Therefore, exclusive jurisdiction of the Federal Government is important.

17. National monuments, under jurisdiction of the Department of the Interior, established to preserve historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of scientific or historical interest, do not relate primarily to scenery and differ in extent of interest and importance from national parks, but the principles herein set forth should, so far as applicable, govern them.5

5 National Park Service, Annual report of the Director to the Secretary of the Interior for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1932, Washington, D. C., Government Printing Office, pp. 7—9.

Various organizations that are interested in recreation and conservation have taken a keen interest in the policies governing the establishment and administration of the national parks. For example, the Camp Fire Club of America issued a small pamphlet entitled "National Park Standards", which has been adopted or endorsed by 37 other organizations.

Inventory of National Park System.—Prior to 1933 the areas administered by the National Park Service were classified under only two designations, national parks and national monuments. The Forest Service administered a number of areas classified as national monuments. The War Department administered a number of areas, two of which were classified as national parks, several as national monuments, and others as military parks, battlefield sites, cemeteries, and miscellaneous memorials. An area at Morristown was established in 1933 as a national historical park and placed under the administration of the National Park Service. Since the Executive order of June 10, 1933, became effective on August 10, 1933, the areas administered by the National Park Service have included the following classifications:6

6 Editor's note: See Book Four, section on National Park Service, for National Capital Parks System.

| National parks | 24 |

| National historical park | 1 |

| National military parks | 11 |

| National monuments | 67 |

| Battlefield sites | 10 |

| National cemeteries | 11 |

| Miscellaneous national memorials | 4 |

| Total number of areas | 128 |

The total area of the principal groups is as follows:

| Acres | |

| National parks | 8,541,027 |

| National monuments | 6,687,954 |

| Other designations | 18,407 |

| Total, 23,824 square miles, or | 15,247,388 |

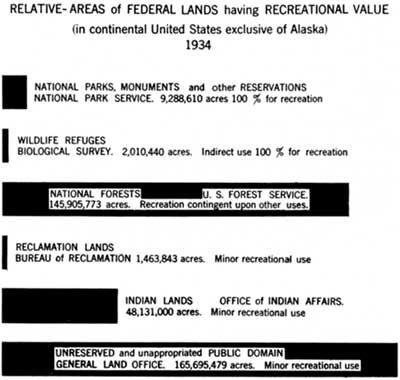

The total area administered by the National Park Service, exclusive of Alaska and Hawaii, comprises 9,288,610 acres, or approximately 14,513 square miles.

The national parks have been set aside primarily because of superlative features which are of great national value. Some of the chief features that are represented, and examples of parks containing these features, are as follows:

Topography:

Mountains: Mount McKinley, Glacier, Yosemite, Sequoia, Rocky Mountain, Grand Teton, and Mount Rainier National Parks.

Canyons: Grand Canyon, Yosemite, Zion, and Yellowstone National Parks.

Lakes: Crater Lake, Yellowstone, and Glacier National Parks.

Geology:

Volcanic: Hawaii, and Lassen Volcanic National Parks.

Caves: Carlsbad Caverns National Park.

Biology:

Animals: Yellowstone, Mount McKinley, Yosemite, and Glacier National Parks.

Forests: Sequoia, General Grant, Yosemite, Glacier, and Mount Rainier National Parks.

The national monuments and areas of other designations may be classified as historic, prehistoric, and scientific. Various subclassifications, and examples of areas containing these features, are as follows:

Historic:

Exploration and discovery: Verendrye, Cabrillo, El Morro.

Settlement: Scotts Bluff, Tumacacori, Gran Quivira.

Military: Colonial, Morristown, Gettysburg, Chickamauga and Chattanooga, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania, Appomattox.

Famous persons: George Washington's birthplace, Abraham Lincoln's birthplace.

Invention and industry: Kill Devil Hill.

Prehistoric:

Ruins: Casa Grande, Navajo, Montezuma Castle, Bandelier.

Mounds: Mound City Group.

Scientific:

Geologic:

Volcanic and igneous: Katmai, Sunset Crater, Devils Tower, Craters of the Moon.

Erosional: Cedar Breaks, Rainbow Bridge.

Caves: Oregon Caves, Lehman Caves.

Mountains: Holy Cross, Mount Olympus.

Paleontologic: Dinosaur, Petrified Forest.

Biologic: Muir Woods, Saguaro.

Ethnologic: Old Kasaan, Sitka.

All of the national parks and monuments are sanctuaries for wildlife, and several of them are noted for the species that may be seen. Yellowstone National Park is widely known as a wildlife sanctuary because of its buffalo, elk, black bear, grizzly bear, mountain sheep, antelope, and other species. Mountain goats are found in Glacier and Mount Rainier National Parks. Elk are numerous in Rocky Mountain and Yellowstone Parks. Moose are found in Glacier, Grand Teton, and Yellowstone Parks. Mount McKinley is celebrated for its Dall sheep and caribou.

The forested areas of the national parks are not lumbered, but are kept in their primitive condition. There are notable forests in several of the national parks. Big trees (Sequoia gigantea) are found in Sequoia, General Grant, and Yosemite National Parks. Yosemite and Sequoia also have outstanding forests of sugar pine, ponderosa pine, and numerous other species. Mount Rainier has splendid forests of fir and cedar.

Mount McKinley National Park contains the highest peak in North America. Mount Whitney, the highest peak in continental United States, is on the boundary of Sequoia National Park. Death Valley National Monument includes spectacular desert scenery, with interesting exhibits of plant and animal life, together with the lowest land elevation on the continent. Carlsbad Cavern is unduplicated in the United States. Hawaii has the most active volcanic area within the Nation's possession. Grand Canyon is a stupendous example of the power of erosion.

National parks offer a wide variety of recreational opportunities, including opportunity for many outdoor activities as well as features that are inspirational and educational in character.

In the appendix, pages 250 to 251, will be found two statistical tables containing a list of national parks, national monuments, and areas with other designations, administered by the National Park Service. These tabulations show for each reservation the State in which it is located, area, the special characteristics of the reservation, detailed information regarding its establishment, extent of development, and other data.

Administration and Development.—At the time of the organization of the National Park Service the volume of travel to the national parks was small, totaling less than one-half million people. As the use of automobiles increased and as the national parks became more widely known, they became more and more the destinations for vacation trips. In the 3 years from 1918 to 1921 the number of visitors to national parks increased from one-half million to a million people. In the next 5 years the number of visitors increased to nearly 2 million. The 5 years following brought the park travel to more than 3 million persons by 1931. During 1932 and 1933 the depression caused a decrease in travel, but in 1934 the total had again risen and reached a new record of 3-1/2 million visitors. The travel to national parks showed a steady increase every year from 1918 to 1931, and the present indications are that future years will show further annual increases.

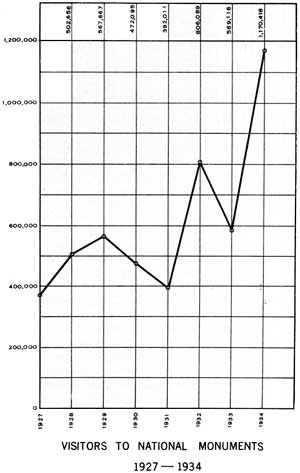

Figures are not available for the travel to all of the national monuments, but the annual travel to certain national monuments from 1927 to 1934 is shown graphically on the accompanying chart (fig. 23). This travel has increased from less than 400,000 persons to more than 800,000. These figures do not include travel to the national monuments formerly administered by the Forest Service or the areas formerly administered by the War Department.

FIGURE 23.

The development of facilities for visitors to national parks has increased with the increase in travel, but in many cases it has lagged behind the actual needs. The extent of the development in the various national parks varies with the volume of travel to the park, and with the character of the area.

The Government builds and maintains the roads and trails, ranger stations, museums, quarters for employees, free public campgrounds, and facilities available to the public without charge.

In general, the hotel and restaurant accommodations, transportation, and other services for which a charge is made, are provided by privately owned companies operating under a franchise or contract with the Department of the Interior. Such franchises provide for the operation of hotels, lodges, motor camps, automobile transportation lines, stores, and similar facilities necessary or convenient to the public.

The operating companies make annual reports to the Department; their books are audited by the National Park Service; and the rates charged are subject to regulation by the Department.

At one time it was the practice for each park to collect an automobile license fee from automobiles and other vehicles entering the park. This revenue was at first available for expenditures in the park, including maintenance of roads. Legislation now provides that these fees, and all other park revenues, be turned into the Treasury as miscellaneous receipts. The automobile license fee has been continued in most of the older national parks, though the scale of charges has been reduced. In a number of the newer parks no such fee is collected. This fee varies in different parks, ranging from 50 cents to $3 per car, and is approximately proportionate to the number of miles of road in the park.

The fee applies to the vehicle and not to the passengers. The permit issued is an annual one, and no further charge is made for additional trips during the year.

In Carlsbad Caverns National Park a fee is collected from each visitor for guide service through the cave.

In general it is the intention of Congress that the national parks should be available for public use, and it has not been expected that they should be self-supporting. Exceptionally, however, as in the case of Carlsbad Caverns National Park, the revenues collected exceed the expenditures.

Public utilities, such as water supply, sewer systems, power plants, and telephone, are furnished by the Government in some instances, and by the operators in other instances.

The policy of development in national parks is that the areas shall remain as nearly as possible in their original condition, and that buildings and other construction shall be limited to those facilities necessary or desirable for the needs of the public. No building may be constructed, either by the National Park Service or by operators, except upon plans approved in advance by the Director. Utility buildings are kept out of sight of public travel or in locations as inconspicuous as possible. The type of architecture of public buildings is not standardized, but is chosen to blend harmoniously with the surroundings. Special attention is paid to road construction, in order to avoid unnecessary scars.

The Government constructs roads and trails in the national parks and monuments in order to serve the visitors and to make the principal features of the areas accessible. In the national parks and monuments the road systems comprise a total of 2,049 miles of road, of which 1,764 miles are in national parks and 330 miles are in national monuments and other areas. The trail systems comprise a total of 5,145 miles of trail, of which 4,999 miles are in national parks and 146 miles are in national monuments and other areas. The telephone systems owned by the Government in these areas comprise 2,313 miles of line, of which 2,260 miles are in national parks, and 53 miles are in national monuments and other areas.

Nineteen museum buildings have been constructed. In seven of the parks, museum exhibits are housed in headquarters buildings. Museum displays have been developed in at least six of the national monuments, and a number of new projects are proposed. Most of the museum buildings have been constructed with donated funds.

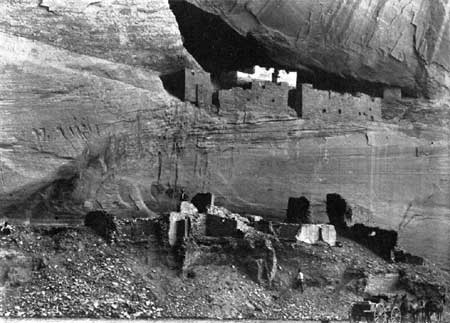

Development work in national parks and monuments has included, in areas of historic and archeological importance, the restoration of portions of existing structures in order to prevent extensive deterioration and loss. Some of the cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde have been strengthened, and partially reconstructed in order to save portions of the structures. Similar work has been done at Montezuma Castle and several of the national monuments whose chief feature is archeological remains.

The work of preserving and restoring historical structures has been accomplished in a number of the historical national monuments. At Wakefield, the birthplace of George Washington, a building has been constructed, illustrating, with as much accuracy as possible, the type of home in which George Washington was born. At Yorktown, the Moore house has been remodeled to put it in approximately the same condition as it was at the close of the Revolutionary War.

The administration of each national park is in charge of a superintendent, who reports to the Director of the National Park Service. In each park the personnel is organized into a number of departments. The ranger department is responsible for the protection of the park and its visitors. It consists of a chief ranger, assisted by the permanent rangers and by temporary rangers, who are usually employed for the summer season. The naturalist department is responsible for the informational and educational services; it consists of a park naturalist and temporary ranger naturalists. A park organization usually includes a clerical department, engineering department, sanitary department, electrical department, mechanical department, and other functions. The organization of the different parks varies with the number of personnel and with special activities which may be carried on, appropriate to the character of the area.

The administrative organization of national monuments is similar to that of national parks, though often on a smaller scale. The custodian is the executive officer. The organization is adapted to fit the objectives for which the area has been reserved.

PHOTO 5.—Another example of the destruction of archeological material. |

PHOTO 6.—Mound B—One of 34 mounds at Moundville State Park, Ala., is 58-1/2 feet high and covers about 1-3/4 acres of ground. |

Field of the National Park Service in Historic Sites.—The growth of the field of the National Park Service in the preservation and development of historical and archeological sites, clearly evident in the 60-odd areas now represented in the park program of that Bureau, has come about as a result of the gradual adaptation of an organization to function over a period of years.

In their inception, and for a considerable period thereafter, the methods developed and the agencies used by the Federal Government in handling the problems of national, historical, and archeological sites took diverse and unrelated courses. Beginning in 1890, and extending over a period of 40 years, the activities of organizations of war veterans and private historical societies brought about the development of national military parks, including such areas as Guilford Courthouse, Chickamauga, Gettysburg, Shiloh, and Vicksburg. At the time it did not seem unnatural that these areas should all be placed under the administration of the War Department. But the partial character of this movement and its shortcomings as a national program were revealed in a natural reluctance to take account of sites other than military. Some of the best of our national sites have been passed by or left entirely to unaided private initiative because there seemed to be no Federal agency willing to take the responsibility for sponsoring their preservation and control.

At the same time activities were under way in the field of archeological discoveries. Near the end of the nineteenth century, the Smithsonian Institution undertook some of its earliest and most famous investigations in archeological materials found in the cliff dwellings and pueblos of the Southwest and the mound sites of the Ohio Valley. This work was carried further by such agencies as the National Geographic Society and the Carnegie Institution, and more recently by universities and museums.

Unfortunately, awakening public interest led to the exploitation of many invaluable sites. The necessity for legislation to preserve these, and other irreplaceable areas of historic and archeological interest, became apparent. Thus occurred the first general Federal law in 1906, sometimes called the Antiquities Act, which provided for the creation of national monuments to preserve historic and other scientific areas. Although this act was an important step forward, in the light of experience it proved inadequate to meet the public responsibility involved. The sites which have been preserved under the act came to be administered by different agencies of the Government; in the Agriculture, Interior, and War Departments.

| Permanent | National Park Service, seasonal | Regular temporary | Total | E. C. W. | P. W. A. | Total | |

| Washington office: | |||||||

| Director's office and branches | 70 | ----- | 2 | 72 | 135 | 21 | 228 |

| Branch of buildings | 3,014 | ---- | 412 | 3,426 | ---- | 41 | 3,467 |

| Total, Washington office | 3,084 | ---- | 414 | 3,498 | 135 | 62 | 3,695 |

| Field force: | |||||||

| National parks | 477 | 321 | 1,028 | 1,826 | 864 | 96 | 2,786 |

| National monuments | 188 | 25 | 172 | 385 | 337 | 15 | 737 |

| Field branches, western | 55 | 1 | ---- | 56 | 68 | 62 | 186 |

| Field branches, eastern | 33 | ---- | ---- | 33 | 61 | 152 | 246 |

| National capital parks | 614 | 16 | 150 | 780 | 30 | 115 | 925 |

| State parks | ---- | ---- | ----- | ---- | 3,236 | ---- | 3,236 |

| Total field force | 1,367 | 363 | 1,350 | 3,080 | 4,596 | 440 | 8,116 |

| Total National Park Service | 4,451 | 363 | 1,764 | 6,578 | 4,731 | 502 | 11,811 |

Although perhaps not clearly perceived at the time, the fundamental tendencies looking toward a better governmental administration were more truly indicated when, in 1916, the National Park Service was created for the care and development of national parks, monuments, and reservations of scenic, natural, wildlife, or historic character. To this agency were transferred, at that time, certain historical and archeological sites such as Mesa Verde, then under the general control of the Department of the Interior. Afterward, additional areas were placed under this administration, notably certain archeological areas in the Southwest and such historical sites as George Washington's Birthplace in Wakefield, Va.

In order properly to evaluate and develop this growing program, and to provide machinery for its administration, an important step ahead was taken in 1931 with the appointment of a chief historian within the National Park Service. In the next two years a significant program was developed for the historical areas then under the control of the Service, with a more suitable personnel and a more comprehensive point of view. Already equipped with administrative and technical facilities for dealing with problems of physical development, the National Park Service was now prepared to deal professionally with the historical program, and to develop a more far-reaching policy for the handling of all Federal historical sites.

In 1933, two developments of outstanding importance occurred. One was the transfer to the National Park Service, during the general reorganization of Federal administration, of all historical and archeological sites formerly administered by various bureaus and boards of the Agriculture and War Departments. The second was the creation in the Service of an historical and archeological division to take care of problems relating to these areas.

With 60 national historical and archeological areas now under a single administration, for the first time an adequate and unified national program became possible, stressing preservation and development of an educational philosophy under which national historic sites come to have a definite cultural use.

It was not unnatural that, coincident with these developments, there should come the appointment of the Director of the National Park Service as the representative of the United States on the newly formed International Commission on Historic Monuments.

PHOTO 7.—White House Ruin at Canyon de Chelly National Monument,

Ariz. From cliff dwellings within this 83,846-acre monument it is

possible to trace the cultural of aboriginal occupation from savage

nomadism to a relatively advanced stage of civilization recorded in the

vast deposits of refuse and building remains.

Authorized Projects.—Congress has authorized the establishment of the following national parks and national monuments, when the lands involved have been deeded to the United States, without cost to the Federal Government:

1. Shenandoah National Park project, located in the Blue Ridge Mountains, Va. Authorized by Congress May 22, 1926. The area involved comprises 521,000 acres, of which 176,420 acres have now been acquired. It is anticipated that the remainder of the area will be acquired, and that the transfer to the United States will be completed within a year. The area was recommended for a national park by a committee appointed by the Secretary of the Interior. The committee was asked to recommend an area in the Appalachian Mountains most suitable for a national park, and instead recommended two—the Shenandoah area and the Great Smoky Mountains in Tennessee and North Carolina. Lands for a considerable portion of the latter have been transferred to the United States.

2. Mammoth Cave National Park project, Kentucky. This area was authorized by Congress May 25, 1926. The area comprises from 35,000 to 70,000 acres of which about 35,000 acres have now been acquired. Establishment of the park was authorized by Congress upon the recommendation of the Congressional delegation of Kentucky. The proposed park includes the historic Mammoth Cave and also several additional caves in the immediate vicinity.

3. Isle Royale National Park project, Michigan. Establishment of this park was authorized by Congress on March 3, 1931. The area comprises Isle Royale in Lake Superior, and a few adjacent smaller islands. This is the home of numerous moose, and primitive conditions prevail in much of the area. Area is approximately 133,200 acres. A local committee has been appointed to acquire the land when practicable, but under the economic conditions that have prevailed in recent years little progress has been made.

4. Everglades National Park project, in Florida, was authorized by Congress on May 30, 1934. The boundaries have not been definitely determined, but the area lies within a region approximately 50 miles square. It may comprise as much as 2,000 square miles, or more than a million acres. The proposed park includes Cape Sable, the most southerly point of the mainland of the United States, as well as a considerable area of the southwestern portion of the Florida Peninsula and neighboring keys. The features of the area are its remarkable bird life, many species of palms, orchids, mangrove trees, and other subtropical plants, and a great variety of fish, including both salt water and fresh water species. The interesting Seminole Indians live in this region, most of which is a primitive wilderness. It is anticipated that the land for the park will be acquired by a State committee to be appointed by the Governor. The area was recommended by a State association, with the endorsement of the members of Congress from Florida and was approved by the National Park Service, following an inspection by the Director and other officers and advisers of the Service.

5. Badlands National Monument project, South Dakota, was authorized by Congress on March 4, 1929. The area involved is approximately 246 square miles, or 157,000 acres. Most of the area is public domain. Options have been acquired on most of the land in the area that is in private ownership. The State of South Dakota has agreed to build certain approach roads, and these will be completed in 1935. The features of the area are delicately tinted, fantastically shaped formations carved by erosion out of the comparatively soft shales and clays. Fossil remains are abundant in parts of the region and are of high scientific value.

6. Grandfather Mountain project, North Carolina. A clause in the Sundry Civil Act of June 12, 1917 (Public, No. 21, 65th Cong.), reads as follows:

Hereafter the Secretary of the Interior is authorized to accept for park purposes any lands and rights-of-way, including the Grandfather Mountain, near or adjacent to the Government forest reserve in western North Carolina.

No action has been taken under this authority.

7. Palm Canyon National Monument project, California. An act of Congress, approved August 26, 1922 (Public, No. 291, 67th Cong., H. R. 7598), authorized the Secretary of the Interior to establish as a national monument certain lands in Riverside County, Calif., comprising 1,600 acres, provided that the consent and relinquishment, of the land by Agua Caliente Indians shall first be obtained, and that the lands shall be paid for at a price to be agreed upon, with funds to be donated for such purpose. None of the preliminary requirements has been fulfilled. This area is referred to elsewhere as suitable, if available.

8. Monocacy National Military Park project, Maryland. An act of Congress, approved June 21, 1934 (H. R. 7982), authorized the development of this area for park purposes and the preservation of its historical features.

9. Ocmulgee National Monument project, Georgia. Authorized by act of Congress, approved June 14, 1934 (H. R. 7653). Comprises an area of some 2,000 acres in and around Macon and contains Indian mounds of great historical importance.

10. Pioneer National Monument project, Kentucky. Authorized by act of Congress, approved June 18, 1934 (S. 3443). This project embraces four historical points, Boonesborough, Boones Station, Bryans Station, and Blue Licks Battlefield, which is the accredited site of the last battle of the Revolution on August 19, 1782.

Lands Administered for Game and Other Wildlife

Bureau of Biological Survey.—The Biological Survey is authorized to acquire areas to be administered as sanctuaries for the purpose of restoring and conserving various forms of wildlife. The objective is to preserve or develop on these areas favorable environmental conditions as to food, water, and cover; to protect the valuable species from man, and to control the natural enemies when necessary to do so. It is definitely known that any species—migratory game, upland or big game, song and insectivorous birds, fur bearers, and fishes—will increase wherever a suitable environment is available, and some of the more serious hazards are removed.

Refuge areas now administered by this Bureau and those planned for future acquisition are of two classes: In the first class are included those lands acquired by purchase or lease under the Migratory Bird Conservation Act, those set aside by Executive orders, or those tracts purchased under the authority of special acts of Congress. Lands in this class are selected primarily because of their known suitability as wildlife sanctuaries. This purpose is the determining factor in the examination, purchase, and withdrawal of this class of land.

There are 878,854 acres administered by the Biological Survey properly classified in group 1.

In the second class are those lands acquired by the Government for any other purpose, but placed under the administration of the Survey for wildlife uses. This class will include submarginal land acquisitions or areas in drought zones, etc., which can be developed for wildlife and which will be more profitable when so administered than when put to any other use.7

7 National Resources Board, Federal Agencies, Their Organization and Research Accomplishments in the Field of Land-planning, pp. 25 and 26.

There are 1,131,586 acres administered by the Biological Survey properly classified in this second group, making a total of 2,010,440 acres administered by the Biological Survey in 1934.

Field.—Whereas all the organized Federal lands give some degree of protection to wildlife and some of them such as the national parks, are true sanctuaries, those Federal hands where the primary use is that of providing refuge for wildlife are administered by the Bureau of Biological Survey.

The principal value of these refuges is recreational. Though no hunting is allowed on them, they exist to conserve wildlife in order that it may be hunted outside the reserve, or otherwise enjoyed. The refuge areas themselves are not recreation areas, but by protecting wildlife they provide recreation elsewhere.

The following statements are taken from a tabulation of land in the United States dedicated to migratory bird and upland game refuges.8

8 Land in the United States Dedicated to Migratory Bird and Upland Game Refuges, prepared by the U. S. Biological Survey and transmitted by letter from Mr. J. N. Darling, Chief, under date of Aug. 30. 1034.

| Local and State jurisdiction: | Acres |

| Migratory bird refuges | 7,342,427 |

| Upland game refuges | 34,940,372 |

| Federal jurisdiction: | |

| Migratory bird refuges (administered by the Biological Survey), 65 areas | 1,152,079 |

| Upland game refuges (administered by other Federal agencies), 24 areas | 1,638,748 |

The wildlife refuges administered by the Biological Survey number 104, of which 65 are maintained primarily for migratory waterfowl, all located in the continental United States. The total area of refuges devoted to migratory waterfowl as nesting, resting, and feeding grounds is 1,152,079 acres.

There are under Federal jurisdiction 24 areas in various States—under the control of the Forest Service, War Department, and Navy Department—totaling 1,638,748 acres devoted to the protection of upland game mammals and birds. In addition to this acreage there are many thousands of square miles of land embraced within national parks and monuments under the Department of the Interior on which the various forms of wildlife find sanctuary.

The most recent available information on land under local and State jurisdiction shows 7,342,4279 acres dedicated to migratory birds and 34,940,3729 acres affording sanctuary to upland game.

It will be noted that there are 104 federally owned wildlife refuges administered by the Biological Survey, of which 65 are migratory bird refuges. The remaining areas are principally for the protection of other species of birds and mammals and are not included in the above totals.

9 Includes some Federal lands. Extract from tabulation, Land in the United States Dedicated to Migratory Bird and Upland Game Refuges, op. cit.

In addition, the National Association of Audubon Societies administers 32 wild fowl refuges. For map see appendix, p. 250.

Bureau of Fisheries.—The primary function of the Bureau of Fisheries is the conservation of aquatic resources by means of— (1) artificial restocking; (2) biological investigations of habitat and life history of aquatic animals; (3) technological studies of marketing, preservation, and the collection of statistics; (4) regulation of the Alaska fisheries.

Of these, the first two functions have a relationship to land utilization programs. The production of fish at the hatcheries is a means of restocking public waters, particularly areas within the public domain such as national parks and national forests. These plants of food and game fish amount to several billions each year and are important from the standpoint of recreation and the maintenance of commercial fisheries. The stocking program does not ordinarily become effective except in existing waters already suitable for fish life, or in the stocking of impounded waters established through the activities of some other agency. Hence this feature has not previously been of importance in preliminary planning.10

10 National Resources Board, Federal Agencies, etc., op. cit., p. 32.

Field.—The number of Americans who enjoy fishing for sport has been increasing rapidly, and it is estimated that there are about 10 million anglers in this country today.

In order to maintain the supply of game fish in the inland waters of the United States, fish hatcheries are operated by private enterprise, by sportsmen's organizations, by most of the State game and fish departments, and also by the Federal Government through the Bureau of Fisheries.

The work of the Bureau of Fisheries includes the production and distribution of fish for two purposes—the maintenance of commercial fisheries (marine, Great Lakes, and inland waters), and the culture of noncommercial game fish of inland fresh waters.

As of June 30, 1934, the Bureau of Fisheries administered 87 fish cultural stations and substations. (For map see appendix, p. 252.) During the preceding 12 months, a total of 4-1/2 billion fish was distributed, while for the year ended June 30, 1933, the number was in excess of 7 billion.11 Forty species were propagated, and a total of 46 species was handled.12

11 Leach, Glen C., Propagation and Distribution of Food Fishes, 1933, Bureau of Fisheries, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C., 1934, p. 453.

12 Ibid., p. 452.

The Bureau of Fisheries cooperates closely with the various State hatcheries so as to coordinate the work and secure the best results from the combined activities. The Bureau also cooperates with the Forest Service, the National Park Service, the Bureau of Reclamation, Bureau of Biological Survey, and other Federal bureaus, supplying fish where they are most needed, The Bureau of Fisheries also assists sportsmen's groups by rendering advice on fish cultural problems, making inspections, and by other means.

The game fish propagated include several species of trout, grayling, pike, pickerel, crappie, bass, sunfish, perch, and others. In the fiscal year 1933 the output of the Bureau hatcheries was 115,000,000 game fish.13

13 Leach, Glen C., Propagation and Distribution of Game Fish, 1933, Bureau of Fisheries, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C., 1934, p. 471.

Of the hatchery production and distribution for the fiscal year 1933, game fishes accounted for approximately 2 percent of the total, five marine species amounted to about 87 percent of the total, commercial species of the interior waters represented over 8 percent; fish which migrate from salt to fresh water for spawning, and are largely of a commercial classification, represented about 3 percent of the total.14

14 Leach, Glen C., Propagation and Distribution of Game Fish, 1933, op. cit., p. 454.

Although the game fish produced are only about 2 percent of the total fish production of the Bureau of Fisheries, it is estimated that about 65 percent of the Bureau's funds and activities are devoted to game fish production and only about 35 percent to the production of commercial fish. Commercial fish are distributed at a comparatively small size a short time after hatching, but with game varieties the present practice is to rear them for as long a period as feasible, so that when planted they are exposed to natural enemies for only a short period before being large enough for the angler. The retention of game fish requires added facilities, expenses for food and care, and transportation costs are larger.

The United States Forest Service

Functions.—The principal function of the Forest Service is to bring about the best use of the forest land of the United States, including approximately 615 million acres now classed as forest land and an indeterminate area (upward of 50 million acres) of potential forest land no longer needed for agriculture. Three lines of action and responsibility are involved:

(a) Administration and use of the resources (timber, forage, recreation, wildlife, water) of 165 million acres of national forests, including extension of these forests through purchase, exchange, or otherwise.

(b) Promotion of the best use of the forest lands not in Federal ownership, through cooperation with and education of the owners (public and private).

(c) Research to develop the scientific bases for the best utilization of forest lands and the products thereof, regardless of ownership.15

15 National Resources Board, op. cit., p. 24.

Objectives.—The following is a statement of the objectives of the national forests:

The national forests are managed on the principle of providing "the greatest good to the greatest number in the long run." Under this policy the Forest Service recognizes that some lands are so valuable for recreation that no commercial exploitation should be permitted on them. Other lands are much more valuable for the timber, forage, and water power which they can produce, and on these lands recreation receives no consideration. On still a third sort of area some of the recreational values are safeguarded at the same time that the development of commodities is permitted.

In national forest recreational development the stress is laid not on preserving the primeval but in providing healthy outdoor recreation. Camping, the development of health resorts, and general frolicking are encouraged. As a result national forests in addition to providing some superlative areas and primeval areas, provide wilderness areas, camp grounds, residence areas, and outing areas for millions of people.16

16 U. S. Forest Service, A National Plan for American Forestry, op. cit., p. 483.

The Forest Service Manual makes the following statement:

National forests have for their objects to insure a perpetual supply of timber, to preserve the forest cover which regulates the flow of streams, and to provide for the use of all resources which the forests contain in the ways which will make them of the largest service. Largest service means greatest good to the greatest number in the long run. It means conservation through use, with full recognition of all existing individual rights and with recognition also that beneficial use must be use by individuals; but without the sacrifice of a greater total of public benefit to a less. In other words, the forests are to be regarded as public resources to be held, protected, and developed by the Government for the benefit of the people.17

17 U. S. Forest Service, Forest Service Manual, Washington, D. C., Government Printing Office, p. 3—A.

The Recreation section of the Manual reads in part as follows:

It is not the purpose of the Forest Service to duplicate within the national forests the functions, methods, or activities of national, State, or municipal park services, nor to compete with such parks for public patronage or support. Recognition must, however, be given to the occurrence within the national forests of mountains, cliffs, canyons, glaciers, streams, lakes, and other landscape features; natural formations such as caves or bridges; objects of scientific, historic, or archeological interest; timber, shrubs, and flowers; game animals and fish; and areas preeminently suited as sites for camps, resorts, sanitoria, picnic grounds, and summer homes. These utilities which singly or in combination afford the bases for outdoor recreation, contributing to the entertainment and instruction of the public or to public health, constitute recreation resources of great extent, economic value, and social importance. No plan of national forest administration would be complete which did not conserve and make them fully available for public use. Their preservation, development, and wise use for the promotion of public welfare is an important and essential feature of forest management which adequately should be coordinated with the production of timber and forage and the conservation of water resources. The areas now constituting the national forests have been used for recreational purposes since the first settlement of the country, and such use naturally will grow as the population increases and as wild land is converted to cultivation.

The circumstances prevailing upon a given area must necessarily determine whether recreation shall be dominant, equal, or subordinate in relation to other forms of use. Major timber, grazing, or water values should not be sacrificed to minor recreation values. On the other hand, major recreation values should never be sacrificed to minor timber, grazing, or water values. Where recreation and other forms of use conflict, the first step should be to determine whether careful planning will not secure maximum utilization of one resource with minimum injury to the other. In timber sales, for example, the leaving of protective strips along roads and surrounding parks and camp grounds may make it possible to utilize practically all the marketable timber without impairing the scenic or recreational values. Rigid protection of an area from grazing during the summer camping season may make possible its use for grazing purposes before camping begins or after it ends. Proper sanitary facilities and requirements may render unobjectionable the recreational use of a watershed constituting a municipal water supply. If, however, a conflict between two forms of use cannot be reconciled, then the use of greatest importance should take precedence over the others, and where recreational utilities are clearly of minor importance they may be disregarded or suppressed.

Existing national, State, and municipal parks are important primary elements in any comprehensive regional plain of recreational development. The relation of forest recreational development to other national, State, county, municipal, organizational, or private activities in the same field should be systematically analyzed and correlated so as to enhance rather than compete with such activities.18

18 U. S. Forest Service, Forest Service Manual, op. cit., p. 98—L.

The forested areas have always been the recreational field of the people living nearby, and with better roads and increasing use of automobiles, they are now extensively used by people in an ever-widening circle. Recreation in the national forests has been a process of natural evolution and sought for by the public without, at first, much stimulation by the Forest Service. The early annual expenditures for recreational use were small, about $10,000 a year up to 1924, but they are now increasing.19 In 1933 there was appropriated $28,000 for recreational surveys and plans; more than $100,000 for recreational development; $135,000 for fish and game propagation, and $16,000 for fish and game surveys and plans. Other recreational expenses, such as road and trail construction and maintenance, are paid out of other appropriations.20

19 U. S. Forest Service, Report of the Forester, 1925, Washington, D. C., Government Printing Office.

20 U. S. Forest Service, Report of the Forester, 1933, p. 22.

Several different types of recreational forest areas are recognized:

Superlative areas include national parks and areas in the national forests that meet similar standards.

Primeval areas (sometimes called natural areas) are tracts of virgin timber in which human activities have never upset the normal processes of nature. Thus they preserve the virginal growth conditions, which have existed for an inestimable period.

Wilderness areas are regions which contain no permanent inhabitants, possess no means of mechanical conveyance, and are sufficiently spacious that a person may spend at least a week or two in travel in them without crossing his own tracks.

Roadside areas refer to the timbered strips adjoining the more important roads, and also include strips of timber left along lakes, rivers, and boat routes.

Camp-site areas include areas specially designated for the use of camping.

Residence areas provide space for private homes, hotels, and resorts, group camps, stores, and services of various sorts. These sites are usually leased, with an annual rental.

Outing areas are intermediate between primeval areas acid commercially operated timber tracts.21

21 S. Doc. No. 12, op. cit.

The terms actually in use by the Forest Service differ from the above designations and include "Natural areas", "Primitive areas" (corresponding with "Wilderness areas") and "Recreational areas."

The following concise statement of recreational use of the national forests is made by the Forest Service:

The national forests are rich in scenic beauty. They have the double attractiveness of a country that is largely wilderness yet is easily accessible because of thousands of miles of good roads and trails. They are the home of game and fish; the refuge and breeding grounds of much of the wildlife that remains. Their wide distribution and extent, and their proximity to thousands of communities make them natural centers of summer recreation. Within their boundaries travelers by motor, by wagon, on horseback, or on foot, campers, hunters, and fisher men, amateur photographers, hikers, naturalists—in fact all who wish to come—have equal opportunity. Care with fire and cleanliness in camp are all that are necessary to make the visitor and the vacationist welcome.

The Forest Service looks upon the recreational possibilities of the forests as public resources, to be wisely used and carefully safeguarded, along with the timber, water, and other resources for the conservation and management of which the forests were established. Everything possible is done, within the limits imposed by available time and funds, and by the necessity of giving first attention to the primary purposes of the forests, to develop the recreational resources and to make them available for public use.

For the erection of summer homes, hotels, resorts, and other structures for recreational purposes, individuals, associations, or commercial companies may secure special-use permits. These are usually granted for an indefinite period, but where the proposed development involves a considerable investment by the permittee the permit may be granted for a term of not more than 30 years. In most cases it has been found that the indefinite period permit is entirely satisfactory to the permittee. Not more than 5 acres may be allowed to any single person or association.22

22 U. S. Forest Service, Vacation in the National Forests, Washington, D. C. Government Printing Office, 1930, p. 1.

Recreational Use of the National Forests.—The national forests have a high value for recreation. The recreational use as a rule is secondary to the primary objective of forestry.

There are more than 160 million acres of national forests in the United States. They are located in 33 States, Alaska, and Puerto Rico. While some of these national forests are in Eastern States, by far the largest areas are in Alaska and the public land States of the West, and are composed principally of areas reserved from the public domain.

Many of the national forests are in mountainous areas, many are scenic, and most of them offer a variety of recreational opportunities, such as motoring, camping, hunting, fishing, trail trips on foot and on horse back, mountain climbing, winter sports, and other outdoor activities.

It is necessary that the recreational use of the national forests be supervised in order to reduce the fire hazard created by camping, smoking, and other activities of forest users. Camp grounds must be kept sanitary in order to prevent stream pollution.

In most of the national forests, hunting and fishing are permitted under State laws. Some Federal game refuges have been established and numerous State game refuges have been created. All of the national forest area is available for the propagation of wildlife. Game is protected on about 15 percent of the national forests, and hunting is permitted, under State laws, on about 85 percent of the forest area.

Table IX shows the total area of the national forests, including lands approved for purchase, as 167,000,000 acres, on June 30, 1934; the area of the Federal game refuges as 4,000,000 acres, more than half of which is in Alaska; the total area of State game refuges as 21,000,000 acres, most of which is in the Western States.

The total area of national forests and purchased units in the 48 States is 145,905,773 acres (1934).

| National forest region | Net area of national forests and purchase units,

as of June 30, 19342 Acres |

Net area game refuges on national forests3 | |

| Federal Acres |

State Acres | ||

| 1. Northern | 22,791,449 | ----- | 2,563,700 |

| 2. Rocky Mountain | 19,383,134 | 195,158 | 4,769,517 |

| 3. Southwestern | 19,932,106 | 837,115 | 2,224,397 |

| 4. Intermountain | 29,183,676 | ----- | 5,348,396 |

| 5. California | 19,352,839 | 20,770 | 2,019,870 |

| 6. North Pacific | 23,121,116 | ----- | 3,111,440 |

| 7. Eastern | 2,554,586 | ----- | 90,278 |

| 8. Southern | 5,512,882 | 249,132 | 251,750 |

| 9. North Central | 4,073,985 | 2,671 | 864,193 |

| 10. Alaska | 21,342,300 | 2,697,225 | ----- |

| Total | 167,248,073 | 4,002,071 | 21,243,541 |

1 Figures furnished by the U. S. Forest Service.

2 Includes lands approved for purchase under the Weeks and Clarke-McNary laws.

3 Included in the net area national forest and purchase units.

About 3,000,000 acres of national forests have been closed to domestic livestock in the interest of wildlife production.

The Senate Committee on Conservation of Wildlife Resources estimated the number of hunters and fishermen in the United States, in 1929, at 13,000,000, and it is estimated that this figure constitutes an increase of approximately 400 percent over the preceding decade.23

23 Wildlife Conservation, S. Rept. 1329, 71st Cong., 3d sess.

The value of forest recreation is not susceptible of exact appraisal, but the following quotation from The People's Forests, by Robert Marshall, is of interest in this connection: