|

National Park Service

Recreational Use of Land in the United States |

|

SECTION IV. PROGRAM FOR DEVELOPMENT OF THE NATION'S RECREATIONAL RESOURCES

1. THEORY OF DIVISION OF RESPONSIBILITY FOR RECREATION

In the field of recreation:

(1) What are the responsibilities of the local governments?

(2) What are the responsibilities of the State governments?

(3) What is the responsibility of the Federal Government?

If a certain responsibility for providing recreation falls logically and necessarily on the Federal Government, how should this responsibility be divided among the various branches of the Federal Government?

Because these old questions must be faced again in the relatively new field of recreational planning, they demand reexamination.

Local, State, and Federal Responsibilities

Supplying facilities for the day-by-day recreational needs of the people is primarily a local responsibility, whether met by municipalities of sufficient population and wealth to supply all the various types of recreation required, or by county or metropolitan park boards which, dealing with the needs of a group of urban and rural communities, make it possible for each of those communities to enjoy such facilities. Use by outside residents of facilities so supplied and maintained is incidental.

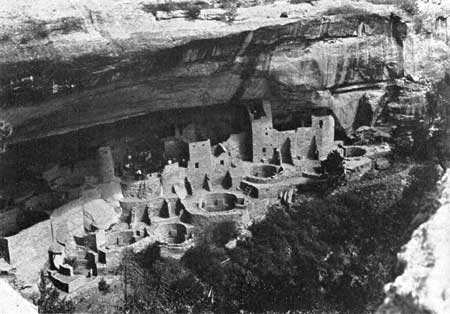

Every State has areas either of such high scenic value or of such high value for active recreation, or both, or possessing such interest from the scientific, archeological, or historical standpoint, that their use tends to be State-wide in character. Acquisition of such areas, and their development and operation, appear to be primarily a function of the State, though this should not preclude joint participation in acquisition, and possibly in development and operation, by the State and, by such community or communities as might receive a high proportion of the benefits flowing from their establishment.

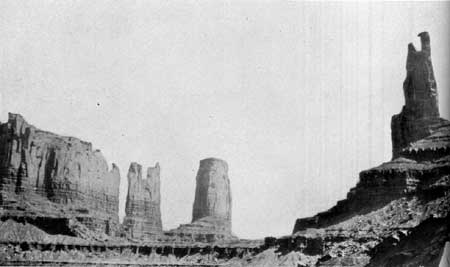

Taking the Nation as a whole, there are, again, areas of such superlative quality, because of their primeval character or scenic excellence, or historical, archeological or scientific importance, or because of some combination of these factors, that they are objects of national significance. It is the responsibility o the Federal Government to acquire and administer these.

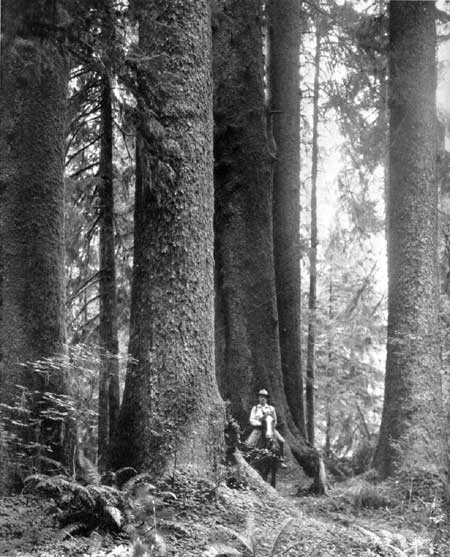

The Federal responsibility is particularly emphasized in the case of the primeval wildernesses. There are several reasons for this. Remaining areas of primeval condition are few. Those who live in the regions immediately adjacent to the wilderness are usually pioneers whose lives and thoughts are devoted to wilderness conquest. Hence the Federal eye rather than the local eye must be depended upon to recognize and protect what wildernesses remain. A wilderness reserve ordinarily must be of great size if it is to remain primeval, and the present value may seem insignificant, whereas the deferred value is very great. Take all these conditions and circumstances together, and it is apparent that the monumental task of saving the primeval must be very largely a Federal responsibility.

There is, in addition, another group of areas, the ocean and Great Lakes beaches, which as a group, are heavily freighted with national interest, and are extensively sought by persons living at a great distance from them. It is unlikely that these areas will be acquired by the States to a sufficient extent for the public, and it would appear reasonable to expect the Federal Government to acquire and administer a representative group of them.

Departments and Bureaus of the Federal Government

The division of responsibility among the several governments seems thus to be susceptible of fairly clear definition. Defining the division of responsibility as it concerns the several departments and bureaus of the Federal Government is more difficult. Several types of federally owned lands, such as national parks and monuments, national forests, Federal wildlife reservations, and Federal reclamation lands, provide recreation. Recreation is the primary objective of national parks and monuments and Federal game refuges, although in the latter areas the recreational value is usually realized elsewhere.

Recreation is a secondary objective of the other types of federally owned lands. The recommendations made at a later point in this report arise from certain principles which are stated as follows:

1. It is a Federal responsibility to develop to their highest usefulness the recreational values inherent not only in national parks and monuments, but in other Federal holdings as well, as long as they remain in Federal ownership.

2. In this development every effort should be made to avoid unnecessary duplication of "special purpose" organizations.

3. There should be constant and conscientious striving toward interbureau and interdepartmental cooperation.

4. Wildlife protection and administration must be coordinated on all holdings if the Federal Government is to be effective in its responsibility to conserve this recreational resource.

5. Commercial objectives should not be permitted to jeopardize the value of lands which are primarily of importance for recreational use.

2. LOCAL COMPONENTS

Municipalities1

It is estimated that land devoted to all municipal purposes amounts to about 10 million acres, which is about one-half of one percent of the total land area in the United States.2

1 Editor's note: The tables used in this section without individual citations were compiled from 1930 census Bureau figures, and information obtained by the National Recreation Association in a Nation-wide survey of municipal parks and recreation areas (1925—26).

2 Joint Committee on Bases of Sound Land Policy, What About the Year 2000? Harrisburg, Pa., McFarland, 1928, p. 48.

If the recreational use of land be considered from the viewpoint of concentration of population, and from the viewpoint of the necessity of frequency of use, it is evident that the focal point and the very foundation of a national plan for recreation is within the numerous municipalities of the United States and their immediate environs. Improved methods of transportation have made possible a distribution of the responsibility to other political units, such as counties, metropolitan districts, States, and the Federal Government, but the basic responsibility remains with the local municipalities.

What, therefore, is the extent of responsibility of the municipalities?

In attempting to answer this question, the 16,598 incorporated municipalities3 will be divided into two general classes, based upon the ability or lack of ability of these municipalities to provide not only the minimum types of land areas desirable for meeting the daily or very frequent recreational-use needs of its people, but also the necessary finances to support a recreation-administering agency on a year-round basis.

3 There are unincorporated communities in the United States as large in population as many that are incorporated. The number is unknown.

Municipalities under 8,000.—The experience of the National Recreation Association covering a period of over 25 years in organizing recreation systems has demonstrated quite conclusively that most municipalities under 8,000 population cannot provide the desirable necessary recreation areas and maintain a year-round recreation administrative organization. Practically all such municipalities may be expected to provide some kind of a maintenance organization.

Therefore, the first group of municipalities to be considered is comprised of all those having less than 8,000 inhabitants.

These four groups of municipalities comprise about 93 percent of all incorporated places in the United States, 22.7 percent of the total population of all incorporated places, and 14.5 percent of the population of the Nation.

TABLE XV.—Municipalities in the United States under 8,000 population showing numbers and total population1

| Municipal groups | Number in each group | Total population |

| 5,000 to 8,000 | 625 | 3,903,781 |

| 2,500 to 5,000 | 1,332 | 4,717,500 |

| 1,00010 2,500 | 3,087 | 4,820,707 |

| Under 1,000 | 10,346 | 4,362,746 |

| Total | 15,390 | 17,804,024 |

1 U. S. Bureau of the Census, Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930, Population, vol. 1; Number and Distribution of inhabitants.

The strictly rural village, town, and small city, if present trends continue, will occupy a less and less important position in American life unless the widespread distribution of cheap electric power attracts industries to them from the larger centers of population.

Very little information is available as to what these small communities have provided for themselves in recreation areas; the most complete available statistics are from a study conducted by the National Recreation Association in cooperation with the American Institute of Park Executives in 1925—26. The following table is a summary of the findings of this study.

| Municipal groups | Number places | Number reported in study | Number having no parks | Number having parks | Total acres |

| 5,000 to 10,000 | 721 | 322 | 67 | 255 | 11,366.87 |

| 2,500 to 5,000 | 1,320 | 309 | 72 | 237 | 5,186.89 |

| Under 2,500 | 12,905 | 1,320 | 751 | 569 | 5,346.64 |

| Total | 14,946 | 1,951 | 890 | 1,061 | 21,900.40 |

1 Editor's note: These figures are from a Nation-wide study of municipal park and recreation areas and systems conducted by the National Recreation Association in 1925—26 at the request of the National Conference on Outdoor Recreation.

Of the 721 communities in this group (5,000 to 10,000) in 1920, reports as to park areas were secured from 322, or 44.6 percent of the total. Sixty-seven, or 20.8 percent of the total reporting, had no parks, while 255, or 79.2 percent of total reporting, had 11,366 87 acres, an average of nearly 45 acres per community. Twenty-eight of the communities reporting parks had a total park area of 3,238.69 acres; the ratio of park acreage to the total population in these 28 cities was 1 acre to every 58 inhabitants. The average number of parks per city was about 4.4

4 Weir, L. H., editor, Parks: a Manual of Municipal and County Parks. New York, Borneo, 1928, 2 vols.; vol. 1, pp. 76—77.

In the group with from 2,500 to 5,000 inhabitants, approximately 25 percent were reported. Seventy-two, or 23 percent of those reporting, had no parks, while 237, or 77 percent of those reporting, had 5,186.89 acres of park areas, an average of over 21 acres per community. These statistics of recreation areas did not include school sites, which in many communities were large enough to provide quite amply for the outdoor active recreation needs of the children and young people. Thirty-five of the 237 communities reporting parks had 2,529.89 acres, and the average ratio of park acreage to population was 1 acre to every 45 inhabitants. The number of park properties ranged from one to seven. Thirty-three of these communities reported a total of 298.91 acres of school sites and a total of 89 sites.5

5 Weir, L. H., editor, Parks; op. cit., vol. 1, pp. 71—75.

In the group under 2,500 population, reports were received from about 10 percent. More than half of the 1,320 communities reporting had no parks, while 569, or 43 percent of those reporting, had a total of 5,346.64 acres, an average of about 9.4 acres per community. Of the 569 communities reporting parks, 80 were selected as the most representative from the viewpoint, of either the size of their park acreage, or school ground area, or both.

These villages ranged in size from 86 to 2,484 inhabitants. The total park area owned by 69 of the 80 communities was 1,762.17 acres, or an average of slightly more than 25 acres per community. The ratio of park acreage to population was 1 acre to every 33 inhabitants. Seventy-five of the 80 communities reported a total of 594.99 acres of school grounds.

A summary of the average park acreage per community of all the communities reporting parks in the several population groups is presented in the following.

| Population groups | Number communities reporting | Average park communities acreage per community |

| 5,000 to 10,000 | 255 | 44.6 |

| 2,500 to 5,000 | 237 | 21.9 |

| Under 2,500 | 569 | 9.4 |

| Population groups | Number selected communities | Average park acreage per community | Ratio of acreage to population |

| 5,000 to 10,000 | 28 | 115 | 1:58 |

| 2,500 to 5,000 | 35 | 72 | 1:45 |

| Under 2,500 | 69 | 25 | 1:33 |

These two tables give a slight clue to what municipalities in the various population groups may be expected to provide for themselves in recreation areas, based on what some of them have actually done.

It is very difficult to fix a reasonable standard for the various groups of small municipalities to follow in providing their own recreational areas. On the basis of the very limited data of the most progressive communities in the various population groups as presented in the immediately preceding table, a reasonable average ratio of acreage to population in the population group is set forth in table XIX.

| Population groups | Standard |

| 5,000 to 8,000 | 1 acre to every 75 inhabitants. |

| 2,500 to 5,000 | 1 acre to every 60 inhabitants. |

| 1,000 to 2,500 | 1 acre to every 50 inhabitants. |

| Under 1,000 | 1 acre to every 40 inhabitants. |

| Population group (1930) | Number communities | Estimated total acreage each group | Estimated average park acreage per community |

| 5,000 to 8,000 | 625 | 52,050 | 83+ |

| 2,500 to 5,000 | 1,332 | 78,626 | 59+ |

| 1,000 to 2,500 | 3,087 | 96,414 | 31+ |

| Under 1,000 | 10,346 | 109,068 | 10+ |

| Total | 15,390 | 136,158 | --- |

It will be shown later than the total estimated recreational area desirable for 17,804,824 inhabitants of the 15,390 incorporated places under 8,000 population (1930) is approximately one-half of the total estimated desirable recreation space for the 60,333,452 inhabitants in the 1,208 cities of 8,000 population and above; this appears to be entirely out of proportion, considering the relative number of people in the two general groups of incorporated places.

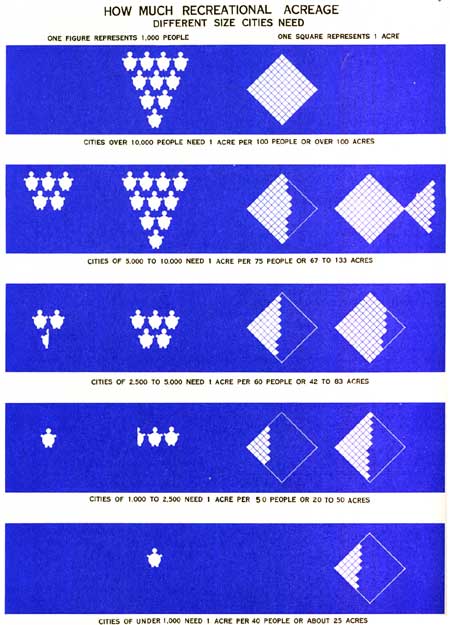

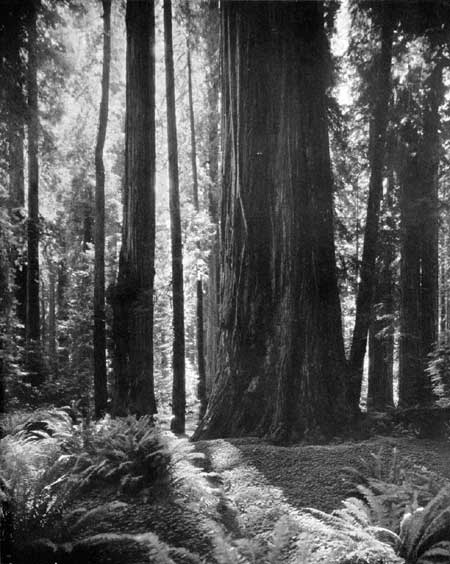

FIGURE 31.

The basic reason for this apparent lack of balance is that irrespective of the number of people to be served there is a minimum desirable number of types of recreation areas with a total gross acreage necessary in any corporate community if the outdoor recreational needs of the inhabitants are to be served. For example, a community of 1,500 people should have one combined playground and school site of not less than one block, or about 3 acres; one playfield of not less than 5 or more acres; one small park of at least a block, or about 3 acres, in the shopping center of the town; one picnic grove of 10 or more acres; one small natural swimming center if topographical conditions present the opportunity; a site for a public library and perhaps another for a community house. In short, the total desirable recreation area would be from 25 to 30 acres. This same amount of space in a large city, if divided into special types of areas, would serve satisfactorily a far larger number of people. If 25 acres, for example, were divided into tracts of 5 acres, each located in a residential district of 160 acres in a city having as low a density as 25 persons per acre, these playgrounds would serve adequately the outdoor play needs of the children of a population of approximately 20,000. At a the same time they would provide space for a school building on each with recreational opportunities for adults also. The recreation areas of villages, towns, and small cities are frequently used by the people living on the farms in the surrounding country so that they serve a far larger number of people than are actually enumerated as living in the small municipalities themselves.

For financial reasons all-year-round administrative recreational leadership cannot, as a rule, be provided by the 15,390 small municipal corporations comprising this general group of incorporated places. Reliance must be had for recreational administration, and perhaps for acquisition and development of some of the desirable types of properties, on a larger governmental unit. The county is perhaps the best existing governmental agency for handling this problem, not only for the numerous villages, towns, and small cities, but also for providing a recreation service under leadership for the population dwelling in the open country. In many instances also State-owned properties and outlying parks of the larger cities will be so located as to serve frequently the recreational needs of the people of many of the villages, towns, small cities, and strictly rural population in their vicinity.

Cities of 8,000 and up.—The second group of cities comprises all those of 8,000 population and above. The number of cities in this general group classified according to size is shown in the following table.

| Group | Number cities (1910) | Population | Percent total population of Nation |

| 1,000,000 or more | 5 | 15,064,555 | 12.3 |

| 500,000 to 1,000,000 | 6 | 5,763,987 | 4.7 |

| 250,000 to 500,000 | 24 | 7,956,228 | 6.5 |

| 100,000 to 250,000 | 56 | 7,540,966 | 6.1 |

| 50,000 to 100,000 | 98 | 6,491,448 | 5.3 |

| 25,000 to 50,000 | 185 | 6,425,693 | 5.2 |

| 10,000 to 25,000 | 606 | 9,097,200 | 7.4 |

| 8,000 to 10,000 | 226 | 1,993,175 | 1.6 |

| Total | 1208 | 60,333,452 | 49.1 |

1 Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930, Population, vol. 1; op. cit.; see p. 14.

The above cities may be expected to provide not only the necessary recreational spaces within their borders, or very near their boundaries, for daily or frequent use of their populations, but also to maintain a year-round administrative recreational service.

Each of the cities in the above groups may reasonably be expected to provide at least 1 acre of recreational area for every hundred of its inhabitants. This ratio should be higher for all or part of the group comprising cities from 10,000 to 25,000, if these cities are to provide for themselves all the different desirable types of recreational areas. However, for purposes of calculation, the generally accepted standard of 1 acre for every hundred of the population will be used for all groups.

This standard, applied to the total population of all groups, would show that there should be reserved for recreational purposes for these 60,333,452 inhabitants a total of 603,333 acres now, without making allowance for future growth of population. The study of municipal recreation spaces conducted by the National Recreation Association, 1930, covering cities of 5,000 and above, and securing reports from 1,072 cities of a total of 1,833, showed a total of 308,804.87 acres now owned by 898 cities; 174 cities reporting as having no parks.6

6 U. S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Park Recreation Areas in the United States, 1930; Bulletin no. 565, May 1932, 116 pp., tables; see p. 7, table 2.

This total recreation acreage, however, includes 89,196.3 acres lying outside the limits of the cities. Deducting this total from 308,804.87, there remains within the city limits of the 898 cities a total of 219,608.57 acres. The probabilities are that if complete records on recreational areas, including school sites owned by all the cities of 5,000 and above within their limits, had been available in 1930, they would show that about one-half of the desirable recreational areas had been acquired, although a rather surprisingly large number of the smaller cities was entirely lacking in park spaces.

Studies conducted by the Recreation Division of the National Resources Board, 1934, show 206,916.17 acres of recreational spaces in 440 cities of 5,000 population and above.

Taken as a whole, the cities of 10,000 inhabitants and above are still far from the goal of even so low a standard as 1 acre to every 100 of the population.

Balanced planning of lands for recreation within cities requires that the total acreage secured by application of the principle of 1 acre for every 100 of the population be divided into types of areas of varying sizes, each type performing a specific, primary recreational function. Among some of the most outstanding types of recreation areas are:

1. Children's Playgrounds.—Of the total recreation area secured through the application of the principle of 1 acre to every 100 inhabitants, not less than 12 percent should be allocated to children's playgrounds for children from 5 to 14 years of age, each playground ranging from 3 to 8 acres in extent with an average size of 5 acres.

From 3 to 5 percent of each 160 acres of residential area should be reserved for a children's playground.

These areas may also be sites for grade schools. In fact, the distribution of grade-school sites and community-playground sites will in general coincide, and in an ideally planned city the great majority of the children's playgrounds should be located adjacent to schools.

2. Neighborhood Playflelds or Playfleld-Parks.—From 15 to 18 percent of the gross area, under the principle of 1 recreation-acre to every 100 inhabitants, should be allocated to neighborhood playflelds or playfleld-parks. There should be one of these areas to each 640 acres of residential territory, and it should range in size from approximately 15 to 30 acres, or even more. In other words, it should contain from 2-1/2 to 5 percent of each 640 acres of residential territory. These areas may also be used as the sites for junior- and senior-high schools, or, conversely, large sites of such schools may be used as community playflelds and neighborhood parks.

3. Miscellaneous Recreational Areas.—These include athletic fields, stadia, golf courses, bathing beaches, areas devoted exclusively to tennis or some other special type of facilities. There is no special rule governing the amount of area which should be set aside for miscellaneous active-recreation areas. Requirements of the particular use determine more or less the amount of space required for each, as a minimum of 100 acres for an 18-hole golf course, 15 to 20 acres for a first-class athletic field or stadium, including the enclosed space and outside area for auxiliary fields and auto parking.

In a properly balanced system of recreational areas in a city, it is probably desirable to use for active recreation from 30 to 50 percent of the total recreational area, assuming 1 recreation-acre for every 100 inhabitants.

4. The acreage remaining after deducting areas for children's playgrounds, playflelds, or playfield-parks and miscellaneous active recreational areas may be distributed among areas characterized by landscaping and natural or designed topographical features. They are intended primarily for adornment of areas in cities wherever they are located; to preserve natural topographic features better adapted for general recreation than for any other purpose; to provide opportunities for relaxation in an environment of beauty; to make possible frequent contact of the people with the elements of nature; to promote the study of nature; and, in some instances, as in large parks or waterfront parks, to provide opportunities for forms of active recreation which the natural conditions readily permit, such as hiking, riding, picnicking, boating, swimming, nature study, presenting dramatic performances, concerts, play festivals, civic celebrations, and playing of games.

The following are among the most important types of landscaped areas:

(a) Neighborhood or in-town Parks.7—These are comparatively small areas located in residential districts, downtown sections, and even in parts of cities occupied by industry and transportation. There is no general rule as to the desirable total or individual acreage of this type of property. They should, however, be distributed over the city on the basis of about one for every square mile. They are sometimes combined with a playfield area, making a playfleld-park.

7 Editor's note: There is a class of very small properties, numerous in some cities, called ovals, triangles, circles, and parking strips, annually resulting from left-over areas in the street plan, or consciously introduced by real-estate subdividers, They are not neighborhood parks.

(b) Large Parks.—Large parks are areas ranging from a hundred or several hundred acres to several thousand acres, although in small cities areas from 40 to 100 acres perform for the inhabitants much the same functions as do the larger areas in large cities. Such areas are generally characterized by varied topographic features and an abundance of plant life arranged according to the principles and rules of landscape architecture, although very frequently they provide a variety of active recreational opportunities. There is no rule governing their numbers, size, or distribution. Natural topographic features in a city, availability and cheapness of land, and accessibility to large segments of the population are factors in their location. All small cities should have at least 1 area of this type, and in the larger cities it is desirable that they be distributed so that no citizen would be more than 1 to 3 miles from one.

(c) Educational-Recreational Areas.—These comprise areas for a zoological park or garden, botanical garden, arboretum, and special educational gardens. Among these types of areas, zoos are by far the most numerous.8 The park-recreation systems of American cities are notably deficient in special opportunities for the study of plant and animal life in their natural habitats.

8 Park Recreation Areas in the Unite States, 1930; Bulletin no, 565, op. cit. p. 21.

5. Other recreational areas not infrequently owned by cities, but which are excluded from the gross area assuming 1 acre to every hundred of the population, include organized camp sites, outlying forest parks, boulevards, and parkways. The first two are excluded because they lie outside the boundaries of the cities, and the second two, because they are parts of the general highway system of cities. Exception may be noted in the case of a parkway that has sufficient width and natural topographic conditions to render general recreation services somewhat similar to a large park.

After the requirements for children's playgrounds and playflelds and miscellaneous active recreation areas have been fulfilled in the recreational land-use plan of a city, it is often wise and good planning to forget the general rule of 1 acre for every hundred inhabitants in providing the different types of landscaped areas, including especially large parks. The preservation of natural topographic features, as water fronts, rugged terrain, and stream valleys, should be done on a generous scale even though the result may be that the total gross area of recreation space within the city may become as high as 1 acre to every 50 of its inhabitants. Not a few cities in the United States have already exceeded the ratio of 1 acre to every hundred inhabitants.

According to the standards of land planning for recreation which have been suggested for various groups of municipalities in the United States, the gross area devoted to recreational purposes in these municipalities should now be approximately 1,000,000 acres. This is only about 10 percent of the estimated total area of all lands devoted to municipal uses in the United States.

The exact amount of lands comprised in the park-recreation systems of the cities of the United States, plus the school sites and other publicly owned areas with an auxiliary recreational use, is not known. However, on the basis of statistics available for existing park acreage, partial statistics of existing school sites, and other publicly owned lands with an auxiliary recreational use, it is estimated that the gross acreage available for recreational use is somewhere between 400,000 and 500,000 acres. In other words, existing lands for recreational use within cities are approaching 50 percent of the gross area considered desirable.

Counties

The county is one of the oldest of Anglo-Saxon political units. In America, exclusive of New England, it has been and is still today one of the most important political subdivisions of States, although in recent years there has been a tendency toward the absorption of some of its ancient functions by the State. Such loss of function as the control of roads has been counterbalanced to some extent by an extension of its functions into fields not hitherto covered by counties, such as health, library service, agricultural extension service, and recreation.

It is the purpose here to examine the possibilities of the county as a governmental unit and agent in the acquisition, development, and operation of lands for recreational purposes and for the general maintenance of a recreation service.

One impressive fact about counties in America is the large number of them. As an administrative governmental unit the system of counties was laid out for the most part when transportation was slow and communication in general difficult. This condition chiefly accounts for the large number of counties in the older sections of the country and their comparatively small size. Modern methods of transportation and communication have outmoded the original layout of the county system.

Another impressive fact is the very large number of counties that decreased in population during the decade from 1920 to 1930.

There are 3,099 counties in the United States, but out of a total of 2,955 counties whose boundaries remained unchanged during the last decade (the boundaries of 144 counties were changed) 1,220, or 41.2 percent, had less population in 1930 than 1920. The combined population (22,099,508) of these de creasing counties constituted 18 percent of the total population of the country in 1930.9

9 President's Research Committee on Social Trends. Recent Social Trends in the United States. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1913. 2 vols., tables, diagrams. See vol. 1, p. 446.

The number of counties in each State grouped by geographic divisions and the number in each State which decreased in population in the decade 1920—30 are shown in the following table:

| Number of counties | Number of counties decreased in population | |

| NEW ENGLAND | ||

| Maine | 16 | 5 |

| New Hampshire | 10 | 1 |

| Vermont | 14 | 7 |

| Massachusetts | 14 | 0 |

| Rhode Island | 5 | 0 |

| Connecticut | 8 | 0 |

| Total | 67 | 13 |

| MIDDLE ATLANTIC | ||

| New York | 62 | 11 |

| New Jersey | 21 | 0 |

| Pennsylvania | 67 | 19 |

| Total | 150 | 30 |

| SOUTH ATLANTIC | ||

| Delaware | 3 | 0 |

| Maryland | 24 | 9 |

| Virginia | 100 | 37 |

| City counties | 24 | 3 |

| West Virginia | 55 | 19 |

| North Carolina | 100 | 5 |

| South Carolina | 46 | 24 |

| Georgia | 161 | 104 |

| Florida | 67 | 12 |

| Total | 580 | 213 |

| EAST SOUTH CENTRAL | ||

| Kentucky | 120 | 75 |

| Tennessee | 95 | 24 |

| Alabama | 67 | 16 |

| Mississippi | 82 | 21 |

| Total | 364 | 136 |

| WEST SOUTH CENTRAL | ||

| Arkansas | 75 | 44 |

| Louisiana | 64 | 18 |

| Oklahoma | 77 | 27 |

| Texas | 254 | 69 |

| Total | 470 | 158 |

| EAST NORTH CENTRAL | ||

| Ohio | 88 | 40 |

| Indiana | 92 | 58 |

| Illinois | 102 | 62 |

| Michigan | 83 | 46 |

| Wisconsin | 71 | 36 |

| Total | 436 | 242 |

| WEST NORTH CENTRAL | ||

| Minnesota | 87 | 38 |

| Iowa | 99 | 48 |

| Missouri | 115 | 83 |

| North Dakota | 53 | 18 |

| South Dakota | 69 | 18 |

| Nebraska | 93 | 43 |

| Kansas | 105 | 42 |

| Total | 621 | 290 |

| MOUNTAIN | ||

| Montana | 56 | 20 |

| Idaho | 44 | 25 |

| Wyoming | 23 | 6 |

| Colorado | 63 | 26 |

| New Mexico | 31 | 7 |

| Arizona | 14 | 3 |

| Utah | 29 | 12 |

| Nevada | 17 | 7 |

| Total | 277 | 106 |

| PACIFIC | ||

| Washington | 39 | 12 |

| Oregon | 36 | 10 |

| California | 58 | 6 |

| Total | 133 | 28 |

| Grand total | 3,098 | 1,216 |

| Geographic division |

Percentage of counties decreased |

| New England | 19.4 |

| Middle Atlantic | 20.0 |

| South Atlantic | 36.7 |

| East South Central | 37.3 |

| West South Central | 33.6 |

| East North Central | 55.5 |

| West North Central | 46.7 |

| Mountain | 38.2 |

| Pacific | 21.0 |

1 Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930, Population, Vol. 1, op. cit.

This table shows that the highest percentage of counties decreasing in population are in those States which are primarily rural in character. In industrial New England and the Middle Atlantic States the counties which decreased in population were rural counties of the States. The largest percentage of counties decreasing in population were in the East North Central Division where a great industrial development, especially along the Great Lakes, tended to draw people from the rural sections.

A very significant fact in relation to the ability of the counties to act as effective agents in providing lands for recreation and in maintaining an organized recreational service is that comparatively few of the counties have a population of 100,000 and over. Of the 3,098 counties, only 167, or 5.3 percent, fall within this population classification, while only 7.2 percent of all the counties fall within the population classification of 50,000 to 100,000. On the other hand over 67 percent of all counties have a population under 25,000.

The following table shows the situation with respect to gross population classifications.

| Geographic divisions and States | Total number of counties | Number of counties with 100,000 or more population | Number of counties with 50,000 to 100,000 population | Number of counties with 25,000 to 50,000 population | Number of counties under 25,000 population |

| NEW ENGLAND | |||||

| Maine | 16 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| New Hampshire | 10 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Vermont | 14 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 9 |

| Massachusetts | 14 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Rhode Island | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Connecticut | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 67 | 16 | 12 | 19 | 20 |

| MIDDLE ATLANTIC | |||||

| New York | 62 | 20 | 13 | 22 | 7 |

| New Jersey | 21 | 11 | 4 | 6 | 0 |

| Pennsylvania | 67 | 22 | 17 | 16 | 12 |

| Total | 150 | 53 | 34 | 44 | 19 |

| SOUTH ATLANTIC | |||||

| Delaware | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Maryland | 24 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| Virginia | 100 | 0 | 2 | 20 | 78 |

| Virginia, city-counties | 24 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 18 |

| West Virginia | 55 | 1 | 11 | 8 | 35 |

| North Carolina | 100 | 3 | 13 | 32 | 52 |

| South Carolina | 46 | 3 | 5 | 22 | 16 |

| Georgia | 161 | 2 | 3 | 17 | 139 |

| Florida | 67 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 54 |

| Total | 580 | 7 | 19 | 96 | 242 |

| EAST SOUTH CENTRAL | |||||

| Kentucky | 120 | 1 | 5 | 17 | 97 |

| Tennessee | 95 | 4 | 2 | 23 | 66 |

| Alabama | 67 | 2 | 6 | 37 | 22 |

| Mississippi | 82 | 0 | 6 | 19 | 57 |

| Total | 364 | 7 | 19 | 96 | 242 |

| WEST SOUTH CENTRAL | |||||

| Arkansas | 75 | 1 | 4 | 21 | 49 |

| Louisiana | 64 | 2 | 4 | 19 | 39 |

| Oklahoma | 77 | 2 | 8 | 24 | 43 |

| Texas | 254 | 6 | 12 | 43 | 193 |

| Total | 470 | 11 | 28 | 107 | 324 |

| EAST NORTH CENTRAL | |||||

| Ohio | 88 | 11 | 13 | 33 | 31 |

| Indiana | 92 | 5 | 6 | 22 | 59 |

| Illinois | 102 | 9 | 12 | 26 | 55 |

| Michigan | 83 | 6 | 11 | 17 | 49 |

| Wisconsin | 71 | 2 | 13 | 22 | 34 |

| Total | 436 | 33 | 55 | 120 | 228 |

| WEST NORTH CENTRAL | |||||

| Minnesota | 87 | 3 | 2 | 14 | 68 |

| Iowa | 99 | 2 | 5 | 19 | 73 |

| Missouri | 115 | 3 | 3 | 19 | 90 |

| North Dakota | 53 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 49 |

| South Dakota | 69 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 68 |

| Nebraska | 93 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 82 |

| Kansas | 105 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 90 |

| Total | 621 | 12 | 13 | 76 | 520 |

| MOUNTAIN | |||||

| Montana | 56 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 54 |

| Idaho | 44 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 40 |

| Wyoming | 23 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 22 |

| Colorado | 63 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 55 |

| New Mexico | 31 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 29 |

| Arizona | 14 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 9 |

| Utah | 29 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 25 |

| Nevada | 17 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 16 |

| Total | 277 | 3 | 5 | 19 | 250 |

| PACIFIC | |||||

| Washington | 39 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 24 |

| Oregon | 36 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 28 |

| California | 58 | 10 | 11 | 8 | 29 |

| Total | 133 | 14 | 16 | 22 | 81 |

1 Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930, Population, Vol. 1.

| Geographic divisions | Number of States | Number of counties | Number of counties with 100,000 or more population | Number of counties with 50,000 to 100,000 population | Number of counties with 25,000 to 50,000 population | Number of counties under 25,000 population |

| New England | 6 | 67 | 16 | 12 | 19 | 20 |

| Middle Atlantic | 3 | 150 | 53 | 34 | 44 | 19 |

| South Atlantic | 8 | 580 | 17 | 44 | 116 | 403 |

| East South Central | 4 | 364 | 7 | 19 | 96 | 242 |

| West South Central | 4 | 470 | 11 | 28 | 107 | 324 |

| East North Central | 5 | 436 | 33 | 55 | 120 | 228 |

| West North Central | 7 | 621 | 12 | 13 | 76 | 520 |

| Mountain | 8 | 277 | 3 | 5 | 19 | 250 |

| Pacific | 3 | 133 | 14 | 16 | 22 | 81 |

| Total | 48 | 3,008 | 166 | 226 | 619 | 2,087 |

In the 96 metropolitan districts, as defined by the United States Bureau of the Census in 1930, 247 counties are wholly or partially included, while in the metropolitan region as defined in this report (radius of 50 miles from the center of a central city or cities), there are, of course, many more.

It is within these counties, subject to urban influence, that the greatest growth of population has taken place during recent decades; while in the very large numbers of rural counties is found the large decrease in population during the last decade.

Of the total of 3,098 counties, 36 are city-counties, that is they are comprised wholly within the boundaries of cities and where the city exercises the joint functions of a city and county government.10

10 The city-counties are: Baltimore, Philadelphia, Washington (District of Columbia), New Orleans (Orleans Parish), Denver, San Francisco, St. Louis, New York City (5 counties), and 24 city-counties in Virginia.

Practically all of the 166 counties having each, in 1930, 100,000 inhabitants or over are "urban" counties. The same may be said of the 226 counties with a population from 50,000 to 100,000.

The counties of the United States may be divided, therefore, into two general classes:

(1) Those that fall within influence of metropolitan and districts and regions.

(2) Those that are primarily rural in character.

It is within the first of these classes that county action for the preservation and utilization of lands for 54 recreation has chiefly taken place.

Of the 3,063 counties remaining after deducting the 35 city-counties, record is had (1934) of 113 counties, or only 3.7 percent, having acquired lands for recreational purposes.11

11 U. S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Park Recreation Areas in the United States, 1930, Bulletin No. 565, May 1932, 156 pp., tables. (See p. 43.)

The total area of recreational space owned by these 113 counties was 121,957.6 acres. The average area per county was approximately 1,079.3 acres.

The counties had thus provided recreational areas were distributed among 24 States. Such counties were most numerous in New Jersey, New York, Michigan, Wisconsin, Illinois, and California—States having heavy concentration of population and chiefly distinguished by urban growth.

Of the 73 counties reporting county-owned recreation areas in 1930, 44 were in 25 metropolitan districts. Fifteen others contained a central city with population ranging from about 15,000 to slightly over 55,000. Two others contained five and six small cities, respectively. Only 12 counties possessing recreation areas were more or less typically rural counties.

In 1930, 28 States were found to have enacted laws empowering counties to provide parks. No evidence of such laws was found in 20 States,12 although under general laws relating to the powers of counties the right to purchase lands for parks probably exists if the county authority desires to exercise it.

10 12 Playground and Recreation Association of America, County Parks, New York, 1930, 150 pp., illus., maps. (See pp. 16—48, 111—147)

| Geographic division | Number of States having County park laws | Number of States having no county park laws1 |

| New England | 0 | 6 |

| Middle Atlantic | 3 | 0 |

| South Atlantic | 5 | 3 |

| East South Central | 1 | 3 |

| West South Central | 3 | 1 |

| East North Central | 5 | 0 |

| West North Central | 5 | 2 |

| Mountain | 5 | 3 |

| Pacific | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 28 | 20 |

1 County Parks, op. cit., pp. 111—113.

Those States having no specific legislation concerning county parks included the 6 New England States (where the county government is feeble and very little utilized), 10 agricultural States, and 4 States where the predominating influence is urban. One of these States (Washington) has provided county parks, presumably under the general powers of the counties without specific legislation.13

13 Ibid, p. 111.

All the States in two of the most populous geographic divisions have provided the counties with the necessary legal authority to acquire and administer recreational areas (Middle Atlantic and East North Central divisions).

The total population of the States which have provided such legislative authority to counties is 95,805,491, and, if the State of Washington, where several counties have provided parks seemingly without specific authority, is included the total population in all States making provision for county parks is 97,368,887, or nearly 80 percent of the total population of the Nation. If the population of New England is eliminated, approximately 85 percent live in States which have made legal provision for county parks. New England is excluded for the reasons that the county is a weak governmental unit there, and the States, especially Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island, have assumed the responsibility of providing the types of recreation areas usually found in the more highly developed county park system.

It is to be noted that, with the exception of New England, the States having provided legislation empowering counties to acquire parks are found in every geographic section of the United States.

The first county park-recreation system was established in 1895, in Essex County, N. J. In a period of 39 years only 112 additional counties have followed the example of Essex County. The growth of county recreational systems until 1925 was very slow, but in the 5-year period from 1925 to 1930 the number of counties having recreation spaces more than doubled, and the total acreage set aside for recreational purposes approximately doubled.14

14 Park Recreation Areas in the United States. 1930, Bulletin No. 565, op. cit., p. 37.

What of the future of the county as a local governmental agency for providing recreation areas and for maintaining a general recreation service?

Since the great majority of the population of the United States is now living in States which have provided for legal action by counties in acquiring, developing, and operating land and facilities for recreation, it would be well for the 20 States lacking such laws to enact the necessary legislation (except in New England), even though the percentage of people affected (15 percent) would be small.

Based on the trend of county recreational development during the past two decades, it is reasonable to expect combined action by counties in the metropolitan districts and regions of cities, wherever the metropolitan district recreational plan is not established, and where State action does not provide all the desirable recreational spaces.

There is no standard for the amount of recreational space which the counties of the "urban" type should provide. Westchester County, N. Y., has reserved approximately 5 percent of the total area of the county for recreational purposes. This is at the ratio of about 1 acre to every 30 of the population (1930). Union County, N. J., has already reserved nearly 7 percent of the total area of the county for recreational uses, and the ratio of recreational space is 1 acre to every 73 of the inhabitants.

Cook County, Ill., has set aside in its forest preserve system about 5.5 percent of the total area of the county. The ratio of acreage to population is approximately 1 acre to every 120 of the inhabitants.

Essex County, N. J., has reserved nearly 5 percent of the total area of the county, and the ratio of recreational space to population is approximately 1 acre to every 211 inhabitants.

The above are examples of county accomplishments in highly concentrated population centers.

Erie County, N. Y., has reserved in its county system of recreation spaces only about one-fifth of 1 percent of the total area of the county, and the ratio is 1 acre to about every 565 of the population. This system, however, is as yet incomplete.

These few examples are presented to show trends as to ratio of county recreational area to population and not as bases for a desirable standard. However, it is suggested that the ultimate standard ratio of recreational area to population in county recreational systems should and will likely be far higher than the basic standard of 1 acre to every 100 persons in city systems. The desirability of preserving a generous part of all outstanding natural topographic features, including forested areas, in counties, especially counties in the vicinity of cities, will require, as a general rule, a high ratio of recreational area to population, ranging anywhere from 1 acre to every 20 persons to 1 acre to every 100 persons.

As has been shown in the discussion of metropolitan districts and regions, the States already have assumed a considerable part of the responsibility of providing recreational areas in "urban" counties. It is reasonable to assume that they will continue to do so. However, the greater percentage of the "urban" counties have the population and financial resources to assume a large share of the responsibility of acquiring, developing, and administering lands for recreational purposes, and of carrying on a year-round recreational service. There is need, however, in all these counties for comprehensive planning, studies, and surveys, a fundamental procedure that has hitherto been almost wholly neglected except in those comparatively few counties that have already established extensive systems of recreational areas.

It is desirable that a county planning commission or board be established in all the more populous counties, working in harmony with regional, State, and metropolitan planning boards.

The rural counties of the Nation present a far different problem. There are many more rural than urban counties, and fully half of them are decreasing in population. Most of them are financially weak.

Land ownership for recreational purposes is not so vital in these counties as in the urban counties. The most important problem is recreational program leadership. This does not mean, however, that publicly owned recreation spaces and facilities for the use of the rural population of the Nation are not desirable and important. The providing of such spaces should be not only the direct responsibility of the county, but should also be the joint responsibility of the State, the consolidated rural school, the local incorporated and unincorporated village, and small city communities. There is no standard as to the desirable amount of recreational area which counties of this type should possess, and there are no data on which to base consideration of a standard, as so few of them actually possess recreational areas.

Inasmuch as financial weakness is the chief bar to the rural counties providing the desirable recreation spaces for themselves and of maintaining a year-round recreation service, it is suggested that the formation of larger taxing units through the consolidation of two or more counties would be desirable, or, failing this, the setting up of recreation-administration districts through the cooperative union of two or more counties. The Michigan county park laws provide for cooperation between two or more counties in purchasing recreational properties, as do also some of the laws of other States.

The experience of the American Library Association in attempting to establish libraries and library service in rural counties has been disappointing. This association is now strongly in favor of districts composed of two or more counties in order to secure a broader financial base. On the other hand, the growth of agricultural extension work in rural counties has been phenomenal. This is a cooperative service program in agricultural economics and adult education, fostered by the extension divisions of agricultural colleges aided by the Federal Government. Financial participation comes from the county, the State, and the Federal Government. In 1931, 77.2 percent of the counties had agricultural agents and 43 percent of the counties had home demonstration agents.15

15 Recent Social Trends in the United States, 1933, op. cit., p. 507.

In providing a recreational service program under leadership in rural counties the same procedure may be followed as in the agricultural extension and home demonstration service program, using practically the same governmental set-up with the addition of recreation directors or leaders on the staff of the State extension service and in the counties. The State should employ the general State recreation director, while the counties or combination of counties would be responsible for the local director.

The States of New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Nebraska, Connecticut, Ohio, and Oregon have each provided a State recreation director on full time, while Oklahoma, Georgia, and South Carolina have such a director on part time.16

16 Information furnished by Mr. John Bradford, field secretary for rural counties, National Recreation Association, Sept. 5, 1934.

It is suggested that it would be desirable if there were employed on the staff of the extension division of each State agricultural college, or other State educational institution of higher learning dealing with rural regions, a State recreation director. It would be desirable, too, if in every county, or combination of two or more counties, there would be a county or district recreation director working under the general supervision of the State recreation director and in cooperation with the county agents and home demonstration agents, to the end that a recreational service program be developed and carried on among the rural population of the Nation.

Metropolitan Systems

In a national plan for the utilization of lands for recreation, the planning for the use of lands in the metropolitan regions of cities is next in importance to such planning in the cities themselves. Not only does it involve more or less frequent recreation service for the inhabitants of the principal cities of a kind which cannot effectively be supplied in them, but it must provide a service also for the inhabitants of a very large number of smaller municipalities and a considerable number of rural nonfarm and farm people.

The extent of the trend toward concentration of the population of the United States in metropolitan communities is not generally understood by the average citizen. The following table shows in general what has taken place during the past three decades.

| Year | Total population | 1/4 of population | 1/2 of population | 3/4 of population | |||

| Number of counties | Area (square miles) | Number of counties | Area (square miles) | Number of counties | Area (square miles) | ||

| 1910 | 91,972,266 | 39 | 23,243 | 312 | 887,829 | 264,868 | 1,068 |

| 1920 | 105,710,620 | 33 | 19,270 | 250 | 224,944 | 992 | 856,820 |

| 1930 | 122,775,046 | 27 | 14,431 | 189 | 170,517 | 862 | 767,403 |

1 Recent Social Trends in the United States, op. cit., p. 445.

This table shows an increasing geographical concentration each decade. In 1930, 75 percent of the total population was concentrated on about 25.8 percent of land area of the United States.

An interesting phase of this concentration movement is the trend toward the Atlantic Ocean, Gulf of Mexico, the Great Lakes, and the Pacific Ocean. The following table presents a summary of what has happened in this respect.

| Census year | Population within zone | Percent of total United States population in zone | Increase with in zone since preceding census | Percent of total of United States increase within zone |

| 1900 | 27,842,288 | 36.6 | 5,495,234 | 42.1 |

| 1910 | 35,633,796 | 38.7 | 7,791,508 | 48.8 |

| 1920 | 43,865,221 | 41.5 | 8,231,425 | 59.9 |

| 1930 | 55,413,567 | 45.1 | 11,548,346 | 67.7 |

1 Recent Social Trends, op. cit., p. 446.

In 1930 there were 93 cities of 100,000 population or more in the United States.17 The following table shows the concentration of population within this group of cities, and in the regions around them, within an arbitrary radius of 20 to 50 miles, the number of metropolitan regions being reduced to 63 by grouping cities close to each other.18

17 Fifteenth Census of the United states, 1930, Population, Vol. 1, p. 14, table 8.

18 Recent Social Trends, op. cit., p. 447.

| Year | Total population in metropolitan zones | Total population in United States | Percent which population in zones formed of total United States population |

Percent which increase in zones formed of total increase in United States since preceding census |

| 1900 | 75,994,575 | 28,044,698 | 36.9 | 46.4 |

| 1910 | 91,972,266 | 37,271,608 | 40 5 | 57.7 |

| 1920 | ,710,620 | 46,491,835 | 44.0 | 67.1 |

| 1930 | 122,775,046 | 59,118,595 | 48.2 | 74.0 |

About half of the population of the United States now lives within daily access of a city of 100,000 or more. This is 85 percent of the total population classed as urban.

The metropolitan districts comprise about 1.2 per cent of the total land area of the United States and have about 45 percent of the total population.19

19 U. S. Bureau of the Census, Metropolitan Districts, Population and Area (Fifteenth Census), Washington, D. C., Government Printing Office, 1932, pp. 6-7.

The density of population in the central cities was 8,380.4 per square mile, and in the outside territory 528.3 per square mile.20

20 Ibid.

These districts present some interesting population characteristics. Of all Negroes in the Northern States, 82.9 percent are in the metropolitan districts of those States. The corresponding figure for the Southern States is 16.9 percent. Of the foreign-born white population of the United States 74.9 percent is in metropolitan districts. The metropolitan districts have only 24 percent of the native white population.21

21 Metropolitan Districts, Population and Area (Fifteenth Census), op. cit., pp. 6-7.

Over 50 percent of the total population of the Nation between 25 and 44 years of age is in metropolitan districts, whereas only 29 percent of the children under 15 years and about the same percent of the persons 65 years of age and over are to be found in the metropolitan districts.

In the central cities, the females outnumber the males with but few exceptions. The reverse is true in the suburbs. "In nearly every metropolitan district the percentage of foreign-born white in the central city was higher than outside, which condition is also true of the Negroes. With but few exceptions the percentage of children under 15 years of age in the population is higher outside than in the central city."22

22 Ibid., p. 8.

The increase of population in the metropolitan districts from 1920 to 1930 was very much higher (27.2 percent) than for the country as a whole (16.11 percent).

During the decade 1920—30, there were added to the central cities 5,622,986 inhabitants and to the outside territory 4,362,930. While the numerical growth was greater in the central cities than outside, the rate of growth outside was approximately 29 percent as compared with about 20 percent in the central cities. This rapid rise of inhabitants in territory outside central cities23 will probably continue during the present decade (1930—40), indicating that emphasis on planning land use for recreation should be centered on territory outside central cities in order to prevent the recurrence of the conditions as to lack of open space for recreation prevailing in so many of the central cities, and at the same time to provide types of recreation areas which both the central city and the outlying cities cannot effectively provide for themselves.

23 Population and Area (Fifteenth Census), op. cit., p. 6.

A clear distinction should be made between a metropolitan region and a metropolitan district as defined by the United States Census Bureau. The average radius of the 96 metropolitan districts set up by the United States Census Bureau is about 11 miles. On the other hand, as far as the recreational use of land is concerned, a metropolitan region is based on accessibility for frequent use of areas set aside for recreation. Modern transportation makes possible the effective frequent use of recreational areas within a radius of at least 50 miles of a central city or cities. For planning purposes the central city is excluded, as are also the larger municipal corporations in the region, since provision for recreational areas within their borders, according to a minimum standard of 1 acre to every hundred inhabitants, is conceded to be a definite responsibility of the cities themselves.

Planning lands for recreational use in a metropolitan region, therefore, is concerned primarily with preserving lands desirable for recreation in the more open sections of the region where the density of population is relatively low. However, in such planning in a region around a central city it is desirable to establish zones based on varying distances from the central city.

The first zone might include the area outside the central city in the metropolitan district as defined by the United States Census Bureau. Special attention should be given to the reservation of lands for recreation purposes in this zone for the reason that the movement of population from the congested sections of the central city is into this zone. Unless liberal provision is made for open spaces for recreation in this zone in advance of growing congestion, a repetition of the lack of open spaces in the congested sections of the city will result, thereby defeating one of the primary purposes of the movement of the people from the central city or cities.

While naturalistic areas of considerable extent may be secured in the zones around most of the central cities, the recreational plan for such zones should take into account smaller areas of the type of large parks and neighborhood playfield parks, commonly found in cities.

In the second or outer zone planning should primarily be directed toward preserving large naturalistic areas of the forest type and the preservation of outstanding topographic features such as streams and stream valleys, water front areas along rivers, lakes, or ocean, and elevated areas presenting varied scenic attractions.

The planning, acquisition, development, and government of land for recreation in metropolitan districts or regions is, from an administrative viewpoint, a very complex problem. It involves several governmental agencies among which may be listed the following:

1. The Central City.—The responsibility of central cities in providing recreational areas within or very near their boundaries according to a minimum standard of planning (1 acre to every hundred population) has already been stated. Many cities, however, have also the legal right to have assumed responsibility for acquiring, developing, and administering recreational properties in their metropolitan districts and regions.

The Denver mountain park system is an outstanding example. Phoenix, Ariz., has such a metropolitan park of 14,640 acres. In 1930, record was had of 186 cities having 381 parks outside their boundaries with a total of nearly 90,000 acres.24 In 1925—26 there were only 109 cities owning such properties.25 The trend is evidently toward cities extending their recreation acreage into their outside metropolitan regions.

24 Park Recreation Areas in the United States, 1930, op. cit., pp. 11—13.

25 Park Recreation Areas in the United States, op. cit., p. 11.

2. Incorporated communities (villages, towns, and small cities) in the metropolitan district and region outside central cities. Standards for general planning of recreation areas within these have been hereinbefore stated as follows:

(a) Cities of 10,000 and above, 1 acre to every 100 inhabitants.

(b) Cities from 5,000 to 18,000, 1 acre to every 75 inhabitants.

(c) Towns (very small cities) from 2,500 to 5,000, 1 acre to every 60 inhabitants.

(d) Villages from 1,000 to 2,500, 1 acre to every 50 inhabitants.

(e) Villages under 1,000, 1 acre to every 40 in habitants.

These standards would apply also to unincorporated communities whose population would bring them under any of the classifications above. It should be noted, however, that certain types of areas which such small or large incorporated or unincorporated places would be expected to provide for themselves, if they were entirely outside of a metropolitan region, might be provided by the central city itself through an extension of its system of recreational areas into the outside metropolitan district or region or by other agencies, such as the counties, metropolitan park districts, or the State. This is especially true of the picnic, forest type of area.

3. Counties.—While it is clearly apparent that counties have made definite, constructive contributions to the solution of the problem of recreational planning and administration in metropolitan districts and regions, still, since both a metropolitan district and a metropolitan region usually comprise parts of or the whole of two or more counties, it is very difficult to secure uniformity of planning or administration in a metropolitan district or a metropolitan region on a county basis.

4. Special Park Districts.—These districts as set up in Tacoma, Washington; in Illinois, etc., have a peculiar status in that their jurisdiction extends over the recreational areas of the central city and usually a territory outside the central city to an extent determined by the courts and established by a popular vote. From time to time the boundaries of the districts may be extended by the same methods through which the original district was established. The districts usually have special taxing and bonding powers and legislative and police powers.

The special park district has proven a fairly effective planning and administrative agency for handling the planning and administration of recreational areas and facilities in a central city and in a comparatively narrow zone around the central city. It is probably better adapted for use in connection with cities under 200,000 population than the larger cities for the reason that the administrative problems of handling both varied and intensively used areas within the city, as well as in a zone around a central city, become too complex and burdensome for efficient government.

5. Metropolitan Park Districts.—These are similar to the special park districts except that existing metropolitan park districts do not have jurisdiction over the recreational areas within central cities, although they may own and administer recreation properties in central cities independent of the local system.

The Boston Metropolitan Park System and the Rhode Island Metropolitan Park System are in reality State systems. Ohio is the only State in the Union which has enacted legislation providing for special metropolitan park districts. The basic unit in any metropolitan park district created under this law is the county in which the principal or central city is located, but by vote of the people living in adjacent territory the boundary of the district can be indefinitely extended. The Cleveland Metropolitan District includes the whole of Cuyahoga County and parks of several other adjacent counties.

6. The State.—Many States own and administer recreation areas within the metropolitan regions of cities as the result of geographic, topographic, social, economic, political, or philanthropic factors or as a result of a combination of two or more of these factors. In Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island there is not a single State recreation area which is not within the metropolitan region of one or more of the cities of those States and, in many instances, areas in one State are within the metropolitan regions of another State.

This is due primarily to the very small geographic areas of these States. The same situation exists in northern New Jersey. Not infrequently areas of outstanding topographic importance are within the metropolitan regions of cities and are of such magnitude and importance for recreation that the State is warranted in acquiring them, especially if such acquisition is beyond the financial power of local communities. Large cities pay a heavy percentage of taxes to the State. This economic factor leads to demands that the State locate some recreational areas within the frequent-use radius of the cities. Political considerations sometimes influence the location of State recreational areas. Gifts of lands to the State by philanthropists have been the origin of some State parks in metropolitan regions (e. g., Detroit). Whether by deliberate planning as the result of social-economic influences, or because of other factors, in the future the States will likely continue to play an important role in land utilization for recreation in metropolitan regions.

7. Federal Government.—What the Federal Government has done in providing recreational areas in metropolitan regions of cities has, up to the present time, been more the result of chance than of deliberate planning for the purpose of aiding cities to secure such benefits. However, if the plans are carried out for the purchase of submarginal lands in the metropolitan regions of cities, or near such regions and these are turned over to the States or some local governmental agency for administration, the role of the Federal Government in the planning and development of such areas may become a very important one. If there is ever developed a plan of Federal monetary aid to cities, counties, metropolitan park districts, or States in acquiring recreational areas in metropolitan regions, the role of the Federal Government will also be an exceedingly important one.

Among these several different governmental agencies which, up to this time, have actually provided recreational areas in metropolitan regions, standards of planning have been developed for the municipalities only. For the territory outside central cities, exclusive of municipal corporations within the metropolitan region, there are no standards as to the desirable number of recreational areas to be set aside. For the guidance of those governmental agencies, such as counties, metropolitan park districts, and States, which have provided such regional areas for recreation, there are no definite standards.

There is no plan or policy developed governing the division of responsibility among these several agencies. There is likewise no plan or policy developed concerning the desirable type of administrative unit for the planning, acquisition, development, and operation of regional areas for recreation.

Conclusions

In the absence of any standards in planning for recreation in a metropolitan region, exclusive of central cities and other municipalities in the region, the most that can be done is to present some general observations and suggestions concerning the problem.

First. Present-day transportation methods make possible the frequent use of recreation areas in any suitable location within a 50-mile radius of the central city (or cities), and this zone might be accepted as the metropolitan regional planning unit until such changes occur in transportation methods as to modify it.

Second. Insofar as practicable within the radius of 50 miles the recreational areas should be distributed in zones of varying distances from the central cities. Zone 1 should include all the areas from the boundary of the central city to 10, 20, or 30 miles, depending on the extent of the area that has now or is tending to become territory with a density of 100 persons per acre and upwards; zone 2 should comprise all the area beyond the more thickly populated zone.

In the inner zone the character of recreational areas will likely be somewhat different from that of areas in the outer zone. In many instances the inner zone areas will approximate the types of areas which are found in the central city itself, although the system of open space may include naturalistic areas characteristic of those desirable in the outer zone.

In the general planning of recreational areas in both zones of a metropolitan region, special and first attention should be given to preserving natural topographic features, such as streams and stream valleys with adjacent highlands; lakes and lake shores; lands along rivers; ocean fronts; areas of rugged topography presenting varied scenic attractions; swampy areas (especially in the outer zone) suitable as sanctuaries for certain species of wildlife; areas possessing especially fine stands of trees and shrubs and other forms of flora; and areas of special historic significance to the region.

Third. The responsibility for providing recreational areas in a metropolitan region logically and practicably should be assumed by several different public administrative agencies, chief of which are:

(a) The State.—The responsibility of the State may primarily include the preservation, planning, development, and administration of naturalistic recreational areas, chiefly of large acreage, in the outer zone (20 to 50 miles from the central city) of the metropolitan region.

(b) The Metropolitan Park District.—The metropolitan park district plan embodies a comparatively new form of governmental agency, not yet widely used. This plan has merits, however, which recommend its wide adoption as an effective method of securing comprehensive planning in any metropolitan district or any other section of the metropolitan region outside a central city and of securing a unity of financing and administration of recreational services in a logical unit. It cuts across boundaries of existing civil divisions, such as townships and counties, which generally bear no relation to the common problems of the people living in a metropolitan district or region.

The Ohio metropolitan park law providing a method of setting up metropolitan park districts and regions of the cities of that State, is perhaps the best example of legislation bearing on this plan, although the Boston metropolitan park law is worthy of careful consideration.

The function of a metropolitan park district is to assume major responsibility for the general planning, acquisition, development, and operation of recreational areas in the zone extending from near the boundaries of a central city to the limits of the territory that has already become suburban-urban in character or is tending that way, including also all areas of open country between the more developed sections, and perhaps somewhat beyond them. Such a zone might range in width from 5 to 30 miles, depending on the size of the central city or cities, the extent to which suburban development has progressed, and the rate at which it is expanding.

(c) The County.——The county may logically function as a metropolitan recreational-planning and administration agency in the zone as defined for the metropolitan park district, where no such metropolitan park agency exists. This will frequently involve action on the part of two or more counties in order to cover the same territory that a metropolitan park district would include. Unified comprehensive planning is difficult to secure under this condition.

Fourth. It is probable that central cities will continue to acquire and administer recreational areas in their metropolitan districts and regions. It is therefore, strongly recommended, as a general policy, that the cities give first attention to acquiring, developing, and operating areas within their own borders or very near their borders. Very few cities have at present more than 50 percent of the desirable number of types and acreage of recreation areas within their boundaries.

This lack is without question one of the primary causes of the rapid decline of population in the older and more congested parts of cities during the past decade. Property values are falling in these areas of declining population. The areas are becoming more and more a civic and social menace and burden, while at the same time public expenditures for their care and control are mounting. It is suggested that good city management could well include the expending of large sums of money for the purchase of many blocks in blighted areas and for their development as parks, playgrounds, and playflelds. This alone will make such areas desirable as living places again, raise and stabilize property values, bring in greater income in taxes and other types of revenues, decrease ill health and lawlessness, lessen the expense of health supervision and of maintaining law and order.

Fifth. There is urgent need of comprehensive planning for recreation in practically all the metropolitan districts, as defined by the United States Census Bureau (1930), and in metropolitan regions as defined in this report. Among few metropolitan regions having such plans at the present time are New York City, Philadelphia, Chicago, and St. Louis.

It is recommended that a metropolitan planning commission or board be set up at the earliest possible time in each metropolitan region, and that such board or commission include representatives of existing city and county boards and a representative of the State planning board, as well as outstanding citizens at large.

If legislation is lacking for the creation of such boards, appropriate bills should be drafted and presented to the legislatures of the several States having metropolitan districts and regions, and a determined effort made to secure their passage.

Recognizing that a movement for the study and planning of metropolitan districts and regions does not usually start automatically or spontaneously, it is further recommended that State planning boards assume leadership in fostering the formation of such metropolitan boards, in drafting and presenting appropriate legislation, and in the organization of metropolitan associations of citizens to aid in furthering the movement.

3. STATE COMPONENTS

State and Interstate Systems

Either through passage of some form of enabling legislation or through actual acquisition of lands all but two of the States have recognized that provision of facilities for recreation is a legitimate function of State government.

The responsibility of the State appears to be to acquire, develop, and maintain for public use and enjoyment such areas of land and water as will meet with reasonable adequacy such needs of its own people for inspiration, nature education, and active recreation, and other recreational needs as are not the responsibility of local political subdivisions or of the Government of the United States.

In advance of preparation of this section, a number of men and women, possessing either long experience in State park administration, or serious students of the whole broad subject of recreation, were consulted with respect to certain important problems related to State administration of lands and waters for recreational purposes. Most of the recommendations which follow arise more or less directly from the comments made by this group.

Classification of Holdings

The majority of those persons consulted were agreed that some form of classification of State recreational holdings was desirable, though the suggested classifications submitted by them varied widely in number and definition. Consideration of the subject on the basis of their replies and of first-hand knowledge of the existing situation appeared to indicate the desirability of comparatively few designations, with as clear cut distinction as possible between the various types, and with a nomenclature uncomplicated and most likely to be accepted fairly readily by the public.

As one means of assuring suitable administration practice with respect to each classification or type, and in order that the using public may have a reasonably definite concept of the character of the various types, it would be well for the several agencies of the States entrusted with administration of lands and waters set aside primarily or wholly for leisure time use, to give serious consideration to the following proposed classification of such properties:

State Parks.—State parks are those areas of considerable extent in which are combined either superlative scenic characteristics and a fairly varied opportunity for active recreation or distinctive scenic character and exceptional opportunity for active recreation.

Essential to the character of any State park is the preservation of the native landscape and of native fauna to the extent that provision and enjoyment of active recreation-use facilities shall not be permitted to destroy or materially to impair valuable landscape features or to injure wildlife or its natural habitat; and further that all of its natural resources shall be withheld from commercial utilization.