|

National Park Service

Recreational Use of Land in the United States |

|

SECTION V. EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES OF RECREATION AREAS

1. EDUCATIONAL RECREATION

Enjoyment of a thing is enhanced through understanding. The program of presenting and analyzing the salient features of parks and monuments has been motivated by the desire to increase the visitor's enjoyment through making the things about him more intelligible.

The technic of presentation is unique in many characteristics, and gives promise of untrammeled future development. Because it is, or can be made, adaptable to a great variety of recreational areas, elements of the technic are presented.

PHOTO 34.—A hiking party under the escort of a ranger naturalist. A naturalist has done his work well if he has given either the information sought or through his information increased the enjoyment of the visitor. Photo by Allan Rinehart. |

PHOTO 35.—A campfire scene at Tuolumne Meadows, Yosemite National Park, Calif. Every evening during the summer season visitors to this glorious High Sierra country gather around the cheerful fireplace. |

The Educational Program of the National Parks

While the national parks serve in an important sense as recreation areas, their primary uses extend far into that fundamental education which concerns real appreciation of nature. Here beauty in its truest sense receives expression and exerts its influence along with recreation1 and formal education. To me the parks are not merely places to rest and exercise and learn. They are regions where one looks through the veil to meet the realities of nature and the unfathomable power behind it.2

1 Editor's note.—Here again, there is a different interpretation given to the scope of the term recreation. Recreation, as used throughout this report, connotes all of those activities included in the statement of Dr. Merriam, and, in this sense, recreation is the primary purpose of the national parks.

2 Merriam, John C., A National Park Creed, National Park Bulletin, No. 8, July 1926, p. 3.

To provide each visitor to a national park with an opportunity to interpret and appreciate its superlative features has become the goal of all those interested in the highest use of national parks, and has led to the establishment of an educational program to attain this end. In this program there is little which pertains to classrooms, textbooks, or other formal educational methods. The average visitor wants to see and learn through his own observation, and seeks guidance from someone who knows.

The main objectives of the educational program have been:

1. Simple, understandable interpretation of the major features of each park by means of field trips, lectures, museums, and literature.

2. Emphasis upon leading the visitor to study the real thing rather than utilizing second-hand information. Typical academic methods are avoided.

3. Utilization of a highly trained personnel with field experience, able to interpret to the public the laws of the universe as exemplified in the parks, and able to develop concepts of the laws of life useful to all.

4. A research program which will furnish a continuous supply of dependable facts suitable for use in connection with the educational program.3

3 Bryant, H. C., and Atwood, W. W., Jr., Research and Education in the National Parks, National Park Service, 1932.

Endeavor has centered upon placement of trained scientists or historians in every park, who act as curators of natural treasures, and as technical advisers on scientific features; and who, with the help of temporary naturalists or historians, conduct a five-point program consisting of guided trips, campfire lectures, museum projects, and a study of nature trails and useful publications.

With the establishment of historical parks and monuments has come the need for a specialized type of educational program dealing with history. The visitor must be aided to visualize historical events as portrayed by fragmentary relics left to view. Restored buildings and earthworks turn the visitor's mind to conditions and events. Museums are necessary to interpret the local story, and to present the antiquities of the period. The interpreter must be an enthusiast with a thorough background of American history. In general, the educational method is comparable to that used in the biological parks.

PHOTO 36.—The archaeological museum at Mesa Verde National Park, Colo. Patterned after the Cliff Dwellers' motif, the building itself is of educational value. |

PHOTO 37.—Visitors at telescope at Yavapai Museum, Grand Canyon National Park. |

Guided Trips.—Guided trips constitute a most important and unique part of the program. They afford the visitor real experience where first-hand information involving all five senses is obtained, affording clear and lasting mental concepts. Then too, the parks are better fitted for this type of program than is the regular educational institution because of the quality of the historic and scientific features available.

The method stressed is expressed in Agassiz's old dictum: "Study nature, not books." The enthusiasm of a ranger-naturalist is contagious. He is able to make a trailside interesting. He brings senses seldom used into prominence. Plants are recognized by odor and taste, birds by call note and song, and trees by the feel of the barks. Geological stories are made plain through careful observation. Leading events in history are made interesting through acquaintance with historic landmarks. Too often a study of biology is sought through tedious dissection and microscopic analysis; too seldom is there study of the living thing in its natural environment.4

4 Bryant, H. C., Nature Guiding, American Nature Association, Bull. 17, 1925.

A parks official has done his work well if he has opened visitors' eyes and unstopped their ears, interpreted the findings of the specialist to the layman, demonstrated how fascinating it is to study geologic and historic features and living things first-hand, and left a vision of the great natural processes involved.

Walking trips under the escort of a ranger-naturalist are routed through areas rich in the natural phenomena especially exemplified in the park, and the features of outstanding interest along the way are discussed. In parks and monuments where history is prominent in the educational program, the ranger-historians stress first-hand acquaintance with scenes in which major human events have transpired.

Guided trips vary in length from an hour to several days, such as are conducted into the mountainous back country. In many parks specialized trips are added for those especially interested in rocks, trees, wild flowers, insects, birds, or mammals.

One of the most popular innovations in the naturalist program is known as the auto caravan. Visitors driving own automobiles are conducted to points of special scenic, historic, or scientific interest. Daily caravan trips, under expert guidance of a trained naturalist or historian, are scheduled in all of the major national parks, and the demand for this service is increasing rapidly. Here again there is wide variety in trips offered. In Yellowstone, a game-stalking caravan; in Yosemite, a history and an Indian legend caravan; and in Crater Lake, a rim drive caravan.

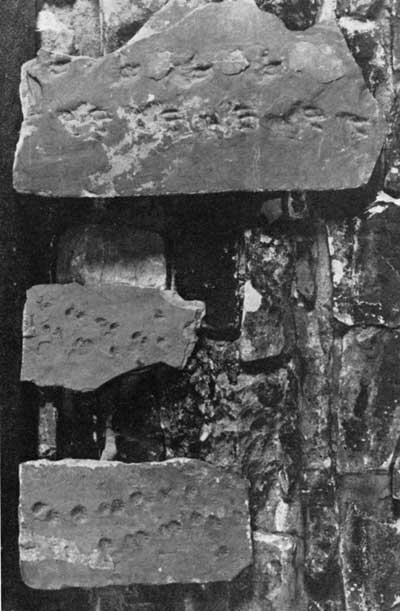

PHOTO 38.—Prehistoric animal tracks (in Yavapai Museum), Grand

Canyon National Park.

Lectures and Campfire Talks.—Park visitors are keen to utilize evening hours at a campfire program. People gather at hotels, lodges, and campgrounds, join in community singing, and listen to musical and educational programs. A prime feature of all these programs is a talks by a naturalist or historian, who explains various scientific or historic features of the park. Both motion pictures and lantern slides are used for illustrations. Interest and attendance have brought about improved equipment in the form of outdoor amphitheaters providing comfortable seats and suitable projection equipment.

Lectures vary widely in subject and method of presentation so as to fit location and type of audience. Around a small campfire in a campground the program is very informal, whereas at central locations the presentation may be more formal and with less opportunity for questions from the audience. Special animal lectures are given in several parks at the bear-feeding platforms. Dependable information on animal life, given with live specimens as illustrations, has proved very successful.

PHOTO 39.—Column of stones showing structure of canyon wall

(in Yavapai Museum), Grand Canyon National Park.

Museums.—An essential part of an interpretative program is the park museum and the orientation station. In the 24 national parks there are 19 museum buildings, and museum exhibits housed in headquarters buildings are found in 7 other parks. Museum displays have been developed in at least six of the national monuments, and there are many new museum projects. This array of museum buildings and displays had its simple beginning in 1921, entered a state of rapid development with the beginning of the Yosemite and Yellowstone museums in 1924, and has continued its rapid growth up to the present time. Under the emergency programs of 1933—36, the total number of National Parks Service museums will be increased to 66.

Park museums have been designed to help people understand what they have seen and to act as an index to what they may see in the park. Graphic devices and objective materials have been used to organize the local story and relate it to the national story. In some cases a central museum, as in Yosemite, has rooms devoted to geology, biology, ethnology, and history; in other cases, as in Yellowstone, wayside museums have been provided, each one specializing in and explaining nearby phenomena—rock formation, geysers, history, and animal life. A new museum in a restored log cabin in the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees in Yosemite tells the story of the Big Tree. Museum wings to administration buildings in southwestern monuments outline the significance of the areas and exhibit the artifacts obtained from pueblo ruins which constitute the chief features of these monuments. A staff of museum curators and preparators is maintained to develop the museum program.

PHOTO 40.—Trailside exhibit by beaver dams in Yellowstone National

Park, Wyo. The exhibit tells the history of the Fur Trade Era in the

West and gives pertinent life history facts concerning the beaver.

Orientation Stations.—As a means of determining the best methods of helping visitors, two notable educational experiments have been instituted. Under the direction of Dr. John C. Merriam, president of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, a lookout station was built at Yavapai Point on the South Rim in Grand Canyon National Park. Before installation of apparatus, a number of prominent scientists spent several weeks at Grand Canyon studying the problem of interpretation. As a result, the following devices were instituted: Telescopes and descriptive exhibits mounted on the parapet, supplemental transparencies, photographs, and diagrams; specimens and exhibits inside the exhibit room; and a guide leaflet describing the function of the apparatus, outlining the four main points explained—the forces involved in making the canyon and its walls, the history of earth building, the record of life through the ages, and the formation of Grand Canyon as affecting life of today.5

5 Grand Canyon Committee, National Academy of Science. Guide to Parapet Views at Yavapai Station, Grand Canyon, 1931.

The parapet views are so arranged. as to designate features of extraordinary interest, to give closer views in many instances by the use of the telescopes or field glasses, to give small close-up views with photographs accompanying the telescopes, to illustrate the localities with specimens, and to point out trails by which main features can be reached. One telescope permits a view of the rushing, muddy Colorado River; another the top of Cedar Mountain; and others, the various strata. In the cases may be seen the tools used by the river in cutting its channel—mud, silt, sand, pebbles, and boulders. A sample of the water from the river shows the large amount of sediment carried. Other cases contain specimens indicating crustal movement, oldest rocks of the canyon, remains of ancient life, and present-day life.

A geologic column constructed of actual rocks brought from the strata in the canyon forms a notable exhibit at the southwest corner of the porch. Alongside is a fossil column which shows the evidences of life that have been found in the different geological horizons. A remarkable block of rocks illustrating an unconformity of hundreds of millions of years is displayed at the rear of the observation porch. Here also are several large sandstone slabs exhibiting fossil footprints.

Supporting exhibits in the interior room amplify by means of transparencies, specimens, motion pictures, and lantern slides the story of the canyon as told on the parapet. Exhibit cases are oriented to correspond to the parapet views in the cases and are similarly numbered. Automatic projecting machines show films of the Colorado River in action.

Largely self-operating, this station is unique in its construction, installation, and method of presentation. It has demonstrated that technical science may be presented in an effective, convincing way to park visitors. A similar lookout station has been erected in Crater Lake National Park, where the additional attempt is made to convey aesthetic appreciation to the public.

A second educational experiment was initiated through a fund made available by the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial and administered by the American Association of Museums under Dr. H. C. Bumpus. This project began with the development of a natural-history museum at Yosemite. Later, it included the organization of a complete educational program for Yellowstone, with major emphasis on trailside museums of which four, architecturally attractive, have been built at strategic points to portray local features. One presents a general picture; another, the history of the region; another, geysers another, rock formations; and still another, biological features. In addition, there was developed the trailside exhibit as a method of explaining such features as the Obsidian Cliff and a beaver dam. New types of geological and biological exhibits were developed, and the presentation has successfully served the needs of the public.

In connection with the development of a complete educational unit in Yellowstone, it was evident that the motorist needed some guidance toward his understanding of park features. This realization led to the preparation of a publication entitled "Trailside Notes."6 The pamphlet is arranged in two columns with vignettes giving the outlines of the particular points of interest to be noted along the route. Below each drawing is a brief, but reliable, statement regarding the natural history features. Trailside notes have been worked up for several of the main-traveled routes in Yellowstone, with the result that the motorist may add greatly to the value of his visit to the park.

6National Park Service. Trailside Notes for the Motorist and Hiker, 1933.

Nature Trails and Exhibits in Place.—The nature trail is an efficient method of helping park visitors get acquainted with interesting geologic and biologic features along a trailside. There are always those who prefer studying things quietly by themselves; labeled rocks, trees, and plants fulfill this requisite. Specially designed metal labels are inconspicuous to all except those interested in them.7

7 Lutz, F. E., Nature Trails, an Experiment in Out-Door Education, Amer. Museum of Nat. Hist., Miscl. Publ. 21, 1931. Carr, W. H., Blazing Nature's Trail, The Nature Trails and Trailside Museum at Bear Mountain, 1929 Amer. Museum Nat. Hist., New school series No. 3, 1929.

Self-guiding nature trails are now available to the public in many parks. Glacier National Park has five such trails. In Mount Rainier more than 600 metal labels are used along developed trails.

In a number of the parks certain features along permanent trails and roads have been labeled and termed "exhibits in place." A good example of this is seen at Grand Canyon, where trails have been constructed leading to localities of particularly important geologic features. Markers calling attention to fossil shells and sponges in the Kaibab limestone are placed along major trails. Others are placed at localities where fossil footprints and fossil plants may be seen. In Yosemite, rocks on Sentinel Dome are labeled, as are numerous other features in various parks.

Small exhibits properly sheltered from the weather and placed near interesting features are termed "trailside exhibits." A series of these placed near the loop road in Yellowstone explain rock formations. One placed alongside a beaver dam portrays the part played by the beaver in early American history, the engineering ability of the animal and its economic uses of the present. Parking spaces are provided nearby, and visitors noting the exhibit stop and study it. This type of portrayal is certain to have extended use in other parks.

Small orientation stations consisting of a map or large photograph with all points named are in use in several parks. For example, enlarged photographs, rustically framed, picture what is seen from Valley View in Yosemite.

Originally wild flowers were exhibited in suitable containers, and were properly labeled. A recent improvement is the exhibition of wild flowers growing in gardens, especially arranged for study. The most pretentious garden of this kind is to be found in Yosemite. One part exhibits plant communities; the other, plant relationships. The whole is a colorful and useful adjunct to the museum.

Libraries.—Most of the major parks have built up small reference libraries for the use of the educational staff. In only a few instances, however, has it been possible to provide public reading rooms. In Yosemite there is in the museum building a very attractive library much used by the public. Yellowstone and Mesa Verde also have developed fine technical reference libraries used by the staff but open also to the public. Branch county libraries have been established in two or three parks, but the books available are intended primarily for the use of park employees. Plans are being made for development of libraries in historical parks. With the increase in use of the park educational facilities by field classes from colleges, universities, and high schools, it is becoming essential that complete reference libraries be available in all major parks. This need is being met as rapidly as possible.

Publications.—The publications of the National Park Service are of seven types:

1. Printed circulars of information on each park, and well illustrated books such as the National Parks Portfolio, Glimpses of Our National Parks, and Glimpses of Our National Monuments. All but the National Parks Portfolio are for free distribution.

2. Miscellaneous folders, leaflets, and circulars regarding the various historical areas, parks, and monuments rotaprinted in the Miscellaneous Service Section of the Department of the Interior. These are for free distribution.

3. A series of leaflets entitled "Making of American Scenery." Only one has been issued, and that a number of years ago.

4. A series of more technical reports dealing with the geology, fauna, and flora of various parks.

The latter two series (3 and 4) are available only from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C., at a cost price, as is the National Parks Portfolio.

5. Printed motorists' guides for several of the major national parks, also location maps, all of which are distributed free.

6. Miscellaneous mimeographed press bulletins and radio talks are issued by the Washington office.

7. Miscellaneous mimeographed press bulletins, memoranda, and reports, including the Nature Notes, are published in a number of the major parks. Grand Canyon, however, has ceased to publish Nature Notes because of lack of funds. In the case of Yosemite, Nature Notes is printed on a job press. This publication contains a series of short articles on natural history subjects and serves to acquaint the visitor with the interesting features of the park. Articles pertaining to discovery, early trade routes, and happenings with the Indians are frequently included. Several of the parks have also issued mimeographed manuals of information and manuals of instruction for use by the educational staff. The recommendation has been made that all Nature Notes be combined and issued as one publication in the Washington office. This cannot be done now, as there are no funds for the purpose.

Some very useful books and pamphlets have been issued privately, or by other Government bureaus. The Carnegie Institution of Washington has published a number of fine reports dealing with paleontological research in Grand Canyon. Two large volumes, one on Yosemite and the other on the Lassen Peak region, dealing with vertebrate fauna, have been issued by the University of California Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. A splendid series of papers covering researches made in Yellowstone National Park has been issued by the Roosevelt Wildlife Experiment Station. The United States Geological Survey has recently published an illustrated volume on the geologic history of the Yosemite Valley. The United States Bureau of Biological Survey is responsible for the pamphlet dealing with the Mammals and Birds of Mount Rainier National Park.

Guidebooks for various parks have been issued privately: Haynes' Yellowstone Guide; Hall's Yosemite Park Guide; Hall's Sequoia Parks Guide; and Elrod's Glacier Parks Guide. Operators in several parks have cooperated by issuing information manuals for their employees.

The Stanford Press has issued a series of volumes dealing with the western parks, beginning with Oh, Ranger!, followed by one on the Grand Canyon, one on the Big Trees, and another on Zion and Bryce National Parks and One Hundred Years in Yosemite.

Up to the present, owing to lack of Government funds for printing, more papers have been issued by outside organizations than by the National Park Service. Many of the special papers have been offered first to the Service for printing, but the authors, discouraged by the long wait for funds, have taken back the manuscripts, and had the books privately printed.

There is real need for better support of the publications work in order that this strong educational force may assume its proper place in the educational program.

College and University Field Classes.—Utilization of the national parks and national monuments by universities and colleges as outdoor classrooms to supplement academic study of the natural sciences is increasing. Many of the outstanding educational institutions of the country are taking advantage of the exceptional opportunities for such field work, notably Princeton University, Clark University, the University of Virginia, Western Reserve University, Montana State University, the University of Missouri, the University of North Carolina, the University of California, and the University of Hawaii.

Geology, botany, and zoology are the subjects most commonly studied in the parks, but recently an art school was established in Glacier National Park. The work provides university credit in all of these cases.

It is desired to encourage such use of the parks and monuments, for it is realized that these areas are ideal outdoor laboratories for practical study of geology, biology, archeology, and other field sciences.

The Federal Government cooperates gladly with all such study groups, arranging facilities so that field work and demonstrations can be most effectively accomplished. Members of the educational staff in the various parks render valuable assistance to students and teachers.

Yosemite School of Field Natural History.—The Yosemite School of Field Natural History is a summer school for the training of naturalists, where emphasis is placed on the study of living things in their natural environment. The school was founded in 1925 in answer to a demand for better-trained naturalists for the Yosemite Nature Guide Service. Furthermore, there was need for a training not furnished by the universities. The teaching staff is composed of university professors who donate their time, and members of the Yosemite naturalist service staff.8

8 1930, Yosemite School of Field Natural History, Nature Almanac (American Nature Association), pp. 139-140.

More and more a bachelor's degree is considered a minimum of entrance; works is of the graduate school type. Students are limited to 20, and they are housed in a circle of tents. Though no university credit is offered, a certificate indicating accomplishment is awarded graduates of the school. The course is not a duplicate of university summer work, but is supplementary thereto. Field observation and identification occupy 60 percent of the students' time. Graduates of this school are filling positions as nature guides in parks and summer camps throughout the country. Many of the naturalist positions in the National Park Service are held by graduates.

The Yosemite Junior Nature School.—The Yosemite Junior Nature School is planned for those children wishing to study the natural history of Yosemite National Park under the leadership of a ranger-naturalist. Many features of the trailside are brought to the attention of the keen young observers. There are usually several volunteer workers who assist the ranger-naturalist during the 6-week session. The work is divided into groups based on ages and grades. Classes meet at the museum and utilize its many facilities for study.

This is the one fully organized effort to afford special opportunities to children. Many parents spend the summer months in Yosemite purposely to give their children the advantages of this nature school.

Research.—An educational program must be founded on reliable facts secured through scientific research. The park visitor cannot be instructed regarding a battlefield unless the guide knows and understands the historical facts surrounding the engagement. Facts useful in the work must be culled from literature, and much library work must be done by trained historical assistants before a dependable story can be told. Hence the need for the historical research staff located at the Library of Congress. In the field of biology there must be a staff of technically trained men to study the fauna and flora of the park areas, furnish the facts needed for proper wildlife administration, and develop a wildlife policy.

A start only has been made on a research staff sufficient to improve accuracy of statement and safety of method employed. Meanwhile dependence has been placed on utilization of experts from other Government bureaus. Sanitation problems are supervised by a man assigned by the Public Health Service; insect problems, by men detailed by the Bureau of Entomology, and archeological problems, by the staff of the National Museum. Universities and scientific institutions are encouraged to undertake special research problems helpful to the National Parks Service. In this way there is secured a continuous flow of new and dependable information on the chief phenomena within the parks.

In general, the research program relates itself primarily to the securing of essential facts relating to needs of wildlife, explanation of features, comfort of visitors, and proper administration.

Conclusions.—Within the superlative areas comprising national parks and national monuments, opportunity is afforded to meet the realities of our natural surroundings and to study the inexorable underlying laws. In the historical areas important and stirring aspects of human achievement are presented which stir the highest mental concepts and patriotic emotions. Inspiration gained from visits to these areas brings enrichment to human lives. However, such inspiration is often dependent upon a maximum of understanding of significant phenomena.

Of the potential student body of 3-1/2 million represented by annual travel records, more than 2 million now use the educational program in some way.

The present park educational program is inadequately supported financially, and is undermanned everywhere. Added financial support to permit increased personnel looking toward adequate meeting of demand and additional working tools is the greatest need at present. With increased travel and use of educational facilities must come an expanded program.

Education in State and Municipal Parks

Similar educational programs are being developed in State and municipal parks. Those States which have most actively espoused the program are New York, West Virginia, Indiana, and California. The Cleveland Metropolitan Park System has employed a naturalist and has provided marked nature trails.

It is in State and municipal parks that there is greatest need for educational programs. Too often these parks provide open spaces but little assistance in scientific interpretation of features. Travel is very heavy and visitors seek profitable utilization of their time. Modification of programs to meet the shorter stay and the more local-minded visitor is relatively easy, if emphasis is placed on self-finding trails arid museums, as has been done in Bear Mountain Park in New York State. There is a slight tendency to develop playground facilities and commercial type of amusements which well may be justified, but this need not interfere seriously with an educational program designed to care for a type of recreation more mental than physical.

The proposed expert service by the Government would provide opportunity to stimulate the expansion of educational programs in State and metropolitan parks. Of course, the best stimulus will come from demand of the public, following successful operation in those parks which undertake an educational program.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

recreational-use/sec5.htm

Last Updated: 20-May-2016