|

Raising the Roof of the Rockies

A Geologic History of the Mountains and of the Ice Age in Rocky Mountain National Park |

PREFACE

Driving over Trail Ridge I Stopped at Forest Canyon Overlook. It was early in the day, but a few hardy souls were at the rim, their jackets buttoned and their collars turned up against the freshness of a summer morning at 11,600 feet.

"Isn't that something now!" said a young woman with her husband and two children.

"It sure is a long way down," replied the man.

"Dad! Let's go out there!" The boy started for the brink.

"Neil! Don't!" shrieked the mother and firmly grasped his arm.

They stood for a moment gazing across at the uplands of Sprague Mountain, Terra Tomah, and Mount Ida towering above the rocky canyons of Hayden Gorge and Gorge Lakes.

Casually, the girl asked, "Mom, why are the mountains so steep and then so flat on top?"

"I don't know," her mother replied, "but they look like they've been there a long, long time.

"Maybe they've had a hard life," the husband laughed. "Let's go." He snapped a picture and they were off.

|

| View from Forest Canyon Overlook. The rolling rooftops of Terra Tomah (left) and Mount Ida (right) cut by the glaciated canyon of Gorge Lakes. (Fig. 1) (Dwight L. Hamilton) |

Two thousand feet below, the spires of a vast spruce forest ruffled the dark green floor of Forest Canyon. To the west, small blue and green lakes glittered in deep basins surrounded by high gray cliffs. Snowbanks peered from the shelter of shadows. Above the cliffs, in striking contrast, a broad, gently sloping tundra upland, the roof of the Rockies, stretched away to north and south along the Continental Divide.

The girl's question kept coming back. "Why are the mountains so steep and then so flat on top?" More questions followed. When was the flat upland formed on the mountains? Or was it perhaps formed first, and then uplifted as the mountains formed? When and how did the mountains form? The rocks must have formed first, but how much younger are the mountains? When were the canyons cut? They should be younger than the upland, which is clearly cut by their deep basin-like heads. But are they? Obviously the canyons are glaciated, for you can see ice-scoured ledges and knobs in them. But did the glaciers cut the valleys or flow down valleys that were already cut?

This geologic history of the mountains in the Park attempts to answer these and other questions. It is based on current knowledge, but future research may well prove some things wrong. That is the way science advances. The successive events are related in terms of their age, for methods are now available by which the age of certain kinds of rocks can be measured in years. Thus it is possible to say that this happened about 65 million years ago or that happened about 100 thousand years ago.

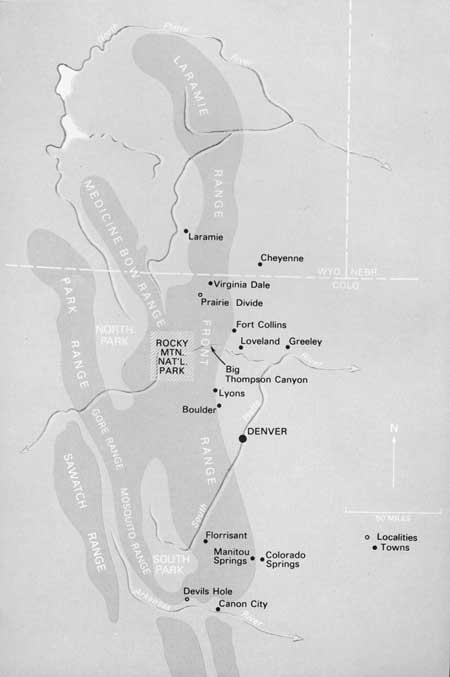

The first part of the story explores the almost incredible series of events that has brought about the present mountains. Truly, they have had a long hard life—indeed, many lives. Today, with minor exceptions, only the oldest and youngest rocks on which this history is based are preserved in the Park. To fill the gap, the intermediate history is borrowed from nearby mountains and plains (see index map), where rocks of the missing ages are preserved. You may feel skeptical, and perhaps a bit confused, as events lasting millions of years flash by in a few pages, But if the mountains seem to alternately rise and wear away faster than you can follow, pause and glance up at those in the Park. They'll still be there—and will be for millenia to come.

The second part of the story traces the events of the Ice Age—the last 2 million years—during which large glaciers advanced and receded in the canyons. Most of the landscape of the Park either is the product of sculpture and scour by these glaciers or is formed of their deposits. In fact, the shape of most features is the work of the last large glaciers which occupied the canyons from about 25,000 to about 13,000 years ago. More specific features of the landscape are mentioned and illustrated in this latter part of the story than in the earlier part, because they have survived and you can see them.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

richmond/preface.htm

Last Updated: 8-May-2007