|

Raising the Roof of the Rockies

A Geologic History of the Mountains and of the Ice Age in Rocky Mountain National Park |

Specimen Mountain And The Lulu Mountain Volcano

North of the Park, Lulu Mountain is the remains of a somewhat younger volcano which broke out about 28 million years ago in association with steep fracturing of the earth's crust along the west side of the Front Range. Specimen Mountain has long been considered to be the remains of a similar volcano. It is formed of layers of volcanic ashflow rock, obsidian, mudflows, volcanic debris fallen from the air, and lava flows of a kind known as rhyolite. These different kinds of rocks can readily be seen along the trail up Specimen Mountain.

Recently, however, R. B. Taylor has discovered that the volcanic ashflow rock and underlying obsidian which cap Specimen Mountain and adjacent summits actually are deposits of a volcanic ashflow, which erupted as a dense cloud from another volcano or caldera, possibly to the northwest, and spread rapidly across the area of Specimen Mountain, where it collapsed, and welded into rock while still hot. The phenomena is somewhat analogous to the ash eruption of Mount Vesuvius that destroyed Pompeii. Moreover, the fact that the ashflow deposit caps Specimen Mountain and adjacent summits shows that Specimen Mountain could not have been an active volcano at the time of the ashflow eruption 28 million years ago.

|

| Volcanic rocks in cliff south of Specimen Mountain. Upper part is volcanic ashflow with black Obsidian layer at base. Middle part is gray tuff and rhyolite lava flows. At bottom, almost out of sight, are stony mudflow deposits and fragmental volcanic debris that fell from the air. The basin beneath the cliff is not "the crater" of a volcano, as it has been mistakenly named. (Fig. 9) (Roger J. Contor) |

However, volcanoes existed at Lulu Mountain and probably elsewhere. A granite-like rock, formed from molten magma that congealed at depth in the source chamber which fed the volcanoes, is exposed in the area of Michigan Lakes and along the ridge from Mount Richthofen to a point south of Lead Mountain. The volcanoes probably formed large cones, above the surrounding terrain, and may have attained altitudes of 8,000 to 10,000 feet above sea level. The materials that erupted from them filled the deep canyons at Milner Pass and La Poudre Pass, and are spectacularly exposed in the Little Yellowstone headwaters of the Colorado River southeast of La Poudre Pass. To the west they overlapped the deeply eroded remains of lava flows from the 54-million-year-old volcano on Mount Richthofen. To the east they flowed out over a rugged terrain eroded in the ancient gneiss, schist, and granite. At Iceberg Lake on Trail Ridge, an ashflow, possibly the same as that on Specimen Mountain, filled a steep-walled valley at least 500 feet deep. The welded ashflow rock can be seen in the cliff above the lake; to the north and south the old walls of the valley filled by the ashflow rock are of gneiss.

|

| Volcanic debris fallen from the air, exposed along trail up Specimen Mountain. (Fig. 10) (National Park Service) |

|

| Volcanic ashflow cliff at Iceberg Lake. The ashflow fills a valley cut in the ancient gneiss which is exposed on upland to right and left. (Fig. 11) (Richard DeLong) |

Waist Deep in Volcanic Sand And Silt

About 26 million years ago, streams began again the never ending process of erosion, transport, and deposition. They carried large quantities of debris from the volcanoes and from other uplands in the Park down to the surrounding valleys and lowlands where they deposited it, along with volcanic ash blown in from active volcanoes to the west. Some of these deposits can be seen in the large roadcuts along the highway leading south from the Park, west of Grand Lake. There, they consist of layers of tan sand and silt eroded from nearby uplands, such as Specimen Mountain, together with some layers of white volcanic ash.

North of the Park, in southern Wyoming, the streams deposited such large quantities of these sediments that the lowlands were eventually filled. Low mountains such as the Laramie Range were buried again and higher mountains were more extensively covered than they had been by the volcanic ash 34 million years ago. In Colorado, the still higher Front Range, including the Park, was not covered but remained an area from which sediments were eroded.

|

| Layers of volcanic sand, silt, and ash along Colorado Highway 34, south of Grand Lake Junction. (Fig. 12) (Wayne B Alcorn) |

This was a time when mammals developed rapidly. Small pony-sized horses, camels, pig-like oreodonts, and rhinoceroses thrived, and were eaten by carniverous beasts such as bear-like, fox-like, and wolf-like dogs. Cats were also predators; some had long stabbing teeth, and others were ancestral to your tomcat. Mountain forests were predominantly of pine with sparse spruce and fir, and a few broad-leafed trees such as elm and hickory. In the lowlands were brushy grassland parks and broad-leafed forests.

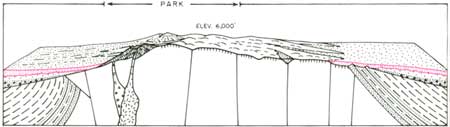

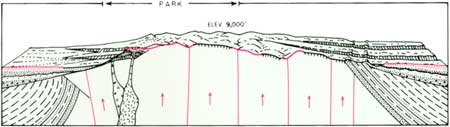

Uplifted, Exhumed, And Awash in Their Own Debris

At some time about 18 million years ago uplift began again to intermittently raise the mountains of northern Colorado and southern Wyoming. Streams stripped away most of the cover of volcanic sediments and ash which they had previously deposited. Many tended to find their former courses and to partly or wholly re-excavate their old valleys and canyons in the flanks of the mountains.

From the edge of the mountains, the streams fanned out across broad, gently sloping plains to surrounding lowlands. Beyond to east and north, major rivers eroded valleys 200 to 300 feet deep. To west and south, however, no valley erosion appears to have taken place.

As erosion of the mountains progressed, the streams at lower elevations began to fill again the valleys and canyons they had just excavated. At first their deposits contained many boulders and cobbles, which were carried far out from the mountains. Later, they became chiefly sand and silt mixed with volcanic ash. This filling continued until 5 to 7 million years ago, by which time the mountains north of the Park in Wyoming were almost completely buried. Streams flowed east from the Park Range across the crests of the Medicine Bow and Laramie Ranges to the highest surface of the High Plains. West of Cheyenne, stream deposits of this age, as well as the older volcanic sand and ash, still extend up onto the summit of the Laramie Range, and their gently sloping surface is utilized by both railroad and highway as the easiest route onto the mountains. Elsewhere, they still fill or partly fill many ancient valleys and canyons.

In northern Colorado, northwest of the Park, valleys were filled to within about 1,000 feet of the highest summit areas. In central Colorado, south of the Park, they were filled to a much less degree. East of the Park, it is difficult to determine just how far up onto the mountains the filling extended because so few of the deposits remain today and because this area has been uplifted here and downdropped there by subsequent faulting.

The climate during this time of canyon filling became increasingly dry, but was still more humid than today. Mountain forests were chiefly pine, with a few hardwoods such as elm and birch. Spruce, fir, and pine grew at higher elevations, sagebrush at lower elevations. Animal life in the lowlands included the first one-toed horses, pliohippus, as well as rodents, three-toed horses, mastodons, rhinoceroses, and many camels.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

richmond/sec5.htm

Last Updated: 8-May-2007