|

Salinas Pueblo Missions

"In the Midst of a Loneliness": The Architectural History of the Salinas Missions Historic Structures Report |

|

CHAPTER 9:

THE RETURN TO THE SALINAS MISSIONS

ABO: HOUSES AND SHEEP RANCHING

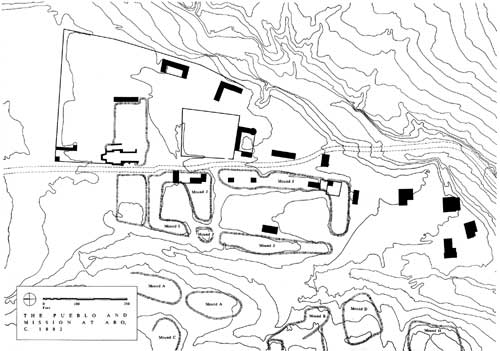

The reoccupation of Abó probably began as part of the resurgence of interest in the lands east of the Manzano Mountains from 1800 to 1815. The presence of the almost complete church of San Gregorio de Abó, the low walls of the burned-out convento, and the great mass of the ruins of the pueblo beside permanent springs just off the old road through the pass attracted many overnight visitors. Soon a permanent resident population settled by the springs and began to build houses from the remains of the ruined buildings. [1]

The new settlers built several houses southwest of the mission church, including a rectangular enclosure about 135 feet wide and 160 feet long at the south edge of the campo santo, apparently to be used as a corral or pen for livestock. [2] At the same time they built an enclosing wall that ran 140 feet north from the north end of the church and enclosed an area about 330 feet east to west and 550 feet north to south. It originally stood to a height of well over four feet. The settlers built a square bastion-like room at the northeast corner of the enclosure. [3]

The houses consisted of a two-room structure and a five-room structure built adjacent to each other, probably with a continuous wall connecting the two buildings and enclosing a small patio or yard. The settlers may have rebuilt portions of the civil compound on the west side of the church, and perhaps the first convento rooms at the east end of mound I. The reoccupation does not appear to have been extensive, and seems to have been oriented more toward sheepherding and catering to travellers than toward developing a permanent, easily-defended compound.

The settlers later built a plazuela, a small fortified building with a torreon at the southeast corner, on the south side of the corral. By comparison with similar torreon complexes at Manzano and Quarai, the Abó torreon can be roughly dated between 1820 and 1830, when Apache raiding reached its height.

Abó appears to have been abandoned again about 1830. The settlers probably left because of the increased Apache raids during this time and the failure of the Manzano settlers to have the small Abó settlement included in the boundaries of the town grant. The church probably burned out about the same time. For the next thirty-five years the ruins apparently served only as an overnight camp for hunters and for travellers on their way through the pass to Manzano.

Abandonment and Visitors

Lieutenant James W. Abert visited the ruins in 1846. His careful watercolor of the church recorded a number of important details of the structure before major collapses had occurred. At that time Abó looked much like Quarai does today. Abert's measurements of the church closely match the actual size of the building. He briefly described the large window in the east side-chapel, but did not mention any other windows or doorways. [4]

J. W. Chatham visited Abó in July of 1849, and found no trace of anyone living in the area. He briefly described the extent of the church and convento, and of the enclosing wall built by the settlers in the period between 1815 and 1830. [5]

William W. Hunter, a forty-niner on his way to California, passed through about the same time, and also did not note any residents in the area. He described the crenelated wall tops and mentioned two windows in the church. Hunter noticed the charred ends of burned "rafters, joists, and beams" still set in the masonry. [6]

Major James H. Carleton visited Abó on his way to Las Humanas, in 1853. His detailed description of the church again recorded information of great importance to a history of the buildings. From his description, it appears that the apse still stood as of that year, as well as much of the front, or south, wall. Carleton also mentioned the crenelated wall tops and the charred beams still in place in the walls. He was able to find one beam set into the east wall of the church, about six feet above the ground, which retained a finished surface. This may have been one of the beams of the sacristy. Carleton also observed the remains of a protective wall enclosing the church and convento area, but considered it to have also surrounding the pueblo. He estimated that the enclosure was about 940 feet north to south and 450 feet east to west. [7]

The apse fell sometime after Carleton's visit but before Bandelier drew and photographed the ruins in 1882. Archeology in 1938 found that the area of the main altar had been destroyed by treasure hunters, as happened at Quarai and San Isidro. Apparently the looters undermined and cut through the back wall of the apse in the process of digging for phantom treasures. This caused the apse to cave in, taking the end walls of the sanctuary with it. [8]

In the mid-1850s Luciano Pino, accompanying a group of buffalo hunters from the Casa Colorado grant, stopped at the ruins and springs. Pino was impressed with the area and decided to attempt to resettle the ruins. In 1859 he and a group of prospective settlers, including Juan José Sisneros, revisited the area to plan such a resettlement. They were attacked by Apaches and Pino was killed. The survivors decided that the area was still too dangerous and gave up on the attempt at resettlement. [9]

Second Reoccupation

By 1865, the Manzano area had become more peaceful. Juan José Sisneros remembered the good qualities of the Abó valley. By 1869, he had moved his family to the ruins of Abó and had begun building houses and protective walls. [10] They apparently reoccupied and reconstructed the older buildings left by the settlers of 1800 to 1830, and then added to the complex. As each of the children came of age, they built another house within the protective walls of the little settlement. Eventually, with marriages and friends moving into the area, a small village grew up around the burned-out church. By the 1870s the new arrivals had built at least eight houses along the west and south sides of the pueblo ruins.

Several of these houses were plazuelas in their own right. For example, the house where Ramon Sisneros lived in 1882 was part of a U-shaped structure with six rooms. The mouth of the "U" opened toward the west, and was closed by a single wall to form a patio within the building. The main entrance was through a large gateway in the single room forming the south arm of the "U." Other buildings followed variations of the same pattern. [11]

Photographs of the Ruins

By 1882 Juan José was dead, and his son Ramon was the head of the Sisneros family. His house stood on the east side of the compound near the northeast corner. At the same time, Marcos Luna lived in a house built on the east edge of the convento ruins. Adolph Bandelier stayed in Ramon's house when he visited Abó during Christmas of 1882 and drew a plan of the entire pueblo, mission compound, and most of the settlement. [12]

Bandelier succeeded in taking only one photograph of the ruins of San Gregorio. The picture is almost useless, because the intense cold affected the chemicals of the plate and prevented a clear image. Only vague details can be made out in the print. Enough can be seen, however, to identify the southeast buttress of the church facade still standing to the height of the walls of the nave. There is no clear indication of a tower extending above the wall line, adding support to the appearance of the church as recorded by James Abert in 1846. [13]

Charles Lummis visited the ruins in 1890 and took four photographs. He had better luck with the weather, and two of the four pictures are sharp, clear records of structural details. The other two are slightly out of focus but still of great importance. These pictures preserve evidence of the interior structure of the church that could never have been deduced from the plan of the building, and permit the detailed reconstruction of the roof, balconies, and catwalk described in this report. [14]

Figure 24. Abó as painted by Abert in 1846. The painting documents a number of critical details about the church and its surroundings. No traces of the front porch are visible, and the lintels of the front entrance and choir loft window are both gone, probably destroyed in the fire that gutted the building in perhaps 1830. The deep notch on the east (right) side marks the location of the window at the mid-point of the nave, while the choir loft doorway does not seem to be visible at all. The second-story doorway that once opened from the roof of the sacristy into the east side-chapel has fallen out above the location of the lintel, but the collapse has not penetrated all the way up to the parapet. On the west (left) side of the nave, the high point marks the location of the buttress outside the wall, while the drop-off to its left probably indicates the location of the notch where the masonry has fallen above the sacristy doorway. Beam sockets can be identified on the north wall of the church. In the original watercolor, differences in shading indicate that Abert could see five sockets in the north wall of the sanctuary, and the first two sockets of the beams over the apse. These two sets of sockets are at about the same height, indicating that the ceiling of the apse was almost as high as the ceiling of the sanctuary. To the right of the church, the walls of the sacristy still stand to about their full height. The ruined wall in the foreground and a poorly-defined wall extending across the background to the right of the sacristy, below the trees, all appear to be ruins of the ca. 1810 to ca. 1830 reoccupation of the area. The interior of the church still clearly shows extensive traces of the white plaster that once covered it. |

Figure 25. Abó in 1882 as photographed by Bandelier. This picture was taken from almost the same angle as Abert painted his watercolor 36 years before. Since Abert's watercolor, large sections of the walls of the church have fallen. The southwest tower and the south end of the west wall of the nave have fallen, as well as the east wall of the nave from the southeast tower to the east side chapel. The southeast tower itself still stands. At the north end of the church, the entire apse wall of the building has fallen. The crenelations along the tops of the walls can easily be seen. Biblioteca Apostólica Vaticana, Archivo Fotographico, # 482-47, courtesy Charles Lang. |

In 1892, Ramon applied to the United States government for title to the quarter-section in which the ruins of Abó were located. After demonstrating the validity of his claim to the land, he was granted title. [15]

Ramon died about 1900, and his brother (or son) Joaquin became the head of family. [16] Joaquin contracted an agreement to sell water to the Eastern Railway of New Mexico at the Scholle watering point about 1909. [17] In the period from 1880 to about 1910 branches of the Sisneros family, and perhaps some other settlers, built a number of new houses among the ruins of the pueblo. These houses were largely empty and falling to ruin by 1920. [18]

In 1912, the Sisneros family lost title to the portion of the quarter-section containing Abó and in 1915, Ubaldo Sanchez and his wife Beatriz acquired title by tax redemption. They sold the quarter-section to Joe J. Brazil in 1919. Brazil then sold a half interest in the land back to Joaquin Sisneros. The remaining half-interest was sold to Abundio Peralta. [19]

Joaquin died in 1926, and the family divided his estate in 1928. In 1934, Federico Sisneros bought all the family-owned interest in the site of the pueblo and church from the remaining heirs, and all interest in the tract along the north side of the church and convento. [20]

During the years from 1900 to 1930 photographers recorded the collapse of the walls of the church of San Gregorio. These photographs show that the side walls of the sanctuary and north walls of the side chapels fell by about 1900. The west side chapel wall collapsed before 1910, while the east side chapel wall split down the center of the east balcony doorway. The multiple buttresses of the bell tower kept the south wall of the west side chapel standing (until the top five feet of it were intentionally removed in 1972), but the top of the south wall of the east side chapel fell in about 1910, leaving only a small section of the east wall of the side chapel, along the south side of the balcony doorway, still standing. [21]

Figure 26. Abó as seen by Charles Lummis in 1890. This picture was made from almost the same angle as the Bandelier photograph 8 years earlier. In the interval the southeast tower had finally collapsed, but few other changes can be seen. In the foreground, walls and structures constructed during the second reoccupation after 1860 are visible. Bandelier's photograph was taken somewhat closer to the church, so that these walls and structures were behind him, out of the picture. Courtesy Southwest Museum, # 24832. |

Figure 27. A second view of Abó in 1890. This picture is looking towards the southwest, and the north or sanctuary end of the church is in the foreground. In both this and the previous picture, the crenelations at the top of the building can be seen clearly. These two Lummis photographs are critical to the analysis of the structure of Abó, because only they record several items of important information. The wall at the right in this picture is the west wall of the sanctuary (or transept in the case of Abó, with its peculiar arrangement of space. At the top of the wall, below the crenelations, can be seen two horizontal bands in the stonework. The upper of these is the scar left by the roofing above the roof vigas themselves, which in this area ran lenghtwise down the church, or parallel with this wall. The lower horizontal band marks the sockets of the bond beams creating the box-like structure around the wall tops of the high walls of Abó. The bare wall between the two bands was covered by the westernmost of the roof vigas in this area. The vertical, irregular scar down the face of the wall was produced by a failed roof canal. Instead of draining roof water through the wall, the canal became blocked, the water pooled, the roof seal failed, and water began running down the inner face of the wall, cutting this channel. This indicates that the roof sloped down towards this wall. In this and the previous photograph, three sockets can be seen in the irregular scarring left by the leak. They line up with three sockets a few feet to the south at the corner of the side chapel. The six sockets together are the last traces of the central support for the high roof of the church as well as the catwalk from balcony to balcony. The sockets for the floor of the west balcony are visible below and to the left. On the left, or east, side of the church, the second window into the sanctuary can be seen above the remnants of the sacristy doorway. To the left of the sanctuary window is the large doorway that once opened from the sacristy roof onto the east balcony inside the church. The beam sockets and bond beam sockets for the sacristy roof are visible below this door and the sanctuary window. Courtesy Southwest Museum, # 24831. |

Figure 28. Abó from the northwest in 1916, by Jesse L. Nusbaum. The walls of the sanctuary and side chapels have fallen, except for the buttressed area of the bell tower, and the tower buttress on the east side. The southernmost bottom corner of the balcony doorway is visible just to the right of the figure sitting on the sill of the doorway on the wall. Below the doorway can be seen the irregular traces of the sockets for the eastern balcony. On the shadowed north face of the east tower buttress, the dark patches of the socket for the viga that supported the balcony can be seen, with the sockets of the balcony railing above it. The large depression in the wall above the railing sockets is the socket for the east end of the lower clerestory vigas and corbels; the hole through the wall at this point marks the end of the vigas themselves where they penetrated to within inches of the outer surface of the wall. Several feet above this is the smaller indentation of the upper clerestory viga socket, and in the irregular wall surface above this and below the crenelations are the sockets of the vigas and corbels for the high roof above the clerestory. A similar series of sockets can be seen in the bell tower section of the west wall, closer to the camera. Courtesy Museum of New Mexico, # 12876. |

Figure 29. Abó in about 1916. This is a closeup of the southeast corner of the east side chapel and the east face of the west wall of the nave, taken by an unknown photographer. Fine details such as the second level of inset of the crenelations and the imprints of both bond beams on the west wall can be seen. The scar of the east wall of the nave is visible on the east buttress tower, and the corbel sockets, viga sockets, and the scar of the small section of wall that had been at the edge of the doorway from the sacristy to the corridor can all be seen in this view. To the left of the rectangular sockets of the sacristy roof, the smaller round sockets of two corridor roof-beams are visible, and next to them on the south face of the tower, the irregular horizontal shadow line in the stonework marks the upper surface of the roof of room 18. Courtesy Museum of New Mexico, # 58308. |

By the time preservationists began to actively consider the possibility of excavating and stabilizing the church, most of it had fallen. Only an impressive section of the west nave wall and the bell tower stood to the height of the original wall top. This small piece of the original building, however, was enough to indicate the size and impressiveness of the whole.

QUARAI: HACIENDAS AND FARMING

Settlers reoccupied Quarai in the first years of the nineteenth century. Abó, with substantial ruins beside the main route through Abó Pass and with a dependable spring, was the first community to be established west of the Manzano Mountains since 1680. The Quarai settlement formed the second, predating the establishment of Manzano itself. [22]

Quarai in 1800

When the settlers arrived at Quarai, they found that the roofs of the old mission church and convento survived relatively intact after 125 years of abandonment. The buildings were, however, well along the path of decay followed by all abandoned buildings. Falling leaves, bird's nests, and other debris had blocked canales, causing rain and snow melt to puddle and soak through the plaster and adobe layers of the roofs. Under some damp areas latillas and vigas had begun to rot. In places, a viga had rotted sufficiently to break under the weight of a heavy rain or snow, and the roof had fallen in along that viga line. The collapse had twisted the viga ends in the wall, causing shifts and cracks in the stonework. Rain and snow melt rapidly washed the clay from the roof in the area of the break, exposing more wood to weathering. This, too, was rotting and beginning to sag. The lintels over windows and doors were slowly giving way, and the walls cracked and exposed by the collapsing roof beams were beginning to crumble. Had the process of decay continued naturally, the abandoned church and convento would have eventually been reduced to rubble indistinguishable from the ruins of the pueblo. The arrival of the settlers altered the process considerably.

Figure 31. Changes to the convento of Quarai after the reoccupation during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. 1. About 1820, the first rooms added at the southeast corner of the convento had been completed. 2. About 1830, the church was burned out. This plan probably represents the structures in use when Abert, Chatham, Hunter, and Carleton visited the ruins. 3. In 1880 the rooms at the southeast corner of the convento reached their greatest extent, and the convento rooms continued to collapse. 4. By 1910 no roofing survived, and about this time treasure hunters excavated the fill from the interior of the sacristy, room 4. |

The Church

The well-designed and built church roof survived in fair condition over the nave and most of the transept. Much of the adobe sealing layer of the roof had washed away, so that light showed through the roofing in many places. One or two beams had probably cracked and fallen in the nave. The worst damage was in the transept, where the main support beam across the mouth of the apse had apparently rotted and broken before 1759. This caused the beams of the central area of the transept roof in front of the sanctuary to fall in, dumping rubble in the transept and apse. Such a collapse would have opened a hole seventeen feet wide and twenty-five feet long in the transept roof. [23]

The church showed many other signs of its age. Virtually all the exterior adobe had washed off. Most of the decorative wall plaster on the interior had flaked off, revealing patches of bare adobe plaster and stone. A layer of dirt over a foot thick covered the flagstone floor, washed down from the roof through cracks and gaps, blown in through the doors and windows, or washed from the walls. The side altars were still recognizable. In the apse, the rubble from the fallen transept roof had been dug out, and a large pit excavated through the main altar and altar platform. The dirt from the excavation, the rubble of the altar, and the debris from the collapsed roof combined to form a low, wide mound in the transept and apse. The retablos, decorative woodwork and paintings were gone, taken by the priests or for mementos or firewood by occasional travellers.

The Convento

As a result of decay, only the sacristy (rooms 4 and 7) and the residence hall block (hall 10 and rooms 11-20) were still covered with roofs. [24] The rest of the convento was a tangle of ragged walls and rubble-filled spaces. The roofs of the rooms most exposed to weather had rotted quickly and collapsed. These included the portería, ambulatorio, storeroom (room 8), and refectory (room 9) on the ground floor and most of the second story rooms.

After the loss of the roofs, the walls of the entire central area of the convento had begun to crumble into the rooms. Clay from the roof and stones from the wall tops, along with dirt and sand blown in by the wind, had covered the floors. When the settlers arrived, a fill of about three feet of rubble and wind-blown dirt had built up, and the walls had been reduced by about 1 1/2 feet. Since the walls in this area averaged about eleven feet high originally, only about six feet of wall stood above the rubble in 1800. [25]

The surviving rooms were in fair condition. Both the first and second story of room 6 survived. The sacristy rooms (4 and 7) retained their original square-beamed and corbelled roof in good condition, but the roofing of the mirador over the north half of the sacristy (room 7) had fallen. The residence hallway and most of the cells along its east side retained solid roofs, even though most of the plaster had fallen off the walls, forming a layer of fallen plaster and blow-in dirt six or eight inches thick on the floors.

In spite of the obvious structural problems, to the settlers looking for a place to homestead, the ruins of the convento of Quarai were houses waiting for them to move in. The fields of the well-watered valley could still be recognized, even though they were badly overrun by 130 years growth of weeds and brush. This looked like the perfect place for a new ranch and farm for the land-hungry wanderers from the crowded Rio Grande valley.

The Settlers of Quarai

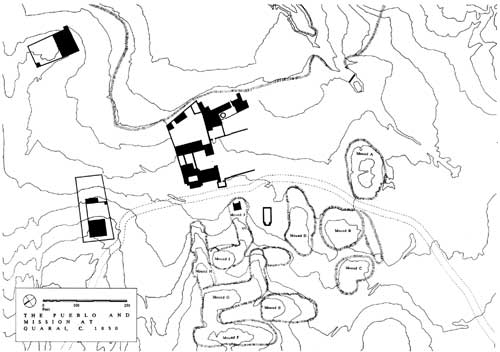

Miguel Lucero and his family were probably the founders of the new Quarai settlement. Two of the dominant men in the effort to resettle the Manzano area were Miguel and Juan Lucero. Miguel arrived on the east side of the Manzanos before 1823 with Domingo Lucero, perhaps his son. Juan came soon after 1823 with Santiago, who may have been his son. Both branches of the family were probably living at Quarai before 1830. [26]

Miguel set up housekeeping in the intact rooms of the convento of Concepción de Quarai. He chose the residence hallway and the rooms on its east side for the family house during the first few years. He repaired the roofs, cleaned out the debris of more than a century, built a fireplace in room 15, and moved in. The sacristy rooms and the adjoining two-story section became additional housing, perhaps for Santiago's family.

The Luceros converted the standing walls of the ruined portions of the convento to sheep and goat pens to protect the livestock, the potential wealth of the family. In room 7 they repaired the roof and added wall plaster and a new floor on top of three feet of debris. In the northeast corner of room 6 they built a fireplace. [27]

In the first few years the family prospered and the herds grew. Soon more space was needed for pens, corrals, stables, and houses for client workers attracted to the rapidly growing ranch. New buildings went up around the old granary, extending south from the second courtyard into the corral and garden area of the convento. Some of the new buildings were stables and pens, while others were small houses for the new workers. The Luceros added most of the rooms on the west side of the old granary building, against its wall. Miguel built two other houses from the ruins of the stable and barn buildings against the east wall of the second courtyard.

The Luceros built an irrigation system and terraces along the valley using the rubble of the fallen pueblo buildings. The terraces consisted of retaining walls of uncoursed rubble along the north, west, and south sides of the valley. [28] They built stock pens and fences, sheds, coops, stables, gardens, and small houses for the people who came to work for them on the rich land of the Quarai valley. They cleared out the church, perhaps even roughly patching the roof, and used it as a place to bury their dead and for occasional religious services when an itinerant priest visited the area.

The irrigation system was simple. The dam was about six feet thick, made of two rows of upright posts with rock and clay fill between. It formed a pond on Zapato Creek along the south side of the pueblo. The pond formed by the dam overflowed at the south end of the dam against a series of huge boulders and sandstone ledges forming the hillside here. From the north edge of the pond the Luceros excavated a ditch across the old mission garden and along the top of the north and south terraces, carrying water to the fields behind the terraces, plowed for the first time in more than a century. The north ditch continued down the valley. Eventually it crossed the future site of Punta de Agua a mile away and emptied into the vast basin of ancient Lake Estancia, now almost dry.

Mound J House began as a small two-room house. The Luceros built it on the top of the east end of mound J, southwest of the church. It measured twenty-five feet square, with walls three feet thick and about ten feet high. It had a flat roof, a doorway opening onto a porch-like terrace on the east side, and a window on the south wall. [29]

As the fields began to produce and the sheep increased in number, the Luceros prospered. Client farmers, or peons, began to move into the valley. The Luceros gave each peon permission to live on and use small tracts of land in return for a portion of the produce of his herds and fields each year. [30] The Luceros, as patron, would protect the peons from the Indians in return for a certain amount of labor in the Lucero fields and herds. About 1820, Miguel decided the time had come to build a plazuela, a fortified home and ranch headquarters building, for their holdings.

Miguel selected a knoll just above the north terrace of the new fields and five hundred feet northeast of the church as the site for his new rancho. Construction proceeded quickly with all the peons lending a hand. Soon the fortified complex, now called the "Lucero House," was completed. It had a central block of rooms feet wide and seventy-five feet long, with stone walls two feet thick and fifteen feet high and a flat roof. Three rooms along the north side and several on the south all opened into a central patio area. The westernmost room on the north enclosed a large gateway opening into the central patio. A second gateway opened through the center of the south wall, with a small window on either side. A wall seven feet high and two feet thick formed a compound on the north side of the main block. The compound measured eighty-five feet north to south and seventy-feet east to west, with a square torreon on the northwest corner. Around the entire complex Miguel built a protective wall enclosing an area two hundred feet on a side. [31]

After the completion of the plazuela, the Luceros moved out of the convento rooms where they had been living. Lucero's mayordomo, or foreman, and his family probably moved into the convento.

A second major branch of the family, perhaps headed by Juan Lucero, arrived about 1825. This group immediately constructed a second plazuela, called the "North House" in this report, on the hillside about three hundred feet north of the old church, looking down the valley. The plazuela was much like Miguel's. Several rooms built of stone walls about two feet thick and fifteen feet high formed a central block fifty feet square. Around this Juan constructed a wall making a rectangular enclosure 115 feet east to west by seventy feet north to south. A square bastion stood in the southeast corner, and two other rooms projected from the northeast corner. Few windows or doors opened through the main enclosing wall. Around the main enclosure Juan built a secondary wall about 1 1/2 feet thick, two hundred feet east to west and probably two hundred feet north to south. [32]

The Destruction of 1830

During the 1820s Apache raids on the Manzano settlements increased. Captain Bartólome Baca's ranch north of Manzano, called "El Torreon," had to be abandoned, as was Valverde, Pedro Armendaris's ranch about twenty miles south of Socorro on the Rio Grande. Abó was deserted in the same period. As part of the widespread raiding, Quarai was attacked in late 1829 or early 1830. [33]

The raiders effectively destroyed the Lucero rancho. They killed several people, badly damaged the North and Lucero Houses, and burned the church, Mound J House, several of the buildings in the southeast area next to the old granary, and perhaps some of the convento buildings. [34]

The fire severely damaged the church. The clerestory, east nave, and east transept windows acted as chimneys. Air was pulled in through the main door and choir loft facade window; superheated air and flame jetted out of the higher openings. The intense heat burned out the lintels above the doors and windows, including the sealed west window. It damaged the stonework above these openings and on the inner faces of the buttress towers, making the stone softer and much more susceptible to water damage.

As the vigas of the roof burned through, the great weight of the roofing forced the viga ends to pivot in their wall sockets, levering the wall above each socket upward and inward, dumping large chunks of roof parapet into the interior along with the charred vigas, latillas, matting, and remaining adobe layer above. The parapets broke away in almost continuous strips in the areas where long stretches of vigas were set close to the top of the parapet, as in the nave. In the transepts and sanctuary the buttress towers stood above the vigas. Here the beams, unable to move the greater mass of stone, caused much less damage as they fell. Over the mouth of the apse, already damaged by the breaking of the apse mouth beam in the eighteenth century, much more collapse of the masonry occurred.

The heat damage and loss of lintels hastened the rate of collapse of the walls above the windows and doors. The unsupported stone began to fall out, causing the openings to grow upwards and outward from their top edges. Soon the entire wall above the higher openings, undermined by this decay, began to fall in. Over the next sixteen years, tall V-shaped gaps formed in the walls, marking the locations where doors and windows had been. The gaps above the choir loft entrance door and the east nave window left the east nave wall unsupported. Within a century it would fall into the nave.

The destructive raid broke the Lucero family. The damage to the fields, flocks, and buildings and the wholesale abandonment of the area by the peons left them effectively penniless. Most of the family left over the next year, moving to Manzano or back to the Rio Grande valley. [35]

The Manzano Church at Quarai

Meanwhile, the Manzano Community Grant had been approved and the town of Manzano had been officially created. In late 1829, the citizens of Manzano decided to build their new community church next to the decaying mission church at Quarai. The partly ruined church of Quarai had been the only real church in the area for as long as the settlements had existed. This and the influence of the Lucero family at Quarai, even though it was fading, were strong factors in their decision to select Quarai as the site for the Manzano chapel. The selection was apparently an attempt to replace the old church, an important part of the life of the new settlement.

Construction began on the chapel in the plaza about 150 feet southwest of Concepción de Quarai. [36] Public protest against the Quarai location of the chapel must have begun at the same time. Opposition grew rapidly, until on July 10, 1830, the Alcalde of Tomé gave permission to stop work at Quarai and build the chapel at Manzano. [37] The burning of the old mission church probably occurred during the construction of the new church, and may have influenced the decision to stop work at Quarai.

The few months of work on the chapel accomplished very little. The masons had marked the church outline onto the selected spot and excavated foundation trenches about four inches deep and thirty inches wide. They had begun construction on the walls and had poured an adobe floor onto the sloping ground surface. The walls had reached no more than a few feet in height when work was stopped, and the masons packed up their tools and left. [38] Later the foundations were apparently used for some other purpose; a juniper post one foot in diameter and perhaps nine feet long was set two feet into the ground in the approximate center of the walls. The purpose of this post is unknown. [39]

The leading members of the Lucero family apparently left Quarai ca. 1830, probably as a result of the Apache raids. They left José Lucero, probably a younger brother or cousin, in charge of the Quarai valley holdings. José and his family apparently lived in the convento buildings. The Lucero House and the North House, damaged by the raiders, were left uninhabited.

Lieutenant James W. Abert, travelling the main road through Quarai in November, 1846, met José Lucero and visited his house. Abert described the house as "an old ruin fitted up with such modern addition as was necessary to render it habitable." His watercolor of the church and convento is the earliest known pictorial representation of Quarai. [40]

The painting supplies several important details about the buildings and gives an indication of their condition in 1846. The filled west nave window was barely visible. The wall above it, supported by the stone fill of the window and not as damaged by the fire as the wall above other windows that remained open, had not yet begun to collapse. The facade above the choir window and main entrance had already fallen. The thin layer of stone covering the nave roof beam sockets had weathered out, leaving the sockets visible like tall, narrow crenelations along the top of the nave wall. The parapet had broken off in a ragged line above the beam sockets. The heat-damaged tower tops were already irregular and partially fallen; they looked much as they did just prior to reconstruction in the 1930s. Little or no stone robbing had yet occurred on the lower walls of the church.

Part of the antecoro survived against the east tower. Abert's painting clearly shows the antecoro window. The bell room above, however, had already fallen. The painting depicts the portería as fallen, but the east end of the south wall and the east rooms of the convento standing, with the window at the south end of the residence hall visible. The southeast rooms are apparently out of the painting at the right side.

On the southwest, the walls of the baptistry stood to a height of about twelve feet in most places. Mound J House, burned out with the church in 1830, was roofless and above its doors and windows showed the same V-shaped decay pattern as the church. [41]

During the 1840s and 1850s the remaining Luceros made an attempt at reconstruction. They rebuilt a number of rooms in the southeast area beside the old granary, including several new corrals and sheds. They built a torreon just west of the granary, but separate from the other structures. [42]

J. W. Chatham visited Quarai in February, 1849, and noticed the Lucero family. In the ruins of the mission, he said, lived "some poor Spaniards principally pastores as they have some spindle farms the walls of the old building show some skill as the plastering in some places is yet remaining . . . ." [43]

Figure 32. Quarai as painted by James Abert on Wednesday, November 4, 1846. In the foreground is the ruin of Mound J House, with the notch of a collapsed window on the right, or south side. Immediately behind it is the baptistry of the church. Abert indicates that he could see the sockets for the roof vigas of the nave from the outside of the building, meaning that the stonework between the sockets still stood to the height of the tops of the beams in 1846. To the right of the facade of the church, the choir loft stairwell and belltower still stand to the height of the top of the second story window. Just to the right of the belltower rooms is the gap where the portería has fallen in, and then the facade of the convento with a window opening, probably into the east hall. The rooms added on the southeast by the Luceros are out of sight to the right. |

A few months later, in July, William W. Hunter passed through Quarai. He described the houses: "Attached to the church were other ruins, partly demolished which some of the villagers had metamorphosed into modern habitations on their own rude and uncouth plan. There were several acres of land into cultivation at this place, the crops on which looked well." [44]

Four years later, in December, 1853, Major James H. Carleton passed through Quarai. He mentioned no people at Quarai, but did describe in detail one of the rooms of the convento. "We found one room here," he says,

probably one of the cloisters attached to the church, which was in a good state of preservation. The beams that supported the roof were blackened by age. They were square and smooth, and supported under each end by shorter pieces of wood carved into regularly curved lines and scrolls, like similar supports which we had seen at the ends of beams in houses of the better class in Old Mexico. The earth upon the roof was sustained by small straight poles, well finished and laid in herring bone fashion upon these beams. In this room there is also a fire-place precisely like those found in the Mexican houses at the present day. [45]

The level of expertise shown in the construction of the roof is far above that to be expected in a small house rebuilt from the ruins of the convento of Quarai. It is very likely that Carleton visited the sacristy of Concepción de Quarai, with its original roof having survived the fire that destroyed the church.

Settlers began returning to Quarai just before the Civil War. Punta de Agua was established between 1850 and 1860, probably in the ruins of client farmer houses built in 1820 to 1830 and soon became the new center of development for the valley. After the war, in 1872, Miguel Lucero sold the pueblo and mission of Quarai to Bernabe Salas of Punta.

Salas repaired and reoccupied the Lucero House and made some repairs to the convento. He rebuilt the northern room of the sacristy and plastered it with adobe, including a new floor almost four feet above the original flagstone floor. The old refectory and original kitchen were just ruined walls, and the patio, ambulatorio, southwest storeroom, and portería were nothing but low mounds of rubble. The eastern rooms, having survived so much, continued as residences for a time. In the southeastern area next to the old granary, Salas converted several of the sheds into a large stable, and other rooms continued to be used as small houses. The occupation was, however, short-lived. By 1882 Bernabe had apparently moved back to Punta, abandoned the convento rooms altogether, and turned the Lucero House into a barn and stable.

Adolph Bandelier visited Quarai twice in a period of two weeks in the winter of 1882-83 and was shown around the area by Bernabe Salas. Bandelier remarked that there were two or three new "ranchos," or houses, around the mission church, and "a large rancho of stone, now abandoned, on the south side of the pueblo." This may have been the building on the Romero family picnic area about 860 feet south of the mission church, built about this time, or it could be an undiscovered building somewhere between the Romero house and the south side of the pueblo mounds. More likely, though, Bandelier was describing the North House and got his directions reversed in his notes.

Bandelier found rooms of the convento still roofed: "We examined also the ruins of the convent . . . Several rooms, on the east side, are still entire, with white plaster on the wall, wooden lintels and ceilings." [46]

When Bandelier wrote up his notes in 1892 as his Final Report of Investigations Among the Indians of the Southwestern United States, Carried On Mainly in the Years from 1880 to 1885, his appraisal of Quarai was somewhat different. "The convent," he says, "is reduced to indistinct foundation lines measuring 15 by 17 m. (49 by 58 feet)." He had decided that the standing, roofed rooms along the east side of the convento patio were not original convento buildings, and that the southern half of the convento, so completely ruined by time and the use of the area as animal pens, was the cemetery for the church. [47]

The new residents of Punta de Agua began removing stone for building material from the buildings surrounding the church in the 1850s. By Bandelier's visit in 1882 they had removed the baptistry and Mound J House but had not yet done much damage to the church.

Seven years after Bandelier's visit to Quarai, Charles Lummis made three photographs of the ruins. His pictures illustrate most of the details seen by Bandelier. The second story of room 6 stood, but only one roof beam remained in place against the transept wall. The surviving cells on the east side of the convento had been unroofed at some time since 1882, but their outlines were recognizable. The Lucero House was in use and in good repair, visible in the background in one of Lummis's photographs. The North House, although obviously abandoned and beginning to decay, was standing in good condition. The palisado fence north of the church and the stone fence running south from the southwest corner of the church were standing, but in bad shape. Stonerobbing had removed most of the facing stone on the west side of the church. [48]

In spite of how solid it looked, Quarai was very close to final collapse. Within a few years settlers had removed the facing stone from the church facade, seriously weakening the thin front wall. Treasure hunters had chopped a large hole through the apse wall. The east transept wall began to sag outward, and a large crack formed on the north wall of the east transept where the sag pulled the walls apart. In 1908 the east wall, standing unsupported since 1830, finally toppled into the nave. About the same time treasure hunters excavated the south room of the sacristy. They left the hole open, exposing the walls to further weathering and probable collapse. Unless the church was given immediate, serious attention, it would soon follow Abó into ruin.

Figure 33. Quarai on December 28, 1882, as photographed by Bandelier. The edge of the window on the second story of the choir stairwell and belltower can be seen at the right edge of the facade of the church. Near its top corner, the stub of one of the lintel beams still survives. This beam has since been sawed off flush with the stonework, but is still in place. The wall beneath it originally extended to the left, or west, edge of the portería, but most of it had collapsed by the time of this photograph. The empty sockets of three vigas for the floor of the choir loft and front balcony are visible to the right of the collapsed entrance doorway. The sockets to the left of the doorway are not visible because the ends of the vigas are still in the sockets. At the left side of the church, the baptistry has fallen to a low mound, and a rubble stone wall extends across the mound to the corner of the church. Biblioteca Apostólica Vaticana, Archivo Fotographico, # 483-48, courtesy Charles Lang. |

Figure 34. Quarai as photographed by Charles Lummis in 1890. To the right of the church in the distance can be seen the Lucero House, with a covered wagon parked next to it. Below the Lucero house, the ruins of the walls of the south end of the east hall and of room 20 are visible. To the left of the Lucero House, the south wall of room 13 still stands to almost its full height, and three beam sockets can be made out along its top edge. These beams, running north to south, covered the hallway (room 14 from the east hall to the east courtyard. By reconstructing the lines of sight of this scene at Quarai today, it was possible to determine that the top of the wall of room 14 was about 13 feet above the present floor level. |

Figure 35. Quarai from the north in 1890. Lummis was the first photographer to record the details of this side of the church. At the right edge of the picture, the North House still stands to its full height. On the left corner of the church the walls of room 6 still stand to the top of the second story, and one roof viga remains in place against the north wall of the east transept. The notch of a window at the second floor level can be seen in the north wall of the room. At the top of the apse, the ventilation opening can clearly be seen, as well as the notch in the top of the wall where the canal that drained the apse roof had penetrated. The road to Abó from Punta de Agua curves around the church with a jacal fence along its east side. The road and fence were both recorded by Bandelier on his plan of the pueblo and mission made from the notes and sketches of his 1882 visit. Courtesy Southwest Museum, # 24828. |

Figure 36. The interior of the church of Quarai in 1890. This is the earliest detailed view of the interior wall surfaces of the church. A number of important details can be made out. In the north wall of the apse, the hole chopped through the wall by treasure hunters is easily visible. To the left and right of this hole on the apse wall are the sockets for the lower supports for the retablo. At the left and right corners at the mouth of the apse can be seen the sockets for the bannisters of the stairs of the main altar. On the left wall of the nave, the collapsed stonework above the lintel of the west window can be seen, as well as the neat masonry that sealed the window in colonial times. The stonework fell in above the window because the lintel woodwork burned out all the way through the wall during the fire in ca. 1830. Closer to the camera on the left can be seen the multiple sockets of the choir loft. The lowest socket is a three-part outline for the cobel beneath the main viga, the viga itself, and the lower railing of the choir loft bannister above. Above this triple socket, and a few inches north, are the middle and upper sockets of the choir loft bannister. On the right, or east wall, of the nave, an identical set of sockets can be made out. Closer to the transept, the notch of the east window of the nave can be seen. The sill of the window has collapsed almost to the level of the fill within the church. The fill at this time is only about three feet deep. Photograph by Charles Lummis, 1890. Courtesy Southwest Museum, # 24844. |

Figure 37. Quarai about 1900 from a photograph found in the files of the National Park Service. This is a print made from a negative made from a slide made of a print of the original negative. With so many generations of duplication, many of the details in the original have been lost, and the source of the photograph is unknown. Careful inspection and comparison with other pictures, however, recovers much useful information from the print. At the right background of the view, the walls of parts of the North House still stand, even though the main east wall visible in the Lummis photograph made in 1890 has fallen. Closer, just above the trees across the center of the photograph, the walls of several rooms of the east courtyard are visible, and just above them the walls in the area of rooms 11, 12, 13, and 29 can be seen. The imprints of most of the walls that adjoined the east wall of the church can be made out by comparison with other photographs. Courtesy National Park Service. |

LAS HUMANAS

Traveller's Tales

Las Humanas was not reoccupied in the same way as the other missions. The revival of interest in the land on the east slope of the Manzanos did not extend to the exposed, waterless country around that ruined mission and pueblo. Not until the danger of Apache raids began to fade after 1830 did even sheepherders and treasure hunters begin to visit the ruins. Because of this low level of human contact, the masonry and woodwork of San Buenaventura and its convento fared much better than that at the other Salinas missions.

By the 1830s, the stories associating Las Humanas with the tales and treasures of "Gran Quivira," as told to Coronado in the 1540s, were already old. [49] At first, treasure-hunting visits to the ruins were risky, and not many made the attempt. As the Apache hazard eased in the country east of the Manzanos, incidents of excavation increased. By the 1850s, treasure-hunting had left very noticeable marks on the hill of Las Humanas.

Some travellers who visited Las Humanas wrote descriptions of what they saw on the hilltop, and some made sketches or took photographs. These descriptions, sketches and photographs document the condition of the ruins in the mid-nineteenth century, and its final steps of decay before and after the National Park Service acquired the site.

David Wilson, 1835-36

In the winter of 1835-36, David Wilson and a group of six companions came across Las Humanas while looking for water between the Rio Grande and the Pecos. Wilson's description is brief. "We saw to the north of us . . . a large building; we went to the building and found it to be a large Church . . . the Church itself was built of stone, and stood almost in a perfect state of preservation, while all the other buildings had decayed." Later, in Santa Fe, when Wilson described the church, he was told that it was the "Grand Quivira." This is the earliest record of the use of the name in association with Las Humanas. [50]

Josiah Gregg, ca. 1839

Josiah Gregg travelled the Santa Fe Trail from 1831 to 1839, and in 1844 published Commerce of the Prairies, based on his observations. In this book, Gregg briefly described Las Humanas, under the name of "La Gran Quivira." He mentioned the walls of ruined stone buildings, including churches, still standing. He discussed cisterns for water collection, and described the "aqueducts" seen by a number of other visitors to the site. In his description, Gregg made a rather obscure reference to "the Spanish coat of arms" sculpted and painted on the facades of the buildings that appeared to be churches. Because of this remark, later visitors to the site, seeing no trace of such sculpture or painting, came to the conclusion that Gregg had not visited Gran Quivira himself, but had heard it described by others who had been there. Gregg narrated a brief version of the treasure-hunter's story in which all but one of the occupants of the town were killed during the Pueblo revolt, and the survivor later told the tale of "immense treasures" buried in the ruins. Gregg remarked that "credulous adventurers have lately visited the spot," searching for the treasure. Considering the dates of his travels and the preparation of his manuscript, Gregg probably talked to these "credulous adventurers" about 1839. [51]

Major James Henry Carleton, 1853

Major Carleton visited the ruins of Las Humanas 180 years after its abandonment. He noted the measurements of the church of San Buenaventura and said that the walls stood about thirty feet high. He also described the condition of the choir loft. The main viga and the two pillars that supported it were still up, although the pillars were badly decayed. Several of the secondary vigas were still in place, as were "entablatures" in the side walls. Carleton removed one of the secondary vigas by cutting it into three pieces. Carleton stated that the entablatures were about twenty-four feet long and 1/2 or two feet in width. The entablatures were carved "very beautifully, indeed, and exhibits not only great skill in the use of various kinds of tools, but exquisite taste on the part of the workmen in the construction of the figures." The secondary vigas had decorative carving on the bottom and sides, but not on the top.

The convento of San Buenaventura received little mention in Carleton's report. It was referred to only as a "monastery, or system of cloisters, which are attached to the cathedral."

Carleton briefly described San Isidro, which he called "the chapel." He gave its principal measurements, including a wall thickness of three feet eight inches, and remarked with puzzlement that the building was "apparently in a better state of preservation than the cathedral, but yet none of the former wood-work remains in it."

Carleton remarked that he had met men in the Manzano area who had herded sheep in the area of Las Humanas "in their youth," and discussed the legends of buried treasure associated with "Gran Quivira," as the ruins had come to be known. He mentioned treasure-hunters' pits in San Isidro and San Buenaventura, "every room" in the convento, the ruins of the pueblo, and here and there around the ruins. He also referred to Gregg's description of the "Spanish coat of arms" on the buildings, and concluded that Gregg had not, in fact, visited the ruins. [52]

Robert B. Willison, 1872

Deputy Surveyor Robert B. Willison of the United States Surveyor General's Office surveyed the base line for New Mexico public surveys across Las Humanas in early 1872. In his field notes, prepared in April, Willison wrote a lengthy description of the structures he saw. He gave the measurements of the church, and said that "the carved timbers in the church are still in a good state of preservation; a portion of the roof [the choir loft] still remains." In the convento, he saw window frames in place, on which "the mark of the carpenter's scribe is still plainly visible." Willison saw a number of excavations made by treasure hunters in the ruins of the village, but did not specifically mention digging in the church. He did not describe San Isidro at all. [53]

Lieutenant Charles C. Morrison, 1878

Lieutenant Charles C. Morrison of the United States Army visited Las Humanas in mid-1878. He wrote a detailed description of the ruins and drew several sketches, reproduced by lithograph in the published report. [54] Morrison's work is of great value because he supplied the earliest visual records of the church and convento, as well as the only drawing of the choir loft woodwork. He also provided the earliest detailed description of the convento. Morrison said that the convento walls were two feet thick, and that he could see the remains of a plastered surface on them. He had the impression that the woodwork in the convento had been painted. "Many of the window-frames were intact," he says, "one door-frame, showing that the door turned on wooden pivots for hinges, was well preserved." His plans of the church and convento are quite accurate and were not improved upon until the 1930s. The sketch of the ruins as seen from the southeast shows that the three windows along the front of the convento had their lintels intact, while the lintels of the windows and doors of the south side, the sacristy storeroom (room 16), the choir loft stairwell (room 1) and the patio walls had collapsed. With the collapse of the lintel above the doorway from the kitchen (room 4) into the second-story storeroom (room 5), the entire southeast corner of the building had fallen outward, as well as the entire east wall of the storage building (rooms 5 and 6). No frames survived in most of the windows and doors of the second level of the church. Morrison showed the ruins of the second courtyard as far lower than they actually were, apparently to get them out of the way of his view of the main convento rooms.

In his description and sketch of the choir loft, Morrison supplied more details than had previous observers. The central section of the main beam and the western ends of most of the secondary vigas had fallen, but enough remained for Morrison to work out the appearance of the structure. The secondary vigas were "squared beams, eleven by thirteen inches, placed about three feet apart, the sides exposed to view being finished with the squares and diagonals marking the type of the best of the ornamental work." The floor of the choir loft "consisted of small split poles laid in juxtaposition diagonally" from one secondary viga to the next. "On these diagonals was a heavy, rudely woven matting or thatching of straw." Apparently none of the earth covering above the matting survived. His sketch shows the intricacy of the carving on the entablatures described by Carleton, although his depiction of the shape of the corbel beneath the main viga is not entirely accurate. He showed the length of the corbel about twice what it actually was, as seen in later photographs.

Figure 38. San Buenaventura in 1877, as sketched by Morrison. Morrison's plan of the church and convento are quite accurate, much more so than Bandelier's plan made six years later. Morrison's plan of the pueblo and churches is distorted, but not much worse than Bandelier's map. Morrison's major contribution, however, is the perspective drawing of the church ruins and the detailed sketch of the choir loft woodwork. Although a comparison with surviving fragments of the choir beams in later photographs shows that Morrison did not depict the shape of the corbel with complete accuracy, he still was able to capture the intricacy of the entablature carving and the complex interconnections of the various pieces of woodwork. |

Adolph Bandelier, 1883

Adolph Bandelier spent two days at Las Humanas in early January, 1883. While there he took seven photographs of the church, convento, and pueblo, and prepared rough sketches of their plans. He noted the dimensions of San Isidro and prepared a sketch plan of San Buenaventura with dimensions. The sketch of the convento was inaccurate in many details of the plan. He said very little about the structural details of the buildings in his journal, and added little more in his final report. It is his photographs that are of the greatest interest.

Figure 39. San Buenaventura in 1883, as photographed by Bandelier. The door and window openings high on the wall of the church are still sharp-edged and the tops of the walls flat, straight lines. Biblioteca Apostólica Vaticana, Archivo Fotographico, #14116-49, courtesy Charles Lang. |

Figure 40. The interior of the church of San Buenaventura as Bandelier saw it in January, 1883. The right stub of the viga that formed the main support for the choir loft, and its corbel, are both still set into the north wall. These are the same corbel and viga sketched by Morrison in 1877. The entablature running from the viga to the front wall of the church, however, has been removed. The rubble fill against the walls in the nave of the church is only 1-1/2 to two feet higher than the present floor surface. Biblioteca Apostólica Vaticana, Archivo Fotographico, # 485-50, courtesy Charles Lang. |

Only three views of San Buenaventura are available. They show the buildings from the southeast and the far northwest, and one view of the interior of the nave. In the nave, the rotted remains of about five feet of the primary beam of the choir loft, with its corbel in place, can be seen.

The distant view from the northwest shows that the wall above the doorway into the baptistry was in place, indicating that the lintel beams survive here. The tops of the walls of the church were very level, with irregularities of less than one or two feet. The nave wall up to the transept is higher than the transept walls, which in turn are higher than the apse walls. The apse and sacristy wall tops are almost perfectly straight.

The view from the southeast, almost exactly the same view as that drawn by Morrison ten years before, shows the changes that had occurred in that time. The lintels of the three eastward-facing windows along the front of the convento had failed or been removed, allowing the walls above to collapse. This resulted in the loss of almost the entire front wall. The southwest corner of the stairwell to the choir loft (room 1), next to the portería entrance doorway, had partially collapsed. The outermost beam over the church entrance doorway had been pulled out, although it is difficult to be sure that it was surviving in 1877 using Morrison's drawing. The wall tops along the south side of the church were more level than those along the north side. Again, the transept walls are distinctly lower by perhaps two feet than those of the nave. The doorway into the choir loft at the second level of room 1 is sharply defined, with a square upper corner to the stonework at its east side and traces of the splay visible. The top of the north wall of the nave can be seen through the opening. West of the choir doorway, the first nave window is equally sharp and clear, along with its splay. The second, westernmost window is more irregular, with extensive collapse of its upper corners. The sockets for the vigas of rooms 1 and 16 are visible at the level of the bottom edges of the windows and doorway through the nave wall. The splay surfaces of the front doorway and the choir window above can be seen, as well as the lintel beam above the doorway.

On his plan of the pueblo, Bandelier showed the walls of a hut and a "dry well" built between kiva J and mound 7. [55] Hayes located the foundations of this hut, and described it as feature 9 in his report on excavations at Gran Quivira. Hayes found Bandelier's "dry well" to be a trial mine shaft. Hayes considered the hut to have been a line shack for herdsmen, or a prospector's hut. [56]

Charles Lummis, 1890

Charles Lummis visited Las Humanas in 1890 and made a number of photographs of the ruins. Only five of these have been located so far, although at least three more are known to have existed.

Lummis later described some of what he had seen at the ruins. He thought that the structure was "little shorn of its first stature." He remarked that the lintels over the main doorway of the church held up "fifteen feet of massive masonry." In the convento,

in one of the apartments of the honeycomb is still a perfect fireplace; and here and there over the vacant doorways are carved-wood lintels, their arabesques softened but not lost in the weathering of centuries. Some of the rafters must have weighed a ton and a half to two tons. [57]

Figure 41. San Buenaventura from the south in 1890, as photographed by Charles Lummis. Courtesy Southwest Museum, # 24834. |

Figure 42. The interior of the church of San Buenaventura in 1890. Lummis photographed the south end of the main viga that supported the choir loft, with its corbel, and the outside of the lintel over the front door of the church. It was this photograph that allowed the identification of the beam presently over the door as the beam closest to the camera in the lintel, by the distinctive pattern of knots and cracks. Courtesy Southwest Museum, # 24825. |

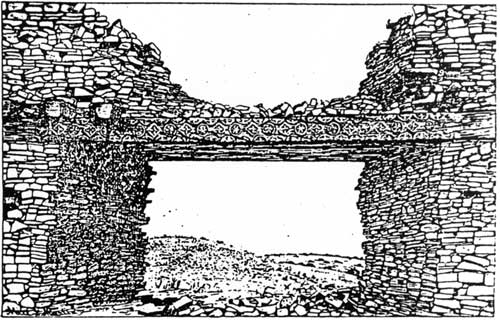

Figure 43. The doorway from the church of San Buenaventura into the sacristy in 1890. This photograph by Lummis shows the decorative carving on the beam over the doorway, and the appearance of the sacristy window. Courtesy Southwest Museum, # 24836. |

John W. Virgin, 1894

In February, 1894, John W. Virgin visited the ruins. He later wrote his own description of San Buenaventura. [58] The church walls stood twenty-five feet high, he said. The choir loft had been supported by a large beam measuring ten inches by sixteen inches, resting on a vertical pillar sixteen inches square. [59] On the large beam rested smaller beams, each with one end set into the front wall of the church. The smaller beams measured 8 1/2 inches by 10 1/2 inches (Morrison earlier had given the measurement of these beams as eleven inches by thirteen inches). All the beams were carved with elaborate decoration. In a letter written thirty-six years later, Virgin added more details to his description of the church, without the picturesque style that confuses what he saw with what he suspected or had heard. "When I was there the only timbers in place [in the church] were the square timbers over the front door, with a little of the wall they had supported still there." He added that the ends of the main beam were in the wall at the time of his visit.

In later correspondence, Virgin described finding a section of one of the carved beams in a large pit about a mile from San Buenaventura, probably during this visit. He gives its measurements as ten inches by twelve inches and perhaps twenty-five to thirty feet long, and said that it was weathered gray and had sever pitting and decay on the upper surface. The other three surfaces were covered with carved decoration. He had to cut it into two sections to lift it out of the pit. He considered it to have been the middle section of the main beam, and thought it had been cut out by a vandal to be used as a ladder to reach the bottom of the pit. Note that the measurements Virgin gave for this beam do not match the measurements stated for any of the beams in his article. [60]

Virgin said that there were three windows on each side of the nave, and the floor of the church was "laid in neatly-jointed limestone flags." Both these statements were incorrect. He could see the lower portions of three openings in the south wall, and presumably interpreted the slight irregularities of the top of the north wall as the last traces of similar window openings. He could probably see the flagging in front of the portería and the entrance to the church (that at the front of the church is covered with a thin layer of soil and grass today), and assumed that the stones continued throughout the interior of the church. Photographs taken before and after his visit all show that the interior ground surface of the church was covered with from several inches to two feet of rubble, so that he could not have seen a floor surface. [61]

San Isidro, said Virgin, presented "such a confusion of fallen walls and dirt-covered debris as to defy any attempt to trace its form or determine its dimensions with much accuracy." This should be taken to mean only that Virgin did not measure the building. Several people before and after his visit had no difficulty measuring the structure and drawing an accurate plan of it, including Willison in 1872, Bandelier in 1882, and Ida Squires and Anna Shepard in 1923.

Virgin illustrated his article with etchings made from two photographs. One of these can be identified as one of the missing Lummis photographs from his 1890 visit. The other, showing the inner face of the front of the church, looks so much like the Lummis photograph showing the outside of the same wall that it, too, is probably a missing Lummis photograph.

Figure 44. The inside face of the lintel over the entrance to the church of San Buenaventura in ca. 1890, looking east. This is the engraving published in 1898, but suspected to be made from a lost Lummis photograph made in 1890. |

Figure 45. A beam from San Buenaventura. It was photographed in 1896 in front of a shed of the Dow House next to the post office of Gran Quivira. This beam has decorative carving on the middle section of the face towards the camera. The carving, cracks, and weathering all match the details of the beam in the engraving in the previous illustration, making it very likely that this beam had been removed from the inner face of the facade of San Buenaventura between 1890 and 1896. Courtesy National Park Service, #GQ-448. |

Figure 46. The north portion of the convento of San Buenaventura about 1900. The room at the right is room 16, and the north corridor runs diagonally across the center of the picture to the sacristy in the background. This photograph is of great importance, because it records the last surviving traces of the roof of the convento. Six beam sockets can be seen in the top of the wall between the sacristy and room 15. The second socket from the left still has the stub of a beam set in it. The sockets and beam stub survive here because the thickness and height of the sacristy wall kept it from collapsing to a level below the beam sockets of the convento, as happened everywhere else in the convento except along the south side of the church. The sockets in room 15 were about 10 feet above the present floor level, three feet lower than the sockets in the south wall of the church in rooms 1 and 16. Courtesy New Mexico State Monuments, # 40667. |

Visitors Between 1894 and 1923

A number of photographs taken between about 1890 and 1923 are available, although undated at present. These show the process of collapse of the buildings, and can be roughly divided into two periods by the presence or absence of the beams over the church entrance, which were removed between 1896 and 1905. [62] The innermost beam with its carved decorations had been pulled out by 1896 and lay next to the Dow house in the village of Gran Quivira at the foot of the hill for several years. [63]

Between 1890 and 1905, the lintel beams over the sacristy window disappeared, probably pulled out by souvenir hunters. The carved beams over the doorway from the church to the sacristy probably disappeared about the same time. The lintels over the window facing west and most of the other walls of room 14 collapsed, leaving a splintered stub of wood from one of the beams in place until about 1905. The doorway opening north into the corridor from room 10, the window facing south from room 7, and the doorway from room 7 to room 8 all fell during the same period.

After 1905, lintel beams remained in room 10 over the window facing south onto the second courtyard and over the doorway to room 11, and in room 15 over the doorway south to room 14 and the small window facing west into the sacristy. In 1919 the United States Government placed the care and protection of Gran Quivira in the hands of the newly created National Park Service. The doorway between rooms 15 and 14 fell soon after National Park Service maintenance of the ruins began about 1920, and then the doorway from room 10 to 11. The last lintels to collapse were those for the window south from room 10 and those for the window west from room 15 into the sacristy, not long before excavation and a full stabilization program began in 1923.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

sapu/hsr/chap9.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006