|

Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument New Mexico |

|

NPS photo | |

Pueblos of the Salinas Valley

In the stones of the Salinas Valley pueblo ruins are faint echoes of the communities that lived there 300 years ago. Before they left the area in the 1670s, Pueblo Indians forged a stable agricultural society whose members lived in apartment-like complexes and participated, through rule and ritual, in the cycles of nature. Two ancient southwestern cultural traditions, the Ancestral Puebloans—often called Anasazi—and Mogollon, overlapped in the Salinas Valley to produce the later societies at Abó, Gran Quivira, and Quarai. These groups had roots as far back as 7,000 years ago and were themselves preceded by nomadic Indians who may have arrived as early as 20,000 years ago.

As the southwestern cultures evolved, better agricultural techniques from Mexico and the migration of Tompiro- and Tiwa-speaking peoples from the Rio Grande spurred the growth of settlements in the Salinas Valley. By the 900s substantial Mogollon villages flourished here. The dwellers practiced minimal agriculture supplemented by hunting and gathering, made a simple red or brown pottery, and lived in pit houses and, later, above-ground jacales of adobe-plastered poles. By the late 1100s the Anasazi tradition from the Colorado Plateau, introduced through the Cibola (Zuñi) district and Rio Grande pueblos, began to assimilate the Mogollon. The contiguous stone-and-adobe homes of the Anasazi represented the earliest stage of the pueblo society later encountered by the Spanish. Over the next few hundred years the Salinas Valley became a major trade center and one of the most populous parts of the Pueblo world, with perhaps 10,000 or more inhabitants in the 1600s. Located along major trade routes, the villagers were both producers and middlemen between the Rio Grande villages and the plains tribes to the east. They traded maize, piñon nuts, beans, squash, salt, and cotton goods for dried buffalo meat, hides, flints, and shells.

By 1300 the Anasazi culture was dominant, although the Salinas area always lagged behind the Anasazi heartland to the north in cultural developments. Brush-and-mud jacales had evolved into large stone complexes, some with hundreds of rooms, surrounding kiva-studded plazas. Besides the plants already mentioned, the inhabitants ate wild plants, raised turkeys, and hunted rabbits, deer, antelope, and bison. They wore breech cloths, bison robes, antelope and deer hides, and decorative blankets of cotton and yucca fiber. Turquoise and shell jewelry, obtained by trade, brightened rituals. The Spaniards were impressed by the Pueblos' weaving, basketmaking, and fine black-on-white pottery, a technique the Salinas people borrowed from the Rio Grande pueblos. The Salinas pueblo dwellers were an adaptable people who drew what was useful om more advanced groups. But strong influences from the Zuñi district, the Spanish explorers, and deteriorating relations with the Apaches to the east radically altered pueblo life. In the 1670s the Salinas villages were abandoned, and their peoples dispersed.

Native Southwestern Architecture

The Salinas peoples' communal life was reflected in their shared-wall, stone-and-adobe pueblos. The earliest pueblos at some sites were concentric circles of wedge-shaped rooms surrounding a kiva. These were later covered by rectangular complexes with hundreds of rooms for living and storage. Daily chores were performed on roofs and in the plazas, which on religious days were stages for ceremonial dances. For centuries before pueblos were developed, Indians lived in pit houses covered with pole-and-mud frames.

The Coming of the Spaniards

Soon after Spain had conquered and colonized Mexico, tales of great wealth to the North drew explorers to New Mexico. Coronado's expedition in 1540 failed to turn up the fabled land of Quivira although the name and story lingered on. In 1598 a party led by Juan de Oñate came to New Mexico to plant a permanent colony. He called salt, which was abundant in Salinas, "one of the four riches of New Mexico," but the other expected riches—especially mines—failed to materialize. Agriculture too proved difficult in the harsh climate. Relations with the Indians soured when the soldiers attempted to collect tribute to the Crown. Spain finally concluded that New Mexico would never be profitable. However, the Pope had charged the Spanish Crown with Christianizing the natives of the New World. Philip II therefore decided to maintain the colony, partly at the Crown's expense, as primarily a missionary effort. While many of the Franciscan missionaries were sincere and well-intentioned, the overlapping privileges granted to the church and civil authorities inevitably led to conflict between the Franciscans and the governors.

Relations with the pueblos were determined mainly through the encomienda system, in which ranking citizens (encomenderos) were appointed by the governor to provide protection, aid, and education to Indians and military support for the government in return for the privilege of collecting tribute. But the system was abused, and New Mexico was too remote for the exploitation to be checked by higher authorities. The Franciscans tried to lighten the burden on the Indians, but the settlers and government refused to give up the profitable arrangement, and in any case, the friars themselves placed heavy demands on the pueblos to support the missions. Still, some changes brought by the Spanish were beneficial. Wheat and wheat bread, fruit trees, and grapes were introduced. Cattle, goats, and sheep became a fixed part of the economy. Craftsmen began working metal.

In the end cultural conflict and natural disaster devastated the Salinas pueblos. The Apaches, formerly trading partners, now raided the pueblos for food and in retribution for Spanish slave raids in which Pueblo Indians had participated. The Pueblos might have survived the raids, but they—and the Apaches and Spaniards—were hit during the 1660s and 1670s with drought and wide-spread famine that killed 450 people at Gran Quivira alone. Recurring epidemics further decimated the populace, which had little resistance to introduced diseases. The ability of the pueblos to withstand these disasters may have been weakened by the disruption of their culture under Spanish rule. In any event, the Salinas pueblos and missions were abandoned during the 1670s, and the surviving Indians went to live with cultural relatives in other pueblos. In 1680 the pueblos north of Salinas, in an uncharacteristic show of unity, revolted and expelled the Spaniards from New Mexico. In the general exodus of Indians and Spaniards, the Piro and Tompiro survivors of the Salinas pueblos moved south with the Spaniards to the El Paso area. They were absorbed by Indian communities there, making them the only linguistic group among the Pueblo Indians during the historic period to lose their language and their homeland.

A Clash of Religions

The Spanish and Pueblo priests viewed each other's religions through the lens of their own cultures. To pueblo leaders who directed collective rituals to influence a pantheon of gods, the Christian stress on the relationship between one god and one human was alien. The Franciscans, regarding the pueblo religion as idolatry, told the Indians that their salvation depended on their willingness to undergo religious instruction. The missions for this purpose were self-sufficient communities that included the pueblo, church, friars' quarters, work areas, and the pueblo's fields and hunting and gathering areas. The Indians were instructed in European crafts and husbandry in an attempt to bring them into the Spanish society. The process was intended to culminate in citizenship in the Spanish Empire. But suppressing the masked Kachina dances and kiva rituals proved difficult for the priests. They were thwarted by the local civil authorities, who pressured them to speed up the conversion so the new Christians could work for the settlers, then encouraged the Indians to continue the ancient dances. The Inquisition came to the priests' aid. The Indians, caught in the middle, were not subject to the Inquisition, but a Spaniard who encouraged idolatry did so at great risk.

Every Pueblo Indian was a member of one of the religious kiva societies into which the pueblo was divided. The rules were stringent in these highly organized theocracies, but in times of illness or need the individual could expect aid from his or her group—and was obligated to offer it to others. The survival of the group was the motivating principle of the Pueblo religion. A communal effort was needed to bring rain, seed fertility, and dependable harvests. Participation in the rituals by the entire group maintained the universal harmony that allowed plants—and humans—to flourish. Kachina spirits, who no longer lived on Earth, were crucial to the Pueblos, for they carried human prayers to the gods. When the Kachina dancers performed the correct movements the Kachinas heard them, and if the people were leading good lives, the gods heeded their requests. The Pueblo priests at first were willing to accept the new Christian god and saints into their pantheon, but soon concluded that these deities wouldn't heed—or weren't powerful enough to grant—their supplications for summer rain and fruitful harvests. When some Franciscans destroyed the Kachina masks and burned the sacred kivas, the break was complete. In the century after the Reconquest of 1692, Spanish officials relented and allowed the practice of native religions alongside Christianity, but the change of heart came too late for the Salinas pueblos. They had been abandoned a few years before the revolt.

Exploring Salinas

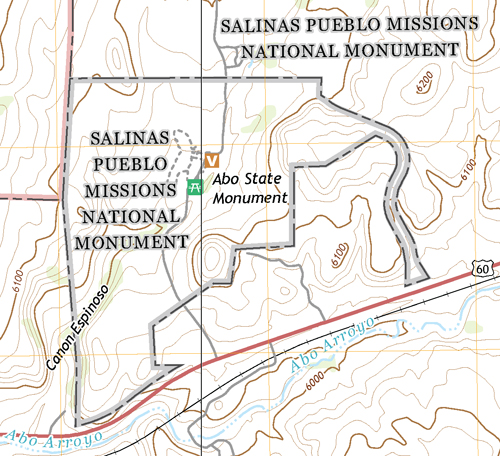

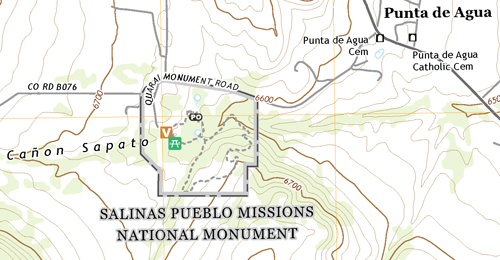

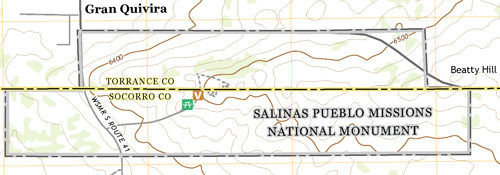

(click for larger maps) |

Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument is open daily, except Thanksgiving, December 25, and January 1. The visitor center is in Mountainair, N.M., west of the U.S. 60 and N.M. 55 junction. Services are available in town.

Picnicking/Camping There are picnic areas at Abó, Quarai, and Gran Quivira (no camping allowed). Nearby campgrounds: Cibola National Forest and Manzano Mountains State Park.

Safety/Regulations For a safe visit and to help protect the park please follow these regulations. • Watch your step and stay on designated trails; deep rooms are near the trails. Keep control of your children at all times. • Pets must be kept on a leash. • Climbing on the walls is prohibited. • If you see a rattlesnake leave it alone and report it to a park ranger. • All cultural and natural features are protected by federal law. Collecting artifacts or disturbing archeological sites is strictly forbidden.

Abó

The site has sophisticated church architecture and a large unexcavated pueblo.

On an expedition to investigate the Salinas district in 1853, Maj. J.H. Carleton came upon Abó at dusk. "The tall ruins," he wrote, "standing there in solitude, had an aspect of sadness and gloom . . . . The cold wind . . . appeared to roar and howl through the roofless pile like an angry demon." Carleton recognized the structure as a Christian church but did not know that the "long heaps of stone, with here and there portions of walls projecting above the surrounding rubbish," were the remains of a large pueblo. Located on a pass opening onto the Rio Grande Valley, Abó had carried on a lively trade with people of the Acoma-Zuñi area, the Galisteo Basin near Santa Fe, and the plains. Salt, hides, and piñon nuts passed through this trading center. Springs provided water for crops, households, and turkeys.

Abó was a thriving community when the Spaniards visited the Salinas Valley in 1581. Franciscans began converting Abó residents in 1622, and by the late 1620s the first church was finished. A second church was built with a sophisticated buttressing technique unusual in 1600s New Mexico. But the good times did not last. Battered by the disasters that struck the other Salinas pueblos, the people of Abó left sometime between 1672 and 1678 to take refuge in towns along the Rio Grande.

Quarai

This site features exhibits and the most complete Salinas church.

Like Abó and Gran Quivira (also called Las Humanas), red-walled Quarai was a thriving pueblo when Oñate first approached it in 1598 to accept its oath of allegiance to Spain. Three of Quarai's Spanish priests were head of the New Mexico Inquisition during the 1600s, including Fray Estevan de Perea, Custodian of the Franciscan order in the Salinas Jurisdiction and called by one historian the "Father of the New Mexican Church." Despite the horrors associated with the word "Inquisition," records from hearings show that the early inquisitors, in New Mexico at least, were compassionate men usually capable of separating gossip from what the church regarded as serious transgressions.

In one case, tensions between church and state peaked when Perea charged the alcalde mayor of Salinas with encouraging the native Kachina dances. That case was dropped, but the alcalde's continued disruptions at the mission prompted the Inquisition to banish him. Testimony recorded by Perea and others for trials at Mexico City provides a valuable picture of Spanish-Indian relationships in the 1600s. Spain's sophisticated legal system was applied (when it worked as intended) to protect the Indians' civil and property rights. Perhaps the Spanish colonists learned the patience and endurance that the Pueblos had practiced for hundreds of years.

Gran Quivira

Here you can see two churches, excavated Indian structures, and exhibits.

Gran Quivira (also known as Las Humanas), largest of the Salinas pueblos, was an important trade center for many years before and after the Spanish entrada. The people resisted the newcomers at first, but they reconciled themselves to the Spanish presence and borrowed freely from them, as they had from other cultures. The pueblo's black-on-white pottery took on new forms reflecting European styles. Other artifacts from the site recall the Spanish presence: Chinese porcelain, metal tools, religious medallions, and evidence of cattle, goats, sheep, horses, and pigs.

Documents from the 1600s tell of strife between missionaries and the encomenderos, who complained that the friars kept the Indians so busy studying Christianity and building churches that the encomenderos could neither use Indian labor nor collect their tributes. In the 1660s friars burned and filled kivas in an effort to exterminate the old religion. Hurriedly altered above-ground rooms converted to kivas attest to the Pueblo priests' response. A second church was begun around 1659, but was never completed, partly because Apache raids had begun. In 1672, further weakened by drought and famine, the inhabitants (only 500 by that time) abandoned the pueblo.

Source: NPS Brochure (2014)

Documents

A Tale of Two Pueblos (John L. Kessell, extract from El Palacio, Vol. 85 No. 3, Fall 1979)

An Archaeological Survey and Assessment of Gran Quivira National Monument, New Mexico (Patrick H. Beckett, December 1981)

Ancient Quarai Ruins Taken Over by Museum (extract from El Palacio, Vol. 1 No. 1, November 1913)

Availability of Ground Water at Gran Quivira National Monument, New Mexico USGS Open-File Report 57-19 (Alfred Clebsch Jr., 1957)

Characterization of Near-Surface Geology and Possible Voids Using Resistivity and Electromagnetic Methods at the Gran Quivira Unit of Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument, Central New Mexico, June 2005 USGS Scientific Investigations Report 2006-5176 (Lyndsay B. Ball, Jeffrey E. Lucius, Lewis A. Land and Andrew Teeple, 2006)

Circular Relating to Historic and Prehistoric Ruins of the Southwest and Their Preservation (Edgar L. Hewitt, 1904)

Comments on the Indians' Water Supply at Gran Quivira National Monument (Richard M. Howard, extract from El Palacio, Vol. 66 No. 3, June 1959)

Excavations in a 17th-Century Jumano Pueblo: Gran Quivira Archeological Research Series No. 8 (Gordon Vivian, 1961)

Fieldwork at Gran Quivira, 1926 (extract from El Palacio, Vol. 21 No. 9, November 1, 1926)

Final Interpretive Prospectus, Proposed Salinas National Monument, New Mexico (1976)

Foundation Document, Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument, New Mexico (September 2014)

Foundation Document Overview, Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument, New Mexico (2016)

General Management Plan/Development Concept Plan, Salinas National Monument, New Mexico (October 1984)

Geological Resources Inventory Report, Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR-2018/1706 (Katie KellerLynn, August 2018)

History of Quarai (Erik K. Reed, December 1940)

Hydrologic Monitoring for Cañon Sapato in the Quarai Unit of Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument: 2010–2011 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2012/358 (Ellen S. Soles and Stephen A. Monroe, September 2012)

Hydrologic Monitoring in Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument: Water Years 2012 through 2014 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2015/966 (Ellen S. Soles and Stephen A. Monroe, August 2015)

"In the Midst of a Loneliness": The Architectural History of the Salinas Missions, Historic Structures Report (HTML edition) Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers No. 15 (James E. Ivey, 1988)

International Dark Sky Park Designation Nomination Package, Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument (August 2016)

Inventory of Exotic Plant Species Occurring in Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SCPN/NRTR—2011/422 (Julie E. Korb, January 2011)

Junior Ranger Booklet, Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Links to the Past: New Mexico's State Monuments — Abó/Quarai (extract from El Palacio, Vol. 83 No. 2, Summer 1977)

National Monuments of New Mexico: Gran Quivera, One of the Cities That Died of Fear (extract from El Palacio, Vol. 5 No. 14, October 26, 1918)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

San Gregorio de Abo Mission (Abo State Monument) (Robert M. Utley, May 26, 1958; Designation: October 15, 1966)

Quarai (Francine Weiss, April 28, 1976; Designation: October 15, 1966)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SAPU/NRR-2022/2393 (Kathy Allen, Andy J. Nadeau and Andy Robertson, May 2022)

Quarai: Living Mission to Monument (John P. Wilson, extract from El Palacio, Vol. 78 No. 4, January 1973)

Quarai Parking Lot Rehabilitation: Archeological Testing Program, Salinas National Monument Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers No. 27 (Walter K. Wait and Peter J. Mckenna, 1990)

Report of Regional Geologist on Gran Quivira National Monument, New Mexico (Chas. N. Gould, August 1, 1936)

Report on Sullys Hill Park, Casa Grande Ruin; the Muir Woods, Petrified Forest, and Other National Monuments, Including List of Bird Reserves: 1915 (HTML edition) (Secretary of the Interior, 1914)

Report on Wind Cave National Park, Sullys Hill Park, Casa Grande Ruin, Muir Woods, Petrified Forest, and Other National Monuments, Including List of Bird Reserves: 1913 (HTML edition) (Secretary of the Interior, 1914)

Salinas Pueblo Missions: The Early History (©Jeanette L. Wolfe, Master's Thesis University of New Mexico, May 2013)

San Gregorio de Abo Mission (Joseph H. Toulouse, Jr., extract from El Palacio, Vol. XLVII No. 3, March 1940)

Summary of test drilling, Gran Quivira National Monument, New Mexico USGS Open-File Report 60-142 (F.B. Titus Jr., 1960)

The 1939-1940 Excavation Project at Quarai Pueblo and Mission Buildings, Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers No. 29 (Wesley R. Hurt, 1990)

The Abó Painted Rocks Documentation and Analysis (Sally J. Cole, October 1984)

The Cities That Died of Fear (The Story of the Saline Pueblos) (Paul A.F. Walter, extract from El Palacio, Vol. 3 No. 4, August 1916)

The Excavation and Repair of Quarai Mission (Albert Grim Ely, extract from El Palacio, Vol. XXXIX Nos. 25-26, December 18, 25, 1935)

Geology of the Gran Quivira Quadrangle, New Mexico New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources Bulletin 26 (Robert L. Bates, Ralph H. Wilpolt, Archie J. MacAlpin and Georges Vorbe, 1947)

The Language of the Saline Pueblos: Piro or Tiwa? (Albert H. Schroeder, extract from New Mexico Historical Review, Vol. 39 No. 3, 1964, ©University of New Mexico)

The Mission of San Gregorio de Abó (Joseph H. Toulouse, III, extract from El Palacio, Vol. XLV Nos. 24-25-26, December 14, 21, 28, 1938)

The Work on the Old Quarai Mission, 1935 (Donovan Senter, extract from El Palacio, Vol. XXXVII Nos. 21-22-23, Nov. 21-28-Dec. 5, 1934)

Vegetation Classification and Map: Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SCPN/NRTR—2012/553 (Esteban Muldavin, Yvonne Chauvin, Amanda Kennedy, Teri Neville, Paul Neville, Keith Schultz and Marion Reid, February 2012)

Vertebrate Paleontological Resources from National Park Service Areas in New Mexico (Vincent L. Santucci, Justin Tweet, David Bustos, Jim Von Haden and Phillip Varela, extract from New Mexico Museum of Natural History Bulletin 64, 2014)

sapu/index.htm

Last Updated: 20-Mar-2025