|

SITKA

Administrative History |

|

Chapter 4:

SITKA NATIONAL MONUMENT, MIDDLE YEARS

| INTRODUCTION |

|

|

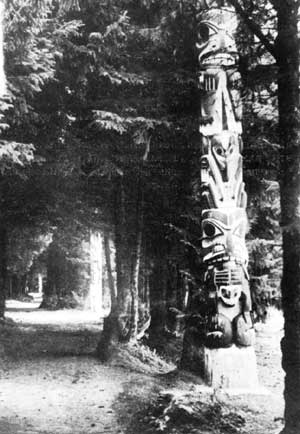

Totem walk at Sitka National Monument, ca.

1935. (Photo courtesy of Anchorage Museum of History and Art, #B80.50.30) |

Overview

This section treats pre-World War II management of the park including preparation of the first master plan for Sitka National Monument, the Civilian Conservation Corps-U.S. Forest Service project to restore or recarve totems at the park and from other areas of Alaska, the war years when park service personnel had only limited access to areas of the park being used by the U.S. Army and the U.S. Navy, and the post-war years through 1959.

The period included removal of inholders from the park boundaries, efforts to obtain government housing for park personnel, war-related gravel dredging operations at the mouth of Indian River, erection of coastal defense installations within the park, navy efforts at river bank erosion control, and an expanded man date for park personnel to investigate and document historic properties throughout Sitka. The post-war period included debates over integrity of the park, when it was contemplated returning the area to local jurisdiction if the Indian fort site Could not be located by archeological examination, and possible removal of the totem poles as exotic to the park location; archeological verification of the fort site in 1957; discussions regarding treatment of the fort site, battlefield, river, replication and rehabilitation of totem poles, and the vistas from the park; and renewed consideration of establishing Sitka as a "Williamsburg of the Sub Arctic."

Other events falling into this period include assumption of maintenance of Sitka National Cemetery by park personnel, permission for operation of an asphalt hot plant on the east site of Indian River and subsequent burial of asphalt within park boundaries and reforestation, renewed gravel dredging at the mouth of Indian River, and razing of the Russian blockhouse replica donated to the park in 1926.

Territorial governor initiates totem pole project

Alaska's governor John W. Troy submitted the final proposal of the late 1930s that affected the resources of Sitka National Monument. He wrote to A.E. Demaray, a senior park service official, to suggest that it would be possible to get Civilian Conservation Corps help not only for landscaping at Sitka, but also to rehabilitate the totem poles there. Such work would need a National Park Service technical advisor. It could begin as early as October 1938. [184]

Demaray responded that the park service was interested. It had "no general plan of development for Sitka National Monument," and would be glad to participate in the program. He regarded it as essential that a technician be employed to see that the work was properly planned and executed. Would the Alaska Civilian Conservation Corps (administered by the U.S. Forest Service) be able to employ the technician? If arrangements could be made, Demaray said, details would be worked out by the park service regional office at San Francisco. [185]

Alaska Regional Forester B. Frank Heintzleman, who may have been behind Troy's original suggestion, followed it up in January of 1939. The Forest Service had obtained Works Progress Administration funding for totem pole restoration. He telegraphed Demaray with the news that funds were available. If the park service could provide a qualified foreman, the project would begin. [186] Cammerer, now Director of the National Park Service, replied that no park service specialists were available to super vise the work. The service could pay for the services of an ethnologist or qualified graduate student in anthropology to give initial supervision. He suggested looking for such an expert at the University of Washington or the University of Alaska. If such scientific assistance were not available, the project could go ahead so long as before and after photographs were made and "record card file" documentation of work was created. [187]

By April of 1939 Heintzleman was able to write to Cammerer that the totem pole work at Sitka was underway with WPA funds. He enclosed a photographic record of the poles in place on February 18. The Forest Service would submit a final report when the work was finished. [188]

The Alaska Road Commission provided a dump truck for the project. The Forest Service Wood Products Laboratory sent advice on preservation treatment for the poles. John Maurstand served as foreman for the project, with George Benson as chief carver and nine Indian workers. The WPA funds were used up by March and the Forest Service continued work with Civilian Conservation Corps money. About half of the old poles, many of which were badly deteriorated, were duplicated. Duplicates and repaired poles were treated with Permatox B, painted with compounds care fully constructed to match original Native colors, and then treated again with Pentra-Seal. [189]

Most of the work at Sitka was completed by March of 1940. Although plans were discussed to build an open air shed in which to store originals of the duplicated poles, they were eventually shunted aside to uncovered storage on skids. [190]

While the totem pole work was beginning, the park service began to reassess its treatment of Sitka National Monument's resources. Mount McKinley National Park Superintendent Frank T. Been and Earl A. Trager of the service's research and information bureau visited Sitka to look things over. [191] Carl P. Russell, Supervisor of Research and Information for the service, suggested a special study of the area from "anthropological, historical and museum standpoints." [192]

The totem pole rehabilitation and duplication project marked a significant resource policy decision for Sitka National Monument. When the park service agreed to plans to duplicate entire poles and then concluded that some of the originals were beyond preservation, it established a lasting ethic of resource management that extended through the next 30 years of Sitka National Monument administration.

| MONUMENT ADMINISTRATION, 1940-1965 |

Investigation Comments

A 1939 investigation of Sitka National Monument by Frank T. Been, Superintendent of Mount McKinley National Park, followed Coffman's 1938 report. Been's comments, based on an August 1939 visit to Sitka, were caustic. According to Been, "Sitka National Monument may be considered antithetical to National Park Service purposes and ideals."

Been noted that the totem poles were foreign to Sitka and recommended their removal to a place approximating their original location. Gravel dredging at the mouth of Indian River by Sitka's Service Transfer Company jarred the scene. It might continue indefinitely unless taken over by the navy. The blockhouse should either be removed or completed. If completed, the block house should be explained to visitors. The Merrill plaque should be removed.

Future work at the monument should include improving the approach to the entrance, constructing toilet and possibly drinking water facilities, building rustic benches, clearing vistas, preparing an information pamphlet for the monument as a whole and signs for each totem pole, erecting a fence to keep cattle out of the grounds, and stabilizing the river bank. Been also recommended investigating the gravel removal, stabilizing the original totem poles and carving duplicates. He criticized past efforts to preserve the poles and commended the current joint Forest Service-Civilian Conservation Corps totem pole project. Some results of past totem pole preservation efforts, according to Been, "have been almost hideous." Canvas had been tacked over decaying portions of poles and painted. All the poles had inserts that had been carved like replaced sections and fitted in to take the place of decayed wood.

Been also expressed concern over preservation of Sitka's historic scene. The scene was fast being despoiled by a salmon boom that had caused more than 1,500 trawlers to headquarter there over the past two years. The service should assist in preservation of Sitka's historical values in order to justify its standards and guardianship. [195]

These recommendations were taken seriously in Washington. Col. John R. White, then acting assistant director of the service, noted in a memorandum on the subject "A good report. Apparently we should either abandon the Sitka Monument or embody it as an historic site and make something worthwhile of it." A few days later Demaray commented that he saw no reason to abandon Sitka National Monument. The emphasis at Sitka should be changed from "totem poles" to the historic aspects of the area. He also noted "but we have had no means to do anything and conditions drift along." The Director of the National Park Service took a more prosaic view: "What we need more than a dignified patrol ranger, is a laborer with sense who will work around the monument, cut the grass and weeds, and paint the poles." The Smithsonian Institution, asked to comment, was of the opinion that poles not appropriate to Sitka should be relocated to Old Kasaan National Monument. Moreover, there were sufficient data in the United States National Museum to reconstruct the more important buildings from Sitka's Russian period. [196]

Sitka's First Trained Custodian

When Ben C. Miller arrived in Sitka in January of 1940 to take up duties as custodian of Sitka National Monument, he faced several challenges. The National Park Service was, for the first time, giving proper attention to Sitka. A totem pole rehabilitation and recarving project, using Forest Service advice and Civilian Conservation Corps workers, was underway. Master planning for the monument was required. Miller also needed to establish his role, and that of the park service personnel who would follow him, in Sitka. Sitka itself was changing dramatically.

Been wrote at the time that the position at Sitka would require more work than one person could do. It would involve totem pole restoration, stream flow control, construction of buildings, and improvement of the approach to the monument. He also recommended that the position be salaried at $2,000 per year. This was the minimum that had been established for Mount McKinley rangers. [197]

Although Been had proposed two candidates for the Sitka position, one a corralman from Mount McKinley and the other the CCC supervisor at Sitka, the position ultimately went to Miller, who also earned Been's recommendation. At the time he applied, Miller was "one of the best district rangers" at Glacier National Park in Montana. He had nine years' experience as a ranger and district ranger. The superintendent of Glacier National Park was reluctant to let him go, but Miller was looking for a duty station that had a high school for his two children. [198] Park Service officials at Washington approved Miller's permanent change of station from Glacier National Park, where he had been a District Ranger, Grade 9, at an annual salary of $2,100, to Sitka, where he would take the title of Custodian, at the same grade and salary. [199]

While Miller's appointment was being settled, overall administration of the monument was being reviewed. When Been queried Washington as to whether or not he would be responsible for supervision and funds of Sitka National Monument, Demaray, Associate Director of the National Park Service, replied that administration of Sitka had been under the Alaska Road Commission. He did not deem it advisable to make a change unless there was a valid reason. [200]

Been's reply indicated that he was somewhat aggrieved. He replied that he had been instructed by Washington to select a custodian for Sitka and therefore inquired if he would have continuing responsibility, possibly as "Coordinating Superintendent." He had never thought of the Alaska Road Commission as having continuing responsibility for Sitka. The road commission had no construction in Southeast Alaska and for it assignment of Sitka and Old Kasaan national monuments had "resulted in an unwelcome responsibility." The fact that the road commission did not want the job was alone sufficient justification for relieving it of administration of Sitka National Monument. Been additionally suggested that those in Washington review the "Report of Investigation of Sitka National Monument" dated October 14, 1939. His rejoinder was effective. He soon received advice that he had responsibility for general administration of Sitka National Monument. [201]

Adequate housing for Sitka's new custodian was among the first issues that Been addressed. Construction workers and military personnel flooding into Sitka were occupying all previous vacancies. What little housing that became available was exorbitant in price. Unfurnished houses rented for as much as $50 per month. The service needed to look into transfer of buildings being vacated by the Coast and Geodetic Survey or new construction to house Miller and his family. Although park officials pursued the transfer and the Coast and Geodetic Survey was agree able, military priorities prevailed and the army eventually took over the land and buildings. [202]

Initial National Monument Planning

The housing problem was one of several indications that the park service needed to plan for Sitka development. In March of 1940, Thomas C. Vint, the service's Chief of Planning, brought Director Cammerer up to date on the planning he had instructed Region IV headquarters in San Francisco to initiate for Sitka. The region had replied that the only available data was a map accompanying the proclamation that had established Sitka National Monument and Been's October 1939 "Report of Inspection of Sitka National Monument." J.D. Coffman, Chief of Forestry, Earl A. Trager, Chief Naturalist, and Ronald F. Lee, Supervisor of Historic Sites, all reviewed the available documentation.

Lee's comments were the most vital and addressed issues of long-term significance:

Since the totems at Sitka are without exception exotic [to the Sitka area], they can be located in the park in accordance with landscape principles or principles of good design. . . . The replica of the old Russian blockhouse has no special historical value since it is not on the original blockhouse site.

There is no need to continue work on this replica; nor, on the other hand, should it be pulled down as someone has proposed. It is an interesting feature and may as well be retained as one of the features of the park.

Lee also noted that the service might employ authority granted by the Historic Sites Act of 1935 as a basis for cooperative agreements for preservation of Saint Michael's Cathedral and other old Russian or early American structures at Sitka. [203]

Vint summarized the comments of Coffman, Lee, and Trager in a memorandum that apparently constituted Sitka National Monument's first master plan. Logical projects for Sitka included a new entrance motif, replacing enameled signs with wood signs, replacing frame benches with benches of rustic design, continuing totem pole restoration, constructing toilet facilities, controlling Indian River erosion, and establishing a custodian's residence and garage, probably in Sitka proper.

Cammerer responded to the Sitka plan by noting that it showed 15 totem poles and there were actually 18. Two additional poles were at the entrance to the park and another was adjacent to Lovers Lane, just south of three poles in a clearing. [204]

Although Vint later noted that he signed a master plan for Sitka on August 30, 1940, and recommended it to the director, there is no documentary evidence that Sitka's first master plan ever evolved beyond the letter summarizing the recommendations of the various branch chiefs. Its recommendations were to be revived, the first time coming in 1946 when Miller again brought up the idea of constructing an information center at the entrance to the monument. [205]

Miller shapes custodian's duties

As the planning went on, Miller began to establish himself in Sitka and his control over Sitka National Monument. After his first full month, February 1940, on the job, he believed that the monument required an additional staff member who could devote his or her full time to researching totem poles and Alaska history. [206] In March of 1940 he plunged into the complex negotiations for acquisition of private property on the park's boundary and recommended acquisitions near the park entrance. [207] Miller also reported the first of many problems with gravel dredging at the mouth of Indian River. Although Miller felt that he had handled the matter badly because the structures for storing accumulated gravel were on park land, Been advised his superiors that Miller had done all that was possible in the circumstances. [208]

In April of 1940 Miller and Deputy U.S. Marshal Henry Bardht apprehended Sitkans Roy Corp and Eva Meinsenzhal for being drunk and disorderly in the monument. Corp and Meinsenzhal were sentenced to 30 days in jail. [209]

Miller also began delving into the history of the monument's resources. He soon felt expert enough to venture corrections for Merle Colby's A Guide to Alaska--last American frontier. Where Colby reported 16 totem poles, there were actually 189 and none were Tlingit poles. Colby was misinformed regarding the block house replica. It contained no logs from any of the original blockhouses. [210]

The new custodian's first few months at Sitka set the pattern for his administrative activities over the next few years, although his administrative duties decreased rather than increased. Miller was extremely active, documenting his monthly reports with photographs that remain of interest. In addition to pictures of monument resources such as the totem poles, discarded poles, the lyre tree, and newly-constructed toilets, he recorded activities such as a May 1941 Kiksadi picnic held "in honor of descendants of warriors killed in battle of 1802 at Old Sitka," women and children picnicking on the seashore, and sailors looking over the grounds. [211]

The annual report for Sitka National Monument for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1941, recorded that CCC workers had moved several trees from the shoulders of the monument road, erected a large rustic sign at the monument entrance, widened the monument road, and resurveyed the monument boundaries. Other projects had not been started because wages paid at the navy construction site limited CCC enrollees. A minor administrative problem was solved when the Bureau of Public Roads agreed to maintain the road in the monument for about $100 annually. Tourist ships were already down to half the number that had visited Sitka in the previous year, and when the army and navy took over large portions of the monument after Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941, visitation to the park dropped to nothing. [212]

World War II

The army takeover came in late May of 1942. Reports of Japanese attacks on the Aleutian Islands, which did not actually occur until early June, prompted the military to pre-empt the monument on the west side of Indian River from the second cross footpath to the mouth of the river. Two pyramid tents were erected by the army, although two aircraft observation posts that had been established near the blockhouse just after Pearl Harbor were dismantled. [213]

A very helpful source of labor for the monument disappeared on July 2, 1942, when the CCC program in Sitka terminated. [214] With much of the labor force on which the monument had depended for several years gone and part of the monument grounds closed, Miller turned outward, rather than becoming inactive. It was not always easy. His monthly report for November 1941 complained, in regard to a photo contest which drew no entrants, "This lack of cooperation and indifference is what I have had to deal with ever since I came here. Apparently one of the greatest obstacles to overcome is the changing of the opinion of the local residents regarding their indifference to tourists." [215]

Miller persevered. He accepted an appointment to the local board of U.S. Civil Service Examiners. He also served as a master sergeant in the Alaska Territorial Guard, a state militia organized to substitute during the war years for the Alaska National Guard, which had been called to federal service in 1940. Miller additionally served on Sitka's local draft board, worked regularly at Sheldon Jackson Museum, and was active in many other community affairs. The Alaska Game Commission and the U.S. Forest Service, neither of which had representatives in Sitka, often called on Miller to accomplish tasks for them. These activities were only supplemental though, to his work in dealing with protection and enhancement of Sitka National Monument's resources. [216]

An important administrative change occurred in 1943 when Miller received a note from Been saying that he was going into the army. Grant H. Pearson became acting superintendent of Mount McKinley National Park, but Miller was advised to report directly to Region IV rather than through Pearson. Thereafter both Sitka and Glacier Bay national monuments came under the general supervision of the Regional Director, Region IV, National Park Service. This diverted some of Miller's attention to Glacier Bay and he began to perform winter patrols there. By 1943, when Region IV director Owen A. Tomlinson planned a visit to Sitka, he advised Miller that he was "Confident you will continue to give your two [emphasis added] areas the personal and intelligent attention you have given in the past. [217]

This dilution of attention to Sitka was followed by a 1944 director's decision that further development at Sitka should be postponed. Archaeological, historical, and scientific values needed to be studied. Until those studies were completed, damage could be repaired but additional development would not begin. Future alternatives might include turning the area over to other agencies such as the City of Sitka or the Territory of Alaska. [218]

As the war wound down, Miller began to report more activity in the monument. Important visitors to the monument in January of 1944 included Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, commander of the Alaska Defense Command, actress Ingrid Bergman, and a party of USO entertainers. [219] About the same time, a problem was cleaned up when the Presbyterian Board of Missions deeded one of the small tracts of land at the monument entrance to the National Park Service. The .4056-acre tract had been donated by a private Native owner, Mrs. William Wells, to the board. This resolved negotiations that began in 1940. [220]

With the war over, Miller received the Selective Service System medal for his work on the local draft board. He also began to report more normal monument usage, although it still had a distinctly military flavor. In May of 1946, Sitka's third and fourth grades held their annual picnic in the monument, the cub scouts held a pack meeting there, and 52 soldiers passing through on a steamer came ashore to visit. [221]

War's end brings a new custodian

Miller left Sitka National Monument about this time. A vacation trip east was followed by unplanned lengthy hospitalization in Vancouver, Washington. As a result, Grant H. Pearson, who had been the acting superintendent of Mount McKinley National Park, took up the Sitka post. Pearson arrived at Sitka after climbing Mount McKinley with the New England Museums Expedition. He reported his arrival for duty on July 1, 1947, and noted that the monument was in good condition considering that it had been without a custodian "since last September." [222]

Pearson was a long-time Alaskan who had first come to the territory in 1925 when he worked for the Alaska Road Commission at Cordova. After moving to Fairbanks, where he worked in the gold mining industry, he was appointed as a park ranger at Mount McKinley National Park. This began a National Park Service career that took him in 1939 from McKinley to Yosemite National Park, where he remained until 1942 when he returned to McKinley. After serving as superintendent at Sitka and Glacier Bay national monuments from 1947 to 1949 he would return to McKinley as superintendent until his 1956 retirement. After retirement, Pearson was elected to the first Alaska State Legislature and subsequently served several terms in both the house and senate. While in the legislature he introduced bills that created a park and recreation program in state government. [223]

When Pearson was reassigned, Ben Miller returned to Sitka in 1947 as superintendent. He held the position until 1949 when relieved by Henry G. Schmidt. Miller, who died in 1953 soon after his reassignment from Sitka, is commemorated by Miller Peak in Glacier Bay National Monument. Schmidt, who had been at Sequoia National Park in California, would leave Sitka in 1953 for the superintendency at Big Bend National Park in Texas and then the Northeast regional directorship.

Abandonment alternative

Park service planners gave renewed attention to Sitka during the unexpected vacancy in the custodian's position. The often repeated suggestions that Sitka should be abandoned were set aside temporarily when a regional committee recommended its retention. The committee suggested that the decision to retain or abandon Sitka National Monument should be postponed until such time as a study could be made of the City of Sitka as a whole to determine the historical values of the area.

Because of Sitka's position as the former capital of Russian Alaska, it is believed that an opportunity may present itself in the future, whereby a series of cooperative agreements may be made to preserve the historical values of that city under the terms of the National Historic Sites Act of 1935. If such is done, the present Sitka National Monument may well be one of the important units of the Sitka National Historic Sites. [224]

Sitka custodian takes up cemetery duties

A time-consuming chore was added to the Sitka custodian's administrative duties when the National Park Service agreed that its Sitka representative would supervise the national cemetery at Sitka. Army plans to abandon the cemetery had brought public protest. Perhaps because of this, the army turned to the National Park Service for help. In November of 1948, the chief of the army's Memorial Division asked if the service's caretaker at Sitka could take over cemetery maintenance. Army officials in Alaska had advised that the caretaker of the "Totem Pole National Park" was willing to help if National Park Service headquarters agreed. [225]

The burial ground consisted of 1.19 acres on which there were 276 internments. Five burials had been made in fiscal year 1948. There were about 100 burial sites remaining in the cemetery. The army wanted someone to raise and lower the flag flying over the cemetery, maintain the grounds, and arrange for opening and closing of graves. The Director of the National Park Service replied that the custodian at Sitka could maintain the cemetery on a reimbursable basis covering costs plus 10% overhead. [226] Miller reported to regional officials that he had taken over the cemetery on June 1, 1949. In return, the park service received the use of an army jeep and 500 gallons of gasoline left at Sitka. [227] This responsibility lasted until 1956. [228]

Alaska Field Committee recommends Sitka development

Administrative activities for Sitka National Monument for the first segment of its middle years, 1940 to 1950, concluded with positive recommendations for its future. The Alaska Field Committee, a federal interagency task force looking at Department of the Interior development in the territory, suggested construction of a new museum/headquarters building. The structure should include the superintendent's office, public comfort stations, work and store rooms, and museum rooms "for display of the Sheldon Jackson Collection of artifacts to be donated to the National Park Service." Other work recommended for Sitka included a superintendent's residence and utility building and erosion control work on Indian River. [229]

The first step toward implementing these recommendations was taken when Miller once again had to raise the issue of a housing problem. By April of 1949 there was again a housing crunch at Sitka. Also again, Miller suggested that the National Park Service obtain the Coast and Geodetic Survey property he had been coveting in 1940. This met with service approval, and the Bureau of Land Management transferred the 1.25 acre tract to the National Park Service. [230]

Second segment of middle years

The second segment, 1950 to 1965, of Sitka National Monument's middle years began quietly. Visitation to the monument was down. Steamers calling at Sitka arrived and departed in the night and most tourists did not have a chance to see the Indian River park. [231] This situation was aggravated in 1954 when Alaska Steamship ended passenger service to Alaska. The most exciting developments were in looks to the future. Planning for the monument's future continued, while perennial problems such as erosion control and totem pole preservation continued.

Planning continues

A 1953 review of the situation at Sitka adopted and expanded the 1949 recommendations of the Alaska Field Committee. The review again called for a headquarters building and public comfort stations in the monument and for Indian River erosion control. It went beyond the 1949 plan to suggest a picnic area and more interpretive markers. Also beyond the 1949 plan was an initiative that proposed Sitka as the National Park Service's center for interpreting all Indian and Russian history and archeology in Southeast Alaska. To do this, the service needed to build a museum at and promote Sitka. [232]

Plans for "Mission 66," a service-wide effort to renew the nation's national parks and monuments in time for celebration of the 50th anniversary of the founding of the National Park Service, followed the 1953 recommendations for Sitka. The Mission 66 program endorsed most of the 1953 plans and defined the monument. Sitka National Monument commemorates the bravery and culture of Alaska's Indians. Visitors could "enjoy the rare experience of reaching the heart of an unspoiled stand of towering Sitka Spruce and Western Hemlock with dense undergrowth...." [233]

The final planning effort of the 1950s, a 1959 master plan, reversed a de-emphasis on Russian activities at Sitka. Regional officials commented that the plan changed the approved description of values. "It was only a short time ago that upon direction of the Washington office, we rewrote the Sitka folder and prepared the Mission 66 prospectus to minimize the Russian story." The new plan gave principal emphasis to the Battle of 1804 and subsequent Russian-American history of Alaska rather than to the Indian culture of Alaska and the effects of European contact on it. The totem poles were treated as only incidental to area interpretation. [234]

Boundaries and vistas

While the planning was underway, adjustments were made to the western park boundaries as the private properties at the entrance were acquired. [235]

A major improvement to the seaward vista from the park occurred in 1954, when Superintendent Henry G. Schmidt was able to advise regional officials that the Sitka Utilities Board had funded relocation of the transmission lines along the beach. New lines would parallel the Sawmill Creek Road. [236]

Superintendent's position moves to Juneau

As the 1950s had ended, the superintendent's position was relocated to Juneau, a situation that would remain in effect until the early 1970s. Various reasons have been cited for this arrangement. The move may have been made because one of the superintendents liked the political hustle-bustle of the territorial capital. [237] Or, the move may have been made simply be cause changing transportation patterns made Glacier Bay and Sitka jointly more accessible from Juneau. A park historian was appointed to be in charge at Sitka. Seasonal historians assisted there. A park ranger staffed Glacier Bay.

Visitation and use

The park historian at Sitka, George A. Hall, a graduate of Drake University, had worked with the Public Health Service on Japonski Island. In 1957 he transferred to Sitka National Monument, where he would remain until 1963. After leaving Sitka, he would go on to serve as assistant chief of the park service's National Memorials Branch in the National Capital Region in Washington, D.C. lie later returned to Alaska as superintendent of Mount McKinley National Park and Katmai National Monument. [238]

Hall observed that 1958 was the first year in which annual visitation to the monument had reached the peak attained before passenger steamer service to Sitka was ended in 1954. He attributed this to changing transportation patterns, with more travelers going by air, to the transient population brought to Sitka as a result of pulp mill construction, and to an increasing habit of Sitka families to use the monument for recreational purposes. Tourists arrived between 9 a.m. and 3 p.m., and transient workers used the park in the evenings. Special events also in creased park usage, with 1959 seeing Sitka conventions for the Alaska Lions Club, Business and Professional Women, Protestant Chaplains of Alaska, and the Southeastern Camporee of the Boy Scouts of America. Most conventioneers visited the monument, and the scouts camped on the grounds. [239]

Noteworthy events in this period included the June 1958 appearance of Time and Life magazine staffers to photograph totem poles for a forthcoming article and Lowell Thomas' visit to the monument to film a portion of his "High Adventure" television program. [240]

The end of the 1950s also saw the Sitka Historical Society, established in 1955, hold a commemorative tea on April 5, 1959, to celebrate the establishment of Sitka National Monument. [241] Hall served as president of the historical society, a reflection of strong park service involvement in community affairs. This continued the tradition begun by Ben C. Miller in the 1940s. Hall was also active on the Sitka Historic Sites Restoration Committee, which was working on restoration of Saint Michael's Cathedral. [242]

A blight on the monument authorized by special use permit was removed when the asphalt hot plant of the Morrison-Knudsen Company, installed on the east bank of Indian River to provide material for the paving of Sitka's streets, was finally removed. Surplus asphalt and debris from the plant were buried on the site, which was later reforested. [243]

The stage was set for final acquisition of the last private property on the east side of the road at the park entrance when Esther Littlefield agreed to sell her house, which was one of the three sitting on the hill at the entrance to the park. The service, however, did not take an option to purchase the property until March of 1963. [244]

Planning for the monument continued as the draft of chapter 1 of volume 1 of a new master plan for Sitka went to the regional office for review and comment in April of 1960. The plans at this time incorporated Mission 66 recommendations for a visitor center. Concurrent with master planning, park personnel initiated detailed exhibit planning and drew upon the assistance of the service's Western Regional Office and Western Museum Laboratory. [245]

Park personnel changes

Hall, who had been the first person in charge of Sitka National Monument to be classified as an historian, left in 1963 for an assignment in Washington, D.C. His initial replacement, Charles W. Warner, reported for duty on July 1, 1963. He had previously served at Colonial National Historical Park in Virginia. Warner remained at Sitka only until October 2 of that year when he was asked to resign. Romaine Hardcastle, a Sitkan who had been assisting at the park as a "gratuitous worker," took over as the National Park Service representative in Sitka until a new park historian could arrive. [246]

While Hardcastle was serving in an acting capacity, arrangements were made to ship three of the poles at Sitka National Monument to New York for display at the 1964 World's Fair. Two of the poles were taken from where they stood at the entrance to Lovers' Lane while a third pole ("No. 12") was taken from near the end of the lane. The poles, which would be returned to Sitka in 1966 and emplanted at the entrance to the park, were loaded on a steamer on March 11,1963, and shipped to New York. [247]

About the time the poles went off to the World's Fair, William T. Ingersoll, an experienced park historian with a master's degree in history from Columbia University, arrived at Sitka to begin duty as park historian. Hardcastle, who later received a cash incentive award for her outstanding work during the time the monument was without a historian, continued in the service as a museum aide and technician until 1967. [248]

Park personnel in this period were busy preparing for the new visitor center, which would soon be dedicated. Funding for the center had been repeatedly requested in monument budgets, but money was only obtained after a visit to Sitka by National Park Service Associate Director Elvind T. Scoyen in 1961. Monument officials briefed Scoyen on the need for a visitor center and the possibility of cooperation with the Board of Indian Arts and Crafts. After Scoyen returned to Washington a cooperative funding arrangement that would provide for a visitor center at Sitka was worked out between the two agencies. [249]

The Littlefield house, which stood near the entrance to the monument and had been acquired on August 23, 1963, was burned by the Sitka Fire Department in June of 1964. Sitka personnel applied for and received financial assistance from the Mount McKinley National History Association for publication of a booklet about Sitka National Monument that could be sold to visitors. [250]

With the Littlefield house gone, the grounds overlooking the new visitor center were spruced up. Chief Saanaheit's pole and four house posts were emplanted at the monument entrance. The latter were set on the elevated ground overlooking the entrance. The interior of the center was enhanced by seven house posts and a house front loaned by Sitkans to the National Park Service for display. [251]

The posts were in place just in time for ceremonies held in connection with dedication of the visitor center on August 14, 1965. National Park Service Regional Director Edward A. Hummel delivered the dedication address, which was attended by a large number of Sitkans and visiting dignitaries that included Susan Barrow, Curator of the Alaska Historical Library and Museum; Dr. Frederick J. Dockstader, Director, Museum of the American Indian and Chair of the Indian Arts and Crafts Board; Mathilda Gambel of Angoon, joint lender with Sitka's Patrick Paul of the wolf house posts installed in the lobby; and Robert G. Hart, general manager of the Indian Arts and Crafts Board. [252]

| RESOURCE ISSUES, 1940--1965 |

The period 1940 to 1965 began with bright promise, as the National Park Service devoted new attention to Sitka National Monument's resources, and then became a frustrating time as resource preservation had to be weighed in the balance with national defense needs.

Development ideas

Part of the bright promise came from desires to expand and enhance the monument's resources. Miller, although not trained as an historian, began a research program and turned up an original transfer map (showing Sitka properties transferred from the Russian to American governments in 1867) and a typewritten inventory in records of the U.S. Commissioner at Sitka. He also supplemented his monthly narrative reports with photographs of resources in Sitka National Monument and historic sites in Sitka proper.

Been, who said in 1939 that the monument was "antithetical" to National Park Service purposes, in 1940 endorsed Miller's recommendation that the service assume jurisdiction over Castle Hill. He also suggested a project to salvage the wreck of Neva, a Russian American Company ship that foundered near Sitka in 1813. A local diver with his own equipment was available in Sitka for about $40 per hour and might be hired as a skilled workman by the CCC. He also advised "There is probably no immediate responsibility of the Service toward historical values in Alaska of greater importance than acquisition and protection of St. Michael's Cathedral." A year later, Been again discussed acquisition of St. Michael's and added the old Russian cemetery to his list of Sitka properties important to the park service. In 1942, Been concluded that the National Park Service should preserve the Russian Orphanage. [253]

Regional officials and national officials of the service, as well, took a new interest in Sitka's historical significance and encouraged their Alaskan representatives to identify and document its physical manifestations. The Region IV historian outlined areas of significance that Miller could investigate and Miller's immediate supervisor, Been, encouraged him to prepare a historical development plan for Sitka.

The Washington-based Supervisor of Historic Sites commented that the proposal to acquire Castle Hill had merit and suggested that Miller should provide a map and explanatory data showing the relationship of the hill to Sitka National Monument and also show any other historic sites in the vicinity. Miller even arranged for Lynn A. Forest, at the time a U.S. Forest Service architect at Juneau, to come to Sitka and take measurements and photographs necessary to make documentary drawings of Saint Michael's Cathedral. [254]

A tangible sign of the renewed interest came in April of 1940 when construction began on two pit toilets, the first sanitary facilities in Sitka National Monument. Construction and purchase of a building for an office and modern toilets at the entrance to the monument was approved somewhat later. [255]

There was also interest in acquiring houses on the east side of the road that passed by the monument entrance. Three of the houses sat on the elevated area that later overlooked the visitor center built in the 1960s, while two others lined the road to the north. [256]

Totem pole preservation

Concurrent with the expanded interest was a feeling that the totem pole preservation problem had finally been brought under control. Early in 1940, B. Frank Heintzleman, Regional Forester for the U.S. Forest Service, was able to advise the National Park Service that the Sitka totem pole work begun in 1939 was almost done. All "sixteen" poles had been restored, treated with preservative, and reset in their former locations. As required in the National Park Service approval to go ahead with the work using CCC crews, a photo record had been made of all poles before work was begun. [257]

Successful completion of the CCC totem pole project left the originals of newly recarved poles lying on the monument grounds exposed to the weather. When Mrs. Robbins (first name unknown), the wife of an officer assigned to Sitka Naval Air Station, suggested that the discarded originals might be protected there, protracted correspondence ensued. She thought the poles could be housed in the station's recreation building. Comdr. J.R. Tate, commanding officer of the station, followed up her spoken comments with a letter to Been. He offered to house the poles in the corners of the navy gymnasium. [258]

Pole preservation remained a continuing problem. Pressure treatment, which appeared to be the most effective means of preservation, was difficult with such large objects in any case and almost impossible in a remote location such as Sitka. One alternative, suggested by a park service engineer, was to cut the poles into manageable lengths so that they could be treated at Sitka. This would eliminate the necessity of shipping them in tact to the West Coast where it was possible to treat them in their original size. [259]

Been agreed that moving the original poles to Japonski Island was a good idea. Demaray, temporarily acting Director of the National Park Service, responded that the poles "have no proper place at Sitka National Monument...." He preferred, however, that they be offered to the Territorial Museum at Juneau. When the museum declined to accept the discarded originals, Demaray approved their relocation to the naval air station. [260]

Although he finally had approval to move the discarded originals, Miller foresaw difficulties. He requested permission to destroy poles that he believed too rotten to preserve. He would salvage those figures from the poles that could be re stored. Been endorsed Miller's request, but it provoked a quick refusal from Washington. "Original specimens always have scientific value which duplicates . . . could not possess . . . . they are not to be destroyed as surplus." After this, the discarded original poles were moved. When Been reported on his next visit to Sitka, made on an inspection trip to Glacier Bay and Sitka between August 12 and September 4, 1942, he was able to record that the poles "have been nicely utilized by the navy." Restored sections of the poles stood at entrances to the air station's administration and recreation buildings. Several sections had also been placed inside the recreation building. [261]

Discarded original poles came up again in 1947, when Grant H. Pearson had succeeded Miller as the custodian at Sitka. By that time the navy had turned its Japonski Island facilities over to the Alaska Native Service (ANS). ANS operated them as Mount Edgecumbe boarding school for Alaska Native children. One of the school's staff, George W. Fedoroff, advised Pearson that a former navy building would be converted to a museum. He suggested that discarded original poles not moved in 1942 could be housed in the museum. This received National Park Service approval and on November 21-22, 1947, Mount Edgecumbe officials took delivery of the remaining old poles from Sitka National Monument. [262] After this, as Mount Edgecumbe officials came and went, some parts of the old poles were taken for souvenirs and other parts were discarded and burned in Sitka's dump. George Hall retrieved the last full pole in 1961 and placed it at Sheldon Jackson Museum. [263]

Other than routine maintenance, no new major projects were taken in connection with Sitka National Monument's totem poles until the 1970s.

Gravel operations

The private gravel operations at the mouth of Indian River be- came a major problem when Navy contractors took over the former Sitka Transfer company operations. The boundary was not clearly defined and the contractors built gravel bunkers on what turned out to be National Park Service land to the east of Indian River. Navy plans to build a flume were dropped when Miller told them park service permission would be required. Miller optimistically concluded this first report by commenting that the dredging should benefit the park by preventing further erosion of the west bank of Indian River. [264]

The contractors soon wanted more gravel than the outwash at the mouth of the river could supply. The service's immediate response was cautious. It stood ready to aid national defense, but the navy could take Indian River gravel only after showing that no other source was available. No monument land was to be transferred to the navy. Gravel was to be taken only from the river bed, an island at the mouth of the river was to be left intact, removal was to be conducted in such a manner that no harm would result to the natural beauty of the monument, and after the supply of gravel was exhausted the retaining wall along the river bank was to be repaired. [265] No other source was available, and navy gravel removal continued throughout the year. [266]

On the ground activities took a different turn, and as early as June of 1941 Miller had to stop the navy contractors from cutting the trees on the island in the mouth of Indian River. After an October 1941 flood destroyed a strip of river bank about 600 feet long and 6 to 40 feet wide, Miller blamed the destruction on the dredging. It had resulted in a pit at the river mouth 800 feet long, 30 to 200 feet wide, and 4 to 30 feet deep. This, in Miller's opinion, had caused the material in the river bed to wash into the pit during the flood. As a result, the river bank slid into the water, carrying its cribbing with it. He believed that further erosion would occur so long as the navy was permitted to mine for gravel in Indian River. [267]

Park service sensibilities about the monument's values took a back seat to the war effort after December 7, 1941. Officials authorized the navy to take gravel from the wooded island at the mouth of Indian River as well as from the river bed. The expanded operations, they believed, would detract from the charm of the monument's footpath, but not be destructive to the main portion of the monument. [268]

The gravel operations turned out to be plagued with problems and destructive of park values. On September 18 and 19, 1942, a flood rampaged down Indian River. Gravel removal that steepened Indian River's gradient in its lower reaches may have increased the flood's intensity. The torrent tore out both Indian River bridges. It also washed away 200 feet of road, 250 feet of trail, and 10 to 50 feet of river bank on either side. Two army men, whose first names are unknown, Sgt. Riley and Pvt. Westfall, who had been on the footbridge when it washed away, were drowned. They were part of the army detail guarding the navy gravel operation. A sailor, Frank Smith, was also washed off the bridge but survived by clinging to one of the downed bridge's cables. The waters swept away a totem pole that stood near the footbridge, but the navy later recovered it in the bay and returned it to the monument. At the same time, it destroyed a portion of the pipeline that took water from Indian River to the navy and city water reservoir. [269]

The navy contractors threw a temporary bridge across Indian River, but fire followed the flood. On November 11, 1942, an army guard attempting to light a lantern started a fire that destroyed an office building and repair shop at the gravel bunkers. Some progress was made because a new road, to replace the old one being destroyed by dredging, was almost completed in the same month. [270]

In March of 1943 sailors from a naval construction battalion (Seabees) took over operation of the Indian River gravel plant. [271]

At one point, this encroachment was seen to benefit the park. The dredging would form a small lagoon that might add to park values and, as a quid pro quo, the navy agreed to widen the entrance to the monument. This would provide adequate space for parking and turnaround. [272]

Construction on Japonski Island was almost completed by 1944 and the need for Indian River gravel diminished. The army cooperatively restored its area of the monument to as natural a state as possible.

Miller began negotiating with the navy for its share of the restoration work. V.S. Carrier, Resident Officer in Charge, at the Naval Air Station, Sitka, submitted a report to the Navy's Bureau of Yards and Docks detailing the damage that had been done by the gravel operation. He proposed measures that might be instituted to partially rectify it. Photographs made by Miller in 1941 documented the report. Carrier concluded that dredging deep holes at the mouth of the river had caused an increased stream velocity. This gradually cut back the river bed. The change in the river bed in turn had cut back the river banks, which had caused a reverse curvature in the river. Cutting action in the vicinity of the footbridge resulted, causing the bridge to collapse.

Carrier recommended that the navy remove its bunkers and re lated buildings, allowing the City of Sitka to salvage the lumber. The river channel should be restored to its original course. Gravel acquired in the course of changing the course of the river should be used to prevent the river from redirecting itself into its old channel. Logs and stumps which could not be burned on site should be placed in one of the dredging holes and covered with gravel. Additional gravel and debris accumulated on site should be leveled out. The north bank of Indian River should be dressed to prevent under wash. While log cribbing should be built to prevent further bank erosion, Carrier recoin mended that the navy not replace the suspension bridge washed out in the 1942 flood. [273]

Carrier's letter brought Rear Adm. Carl A. Trexel, Director of the Alaska Division, Bureau of Yards and Docks, to Sitka National Monument in March of 1945. He agreed to Carrier's recommendations. Park service concurrence followed, with a commendation for Miller and Carrier for their cooperative work. By April of 1945 the navy had razed its gravel bunkers and all but one of the shacks used in dredging operations. Work was also begun on erosion-control cribbing along the banks of Indian River. More than 600 feet of log cribbing was in place by August of 1945, only to be washed out in a September flood. This left the problem, which was to continue, but active dredging was not to resume for several years. [274]

Gravel problems

Gravel removal at the mouth of Indian River resumed and continued intermittently through the 1950s. An unknown amount was removed by a private party in 1951, the Bureau of Land Management sold an additional 20,000 cubic yards of gravel in 1957, the Public Health Service removed 40,000 cubic yards in 1958; and, after the State of Alaska assumed jurisdiction over tidelands in 1959, its Department of Public Works removed 100,000 yards of gravel and 20,000 more cubic yards were sold to private parties. The continued sales undermined many of the monument's values and its superintendent recommended no further investment at Sitka until the National Park Service controlled the tidelands adjacent to the monument. [275]

A peripherally related gravel issue arose in 1958 when the Alaska Lumber and Pulp Company obtained permission to divert Indian River water to wash gravel needed for pulp mill construction. Monument officials objected to this withdrawal as it could dry up Indian River and Fish and Wildlife Service officials consented only if diversion operations would be suspended in times of low water. [276]

State officials aggravated the gravel situation in 1960 when they issued permits for removal of 140,000 cubic yards of material adjacent to the mouth of Indian River. The National Park Service, although the adjacent upland owner, was not consulted about the permits which were valid until 1969. [277] The state subsequently decided that it would issue no new permits for removal of gravel at the mouth of Indian River. Several state permits remained in effect, as did a few old permits issued by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. There was continuing pressure for new leases. [278]

The gravel situation at Sitka became critical in 1964 when the State of Alaska received federal funding to construct an airport on Japonski Island. Engineers estimated that the construction would require one million cubic yards of gravel. The tidelands off Sitka National Monument were the most likely source of such material. Although the National Park Service had been trying to obtain control of the tidelands for several years, it had been unable to do so. There was no funding for the cadastral survey required before the federal government could lease the tidelands, which had passed to the state and in part to the City of Sitka under provisions of the Alaska Statehood Act. The situation was aggravated because the City of Sitka, a primary user of the gravel, now controlled some of the tidelands. [279]

Almost 10 years passed after the 1945 floods washed out the navy's contribution to Indian River erosion control before a new major project was undertaken. A major flood in 1960, as violent as those of the early 1940s, caused monument personnel to fear that future floods might do irreparable damage. [280] It also seemed timely to try some flood control work because the State of Alaska had finally agreed to discontinue gravel operations at the mouth of Indian River.

The new plan to prevent Indian River from washing away Sitka National Monument involved digging a channel approximately 800 feet long from the river mouth to mid-monument, diverting the river from its then existing course to the new channel with rock rip-rap, and rebuilding eroded banks with the gravel obtained in the course of digging the new channel. The plan was implemented in July of 1961 after approval of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game had been obtained. A long spell of dry weather facilitated implementation by causing the river level to be extremely low.

When the dry weather ended on August 11, 1961, Sitka had 9 1/2 inches of rain in 36 hours. This caused Indian River to rise about five feet and to divert itself into the new channel. The new channeling and rip-rap protected the monument from what could have been an even more serious erosion problem, although several feet of the lower end of the rip-rap fell into the channel and had to be replaced after the waters subsided.

This early 1960s effort to control Indian River erosion ended with recognition that an additional 20 to 40 feet of gravel fill would need to be placed behind the rip-rap if it were to survive. [281]

Tlingit fort site and blockhouse replica

Two other resource issues overshadowed the gravel issue in the late 1950s. These issues were the archeological verification of the Tlingit fort site and the razing of the blockhouse replica constructed in the park in 1927.

Archaeological investigation of the fort site came in 1958 after service officials concluded that unless the site could be archeologically verified, retention of Sitka National Monument in the national park system could not be justified. University of Alaska archeologist Frederick Hadleigh West arrived and conducted test excavations but could not find any remains. Then Alex Andrews, a Sitka Tlingit, was consulted and pointed out the site. Once oriented, West was able to interpret surface features that included house pits and outlines of the palisade that had en circled the fort. Artifacts recovered were removed to the University of Alaska at Fairbanks for study before being returned to the National Park Service. While in Sitka, West also excavated at the Russian sailors' memorial, and found no evidence of burials there. [282]

Razing of the blockhouse created a storm of protest. In the view of park officials, the blockhouse had become an attractive nuisance. Left open, it was vandalized by graffiti and sometimes used as a convenient substitute for the toilets at the park entrance. Sealed up, it invited forcible entry. Somewhat deteriorated, it was also a potential hazard to visitors. Visiting National Park Service officials made a habit of objecting to its presence on monument grounds.

On July 21, 1959, when Hall saw a tractor working across Indian River, he arranged for the operator of the tractor to pull down the blockhouse after receiving telephone approval from his superior at Juneau. Remains of the collapsed structure were then bulldozed further onto the beach and burned.

While, given what later proved to be Sitkans' affection for the old blockhouse, its destruction would have become a cause for controversy in any case, coincidence directed immediate public attention to the matter. Passing students observed the burning pile of debris on the beach, interpreted the octagonal framework rising above the pile to be remnants of a helicopter, and alerted the Sitka fire department.

The upshot of the coincidence was that a large segment of Sitka's population, the fire department, and a photographer for the local newspaper arrived for the end of the replica blockhouse which had been erected through community efforts in the 1920s. Sitka erupted with protests that reached the Secretary of the Interior, but satisfactory amends were not made until the 1960s. [283]

The blockhouse controversy continued throughout 1959 and into 1960. In February of 1960, Dr. John Hussey, San Francisco-based historian for the National Park Service's Western Region (the old Region IV), and Sitka and Glacier Bay National Monument Superintendent Leone J. Mitchell met with the Sitka Chamber of Commerce on the subject. This followed a January 29 session at which chamber members blistered Hall for his role in the destruction of the blockhouse. [284]

Sitka's ire over the blockhouse issue was ultimately calmed by a National Park Service promise to construct a new replica block house. Known as the Blockhouse C reconstruction, the replica was built in downtown Sitka in the old Russian cemetery between Kogwonton and Marine streets. Plans for the replica were prepared using records available at Sitka and a contract was let. On September 19, 1961, National Park Service architect Robert Gann arrived to supervise the construction. [285]

The blockhouse issue continued to cause problems after completion of the replica. The new replica was of octagonal shape, like the 1926 replica of blockhouse D which it was designed to replace. It was located within a few feet of the spot on which Russian blockhouse C had once stood, but blockhouse C had been square in design. The new replica would later be criticized as being of the wrong design for its location. Its situation was further complicated because the blockhouse sat on land managed by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. All of the difficulties would continue to make the blockhouse a complex problem as Sitka National Monument evolved through the 1960s, 1970s, and into the 1980s.

Preservation Professionalism and Sitka

National Park Service efforts to deal with the blockhouse issues at Sitka, and indeed with other archeological and historical issues at Sitka reflected the growth of preservation expertise in the service as a whole.

It was only in 1931 that the service was able to add its first professional historian to the staff despite the personal interest of leaders such as Albright and Mather in history and historic sites. This came in the midst of efforts to transfer cultural parks managed by other federal agencies to the National Park Service and only four years after restoration efforts began at what was to become Colonial Williamsburg. [286] On the heels of these essentially internal developments came the infusion of expertise provided by park service administration Civilian Conservation Corps work forces that preserved and developed historic sites and of the Historic American Buildings Survey.i [287]

This increasing staff expertise about historic sites probably influenced Frank T. Been's 1939 comments on Sitka's "antithetical" relationship to National Park Service purposes. It certainly made it possible for Ben C. Miller to seek advice from regional historians about the historical studies he was encouraged to undertake and resulted in recognition by senior service officials such as Ronald F. Lee and O.A. Tomlinson of the historical values in Sitka that lay outside monument boundaries.

The results of this evolution of events at Sitka National Monument were reflected in efforts to systematically define Sitka's interpretive focus, the injunction from Washington to preserve the original totem poles for which replicas were being created, the appointment of historians to the staff at Sitka, and in creased use of contractors and regional office professionals in solving monument problems The blockhouse reconstruction and later events demonstrated the difficulty, however, of adequately controlling such projects from afar.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

sitk/adhi/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 04-Nov-2000