|

Springfield Armory National Historic Site Massachusetts |

|

NPS photo | |

The U.S. Manufactory of Arms

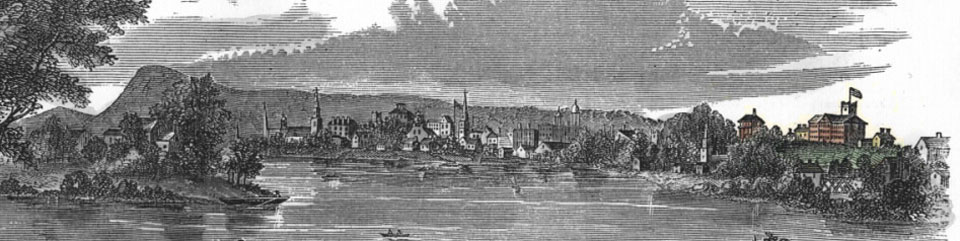

In 1777 the United States was only a year old, and still fighting for its independence. The early battles of the war in the northern States had shown the need for a place to store weapons and ammunition safe from the British, centrally located, and within easy reach of American troops. Gen. George Washington and his Chief of Artillery, Col. Henry Knox, chose this hill above the Connecticut River as the site of the first United States arsenal. Over the next 190 years this warehouse for muskets grew into one of the most important facilities for the design, development and production of military small arms in the world.

Although Springfield was still only a small, struggling village, its geographical advantages were obvious. The town was located at the intersection of major highways and the Connecticut River but far enough upstream to be safe from enemy attack. Supplies, skilled manpower, and adequate waterpower for manufacturing were all close at hand. No wonder Knox concluded that "the plain just above Springfield is perhaps one of the most proper spots on every account" for the location of an arsenal.

During the Revolution the arsenal stored muskets, cannon, and other weapons and produced paper cartridges. Barracks, shops, storehouses, and a magazine were built, but no arms were manufactured. After the war the government kept the facility to store arms for future needs.

In 1787 the arsenal was the center of one of the key events leading to the adoption of the Federal Constitution. Poor farmers from western Massachusetts, led by Daniel Shays, tried to seize the arms at Springfield. They planned to use the weapons to force the closure of the State and county courts that were taking their lands for debt. Confronted by the cannon of an organized state militia, they failed in their desperate attempt. Yet the incident led many of the wealthier people, who feared for their property at the hands of an armed rabble, to vote for the new Federal Constitution and support a stronger central government.

In 1794 the new Federal government decided to manufacture its own muskets so that the Nation would not be dependent on foreign arms. President Washington selected Springfield as the site of one of the two Federal armories. New buildings were erected. The West Arsenal, the oldest surviving building, was completed in 1808 and the Main Arsenal Building, in 1847. By then the armory grounds had taken on an orderly, symmetrical appearance that in part remains today. Around a landscaped green there were clustered storage buildings, blacksmith shops, and administrative offices. The attractive setting encouraged the development of fine residential neighborhoods in the vicinity. A mile away on Mill River three shops were built to house the heavy operations that required water power. In 1857 the Lower and Middle Water Shops were sold and their activities concentrated in the Upper Water Shop, the site of the modern Water Shops complex.

Springfield Armory soon became a center for invention and development. In 1819 Thomas Blanchard developed a special lathe that easily turned out identical gun stocks. In the 1840s the old flintlock gave way to a percussion ignition system that increased the reliability and simplicity of long arms. Soon after the Civil War Master Armorer Erskine Allin introduced the "Allin Conversion," which incorporated the far more advanced design of breech-loading into now-obsolete muzzle-loaders, thereby extending their service life. It was also here that the famous 1873 "Trapdoor" Springfield Rifle, the Model 1903 of World War I, and the M-1 Garand, known to millions of servicemen in two wars, were produced. The last small arm developed by the armory was the M-14, a rifle so effective that it replaced four other military small arms.

In the 1890s a new function was assigned the armory. It became the Army's main laboratory for the development and testing of new small arms. After World War II this became the center's primary responsibility. By the time of the Vietnam conflict Springfield Armory developed not only rifles but also machine guns for ground and air use, grenade launchers, and associated equipment. Many weapons were not manufactured at the armory, but plans and specifications were drawn up for the use of private contractors who built them elsewhere.

In 1968, in a controversial economy measure, the Defense Department closed the installation. For almost two centuries the hilltop overlooking the Connecticut River had been an important place for the development and manufacture of arms for the American solider. The facility evolved from a place where skilled craftsmen built, piece by piece, one musket at a time, into a center pioneering in mass-production techniques, and finally into an institute famous for its research and development.

Blanchard's Lathe

Thomas Blanchard worked at Springfield Armory for 5 years. The lathe he invented revolutionized technology, but it was not his only contribution to industry. He also invented an apple parer, machines to mass produce tacks, one to cut and fold envelopes, and a method for bending large timbers.His fame, however, rests on the lathe that visitors can still see at Springfield. With it a workman could quickly and easily turn out identical irregular shapes. The large drum turned two wheels: a friction wheel that followed the contours of the iron pattern, and the cutting wheel that imitated the movements of the friction wheel to make an exact replica of the pattern in wood.

What is an Armory?

The words armory, arsenal, and magazine are often used interchangeably, but in the 18th century the terms had specific meanings. An armory was a place where arms were manufactured, an arsenal was a place for storing the accouterments of war, and a magazine was a storehouse for powder and ammunition. Springfield Armory served all of these functions.Garand and the M-1

As a boy John C. Garand patented a telescopic screw jack and a machine for automatically winding the bobbins used in cotton mills. In 1919, when he was 20, he came to Springfield, where he worked to develop a semi-automatic rifle.Over the next five years many designs were submitted for the rifle, but none met the army's rigid specifications. In 1924, Garand offered a design that was approved for further testing. This was the famous M-1.

The army adopted the rifle in 1936, and production began the next year. The Marine Corps adopted the rifle in 1940. Gen. George Patton said, "I consider the M-1 the greatest weapon ever made."

Model 1795 Musket

The first weapon produced at Springfield was a copy of the French "Charleville," a musket popular with Americans during the Revolution.Model 1903 Rifle

This bolt-action rifle was used by American troops in World War I. It is still considered one of the most accurate rifles ever made.M-1 Rifle

This semiautomatic rifle was an original Springfield development. In 20 years over 4 1/2 million copies of this fine weapon were made at the Armory.

Crafting the 1861 Rifle Musket

Although the percussion rifle musket was manufactured for less than 20 years, it became one of the most widely used weapons of modern times. The percussion lock first appeared in 1837 when some older flintlocks were modified to use the new system. The first percussion rifles were produced at Springfield in 1855. They saw use in nearly every battle of the Civil War, from Fort Sumter to Appomattox. In the American West they protected laborers building the Union Pacific Railroad from the Indians, and were used by Sioux Indians to defeat Gen. George A. Custer in the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876. From 1855 to 1865, when the last percussion rifles were manufactured at Springfield, three official models were produced. There was little difference between them; the Model 1861 represents only one that was widely used during the Civil War.

Building a rifle musket combined the skills of master craftsmen and the techniques of mass production. Some 400 separate operations were needed to make the 50 parts of one 1861 rifle. While the weapon itself was not complicated, each part had to be made to very fine tolerances so that it could fit any rifle of the same model. To make parts that were exact duplicates required standard gauges and patterns and precision manufacturing.

About a mile from the armory Hill Shops were the Water Shops on Mill River where much of the heavy manufacturing operations were performed with the aid of water power. Here the barrels were made. The barrel was the most difficult and complicated part of the rifle to make. It began as a flat piece of iron, called a "skelp," some 3 inches wide and 2 feet long, and ended as a round, slightly tapering tube about 3½ feet in length. The skelp was first rolled into a tube around a solid rod of iron. The rod helped the tube keep its cylindrical shape as the seam, where the two edges joined together, was welded. This was done by alternately heating the iron then hammering it on a specially shaped anvil. This water-driven hammer repeatedly struck the white-hot metal. When the tube was completely welded, the inside of the barrel was bored to the correct diameter, and then the barrel was rifled to give the weapon greater accuracy. In this operation spiral grooves—rifling—were cut inside the tube so that the bullet was forced to spin when fired and fly true to the target. The barrel was then checked to make certain that it was absolutely straight. This was done by sighting through the barrel at a line inscribed on a mirror and then striking the outside of the barrel with a lead hammer until the reflected line appeared straight. The barrel was finished by grinding it to the proper taper and polishing the outside.

The wood stocks, made from well-seasoned black walnut, were also made in the Water Shop. Before the war a four-year supply of wood was stored at the armory. The stocks were first shaped on an improved version of the lathe invented by Thomas Blanchard. Then the grooves and recesses for the barrel, lock, and trigger assembly had to be cut into it. These were cut on a planing machine guided by patterns so that all stocks were alike.

While the barrel and stocks were being made, the other parts were moving along the assembly line at the armory. In the blacksmith shop the ramrods, the many small pieces of the lock mechanisms and trigger assemblies, and the innumerable bands, springs, screws, and swivels were forged. Steel dies, called "swedges" were used to shape the parts. The swedges were made in pairs. To make a part, one section of a swedge was placed in an anvil. A piece of hot iron was placed on top and the second section placed over the iron. The swedges were then hammered and the iron forced to shape in the swedge. When the iron cooled, the part was finished on a lathe, a milling machine, or by hand with files. If the job was done skillfully, the part would be identical with other parts of the same kind and interchangeable between muskets.

Each musket was equipped with a bayonet, and these too were produced at the Springfield Armory. Bayonets were forged and polished to the same exacting standards as the rifle parts.

At its peak during the Civil War, Springfield Armory employed 3,400 persons who, in 1864, produced 1,000 muskets each 20-hour working day.

Quality Control

From 1795, when the first muskets were manufactured at Springfield Armory, to 1968, when the facility was closed, the employees of Springfield Armory took pride in the quality of the weapons they produced. They maintained standards by strict controls on the quality of materials and workmanship. In the 1850s, quality was ensured by a four-part process of paying workers by the piece, identifying the maker of each piece, testing the finished work, and penalizing poor workmanship. Welders, for example were paid 12 cents for each barrel seam welded. An identifying mark was then placed on the part and the barrel was tested. This was done in the proving house, a stout wooden building with a low bench on which the barrels were placed. The barrels were loaded with an extra large charge of powder and fired into a clay bank. If a barrel burst, and the cause was a faulty weld, the welder was fined the whole cost of the part.

Even bayonets were tested to make certain they had the proper spring and would not break in use. This was done in one of two ways: by hanging weights from the top of the bayonet to see how far it would bend or by placing the point in the floor and testing the spring.

Assembly

From the stocking shop, the forges, and the Water Shops the many parts that made up a musket were collected in bins or stacked around the benches where the muskets were assembled.

Because each part was identical to others of the same kind, there was no need during assembly for final fitting or adjustment. With all the pieces at hand, it took a skilled worker about 10 minutes to assemble a musket.

Mass-production techniques had a secondary benefit. If a musket was damaged in use, it could be easily repaired. A new part did not have to be hand made to fit just one musket. Muskets could be quickly repaired in the field from a central supply of parts issued to unit armorers.

Operation

By the time of the Civil War the musket had reached the height of its development. Although it was similar to the musket of the American Revolution, two significant improvements had made it a much more accurate and dependable weapon.

The first was the introduction of rifling, cutting a spiral groove on the inside of the barrel to force the bullet to spin when fired and fly true to the target. The second was the substitution of a percussion-cap primer for the flint-and-powder primer of the older muskets.

To fire the rifled musket it is first loaded with powder and bullet through the muzzle, as in the old-time flintlock. The rifle is then primed with a small, explosive-filled copper percussion cap placed over the cone. The hammer is pulled back to full cock, compressing the main spring.

When the trigger is pulled, the upper part of the trigger pushes against a tab, or tang, on the sear, pushing the front end of the sear out of the cock notch in the tumbler, freeing it to rotate.

The lower limb of the main spring then forces the stirrup down, which in turn causes the tumbler to pivot. The hammer, which is attached to the tumbler, is forced to rotate, striking the primer cap. A small explosion sends a flame through a hole in the cone setting off the powder charge. The expanding gasses from the burning powder force the bullet from the barrel.

Visiting the Site

|

Springfield Armory National Historic Site encompasses approximately 55 acres and several buildings of the original armory complex. The central attraction is the Main Arsenal building, No. 13, constructed in the 1840s during the superintendency of Col. James Wolfe Ripley, a key figure in the armory's history.

The weapons collection housed in the Main Arsenal was started about 1870 by Col. J. G. Benton as a technical "library" for armory personnel. It is now regarded as the world's largest collection of small arms.

Other buildings on the park grounds include the Commanding Officer's Quarters, No. 1, built by Col. Ripley in the 1840s. The cost of this "palace" was the subject of a military court of inquiry. Ripley was exonerated of all charges.

The Master Armorer's House, No. 10, built in the 1830s, was once the home of Erskine Allin, the Master Armorer responsible for the standard breechloading rifle used in the Indian Wars of the late 1800s and in the Spanish-American War.

Buildings

Numbers correspond to those historically assigned to the buildings.

National Historic Site

1 Commanding Officer's Quarters, 1846

10 Master Armorer's House, 1833

13 Main Arsenal, 1847

Armory Square Buildings

5/6 Junior Officer's Quarters, 1870

11 West Arsenal, 1808

14 Middle Arsenal, 1830

15 East Arsenal, 1824

16 Administration, 1819; North and South Shops, 1824

19 Caserne, 1863

About Your Visit

Springfield Armory National Historic Site is open Tuesday through Sunday year-round. It is closed Thanksgiving Day, December 25, and January 1.

Location The site is located in the city of Springfield, Mass., within a short drive of several interstate highways. From I-91, southbound: Take Exit 5, Broad Street. Turn left at bottom of the ramp, left at the stoplight onto East Columbus Avenue, right on State Street, and left on Federal Street. Turn left into the campus of Springfield Technical Community College. Follow the signs to Springfield Armory Museum Parking. From I-91, northbound: Take Exit 4, Broad Street. Go straight at bottom of ramp. Turn right on State Street and proceed as described above to the Armory Museum.

Transportation City buses operate along State Street and connect with the railroad station and the intercity bus terminal.

Source: NPS Brochure (2005)

|

Establishment Springfield Armory National Historic Site — October 26, 1974 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Collection of Annual Reports and Other Important Papers Relating to the Ordnance Department: Volume II (1845 to 1860) (Stephen V. Benét, 1880)

An Armed Campus: Education, Historic Preservation and Civid Life at the Springfield Armory (Graduate Studio in Landscape Architecture, Spring 2006)

Applied Archaeology in Four National Parks Occasional Papers in Applied Archaeology No. 1 (June Evans, James Mueller, Doulas C. Comer, James D. Sorensen, Karen Orrence, Paula A. Zitzler and Louanna Lackey, December 1987)

Archeological Collections Management at The Springfield Armory National Historic Site, Massachusetts ACMP (Archeological Collections Management Project) Series No. 6 (Louise M. DeCesare, 1990)

Collection Management Plan, Springfield Armory (Betsy Bradley, Barclay Rogers, Richard Rattenbury and Arthur C. Allen, March 1977)

Conflicting Goals for a National Park: The Historic Arsenal at Springfield, 1968-2008, Springfield Armory National Historic Site Administrative History (Ned Kaufman, July 2010)

Conservative Innovators and Military Small Arms: An Industrial History of the Springfield Armory, 1794-1968 (Michael S. Raber, Patrick M. Malone, Robert B. Gordon and Carolyn C. Cooper, August 1989)

Cultural Landscape Report for Armory Square, Springfield Armory National Historic Site: Introduction, History, Existing Conditions, Analysis and Treatment Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation (Allison A. Crosbie, 2010)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory, Springfield Armory (2004)

Data for Operational Histories of the U.S. Armories at Harper's Ferry, Virginia, and Springfield, Massachusetts, 1795 to 1860 (Charles W. Snell, January 1980))

Data for Operational Histories of the United States Armories at Harper's Ferry, Virginia, and Springfield, Massachusetts, 1793 to Sept. 30, 1837 (Charles W. Snell, January 1980)

Early Discoveries of Dinosaurs From North America and the Significance of the Springfield Armory Dinosaur Site (Vincent L. Santucci, 2012)

Foundation Document, Springfield Armory National Historic Site, Massachusetts (July 2014)

Foundation Document Overview, Springfield Armory National Historic Site, Massachusetts (July 2014)

General Management Plan/Development Concept Plan, Springfield Armory National Historic Site, Massachusetts (July 1986)

Historic Structure Report, Springfield Armory: Architectural Data Section (Robert L. Carper and Richard G. Turk, September 1984)

Historic Structure Report, Springfield Armory: Historical Data / Base Map (John Albright, May 1978)

Historic Structure Report: Commanding Officer's Quarters (Building 1), Springfield Armory National Historic Site, Springfield, Massachusetts (James J. Lee III and Marilou Ehrler, 2010)

Historic Structure Report: Building No. 5 & 6, Springfield Armory National Historic Site, Springfield, Massachusetts (James J. Lee III, 2012)

Historic Structure Report: Building 19, Springfield Armory National Historic Site, Springfield, Massachusetts: Volume I. Text and Bibliography Draft (Carole Louise Perrault and Judith A. Quinn, November 1991)

Historic Structure Report: Building 19, Springfield Armory National Historic Site, Springfield, Massachusetts: Volume II. Illustrations and Appendices Draft (Carole Louise Perrault and Judith A. Quinn, November 1991)

Historic Structure Report: Building 27, Springfield Armory National Historic Site, Springfield, Massachusetts (James J. Lee III, 2011)

Impacts of Visitor Spending on the Local Economy: Springfield Armory National Historic Site, 2013 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/EQD/NRR—2014/827 (Philip S. Cook, July 2014)

Interpretive Prospectus, Springfield Armory NHS (September 1980)

Junior Ranger Activity Book, Springfield Armory National Historic Site (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

King's Handbook of Springfield, Massachusetts (Moses King, ed., 1884)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Springfield Armory National Historic Site (December 2015)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Armory Square (Polly M. Rettig and Charles E. Shedd, Jr., November 4, 1959, December 2, 1974)

Serial Number Ranges for Springfield Armory-Manufactured Military Firearms (undated)

Special Resource Study: Springfield, Creating a Visitor Economy (1994)

Springfield Armory: Evaluation Under Provision of Historic Preservation Act 1966 (Frank B. Sarles, Denys Peter Myers, Ernest Allen Connally, Russell V. Keune and Roy E. Appleman, August 17, 1967)

The Armory at Springfield (Jacob Abbott, extract from Harper's New Monthly Magazine, No. XXVI, Vol. V, July, 1852)

The Springfield Armory: A Study in Institutional Development (Derwent Stainthorpe Whittlesey, December 1920)

Visitor Study: Summer 2013, Springfield Armory National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/EQD/NRR—2014/797 (Marc F. Manni and Yen Le, April 2014)

spar/index.htm

Last Updated: 22-Feb-2025