|

Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument Arizona |

|

NPS photo | |

Life in a Changing Landscape

The people living just northeast of what is now Flagstaff, Ariz., must have been warned by tremors before debris exploded from the ground and rained down on their pithouses. The lava flows and erupting cinders that followed forced these farmers to vacate the rocky lands they had cultivated for 400 years. A few generations later, at Wupatki and nearby Walnut Canyon, families returned to grow crops for another 100 years in the shadow of Sunset Crater. Slowly, plants and animals returned too, some specially adapted to living on the lava. By the late 1800s ranching and logging operations sustained the new populations settling Flagstaff, and the memory of the most recent eruption on the Colorado Plateau lived only in the stories of indigenous Southwest people. Today occasional earthquakes still remind local residents that they live in a geologically active area. At Wupatki and Sunset Crater Volcano national monuments, we contemplate how the environment and people change each other.

The remains of masonry pueblos, or villages, that dot the landscape of Wupatki are the most obvious evidence of the human endeavor in this expansive land. They tell of the 1100s when puebloan peoples came together to build a vast farming community. Some of these villagers may have migrated from drought-stressed areas on the Colorado Plateau to join people already living here. With the first eruption of Sunset Crater, the agricultural potential improved because the thin ash layer absorbed precious moisture and helped prevent evaporation, and a climate change provided more rainfall during the growing season.

By 1180 thousands of people were farming on the Wupatki landscape. By 1250, when the volcano had quieted, pueblos stood empty. The people of Wupatki had moved on and established new homes. Many people traversed the high deserts of the Colorado Plateau over time, but few stayed long. Those who did adapted to the region's challenging environment. Their descendants still live nearby, including Hopi, Zuni, and Navajo people.

Nineteenth-century explorers such as John Wesley Powell marveled at the well-preserved pueblos and the stark but strangely beautiful volcanic landscape. With the founding of Flagstaff, travelers sought out these local attractions. Early visitors explored the lava flows and took rocks for souvenirs. Others looted the archeological sites. In 1928 filmmakers wishing to create a landslide at Sunset Crater inadvertently created a national monument instead. Activists, fearing irreversible damage to the volcano, pushed for protection of the area; and, in 1930, President Hoover established Sunset Crater National Monument (later renamed Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument) as part of the National Park System. Years and thousands of volcano-climbing visitors later, the scarred mountain was closed to climbers. Now this cinder cone is recovering. Other nearby volcanoes, which are not in the park, are mined for pumice and cinders or used for off-road recreation.

Each time a volcano erupts, life begins anew. Like farming the high desert of Wupatki, establishing life in this environment may seem an impossible challenge. But a closer look reveals a pink penstemon radiant against the black rock, its species unique to this rugged terrain. Ponderosa pines, their growth stunted by harsh conditions, offer habitat for Abert's squirrels. Lichen adds a touch of color and slowly converts rock to soil. The volcanic landscape reminds us that only change is constant. It is mute testimony to the forces that will undoubtedly affect the land and its inhabitants again.

Sunset Crater: Birth of a Mountain

Erupting sometime between 1040 and 1100 Sunset Crater is the most recent in a six-million-year history of volcanic activity in the Flagstaff area. This cinder cone reminds us of the powerful forces that shape the Earth—forces that have created more than 600 hills and mountains in the San Francisco volcanic field. These mountains have in turn affected the climate and habitat for all things living in this region.

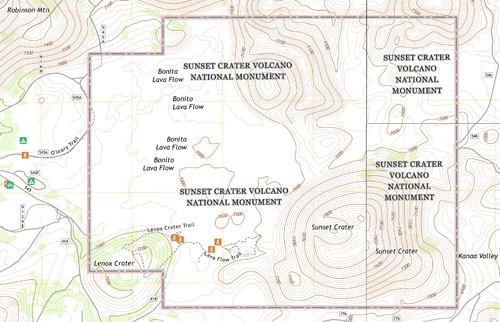

What is now a 1,000-foot-high volcano began to form when molten rock sprayed high into the air from a crack in the ground, solidified, then fell to Earth as large bombs or smaller cinders. As periodic eruptions continued, the heavier debris accumulated around the vent. The lightest, smallest particles were carried the farthest by wind, dusting 800 square miles of northern Arizona with ash. Perhaps as spectacular as the original eruption were two lava flows: the Kana-a and the Bonito. They destroyed all living things in their path.

The processes that created Sunset Crater also created a sculpture garden of extraordinary forms at its base. As new gas vents opened, spatter cones sprouted from the ground—like miniatures of the volcano itself. Partially cooled lava, pushing through cracks in the crust like toothpaste from a tube, solidified into wedge-shaped squeeze-ups, grooved from scraping against harder rock.

The entire event may have lasted six months to a year. In a final burst of activity red and yellow oxidized cinders shot out of the vent and fell onto the rim. The colorful glow from these cinders reminded people of a sunset and led to the volcano's name.

Formation of a Cinder Cone

Cinder cones, such as Sunset Crater, are formed during early explosive stages of an eruption. Magma, a mixture of molten rock and highly compressed gases, rises upward from its underground source. As the magma ascends, the extreme pressure drops and gases are released.

The high percentage of gas in the magma causes an explosion out of the central vent. Solidified rock pieces of various sizes fall around the vent, creating a mound or cone. Magma with a lower gas content produces lava flows that may issue from the side or base of the cone.

Exploring Wupatki and Sunset Crater Volcano

The landscape that shaped the lives of people 800 years ago appears unchanged in many ways since the eruptions. The lava flows near Sunset Crater seem to have hardened to a rough surface only yesterday. From a distance the pueblos at Wupatki National Monument look as though they could still be occupied. But many processes have been at work, reshaping the land into what we see today.

Volcanism, tectonics, and erosion have created dramatic geological formations and abrupt changes in elevation and climate. As you travel the loop road between Sunset Crater Volcano and Wupatki national monuments, the environments range from desert to mountain. Ecosystem changes are distinct and frequent. These changes within a relatively short distance greatly increase the biological diversity of the area—a diversity that was indispensable to early residents.

Residents, in turn, transformed the land as they harvested the wood for homes and fuel, hunted and gathered wild foods, and introduced cultivated crops. Later, Navajo families settled the Wupatki area and brought sheep to the land. Beginning in the 19th century, newcomers introduced cattle, tapped ground water supplies and interrupted the natural processes of wildfire. As a result, juniper trees have invaded grasslands; ponderosa forests are no longer open and spacious but dense with undergrowth; some seeps and springs no longer flow.

These habitat changes have affected some species and created new niches for others. In the higher elevations among the ponderosa pine, Abert's squirrels and vivid blue Steller jays are common. Middle elevations support pinyon pine, one-seed juniper, and grasslands, along with jackrabbits and pronghorn antelope. In the lower lands, the more sparsely vegetated high desert community is home to lizards, snakes, coyotes, and bobcats.

As part of the National Park System, Wupatki and Sunset Crater Volcano national monuments are managed to perpetuate this geologic landscape that preserves increasingly rare habitat for native plants and animals and to protect past human developments and their relationships to the land.

About Your Visit

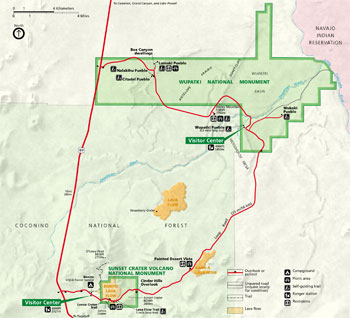

(click for larger maps) |

Wupatki National Monument protects the ancient dwellings of puebloan peoples. It occupies 56 square miles of dry, rugged land on the southwestern Colorado Plateau directly west of the Little Colorado River. Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument features a 1,000-foot volcanic cone and its lava flows.

Location, Hours, and Facilities

Sunset Crater Volcano and Wupatki national monuments are reached via U.S. 89.

Their entrances are located 12 miles and 26 miles north of Flagstaff, Ariz. The

parks are connected by a 35-mile loop road. A single entrance fee covers both

parks.

Sunset Crater Volcano Visitor Center, two miles east of the park entrance off U.S. 89, has information, exhibits, and a seismograph station.

Wupatki Visitor Center, 14 miles southeast of the park entrance off U.S. 89, has exhibits and displays of artifacts.

The visitor centers are open daily except December 25; hours vary seasonally. Trails are open daylight hours only. Note: this part of Arizona stays on Mountain Standard Time year-round.

There are no gasoline stations, restaurants, or overnight accommodations in either park. Full services are available in Flagstaff and along U.S. 89. Several picnic areas are located along the loop road. Open fires are allowed only where fire grates are provided. Wood collecting is not permitted.

Camping

The U.S. Forest Service operates Bonito Campground near Sunset Crater. The

facilities include running water and restrooms, but there are no showers or

trailer hookups. The campground is open from late spring through early fall. For

additional camping information contact: Coconino National Forest, Peaks Ranger

Station, 5010 N. Hwy. 89, Flagstaff, AZ 86004; http://www.fs.fed.us/r3/coconino/recreation/pea ks/rec_peaks.shtml

What to See and Do

A driving tour of both parks takes one to two hours. To walk the trails and stop

at the visitor centers, allow three to four hours. At Sunset Crater, the

one-mile Lava Flow Trail at the volcano's base allows you to see a variety of

features. Sunset Crater is closed to climbing to protect its fragile resources.

You may climb other cinder cones in the area, such as nearby Lenox Crater and

Doney Mountain at Wupatki.

Ask at the visitor center for hiking information. A short self-guiding tour of Wupatki Pueblo, the largest dwelling in that monument, begins behind the visitor center. Other sites are also reached by trails: Lomaki Pueblo is a half-mile off the main loop road; Citadel and Nalakihu pueblos are next to the road. A 2½-mile spur road leads to Wukoki Pueblo. All other sites are closed to protect the fragile archeological resources.

For More Information

Walnut Canyon, Wupatki, and Sunset Crater Volcano national monuments are

administered as the Flagstaff Area National Monuments from a headquarters in

Flagstaff, Ariz.

Flagstaff Area National Monuments

6400 N. Highway 89

Flagstaff, AZ 86004

Wupatki National Monument

www.nps.gov/wupa

Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument

www. nps.gov/sucr

Accessibility

Some features in both parks are accessible for visitors with disabilities. Ask

at the visitor centers for more information.

For Your Safety and to Protect the Parks

• All plants, animals, and archeological objects in the parks are protected

by federal laws; there are substantial fines for damage to or removal of these

resources.

• Pets must be kept on a leash at all times; they are not allowed in

buildings or on park trails. Nearby national forest lands offer an alternative

for people traveling with pets; please inquire. The summer heat is intense; pets

left in vehicles—even for a short time—can suffer heat stroke and

die.

• The loop road through the parks is narrow and winding, with soft

shoulders. Stop only at designated pullouts. The speed limits are reduced for

the safety of pedestrians and wildlife. Both parks are at a high elevation and

road surfaces can freeze quickly in winter.

• Stay on the trails to help prevent erosion and to protect the fragile

resources, such as the plants and animals that live here. Off-trail travel is

not permitted in either park. Lava is sharp, brittle, and unstable. A fall on

cinder or lava is not a pleasant experience.

Source: NPS Brochure (2019)

|

Establishment

Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument — November 16, 1990 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Geologic Field Guide to S P Mountain and its Lava Flow, San Francisco Volcanic Field, Arizona U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2021-1072 (Amber L. Gullikson, M. Elise Rumpf, Lauren A. Edgar, Laszlo P. Keszthelyi, James A. Skinner, Jr. and Lisa Thompson, 2021)

A Prehistoric Sinagua Agricultural Site in the Ashfall Zone of Sunset Crater, Arizona (G. Lennis Berlin, David E. Salas and Phil R. Geib, extract from Journal of Field Archaeology, Vol. 37, 1990)

Acoustical Monitoring 2010: Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRSS/NRTR-2013/761 (June 2013)

Arizona Explorer Junior Ranger (Date Unknown)

Conduit dynamics of highly explosive basaltic eruptions: The 1085 CE Sunset Crater sub-Plinian events (G. La Spina, A.B. Clarke, M. de Michieli Vitturi, M. Burton, C.M. Allison, K. Roggensack and F. Alfano, extract from Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, Vol. 387, August 7, 2019)

Cultural Affiliations of the Flagstaff Area National Monuments: Sunset Crater Volcano, Walnut Canyon, and Wupatki Final Report (Rebecca S. Toupal and Heather Fauland, September 26, 2007)

Culture of Sites Which Were Occupied Shortly Before the Eruption of Sunset Crater Museum of Norther Arizona Bulletin No. 9 (J.C. McGregor, October 1936)

Foundation Document, Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument, Arizona (May 2015)

Foundation Document Overview, Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument, Arizona (January 2015)

General Management Plan / Final Environmental Assessment, Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument (November 2002)

Geologic Map, Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument (2005)

Geologic Resource Evaluation Report, Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2005/004 (T.L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, September 2005)

Ground water in the Wupatki and Sunset Crater National Monuments, Coconino County, Arizona USGS Water Supply Paper 1475-J (Oliver J. Cosner, 1962)

Highly explosive basaltic eruptions driven by CO2 exsolution (Chelsea M. Allison, Kurt Roggensack and Amanda B. Clarke, extract from Neture Communications, 2021)

Interpretive Prospectus, Sunset Crater National Monument and Wupatki National Monument, Arizona (December 1983)

Inventory of Mammals at Walnut Canyon, Wupatki, and Sunset Crater National Monuments NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SCPN/NRTR-2009/278 (Charles Dost, December 2009)

Junior Arizona Archeologist (2016)

Logging Adjacent to Walnut Canyon and Sunset Crater Volcano National Monuments (Jeri DeYoung, 1999)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Sunset Crater - Cinder Lake Apollo Mission Testing and Training Historic District (Benjamin T. Carver, July 30, 2018)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SCPN/NRR-2018/1837 (Lisa Baril, Patricia Valentine-Darby, Kimberly Struthers, Paul Whitefield, Kirk Anderson and Mark Brunson, December 2018)

Natural Resource Survey and Analysis of Sunset Crater and Wupatki National Monuments Final Report (Gary C. Bateman, December 1976; incomplete)

Natural Resource Survey and Analysis of Sunset Crater and Wupatki National Monuments Final Report (Phase III) (Gary C. Bateman, January 1980; incomplete)

Natural Resource Survey and Analysis of Sunset Crater and Wupatki National Monuments Final Report (Phase IV) (Gary C. Bateman, January 1981; incomplete)

Park Newspaper (InterPARK Messenger): c1990s • 1992

Park Newspaper (Ancient Times): 1998-1999 • 2000-2001 • 2003 • 2004 • 2006-2007 • 2007-2008 • 2016 • 2017

Roadside Geology: Wupatki and Sunset Crater Volcano National Monuments Arizona Geological Survey Down-To-Earth 15 (Sarah L. Hanson, 2003; ©Arizona Geological Survey)

Seed Plants of Wupatki and Sunset Crater National Monuments Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin 37 (W.B. McDougall, 1962, ©Museum of Northern Arizona, Archives, all rights reserved)

Soil Survey of Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument, Arizona (2014)

Sunset Crater Geological Report Southwestern Monuments Special Report No. 3 (Vincent W. Vandiver, 1936)

Talking with a Volcano: Native American Perspectives on the Eruption of Sunset Crater, Arizona (Richard Stoffle and Katheleen Van Vlack, extract from Land, Vol. 11, January 26, 2022)

The Road Inventory for the Flagstaff Area Parks: Sunset Crater Volcano, Wupatki, and Walnut Canyon National Monuments (Federal Highway Administration, April 1999 )

Traditional Resource Use of the Flagstaff Area Monuments Final Report (Rebecca S. Toupal and Richard W. Stoffle, July 19, 2004)

Trail Plan and General Management Plan Amendment Environmental Assessment, Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument (June 17, 2013)

Variable effects of cinder-cone eruptions on prehistoric agrarian human populations in the American southwest (Michael H. Ort, Mark D. Elson, Kirk C. Anderson, Wendell A. Duffield and Terry L. Samples, extract from Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, Vol. 176, June 3, 2008)

sucr/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025