|

Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve Kansas |

|

NPS photo | |

"Whenever you stop on the prairie to lunch or camp, and gaze around, there is a picture such as poet and painter never succeeded in transferring to book or canvas...

[We] ought to have saved a...Park in Kansas,, ten thousand acres broad—the prarie as it came from the hand of God, not a foot or an inch desecrated by 'improvement' and 'cultivation.' It is only a memory now."

—D.W. Wilder, editor of the Hiawatha World, 1884

THE LAST STAND

Tallgrass prairie once covered 140 million acres of North America. Now less than 4 percent remains, mostly in the Flint Hills of Kansas. On November 12, 1996, Congress created the 10,894-acre preserve, protecting a nationally significant example of the once-vast tallgrass prairie ecosystem, while preserving a unique collection of cultural resources from prehistoric times through the ranching era.

Central North America, once called the Great American Desert, supports three types of grasslands. Tallgrass, mixed grass, and short grass prairies respond to decreasing rainfall amounts, while providing food and habitat for hundreds of prairie animals. Four grasses dominate tallgrass prairie—big and little bluestem, switch grass, and Indian grass. Travelers and traders crossed the vast prairie to find greater opportunities, but development was inevitable as settlers discovered the rich prairie soil.

After John Deere invented the steel moldboard plow—it could cut tough prairie sod—settling and cultivating the prairie grew by leaps and bounds. In less than a generation the prairie soil was broken, the land settled and forever changed.

American Indians knew well the value of the prairie and of human harmony with nature. Tribes of Kaw, Osage, Wichita, and Pawnee made this region their home and hunting grounds. Millions of bison roamed the plains, providing food, shelter, and ceremonial life for the tribes. As the United States expanded, Indian removal policies forced the Indians onto reservations and changed their cultures. In part to subdue the Indians, the bison were slaughtered almost to extinction. As settlement and agriculture followed, the tallgrass prairie made its last stand.

A LIMESTONE LAYER CAKE

THE FLINT HILLS OF KANSAS Over 2S0 million years ago this area was a vast inland sea that deposited great layers of limestone, shale, and flint. The Flint Hills were created as softer shales eroded away, leaving behind hardened flint shelves, in a process called differential erosion. The Flint Hills were too rocky to plow, except in the bottomland of creeks and rivers.

PRAIRIE FIRES Before humans lived here, lightning-ignited fires raced unchecked over the prairie until a large river or stream stopped them. Bison followed the burning prairie, grazing on tender new plant shoots Seeing this, American Indians used fire for attracting large grazing animals to hunt. Managing the prairie by using fire and grazing allows for greater prairie diversity. Today the preserve staff works to mimic these natural processes for the prairie's health.

THE PRAIRIE LIVES UNDERGROUND

A significant world exists underground as the tallgrass prairie root systems reach down 15 to 25 feet into the soil, surviving fire, drought, and the changing environment. In dry periods prairie plants go dormant conserving energy for regrowth when rain penetrates the soil. Thousands of nematodes and other animals help keep the prairie healthy through their normal life functions. They turn and aerate soil by digestion or burrowing. A handful of sod can hold 50-100 nematode species, microscopic worms that eat their way through soil. Burrowing mammals and reptiles evade predators by tunneling.

Over 200 springs and seeps on the preserve begin underground and meander through layers of limestone before they reach the surface. Aquatic life, like the endangered Topeka shiner, thrives in these pools and streams. This seldom-seen underground world—nematodes and vast plant root systems mining rich, deep soils—gives life to the creatures above.

PRAIRIE LIFE ABOVE GROUND

Over 400 species of plants, 150 kinds of birds, 39 types of reptiles and amphibians, and 31 species of mammals await your discovery here. Examples of most commonly seen animals are rabbits, turkeys, ornate box turtles, snakes, upland sandpipers, collared lizards, and grasshoppers. Far more elusive are foxes, pocket gophers, coyotes, and deer. Bears, antelopes, panthers, and bison roamed the North American prairie before it was settled.

Greater prairie-chickens prefer areas away from human activity and their presence indicates that the prairie is biologically diverse. These members of the grouse family need taller, denser grasses for nesting, but they also need open spaces, with shorter vegetation—called leks or booming grounds—for breeding. Where the, conditions are diverse, prairie chickens will return to the same leks yearly to mate. The birds are threatened by habitat loss, due to conversion of native prairie to cropland and development.

Prairie life above and below ground work together, along with the preserve's cultural heritage, to tell the continually unfolding story of this fascinating and special place.

Legacy of the Tallgrass Prairie

ONE PRAIRIE, MANY PEOPLE

Before this land became Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, many people had cared for it. Set in the Flint Hills of Kansas, this was the traditional land of the Kaw, Osage, Wichita, and Pawnee before its legacy of owners, which included railroads, settlers, ranchers, and business people.

In 1878 Stephen F. and Louisa Jones came here to build a cattle feeding station for their family's Colorado cattle operation. They bought land from individuals and the railroad, growing the Spring Hill Farm and Stock Ranch to 7,000 acres. The Joneses owned the land only 10 years, but left behind ranch buildings in the Second Empire architectural style. They also left over 30 miles of stone fence that had been needed when the cattle range went from open to closed. The fence remnants remind us of this period of change in the cattle industry.

Barney Lantry, the Joneses' neighbor and business partner, bought the ranch in 1888. He combined it with his own ranch for a total of 13,000 acres. After he died, the ranch went through a series of subdivisions, including 1909 to 1935 when the Benninghoven family owned part of the ranch. After they lost it in the Great Depression, George Davis bought it and other land to reunite the Jones and Lantry ranches. In 1955 Davis died; his 11,000-acre ranch with its grand buildings became the Z Bar Ranch.

The Z Bar Ranch, with all the Joneses' grand structures intact, became Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve in 1996. The Nature Conservancy, which owns most of the land, manages the preserve with the National Park Service. As you experience the park, look for clues to the past, present, and future of this prairie legacy.

The Ranch Buildings

The Spring Hill/Z Bar Ranch represents a continuous ranching legacy from 1878 to its earliest beginnings as well as changes made by the ranch's many owners. The original owners, Stephen and Louisa Jones, built the nearby Lower Fox Creek School and their daughter Loutie attended.

LIMESTONE BARN

This massive limestone barn, 110x60 feet, housed livestock, equipment, and

enough hay and grain to feed the animals in winter. In 1882, 5,000 pounds of tin

covered the roof. The grain bins, cupolas, and iron support beams were added in

the 1940s.

CORRALS AND FENCES

The Joneses enclosed the 7,000-acre ranch using a readily available

resource—limestone. They also built inner pasture fences for selective

breeding and to carefully distribute cattle in grazing areas.

OUTBUILDINGS

Built after 1900 these were workshops and storage for vehicles and

equipment.

SCRATCH SHED

This shed enabled chickens to exercise in winter, which boosted egg production.

South-facing windows let in plenty of sunlight to warm the interior. The

building was remodeled many times.

CHICKEN HOUSE

The hill and the sod roof of this 1882 building provide natural insulation. Two

ceiling vents regulate temperature and air flow, promoting greater egg

production. The west door led to the scratch shed.

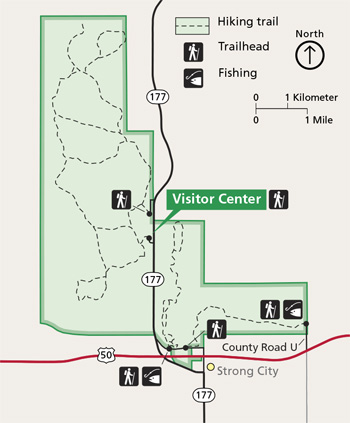

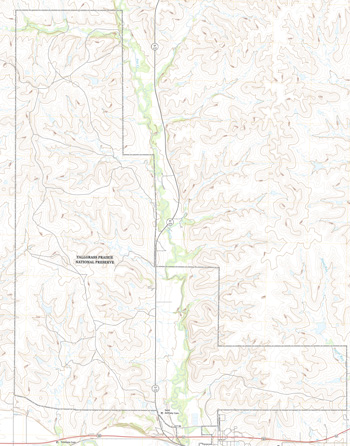

(click for larger maps) |

CARRIAGE HOUSE

Built between 1910 and 1920, this building housed ranch vehicles and

equipment.

RANCH HOUSE

Built in 1881, this limestone mansion is classic Second Empire style. Its

features include a mansard roof, large windows, solid walnut staircase, faux

painted woodwork, ornate cornices, and ceiling medallions. The house was built

into the hill for natural insulation and used spring water, piped through an

intricate underground system.

CURING HOUSE

The Joneses used this 1881 structure to cure ham and other meats, which were

hung from hooks in the rafters. Port holes and cupola vents allowed the air

circulation needed for proper curing.

OUTHOUSE

Built in 1881. this building has interior walls of rough-cut ashlar stone and

exterior walls of block limestone. Its three holes, two for adults and one for

children, are unusual for ranch outhouses.

ICE HOUSE

Built in 1882, this structure stored ice cut from the Cottonwood River and other

nearby sources. The ice was placed in sawdust and hay for insulation. This gave

the Joneses ice all year, a luxury for the time. The door was originally on the

north side, but was moved to the south to meet the ranch's changing needs.

SOUTHWIND NATURE TRAIL and LOWER FOX CREEK SCHOOL

Built in 1882, this one-room school served students until 1930, when it was

abandoned and reverted to the ranch owner, The school is a ½-mile walk

from the ranch headquarters.

EXPLORING THE PARK

The preserve is near Strong City, KS, between Wichita and Topeka. Hours and programs are listed on the park website. You can observe ranch activities, and enjoy hiking, fishing (catch and release only), programs, and tours. The visitor center is two miles north of the US 50 and KS 177 intersection, ½ mile west of Strong City.

Park programs include living history demonstrations, ranch building tours, guided prairie tours, and self-guiding cell phone tours. Children can participate in a Junior Ranger program.

FOR YOUR SAFETY In case of emergency call 911. • Cell phone coverage is not reliable in the park. • Report accidents or safety hazards to a park ranger. • Be cautious around wildlife such as bison and rattlesnakes. • Carry plenty of water. • Watch for fires, which can move very fast here. • Be aware of changing weather.

FIREARMS For firearms regulations, check the park website.

ACCESSIBILITY The visitor center is accessible but most historic buildings are not. We strive to improve our facilities, services, and programs so they are accessible to all. Contact the park for the latest information.

Source: NPS Brochure (2014)

|

Establishment Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve — November 12, 1996 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Acoustic Bat Surveys at Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, 2014-15 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/TAPR/NRR—2016/1350 (Daniel S. Licht, December 2016)

An Identification of Prairie in National Park Units in the Great Plains NPS Occasional Paper No. 7 (James Stubbendieck and Gary Willson, 1986)

Aquatic Invertebrate Monitoring at Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, 2009 Status Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/HTLN/NRDS—2012/268 (J. Tyler Cribbs and David E Bowles, March 2012)

Aquatic Invertebrate Monitoring at Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, 2009-2015 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/TAPR/NRDS—2016/1062 (David E. Bowles, J. Tyler Cribbs and Janice A. Hinsey, October 2016)

Archeological Overview and Assessment for Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Chase County, Kansas Midwest Archeological Center Technical Report No. 61 (Bruce A. Jones, 1999)

Baseline Plant Community Monitoring Report, Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR-2006/019 (Alicia Sasseen and Mike DeBacker, April 2006)

Bird Monitoring at Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Kansas — 2001-2008 Status Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR-2010/318 (David G. Peitz, Michelle M. Guck and Kevin M. James, April 2010)

Bird Monitoring at Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Kansas — 2001-2010 Status Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/HTLN/NRDS-2011/165 (David G. Peitz, May 2011)

Bird Monitoring at Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Kansas — Status Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HTLN/NRR-2015/1039 (David G. September 2015)

Bird Monitoring at Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Kansas — Status Report 2001-2018 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HTLN/NRR-2020/2072 (David G. Peitz and Kathleen A. Kull, February 2020)

Bird Monitoring at Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Kansas — Status Report 2001-2023 NPS Science Report NPS/SR-2024/204 (David G. Peitz, October 2024)

Cultural Landscape Report: Tallgrass Praire National Preserve, Chase County, Kansas (Land and Community Assoc. and Bahr Vermeer & Haecker, October 2004)

Evaluating Long-term Trends in Vegetation and Management Intensity: Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve 1995–2014 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HTLN/NRR—2018/1582 (Sherry A. Leis and Lloyd W. Morrison, January 2018)

Evaluative Testing at the Fountain Cistern, Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Kansas Midwest Archeological Center Technical Report Series No. 95 (Bruce A. Jones, 2007)

Fire Effects on Wildlife in Tallgrass Prairie NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HTLN/NRR—2010/193 (Maria Gaetani, Kayla Cook and Sherry Leis, May 2010)

Fish Community Monitoring at Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve: 2001–2008 Trend Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR—2010/325 (Hope R. Dodd, Lloyd W. Morrison and David G. Peitz, May 2010)

Foundation Document, Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Kansas (June 2017)

Foundation Document Overview, Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Kansas (June 2017)

General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Kansas (September 2000)

Geologic Map of Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve (2022)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report: Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR-2022/2462 (Michael Barthelmes, September 2022)

Grassland Bird Monitoring at Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Nebraska and Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Kansas: 2001-2003 Status Report (David G. Peitz and Gareth A. Rowell, November 7, 2003)

Guardabosques Menor Estación, Reserva Nacional Tallgrass Prairie (Date Unknown; solo para fines de referencia)

Historic Resource Study: Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve (Hal K. Rothman and Daniel J. Holder, 2000)

Historic Structures Report: Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Strong City, Kansas (Quinn Evans Architects, January 2005)

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Tallgrass Priaire National Preserve: Year 1 (2006) NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR-2007/014 (Craig C. Young, Jennifer L. Haack, J. Tyler Cribbs and Holly J. Etheridge, March 2007)

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve: Year 2 (2010) NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR—2011/476 (Jordan C. Bell, Craig C. Young, Lloyd W. Morrison and Chad S. Gross, August 2011)

Junior Ranger Station, Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Legislative History, 1920-1996: Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve (HTML edition) (Tallgrass Historians, L.C., 1998)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan: Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve (September 2005)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Spring Hill Ranch (Deon K. Wolfenbarger and Dale Nimz, March 5, 1996)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/TAPR/NRR-2019/2043 (David S. Jones, Roy Cook, John Sovell, Christopher Herron, Jay Benner, Karin Decker, Andrew Beavers, Johannes Beebee, David Weinzimmer and Rob Schorr, November 2019)

Plant Community Monitoring Trend Report, Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR-2007/030 (Kevin James and Mike DeBacker, May 2007)

Plant Community Monitoring Trends at Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve: 1998-2018 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR-2022/2463 (Sherry A. Leis and Lloyd W. Morrison, September 2022)

Prescribed Fire Monitoring Report: Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve 2014 (IQCS fire number 285382, 285383, 266782, 285677) NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HTLN/NRR—2015/1025 (Sherry A. Leis and Sarah E. Hinman, September 2015)

Soil Survey of Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Kansas (2013)

Special Resource Study: Z-Bar (Spring Hill) Ranch, Chase County, Kansas (March 1991)

Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve 2015 Post-burn Summary NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/HTLN/NRDS—2016/1001 (Sherry A. Leis and Sarah E. Hinman, January 2016)

Tough as the Hills: The Making of the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve (Rebecca Conard, extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 29 No. 2, Summer 2006)

Vegetation Classification and Mapping of Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve: Project Report NPS Natural Resource Report NRR/HTLN/NRR—2011/346 (Kelly Kindscher, Hayley Kilroy, Jennifer Delisle, Quinn Long, Hillary Loring, Kevin Dobbs and Jim Drake, April 2011)

A National Tallgrass Prairie Preserve? (William Penn Mott, extract from The Prairie: Roots of Our Culture; Foundation of our Economy, Proceedings of the Tenth North American Prairie Conference of Texas Woman's University, January 1988)

Cultural Resources Survey: Proposed Prairie National Park, Kansas and Oklahoma (Ronald W. Johnson, November 1974)

Planning for an Osage Prairie National Preserve (Douglas D. Faris, extract from The Prairie: Roots of Our Culture; Foundation of our Economy, Proceedings of the Tenth North American Prairie Conference of Texas Woman's University, January 1988)

Preliminary Environmental Assessment/Alternative Study Areas, Proposed Prairie National Park, Kansas/Oklahoma (October 1975)

Preliminary Environmental Assessment/Appendixes A thru N, Proposed Prairie National Park, Kansas/Oklahoma (October 1975)

The Proposed Prairie National Park: A Case Study of the Controversial National Park Service (©James Lester Swint, Master's Thesis Kansas State University, 1971)

tapr/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025