|

Tonto National Monument Arizona |

|

NPS photo | |

Tonto Basin's Prehistoric People of the Salt River

Shallow caves overlooking today's Theodore Roosevelt Lake in central Arizona shelter dwellings that are nearly 700 years old. Lying between the northern Colorado Plateau and the southern Sonoran Desert, Tonto Basin is one of many valleys and basins with evidence of early farming activity.

Tonto Basin's 300 square miles support diverse animals and plants, from mountain pines to desert cacti. Tonto Creek and the Salt River deposit rich soils along the valley floor, nourishing mesquite, Arizona walnut, and sycamore. Hillsides and mesas are blanketed with saguaro, cholla, prickly pear, agave, and jojoba, the higher elevations with oak, juniper, pinyon, and ponderosa pine. Deer, rabbit, quail, and other wildlife are integral parts of this ecosystem. For thousands of years people took advantage of the basin's bountiful offerings.

The first people to settle here permanently arrived between the years 100 and 600. Eagle Ridge, a village of 15 pit houses, is one of Tonto Basin's earliest farming communities. Like their hunter-gatherer predecessors. Eagle Ridge residents harvested plants and hunted animals but, unlike their ancestors, they grew corn, beans, and cotton. A valuable archeological find, Eagle Ridge allows us to see people in the transition from hunter-gatherers to sedentary farmers. They were the forerunners of agricultural groups soon to emerge. About the year 600, people left this community, with no evidence of human activity in Tonto Basin for the next 150 years.

By 750 people from the lower Gila and Salt River valleys (near today's Phoenix) built pit house villages in Tonto Basin. Identified by the patterns of their villages and their red-on-buff pottery, they were an extension of the southern Hohokam farmers. For 400 years they used irrigation farming to grow corn, beans, squash, and cotton. They traded goods across a network that reached from Colorado to the Gulf of California. Populations to the north and east had grown too. They were the puebloan groups, and by 1100 their populations rivaled the desert Hohokam.

Starting in the 1100s population centers approached their social and economic peak. Archeological evidence indicates that drought, plant and animal depletion, and population growth pushed resource availability to critical levels. Faced with instability, many northern pueblo groups left their homelands, and the Colorado Plateau and Central Mountain populations declined. According to the traditions of their descendants, people settled, then moved on, as part of their quest to find permanent homelands. Social and environmental upsets were often signals to resume migrations and fulfill their destiny. Migrations took them to what are now western New Mexico and central, southern, and eastern Arizona. Evidence of such a migration emerged in Tonto Basin's archeological record. By 1250 people occupied prime land on the valley floor, and the new arrivals began settling in the basin's upper elevations.

As people arrived, communities absorbed their new ideas, technologies, and philosophies, resulting in changes to Tonto Basin's cultural identity. At this time Salado polychrome pottery appears in the archeological record. Named for the Rio Salado (Salt River) that flows through the basin, this pottery style reflects the changing times. Migrations continued, and populations grew. By 1275 thousands of people lived in Tonto Basin. Archeologists call this mixed-cultural phenomenon Salado.

During the early 1300s climate favored the people of the basin. Moisture increased farming potential, and plant and animal populations flourished. Around 1330 a dramatic change occurred. The region became more arid—lowering water tables. The changing climate decreased farming and increased hunting and gathering, severely impacting the ecosystem. Important plants and animals declined or disappeared. Competition for dwindling resources created stress among the villagers.

As tensions grew, people left their smaller villages and crowded into communities on the valley floor. At the same time people moved into the Tonto cliff dwellings. Some built defensive walls around villages, while others built on defensible hilltops and in caves. In the late 1300s resource depletion intensified, and populations declined.

The 1300s were also marked by catastrophic flooding of the Salt River that destroyed lowland farms and villages. When the waters receded, many of the 100-year-old irrigation canals were undermined or destroyed, and hundreds of acres of farmland were useless. By 1450 those struggling to maintain their way of life gave up—and another migration began. Oral histories say this migration from Tonto Basin took their ancestors in many directions, guiding each to the place their descendants now call home.

The cliff dwellings at Tonto National Monument are but two of hundreds of once-thriving communities in Tonto Basin. Preserved and protected by the National Park Service, they stand as icons of people who flourished and struggled as their world changed.

Reading the Salado Past

Distance and rugged terrain isolated the cliff dwellings from the modern world until the mid-1870s when ranchers and soldiers came to the Tonto Basin. Construction began on Theodore Roosevelt Dam in 1906, bringing attention to the dwellings. The following year, recognizing the need to protect the sites from vandals and pothunters. President Theodore Roosevelt set the area aside as a national monument.

Today these cliff dwellings give rise to questions about the Salado people and their way of life. Most of what we know—or think we know—about the Salado has been reconstructed from what remains of their material culture, their personal and community belongings. Taken together, Salado artifacts give us a picture of an adaptable people who coped successfully with a dry, harsh climate and made the most of their environment. Some of the findings: Salado dwellings were permanent, indicating a farming people were on hand year-round to tend crops. Outlines of irrigation canals were visible until flooded by Theodore Roosevelt Lake. Decorated earthenware and intricate textiles reveal that not all of the people devoted their efforts to farming; some had the interest and time to master other skills. Seashells found here came from the Gulf of California and macaw feathers from Mexico, showing that the owners participated in trade with remote groups. Ideas made the circuit along with trade goods, for much of Salado technology resembles that of other native people.

We are fortunate to have available for study the very objects the Salado created for their own use or obtained in trade. Plants and animals that made up their naturai environment still thrive here. Like pieces of a puzzle, each element contributes to the larger picture of Salado culture. As you explore this ancient place, please remember that you, too, are responsible for its preservation. Keep the pieces of the puzzle together. What you find here, leave here.

The ancient people built dwellings in the valley and on hillsides and diverted water for crops. Cattle grazing in the 1800s destroyed some plant species and increased erosion.

Today Theodore Roosevelt Lake covers old farmlands and supplies electrical power and water for irrigation and recreation.

Plants and Animals of the Sonoran Desert

The Salado looked to the desert to supplement cultivated foods and fulfill their

material needs. Mammals, birds, and reptiles were important to their diet. They

made tools from bones. Yucca provided edible stalks and buds, sewing needles

from leaf tips, leaf fiber for rope, nets, mats, and sandals, and roots for

making soap. Tender new leaf pads and fruit from the prickly pear offered

seasonal variety, as did the sweet, red fruit of the saguaro. Saguaro ribs were

used to build ceilings. Beans from the mesquite tree, eaten raw or roasted, or

ground into flour, were rich in protein.

Polychrome Pottery

We can identify Southwestern cultures by their pottery because the vessels and

shards survive for centuries, and because the artistry and materials vary from

place to place. Like other Pueblo people, Salado women fashioned plain and

decorated wares for cooking, storage, and ceremonial use. Red clay came from

local pits along the river or on hillsides, and coloring was derived from plants

and minerals.

Woven Sandals

Footwear was made from yucca or agave fibers. Many Tonto specimens are

exquisitely crafted. Matting might be woven from nolina or sotol. The Salado

made a variety of close-coiled and coarse baskets.

Stone Grinding Tools

The mano and metate were commonly used in Southwestern agricultural societies to

crush corn, beans, seeds, and nuts.

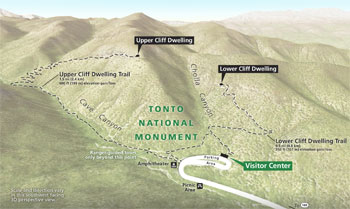

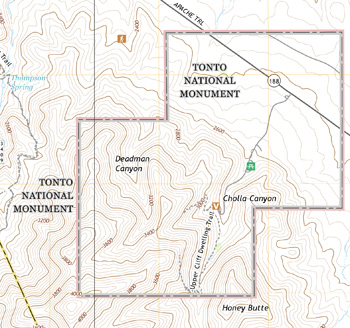

(click for larger maps) |

Your Visit to Tonto National Monument

Things To Do The park is open daily except December 25 from 8 am to 5 pm. The visitor center offers information, exhibits, a video, and bookstore. The steep but paved one-mile round-trip trail ascends 350 feet to the Lower Cliff Dwelling; it is open daily. This trail closes to uphill travel at 4 pm. Guided tours to the Upper Cliff Dwelling are November through April; reservations required. Contact the park.

Facilities A picnic area is near the visitor center. Camping is not permitted in the park; camping is available at Theodore Roosevelt Lake. Find services in Roosevelt, Globe, and Payson.

Accessibility The visitor center's first floor, museum exhibits, restrooms, and picnic area are accessible to visitors in wheelchairs. Service animals are welcome.

Climate Summers are hot (100°F or higher); winters are generally mild. Rainy seasons occur in the winter months and summer monsoons. Wildflowers bloom in late winter or early spring.

For Your Safety and the Park's Protection

• Do not climb or lean on walls. • Pets, leashed and under control,

are allowed only on Lower Cliff Dwelling trail; pets are prohibited in the cliff

dwelling. • Stay on established trails. Steep grades and uneven surfaces

can create hazards. Visitors with heart or respiratory conditions should use

caution, especially in hot weather. • If you see a rattlesnake, retreat

slowly and report the sighting to a ranger. • Do not collect or disturb any

plants, animals, or archeological objects; all are protected by federal law.

Emergencies: call 911.

Location Tonto National Monument is 110 miles east of Phoenix, Ariz. Possible routes: Ariz. 188 west from Globe; 188 east from Ariz. 87 (Beeline Highway); or Ariz. 88 (Apache Trail) beginning at Apache Junction (the easternmost 22 miles of this road are unpaved and mountainous).

Source: NPS Brochure (2010)

|

Establishment

Tonto National Monument — January 18, 1934 (NPS) |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Biological Inventory and Hydrological Assessment of the Cave Springs Riparian Area, Tonto National Monument, Arizona (Eric W. Albrecht, William L. Halvorson, Phillip P. Guertin, Brian F. Powell and Cecilia A. Schmidt, January 28, 2005)

Archeological Investigation of Rooms 15 and 16 at the Upper Cliff Dwelling (AZ U:8:48 [ASM]), Tonto National Monument Western Archeological and Conservation Center Publications in Anthropology No. 73 (Gregory L. Fox, et al., 2000)

Archeological Studies at Tonto National Monument, Arizona Southwestern Monuments Association Technical Series No. 2 (Charlie R. Steen, Lloyd M. Pierson, Vorsila L. Bohrer and Kate Peck Kent, 1962)

Arizona Explorer Junior Ranger (Date Unknown)

At the Confluence of Change: A History of Tonto National Monument (©Nancy L. Dallett, 2008)

Environmental Impact Statement, General Management Plan: Tonto National Monument, Arizona Draft (January 2002)

Foundation Document, Tonto National Monument, Arizona (October 2017)

Foundation Document Overview, Tonto National Monument, Arizona (January 2017)

General Management Plan/Final Environmental Impact Statement, Tonto National Monument, Arizona (2003)

Geologic Map, Tonto National Monument (September 2020)

Geologic Resources Inventory, Tonto National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR-2020/2212 (Katie KellerLynn, December 2020)

History of Fire and Fire Impacts at Tonto National Monument, Arizona Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 59 (Barbara G. Phillips, May 1997)

Inventory of Assessment of Avifauna and an Monitoring Protocol Proposal for Tonto National Monument, Arizona CNPRSU Technical Report No. 62 (Katherine L. Hiett and William L. Halvorson, February 1999)

Junior Arizona Archeologist (2016)

Lower Cliff Dwelling Construction Sequence: Overview (Meghann M. Vance, October 8, 2013)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Lower Ruin (Linda B. Kelley, May 12, 1988)

Tonto National Monument Archeological District (Susan J. Wells, August 22, 1987)

Upper Ruin (Linda B. Kelley, May 12, 1988)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Tonto National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR-2019/2012 (Lisa Baril, Kimberly Struthers and Mark Brunson, September 2019)

Park Newspaper (Cliff Notes): Fall 2005 • Spring 2006 • Fall 2006 • Spring 2007 • 2007-2008 • 2008-2009 • Fall 2009 • Fall 2010 • 2011-2012 • 2012-2013

Prehistoric Ruins of the Gila Valley (J. Walter Fewkes, extract from Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, Vol. 52 Part 4 No. 1873, August 4, 1909)

Reducing Rattlesnake-Human Conflicts U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 2006-3062 (April 2006)

Report on Sullys Hill Park, Casa Grande Ruin; the Muir Woods, Petrified Forest, and Other National Monuments, Including List of Bird Reserves: 1915 (HTML edition) (Secretary of the Interior, 1914)

Report on Wind Cave National Park, Sullys Hill Park, Casa Grande Ruin, Muir Woods, Petrified Forest, and Other National Monuments, Including List of Bird Reserves: 1913 (HTML edition) (Secretary of the Interior, 1914)

Resurvey of 1961 Line Intercept Transects at Tonto National Monument CNPRSU Technical Report No. 38 (Nancy J. Brian, July 1991)

Roosevelt Red Wares and Salado Polychrome: Fact Sheet (Catherine Daquila and Duane Hubbard, June 19, 2008)

Springs, Seeps and Tinajas Monitoring Protocol: Chihuahuan and Sonoran Desert Networks NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR-2018/1796 (Cheryl McIntyre, Kirsten Gallo, Evan Gwilliam, J. Andrew Hubbard, Julie Christian, Kristen Bonebrake, Greg Goodrum, Megan Podolinsky, Laura Palacios, Benjamin Cooper and Mark Isley, November 2018)

Status of Non-native Plant Species, Tonto National Monument, Arizona NPS Technical Report NPS/WRAU/NRTR-92/46 (Barbara G. Phillips, August 1992)

Status of Terrestrial Vegetation and Soils at Tonto National Monument, 2009–2010 NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SODN/NRTR—2013/833 (J. Andrew Hubbard, Sarah E. Studd and Cheryl L. McIntyre, December 2013)

Surficial Geologic Map of Tonto National Monument, Arizona (September 2020)

Tonto National Monument: An Archeological Survey Western Archeological and Conservation Center Publications in Anthropology No. 31 (Martyn D. Tagg, 1985)

Tonto Ruins Stabilization, May 27 to June 30, 1937 Southwestern Monuments Special Report No. 19 (William A. Duffen, July 1937)

Tonto Trail to the Cliffdwellings: Tonto National Monument, Arizona 10th Edition (1971)

Upper Cliff Dwelling Construction Sequence: Overview (Meghann M. Vance, October 8, 2013)

tont/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025