|

Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site Alabama |

|

NPS photo | |

Not how much, but how well...

—Booker T. Washington

The Tuskegee name is an icon in African American history. It is synonymous with the tireless striving of a disenfranchised people to find a place for themselves in a society that was, at best, slow to make room. The school was the brainchild of former slave Lewis Adams. Adams organized African American support for a white politician, who then pushed through legislation in 1881 establishing a "Normal School for Colored Teachers at Tuskegee." From this seed, planted in repressive post-Reconstruction Alabama, the school flowered into a celebrated university and a symbol of African American achievement.

Aided by former slave owner George Campbell, Adams found an ambitious young teacher at Virginia's Hampton Institute to make his dream a reality. Booker T. Washington met with his first class of 30 male and female students in a shanty on the grounds of a church, but soon obtained 100 acres of farmland that became the nucleus of Tuskegee Institute. Drawing on the Hampton model and his own rise through hard work and self-discipline, Washington believed he could best improve the conditions of African Americans by teaching them practical job skills or helping those who were farmers become more efficient and productive. He combined the school's original mandate to train teachers with his own beliefs, recruiting academics like George Washington Carver and instructors who could teach carpentry, bricklaying, printing, and many other trades. He charged teachers to "return to the plantation districts and show the people there how to put new energy and new ideas into farming as well as into the intellectual and moral and religious life of the people."

Washington strove to make Tuskegee as self-sufficient as possible, in the process instilling resourcefulness and independence in his students. In the early years they raised their own food and, with bricks they made themselves, raised buildings designed by faculty architects. From the beginning the school was in the public eye, a showcase for the talents and character of the students. They wore uniforms, attended church daily, and were instructed in hygiene and the social graces. As word of Tuskegee spread, benefactors like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller helped the school grow. Over the next century it evolved into a university with strengths in aerospace engineering, veterinary science, and bioethics. Throughout Tuskegee's growth it has always been steered by Washington's vision of improving the lot of African Americans and, by achieving that goal, elevating all of American society.

The Oaks: Showcase of Progress

The house that Booker T. Washington built in 1899 gave concrete expression to the principles of the school—especially to the ideals of self-sufficiency and progress. The state-of-the-art steam heating, plumbing, and electricity, unique in the area, were intended to prove to the world what could be accomplished by African Americans.

Here students applied their skills to one of the most visible structures at Tuskegee. From designing the house to making the bricks to crafting the furniture, students and faculty helped build The Oaks. Students trained and earned money by cleaning and maintaining the house. The Oaks also embodied the personality of Washington, his Victorian tastes, and his aspirations to middle-class culture. This was where he found "the most solid rest and recreation," where, in the parlor, the family played games and listened to his daughter Portia play the piano.

The study was his sanctuary, where he could work on his articles and speeches and attend to the endless tasks involved in running Tuskegee. His words about his garden reveal much about the man: "I like, as often as possible, to touch nature, not something that is artificial or an imitation . . . . I feel that I am coming into contact with something that is giving me strength . . ."

"Do common things uncommonly well..."

Milbank Agricultural Building

At Tuskegee's founding most African Americans in the South were former enslaved workers who knew only farming. Many of them, debt-ridden and close to destitution, were barely scratching a living from exhausted soil. For Booker T. Washington, a basic mission of Tuskegee was to help these people. In 1892 he hosted the first Tuskegee Negro Conference to teach progressive agricultural methods.

When Washington established the agriculture department in 1896, he recruited George Washington Carver, a botanist and professor of agriculture at Iowa State College, to head it. Carver also took over the annual conference, now renamed the Tuskegee Farmers Conference. He broadened its scope, schooling farmers and their wives in nutrition, home construction, food preservation, and hygiene.

Carver also headed the school's Agricultural Experiment Station, whose mission included educating farmers who could not come to Tuskegee. In 1906 Washington and Carver initiated the Movable School. Carver designed the Jesup Wagon, equipped with machinery and supplies for conducting training at the farmer's doorstep. Carver's dozens of agricultural bulletins, on subjects ranging from soil science to cooking cow peas, were yet another way that Tuskegee reached out to those most in need.

Crimson and Gold Timeline

1881 Tuskegee Normal School for Colored Teachers is established by the Alabama State Legislature.

1884 Students build Alabama Hall, a dormitory and dining hall for women. It is the school's first building made of brick.

1891 Tuskegee becomes an independent school; its name is changed to Tuskegee Normal and Industrial School.

1901 Carnegie Library is dedicated. Publication of Washington's Up From Slavery gains Tuskegee broader public notice.

1906 Jesup Wagon program is initiated. For the school's 25th anniversary poet Paul Laurence Dunbar writes "The Tuskegee Song," beginning "Tuskegee, thou pride of the swift growing South." By this time there are 1,600 students and 83 buildings on 2,300 acres.

1910 Former President Theodore Roosevelt becomes a member of Tuskegee's Board of Trustees.

1915 Booker T. Washington dies. In 1916 Dr. Robert R. Moton becomes second president of Tuskegee.

1922 Monument to Washington is dedicated, with the inscription "He lifted the veil of ignorance from his people and pointed the way to progress through education and industry."

1923 The first Veterans Administration hospital staffed by and caring for African Americans opens at Tuskegee.

1927 Dr. Moton oversees the creation of the College Department; Tuskegee begins granting college degrees.

1932 The Tuskegee Choir sings at the opening of Radio City Music Hall.

1935 Dr. Frederick D. Patterson is named third president of Tuskegee.

1937 First 7-day course held as part of annual Farmer's Conference. The school is renamed Tuskegee Institute.

1939 President Franklin Roosevelt visits Tuskegee. Because of Tuskegee's strength in aeronautics, the Civilian Pilot Training Program locates a facility here—the first opportunity for African Americans to receive flight training from the government.

1941 Tuskegee becomes the training base for the all African American 99th Pursuit Squadron. Pre-flight training begins at the Institute, with primary flight training at the nearby Tuskegee Army Air Field until Moton Field, on Tuskegee Institute land, is completed later that year. It is the only military primary flight training facility for African Americans throughout World War II.

1942 First class of African American pilots graduate from Tuskegee Army Air Field and are commissioned 2nd Lieutenants in the Army Air Corps. Actor and singer Paul Robeson visits the Institute, his first trip to the deep South.

1947 Students and administration vote to establish fraternities and sororities at Tuskegee.

1948 Blue uniforms for men are discontinued. Compulsory chapel attendance continues: twice on Sunday and on Wednesday evening.

1953 Dr. Luther H. Foster, Jr. is named fourth president of Tuskegee.

1964 Tuskegee students form the Tuskegee Institute Advancement League (TIAL), which works closely with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to register voters.

1965 Group of Tuskegee students travels to Selma to take part in the Voting Rights March to Montgomery.

1966 Tuskegee student Sammy Younge, TIAL/SNCC voting rights organizer, is shot and killed when he attempts to use a white restroom. He is the first African American college student killed in the civil rights movement.

1972 Robert Dietrick, of the School of Engineering, is awarded a patent for an artificial eye lens for cataracts.

1974 Congress authorizes Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site as a unit of the National Park System.

1981 Dr. Benjamin F. Payton is named fifth president of Tuskegee.

1985 After reorganization of programs school becomes Tuskegee University.

Touring Historic Tuskegee Institute

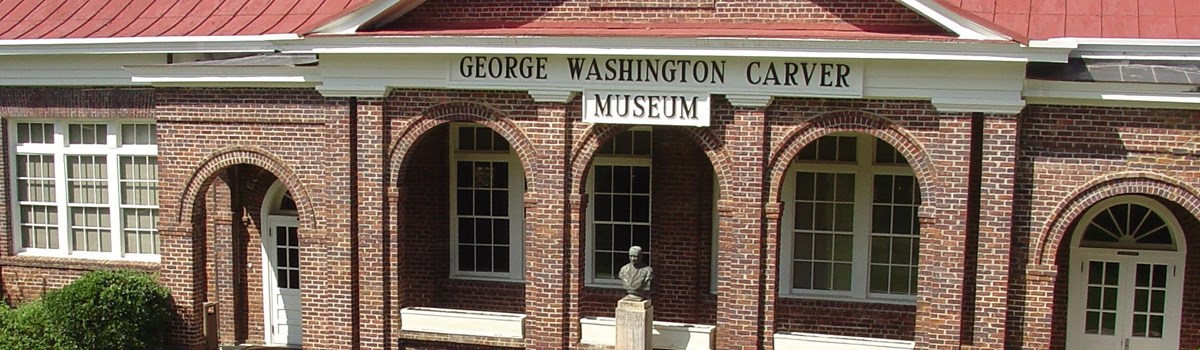

We suggest you begin your tour at the visitor orientation center in the George Washington Carver Museum. Exhibits and audiovisual programs provide a broad overview of George Washington Carver, Booker T. Washington, and the historic school. This and many other buildings in the Historic Campus District were designed by Tuskegee architect Robert R. Taylor and erected by students using bricks they made at Tuskegee.

The Historic Campus

Many buildings constructed while Booker T. Washington was president (1881-1915) still stand. Their historical names follow their present names.

George Washington Carver Museum (Laundry) 1915 Built as a laundry, in 1938 this building became a museum devoted to Carver's work. Since 1976 the museum has also housed Tuskegee's cultural artifacts.

The Oaks 1899 Faculty and students designed and constructed this brick Queen Anne style house as a private residence for Booker T. Washington.

Booker T. Washington Monument 1922 Contributions from African Americans around the nation funded this monument designed by Charles Keck.

Chapel Site 1898 and Tuskegee Cemetery Tuskegee's interdenominational chapel, destroyed by fire in 1957, was near the present chapel and the graves of Booker and Margaret Washington and George Washington Carver.

Tantum Hall 1907 This women's dormitory was endowed by Margaret W Tantum in the name of her father, Dr. James D. Tantum.

Dorothy Hall/Kellogg Conference Center (Girls' Industrial Building) 1901 Upholstery, dressmaking, and other trades for women were taught here. It was also George Washington Carver's residence from 1938 to 1943.

White Hall 1910 The prominent clock tower and massive brick columns on the main women's dormitory make it a campus landmark.

Douglass Hall 1904 Named after Frederick Douglass, this women's dormitory was rebuilt after a 1934 fire.

Huntington Hall 1899 Mrs. Collis P. Huntington, wife of the railroad builder, endowed this women's dormitory.

Tompkins Hall 1910 The central dining hall and the assembly hall, later converted to the student union, made this building the focal point of student life.

Collis P. Huntington Memorial Building Site (Academic Building) 1905 This was the main College of Arts and Sciences building. Destroyed by fire in 1991.

Rockefeller Hall 1903 John D. Rockefeller endowed this men's dormitory, which also housed a library and museum.

Phelps Hall Site (Bible Training School) 1892 This was also used as a dormitory. It was moved to this site in 1933. Demolished in 1993.

R.O.T.C. Armory Site (Boys' Bath House) 1904 This building, which once contained a swimming pool, later housed Army Air Corps cadets during World War II and an arms supply room. Demolished in 1993.

Thrasher Hall (Science Hall) 1893 This structure housed the school's first science classes and laboratories.

Band Cottage (Foundry and Blacksmith Shop) 1889 The oldest standing building on campus, it is now used for band music lessons and practice.

Old Administration Building (Office Building) 1902 For almost 75 years Tuskegee's administrative work was carried out here. It also housed the school's first post office and bank.

Carnegie Hall (Carnegie Library) 1901 Carnegie Library was one of the many libraries funded by philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. In 1931 the music department moved here and it became Carnegie Music Hall.

Margaret Murray Washington Hall (Armstrong-Slater Memorial Agricultural Building) 1897 This early center for agricultural teaching also hosted home economics classes and the Agricultural Experiment Station.

Emery Halls (Emery Dormitories) 1903-1909 These men's dormitories were funded by Elizabeth Julia Emery of England.

Milbank Hall (Milbank Agricultural Building) 1909 This building housed the Agriculture Department's classrooms and laboratories and George Washington Carver's personal laboratory.

Dairy Barn Site 1918 This two-silo brick dairy barn was part of the agricultural program. Destroyed by fire in 2004.

Food Science Building (Veterinary Hospital) 1915 Tuskegee's hospital for treating farm animals later housed the Food Science Division laboratories.

Power Plant 1915 Steam-driven generators produced electricity in the early years.

Carver Research Foundation 1940 George Washington Carver donated a large part of his life savings to establish a center for continuing his agricultural research.

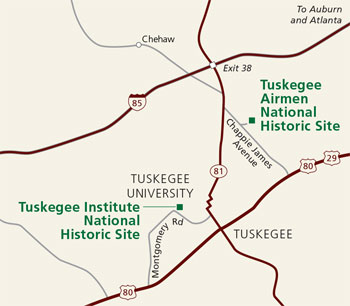

(click for larger map) |

Planning Your Visit

Directions From I-85 take exit 38 (Tuskegee-Notasulga exit); turn onto Alabama Hwy. 81 and drive three miles into the City of Tuskegee. Turn right at first traffic light onto West Montgomery Road. Drive one mile; at second traffic light turn right through the Lincoln Gates into the Tuskegee campus. The Kellogg Center will be on your right. The George Washington Carver Museum is behind the Kellogg Center. Parking is available behind the Kellogg Center and near The Oaks.

Hours The park is open 9:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. daily except Thanksgiving, December 25, and January 1.

Safety While walking be careful of traffic. Summers are hot and humid, with temperatures ranging from high 80s°F to high 90s. We recommend light clothing and good walking shoes.

Accessibility All exhibits and the George Washington Carver Museum are fully accessible. Wheelchairs are available at the George Washington Carver Museum. The Oaks is accessible only on the first floor. Accessible parking is available at both sites.

Source: NPS Brochure (2009)

|

Establishment Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site — October 26, 1974 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Condition Assessment Report: The Oaks, Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site, Alabama (Panamerican Consultants, Inc., Wiss, Janey, Elstner Associates, Inc. and WFT Architects, December 2016)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: The Oaks, Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site (2022)

Cultural Landscape Report: The Oaks, Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site (WLA Studio, March 2018)

Foundation Document, Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site, Alabama (April 2017)

Foundation Document Overview, Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site, Alabama (January 2017)

Furnishing Plan: The Oaks (Kathleen McLeister, 1980)

General Management Plan: Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site, Alabama (1978)

Historic Picture of Tuskegee, Alabama (undated)

Historic Resource Study: Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site, Tuskegee, Alabama Draft Report (John W. Jenkins, June 1977)

Historic Resource Study, Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site (Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc., June 2019)

Historic Structure Report: George Washington Carver Museum, Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site, Alabama (Panamerican Consultants, Inc., Wiss, Janey, Elstner Associates, Inc. and WFT Architects, December 2016)

Historic Structure Report: Grey Columns, Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site, Tuskegee, Alabama (June 1980)

Historic Structure Report: The Oaks, Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site, Tuskegee, Alabama (April 1980)

Historic Structure Report: The Oaks, Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site, Alabama (Panamerican Consultants, Inc., Wiss, Janey, Elstner Associates, Inc. and WFT Architects, December 2016)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site (2003)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Grey Columns (David Arbogast April 16, 1979)

Tuskegee Institute (Horace J. Shelly, Jr., March 1, 1965)

tuin/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025