|

TUMACACORI

Tumacacori's Yesterdays |

|

THE CLOSE OF THE JESUIT PERIOD

For many years missionary work in upper Pimeria Alta was at a standstill, and we learn almost nothing of the region during that time. In 1731 three new priests were assigned to the district, and after a training period south of the present border, went to their stations. A year later we find Father Grashofer assigned to Guevavi, with four visitas, including Tumacacori, under his charge. Father Segesser went to San Xavier, and Father Keller to Suamca, with the whole San Pedro Valley as his charge. Before the close of 1732 these three missionaries had baptized more than 800 people, validated some marriages, and done a lot of other work.

But the continuity was soon interrupted, this time by the death of Father Grashofer, and by 1736 Father Keller alone remained in upper Pimeria Alta, responsible not only for the San Pedro Valley, but for the missions of San Xavier and Guevavi and the other Indian villages of the Santa Cruz. It was impossible for one man to handle such an enormous territory adequately, with the result that progress generally began to die again.

Into the picture at this time came Father Jacobo Sedelmayr, a Bavarian Jesuit, to take charge of all missions in Pimeria Alta. Sincere, enterprising, and ambitious, he might have established, if properly aided and encouraged, strong mission outposts clear to the Gila and Colorado Rivers. As it was, his energies were limited mostly to restoring several of the missions to their former strength. While we learn little of Tumacacori during his time, he was destined to see Pimeria through one of its most critical periods.

By 1741 Tumacacori was again receiving attentions from a missionary. On May 23 of that year Father Joseph de Torres Perea, stationed at Guevavi, joined in marriage the governor of Tumacacori, Joseph Tutubusa, to a San Xavier girl named Martha Tupquice. One can guess that this must have been quite a social and diplomatic event, and was probably preceded by three or four days of "fiesta."

Ten years later, in 1751, Tumacacori remained without a resident priest, but was still a visita of Guevavi, under charge of the latter's priest, Jose Garrucho. Despite setbacks here and there, conditions in Pimeria Alta looked better than they had for a long time. Father Sedelmayr was still in the region, there were eight missions which actually had resident priests, and mission affairs were thriving in most spots.

The year opened well, but was destined for a bloody ending. In the Altar Valley to the south and west, a Pima Indian named Luis Oacpicagua (I can't pronounce it, either) , became ambitious because he had been appointed a captain of his people as a reward for aiding the Spanish against the Seris, and decided to organize the Pimas and Papagos to drive the Spanish out of the country. He thought he would like to rule the province himself. Luis had been distinctly impressed by failure of the Spanish attempt at missionary work among the Seris, who were often regarded as the Apaches of western Sonora.

On the night of November 20 Luis figured the time was ripe, and succeeded in igniting the historic Pima rebellion. Father Sedelmayr, at Tubutama, was warned only a few hours in advance that the uprising was to occur. A faithful mission Indian, Ignacio Matovit, was responsible for this. Sedelmayr immediately notified several neighborhood Spaniards of the danger, and they joined him in taking refuge in the mission buildings: He sent word to Father Juan Nentwig, at the visita of Saric, urging him to come at once. Nentwig received the message and fled, on horseback, spared of martyrdom by only a matter of hours.

The revolt started with destruction of the church at Saric, and the murder of Nentwig's servants and the wife and children of the mayordomo of the town. Luis' men quickly pushed on to the mission at Tubutama. Here, after a two- day siege, Father Sedelmayr's fine new church and new house were destroyed, and the padre barely escaped with his life. He, Nentwig, and several other Spaniards fled under cover of darkness, and finally reached Santa Ana nearly two days later.

The isolated missions of Caborca and Sonoyta (on the west) received the main fury of the uprising, with great destruction ensuing, and the murders of Fathers Tomas Tello, of Caborca, and Enrique Rhuen, of Sonoyta. Within a week's time the insurgents had laid waste the larger settlements in western Pimeria Alta, and more than 100 persons had died the hands of the rebels.

Not a great deal is known of the effects of the revolt in the northern part. At Arivaca, across the mountains about miles west of Tumacacori, the Pimas attacked and killed several families. At San Xavier, Father Francisco Pauer decided a few days later that revolt was brewing, and fled Guevavi. Here he joined the resident priest, Father Garrucho. In company with a number of other people from the district, they retreated to the south. Apparently all except Garrucho, who for some unknown reason turned back, succeeded in joining Father Keller at Suamca, which was not attacked.

After considerable difficulty, Governor Parrilla of Sonora finally put down the revolt. He then engaged in a bitter quarrel with the Jesuits, claiming their cruel treatment of the natives had caused the uprising, while the Jesuits countered with the charge that Parrilla was responsible, for having given Luis his honors, and that military blunders had been made in suppressing the uprising. Another item of fuel for the dissension had been Luis' earlier attempts to discredit Sedelmayr with the civil authorities, since the latter's extensive travels in Pimeria Alta had been a threat to his growing plan of revolt.

|

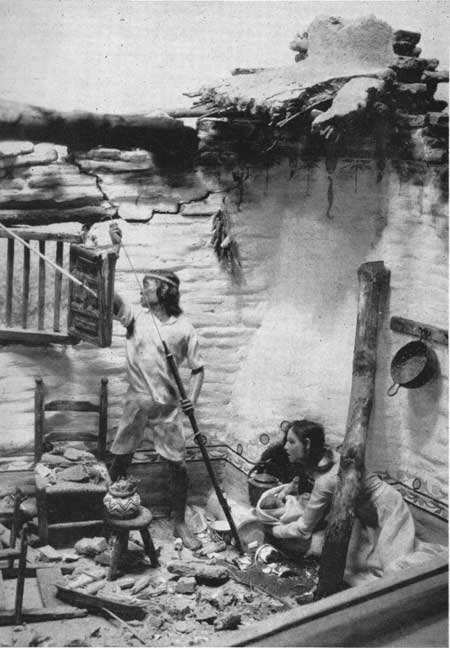

| Portion of the diorama in the museum showing the defense of Tubutama mission, Sonora, in the Pima Rebellion of 1751. |

Eventually the Jesuits were exonerated of the charges placed against them, but their influence in Pimeria Alta had been irreparably damaged, and the later phase of their activity in the region, while busy, did not indicate expansion. For several years however, despite lack of support from the civil government, they continued to operate the missions of San Xavier, Guevavi, Suamca, Saric, Tubutama, Caborca, and San Ignacio.

A direct result of the rebellion was the establishment, in 1752, of the presidio of Tubac, three miles north of Tumacacori. Here a garrison of 50 soldiers was made responsible for protecting Tumacacori, Guevavi, the rancheria of Arivaca, and points as remote as San Xavier! This action was a little like trying to make a waterproof coat out of mosquito netting, but it did keep the Spanish flag flying in this frontier, and enabled the two missions of Guevavi and San Xavier, with their visitas, to exist. However, the going must have been tough, for the priest at Guevavi reported that it had been three years after the rebellion before the Indians returned to the Guevavi pueblo. At the same time, San Xavier became a visita of Guevavi, which was something of a come-down for a large town. This condition was to exist for several years.

There is good evidence to indicate the first Jesuit church Tumacacori, (as distinguished from the adobe chapel of Kino's time) was built by 1757. Through all the early years of the Guevavi church register there is no mention of a church building at this visita, although there were entries of burials in the Tumacacori cemetery, and others to indicate the people of the town were being married in Guevavi. Then, on July 7, 1757, comes an entry in Guevavi's burial register, that Lorenzo, the alcalde of Tumacacori, was buried in that church. [Probably Tumacacori.]

A distinctly confusing reference comes in the Rudo Ensayo, an anonymous but apparently authoritative document of the period, (believed by some to have been written by Father Juan Nentwig) which indicates that in 1761 or 1762 the presidio of Tubac "was a visita of Guevavi, whose people now inhabit Tumacacori, but because they do not have there as good land for irrigation as at Tubaca, their residence there depends upon the season for the crops." It would be interesting to learn why people who could have lived within the protective shadow of the Tubac presidio went to live with the villagers of Tumacacori, three miles away, when their very important farming activities here were hampered by irrigation difficulties.

From several references it appears there was considerable shifting into and out of the community, although there probably was always a stable element of the older families which consistently stayed on. One source states that in 1763 the Guevavi visitas of Tumacacori and Calabasas (Calabasas was between Guevavi and Tumacacori) were composed of Pima and Papago neophytes, but "the latter had run away in this year." Yet, the population of Tumacacori in 1765 was 199 persons, representing 87 families. This is the largest count we know of for the town.

|

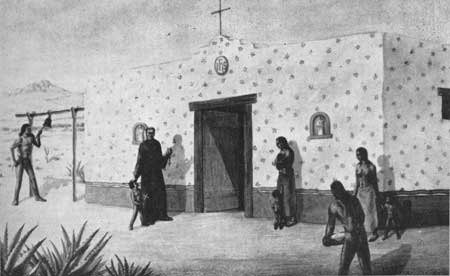

| The chapel of Jesuit times as envisioned by the artist in a museum illustration. |

Nicolas de La Fora, out on a map-making expedition in December, 1766, came through the San Pedro and Santa Cruz River Valleys. Entering the Santa Cruz near the abandoned ranches of Santa Barbara, San Francisco, and San Luis y Buenavista "abandoned through the hostilities of the Apaches," La Fora's party went downstream to the mission of Guevavi, populated by 50 Pimas. Onward they went to little town of Calabasas, "which was of upper Pimas, those who all perished in a bad epidemic, and repopulated Papagos; five leagues farther on we found that of Tumacori [evidently Tumacacori] of the same nation, and both dependent on the mission of Guebabi, this being one league the presidio of San Ignacio of Tubac . . ."

If the Papagos had run away in 1763, they didn't stay away very long! The very high population of 199 persons in 1765 almost certainly included some Papagos, and there is mistaking the meaning of La Fora's comments a year later.

The epidemic to which he referred probably was typical of colonial America, in that it likely was a disease introduced by Europeans, to which natives had developed little resistance. It may have been smallpox, which so often marked the New World trails of the white man with sanguine reminders.

Abruptly, this frontier reached another historic milestone in 1767 when, by royal decree, the Jesuits were ordered expelled from all of New Spain. We have seen that there was some dissension between Jesuit missionaries and the military. The Jesuit order included many of the most brilliant men of the time, who occupied particularly influential positions as teachers and missionaries, and were not famed for reticence, but rather were forward, in speaking their minds. Their almost militant defense of mission Indians against exploitation as virtual slave labor in mines and on great ranches made them unpopular. Some persons thought the Jesuits were too ambitious, and gaining an undue amount of influence. The entire and somewhat confusing story of why Jesuits were expelled from New World Spanish dominions is too detailed for inclusion here. At any rate, King Carlos III of Spain expressed himself to the effect that continued activity of the Jesuit missionaries was not in the best interests of Spain, and they were ordered out.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

jackson/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 10-Apr-2007