|

TUMACACORI

Tumacacori's Yesterdays |

|

TUMACACORI GAINS IMPORTANCE UNDER FRANCISCANS

A year later, in 1768, Franciscan missionaries of the College of Queretaro were placed in charge of the Pimeria Alta missions. Guevavi in this year received a resident Franciscan priest, Father Juan Crisostomo Gil de Bernave, with the three visitas of San Jose de Tumacacori, San Cayetano de Calabasas, and San Ignacio de Sonoitac. We note that San Cayetano, who in Jesuit times was the patron saint of Tumacacori, was succeeded in Franciscan times here by San Jose.

At this time Tumacacori had adobe houses for the Indians to live in, and some walls for defense purposes, and there is a reference that the church and priest's house were bare of furniture and ornaments. One could infer from this statement that there had been a resident priest at Tumacacori, but we do not believe that such could have been the case. We think the priest's house was simply the house in which the visiting priest stayed on the occasion of his visits to the town.

|

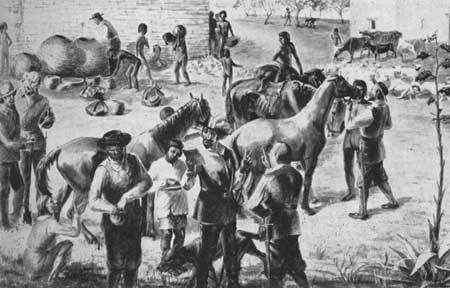

| In 1767 the King's commissioners held a sale of the property, mostly stock, of the expelled Jesuit Order. |

If the church and priest's house were bare in 1768, they were in even poorer state the next year, for we read of an Apache attack which left Tumacacori almost in ruins [4]. Presumably this attack caused some of the native population to flee, for in 1772 we find two census figures which show a decided drop below the 199 figure given a little earlier. Unfortunately, statistics have a habit of being frequently confusing, and such is the case here. One count for this year gives only 39 inhabitants for the town, the other gives 93 persons. Of course, both figures could be right, for different times of the year!

Tumacacori's future definitely brightened in 1773, for on this momentous date she took over Guevavi's role as head mission for the district [5]. At the same time we see the first mention in the church register of the new name, "este pueblo de Joseph de Tumacacori." Guevavi then dropped to the rank of a visita. Reasons for this change are not completely clear, but apparently shifts in intensity of attacks along the Apache frontier caused the authorities to regard Guevavi's higher status as untenable. This reasoning is well borne out in a statement of October 15, 1775, by Father Font, diarist of the famous De Anza expedition to California. In his account, he says he left the main group and went ahead with four soldiers to say Mass at the pueblo of Calabasas, "which is a visita of the mission of Tumacacori, and formerly was a sub-station of the mission of Huevavi, which was depopulated by Apaches." He then went on to Tumacacori, staying there for several days.

|

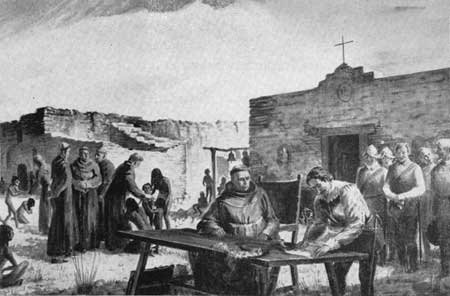

| After being placed in charge in 1768, the Franciscan Order took over the church's property from the King's commissioners. |

Captain Juan Bautista de Anza, commandante of the presidio of Tubac, had for long desired to prove that a feasible overland route could be laid out to California. Spain was particularly desirous that missions and presidios be established in that land, especially on the coastal region, to prevent Russian encroachment southward. Work of California missionaries, which started with establishment of a mission at San Diego in 1769, was being encouraged, but there was great expense, delay, and danger in having to send all supplies to he California outposts by a water route from Mexico's west coast around the peninsula of Baja California.

In 1774 De Anza made a preliminary trek to the southern part of California, and now, late in 1775, he had secured authorization to undertake a more extensive expedition, and take along colonists. The group started from Horcasitas, Sonora, went northward into the Santa Cruz Valley, via Tumacacori, Tubac, thence north and west down the Santa Cruz to the Gila, westward to the Colorado, across it northwestward through the California desert, and eventually to Monterey and San Francisco Bay, where a mission and presidio were established, and the great city of San Francisco had its origin.

Tumacacori contributed to the founding of San Francisco, by furnishing some of the beef cattle which were driven on foot with the expedition! But she suffered because of this trip, for while part of Tubac's garrison of soldiers was absent with De Anza, the Apaches raided. On May 24, 1776, Don Felipe Velderrain, alferez of Tubac, came to see Father Font at Caborca, and reported that "nothing now remained at the mission of Tumacacori, for the Apaches had carried off everything and caused much damage . . ."

More bad news for 1776 was the transfer of the Tubac garrison to Tucson, although later there were soldiers again at Tubac. However, the most confirmed optimist could never have considered its handful of soldiers as really adequate protection for the several pueblos, rancherias, and mission areas of what is now southern Arizona. Even at Tubac, while the soldiers were stationed there, the crafty Apaches succeeded, in the course of several raids, in stealing over 500 precious head of horses!

Nevertheless, the dauntless missionaries did not give up their work. Entries in the Tumacacori church register continued in 1777, to be followed by many entries in the follow ing year. The church was evidently repaired not too long after the raid of 1776, for we have a reference, commenting on the commonplace grim reality of the frontier, that the killing of Father Felipe Guillen in 1778 on the road between Atil and Santa Teresa (south and west of Tumacacori) did not deter the padres in their work "Other church buildings were repaired and roofed, as at Tumacacori, Cocospera, and Calabazas, or decorated . . ."

|

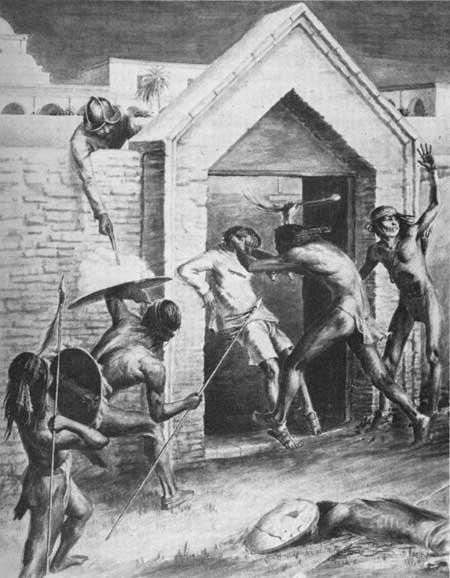

| A museum illustrator pictures how one of the Apache raids on Tumacacori could have appeared. Note use of lances, shield, and war club. |

Incidentally, Father Font drew a map in 1777 which showed Tumacacori's mission church on the east bank of the Santa Cruz. There is a bit of confusion, however, as to which side of the river the church was on. La Fora prepared a map as result of his 1766 trip, which showed the mission on the west side. But a map made "por los jesuitas en 1757" indicated the church on the east bank. There are inaccuracies in all these maps which leave them open to question. It is the belief of this writer that the church was on the west bank of the river, as will be explained later in this paper.

In a list of churches repaired and decorated in the period 1768 through October 23, 1783, we find our pueblo was given added protection by construction of a wall around it, made of "adobe material of clay." Before 1791 there was not only a new roof over the church, but the protective wall around the pueblo contained adobe houses inside it to serve as homes for the neophytes.

It is doubtful if defensive walls built around several of the frontier pueblos during this period would have been of very great value, in themselves. But a radical policy change, introduced by New Spain's Viceroy Galvez in 1786, was to have far reaching effects in Apache management for many years. Since the military, with its scattered forces, had been singularly unsuccessful in subjugating or decimating this most hostile and resourceful enemy, Galvez decided a bad peace was better than a good war. At the expense of the government, old wants and weaknesses of the Apaches were to be increased. Trinkets for personal adornment were to be given out. Whiskey, and inferior quality fire-arms and powder, were to be given them, and different tribes of hostiles were to be incited in every way to warfare between themselves. Extermination alone was the policy to be favored. He felt that after a long time God might miraculously show the hostiles the way to conversion and civilization, but that at present it was folly to think of such things.

The new policy was soon put into effect, and during the next 30 years, at great expense to the Spanish government, the Apaches enjoyed its fruits to such an extent that frontier warfare reached its lowest point up to that time. The comparative peace that existed from about 1790 to 1820 saw the work of the missionary priests attain a high point, and during these years came Tumacacori's heyday.

But it seemed that nothing should ever come easily for our town. Reports for 1790 and 1793 indicate that the missions, as a group, were prospering, with Tumacacori an exception. It is possible the reporter may have been more impressed with the physical evidence of handsome church buildings at other places than with the spiritual life of the natives alone. Certainly, the mission church of that time at Tumacacori was anything but an imposing structure. A description of 1795 says, "The church was a very cramped and flimsy little chapel, which has been made over piecemeal; and today it is big enough to hold the people of the Pueblo; it is made of earth and is in bad shape . . ."

It was in this year also that Father Balthazar Carrillo, who had been missionary at Tumacacori since 1780, died. He was buried by Father Narciso Gutierrez, who had come to work with him in 1794, and who was to labor here until his own death in December of 1820. Each of these men, much longer in service at Tumacacori than any others during the Franciscan period, was, during the greater part of the time, alone. Only during the last year of his life did Father Carrillo have a brother missionary to share his work.

A most interesting census of Tumacacori was made in 1796 [6] by Father Mariano Bordoy, who worked with Father Gutierrz during the period 1796-9. He counted 103 people for the pueblo, a population which was essentially Papago and Pima, with 48 of the former and 36 of the latter. There were also 12 Yaquis, 4 Spanish, 1 Apache, 1 Yuma, and 1 Opata. The majority of the older people were Pima, which indicates the probability, despite numerical superiority of Papagos, that the older and more stable element of the community was dominantly Pima. Most of the Yaquis were listed as "vezindarios," or from "surrounding area," or "vicinity," which suggests they had not been a part of the community long enough to merge their civic identity with that of the townsfolk.

|

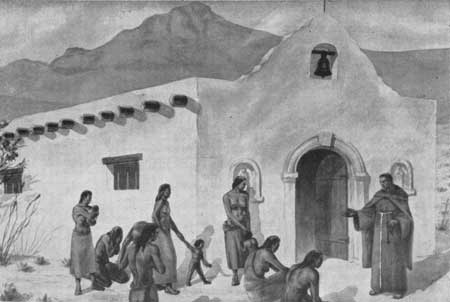

| The Franciscan chapel or church as it could have appeared about 1795. |

Father Bordoy's comments about the church at Tumacacori are quoted: "As to the church structure, I say: that it is now split open into two parts and that consequently there is some need that a new one be built. The resources which the mission at present has for that purpose are quite small. Since it scarcely has lands in which to sow, not because these are lacking, for there are lands, but because the water is lacking with which to irrigate them; so that this year of the four parts of wheat which I had sowed three were lost because of lack of water. Cattle are not worth much, since they have increased in these lands. And consequently, the resources which the Mission has for the building of a Church are small as has already been said."

Much can be read between the lines of Father Bordoy's comments. Although it was customary that most of the actual labor for construction of a mission church should be donated by the converts, there were certain costs that had to be met. The mostly highly skilled work probably had to be done by artisans, who frequently were not members of the native community. They had to be paid. Obviously, certain items used in church construction and furnishings had to be paid for in coin or negotiable goods. Royal treasury funds were either inadequate or lacking here at that time. A missionary would scarcely have planted four times as much wheat as he expected to be able to irrigate, so we can assume a drought. The low price of beef, and the shortage of wheat, either for food or trade, gave a rather somber economic outlook.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

jackson/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 10-Apr-2007